Abstract

Public participation in environmental governance plays a pivotal role in fostering a healthy and sustainable relationship between society and the environment. Despite the convenience afforded by the internet, the level of participation among Chinese citizens remains notably low. Thus, enhancing public enthusiasm for environmental governance is imperative, particularly given the paucity of academic research in this area. To address this gap, we employed the volume of messages on a leadership message board as a proxy for measuring the motivation behind public participation in environmental governance. Utilizing a provincial panel regression analysis, we investigated the determinants of public participation and subsequently conducted a mechanism analysis. Our findings reveal that deteriorating local air quality correlates with heightened motivation for public involvement in environmental governance. Additionally, increased public attention to environmental issues significantly amplifies this motivation, with the availability of internet access and the degree of emphasis placed by local governments on public participation further facilitating this process. This study contributes a theoretical and empirical foundation for enhancing public engagement in environmental governance, thereby fostering the development of a sustainable society.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary era, environmental issues have evolved into global challenges with profound implications for human society, economic progress, and ecological equilibrium. Predicaments such as global climate change, biodiversity depletion, and air and water contamination not only jeopardize human survival and development but also escalate the fragility of Earth’s ecosystems, imposing severe repercussions on human health [1,2], societal productivity [3,4], and welfare [5,6]. As one of the world’s most populous nations, China confronts particularly acute environmental hurdles. The nation’s rapid industrialization in recent decades has coincided with escalated energy consumption and environmental degradation, underscoring the growing significance of environmental preservation within national development agendas.

To address environmental adversities, governments worldwide have increasingly adopted policy measures aimed at curbing pollution by fostering grassroots participation in environmental governance. Indeed, as early as the 1980s, the United States initiated efforts to engage citizens, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), shareholders, and the media in environmental enforcement, exemplified by the introduction of the toxic release inventory (TRI), mandating companies to publicly disclose their toxic emissions. Over the ensuing three and a half decades, analogous programs have proliferated across numerous nations, including Canada, China, India, and Indonesia. These initiatives, while intensifying the regulatory oversight of businesses, have also fostered the establishment of official communication channels, encouraging public involvement in environmental governance and the active reporting of pollution incidents and violations of emission standards to governmental authorities.

In recent years, the Chinese government has increasingly prioritized environmental issues and encouraged public involvement in environmental governance. China’s approach to sustainable development underscores the need for a harmonious balance between economic growth and environmental conservation. While the government plays a central role in formulating policies and regulations and providing institutional frameworks for sustainable development, active public participation is equally vital. Without robust public engagement, achieving sustainable development goals becomes challenging. Therefore, it is essential to promote the widespread understanding and acceptance of the concept of sustainable development among the public. When this concept becomes ingrained in public values and beliefs, individuals are more likely to actively participate in sustainable development initiatives. Through collaborative efforts between the government and the public, China can effectively realize its sustainable development objectives, thereby laying a solid foundation for future progress [7]. Leveraging the advent of the internet and digital technologies, the government has enhanced its operational efficiency and governance efficacy [8] while also facilitating more accessible avenues for public engagement in environmental affairs, such as Weibo [9], WeChat, and the local leaders’ message board [10]. The infrastructure for public involvement in environmental governance is firmly in place, enabling Chinese citizens to promptly report environmental issues to authorities through online platforms upon encountering pollution or suspected illegal discharges. For instance, a scholarly experiment revealed that upon discovering pollution incidents, over 300,000 Chinese individuals lodged complaints with sewage companies and government regulatory accounts via microblogs [9]. Additionally, the local leaders’ message boards received nearly 140,000 complaints during the five-year period from 2017 to 2021, underscoring the efficacy of online platforms in facilitating public participation in environmental governance.

Despite efforts by the Chinese government to promote public participation in environmental governance, the level of public engagement remains relatively low considering the country’s vast population. The slow development of public participation in environmental governance in China can be attributed to various factors. Scholars suggest that there exists a certain level of political “alienation” within Chinese society [11], where individuals may feel disconnected or disengaged from participating in social governance [12]. Additionally, many individuals lack awareness of the importance of active involvement in social issues, including environmental governance. According to the ladder theory of civic participation [13], the majority of the Chinese public’s political participation tends to be limited to lower levels, such as manipulation, treatment, informing, and counseling, falling short of higher levels of engagement. This phenomenon may be influenced by cultural and historical factors, as traditional Chinese beliefs often place the responsibility for governance squarely on the government [7], thereby reducing the public’s inclination to participate actively in environmental governance [14,15]. Moreover, studies conducted in rural areas have revealed that a significant barrier to public participation in environmental governance is the lack of understanding among local residents regarding the significance of their involvement and how to effectively engage in governance processes [16]. This lack of awareness contributes to a general indifference toward environmental issues among the Chinese population. The attention theory suggests that when individuals are inundated with information, they tend to focus selectively, leading to limited attention spans, which in turn influence decision-making behavior [17]. Consequently, the scant attention given to environmental governance may underpin the limited scale of public participation. However, since there have been limited scholarly inquiries into how to motivate people to participate in environmental governance based on the attention theory, it remains uncertain whether enhancing public attention can spur greater involvement in environmental governance.

To harness the potential of public involvement, the government must maximize incentives for participation. Enhancing public motivation to engage in environmental governance is therefore a critical issue. There are limited current studies examining the relationship between public attention and participation in environmental governance. For instance, does heightened public attention to environmental governance increase public motivation to participate? Moreover, what factors influence this process? Given the relatively low scale of public participation in environmental governance in China, there is an urgent need for scholarly research on strategies to increase it. This study aims to address this gap by empirically investigating the factors affecting public participation in environmental governance based on attention theory and conducting a mechanism analysis. We focused on the number of environmental complaints filed by Chinese citizens on local leaders’ message boards from 2017 to 2021 as the primary research subject. It analyzes factors influencing public participation in environmental governance. Additionally, it utilizes Baidu search index data related to environmental governance to gauge public attention. Specifically, it examines whether public attention can bolster citizens’ motivation to participate in environmental governance and explores factors that influence this relationship. The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 summarizes the related literature; Section 3 introduces data source; Section 4 describes the methodology; Section 5 presents empirical results; Section 6 provides the discussion, including policy implications; and Section 7 sets out the conclusions.

2. Literature Review

Public participation in environmental governance encompasses two primary forms of behavior. First, individuals engage in personal environmental protection measures, such as conserving energy and refraining from littering. Second, the public plays a vital role in reporting instances of pollution to the government and highlighting abnormal environmental conditions in their surroundings. Given the government’s prominent role in environmental protection, decisions with significant implications for environmental quality are typically made by governmental bodies. However, many polluting activities occur clandestinely, prompting groups of citizens adversely affected by pollution to report such behaviors to the authorities. This is why bottom-up citizen involvement in environmental governance has been encouraged globally since the 1980s [18,19].

In China, traditional modes of public participation in environmental governance typically involve reporting via phone or proposals to the National People’s Congress [20], which are often inefficient. Consequently, public protests frequently ensue when faced with severe environmental issues, as evidenced by mass demonstrations against proposed projects such as waste incineration and paraxylene (PX) plants in Guangzhou City [21,22,23]. Advancements in digital technology, particularly information and communication technology (ICT), have revolutionized the accessibility, storage, transmission, management, and dissemination of information to a wide audience, spanning a significant portion of the global population. As such, ICT is recognized as a catalyst for promoting sustainable development. Leveraging ICT, the Chinese government has established various online platforms to facilitate citizen participation in environmental governance [24,25]. Through these platforms, including social media and other online channels, the public can readily report environmental violations. Moreover, the Chinese government is actively implementing measures to encourage greater public involvement in environmental decision-making, including the enactment of laws and regulations, such as the Environmental Impact Assessment Law and the Environmental Protection Law [26,27].

As an emerging avenue for public participation in environmental governance, the effectiveness of lodging complaints on internet platforms remains a question. Some scholars have observed that public complaints effectively convey information to the government and prompt polluting enterprises to reduce pollution emissions. They noted a positive correlation between the level of public concern and the frequency of complaints, highlighting the significance of public involvement in environmental governance [9]. Public feedback on environmental issues can lead local governments to introduce more administrative regulations on environmental governance, underscoring the importance of public participation [20]. Studies have also found that public engagement in environmental governance can significantly enhance local regional environmental quality [28] and have a significant negative impact on pollution emissions, contributing to the effectiveness of environmental governance [29]. However, challenges persist. For instance, an eight-month trial of residential public participation in maintaining the community environment in Kampala, Uganda, where citizens reported waste disposal via SMS, did not significantly result in a better community environment despite the use of information and communication technology (ICT) [30]. In China, public participation in environmental governance remains low despite the existence of hundreds of thousands of reports on microblogs and leadership message boards. This could be attributed to political “alienation” in Chinese society, where some individuals lack awareness to actively participate in social governance [11]. Despite these challenges, there is limited research on how to enhance public participation. Some scholars found that increasing people’s awareness of public participation and their sense of belonging to the community environment may increase their willingness to engage [31]. Others found that the public’s concern about environmental issues and the government’s provision of more channels for public participation could increase motivation for participation in environmental governance [15]. However, there is a dearth of empirical analyses examining what should be done to increase public motivation to participate in environmental governance. As people become more concerned about the environment, their motivation to improve it increases, particularly in cities with high air pollution. Research shows that the public in areas with significant air pollution is more inclined to express a desire for environmental control [14]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Worsening local environmental quality corresponds to increased public participation in environmental governance.

Reduced motivation for public participation in environmental governance as a decision-making behavior may indeed stem from a lack of attention given to environmental issues. Rational attention theory posits that due to the constraints of limited attention, public decision-making and behavior tend to concentrate on focal points of concern [17]. Consequently, a pivotal strategy for augmenting public participation in environmental governance may involve capturing the public’s attention.

In fact, the attention perspective is a current academic hotspot, with research related to public attention applied across numerous fields, including politics and public administration [32], epidemiology [33,34], economic activities [35], asset pricing [36], financial securities [37,38,39,40], inflation expectations [41], GDP forecasting [42], and more. Some scholars have also found that public attention to environmental problems can prompt the government to address them more promptly [9]. Through extensive studies, scholars have found that public attention can indeed effectively influence asset prices, macro expectations, and other focal points of attention, further validating the rational attention theory and underscoring the importance of public attention. Therefore, in line with attention theory, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Public attention to environmental governance will enhance the enthusiasm for public participation in environmental governance.

It is important to acknowledge that not all attention translates into actual participation. Shipeng et al. (2018) [16] found that while some individuals express a strong willingness to participate in environmental governance, the actual participation rate remains low, indicating a gap between public attention and action. In the digital age, governments are increasingly relying on online platforms for public feedback and communication [18,19]. However, inadequate internet infrastructure can hinder citizens with a strong desire to participate in environmental governance from engaging on these platforms. Moreover, given the predominant role of governments in environmental governance, effective public participation often involves reporting environmental issues to authorities to address regulatory gaps. A responsive government that listens to public feedback and takes appropriate action can foster public trust, thereby enhancing willingness to participate in environmental governance [31]. Based on these considerations, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2A.

Greater ICT infrastructure will facilitate the conversion of public concern into participation.

Hypothesis 2B.

Increased government attention to public feedback will facilitate the conversion of public concern into participation.

3. Variables and Data Sources

3.1. Public Participation in Environmental Governance

This paper utilizes the number of messages left by the public on local leaders’ message boards in the realm of environmental issues as a metric to gauge the public’s active participation in environmental governance [10]. Established in August 2006, the leadership message board serves as a national inquiry platform for netizens to voice their demands, articulate concerns, and offer opinions and suggestions, with governmental agencies tasked with addressing and responding to these inputs.

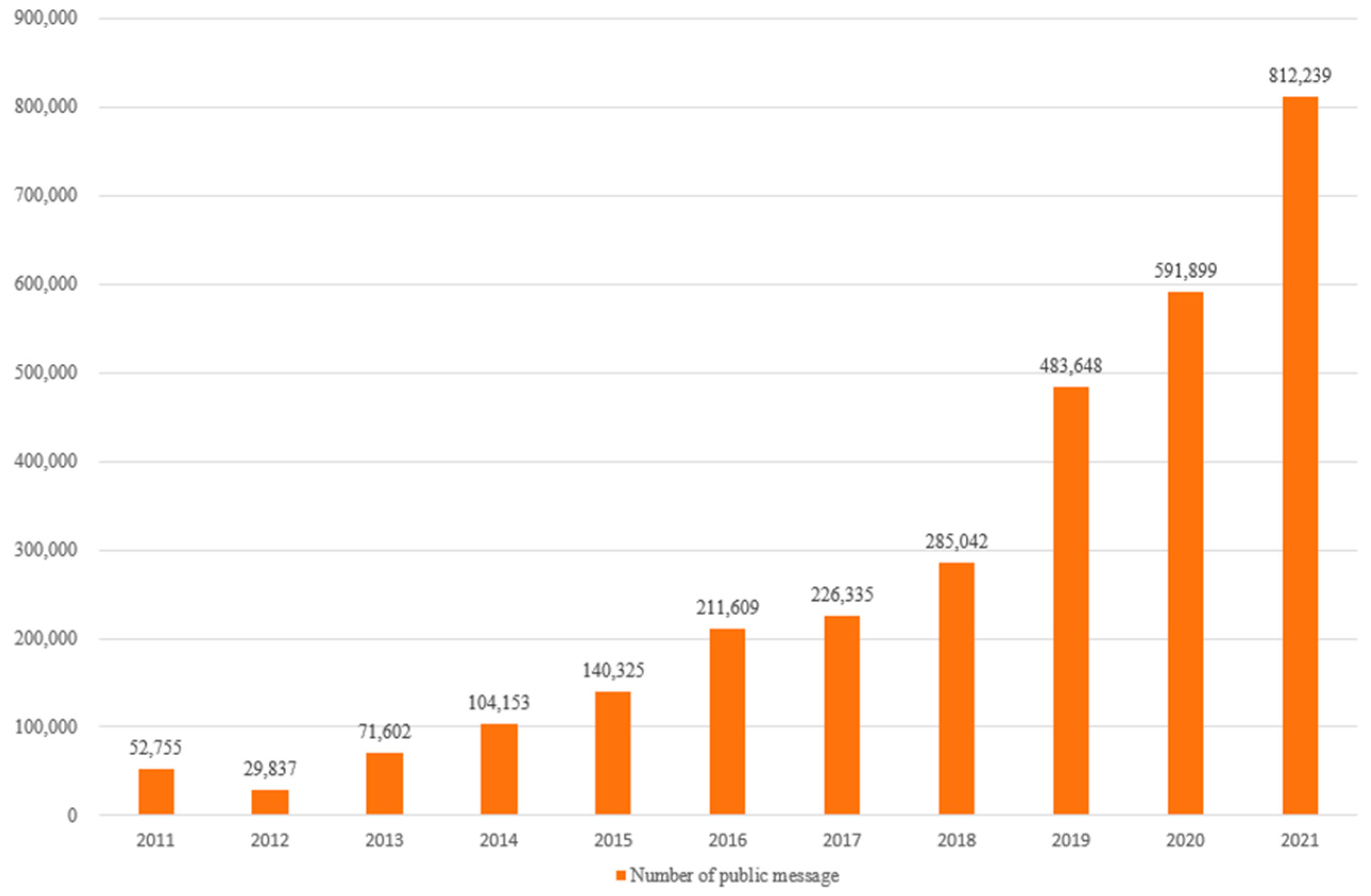

Given the attention and directives from the state, local governments at all levels have issued directives mandating increased engagement with the leadership message board. Consequently, it has evolved into an effective avenue for the public to express their demands and engage in governance. This heightened attention has led to a steady increase in the volume of public messages over the years, with over 810,000 messages in all fields recorded in 2021 alone (as depicted in Figure 1). These messages originate from various levels of government, including provincial, municipal, and county administrations, as well as diverse departments, such as party committees, government agencies, and departments handling public grievances. This inclusive and multi-level governmental response system provides practical support and institutional mechanisms for citizen participation. A total of 138,809 public messages concerning environmental issues were gathered from the CnOpenData database for the five-year period spanning from 2017 to 2021. This timeframe was selected because the leadership message board, although operational before 2017, did not wield significant influence, as illustrated in Figure 1. This can be attributed to the fact that since 2016, governments at various levels have started issuing official directives concerning the leadership message board. For instance, the General Office of the People’s Government of Gansu Province released the Implementation Measures for the Handling of Messages from Netizens. Subsequently, there was a notable uptick in the number of messages posted on the board, underscoring its growing social impact. Due to constraints in data availability, complete message data was only accessible up to 2021. Consequently, the sample period for this study was restricted to 2017–2021.

Figure 1.

Number of public messages on the local leaders’ message board.

3.2. Public Attention to Environmental Governance

In the contemporary era, the widespread use of search engines has significantly reshaped the public’s information acquisition and cognitive behavior, with search engines and the internet serving as external memory resources for the public [43]. Consequently, public attention towards specific topics is often reflected in interactions with internet search engines, with search engine data serving as a valuable indicator of public attention.

Baidu Search has maintained a dominant position in the Chinese search engine market since its establishment in 2001. According to the Global Digital Report 2021 by StatCounter, an authoritative international market research organization, Baidu commands an impressive 85.48% market share in China’s search engine market, highlighting its prominent role in the country’s digital landscape. Additionally, Baidu’s market dominance is evident in its search engine market share, surpassing 70%, and capturing a remarkable 78% share in the mobile search market. These statistics underscore Baidu’s pivotal position in China’s search engine market and emphasize the crucial role of search engines in facilitating public access to information.

The Baidu index, introduced in 2006, is a big data analytic service leveraging Baidu’s web search and news services. It enables the measurement and characterization of online search behavior among hundreds of millions of internet users. The Baidu index calculates the weighted sum of search frequency for specific keywords on Baidu webpages, reflecting netizens’ information access, topic popularity, and user interest [44,45]. Collaborating with the official Baidu index, we obtained Baidu index data for several keywords related to environmental governance, including “environmental governance”, “public participation in environmental governance”, “pollution”, and “haze”. The Baidu search index is calculated using a linear method based on specific search data for individual keywords. For this study, we aggregated Baidu indices corresponding to the aforementioned keywords to derive the index of public attention to environmental governance from January 2017 to May 2022 across 31 provinces in China.

3.3. Other Variables

We draw upon previous scholarly research on public participation in environmental governance to inform our selection of control variables, which are categorized into two dimensions: regional characteristics and demographic characteristics. Regional characteristics encompass variables such as the regional economic level [28], population size [28], and air quality [9,46]. Demographic variables include the economic level per capita [46], educational attainment [14,31], the proportion of elderly population, and ICT accessibility [24]. The specific selection and measurement of variables are detailed in Table 1, with all data sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook.

Table 1.

Variable measurement and descriptive statistics.

4. Methodology

The methodology employed in this study involved three sequential steps for comprehensive data collection and analysis. Initially, data retrieval was conducted through various sources. The CnOpenData database served as a primary resource for extracting the number of messages posted on local leaders’ message boards addressing environmental governance concerns. Simultaneously, collaboration with the official Baidu index organization facilitated the acquisition of Baidu index data related to environmental governance, enabling the calculation of public attention towards environmental issues. Additionally, vital data on the regional economic and demographic characteristics of Chinese provinces were meticulously collected from the China Statistical Yearbook. Furthermore, air pollutant emission data were meticulously gathered and processed to derive essential air quality variables necessary for the study’s analysis.

In the second step, we constructed an empirical model, as depicted in Equation (1), where i represents the province and t denotes the year. Utilizing provincial panel regression, we explored the potential impact of public attention to environmental governance (Concern) on the level of public participation in environmental governance (PPEG). Additionally, we analyzed the influence of various factors among the control variables on PPEG.

The third step involved conducting a mechanism analysis to examine the factors that influenced the transformation of public attention to environmental governance into actual participation in environmental governance actions. Not all concerns can translate into actions; while many individuals may be initially attracted to the message of environmental governance and express willingness to participate through online platforms, various factors may impede their actual engagement. For instance, issues such as the local internet penetration level and the extent to which local governments prioritize public participation in environmental governance can affect individuals’ ability to effectively engage in online platforms for environmental governance. If the local internet penetration level is inadequate, individuals may find it challenging to participate in environmental governance activities online despite their concerns. Similarly, if the local government does not prioritize public participation in environmental governance, individuals may perceive online platforms as ineffective channels for providing feedback on environmental issues, thus discouraging their participation. To explore which variables (X) moderate the process of translating public concern into participation, we incorporated the cross-multiplication term of X with public attention into the model, as represented in Equation (2). We focused on the coefficient of the cross-multiplier term; if this coefficient was not significant, then the variable X was not a mechanism variable. However, if the coefficient was significant and positive, it indicated that a higher level of the mechanism variable X corresponded to a higher level of motivation for public participation and vice versa.

The fourth step involved conducting a robustness test using a spatial econometric model. Recognizing the potential spatial spillover effects between neighboring provinces, we augmented the model by incorporating a spatial matrix to account for these effects. This allowed for an analysis of the factors influencing public motivation to participate in environmental governance while considering spatial effects. Following the likelihood ratio test, we selected the spatial Durbin model (SDM) with both fixed time and individual fixed effects, as illustrated in Equation (3). Here, w denotes the weight matrix, and Z represents all explanatory variables along with the cross-multiplication term.

It is important to highlight that all empirical analyses were conducted using Stata 15, a statistical software package known for its robust capabilities in data analysis and modeling.

5. Results

5.1. Baseline Test

To investigate the impact of economic development and environmental quality on public participation in environmental governance as well as the potential role of public attention in enhancing participation enthusiasm, provincial panel regression analyses were conducted based on Equation (1). The empirical results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors influencing public participation in environmental governance.

In column (1) of Table 2, representing the base regression, the coefficient of “Concern” is found to be significantly positive, even after controlling only for temporal characteristics fixed effects and province fixed effects. This conclusion remains consistent upon the inclusion of regional characteristic control variables, demographic characteristic control variables, and all control variables in columns (2), (3), and (4), respectively. Moreover, the coefficient of “air quality pollution” also emerges as significant. This finding indicates that the public’s motivation to engage in environmental governance significantly increases when local air quality deteriorates. This observation is logical, as higher local air quality typically signifies better environmental conditions, resulting in fewer environmental issues prompting public feedback.

These empirical findings validate the effectiveness of the attention theory in shaping public participation in environmental governance. Specifically, they confirm that public attention to environmental governance significantly amplifies enthusiasm for public participation in environmental governance. Furthermore, the study highlights that the growth of public attention to environmental governance can be effectively translated into tangible participation in environmental governance activities.

5.2. Mechanisms

As observed in the preceding section, public attention to environmental governance has a positive impact on increasing public participation in environmental governance. However, to understand the factors influencing this process, we conducted tests by incorporating control variables with “CONCERN” as cross-multiplier terms in Equation (2), represented as the X variables. The empirical results of these analyses are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mechanism analysis: internet penetration level.

Through an analysis of Table 3, it is evident that only the coefficient of Xconcern in column (1) exhibits significant positivity. This indicates that among all the control variables, only the level of internet penetration (ICT) exerts a significant positive moderating effect. Despite the coefficient of concern being −0.067, when considering the moderating effect of ICT and substituting the minimum value of ICT (0.42) and the mean value of ICT (0.64) into the model, the overall effect of concern on PPEG is consistently positive at 0.0052 and 0.0398, respectively. This finding aligns with previous conclusions, suggesting that higher levels of internet penetration facilitate the transformation of public attention to environmental governance into actual participation in environmental governance. In practical terms, this corresponds with the use of online platforms, such as local leaders’ message boards, as substitutes for public participation in environmental governance. A higher level of internet penetration increases the likelihood of the public engaging in environmental governance via online platforms.

Furthermore, we explore the influence of other factors on the transformation of public concern into public participation in environmental governance, with a particular emphasis on the role of government. The attention and responsiveness of local governments are crucial, as they play a key role in addressing and resolving public concerns, providing effective feedback on complaints, and reinforcing the significance of public participation in governance. In this study, the local government’s response to public participation in environmental governance on the leadership message board serves as a proxy for the government’s emphasis on public participation. The following variables are selected as indicators of government responses: the government’s problem handling rate (Banli), the handling rate (Jiaoban), the offline handling rate (U_Jiaoban), the average interval of the government’s response days (Days), and the average number of words in the government’s response (Nums). The specific meanings of these government response variables are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Government Response Variable Measurement and Descriptive Statistics.

By incorporating these mechanisms into Model 2, the empirical results are presented in Table 5. In Table 5, the coefficients of XConcern, which are of particular interest, are all significantly positive in columns (1)–(3). This indicates that the higher the handling rate, referral rate, and offline referral rate of the local government in response to public messages, the more effectively the public perceives the government’s emphasis on public participation in environmental governance. This fosters trust and confidence among the public, reinforcing the notion that government-led environmental governance initiatives are meaningful and worthy of their attention. With a positive reputation, the public’s concern about environmental governance is more efficiently translated into active participation in environmental governance. Specifically, individuals are more likely to provide feedback on the leader’s message boards and participate more actively in environmental governance initiatives.

Table 5.

Mechanism analysis: government’s response.

However, in column (4), the coefficient of the cross-multiplier term is not significant. This could be attributed to the fact that the Days variable, calculated based on government response time, does not necessarily reflect the quality or effectiveness of the government’s response. Even if the government responds promptly to messages, it does not guarantee that the underlying issues are adequately addressed. Therefore, a rapid response time alone may not enhance the public’s perception of government responsiveness, thus failing to influence public participation in environmental governance.

Interestingly, in column (5), the coefficient of the cross-multiplier term is significantly negative. This suggests that a higher word count in government responses impedes the transformation of public concern about governance policies into public participation. This phenomenon may stem from the inclusion of excessive and unnecessary information in government responses, leading to a dilution of the message’s effectiveness. An overly verbose response may leave message senders feeling unsatisfied or perfunctory, ultimately weakening their motivation to continue participating in environmental governance efforts.

5.3. Robustness

5.3.1. Lagged Impact Effects of Government Response Variables

To further validate the robustness of our findings, we consider the possibility that the public may base their decision to participate in environmental governance on the government’s response from the previous year. Therefore, we incorporate variables representing the previous year’s government response to public messages into Equation (2). These variables include whether the issue was handled (Banli_t1), whether it was handed over (Jiaoban_t1), whether it was handed over offline (U_Jiaoban_t1), the time interval between government responses (Days_t1), and the number of words in the government’s response (Nums_t1). The empirical results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Robustness: last year’s government response.

The empirical results in Table 6 reaffirm our previous conclusion that the level of emphasis placed by local governments on public participation in environmental governance positively influences the transformation of public attention into public participation. Importantly, this effect persists into the following year. Therefore, the findings from the robustness test underscore the significance of local government responsiveness in promoting public participation in environmental governance.

5.3.2. Spatial Econometric Model

Considering the spatial spillovers between neighboring provinces, the spatial econometric model is utilized to test the robustness of the regression results presented in this paper. We construct the spatial weight matrix using the inverse of the square of the distance between individual provincial capitals.

Initially, we assess and compare three spatial econometric models: the spatial lag model (SAR), spatial error model (SEM), and spatial Durbin model (SDM), using the likelihood ratio test (LR test). Ultimately, based on the LR test results, we select the SDM model, as demonstrated in Table 7.

Table 7.

Spatial econometric modelling tests.

Subsequently, we proceeded with the fixed-effects test of the model, comparing the individual fixed-effects model, the time fixed-effects model, and the mixed fixed-effects model with both time and individual fixed effects fixed simultaneously. Once again, after conducting the LR test, we ultimately selected the mixed fixed-effects model with both individual and time fixed effects, as indicated in Table 8.

Table 8.

Fixed-effects model test.

The final SDM model, incorporating both individual and time fixed effects, is presented in Table 9. It can be observed that the empirical findings remain consistent with the previous results, even after considering potential spatial effects. In column 1, local air pollution exhibits a significant negative correlation with public participation in environmental governance, while local public attention shows a significant positive correlation. Additionally, upon analyzing the coefficients of the cross-multiplier terms in columns 2–4, it is evident that high-quality ICT and the local government’s responsiveness to public participation enhance the translation of public concern into action. However, upon examining the coefficients of the spatial lagged variables, it becomes apparent that the spatial effect is not significant. The further analysis of the coefficients of SPATIAL RHO reveals that the spatial autocorrelation coefficient is also not significant. Therefore, we conclude that there is no significant spatial effect in the impact analysis of public participation in environmental governance.

Table 9.

Results of empirical tests of spatial econometric models.

6. Discussion

6.1. Impact of Air Quality on Public Participation Motivation

The analyses conducted in this study reveal a significant negative correlation between local air pollution levels and the motivation of residents to engage in environmental governance. Specifically, we found that as local air quality deteriorates, there is a corresponding increase in the motivation of the population to actively participate in environmental governance initiatives.

This finding aligns with the existing literature, where scholars have noted that the heightened awareness of the detrimental effects of air pollution, particularly in highly polluted urban areas, leads to increased public concern about environmental issues. Consequently, residents in regions with severe air pollution tend to exhibit greater enthusiasm for environmental governance activities [14]. This underscores the pivotal role of public participation in environmental governance, as it represents a voluntary action driven by individuals’ concerns for their own well-being and the environment. Furthermore, public engagement in environmental governance serves as a powerful mechanism to hold local governments accountable and prompt them to prioritize environmental protection measures. Failure to address environmental concerns effectively can escalate into significant social issues, highlighting the imperative for proactive government action in response to public demands for environmental stewardship.

6.2. Relationship between Public Concern and Public Participation

The fundamental empirical findings as well as the outcomes from spatial econometric analyses in the robustness test section consistently demonstrate a significant positive correlation between the level of local public concern for environmental governance and their propensity to engage in related activities. Specifically, our research reveals that heightened levels of local public interest in environmental governance, as evidenced by their online search behavior, are indicative of a greater likelihood of active involvement in addressing environmental issues through platforms such as the leadership message board.

This finding substantiates the attention theory, which posits that individuals’ actions are contingent upon their attention to relevant information. Extensive studies have underscored the pivotal role of attention in guiding human behavior, emphasizing that individuals can only act upon events or issues they are aware of [17,32,34,35]. Consequently, prior to active participation, individuals must first focus their attention on environmental governance and acquire relevant information. This aligns with findings by Shipeng et al. (2018) [16], who discovered low rates of public participation in water source protection in rural Fujian due to cognitive barriers, such as a lack of awareness regarding environmental governance. Scholars have highlighted the significance of environmental awareness and regulatory cognition in motivating public engagement, further underscoring the importance of public attention to environmental governance as a precursor to meaningful participation [14].

It is essential to acknowledge that not all levels of attention translate into active participation. Shipeng et al. (2018) [16] found instances where individuals expressed a strong desire to engage in environmental governance but exhibited low rates of actual participation, indicating a disparity between attention and action. To delve deeper into this phenomenon, we conducted a mechanism analysis to identify factors influencing the conversion of public concern into participatory behavior. Our empirical findings revealed that both local internet penetration and the extent of emphasis placed on public participation by local government play significant moderating roles. Specifically, higher levels of local government attention to public involvement coupled with greater internet penetration amplify the conversion of public attention into heightened motivation for environmental governance participation.

This aligns with real-world dynamics, where local governments wield substantial influence over public participation initiatives. When local authorities prioritize public involvement and demonstrate responsiveness to citizen input, it fosters a sense of efficacy among the public regarding participatory processes. Conversely, if the government’s response to public messages is perceived as inadequate or dismissive, it diminishes the perceived value of public participation efforts, thereby dampening public motivation to engage. Prior research has also highlighted the pivotal role of local governments in facilitating effective public participation [29]. Positive government responsiveness enhances the perceived significance of public engagement, encouraging greater citizen involvement in environmental governance. These findings echo the conclusions of Mannarini et al. (2010) [31], who identified a positive correlation between trust in the local government and public willingness to participate. Ultimately, active collaboration between the local government and citizens not only enhances the efficacy of public participation initiatives but also reinforces the public’s perception of their impact, thereby fostering sustained engagement in environmental governance efforts.

7. Conclusions

The current environmental challenges remain severe, underscoring the critical importance of public participation in environmental governance for establishing a sustainable society–environment relationship. While the advent of the internet has facilitated easier avenues for public engagement, the level of participation among Chinese citizens in environmental governance remains low. Thus, there is an urgent need to bolster public motivation and willingness to participate, requiring collaborative efforts between the government and society. Despite the growing recognition of the significance of public participation in environmental governance, academic research on this subject remains relatively sparse. To address this gap, we conducted an empirical study to investigate factors influencing public participation motivation and analyze associated mechanisms. Specifically, we utilized the number of messages on leadership message boards as a proxy for public enthusiasm for environmental governance participation and Baidu index data to gauge public attention to environmental governance. We employed a panel regression analysis and augmented the model with cross-multiplier terms. The main findings are as follows:

First, a significant negative correlation exists between the level of local air pollution and the enthusiasm of local residents to engage in environmental governance. Lower environmental quality in an area prompts individuals to recognize the inconveniences and health hazards posed by environmental issues, thereby motivating them to seek environmental improvements. Consequently, the public becomes more proactive in reporting environmental problems to the government and actively participating in environmental governance efforts.

Furthermore, there is a significant positive association between local public concern for environmental governance and their motivation to participate in such initiatives. Given the constraint of limited attention, individuals’ actions are guided by their focus. Therefore, increased motivation to engage in environmental governance is contingent upon individuals’ comprehension of fundamental environmental concepts, access to information on environmental governance, and understanding avenues for participation.

Lastly, higher levels of internet penetration in each region and greater importance attached to public participation by local governments enhance the conversion rate from public concern to active participation in environmental governance. Given that public engagement in environmental governance increasingly relies on online platforms, improved internet infrastructure facilitates easier feedback on environmental issues through digital channels. Additionally, the proactive involvement of local governments in responding to public feedback is crucial. Only when local authorities actively address citizen concerns will the public perceive the efficacy of environmental governance participation, thereby boosting enthusiasm for engagement. Conversely, if local governments overlook public feedback, no amount of attention can spur public participation in environmental governance.

To address these findings and facilitate enhanced public participation in environmental governance, several policy recommendations are proposed:

First, the government should intensify its efforts in promoting environmental governance awareness. In today’s information-rich society, it is easy for crucial messages to get lost amidst the noise. Hence, government initiatives promoting environmental governance should be genuine and impactful, ensuring that the public genuinely engages with the subject matter. Emphasizing the significance of public participation in environmental governance and providing clear guidance on how individuals can contribute should be central to such campaigns.

Furthermore, as the government pushes forward with digital transformation initiatives, it should prioritize the expansion of internet infrastructure. Without robust digital infrastructure, avenues for public participation in environmental governance will be limited, hindering the effectiveness of such efforts.

Lastly, there is a need for comprehensive training programs aimed at government officials at all levels. These programs should emphasize the importance of public participation in environmental governance and equip officials with the skills to respond efficiently to public feedback. Establishing a culture of responsiveness within government bodies is crucial to instilling confidence among the public that their concerns will be addressed effectively.

While this study provides valuable theoretical insights into improving public participation in environmental governance, there are some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the study primarily focuses on data from leadership message boards, overlooking other online platforms, such as microblogs and WeChat, that also serve as channels for public engagement in environmental governance. Second, future research should explore whether government publicity efforts impact public participation motivation by influencing attention levels. A textual analysis could be employed to measure the government’s communication of environmental governance policies, and mediation effects could be further examined through follow-up tests.

Funding

This study was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China, under grant No.21&ZD146.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The Baidu index data used in this article are obtained in cooperation with the Baidu Index Agency. All the other data adopted in this article are from public resources and have been cited with references accordingly.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ebenstein, A.; Fan, M.; Greenstone, M.; He, G.; Zhou, M. New Evidence on the Impact of Sustained Exposure to Air Pollution on Life Expectancy from China’s Huai River Policy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10384–10389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenstone, M.; Nilekani, J.; Pande, R.; Ryan, N.; Sudarshan, A.; Sugathan, A. Lower Pollution, Longer Lives: Life Expectancy Gains If India Reduced Particulate Matter Pollution. Econ. Political Wkly. 2015, 50, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Adhvaryu, A.R.; Kala, N.; Nyshadham, A. Management and Shocks to Worker Productivity: Evidence from Air Pollution Exposure in an Indian Garment Factory; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.; Graff Zivin, J.; Gross, T.; Neidell, M. Particulate Pollution and the Productivity of Pear Packers. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2016, 8, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. The Environmental and Economic Consequences of Internalizing Border Spillovers; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, K.; Zhang, S. Willingness to Pay for Clean Air: Evidence from Air Purifier Markets in China. J. Political Econ. 2020, 128, 1627–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xia, X.H.; Chen, B.; Sun, L. Public Participation in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals in China: Evidence from the Practice of Air Pollution Control. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Chen, K.; Kang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, X. Digital Technology Enables Construction of National Governance Modernization. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2022, 37, 1675–1685. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntaine, M.T.; Greenstone, M.; He, G.; Liu, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B. Does the Squeaky Wheel Get More Grease? The Direct and Indirect Effects of Citizen Participation on Environmental Governance in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2024, 114, 815–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Meng, T.; Zhang, Q. From Internet to Social Safety Net: The Policy Consequences of Online Participation in China. Governance 2019, 32, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y. Political Culture and Participation in the Chinese Countryside: Some Empirical Evidence. PS Political Sci. Politics 2004, 37, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Meng, T. Selective Responsiveness: Online Public Demands and Government Responsiveness in Authoritarian China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 59, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.C. Public Participation in Public Decisions, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-7879-0129-5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tilt, B. Public Engagements with Smog in Urban China: Knowledge, Trust, and Action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, J.; Li, D. Getting Their Voices Heard: Three Cases of Public Participation in Environmental Protection in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 98, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipeng, S.; Xin, L.; Ansheng, H.; Xiaoxia, S. Public Participation in Rural Environmental Governance around the Water Source of Xiqin Water Works in Fujian. J. Resour. Ecol. 2018, 9, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Reason in Human Affairs; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental Governance: Participatory, Multi-Level—And Effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M. Citizen Participation, Trust, and Literacy on Government Legitimacy: The Case of Environmental Governance. J. Sustain. Soc. Chang. 2013, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Tao, L.; Yang, B.; Bian, W. The Relationship between Public Participation in Environmental Governance and Corporations’ Environmental Violations. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Mol, A.P.J. Managing Major Chemical Accidents in China: Towards Effective Risk Information. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 187, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Mol, A.P.J.; Lu, Y. Trust and Credibility in Governing China’s Risk Society. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 7442–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Lu, Y.; Mol, A.P.J.; Beckers, T. Changes and Challenges: China’s Environmental Management in Transition. Environ. Dev. 2012, 3, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabai, A.; Rübbelke, D.; Maurer, L. ICT Applications in the Research into Environmental Sustainability: A User Preferences Approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, R.M.; Fariss, C.J.; Jones, J.J.; Kramer, A.D.I.; Marlow, C.; Settle, J.E.; Fowler, J.H. A 61-Million-Person Experiment in Social Influence and Political Mobilization. Nature 2012, 489, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Mol, A.P.J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y. Public Participation and Trust in Nuclear Power Development in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mol, A.P.; He, G. Transparency and Information Disclosure in China’s Environmental Governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 18, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ma, T.; Bian, Y.; Li, S.; Yi, Z. Improvement of Regional Environmental Quality: Government Environmental Governance and Public Participation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Public Participation and the Effect of Environmental Governance in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntaine, M.T.; Hunnicutt, P.; Komakech, P. The Challenges of Using Citizen Reporting to Improve Public Services: A Field Experiment on Solid Waste Services in Uganda. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2021, 31, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T.; Fedi, A.; Trippetti, S. Public Involvement: How to Encourage Citizen Participation. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 20, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, F.R.; Jones, B.D. Agendas and Instability in American Politics, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-226-03953-4. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.A.; Wagner, M.M.; Hogan, W.R.; Chapman, W.; Olszewski, R.T.; Dowling, J.; Barnas, G. Analysis of Web Access Logs for Surveillance of Influenza. In Proceedings of the MEDINFO 2004, San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–11 September 2004; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 1202–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg, J.; Mohebbi, M.H.; Patel, R.S.; Brammer, L.; Smolinski, M.S.; Brilliant, L. Detecting Influenza Epidemics Using Search Engine Query Data. Nature 2009, 457, 1012–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Varian, H. Predicting the Present with Google Trends. Econ. Rec. 2012, 88, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Brynjolfsson, E. The Future of Prediction: How Google Searches Foreshadow Housing Prices and Sales. In Economic Analysis of the Digital Economy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; pp. 89–118. [Google Scholar]

- Da, Z.; Engelberg, J.; Gao, P. In Search of Attention. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 1461–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, D.; Hasler, M. Investor Attention and Stock Market Volatility. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, J.; Kita, A.; Wang, Q. Investor Attention and FX Market Volatility. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2015, 38, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltomäki, J.; Graham, M.; Hasselgren, A. Investor Attention to Market Categories and Market Volatility: The Case of Emerging Markets. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2018, 44, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellino, M.; Stevanovic, D. The Demand and Supply of Information about Inflation; CIRANO Working Paper 2022s-27; CIRANO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Götz, T.B.; Knetsch, T.A. Google Data in Bridge Equation Models for German GDP. Int. J. Forecast. 2019, 35, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, B.; Liu, J.; Wegner, D.M. Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips. Science 2011, 333, 776–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Q.; Yang, J.; He, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Tang, F.; Ge, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ding, F. Understanding Public Attention towards the Beautiful Village Initiative in China and Exploring the Influencing Factors: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Baidu Index. Land 2021, 10, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, W. Spatial Characteristics of the Tourism Flows in China: A Study Based on the Baidu Index. IJGI 2021, 10, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Zhong, S.; Kang, Y. Citizen Participation and Urban Air Pollution Abatement: Evidence from Environmental Whistle-Blowing Platform Policy in Sichuan China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).