Drivers of Student Social Entrepreneurial Intention Amid the Economic Crisis in Lebanon: A Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Entrepreneurial Education and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

2.2. Entrepreneurial Passion and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

2.3. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Social Entrepreneurial Intentions

2.4. Moral Obligation and Social Entrepreneurial Intentions

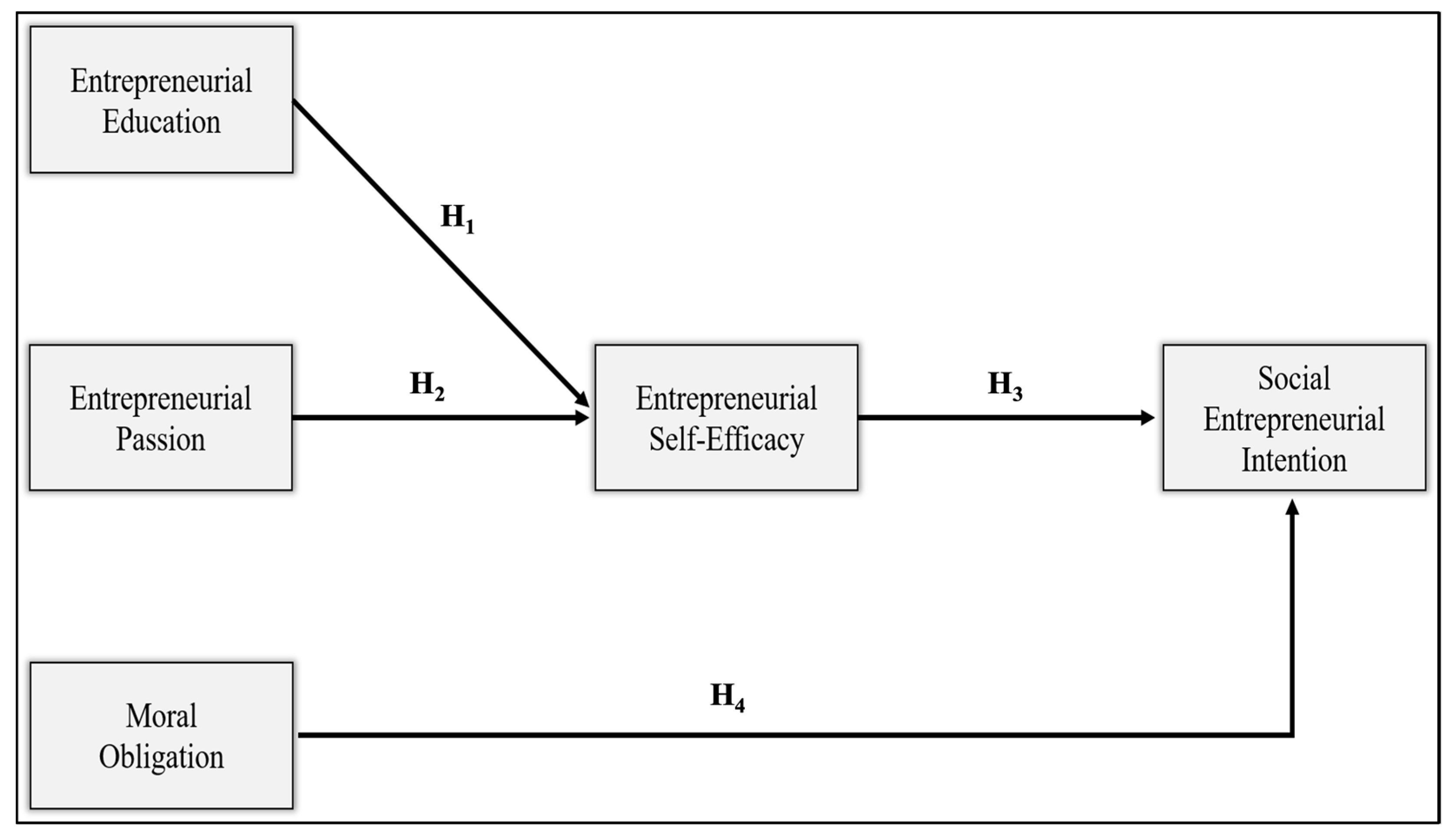

2.5. Conceptual Framework

3. Research Design

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

4. Analysis

4.1. Results

4.2. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

6. Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Entrepreneurial Education (Jiatong et al., 2021) [84] | ||||||

| 1. | The entrepreneurial education model in our school/university promotes creative ideas (EE1). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. | The learning model in the classroom provides us with the required knowledge toward entrepreneurship (EE2). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. | The education in school/university drives our skill and ability related to entrepreneurship (EE3). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. | The education activities incorporate entrepreneurship matter and allow opportunities for us to begin a business (EE4). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. | I think that the opportunity to enlarge entrepreneurship occasion is greater in the presence of education activities (EE5). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Entrepreneurial Passion (Li et al., 2020) [6] | ||||||

| 6. | It is exciting to figure out new ways to solve unmet market needs that can be commercialized (EP1). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. | Searching for new ideas for products/services to offer is enjoyable to me (EP2). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. | I am motivated to figure out how to make existing products/services better (EP3). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. | Scanning the environment for new opportunities really excites me (EP4). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 10. | Inventing new solutions to problems is an important part of who I am (EP5). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Moral Obligation (Hockerts, 2017) [12] | ||||||

| 11. | It is an ethical responsibility to help people less fortunate than ourselves (MO1). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 12. | We are morally obliged to help socially disadvantaged people (MO2). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 13. | Social justice requires that we help those who are less fortunate than ourselves (MO3). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 14. | It is one of the principles of our society that we should help socially disadvantaged people (MO4). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (Samsudin et al., 2022) [85] | ||||||

| 15. | I am convinced that I can personally make a contribution to address societal challenges (ESE1). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 16. | I could figure out a way to help solve the problems that society faces (ESE2). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 17. | Solving societal problems is something each of us can contribute to (ESE3). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 18. | I believe it would be possible for me to bring about significant social change (ESE4). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 19. | I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities (ESE5). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 20. | I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events (ESE6). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 21. | I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough (ESE7). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Social Entrepreneurial intention (Hockerts, 2017). [12] | ||||||

| 22. | I expect that at some point in the future I will be involved in launching a business that aims to solve social problems (SEI1). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 23. | I have a preliminary idea for a social enterprise on which I plan to act in the future (SEI2). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 24. | I do plan to start a social enterprise (SEI3). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

References

- Wang, L.; Shao, J. Digital economy, entrepreneurship and energy efficiency. Energy 2023, 269, 126801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J.; Baregheh, A.; Sambrook, S. Towards an innovation-type mapping tool. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Mitre-Aranda, M.; del Brío-González, J. The entrepreneurial intention of university students: An environmental perspective. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.E.; Vyakarnam, S.; Volkmann, C.; Mariotti, S.; Rabuzzi, D. Educating the Next Wave of Entrepreneurs: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Capabilities to Meet the Global Challenges of the 21st century. World Economic Forum: A Report of the Global Education Initiative. 2009. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1396704 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Neneh, B.N. From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Murad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Khan, M.A.S.; Ashraf, S.F.; Dogbe, C.S.K. Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwani, R.D.; Kirsch, D.; Welter, F.; Gartner, W.B.; Jones, G.G. Context, time, and change: Historical approaches to entrepreneurship research. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhouche, A. Assessing the innovation-finance nexus for SMEs: Evidence from the Arab Region (MENA). J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 1875–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatavu, S.; Dogaru, M.; Moldovan, N.C.; Lobont, O. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic development through government policies and citizens’ attitudes. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 1604–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.; Ciloci, R. The Entrepreneurship Osmosis in Relation to Economic Growth’s Conceptual Framework. USV Ann. Econ. Public Adm. 2023, 22, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hockerts, K. Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petuskiene, E.; Glinskiene, R. Entrepreneurship as the basic element for the successful employment of benchmarking and business innovations. Econ. Manag. 2011, 22, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.F.; Fayolle, A. Bridging the entrepreneurial intention–behaviour gap: The role of commitment and implementation intention. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2015, 25, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; McGowan, P. Rethinking competition-based entrepreneurship education in higher education institutions: Towards an effectuation-informed coopetition model. Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farny, S.; Frederiksen, S.H.; Hannibal, M.; Jones, S. A CULTure of entrepreneurship education. In Institutionalization of Entrepreneurship Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Potishuk, V.; Kratzer, J. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial attitudes in higher education. J. Entrep. Educ. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, I.K.; Khan, M.K.; Mwakapesa, D.S. Factors determining the entrepreneurial intentions among Chinese university students: The moderating impact of student internship motivation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, D.D. Social Entrepreneurship Teaching Resources Handbook. 2008. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/11866932/Social_Entrepreneurship_Teaching_Resources_Handbook (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Miller, T.L.; Grimes, M.G.; McMullen, J.S.; Vogus, T.J. Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 616–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandan, M.; Scott, P.A. Social entrepreneurship and social work: The need for a transdisciplinary educational model. Adm. Soc. Work 2013, 37, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemari, M.A.; Kasuma, J.; Kamaruddin, H.M.; Tama, H.A.; Morshidi, I.; Suria, K. Relationship between human capital and social capital towards social entrepreneurial intention among the public university students. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2017, 4, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N. The distinctive challenge of educating social entrepreneurs: A postscript and rejoinder to the special issue on entrepreneurship education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2007, 6, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, W.A.; Cooper, S.Y. Enhancing Self-Efficacy to Enable Entrepreneurship: The Case of CMI’s Connections. 2004. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5175386_Enhancing_Self-Efficacy_to_Enable_Entrepreneurship_The_Case_of_CMI's_Connections (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marlino, D. Gender, entrepreneurial self–efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumojanto, D.D.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Wibowo, A. Does entrepreneurial education drive students’ being entrepreneurs? Evidence from Indonesia. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, L.W.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Wibowo, A.; Mahendra, A.M.; Wibowo, N.A.; Harwida, G.; Rohman, A.N. The impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset: The mediating role of attitude and self-efficacy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, B.; Liu, Y.; Bajaba, S.; Marler, L.E.; Pratt, J. Examining how the personality, self-efficacy, and anticipatory cognitions of potential entrepreneurs shape their entrepreneurial intentions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 125, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Lee, C.H.; Xiang, Y. Entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial intention in higher education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, UK, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory goes global. In The Psychologist; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Malebana, M.J.; Swanepoel, E. The relationship between exposure to entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial self-effi cacy. S. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2014, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette, E.M.; Radu Lefebvre, M.; Brunel, O. The impact of story bound entrepreneurial role models on self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M.E.; Mitchell, T.R. Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1992, 17, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Zietsma, C.; Saparito, P.; Matherne, B.P.; Davis, C. A tale of passion: New insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood metaphor. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Kirk, C.P. Entrepreneurial passion as mediator of the self–efficacy to persistence relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Wincent, J.; Singh, J.; Drnovsek, M. The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C.; Mageau, G.A.; Koestner, R.; Ratelle, C.; Léonard, M.; Gagné, M.; Marsolais, J. Les passions de l’ame: On obsessive and harmonious passion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Gregoire, D.A.; Stevens, C.E.; Patel, P.C. Measuring entrepreneurial passion: Conceptual foundations and scale validation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnieks, C.Y.; Mosakowski, E.; Cardon, M.S. Pathways of passion: Identity centrality, passion, and behavior among entrepreneurs. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1583–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroe, S.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. Effectuation or causation: An fsQCA analysis of entrepreneurial passion, risk perception, and self-efficacy. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drnovšek, M.; Slavec, A.; Cardon, M.S. Cultural context, passion and self-efficacy: Do entrepreneurs operate on different ‘planets’? In Handbook of Entrepreneurial Cognition; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 227–253. [Google Scholar]

- Dalborg, C.; Wincent, J. The idea is not enough: The role of self-efficacy in mediating the relationship between pull entrepreneurship and founder passion–a research note. Int. Small Bus. J. 2015, 33, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biraglia, A.; Kadile, V. The role of entrepreneurial passion and creativity in developing entrepreneurial intentions: Insights from American homebrewers. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Yazdanpanah, J. Novice entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and passion for entrepreneurship. In Iranian Entrepreneurship: Deciphering the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Iran and in the Iranian Diaspora; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, J.R.; Locke, E.A. The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, N., Jr.; Dickson, P.R. How believing in ourselves increases risk taking: Perceived self-efficacy and opportunity recognition. Decis. Sci. 1994, 25, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K. The social entrepreneurial antecedents scale (SEAS): A validation study. Soc. Enterp. J. 2015, 11, 260–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B. Entrepreneurial alertness, self-efficacy and social entrepreneurship intentions. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, H.; Wei, C.W.; Zheng, C. Sharing achievement and social entrepreneurial intention: The role of perceived social worth and social entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 2737–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K. Role of University Entrepreneurial Ecosystem and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy in Shaping Entrepreneurial Intention: A Study of Indian Students. In Promoting Entrepreneurship to Reduce Graduate Unemployment; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H.; Chang, C.C.; Yao, S.N.; Liang, C. The contribution of self-efficacy to the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention. High. Educ. 2016, 72, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, S.D.; Gerhardt, M.W.; Kickul, J.R. The role of cognitive style and risk preference on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2007, 13, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.E.; Peterson, M.; Mueller, S.L.; Sequeira, J.M. Entrepreneurial self–efficacy: Refining the measure. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiri, J.K.; Kungu, K.; Dilbeck, M. Predictors of entrepreneurial intentions and social entrepreneurial intentions: A look at proactive personality, self-efficacy and creativity. J. Bus. Divers. 2019, 19, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Wang, H.; Zheng, C.; Wu, Y.J. Effect of narcissism, psychopathy, and machiavellianism on entrepreneurial intention—The mediating of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J.; Linder, S. Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Noboa, E. Social Entrepreneurship: How Intentions to Create a Social Venture Are Formed; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K.; Mair, J.; Robinson, J. (Eds.) Values and Opportunities in Social Entrepreneurship; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.P.; Le, A.N.H.; Xuan, L.P. A systematic literature review on social entrepreneurial intention. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 11, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.J.; Kim, K. Connecting founder social identity with social entrepreneurial intentions. Soc. Enterp. J. 2020, 16, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J.R. Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Brenkert, G.G. Entrepreneurship, ethics, and the good society. Ruffin Ser. Soc. Bus. Ethics 2002, 3, 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Schindehutte, M.; Walton, J.; Allen, J. The ethical context of entrepreneurship: Proposing and testing a developmental framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 40, 331–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.D. Entrepreneurship as economics with imagination. Ruffin Ser. Soc. Bus. Ethics 2002, 3, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, S. Stakeholder value equilibration and the entrepreneurial process. Ruffin Ser. Soc. Bus. Ethics 2002, 3, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.A. Personal values as a catalyst for corporate social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 60, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M. The economic and non-economic dimensions of social entreprises’ moral discourse: An issue of axiological and philosophical coherence. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Kautonen, T. The moral legitimacy of entrepreneurs: An analysis of early-stage entrepreneurship across 26 countries. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe Hwee Nga, J.; Shamuganathan, G. The influence of personality traits and demographic factors on social entrepreneurship start up intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. IJEC 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.J.; Troth, A.C. Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiatong, W.; Murad, M.; Bajun, F.; Tufail, M.S.; Mirza, F.; Rafiq, M. Impact of entrepreneurial education, mindset, and creativity on entrepreneurial intention: Mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 724440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, N.; Ramdan, M.R.; Abd Razak, A.Z.A.; Mohamad, N.; Yaakub, K.B.; Abd Aziz, N.A.; Hanafiah, M.H. Related Factors in Undergraduate Students’ Motivation towards Social Entrepreneurship in Malaysia. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 1657–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Beaman, J.; Sponarski, C.C. Rethinking internal consistency in Cronbach’s alpha. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Alt, E. Feeling capable and valued: A prosocial perspective on the link between empathy and social entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statements/Indicators | Standardized Loadings | CR | α | Rho A | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Education (EE) | |||||

| EE1 | 0.729 | 0.933 | 0.801 | 0.827 | 0.584 |

| EE2 | 0.905 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.811 | ||||

| EE4 | 0.732 | ||||

| EE5 | 0.575 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Passion (EP) | |||||

| EP1 | 0.827 | 0.836 | 0.749 | 0.751 | 0.625 |

| EP2 | 0.752 | ||||

| EP3 | 0.869 | ||||

| EP4 | 0.755 | ||||

| EP5 | 0.804 | ||||

| Moral Obligation (MO) | |||||

| MO1 | 0.835 | 0.935 | 0.789 | 0.831 | 0.755 |

| MO2 | 0.945 | ||||

| MO3 | 0.768 | ||||

| MO4 | 0.773 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE) | |||||

| ESE1 | 0.874 | 0.921 | 0.735 | 0.742 | 0.707 |

| ESE2 | 0.655 | ||||

| ESE3 | 0.928 | ||||

| ESE4 | 0.939 | ||||

| ESE5 | 0.804 | ||||

| ESE6 | 0.807 | ||||

| ESE7 | 0.760 | ||||

| Social Entrepreneurial Intention (SEI) | |||||

| SEI1 | 0.754 | 0.906 | 0.862 | 0.884 | 0.678 |

| SEI2 | 0.793 | ||||

| SEI3 | 0.878 | ||||

| EE | EP | MO | ESE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | ||||

| EP | 0.523 | |||

| MO | 0.422 | 0.377 | ||

| ESE | 0.459 | 0.319 | 0.217 | |

| SEI | 0.512 | 0.485 | 0.538 | 0.506 |

| Effects | Relations | β | t-Statistics | Ƒ2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EE → ESE | 0.216 | 4.678 *** | 0.128 | Supported |

| H2 | EP → ESE | 0.374 | 5.731 *** | 0.143 | Supported |

| H3 | ESE → SEI | 0.212 | 2.742 ** | 0.077 | Supported |

| H4 | MO → SEI | 0.318 | 5.695 *** | 0.145 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toufaily, B.; Bou Zakhem, N. Drivers of Student Social Entrepreneurial Intention Amid the Economic Crisis in Lebanon: A Mediation Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072807

Toufaily B, Bou Zakhem N. Drivers of Student Social Entrepreneurial Intention Amid the Economic Crisis in Lebanon: A Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2024; 16(7):2807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072807

Chicago/Turabian StyleToufaily, Batoul, and Najib Bou Zakhem. 2024. "Drivers of Student Social Entrepreneurial Intention Amid the Economic Crisis in Lebanon: A Mediation Model" Sustainability 16, no. 7: 2807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072807

APA StyleToufaily, B., & Bou Zakhem, N. (2024). Drivers of Student Social Entrepreneurial Intention Amid the Economic Crisis in Lebanon: A Mediation Model. Sustainability, 16(7), 2807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072807