Abstract

Given the global growth of foreign capital flows, foreign investments hold significant potential for achieving sustainable development. Thus, this paper aims to highlight the key factors of FDI. In particular, it analyzes the effects of financial development and natural resources on FDI and how institutional quality and institutional distance can moderate these effects. The study used the dynamic panel gravity framework with two-step system GMM estimators to assess whether the developed financial system, better institutions, and possessing natural resources influence the outward FDI of G7 countries to host countries over the period 2002–2021. The results show that a well-developed financial system and well-functioning institutions in host countries are important prerequisites for FDI inflows. We find that the relationship between financial development and FDI is positively and significantly moderated by both institutional quality and institutional distance. Contrarily, these factors negatively moderate the connection involving natural resources and FDI. The significant negative association between institutional indicators’ interaction with natural resources indicates that natural resources play a key role in FDI, while joint policies for institutions and natural resources considerably decrease FDI inflows. Moreover, we discover that factors like GDP per capita, logistics infrastructure, and population could attract and handle more FDI. Based on the findings, the study recommends that host governments should focus on policies that strengthen the financial system, reduce institutional and legislative barriers, and enhance institutional quality and business environment to grant foreign investors access to all areas of their economies. Moreover, host governments should brand separate policies for institutions and natural resources to improve their economic advantages.

1. Introduction

The global growth of foreign capital flows, as well as the expanding magnitudes of foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows in recent years, have prompted governments—in both developed as well as developing countries alike—to attract multinational enterprises (MNEs) with various intensive packages to gain access to their resources, market access, capital technology, skills, and other benefits, to accelerate the process of their development. Furthermore, it is generally acknowledged that FDI tends to stimulate economic growth in the target country by increasing the rate of capital formation and indirectly leading to human capital growth, technical transfers, and increased competitiveness [1,2].

As a result, host governments around the world have prioritized FDI as a vital source of foreign money for a country’s economic development and industrialization, a crucial instrument to the socio-economic transformation and restructuring [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], as well as an important source for economic sustainability [9]. Indeed, researchers widely agree that while large amounts of FDI inflows can sustain the economic growth of the host countries, they may not always have spillover effects that boost the competitiveness and productivity of all companies, including domestic ones, and have a favorable and notable impact on their economic development [2,4,6].

However, to increase FDI in their countries, several host countries have made significant efforts and continue to do so to ensure long-term political and economic stability and draw in more foreign investors [9]. Many of these countries, such as Latin American countries, have now lowered their institutional and legislative barriers to grant foreign investors access to all areas of their economies [10,11]. After the pandemic crisis, confirming the significant role that FDI plays in their economic recovery strategies, developing economies continued to adopt measures that were primarily designed to liberalize, promote, or ease investment. Mining, energy, finance, transportation, and telecommunications have all taken steps toward liberalization. Several countries have simplified administrative procedures for investors or expanded incentive programs for investment [12]. Though they grew more slowly than those in developed regions, FDI flows to developing nations still rose by 30% to $837 billion. However, FDI to developing countries is disproportionally distributed, with $83 billion going to Africa from $39 billion in 2020, $619 billion flowing into Asia regions (which accounts for 40% of global FDI), and 56% to $134 billion going to Latin America and the Caribbean [13].

Since policy efforts to attract FDI have had varying degrees of success across countries, this study examines the factors that account for these differences in FDI to host countries, particularly those from the world’s advanced economies, like G7 nations. These latter focused on investing more in host countries with well-developed financial systems, sound institutions, and natural resources, which have significant impacts on foreign investors’ motivation. For example, the outward FDI flows from G7 nations to host countries have recorded expansion from $57,000 billion in 2010 to $98,500 billion in 2020. In this respect, numerous studies have shown that investment in natural resources, including non-fuel and fuel resources, has recently been a substantial factor in FDI flows from most origin nations [14,15,16,17]. Other studies also suggested that better institutions and sound governance infrastructure of host countries are some of the leading determinants of the outward FDI [18,19,20,21,22] and, hence, investment in natural resources with a better institutional environment is likely to attract more foreign investors into countries rich in natural resources [23,24,25,26]. The importance of financial markets and institutions in attracting FDI has also received particular attention in FDI research, meaning that well-developed financial systems in host countries encourage FDI inflows [27,28,29,30]. However, Dunning [31] contended that foreign investors have become more susceptible to institutional quality as their motivations have switched from market and resource-seeking to efficiency-seeking.

Though the growing number of papers looking at the determinants of FDI, there is still scope for further research into the roles played by financial development, institutional quality, and natural resources in fostering economic sustainability. To fill this evidence gap, this paper examines the factors that influence inward FDI with an emphasis on financial development, natural resources, and institutional quality. However, the vulnerability of the financial system and the weakness of the public institutions of host countries discourage foreign investors and may have negative spillovers on their businesses. The primary objective of this study is to discover how the G7 firms’ investment decisions are influenced by the host countries’ financial institutions, natural resources, and institutional quality during the sample period of 2002–2021. One can see that in recent years, the G7 nations have become more open to institutions when making choices about foreign investments. On the other side, it is well-known that the investments of G7 nations are dependent on the availability of natural resources (such as metal, ore, and fuel) in the host countries. Since the institutional quality and natural resource endowment of host countries do matter for the outward FDI of G7 nations, as several host countries converge in terms of natural resources and institutions, they will be able to receive more FDI from G7 nations.

The present study makes several contributions to the body of literature. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first explanation of the phenomena of the moderating impact of institutions in terms of institutional quality and institutional distance in the natural resources–FDI nexus and finance–FDI nexus. Second, in addition to the six institutional quality indicators created by Kaufmann et al. [32], we employ the corruption perception index (CPI) as an additional moderator variable [26,33,34] to explain whether governance and institutional quality factors of host countries influence the G7’s outward FDI. Third, this study employs the most comprehensive proxy for measuring the logistics performance of a host country–the logistics performance index [35,36]. Moreover, to cover the complexity and multidimensionality of the financial system, we rely on the IMF’s financial development index, which considers the accessibility, efficiency, and depth of financial institutions and markets. This index is the most complete measure of financial development [37]. Fourth, for a robustness check, we follow Aleksynska and Havrylchyk [23] and Le and Kim [38] by considering positive and negative institutional distance as additional variables to discriminate among FDI in host countries with better or poorer institutions than at home countries. Finally, we make use of data on recent inward FDI stocks from 2002 to 2021, which covers 45 host countries and 7 (G7) source countries. The dynamic panel gravity models with two-step system generalized method of moments (GMM) estimations are used to efficiently handle the endogeneity issue.

2. Literature Review

2.1. FDI, Quality of Institutions and Natural Resources

Previous studies have supported the significance of institutional quality as a driver of FDI. Most of them highlighted that improvement in institutional quality is positively correlated with more inward FDI and that good governance and better institutional quality lowers the volatility of FDI flows [18,19,20,22,39,40,41]. The empirical research has also begun to take into account the effects of institutional distance [19,23,41,42,43,44,45] and natural resources [16,23,26,41,46] as major drivers of FDI. For instance, Busse and Hefeker’s [20] study on the relationships between FDI, institutions, and political risk for 83 developing countries from 1984 to 2003 discovered that a number of political risk’s sub-components, such as democratic accountability, internal and external conflict, law and order, bureaucracy quality, government stability, and corruption, have a substantial power on FDI inwards. In 15 Asian nations between 1996 and 2007, Mengistu and Adhikary [47] looked into how well-run governments affected FDI and found that all governance indicators have considerable impacts on FDI inwards. Using a panel data gravity model, Subasat and Bellos [48] looked into how institutional factors affected FDI in Latin America between 1985 and 2008. Their empirical findings support Bellos and Subasat’s [21] findings and opine that poor governance encourages FDI in both Latin America and transition countries. Hossain and Rahman [49] looked at the relevance of governance’s impact on inward FDI for a panel of 80 developing countries from 1998 to 2014. They discovered that all institutional factors have significant favorable effects on FDI flow. Younsi and Bechtini [40] conducted research on institutions and FDI in emerging economies from 1996 to 2012. They discovered that factors like regulatory quality, government effectiveness, and political stability have favorable and significant impacts on FDI. It discovered that the remaining set of institutions are significantly and adversely linked to FDI. Bouchoucha and Benammou [50] looked into the FDI and institutional quality nexus in 41 African economies and found that FDI attractiveness is significantly correlated to regulatory quality, government effectiveness, and corruption control.

Additionally, institutional distance has recently been discovered as a significant factor influencing outward FDI. It has an unequal influence on FDI since it depends on whether investors select nations with strong or poor institutions. Large institutional distance in the latter instance prohibits FDI, although this deterrent effect is lessened in host countries with abundant resources [23]. The empirical investigations of Habib and Zurawicki [39] and Benassy-Quéré et al. [19] confirmed the link between the choice of destinations for outward FDI and the similarity of institutional quality of host and origin countries. The results showed that investors from developed countries favor investing in countries with comparable institutional environments. According to Buckley et al. [46], most of the Chinese outward FDI was government-led and supported by political ties and contacts between China and other emerging host countries. Therefore, they suggested that China’s outward FDI is drawn to natural resources in countries with high political risk.

Qi and Zou [42] pointed out that there will be more FDI outflows when the host and home countries are more distant from one another in terms of economic and legal institutional distance. Tomio and Amal [43] investigated the factors that influence Brazil’s outward FDI and demonstrated that institutional distance has a significant positive effect on outward FDI. However, they argued that this effect is constrained by the host country’s size and the scale of its bilateral trade. Zhang and Xu [44] investigated how China’s FDI in One Belt, One Road countries is impacted by institutional and cultural distance. According to their findings, institutional distance and China’s outward FDI are negatively associated. In a recent study, Li et al. [45] looked at how outward FDI to emerging countries is sensitive to institutional distance from China and concluded that Chinese FDI is more likely to flow into host emerging countries with poor institutional environments.

Furthermore, a number of studies demonstrate that investments in natural resources have recently been a major factor in the growth of FDI from developed countries [23,26,41,46]. FDI and institutional distance have been shown to be positively correlated in some research [26,43] but negatively correlated in others [44]. However, the abundance of natural resources in the host countries can help mitigate the negative effects of institutional distance between the host and home countries. Its appeal seems to be a key driver of outward FDI. For example, Kamal et al. [41] examined the linkage between institutional quality, natural resources, and China’s outward FDI. Their findings revealed a strong correlation between natural resources and China’s outward FDI in countries with poor institutional environments. When the interplay between natural resources and institutional quality is taken into account, the results indicate that host country institutions have an impact on China’s outward FDI, but only in nations having non-fuel natural resources. By examining the interaction conditions between institutional quality and non-fuel resources, they demonstrated that outward FDI from China is not affected by institutional quality. Using a gravity model approach, Feng et al. [51] explored the shifting contributions of 173 host economies’ natural resources and financial development in attracting Chinese outward FDI over the period 2003–2015. They discovered that China’s outward FDI location decisions are mostly influenced by the host nation’s natural resource endowment. Muhammad and Khan [26] looked at the interaction between institutions and natural resources in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in relation to outward FDI from G7 countries for the 2009–2017 period. They found that institutional quality attracts FDI, while the interplay among natural resources and institutional qualities deters FDI.

2.2. FDI and Financial Development

Financial systems can influence FDI in several ways by reducing transaction costs, improving liquidity, enforcing financial contracts as well as allocating resources [15]. Effective financial intermediaries minimize unnecessary costs associated with processes, direct resources to profitable investing activities, and offer tools to spread out risk. This makes it possible for businesses both inside and outside of the country to obtain more affordable access to external capital. According to Kinda [52], foreign investors may find themselves with less information than local investors regarding their chances and potential hazards in a given sector. Therefore, to enable investors to make informed investment decisions, well-established financial markets must provide them with access to market information and financial support. Moreover, it is suggested by Agbloyor et al. [53] and Kaur et al. [27] that MNEs can lower their cost of capital in an effective banking system and have access to well-functioning financial services because an advanced banking system can offer competitive foreign exchange services, lower costs, quicker transactions, and easy access to financing. However, Ezeoha and Cattaneo [15] argued that a weak and inefficient banking sector may deter foreign investment. They suggested that MNEs do not turn to bank debt or credit restrictions when looking for resources to finance operations; instead, they exclusively resort to their parent firm. Additionally, fragmented financial intermediation, which limits FDI inflows, could be a challenge for business activities in both domestic and international trade. According to Otchere et al. [54], MNEs are more likely to list on stock exchanges in countries with well-developed stock markets because doing so not only helps them raise cash but also helps them establish their brand identity in the local market. However, poor institutions and regulations, asymmetric information, significant volatility, and speculative behavior could lead to an inefficient stock market. Foreign companies decide against listing their securities on such stock markets due to the risk of receiving less money in the form of a higher share price, being unable to raise the required capital, or not turning a profit on their investment. Soumaré and Tchana [55] used panel data for 29 emerging countries from 1994 to 2015 to investigate the relationship between FDI and financial development. They illustrated how the expansion of the stock market assisted the host economies in attracting more FDI by using banks and stock markets as indicators of financial development. Additionally, the increasing accessibility of this cross-border capital promoted stock market growth that was more rapid. Their findings on the link between FDI and banking progress, however, were unclear.

Varnamkhasti et al. [28] suggested that banks and stock markets, have a significant association with FDI inwards in developing countries. They argued that financial market expansion might make it easier to provide financial services and promote more inward FDI. Desbordes and Wei [29] examined how financial development affected FDI from outside sources and host countries. The authors used data from 83 source countries and 125 host countries from 2003 to 2006. Results showed that FDI in greenfield, expansion, and mergers and acquisitions was boosted by the financial development of both the host and source countries. They asserted that directly boosting access to capital sources and indirectly encouraging manufacturing activity are two ways that financial development enhanced FDI. For a group of 79 countries that are partners in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Islam et al. [56] studied the institutional quality’s moderating effect on the link between finance and FDI from 1999 to 2017. They discovered that the financial progress of BRI host nations significantly draws FDI. The relationship between finance and FDI is shown to be substantially influenced by the moderating effect of institutional quality. According to the in-depth examination, financial markets are less appealing to FDI than financial institutions. Irandoust [57] examined the impact of the financial sector’s growth on FDI for eight post-communist nations between 1990 and 2016 and found that it provided MNEs and their local affiliates with access to finance and financial services at lower transaction costs. They suggested that a well-established financial system, together with sound governance rules and robust investor protection, might increase outward FDI into these nations.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The sample countries consist of 45 host countries and 7 (G7) source countries, and the sample period runs from 2002 to 2021. The complete list of host and source countries is listed in Table A1 in Appendix A. We refer to the OECD database [58] for extracting the bilateral FDI inflows. Prior research [19,23,26,40,59,60,61] has shown that stock value is a more reliable indicator of FDI location distribution than flow. Therefore, we use FDI stock rather than FDI flows. The data on real GDP per capita, population, logistics performance index (LPI) as a proxy for measuring logistics efficiency and infrastructural abilities of a host country, fuel exports, and ores and metals exports (% of merchandise exports) are downloaded from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) database [62]. Following Islam et al. [56] and Irandoust [57], we use a new broad-based financial development index suggested by the International Monetary Fund [37]. Institutions data are gathered from the World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (WGI) database [63] created by Kaufmann et al. [32]. In this study, we use six aggregate measures of institutional quality–voice and accountability (VAA), political stability and absence of violence (PS), government effectiveness (GE), regulatory quality (RQ), rule of law (RL), and control for corruption (CC). Drawing on data from the six governance factors (VAA, PS, GE, RQ, RL, and CC), we construct an institutional distance variable—a difference between the host and source country in terms of institutional indicators. This measure is frequently employed in the FDI literature [17,23,26,43,44,64,65].

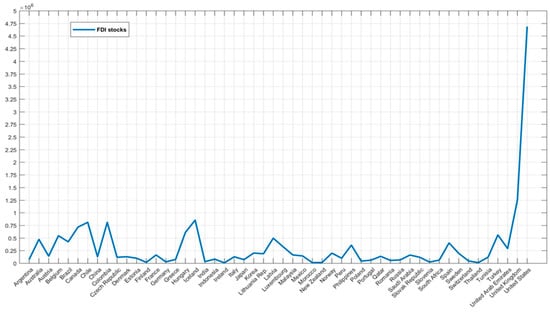

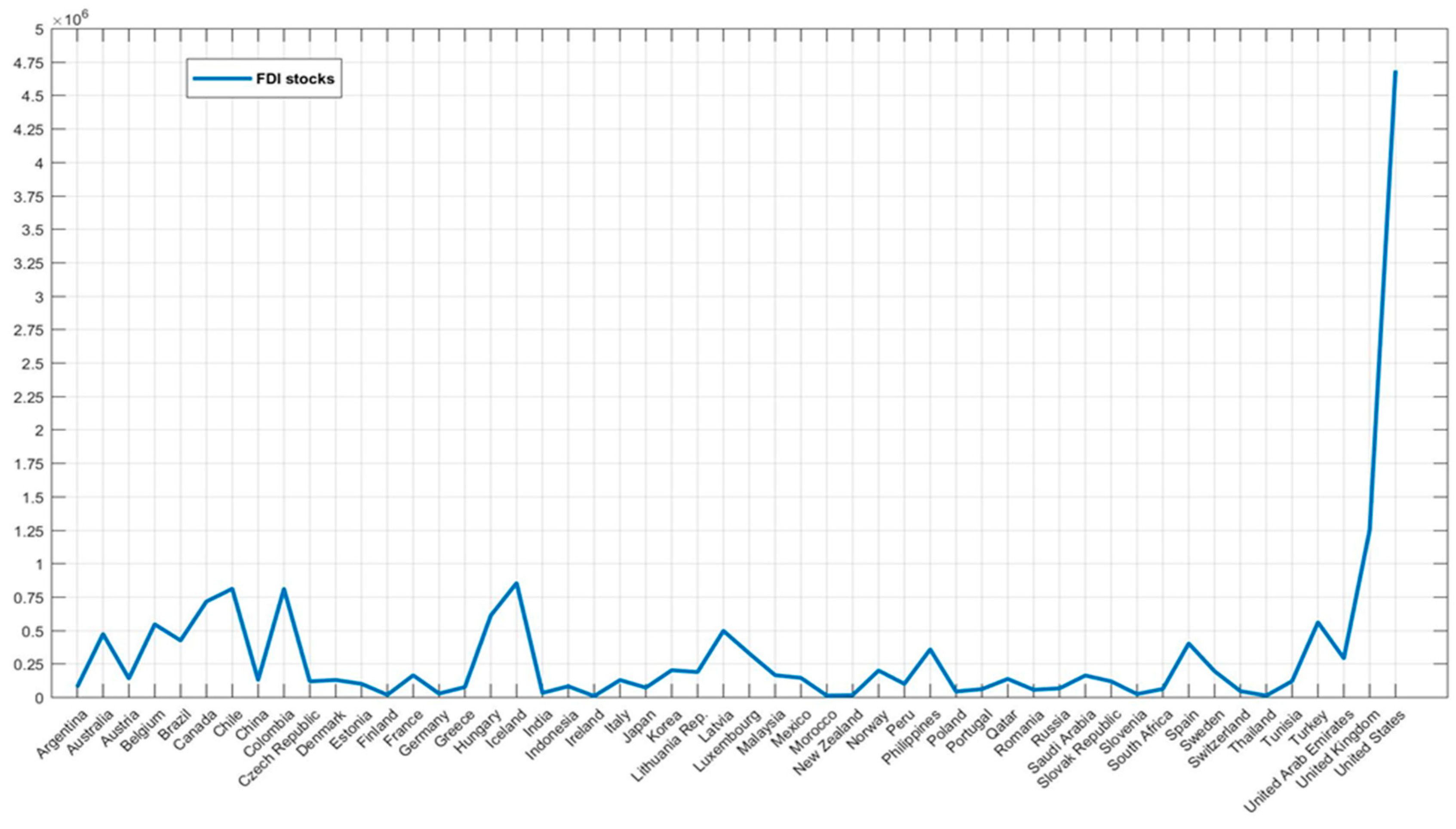

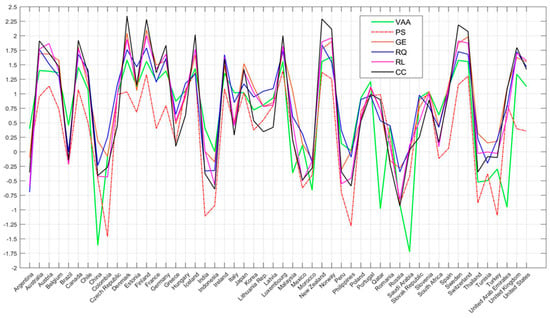

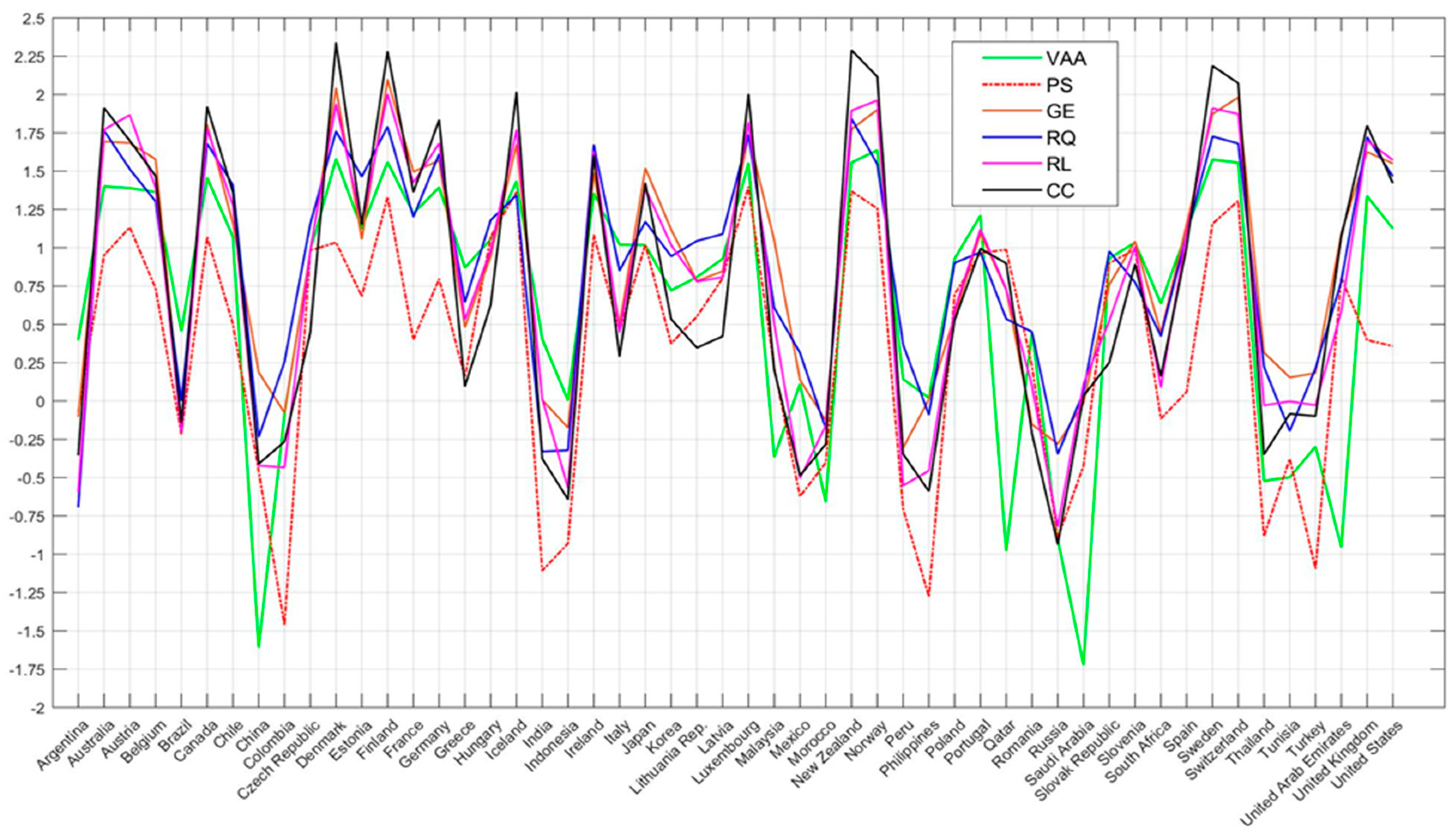

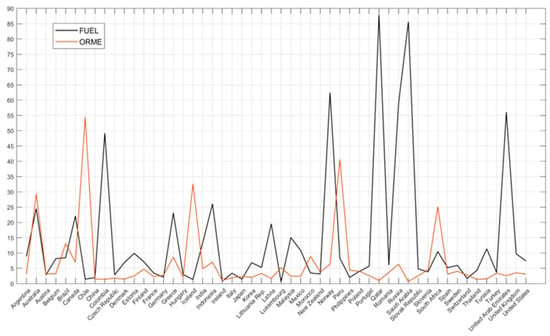

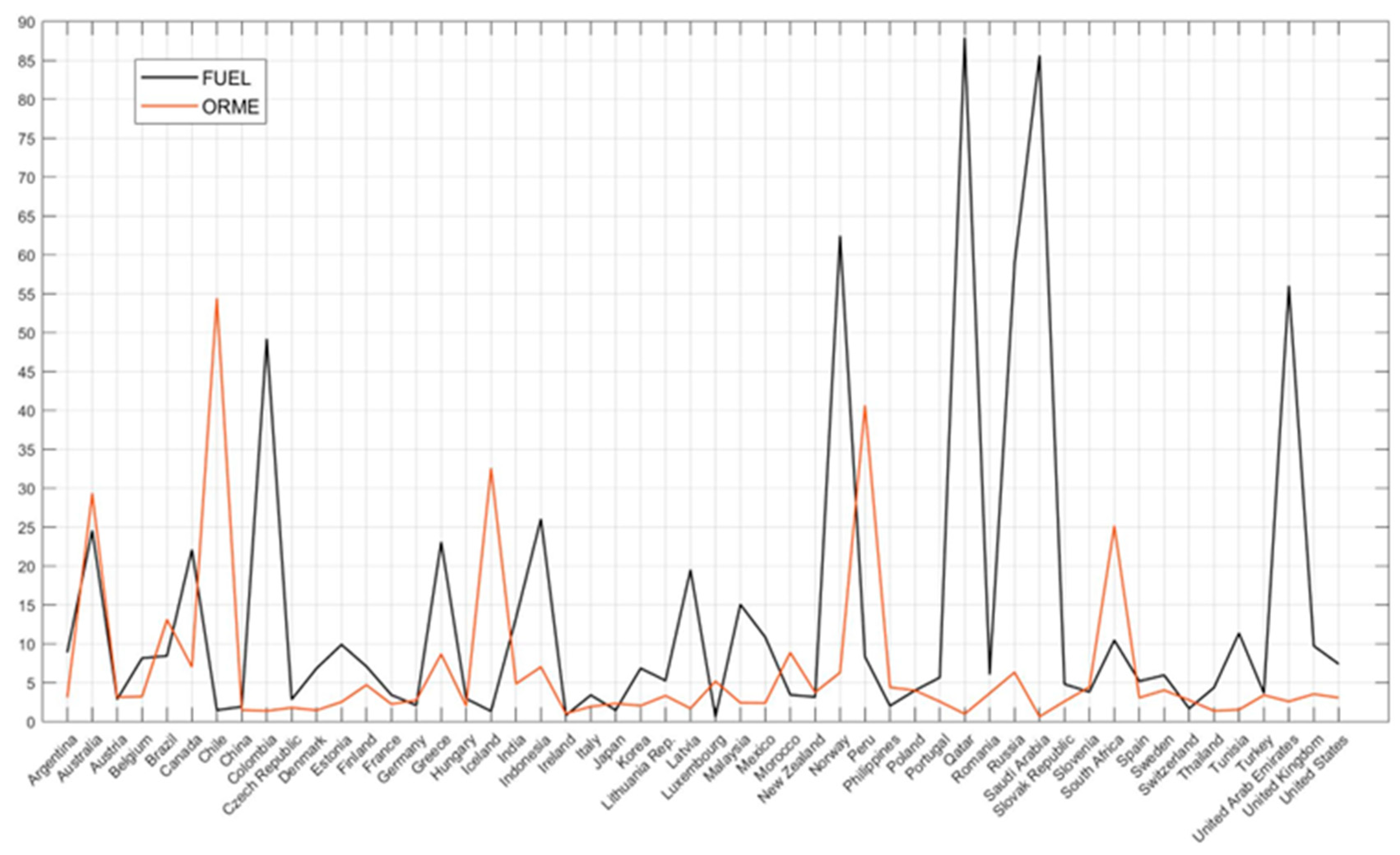

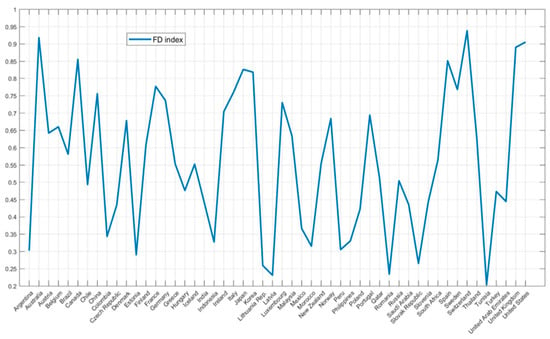

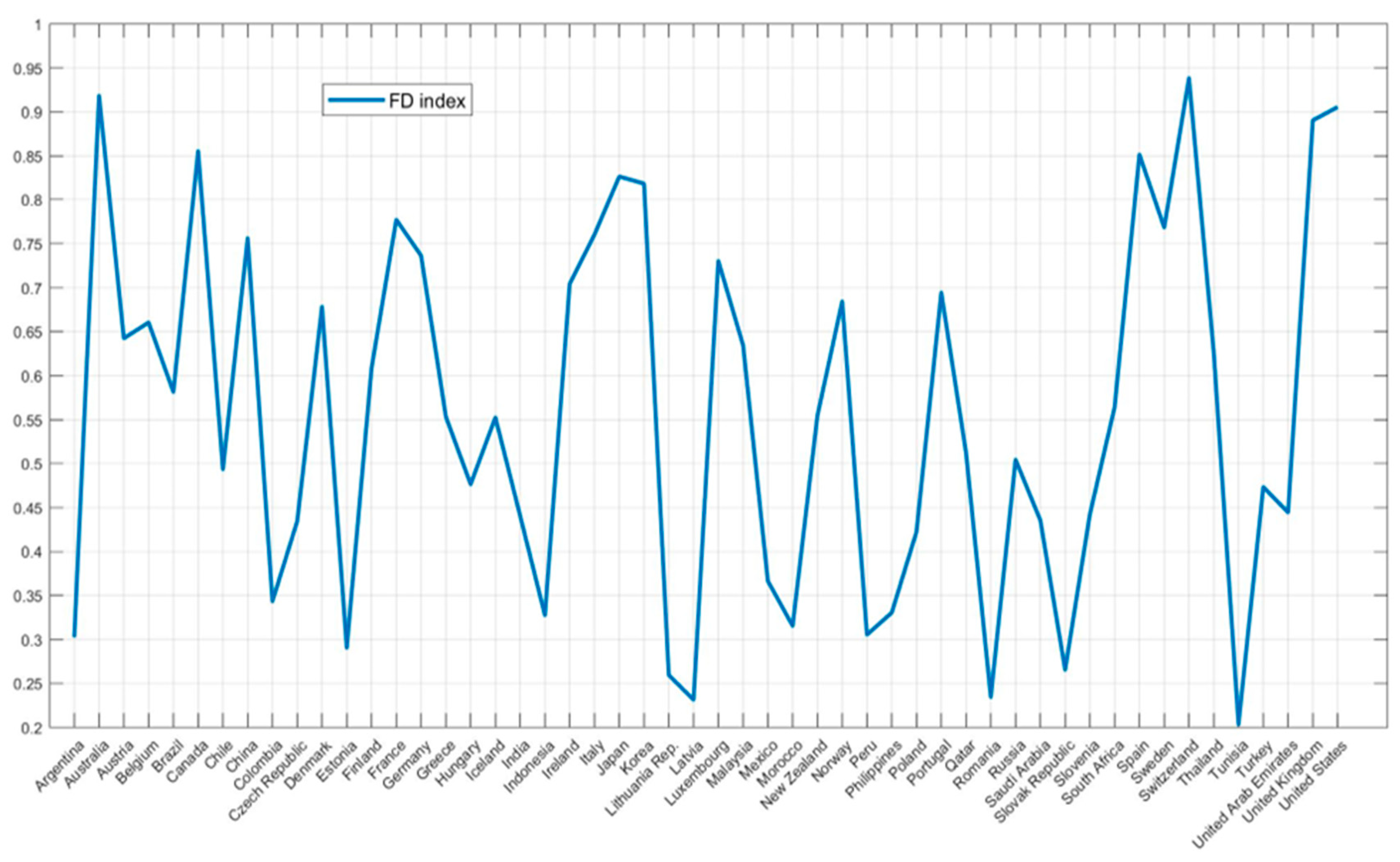

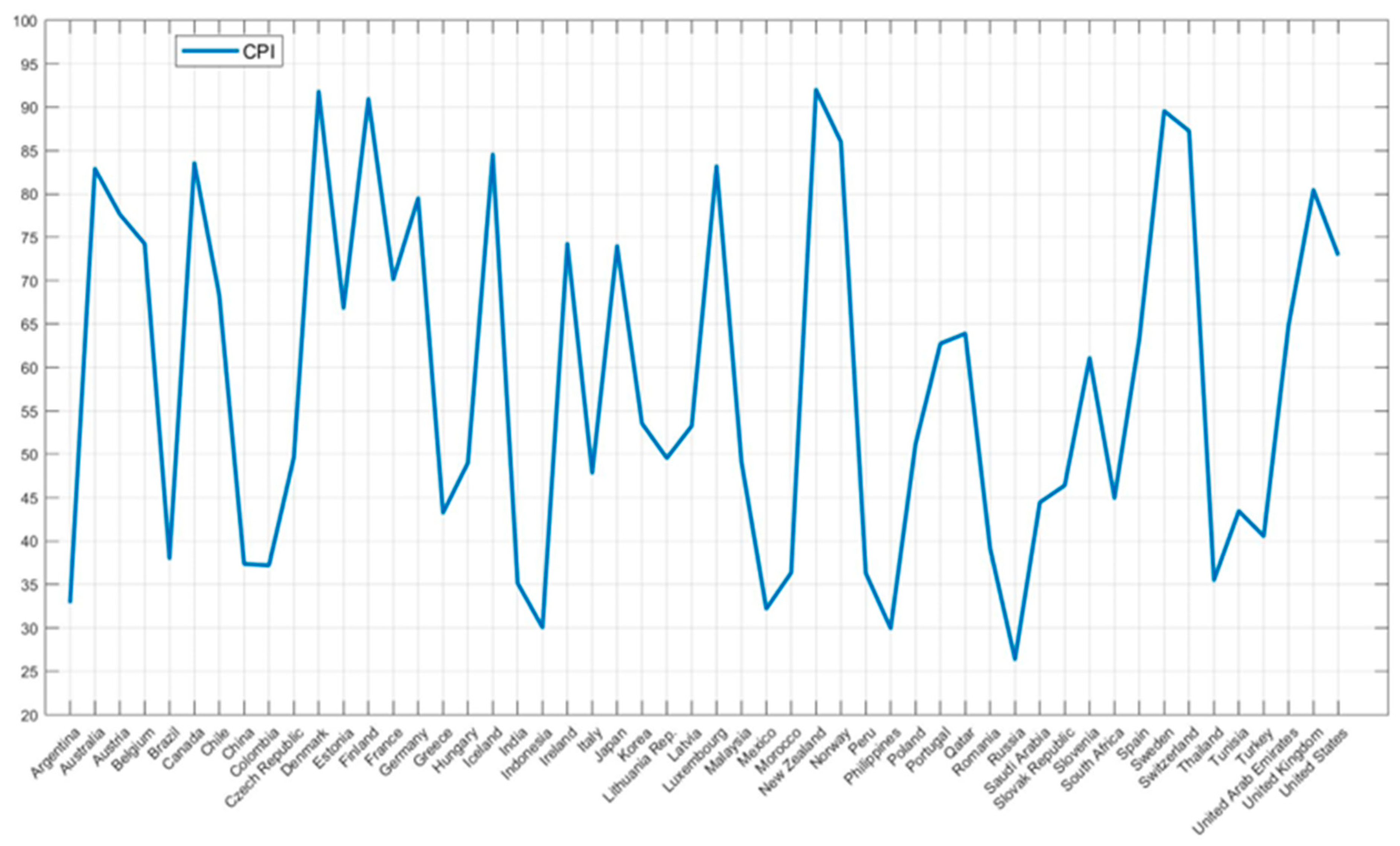

Nevertheless, to distinguish between FDI in a host country with superior or poorer institutions than at home, we consider two additional factors. Positive (negative) institutional distance—an institutional gap between the host and the source countries when the host country’s institutions are better (worse) than that at home. To our knowledge, only two pieces of research have used these measures in different ways [23,38]. In addition to the six institutional indicators, we rely on the corruption perception index (CPI) as an additional measure. The use of this index in empirical analysis is supported by a number of prior researchers [26,34,66,67] who suggest that, even though the CPI has recognized itself as the key variable of corruption in the literature, it actually proves to be much more powerful than corruption control indicator. The CPI data are from Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index database [68]. Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 in Appendix A summarize the variables, definitions, data sources, descriptive statistics, and correlations used in this study. The correlation matrix demonstrates that the institutional indicators are highly correlated, with coefficients ranging from 0.6 to 0.9, as shown in Table A4. As a result, we conducted separate regressions for each institutional indicator to take into account its moderating effects on outward FDI. Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A5 in Appendix B illustrate the average inward FDI stocks, institutional quality indicators, natural resources, financial development index, and corruption perception index quality by country from 2002–2021, respectively.

3.2. The Gravity Model Approach

Various academic papers have acknowledged the gravity model as the main tool for empirical analysis of the bilateral FDI inflows between source and host countries [69,70,71,72,73]. However, the literature has also identified other key factors that could affect the outward FDI, such as institutional quality [18,19,21,22,39,40,41,50], natural resources [14,15,16,17,23,26], and financial development [27,28,29,30,56,74]. Following the literature, to investigate the moderating influence of institutional quality on the financial development–FDI relationship as well as the natural resources–FDI relationship, we estimate the gravity equation in the following functional form:

where i indicates each home country, j indicates each host country, t is the time period, FDI is bilateral FDI stocks from the home country to host country in current US dollars, FDIt−1 is a lagged value of bilateral FDI stocks, RGDP is real GDP per capita in constant prices of the host country, FD is financial development index of the host country, POP is the population size of the host country, LPI is the logistics performance index that measures logistics performance and infrastructural abilities of a host country, NR is natural resources includes fuel, and ore and metal resources of the host country, IQ is institutional quality consists of six governance indicators (VAA, PS, GE, RQ, RL, and CC) of the host country. CPI is the corruption perception index refers to the perceived levels of public sector corruption of the host country, ID is a difference in institutional indicators between the host and source country, and DIST is the geographic distance between the economic centers of the home country and the host country.

However, making interaction terms of the topic variables is a popular method used in the literature to express the moderating effect [8,23,26,56,75]. In this study, we adopt a similar approach and shape an interaction term of financial development (FD), natural resources (FUEL and ORME), and institutional quality (IQ) to convey the moderating effect of IQ on (1) FD–FDI relationship, (2) FUEL–FDI relationship, and (3) ORME–FDI relationship. We also account for the CPI’s moderating effect on those relationships. Thus, our panel gravity equations take the following specification forms:

where ln refers to the log transformation of variables, except for those in ratio forms and is the error term.

In Equation (2), is the interplay between FD and CPI, is the interplay between FD and IQ, and is the interplay between FD and ID. In Equation (3), indicates the interplay between FUEL and CPI, indicates the interplay between FUEL and IQ, and indicates the interplay between FUEL and ID. In Equation (4), denotes the interplay between ORME and CPI, denotes the interplay between ORME and IQ, and denotes the interplay between ORME and ID.

Referring to the Arellano and Bover [76] and Blundell and Bond [77] GMM processes, we estimate Equations (2)–(4) with a two-step system GMM, which helps address the endogeneity and weak instrument issues. The Arellano–Bond test for autocorrelation (AR(2)) is employed to check for the second-order serial correlation in disturbances [78]. The overidentifying restrictions test (Hansen J-test) is used for the instrument validity across models [79]. The system GMM estimations shown in Tables (in Section 4) illustrate that the Hansen and AR(2) tests yield uncorrelated disturbance terms, which thus confirm the validity of our estimated models.

3.3. Robustness Check

In line with earlier studies [19,26,39] that measured ID as the difference between institutions in the host and source countries, we introduce in this work the idea of ID. For a robust check, we follow Aleksynska and Havrylchyk [23] and Le and Kim [38] by disaggregating the ID into negative ID (i.e., institutions in the host countries are poorer than in the home) and positive ID (i.e., institutions in the host countries are better than institutions in the home). This disaggregation is based on the idea that investing in host countries with noticeably superior institutions may be required; therefore, the effects of positive and negative ID are not symmetrical [23]. Therefore, we split the sample into two groups: better institutions and worse institutions. As per Aleksynska and Havrylchyk [23], we assume that the FDI characteristics may differ based on the IQ of the countries. ID, however, might be a disincentive if institutions in the host country are poorer than that at home [23,80].

Using the disaggregated data, we classify the host country as a better group when it has a higher IQ than the home; otherwise, we identify it as a worse group when it has a lower IQ than the home country does. Given the importance of financial sector development and natural resources (fuel, ore, and metal resources) for FDI attractiveness, we investigate the interplay among FD, NR (FUEL and ORME), and ID.

Thus, to test for the moderating influence of positive (negative) ID on the FD–FDI relationship and NR–FDI relationship, we consider the gravity models that take the following form:

where () is the ID between the host and home country, if IQ in the host country is better (worse) than that at source, () is the interplay between positive (negative) ID and FD, () is the interplay between positive (negative) ID and FUEL, () is the interplay between positive (negative) ID and ORME.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. FDI and FD Nexus: The Moderating Effect of IQ

Based on system GMM estimates, our results presented in Table 1 show that FD has a positive and significant impact on G7’s outward FDI in all regression models. This indicates that host countries under study can draw in more inward FDI thanks to efficient and adequately regulated financial systems, improved access to banking services, and well-developed stock markets. It appears that one of the key pillars of FDI in host countries is FD since it can enhance economic development mainly by alleviating financial constraints and providing adequate liquidity, which in turn allows for more efficient resource allocation and increases FDI inflows. This result is consistent with prior studies by Varnamkhasti et al. [28], Desbordes and Wei [29], Donaubauer et al. [30], and Shi and Zhang [74], who suggested that easier access to bank credit expands MNEs’ investment prospects by allowing them to finance their activities with internal resources by borrowing from banks. Similarly, the lagged bilateral FDI coefficient reveals that the host countries’ inward FDI stocks have changed significantly and favorably. This implies that current inward FDI stocks have a significant likelihood of influencing forthcoming inward FDI to host countries.

Table 1.

Impact of FD on G7’s outward FDI—the moderating effect of IQ: System GMM estimation.

Table 1 presents the results of the interaction between FD and IQ on G7’s outward FDI. We find that the coefficients of the interaction terms among each indicator of IQ and FD are positive and highly significant, indicating the importance of IQ’s moderating effect on the relationship between FD and FDI. This suggests that improving IQ generally is an incentive for FDI outflows from the G7 countries. This finding is consistent with that of Islam et al. [56] and Irandoust [57], who suggested that if a host country has a sound financial system with strong investor protection, improved institutional structures, and excellent regulatory quality and policies, it may become more attractive to FDI flows.

Regarding ID, our empirical evidence shows that its coefficient is positive and statistically significant, revealing that a 1% increase in ID is associated with a 7.348% rise in G7’s outward FDI. This implies that there will be more outward FDI movements abroad the greater economic ID there is between the host and home country [42,44]. As further evidence, the interplay between FD and ID has a positive and significant impact on G7’s outward FDI, indicating that when these two factors interact, it significantly contributes to the explanation of the G7’s outward FDI towards host countries. This implies that the interaction of a healthy financial system, which is characterized by lower asymmetric information and transaction costs (especially those related to contract enforcement), with better institutional differences of GE, RQ, RL, and CC between source and host countries have profound effects on the outward FDI.

Concerning the control variables, we discover that GDP per capita has a positive and substantial effect on the G7’s outward FDI in all models, indicating that a greater market size plays a significant role in receiving foreign investments. This result is consistent with previous research [23,40,81], which suggests that a larger market size offers more chances for selling products and services to a new market in order to optimize the impact of economies of scale. The POP coefficient is positive and statistically significant at a 1% level of significance in all regression models, implying that FDI flows increase as the size of the host countries’ markets. This finding further suggests that the G7’s outward FDI is encouraged by the comparative advantages of “large scale and low cost” in the labor force of host countries. In addition, it is asserted that the more population a host country has, the more expected it is that foreign firms will find a market for their products there [26,40,56,61]. Bilateral DIST cost has a significant and negative impact on the G7’s outward FDI, which indicates that a reduction in transportation or geographical distance costs causes a significant rise in the G7’s outward FDI. This result is consistent with earlier research [23,38,40]. The results also show that the LPI has a favorable and significant impact on the G7’s outward FDI, indicating that better logistics performance and well-developed transport-related infrastructure in the host countries (better ports, railroads, and information technology) could maximize profitability and cost-effective working hours for conducting business activities.

4.2. FDI and NR Nexus: The Moderating Effect of IQ

Table 2 displays the system GMM estimates coefficients for NR interactions with IQ and ID on the G7’s outward FDI. NR interactions include fuel, ore, and metal resources. According to our empirical findings, FDI is positively and significantly impacted by the lagged value of FDI in all regression models. This indicates that substantially more inward FDI stocks can be attracted using the existing bilateral FDI. This finding is in line with recent investigations [26,40]. The results show that when individual IQ indicators, such as VAA, PS, GE, RQ, RL, and CC, are considered, the FUEL–FDI and ORME–FDI coefficients have significant positive effects on the G7’s outward FDI in all regression models. This indicates that an increase in the lack of VAA, PS, GE, and RQ, which serve to explain how a country’s economy and government pragmatically determine whether or not it is practicable, as well as a rigorous RL in host countries boost the outward FDI from G7 countries to host countries. This result agrees with prior research [26,40,41,47,49,50,64,82].

Table 2.

Impact of NR (fuel, ore, and metal) on the G7’s outward FDI—the moderating effect of IQ: System GMM estimation.

Similarly, the CPI has a significant positive impact on G7’s outward FDI, suggesting that host countries would obtain more FDI from the G7 countries as perceived levels of public sector corruption decline. This result is consistent with Muhammad and Khan [26]. We also discover a significant positive sign for ID between host countries and G7 countries, revealing that as ID between the host and source countries grows, more FDI from source countries flows into host countries. This result corroborates the findings of Aleksynska and Havrylchyk [23], Heavilin and Songur [17], and Muhammad and Khan [26].

Regarding the interaction of NR with institutional factors (IQ and ID), we find that the interplay between FUEL resources, ORME resources, and each IQ indicator yields significant and negative coefficients (see Table 2). This indicates that a decrease in IQ—lack of VAA, PS, GE, RQ, as well as weak RL—in host countries decreases the G7’s outward FDI. The substantial negative association between IQ indicators’ interaction with FUEL resources and ORME resources indicates that NR—FUEL and ORME—play an important role in FDI, while joint policies for IQ and NR considerably decrease the outward FDI from G7 countries to host countries. Therefore, host countries should implement effective individual policies and laws that enhance FDI inflows to improve the quality of their institutions.

The results also show strong and adverse connections between FUEL resources and CPI (FUEL × CPI) and ORME resources and CPI (ORME × CPI). This indicates that when NR (FUEL and ORME resources) interacts with CPI, the G7’s outward FDI stocks increase toward host countries as corruption increases. Likewise, the interactions of FUEL resources with ID (FUEL × ID) and ORME resources with ID (ORME × ID) both have significant negative coefficients. It follows that an increase in the outward FDI from G7 countries to host countries would occur if ID between the source and host countries decreased. This result agrees with earlier research [16,23,26]. Moreover, the system GMM estimates show that the coefficients of GDP per capita, POP, LPI, as well as NR—FUEL and ORME—have positive and significant effects on the G7’s outward FDI when regressed with each IQ indicator in all regression models. This implies that host countries with abundant natural resources, higher income levels, advanced logistics infrastructure, and low labor costs attract and handle more FDI, which are all pulling factors for foreign investments [40,65]. In contrast, DIST exhibits a significant negative impact on FDI flows, indicating that G7 firms prefer to direct their investments to locations that are geographically close to their home countries. This result is consistent with earlier findings [23,40,73].

4.3. Robustness Checks

As discussed in the methodology section, to check the strength of our empirical analysis, this study adopts the approach used by Aleksynska and Havrylchyk [23] and Le and Kim [38] by categorizing ID into positive ID (institutions in the host country are better than those in the home) and a negative ID (institutions in the host country are worse than those in the home). In doing so, we split the whole panel into two groups: a better institution and a worse institution. The system GMM estimate results shown in Table 3 indicate that the lagged value of bilateral FDI stocks has a significant and positive impact on the G7’s outward FDI to host countries. The coefficients of FD, FUEL, and ORME are significantly positive in host countries with better IQ, especially higher PS, GE, RQ, and RL. The value of these coefficients reveals an adverse and substantial effect on the G7’s outward FDI to host countries with a worse IQ. However, the significant positive coefficients on an ID that interacted with FD (NegID × FD), FUEL resources (NegID × FUEL), and ORME resources (NegID × ORME) have confirmed that the NegID effect has been significantly reduced in host countries with abundant natural resources and well-developed financial systems.

Table 3.

Impact of FD and NR (Fuel, ore, and metal) on the G7’s outward FDI—the moderating effect of ID: System GMM estimation.

The appeal of FD and NR seems to outweigh the drawbacks of ID. We can infer that foreign companies have the incentive to invest in a host country despite its low IQ when it has substantial natural resource wealth and a sound financial system. Aleksynska and Havrylchyk [23] also share this view, claiming that foreign investors do not seem to worry about the quality of institutions when investing abroad rather than at home. But this runs counter to the claims made by Wang [16], Muhammad and Khan [26], and Le and Kim [38] that higher IQ in the host country attracts more FDI from the home country.

Furthermore, it has been discovered that GDP per capita and POP size have significant positive effects on the G7’s outward FDI in both groups with better and worse institutions. This means that investors from G7 countries disregard the institutional environment and do not care about IQ when they invest in host countries with poorer institutions. In contrast, in the group with worse institutions, the LPI proves to be significantly negative, whereas it shows a positive and significant determinant of the outward FDI when the host country’s institutions are better. In both a better and a weak institutional environment, the bilateral DIST cost has a significant negative effect on the outward FDI of G7 countries.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Even though there are existing growing studies looking at FDI’s drivers, other factors, including a country’s NR, IQ, ID, and FD, continue to have greater impacts on how appealing a country is to FDI. By using a gravity model approach based on system GMM estimators, we contribute to the literature by examining the moderating effects of both IQ and ID in the FD–FDI and NR–FDI relationships, individually and in terms of interaction, and discussing their significant implications on the G7’s FDI outflows to 45 host countries over the 2002–2021 period. Our empirical findings reveal that each of the considered IQ factors has a positive and significant impact on the G7’s outward FDI. Besides, all IQ factors that interact with FD have been shown to have a favorable and significant impact on the G7’s outward FDI. Focusing on ID, our robustness analysis shows that the impact of ID varies depending on whether host countries have superior or poorer institutions. However, we discover that ID might be viewed as a motivating factor if investors from the G7 countries invest in host countries with improved institutions. This is most likely a result of the “asset-seeking” nature of FDI, in which new investors purchase innovative technologies, trademarks, and intellectual property, which are more likely to be found in favorable institutional environments characterized by political stability, strong property rights, and low levels of corruption. In contrast, we find that investors from the G7 countries are discouraged not just by the poor institutions in the host countries but also by the ID between them and the host countries since they choose to invest in countries with an institutional environment fairly similar to their own. However, we discover that in the unlikely event that the host countries have abundant NR and well-established financial systems, which are important drivers of the G7’s outward FDI, the negative effect of ID can be mitigated. Moreover, it shows a significant positive connection between per capita GDP, POP size, as well as the logistics infrastructure, and G7’s outward FDI, indicating that countries with higher income levels, low labor costs, and advanced technological infrastructure receive and host more FDI.

This study provides some policy implications. First, financial institutions’ development with good governance in host countries should be ensured and open the scope for foreign investment, which would eventually motivate investors to increase their capital investments in these countries. More specifically, access to financial resources should be a top priority for host governments, and this should be supported by measures that improve the effectiveness and investor-friendliness of their stock markets. Second, to grant foreign investors access to all areas of their economies, host governments should reduce their institutional and legislative barriers and improve their business environments by streamlining the investment process by eliminating pointless procedures, resolving the issue of inadequate synchronization between the different countries, developing updating laws and legislation to effectively protect investors’ rights and minimize their risk, and increasing transparency of the investment process. An incentive package, including tax and non-tax subsidies, is a policy to allow foreign investment and encourage businesses to establish a base in the host country. Third, FDI has channelized technical know-how in the economy, thus promoting human capital development by providing technical expertise and supplying skilled human resources. Therefore, it is essential to have effective institutional development and sound governance practices for fostering the persistent inflows of FDI into the host economies. Fourth, generally, numerous host countries have abundant natural resources and good governance, which are basic requirements for FDI. However, it seems that joint policies for both natural resources—fuel resources and Ores and metals resources—and institutions weaken FDI flows. Accordingly, host governments should make separate policies for institutions and natural resources to prevent this and boost their economic advantages. Fifth, strengthening the financial system and increasing bilateral FDI stocks may be accomplished through a combination of factors, including macroeconomic policies, financial conditions, and technological innovations. Finally, it is advised that policymakers in host countries should improve the quality of their logistics infrastructure, such as ports, railroads, and information technology, to more actively support FDI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.B. and M.Y.; methodology, M.Y. and M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.Y.; formal analysis, M.Y. and M.B.; investigation, R.K.; resources, M.B. and A.A.; data curation, M.B. and M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y. and S.B.B.; writing—review and editing, M.Y. and S.B.B.; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, S.B.B.; project administration, S.B.B.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Program of Research Project Funding After Publication, grant No. (43-PRFA-P-75).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Program of Research Project Funding After Publication, grant No. (43-PRFA-P-75).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of countries.

Table A1.

List of countries.

| Source Countries (G7): Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. |

| Host Countries: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Korea, Rep., Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. |

Table A2.

Variable description and data sources.

Table A2.

Variable description and data sources.

| Variables | Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| FDI | Outward FDI stocks from source country to host country (current USD, millions). | [58] |

| RGDPpc | Real GDP per capita (constant 2010 USD) to account for the host country’s market-seeking motives. | [62] |

| DIST | Geographic distance (air distance between capital cities, expressed in kilometers) between the host and the origin country (air distance between capital cities, expressed in kilometers). | Author |

| POP | Population density of the host country (people per sq. km of land area). | [62] |

| LPI | Logistics Performance Index that measures the logistics performance and infrastructural abilities of a country. LPI combines data on six key performance indicators—Infrastructure, Customs, Quality of logistics services, Tracking and tracing, Timeliness, and Ease of arranging shipments—into a single aggregated measure. The LPI varies from 1 to 5. A higher value indicates stronger logistics performance. | [62] |

| FD | Financial Development Index is a relative ranking of a country on the depth, access, and efficiency of its Financial Institutions (banking and non-banking sectors) and Financial Markets (stock market). The Financial Institutions Index and the Financial Market Index are combined to create a Financial Development Index. Depth, access, and efficiency are the three dimensions into which each of the sub-indices is separated. Three dimensions—depth, access, and efficiency—are used to further divide each of the sub-indices. | [37] |

| FUEL | Fuel exports (% of merchandise exports) by the host country. | [62] |

| ORME | Ores and metals exports (% of merchandise exports) by the host country. | [62] |

| CPI | The corruption perception index refers to the perception of corruption in the public sector in the host country. A scale from 0 to 100 is used for the index. A lower score denotes a significant level of corruption, whereas a higher score denotes an exceptionally higher level of cleanliness. | [68] |

| Institutional Quality Indicators (IQ): | ||

| VAA | Voice and accountability are used to gauge how much a country’s population can influence the choice of their government, along with the capacity for expression, association, and free media. | [63] |

| PS | Political stability and lack of violence capture the ability for perceptions of the government’s power to potentially cause political instability and politically inspire violence and terrorism. | [63] |

| GE | Government’s effectiveness in reaching high standards of public service, the excellence of the civil service, and the degree of political independence it has, as well as the legitimacy of the government’s adherence to these principles. | [63] |

| RQ | Regulation quality measures how well the public believes the government can create and implement sensible economic policies and rules that encourage and enable private sector improvement. | [63] |

| RL | Rule of law to assess the quality and fair-mindedness of the lawful framework securing the rights of property and persons. | [63] |

| CC | Control over the corruption that results in bribes, excessive support, and favoritism | [63] |

| ID | Difference between the host and source country in terms of institutional indicators (VAA, PS, GE, RQ, RL, and CC). | [63] |

| PosID (NegID) | There will be a positive (negative) institutional difference equal to the difference in institutions between institutional measures if the quality of institutions in the host country is better (poorer) than that in the country of origin. | [63] |

Table A3.

Descriptive statistics.

Table A3.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variables | FDI | RGDPpc | POP | LPI | FD | FUEL | ORME | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Argentina | 75,115.61 | 14,505.14 | 12,516.89 | 1505.879 | 15.214 | 0.931 | 2.824 | 0.055 | 0.302 | 0.023 | 8.846 | 5.678 | 3.054 | 1.234 |

| Australia | 471,774.3 | 203,969.4 | 54,284.16 | 3645.21 | 2.945 | 0.263 | 3.836 | 0.105 | 0.918 | 0.023 | 24.524 | 4.531 | 29.309 | 6.729 |

| Austria | 139,426.5 | 52,780.39 | 43,557.86 | 1949.084 | 102.855 | 3.430 | 3.918 | 0.178 | 0.642 | 0.046 | 2.815 | 0.952 | 3.105 | 0.445 |

| Belgium | 544,264.5 | 102,168.5 | 40,036.02 | 1822.985 | 362.825 | 13.949 | 4.045 | 0.048 | 0.660 | 0.036 | 8.108 | 2.774 | 3.178 | 0.719 |

| Brazil | 423,669.3 | 227,108.7 | 8261.185 | 731.655 | 23.675 | 1.277 | 2.995 | 0.101 | 0.581 | 0.073 | 8.408 | 2.792 | 13.057 | 3.365 |

| Canada | 714,837 | 476,925.7 | 41,534.21 | 2903.824 | 3.861 | 0.243 | 3.999 | 0.096 | 0.855 | 0.069 | 22.062 | 4.589 | 6.976 | 1.382 |

| Chile | 810,114.2 | 262,250.9 | 12,090.42 | 1675.855 | 23.395 | 1.517 | 3.023 | 0.141 | 0.493 | 0.029 | 1.428 | 0.727 | 54.377 | 7.038 |

| China | 128,796.1 | 52,108.54 | 6482.795 | 2742.747 | 143.364 | 4.634 | 3.585 | 0.171 | 0.756 | 0.025 | 1.871 | 0.516 | 1.450 | 0.302 |

| Colombia | 809,272.45 | 579,051.34 | 5402.441 | 822.740 | 41.469 | 2.865 | 2.525 | 0.126 | 0.343 | 0.041 | 49.155 | 11.224 | 1.332 | 0.443 |

| Czech Republic | 117,771.5 | 86,307.45 | 16,922.46 | 2041.219 | 135.368 | 2.320 | 3.215 | 0.158 | 0.434 | 0.042 | 2.797 | 0.775 | 1.741 | 0.338 |

| Denmark | 128,241.8 | 32,001.88 | 53,213.41 | 2621.469 | 136.023 | 7.728 | 3.905 | 0.102 | 0.678 | 0.034 | 6.800 | 2.378 | 1.411 | 0.193 |

| Estonia | 99,361.57 | 18,547.93 | 16,594.57 | 2684.288 | 31.141 | 0.772 | 2.993 | 0.210 | 0.290 | 0.021 | 9.843 | 4.565 | 2.478 | 0.542 |

| Finland | 16,940.25 | 7843.731 | 43,751.45 | 2020.762 | 17.719 | 0.401 | 3.931 | 0.174 | 0.608 | 0.047 | 7.048 | 2.613 | 4.663 | 1.134 |

| France | 163,189.9 | 74,793.04 | 36,269.79 | 1287.159 | 119.109 | 3.317 | 3.966 | 0.054 | 0.777 | 0.041 | 3.389 | 0.871 | 2.210 | 0.334 |

| Germany | 26,428.97 | 7300.364 | 39,161.03 | 2951.752 | 235.261 | 2.394 | 4.322 | 0.069 | 0.736 | 0.022 | 2.044 | 0.356 | 2.702 | 0.355 |

| Greece | 75,293.35 | 20,600.4 | 20,138.14 | 2274.916 | 84.688 | 1.169 | 3.075 | 0.146 | 0.553 | 0.064 | 23.033 | 11.410 | 8.639 | 0.946 |

| Hungary | 609,876.7 | 206,901.1 | 12,290.08 | 1572.764 | 109.836 | 2.427 | 3.203 | 0.131 | 0.476 | 0.053 | 2.894 | 1.457 | 1.991 | 1.684 |

| Iceland | 852,789.7 | 177,809.7 | 51,335.74 | 4158.117 | 3.231 | 0.242 | 3.041 | 0.523 | 0.552 | 0.045 | 1.302 | 0.628 | 32.526 | 8.939 |

| India | 31,258.32 | 10,228.36 | 1372.147 | 394.244 | 421.126 | 31.420 | 2.967 | 0.145 | 0.440 | 0.029 | 13.275 | 4.922 | 4.824 | 1.803 |

| Indonesia | 81,201.8 | 24,893.9 | 2929.261 | 650.208 | 134.729 | 8.485 | 2.706 | 0.135 | 0.327 | 0.033 | 26.006 | 4.637 | 6.974 | 1.779 |

| Ireland | 7701.36 | 4101.594 | 56,246.2 | 13,420.47 | 66.016 | 4.701 | 3.642 | 0.180 | 0.704 | 0.042 | 0.766 | 0.370 | 0.999 | 0.263 |

| Italy | 127,703.1 | 63,751.038 | 31,887.37 | 1356.581 | 200.830 | 3.866 | 3.731 | 0.181 | 0.760 | 0.017 | 3.359 | 0.963 | 1.886 | 0.333 |

| Japan | 71,061.59 | 46,718.95 | 33,889.34 | 1438.491 | 349.45 | 1.784 | 4.151 | 0.042 | 0.826 | 0.055 | 1.424 | 0.692 | 2.282 | 0.531 |

| Korea, Rep. | 201,028.6 | 144,154.3 | 26,113.89 | 4309.333 | 513.637 | 13.387 | 3.684 | 0.117 | 0.818 | 0.022 | 6.803 | 2.020 | 2.004 | 0.368 |

| Latvia | 187,464.5 | 80,901.0 | 12,641.6 | 2442.288 | 33.411 | 2.262 | 2.870 | 0.229 | 0.259 | 0.034 | 5.227 | 2.356 | 3.282 | 1.139 |

| Lithuania | 495,557.5 | 403,750.5 | 12,840.36 | 3101.899 | 48.841 | 3.596 | 2.856 | 0.384 | 0.231 | 0.033 | 19.462 | 5.411 | 1.645 | 0.290 |

| Luxembourg | 326,633.9 | 98,511.17 | 105,376 | 4066.354 | 219.371 | 26.242 | 3.936 | 0.153 | 0.730 | 0.010 | 0.560 | 0.359 | 5.137 | 0.763 |

| Malaysia | 164,136.4 | 57,156.39 | 8906.82 | 1565.765 | 87.296 | 8.080 | 3.421 | 0.112 | 0.634 | 0.046 | 15.007 | 3.845 | 2.379 | 1.203 |

| Mexico | 143,952.1 | 65,499.48 | 9202.626 | 430.281 | 59.787 | 4.670 | 2.916 | 0.106 | 0.366 | 0.035 | 10.797 | 4.341 | 2.346 | 0.742 |

| Morocco | 11,420.93 | 5644.107 | 2571.009 | 365.448 | 74.349 | 5.639 | 1.892 | 0.786 | 0.315 | 0.033 | 3.399 | 1.803 | 8.827 | 2.594 |

| New Zealand | 14,579.68 | 6692.143 | 36,999.27 | 2439.601 | 16.995 | 1.355 | 3.610 | 0.149 | 0.554 | 0.036 | 3.115 | 1.694 | 3.720 | 0.799 |

| Norway | 199,052.9 | 228,200.6 | 73,714.13 | 2146.713 | 13.624 | 0.825 | 3.986 | 0.161 | 0.684 | 0.057 | 62.407 | 5.534 | 6.266 | 0.915 |

| Peru | 99,106.85 | 46,633.99 | 5287.292 | 1118.532 | 23.245 | 1.494 | 2.615 | 0.131 | 0.305 | 0.062 | 8.285 | 2.325 | 40.598 | 5.265 |

| Philippines | 357,259.7 | 131,125.0 | 2670.474 | 571.166 | 323.397 | 31.093 | 2.585 | 0.147 | 0.330 | 0.024 | 1.979 | 0.813 | 4.360 | 1.623 |

| Poland | 42,010.7 | 18,364.98 | 11,397.89 | 2451.022 | 124.264 | 0.349 | 3.035 | 0.156 | 0.422 | 0.056 | 3.953 | 1.189 | 3.965 | 0.652 |

| Portugal | 59,843.79 | 18,718.15 | 19,634.08 | 811.648 | 113.976 | 1.218 | 3.240 | 0.108 | 0.694 | 0.041 | 5.613 | 2.326 | 2.532 | 0.683 |

| Qatar | 135,877.2 | 53,005.28 | 60,550.18 | 2603.435 | 166.909 | 72.057 | 3.142 | 0.361 | 0.512 | 0.040 | 87.911 | 4.568 | 0.941 | 1.074 |

| Romania | 55,127.97 | 37,368.4 | 8340.29 | 1896.512 | 88.192 | 3.577 | 2.638 | 0.232 | 0.234 | 0.071 | 6.010 | 2.180 | 3.598 | 1.118 |

| Russia | 65,420.54 | 24,152.47 | 8737.696 | 1234.445 | 8.776 | 0.045 | 2.463 | 0.150 | 0.504 | 0.035 | 58.917 | 8.287 | 6.288 | 1.240 |

| Saudi Arabia | 161,839.8 | 68,115.73 | 19,135.11 | 1163.03 | 13.365 | 2.059 | 3.201 | 0.106 | 0.435 | 0.056 | 85.588 | 6.239 | 0.597 | 0.577 |

| Slovak Republic | 117,781.2 | 38,875.06 | 14,635.21 | 2634.795 | 112.434 | 0.666 | 3.028 | 0.168 | 0.265 | 0.023 | 4.762 | 1.342 | 2.557 | 0.547 |

| Slovenia | 22,762.67 | 13,268.53 | 20,976.53 | 1970.58 | 101.586 | 1.763 | 3.114 | 0.225 | 0.442 | 0.072 | 3.770 | 1.894 | 4.407 | 0.589 |

| South Africa | 61,416.75 | 31,227.11 | 5944.994 | 367.839 | 43.463 | 3.677 | 3.475 | 0.185 | 0.564 | 0.059 | 10.411 | 0.999 | 25.106 | 4.622 |

| Spain | 401,199.8 | 83,584.44 | 26,013.57 | 1066.742 | 91.439 | 3.513 | 3.684 | 0.109 | 0.851 | 0.028 | 5.148 | 1.523 | 3.026 | 0.632 |

| Sweden | 193,825.8 | 50,542.91 | 49,076.83 | 3305.452 | 23.400 | 1.296 | 4.135 | 0.082 | 0.768 | 0.039 | 5.922 | 1.781 | 3.988 | 0.948 |

| Switzerland | 44,617.93 | 16,280.22 | 82,299.52 | 4542.199 | 201.712 | 12.004 | 4.096 | 0.069 | 0.938 | 0.061 | 1.647 | 0.861 | 2.710 | 0.830 |

| Thailand | 11,399.44 | 4619.855 | 5326.683 | 850.634 | 132.049 | 3.609 | 3.179 | 0.087 | 0.626 | 0.086 | 4.321 | 1.288 | 1.334 | 0.240 |

| Tunisia | 119,738.2 | 42,027.12 | 3792.683 | 368.137 | 69.697 | 4.210 | 2.532 | 0.238 | 0.203 | 0.030 | 11.324 | 4.038 | 1.491 | 0.227 |

| Turkey | 559,340.3 | 174,174.9 | 9621.728 | 2032.104 | 97.087 | 8.398 | 3.310 | 0.244 | 0.473 | 0.054 | 3.610 | 1.313 | 3.353 | 0.773 |

| UAE | 290,187.3 | 94,740.42 | 42,429.53 | 8706.398 | 108.961 | 32.373 | 3.865 | 0.116 | 0.444 | 0.080 | 55.989 | 14.498 | 2.544 | 1.671 |

| UK | 1,249,089 | 529,530.1 | 44,067.8 | 1982.593 | 262.184 | 10.940 | 4.052 | 0.093 | 0.890 | 0.026 | 9.683 | 2.161 | 3.490 | 0.989 |

| US | 4,685,226.25 | 2,510,780.41 | 55,013.56 | 3387.293 | 34.056 | 1.567 | 4.130 | 0.040 | 0.905 | 0.010 | 7.358 | 4.090 | 3.027 | 0.659 |

| Full Sample | 23,3219.7 | 307,138 | 27,360.21 | 23,255.94 | 114.839 | 113.469 | 3.357 | 0.586 | 0.559 | 0.211 | 14.237 | 20.943 | 6.672 | 10.703 |

| Variables | CPI | VAA | PS | GE | RQ | RL | CC | |||||||

| Country | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Argentina | 32.8 | 5.699 | 0.394 | 0.106 | −0.075 | 0.258 | −0.107 | 0.132 | −0.697 | 0.218 | −0.599 | 0.179 | −0.358 | 0.142 |

| Australia | 82.85 | 4.997 | 1.398 | 0.064 | 0.949 | 0.084 | 1.691 | 0.119 | 1.763 | 0.124 | 1.769 | 0.063 | 1.910 | 0.114 |

| Austria | 77.6 | 4.849 | 1.387 | 0.043 | 1.131 | 0.168 | 1.681 | 0.165 | 1.510 | 0.087 | 1.864 | 0.051 | 1.696 | 0.219 |

| Belgium | 74.2 | 1.989 | 1.362 | 0.046 | 0.733 | 0.219 | 1.575 | 0.249 | 1.300 | 0.061 | 1.388 | 0.075 | 1.466 | 0.080 |

| Brazil | 37.95 | 2.723 | 0.453 | 0.082 | −0.219 | 0.251 | −0.143 | 0.156 | −0.002 | 0.173 | −0.202 | 0.139 | −0.147 | 0.203 |

| Canada | 83.5 | 4.211 | 1.455 | 0.071 | 1.068 | 0.117 | 1.804 | 0.085 | 1.678 | 0.092 | 1.771 | 0.063 | 1.918 | 0.115 |

| Chile | 68.3 | 8.304 | 1.069 | 0.078 | 0.499 | 0.252 | 1.155 | 0.103 | 1.407 | 0.116 | 1.273 | 0.113 | 1.356 | 0.179 |

| China | 37.3 | 3.404 | −1.611 | 0.087 | −0.461 | 0.124 | 0.185 | 0.229 | −0.238 | 0.092 | −0.424 | 0.145 | −0.412 | 0.148 |

| Colombia | 37.15 | 1.461 | −0.093 | 0.191 | −1.463 | 0.535 | −0.079 | 0.123 | 0.253 | 0.178 | −0.436 | 0.148 | −0.268 | 0.092 |

| Czech Republic | 49.55 | 6.194 | 0.974 | 0.068 | 0.980 | 0.099 | 0.966 | 0.069 | 1.153 | 0.101 | 0.982 | 0.105 | 0.444 | 0.102 |

| Denmark | 91.75 | 2.844 | 1.578 | 0.083 | 1.032 | 0.150 | 2.042 | 0.184 | 1.759 | 0.111 | 1.936 | 0.071 | 2.338 | 0.096 |

| Estonia | 66.8 | 5.559 | 1.122 | 0.059 | 0.681 | 0.101 | 1.053 | 0.130 | 1.461 | 0.139 | 1.158 | 0.165 | 1.148 | 0.231 |

| Finland | 90.9 | 4.216 | 1.557 | 0.079 | 1.330 | 0.277 | 2.097 | 0.124 | 1.788 | 0.102 | 2.001 | 0.065 | 2.280 | 0.106 |

| France | 70.1 | 2.490 | 1.221 | 0.107 | 0.399 | 0.246 | 1.493 | 0.136 | 1.198 | 0.098 | 1.422 | 0.062 | 1.360 | 0.101 |

| Germany | 79.45 | 1.986 | 1.392 | 0.053 | 0.795 | 0.167 | 1.567 | 0.097 | 1.610 | 0.106 | 1.679 | 0.076 | 1.833 | 0.064 |

| Greece | 43.2 | 4.607 | 0.867 | 0.180 | 0.151 | 0.343 | 0.479 | 0.211 | 0.642 | 0.266 | 0.528 | 0.288 | 0.092 | 0.216 |

| Hungary | 48.95 | 3.634 | 1.054 | 1.201 | 1.070 | 1.174 | 0.942 | 1.168 | 1.178 | 1.128 | 0.979 | 1.177 | 0.625 | 1.208 |

| Iceland | 84.5 | 8.042 | 1.432 | 0.079 | 1.362 | 0.154 | 1.674 | 0.238 | 1.341 | 0.219 | 1.768 | 0.123 | 2.016 | 0.205 |

| India | 35.1 | 4.678 | 0.403 | 0.076 | −1.110 | 0.206 | 0.005 | 0.161 | −0.332 | 0.095 | 0.013 | 0.077 | −0.378 | 0.108 |

| Indonesia | 30.0 | 7.071 | 0.001 | 0.151 | −0.932 | 0.534 | −0.177 | 0.238 | −0.324 | 0.233 | −0.569 | 0.196 | −0.645 | 0.248 |

| Ireland | 74.2 | 2.764 | 1.353 | 0.086 | 1.082 | 0.174 | 1.488 | 0.119 | 1.671 | 0.126 | 1.629 | 0.135 | 1.600 | 0.131 |

| Italy | 47.8 | 5.053 | 1.018 | 0.069 | 0.452 | 0.122 | 0.493 | 0.150 | 0.847 | 0.162 | 0.444 | 0.137 | 0.286 | 0.162 |

| Japan | 73.95 | 2.625 | 1.015 | 0.051 | 1.020 | 0.074 | 1.517 | 0.197 | 1.168 | 0.193 | 1.386 | 0.131 | 1.421 | 0.189 |

| Korea, Rep. | 53.5 | 4.979 | 0.719 | 0.046 | 0.372 | 0.151 | 1.117 | 0.145 | 0.942 | 0.138 | 1.016 | 0.118 | 0.532 | 0.106 |

| Latvia | 49.5 | 7.388 | 0.806 | 0.046 | 0.548 | 0.212 | 0.781 | 0.200 | 1.042 | 0.092 | 0.777 | 0.164 | 0.345 | 0.153 |

| Lithuania | 53.2 | 5.764 | 0.925 | 0.050 | 0.799 | 0.098 | 0.844 | 0.180 | 1.087 | 0.091 | 0.806 | 0.174 | 0.420 | 0.201 |

| Luxembourg | 83.15 | 2.739 | 1.552 | 0.060 | 1.396 | 0.092 | 1.734 | 0.119 | 1.736 | 0.083 | 1.818 | 0.054 | 2.001 | 0.142 |

| Malaysia | 49.1 | 2.712 | −0.368 | 0.159 | 0.213 | 0.173 | 1.047 | 0.113 | 0.606 | 0.140 | 0.501 | 0.073 | 0.200 | 0.136 |

| Mexico | 32.15 | 2.961 | 0.109 | 0.137 | −0.625 | 0.242 | 0.135 | 0.153 | 0.312 | 0.121 | −0.507 | 0.114 | −0.489 | 0.259 |

| Morocco | 36.3 | 3.262 | −0.662 | 0.077 | −0.405 | 0.086 | −0.130 | 0.063 | −0.183 | 0.086 | −0.163 | 0.087 | −0.284 | 0.096 |

| New Zealand | 91.95 | 3.136 | 1.554 | 0.056 | 1.366 | 0.149 | 1.772 | 0.109 | 1.840 | 0.136 | 1.893 | 0.052 | 2.287 | 0.071 |

| Norway | 85.95 | 2.438 | 1.634 | 0.078 | 1.254 | 0.113 | 1.898 | 0.066 | 1.543 | 0.183 | 1.959 | 0.051 | 2.114 | 0.113 |

| Peru | 36.25 | 1.650 | 0.141 | 0.103 | −0.705 | 0.343 | −0.309 | 0.176 | 0.366 | 0.174 | −0.554 | 0.097 | −0.348 | 0.138 |

| Philippines | 29.9 | 5.270 | 0.018 | 0.099 | −1.279 | 0.354 | 0.008 | 0.106 | −0.093 | 0.091 | −0.458 | 0.084 | −0.592 | 0.130 |

| Poland | 51.1 | 10.182 | 0.927 | 0.149 | 0.695 | 0.267 | 0.552 | 0.112 | 0.899 | 0.103 | 0.592 | 0.150 | 0.524 | 0.185 |

| Portugal | 62.7 | 2.003 | 1.207 | 0.122 | 0.963 | 0.193 | 1.091 | 0.124 | 0.968 | 0.196 | 1.119 | 0.104 | 0.992 | 0.135 |

| Qatar | 63.85 | 6.175 | −0.982 | 0.246 | 0.985 | 0.201 | 0.722 | 0.202 | 0.533 | 0.207 | 0.728 | 0.179 | 0.896 | 0.266 |

| Romania | 39.1 | 7.152 | 0.451 | 0.091 | 0.226 | 0.168 | −0.155 | 0.150 | 0.449 | 0.206 | 0.097 | 0.226 | −0.215 | 0.108 |

| Russia | 26.35 | 2.870 | −0.905 | 0.209 | −0.897 | 0.243 | −0.283 | 0.196 | −0.349 | 0.117 | −0.824 | 0.082 | −0.939 | 0.114 |

| Saudi Arabia | 44.4 | 6.885 | −1.726 | 0.140 | −0.425 | 0.222 | −0.016 | 0.240 | 0.057 | 0.089 | 0.111 | 0.086 | 0.031 | 0.207 |

| Slovak Republic | 46.35 | 4.793 | 0.928 | 0.041 | 0.896 | 0.162 | 0.757 | 0.110 | 0.975 | 0.120 | 0.521 | 0.083 | 0.249 | 0.140 |

| Slovenia | 61.05 | 2.892 | 1.032 | 0.058 | 0.988 | 0.143 | 1.040 | 0.095 | 0.772 | 0.129 | 1.006 | 0.062 | 0.892 | 0.103 |

| South Africa | 44.9 | 2.404 | 0.633 | 0.043 | −0.118 | 0.140 | 0.440 | 0.135 | 0.420 | 0.203 | 0.086 | 0.099 | 0.158 | 0.201 |

| Spain | 63.25 | 4.655 | 1.105 | 0.100 | 0.057 | 0.285 | 1.152 | 0.289 | 1.082 | 0.196 | 1.093 | 0.108 | 1.001 | 0.293 |

| Sweden | 89.5 | 3.364 | 1.573 | 0.066 | 1.153 | 0.154 | 1.870 | 0.150 | 1.724 | 0.135 | 1.908 | 0.064 | 2.185 | 0.064 |

| Switzerland | 87.2 | 2.441 | 1.553 | 0.063 | 1.304 | 0.089 | 1.979 | 0.102 | 1.678 | 0.116 | 1.871 | 0.079 | 2.072 | 0.059 |

| Thailand | 35.45 | 1.700 | −0.524 | 0.426 | −0.885 | 0.472 | 0.314 | 0.071 | 0.221 | 0.089 | −0.031 | 0.161 | −0.352 | 0.084 |

| Tunisia | 43.4 | 3.470 | −0.500 | 0.686 | −0.380 | 0.520 | 0.151 | 0.297 | −0.199 | 0.204 | −0.005 | 0.105 | −0.086 | 0.161 |

| Turkey | 40.5 | 5.246 | −0.300 | 0.313 | −1.098 | 0.381 | 0.180 | 0.147 | 0.213 | 0.153 | −0.030 | 0.170 | −0.101 | 0.190 |

| UAE | 64.8 | 6.109 | −0.957 | 0.158 | 0.805 | 0.129 | 1.092 | 0.291 | 0.779 | 0.246 | 0.582 | 0.199 | 1.070 | 0.115 |

| UK | 80.4 | 4.235 | 1.335 | 0.079 | 0.395 | 0.179 | 1.623 | 0.143 | 1.721 | 0.101 | 1.696 | 0.088 | 1.795 | 0.133 |

| US | 72.85 | 2.833 | 1.123 | 0.133 | 0.356 | 0.264 | 1.548 | 0.095 | 1.463 | 0.143 | 1.570 | 0.076 | 1.418 | 0.212 |

| Full Sample | 58.384 | 20.437 | 0.638 | 0.902 | 0.355 | 0.847 | 0.892 | 0.769 | 0.861 | 0.738 | 0.787 | 0.883 | 0.757 | 0.982 |

Table A4.

Correlation coefficients matrix.

Table A4.

Correlation coefficients matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FDI | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | RGDPpc | 0.186 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | POP | −0.140 *** | −0.131 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 4 | LPI | 0.138 *** | 0.744 *** | 0.125 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 5 | FD | 0.136 *** | 0.636 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.776 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 6 | FUEL | 0.119 *** | 0.070 *** | −0.267 *** | −0.131 *** | −0.127 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 7 | ORME | 0.267 *** | −0.084 *** | −0.438 *** | −0.154 *** | −0.035 | −0.095 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 8 | CPI | 0.107 *** | 0.840 *** | −0.156 *** | 0.732 *** | 0.602 *** | −0.110 *** | 0.037 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 9 | VAA | 0.035 | 0.556 *** | −0.059 * | 0.478 *** | 0.393 *** | −0.474 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.673 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| 10 | PS | 0.014 | 0.765 *** | −0.103 *** | 0.566 *** | 0.359 *** | −0.141 *** | −0.018 | 0.772 *** | 0.663 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 11 | GE | 0.106 *** | 0.805 *** | −0.058 * | 0.775 *** | 0.618 *** | −0.190 *** | −0.030 | 0.921 *** | 0.725 *** | 0.814 *** | 1.000 | |||

| 12 | RQ | 0.123 *** | 0.779 *** | −0.092 *** | 0.667 *** | 0.526 *** | −0.223 *** | 0.059 * | 0.864 *** | 0.787 *** | 0.806 *** | 0.913 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 13 | RL | 0.095 *** | 0.814 *** | −0.075 ** | 0.722 *** | 0.590 *** | −0.191 *** | 0.004 | 0.928 *** | 0.776 *** | 0.839 *** | 0.958 *** | 0.937 *** | 1.000 | |

| 14 | CC | 0.091 *** | 0.832 *** | −0.150 *** | 0.724 *** | 0.584 *** | −0.135 *** | 0.057 * | 0.968 *** | 0.733 *** | 0.808 *** | 0.948 *** | 0.908 *** | 0.961 *** | 1.000 |

Note: ***, **, * denote the level of significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Average of inward FDI stocks in millions of USD by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the OECD database [58].

Figure A1.

Average of inward FDI stocks in millions of USD by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the OECD database [58].

Figure A2.

Average of institutional quality indicators by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the WGI database [63].

Figure A2.

Average of institutional quality indicators by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the WGI database [63].

Figure A3.

Average of fuel, ores, and metals exports as a % of merchandise exports by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the WDI database [62].

Figure A3.

Average of fuel, ores, and metals exports as a % of merchandise exports by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the WDI database [62].

Figure A4.

Average of the financial development index by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the IMF database [37].

Figure A4.

Average of the financial development index by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the IMF database [37].

Figure A5.

Average of the corruption perception index quality by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on Transparency International’s CPI [68].

Figure A5.

Average of the corruption perception index quality by country. Source: Authors’ calculations based on Transparency International’s CPI [68].

References

- Findlay, R. Relative Backwardness, Direct Foreign Investment, and The Transfer of Technology: A Simple Dynamic Model. Q. J. Econ. 1978, 92, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borensztein, E.; De Gregorio, J.; Lee, J.W. How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Economic Growth? J. Int. Econ. 1998, 45, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, S.; Somwaru, A. Impact of Foreign Direct Investment and Trade on Economic Growth: Evidence from Developing Countries. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 86, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, D.; Klasen, S.; Nowak-Lehmann, D.F. In Search of FDI-led Growth in Developing Countries. The Way Forward. Econ. Model. 2008, 25, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A. FDI and Economic Growth: The Role of Natural Resources? J. Econ. Stud. 2018, 45, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Borojo, D.G.; Yushi, J.; Desalegn, T.A.; McMillan, D. The Impacts of Chinese FDI on Domestic Investment and Economic Growth for Africa. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, M.J.; Kim, J. Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth: Is More Financial Development Better? Econ. Model. 2020, 93, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younsi, M.; Bechtini, M.; Khemili, H. The Effects of Foreign Aid, Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Investment on Economic Growth in African Countries: Nonlinearities and Complementarities. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2021, 33, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Investment Report 2018. Investment and New Industrial Policies. UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2018. Available online: http://worldinvestmentreport.unctad.org/world-investment-report-2018 (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Asongu, S. Financial Development Dynamic Thresholds of Financial Globalization: Evidence from Africa. J. Econ. Stud. 2014, 41, 166–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Opoku, E.E.O. Foreign Direct Investment, Regulations and Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Econ. Anal. Policy 2015, 47, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Investment Report 2020. International Production Beyond the Pandemic. UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2020. Available online: https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2020 (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- World Investment Report 2022. International Tax Reforms and Sustainable Investment. UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2022. Available online: https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2022 (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Anil, İ.; Armutlulu, I.; Canel, C.; Porterfield, R. The Determinants of Turkish Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Mod. Econ. 2011, 2, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeoha, A.; Cattaneo, N. FDI Flows to Sub-Saharan Africa: The Impact of Finance, Institutions, and Natural Resource Endowment. Comp. Econ. Stud. 2012, 54, 597–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y. Natural Resource Endowment, Institutional Endowment and China’s Direct Investment in ASEAN. World Econ. 2018, 8, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavilin, J.; Songur, H. Institutional Distance and Turkey’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 54, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daude, C.; Stein, E. The Quality of Institutions and Foreign Direct Investment. Econ. Politics 2007, 19, 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénassy-Quéré, A.; Coupet, M.; Mayer, T. Institutional Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment. World Econ. 2007, 30, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, M.; Hefeker, C. Political risk, Institutions and Foreign Direct Investment. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2007, 23, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, S.; Subasat, T. Governance and Foreign Direct Investment: A Panel Gravity Model Approach. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2012, 26, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannaga, A.; Gangi, Y.; Abdrazak, R.; Al Fakhry, B. The Effects of Good Governance on Foreign Direct Investment Inflows in Arab Countries. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2013, 23, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksynska, M.; Havrylchyk, O. FDI from The South: The Role of Institutional Distance and Natural Resources. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2013, 29, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegenast, T. Opening Pandora’s Box? Inclusive Institutions and The Onset of Internal Conflict in Oil-Rich Countries. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 34, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eregha, P.B.; Mesagan, E.P. Oil Resource Abundance, Institutions and Growth: Evidence from Oil Producing African Countries. J. Policy Model. 2016, 38, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, B.; Khan, M.K. Do Institutional Quality and Natural Resources Affect the Outward Foreign Direct Investment of G7 Countries? J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Yadav, S.S.; Gautam, V. Financial System Development and Foreign Direct Investment: A Panel Data Study for BRIC Countries. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2013, 14, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnamkhasti, J.G.; Mehregan, N.; Najarzadeh, R.; Hosseini-Nasab, E. Financial Development as a Key Determinant of FDI Inflow to Developing Countries. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. 2015, 22, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Desbordes, R.; Wei, S.-J. The Effects of Financial Development on Foreign Direct Investment. J. Dev. Econ. 2017, 127, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaubauera, J.; Neumayerb, E.; Nunnenkamp, P. Financial Market Development in Host and Source Countries and Their Effects on Bilateral Foreign Direct Investment. World Econ. 2020, 43, 534–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H. Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment: Globalization Induced Changes and the Roles of FDI Policies. A Background Paper for the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics Held in Oslo; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-J. Is Corruption Bad for Economic Growth? Evidence from Asia-Pacific Countries. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Corruption Culture and Corporate Misconduct. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 122, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beysenbaev, R.; Dus, Y. Proposals for Improving the Logistics Performance Index. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2020, 36, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederer, C.K.; Arvis, J.F.; Ojala, L.M.; Kiiski, T.M.M. The World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index. In International Encyclopedia of Transportation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svirydzenka, K. Introducing a New Broad-Based Index of Financial Development. IMF Working Paper 16/5. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298912171_Introducing_a_New_Broad-based_Index_of_Financial_Development (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Le, A.H.; Kim, T. The Impact of Institutional Quality on FDI Inflows: The Evidence from Capital Outflow of Asian Economies. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Zurawicki, L. Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younsi, M.; Bechtini, M. Does Good Governance Matter for FDI? New Evidence from Emerging Countries Using a Static and Dynamic Panel Gravity Model Approach. Econ. Transit. Institutional Change 2020, 27, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.A.; Hasanat Shah, S.; Jing, W.; Hasnat, H. Does The Quality of Institutions in Host Countries Affect the Location Choice of Chinese OFDI: Evidence from Asia and Africa? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Zou, C. The quality of the host country system institutional distance and China’s foreign direct investment location. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2013, 7, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Tomio, B.T.; Amal, M. Institutional Distance and Brazilian Outward Foreign Direct Investment. M@n@gement 2015, 18, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, Z. How Do Cultural and Institutional Distance Affect China’s OFDI towards the OBOR Countries? Balt. J. Eur. Stud. 2017, 7, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, C.; Luo, Y.; De Vita, G. Institutional Difference and Outward FDI: Evidence from China. Empir. Econ. 2020, 58, 1837–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.J.; Clegg, L.J.; Cross, A.R.; Liu, X.; Voss, H.; Zheng, P. The Determinants of Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, A.A.; Adhikary, B.K. Does Good Governance Matter for FDI Inflows? Evidence from Asian Economies. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2012, 17, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasat, T.; Bellos, S. Governance and Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America: A panel Gravity Model Approach. Lat. Am. J. Econ. 2013, 50, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Rahman, Z. Does Governance Facilitate Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Countries? Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 164–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchoucha, N.; Benammou, S. Does Institutional Quality Matter Foreign Direct Investment? Evidence from African Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 11, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Ge, L.; Li, Z.; Li, C.-Y. Financial Development and Natural Resources: The Dynamics of China’s Outward FDI. World Econ. 2021, 45, 739–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinda, T. Increasing Private Capital Flows to Developing Countries: The Role of Physical and Financial Infrastructure in 58 Countries, 1970–2003. Appl. Econ. Int. Dev. 2010, 10, 57–72. [Google Scholar]