Abstract

This study explores how the layout of neighborhoods in traditional settlements of Saudi Arabia’s Najdi region influence social interactions and urban planning decisions. The study uses a multidisciplinary approach that includes urban morphology, architectural phenomenology, and sociological study methods to investigate the relationships between spatial organization and decision-making processes on both the macro and micro levels of decision-making. The purpose is to look at how collective action decision-making processes affect the urban fabric and how social norms influence spatial organization at different levels. The study applies case study and spatial analysis approaches to investigate how the traditional settlements’ spatial structure promotes peace among the inhabitants while also sustaining cultural traditions. The qualitative approach investigates how spatial arrangements influence behaviors, developing a better understanding of how residents interact with their surroundings. According to the study’s findings, these spatial layouts sustain customs and assist communities in adapting to environmental changes by retaining cultural activities. The study identifies the significance of balancing development with the retention of important traditional values in the implementation of long-term urban conservation plans. Traditional Najdi towns can serve as urban design examples, emphasizing the need to acknowledge the distinct value of vernacular architecture in modern urban development while also fostering social cohesion.

1. Introduction

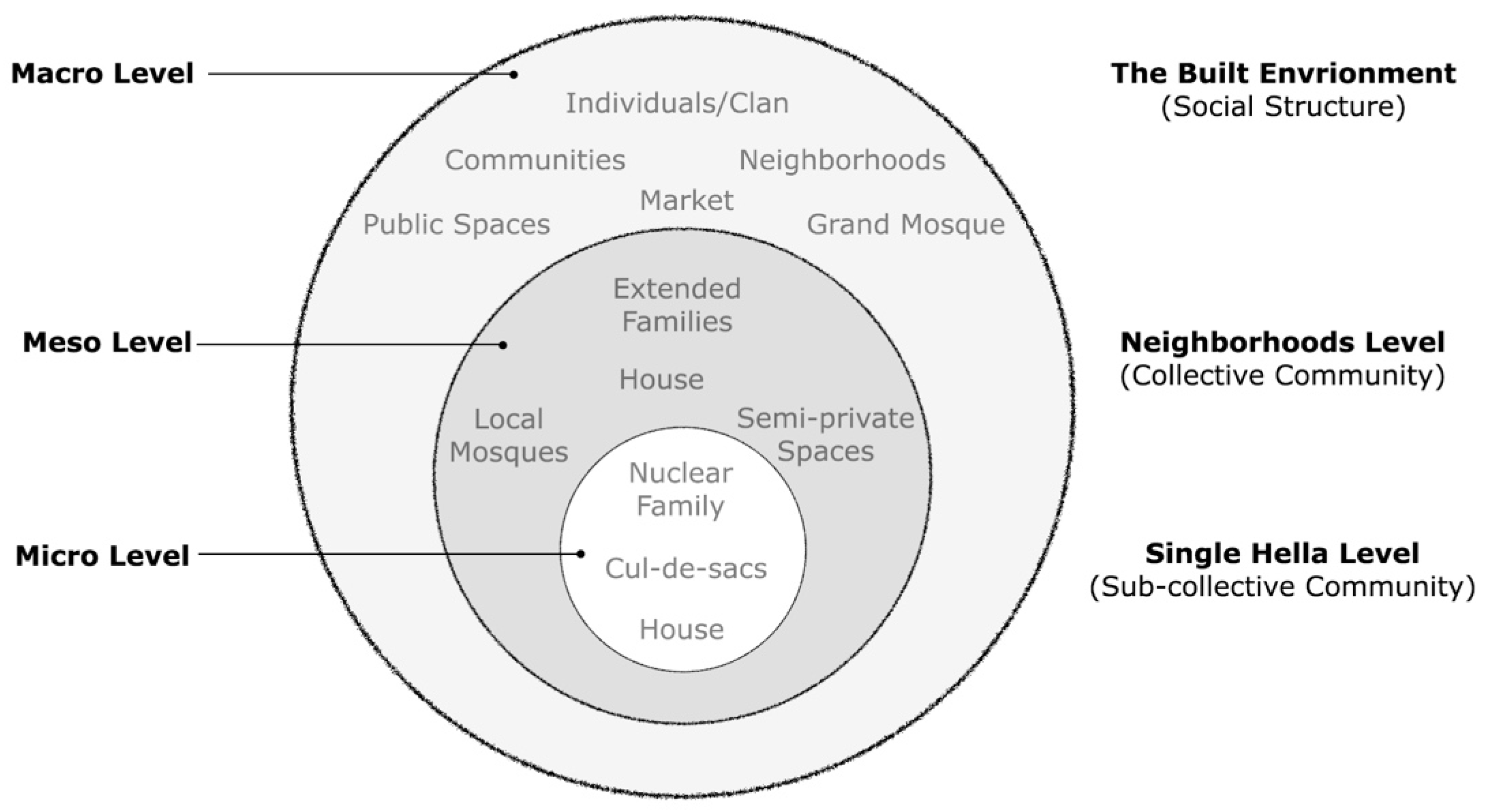

The physical and social complexities of traditional Najdi towns in Saudi Arabia is a cultural phenomenon. The traditional urban neighborhood is known as a ‘hella’ in Arabic. This study examines how the specific spatial arrangements inside these communities influence social structures, inform decision-making processes, and drive urban morphology, three influences that converge to form the urban fabric of traditional Nadji towns. Examining the complexity of the urban fabric from these three perspectives provides unique insights into the relationship between spatial organization and social order.

The hella represents a logical, organizational physical and social unit that embodies decision-making in daily life. By exploring the social dimensions of the hella and analyzing how different components of neighborhoods shape the form and community dynamics, this study takes an interdisciplinary approach, employing urban morphology, architectural phenomenology, and sociological study methods. The study focuses on developing an understanding of decision-making mechanisms at the individual, neighborhood, and settlement levels, while emphasizing the role of neighborhoods in creating an adaptable urban fabric in the Najdi region.

The focus of the study on the formation of neighborhoods involves understanding their complex socio-spatial structures. Traditional Arab neighborhoods, such as those found in the Najdi region of Saudi Arabia, are characterized by their exquisitely intricate urban fabric, which is closely linked to social, cultural, and environmental influences [1]. These neighborhoods are formed through a combination of organic growth and planned interventions, reflecting shared, strongly-held communal values and the hierarchical social structure of the region [2]. The physical layout of the built environment emphasizes privacy, community interaction, and adaptation to the harsh desert environment, featuring narrow streets, shaded pathways, and enclosed courtyards. This spatial organization not only facilitates climate adaptability and social cohesion but also represents the tangible manifestation of Islamic principles and local customs in urban planning as well as individual and small group decisions [3]. By integrating these elements, traditional Arab neighborhoods generally and the Nadji traditional settlements specifically offer a holistic model for understanding the dynamics of urban morphology and social order in vernacular architecture.

This study focused on evaluating and comprehending the relationships between the spatial layouts and social structures of traditional Najdi towns, with a particular emphasis on how neighborhood clusters, i.e., hella, influence urban planning and community decision-making. The study’s goal is to examine the collective action decision-making processes on the urban fabric and how social norms influence the spatial organization at various levels. By examining the integration of ‘tangible’ architectural designs and ‘intangible’ social customs, the study highlights the sustainable urban planning principles inherent in traditional architecture and provides insights into the adaptive strategies employed by communities to foster social cohesion and resilience in a challenging environment.

The study’s objectives are multi-faceted, which include (1) an examination of the spatial hierarchy’s influence on community decision-making, (2) how the physical architecture of the hella influences the social interactions of its inhabitants and reinforces community dynamics, (3) the investigation of the dual decision-making processes in these traditional contexts by emphasizing the importance of both visible and virtual boundaries that define metropolitan areas, and (4) stress on the difficulties of combining urban expansion with traditional values, arguing for conservation measures that respect the cultural and architectural legacy of traditional Nadji settlements.

As a result, the research questions proposed in the study outline the study objectives and derive the methodology utilized to investigate various essential elements of traditional Najdi settlements. These inquiries look into the effects of spatial hierarchy on decision-making, the methods that traditional neighborhoods use to support collective decision-making and sustain social norms, and the hella’s (neighborhood’s) function in urban morphology. Furthermore, this study examines how hidden (‘virtual’) borders within the urban fabric affect social cohesiveness and the preservation of traditional values as well as the best methods for integrating modern urban projects with old structures. Finally, this study examines how the spatial and social structure of Najdi communities can provide useful lessons for sustainable urban design and architecture, perhaps serving as a new paradigm for resilience and adaptability in urban planning.

The study’s goal, with this line of inquiry, is to shed light on conventional, architecture-based urban planning concepts while also making meaningful contributions to discussions related to sustainable urban development and cultural preservation. Through a multidisciplinary approach, this study contributes, within the broader context of sustainable urban development and heritage conservation, to the understanding of traditional settlements as models of resilience and adaptability.

2. Literature Review

Traditional Arab neighborhoods are steeped in a history that incorporates the principles of Islam into urban planning. The Islamic principles are informed by Islamic teaching. The layout of these neighborhoods reflects a deliberate design aimed at fulfilling both social and religious needs, as well as promoting community cohesion while adhering to the shared communal values of privacy and modesty. Researchers have noted the significant influence of Islamic teachings on the configuration of urban spaces in traditional Arab neighborhoods, which prioritize family-centric living environments and communal interactions within defined spatial boundaries [4,5,6]. This historical backdrop is crucial for understanding the foundational elements that shape the morphology and ethos of these neighborhoods.

The architectural and urban planning aspects of traditional Arab neighborhoods exhibit a distinctive morphology characterized by narrow winding streets, cul-de-sacs, and clustered housing. This design strategy is not only a response to climatic conditions, offering shade and ventilation, but is also a reflection of the neighborhood’s social structure, emphasizing security and privacy [7]. The courtyard houses, a prevalent feature, serve as the nucleus of family life, providing a private outdoor space. Thus, architectural elements of the built environment contribute to a unique urban fabric that fosters strong community bonds while accommodating the need for individual and family privacy.

Therefore, examining this phenomenon from an anthropological and sociological aspect of traditional Arab neighborhoods provides a foundational understanding of how cultural and social norms are spatially manifested and experienced. Scholars such as Edward Said (1978) [8] and Clifford Geertz (1973) [9] offer insights into the symbiotic relationship between space and culture, emphasizing that the design of these neighborhoods is a reflection of social structures, including family dynamics, gender roles, and community relationships. Research in this area highlights how the spatial configuration of neighborhoods—encompassing private homes, communal spaces, and the segregation of functions—facilitates social interactions that are in harmony with cultural expectations and religious practices [10].

For example, Patrick Le Galès and Tommaso Vitale (2014) [11] investigate the complexities of city management in urban regions. They challenge the notion that large cities are difficult to govern because of their complexity and the effects of globalization. The authors claim that city governance is a dynamic, nonlinear process that has a substantial impact on social inequality and urban growth. They emphasize the need to understand how governance processes work and their outcomes in order to effectively address concerns. The authors emphasize the importance of understanding both official and informal governance processes to develop a better understanding of how cities are administered and how these strategies influence urban growth and inequality. This demonstrates that city administration requires an interaction between apparent official structures, such as zoning laws and planning initiatives, as well as unseen networks, borders, and behaviors, all of which play an important role in determining urban growth and the daily lives of urban inhabitants.

Building on this foundation, the decision-making processes and the maintenance of social order within these neighborhoods are crucial to maintaining a homogenized structure. The spatial organization of the traditional Arab neighborhood facilitates a complex system of social order that is evident in its governance structures, which range from informal family networks to formal community councils [12]. Public spaces, such as mosques, markets, and squares, serve as vital hubs for communal decision-making and social interaction, supporting a decentralized yet cohesive social structure. This aspect of the literature highlights how traditional Arab neighborhood forms of governance and social regulation are embedded within the urban fabric, reinforcing a community’s values and norms through spatial practices [13,14].

Tommaso Vitale [15] also investigates how the institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework might be used to analyze policy, highlighting the importance of incentives. He divides incentives into four categories: direct financial, indirect financial, nonfinancial, and wide social incentives. Vitale makes the case for a method that takes into account these incentives from both the top-down and bottom-up perspectives. This holistic method is expected to promote urban research by resolving conflicts over urban resource allocation and enhancing governance.

The topic dives into the subtle ways in which incentives shape spatial organization and define visible and virtual boundaries inside cities. Although Tommaso Vitale’s research focuses mostly on laws and the impact of incentives on governance, it is possible to conclude that these mechanisms have an indirect impact on spatial order by driving development projects, infrastructure investments, and social service distribution. These procedures can reinforce or challenge existing geographical divides and hidden borders that have an impact on social unity, resource access, equity, and inclusivity in urban environments. Vitale examines incentives to provide a viewpoint on the complex link between policies, governance practices, and the physical and social features of urban areas [15].

The socio-spatial organization of traditional Arab neighborhoods showcase a complex interplay between physical spaces and social structures. The arrangement of homes, markets, and mosques within these neighborhoods facilitates a high degree of social interaction, reinforcing communal ties and collective identity [5]. This spatial configuration supports traditional social norms and hierarchies, with public and private spaces clearly delineated to respect cultural and religious practices. Thus, the spatial design of neighborhoods facilitates communal living, with shared spaces promoting collective activities and decision-making processes [4].

This makes the concepts of placemaking and place identity crucial for understanding how traditional Arab neighborhoods foster a sense of belonging and cultural continuity. The literature on placemaking examines how architectural elements, urban layout, and the use of public spaces all contribute to a distinctive place identity that resonates with the inhabitants’ cultural and historical heritage [16]. Researchers such as Kevin Lynch (1964) [17] and Yi-Fu Tuan (1977) [18] have contributed to our understanding of how physical landmarks, pathways, and nodes within these neighborhoods create navigable and memorable urban landscapes that reflect communal values and historical narratives. This body of work underscores the importance of placemaking in sustaining the cultural identity and heritage of traditional Arab neighborhoods, highlighting the role of architecture and urban planning in creating meaningful spaces that embody the community’s collective memory and aspirations.

The Socio-Structure and Urban Dynamics of Arab Cities

The concept of socio-structures in neighborhoods offers a holistic view for analyzing the intricate connection between social dynamics and physical spaces in urban areas. This framework helps to explore social organization patterns, cultural identities, and neighborhood spatial layouts. By taking into account elements such as housing types, infrastructure, public spaces, and the availability of amenities, we uncover insights into how these factors influence social interactions, community ties, and the overall experiences of individuals and families in their local surroundings [19]. Delving into socio-structures enhances our understanding of how people interact with their environment, revealing the mutual impact of social processes and physical spaces on each other [20,21].

Through an in-depth examination of Najdi towns, the study attempts to uncover the unique relationship between spatial arrangements, societal structures, and urban planning decisions. A noteworthy example is the ‘hella’ model, a neighborhood pivotal to social and physical organization. With the unique layout of Najd towns, these neighborhoods promote community unity and encourage privacy, social connections, and adaptation to environmental factors [22]. Moreover, they reflect Islamic principles and local traditions in their spatial design, making them a captivating subject of study.

Placing these inquires within the broader context of the Middle Eastern urban landscape, it becomes clear how crucial it is to investigate similar socio-spatial frameworks. For instance, cities such as Baghdad and Cairo bear historical influences that have shaped their urban fabric, featuring unique neighborhood setups similar to the ‘hella’ model. These neighborhoods, acting as hubs for community engagement and cross-cultural interactions, underscore the significant role of community in shaping urban dynamics in the region [23]. Moreover, delving into how these historical legacies continue to shape urban development can provide invaluable insights into the resilience and flexibility of Middle Eastern cities, making this study all the more pertinent.

Exploring the nucleus of Baghdad, which took shape during the Abbasid period, we can observe a unique urban design. This design, characterized by a radial circular layout, was aesthetically pleasing and prioritized security, administrative efficacy, and communal harmony [24]. This distinctive urban design is a testament to the time’s thoughtful planning and societal values. The characteristic features of the city, such as the Muqarnas and Iwan, showcase a mix of practical, social, and environmental factors reminiscent of Najdi towns [25]. These design elements supported community interactions while maintaining privacy and adaptability to the climate, creating a spatial layout that highlighted communal identity within specific spatial limits [26,27].

In its Islamic and Coptic neighborhoods, Cairo’s layout clearly supports Islamic urban planning principles. The intricate irregular streets and dead-end alleys in historic Cairo, particularly from the Fatimid era and subsequent Mamluk improvements, reflects the social and spatial arrangements found in Najdi towns [6,28]. The concept of ‘Hara’ in Cairo embodies the spirit of neighborhoods, where spatial structures support social monitoring, community gatherings, and religious practices, strengthening the socio-spatial fabric akin to the ‘hella’ in Najd [29].

As a result, the Najd region in Saudi Arabia is no exception regarding how urban fabrics are arranged spatially [14]. By looking at urban conditions in the Arab region, we can better grasp how the Najd region is structured similar to its peers in the region. The social and cultural identities in Baghdad and Cairo, for example, influence these cities’ social and spatial arrangements of neighborhoods. In Baghdad, neighborhoods might have a mix of religious or ethnic groups, while those in Cairo often show differences in wealth levels [30,31]. In both Baghdad and Cairo, houses vary significantly in size, layout, and architectural design, reflecting the needs and preferences of their residents [32,33]. Thus, communities’ structure and physical layout play a crucial role in shaping cities. This includes how streets are organized, the presence of spaces, the mix of different land uses, and the availability of amenities. Historical, cultural, and socio-economic factors as well have influenced the urban landscapes of Najd, Baghdad, and Cairo and other Arab cities [34,35].

Table 1 presents an analysis and theoretical framework for Najd, Baghdad, and Cairo. The study examined four aspects: privacy and social interaction, adaptability to environmental factors, cultural and religious influences, and urban morphology. The comparison revealed that while each location has its own urban characteristics, they all share similarities in their treatment of privacy and social interactions in response to environmental challenges and the impact of cultural practices on urban design. The theoretical frameworks derived from this analysis emphasize the significance of viewing morphology as a reflection of societal values, environmental adaptation strategies, and cultural heritage. The lessons from these insights provide guidance for modern urban planning, highlighting the importance of considering cultural nuances, adapting to climate changes, and prioritizing community-oriented approaches in urban development.

Table 1.

Arab city comparative analysis.

3. Method

The study of traditional Najdi settlements incorporates a detailed examination of spatial dynamics and decision-making processes through the use of case studies and spatial analysis. This study took an interdisciplinary approach, integrating urban morphology, architectural phenomenology, and sociological studies to analyze the socio-spatial structure of these neighborhoods.

The study’s qualitative approach involved analyzing the relationships between social behaviors and spatial configurations within urban environments. It examined how social interactions, cultural practices, and community dynamics are influenced by the physical layout of spaces [52,53]. This approach used observations and participatory methods to understand the lived experiences of inhabitants and how they perceive, use, and navigate their surroundings. The study aimed to reveal the underlying social structures that shape and are shaped by the urban form, contributing to a holistic understanding of urban life and planning. In this context, the methodology employed in this study was multidimensional, combining several qualitative datasets that were guided by the study’s framework to gain knowledge of the spatial dynamics and social order within Najdi urban landscapes. The theoretical framework of this study was intended to investigate the challenging interplay between spatial dynamics and social order in traditional Najdi settlements.

- Urban Morphology: This field of study examines the shapes and forms of urban areas, gaining an understanding of how different socio-economic and cultural factors contribute to the changes in the physical layout of towns and cities over time [54,55].

- Architectural Phenomenology: Highlighting the lived experience of space, this philosophical approach to architecture focuses on human experience, perception, and the meaning of place [56].

- Sociological studies: This includes studying neighborhood cultural norms, community relationships, decision-making processes, and social structures [57].

The theoretical framework directs data collection and analysis, ensuring that research subjects are handled systematically and cohesively. This framework served as a lens through which to explore the relationship between spatial organization and social systems, with a particular emphasis on the concept of neighborhood, or ‘hella’. Complemented by qualitative spatial analysis techniques, such as Space Syntax, to model the social effects of spatial configurations, the study evaluated how different spaces within urban environments are connected and how this connectivity influences movement, behavior, and social interaction [58,59].

3.1. Setting the Context

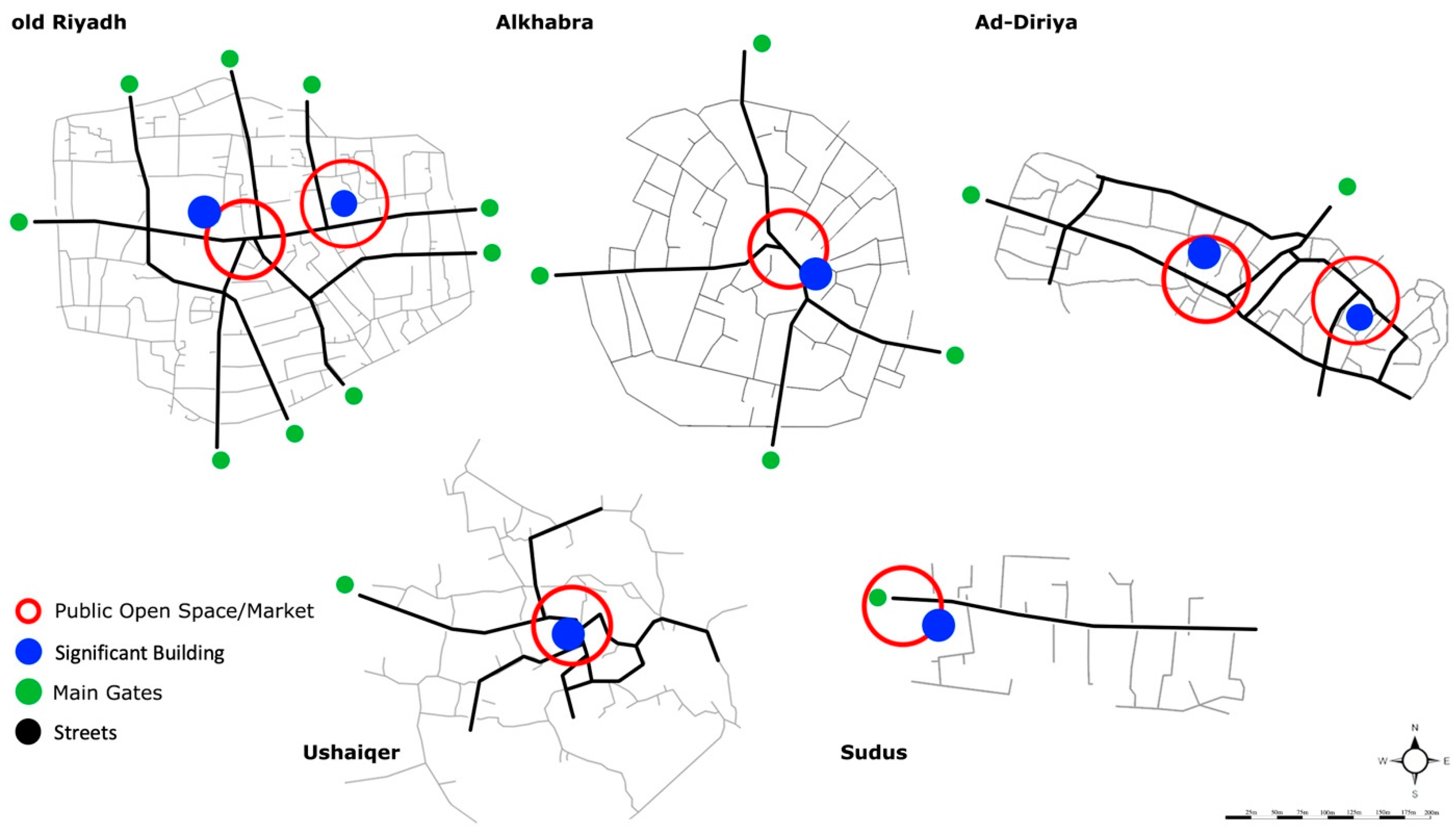

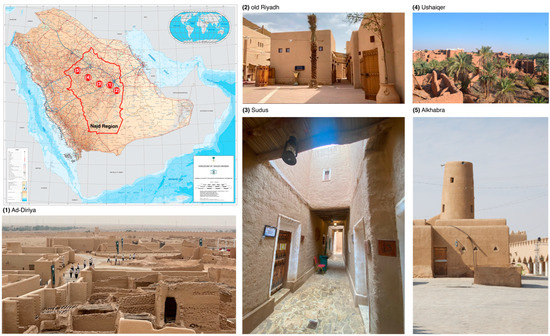

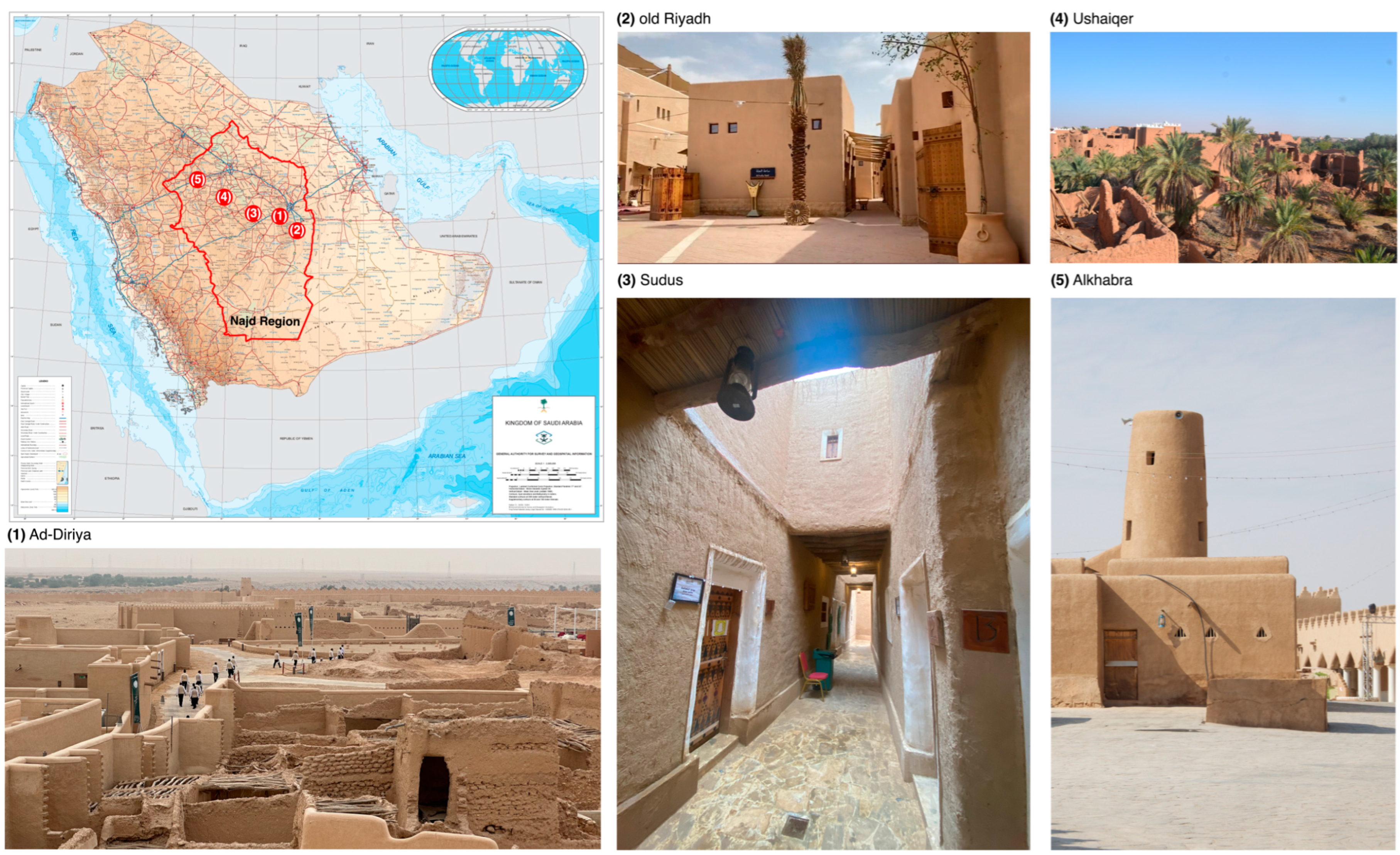

The study focused on five Najdi region communities in Saudi Arabia, each with its own particular historical and cultural value. Ad-Diriya, Riyadh, Al Khabra, Ushaiqer, and Sudus were chosen to provide diversity in urban landscape and layout to aid in the examination of spatial order and hidden (virtual) boundary processes by examining and analyzing a range of traditional settlements in the Najdi region (Figure 1):

Ad-Diriya: located near Wadi Hanifah (seasonal river Hanifah), where locals constructed the community in a valley in the Najd region bordered by the vast sand deserts of the Nafud to the north and the Empty Quarter to the south. Wadi Hanifah flows through Jabal Tuwayq (the mountains), known as the “backbone of Arabia”, beginning in the southwest and ending in the Empty Quarter, flowing northwards into Nofud for around 650 km (roughly 403 miles). Ad-Diriya and Uyaynah are notable communities in Wadi Hanifah, dating back to the 15th century. The importance of Ad-Diriya peaked between the 18th and early 19th centuries, when At-Turaif, a component of the Ad-Diriya area designated as a World Heritage Site in 2011, became the first governmental hub founded by the House of Saud (the royal family) [60]. This location became the heart of the “First Saudi State”, which developed between the middle of the 18th century and the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

The Old City of Riyadh: located where Wadi Batha meets Wadi Hanifah, which provides a continual supply of fresh water, allowing for a permanent town and cultivation. It became the administrative center of the ‘Saudi State’ when King Abdulaziz reclaimed control of the town in 1902. Since then, the king has had his seat of administration at the Qasr Al Hukom (Palace of Administration), which belonged to his grandfather, Imam Faisal Ben Turky [61]. This marked the start of the unification process that eventually led to the establishment of the current Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which was officially declared in 1932. Riyadh expanded during its tenure as the capital in 1824, with palaces, mosques, gates, and districts built during the nineteenth century [62]. The city was revitalized during King Abdullaziz’s reign, with the rebuilding of numerous buildings.

Alkhabra: is a town that sits 380 km (approximately 206 miles) north of Riyadh, the capital city. It is part of the Al-Qassim region, situated approximately 60 km (38 miles) from Buraydah, the region’s capital, and 40 km (25 miles) from Unayzah, the region’s second largest city. Established over 340 years ago, this settlement town rests on the side of the Al-Ruma valley. The valley has been instrumental in shaping Al Khabra’s reputation and significance in Najd by supporting critical activities such as farming, herding, and trade [63]. Due to its impact on both architecture and socio-economic life, the Al-Ruma Valley has been the foundation of Al Khabra’s prosperity over the past three centuries.

Ushaiqer: is located in the Al-Washem province. Ushaiqer is a traditional settlement with a deep Islamic heritage and derives its name from the Arabic term ’ashgar’, which means ‘bright’, most likely because of its contrast with the adjacent red mountain [64]. Before Saudi Arabia’s unification, Al-Washem was known as “the dwellings of Tamim,” a well-known clan in the Arabian Peninsula. The town, located north of the Shakra province and 170 km (105 miles) west of Riyadh, has a diverse geography, including sand and rock ridges as well as lush plains that have made it renowned for agriculture and trade in the Najd region.

Sudus: is a small town constructed of mud brick located 75 km northwest of Riyadh. Unfortunately, half of the town was abandoned and left in ruins; nonetheless, extensive documentation related to the original town remains. A palm tree oasis surrounds the town, providing a barrier against the arid, extreme heat of the Najd region. Al-Murgab, which translates to ‘the place of observation and monitoring’, is home to defense towers and walls that encircle the village. Sudus’ urban design features fortified walls and protecting corner towers. In an area of 10,000 m2, approximately 85 dwellings comprise an extended clan known as ‘Almueamar’.

Figure 1.

Najd region and town’s location. Source: map [65], images from authors.

Figure 1.

Najd region and town’s location. Source: map [65], images from authors.

3.2. Observational and Graphical Analysis

The observational and graphical analysis approaches were critical to the study given that they involve systematic fieldwork in chosen Najdi towns. Researchers used physical walkthroughs to document the spatial layout, architectural elements, and urban fabric. These observations were critical for identifying major spatial organizing patterns as well as comprehending each area’s socio-cultural background [66]. Thus, extensive on-site observation was critical for gaining direct insights into the physical attributes and daily lives of Najdi settlements. This involved the following:

- Visual Documentation: Entails meticulously documenting architectural features, street layouts, and the interaction of private and public places with photographs and sketches.

- Behavioral Mapping: Observing and recording urban patterns and town layouts to acquire insight into how public and private places are used in everyday life [67].

In addition to observational data, researchers used diagrams, maps, and illustrations to visually represent the structure and architecture of Najdi neighborhoods. This approach served to clarify the interaction between various spatial components, such as private dwellings, public areas, and circulation networks, showing the fundamental principles of urban morphology. Thus, graphical analysis was used to translate observational data into visual formats that show the spatial characteristics of Najdi settlements, which involved the following:

- Mapping: Creating neighborhood maps that highlight crucial aspects, such as path networks, building density, and the presence of common areas.

- Diagramming: Complex urban relationships are simplified to diagrams that show the hierarchical structure of places and their roles inside towns.

3.3. Interviews

Between 2022 and 2023, qualitative data were collected through interviews with local residents, community leaders, academics, and urban planners. These interviews sought to discover intangible components of social order, community values, and decision-making processes that were not immediately obvious from observation and graphical analysis. The interview approach was semi-structured, allowing for in-depth discussions while ensuring that essential issues relevant to the study’s objectives were covered. The sampling varied between towns based on availability; however, we ensured to interview at least two historians and two elderly people from each town supported with four Saudi Arabian scholars in the related field to synthesize and enhance the quality of the information collected. Thus, interviews were used to record the subjective experiences and viewpoints shared by individuals inside the community.

- Semi-structured Interviews: This interview format allows for conversational flexibility while guiding interviewees to discuss research-relevant topics, such as social norms, decision-making, and community relationships.

- Oral Histories: This method involves gathering stories and personal experiences from long-time residents. The oral histories aid in understanding historical changes as well as each town’s intangible legacy.

In order to gain insight into the lived experiences of the residents, the social and cultural development of the community, and the interaction between the physical environment and social structures within traditional Najdi towns, the study questions were created to elicit detailed responses (Table 2).

Table 2.

The study interview questions.

3.4. Space Syntax Technique

The Space Syntax technique was used to examine the spatial configuration of Najdi towns. It entailed developing a graphical representation of the urban landscape, which was then used to evaluate connections and integration within towns. Space Syntax gives color measurements that aid in understanding how mobility patterns, visibility, and accessibility influence social interactions and neighborhood spatial hierarchy [68]. Thus, the Space Syntax approach analyzes spatial patterns and their impact on social behavior. The intent was not to quantify and provide set of numerical values but to make use of this tool to illustrate the spatial order in Najdi towns through Axial and depth map presentation to support the study objectives.

- Axial Analysis: This method assesses the interconnectedness and integration of various streets within the urban grid, determining the accessibility of different parts of town [69].

- Depth Analysis: This analysis evaluates the possibility of alternative routes being taken for movement through the town, highlighting and suggesting possible major social pathways and hubs of activity.

By analyzing the layout of buildings, streets, and cities as networks, Space Syntax provides insights into the accessibility and integration of spaces, helping urban planners and architects understand how design impacts human activity and social cohesion. Combining these methods enabled the study to provide a comprehensive, multidimensional view of the physical and social dynamics within traditional Najdi settlements. This comprehensive approach ensured that the findings captured the multifaceted nature of traditional Najdi towns, laying the groundwork for future study and practical applications in urban planning and cultural protection.

4. Result: The Urban Morphology and Spatial Dynamics of Najdi Towns

The section delves into the spatial dynamics and social order of traditional Najdi towns, emphasizing the concept of ‘hella’, or neighborhood. It illustrates the dual decision-making processes at the macro (public spaces controlled by rulers) and micro (private residential areas controlled by inhabitants) levels, highlighting the importance of spatial hierarchy in establishing control points between public and private domains. The study delves deeper into how these decision-making processes and spatial ordering lead to the formation of hidden (virtual) borders within the built environment, influencing social connections and the physical urban form. The goal is to emphasize the importance of hidden (virtual) boundaries in maintaining social unity as well as the dynamic linkages between the macro and micro levels of decision-making, which together influence the urban morphology and social fabric of Najdi communities.

4.1. Exploring the Notion of ‘Hella’ and How It Impacts Decision-Making Processes

The traditional neighborhood, known as ‘hella’ in Arabic, has its roots in the layout of spaces and evolved from the cohesive spatial and physical organization seen in traditional Najdi towns, which also reflected the prevailing customs [70]. These towns functioned based on decisions made by the community and adhered to shared social norms. The urban design of these areas was shaped to facilitate this structure.

Moreover, public spaces (outside areas) were overseen by leaders or authorities at a broader level, while private residential zones were managed by residents themselves at a more localized level. Basim Hakim highlights that decision-making processes involve an interaction between leaders and inhabitants. He argues that these dynamics influence how a town is structured into hierarchical residential sections [71,72]. This dual approach to decision-making spanning both macro and micro levels empowers authorities to regulate amenities, such as mosques, schools, markets, and streets, while granting residents autonomy over their personal spaces, where decisions directly impact their daily lives.

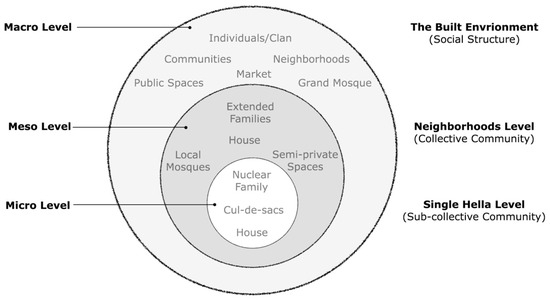

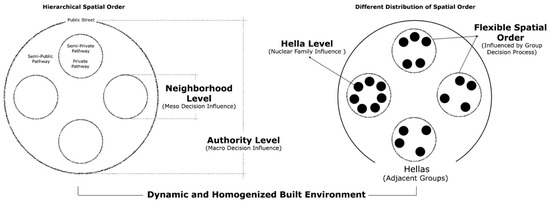

The five towns have processes for making decisions on both large and small scales. As shown in (Figure 2), there is a hierarchy in the traditional settlements that establishes points of control between public and private areas. These points of control naturally adapt over time to form necessary boundaries. These boundaries, also known as ‘thresholds’, can be either visible (physical) or hidden (non-physical, virtual). They can shift depending on changes in the control points in different areas. The objective of this process is establishing a social order to assist the collective and sub-collective communities in defining and respecting the boundaries between the different urban domains within a space and time. Through this process, property owners, residents, and leaders in Najdi towns can better understand each other’s roles and cooperate harmoniously, whether consciously or subconsciously.

Figure 2.

Najdi town urban hierarchy and its three-social order. Source: Authors.

4.2. The Impact of Decision-Making Processes on the Creation of Hella

The spatial organization suggests that the hierarchical arrangement of spaces evolved to facilitate and structure decision-making at both small and large scales in traditional Najdi towns. This organization involves a decision-making process with levels of macro and micro decision-making that led to the creation of implicit boundaries within the built environment without direct input from the residents. This indicates that these organizational processes are deeply ingrained in the minds of the inhabitants, manifesting themselves both consciously and subconsciously through various means: the actions of inhabitants, their individual and communal choices, their interactions with nature, and their utilization of available resources and technology.

Each building cluster in Najdi towns comprises an irregular mass made up of smaller irregular mass housing compact building forms that cater to social, cultural, and environmental needs. The argument presented in this study is that if Najdi towns were established within walls for security purposes—shaping the overall urban layout—the question arises: how did internal boundaries (thresholds) between different areas impact people’s lives? How is this reflected in the configuration of building masses?

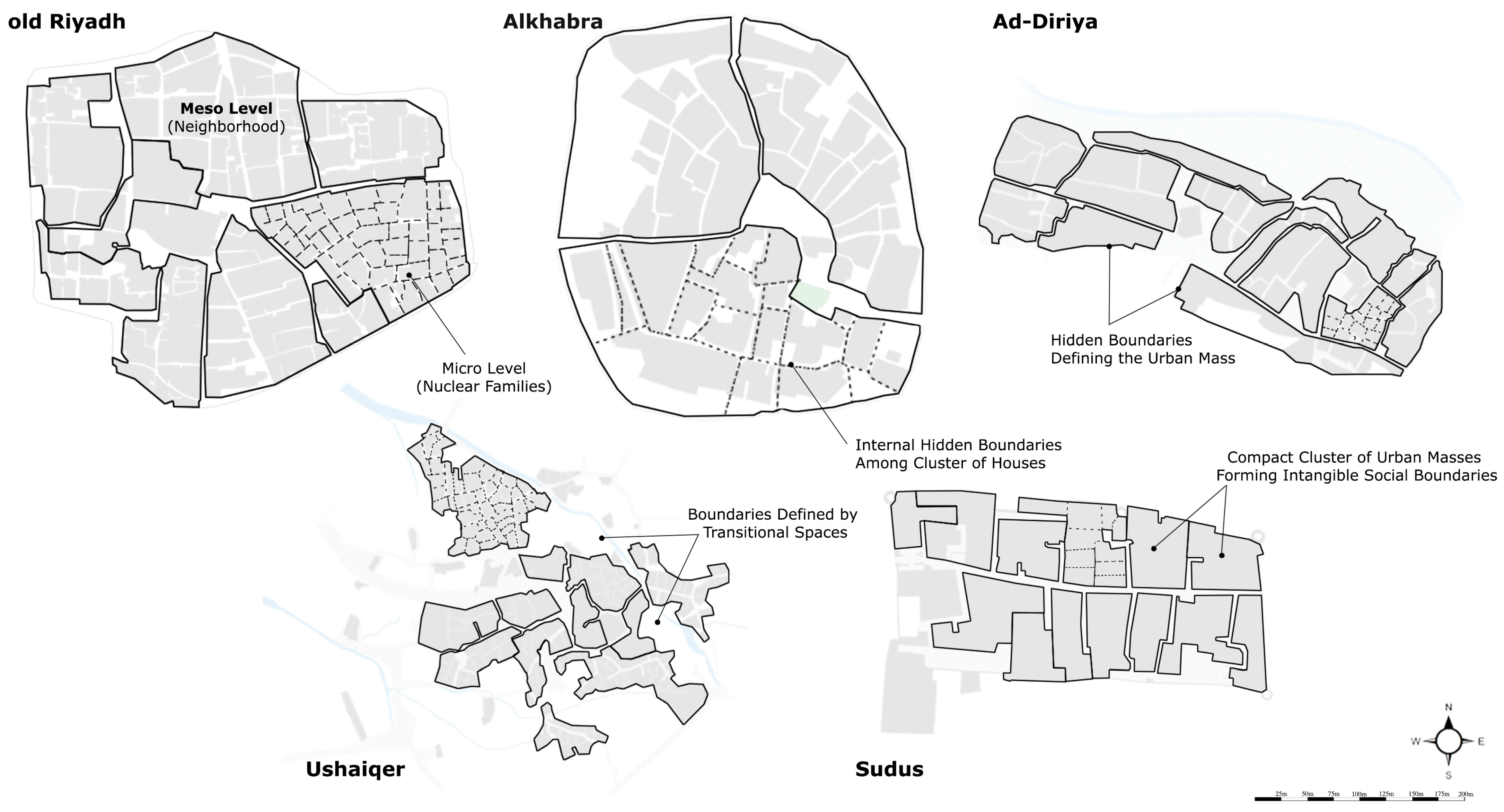

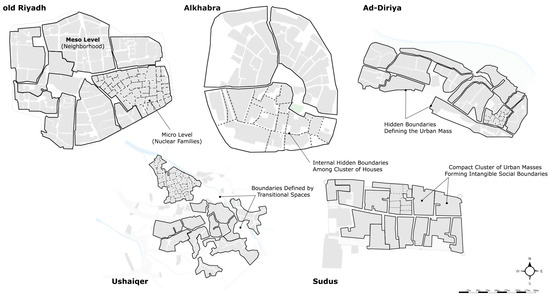

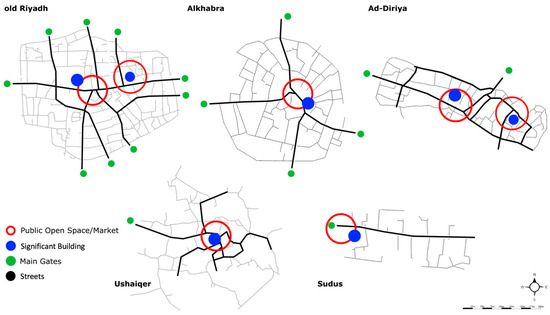

It was quite challenging to distinguish physical boundaries between the various residential quarters, known as hellas, in the case studies we selected. The hellas appeared to blend, forming densely packed masses that were delineated by networks of pathways (refer to Figure 3 and Figure 4). Nonetheless, in instances within the region, doors situated at the fronts of cul-de-sacs served as physical barriers for small groups of houses. At the physical level, each hella comprises a unified mass containing houses, pathways, and open spaces, collectively shaping an irregular urban mass that varies from one hella to another. The significance of these hellas in the towns lies in their capacity to spatially define different social groups across extended periods of time.

Figure 3.

Top view examples illustrating the compacted and organic urban fabric of Najdi traditional towns. Source: Authors.

Figure 4.

Illustration of Najdi towns social dynamics influence on “hella” urban masses formations. Source: Authors.

As previously mentioned, it is crucial to recognize and comprehend the connections present in neighborhood development, as these relationships play a key role in understanding decision-making processes at both macro and micro scales. These connections are evidenced in the process of making urban districts (hella). While the structures of buildings maintained the fabric of the area, its inhabitants upheld their genealogical identity among social groups without necessarily manifesting these social connections physically. Although individual group identity may not stand out more prominently than the community as a whole from a physical standpoint, people sought to define themselves socially through their spatial presence by cultivating their private neighborhood and identifying its hidden (virtual) boundaries within the overall compacted structures of their urban form. The people of the Najd region have culturally and physically embedded this concept over centuries to preserve their identity and their social organization.

Even though each neighborhood (hella) may have established its own social identity, individual and subgroup physical identity did not carry significant weight in such a collective society. This mirrors the distinction made by Vaughan et al., (2005) [73] between the majority and minority influences on spaces. Their study indicates that minority groups often have limited influence, and they impact the areas they inhabit, while the majority holds a more significant role. This dominance of the majority stems from the inhabitants’ belief in maintaining an identity within their community [74].

The flexibility in growth and the shrinking of the urban space within a given area depends on the flexibility of the hidden boundaries and by the dynamic of the Alshuf’a principle which governs property transactions—including houses or portions thereof—among neighboring spaces. This process leads to urban areas (hellas) stretching or compressing based on social conditions, the size of the extended families residing in the hella, or economic factors prompting residents to seek new living arrangements in other places.

At the micro level, the decision-making process of individuals and small groups determines the density of neighborhoods, the layout of streets paths, and the allocation of open spaces based on local climate and environmental topography. These practical decisions reflect a common thread across the five cases, resulting in similar neighborhood characteristics but different urban layouts in each case. The process of interpretation occurs both in the conscious and subconscious decisions of inhabitants, leading to similar but yet not identical spatial arrangements and urban designs among the Najdi towns. These tangible and intangible dimensions act as a governing mechanism within the urban layout, which regulates the creation of spaces through a flexible interpretation process by specific sub-collective community.

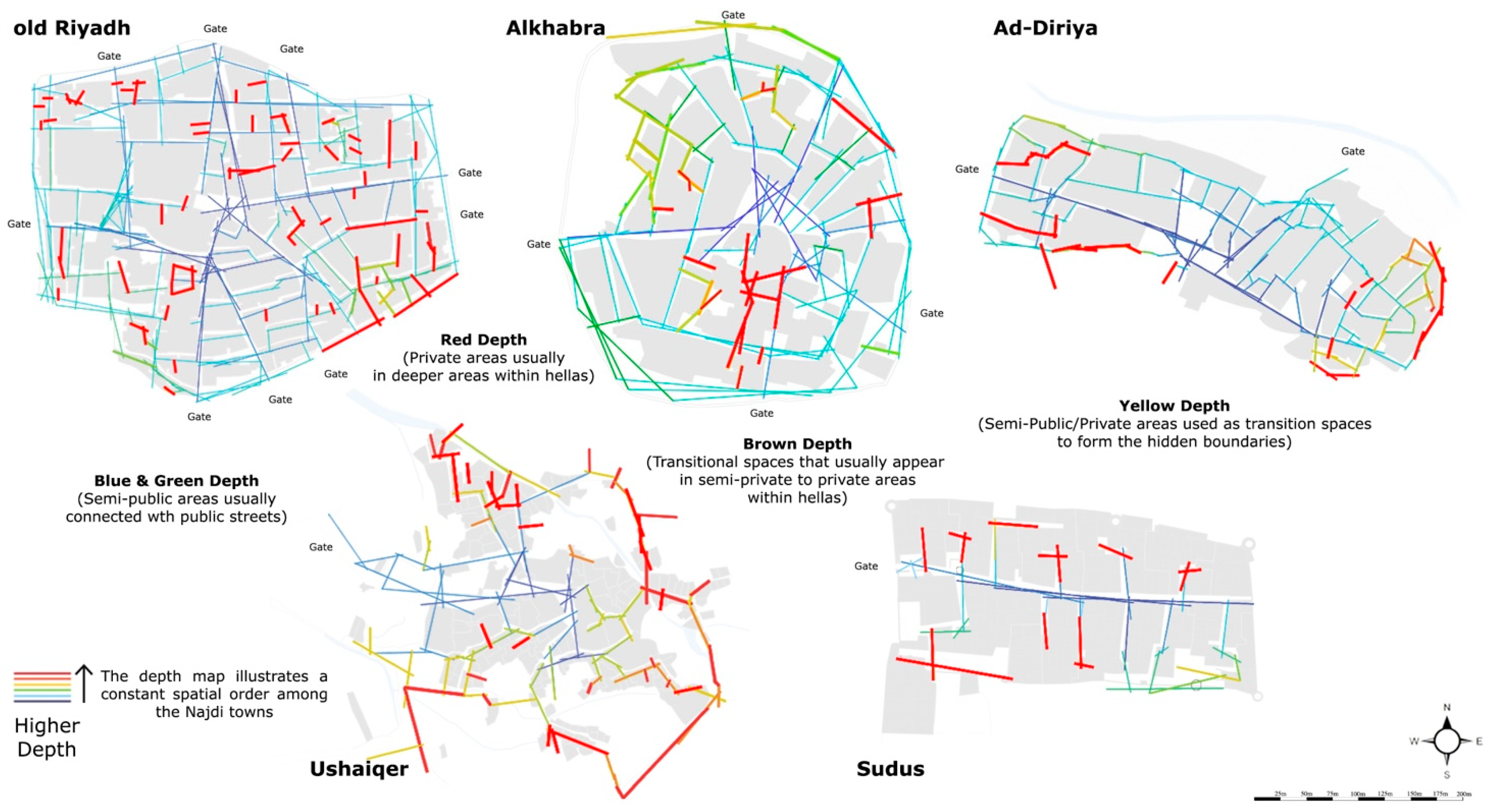

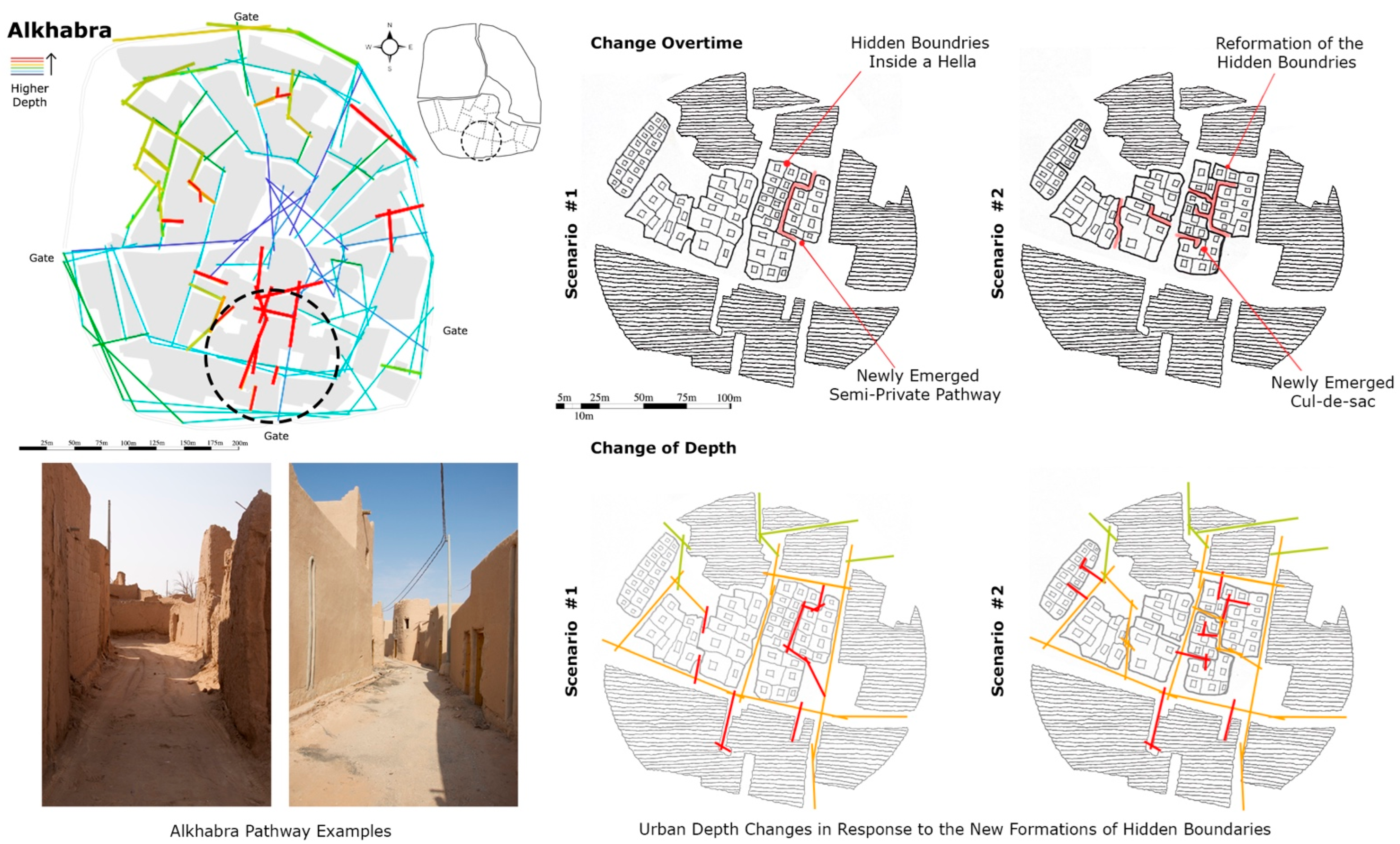

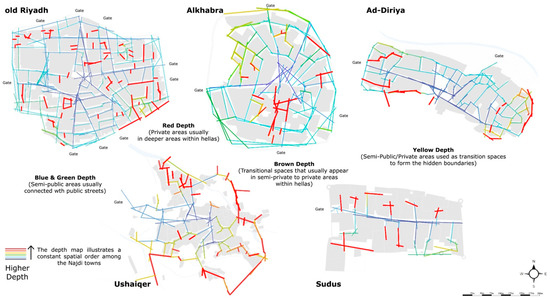

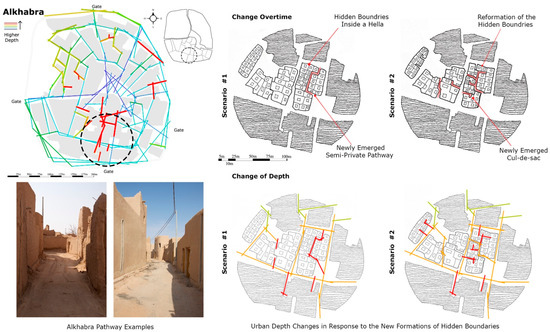

The study utilized the Space Syntax Axial Line depth mapping technique to explore this phenomenon. The analysis generated maps highlighting areas at a detailed level (red and brown) while areas with less depth were categorized as semi-public and public (yellow, green, and blue) (Figure 5). With urban layouts in the five cases, the analysis reveals how Najdi towns manifest their invisible (virtual) boundaries in the structure of their deep spaces. By examining each of the traditional settlements through the depth maps technique, this study uncovered these hidden (virtual) boundaries that delineate a hierarchical order of spaces between macro and micro levels.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of five Najdi spatial order using Space Syntax depth map tool. Source: Authors.

King et al. (2017) [75] suggest that borders and state boundaries have a significant role in defining a state’s territorial foundation, setting it apart from other states, and managing the movement of migrants. They emphasize that overseeing and monitoring frontiers allows states to establish themselves, offer essential services, and engage with emerging nation-states. Looking back at history, it is evident that European states began exercising control over migrant movements in the late 19th century by introducing documentation for migrants’ identities and enhancing frontier surveillance efforts. Therefore, boundaries influence areas by regulating access and mobility, shaping national and regional identities, impacting social and economic interactions, and addressing security considerations.

For example, Najdi neighborhoods characterized by open spaces and wide streets may suggest that the community is more open to the outside, whereas areas with tightly clustered buildings and narrow streets typically signify a more secluded community setting. This highlights how residents perceive these relationships as a rooted aspect of their local culture, shaping both their conscious and unconscious engagement with placemaking. Thus, individuals intuitively decode these different urban settings upon entering another private area that is distinctly demarcated and exclusive. This understanding of spatial organization influences social interactions and community dynamics, as residents navigate the physical environment in accordance with these cultural norms. Ultimately, the morphological design of a neighborhood can impact the sense of belonging and identity that individuals feel within that space. This perspective aligns with King et al.’s (2017) [75] argument that the effectiveness of boundaries and policies directly impacts the assimilation and integration of individuals, highlighting the significance of boundary management in contemporary governance and urban planning.

4.3. The Impact of Hidden Boundaries on Establishing Dynamic Unity

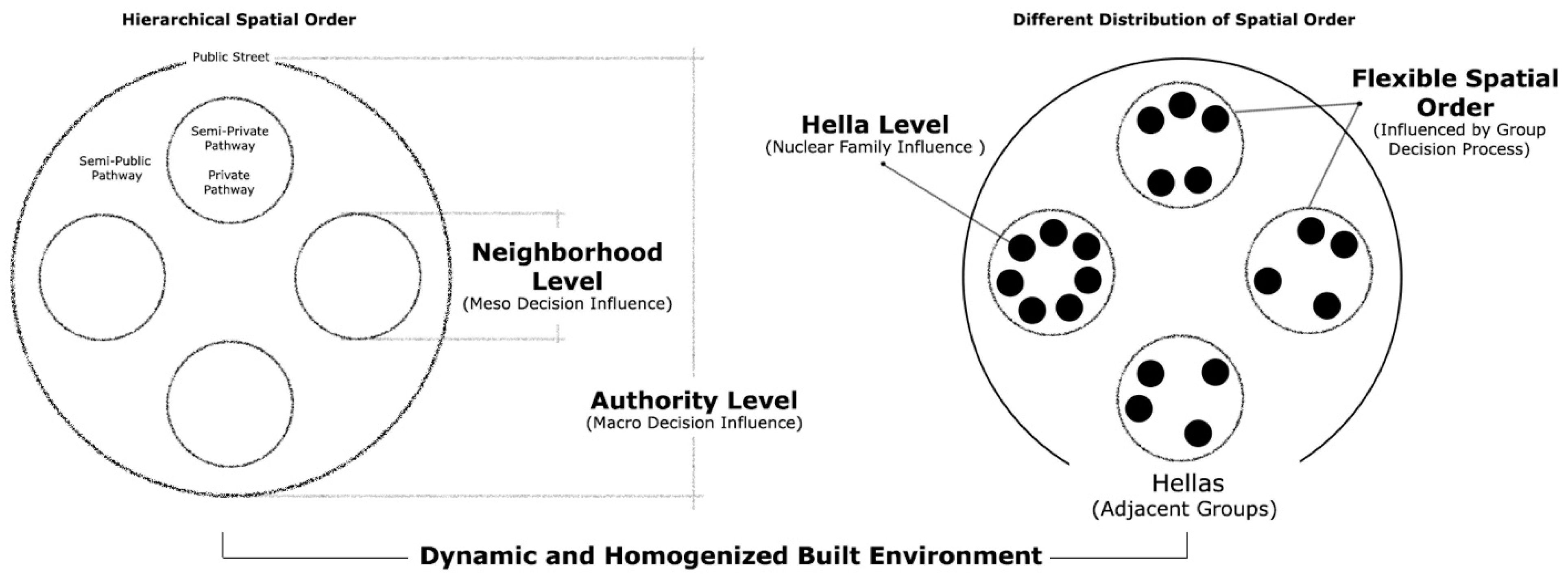

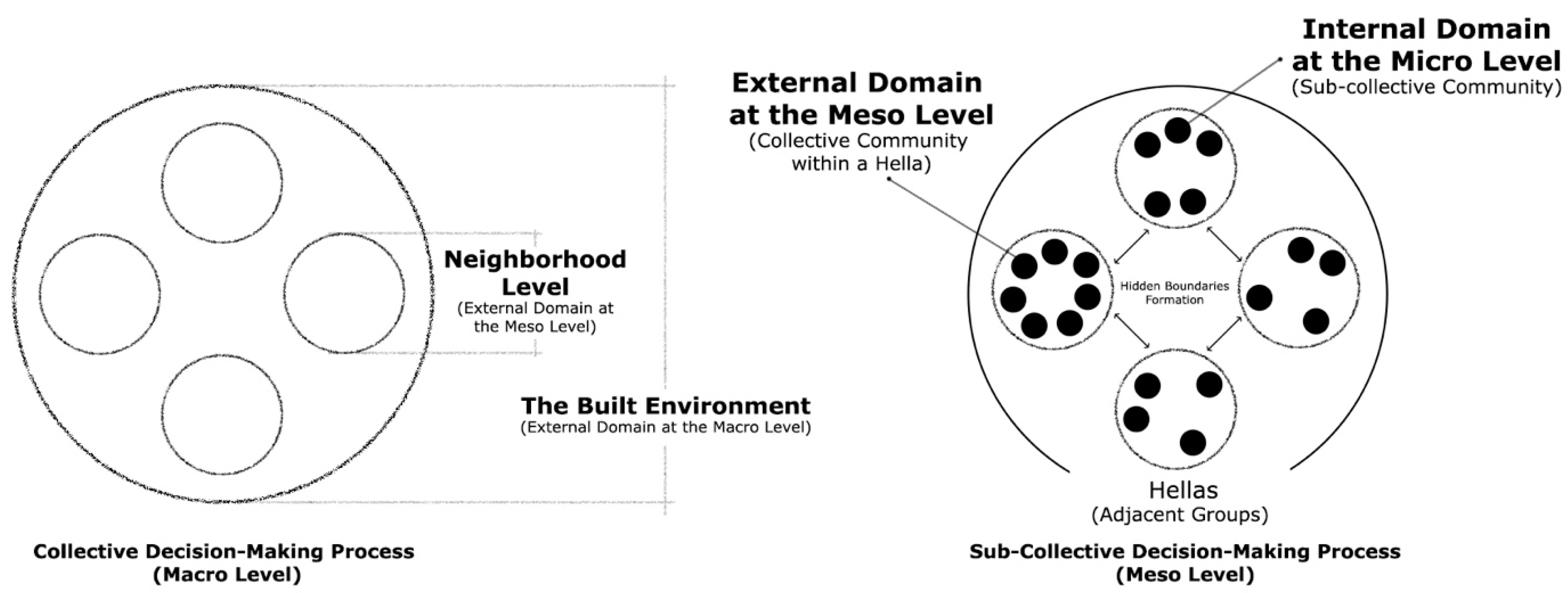

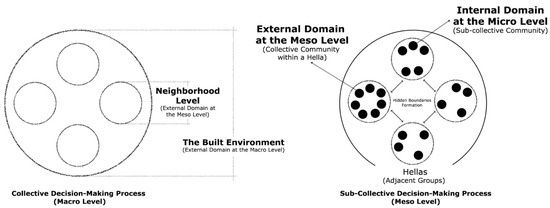

The impact of decision-making processes on shaping the urban mass was explored by analyzing structural elements of the Najdi towns. The study identified three territorial divisions linked to communal authority, neighboring groups (the quarter), and members of an extended family (Figure 6). These territorial divisions played a role in organizing the town into residential quarters known as hellas, each with its own decision-making hierarchy.

Figure 6.

Embedded territorial divisions within the Najdi urban fabrics. Source: Authors.

A further investigation delved into the formation of these quarters, revealing how establishing a hierarchy influenced macro and micro decision-making procedures. Understanding this influential relationship is crucial because the overall town structure (macro level) is not solely determined by individual residential masses (micro level); instead, they work together in a unified process that shapes a homogenized urban fabric. Thus, the interplay between macro and micro levels in Najdi towns significantly impacts the placemaking processes involved in urban fabric formation (Figure 7). This intricate relationship sheds light on how physical structures evolve through dynamic interpretations at the micro level while sharing fundamental principles at the macro level.

Figure 7.

The similarity between the macro and micro levels on generating urban spaces in Najdi towns. Source: Authors.

Analyzing the layout of the five Najdi towns reveals that hidden boundaries are not based on physical features but are produced according to the macro and micro levels of the decision-making process. These hidden boundaries play a role in maintaining social cohesion within the town by subdividing it into smaller residential areas to resemble flexible zones within the urban structure. These zones, known as hellas, represent compacted areas that are further divided into clusters of houses by additional unseen boundaries. The manifestation of these boundaries is not always explicit, as each residential area forms a unit influenced by social organization and patterns such as status, dominance, gender roles, and social interactions. These boundaries manifest during gatherings for activities such as meeting, eating, and working.

Different social groups utilize these hidden boundaries to express their social identities at their micro level without disrupting the overall urban landscape. According to the findings of Abusaada and Elshater (2021) [76], people often use temporal divisions to highlight distinctions between different types of spaces. Even though the boundaries may not be visible, it is crucial to consider them when planning and designing spaces. In this context, each zone (hella) has the chance to express its characteristics in terms of its layout and external spaces while still maintaining a sense of shared cultural identity among various social groups.

The development of these hidden (virtual) boundaries reflects the everyday aspects of traditional community life through two key processes. The first process is decision-making at both a town (collective) level and a neighborhood-specific (sub-collective) level. The second process focuses on households or smaller groups within the neighborhood, where decisions are made at a more detailed level (Figure 8). This dynamic contributes to the differentiation between neighborhoods while collectively forming an urban fabric. People living in a community form a cohesive group that shares common social traits, engages in similar social behaviors, and agrees on specific meanings. These fundamental principles enable society to articulate its identity within that community.

Figure 8.

Collective and sub-collective communities influence on decision-making processes at both macro-scale and micro-scale levels. Source: Authors.

The physical layout of the hella (district) plays a role in shaping the relationship between the internal semi-private, private, and external public domains. The hella represents the ‘spatial theater’ of its inhabitants’ daily activities, which makes it a vital concept to help understand the social characteristics of a particular social group. Each district varies in its composition based on size and location, typically featuring residences (some with ground-floor shops), a local mosque, and a Baraha (a semi-private communal area for social gatherings).

The significance is how the hella in the Najdi towns evolved organically through communal interactions within a broader context. These interactions influenced how residents integrated (embedded, encoded) their socio-cultural values into the spatial layout and physical forms of their built environment. This organic process resulted in an urban structure that perpetuated itself without requiring deliberate planning. It is worth noting that similar patterns of hella or hara (residential quarter) formation can be observed beyond Najd towns. The hella is commonly found in other regions of Saudi Arabia, including Hijaz in the west, Al-Hofuf in the east, and parts of the Gulf region. In general, the hella is a physical manifestation that symbolizes the lifestyle of its inhabitants [77,78]. This dynamic process between the macro and micro levels is a fundamental concept deeply embedded in the social fabric of the community and reflected in their architectural surroundings. Therefore, the development of hellas stand as an idea and a tool for urban growth within traditional Najdi architecture.

Two key principles govern how hellas are created and organized: first, how each hella links with others. Second, how do multiple hellas come together to form a cohesive architectural environment? While the concept of hellas may symbolize close connections and a community lifestyle, it is important to consider that urban development should also prioritize functionality, accessibility, and sustainability in order to create a successful architectural environment. Focusing solely on the symbolic aspect of hellas may overlook important practical considerations in urban planning and design. The argument put forth is that the spatial layout reflects an organization influencing various transitions between public, semi-public, semi-private, and private spaces within traditional Najdi towns. This hierarchy allows for different hellas to integrate seamlessly into the landscape without disrupting the overall sense of place by establishing both physical and conceptual boundaries among them as well as different zones within.

The collective elements of the town play a role in defining features both in the town layout and within individual buildings. The integration of various elements within the town, then, allows for a seamless transition between the inner and outer environments. This dynamism enhances the overall cohesion and livability of the community. This concept highlights how locals have found ways to connect their private spaces with the outside world while still maintaining their privacy.

5. Discussion

Different cultures have a mix of elements that may continue to exist or change over time. This means that some level of change is necessary to allow cultures to adapt to social, economic, and technological shifts. Thus, cultural evolution is a natural process that allows societies to thrive and progress. Embracing change while preserving important traditions is key to maintaining a healthy balance within a culture. Without room for change, the physical structures in a culture would become rigid and not suitable for its people.

While the urban core of a town may seem stable and unchanging, there are underlying principles that offer flexibility to accommodate shifts without altering the overall urban landscape. These principles, known as Al-Shuf’a (neighbors’ right) and Haq Al-Irtifaq or Al-Murur (easement right), help regulate land use, coordinate private functions, and control building characteristics, such as height, windows, and entrances [12,13,79]. By incorporating these principles into urban planning and development, a culture can adapt to changing needs while still preserving its identity and heritage. This balance allows for growth and evolution without sacrificing the unique characteristics that make a culture distinct. In this way, the traditionally built environment in Najd maintained adaptable within its urban areas while preserving social cohesion.

As a result, the social cohesion within a community is greatly influenced by these principles, as they ensure that unfamiliar individuals are not able to relocate to the area through the practice of Al-Shuf’a (neighbors rights), which grants neighbors the opportunity to purchase any neighboring properties that are put up for sale. Additionally, Haq Al-Irtifaq (easement right) permits inhabitants to adjust and reorganize their homes based on their needs. This flexibility allows the inhabitants of the hellas to extend or reduce the size of their neighborhoods without impacting the main urban layout.

This study contends that the core concepts are closely intertwined with the physical organization, which is viewed as the fundamental ’hidden framework’ that inhabitants in Najd have utilized to shape and manage their traditional architectural landscape. Thus, it empowers individuals to make small-scale decisions that lead to alterations and enhancements in their surroundings, which allows for organic expansions and divisions at both the urban and buildings levels without disrupting the organization of the community.

The proximity of houses and their interconnectedness create a cohesive structure, enabling residents of the traditional Najdi environment to easily purchase sections of neighboring houses to incorporate into their own homes following the principles of Al-Shuf’a and Haq Al-Irtifaq. Based on interviews, this practice frequently occurs following the passing of a homeowner, typically a male. In some instances, it is common for his sons to divide and sell portions of the house to neighbors. This dynamic process sometimes extends beyond neighborhoods by selling sections or even entire homes to neighboring hella. This process enabled the hidden (virtual) boundaries to adapt to change, as the community was able to meet their needs by expanding their living spaces by adjusting the boundaries of their neighborhood and adding neighboring houses to their properties if those neighbors were willing to sell.

Islamic law permits property rights and freedom of use, allowing for transactions and the sharing of resources, such as water, rivers, wells, and building walls, among neighbors and partners. The rules aimed to prevent harm, safeguard neighbors’ interests, and protect spaces from individual encroachments. Al-Shuf’a governs buying and selling legal practices, emphasizing the importance of preventing harm among neighbors sharing property lines or real estate. The key consideration was understanding when neighbors have the right to purchase each other’s homes. This is important because the invisible (virtual) boundaries between two realms and within each realm could shift, leading to the physical structure either staying the same or adjusting based on the needs of the communities.

The processes of change in space respect the spatial order and endure through the collective actions taken by inhabitants within the built environment. These fundamental concepts shape activities and decisions, forming an integral part of the traditional community-building processes. Rapoport also aligns with this notion, elaborating on how group decision-making at different levels influences the quality of urban spaces. He suggests that such processes help communities create an environment that reflects their shared values [80].

As a result, in Najdi society, the social structure as was presented in (Figure 2) is organized into three circles. The first circle consists of clans typically affiliated with larger tribes but residing in specific urban settings. These clans played a role in building Najdi towns, fostering strong social bonds and unique nonverbal communication among inhabitants. The second circle comprises extended families, within which these clans are connected by blood relationships. These extended families provide a support system for individuals and contribute to the overall cohesion of the community. The third circle includes individual households, which form the basic unit of society in Najdi culture. Extended families often gather together in a neighborhood and establish their own private (hella) residential area. The family unit typically consists of one or more families stemming from a common parent residing in the same dwelling or group of connected houses [81,82].

The concept of Al-Shuf’a primarily applies at the level of granting residents the ability to shape their living spaces according to their social and personal requirements. This principle plays a role in establishing a stable spatial organization closely tied to the social structure and interconnected circles within the Najdi community. By allowing neighbors precedence in purchasing available homes, the central circle of social ties (extended family) can endure spatially across generations.

To visually grasp the Al-Shuf’a and Haq Al-Irtifaq mechanisms, two scenarios in Al Khabra showcase how these principles impact the organization at the hella level. The illustration is to record the mechanisms that influence social interactions and community cohesion within the neighborhood. The significance of these scenarios is to provide a deeper understanding of how these mechanisms shape the dynamics of everyday life in Al Khabra, highlighting the importance of traditional design principles in fostering a sense of belonging and connection among residents. Figure 9 shows how the hella can flexibly expand or shrink based on these principles influencing the concept of hidden (virtual) boundaries. Additionally, considering how individual property transactions among neighbors influence the size of the hella area, it is possible to grasp how this process reshapes private paths or cul-de-sacs while upholding spatial order, regardless of the original social structure.

Figure 9.

Experimental scenarios from Alkhabra town showcasing the flexibility of Najdi urban principles on urban organization. Source: Authors.

Finally, the spatial order, social structure, and Islamic principles in the traditional Najdi towns all aim to preserve the level of homogeneity in the community and its built environment. They give priority to neighbors living in close proximity to purchase surrounding properties to maintain order and prevent external interruptions. They serve as tools for carrying out the generation process by facilitating communication between different urban areas or how to divide homes and offer solutions for connecting houses that are part of neighboring areas. This is significant, as they ensure that the community remains cohesive and united, with a strong sense of belonging and shared responsibility. By adapting to these tools, each traditional Najdi town was able to maintain its unique character and cultural heritage for future generations.

6. Conclusions

This study of traditional Najdi settlements reveals the tight relationship between spatial dynamics and social order, particularly through the concept of the ‘hella’—the neighborhood. It has been established that these towns’ hierarchical spatial arrangement has a major impact on decision-making processes at many levels. The findings show that public spaces monitored by authorities and private residential areas maintained by residents collaborate to create subtle boundaries that play an important role in creating social relationships and defining urban layouts. This study underlines the significance of these borders in sustaining peace and shows how decisions made in both small and large dimensions help to define the urban form and social cohesiveness of Najdi towns.

Furthermore, the study highlights the difficulty of integrating urban expansion with the remaining traditional values embedded in Najdi architectural and societal traditions. The intricate urban arrangement, noted for its resilience to changing conditions and respect for communal values, provides insight into the sustainable design principles inherent in traditional architecture. The study provides insights into sustainable urban planning and heritage conservation by emphasizing traditional Najdi settlements as emblems of cultural resilience and flexibility. Looking ahead, future research could examine how these findings can be applied to urban planning in the face of rapid technological breakthroughs and changing social dynamics. There is potential to apply principles from these traditional Saudi settlements, such as neighborhood clustering and social order maintenance, to address urban sprawl, social fragmentation, and environmental difficulties in today’s cities around the world.

In the face of modernization (global cultural homogenization) and urbanization, traditional Arab neighborhoods face significant challenges in preserving their unique socio-spatial fabric. Contemporary urban development pressures have led to transformations in the physical and social landscapes of these neighborhoods, raising concerns about the erosion of cultural heritage and community cohesion. In terms of historical conservation, there is an increasing demand for policies that protect not only the physical structures of Najdi towns but also their intangible cultural legacy. Future conservation initiatives might prioritize community involvement to ensure that development plans take into account individual perspectives and desires as well as top-down policies. Researchers could explore sustainable conservation strategies that respect the historical integrity of these neighborhoods while accommodating modern living requirements. This may underscore the importance of a balanced approach that integrates traditional urban principles with contemporary design interventions to ensure the vitality and relevance of these neighborhoods in today’s urban context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.A.; methodology, M.M.A. and E.N.; software, M.M.A.; validation, M.M.A. and E.N.; formal analysis, M.M.A. and E.N.; investigation, M.M.A.; resources, M.M.A.; data curation, M.M.A. and E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.M.A. and E.N.; visualization, M.M.A. and E.N.; supervision, M.M.A.; project administration, M.M.A.; funding acquisition, M.M.A. and E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the study town residents’ willingness to interview and support this article. We also thank individuals for their assistance in performing the field research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dabbour, L. The traditional Arab Islamic city: The structure of neighborhood quarters. J. Archit. Urban. 2021, 45, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbour, L.M. Morphology of quarters in traditional Arab Islamic city: A case of the traditional city of Damascus. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, N. Islamicate urbanism: The state of the art. Built Environ. 2002, 28, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaim, M.M. The hierarchical order of spaces in Arab traditional towns: The case of Najd, Saudi Arabia. World J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 8, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.D.; Tannous, H.O. Form and function in two traditional markets of the Middle East: Souq Mutrah and Souq Waqif. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, D.H.I.L. Cairo: An Arab city transforming from Islamic urban planning to globalization. Cities 2021, 117, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, I.A.; Farhan, S.L.; Al-Maliki, L.A.; Al-Mamoori, S.K. Climatic Treatments for Housing in the Traditional Holy Cities: A Comparison between Najaf and Yazd Cities. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 754, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E. Orientalism Pantheon Books; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 1973, 4, 637. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R.; Faggion, L. Urban Regeneration of GCC Cities: Preserving the Urban Fabric’s Cultural Heritage and Social Complexity. J. Hist. Archaeol. Anthr. Sci. 2017, 1, 00004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Galès, T.; Vitale, T.; Governing the Large Metropolis. A Research Agenda. 2013. Available online: https://sciencespo.hal.science/hal-01070523/document (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Hakim, B.S. Reviving the Rule System: An approach for revitalizing traditional towns in Maghrib. Cities 2001, 18, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, B.S. The” Urf” and its role in diversifying the architecture of traditional Islamic cities. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 1994, 11, 108–127. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaim, M.M.; Albaqawy, G.; Bay, M.; Mesloub, A. The impact of generative principles on the traditional Islamic built environment: The context of the Saudi Arabian built environment. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, T. Regulation by incentives, regulation of the incentives in urban policies. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2010, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNaim, M.M. Dwelling form and culture in the traditional Najdi built environment, Saudi Arabia. Open House Int. 2021, 46, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Yunitsyna, A.; Shtepani, E. Investigating the socio-spatial relations of the built environment using the Space Syntax analysis—A case study of Tirana City. Cities 2023, 133, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudi-Mindermann, H.; White, M.; Roczen, J.; Riedel, N.; Dreger, S.; Bolte, G. Integrating the social environment with an equity perspective into the exposome paradigm: A new conceptual framework of the Social Exposome. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geddes, I.; Chatzichristou, C.; Charalambous, N.; Ricchiardi, A. Agency within Neighborhoods: Multi-Scalar Relations between Urban Form and Social Actors. Land 2024, 13, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Determann, J. Architectural heritage in Saudi Arabia: From the dynasty to the nation. In Proceedings of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, London, UK, 15 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hasani, M.K. Urban space transformation in old city of Baghdad–integration and management. Megaron 2012, 7, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saaidy, H.J. Lessons from Baghdad city conformation and essence. In Sustainability in Urban Planning and Design; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.S.; Al-Dujaili, S.H.A. Historical paths and the growth of Baghdad Old Center. J. Eng. 2013, 19, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadoon, W. Rebuilding Baghdad: A Half-Century of International Urban Plans for the Historic Capital of Iraq; SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saffar, N. Studying Urban Geometric Characteristics in the Downtowns of Baghdad, Iraq; University of Baghdad: Baghdad, Iraq, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elmenshawy, A.; El-Shihy, A. Management of World Heritage Sites: A Case Study of Historic Cairo. J. Urban Res. 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovella, N.; Aly, N.; Comite, V.; Ruffolo, S.A.; Ricca, M.; Fermo, P.; de Buergo, M.A.; La Russa, M.F. A methodological approach to define the state of conservation of the stone materials used in the Cairo historical heritage (Egypt). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaffar, N.H.; Alobaydi, D. Studying street configurations and land-uses in the downtown of Baghdad. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2651, 020064. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouche, M.B. Can chaos theory explain complexity in urban fabric? Applications in traditional Muslim settlements. Nexus Netw. J. Archit. Math. Struct. 2009, 11, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, M.G. The Architecture of Home in Cairo: Socio-Spatial Practice of the Hawari’s Everyday Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saffar, M. Baghdad: The city of cultural heritage and monumental Islamic architecture. Disegnarecon 2020, 13, 14.1–14.15. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saffar, M. Assessment of the process of urban transformation in Baghdad city form and function. In Proceedings of the 24th ISUF International Conference: City and Territory in the Globalization Age, Valencia, Spain, 27–29 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, N. Architecture and Urban Transformation of Historical Markets: Cases from the Middle East and North Africa; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- AlOboudi, S.M. NAJD, The heart of Arabia. Arab Stud. Q. 2015, 37, 282–299. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh Almansuri, D.; Alkinani, A.S. Place Identity and Urban Uniqueness: Insights from the Al-Rusafa Area; University of Baghdad: Baghdad, Iraq, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Al-arab, N.K.I.; Abbawi, R.F.N. Revitalizing Urban Heritage for Tourism Development: A Case Study of Baghdad’s Old City Center. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.A.; Hussein, S.H. Unveiling Baghdad’s Urban Identity: A Comprehensive Study on the Dynamics of Urban Imprint. Academia Open 2024, 9, 8238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabar, O. Cairo: The History and the Heritage. the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, the Expanding Metropolis: Coping with the Urban Growth of Cairo; Concept Media Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El Aziz, N. Historic identity transformation in cultural heritage sites the story of Orman Historical Garden in Cairo City, Egypt. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 12, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNuaimy, L.R. Morphological Evolution of Hit Historic Center: Analyzing the Urban Structures; University of Baghdad: Baghdad, Iraq, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Magdi, S.A.; Ibrahim, M.E. Towards a compatible methodology for Urban Heritage sustainable development A case study of Cairo Historical Center-Egypt. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Bus. Sci. 2023, 4, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondolf, G.M.; Louise, M.; Rachel, M.; Krishnachandran, B.; Amir, G.; Linda, J.; Sabri, S.S.; Ahmed, S.; Noha, A.; Tami, C. Connecting Cairo to the Nile: Renewing Life and Heritage on the River; Working Paper; University of California, Institute of Urban and Regional Development (IURD): Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rovella, N.; Aly, N.; Comite, V.; Randazzo, L.; Fermo, P.; Barca, D.; de Buergo, M.A.; La Russa, M.F. The environmental impact of air pollution on the built heritage of historic Cairo (Egypt). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bastawisy, M. Environmental influence on the built heritage, Saudi Arabia regions. Rendiconti Lincei. Sci. Fis. E Nat. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundher, R.; Al-Sharaa, A.; Al-Helli, M.; Gao, H.; Abu Bakar, S. Visual quality assessment of historical street scenes: A case study of the first “Real” street established in Baghdad. Heritage 2022, 5, 3680–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, D.S.I. Reaccessing marginalized heritage sites in historic Cairo: A cross-case comparison. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M. Urban Elements in the Saudi Arabian Najd Region and their Influence on Creating Threshold Spaces. J. Public Space 2021, 6, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dioji, M.; Musa, E. Contextual Integration in Iraqi City Center Development Projects. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 9, 182–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sedky, A. Living with Heritage in Cairo: Area Conservation in the Arab-Islamic City; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, J.; Lofland, L.H. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan, H.K. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2018, 7, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W. Conzenian urban morphology and urban landscapes. In Proceedings of the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium, Istanbul, Turkey, 12–15 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, V.; Yaygın, M.A. The concept of the morphological region: Developments and prospects. Urban Morphol. 2020, 24, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D. Phenomenology, place, environment, and architecture: A review of the literature. Phenomenol. Online 2000, 36, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Allweil, Y. Beyond the Spatial Turn: Architectural History at the Intersection of the Social Sciences and Built Form; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M. On space syntax as a configurational theory of architecture from a situated observer’s viewpoint. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2012, 39, 732–754. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Claramunt, C. Integration of space syntax into GIS: New perspectives for urban morphology. Trans. GIS 2002, 6, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, M.A.; Alanaim, M.M.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Noaime, E. The Heritage Jewel of Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Analysis of the Heritage Management and Development Activities in the At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS). Sustainability 2022, 14, 10718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naim, M.A. Riyadh: A City of ‘Institutional’architecture, in The Evolving Arab City; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 132–165. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheshtawy, Y. Riyadh: Transforming a Desert City; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Altassan, A. Sustainability of Heritage Villages through Eco-Tourism Investment (Case Study: Al-Khabra Village, Saudi Arabia). Sustainability 2023, 15, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M. Searching for Urban and Architectural Core Forms in the Traditional Najdi Built Environment of the Central Region of Saudi Arabia; University of Colorado at Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GEOSA. Official Map of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2024. Available online: https://www.geosa.gov.sa/En/Products/PublicMaps/pages/official-map-of-the-kingdom-of-saudi-arabia.aspx (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Hong, S.W.; Schaumann, D.; Kalay, Y.E. Human behavior simulation in architectural design projects: An observational study in an academic course. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2016, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, R.M.; Stea, D. Image and Environment: Cognitive Mapping and Spatial Behavior; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, K. A configurational approach to analytical urban design:‘Space syntax’methodology. Urban Des. Int. 2012, 17, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliynyk, O.; Troshkina, O. Analysis of architectural urban spaces based on space syntax and scenario methods. Spatium 2023, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M. Discovering the Integrative Spatial and Physical Order in Traditional Arab Towns: A Study of Five Traditional Najdi Settlements of Saudi Arabia. J. Archit. Plan. 2022, 34, 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, B.S. Arabic-Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles. In Kegan Paul International, London. Hatam, Gholamali (2000); Islamic Architecture in Saljugi Period, Majed publication: Tehran, Iran, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hathloul, S.A. The Arab-Muslim City: Tradition, Continuity, and Change in the Physical Environment; Dar Al-Sahan: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, L.; Chatford, D.L.; Sahbaz, O.; Haklay, M. Space and exclusion: Does urban morphology play a part in social deprivation? Area 2005, 37, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social identification, self-categorization and social influence. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 1, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Le Galès, T. Vitale, Assimilation, security, and borders in the member States. In Reconfiguring European States in Crisis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 428–450. [Google Scholar]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Revealing distinguishing factors between Space and Place in urban design literature. J. Urban Des. 2021, 26, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naim, M.A. The Home Environment in Saudi Arabia and Gulf States; Research Center on Mediterranean, University for Foreigners Dante Alighieri: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jomah, H.A.S.M. The Traditional Process of Producing a House in Arabia during the 18th and 19th Centuries: A Case-Study of Hedjaz; University of Edinburgh: Scotland, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hatloul, S. Arabic Islamic Cities: Legislation as Instrumental in Shaping the Urban Environment; Umran Alulom: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. House Form and Culture; Prentice Hall Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarak, F.A. Urban growth boundary policy and residential suburbanization: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Habitat Int. 2004, 28, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haroun, Y.; Al-Ajmi, M. Understanding socio-cultural spaces between the Hadhar and Badu houses in Kuwait. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2018, 12, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).