Exploring Higher Education Mobility through the Lens of Academic Tourism: Portugal as a Study Case

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

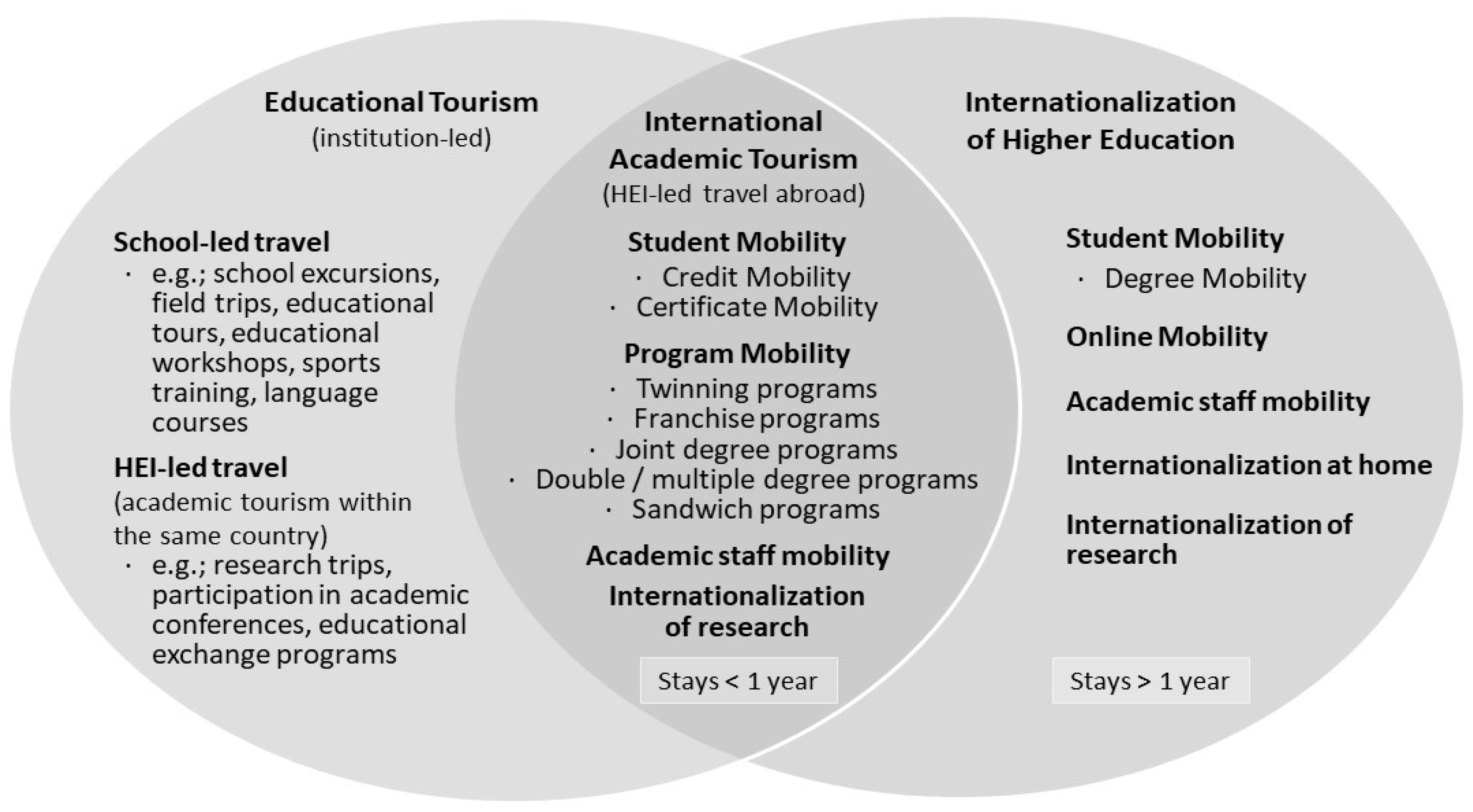

2.1. Academic Tourism

2.2. Academic Tourism and the Internationalisation of Higher Education

- Credit mobility, which occurs when students (known as exchange students, such as those in the European Erasmus programme) undertake a short-term mobility experience and transfer credits from an HEI in the host country back to their home degree [35,36]. These students remain enrolled in their home countries while receiving credits from their host institutions, and the length of credit mobility varies from six weeks to one year in the US and from two months to one year in Europe [34].

- Certificate mobility, which involves shorter stays abroad to improve skills (e.g., summer programme, cultural or language courses, conferences, workshops) [34].

2.3. International Students as Academic Tourists

3. Portugal as an International Academic Tourist Destination

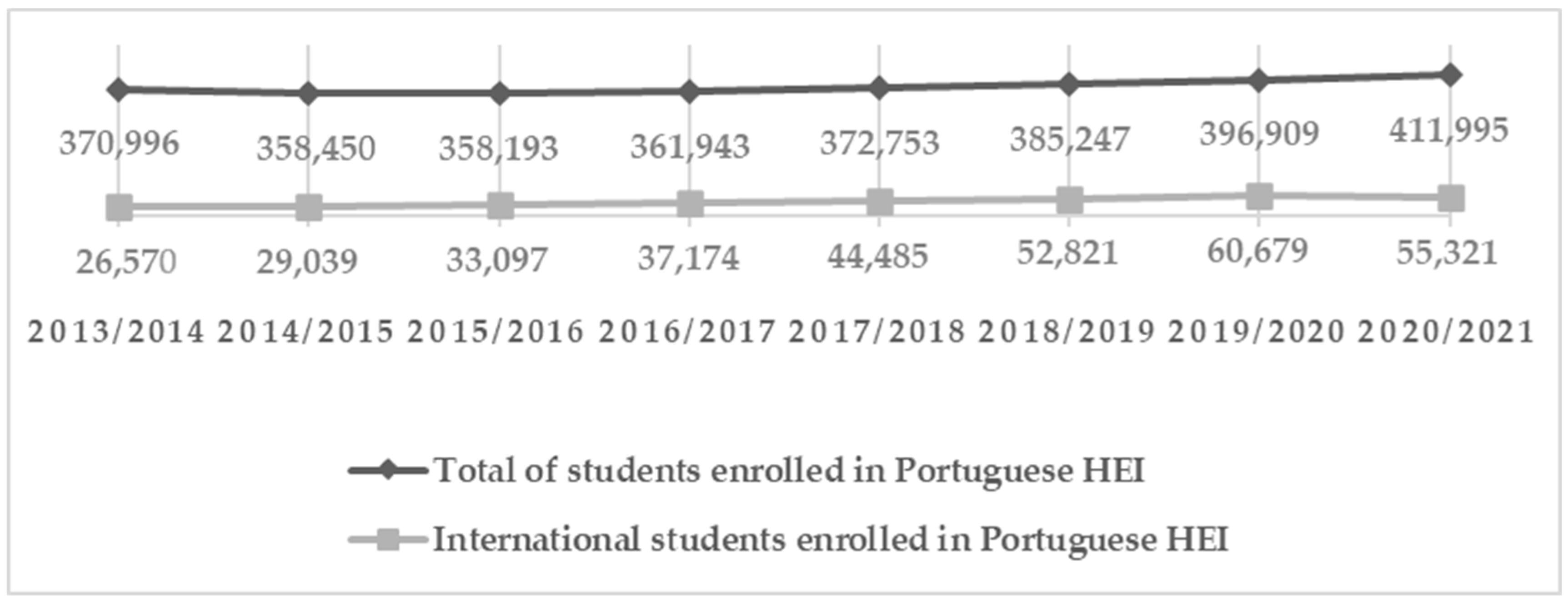

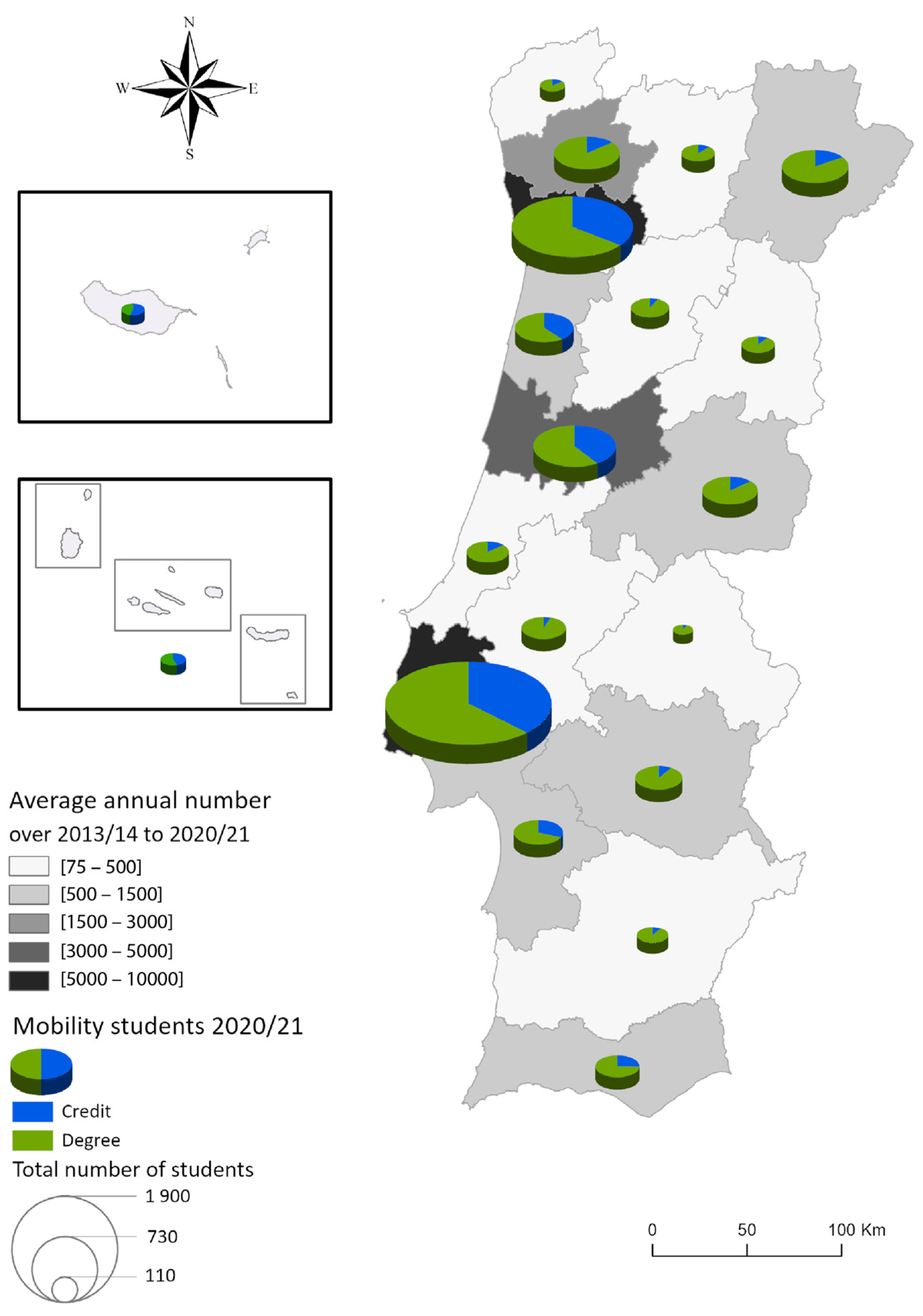

3.1. International Student Mobility

3.2. Academic Tourists Versus International Degree Students

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications for Theory

5.2. Implications for Practice

6. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Karzunina, D.; West, J.; Moran, J.; Philippou, G. Student Mobility & Demographic Changes; QS Intelligence Unit: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.; de Wit, H. Internationalization of Higher Education: Past and Future. Int. High. Educ. 2018, 95, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, H.; Hunter, F.; Howard, L.; Egron-Polak, E. Internationalisation of higher education. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Internationalization of Higher Education in the Global South; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2015; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Roget, F.; Rodríguez, X.A. Academic tourism: Conceptual and theoretical issues. In Academic Tourism: Perspectives on International Mobility in Europe; Cerdeira Bento, J.P., Martínez-Roget, F., Pereira, E.T., Rodríguez, X.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Latukha, M.; Panibratov, A. International student mobility: A systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 852–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmaczewska, J. Exploring the determinants of choosing an academic destination under a short-term mobility: A cross-cultural comparison of Poland and Portugal. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2022, 32, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M. Academic tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Dimitrius Buhalis, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, X.A.; Martínez-Roget, F.; Pawlowska, E. Academic tourism demand in Galicia, Spain. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maringe, F.; Carter, S. International students’ motivations for studying in UK HE: Insights into the choice and decision making of African students. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2007, 21, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarol, T.; Soutar, G.N. Push-pull factors influencing international student destination choice. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2002, 16, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, S.; Huisman, J. International student destination choice: The influence of home campus experience on the decision to consider branch campuses. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2011, 21, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, J.P.C. The Determinants of International Academic Tourism Demand in Europe. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matahir, H.; Tang, C.F. Educational tourism and its implications on economic growth in Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGladdery, C.A.; Lubbe, B.A. Rethinking educational tourism: Proposing a new model and future directions. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F. The threshold effects of educational tourism on economic growth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.; King, B.; Wilkins, H. The travel behaviours of international students. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Mapping Educational Tourists’ Experience in the UK: Understanding international students. Third World Q. 2008, 29, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmaczewska, J.; Jameson, S. “Education First” or “Tourism First”—What Influences the Choice of Location for International Exchange Students: Evidence from Poland. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2023, 35, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.D.J.; Ali, L.; Hristoforova Maydon, D.; Sigaeva, N.; Öztüren, A.; Kiliç, H. Promoting Face-To-Face Education Under Perceived Risk via Learning Engagement and Positive Attitude: Perspectives from an Edu-Tourist Destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Fan, A.; Cai, L.A. Educational Travel and Personal Development: Deconstructing the Short-Term Study Abroad Experience. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Reconceptualising international academic mobility in the global knowledge system: Towards a new research agenda. High. Educ. 2022, 84, 1317–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, G.D.; Guthrie, J.; Martin-Sardesai, A. Public universities and impacts of COVID-19 in Australia: Risk disclosures and organisational change. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.T.; Agyeiwaah, E. Exploring Chinese students’ issues and concerns of studying abroad amid COVID-19 pandemic: An actor-network perspective. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 30, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, M. Mobile student experience: The place of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 90, 103253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McGladdery, C.A. Educational tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Buhalis, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, B.W. Managing Educational Tourism; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, J.M.; Ariffin AA, M. Do travel images affect international students’ on-site academic value? New evidence from the Malaysia’s ‘higher edutourism’ destination. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 499–514. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, S.; Paviotti, G.; Cavicchi, A. Educational tourism and local development: The role of universities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.N.; Breda, Z.; Eusébio, C. Turismo académico: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. J. Tour. Dev. 2019, 32, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, X.A.; Martínez-Roget, F. Academic Tourism and Sustainability. In Academic Tourism: Perspectives on International Mobility in Europe; Cerdeira Bento, J.P., Martínez-Roget, F., Pereira, E.T., Rodríguez, X.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbley, L.E. “Intelligent internationalization”: A 21st century imperative. Int. High. Educ. 2015, 80, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, H.; Altbach, P. 70 Years of Internationalization in Tertiary Education: Changes, Challenges and Perspectives. In The Promise of Higher Education: Essays in Honour of 70 Years of IAU; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, R.M.; Rumbley, L.E.; Brajkovic, L.; Mihut, G. Internationalizing Higher Education Worldwide: National Policies and Programs; American Council of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. What is the Profile of Internationally Mobile Students? In Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J. Student mobility and internationalization: Trends and tribulations. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2012, 7, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelen, J.; Jones, E. Redefining Internationalization at Home. In The European Higher Education Area; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-H. East-Asian Students’ Choice of Canadian Graduate Schools. Int. J. Educ. Adv. 2007, 7, 271–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, J.; Smith, W.W.; Pitts, R.E. Exploring Factors Influencing Student Study Abroad Destination Choice. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2010, 10, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.S.; Qi, H.; Guo, Q. Factors influencing Chinese tourism students’ choice of an overseas PhD program. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolster, R. Academic attractiveness of countries; a possible benchmark strategy applied to the Netherlands. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2014, 4, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Amaro, D.M.; Marques, A.M.A.; Alves, H. The impact of choice factors on international students’ loyalty mediated by satisfaction. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2019, 16, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calitz, A.P.; Cullen, M.D.M.; Jooste, C. The influence of safety and security on students’ choice of university in South Africa. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2020, 24, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling-Hetherington, L. Transnational higher education and the factors influencing student decision-making: The experience of an Irish university. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2020, 24, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, H.P.; Soeprihanto, J. GadjahMada University as a Potential Destination for Edutourism. In Heritage, Culture and Society: Research Agenda and Best Practices in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry, Proceedings of the 3rd International Hospitality and Tourism Conference, ISOT 2016, Yokohama, Japan, 10–12 October 2016; CRC Press/Balkema: Boca Raton, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- MADR/MEC. Uma Estratégia Para a Internacionalização do Ensino Superior Português; Ministry of Regional Development and Ministry of Education: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014.

- Sin, C.; Cardoso, S.; Tavares, O. Atração e recrutamento de estudantes internacionais em Portugal: Políticas nacionais e institucionais. Rev. Lusófona De Educ. 2020, 47, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study & Research in Portugal. 2021. Available online: https://www.study-research.pt/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Peace Index 2023: Measuring Peace in a Complex World. 2023. Available online: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/GPI-2023-Web.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- DGEEC—Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência, Vagas e Inscritos. 2021. Available online: https://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/EstatVagasInsc/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Estatísticas do Turismo: 2020. ISSN 0377-2306. ISBN 978-989-25-0569-5. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/280866098 (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- McCarthy, J.E.; Dewitt, B.D.; Dumas, B.A.; McCarthy, M.T. Modeling the relative risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection to inform risk-cost-benefit analyses of activities during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari, A.; Nardon, L.; Zhang, H. A transnational lens into international student experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Netw. 2023, 23, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turismo de Portugal. Turismo em Portugal 2019. Travel BI by Turismo de Portugal. 2021. Available online: https://travelbi.turismodeportugal.pt/pt-pt/Paginas/turismo-em-portugal-2019.aspx (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- López, X.P.; Fernández, M.F.; Incera, A.C. The Economic Impact of International Students in a Regional Economy from a Tourism Perspective. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. New connectivity in the fragmented world. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2022, 53, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, C.; Trupp, A.; Stephenson, M.L. Deciphering tourism and the acquisition of knowledge: Advancing a new typology of ‘Research-related Tourism (RrT)’. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. The Power of Youth Travel; AM Reports; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Culubret, C.; González, A.; Iglesias, M.; Moreno, S.; Roigé, V. Academic Tourism in Barcelona (Spain) in the COVID-19 Era. Region 2022, 9, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, M. More than a checklist: Meaningful Indigenous inclusion in higher education. Soc. Incl. 2016, 4, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mallipeddi, R.R. Impact of cybersecurity on operations and supply chain management: Emerging trends and future research directions. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 4488–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, C.; Reis, P.; Abrantes, J.L. The influence of terrorism in tourism arrivals: A longitudinal approach in a Mediterranean country. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van‘t Klooster, E.; Van Wijk, J.; Go, F.; Van Rekom, J. Educational travel: The overseas internship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amaro, D.; Caldeira, A.M.; Seabra, C. Exploring Higher Education Mobility through the Lens of Academic Tourism: Portugal as a Study Case. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041359

Amaro D, Caldeira AM, Seabra C. Exploring Higher Education Mobility through the Lens of Academic Tourism: Portugal as a Study Case. Sustainability. 2024; 16(4):1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041359

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmaro, Dina, Ana Maria Caldeira, and Cláudia Seabra. 2024. "Exploring Higher Education Mobility through the Lens of Academic Tourism: Portugal as a Study Case" Sustainability 16, no. 4: 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041359

APA StyleAmaro, D., Caldeira, A. M., & Seabra, C. (2024). Exploring Higher Education Mobility through the Lens of Academic Tourism: Portugal as a Study Case. Sustainability, 16(4), 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041359