“Power to” for High Street Sustainable Development: Emerging Efforts in Warsaw, Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction: The High Street Sustainability Question

2. “Power to” for High Streets

3. Methods

Interviewing Protocol

4. Results: Urban Collaboration Efforts in Warsaw

4.1. Local Context for High Street Development

4.2. Two Decades of Collaborative Efforts

5. Discussion: Difficulties to High Street Sustainable Development

- Inertia of mutual perception by all the stakeholders (5.1.);

- Dependency on singular leaders and their personal motivation (5.2.);

- Necessity to reinvent the very idea of a high street anew (5.3.);

- Lack of adequate legal tools for cross-sectoral collaboration (BIDs does not play that role anymore) (5.4.);

- The stiffening effect of previously set guidelines (5.5.).

5.1. Vicious Circle of Perception (Context)

5.2. Discouragement of Stakeholders (Pioneers)

5.3. Ambiguity about the Meaning (Middle Ground)

5.4. Hodgepodge of Experience and Knowledge (Actions)

5.5. Derivative Nature of the Guidelines (Goals)

6. Conclusions: Missed but Feasible in Warsaw

- To stop equating a potential high street with any administratively designated street, and instead define a high street based on where its key elements (tenant mix and streetscape quality) are already located.

- To reinitiate the collaborative effort by an entity that is already embedded in municipal power structures, has a broad business and public profile, and due to its physical location, is irrevocably bound to a target high street.

- To appreciate the existing tenant mix and development dynamics, and to seek and amplify a hybrid high street rather than any narrowly defined vision.

- To bring knowledge, experience, and people together within a public not-for-profit think-tank, ultimately with a legal basis for a decision-making process (anything from a multilateral contract up to a Local Revitalization Plan).

- To take a few steps back and reopen the discussion anew.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Portas, M. The Portas Review. An Independent Review into the Future of Our High Streets. 2011. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a795f2fe5274a2acd18c4a6/2081646.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Build Back Better High Streets. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/build-back-better-high-streets (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Regeneration Team. High Streets and Town Centres. Adaptive Strategies; Good Growth by Design: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, R.J. Principles of Urban Retail Planning and Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- West, D. Mainstreet Management. Successful Retail Strategies; Premier Retail Marketing: Golden Grove, South Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. London’s Local High Streets. The Problems, Potential, and Complexities of Mixed Street Corridors. Prog. Plan. 2015, 100, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, J. Walkable City Rules. 101 Steps to Making Better Places; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Istrate, A.L.; Bosák, V.; Novácek, A.; Slach, O. How Attractive for Walking Are the Main Streets of a Shrinking City? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, R. Urban resilience—An urban management perspective. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Puig, N.; Benayas, J.; Manana-Rodríguez, J.; Suarez, M.; Sanz-Casado, E. The Role of Urban Resilience in Research and Its Contribution to Sustainability. Cities 2022, 126, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, A.; Jiang, X. Rethinking walkability: Exploring the relationship between urban form and neighborhood social cohesion. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celińska-Janowicz, D. Zmiany struktury funkcjonalnej głównych ulic handlowych Warszawy (Changes of High Streets’ Functional Structures in Warsaw). In Miasta, Aglomeracje, Metropolie; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej: Lublin, Poland, 2014; pp. 461–482. [Google Scholar]

- Knap, R.; Staniszewska, A.; Zimolzak, P. The High Streets. Analysis, Strategy, Potential; Polish Council of Shopping Malls & PNB Paribas Real Estate: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, D.; Parker, C. Planning and Governance Issues in the Restructuring of the High Street. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mroczek, J.; Czarnecka, A. Warszawskie Ulice Handlowe (High Streets of Warsaw), Report by CBRE, 2018. Available online: https://biuroprasowe.cbre.pl/43221-warszawskie-ulice-handlowe (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Zombirt, J.J.; Wysoka, A.; Tomczyk, J.; Wdowiak, A. Measuring the Conditions and Potential of Retail High Streets in the Central Area of Warsaw and a Preliminary Development Concept for Selected Streets in Warsaw City Centre—Summary; JLL: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FY19. NYC Business Improvement District Trends Report; NYC Department of Small Business Services: New York, NY, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/sbs/downloads/pdf/neighborhoods/fy19-bid-trends-report.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Chudzińska, A.; Guranowska-Gruszecka, K. Urban Theories of the Emergence, Development and Endurance of Commercial Streets. Space Form 2020, 41, 101–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R.; Isakov, A.; Semansky, M. Small Business & the City. The Transformative Potential of Small-Scale Entrepreneurship; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 1989, 71, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, P. Partnership in Urban Regeneration in the UK. The Sheffield Central Area Study. Urban Stud. 1994, 8, 1303–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. Urban Governance and BIDs. The Washington DC BIDs. Int. J. Public Adm. 2006, 29, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symes, M.; Steel, M. The Privatisation of Public Space. The American Experience of Business Improvement Districts and their Relationship to Local Governance. Local Gov. Stud. 2005, 31, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, K. ‘Policies in Motion’, Urban Management and State Restructuring: The Trans-Local Expansion of Business Improvement Districts. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2006, 30, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamyko, Y. Governance Forms in Urban Public-Private Partnerships. Int. Public Manag. J. 2007, 10, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, A. Conceptualizing the Urban Commons. The Place of BIDs in City Governance. 2018. Available online: https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/fac_pubs/479/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Cook, I. Private Sector Involvement in Urban Governance. The Case of BIDs and TCM Partnerships in England. Geoforum 2009, 40, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Simon, O.; Nunley, J. Grow with Warsaw; Urban Land Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karpieszuk, W. Nowy ŚWIAT, Najdroższa Ulica w Polsce. To co tu Robią Kluby Go-Go i Pijalnie Wódki? (Nowy Świat Street, the Most Expensive Street in Poland). 2023. Available online: https://warszawa.wyborcza.pl/warszawa/7,54420,29303119,nowy-swiat-salon-czy-pijalnia-warszawy.html (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Jeziorska, A.A. Conditions for Functioning of Commercial Streets in Warsaw. Space Form 2020, 41, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojańczyk, F. Czas na Renesans Ulic Handlowych w Warszawie (Time for High Streets Renaissance). 2021. Available online: https://miastojestnasze.org/czas-na-renesans-ulic-handlowych-w-warszawie/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Shop In or Shop Out. Warsaw High Streets—What Opportunities Lie Ahead; JLL: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Available online: https://prch.org.pl/wp-content/themes/barba-gulp/dist/img/mediafiles/shop-in-or-shop-out-warsaw-high-streets-what-opportunities-lie-ahead-jll_366_oG7YaXh0.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Handel Miejski, Ulice Handlowe. Brakująca formuła w centrach miast. Poszukiwanie Wspólnej Wizji (Street Retail, Shopping Streets). Urbnews. 4 January 2016. Available online: https://urbnews.pl/wydarzenia/handel-miejski-ulice-handlowe-brakujaca-formula-w-centrach-miast-poszukiwanie-wspolnej-wizji/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Jędrzejczak, H.A.; Wróblewski, W. Galeria Handlowa to Ściema. Handel Powinien Powrócić na Ulice i Place (Shopping Malls is Scam). Newsweek. 22 June 2020. Available online: https://www.newsweek.pl/biznes/galeria-handlowa-to-sciema-handel-powinien-powrocic-na-ulice-i-place/z0429wl (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Migas-Mazur, R.; Kłopotowska, A.; Gościniak, P. Nowa Normalność. Krajobraz ulic Handlowych w Warszawie po Pandemii COVID-19 (New Normality. Warsaw High Streets after COVID-19); Cities AI: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, C.N. Urban Regimes and the Capacity to Govern: A Political Economy Approach. J. Urban Aff. 1993, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberger, K.; Stoker, G. The Evolution of Urban Regime Theory. Urban Aff. Rev. 2021, 3, 810–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.S. Urban Regime Theory: A Normative-Empirical Critique. J. Urban Aff. 2002, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.N. Power, Reform, and Urban Regime Analysis. City Community 2006, 5, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagan, I. Miasto. Nowa Kwestia i Nowa Polityka (City. New Question and New Politics); Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.M. Urban Regime Theory. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jałowiecki, B. Społeczne Wytwarzanie Przestrzeni (Social Production of Space); Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Popławska, J.Z. Rynki, Ulice, Galerie Handlowe. Polityka Publiczna Wobec Miejskich Przestrzeni Konsumpcji w Polsce (Marketplaces, Streets, and Malls); Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G.; Moonen, T. The Density Divident: Solutions for Growing and Shrinking Cities; Urban Land Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowy, K. Miasto Policentryczne (Polycentric City); Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Załęczna, M. Bariery wykorzystania PPP w Polsce w rozwoju przestrzeni miejskiej. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oeconomica 2010, 243. [Google Scholar]

- Wróbel, M. (Ed.) . Diagnoza do Programu Wykonawczego Poprawa Jakości Ważnych Przestrzeni Publicznych (Improvement Programme for Important Public Spaces: Diagnoses); Department of Architecture and Spatial Planning: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rochmińska, A. Centra handlowe jako przestrzenie hybrydowe (Shopping Malls as Hybrid Space). In Ludność, Mieszkalnictwo, Usługi (Population, Housing, Services); Klima, E., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2014; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Michnikowska, K.; Wojtowicz, W.; Dwojak, P. Ulice Handlowe w Warszawskich Osiedlach Mieszkaniowych (High Streets in Warsaw Residential Areas); Colliers International: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtczuk, M. Zamykają H&M na Nowym Świecie. “Klienci Wolą Galerie Handlowe” (H&M on Nowy Świat Street Is Closing Down. Customers Prefer Shopping Malls). 2017. Available online: https://warszawa.wyborcza.pl/warszawa/7,54420,22154431,zamykaja-h-amp-m-na-nowym-swiecie-klienci-wola-galerie-handlowe.html (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Koalicja na rzecz Rewitalizacji Placu Trzech Krzyży (Coalition for Trzech Krzyży Square Revitalization); Brochure by Trzech Krzyży Square Coalition: Warsaw, Poland, 2015.

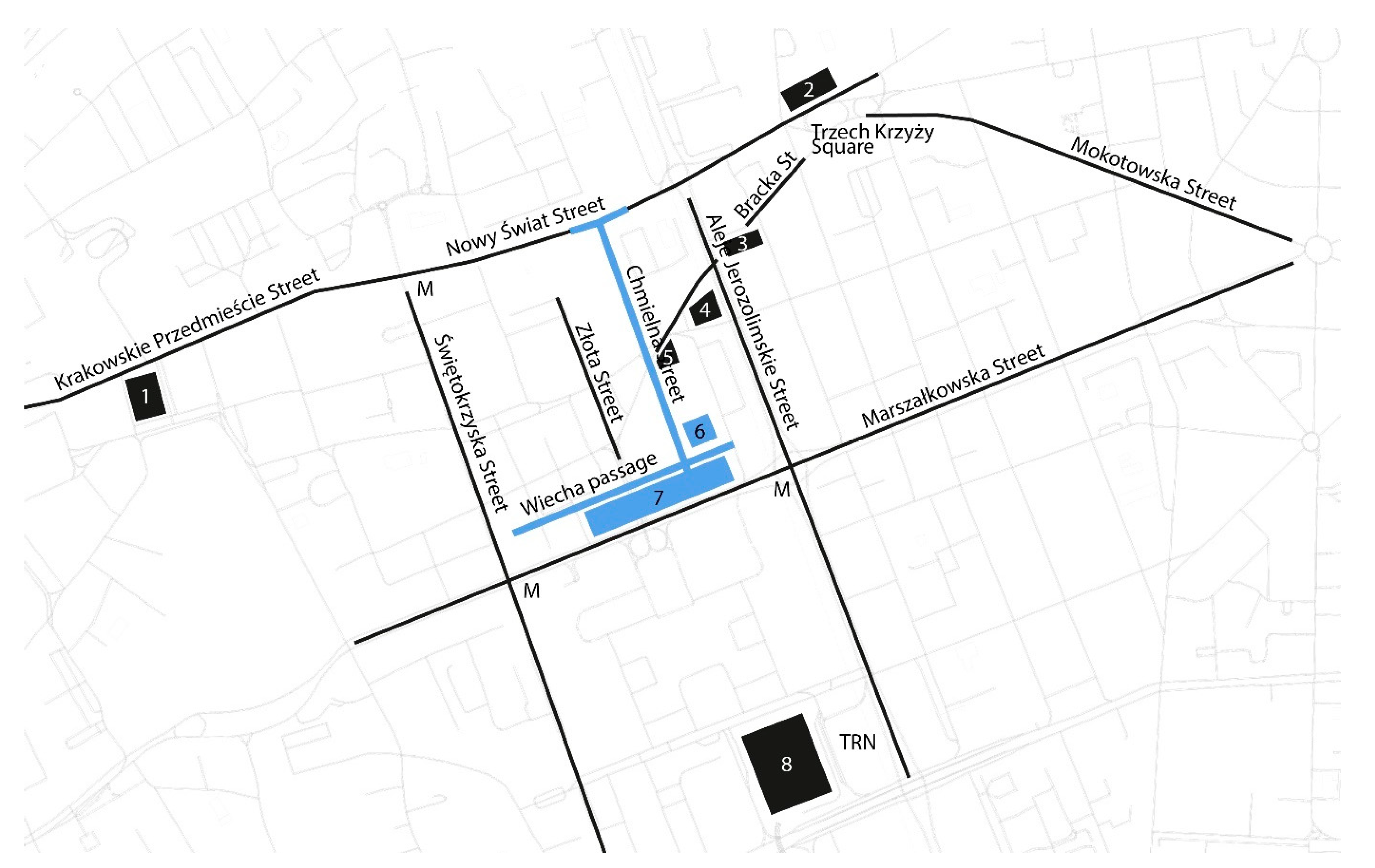

- Filip, A.J.; Kalnoj-Ziajkowska, E. Warsaw Downtown. Between Nowy Świat and Marszałkowska Streets. Historical Protection Guidelines; City Council Office: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grow with Warsaw—Retail Development Strategy. Workshop Presentation, Urban Land Institute Poland. 2017. Available online: https://architektura.um.warszawa.pl/documents/12025039/29091066/Grow+with+Warsaw+_Retail+Development+Strategy_www.pdf/6590089c-6d1e-8bbc-0316-209f0d85de82?t=1634497626169 (accessed on 18 January 2022). Workshop Presentation, Urban Land Institute Poland.

- Kosik-Kłopotowska, A. The Eastern Wall Surrounding Land-Use Plan Proposal; Department of Architecture and Spatial Planning, Capital City of Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Konrad, M. (Ed.) Uwarunkowania. Ocena obrazu Miasta; (The Conditions. City Image Evaluation); Department of Planning and Development Strategy, the Capital City of Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rewitalizacja—Wspólna Sprawa. Koncepcja Gospodarowania Lokalami Użytkowymi Należącymi do Zasobu m.st. Warszawy (Revitalization—A Common Issue. A Concept for Comunal Commercial Premises Management); Warsaw. 2018. Available online: https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/media/110112/3_koncepcja_handlowych_ulic_pragi.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Uchwała w sprawie zasad najmu lokali użytkowych (Leasing of Commercial Premises Resolution). Resolution # NR XXIII/663/2019 by The City of Warsaw Capital Council, adopted on 5 December 2019. Available online: https://bip.warszawa.pl/NR/rdonlyres/4AD06780-74AB-49A8-A1A5-4D6C8BF79073/1490185/663_uch.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Filip, A.J.; Nowakowski, W.; Sawicki, P. Alternatywne strategie zarządzania przestrzenią. Inspiracje dla Warszawy (Alternative Strategies for City Space Management. Inspirations for Warsaw). 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qLCL8Cn-kr4 (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Program Poprawy Jakości Ważnych Przestrzeni Publicznych na Lata 2022–2025; (Improvement Programme for Important Public Spaces for 2022–2025); Programme proposal, Capital City of Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

| Id (#) | Date | Sector | Male/Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 October 2022 | planning expert | F |

| 2 | 25 October 2022 | business consultant | M |

| 3 | 25 October 2022 | business consultant | F |

| 4 | 25 October 2022 | planning expert | M |

| 5 | 26 October 2022 | business consultant | M |

| 6 | 27 October 2022 | public authority leader | M |

| 7 | 1 November 2022 | business consultant | M |

| 8 | 7 November 2022 | business consultant | M |

| 9 | 10 November 2022 | planning expert | M |

| 10 | 16 November 2022 | business consultant | F |

| 11 | 16 November 2022 | public authority leader | M |

| 12 | 16 November 2022 | public authority leader | F |

| 13 | 23 November 2022 | public authority leader | F |

| 14 | 23 November 2022 | public authority leader | F |

| 15 | 6 December 2022 | planning expert | F |

| 16 | 8 December 2022 | business consultant | M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filip, A.J. “Power to” for High Street Sustainable Development: Emerging Efforts in Warsaw, Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041577

Filip AJ. “Power to” for High Street Sustainable Development: Emerging Efforts in Warsaw, Poland. Sustainability. 2024; 16(4):1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041577

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilip, Artur Jerzy. 2024. "“Power to” for High Street Sustainable Development: Emerging Efforts in Warsaw, Poland" Sustainability 16, no. 4: 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041577

APA StyleFilip, A. J. (2024). “Power to” for High Street Sustainable Development: Emerging Efforts in Warsaw, Poland. Sustainability, 16(4), 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041577