The Dark Side of Leadership: How Toxic Leadership Fuels Counterproductive Work Behaviors Through Organizational Cynicism and Injustice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Toxic Leadership (TL)

- Intentionally demoralizing, depreciating, marginalizing, being unapproachable, or inducing anguish.

- Engaging in unethical practices.

- Intentionally cultivating subordinates’ perceptions bolsters the leader’s authority while diminishing the subordinates’ performance abilities.

2.2. Organizational Cynicism (OC)

2.3. Organizational Injustice (OIJ)

2.4. Counterproductive Work Behaviors (CWBs)

2.5. Toxic Leadership and CWBs

2.6. Toxic Leadership and Organizational Cynicism

2.7. Toxic Leadership and Organizational Injustice

2.8. Organizational Cynicism and CWBs

2.9. Organizational Injustice and CWBs

2.10. The Mediating Role of OC in the Relationship Between Toxic Leadership and CWBs

2.11. The Mediating Role of OIJ in the Relationship Between Toxic Leadership and CWBs

2.12. Gender as Moderator Between Toxic Leadership and CWBs

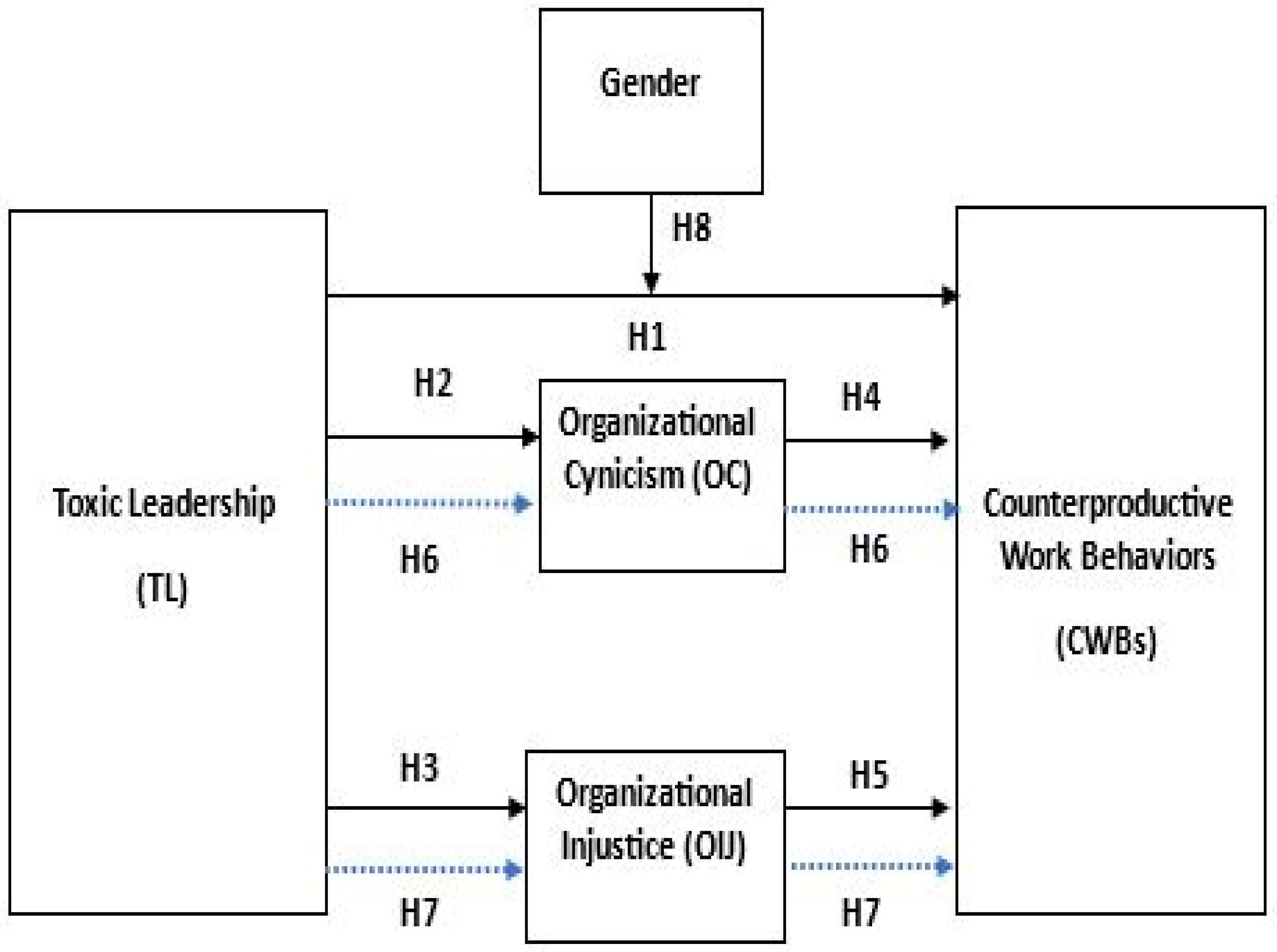

3. Conceptual Framework

4. Methodology

4.1. Procedures and a Sample Questionnaire

4.2. Measures and Operational Definitions

5. Results and Findings

5.1. Measurement Model Result

5.2. Structural Model

5.3. Gender Effect Analysis

6. Discussions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Contributions

6.3. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miao, C.; Humphrey, R.H.; Qian, S. The Cross-cultural Moderators of the Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Counterproductive Work Behavior. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2020, 31, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Mayer, D.M.; Hwang, E. More Is Less: Learning but Not Relaxing Buffers Deviance under Job Stressors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.J.; Robinson, S.L. Development of a Measure of Workplace Deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.; Detert, J.R.; Klebe Treviño, L.; Baker, V.L.; Mayer, D.M. Why Employees Do Bad Things: Moral Disengagement and Unethical Organizational Behavior. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. Are They among Us? A Conceptual Framework of the Relationship between the Dark Triad Personality and Counterproductive Work Behaviors (CWBs). Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.U.; De Clercq, D.; Haq, I.U. Suffering Doubly: How Victims of Coworker Incivility Risk Poor Performance Ratings by Responding with Organizational Deviance, Unless They Leverage Ingratiation Skills. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 161, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Gul, H.; Usman, M.; Islam, Z.U. Breach of Psychological Contract, Task Performance, Workplace Deviance: Evidence from Academia in Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Griep, Y.; Hansen, S.D.; Kraak, J.M. Perceived Identity Threat and Organizational Cynicism in the Recursive Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Counterproductive Work Behavior. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2023, 44, 351–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.A.O.; Zhang, J. Investigating the Effect of Psychological Contract Breach on Counterproductive Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organizational Cynicism. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2024, 43, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, H.; Choi, M. Differentiated Empowering Leadership and Interpersonal Counterproductive Work Behaviors: A Chained Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wu, Y.C.J.; Chen, X.C.; Lin, S.J. Why Do Employees Have Counterproductive Work Behavior? The Role of Founder’s Machiavellianism and the Corporate Culture in China. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, L.-Q.; Bednall, T.C. Why Abusive Supervision Impacts Employee OCB and CWB: A Meta-Analytic Review of Competing Mediating Mechanisms. J. Manage. 2019, 45, 2474–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griep, Y.; Vantilborgh, T.; Jones, S.K. The Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Counterproductive Work Behavior in Social Enterprises: Do Paid Employees and Volunteers Differ? Econ. Ind. Democr. 2020, 41, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Fraccaroli, F. The Job Demands–Resources Model and Counterproductive Work Behaviour: The Role of Job-Related Affect. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 467–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Francis, L.; Prosser, M.; Cameron, J.E. Counterproductive Work Behavior as Protest. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingzheng, W.; Xiaoling, S.; Xubo, F.; Youshan, L. Moral Identity as a Moderator of the Effects of Organizational Injustice on Counterproductive Work Behavior Among Chinese Public Servants. Public Pers. Manage. 2014, 43, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B.; Schilling, J. How Bad Are the Effects of Bad Leaders? A Meta-Analysis of Destructive Leadership and Its Outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.B.; Erickson, A.; Harvey, M. A Method for Measuring Destructive Leadership and Identifying Types of Destructive Leaders in Organizations. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasland, M.S.; Skogstad, A.; Notelaers, G.; Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. The Prevalence of Destructive Leadership Behaviour. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, K.; Thomson, B.; Rigotti, T. When Dark Leadership Exacerbates the Effects of Restructuring. J. Chang. Manag. 2018, 18, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Avey, J.B. Abusive Supervisors and Employees Who Cyberloaf: Examining the Roles of Psychological Capital and Contract Breach. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, I.; Maric, S.; Lončar, D. Defeating the Toxic Boss: The Nature of Toxic Leadership and the Role of Followers. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sengupta, S.; Dev, S. Toxicity in Leadership: Exploring Its Dimensions in the Indian Context. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 2017, 10, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Maheshwari, G.C. Consequence of Toxic Leadership on Employee Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. J. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2013, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, F.; Malik, M.I.; Hyder, S.; Perveen, A. Toxic Leadership and Project Success: Underpinning the Role of Cronyism. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koç, O.; Şahin, H.; Öngel, G.; Günsel, A.; Schermer, J.A. Examining Nurses’ Vengeful Behaviors: The Effects of Toxic Leadership and Psychological Well-Being. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljawarneh, N.M.S.; Atan, T. Linking Tolerance to Workplace Incivility, Service Innovative, Knowledge Hiding, and Job Search Behavior: The Mediating Role of Employee Cynicism. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2018, 11, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Peng, A.C.; Oh, I.-S.; Banks, G.C.; Lomeli, L.C. Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Organizational Cynicism: A Meta-Analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acaray, A.; Yildirim, S. The Impact of Personality Traits on Organizational Cynicism in the Education Sector. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 13, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Reio Jr, T.G. Examining the Role of Cynicism in the Relationships between Burnout and Employee Behavior. Rev. Psicol. del Trab. y las Organ. 2017, 33, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano Archimi, C.; Reynaud, E.; Yasin, H.M.; Bhatti, Z.A. How Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Affects Employee Cynicism: The Mediating Role of Organizational Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agina, M.; Khairy, H.; Abdel Fatah, M.; Manaa, Y.; Abdallah, R.; Aliane, N.; Afaneh, J.; Al-Romeedy, B. Distributive Injustice and Work Disengagement in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry: Mediating Roles of the Workplace Negative Gossip and Organizational Cynicism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Mahmood, Z. The Mediating-Moderating Model of Organizational Cynicism and Workplace Deviant Behavior: Evidence from Banking Sector in Pakistan. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2012, 12, 580–588. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C. How Supervisor Ostracism Affects Employee Turnover Intention: The Roles of Employee Cynicism and Job Embeddedness. J. Manag. Psychol. 2024, 39, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, P.; Dharwadkar, R.; Dean, J.W. Does Organizational Cynicism Matter? Employee and Supervisor Perspectives on Work Outcomes. In Proceedings of the Eastern Academy of Management Proceedings, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 13 May 1999; Volume 2, pp. 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Nemteanu, M.-S.; Dabija, D.-C. The Influence of Internal Marketing and Job Satisfaction on Task Performance and Counterproductive Work Behavior in an Emerging Market during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiwen, F.; Hahn, J. Job Insecurity in the COVID-19 Pandemic on Counterproductive Work Behavior of Millennials: A Time-Lagged Mediated and Moderated Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodson, R.; Creighton, S.; Jamison, C.S.; Rieble, S.; Welsh, S. Loyalty to Whom? Workplace Participation and the Development of Consent. Hum. Relations 1994, 47, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J.J. Exhausted, Mistreated, or Indifferent? Explaining Deviance from Emotional Display Rules at Work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S.; De Clercq, D.; Fatima, T. Organizational Injustice and Knowledge Hiding: The Roles of Organizational Dis-Identification and Benevolence. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Kundi, Y.M.; Sardar, S.; Shahid, S. Perceived Organizational Injustice and Counterproductive Work Behaviours: Mediated by Organizational Identification, Moderated by Discretionary Human Resource Practices. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 1545–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.K.; Atta, M.H.R.; El-Monshed, A.H.; Mohamed, A.I. The Effect of Toxic Leadership on Workplace Deviance: The Mediating Effect of Emotional Exhaustion, and the Moderating Effect of Organizational Cynicism. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronnie, L. The Challenge of Toxic Leadership in Realising Sustainable Development Goals: A Scoping Review. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, M.B.; Alasan, I.I. Impact of Toxic Leadership on Counterproductive Work Behavior with the Mediating Role of Psychological Contract Breach and Moderating Role of Proactive Personality. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Begum, K. Impact of Abusive Supervision on Intention to Leave: A Moderated Mediation Model of Organizational-Based Self Esteem and Emotional Exhaustion. Asian Bus. Manag. 2023, 22, 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholaif, M.M.N.H.K.; Ming, X. The Impact of Uncertainty-Fear against COVID-19 on Corporate Social Responsibility and Labor Practices Issues. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 5280–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chory, R.M.; Horan, S.M.; Raposo, P.J.C. Superior–Subordinate Aggressive Communication Among Catholic Priests and Sisters in the United States. Manag. Commun. Q. 2020, 34, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.A.; Qin, Y.S.; Men, L.R. The Dark Side of Leadership Communication: The Impact of Supervisor Verbal Aggressiveness on Workplace Culture, Employee–Organization Relationships and Counterproductive Work Behaviors. Corp. Commun. An Int. J. 2024, 29, 405–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Getting Even with One’s Supervisor and One’s Organization: Relationships among Types of Injustice, Desires for Revenge, and Counterproductive Work Behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.; Sun, L.; Li, C.; Leung, A.S.M. Abusive Supervision and Job-Oriented Constructive Deviance in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2249–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.-Y. Do Victims Really Help Their Abusive Supervisors? Reevaluating the Positive Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, J.; Asghar, A.; Asghar, M.Z. Effect of Despotic Leadership on Employee Turnover Intention: Mediating Toxic Workplace Environment and Cognitive Distraction in Academic Institutions. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-Based Approach to Leadership: Development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory of Leadership over 25 Years: Applying a Multi-Level Multi-Domain Perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.-Y.; Lam, L.W. Employee–Organization Exchange and Employee Creativity: A Motivational Perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C.; Perlow, R. The Role of Leader-Member Exchange Relations and Individual Differences on Counterproductive Work Behavior. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 127, 2050–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.; Mah, S.; Yun, S. Why Do Supervisors Abuse Certain Subordinates? Goal Orientation and Leader–Member Exchange as Antecedents. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2024, 31, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMazrouei, H.; Zacca, R. The Influence of Organizational Justice and Decision Latitude on Expatriate Organizational Commitment and Job Performance. Evid.-Based HRM 2021, 9, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.O.; Zhang, J.; Nour, H.M.; Hamdy, A.; Fouad, A.S. The Mediating Role of Open Innovation in the Relationship Between Organizational Justice and Organizational Pride in Egypt’s Healthcare Sector. In Digitalization and Management Innovation II; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.; Chung, S.W. Abusive Supervision, Psychological Capital, and Turnover Intention: Evidence from Factory Workers in China. Relat. Ind./Ind. Relat. 2019, 74, 377–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Fredricks-Lowman, I. Conflict in the Workplace: A 10-Year Review of Toxic Leadership in Higher Education. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 23, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandarker, A.; Rai, S. Toxic Leadership: Emotional Distress and Coping Strategy. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2019, 22, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O.; Alalyani, W.R.; Allil, K.; Al Shehab, A.; Al Rawas, S.; Hubais, A.; Hannawi, S. The Price of Silence, Isolation, and Cynicism: The Impact on Occupational Frustration. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sywelem, M.M.G.; Makhlouf, A.M.E. Common Challenges of Strategic Planning for Higher Education in Egypt. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 11, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fram Akplu, H. Private Participation in Higher Education in Sub- Saharan Africa: Ghana’s Experience. Int. High. Educ. 2016, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkhalek, F.; Langsten, R. Track and Sector in Egyptian Higher Education: Who Studies Where and Why? FIRE Forum Int. Res. Educ. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, E. Access to Higher Education in Egypt: Examining Trends by University Sector. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2013, 57, 527–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.K.; Quratulain, S.; Crawshaw, J.R. The Mediating Role of Discrete Emotions in the Relationship Between Injustice and Counterproductive Work Behaviors: A Study in Pakistan. J. Bus. Psychol. 2013, 28, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Hargis, M.B. What Motivates Deviant Behavior in the Workplace? An Examination of the Mechanisms by Which Procedural Injustice Affects Deviance. Motiv. Emot. 2017, 41, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, T. Toxic Leadership. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Whicker, M.L. Toxic Leaders: When Organizations Go Bad; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman-Blumen, J. The Allure of Toxic Leaders: Why We Follow Destructive Bosses and Corrupt Politicians--and How We Can Survive Them; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.A. Development and Validation of the Toxic Leadership Scale; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, I.; Anjam, M.; Zaman, U. Hell Is Empty, and All the Devils Are Here: Nexus between Toxic Leadership, Crisis Communication, and Resilience in COVID-19 Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, W.; Wijaya, N.H.S.; Kusumawati, H. The Relationship of Organisational Cynicism, Emotional Exhaustion, Creative Work Involvement and InRole Performance. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang 2020, 12, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Naseem, A.; Masood, S.A. Effect of Continuance Commitment and Organizational Cynicism on Employee Satisfaction in Engineering Organizations. Int. J. Innov. Manag. Technol. 2016, 7, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, T.; Ahmad, U.N.B.U.; Nawab, S.; Shah, S.F.H. Mediating Role of Organizational Cynicism in Relationship between Role Stressors and Turnover Intention: Evidence from Healthcare Sector of Pakistan. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Delken, M. Organizational Cynicism: A Study among Call Centers (Dissertation of. Master of Economics). Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, University of Maastrich, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koçoğlu Sazkaya, M. Cynicism as a Mediator of Relations between Job Stress and Work Alienation a Study from a Developing Country Turkey. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. Int. J. 2014, 6, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Simha, A.; Elloy, F.D.; Huang, H.-C. The Moderated Relationship between Job Burnout and Organizational Cynicism. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 482–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özler, D.E.; Atalay, C.G. A Research to Determine the Relationship between Organizational Cynicism and Burnout Levels of Employees in Health Sector. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 1, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A. Organizational Cynicism and Employee Turnover Intention: Evidence from Banking Sector in Pakistan. Pakistan J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2014, 8, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Charash, Y.; Spector, P.E. The Role of Justice in Organizations: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 278–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, G.S. What Should Be Done with Equity Theory? New Approaches to the Study of Fairness in Social Relationships. In Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the Dimensionality of Organizational Justice: A Construct Validation of a Measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RJ, B. Interactional Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness. Res. Negot. Organ. 1986, 1, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, M.L.; Seabright, M.A.; Schminke, M. Sabotage in the Workplace: The Role of Organizational Injustice. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 89, 947–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, M.R.; Majid, M.B.; Aslam, M.Z.; Rehman, A.; Rehman, S. Understanding the Linkage between Abusive Supervision and Counterproductive Work Behavior: The Role Played by Resilience and Psychological Contract Breach. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2323794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisha, R.; Channa, N.A.; Mirani, M.A.; Qureshi, N.A. Investigating the Influence of Perceived Organizational Justice on Counterproductive Work Behaviours: Mediating Role of Negative Emotions. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024, 19, 2264–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Qiu, T.Y.; Wu, H. Research on the Influence of the Sense of Overqualification on Employees’ Anti-Production Behavior-Mediating Effect of the Sense of Economic Deprivation and the Sense of Social Deprivation. J. Fin. Econ. Theory 2022, 6, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, I.B.U.; Putra, I.G.P. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Determinants. Int. J. Bus. 2022, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Yoon, J. Job Stress, Job Environment, Job Complexity and Counterproductive Working Behavior: Mediating Effects of Alcohol Drinking Behavior and Moderating Effects of Perceived Organizational Support. Korea Assoc. Bus. Educ. 2017, 32, 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Zhou, J. Corporate Hypocrisy and Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Organizational Identification and Perceived Importance of CSR. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nübold, A.; Bader, J.; Bozin, N.; Depala, R.; Eidast, H.; Johannessen, E.A.; Prinz, G. Developing a Taxonomy of Dark Triad Triggers at Work—A Grounded Theory Study Protocol. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, J.M.; Sanchez, J.; Imberi, J.E.; Grande, L.R. The Norm of Reciprocity as an Internalized Social Norm: Returning Favors Even When No One Finds Out. Soc. Influ. 2009, 4, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aselage, J.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived Organizational Support and Psychological Contracts: A Theoretical Integration. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J.; Carr, J.C.; Breaux, D.M.; Geider, S.; Hu, C.; Hua, W. Abusive Supervision, Intentions to Quit, and Employees’ Workplace Deviance: A Power/Dependence Analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 109, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brender-Ilan, Y.; Sheaffer, Z. How Do Self-Efficacy, Narcissism and Autonomy Mediate the Link between Destructive Leadership and Counterproductive Work Behaviour. Asia Pacific Manag. Rev. 2019, 24, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.A. An Examination of Toxic Leadership, Job Outcomes, and the Impact of Military Deployment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, A.; Hogan, R.; Kaiser, R.B. The Toxic Triangle: Destructive Leaders, Susceptible Followers, and Conducive Environments. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, M.J. The Relationship Between Toxic Leadership, Organizational Citizenship, and Turnover Behaviors Among San Diego Nonprofit Paid Staff; University of San Diego: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, R.A. Leadership in the US Army: A Qualitative Exploratory Case Study of the Effects Toxic Leadership Has on the Morale and Welfare of Soldiers; Capella University: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ince, F. Toxic Leadership as a Predictor of Perceived Organizational Cynicism. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2018, 9, 24343–24349. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.; Qian, J.; Wang, B.; Yang, M.; Zhai, A. Are You Hiding from Your Boss? Leader’s Destructive Personality and Employee Silence. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Janssen, O.; Shi, K. Leader Trust and Employee Voice: The Moderating Role of Empowering Leader Behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Loi, R.; Lam, L.W. The Bad Boss Takes It All: How Abusive Supervision and Leader–Member Exchange Interact to Influence Employee Silence. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, J. How Abusive Supervisors Influence Employees’ Voice and Silence: The Effects of Interactional Justice and Organizational Attribution. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 155, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyhanoglu, M.; Akin, O. Impact of Toxic Leadership on the Intention to Leave: A Research on Permanent and Contracted Hospital Employees. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2022, 38, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, J.M.; Evans, W.R.; Davis, W.D. A Test of Coworkers’ Influence on Organizational Cynicism, Badmouthing, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 2273–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Şaylıkay, M. The Effect of Organisational Cynicism on Alienation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.R.; Goodman, J.M.; Davis, W.D. The Impact of Perceived Corporate Citizenship on Organizational Cynicism, OCB, and Employee Deviance. Hum. Perform. 2011, 24, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Chong, S.; Chen, J.; Johnson, R.E.; Ren, X. The Interplay of Low Identification, Psychological Detachment, and Cynicism for Predicting Counterproductive Work Behaviour. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 59–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, N.; Khan, S.; Rauf, A. Deviant Behavior and Organizational Justice: Mediator Test for Organizational Cynicism—The Case of Pakistan. Asian J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 2, 333–347. [Google Scholar]

- EREN, G.; DEMİR, R. The Effect of Perceived Pay Equity on Counterproductive Work Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Organizational Cynicism. Ege Akad. Bakis (Ege Acad. Rev.) 2023, 23, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.; Jiatong, W.; Shahzad, F.; Syed, N. The Influence of Despotic Leadership on Counterproductive Work Behavior among Police Personnel: Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Organizational Cynicism. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2021, 36, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, S.; Wirawan, H.; Salam, R.; Daswati, D.; Niswaty, R. The Effect of Toxic Leadership on Turnover Intention and Counterproductive Work Behaviour in Indonesia Public Organisations. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2022, 35, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, N.I. Norma Ivette Rosado The Relationship Between Abusive Management and Counterproductive Employee Behavior in the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Buyukyilmaz, O.; Kara, C. Linking Leaders’ Toxic Leadership Behaviors to Employee Attitudes and Behaviors. Serbian J. Manag. 2024, 19, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Achieving Relational Authenticity in Leadership: Does Gender Matter? Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S.; Gentry, J.; Chun, S.; Commuri, S.; Fischer, E.; Jun, S.; Mcginnis, L.; Palan, K.; Strahilevitz, M. Putrevu/Exploring the Origins and Information Processing Differences Between Men and Women Exploring the Origins and Information Processing Differences Between Men and Women: Implications for Advertisers. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2001, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Maheswaran, D. Exploring Differences in Males’ and Females’ Processing Strategies. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reder, L.M. Strategy Selection in Question Answering. Cogn. Psychol. 1987, 19, 90–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgalil, A.M. The Role of Ethical Leadership on the Relationship between Organizational Cynicism and Alienation at Work: An Empirical Study. Arab J. Adm. 2022, 42, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Loughlin, C.; Barling, J.; Nault, A. Self-reported Counterproductive Behaviors and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Separate but Related Constructs. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2002, 10, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajani, M.A.Z.; Saad Mohamad, M. Perceived Organisational Injustice and Counterproductive Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Work Alienation Evidence from the Egyptian Public Sector. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne Barbara, M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2016, 5, 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Denham-Vaughan, S.; Chidiac, M.-A. A Relational Perspective on Public Sector Leadership and Management. Int. J. Leadersh. Public Serv. 2014, 10, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Rousseau, D.M. Violating the Psychological Contract: Not the Exception but the Norm. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J. Ten Propositions about Public Leadership. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2018, 14, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C.; Babiak, P. Corporate Psychopathy and Abusive Supervision: Their Influence on Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intentions. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 91, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Srivastava, A.; Jena, L.K. Abusive Supervision and Intention to Quit: Exploring Multi-Mediational Approaches. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1269–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Lee, S.; Yun, S. The Trickle-Down Effect of Abusive Supervision: The Moderating Effects of Supervisors’ Task Performance and Employee Promotion Focus. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, O.C.; Boncoeur, O.D.; Chen, H.; Ford, D.L. Supervisor Abuse Effects on Subordinate Turnover Intentions and Subsequent Interpersonal Aggression: The Role of Power-Distance Orientation and Perceived Human Resource Support Climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 164, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, K.D. The Effect of Toxic Leadership on Deviant Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Employee Cynicism. Texas J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2023, 18, 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- Park, G.Y.; Moon, G.; Kim, S.Y. A Structural Relationship between Workaholism, Job Burnout, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Counterproductive Behavor in Office Workers. Korean J. Resour. Dev. 2015, 18, 81–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeh, L.N.; Etodike, C.E.; Chukwura, E.N. Abusive Supervision and Organizational Cynicism as Predictors of Cyber-Loafing among Federal Civil Service Employees in Anambra State, Nigeria. Eur. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Stud. 2018, 1, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs, J.M.; Do, J.J. The Impact of Perceived Toxic Leadership on Cynicism in Officer Candidates. Armed Forces Soc. 2019, 45, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayan, A.R.M.; Aly, N.A.M.; Abdelgalel, A.M. Organizational Cynicism and Counterproductive Work Behaviors: An Empirical Study. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 10, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Charash, Y.; Mueller, J.S. Does Perceived Unfairness Exacerbate or Mitigate Interpersonal Counterproductive Work Behaviors Related to Envy? J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.J.; Andrews, M.C.; Kacmar, K.M. The Moderating Effects of Justice on the Relationship Between Organizational Politics and Workplace Attitudes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2007, 22, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiningsih, I.; Td, S. Strengthening Innovative Leadership in the Turbulent Environment. Leadersh. New Insights 2022, 2022, 139–176. [Google Scholar]

- Musaigwa, M.; Kalitanyi, V. Effective Leadership in the Digital Era: An Exploration of Change Management. Technol. Audit Prod. Reserv. 2024, 1, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagur-Femenías, L.; Buil-Fabrega, M.; Aznar, J.P. Teaching Digital Natives to Acquire Competences for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Barbosa Franco, J.; Franco Junior, A.; Battistelle, R.A.G.; Bezerra, B.S. Dynamic Capabilities: Unveiling Key Resources for Environmental Sustainability and Economic Sustainability, and Corporate Social Responsibility towards Sustainable Development Goals. Resources 2024, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biltagy, M. Sustainability in Higher Education in Egypt. In The Wiley Handbook of Sustainability in Higher Education Learning and Teaching; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Farghaly Abdelaliem, S.M.; Abou Zeid, M.A.G. The Relationship between Toxic Leadership and Organizational Performance: The Mediating Effect of Nurses’ Silence. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwantes, C.T.; Bond, M.H. Organizational Justice and Autonomy as Moderators of the Relationship between Social and Organizational Cynicism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019, 151, 109391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, S.; Raja, U.; Syed, F.; Baig, M.U.A. When and Why Organizational Cynicism Leads to CWBs. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivette, A.; Nägel, C.; Stan, A. The Use of Experimental Vignettes in Studying Police Procedural Justice: A Systematic Review. J. Exp. Criminol. 2024, 20, 151–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Peng, A.C.; Savani, K.; Dimotakis, N. Guilty and Helpful: An Emotion-Based Reparatory Model of Voluntary Work Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Sun, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C. Moderated Mediation Model of Relationship between Perceived Organizational Justice and Counterproductive Work Behavior. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 7, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lyu, B.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Fan, J. Supervisor Developmental Feedback and Employee Performance: The Roles of Feedback-Seeking and Political Skill. J. Psychol. Africa 2019, 29, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Zhong, X.; Gao, D.D. The Effect of Job Alienation on Turnover Intention: The Role of Organizational Political Perception and Personal Tradition. Psychol. Res 2020, 13, 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Guo, X. Antecedents of Responsible Leadership: Proactive and Passive Responsible Leadership Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Dimensions | Measurement Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable: TL | Abusive supervision | [73] |

| Authoritarian leadership | ||

| Narcissism | ||

| Self-promotion | ||

| Unpredictability | ||

| Mediator: OC | [124] | |

| Mediator: OIJ | Procedural justice | [126] |

| Distributive justice | ||

| Interpersonal justice | ||

| Informational justice | ||

| Dependent Variable: CWBs | [125] |

| Goodness of Fit Measures | Name of Index | Model Result | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square | χ2 | 2437.829 | accepted |

| Degrees of Freedom | DF | 1268 | accepted |

| Chi-Square/Degrees of Freedom | χ2/DF | 1.923 | accepted |

| Comparative Fit’ Index | CFI | 0.934 | accepted |

| Tucker Lewis Index | TLI | 0.928 | accepted |

| Root Mean’ Square Error of Approximation | RMSEA | 0.044 | accepted |

| Variable | Construct and Item | Standardized Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Abusive supervision | Holds subordinates responsible for things outside their job descriptions | 0.758 |

| Is not considerate about subordinates’ commitments outside of work | 0.829 | |

| Speaks poorly about subordinates to other people in the workplace | 0.771 | |

| Reminds subordinates of their past mistakes and failures | 0.795 | |

| Tells subordinates they are incompetent | 0.802 | |

| Authoritarian leadership | Controls how subordinates complete their tasks | 0.508 |

| Invades the privacy of subordinates | 0.737 | |

| Does not permit subordinates to approach goals in new ways | 0.859 | |

| Is inflexible when it comes to organizational policies, even in specialcircumstances | 0.891 | |

| Narcissism | Has a sense of personal entitlement | 0.713 |

| Assumes that he/she is destined to enter the highest ranks of the organization | 0.763 | |

| Thinks that he/she is more capable than others | 0.795 | |

| Believes that he/she is an extraordinary person | 0.747 | |

| Thrives on compliments and personal accolades | 0.796 | |

| Self-Promotion | Drastically changes his/her demeanor when his/her supervisor is present | 0.853 |

| Denies responsibility for mistakes made in his/her unit | 0.909 | |

| Will only offer assistance to people who can help him/her get ahead | 0.907 | |

| Accepts credit for successes that do not belong to him/her | 0.758 | |

| Acts only in the best interest of his/her next promotion | 0.748 | |

| Unpredictability | Allows his/her current mood to define the climate of the workplace | 0.827 |

| Expresses anger at subordinates for unknown reasons | 0.887 | |

| Varies in his/her degree of approachability | 0.838 | |

| Causes subordinates to try to “read” his/her mood | 0.881 | |

| Affects the emotions of subordinates when impassioned | 0.757 | |

| Organizational cynicism | The organization’s policies, goals, and practices do not match with what is really happening on the ground | 0.866 |

| The organization expects workers to do something, but does not reward them | 0.727 | |

| I feel uncomfortable when I think about my organization | 0.594 | |

| I complain to my external friends about how things are managed within the organization | 0.821 | |

| I share common views with a specific meaning about the organization with my colleagues at work | 0.799 | |

| I criticize the organization’s practices and policies in front of others | 0.542 | |

| Procedural justice | Have you been able to express your views and feelings during those procedures? | 0.831 |

| Have those procedures been applied consistently? | 0.891 | |

| Have those procedures been free of bias? | 0.857 | |

| Have those procedures been based on accurate information? | 0.871 | |

| Have you been able to appeal the (outcome) arrived at by those procedures? | 0.814 | |

| Have you been able to express your views and feelings during those procedures? | 0.748 | |

| Distributive justice | Does your (outcome) reflect the effort you have put into your work? | 0.721 |

| Is your (outcome) appropriate for the work you have completed? | 0.774 | |

| Does your (outcome) reflect what you have contributed to the organization? | 0.725 | |

| Is your (outcome) justified, given your performance? | 0.739 | |

| Interpersonal justice | Has (he/she) treated you in a polite manner? | 0.735 |

| Has (he/she) treated you with dignity? | 0.805 | |

| Has (he/she) treated you with respect? | 0.733 | |

| Has (he/she) refrained from making improper remarks or comments? | 0.755 | |

| Informational justice | Has (he/she) explained the procedures thoroughly? | 0.844 |

| Were (his/her) explanations regarding the procedures reasonable? | 0.840 | |

| Has (he/she) communicated details in a timely manner? | 0.814 | |

| Has (he/she) seemed to tailor (his/her) communications to individuals’ specific needs? | 0.554 | |

| Counterproductive work Behaviors (CWBs) | Started negative rumors about your company | 0.796 |

| Covered up your mistakes | 0.906 | |

| Competed with your coworkers in an unproductive way | 0.873 | |

| Stayed out of sight to avoid work | 0.878 | |

| Took company equipment or merchandise | 0.867 | |

| Blamed your coworkers for your mistakes | 0.786 | |

| Intentionally worked slowly | 0.765 |

| Variables | Composite Reliability CR | Average Variances Extracted AVE | Maximum Reliability MaxR (H) | Abusive Supervision | Narcissism | Authoritarian Leadership | Self-Promotion | Unpredictability | Procedural Justice | Distributive Justice | Interpersonal Justice | Informational Justice | CWBs | Organizational Cynicism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abusive Supervision | 0.878 | 0.591 | 0.884 | 0.769 | ||||||||||

| Narcissism | 0.875 | 0.583 | 0.877 | 0.040 | 0.764 | |||||||||

| Authoritarian Leadership | 0.827 | 0.561 | 0.890 | 0.583 *** | 0.087 | 0.749 | ||||||||

| Self-Promotion | 0.921 | 0.702 | 0.936 | 0.572 *** | 0.032 | 0.777 *** | 0.838 | |||||||

| Unpredictability | 0.918 | 0.737 | 0.921 | 0.018 | 0.099 † | 0.023 | 0.063 | 0.859 | ||||||

| Procedural justice | 0.920 | 0.698 | 0.925 | 0.364 *** | 0.084 | 0.600 *** | 0.598 *** | 0.023 | 0.836 | |||||

| Distributive justice | 0.829 | 0.548 | 0.830 | 0.041 | −0.131 * | −0.011 | −0.037 | −0.018 | −0.038 | 0.740 | ||||

| Interpersonal justice | 0.843 | 0.574 | 0.846 | 0.108 * | 0.733 *** | 0.044 | 0.068 | 0.087 † | 0.074 | −0.025 | 0.758 | |||

| Informational justice | 0.852 | 0.597 | 0.879 | 0.312 *** | −0.001 | 0.189 *** | 0.282 *** | 0.058 | 0.350 *** | −0.030 | −0.043 | 0.772 | ||

| CWBs | 0.944 | 0.706 | 0.950 | 0.471 *** | 0.071 | 0.793 *** | 0.649 *** | 0.023 | 0.699 *** | 0.036 | 0.110 * | 0.292 *** | 0.840 | |

| Organizational cynicism | 0.829 | 0.591 | 0.895 | 0.625 *** | 0.134 * | 0.733 *** | 0.763 *** | −0.009 | 0.665 *** | 0.005 | 0.139 ** | 0.359 *** | 0.762 *** | 0.769 |

| Goodness of Fit Measures | Name of Index | Model Result | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square | χ2 | 2824.260 | accepted |

| Degrees of Freedom | DF | 1310 | accepted |

| Chi-Square/Degrees of Freedom | χ2/DF | 2.156 | accepted |

| Comparative Fit’ Index | CFI | 0.914 | accepted |

| Tucker Lewis Index | TLI | 0.910 | accepted |

| Root Mean’ Square Error of Approximation | RMSEA | 0.049 | accepted |

| Hypothesized Path | Estimate | Critical Ratio (C.R) | Significance Level (p-Value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Cynicism | ← | Toxic Leadership | 0.973 | 18.090 | *** |

| Organizational Injustice | ← | Toxic Leadership | 0.781 | 13.190 | *** |

| (CWBs) | ← | Toxic Leadership | 0.361 | 2.838 | 0.005 |

| (CWBs) | ← | Organizational Cynicism | 0.832 | 14.951 | *** |

| (CWBs) | ← | Organizational Injustice | 0.430 | 3.186 | 0.001 |

| Mediating Path | Significance Level (p-Value) |

|---|---|

| Effect Toxic Leadership on CWBs Through Organizational Cynicism | 0.004 |

| Effect Toxic Leadership on CWBs Through Organizational Injustice | 0.001 |

| Path Name | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (β) Value | Significance (p-Value) | Beta (β) Value | Significance (p-Value) | |

| CWBs ← Toxic Leadership | 0.381 | *** | 0.342 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, M.A.O.; Zhang, J.; Fouad, A.S.; Mousa, K.; Nour, H.M. The Dark Side of Leadership: How Toxic Leadership Fuels Counterproductive Work Behaviors Through Organizational Cynicism and Injustice. Sustainability 2025, 17, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010105

Ahmed MAO, Zhang J, Fouad AS, Mousa K, Nour HM. The Dark Side of Leadership: How Toxic Leadership Fuels Counterproductive Work Behaviors Through Organizational Cynicism and Injustice. Sustainability. 2025; 17(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Mohamed Abdelkhalek Omar, Junguang Zhang, Ahmed Sabry Fouad, Kawther Mousa, and Hamdy Mohamed Nour. 2025. "The Dark Side of Leadership: How Toxic Leadership Fuels Counterproductive Work Behaviors Through Organizational Cynicism and Injustice" Sustainability 17, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010105

APA StyleAhmed, M. A. O., Zhang, J., Fouad, A. S., Mousa, K., & Nour, H. M. (2025). The Dark Side of Leadership: How Toxic Leadership Fuels Counterproductive Work Behaviors Through Organizational Cynicism and Injustice. Sustainability, 17(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010105