Freud [

16] employs the “breccia” analogy to delineate the elements of a dream, challenging the notion that a dream is a rationally ordered narrative with a coherently structured chain of images. This idea parallels the dynamic, complex, and contradictory essence of urban space, which cannot be explained through simplistic one-dimensional assessments and categorizations. Breccia is a rock formation characterized by the amalgamation of coarse sedimentary deposits from diverse sources, consolidated under intense heat and pressure generated by fault walls or volcanic activity. Freud [

16] suggests that a dream resembles a breccia in that it is composed of various fragmented elements held together by a binding effect, thereby indicating that the resultant designs within it are not inherent to the original constituents. In Freud’s [

16] view, the elements constituting a dream encompass diverse data, emotions, notions, perceptions, and visions. The dream coalesces into a unified entity from these distinctive elements, cohering through the binder known as the subconscious [

16] (p. 216). Therefore, the foremost features of the breccia analogy are as follows:

The concept of ‘breccia’ is evaluated within the relationship between cultural heritage and the built environment as a simile depicting adjacency [

17]. Bartolini’s [

17] concept of brecciation offers valuable insights into the assessment of urban heritage within temporal, spatial, and material contexts in modern life. The critical aspect of these insights lies in the different material accumulations pertaining to various temporal qualities. Therefore, this perspective brought by brecciation holds significant value in the interpretation of urban heritage practices [

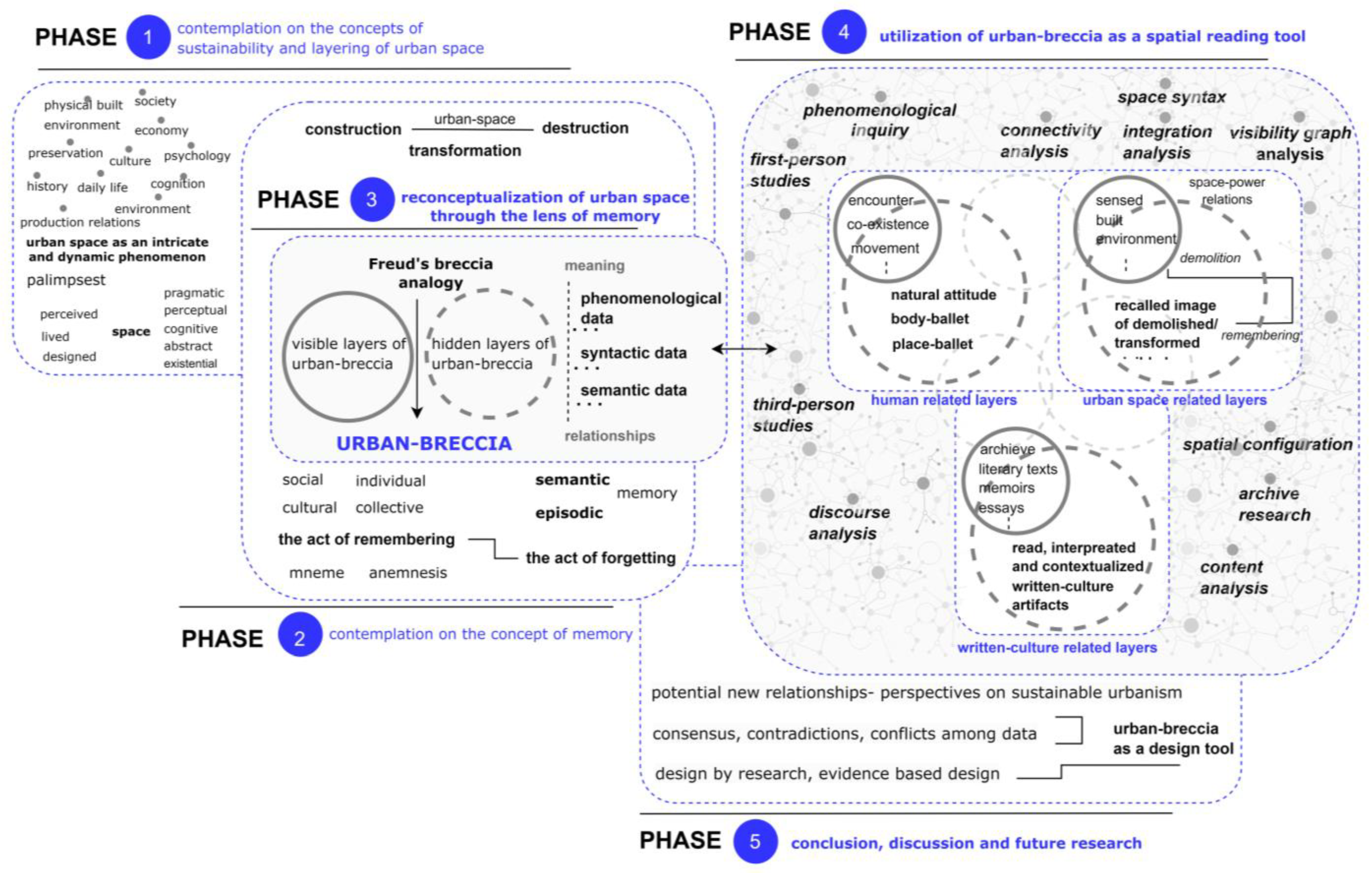

17]. However, when viewed from a more cognitive and phenomenological framework, the concept of breccia can be considered as a new analytical approach encompassing all layers of urban spaces, including their physical, semantic, syntactic, and phenomenological dimensions. This study endeavors to conceptualize urban spaces as an urban-breccia that brings together various qualities of memory. From a phenomenological point of view, urban space manifests all those attributes of breccia. Physically constructed, destroyed, reconstructed, transformed, phenomenologically felt, perceived, remembered and forgotten, urban space exhibits an urban-breccia quality by structuring intricate and multidimensional relational systems in which visible and hidden layers coexist. Therefore, the characteristics that define the breccia analogy can be transferred to the urban space through the concept of ‘urban-breccia’:

Urban-breccia provides critical potentials by defining certain problems related to the evaluation of these perspectives together, as well as by revealing the necessary conceptual representation and framework for their analysis. As it has a complex, dynamic, and intricate structure, urban-breccia cannot be comprehended through one-dimensional traditional representational procedures that are reliant on strictly defined classifications and entities with clear beginnings and endings within the linear historical understanding. To analyze urban-breccia, it is necessary to consider its multidimensional dynamic structure, complexity, and contradictions through a comprehensive spatial understanding. In this context, within this study, knowledge acquisition transpires via spatial analysis, aiming to unravel the relationships between the visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia, departing from a strictly chronological approach. In this spatial reading, memory traces are explored through the lenses of ‘human, urban space, and written culture’ to unveil the relationships between these layers. It endeavors to decipher the hidden layers of urban-breccia through the visible layers by investigating the remembered content along with the styles of remembering. It also seeks to analyze the multilayered situations of urban-breccia within the dynamic, discontinuous, vague, ambiguous, reconciling, and conflicting relationships associated with the perspectives of human, urban space and written culture.

2.1. Urban-Breccia and Humans

Urban-breccia situates memory and human beings at the center of knowledge theory. Because, within the phenomenological framework, the process of acquiring knowledge inherently involves the direct recall of memory contents, it is specifically termed ‘remembering’. Urban-breccia is interpreted by the individual memories through relational networks where both internal and external factors are influential. This spontaneous process of interpretation is not merely a one-dimensional formation of mental imagery derived solely from sensations. This imagery process involves the continuous reconstruction of the past images acquired through senses and experiences in the memory in the present time. This constantly recurring process contains various acts of remembering that involve specific processes and relationships. Greek philosophers distinguish between various acts of remembering using two distinct terms based on their qualities. The act of remembering that involves a sudden emergence of an image in the mind, resembling a sensation (pathos), is referred to as “mneme”. On the other hand, the active effort of consciously remembering specific information is denoted as “anamnesis” [

18] (p. 4).

The hidden layers of urban-breccia come into existence through remembering. The act of remembering, regardless of its content, is a mental activity related to the existence of a self that remembers. In this case, remembering is an individual action. On the other hand, while remembering is an individual cognitive function, in terms of the content being remembered, it inevitably becomes a social action. An individual cannot develop a memory independent of the social relationships they experience. The content being remembered is formed through the interactions with other individuals in the individual’s everyday life. Therefore, remembering is also a social action. The distinctive way of living and thinking and all the kinds of human products that make societies different from other societies constitute the content of remembering. Hence, remembering is also a cultural action.

Urban-breccia conceptualized in this study positions memory at the center of the theory of knowledge and points to the processes of remembering that produce networks of both semantic and syntactic relationships. The multidimensional structure of imaginative processes can be elucidated by employing Freud’s tablet metaphor, which comprises three layers representing perception and memory activities. According to Freud’s metaphor, memory consists of a wax surface at the bottom, a layer of waxed paper on top of it, and a non-erasable, hard, and durable material layer at the top. The traces of the writings on the top layer leave imprints on the middle layer, the waxed paper, and the underlying wax surface at the bottom. Even if the writings are erased on the top layer, the traces of the old writings still exist on the bottom layers. Freud likens the transfer of perceptions to memory and their preservation therein to traces resembling imprints on a wax surface, which remain permanent and can only be seen under the correct illumination [

19] (p. 228). This narrative also originates the methodological foundation of the study. Similarly, in urban-breccia, there are also traces that reveal the relationships between visible and hidden layers. The urban-breccia, as a structure where different phenomena continuously generate visible and hidden layers through ongoing change, constantly produces new traces within the framework of space–time relationships. These traces have the potential to decipher the relationships between the visible and hidden layers sought after in the perspectives related to human experience, urban space, and written culture within the framework of urban-breccia.

The visible layers of urban-breccia concerning human interactions originate from the everyday actions and experiences of individuals with their physical, spatial, and social environments. Within the framework of these everyday actions and experiences, observable human behaviors and interpersonal interactions constitute the visible layers of urban-breccia as practices of movement, encounter, and coming together. Movement, as a phenomenon that enables the phenomenological experience of space, can be considered the foundation of these visible layers. In pioneering phenomenological studies, movement and the resulting encounters are also identified as the essence of human experience [

20] (p. 33). As individuals constantly reconfigure their relationships with objects and people in their surroundings through movement, urban-breccia is also constantly reconstructed. The movement constantly changes the time–spatial relations of urban-breccia by ensuring that the individuals constantly re-establish their relationship with all the external variables. In this context, it points to conceptual–physical, abstract–concrete, qualitative–quantitative, and experiential–analytical intersections. Individuals moving within urban space inevitably create interpersonal interaction planes and come together. Along with movement, another observable layer of urban-breccia is co-existence. As social beings, humans come together in various contexts, such as family, work, commerce, and friendship, in their daily lives, while in the process of movement. Even if not for specific purposes, individuals moving within urban spaces inevitably experience numerous urban encounters.

While practices of movement and co-existence form the visible layers of urban-breccia in relation to the human presence, the routines of time–space and the behavioral patterns constructed by these visible layers constitute the hidden layers.

Figure 3 displays the conceptual framework which depicts the relationships between the human-related visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia formed within the focus of the act of remembering.

The first of these hidden layers, called “natural attitude”, consists of the patterns in which the individuals routinely continue their daily life without having to be a conscious subject all the time [

21] (p. 149). In this scenario, individuals continue their daily activities without questioning or consciously realizing it, within a situation defined as learned and habitual. These practices are spontaneously recalled as mneme and repeated in an unconscious manner to generate recurring patterns. They include the qualities of being present in specific places within specific time intervals and encompass all environmental scales, from driving in urban spaces to walking.

Another set of the hidden layers of urban-breccia points to time–space routines that generate strong-structured memory patterns in daily life. Seamon eloquently articulates these routines under the concept of “body-ballet”. Body-ballet refers to the spatial behaviors of individuals that enable the continuity of learned movements from the past into the future. It represents temporal–spatial routines, a series of habitual bodily behaviors that extend into significant parts of daily life [

21] (p. 157). These are strong behavioral patterns that individuals consciously repeat with specific motivations amidst their daily, weekly, and monthly routines. These habitual and learned movements are carried out in a continuous flow. A culturally and socially sustainable physical environment can create a spatial dynamic in which an individual’s time–space routines and body-ballet coalesce into a harmonious entity, forming what Seamon calls “place-ballet”.

Place-ballet refers to the unity of space and action, where individuals’ various time–space routines and body-ballet intersect within the same location. [

21] (p. 159). Therefore, it signifies the variable relationship between human actions and space through long- or short-term memory. The experience duration and frequency of space influence the acts of remembrance. The moving body rituals, gatherings, boundaries, dominant axes, hierarchies, perceived as abstract patterns in the built environment of living spaces, can be seen as conceptual forms shaped by episodic and semantic memory in urban space. Frequently used spaces, routes, and establishments, where gatherings and encounters occur intensively, can be regarded as instances of place-ballet within urban articulation.

Hidden layers defined as natural attitude and body-ballet are stored in memory as sensations, experiences, impressions, and insights during everyday life. The information obtained through our senses in daily life is transferred to short-term memory. Short-term memory is where information is temporarily stored before being transferred to long-term memory; it has a limited capacity to store all the information at once [

22]. Information that fails to establish strong connections cannot be transferred to long-term memory and gradually weakens, leading to forgetting. Experiences that become a natural attitude or body-ballet in the routines of everyday life are stored in long-term memory. Long-term memory is constantly reconstructed with each new information that a person has acquired, learned, and experienced throughout her life. The patterns and relationships in the information are constantly reconfigured. Among these, sequences of information containing specific events and experiences occurring at any point in the life process are stored in episodic memory. The data in episodic memory are memories of autobiographical events that are explicitly expressed and encoded with contextual information, such as time, place, and associated experiences [

23]. Individuals perceive themselves as actors in these events, and while storing subjective, autobiographical, and personal memory data, they also become part of the collective memory that encompasses all the contextual, social, cultural, and political processes surrounding an event. In this regard, memory data can be acquired through conscious recollection of memories through anamnesis, as well as spontaneous recollection as mneme in response to any stimulus during everyday life. Memory data, in which information about the external world is conceptually and semantically structured, are stored in semantic memory [

23]. As individuals sustain their lives socially within everyday experience, the personal experiences and knowledge they construct with semantic memory are recorded not according to a spatial and temporal framework, but within a semantic and factual framework. Semantic memory is relational and associated with the meanings of concrete, abstract, and verbal symbols. The contents of semantic memory possess a quality of spontaneous recall, evoking associations when suddenly remembered as mneme.

The elucidation of the underlying data behind the concepts of urban-breccia’s hidden layers relies on the deciphering of the semantic and episodic memories of individuals through phenomenological inquiry. As an example of such studies, the research conducted on the Mecidiyeköy Liquor Factory and its surrounding area in Istanbul can be examined [

13]. In this study, data related to layers of movement, co-existence, encounters, body-ballet, natural attitude, and place-ballet were obtained through first-person studies involving on-site observations and experiences, as well as structured interviews within the framework of third-person studies. In these interviews, open-ended questions were directed towards obtaining unbiased patterns of experience from individuals’ semantic and episodic memories. These phenomenological studies are supplemented with sketching and cognitive mapping techniques. Schematic illustrations of previous spatial configurations experienced and remembered by urban dwellers are evaluated in conjunction with behavioral patterns [

13]. During this process, data sources are not solely selected based on the ‘present time’. Thus, archival research extends its scope to include photographs and video sources, aiming to decode the hidden layers of urban-breccia associated with the daily life, and to reveal the interplay between visible and hidden layers from the past. Finally, by integrating the data, attempts are made to identify patterns emerging in space as a result of the users’ experiences, actions, and behaviors and to correlate these pieces of information. The acquired phenomenological data are compared with the data obtained from simultaneous syntactic and hermeneutic studies conducted on the layers of urban space and written culture within urban-breccia. The causality behind the emerging patterns is investigated within the framework of memory attributes to determine the relationships. Thus, urban-breccia, as a complex network of relationships, can generate memory knowledge concerning space through an evaluation characterized by the distinct features of phenomenological, syntactic, and semantic perspectives, engaging in contradictions, conflicts, and reconciliations among their respective interrogative attributes.

2.2. Urban-Breccia and Urban Space

In the second section of the conceptual framework of the study, traces are sought that encompass the visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia regarding the urban space itself. Within this framework, by adopting a phenomenological perspective, the urban space is approached through Lefebvre’s triad projection and Schulz’s five different spatial descriptions, creating planes where urban-breccia can be discussed.

Lefebvre proposes three layers regarding the urban space that are experienced and interpreted as images. The first of these is the ‘spaces of representation’, the lived space, which consists of complex symbolisms encoded by urban dwellers through meanings, symbols, and signs. The second is the ‘representation of space’, the imagined and designed urban space, which represents conceptualizations of space. Finally, the perceived space refers to the ‘spatial practices’ in which the ongoing everyday life routines are perceived under the influence of social, public, local, and economic forces. These layers are often in dialectical relationships with each other [

24] (p. 38). In this study, these layers describe the different characteristics of urban-breccia’s diverse layers. The representation of space and spatial practices emphasize the spontaneous articulation of the city in maintaining visible layers such as daily temporal–spatial routines, natural attitude, and place-ballet. While lived and perceived spaces highlight urban-breccia’s spontaneous articulation of the city to maintain hidden layers of daily life, spatial representations and designed space tend to transform these layers intentionally by erasing existing layers and establishing conflicting relationships.

Similarly, Schulz [

25] conceptualizes space based on the processes of perception, cognition, and semantic evaluation and provides five different descriptions of space. Schulz’s classification is, in a sense, a categorization based on the symbolic, semantic, and imaginative content of space: ‘Pragmatic space’ is confined to the physical dimension and material elements. The space that individuals subjectively create in their minds, consisting of sensory, symbolic, and impressionistic elements in their memories, is referred to as ‘perceptual space’. ‘Cognitive space’ allows individuals to think about other dimensions of space through mental schemas. ‘Abstract space’ creates a platform where the logical relations of space at the conceptual level can be discussed. Finally, ‘existential space’ comprehensively explains the qualities that make the individual part of a cultural and social entity [

25] (p. 11). Urban-breccia encompasses hidden and visible layers that contain all these space definitions. Memory is intertwined with syntactic and semantic relationships in all those spatial gradations, which range from pragmatic space that signifies the physical qualities and materiality to existential space that emphasizes indicators, symbolic codes, and dimensions, such as political, social, cultural, economic, and semantic dimensions. Defined as pragmatic, perceptual, cognitive, abstract, and existential space, this quintet of spaces creates visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia with different qualities according to the memory and space relations established in the lived and perceived space. Urban-breccia, constantly reconfigured through the act of remembering, unveils these relationships that are established among the specific intersections of these spaces.

As

Figure 4 demonstrates, any physical urban space data of pragmatic space that can be directly presented through any form of representation constitute the visible layers of urban-breccia associated with the city. The physically existing built environment, public spaces, and buildings and their immediate surroundings, spatial structures, and commercial spaces, as well as any urban equipment, such as urban furniture, signs, commercial signage, advertising boards, and traffic regulators, form the visible layers of urban-breccia. These layers refer to the physical and observable qualities of urban breccia. They can be physically experienced and perceived by the senses.

The hidden layers of urban-breccia relevant to urban space are elucidated through the mechanisms of remembering–forgetting and destruction–construction and their dialectical interplay, as depicted in

Figure 3. Urban space has been in a continuous process of change and reconstruction due to qualitative and quantitative dynamics, such as physical environment, social life, culture, politics, social structure, and economy. The rapid succession of local and global events, changing urban actors, power dynamics, and production relations can be explained through the tension between destruction and construction, as manifested in the visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia. Under normal circumstances, the act of destruction implies forgetting, while the act of construction evokes associations of remembrance. In the context of urban-breccia layers, that judgement loses its conventional meaning. Demolition and construction can actually be evaluated as two equally valid characteristics of immortality [

26] (p. 11). For any reason, a consciously demolished monument can be as evocative within the meaning relations of everyday life as its existence. In a parallel scenario, spaces, commodities, or structures that have embedded themselves within urban memory at any point in the city’s history naturally retain their position within the urban-breccia as ‘hidden layers’, enduring even if demolished or destroyed (

Figure 4). Moreover, the transformed urban space is interpreted not solely through its updated image but also through the amalgamation of diverse acts of remembrance, including its initial experiences and images. These visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia, associated with urban articulation, constantly transform due to the multidimensional dynamics of urban space.

Political, productive, and economic powers, ideological courses of the era, and changing cultural and social dynamics also create the hidden layers of urban-breccia. The relationships of consistency and conflicts between the visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia can be largely explained by these physical, social, cultural, and political attributes of urban articulation. As power forces and ideologies articulate urban space to establish their own spatial practices, the concepts of globalization reshape space as a commodified entity, continuously reconstructing it as a source of surplus value. This articulation may become so constant that it reaches a point where no traces of memory can be detected in space, making remembering nearly impossible. In this case, the act of remembering takes place within the concept of urban-breccia only in the dimensions of the perceptual, cognitive, abstract, and existential space of written culture layers. Therefore, the visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia establish tension-filled relationships with the visible and hidden layers of human, urban space and written culture, involving consistencies, contradictions, interruptions, and gaps. Traces of these relationships can also be found in collective reactions and protests during social events, which respond to all these spatial and power relations. These social events serve as indicators of the conflictual relationships between the power dynamics that compel space-altering actions and the natural attitudes and body-ballets of individuals in everyday life. All these cultural and social networks of meaning, indicated by the visible and hidden layers, manifest themselves as architecture and the built environment, becoming observable. Similarly, the meaning of the built environment is also deciphered through social and cultural dynamics. This duality emphasizes the interconnected visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia, characterized by intricate, complex, ambiguous, dynamic, negotiated, and contradictory networks of meaning formed by urban articulation, social and interpersonal relations, and cognitive dynamics.

The visible layers of urban-breccia encompass the perceptible qualities of urban space, which are perceived by individuals’ sensory memory and transferred to short-term memory. Through experiential connections, the information that is transferred to long-term memory is reconstructed in semantic and episodic memory within the relational dynamics among the layers of urban-breccia. During this process, the stored information in memory

indicates a semantic network of relationships related to the existence of visible layers or

refers to a semantic or episodic narrative sequence concerning the hidden layers behind these visible layers.

The hidden layers that emerge through the disappearance/destruction of the visible layers become the objects of a memory devoid of experience. These layers are recalled from memory both as a sudden image that emerges in the mind during the urban space experience, referred to as mneme, and as an active effort of conscious recollection, referred to as anamnesis.

The spatial syntax method establishes valuable synergies in conjunction with phenomenological studies, exploring the relationships of the visible and hidden spatial layers of urban-breccia. The continually reshaped urban-breccia through memory due to the changing articulation of space cannot be exclusively sought through semantic methods. At this point, the spatial syntax scrutinizing physical space, providing insights into social, cultural, and mental perspectives, enables significant collaborations among the research methods in the interpretation of urban-breccia. As spatial systems are socially constructed, they encapsulate the collective memories of societies. The memory data related to human beings are conveyed through the space itself and the organization of space, which is termed as its relational property and referred to as “configuration” [

9]. The spatial configuration encompasses the socio-cultural structure and knowledge. Every spatial configuration transformed by destruction–construction processes carries a memory trace that defines a collective way of remembering.

The level of the integration of the configuration determined through spatial syntax analysis is a concept that provides significant data from a phenomenological perspective. Integration is the average depth of the other parts within the configuration of space [

11]. Spaces with high integration values possess high visuality and permeability. These spaces generally indicate areas where social and cultural interactions, movement, and co-existence are at a high level, demonstrating the potential to uncover the hidden layers of urban-breccia within an existential spatial framework. The inference can be made that integrated spaces are easily imaginable and memorable, while also bearing intense collective memory traces.

Another spatial syntax tool, visibility graph analysis, has the potential to generate phenomenological predictions regarding how hidden layers are perceived and experienced by individuals when in motion. The visibility graph analysis indicates the “convex isovists” defining a person’s panoptic view from a specific point in an urban space [

11]. The visibility graph analysis reveals the perception and image-forming levels of convex areas; hence, the most visible part of the space is expected to be the most easily remembered area in users’ memories. All these preconceptions obtained through spatial syntax tools are highly objective, robustly empirical, explanatory, and testable data regarding the built environment. Rather than generating information on their own, these data create thinking planes that can be verified or refuted with regard to the relationships between individuals’ memory, space, and meaning. Urban-breccia, constructed as a complex network of relationships, has the potential to generate new spatial knowledge through the assessment within the distinctive characteristics of syntactic, phenomenological, and hermeneutic perspectives and to consider their inherent contradictions, conflicts, and consistencies, which interrogate each other.

2.3. Urban-Breccia and Written Culture

The traces of the hidden layers of urban-breccia can be sought in the written cultural artifacts that intersect with the individual and collective realms of culture, alongside human and urban space. Written culture has the potential to explain the areas that both individual and collective memory fail to explain [

27]. Individuals generate individual networks of meaning from the human, urban, and written cultural layers of urban-breccia. This mental construct is formed through remembrances in various dimensions: the social dimension, where individuals engage in interpersonal interactions within collective experiences; the experiential dimension, where they perceive and experience spatial interactions; and the dimension of cultural products, where they encounter the written culture related to these spaces. This multidimensional structure of memory and recollection can be easily understood through the following quotation by Halbwachs [

28]: “Imagine walking on the streets of London. If you are accompanied by an architect, your attention will be directed towards the structure of the buildings, their proportions, and facades. A historian might discuss the historical significance of the street, while a painter describes the colors of the parks and the play of light and shadow over the Thames River. A merchant may show you the commercial spaces and bustling marketplaces. Even if no one accompanies you, all the texts you have read about this city before coming here, narrating it from various perspectives, will accompany you. As you pass Westminster or cross a bridge, you remember what the historian told you or the expression depicted from the artist’s perspective. Around St. Paul’s, Strand Boulevard leaves an impression of the Dickens novel you read in your childhood, and in fact, you are walking with Dickens at that moment [

28] (p. 23)”.

Written cultural products can be considered as texts that record not only individual memories within the framework of spatial memory but also the processes related to the social, cultural, political, and economic dimensions of a place. Accordingly, searching for the traces enabling remembrance within the human and urban layers of urban-breccia and exploring the traces facilitating remembrance in the texts where the memory of a specific place is externalized offer complementary pieces of information. Thus, by also starting from subjective perspectives in the study, it becomes possible to reveal the semantic relationships established by a collective memory. The traces of memory can be found in:

Memoirs, travelogues, personal diaries, and letters that depict the natural attitudes, body movements, and spatial patterns associated with a place that was abandoned for specific reasons in the past;

Essays, news articles, and oral history studies that narrate social/historical events that took place in a specific location in the past;

Literary texts that describe a particular place at a specific time, encompassing its physical, social, cultural, and economic dimensions.

These written texts contain both individual and collective memory traces as sources that form the visible and hidden layers of the urban-breccia. Accordingly,

Figure 5 reveals the relationship between the visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia concerning written culture.

Writing is the act of transferring memory onto paper and creating a memory outside the human mind. These externalized products are the visible layers of written culture within the urban-breccia. At this point, the linguistic narrative that is transformed into writing gains an autonomy that is independent of the writer.

In a similar manner to the way that individuals ‘read’ the urban space and interpret it as images, readers also unveil hidden layers by interpreting and deciphering the text. Therefore, the visible and hidden layers of written culture within the urban-breccia are situated within the linguistic and cultural intersection of understanding and interpreting actions. Language provides humans with the capacity to comprehend and reach meaning as a condition of cultural memory. The linguistic traces in written cultural products cannot be separated from our ways of interpreting the world and modes of remembrance. In this regard, the traces of written cultural products in relation to memory are embedded in hidden layers through linguistic codes and are revealed through the act of interpretation. The visible and hidden layers of written culture within the urban-breccia are stored in long-term memory in both semantic and episodic forms, each containing different types of information, after establishing relational networks in short-term memory. At this point, it is impossible to separate language from thinking, meaning, and memory; thus, remembering becomes a linguistic action. During this process, remembering occurs both as a passive form of recalling a sudden image in the mind, referred to as mneme, and as a conscious effort to actively recall specific information, referred to as anamnesis. The product created by the writer is a “memory” in terms of its content. At this point, remembering means having an image of the past. The collective dimension of language as a social and cultural concept converges with this imaginative content in an individual’s memory within written cultural products. From the reader’s perspective, the text acquires an imaginative dynamism that points to different semantic relationships containing other planes of remembrance. The narrative-turned-image affects the reader’s semantic memory, creating abstract semantic relationships, while also constructing a framework of episodic memories, with the reader positioned as the subject.

The visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia, delineated in the conceptual framework within the domain of written culture, are associated with individual/collective and semantic/episodic memories through the medium of ‘discourse’. Thus, employing the method of ‘discourse analysis’, it becomes possible to unveil the semantic relationalities established within a constructed/evolving collective memory, rooted in subjective perspectives.

Discourse can be defined as a collective of shared meanings and expressions related to any subject, object, or concept. Discourse is ‘constructed’ through the structurization achieved by the repetition over time of linguistic tools used by individuals either unquestioningly or consciously. Language perpetually and continuously generates the social world. Individuals not only construct memory relations based on their perceived spaces through language but also co-construct them in conjunction with language. Hence, the construction processes of discourses exhibit an inseparable cycle from collective memory. In other words, collective memory manifests itself through discourse as semantic and episodic structures. In a deconstructive logic, discourse analysis dismantles these structures in pursuit of meaning. At this point, textual materials, such as newspaper articles, magazine pieces, literary works, oral history studies, personal diaries, letters, memoirs, and travelogues, along with any encountered visual elements in the daily urban space—be it a poster, banner, signage, or advertising board—can be considered as data contributing to the formation of urban discourses.

In discourse analysis, answers to questions such as ‘who is the speaker?’ (the enunciator), ‘who is being addressed?’ (the addressee), ‘what constitutes the background information?’ and ‘what is the intent?’ hold significant importance. Discourse analysis conducts an ‘excavation’ of spontaneously or consciously constructed expressive structures about the visible and hidden layers of urban-breccia within social, political, cultural, and economic contexts. It endeavors to dissect hierarchical power relations among these constructs and to elucidate the resultant meaning relationships embedded within. It endeavors to excavate the traces pertaining to the memory within written cultural artifacts, buried within hidden layers through linguistic codes, and strives to decipher the underlying meaning through a critical approach.