Heading for the Frontline: Mood, Stress, Resilience, and Coping of Nursing Graduates during a Global Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Assessment of Mood

2.3.2. Assessment of Perceived Stress

2.3.3. Assessment of Resilience and Coping

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Reliability of Measures

3.3. Data Screening and Descriptive Statistics

3.4. Mood Scores

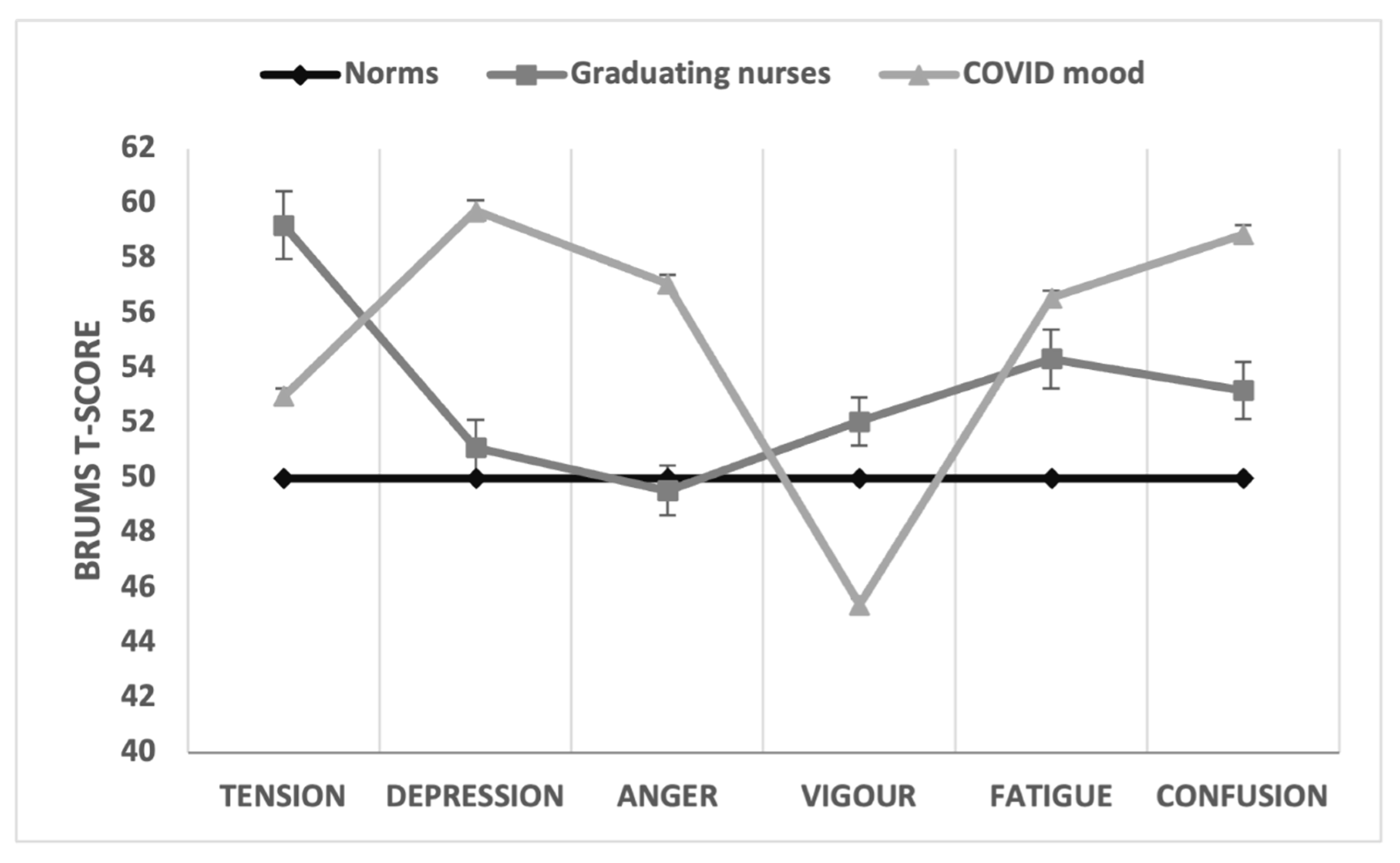

3.4.1. Comparison with Population Norms

3.4.2. Between-Group Comparisons of Mood

3.5. Perceived Stress

3.6. Resilience and Coping

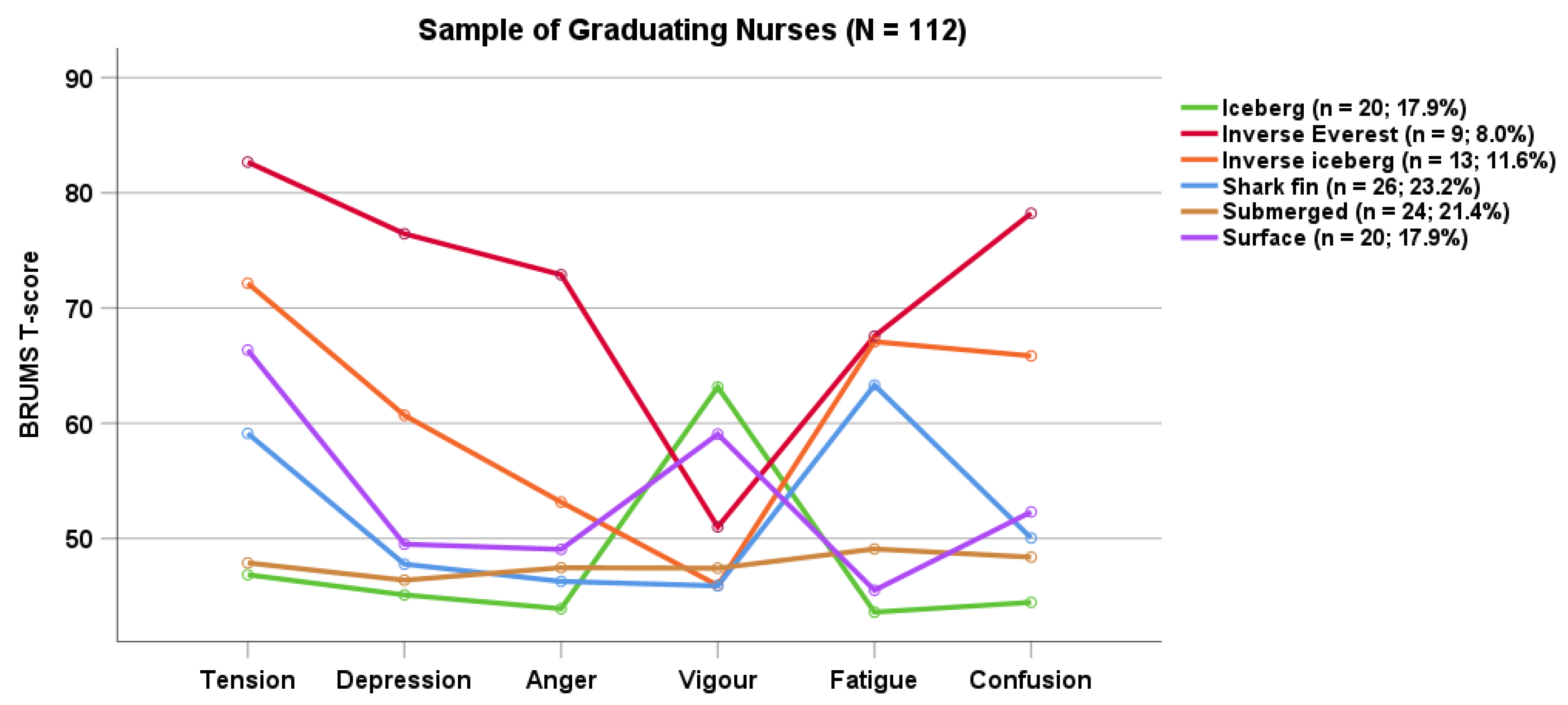

3.7. Cluster Analysis of Mood Scores

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Research

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Health and Aged Care. Nurses and Midwives in Australia. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government. 2023. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/nurses-and-midwives/in-australia (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association. One in Four Primary Health Care Nurses Plans to Quit. 2022. Available online: https://www.apna.asn.au/about/media/one-in-four-primary-health-care-nurses-plans-to-quit (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Lo, W.Y.; Chien, L.Y.; Hwang, F.M.; Huang, N.; Chiou, S.T. From job stress to intention to leave among hospital nurses: A structural equation modelling approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Reverté-Villarroya, S.; Ortega, L.; Lavedán, A.; Masot, O.; Burjalés-Martí, M.D.; Ballester-Ferrando, D.; Fuentes-Pumarola, C.; Botigué, T. The influence of COVID-19 on the mental health of final-year nursing students: Comparing the situation before and during the pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health. Nurs. 2021, 30, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health. Under the Radar: The Mental Health of Australian University Students; Orygen: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://www.orygen.org.au/About/News-And-Events/Mental-health-of-Australian-university-students-fl (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Tung, Y.J.; Lo, K.K.H.; Ho, R.C.M.; Tam, W.S.W. Prevalence of depression among nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs. Educ. Today 2018, 63, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, P.C.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; Terry, V.R. Mood responses associated with COVID-19 restrictions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, e589598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, K.; Wholeben, M. COVID-19: Outcomes for trauma-impacted nurses and nursing students. Nurs. Educ. Today 2020, 93, e104525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.; Antunes, R.; Fernandes, J.B.; Reisinho, J.; Rodrigues, R.; Sardinha, J.; Vaz, C.; Miranda, L.; Simões, A. Perceptions and representations of senior nursing students about the transition to professional life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, M.S.; Marrocco, F.A.; Kleinman, M.; Thomas, J.G.; Mostkoff, K.; Côté, J.; Davies, M. Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening. JAMA 2005, 293, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, W.P.; Brown, D.R.; Raglin, J.S.; O’Connor, P.J.; Ellickson, K. Psychological monitoring of overtraining and staleness. Br. J. Sports Med. 1987, 21, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, P.C.; Parsons-Smith, R.L. Mood profiling for sustainable mental health among athletes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijk, C.H.; Martin, J.H.; Hans-Arendse, C. Clinical utility of the Brunel Mood Scale in screening for post-traumatic stress risk in a military population. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sties, S.W.; Gonzáles, A.I.; Netto, A.S.; Wittkopf, P.G.; Lima, D.P.; De Carvalho, T. Validation of the Brunel Mood Scale for Cardiac Rehabilitation Program. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2014, 20, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braslis, K.G.; Santa-Cruz, C.; Brickman, A.L.; Soloway, M.S. Quality of life 12 months after radical prostatectomy. Br. J. Urol. 1995, 75, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J.L.; De Martino, M.M.; Figueiredo, T.H. Present mood states in Brazilian night nurses. Psychol. Rep. 2003, 93, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.S.; Moreira, C.Z.; Guo, J.; Noce, F. Effects of a 12-hour shift on mood states and sleepiness of neonatal intensive care unit nurses. J. Sch. Nurs. Univ. São Paulo 2017, 51, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownlow, C.; Eacersall, D.; Nelson, C.W.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; Terry, P.C. Risks to mental health of higher degree by research (HDR) students during a global pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moxham, L.J.; Fernandez, R.; Kim, B.; Lapkin, S.; Ten Ham-Baloyi, W.; Al Mutair, A. Employment as a predictor of mental health, psychological distress, anxiety, and depression in Australian pre-registration nursing students. J. Prof. Nurs. 2018, 34, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, P.C.; Lane, A.; Fogarty, G. Construct validity of the Profile of Mood States—Adolescents for use with adults. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warttig, S.L.; Forshaw, M.J.; South, J.; White, A.K. New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4). J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, V.G.; Wallston, K.A. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment 2004, 11, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engard, N.C. LimeSurvey. http://limesurvey.org. Public Serv. Q. 2009, 5, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007)—Updated 2018. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- STROBE. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.L.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, P.C.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; King, R.; Terry, V.R. Influence of sex, age, and education on mood profile clusters. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e245341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons-Smith, R.L. In the Mood: Online Mood Profiling, Mood Response Clusters, and Mood-Performance Relationships in High-Risk Vocations. Available online: https://research.usq.edu.au/item/q3941/in-the-mood-online-mood-profiling-mood-response-clusters-and-mood-performance-relationships-in-high-risk-vocations (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Budgett, R. Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: The overtraining syndrome. Br. J. Sports Med. 1988, 32, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.; Sprajcer, M.; Flenady, T.; Sahay, A. Fatigue in nurses and medication administration errors: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 5445–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, A.; Ferrentino, M.; Ferrario, E.; Papini, M.; Lusignami, M. Factors contributing to medication errors: A descriptive qualitative study of Italian nursing students. Nurs. Educ. Today 2022, 118, e105511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroers, G.; Ross, J.G.; Moriarty, H. Nurses’ perceived causes of medication administration errors: A qualitative systematic review. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2021, 47, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolic, S.; Ng, L.; Southern, J.; Sheridan, G. Medication errors by nursing students on clinical practice: An integrative review. Nurs. Educ. Today 2022, 112, e105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, W.P. Selected psychological factors limiting performance: A mental health model. In Limits of Human Performance; Clarke, D.H., Eckert, H.M., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1985; pp. 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Raglin, J.S. Psychological factors in sport performance. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, R.; Fernandez, R.; Moxham, L.; Tapsell, A.; Halcomb, E.; Lord, H.; Alomari, A.; Hunt, L. Generational differences in psychological wellbeing and preventative behaviours among nursing students during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Contemp. Nurs. 2021, 57, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Universities Australia. More Clinical Placements Needed to Grow Nursing Workforce [Media Release]. Deakin, ACT, Universities Australia. Available online: https://universitiesaustralia.edu.au/media-item/more-clinical-placements-needed-to-grow-nursing-workforce/ (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Bakker, E.J.M.; Kox, J.H.A.M.; Boot, C.R.L.; Francke, A.L.; van der Beek, A.J.; Roelofs, P.D.D.M. Improving mental health of student and novice nurses to prevent dropout: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2494–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-L.; Wang, T.; Bressington, D.; Nic Giolla Easpaig, B.; Wikander, L.; Tan, J.-Y. Factors influencing retention among regional, rural, and remote undergraduate nursing students in Australia: A systematic review of current research evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, T.J.; Lum, C. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Patient Experience in the Asian Region; Insync-Press-Ganey: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://insync.com.au/insights/covid-impact-patient-experience-asia/ (accessed on 19 December 2023).

| Source | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS-4 | 6.17 | 2.06 | 1 | 12 | 0.22 | 0.31 |

| BRCS | 15.24 | 2.21 | 9 | 20 | −0.29 | 0.34 |

| BRUMS-Ten | 6.07 | 4.39 | 0 | 16 | 0.64 | −0.43 |

| BRUMS-Dep | 2.52 | 3.34 | 0 | 14 | 1.59 | 2.07 |

| BRUMS-Ang | 2.05 | 3.00 | 0 | 14 | 2.19 | 5.35 |

| BRUMS-Vig | 8.09 | 3.65 | 0 | 16 | 0.16 | −0.48 |

| BRUMS-Fat | 6.99 | 4.47 | 0 | 16 | 0.39 | −0.84 |

| BRUMS-Con | 3.51 | 3.44 | 0 | 15 | 1.20 | 0.86 |

| Subscale | M | SD | 95% CI | t | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tension | 59.21 | 13.16 | [56.75, 61.68] | 7.41 † | 0.70 |

| Depression | 51.11 | 10.69 | [49.11, 53.11] | 1.10 | - |

| Anger | 49.54 | 9.64 | [47.73, 51.34] | −0.51 | - |

| Vigour | 52.06 | 9.17 | [50.35, 53.78] | 2.38 * | 0.22 |

| Fatigue | 54.34 | 11.34 | [52.22, 56.46] | 4.05 † | 0.38 |

| Confusion | 53.19 | 11.06 | [51.12, 55.26] | 3.05 § | 0.29 |

| Variable Group | n | Tension | Depression | Anger | Vigour | Fatigue | Confusion | PSS-4 | BRCS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Residency | |||||||||||||||||

| Domestic | 88 | 58.49 | 12.62 | 50.24 | 10.08 | 48.97 | 8.65 | 50.11 | 8.17 | 55.19 | 11.34 | 52.41 | 10.52 | 6.14 | 2.23 | 15.03 | 2.08 |

| International | 24 | 61.88 | 14.95 | 54.29 | 12.38 | 51.63 | 12.65 | 59.21 | 9.26 | 51.21 | 11.00 | 56.04 | 12.65 | 6.29 | 1.27 | 16.00 | 2.54 |

| Employment | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 51 | 59.12 | 13.25 | 48.90 | 9.66 | 49.63 | 9.98 | 49.43 | 8.64 | 56.18 | 10.16 | 51.86 | 10.28 | 5.82 | 2.10 | 15.47 | 1.90 |

| No | 61 | 59.30 | 13.19 | 52.95 | 11.23 | 49.46 | 9.43 | 54.26 | 9.09 | 52.80 | 12.10 | 54.30 | 11.63 | 6.46 | 2.00 | 15.05 | 2.43 |

| Location | |||||||||||||||||

| On-Campus | 56 | 60.55 | 13.57 | 53.36 | 11.85 | 50.12 | 10.95 | 54.02 | 9.47 | 54.14 | 11.38 | 54.30 | 12.11 | 6.57 | 1.84 | 15.20 | 2.41 |

| External | 56 | 57.88 | 12.71 | 48.86 | 8.93 | 48.95 | 8.18 | 50.11 | 8.51 | 54.54 | 11.40 | 52.07 | 9.88 | 5.77 | 2.20 | 15.29 | 2.01 |

| Mode | |||||||||||||||||

| Full-time | 81 | 59.59 | 13.07 | 51.52 | 10.82 | 49.78 | 10.38 | 52.00 | 9.48 | 54.72 | 11.55 | 53.84 | 11.81 | 6.19 | 2.00 | 15.31 | 2.31 |

| Part-time | 31 | 58.23 | 13.55 | 50.03 | 10.42 | 48.90 | 7.49 | 52.23 | 8.47 | 53.35 | 10.88 | 51.48 | 8.74 | 6.13 | 2.23 | 15.06 | 1.93 |

| Age Group | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤30 years | 56 | 60.88 | 13.55 | 51.38 | 9.85 | 49.04 | 9.57 | 53.63 | 9.23 | 54.98 | 11.39 | 53.73 | 11.56 | 6.77 | 1.94 | 15.27 | 2.26 |

| 31+ years | 56 | 57.55 | 12.66 | 50.84 | 11.55 | 50.04 | 9.77 | 50.50 | 8.92 | 53.70 | 11.35 | 52.64 | 10.60 | 5.57 | 2.02 | 15.21 | 2.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terry, V.R.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; Elliott, J.; Roderick, G.; Luyke, P.; Terry, P.C. Heading for the Frontline: Mood, Stress, Resilience, and Coping of Nursing Graduates during a Global Pandemic. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041492

Terry VR, Parsons-Smith RL, Elliott J, Roderick G, Luyke P, Terry PC. Heading for the Frontline: Mood, Stress, Resilience, and Coping of Nursing Graduates during a Global Pandemic. Sustainability. 2024; 16(4):1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041492

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerry, Victoria R., Renee L. Parsons-Smith, Jessica Elliott, Geraldine Roderick, Patricia Luyke, and Peter C. Terry. 2024. "Heading for the Frontline: Mood, Stress, Resilience, and Coping of Nursing Graduates during a Global Pandemic" Sustainability 16, no. 4: 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041492

APA StyleTerry, V. R., Parsons-Smith, R. L., Elliott, J., Roderick, G., Luyke, P., & Terry, P. C. (2024). Heading for the Frontline: Mood, Stress, Resilience, and Coping of Nursing Graduates during a Global Pandemic. Sustainability, 16(4), 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041492