Thirty Years of Research and Methodologies in Value Co-Creation and Co-Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What is the evolution of co-design/co-creation in terms of scientific production and citations?The rationale behind RQ1 is that the evolution of co-design and co-creation indicates the level of interest in the field and provides insights into the importance of the scientific production around these topics [16];

- RQ2: Who are the most contributing authors in co-design/co-creation in terms of the number of publications and citations?The rationale behind RQ2 is that the most contributing authors and most cited publications are relevant so that future researchers or new researchers can identify the key studies in the field and the most important authors;

- RQ3: What are the methodologies for co-design/co-creation that have been reported in the scientific literature?The rationale behind RQ3 is that, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review that summarizes the methodologies defined for co-design and co-creation, and this is one of the most important contributions to the literature in the field for practitioners and other researchers;

- RQ4: What are the trend topics in co-design/co-creation in terms of content analysis based on authors’ keywords?The rationale behind RQ4 is that the bibliometric analysis and the scoping review are useful to identify trends and future research directions in the field so that other researchers can focus on specific gaps in research and help the community advance knowledge in the field.

2. Methodology

2.1. Bibliometric Analysis

2.1.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- The title should include the term for each field (i.e., co-creation and co-design);

- Journal articles, reviews, conference papers, short surveys, editorials, books, and book chapters indexed in Scopus;

- Articles focused on co-design/co-creation.

- Book reviews, notes, letters, preprints, and erratum were not considered in the bibliometric analysis;

- Documents with undefined author names;

- Documents with undefined affiliation.

2.1.2. Article Information Retrieval and Filtering

2.2. Scoping Review

- (TITLE (“co-design”) AND TITLE (method* OR framework)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”));

- (TITLE (“co-creation”) AND TITLE (method* OR framework)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”)).

3. Results

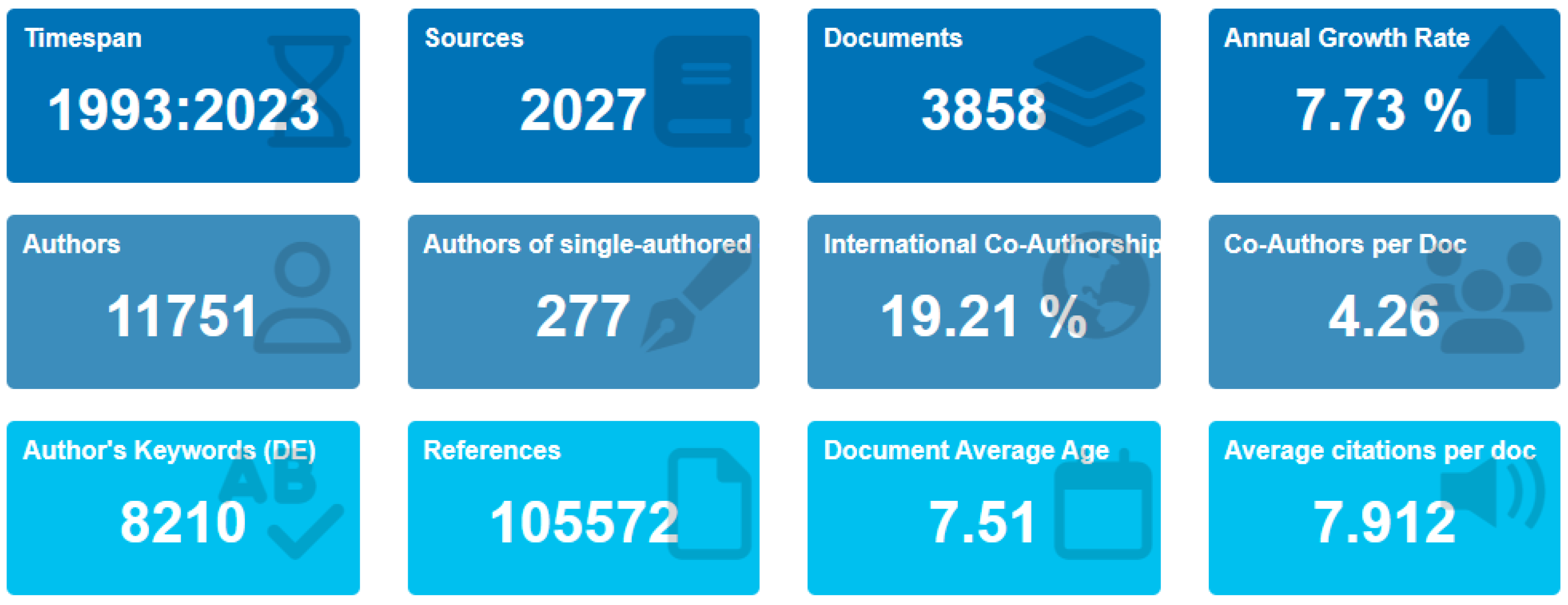

3.1. Dataset Main Information

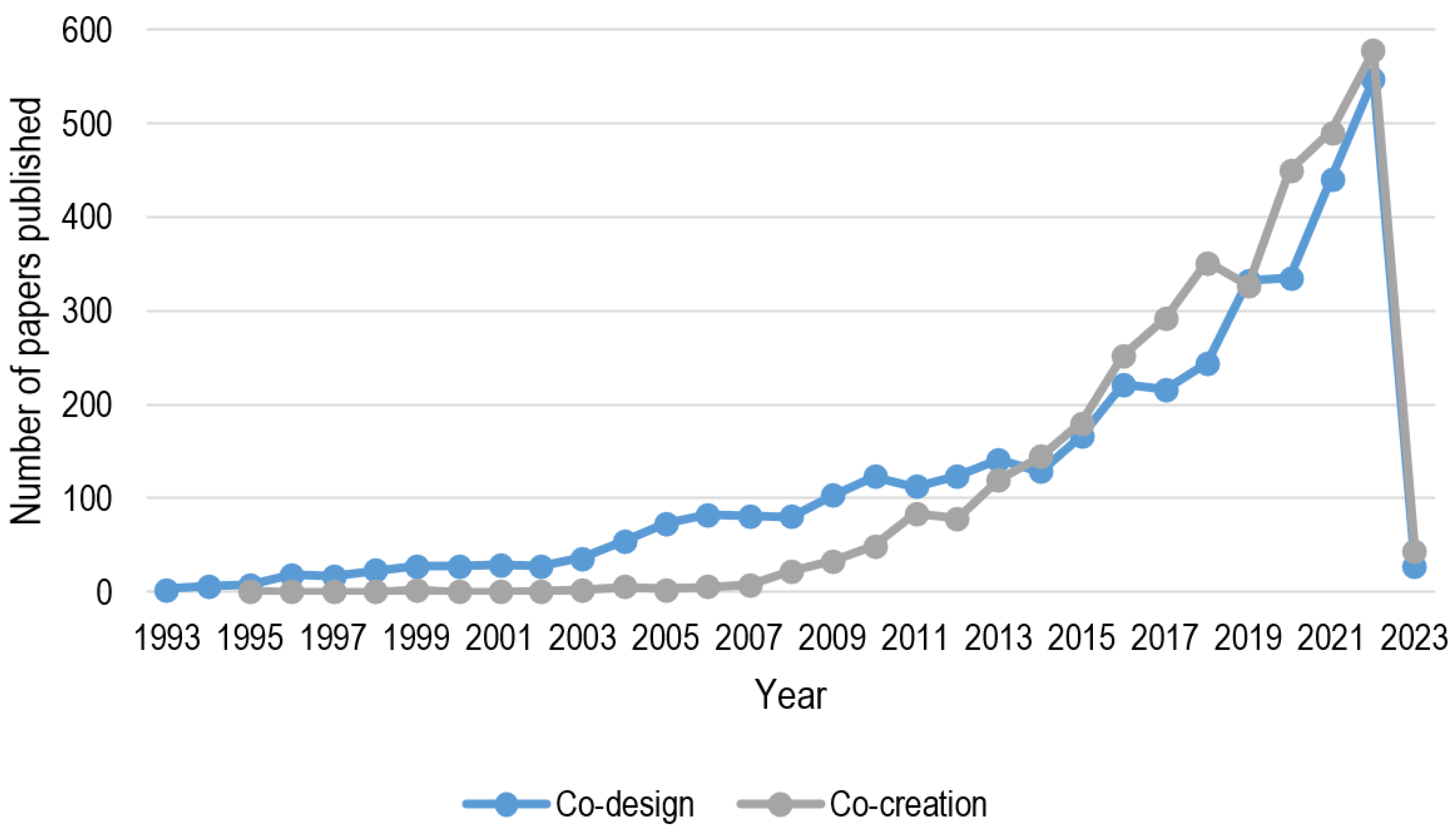

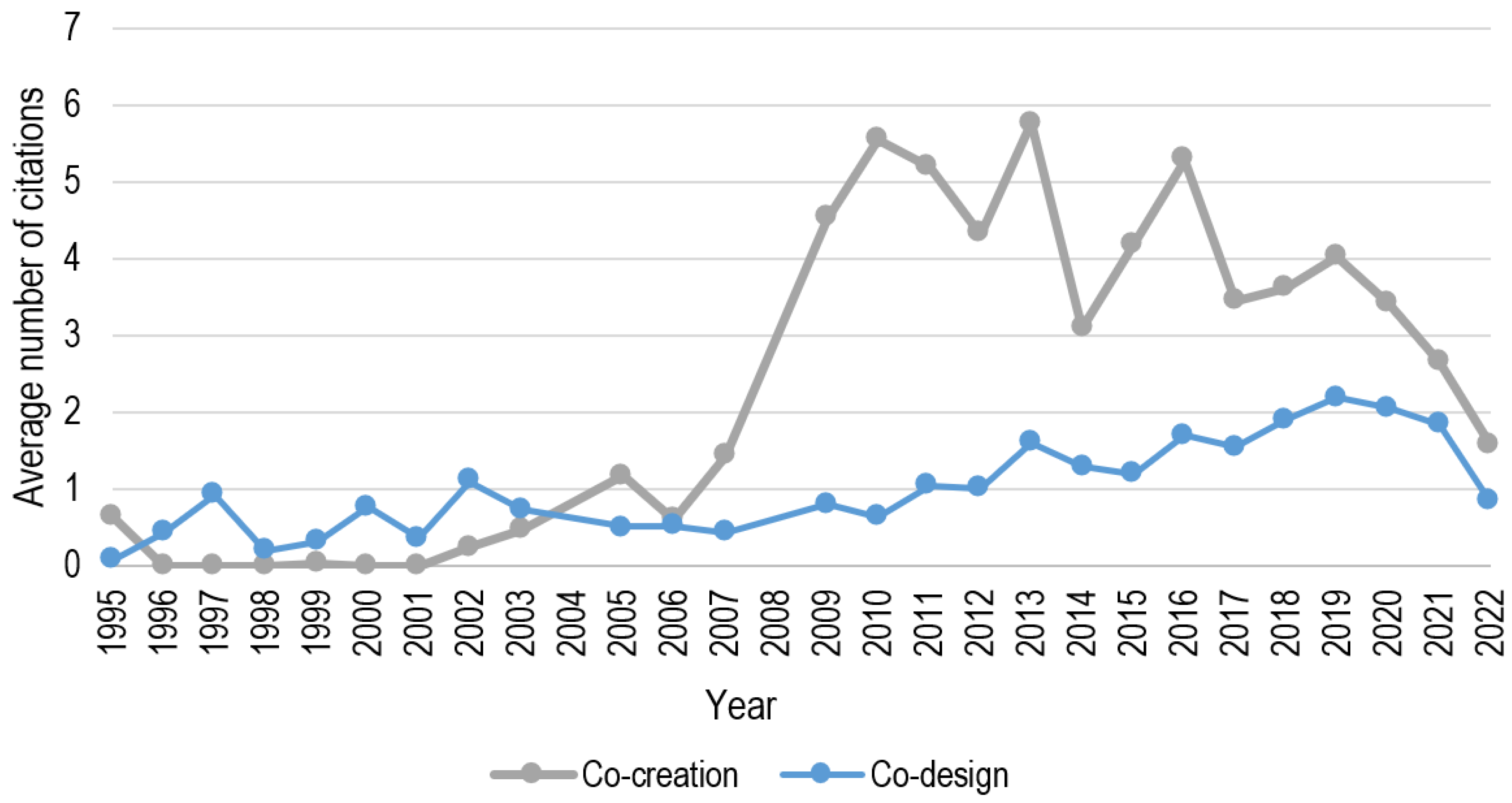

3.2. Scientific Production and Citations

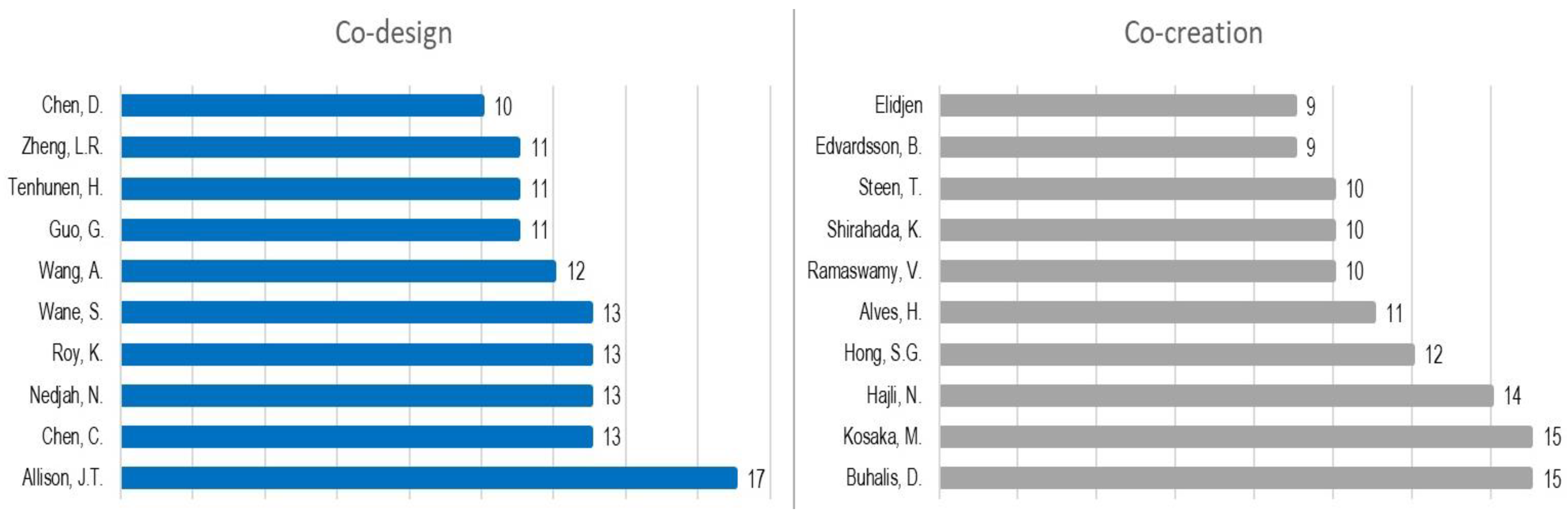

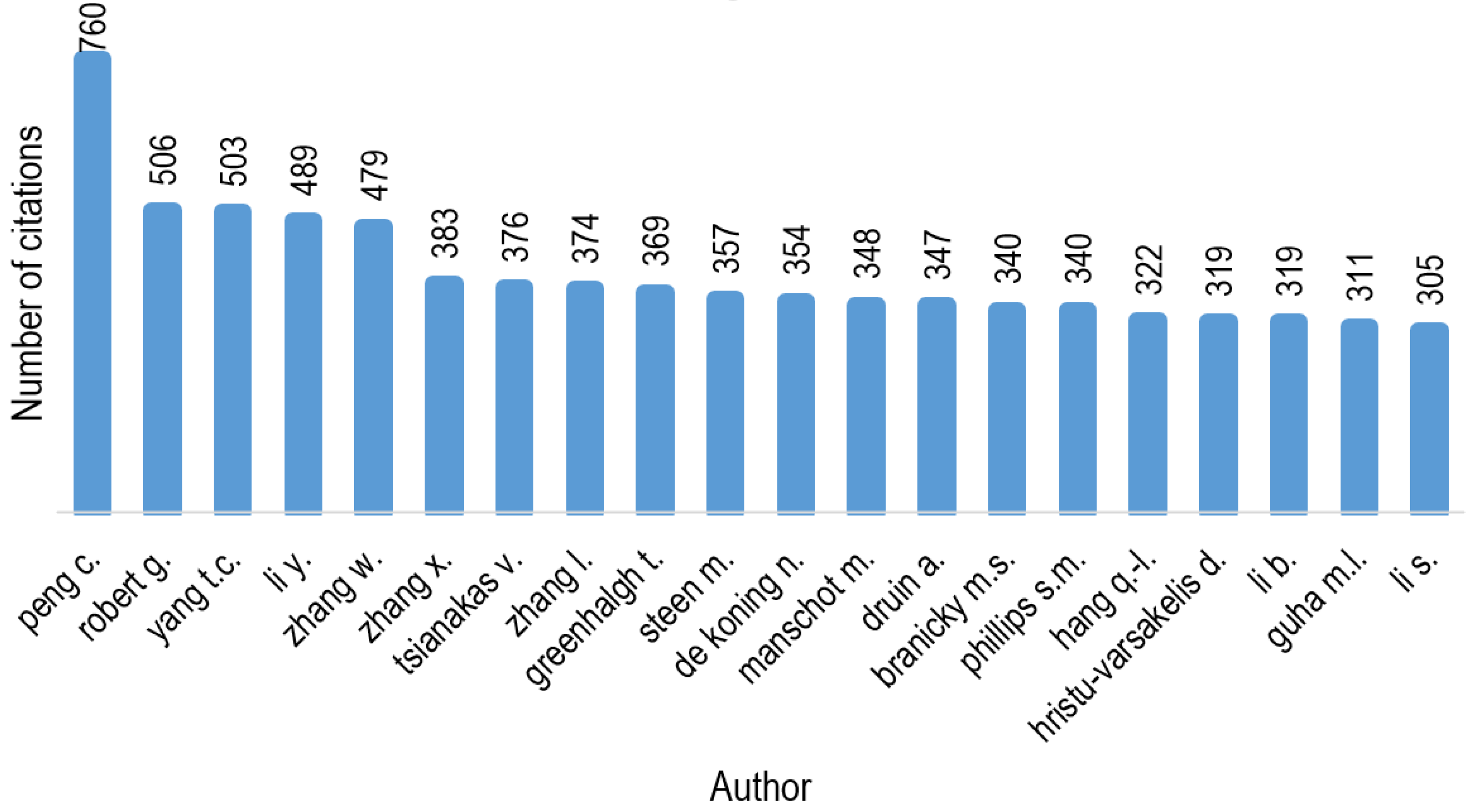

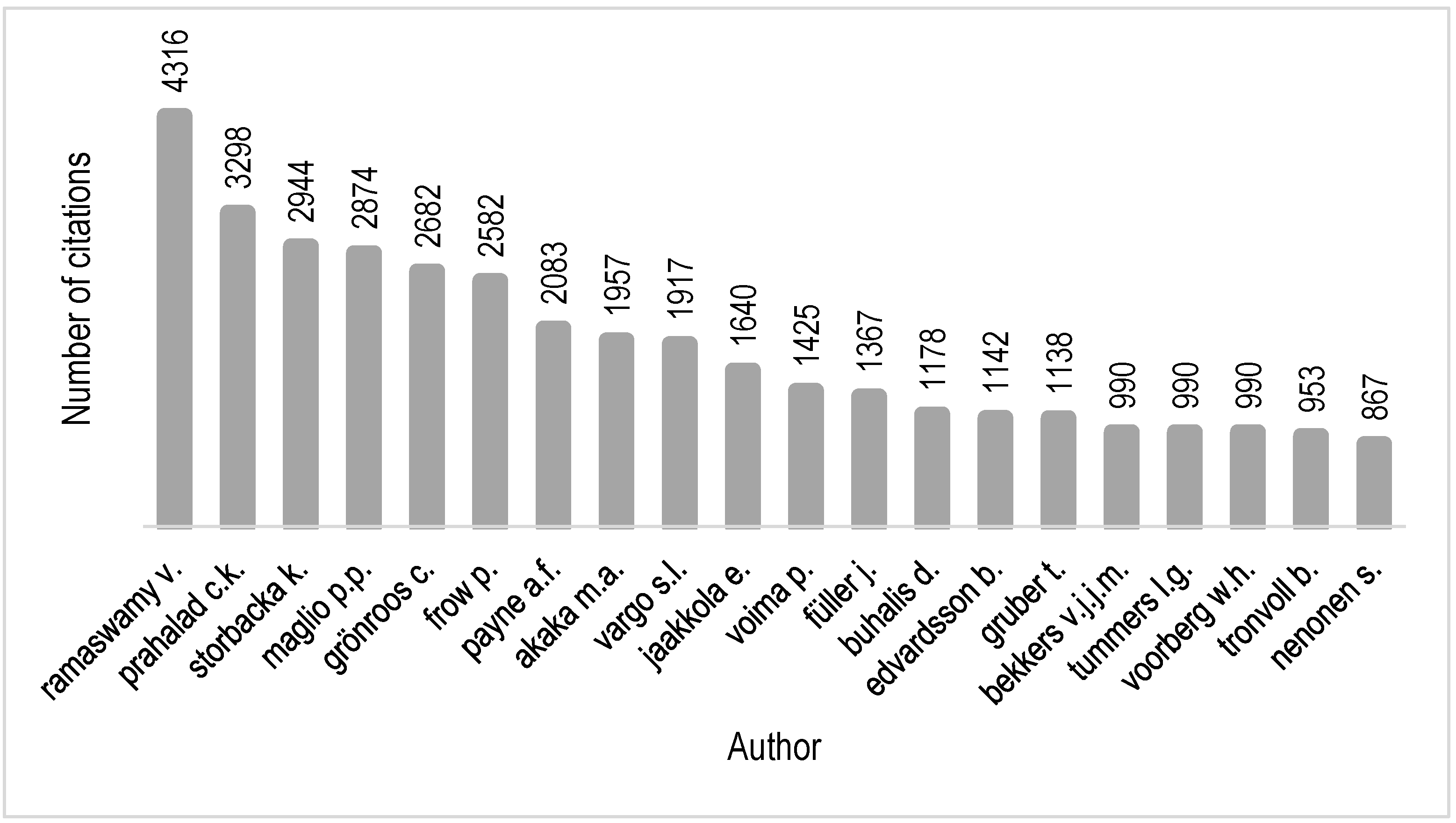

3.3. Author Analysis

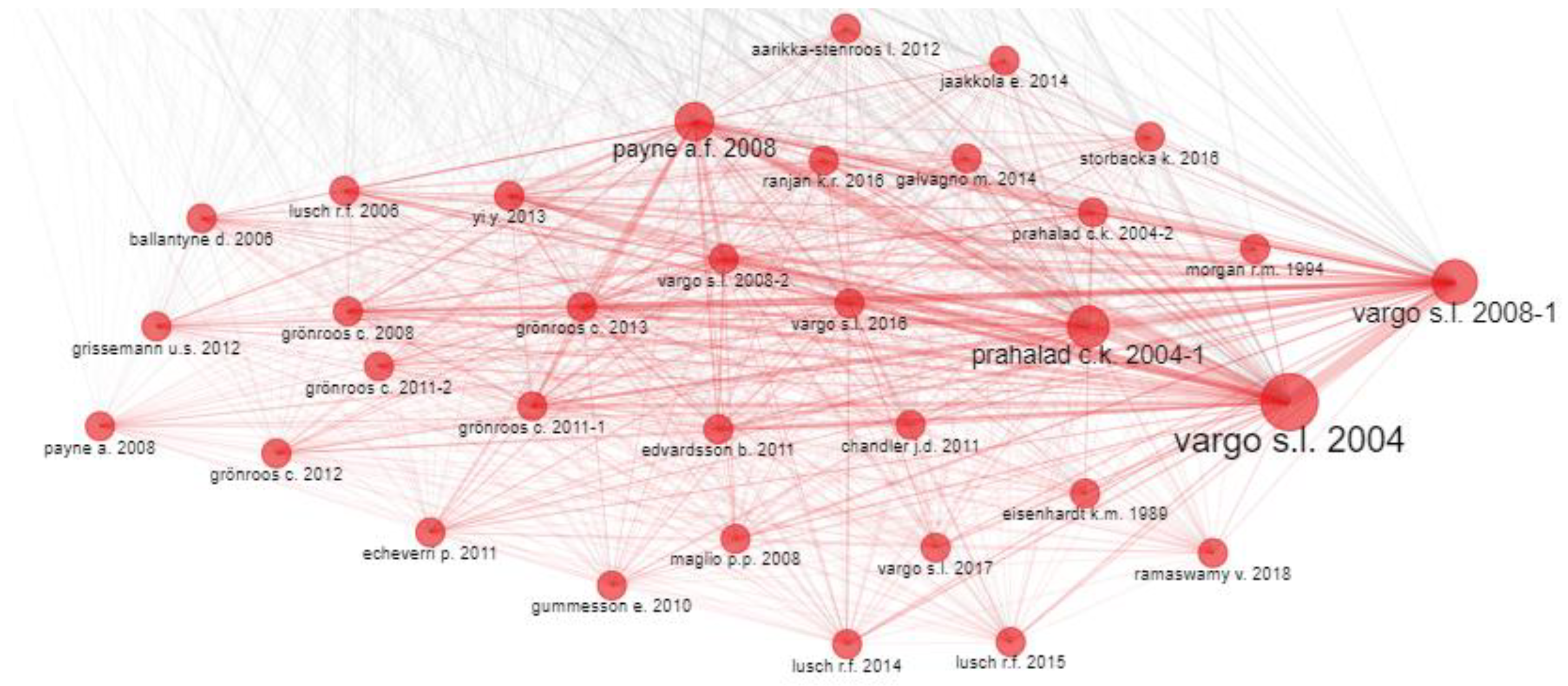

3.4. Co-Citation Network

3.5. Content Analysis

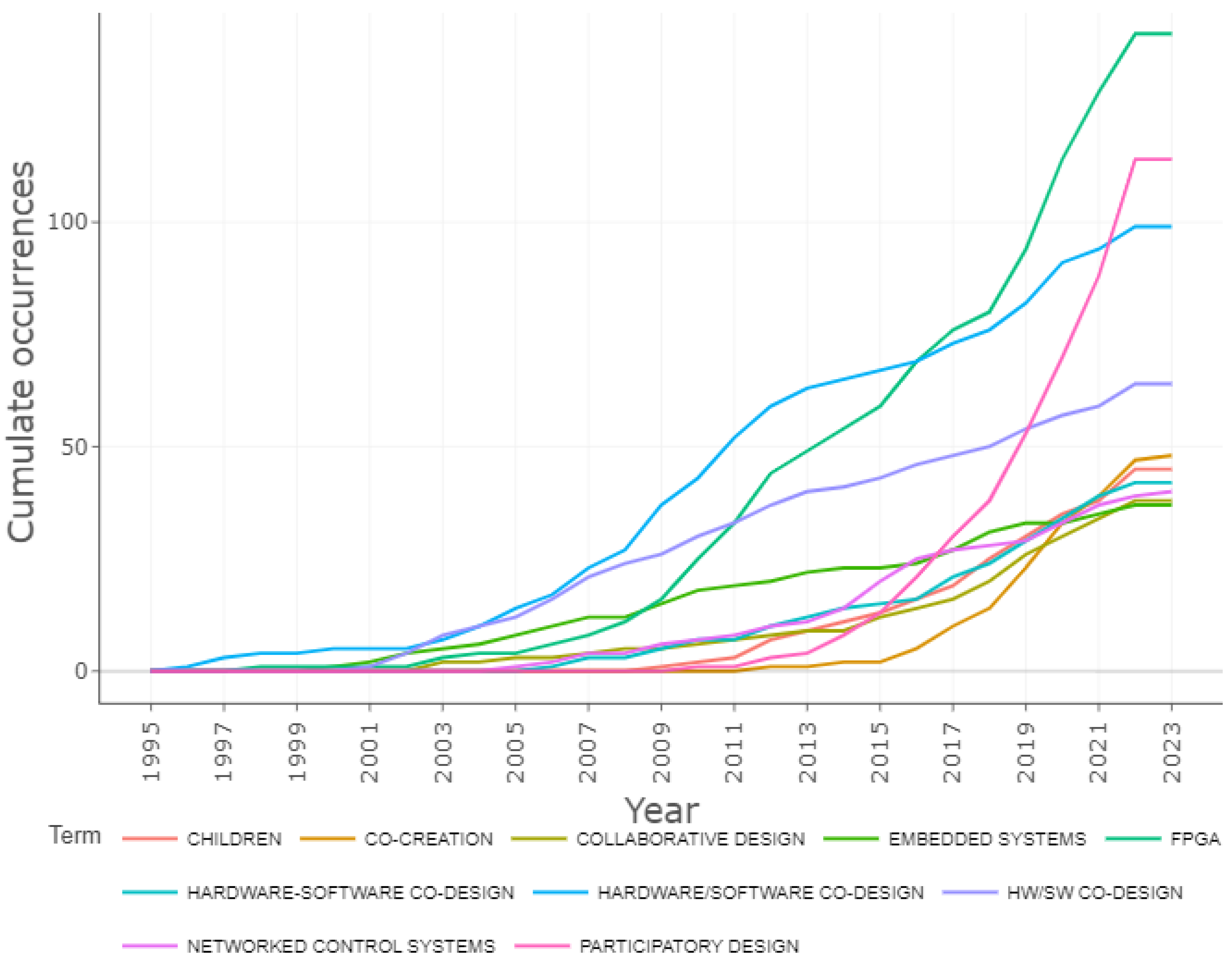

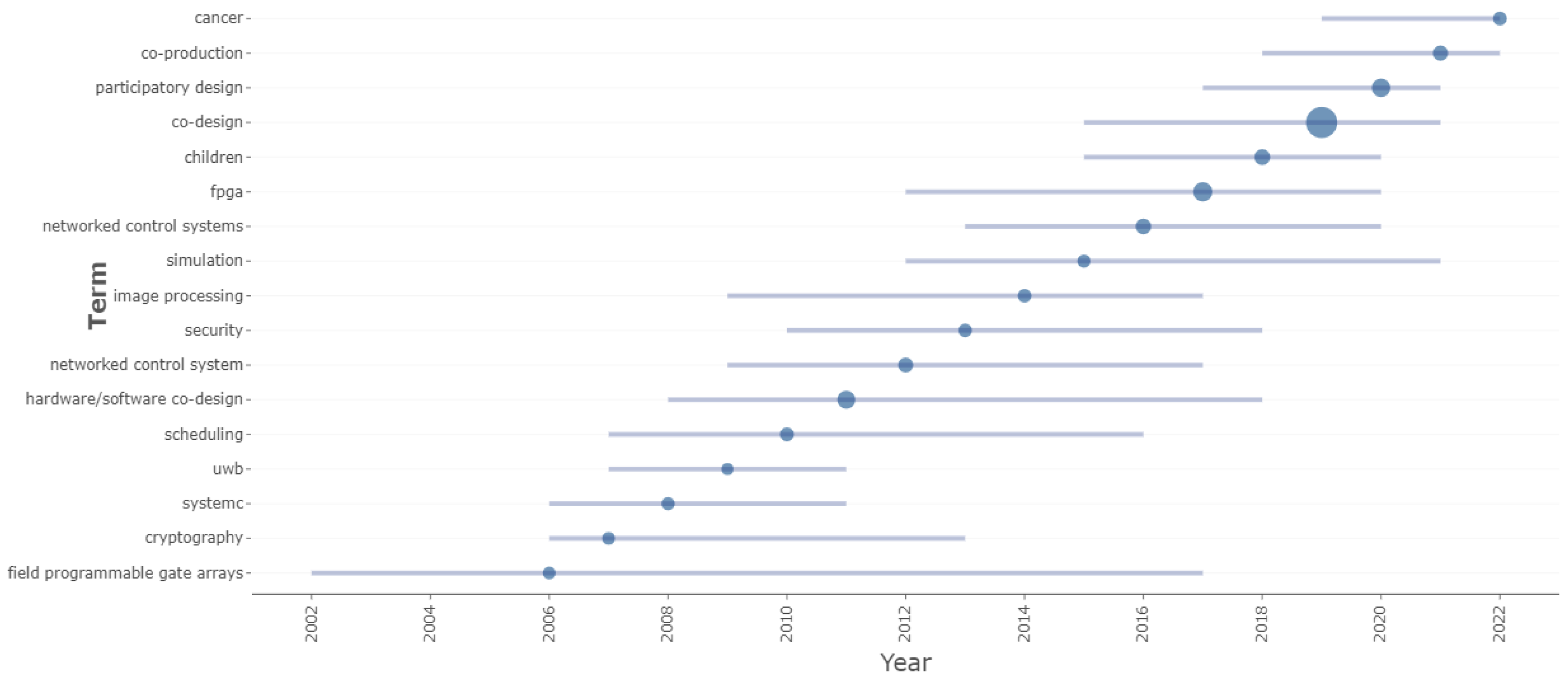

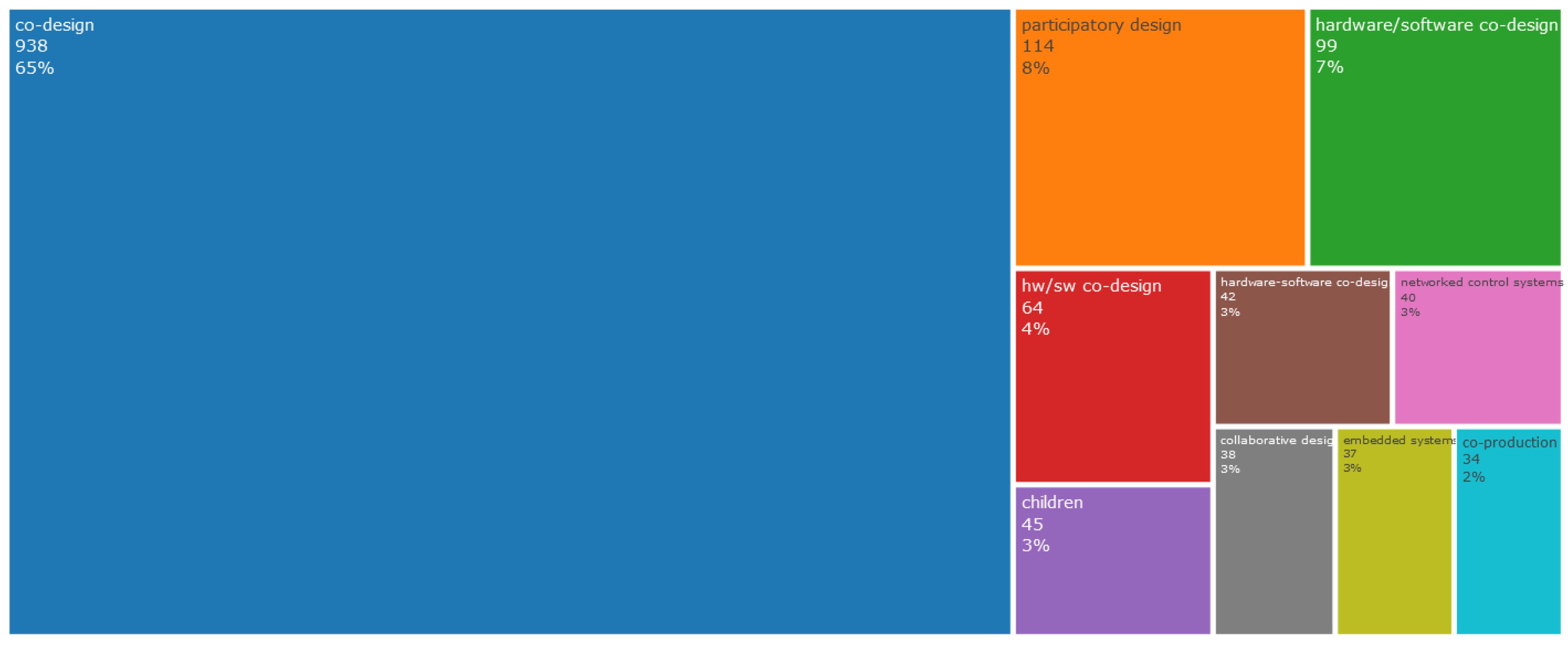

3.5.1. Keywords Analysis and Trend Topics—Co-Design

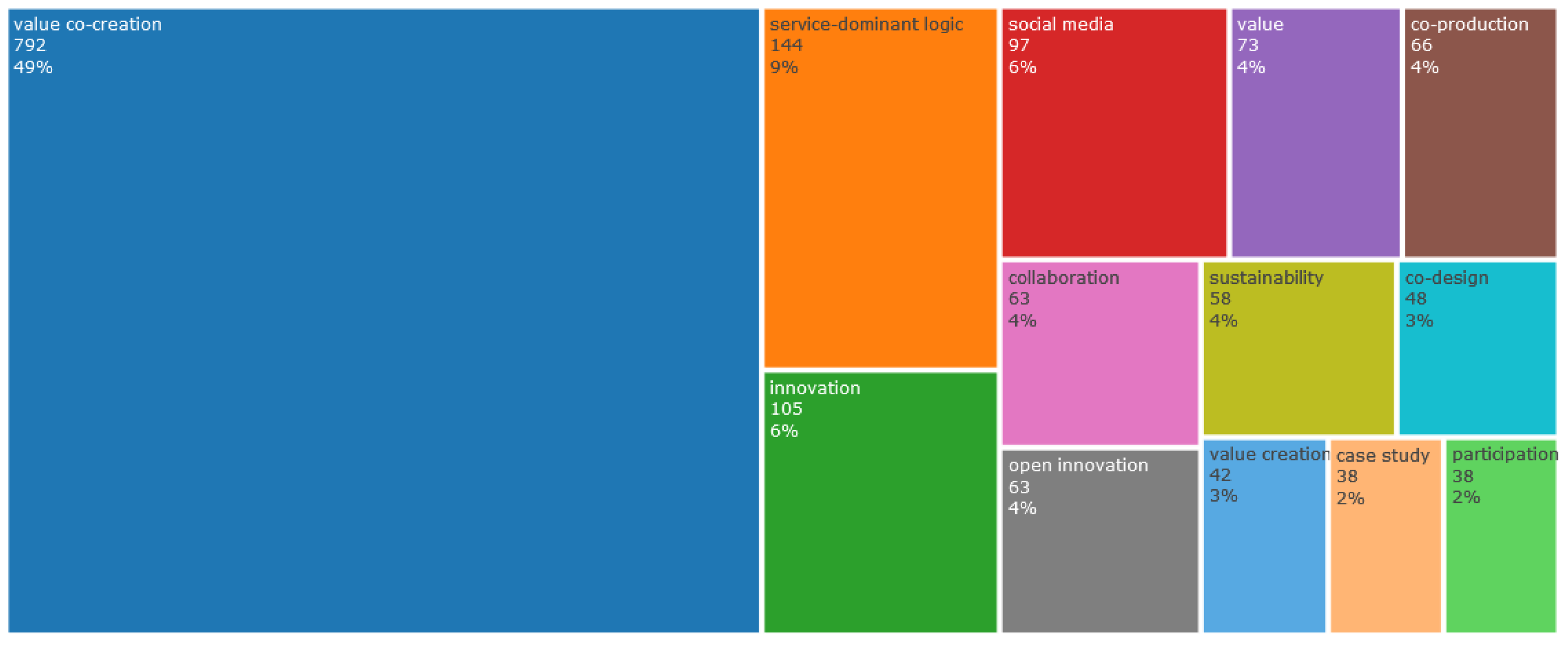

3.5.2. Keywords Analysis and Trend Topics—Co-Creation

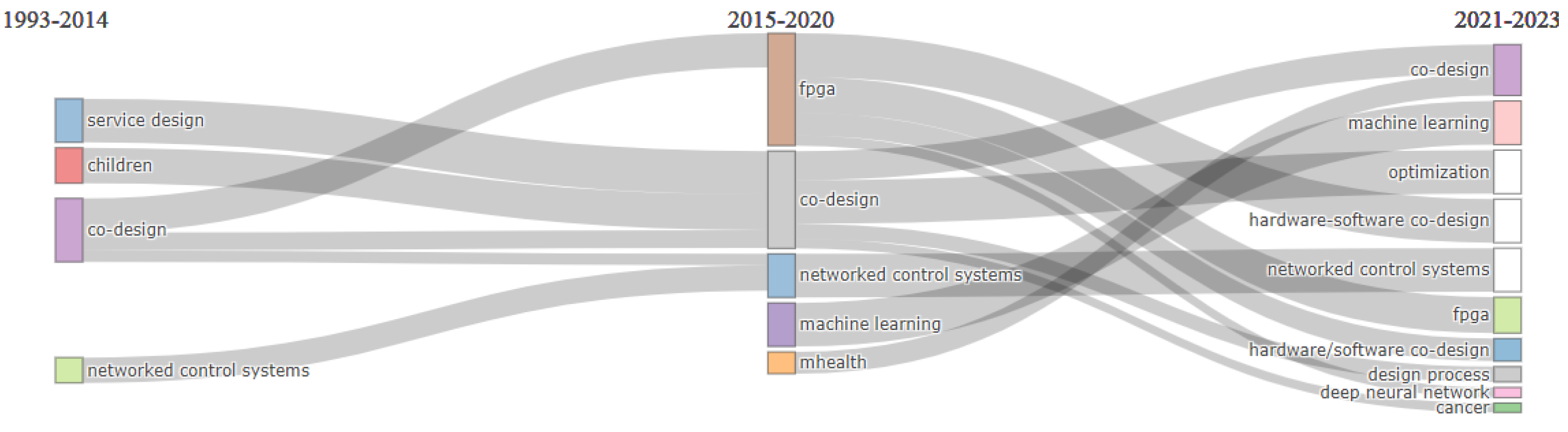

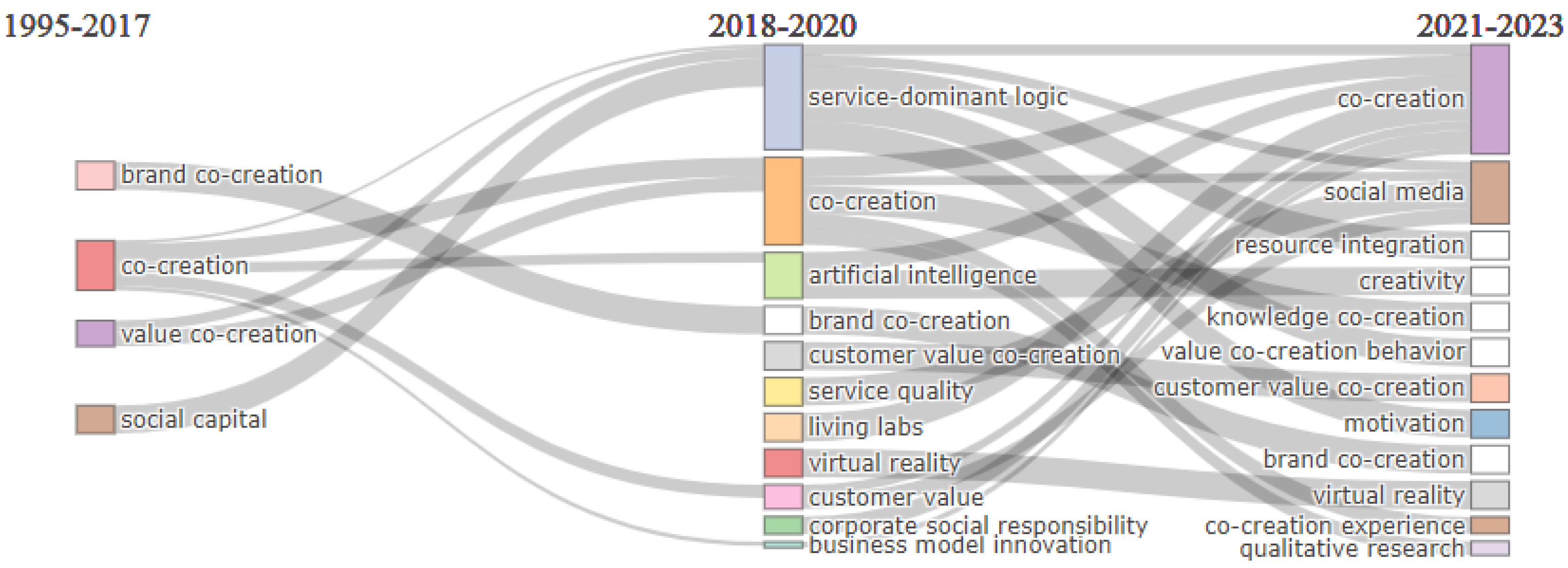

3.6. Thematic Evolution

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1: What Is the Evolution of Co-Design/Co-Creation in Terms of Scientific Production and Citations?

4.2. RQ2: Who Are the Most Contributing Authors in Co-Design/Co-Creation in Terms of the Number of Publications and Citations?

4.3. RQ3: What Are the Methodologies for Co-Design/Co-Creation That Have Been Reported in the Scientific Literature?

4.3.1. Methodologies for Co-Creation

4.3.2. Methodologies for Co-Design

4.3.3. Additional Considerations about Co-Design and Co-Creation

4.4. RQ4: What Are the Trend Topics in Co-Design/Co-Creation in Terms of Contents Analysis Based on Authors’ Keywords?

5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| N° | Reference | Research Field | Specific Context of Application | About the Stakeholders | Components/Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [36] | Planning process | Gamified urban planning. The co-creation process is applied based on a proposed planning solution | Experts (planners, architects, engineers, etc.) Non-experts (mayor, city council, district governor, etc.) | Step 1: To interact and explore the game environment. Step 2: To discuss the elements involved in the solution’s workflow. Step 3: To discuss and evaluate the proposed solution. Step 4: To propose changes or alternative solutions. |

| 2 | [37] | Marketing | The product storytelling process | Suppliers, employees, and consumers | Co-creation based on the DART model (Dialogue, Access, Risk-Benefits, Transparency) |

| 3 | [38] | Scientific publications | Co-creation of plain language summaries with the intended audience | 14 experts in patient engagement or in plain language summaries | Step 1: Rationale and scope. Step 2: Identify your target audience. Step 3: Consider the dissemination channels. Step 4: Identify your key stakeholders for co-creation. Step 5: Write. Step 6: Disseminate. Step 7: Track dissemination and measure success. |

| 4 | [39] | Public services | Co-creation in integrated public services | Service users and service providers | Step 1: Design Step 2: Delivery Step 3: Evaluation |

| 5 | [28] | Social innovation design | Modeling a co-creation design approach for intergenerational community development in a public square in a Shanghai community | Research team, stakeholders, and community participants. Moreover, 30 residents took their role as community participants | Steps of the co-creation method: Step 0: Establish trust relationships. Input Step 1: Find society topic. Step 2: Discovery needs. Step 3: Building shared vision. Output Step 4: Proof of concept and iteration. Step 5: Collaborative implementation. Step 6: Action co-building. Step 7: Ongoing operations. Step 8: Future vision. Step 9: Co-proposal. Co-creation workshop Step 1: Warm-up and icebreaker. Step 2: Community public impression. Step 3: Public area of co-creation. Step 4: Common assessment. |

| 6 | [40] | Aquaculture fish | Generation of 112 aquaculture fish product ideas. | 36 participants consumers from Germany, France, and Spain | Step 1: A warm-up debate. Step 2: Generating new product ideas. Step 3: To score acceptance of new ideas. Step 4: Complementary activities. Step 5: A general discussion for a deeper understanding. |

| 7 | [41] | Resilient healthcare | To promote resilient healthcare through co-creation | 20 stakeholder participants (5 kin representatives, 10 oncology nurses, and 5 physicians) | Step 1: Identify potential areas of co-creation. Step 2: Identify improvement areas and methods for involvement. Step 3: Preparation and individual learning from research and giving feedback. Step 4: Meeting in a collaborative learning forum and co-create consensus. |

| 8 | [42] | Quality in the daily workflow of hospitals | Improvement in the quality of the daily workflow in hospitals | 33 healthcare stakeholders (12 board members, 6 policymakers, 3 representatives of patient associations, 4 representatives of hospital organizations, and 8 healthcare scientists) | Step 1: Planning. Step 2: Control. Step 3: Improvement. Step 4: Leadership. Step 5: Culture. Step 6: Context. |

| 9 | [43] | Computer game development | Use of digital stories in a co-creation process as a way of participatory design for the research and design of a computer game | 14 students (autistic young people), 8 staff members, 4 technology representatives, and a doctoral researcher | A spiral mode in which the first step is plan, then act and after the following iteration, there should be a reflection process. Step 1: Plan (activities, resources, support). Step 2: Act (design, develop, test, evaluate). Step 3: Reflect. |

| 10 | [44] | Research | Definition of guidelines for research integrity | Researchers, research institutions, funders, and journals | Step 1: Preparation. Step 2: Sensitization. Step 3: Workshop exercises. Step 4: Analysis. |

| 11 | [45] | Teaching | Research-inspired teaching framework | 14 co-creators (students, educators, and self-identified facilitators of “Research Inspired Teaching”) | Three workshops: Co-define; Co-design; Co-refine. |

| 12 | [32] | Value co-creation with customers | Customer-service relationship | Co-creation may involve many stakeholders and many customers and communities | Co-creation context Customer Organizational Technological Environment Forms of co-creation Co-conception of ideas Co-design Co-research Co-marketing Feedback loop Co-conception for competition |

| 13 | [46] | Research | The research forum as a methodological framework that enables co-creation in the social sciences field | Called as co-researchers | Domains for co-creation in citizen social science: Participation Transdisciplinary Reflexivity Impact |

| 14 | [47] | Entrepreneurship | Use of ICT for supporting entrepreneurial activity | 60 participants | Participants worked to build together, generating ideas, and polishing those ideas in a co-creation process divided into two parts: 1. Identifying critical parts of the creation of an entrepreneurial project. 2. Developing two proposals to overcome the identified critical parts. |

| 15 | [48] | Medium-sized businesses | Human resources management | Managers, representatives from the unions, key persons identified in the process, working agency, business health representatives, financiers, and researchers | DART method by Ramaswamy: Dialog; Access; Risk; Transparency. |

| 16 | [49] | Tourism | User engagement for defining the optimal conditions for tourism | Local stakeholders, experts, and users | Co-creation workshop: Step 0. Selection of cases. Step 1. Identification of flows. Step 2. Recognition of optimal conditions. Step 3. Identification of adaptive actions. Step 4. Transformation of the data obtained. |

| 17 | [33] | Energy services | Co-creation in the design of energy services | End-users and experts from the building industry, energy industry, and service design | Co-creation in a living lab context: Step 1: Strategic. Step 2: Design. Step 3: Solution. |

| 18 | [50] | Architecture | Co-creating public spaces as an action-research project | 20 participants: Architecture students, researchers, and technicians from the CMC | Step 1. Approximation. Step 2. Recognizing. Step 3. Ideation. Step 4. Prototyping. |

| 19 | [51] | Science | Science-based co-creation | Researchers | Step 1: Decision engagement. Step 2: Inputs by actors. Step 3: Managing co-creation. |

| 20 | [52] | Public governance | Co-created governance solutions | Non-government actors, such as service users, voluntary groups and organizations, and private stakeholders, etc. | Components: Theories; Public value management; Public innovation; Collaborative governance; Governance network theory; Strategic management; Digital era governance. |

| 21 | [26] | Sustainability | Urban transformation for sustainable communities and environments | Residents, parents, representatives of the administration, local stakeholders | Looper method (using a living lab): Step 1: Problem identification. Step 2: Co-design. Step 3: Action and feedback. |

| 22 | [53] | Education and health | Co-creation of healthy environments in universities | 30 participants (students, services personnel, teachers, administrative staff, researchers) | Step 1: Participation action for selecting ideas. Step 2: Prototyping in teams. Step 3: Evaluation and methodological design. |

| 23 | [54] | Sports | Co-creation of a green sports event brand | Managers Sponsors City is also considered a stakeholder | Step 1: Event strategy. Step 2: Event experience. Step 3: Event brand development. Step 4: Event evaluation. |

| 24 | [55] | Responsive research innovation | A co-creation course for university students | Experts in the domain from academia Experts in the domain of technology End-users Public and private sectors | Course based on the Kolb’s model. Students interact with experts and end-users. Step 1: Active experimentation (doing). Step 2: Concrete experience (feeling). Step 3: Reflective observation (watching). Step 4: Abstract conceptualization (thinking). |

| 25 | [56] | Tourism | Value co-creation in service enterprises for tourism | Shareholders, venture capitalists, customers, suppliers | Step 1: Value conceptualization. Step 2: Value actors. Step 3: Creation platforms. Step 4: Resource planning. Step 5: Learning. Step 6: Value co-creation. Step 7: Co-created value. |

| 26 | [57] | Public health | Evaluation of participatory methodologies. identify a key set of principles and recommendations for co-creating public health interventions | A combination of service providers and end-users | Iterative co-creation process: Step 0. Planning. Step 1. Conducting. Step 2. Reflecting. Step 3. Evaluating. |

| 27 | [58] | Health | Co-creation of a patient workbook | 14 participants | Step 1: Review and synthesize the evidence. Step 2: Individual reflection and small group brainstorming. Step 3: Achieving group consensus. Step 4: Clustering ideas. Step 5: Naming, ordering the clusters. Step 6: Naming the resource. |

| 28 | [59] | Education | Co-creation of a serious game | Researchers and teachers | Step 1: Diagnostic. Step 2: Action planification. Step 3: Action. Step 4: Evaluation. Step 4: Specifications. |

| 29 | [43] | Learning technologies and educational needs | Co-creation of digital stories for children with autism | Academic staff Students | Step 1: Development of the ingredients for the digital stories. Step 2: Co-creation of the digital stories. Step 3: Analysis and conceptualization of the videos as digital stories, and digital stories as evidence. |

| 30 | [60] | Innovation | Framework for creating innovation in the Triple Helix | Academics Practitioners Government Shareholders Other stakeholders | Step 1: Actors’ resources. Step 2: Value proposition. Step 3: Interaction and resource integration. Step 4: Modified resources. |

| 31 | [61] | Semantic web in healthcare | Ontology co-creation | Residential Hospital healthcare | Step 1: Composing a stakeholder group. Step 2: Observations at institutionalized settings of care. Step 3: Workshop type 1: Introducing ontologies. Step 4: Workshop type 2: Scenario role-play. Step 5: Workshop type 3: Decision-making. Step 6: Workshop type 4: Concept evaluation. Step 7: Workshop type 5: Embodied system use. |

| 32 | [62] | Behavioral sciences | Social marketing | Multiple case studies (students, obese people, students, teachers, defense personnel) | Step 1: Co-create. Step 1.1: Stakeholder orientation. Step 1.2: Competition. Step 1.3: Theory. Step 1.4: Segmentation. Step 2: Build—marketing mix. Step 3: Engage. |

| N° | Reference | Research Field | Specific Context of Application | About the Stakeholders | Components/Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [63] | Health | Co-design of patient information sheets | Key providers Consumers | Step 1: Content. Step 2: Communication of content. Step 3: Design. Step 4: Delivery and access. Step 5: Usability. Step 6: Engagement. |

| 2 | [64] | Cooperation and co-design | Design of a cooperative digital solution | Researcher Designers Domain experts | Step 1: Start: Building insight and generating statement representations. Step 2: Move: Horizontal groups and the “move” to design ideas. Step 3: Land: Vertical groups and implementing design ideas in a prototype. |

| 3 | [65] | Community-based participatory research | Design of social resources for immigrants using co-design methods | Immigrants Researchers | Step 1: First co-design workshop. Step 2: Second co-design workshop. Step 3: Consultations with key stakeholders. Step 4: Final co-design workshop. |

| 4 | [66] | Learning and augmented reality | Co-design of augmented reality games | Leader Designers Developers Researchers Teachers Students | Step 1: Training. Step 2: Iterative design (ideating, designing, and developing). Step 3: Evaluation. |

| 5 | [67] | Health | Co-design framework for building coalition in cancer control | Stakeholders involved in the development or delivery of cancer control care, research, and/or policy | Step 1: Engagement. Step 2: Discovery. Step 3: Unification. Step 4: Action. |

| 6 | [68] | Health | Co-design of a virtual health intervention | Patients Clinicians | Step 1: Defining challenges and empathizing. Step 2: Ideating solutions (patients only). Step 3: Individualized virtual onboarding (patients only). Step 4: Virtual prototyping (patients only). Step 5: Further ranking. Step 6: Engineering work (ongoing). Step 6: Engineering work (ongoing). Step 7: Testing. |

| 7 | [69] | Health | Developing a mobile app for older adults using co-design | Older adults Caregivers Care providers | Step 1: Consulting stakeholders, after a scoping review. Step 2: App development and co-designing with older adults. Step 3: Field-testing with older adults. Step 4: Reflecting on lessons learned. |

| 8 | [70] | Health | Co-design of services with young people with mental health problems | Young people Staff Researchers | Step 1: Setting up the project. Step 2: Gathering staff experiences. Step 3: Gathering the experiences of service users. Step 4: Bringing participants together in a co-design event. Step 5: Organizing small groups in which staff and service users. Step 6: Holding an end-of-project celebration event. |

| 9 | [71] | Health | Co-design of a cancer exercises toolkit | 25 exercise professionals | Step 1: needs identification and co-design. Interview. Participants’ screening. Workshop 1 and 2 (capture and understand experience). Workshop 3 (challenges and opportunities). Workshop 4 (improve experience). Step 2: Pilot evaluation. |

| 10 | [72] | Health | Co-design of a framework for remote control cancer care | Patient Caregiver Community | Step 1: Identify. Step 2: Discover. Step 3: Define. Step 4: Ideate. Step 5: Refine. Step 6: Implement. Step 7: Test. |

| 11 | [73] | Cultural heritage | Co-design across cultures | Local people Urban designers Students of design Markers Consumers Providers Researchers | Step 1: Introducing/starting. Step 2: Following/inheriting. Step 3: Changing/transferring. Step 4: Concluding/combining. |

| 12 | [34] | Robotics | Social robot co-design | Domain experts Co-designers | Step 1: Problem space. Step 2: Design guidelines. Step 3: Solution space. |

| 13 | [74] | Health | Co-design of a web-based portal for cardiac rehabilitation | Consumer Researcher Product developer Clinician | Step 1: Workshop design. Step 2: Workshop satisfaction. Step 3: Workshop analysis of the themes. |

| 14 | [75] | Games and education | Framework for the co-design of narrative digital game-based learning | Educators Game developers Co-designers | Step 1: Preparation. Step 2: Co-design. Step 3: Co-specification. Step 4: Development. |

| 15 | [76] | Urban landscape | Co-design of urban landscape | Architects Urban landscape designers Engineers Process managers | Collaborative levels: Collaborative; Participative; Consultive; Informative; Stages. Step 1: Research. Step 2: Analysis. Step 3: Projection. Step 4: Selection. |

| 16 | [77] | Urban landscape | Framework for co-design urban planning | Citizens and other stakeholders | Step 1: Interest and power matrix of actors. Step 2: Exercise booklets for experience registration. Step 3: Sports experience and conditions matrix. Step 4: Online post-its board in the co-design workshop. Step 5: Live sketching in the park and site architectural plans. Step 6: Live collective sketching of spatial layout. Step 7: Diagrams, plans, and renders. Step 8: Sketching in social media visuals. Step 9: Sketching in details and sections. Step 10: Work in progress in social media. Step 11: Plans and renders. Step 12: Photographs in a report. Step 13: Sketches in a printed architectural layout. Step 14: Sketching in sections and details. |

| 17 | [78] | Health | Co-design with Aboriginal community members | Government and non-government service providers Clinicians Managers Coordinators Support services | Step 1: Look and listen. Step 2: Think and reflect. Step 3: Collaborate, consult, and plan. Step 4: Take action. |

| 18 | [79] | Health | Co-design of a psycho-social service for caregivers | Caregivers Local stakeholders | Step 1: Foundation of the service concept. Step 2: Co-design workshops. Step 3: Piloting and preliminary assessment. |

| 19 | [80] | Health | Co-design of healthcare user engagement | Patients Patients’ partners Caregivers Clinicians Healthcare decision-makers | Pre-design Step 1: Contextual inquiry. Step 2: Preparation and training. Co-design Step 3: Framing the issue. Step 4: Generative design. Step 5: Sharing ideas. Post-design Step 6: Data analysis. Step 7: Requirements translation. |

| 20 | [81] | Health | Co-design of expert caregiving interventions | 9 expert caregivers Informal caregivers Professional stakeholders | Step 1: One workshop for recruit participants. Step 2: Establishment of a steering group. Step 3: Establishment of a reference group. Step 4: Planning and co-designing the intervention. Step 5: Discussion and planning after the training course. Step 6: Co-designing procedures for organizing volunteering opportunities. Step 7: Co-designing volunteering opportunities. |

| 21 | [82] | Health | Co-design of a framework for youth mental health | Elders Young people Service staff | Step 1: Engagement. Step 2: Preparation for working together and co-design workshops. Step 3: Clients at headspace center sites. Step 4: Community assessment. |

| 22 | [83] | Education | Co-design of an intervention for inclusion of children in schools | Research team Specialist additional support for learning teachers Classroom teachers Specialist therapists Managers of education and health services Psychologists Medical doctors Parents/carers | Step 1: Gathering feedback on proposals for change. Step 2: Theoretical framework development. Step 3: Developing pencil and paper tools. Step 4: Developing a design specification and building new manual. Step 5: Naturalistic implementation for new materials. |

| 23 | [84] | Health | Human-centered design in the prevention of diabetes in adolescents | Adolescents Parents Professionals | Step 1: Adolescents—patients session 1. Step 2: Adolescents—patients session 2. Step 3: School-based adolescent session. Step 4: Professionals session. |

| 24 | [27] | Sustainability | Co-design of sustainable travel solutions | Participants Researchers Travel experts | Step 1: Problem and context setting. Step 2: Storytelling. Step 3: Problem understanding. Step 4: Idea generation. |

| 25 | [85] | Behavior | Co-design of methods for connecting generations | Children Older adults | Step 1: Pre-design preparation. Step 2: Flexible co-design activities. Step 3: Distributed collaboration. Step 4: Return to co-located design activities. |

| 26 | [29] | Management and public management | Public service design projects | Researchers with backgrounds in service design, marketing, psychology, and social innovation | Step 1: Resourcing. Step 2: Planning. Step 3: Recruiting. Step 4: Sensitizing. Step 5: Facilitating. Step 6: Reflecting. Step 7: Building for change. |

References

- Ramaswamy, V.; Ozcan, K. What Is Co-Creation? An Interactional Creation Framework and Its Implications for Value Creation. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-Creation Experiences: The next Practice in Value Creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Alexander, L.; Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Synnot, A.; Tricco, A.C. Moving from Consultation to Co-Creation with Knowledge Users in Scoping Reviews: Guidance from the JBI Scoping Review Methodology Group. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, E.; Stappers, P. Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.T.; Guo, T.; Han, Z. Co-Design of an Active Suspension Using Simultaneous Dynamic Optimization. J. Mech. Des. 2014, 136, 081003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Huang, S.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Geng, T.; Li, A.; Jiang, W.; Wen, W.; Bi, J.; Liu, H.; et al. A Length Adaptive Algorithm-Hardware Co-Design of Transformer on FPGA Through Sparse Attention and Dynamic Pipelining. In Proceedings of the 59th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 10–14 July 2022; pp. 1135–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery, P.; Saeri, A.K.; Bragge, P. Research Co-Design in Health: A Rapid Overview of Reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Co-Creation for Sustainability: The UN SDGs and the Power of Local Partnership; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-80043-801-9. [Google Scholar]

- Moons, I.; Daems, K.; Van de Velde, L. Co-Creation as the Solution to Sustainability Challenges in the Greenhouse Horticultural Industry: The Importance of a Structured Innovation Management Process. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, E.A.; Adams, R.; Tsetse, E.K.K. Customer Value Co-Creation: Environmental Sustainability as a Tourist Experience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, A.; Monda, A. Sustainable Value Co-Creation and Digital Health: The Case of Trentino eHealth Ecosystem. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, S. Sustainable Value Co-Creation in Business Networks. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 52, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, V.; Mani, V.; Goyal, P. Emerging Trends in the Literature of Value Co-Creation: A Bibliometric Analysis. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Sánchez, J.-J.; Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, M.; Mora-Valentín, E.-M. Mapping Value Co-Creation Literature in the Technology and Innovation Management Field: A Bibliographic Coupling Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 588648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbergen, T.; Adam, M.; Roxburgh, M.; Teubner, T. Co-Design in mHealth Systems Development: Insights From a Systematic Literature Review. AIS Trans. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 13, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, O.; Wallin, J.A. The Bibliometric Analysis of Scholarly Production: How Great Is the Impact? Scientometrics 2015, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, W.; Brimblecombe, A. 2022. Available online: https://www.phrp.com.au/ (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Fellnhofer, K. Toward a Taxonomy of Entrepreneurship Education Research Literature: A Bibliometric Mapping and Visualization. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Antonenko, P.; Wang, J. Trends and Issues in Multimedia Learning Research in 1996–2016: A Bibliometric Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 28, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G. A Bibliometric Analysis of the Top Five Economics Journals During 2012–2016. J. Econ. Surv. 2019, 33, 25–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Sweileh, W.M.; Awang, R.; Al-Jabi, S.W. Global Trends in Research Related to Social Media in Psychology: Mapping and Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wu, L. Trend in H₂S Biology and Medicine Research-A Bibliometric Analysis. Molecules 2017, 22, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Visualizing Bibliometric Networks. In Measuring Scholarly Impact: Methods and Practice; Ding, Y., Rousseau, R., Wolfram, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 285–320. ISBN 978-3-319-10377-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, T.; Huang, J.; Tai, Y.; Trapani, P. How Might We Evaluate Co-Design? A Literature Review on Existing Practices. In Proceedings of the DRS 2022 Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain, 25 June–3 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scanagatta, C.; Condotta, M. The Looper Methodology: Co-Creation Processes for the Built Environment Inclusive and Sustainable Cities [Il Metodo Looper: Processi Di Co-Creazione Per L’ambiente Costruito Comunità Inclusive e Sostenibili]. Sustain. Mediterr. Constr. 2021, 2021, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, V.; Ross, T.; May, A.; Sims, R.; Parker, C. Empirical Investigation of the Impact of Using Co-Design Methods When Generating Proposals for Sustainable Travel Solutions. CoDesign 2016, 12, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Ren, X. Incorporating the Co-Creation Method into Social Innovation Design to Promote Intergenerational Integration: A Case Study of a Public Square. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trischler, J.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Co-Design: From Expert- to User-Driven Ideas in Public Service Design. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 1595–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, P.; Duan, W. Exploration on the Core Elements of Value Co-Creation Driven by AI—Measurement of Consumer Cognitive Attitude Based on Q-Methodology. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 791167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciuliene, M. Evaluation of Open Science for Co-Creation of Social Innovations: A Conceptual Framework. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2022, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, B.; Ashok, M.; Leng Tan, Y. Value Co-Creation in the B2B Context: A Conceptual Framework and Its Implications. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, O.; Malakhtka, E.; Chrobot, N.; Lundqvist, P. End Use Energy Services Framework Co-Creation with Multiple Stakeholders—A Living Lab-Based Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M.; Oliveira, R.; Racca, M.; Kyrki, V. Social Robot Co-Design Canvases: A Participatory Design Framework. J. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2021, 11, 3:1–3:39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbguth, J.; Schörling, M.; Birt, N.; Bongers, S.; Sulzberger, P.; Morin, J.-H. Co-Creating Innovation for Sustainability. Gr. Interakt. Organ. 2022, 53, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavouras, I.; Sardis, E.; Protopapadakis, E.; Rallis, I.; Doulamis, A.; Doulamis, N. A Low-Cost Gamified Urban Planning Methodology Enhanced with Co-Creation and Participatory Approaches. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Spais, G.S.; Jain, V. A Proposed Framework of Market-Oriented Ethnography (MOE) Approach to Study Co-Creation of Content Through Product Storytelling. J. Promot. Manag. 2023, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormer, L.; Schindler, T.; Williams, L.A.; Lobban, D.; Khawaja, S.; Hunn, A.; Ubilla, D.L.; Sargeant, I.; Hamoir, A.-M. A Practical ‘How-To’ Guide to Plain Language Summaries (PLS) of Peer-Reviewed Scientific Publications: Results of a Multi-Stakeholder Initiative Utilizing Co-Creation Methodology. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2022, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casiano Flores, C.; Rodriguez Müller, A.P.; Virkar, S.; Temple, L.; Steen, T.; Crompvoets, J. Towards a Co-Creation Approach in the European Interoperability Framework. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2022, 16, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mas, L.; Claret, A.; Stancu, V.; Brunsø, K.; Peral, I.; Santa Cruz, E.; Krystallis, A.; Guerrero, L. Making Full Use of Qualitative Data to Generate New Fish Product Ideas through Co-Creation with Consumers: A Methodological Approach. Foods 2022, 11, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergerød, I.J.; Clay-Williams, R.; Wiig, S. Developing Methods to Support Collaborative Learning and Co-Creation of Resilient Healthcare—Tips for Success and Lessons Learned From a Norwegian Hospital Cancer Care Study. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, F.; Seys, D.; Brouwers, J.; Wilder, A.V.; Jans, A.; Castro, E.M.; Bruyneel, L.; Ridder, D.D.; Vanhaecht, K. A Co-Creation Roadmap towards Sustainable Quality of Care: A Multi-Method Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, V.; Parsons, S.; Kovshoff, H.; Crump, B. Co-Creation of Research and Design During a Coding Club With Autistic Students Using Multimodal Participatory Methods and Analysis. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 864362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, K.; Pizzolato, D.; Stappers, P.J.; Evans, N.; Lechner, I.; Widdershoven, G.; Bouter, L.; Dierickx, K.; Bergema, K.; Tijdink, J. Using Co-Creation Methods for Research Integrity Guideline Development—How, What, Why and When? Account. Res. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezaro, S.; Jenkins, M.; Bollard, M. Defining ‘Research Inspired Teaching’ and Introducing a Research Inspired Online/Offline Teaching (Riot) Framework for Fostering It Using a Co-Creation Approach. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 108, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Scheller, D.; Schröder, S. Co-Creation in Citizen Social Science: The Research Forum as a Methodological Foundation for Communication and Participation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cearra, J.; Saiz-Santos, M.; Barrutia, J. An Empiric Experience Implementing a Methodology to Improve the Entrepreneurial Support System: Creating Social Value Through Collaboration and Co-Creation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 728387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulvenblad, P.; Barth, H. Liability of Smallness in SMEs—Using Co-Creation as a Method for the ‘Fuzzy Front End’ of HRM Practices in the Forest Industry. Scand. J. Manag. 2021, 37, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font Barnet, A.; Boqué Ciurana, A.; Olano Pozo, J.X.; Russo, A.; Coscarelli, R.; Antronico, L.; De Pascale, F.; Saladié, Ò.; Anton-Clavé, S.; Aguilar, E. Climate Services for Tourism: An Applied Methodology for User Engagement and Co-Creation in European Destinations. Clim. Serv. 2021, 23, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Paio, A. LABTUR: Una contribución metodológica a las prácticas de co-creación del espacio público. LABTUR Methodol. Contrib. Pract. Co-Creat. Public Space 2021, 16, 9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.D.; Gokhberg, L.; Meissner, D.; Russo, M. Addressing Societal Challenges through the Simultaneous Generation of Social and Business Values: A Conceptual Framework for Science-Based Co-Creation. Technovation 2021, 104, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, J.; Ferlie, E.; Jukić, T.; Ongaro, E. A Theoretical Framework for Studying the Co-Creation of Innovative Solutions and Public Value. Policy Politics 2021, 49, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazorco-Salas, J.E.; Rojas-León, G.A.; Gómez-Romero, R.F.; Duarte-Rueda, J.R.; Granados-Mendoza, M.C. Design of a Methodology for the Co-Creation of Health Environments in University Educational Contexts. Hacia La Promoción De La Salud 2021, 26, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, R.; Naess, H.E. Toward a Co-Creation Framework for Developing a Green Sports Event Brand: The Case of the 2018 Zürich E Prix. J. Sport Tour. 2021, 25, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, E.I.; Petsani, D.; Bamidis, P.D. Teaching University Students Co-Creation and Living Lab Methodologies through Experiential Learning Activities and Preparing Them for RRI. Health Inform. J. 2021, 27, 1460458221991204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, F.; Shams Gharneh, N.; Khajeheian, D. A Conceptual Framework for Value Co-Creation in Service Enterprises (Case of Tourism Agencies). Sustainability 2020, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Cardon, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verloigne, M.; Sebastien F. M. Chastin on behalf of the GrandStand, Safe Step and Teenage Girls on the Move Research Groups. Framework, Principles and Recommendations for Utilising Participatory Methodologies in the Co-Creation and Evaluation of Public Health Interventions. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2019, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minian, N.; Noormohamed, A.; Zawertailo, L.; Baliunas, D.; Giesbrecht, N.; Le Foll, B.; Rehm, J.; Samokhvalov, A.; Selby, P.L. A Method for Co-Creation of an Evidence-Based Patient Workbook to Address Alcohol Use When Quitting Smoking in Primary Care: A Case Study. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2018, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Espinosa, R.S.; Eguia-Gómez, J.L.; Albajes, L.S. Involving Elementary Teachers in the Design of a Serious Game through Action-Research Methodology and Co-Creation [Involucrando a Profesores de Primaria En El Diseño de Un Juego Serio Mediante La Metodología Investigación-Acción y Co-Creación]. RISTI—Rev. Iber. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2016, 2016, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. Co-Creation: Moving towards a Framework for Creating Innovation in the Triple Helix. Prometheus 2014, 32, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongenae, F.; Duysburgh, P.; Sulmon, N.; Verstraete, M.; Bleumers, L.; De Zutter, S.; Verstichel, S.; Ackaert, A.; Jacobs, A.; De Turck, F. An Ontology Co-Design Method for the Co-Creation of a Continuous Care Ontology. Appl. Ontol. 2014, 9, 27–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle-Thiele, S.; Dietrich, T.; Carins, J. CBE: A Framework to Guide the Application of Marketing to Behavior Change. Soc. Mark. Q. 2021, 27, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biezen, R.; Ciavarella, S.; Manski-Nankervis, J.-A.; Monaghan, T.; Buising, K. Addressing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care—Developing Patient Information Sheets Using Co-Design Methodology. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çarçani, K.; Bratteteig, T.; Holone, H.; Herstad, J. EquiP: A Method to Co-Design for Cooperation. Comput. Support. Coop. Work 2023, 32, 385–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan Zhao, I.; Holroyd, E.; Garrett, N.; Neville, S.; Wright-st Clair, V.A. Using Co-Design Methods With Chinese Late-Life Immigrants to Translate Mixed-Method Findings to Social Resources. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231157704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobar-Muñoz, H.; Baldiris, S.; Fabregat, R. Co-Design of Augmented Reality Games for Learning with Teachers: A Methodological Approach. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2023, 28, 901–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, A.; Chan, B.; Moodie, R.; Varlow, M.; Bates, C.; Foliaki, S.; Palafox, N.; Burich, S.; Aranda, S. Strengthening Cancer Control in the South Pacific through Coalition-Building: A Co-Design Framework. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2023, 33, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isakadze, N.; Molello, N.; MacFarlane, Z.; Gao, Y.; Spaulding, E.M.; Mensah, Y.C.; Marvel, F.A.; Khoury, S.; Marine, J.E.; Michos, E.D.; et al. The Virtual Inclusive Digital Health Intervention Design to Promote Health Equity (iDesign) Framework for Atrial Fibrillation: Co-Design and Development Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2022, 9, e38048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, C.; Kernoghan, A.; Lemmon, K.; Fernandes, P.; Elliott, J.; Sacco, V.; Bodemer, S.; Stolee, P. Lessons and Reflections From an Extended Co-Design Process Developing an mHealth App With and for Older Adults: Multiphase, Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e39189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girling, M.; Couteur, A.L.; Finch, T. Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) with Young People Who Offend: Innovating Methodology to Reach Marginalised Groups. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennett, A.M.; Tang, C.Y.; Chiu, A.; Osadnik, C.; Granger, C.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Campbell, K.L.; Barton, C. A Cancer Exercise Toolkit Developed Using Co-Design: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Cancer 2022, 8, e34903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronoff-Spencer, E.; McComsey, M.; Chih, M.-Y.; Hubenko, A.; Baker, C.; Kim, J.; Ahern, D.K.; Gibbons, M.C.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Nyakairu, P.; et al. Designing a Framework for Remote Cancer Care Through Community Co-Design: Participatory Development Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e29492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan-Kinns, N.; Wang, W.; Ji, T. Qi2He: A Co-Design Framework Inspired by Eastern Epistemology. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2022, 160, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, K.; Beleigoli, A.; Du, H.; Tirimacco, R.; Clark, R.A. User Experience (UX) Design as a Co-Design Methodology: Lessons Learned during the Development of a Web-Based Portal for Cardiac Rehabilitation. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 21, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breien, F.; Wasson, B. eLuna: A Co-Design Framework for Narrative Digital Game-Based Learning That Support STEAM. Front. Educ. 2022, 6, 775746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete Cruz, M.; Ersoy, A.; Czischke, D.; van Bueren, E. Towards a Framework for Urban Landscape Co-Design: Linking the Participation Ladder and the Design Cycle. CoDesign 2023, 19, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete, M.; Ersoy, A.; Czischke, D.; Bueren, E. van A Framework for Co-Design Processes and Visual Collaborative Methods: An Action Research Through Design in Chile. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmil, H.; Kelly, J.; Bowden, M.; Galletly, C.; Cairney, I.; Wilson, C.; Hahn, L.; Liu, D.; Elliot, P.; Else, J.; et al. Participatory Action Research-Dadirri-Ganma, Using Yarning: Methodology Co-Design with Aboriginal Community Members. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graffigna, G.; Gheduzzi, E.; Morelli, N.; Barello, S.; Corbo, M.; Ginex, V.; Ferrari, R.; Lascioli, A.; Feriti, C.; Masella, C. Place4Carers: A Multi-Method Participatory Study to Co-Design, Piloting, and Transferring a Novel Psycho-Social Service for Engaging Family Caregivers in Remote Rural Settings. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, M.; McGillion, M.; Chambers, E.M.; Dix, J.; Fajardo, C.J.; Gilmour, M.; Levesque, K.; Lim, A.; Mierdel, S.; Ouellette, C.; et al. A Generative Co-Design Framework for Healthcare Innovation: Development and Application of an End-User Engagement Framework. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2021, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åkerman, S.; Nyqvist, F.; Coll-Planas, L.; Wentjärvi, A. The Expert Caregiver Intervention Targeting Former Caregivers in Finland: A Co-Design and Feasibility Study Using Mixed Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.; Brown, A.; Dudgeon, P.; McPhee, R.; Coffin, J.; Pearson, G.; Lin, A.; Newnham, E.; Baguley, K.K.; Webb, M.; et al. Our Journey, Our Story: A Study Protocol for the Evaluation of a Co-Design Framework to Improve Services for Aboriginal Youth Mental Health and Well-Being. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciver, D.; Hunter, C.; Johnston, L.; Forsyth, K. Using Stakeholder Involvement, Expert Knowledge and Naturalistic Implementation to Co-Design a Complex Intervention to Support Children’s Inclusion and Participation in Schools: The CIRCLE Framework. Children 2021, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, J.M.; Moore, C.M.; Yazel, L.G.; Lynch, D.O.; Haberlin-Pittz, K.M.; Wiehe, S.E.; Hannon, T.S. Diabetes Prevention in Adolescents: Co-Design Study Using Human-Centered Design Methodologies. J. Particip. Med. 2021, 13, e18245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Druin, A.; Fails, J.; Massey, S.; Golub, E.; Franckel, S.; Schneider, K. Connecting Generations: Developing Co-Design Methods for Older Adults and Children. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2012, 31, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Document | Co-Design | Co-Creation |

|---|---|---|

| Article | 2180 | 2227 |

| Conference paper | 1469 | 787 |

| Book chapter | 113 | 374 |

| Review | 56 | 91 |

| Editorial | 20 | 25 |

| Book | 17 | 11 |

| Short survey | 3 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avila-Garzon, C.; Bacca-Acosta, J. Thirty Years of Research and Methodologies in Value Co-Creation and Co-Design. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062360

Avila-Garzon C, Bacca-Acosta J. Thirty Years of Research and Methodologies in Value Co-Creation and Co-Design. Sustainability. 2024; 16(6):2360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062360

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvila-Garzon, Cecilia, and Jorge Bacca-Acosta. 2024. "Thirty Years of Research and Methodologies in Value Co-Creation and Co-Design" Sustainability 16, no. 6: 2360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062360

APA StyleAvila-Garzon, C., & Bacca-Acosta, J. (2024). Thirty Years of Research and Methodologies in Value Co-Creation and Co-Design. Sustainability, 16(6), 2360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062360