Supporting Home-Based Self-Regulated Learning for Secondary School Students: An Educational Design Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

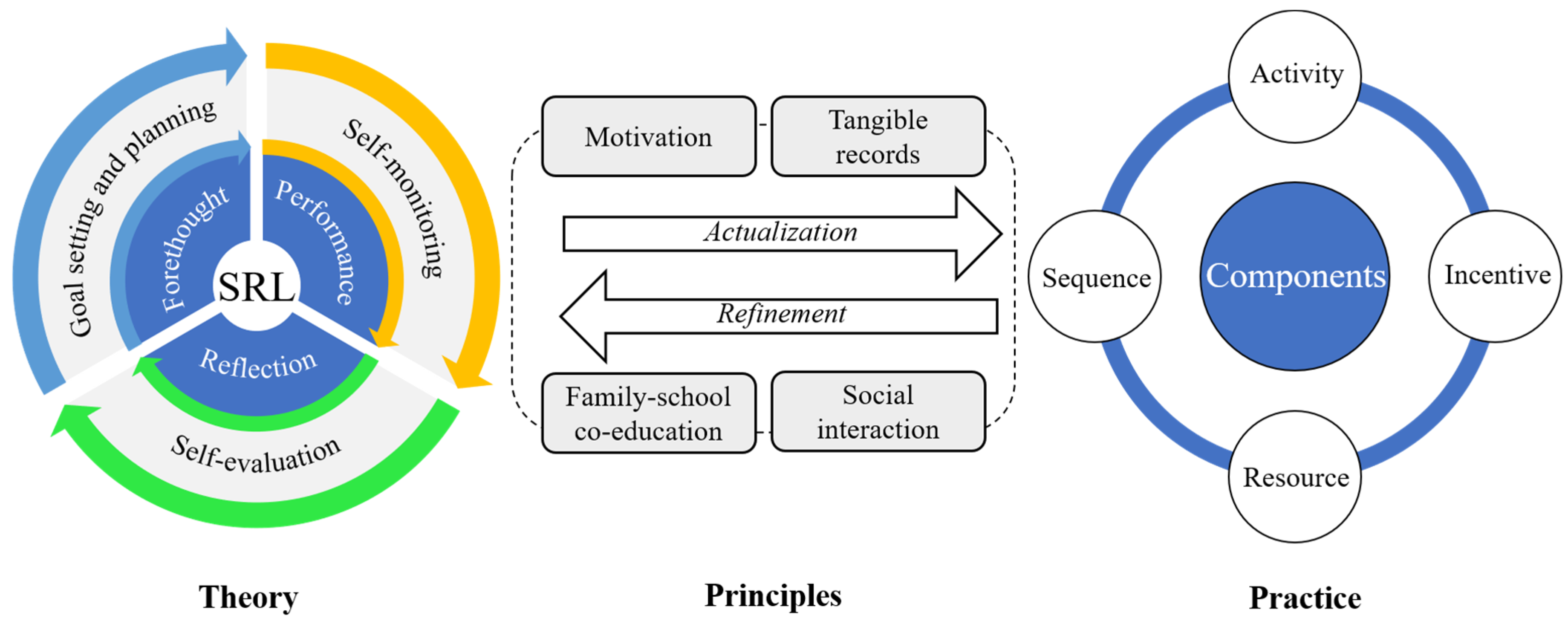

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Three-Cycle Phased Model of Self-Regulated Learning

2.2. Key Objectives of Self-Regulated Learning

2.2.1. Goal Setting and Planning

2.2.2. Self-Monitoring

2.2.3. Self-Evaluation

2.3. Initial Design Principles of Self-Regulated Learning Development

3. Methods Employed

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Context

3.2.1. The Research Site

3.2.2. The Education Problem

3.2.3. Participants

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Thematic Analysis

3.4.2. Document Analysis

3.4.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Initial Design of the Instructional Implementation Mechanism

5. Results

5.1. First Iteration

5.1.1. Implementation

5.1.2. Evaluation and Revision

5.2. Second Iteration

5.2.1. Changes in Design

5.2.2. Implementation

5.2.3. Evaluation and Revision

5.3. Third Iteration

5.3.1. Changes in Design

5.3.2. Implementation

5.3.3. Evaluation and Revision

6. Discussion

6.1. The Proposed Mechanism Worked Well in Home-Based Learning Environments and Could Be Applicable to Other Learning Contexts

6.2. Family–School Co-Education Plays a Significant Role in the Development of Self-Regulated Learning Skills in Secondary School Students

6.3. Social Interaction with Teachers and Peers Motivates Engagement in Self-Regulated Learning Activities

6.4. The Paper–Pencil Approach Is Preferable for Creating Tangible Records

7. Conclusions

- P1.

- Stimulate the intrinsic motivations (e.g., analyzing learning problems, giving the rationale behind strategies, and setting goals continuously) and external motivations (e.g., group competition) of students to engage in SRL activities.

- P2.

- Constantly implement individual tangible records as tools for the practice of students’ planning, monitoring, and evaluating skills, gradually giving them autonomy in the management their acquisition of SRL skills and adjusting the scaffolds according to dynamic changes in their technical level of self-regulation.

- P3.

- Organize regular peer-communication activities so they can share and obtain peers’ feedback on the SRL learning process.

- P4.

- Provide individualized feedback, social encouragement, and guidance on common issues through teachers to facilitate students’ work within the learning process.

- P5.

- Create opportunities for parents to participate in the SRL skill learning process and provide them with certain guidance and scaffolding.

- P6.

- Follow the general sequences of “learning problem analyzing–goal setting and planning–daily monitoring–evaluating” to develop SRL skills.

- P7.

- Be flexible about the four aspects of the mechanism and follow the principle of gradual progress, starting with less progress and gradually increasing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Appendix Tables

| Method | Definition | Operation | Example Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural coding | Conceptual phrases representing topics of inquiry to address specific research questions. | Structural codes consisted of a list of preconceived evaluation questions, such as those inquiring into the experience of using monitoring forms, and as to their perceived effects. | MONITORING FORM, LEARNING GROUP, TEACHER FEEDBACK, PARENT COMMENT |

| In vivo coding | Actual words or phrases used by participants, also known as “verbatim coding”. | In vivo codes used participants’ own words from the interviews to describe their learning experiences to ensure any interpretations and conclusions were grounded in data. | “SCATTERED”, “CIRCUMSCRIBED”, “MORE CLARITY”, “WEEKLY SUMMARY”, “SUPERVISE” |

| Magnitude coding | Alphanumeric or symbolic codes to indicate intensity, frequency, direction, presence, or evaluation. | Magnitude codes were combined with other codes to evaluate instructional design features: the frequency, intensity, and overall opinions. | POS = POSITIVE, NEG = NEGATIVE, NEU = NEUTRAL; EXTREMELY (E), DETERMINE (D), POSSIBLE (P) |

| Value coding | Codes reflecting participants’ values, attitudes, and beliefs, or representing their perspectives or worldviews. | Value codes directly address research questions regarding valued and not-valued design features. Some value codes were determined a priori, and some were constructed during data coding. | Values: HEALTH, HABIT, BE LIVELY Attitudes: USEFUL, HUMOROUS, PRETTY GOOD, NOT ALONE Beliefs: ENRICHED, COMPLETE AS SCHEDULED |

| Evaluation coding | Codes that assign judgments about merit or worth, or the significance of programs or policies. | Evaluation codes were extracted based on researcher judgments and participant comments and used with other coding methods to address evaluative inquiries regarding the instructional design features and effects. | IMPROVE EFFICIENCY, + “PRESIST EVERYDAY”, − OCCASIONALLY FORGET, REC (recommendation): WRITE A DAILY THOUGHT |

| Versus coding | Dichotomous or binary codes applied to a segment of data, in directions conflicting with each other. | Versus codes highlight participants’ different or contradicting views on their learning experiences; also indicate conflicting findings from pilot and field tests. | NOTEBOOK VS A FORM, ESTIMATED TIME VS ACTUAL TIME, PAST VS PRESENT, USEFUL VS GENERAL |

| Themes | Example Codes | Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulate motivation (2 themes, 54 codes) | Students | ||||

| Case | Code | ||||

| Motivated to engage in SRL activities by peers and teacher | Active group leader, like to add points, everyone is very positive, reminder from group leader not to deduct points, inspired by star review, etc. | 7 | 24 | ||

| Perceived usefulness and continuing to use | Monitoring journal is very useful, continue to use consistently, teacher feedback is very useful, group discussion helps me solve problems, etc. | 9 | 30 | ||

| Implement individual tangible records (6 themes, 84 codes) | Students | Parents | |||

| Case | Code | Case | Code | ||

| Stay organized and on top of daily homework with ease | Know daily homework, seeing whether completed all assignments, not easy to forget special homework, knowing what to do, more organized, etc. | 4 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| Enhance learning productivity and gain more free time with improved homework efficiency | Improve homework efficiency, a lot of extra time to do things you can’t do before, improve learning efficiency, etc. | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Facilitate the identification and addressing of learning issues through reflection | Helped me detect procrastination, discovering issues with insufficient time, find areas for adjustment and improvement, see if the goal has been achieved, reflect one’s progress and decline, etc. | 4 | 16 | 2 | 2 |

| Improve time management and achieve better study habits | Better evaluation of time, realizing that there is not enough time, plan and arrange, time management, help arrange study time reasonably, etc. | 3 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Promote self-discipline and achieve academic goals with monitoring | Monitoring role, supervise the completion of homework on time, enhancing self-discipline, supervise children to achieve goals, etc. | 1 | 1 | 11 | 16 |

| Experience the satisfaction of self-directed learning and personal growth | Seeing one’s own progress, daily learning becomes more fulfilling, it’s my own, more self-directed learning, independently complete on time, etc. | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Group discussion activity (5 themes, 38 codes) | Students | ||||

| Case | Code | ||||

| Increase accountability and engagement through mutual supervision and reminders | Remind to submit monitoring journal, supervise the submission of homework, remind to attend class seriously, etc. | 8 | 13 | ||

| Collaborate and make progress together by addressing challenging questions and solving problems. | Help to solve problems, discuss the question that cannot be done, make progress together, etc. | 5 | 13 | ||

| Learn from classmates’ designs to improve one’s own monitoring journal design | Knowing own shortcomings, drawing on the design of monitoring journal, etc. | 4 | 8 | ||

| Increase efficiency through synchronous task completion and adherence to agreements | Increase efficiency, do the agreed task synchronously, etc. | 1 | 2 | ||

| Make up for the loneliness of online learning | Feel like being with everyone, feel not alone, etc. | 2 | 2 | ||

| Instructor’s feedback and guidance (4 themes, 14 codes) | Students | ||||

| Case | Code | ||||

| Assist in designing and improving monitoring journal | Develop the content of monitoring journal, better at designing journals, give me a lot of inspiration, seeing designs from other classmates, etc. | 4 | 6 | ||

| Help students identify areas for improvement and define action steps for progress | Know where to improve, clarify what to do, etc. | 2 | 2 | ||

| Increase individual fulfillment, motivation, and participation in SRL activities | Make me feel more fulfilled, more motivated, more active to attend group discussions, etc. | 2 | 5 | ||

| Enable students to achieve greater transformation | The transformation is greater than before, etc. | 1 | 1 | ||

| Family-school co-education (2 themes, 11 codes) | Parents | ||||

| Case | Code | ||||

| Facilitate parental supervision | Effectively supervise when signing, urge children to achieve goals, urge completion of homework, etc. | 8 | 8 | ||

| Better knowing of children’s learning status | Knowing children’s learning status, knowing the degree of completion of homework, etc. | 3 | 3 | ||

| Students (N = 51): | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The use of self-learning management notebook helps to manage my learning. | 3.90 | 0.900 |

| 2. | Daily self-monitoring journal is helpful for me to improve my learning efficiency. | 3.90 | 0.781 |

| 3. | I often reflect on my learning based on my monitoring journal. | 3.94 | 0.835 |

| 4. | Weekly group discussion activities for 5 min are helpful to my study. | 3.71 | 0.986 |

| 5. | I share my problems with peers when discussion online so we know what we are struggling with and how to solve our problems. | 4.02 | 0.969 |

| Parents (N = 56): | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I try to communicate with my child initiatively or help him use journals to analyze learning problems when signing the monitoring journal every day. | 4.29 | 0.731 |

| 2. | I participated in guiding or supervising my child to set goals. | 4.21 | 0.909 |

| 3. | The using of self-monitoring journal helped my child’s study. | 4.04 | 0.990 |

| 4. | I am satisfied with my child’s self-discipline performance during online learning. | 3.57 | 1.006 |

| 5. | After returning to school, I hope to continue to use self-monitoring journal in the class. | 3.93 | 1.042 |

| First Iteration | Second Iteration | Third Iteration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design |

|

|

|

| Implementation |

|

|

|

| Evaluation |

|

|

|

Appendix B. List of Appendix Figures

References

- UNESCO. Education: From Disruption to Recovery. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Pulham, E.; Graham, C.R. Comparing K-12 Online and Blended Teaching Competencies: A Literature Review. Distance Educ. 2018, 39, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhao, L.; Su, Y.-S. Effects of Online Self-Regulated Learning on Learning Ineffectiveness in the Context of COVID-19. IRRODL 2022, 23, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, C.A.; Anderson, M.L. Distance Education—Definition, History and Theory. In Distance Education: Review of the Literature; AECT Publication Sales: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-89240-071-3. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.G.; Kearsley, G. Distance Education: A System View. Comput. Educ. 1996, 29, 209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, L.; Garner, J.K. Challenges in Supporting Self-Regulation in Distance Education Environments. J. Comput. High Educ. 2011, 23, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonysamy, L.; Koo, A.-C.; Hew, S.-H. Self-Regulated Learning Strategies and Non-Academic Outcomes in Higher Education Blended Learning Environments: A One Decade Review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 3677–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, A.L.; Koenka, A.C. The Relation between Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement across Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 28, 425–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-L.; Hwang, G.-J. A Self-Regulated Flipped Classroom Approach to Improving Students’ Learning Performance in a Mathematics Course. Comput. Educ. 2016, 100, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R. Theoretical, Conceptual, Methodological, and Instructional Issues in Research on Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: A Discussion. Metacognition Learn. 2009, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaki, E.; Koutsouba, M.; Lykesas, G.; Venetsanou, F.; Savidou, D. The Support and Promotion of Self-Regulated Learning in Distance Education. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2017, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Devolder, A.; van Braak, J.; Tondeur, J. Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Computer-Based Learning Environments: Systematic Review of Effects of Scaffolding in the Domain of Science Education. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2012, 28, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.S.; van Leeuwen, A.; Janssen, J.; Conijn, R.; Kester, L. Supporting Learners’ Self-Regulated Learning in Massive Open Online Courses. Comput. Educ. 2020, 146, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Gu, X. Effect of Teacher Autonomy Support on the Online Self-Regulated Learning of Students during COVID-19 in China: The Chain Mediating Effect of Parental Autonomy Support and Students’ Self-Efficacy. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, M.; Ma, Y.; Hu, Y.; Luo, H. K-12 Students’ Online Learning Experiences during COVID-19: Lessons from China. Front. Educ. China 2021, 16, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C.; Buettner, G. Teachers’ Direct and Indirect Promotion of Self-Regulated Learning in Primary and Secondary School Mathematics Classes-Insights from Video-Based Classroom Observations and Teacher Interviews. Metacognition Learn. 2018, 13, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikan, E.R.; Lüftenegger, M.; Holzer, J.; Korlat, S.; Spiel, C.; Schober, B. Learning during COVID-19: The Role of Self-Regulated Learning, Motivation, and Procrastination for Perceived Competence. Z Erzieh. 2021, 24, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, F.; Schreiner, C.; Hagleitner, W.; Jesacher-Rößler, L.; Roßnagl, S.; Kraler, C. Predicting Coping with Self-Regulated Distance Learning in Times of COVID-19: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 701255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-C.; Yao, C.-B.; Wu, C.-Y. A Strategy for Enhancing English Learning Achievement, Based on the Eye-Tracking Technology with Self-Regulated Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R. Systematic Literature Review on Self-Regulated Learning in Massive Open Online Courses. AJET 2019, 35, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Alten, D.C.D.; Phielix, C.; Janssen, J.; Kester, L. Effects of Self-Regulated Learning Prompts in a Flipped History Classroom. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou, K. Self-Regulated and Mobile-Mediated Learning in Blended Tertiary Education Environments: Student Insights from a Pilot Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becirovic, S.; Ahmetovic, E.; Skopljak, A. An Examination of Students Online Learning Satisfaction, Interaction, Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulated Learning. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2022, 11, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, J.; Panadero, E.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Effects of Mobile-App Learning Diaries vs Online Training on Specific Self-Regulated Learning Components. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 2351–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Tseng, K.-H.; Liang, C.; Liao, Y.-M. Constructing and Evaluating Online Goal-Setting Mechanisms in Web-Based Portfolio Assessment System for Facilitating Self-Regulated Learning. Comput. Educ. 2013, 69, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurjanah, S.; Mulyaning, E.C.; Nurlaelah, E. Increased Mathematical Relational Understanding Ability and Self Regulated Learning of High School Students through Edmodo Online Learning. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1806, 012066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Chu, S.K.W.; Shen, X.; Yeung, S.S. The Impact of an Online Gamified Approach Embedded with Self-Regulated Learning Support on Students’ Reading Performance and Intrinsic Motivation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-H. Developing Web-Based Assessment Strategies for Facilitating Junior High School Students to Perform Self-Regulated Learning in an e-Learning Environment. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.A., Jr.; Rice, M.; Yang, S.; Jackson, H.A. Self-Regulated Learning in Online Learning Environments: Strategies for Remote Learning. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Greene, J.A. Historical, Contemporary, and Future Perspectives on Self-Regulated Learning and Performance. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance, 2nd ed.; Schunk, D.H., Greene, J.A., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-1-315-69704-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C.; et al. How We Design Feasibility Studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, G.; Rubenstein, L.; Barton, T.; Halterman, A. Enhancing Motivation by Developing Cyclical Self-Regulated Learning Skills. Theory Pract. 2022, 61, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E. A Review of Self-Regulated Learning: Six Models and Four Directions for Research. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Attaining Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Perspective. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 13–39. ISBN 978-0-12-109890-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Tsikalas, K.E. Can Computer-Based Learning Environments (CBLES) Be Used as Self-Regulatory Tools to Enhance Learning? Educ. Psychol. 2005, 40, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. From Cognitive Modeling to Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Career Path. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 48, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-Regulated Learning: Theories, Measures, and Outcomes. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 541–546. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P.R. A Conceptual Framework for Assessing Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning in College Students. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: Which Are the Key Subprocesses? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1986, 11, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Poon, W.L. Self-Regulated Learning Strategies & Academic Achievement in Online Higher Education Learning Environments: A Systematic Review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R.; Falkner, K.; Vivian, R. Systematic Literature Review: Self-Regulated Learning Strategies Using e-Learning Tools for Computer Science. Comput. Educ. 2018, 123, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekala, S.; Radhakrishnan, G. Promoting Self-Regulated Learning Through Metacognitive Strategies. IUP J. Soft Ski. 2019, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P.R.; Garcia, T. Student Goal Orientation and Self-Regulation in the College Classrooms. In Advances in Motivation & Achievement: Goals and Self-Regulatory Process; Maehr, M.L., Pintrich, P.R., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, UK, 1991; Volume 7, pp. 371–402. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Pons, M.M. Development of a Structured Interview for Assessing Student Use of Self-Regulated Learning Strategies. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1986, 23, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G.P.; Locke, E.A. Goal Setting Theory. In New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance; Locke, E.A., Latham, G.P., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 44–62. ISBN 978-0-415-88548-5. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, A.; Hood, N.; Milligan, C.; Mustain, P. Learning in Moocs: Motivations and Self-Regulated Learning in Moocs. Internet High. Educ. 2016, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lehman, J.D. Using Achievement Goal-Based Personalized Motivational Feedback to Enhance Online Learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 553–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; King, R.B.; Rao, N. The Role of Social-Academic Goals in Chinese Students’ Self-Regulated Learning. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.; Lepelley, D. Stretch Goals: Risks, Possibilities, and Best Practices. In New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance; Locke, E.A., Latham, G.P., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 82–98. ISBN 978-0-415-88548-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.C.; Simão, A.M.V.; da Silva, A.L. Does Training in How to Regulate One’s Learning Affect How Students Report Self-Regulated Learning in Diary Tasks? Metacognition Learn. 2015, 10, 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Ertmer, P.A. Self-Evaluation and Self-Regulated Computer Learning. 1998. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED422275 (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Liang, C.; Chang, C.-C.; Shu, K.-M.; Tseng, J.-S.; Lin, C.-Y. Online Reflective Writing Mechanisms and Its Effects on Self-Regulated Learning: A Case of Web-Based Portfolio Assessment System. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1647–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, M.; Wijnia, L. The Relation between Task-Specific Motivational Profiles and Training of Self-Regulated Learning Skills. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 64, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. The Role of Motivation in Promoting and Sustaining Self-Regulated Learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1999, 31, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. The Effectiveness of Self-Regulated Learning Scaffolds on Academic Performance in Computer-Based Learning Environments: A Meta-Analysis. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Bonner, S.; Kovach, R. Developing Self-Regulated Learners: Beyond Achievement to Self-Efficacy; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; ISBN 1-55798-392-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E. Interaction and Cognitive Engagement: An Analysis of Four Asynchronous Online Discussions. Instr. Sci. 2006, 34, 451–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellhäuser, H.; Liborius, P.; Schmitz, B. Fostering Self-Regulated Learning in Online Environments: Positive Effects of a Web-Based Training with Peer Feedback on Learning Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 813381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minke, K.M.; Anderson, K.J. Family-School Collaboration and Positive Behavior Support. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2005, 7, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormrod, E.J. Human Learning, 8th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-13-489366-2. [Google Scholar]

- Plomp, T. Educational Design Research: An Introduction. In Educational Design Research-Part A: An Introduction; Plomp, T., Nieveen, N., Eds.; Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development (SLO): Enschede, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 10–51. ISBN 978-90-329-2334-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Hannafin, M.J. Design-Based Research and Technology-Enhanced Learning Environments. ETR&D 2005, 53, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Letzel, V.; Pozas, M.; Schneider, C. Energetic Students, Stressed Parents, and Nervous Teachers: A Comprehensive Exploration of Inclusive Homeschooling during the COVID-19 Crisis. Open Educ. Stud. 2020, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, J. Head Teachers, Peer Effects, and Student Achievement. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 41, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varpio, L.; Ajjawi, R.; Monrouxe, L.V.; O’Brien, B.C.; Rees, C.E. Shedding the Cobra Effect: Problematising Thematic Emergence, Triangulation, Saturation and Member Checking. Med Educ. 2017, 51, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-4739-5323-9. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4739-0249-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R. The Bullet Journal Method: Track the Past, Order the Present, Design the Future; Portfolio: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-525-53333-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R. The Relationships between Self-Efficacy, Task Value, and Self-Regulated Learning Strategies in Massive Open Online Courses. IRRODL 2020, 21, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.K.; Tondeur, J.; Siddiq, F.; Scherer, R. Ready, Set, Go! Profiling Teachers’ Readiness for Online Teaching in Secondary Education. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2020, 30, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukman, K.B.; Licardo, M. How Cognitive, Metacognitive, Motivational and Emotional Self-Regulation Influence School Performance in Adolescence and Early Adulthood. Educ. Stud. 2010, 36, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M. Self-Regulated Learning: A New Concept Embraced by Researchers, Policy Makers, Educators, Teachers, and Students. Learn. Instr. 1997, 7, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, S. Observations of a Working Class Family: Implications for Self-Regulated Learning Development. Educ. Stud. 2012, 48, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adl, A.; Alkharusi, H. Relationships between Self-Regulated Learning Strategies, Learning Motivation and Mathematics Achievement. CJES 2020, 15, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcpherson, G.; Zimmerman, B. Self-Regulation of Musical Learning: A Social Cognitive Perspective on Performance Skills. In Menc Handbook of Research on Music Learning; Colwell, R., Webster, P.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 130–175. [Google Scholar]

- Araka, E.; Maina, E.; Gitonga, R.; Oboko, R. Research Trends in Measurement and Intervention Tools for Self-Regulated Learning for e-Learning Environments—Systematic Review (2008–2018). Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2020, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Design Principle | Description | Main Reason | Supporting Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1. Stimulate motivation. | Stimulate external and internal motivations to promote the more active and sustainable engagement of students’ SRL. | Extra time and effort need to be invested. | Pintrich [56]; Wang et al. [50] |

| P2. Implement individual tangible records. | Use individual tangible records to plan and monitor students’ own learning processes. Embedded guides and prompts are designed to facilitate self-reflection. | Skill learning requires practice and scaffolding. | Broadbent et al. [25]; Zheng [57]; Zimmerman et al. [58] |

| P3. Create opportunities for social interaction. | Create online communication opportunities to obtain peer and instructor feedback on SRL processes to facilitate further engagement with and understanding of SRL skills. | Learning requires feedback and interaction. | Hattie and Timperley [59]; Zhu [60]; Zimmerman and Tsikalas [37] |

| P4. Build a family–school co-education environment. | Build a good family–school co-educative environment to promote timely communication between families and schools and create opportunities for parents to participate in children’s SRL and transition them from coregulation to self-regulation. | Parental involvement facilitates skill improvement. | Minke and Anderson [62]; Ormrod [63]; Zimmerman et al. [58] |

| Data Collection Methods | Data Source/Measurement | Main Purpose | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | Online teaching and learning process during class meeting time, class home–school group, and each group’s online discussion. | Capture class arrangement, teacher’s instruction, and students’ behavior and experiences. | Field notes, discourse data on the social media platform, and 13 video recordings. |

| Artifact collection | Materials used in the class or submitted by students. | Analyze how students used monitoring journals and their SRL skill-learning processes. | 1701 pictures of monitoring journals, goal-setting and planning forms, class rules, etc. |

| Semi-structured interviews | Nine purposefully chosen students (five boys, four girls) from different groups and levels, the head teacher, and three parents, all interviewed online. | Gather in-depth feedback and comments on the main SRL strategies, including students’ learning experience, benefits, and challenges. | Students: 33,495-word interview transcript (three rounds of interviews); teachers: 4610-word interview transcript; parents: 15,116-word interview transcript. |

| Feedback questionnaire | All parents and students; five five-point Likert scale items (1: strongly disagree; 5: strongly agree) and open-ended questions. | Gather feedback on the design for family–school co-education aspects and perceptions of monitoring recordings and group communication. | 56 valid parent questionnaires and 51 valid student questionnaires; 31 comments and 14 relevant suggestions. |

| Criteria | Element | Excellent (3) | Satisfactory (2) | Needs Improvement (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feasibility | Perceived ease of use | It is convenient to use and little training is needed. | Some simple training is required, but it is feasible. | It is inconvenient to use or requires long-term guidance. |

| Appeal | Parents, students, and teachers all like this form. | Parents, students, and teachers can find this form acceptable. | Parents, students, and teachers are resistant to this form. | |

| Effectiveness | Perceived usefulness | Small time investment; all intended purposes are fulfilled. | Some time investment and some intended purposes are fulfilled, but investment is not proportional to the intended purpose. | A lot of time investment, but few intended purposes are fulfilled. |

| SRL skills and performance improvement | Students often use strategies; performance shows significant progress. | Students occasionally use strategies; performance shows some progress. | Students rarely use strategies; no obvious progress in performance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuo, M.; Zhong, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Liang, L.; Gao, W.; Luo, H. Supporting Home-Based Self-Regulated Learning for Secondary School Students: An Educational Design Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031199

Zuo M, Zhong Q, Wang Q, Yan Y, Liang L, Gao W, Luo H. Supporting Home-Based Self-Regulated Learning for Secondary School Students: An Educational Design Study. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031199

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuo, Mingzhang, Qifang Zhong, Qiyun Wang, Yujie Yan, Lingling Liang, Wenjing Gao, and Heng Luo. 2024. "Supporting Home-Based Self-Regulated Learning for Secondary School Students: An Educational Design Study" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031199

APA StyleZuo, M., Zhong, Q., Wang, Q., Yan, Y., Liang, L., Gao, W., & Luo, H. (2024). Supporting Home-Based Self-Regulated Learning for Secondary School Students: An Educational Design Study. Sustainability, 16(3), 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031199