Abstract

The survival and sustainable development of new technology-based ventures (NTBVs) have become challenging due to the unpredictable and dynamic technological environment as well as the scarcity of their own resources. Considering the tension between “conformity” and “distinctiveness” faced in NTBVs’ growth, based on the optimal distinctiveness perspective, we develop a configurational framework to investigate how combinations of multiple factors (i.e., political guanxi, business guanxi, exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, environmental dynamism, and environmental munificence) lead to high enterprise growth. This study analyzes survey data of 30 Chinese NTBVs by conducting a necessary condition analysis (NCA) to inspect the necessary relationships between each condition and the outcome and employs fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to determine the configurations to achieve growth. It is shown that individual elements do not compose the necessary conditions for yielding high enterprise growth, and high levels of new venture growth require different configurations of antecedents to be achieved. Furthermore, four types of driving pathways are identified for the NTBVs’ growth, each of which contains different compositions of enterprise strategy and external environment. These findings enhance the literature on enterprise growth and its influencing factors and provide implications for NTBVs to achieve high-quality growth and development.

1. Introduction

New technology-based ventures (NTBVs) have relatively higher knowledge or technology requirements for entrepreneurs or entrepreneurial teams. They usually exhibit significant time and resource consumption in the process of technology development, product trial, prototype commercialization, and docking to market demand, resulting in greater uncertainty and risk for NTBVs than for general new ventures [1]. Furthermore, in China’s current economic structural transformation, NTBVs are encountering imperfect industry ecosystems, unsound market rules, and difficulties in accessing resources. These challenges pose a significant threat to their survival and growth. The data from the “China Innovation and Entrepreneurship Report”, released by Tencent Research Institute, indicate that current Chinese ventures possess an average life expectancy of fewer than four years. Moreover, new businesses such as smart hardware and O2O (online to offline) are the ones with high mortality rates (http://www.100ec.cn/detail--6415107.html, accessed on 12 September 2017). Therefore, in the unpredictable and dynamic external environment, nurturing the NTBVs’ growth, improving their overall survival rate, and promoting their sustainable development have become critical concerns for the industry and academia.

Based on different theoretical perspectives, prior research has demonstrated the significance of the strategies adopted by enterprises in their acquisition of legitimacy vs. competitive position, which ultimately affects their growth. Specifically, the institutional theory emphasizes the vital effect of institutional isomorphism on enterprise growth, arguing that they need to comply with social norms and values established within the society in which enterprises operate to establish legitimacy and gain resource availability [2]. In other words, research on enterprise growth from an institutional perspective advocates that enterprises conform to prevailing government policies and market norms [3]. In this vein, connecting with key stakeholders based on embeddedness strengthens the strategic conformity of enterprises with rules and norms [4]. Hence, in China’s current phase of both execution control and market regulation, it is easier for NTBVs to gain legitimacy and more favorable resources by implementing a “guanxi strategy” with “Chinese characteristics” to build relationships with political and business entities [5], which enable NTBVs to overcome the liability of newness [1]. However, competitive strategic theory explains the necessity of choosing a distinctive strategic positioning and emphasizes that the pursuit of distinctiveness contributes to the cultivation of endogenous growth ability and central competitive advantage [6]. Research conducted from this theoretical perspective emphasizes the significance of distinctiveness on enterprise growth. This study concludes that the variations in the performance of enterprises are mostly due to their ability to adopt innovative values that are distinct from those of their competitors [7]. Therefore, NTBVs can carry out an “innovation strategy” to break the existing technological tracks and develop new windows of opportunity through innovative activities, such as R&D and new product development.

Although studies offer valuable insights into tackling the practical challenge of sustaining NTBVs, significant issues remain that demand attention. First, research mainly focuses on the “net effect” of guanxi or innovation strategies on enterprise growth from a single theoretical perspective [8,9], ignoring the possibility of complementary between different enterprise strategies [10]. The singular perspective exhibits a certain level of inadequacy in explaining the concurrent adoption of both “distinctiveness” and “conformity” in a specific enterprise. We resolve this theoretical gap by introducing the optimal distinctiveness perspective, which outlines how enterprises shape distinctiveness amid intense pressure to adhere to norms, providing opportunities for enterprises to leverage a combination of guanxi and innovation strategies [11,12]. Consequently, explaining how NTBVs can choose between conformity and distinctiveness to achieve high growth through the optimal distinctiveness perspective is significant. Second, although an enterprise’s scale and potential growth over a certain period are inextricably linked to its strategy, the “contingency factor” [6] brought about by the external environment cannot be neglected. Contingency theory states that effective enterprise growth is achieved when the enterprise’s strategies fit the conditions of its environment [13]. Nevertheless, existing studies on new venture growth ignore the contextual characteristics that affect the effectiveness of the strategy and rarely consider the impact of matching the strategies adopted by the enterprise with factors in the external environment on growth, resulting in a lack of consensus on the empirical results of NTBVs’ growth research.

Given the stated theoretical importance, this study attempts to match and synergize multiple elements, such as enterprise strategy and external environment, from a configuration perspective to better understand the strategic tradeoffs of NTBVs and the complexity of the external environment. Specifically, it aims to answer the following questions:

- Whether and to what extent are the elements of guanxi strategy, innovation strategy, and external environment necessary conditions influencing the high growth of NTBVs?

- Which combinations of antecedent conditions are more efficient for NTBVs’ growth?

To examine the impact of the intricate interplay between enterprise strategy and the external environment on NTBVs’ growth, we employed a combination of the necessary condition analysis (NCA) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) methods to scrutinize both the causal relationships of necessity and sufficiency [14].

The possible contributions are as follows: First, we integrated the guanxi and innovation strategies of new ventures through the optimal distinctiveness perspective to explain the growth mechanism of NTBVs. Second, considering that the optimal distinctiveness positioning is not the only fixed static equilibrium point, multiple equilibrium combinations may exist in different contexts [11]. Therefore, this paper introduced external contextual conditions to explore the sophisticated influence of the adaptation of enterprise strategy and different contextual factors on NTBVs’ growth, which carries great theoretical and practical importance in revealing the multiple pathways and mechanisms of NTBVs’ growth in the entrepreneurial context of China. Finally, this study used a mixing method that contributed to integrating the strengths of QCA in analyzing the complex mechanisms driving the NTBVs’ growth and the advantages of NCA in exploring the necessity of individual antecedent conditions.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Optimal Distinctiveness Perspective

Faced with the demand for conformity resulting from institutional pressures and the demand for innovation and distinctiveness brought about by competition, “to be the same or to be different” has already turned out to be an essential strategic decision for enterprises in the process of growth [11,15]. On the one hand, institutional theory posits that enterprises ought to endeavor to conform to established conventions, anticipations, and customs to gain legitimacy and alleviate the adverse effects on their performance that stem from nonconformity to public expectations [3,16]. On the other hand, research on competitive strategy suggests that enterprises should pursue distinctiveness strategies to seek unique market positioning and leverage core resources to gain a competitive edge [6,17]. However, pursuing only conformity or distinctiveness may affect or even undermine the enterprise’s growth. The search for distinctiveness may compromise legitimacy and inhibit enterprises from obtaining the resources they require; the search for conformity may lead to more competitive pressures, which also threaten the enterprise’s growth [12,15]. In this way, “keeping conformity” and “seeking distinctiveness” coexist in a single enterprise and are both interdependent and contradictory [18]. An enterprise can effectively distinguish itself from its competitors by appropriately managing the tension between conformity and distinctiveness while ensuring that it is accepted as legitimate and thus achieves optimal performance.

In response to the discussion of “to be the same or to be different”, reference [15] proposed the concept of strategic balance grounded in strategic management and incorporated “conformity” and “distinctiveness” into a unified framework at the firm level. It captured the relative strength of conformity and distinctiveness in enterprise strategy using the construct of “strategic similarity”, which argued that a moderate degree of strategic similarity could enable enterprises to better balance conformity and distinctiveness pressures to achieve optimal performance [19]. As the research continued, the opposed view of the U-shape emerged further. The U-shaped view suggests that enterprises should pursue a high degree of conformity or differentiation and seek to grow under high legitimacy or minimal competitive pressure [20]. In other words, adopting strategic similarity may cause the worst performance [21]. Additionally, reference [12] proposed to reconcile the conflicting requirements of conformity and distinctiveness through two primary mechanisms, i.e., integrative orchestration and compensatory orchestration. The former emphasizes using unique enterprise features to meet conformity or distinctiveness requirements, and by combining different features, conflicting needs can be resolved. The latter indicates that the distinctiveness of an enterprise’s feature may lead to a deviation from conformity, which can be balanced by the conformity of other features, ultimately achieving an ideal level of distinctiveness at the firm level, known as “optimal distinctiveness” [22]. What is more, adhering to the basic assumptions of the strategic balance view, the orchestration perspective further stresses that context is an influential factor leading to different views of optimal distinctiveness [23,24], such as the different stakeholders, unique trajectories of an industry’s evolution and enterprise’s life stages. These impact optimal distinctiveness [12], breaking through the limitations of recent research that overlooks the complexity and contextualized characteristics of business practices.

The tension between institutional conformity and strategic distinctiveness has been obvious for NTBVs in their growth process. On the one hand, NTBVs face severe liability challenges of newness compared to mature enterprises [25]. To overcome the legitimacy and resource constraints for growth, new ventures must stay aligned with current norms and adopt a guanxi strategy to access the legitimacy and resources granted by the government and market to grow [26]. On the other hand, innovation is an intrinsic attribute of technology-based enterprises [27]. Meanwhile, the changing market demands urgently require NTBVs to implement an innovation strategy to actively search for transformations and opportunities in technology [28] and products [29] to effectively differentiate from competitors and establish competitive advantages. In the actual operation of a business, however, the two types of enterprise strategies are not black or white [30]. Enterprises seek to differentiate through an innovation strategy [7] and build legitimacy through a guanxi strategy [3]. The optimal distinctiveness perspective provides a combinatorial explanation for how NTBVs can balance these two strategies, emphasizing that enterprises differentiate or legitimize activities in different strategic dimensions and then combine them in a complementary manner [12]. At this point, the configurational perspective can be applied to investigate the effect of the interaction and combination of guanxi and innovation strategies on NTBVs’ growth [11]. Moreover, context is a significant influencing factor in the optimal matching of “conformity” and “distinctiveness” when new ventures face the dual challenges of legitimacy and differentiation [11]. Therefore, optimal distinctiveness positioning requires the consideration of both types of enterprise strategies and the appropriate context so that “conformity” and “distinctiveness” can reach a balanced state in multiple contexts.

2.2. The Configuration Model of the Driving Mechanism for Enterprise Growth

Enterprise growth refers to the pursuit of self-survival and sustainable development of the enterprise in the process of achieving business objectives and maintaining the enterprise in the business environment, sustaining profit growth, and improving its ability [31]. According to optimal distinctiveness theory, NTBVs need to coordinate different strategic dimensions of conformity and distinctiveness in different contexts and dynamically adjust the coordinated combination of different strategic dimensions following continuously changing contexts in the long-term development process to achieve high-quality growth [12].

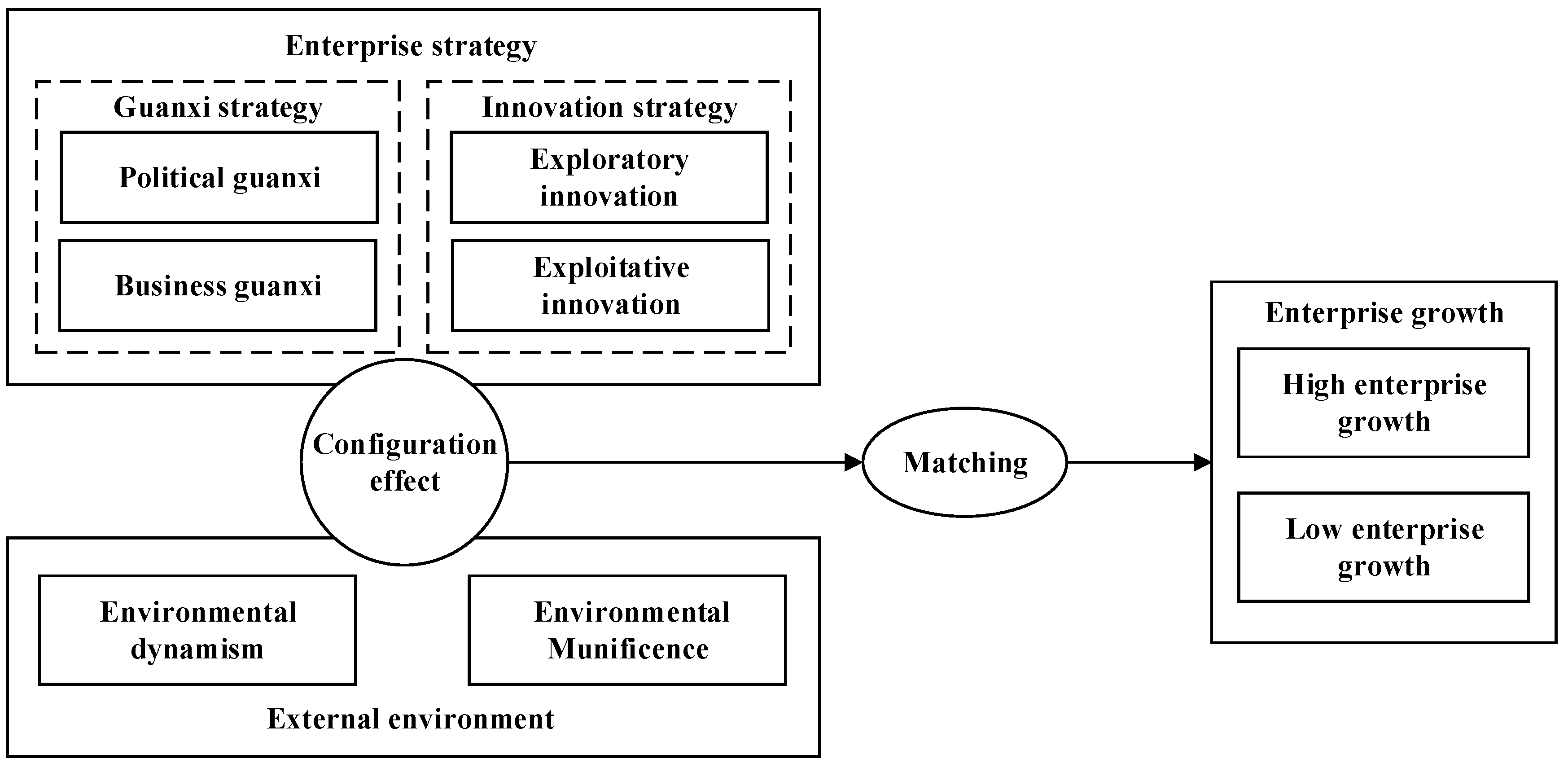

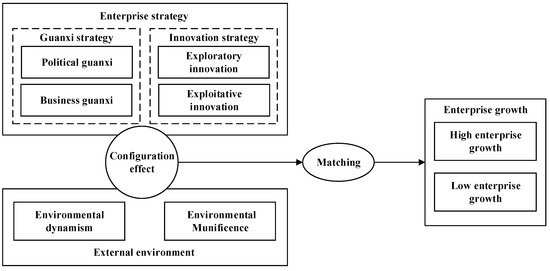

As configuration theory pointed out, combining different elements can create or destroy an enterprise’s competitive advantage as a business characteristic [32]. The matching relationship of multiple elements that affect enterprises’ competitive advantage is fundamental in determining the enterprises’ growth [28]. The process of enterprise growth is intricate and involves several factors, as depicted above. These factors do not have an independent impact on innovation performance; rather, their interaction may lead to different paths toward achieving enterprise growth. The synergy relationship of multiple elements that affect an enterprise’s competitive advantage is fundamental in determining the enterprise’s growth [33]. Hence, in this study, we have adopted a configurational perspective to develop a comprehensive analytical framework of “enterprise strategy-external environment-enterprise growth”. The framework aims to explore the configuration effect of six factors, including the dimensions of enterprise strategy and external environment, on enterprise growth. Among them, enterprise strategy includes guanxi strategy aimed at pursuing convergence and innovation strategy, which targets shaping distinctiveness. Further, the guanxi strategy contains political and business guanxi; the innovation strategy contains exploratory and exploitative innovation; and the external environment level contains environmental dynamism and munificence. The configuration analysis model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The configuration model of the driving mechanism for enterprise growth.

2.2.1. Enterprise Strategy

Enterprise strategy is the process by which management selects and implements a program to ultimately achieve the enterprise’s goals and mission and determines the enterprise’s business objectives, action plans, and direction. Focusing on the theme of NTBVs’ growth, our research emphasizes two distinct enterprise strategies: guanxi strategy and innovation strategy. The guanxi strategy is aimed at providing a sense of legitimacy and entrepreneurial resources to new ventures, while the innovation strategy aims to gain a competitive advantage for new ventures in the market.

- (1)

- Guanxi strategy

References [34,35] pointed out that, in comparison to doing business in Western countries, doing business in China often requires focusing on “whom you know” and “who can help you”, demonstrating that enterprises require allocation of resources to develop and maintain formal or informal relations with other enterprises. Such relations are considered “guanxi”, which reflects a distinctive aspect of Chinese society and illustrates how individuals operate the business more efficiently and effectively [36]. Therefore, Chinese enterprises actively pursue inter-organizational guanxi enhancement as a business relationship management strategy to gain favorable market positions via a reciprocal obligation [13].

According to prior studies [5,35], we pay attention to two types of guanxi strategies, political and business guanxi, at the current stage of planned control and market regulation in China. Specifically, political guanxi is defined as the strategic means through which enterprises achieve growth by tying with officials at various levels of government, ministries, and other regulatory authorities [5,36]. Enterprises that implement political relationships often gain significant benefits in accessing financial resources [37]. Business guanxi is defined as a strategic means of the establishment of contacts with stakeholders such as suppliers, buyers, and distributors [36], which enables enterprises to gain access to critical market information and new knowledge about business partners, which is not easily accessible in the open market.

In the field of entrepreneurship, the above two types of guanxi strategies form an essential foundation for new ventures to access resources and achieve their growth objectives. Research has concluded that positive guanxi connections with political and business entities play a significant role in NTBVs’ growth, which requires drawing resources from the external environment [35,38]. The Chinese government has proved to be a dependable partner, and the governments and enterprises target cooperation rather than competition [35]. Aiming to break the liability of newness and reduce uncertainty and risk, new ventures often maintain favorable relationships with government officials to enhance their access to a range of entrepreneurial resources and supports, such as industrial policies, tax deductions, and exemptions [36]. Additionally, the growth of a new venture is heavily affected by a couple of crucial strategic factors, such as the search for primary customers, the facilitation of business transactions, and the acquisition of knowledge or technology support [39]. Good business guanxi can help new ventures meet these needs and embed themselves more effectively in industrial networks to benefit from the industrial division of labor [40]. However, some studies take the opposite view, arguing that excessive reliance on external guanxi can lead to new ventures progressively becoming used to low-intensive competitive pressure and psychologically locked into a protected industry paradigm, which can consequently lead to a loss of autonomy and poor growth [41]. Specifically, enterprises that possess a significant degree of political guanxi may be perceived as seeking preferential treatment through informal channels [42]. Thus, the trustworthiness of such enterprises is likely to be negatively affected. The above studies fail to reach a consensus view probably because other important factors in addition to the guanxi strategy can influence enterprise growth.

- (2)

- Innovation strategy

Innovation facilitates the establishment of new practices and processes that are radically different from current ones and is considered a notable source of sustainable competitive advantage for new ventures [8]. The enterprise strategizes and executes innovation strategies to ensure a focused drive toward achieving the objectives for earning first-mover, preempting advantages, and monopolistic profits. Hence, exploratory and exploitative innovation, as two essential strategies for innovation, should be more widely used in new venture growth [43].

Exploratory innovation emphasizes deviating from existing knowledge, exploring new technologies, structures, and processes, creating new products, providing new services, and developing new distribution channels [44,45]. Conversely, exploitative innovation stresses building on existing knowledge, technology, and markets to expand existing product and service markets and improve the efficiency of existing distribution channels by upgrading available skills and processes [46,47].

Exploitation and exploration innovation are often central to driving innovation [48]. Even with such potential, the findings of extant research on the effect of two categories of innovation strategies on NTBVs’ growth are mixed. Exploratory and exploitative innovation can improve an enterprise’s performance or minimize performance negative effects that emerge from environmental change [49]. Reference [50] further stated that exploitative innovation emphasizes the efficient utilization of existing resources, which can benefit an enterprise’s short-term survival, while exploratory innovation prioritizes the creation of novel products or services to address unmet needs, which is crucial for long-term success. In contrast, others have pointed out that exploratory innovation represents naturally risky, demanding, and resource-consuming innovative activities, which means that the excessive pursuit of exploratory innovation may result in the overconsumption of firm resources, inducing innovation traps and vicious circles of increasing costs and diminishing enterprise growth [51]. These conflicting results suggest the influence of innovation strategy on enterprise growth might vary in different external situations. This highlights the significance of configurational thinking, which means that the role of innovation strategy in enterprise growth should be analyzed in conjunction with other factors.

2.2.2. External Environment

The growth of a new venture is intimately related to the environment [52]. In addition, contingency theory [13] proposes that effective enterprise growth is achieved when the enterprise’s strategies fit the conditions of its environment. Nonetheless, there is still a lot of existing research that overlooks the key role played by the external environment in the process of focusing on enterprise growth. Hence, to better understand how new ventures achieve growth in China, it is worth considering the common impact of different enterprise strategies and key Chinese entrepreneurial environment characteristics, specifically environmental dynamism and munificence [53].

Environmental dynamism is a term used to describe the magnitude and irregularity of changes in the surroundings of an enterprise, and it is characterized by variations in technology, customer preferences, or product demands, which increases uncertainty for enterprises operating within them [54]. Reference [55] found that the enterprise usually needs help to follow the necessary changes closely when the external environment is filled with uncertainty, and there might be massive volatility both inside and outside the enterprise. At this point, enterprises may fail to keep in step with competitors’ innovations and fully use emerging trends, which leads to new enterprises losing their competitive positions [56]. Nevertheless, a constantly changing and uncertain environment also implies that new opportunities are constantly emerging, and enterprises can actively seize these market opportunities to provide more new products and services. While seeking opportunities in this context carries costs and risks, it can be compensated for by occupying new product market niches [57]. Thus, though the environmental dynamism makes it more challenging for new ventures to develop, it also creates better prospects for their growth.

As per reference [54], environmental munificence can be regarded as “the extent to which the environment could support enterprises’ sustained growth”. Reference [58] elaborated in-depth on environmental munificence and indicated that the degree of munificence affects how quickly businesses thrive within that environment. Especially for new ventures, the liability of newness is a well-recognized threat to their growth, making them more reliant on critical resources in the environment [59]. New ventures can better anticipate technological advancements and react more readily to competitor strategies when operating in a more munificent environment where they can access more precise information about market trends and policy changes [53]. In contrast, in hostile or non-munificent environments, enterprises are less likely to obtain the resources required externally, and even if they do, they require greater investment [60]. In the meantime, enterprises will be caught in a stalemate of intense competition for scarce resources to maintain competitive advantage [61], which is not conducive to rapid growth.

3. Research Design

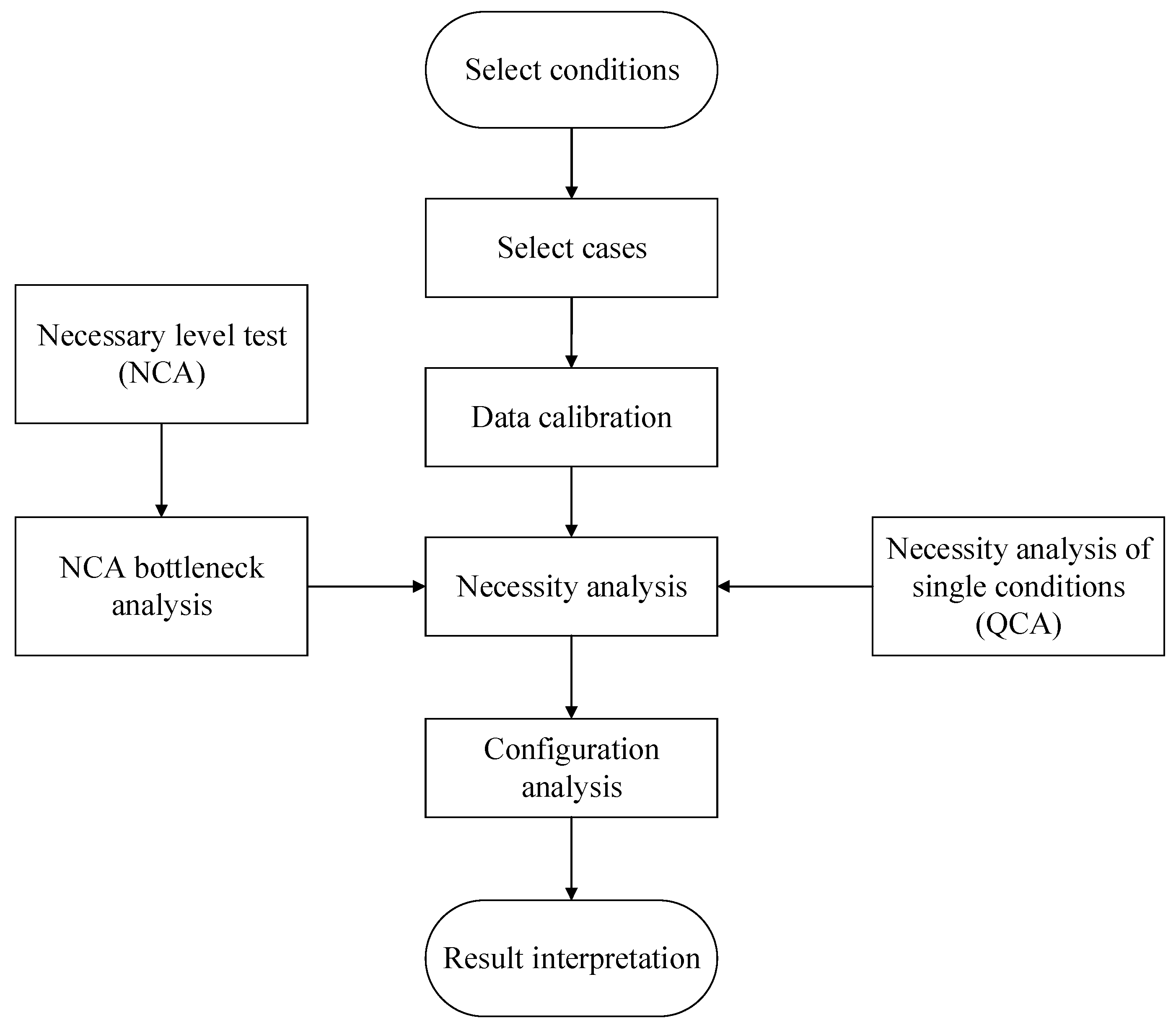

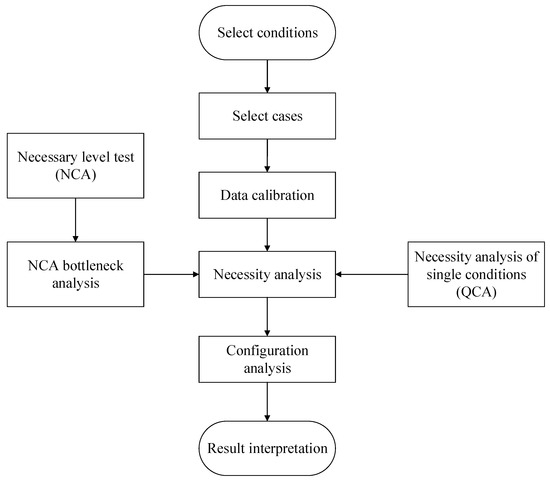

3.1. The Mixed Method of NCA and QCA

The research on “how to formulate a suitable enterprise strategy for the NTBVs’ growth in response to the external environment” belongs to the problem of complex causality, and the thought of configuration, which focuses on “multiple factors and one result” contributes to the interpretation of the complexity of multiple concurrent causes and effects [62]. It is an ideal approach to scrutinize the impact of harmonizing diverse enterprise strategies and contextual factors on the advancement of businesses. In 1987, Ragin proposed the qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) method, which is based on configurations supported by architecture theory and Boolean algebraic calculations, to explore the effects of multiple antecedent variables on outcome variables and can help uncover the complex causal relationships behind phenomena. Despite its capability to qualitatively indicate the necessity of a condition for an outcome, the QCA approach falls short in quantitatively expressing the degree of necessity associated with a particular condition. The NCA method, proposed by reference [14] in 2016, is a complementary tool to the QCA necessity analysis, which quantitatively analyzes the degree to which the antecedent variables are necessary to generate results, thereby effectively compensating for the shortcomings of the QCA method. In the case of fuzzy sets, attention is given not only to binary outcomes but also to the degree of variation, as indicated by the precise membership scores. This aspect adds further value to the integration of NCA with fsQCA. A flowchart of NCA and fsQCA is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of NCA and fsQCA.

In this study, six elements, including guanxi strategy (political guanxi and business guanxi), innovation strategy (exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation), and external environment (environmental dynamism and environmental munificence) are regarded as the antecedent variables, and the new venture growth is considered as the outcome variable. First, we use the QCA approach to qualitatively identify whether a conditional variable is necessary or not to yield the outcome, followed by the NCA to quantitatively diagnose the degrees of the necessary condition variables. Second, the fsQCA method is applied to investigate the sufficient relationship between enterprise strategy, external environment, and enterprise growth, which is appropriate for discovering what kind of enterprise strategy and external environment elements can facilitate the NTBVs’ growth. At the same time, the fsQCA methodology incorporates the benefits of both qualitative and quantitative research, thus addressing concerns regarding the generalizability of qualitative analyses in some instances and, to some extent, addressing the limitations of large-sample analyses for qualitative variations and phenomenological discussions.

3.2. Case Selection and Data Collection

In the selection of cases with the fsQCA method, two aspects are required for the researcher to consider. Firstly, the selected cases should possess identical backgrounds or characteristics to meet the requirements of the same type of overall cases. Second, the selected case must meet the requirements of maximum diversity in a relatively limited sampling. Both cases with “negative” and “positive” outcomes should ideally be included in the research. With the above requirements in view, this study selected NTBVs in the China region that were established within eight years [63] and were mainly involved in the R&D and sales of high-tech products and services. Additionally, these enterprises must include cases of both fast-growing and relatively slow-growing enterprises to ensure that the selected samples can comprehensively and adequately encompass the actual circumstances.

Beyond these requirements, the selection of the variety and quantity of cases would require consideration of the practicalities of this research, i.e., the familiarity with them by the researcher, the availability of data, and the sufficiency of funding. While these would not have a fatal impact on this study, it is also essential that the researchers are motivated to cultivate a “degree of intimacy” with each case considered. Synthesizing these realities, we followed the case selection paradigm of searching, exploring, assuring, adjusting, and reassuring. With the support and assistance of team members’ relationships with the heads or staff of enterprises, incubation parks, industry associations, chambers of commerce, and other relevant institutions, ultimately, 30 NTBVs from different regions and sectors were selected to be further analyzed.

Concerning data collection, this research mainly adopted several ways to distribute and collect questionnaires, such as paper questionnaires filled out on-site, paper questionnaires mailed, and emails. Starting from the beginning of August 2022, a total of 503 questionnaires were handed out or mailed to managers of different levels in various departments of the enterprise over three months. After excluding questionnaires that do not meet the data cleaning criteria (e.g., missing data and extreme regularization of options), valid questionnaires amount to 381, with a valid return rate of 75.7%. The information on each case is shown in Table 1 (request to omit the name), and the characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Essential information on case enterprises.

Table 2.

Summary of respondents.

3.3. Measurement

Obtaining second-hand data about their factual circumstances is also a tremendously demanding task for entrepreneurial corporations. Even the second-hand data that can be obtained would not necessarily reflect the information relevant to the study. In this context, the questionnaire approach has become an essential avenue for obtaining valid information relevant to the study, and some studies demonstrate the reliability and validity of using self-reported questionnaires in the absence of other sources of information [64].

The survey items were evaluated using five-point Likert scales, and their reliability and validity were assessed. Each variable was referenced to a maturity scale and was linguistically translated and contextually modified to account for cultural and contemporary differences. We then invited ten entrepreneurs to put forward their opinions and suggestions on the meaning and expression of questionnaire questions, which led to the final questionnaire. Table 3 presents the scale and its associated items.

Table 3.

Items of the questionnaire.

3.4. Reliability and Validity

The reliability and validity of the questionnaire data were assessed. As illustrated in Table 4, Cronbach’s α of PG, BG, ERI, EII, ED, EM, and EG ranges from 0.887 to 0.933, exceeding the recommended threshold (0.70) and indicating adequate internal reliability. Validity tests examine content validity and mainly construct validity. In this study, the majority of items in the adopted scales were sourced from pre-existing sophisticated scales and suitably modified. Meanwhile, the content validity was perfected in the questionnaire design process and scale formulation utilizing experts’ assessments and recommendations. Furthermore, we employed Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Explained (AVE) as measures to evaluate the construct validity. In terms of the assessment benchmarks for two indicators, a CR value greater than 0.60 and an AVE value exceeding 0.50 are considered desirable [71]. As presented in Table 4, the variables exhibit CR values ranging from 0.922 to 0.947 and AVE values ranging from 0.720 to 0.857. This indicates that the questionnaire data satisfy the criteria for evaluating convergent validity.

Table 4.

Reliability and validity.

3.5. Calibration

The antecedent conditions and outcome need to be calibrated before necessity and sufficiency analysis can be conducted. It is required that the raw data be converted via calibration to a membership score ranging from 0 (completely excluded from the set) to 1 (completely contained in the set), i.e., set membership. The intermediate-set point, which corresponds to a membership score of 0.5 [72], is the value where there is the most uncertainty on whether a case is more in or out of the target set [73].

Fuzzy-set membership scores must be calibrated using both empirical and theoretical data. Referring to reference [74], we obtained relevant data through five-point Likert scales. We additionally added 0.001 to the crossover point according to the accepted procedures [62] to obviate the possibility of theoretical difficulties on the maximum ambiguity point. Thus, three anchors were specified for the calibration process: “5” was set as the point of full membership, “3.001” was set as the crossover point, and “1” was set as the full non-membership point. By setting these three thresholds, fsQCA converted these raw data into fuzzy scores between two qualitatively defined states in the set: full membership (1) and full non-membership (0).

4. Results

4.1. Necessity Analysis

Initially, this study performed a necessity analysis using fsQCA 3.0 to investigate the necessity of high enterprise growth for each condition. Table 5 illustrates that none of the antecedent conditions meet the consistency threshold (0.90), suggesting that the necessary conditions for inducing high enterprise growth are absent.

Table 5.

Necessity analysis of single conditions (QCA).

The QCA method has the capacity to solely assess, in a qualitative manner, whether an antecedent variable is essential to produce a given outcome. NCA cannot only discriminate the necessity of the conditions but also quantitatively analyze the degree of an antecedent variable to generate the outcome [14]. The second step uses NCA to help us answer the question, “What level of the antecedent condition (such as political strategy) should be if an enterprise wishes to reach a certain growth level?” The necessity analysis in NCA differs significantly from that of fsQCA. Therefore, NCA and QCA do not contradict each other; in contrast, they complement each other. Additionally, NCA differs from QCA necessity analysis and should not be used for robustness tests [75]. Necessity analysis was performed using the software R 4.2.1 with the NCA package. Calibrated and raw data can both be used in NCA [14]. Given that calibrated configuration data are more meaningful and consistent with the established relationship [76], we used calibrated data in NCA.

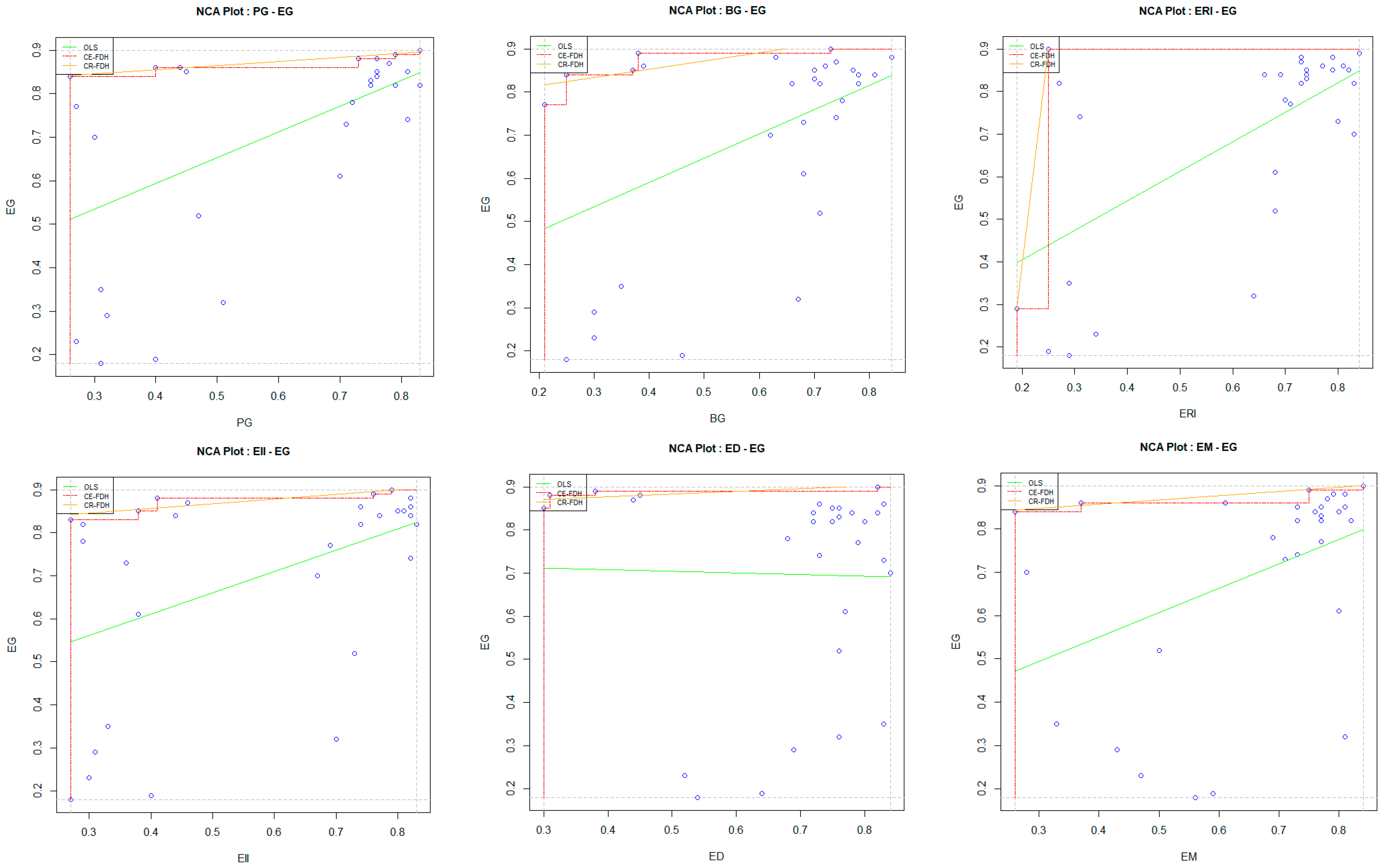

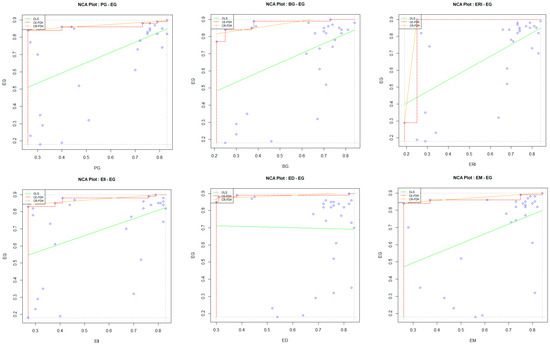

An XY scatter plot features a ceiling line, with the area above the ceiling line (i.e., the upper left corner) indicating that low levels of X cannot correspond to high levels of Y [77]. The scatter plots with ceiling lines are represented in Figure 3. The proportion of space in the upper left quadrant with respect to the total observational space signifies the extent to which X is bound to Y. A greater spatial extent indicates a higher degree of constraint of Y by X [77]. The Ceiling Envelopment-Free Disposal Hull (CE-FDH) and Ceiling Regression-Free Disposal Hull (CR-FDH) techniques are two approaches employed by NCA to construct ceiling contours.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots with ceiling lines.

NCA conducts an analysis of the effect sizes and significance of antecedent conditions to identify the necessary conditions. Additionally, bottleneck level analysis is utilized to evaluate the necessary level values of these antecedent conditions. The effect size (d) is typically measured on a scale of 0 to 1, with values below 0.1 indicating a relatively small effect [14]. Furthermore, NCA conducts Monte Carlo simulations of permutation tests to assess the statistical significance of the results [77].

Table 6 presents the outcomes of the necessary analysis conducted by NCA for individual conditions using CR-FDH and CE-FDH. The table displays the c-accuracy, ceiling zone, scope, effect size, and p-value for each condition. In accordance with the necessary condition of NCA, two requirements must be met: first, the effect size (d) must be greater than or equal to 0.1 [14], and second, the Monte Carlo simulations of permutation tests must indicate that the effect size is statistically significant [77]. The findings of NCA analysis reveal that political guanxi, business guanxi, exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, environmental dynamism, and environmental munificence have effect sizes (d) that are below 0.1, thereby indicating that they do not qualify as necessary conditions for enterprise growth.

Table 6.

Results of necessary condition analysis (NCA).

Furthermore, the outcomes of the bottleneck level analysis are presented in Table 7. The table provides information on the required levels (%) of the condition(s) for various levels (%) of the outcome [78]. As illustrated in Table 7, to attain a 90% level of enterprise growth, a 10.1% level of business strategy and an 8.1% level of exploratory innovation are necessary, while there are no bottleneck levels for the other four antecedent conditions.

Table 7.

NCA bottleneck level (%) table for single necessary conditions.

4.2. Configuration Analysis of Sufficiency Conditions

The combination of conditions associated with a given outcome is referred to as configuration. It may correspond to one, more than one, or no empirical case(s). This paper selected causal conditions and outcome of the model using the fuzzy set truth table algorithm function of fsQCA 3.0 software after necessity analysis, and then the truth table was automatically generated. In this paper, the following threshold criteria were established for configuration analysis to eliminate explanatory variables that may be sufficient for the outcome: The determination of the frequency threshold needs to follow the sample scale. The frequency threshold for cases was set to 1 to retain all observable configurations for this study’s small and medium sample design (N < 50). Consistency is used for measuring “the degree to which instances of an outcome agree in displaying the causal condition”. A criterion for choosing a threshold corresponds to an observed break in the distribution of consistency scores [79]. Following this approach, we used a threshold value of 0.959; we also applied PRI (proportional reduction in inconsistency) to reduce potentially contradictory configurations, using the recommended criterion of 0.7 [80], and manually updated the truth table rows with PRI below 0.7 to 0.

The data were processed using these criteria to obtain the truth table rows that fulfill the conditions and the corresponding configurational paths. Table 8 displays the results of a configurational analysis of the six conditions that have driven the NTBVs’ growth. Following [62], the results were presented with a “⬤” indicating the presence of the antecedent condition in the configuration and a “⊗” indicating the absence of the antecedent condition in the configuration. Large circles denote core conditions, small circles denote peripheral conditions, and a blank space denotes that the presence or absence of conditions does not matter.

Table 8.

Sufficient configurations for high enterprise growth.

The findings indicate the existence of four pathways that lead to enterprise growth. Each column in the table represents a unique conditional configuration that corresponds to one of the four identified pathways. The solution consistency is 0.970803, indicating that approximately 97.1% of the NTBV growth cases that meet the specified configurations exhibit a relatively high level of growth. The solution coverage is 0.763271, which implies that approximately 76% of the high enterprise growth cases can be interpreted using these configurations. The empirical analysis can be deemed valid as both the solution consistency and the coverage of the solutions exceed the threshold values.

By analyzing the condition configurations, it is possible to discern the distinctive adaptive interplay among the guanxi strategy, innovation strategy, and external environment in propelling enterprise growth. Specifically, in S1a and S1b, the “guanxi strategy” and “innovation strategy” factors constitute the core conditions. That is, the enterprise can achieve the integration of “conformity” and “distinctiveness”. First, S1a (PG*BG*ERI*EM) indicates that in a more munificent external environment (peripheral condition), NTBVs can achieve high-level growth through conducting political guanxi (core condition), business guanxi (peripheral condition) and exploratory innovation (core condition). This pathway can explain about 63.3% of high-level growth cases, among which about 20.8% can be exclusively explained using the pathway. The typical case of S1a is XKND Ltd. XKND is an incubated NTBV focused on the R&D and production of Sodium-ion batteries and energy storage technology development. As a sole subsidiary of an electric power engineering construction enterprise, XKND receives necessary and abundant support from the very beginning, including but not limited to plant, machinery, equipment, R&D, and technical personnel. Moreover, XKND inherits the local political and business relationships, enabling XKND to gain sufficient financial and innovative resources to grow. Until now, XKND has realized the mass production of Sodium-ion batteries, indicating an absolute potential for growth for the enterprise and the industry.

Secondly, S1b (PG*ERI*EII*~ED*EM) indicates that in a relatively stable (peripheral condition) and munificent (peripheral condition) external environment, NTBVs can achieve high-level growth through conducting political guanxi (core condition), exploratory innovation (core condition), and exploitative innovation (peripheral condition). This pathway can explain about 40.1% of high-level growth cases, among which about 3% can be exclusively explained using the pathway. The typical case of S1b is STIT Tech Ltd. STIT, a scientific and technological innovation NTBV focusing on urban public transport travel information services and “Internet+ Transport.” “Internet+” and “Digital Transformation” have been well-stressed in recent years in China, which forms a relatively stable and supporting environment for STIT to grow. At the same time, owing to a good relationship with the local government (Suzhou, Jiangsu) and alum association, STIT gains much support and invests abundant innovative resources in intelligent transportation equipment and services products such as new energy supervision, charging pile operation management, intelligent vehicle terminal, and vehicle gateway. Currently focused and specialized in market segments, STIT has become a local star NTBV with continuously growing new products and services.

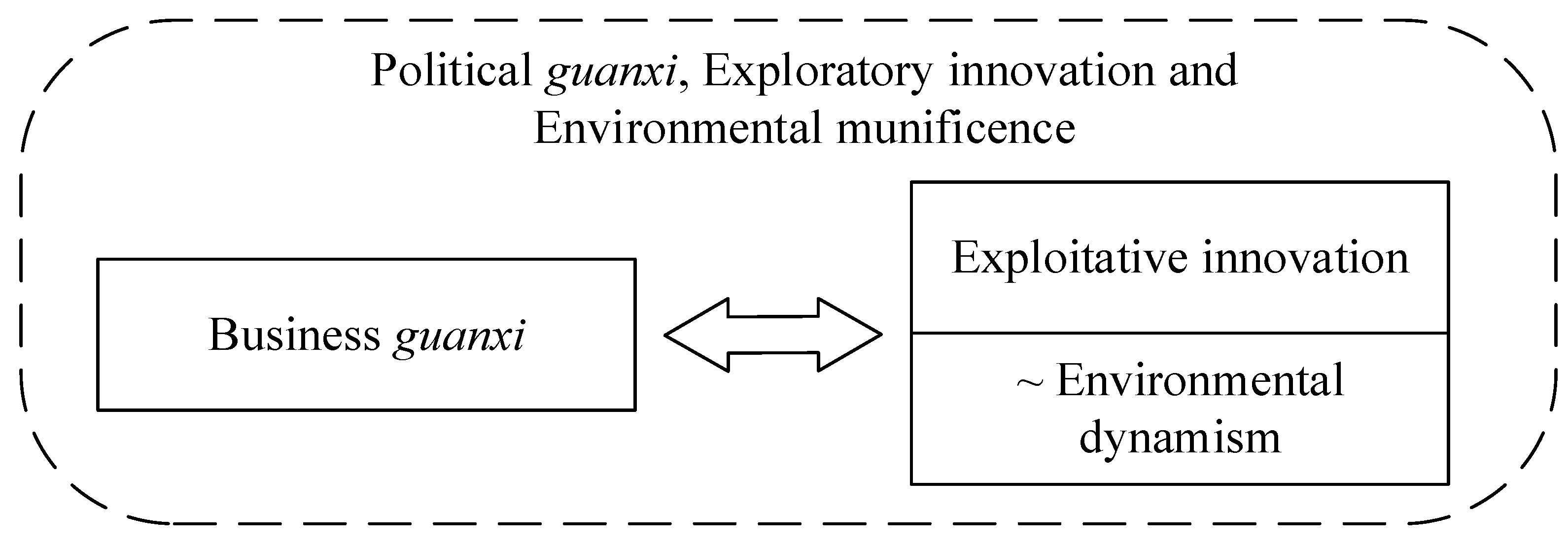

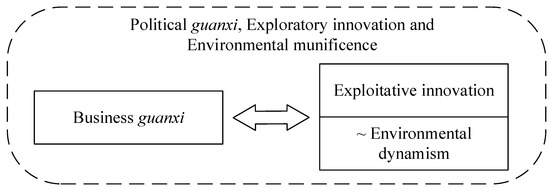

There is a mutual substitution effect between business guanxi and “exploitative innovation + ~ environmental dynamism in the two pathways dominated by political guanxi and exploratory innovation”. In other words, when NTBVs form good business guanxi and carry out exploratory innovation in a more munificent external environment, as long as they meet one single condition of good political guanxi or meet both conditions of implementing exploitative innovation actively and are in a stable external environment, they can achieve growth (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The substitution effect between BG and “EII+~ED”.

S2 (~PG*~BG*ERI*EII*ED*EM) indicates that in a dynamic (peripheral condition) and munificent (peripheral condition) external environment, NTBVs can achieve high-level growth by conducting exploratory innovation (peripheral condition) and exploitative innovation (peripheral condition), even if they lack or fail to form political guanxi (peripheral condition) and business guanxi (core condition). According to the compensatory orchestration perspective of optimal distinctiveness theory, the excess return of one dimension can make up for the lack of other dimensions. From this theoretical perspective, NTBVs in a dynamic and munificent external environment are more likely to obtain resources needed for enterprise growth from the external environment, such as new market opportunities and necessary industry-supporting technologies, products, and market channels. In addition, the strategic advantages of exploratory and exploitative innovation can also help NTBVs win by competing, thus making up for the lack of political and market guanxi dimensions. This pathway can explain about 39.3% of high-level growth cases, among which about 5.4% can be exclusively explained using the pathway. The typical case is TJLY Tech Ltd. TJLY was established in 2017 as a liquid metal thermal management application supplier. Liquid metal is seen as a frontier new material and is valued by the government and business, which creates a rather positive atmosphere and forms an ever-increasing and supportive environment for TJLY. Due to the liabilities of newness, TJLY does not have either enough time or channels to build too many political and business ties in the first place. However, it is worth mentioning that TJLY is an academic entrepreneurial spin-off with solid research and development strengths. TJLY accumulates hundreds of technologies, possesses a liquid metal material preparation process system, and has become a leading enterprise in the industrial application of liquid metal products in China.

S3 (~PG*BG*ERI*EII*ED*~EM) indicates that in a dynamic (peripheral condition) and less munificent (core condition) external environment, NTBVs can achieve high-level growth by forming business guanxi (peripheral condition) and conducting exploratory innovation (peripheral condition) and exploitative innovation (peripheral condition), even if they lack or fail to form political guanxi (peripheral condition). According to the compensatory orchestration perspective of optimal distinctiveness theory, enterprises implementing business guanxi and innovation strategy in dynamic environments can compensate for the deficiencies in political and environmental munificence. Such enterprises can combine market opportunities and innovation strategy to take full advantage of their innovative strengths to accurately grasp their possible strategic opportunities. In addition, business guanxi can help enterprises increase the likelihood of accessing resources in a competitive market while reducing the uncertainty they face in their operations, which can, to a certain extent, reduce their dependence on political guanxi and environmental munificence. This pathway can explain about 38.5% of high-level growth cases, among which about 4.6% can be exclusively explained using the pathway. The typical case is HHSC Tech Ltd. HHSC is an equipment manufacturing service provider in the semiconductor equipment sector. As is known, the semiconductor and semiconductor equipment sectors are dynamic and high-end sectors in China. Typically, only the head enterprises can attract resources and support from investors and institutions, especially those with government backgrounds. Consequently, non-state-owned, medium-sized enterprises like HHSC usually gain limited support from the environment and must rely solely on their efforts to grow. Thus, HHSC turned to promoting innovative capabilities and forming increasing business ties. Now, HHSC has established a service system integrating research and development, production, sales, and after-sales of semiconductor transmission equipment and core components, which received recognition from its business partners such as CETC (China Electronics Technology Group Corporation), ACM Research, and Texas Instruments.

4.3. Robustness Analysis

Even though QCA has gained popularity as a method for examining causal complexity, several academics have questioned whether QCA findings are accurate [81]. For instance, reference [82] even used the term “shaky” to describe it. Hence, robustness analysis is a vitally essential aspect. Common methods include modifying the calibration threshold, altering the consistency threshold, augmenting or reducing the number of cases, and revising the frequency threshold. We conducted a robustness analysis by referring to the above methods of adjusting consistency thresholds. We increased the PRI value from 0.70 to 0.80, and the frequency of the number of cases remained the same, and the results were relatively unchanged from the pre-adjustment period. Following the two determination criteria (the set relation and fit difference of the configurations), this study’s findings were equipped with favorable robustness.

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

A central focus of entrepreneurship research is achieving high growth of new ventures. On the one hand, new ventures would have to manifest a strongly “innovative” position for new product development to achieve high growth. At the same time, they also need “conformity” with market participants to gain resources to achieve high growth. Aiming at exploring how NTBVs can address the tension between conformity and distinctiveness to achieve growth, this research constructs a qualitative comparative analysis model based on optimal distinctiveness theory, combining NCA and QCA methods, which includes six conditions, namely political guanxi, business guanxi, exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, environmental dynamism, and environmental munificence. The following conclusions are ultimately drawn.

First, we discovered that individual elements of enterprise strategy or the external environment do not constitute necessary conditions for yielding high enterprise growth. Second, four types of driving pathways for the NTBVs’ growth from a configuration perspective were identified, each containing different compositions of enterprise strategy and external environment. Third, in the two pathways with political guanxi and exploratory innovation as core conditions, there was a substitution between business guanxi and “exploitative innovation + ~ environmental dynamism”. These alternative relationships illustrate that high levels of enterprise growth can be achieved under certain combined conditions, as “all roads lead to Rome”.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several theoretical advances. Firstly, we have provided theoretical insight into the path mechanisms that explain the NTBVs’ growth from the optimal distinctiveness perspective. For NTBVs, strategy formulation and implementation require consideration of the demands of “conformity” driven by institutional pressures and “distinctiveness” driven by competitive motivations. Drawing upon the optimal distinctiveness perspective at the crossroads of institution theory and strategic management, we considered both conformity-oriented relationship strategies and distinctiveness-oriented innovation strategies to explore how NTBVs can choose or mix between “conformity” and “distinctiveness” to achieve high growth. Additionally, this study responded to the relevant appeal of scholars [19,83] by concentrating on the impact of environmental differentiation on the theory of optimal distinctiveness and primarily examined the external synergistic mechanisms between two environmental characteristics (i.e., environmental dynamism and environmental munificence) and enterprise strategies, developing an interpretation of the boundaries of application of optimal distinctiveness theory.

Secondly, much prior research has looked at the net effect of critical factors on new venture growth. Nonetheless, this net effect approach is at odds with the fact that enterprise growth is a complicated process that requires the interaction of multiple factors. This paper proposed an integration analysis framework for the NTBVs’ growth by applying the thinking of configuration, which involved six factors of guanxi strategy (political guanxi and business guanxi), innovation strategy (exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation), and external environment (environmental dynamism and environmental munificence), thus presenting an exploration of the growth process of NTBVs with diverse pathways that embody “outcome equifinality”. In addition, we interpreted the growth pathways of each enterprise through the corresponding configurations of the case enterprises, which achieved the preliminary convergence of the “amusing” of case studies and the “theoretical” of empirical studies.

Finally, this study adopted a mixed approach that integrates NCA and QCA. Combining NCA and QCA to explore causal complex relationships has not only been applied by scholars in the field of sociological research methodology but is also the latest initiative of scholars [84]. Nevertheless, previous research on new venture growth has been based on traditional statistical analysis methods, such as correlation, multiple regression, and structural equation modeling (SEM), to investigate the binary relationship between the “independent variable and the dependent variable”. NCA and fsQCA both (in different ways) add value to traditional data analytic approaches [14]. The dominance of fsQCA is used for analyzing the complex causal relationships of sufficient conditions and is perfectly suited for solving the relationship between conditions such as enterprise strategy and external environmental dimensions (configurations) and the NTBVs’ growth in this paper. NCA, as a new approach to the analysis of necessity conditions, which can make the necessary statements in degree, can further complement fsQCA by generating more precise or complete results [76], particularly suitable for analyzing the relationship between the level of each antecedent conditions and the level of enterprise growth. This research combined the NCA and QCA methods to break through the limitations of traditional research methods and further enrich the research methodology system, making the research findings more fine-grained and robust.

5.3. Practical Implications

From a practice perspective, this paper proposes the following directions and implications for improving the survival rate and achieving sustainable development of China’s NTBVs. On the one hand, the results of the configuration analysis reveal that the concurrent synergy of multiple conditions at the enterprise strategy and external environment levels generates four feasible pathways that can propel growth, i.e., enterprise growth has the characteristic of “all roads lead to Rome”. Additionally, it is worth noting that a single factor, such as political guanxi, cannot satisfy the growth needs of NTBVs. Instead, the combination of political guanxi, business guanxi, exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, environmental dynamism, and environmental munificence should be emphasized. For this reason, when new ventures are encountering both conformity and distinctiveness requirements, managers should not unquestioningly engage in strategic planning and formulation. Instead, they should take a holistic perspective, combining the current external environment with the enterprise’s characteristics to devise a strategy that best fits the enterprise’s situation and the external environment and select a growth-driven path that is suitable for the enterprise’s development.

On the other hand, just because the NTBVs’ growth can be achieved through synergistic effects of other factors at low levels of environmental munificence (see configuration S3), it does not mean the role of environmental munificence in the NTBVs’ growth can be disregarded. It is evident that a strongly inclusive external environment is more likely to provide enterprises with access to the required industry-supporting technologies, critical components, and market channels, making it more favorable to expanding new careers. All of this requires the government, industry associations, etc., to provide certain support in aspects such as technology, policies, funds, talents, and market channels, as sufficient as possible to build an external environment that is relatively inclusive.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides novel insights into NTBVs’ growth research, it has several limitations that create possibilities for future research. First, this research examined the paths that drive the NTBVs’ growth, yet life-cycle theory indicates that corporations have distinct traits at various stages of their growth [85], and the strategic decision-making and resource allocation dynamically adjust with the life cycle. Future research could consider the differences in the enterprises’ growth paths at different life cycle stages, thereby providing more target-oriented growth strategies for NTBVs at different phases. Second, we conducted some qualitative analysis based on quantitative analysis in the case study, which contributed to revealing the mechanism underlying the quantitative research. Nevertheless, large-sample QCA studies make it hard to conduct qualitative analysis as thoroughly and abundantly as case studies. Future researchers can conduct more in-depth case studies on various driving modes of enterprise growth to dissect the driving process of new venture growth and better elucidate the research questions of “why” and “how”. Third, this study merely concentrated on the impact of enterprise strategy and external environmental factors on enterprise growth. Future studies could establish a more comprehensive framework to investigate the impact of multiple factors on enterprise growth from various layers and perspectives, such as the characteristics of entrepreneurs/entrepreneurial teams and organizational capabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and D.D.; Methodology, J.G. and Q.Z.; Software, J.G.; Writing—original draft, Q.Z.; Writing—review and editing, J.G. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Dalian University of Technology (Approval code: DUTSEM240117-01; Approval date: 17 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, L.M.; Aram, J.D. Networking and growth of young technology-intensive ventures in China. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited—Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Zeitz, G.J. Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Murray, J.Y. Exploratory and exploitative learning in new product development: A social capital perspective on new technology ventures in China. J. Int. Market. 2007, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.F.L.; Yang, Z.L.; Huang, P.H. How does organizational learning matter in strategic business performance? The contingency role of guanxi networking. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semadeni, M.; Anderson, B.S. The follower’s dilemma: Innovation and imitation in the professional services industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1175–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Chen, B.; Chen, J.Y.; Bruton, G.D. Dysfunctional competition & innovation strategy of new ventures as they mature. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.H.; Chen, C.J.; Lin, B.W. The roles of political and business ties in new ventures: Evidence from China. Asian Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeuscher, K.; Bouncken, R.; Pesch, R. Gaining legitimacy by being different: Optimal distinctiveness in crowdfunding platforms. Acad. Manag. J. 2021, 64, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, B.; Zietsma, C. Finding the threshold: A configurational approach to optimal distinctiveness. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.Y.F.; Fisher, G.; Lounsbury, M.; Miller, D. Optimal distinctiveness: Broadening the interface between institutional theory and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Z.; Ellinger, A.E.; Tian, Y. Manufacturer-supplier guanxi strategy: An examination of contingent environmental factors. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Necessary condition analysis (nca): Logic and methodology of “necessary but not sufficient” causality. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L. To be different, or to be the same? It‘s a question (and theory) of strategic balance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Tse, D.K.; Chan, T.H. Gaining legitimacy and host market acceptance: A CRM analysis for foreign subsidiaries in China. Int. Market. Rev. 2023, 40, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junquera, B.; Barba-Sánchez, V. Environmental Proactivity and Firms’ Performance: Mediation Effect of Competitive Advantages in Spanish Wineries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schad, J.; Lewis, M.W.; Raisch, S.; Smith, W.K. Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 5–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.J.; Yu, C.M.J.; Huang, K.F. Strategic similarity and firm performance: Multiple replications of Deephouse (1999). Strateg. Organ. 2021, 19, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.E.; Jennings, P.D.; Greenwood, R. Novelty and new firm performance: The case of employment systems in knowledge-intensive service organizations. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 338–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, C.; Santalo, J. Platform competition: Strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1331–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochkabadi, K.; Kleinert, S.; Urbig, D.; Volkmann, C. From distinctiveness to optimal distinctiveness: External endorsements, innovativeness and new venture funding. J. Bus. Ventur. 2024, 39, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, R.F.J. What’s the value of being different when everyone is? The effects of distinctiveness on performance in homogeneous versus heterogeneous categories. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Amore, M.D.; Le Breton-Miller, I.; Minichilli, A.; Quarato, F. Strategic distinctiveness in family firms: Firm institutional heterogeneity and configurational multidimensionality. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2018, 9, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Du, J.J.; Junaid, D.; Hao, X.L. How new venture strategies promote firm performance: An optimal distinctiveness perspective. Innov. Organ. Manag. 2022, 16, 100782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.J.; Sohn, D.W. Roles of entrepreneurial orientation and guanxi network with parent university in start-ups’ performance: Evidence from university spin-offs in China. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2015, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.Q.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhang, S.S. Technology innovation ambidexterity, business model ambidexterity, and firm performance in Chinese high-tech firms. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2018, 26, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M.J.; McGee, J.E. Business and technology strategies and new venture performance—A study of the telecommunications equipment industry. Manag. Sci. 1994, 40, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuscheler, D.; Engelen, A.; Zahra, S.A. The role of top management teams in transforming technology-based new ventures’ product introductions into growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.H.; Ooi, K.B.; Chong, A.Y.L.; Sohal, A. The effects of supply chain management on technological innovation: The mediating role of guanxi. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2018, 205, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Haugh, H.; Chambers, L. Barriers to Social Enterprise Growth. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1616–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Configurations revisited. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.T. Business model innovation, legitimacy and performance: Social enterprises in China. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2693–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, X.P.; Huang, S.S. Chinese guanxi: An integrative review and new directions for future research. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2013, 9, 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.J.; Du, Q.X.; Sohn, D.; Xu, L.B. Can high-tech ventures benefit from government guanxi and business guanxi? The moderating effects of environmental turbulence. Sustainability 2017, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Chung, H.F.L. The moderating role of managerial ties in market orientation and innovation: An asian perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2431–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Liu, H.L.; Yin, J.; Qi, Y.F.; Lee, J.Y. The effect of political turnover on firms’ strategic change in the emerging economies: The moderating role of political connections and financial resources. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.Y.; Zhuang, M.Z.; Zhuang, G.J. When does guanxi hurt interfirm cooperation? The moderating effects of institutional development and IT infrastructure capability. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Baker, J.; Schniederjans, D. Bullwhip effect reduction and improved business performance through guanxi: An empirical study. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2014, 158, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderblom, A.; Samuelsson, M.; Wiklund, J.; Sandberg, R. Inside the black box of outcome additionality: Effects of early-stage government subsidies on resource accumulation and new venture performance. Res. Pol. 2015, 44, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.W.; Tsang, E.W.K.; Luo, D.L.; Ying, Q.W. It’s not just a visit: Receiving government officials’ visits and firm performance in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2016, 12, 577–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.M.; Hsu, M.K.; Liu, S.S. The moderating role of institutional networking in the customer orientation-trust/commitment-performance causal chain in China. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2008, 36, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.; Wong, P.K. Exploration vs. Exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organ Sci. 2004, 15, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.F.; Xu, P.; Llerena, P.; Jahanshahi, A.A. The impact of the openness of firms’ external search strategies on exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.H.; Liu, Z.Y. Policies and exploitative and exploratory innovations of the wind power industry in China: The role of technological path dependence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 177, 121519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, K.B.; Candi, M. Investigating the relationship between innovation strategy and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.M.; Di Benedetto, C.A.; Zhao, Y.Z.L. Pioneering advantages in manufacturing and service industries: Empirical evidence from nine countries. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 811–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Han, S.J. Innovation ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for startup and established restaurants and impacts upon performance. Ind. Innov. 2020, 27, 340–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.X.; Sharma, P.; Zhan, W.; Liu, L. Demystifying the impact of CEO transformational leadership on firm performance: Interactive roles of exploratory innovation and environmental uncertainty. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Podoynitsyna, K.; van der Bij, H.; Halman, J.I.M. Success factors in new ventures: A meta-analysis. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Anokhin, S.; Yin, M.M.; Hatfield, D.E. Environment, resource integration, and new ventures’ competitive advantage in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2016, 12, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Beard, D.W. Dimensions of organizational task environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1984, 29, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Q.; Zeng, S.X.; Lin, H.; Ma, H.Y. Munificence, dynamism, and complexity: How industry context drives corporate sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, G.B.; Sirdeshmukh, D.; Voss, Z.G. The effects of slack resources and environmental threat on product exploration and exploitation. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrogiovanni, G.J. Environmental munificence—A theoretical assessment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.K.; Endres, M.L. The influence of regional economy- and industry-level environmental munificence on young firm growth. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goll, I.; Rasheed, A.A. The moderating effect of environmental munificence and dynamism on the relationship between discretionary social responsibility and firm performance. J Bus. Ethics 2004, 49, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H.P. Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organ Sci. 2009, 20, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, K.; Wiklund, J.; DeTienne, D.R.; Cardon, M.S. Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: Divergent exit routes and their drivers. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, C.; Dowling, M.; Welpe, I. Firm networks and firm development: The role of the relational mix. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 514–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaire, M. Young and no money? Never mind: The material impact of social resources on new venture growth. Organ Sci. 2010, 21, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, M.; Zellweger, T. Relational embeddedness and firm growth: Comparing spousal and sibling entrepreneurs. Organ Sci. 2018, 29, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y.D. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Liu, J. Dynamic capabilities, environmental dynamism, and competitive advantage: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2793–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Banbury, C. How strategy-making processes can make a difference. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, E.; Ayavoo, R. The mediating role of knowledge application in the relationship between knowledge management practices and firm innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Schussler, M. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in entrepreneurship and innovation research—The rise of a method. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Woodside, A.G. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in information systems and marketing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorkavoos, M.; Duan, Y.Q.; Edwards, J.S.; Ramanathan, R. Identifying the configurational paths to innovation in SMEs: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5843–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Z.; Kim, P.H. One size does not fit all: Strategy configurations, complex environments, and new venture performance in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.E. What kinds of countries have better innovation performance? A country-level fsQCA and NCA study. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; van der Laan, E.; Kuik, R. A statistical significance test for necessary condition analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, B.; Dul, J. Analyzing relationships of necessity not just in kind but also in degree: Complementing fsQCA with NCA. Sociol. Methods Res. 2018, 47, 872–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, D.; Zollo, M.; Hansen, M.T. Faking it or muddling through? Understanding decoupling in response to stakeholder pressures. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1429–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, M.; Thiem, A. Often trusted but never (properly) tested: Evaluating qualitative comparative analysis. Sociol. Methods Res. 2020, 49, 279–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogslund, C.; Choi, D.D.; Poertner, M. Fuzzy sets on shaky ground: Parameter sensitivity and confirmation bias in fsQCA. Polit. Anal. 2015, 23, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, H.; Funk, R.J.; Owen-Smith, J. The authenticity premium: Balancing conformity and innovation in high technology industries. Res. Pol. 2021, 50, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Witt, M.A.; Aguilera, R.V.; Verbeke, A. The contributions of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazin, R.; Kazanjian, R.K. A reanalysis of miller and friesen life-cycle data. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).