Abstract

Ineffective management increasingly threatens cultural heritage conservation, resulting in the mismanagement of tangible heritage assets and reducing the efficacy of conservation efforts. Although much of the literature examines the relationship between heritage management, tourism, and economic development, a notable gap exists in comprehending the interrelated elements that undermine the efficacy of conservation initiatives. This paper argues that administrative, financial, legal, and stakeholder-related factors are intricately connected in causing ineffective heritage management. These factors must be examined in interrelation to improve cultural heritage conservation efforts. A systematic review of the academic and grey literature on conserving tangible cultural assets is carried out to contribute to this goal. This literature review identifies 29 factors that contribute to the inefficacy of cultural heritage management plans. These factors are classified into several categories, including administrative institutions, stakeholders, financial resources, natural and human risks, laws and legislation, and political issues. This study presents a theoretical framework that connects governments, stakeholders, legislation, and administrative performance as crucial components in the success of heritage management. It highlights the need for transparent procedures for the successful implementation of heritage management strategies. The findings contribute to assessing cultural heritage management plans and propose directions for further research, including addressing local heritage concerns and methods to enhance the management performance. By identifying key factors that impede effective management, this paper contributes to the broader sustainability challenges of preserving cultural heritage while promoting social and economic stability. Enhanced heritage management practices can significantly contribute to the development of inclusive and sustainable communities.

1. Introduction

Heritage plays a crucial role in shaping a community’s identity by providing a sense of belonging, preserving traditions, and enhancing pride in cultural heritage. It reflects a community’s history, values, and collective memory. Heritage sites, represent a community’s past cultural heritage, including religious buildings, monuments, or traditional practices. They often serve as a gathering place for social interactions and community events, reinforcing a community’s unique identity and fostering a sense of pride and connection among its members [1].

Safeguarding cultural heritage is closely linked to both human rights, equality in the community, and the need for governments to guarantee its protection, indicating a universal principle that transcends specific contexts. Understanding cultural heritage as a dynamic and evolving practice rather than a fixed entity highlights its profound impact on community identity and the broader societal fabric [2].

In this context, cultural heritage management emerges as a vital mechanism in protecting the diversity of human history. When implemented effectively, it ensures cultural heritage’s integrity and accessibility to all [3]. Heritage institutions, governments, and local communities collaborate in management practices to protect the value and distinctive elements of heritage for the benefit of various stakeholders [4,5,6]. Managing heritage involves safeguarding it in the present while ensuring its transmission to future generations and recognising its critical role in shaping and defining a society’s identity [7,8,9].

Heritage management is undergoing a significant change. The focus has shifted from merely managing the integrity of tangible heritage assets to emphasising the cultural importance that they convey, as well as the values and qualities, both tangible and intangible, that make these assets distinctive and justify their classification as local, national, or global cultural heritage [10]. This shift stems from an expanded definition of heritage and the increased appreciation of cultural diversity in approaches to heritage preservation globally [11]. This change has increased the diversity of the sectors and specialisations engaged in cultural heritage. It is reflected in the plurality of management approaches and the involvement of multiple stakeholders, including governments, international and local organisations, heritage professionals, and local communities [12,13,14].

The expansion of heritage management considerations has made it a complex and variable process, dependent on a given heritage site’s social, political, and economic context [15,16]. Political and economic changes, and variations in the social conditions and interests of surrounding stakeholders, create significant differences that hinder the unification of heritage management systems [17]. These dynamic influences also prevent the establishment of an ideal, fixed administrative system as the factors shaping the management process evolve over time [15,18,19,20].

The importance of effectively managing cultural heritage has led to a heightened global emphasis on ensuring adequate preservation through robust heritage management practices [16,21]. Recognising this, the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has made the availability of a comprehensive and integrated management plan a fundamental requirement for inclusion in the World Heritage List [22,23].

The need for effective management plans for heritage in environments other than their original setting has emerged due to various factors, including rapid global change, capital globalisation, and escalating conflicts [19,21]. Numerous threats to cultural heritage, such as disasters exacerbated by climate change, including floods, rising sea levels, and desertification, demand robust administrative plans that include proactive monitoring, preventive measures, and strategies to improve the resilience of decision-making and implementation frameworks. These plans should also focus on mitigation efforts, maintenance, and restoration operations in the event of a disaster [24]. Furthermore, proactive plans to prevent or minimise disasters, rather than reactive plans to recover from disasters, are needed to avoid significant damage [24,25]. Human-related threats, such as urban sprawl, economic development, vandalism, and theft, further endanger cultural heritage, especially in the context of limited awareness of its value or inadequate state policies to ensure protection [4,6]. In the face of such threats, improper cultural heritage management itself can significantly threaten heritage protection. Without comprehensive and informed administration, managing heritage preservation effectively or utilise heritage to benefit people and their development is impossible. Recognising the critical role of effective management, UNESCO has identified several heritage management issues as reasons for inclusion in the list of endangered heritage, including (1) modifying the legal status of the property and reducing its protection, (2) a lack of conservation policies, (3) threats from regional planning projects, and (4) threats to city planning [22].

Emphasising the importance of management in preserving heritage sites, UNESCO has included best practices for heritage site preservation, highlighting the role of comprehensive and effective management in making sites accessible to the world and presenting them in their best light [26]. An example is the sacred city of Caral Sub in the Republic of Peru. The Peruvian state facilitated the site’s inclusion on the World Heritage List in 2009 despite its prior lack of recognition locally or internationally. This was achieved by developing an ongoing programme to preserve the architectural originality of the site while respecting its environment and considering its geographical conditions. Moreover, this plan was integrated into a master plan aimed at promoting sustainable regional population development. Residents of the area were trained and employed to monitor and preserve the area. The continuity of these measures was ensured by incorporating them into various national legislations [26]. Another example of administrative success in preserving and highlighting heritage sites is the Kazan Kremlin, a historical and architectural site in Russia. The site is managed by the local government within a national administrative framework that encompasses all heritage sites in the country. State policies have established a long-term management approach to preserve the site based on the principle of integrated heritage and its inclusion in the community’s daily life. The authorities also created an effective legal system, working with stakeholders and involving them in the management processes [26].

Further demonstrating the importance of effective management, some sites have been removed from the endangered list due to proper management that has preserved the sites and protected their global value. These include the city of Timbuktu in Mali, which was removed from the endangered list after the responsible departments adopted administrative plans, renovated buildings, and improved water infrastructure. Similarly, in Butrint, Albania, administrative measures and effective plans were implemented to manage the site and protect it from looting. As a result, the World Heritage Committee decided to remove these two sites from the danger list and restore their positions on the World Heritage List [27].

Given the profound implications of cultural heritage management, understanding the reasons behind its ineffectiveness is crucial to ensuring its preservation. Cultural heritage is not only a repository of a shared collective memory but is also intrinsically linked to promoting sustainable development, environmental conservation, and economic growth, as well as fostering dialogue and understanding in an interconnected global society. Therefore, effective cultural heritage management is not merely a commitment to our history but also an investment in our future [28,29,30,31].

This research seeks to identify the reasons behind the ineffectiveness of cultural heritage conservation management by analysing the literature to identify the factors that hinder effective management and examine their interrelationships. This paper does not review the entirety of the literature on the various fields of heritage management. Instead, it focuses on the management of tangible cultural heritage conservation, aiming to identify the critical factors that drive the failure or success of heritage conservation in general.

This research adopts a systematic literature review methodology to classify and examine the elements contributing to ineffective management based on the gaps identified. This methodology ensures that the research emphasises the most relevant aspects, enabling decision-makers to focus on these areas and address deficiencies in the management process. This study aims to enhance the capacity of administrative institutions, thereby promoting robust heritage management that benefits both local and national interests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

This study examines the literature concerning the management of tangible cultural heritage and the effectiveness of administrative plans to conserve and protect it. Reliable academic databases were used, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus. These databases were selected to cover the comprehensive, peer-reviewed, relevant literature. Combining multiple academic databases for a literature review enhances the comprehensiveness and depth of the search results. In addition, it greatly increases the coverage of cited references, as no single database covers all relevant literature. All selected databases offer strengths [32,33].

Google Scholar covers a wide range of scholarly communication avenues, including various government and academic websites, making it a valuable tool for interdisciplinary studies. Web of Science is known for its accurate indexing and broad historical coverage across the humanities, social sciences, and environmental studies, which are essential in understanding cultural heritage management. Scopus offers robust citation tracking and an extensive index of journals, including international and open access, ensuring that the selected literature is relevant and widely recognised in the field [32,33,34].

The search keywords used in the three databases included “ineffectiveness, failure”, “cultural heritage”, and “management plans”. The advanced search option was employed, specifying the period from 2000 to 2023 to narrow the research scope and focus on recent developments in cultural heritage management. This period reflects significant changes in conservation practices, technologies, and international frameworks. The results were limited to articles and book chapters due to the branching nature of cultural heritage. The search yielded 5020 articles. Criteria were established to refine and select the most relevant materials.

- (1)

- Context: The focus was on tangible cultural heritage, heritage sites, and historical buildings, excluding intangible heritage, natural heritage, and protected areas.

- (2)

- Scope: Emphasis was placed on heritage management for conservation, excluding aspects such as investment, tourism, or development.

- (3)

- Conservation: Natural threats like climate change and earthquakes were excluded from the conservation management processes studied.

The branching nature of the search guided the selection of keywords and their categorisation to ensure accuracy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected search keywords.

The keywords were divided into three categories. The first described the management situation or plan, using terms such as “ineffective management” and synonyms. The second category comprised words describing the heritage chosen for the study, such as “cultural heritage” and “tangible heritage”. The third referred to heritage management or conservation plans, with studies indicating that “cultural heritage conservation” is often used interchangeably with “heritage management” [1].

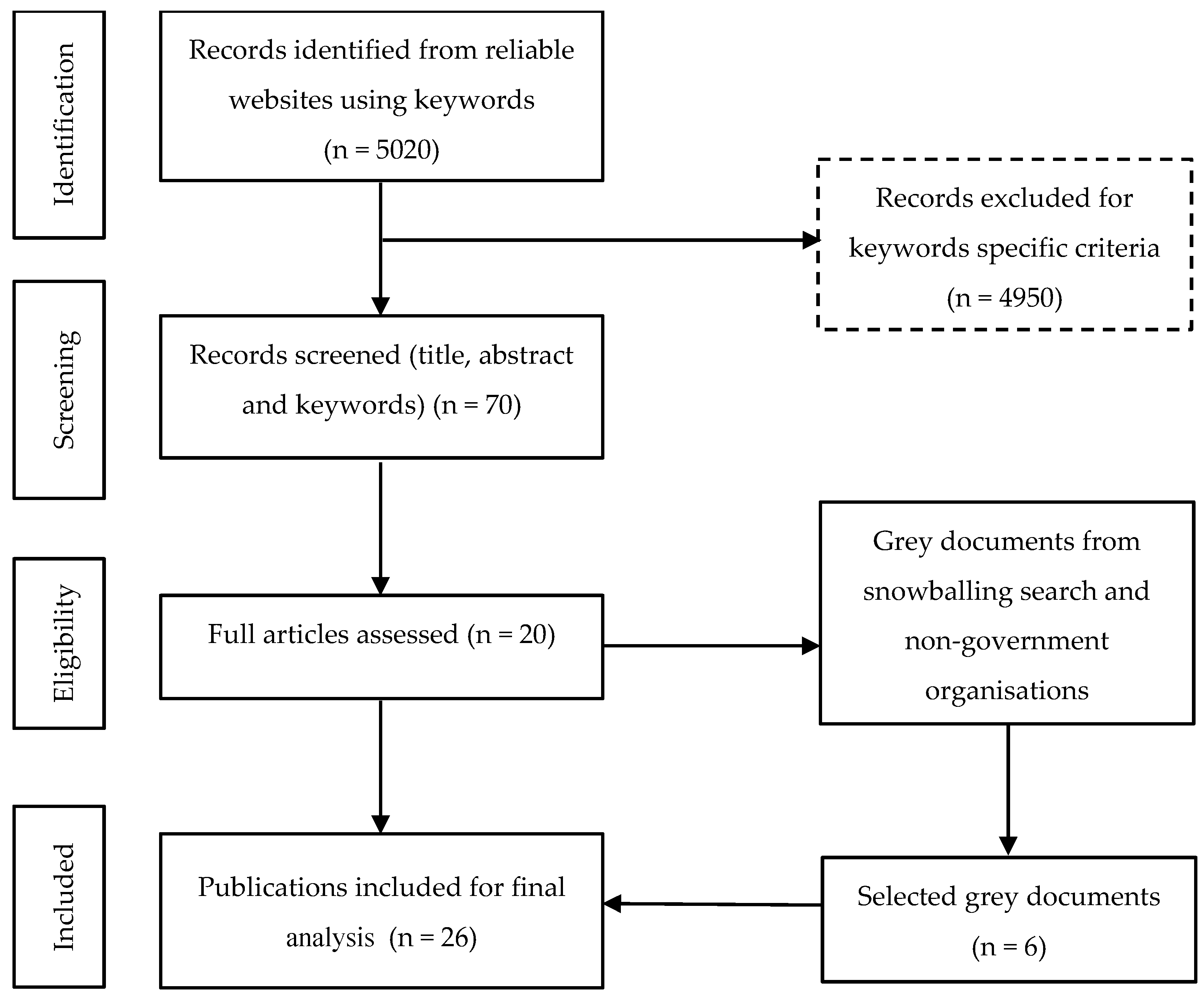

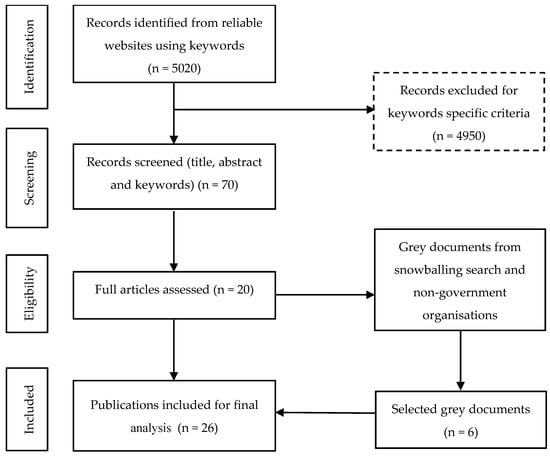

Figure 1 illustrates the systematic filtering of the results in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines adopted during the search process. The first step involved screening the titles, abstracts, and keywords to identify articles containing the relevant terms. In the second step, the full texts of these articles were thoroughly reviewed to evaluate their relevance to the study’s main theme. These steps led to the selection of 20 articles deemed suitable for a comprehensive analysis aimed at understanding the effectiveness of material cultural heritage management.

Figure 1.

The process of publication selection.

In addition to academic sources, it was essential to include grey literature, such as reports and principles from governmental and non-governmental organisations. For this research, documents were chosen from international organisations such as UNESCO and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), recognised for their authority in protecting cultural heritage. These organisations provide valuable perspectives through policies and guidelines supporting local and international conservation approaches. The inclusion of grey literature helps to bridge the gap between academic research and practical application by highlighting international best practices. This literature was collected by analysing the references in the selected studies using a snowballing method [35] and searching heritage organisations’ websites, such as UNESCO and ICOMOS. This process identified six documents for inclusion in the study [36].

A total of twenty articles and six grey documents were selected to ensure a balanced and comprehensive review. The twenty publications were selected for their relevance and alignment with the study’s focus on tangible cultural heritage management, offering a wide yet manageable academic sample. The six grey documents in Appendix A provide practical insights and policy guidelines, representing international standards in heritage management. This balance enabled the study to integrate academic analysis with practical, policy-driven approaches to cultural heritage conservation.

2.2. Research Methods

A literature review is a research method that assesses the current level of knowledge available on a topic, from which future research can proceed [37]. It answers a specific research question by collecting the available evidence, discussing it, evaluating it, and building a foundation of knowledge around it [38]. This study aimed to determine what existing research has indicated about the factors leading to the ineffectiveness of heritage site management plans in conservation.

The use of this research method requires precision and specific criteria for the selection of the literature to build bias-free results from the selected studies [36]. By specifying clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researcher ensures a transparent and accurate selection process aligned with the study’s objectives. Adherence to the PRISMA protocol, as detailed in the Supplementary Materials File, ensures comprehensive and replicable systematic reporting [37].

2.3. Data Analysis

This study adopted a systematic analysis to achieve its objectives, aiming to provide a comprehensive and structured approach to interpreting and analysing the data precisely. Systematic analysis ensures a rigorous and transparent methodology, allowing for the exploration of phenomena through a step-by-step process. This approach allows the researcher to understand the studied phenomena in depth, facilitating a thorough and natural exploration of their underlying components and relationships [39].

In particular, the systematic analysis involved a detailed review of the literature to identify factors contributing to the failure of cultural heritage conservation management plans. This approach began with selecting relevant academic and professional sources based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring the comprehensive coverage of key studies. Once the data sources were completed, the researchers employed thematic analysis as a qualitative tool to interpret the collected data. The thematic analysis enabled the identification of the main topics, allowing for the organisation of the data into the main factors behind the complex dynamics of heritage management challenges. This layered approach helps build a conceptual framework [39], enabling a deeper understanding of the relationships between the identified factors.

The study’s data analysis process aimed not only to classify these factors but also to examine their elements and the interconnections among them. Specifically, the focus was on delving deeper into understanding how each identified factor contributes to or exacerbates the failure of management plans. By systematically breaking down and analysing these components, the research highlights the mechanisms through which heritage management strategies succeed or falter. This comprehensive analysis helps to build a conceptual framework that outlines the critical elements of effective heritage management, illustrating their interrelationships and prioritisation.

Ultimately, this framework seeks to provide a valuable tool for the evaluation of heritage management systems by answering the following research questions:

- -

- What does ineffective heritage management indicate?

- -

- What crucial elements must be available to build a successful management plan?

- -

- How do these elements relate to and affect each other?

By addressing these questions, this study contributes to the theoretical and practical understanding of heritage management, offering insights that support the development of more effective management strategies.

3. Results

3.1. Validation of Heritage Management and Conservation Literature Gaps

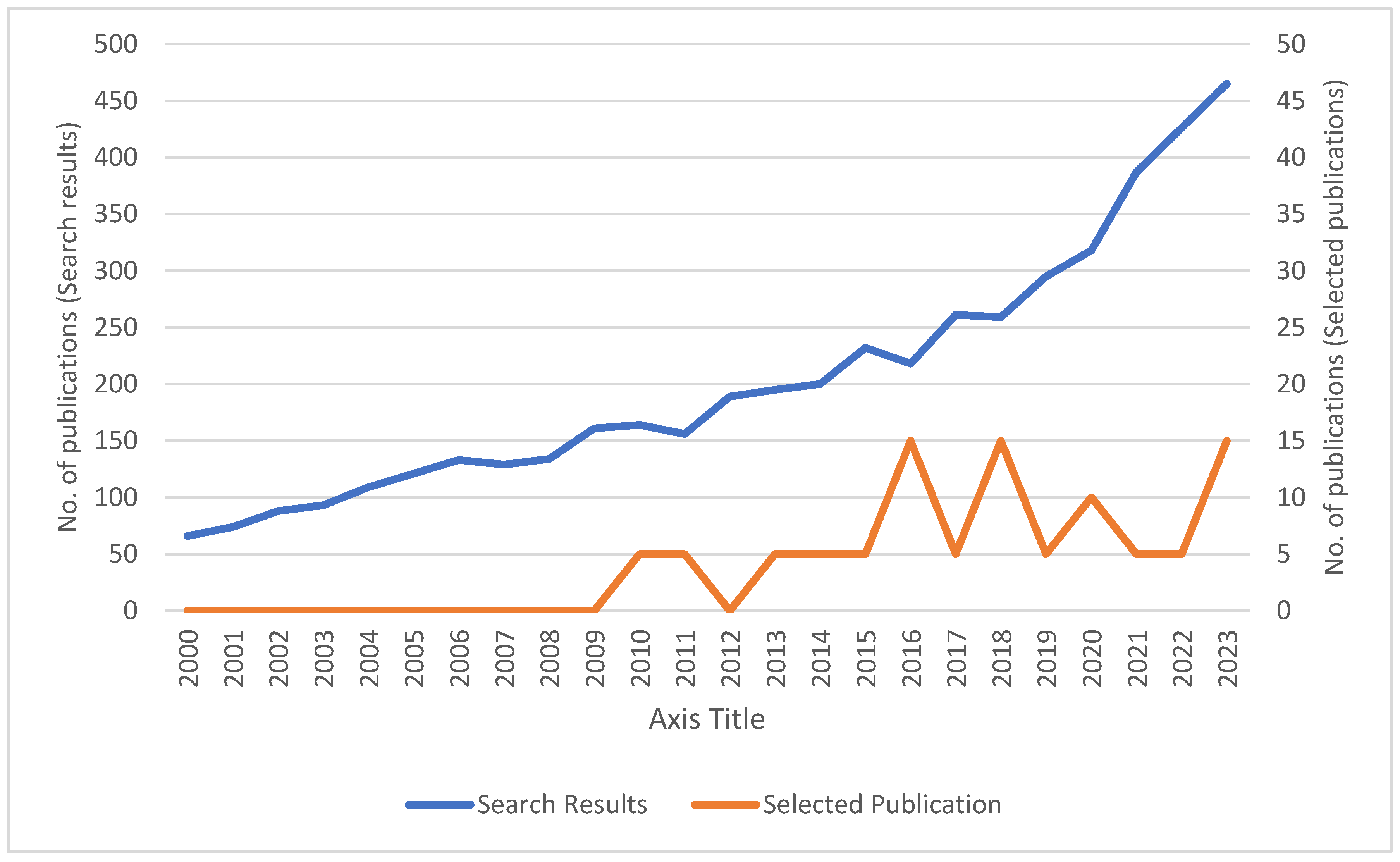

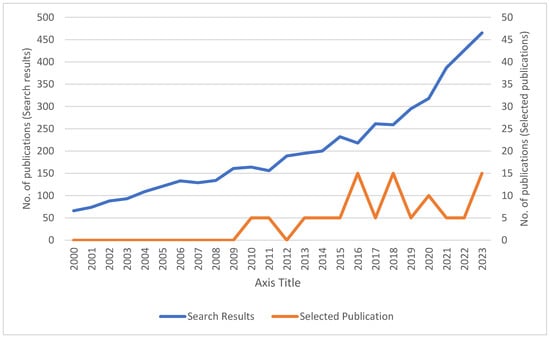

The search results utilising the keywords in Table 1 from the three academic websites, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science, covering the period from 2000 to 2023, indicated a significant volume of publications. These results also showed a growing interest in cultural heritage management over time. As shown in Figure 2, the number of articles has increased over the years. However, further examination of these articles’ titles, keywords, and abstracts during the first selection step indicated that the efficacy of cultural heritage management and conservation strategies was not given sufficient attention. A more comprehensive review conducted in the second selection phase resulted in the list presented in Table 2. The representation of this list is displayed in Figure 2, which indicates that research in this field began around 2010. Although the search results have gradually increased, the secondary axis, which emphasises the subset of selected articles, indicates that the number of targeted studies in this field has been irregular, with notable peaks in specific years. The gap in the literature this review aims to address is underscored by the direct comparison between the more specific focus of the selected studies and the broader research trends made possible by this dual-axis representation.

Figure 2.

Yearly representation of search results and selected papers for keywords from 2000 to 2023.

Table 2.

The chosen literature with its keywords.

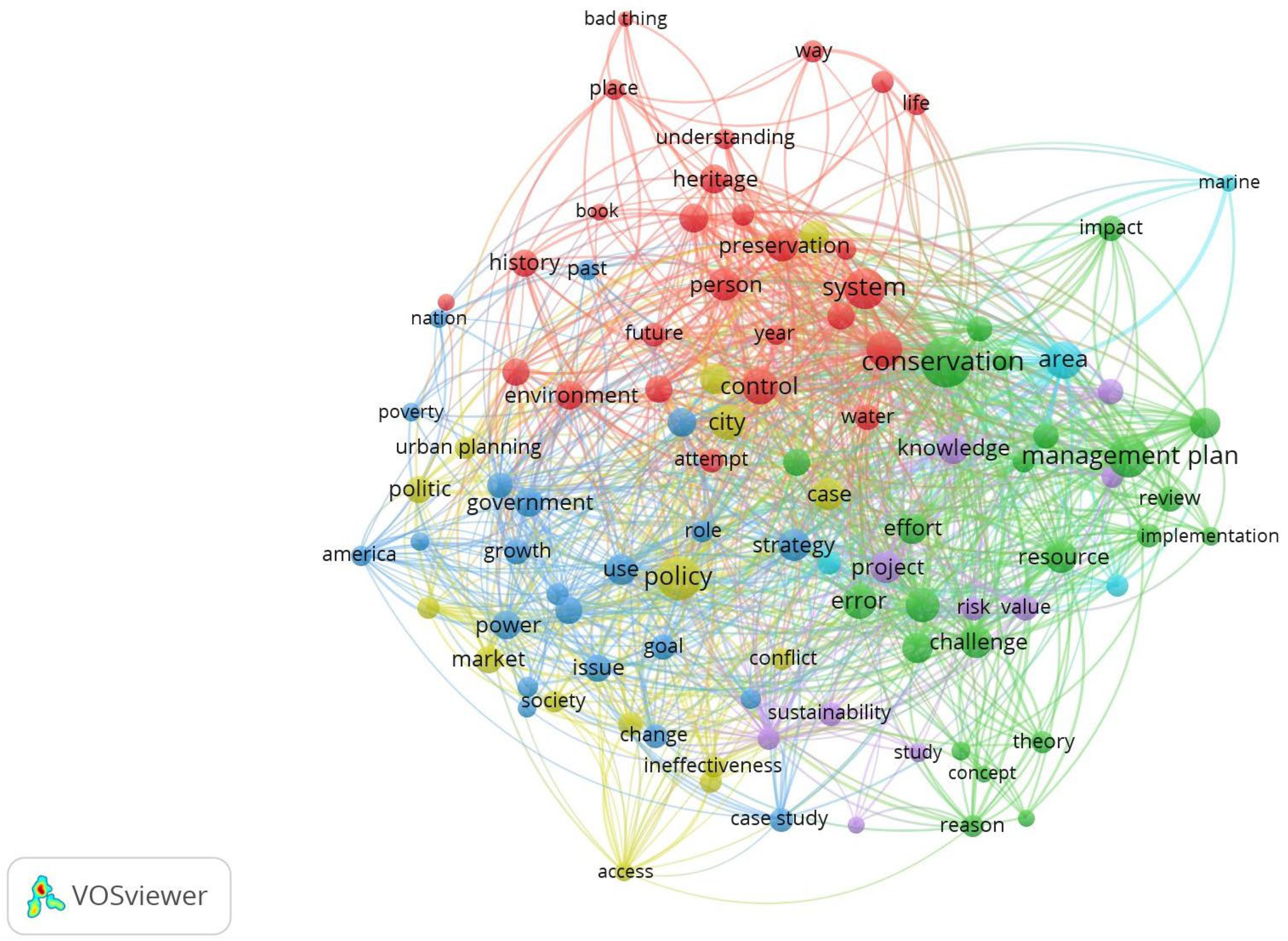

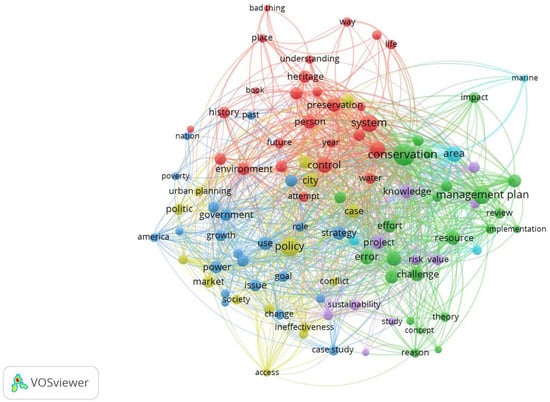

A verification process was conducted to confirm that the literature emphasised other aspects of heritage management, such as tourism management and sustainability, over the effectiveness of management and conservation plans. This process was conducted to clarify the weak appearance of the keywords in the literature despite the vast number of results that the used database showed. The validation process included selecting a sample of the first 1000 references provided by Google Scholar for the search keywords using Harzing’s Publish or Perish tool. Google Scholar was chosen due to its provision of a greater variety of results compared to other websites, along with the inclusion of the majority of the results from Web of Science and Scopus within its findings. The results were entered into the VOSviewer software (Version 1.6.20) to create a network visualisation of the dominant keywords in the literature.

VOSviewer is widely recognised for its advanced capabilities in bibliometric analysis and visualisation. For example, it can construct maps of journals based on citation data or map keywords based on their co-occurrence. It also provides flexible visualisation options to emphasise different aspects of the generated maps [40].

For the network map shown in Figure 3, a cluster resolution of 1.0 was applied, and a minimum of three items was required to form a cluster. The nodes (circle) represent the keywords of the search results, and their size indicates the number of times that these words are repeated, from most common to least frequently appearing in the literature. The result indicates that the selected keywords did not appear prominently on the map, but only a limited number appeared alongside many other terms. This confirms the diversity of the keywords in articles on cultural heritage management. It also shows the weak presence of keywords related to tangible heritage management and conservation plans. The diversity of the keywords also indicates the fragmentation of the focus of the articles on various aspects of heritage management. This explains the limited literature selected compared to the vast literature produced by the three selected search engines.

Figure 3.

A network representation of the terms used in a sample of Google Scholar publications.

3.2. Heritage Management Effectiveness

Management effectiveness refers to the ability of a manager or institution to achieve specific goals while making good use of the available resources [41,42]. It is a multifaceted concept that is measured in different ways, including goal achievement, resource optimisation, and stakeholder satisfaction [41,42]. These dimensions make the assessment of management effectiveness variable depending on the chosen criteria and can lead to differing interpretations of success.

In a heritage context, management effectiveness can be defined as the quality and efficiency of plans and measures to protect heritage sites or historical properties [43]. The concept also refers to evaluating management systems and practices at heritage sites to ensure that they achieve their aim of adequate protection and conservation [44]. There are many variables that influence the definition of effectiveness, such as aspects that negatively affect the quality of plans, the measures taken, and management practices, which can differ significantly depending on the perspective from which they are measured.

Nevertheless, it is accepted that a site can be managed to guarantee the goal of preservation and sustainable safeguarding [13,16,45,46,47]. Sometimes, conservation is required to reach the highest possible standards, consistent with international standards for inclusion in the World Heritage List [31,48,49,50], or to maintain its historical significance in terms of social identity as understood by local standards [15,51]. Thus, the measures of effectiveness will differ based on the intended outcomes. Table 3 presents several themes used by scholars to measure and define management efficiency.

Table 3.

Definitions of cultural heritage effectiveness according to several themes.

It must be borne in mind that the stability of conservation goals or the purpose of exploiting sites does not equate to stability in terms of the efficiency of such measures. This is because the efficiency of measures will change over time due to changes in the variables pertaining to a site and the available resources, in addition to the needs of stakeholders [31,43]. This is common in heritage issues, as the sites themselves are often fragile and the requirements for their preservation increase over time [20,52]. The interests of those around it are variable, and their requirements and vision for heritage are also variable [53].

Another variable that affects the definition or conceptualisation of effectiveness is the clarity and transparency of conservation procedures and management plans. The UNESCO Guidelines indicate that effective management is a cycle of sequential and interconnected actions to protect and preserve heritage in various forms [52]. Studies have indicated that the failure to achieve efficacy is due to a lack of clarity and understanding of these procedures by the parties involved in management [43,54,55]. A study indicates that ambiguity in management and decision-making between officials at the World Heritage Site of the Port, Forts, and Monuments of Cartagena is a major cause of management challenges that threaten to place the site on the danger list [56].

The clarity of management plans establishes a comprehensive understanding of the required results and supports the smooth implementation of operations. It helps a plan to remain relevant over time, facilitating the easy monitoring of steps and ongoing adjustments [43,53].

Therefore, the effectiveness of cultural heritage management can be described as a clear interpretation of a dynamic and diverse process. This process includes setting goals, agreed upon by all concerned parties, to implement an integrated plan dedicated to preserving cultural heritage for the benefit of current and future generations. From time to time, however, the appropriate measures of effectiveness vary from one perspective to another and from one administration to another, depending on what heritage means and the circumstances surrounding it. Thus, the formation, implementation, and maintenance of effective cultural heritage management strategies can be inherently ongoing, requiring the continual re-evaluation of goals, procedures, and outcomes in terms of both their aims and execution. This process should be consistent with international preservation and protection approaches, including those established by UNESCO and ICOMOS, to guarantee consistency, accountability, and adherence to global best practices in heritage management.

However, effective heritage management exceeds technical measures by fostering community comprehension of the significance of their cultural heritage through education. Incorporating heritage education into local curricula and awareness initiatives cultivates identity and responsibility in youth. Integrating practical conservation with education enhances the efficacy of preservation efforts [57].

3.3. Reasons for Ineffective Heritage Management

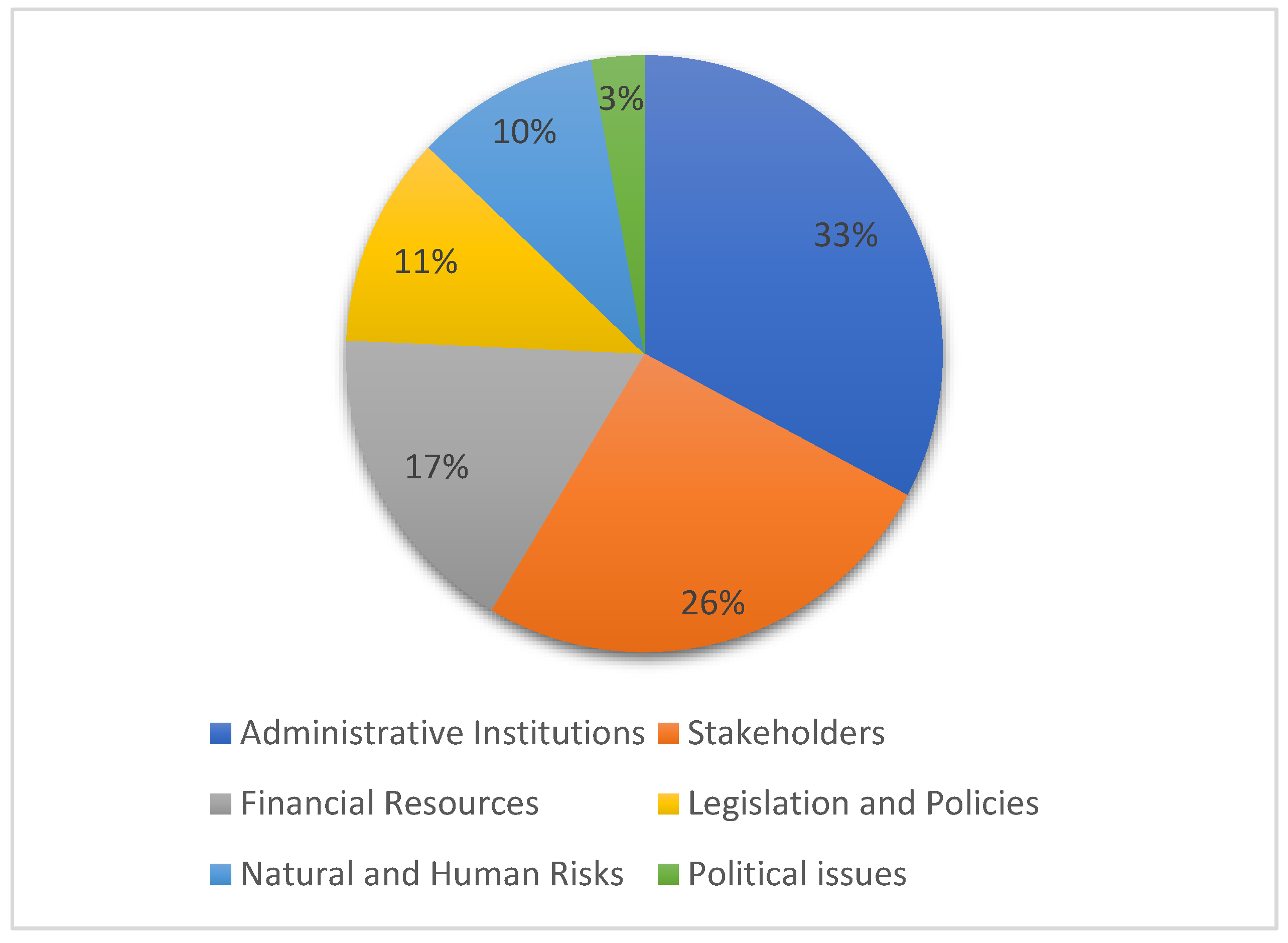

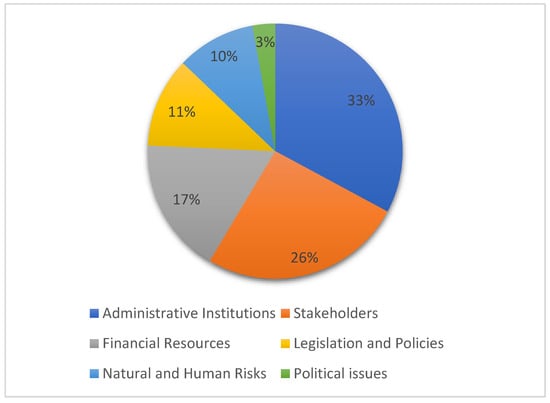

Based on the articles collected and reviewed in this research, 29 factors affecting heritage management’s effectiveness were identified (Table 4). These factors have also been classified into six main categories: administrative institutions, local society and stakeholders, financial resources, legislation and policies, natural and human hazards, and political issues. Figure 4 shows the percentage of references to each category in the selected articles.

Table 4.

The factors influencing the effectiveness of heritage management as identified in the selected studies.

Figure 4.

Percentages of the six categories that include the factors referred to in the selected articles.

The administrative institutions category emerged as dominant, with themes in this category constituting 33% of the total mentions. Stakeholders follow closely behind at 26%, indicating their significant influence on the subject matter. However, this dominance may indicate an overemphasis on governance and stakeholder dynamics in the literature, potentially overshadowing other crucial drivers. Financial resources, legislation and policies, and natural and human risks occupy intermediate positions, each accounting for 10–17% of the discussion. This representation suggests that these factors are recognised as important; however, this focus may not accurately reflect their actual importance, or their roles may be underappreciated in the literature. Political issues are the least frequently mentioned category, suggesting a relatively minor role in the articles’ context. This may indicate that this factor is less important in the specific contexts studied or that, due to limitations in the study, it has not been sufficiently explored. Given the significant influence of political stability and policy-making on heritage management, this representation raises questions about possible gaps in the literature.

3.3.1. Administrative Institutions

Administrative institutions and their performance represented the highest percentage of the attributed causes of heritage management failure in the studied literature. The studies pointed to various aspects related to the administrative institutions concerned with heritage in several countries, starting with the inadequacy of the administrative structure. Managing a heritage site usually involves several governmental institutions and sometimes non-governmental organisations. A lack of necessary communication and cooperation between these institutions leads to confusion and inefficiency [16,43,48]. Each institution’s work, according to its own set of regulations, also leads to conflicting management methods and responsibilities [48,60]. For example, the lack of a coherent strategy and governance structure for the various institutions and organisations involved in the management of the historic centre of Naples has been a major obstacle to the effective management of this site. In the 1990s, Italy eliminated its central Ministry of Culture, redistributing the responsibilities for cultural heritage across several government departments, resulting in a unified direction and coordination deficiency. This has caused sites like the centre of Naples to face significant challenges, including administrative inefficiency [61,66]. In addition, the studied literature points out that the inadequacy and diversity of competencies in the administrative structure in various fields related to heritage management could lead to a gap in inadequate heritage protection and management plans [13,45,48].

While administrative institutions may have sufficient staffing, they may not be professionally and technically qualified, hindering effective management [1,43,46,47]. For instance, research on heritage sites in Egypt indicated that, although the administrative organisations have adequate staffing, there is a shortage of professionals, particularly site planners. This issue is apparent in local sites like Abu Rawash, where many local staff members lack archaeological expertise and site management knowledge [16,67]. Compounding this issue are resource constraints, including insufficient financial support for staff training and the adoption of innovative technologies to enhance the management efficiency. Such limitations make skill and technology shortages a shared challenge across administrative institutions and financial resources. For example, post-conflict Syria experienced a severe decline in skilled workers at its heritage sites due to death and displacement. Furthermore, the lack of resources in a country recovering from war limits the support for preservation and documentation efforts with high-tech tools and trained personnel. Despite international support, heritage institutions still face difficulties in effectively documenting and protecting cultural heritage [68].

Deficiencies in administrative plans may be due to limited administrative goals, manifested in weak and non-comprehensive assessments of a site and its needs [49,54,64]. Plans may be based on outdated information due to a lack of monitoring, comprehensive building condition assessment, and insufficiently detailed site inventories [58]. Weak skills among administrative staff sometimes result in the production of complex plans that are difficult to interpret [45,47,51]. This leads to the incorrect implementation of a plan or an inability to implement it completely [31,47,59]. Notably, some studies attribute the deficiency in administrative plans to the diversity of cultural heritage, the specificity of each site, and the inability to generalise plans, which complicates the problem [50,54]. For example, in Turkey, relying on comprehensive planning frameworks to manage the rich fabric of World Heritage Sites often undermines their effective conservation due to the unique characteristics of each site. Hierapolis, a Roman city, requires a balance between preserving its geological wonders and ancient ruins and managing its high tourism traffic. In contrast, Hattusha requires strategies to protect its fragile archaeological remains, such as mud-brick structures and rock carvings, which are vulnerable to environmental factors. Similar cases include Pergamum and Aphrodisias, among others. These examples illustrate how the unique characteristics of each site require tailored management strategies, which a general framework may fail to accommodate effectively [69].

Evaluation processes for the performance of administrative institutions have also been cited as a reason for their failure. Evaluation processes, whether of the organisation’s structure or performance, allow appropriate adjustments and changes to be made that ensure the correction of defects and improvements in outputs. Without such measures, problems may not be addressed in a timely manner [54]. Usually, evaluation processes are internal and carried out by the institution itself. However, external stakeholders such as governments or social communities may also participate by contributing to the development of evaluation criteria by providing local knowledge and cultural insights, offering feedback on performance outcomes and providing supervision [70].

The performance of administrative institutions may be hampered by external factors related to government policies, including changing heritage institutions or the transfer of responsibilities to other institutions, which may be due to the political and administrative marginalisation of the site [60]. A government can also hinder the work of institutions by not including heritage management plans in their general plans. Hence, the implementation of management plans, particularly conservation and preservation work, may conflict with the implementation of other state plans, such as development and urban expansion plans [47,52].

3.3.2. Stakeholders

Stakeholders are a wide range of individuals and groups with a particular interest in the outcomes of heritage projects [4]. They may be affected by heritage management plans and can also influence the goals and results of these plans [12]. Stakeholders include, for example, government authorities, administrative institutions, sponsors, tourists, the local community, and individuals.

These groups significantly impacted the effectiveness of heritage management and were collectively ranked as the second most influential category in the articles selected for this review. In most of these studies, reference was made to the local community’s significant role in the success or failure of conservation plans. The term “local community” refers to the people who live in and around heritage sites [4]. They can be described as people who must participate in activities to manage their local environment, represented by heritage sites, to protect and develop them [4].

Stakeholder participation is one of the primary management principles mentioned in the UNESCO guidelines. Failure to ensure comprehensive stakeholder participation leads to plans that do not fully address their needs, thus failing to reach a consensus with them and causing problems to arise [52]. Petra in Jordan has faced conflicts among stakeholders like local communities, conservationists, and tourism operators. Conflicts over land use and tourism benefits have hindered unified decision-making and threatened conservation. However, an integrated management plan mitigated these conflicts and resolved long-standing issues [47].

The marginalisation of stakeholders and the lack of interest in including them in planning processes is often due to a lack of awareness among administrators and decision-makers about the critical role of stakeholders, including the local community, in enhancing management processes [13,31,46,58]. Alternatively, it may be due to a conflict of interest between two or more parties [59]. This gap leads to disputes because stakeholders do not meet their entire needs. This can even lead to negligence and sabotage that threatens a site’s integrity [52,64]. It also limits the exploitation of stakeholders’ extensive knowledge of the heritage site [46]. According to Bevan, the destruction of the Buddhas in Afghanistan is a tragic illustration of the consequences of the government’s exclusion of stakeholders, failure to consider their perspectives, and failure to involve them, which led to irreparable heritage site loss and damage. In contrast, the site’s local and global value was preserved when stakeholders were involved in the planning and administration of the site following the destruction [71].

Furthermore, a lack of awareness of stakeholder needs often affects the management efficiency in other ways. For instance, a lack of community awareness about the importance and value of heritage sites is the main reason for the emergence of negative and uncooperative stakeholders, which leads to the undermining of administrative conservation efforts [1,16,48,50,55,64].

3.3.3. Financial Resources

Adequate funding and financial resources are crucial to preserving and enhancing heritage sites. Such efforts, however, often require extensive financial resources [45,46,49]. The Memphis site and its necropolis in Egypt is an example of a World Heritage Site suffering from a lack of funding, which has led to numerous challenges that threaten its conservation and global significance. The lack of adequate financial resources has hindered the implementation of comprehensive management strategies and the enhancement of the quality of life of communities. Although the government is aware of these issues, efforts to resolve these bottlenecks remain limited due to financial constraints [72], the complexity of conservation work for heritage sites and the need for contingency funds for the emergence of unexpected events, such as sudden collapses of fragile buildings [20]. Furthermore, financial resources also cover funds allocated for maintenance, preservation, and restoration work, in addition to developing the infrastructure of heritage sites, either to avoid damage or to develop tourism to ensure the flow of money in the region [48,52,58].

The problem of a lack of funds arises for various reasons, including governments’ allocation of insufficient financial support to manage and preserve heritage sites. This may be because heritage sites are marginal and of no importance to the government or because the government is interested in satisfying the most urgent needs of its people, such as food security and combating disease [46,65].

Placing heritage administrative departments in different state institutions often results in insufficient funding and support. This leads to an imbalance in setting priorities and allocating the necessary resources for effective heritage management [51]. For example, the management of Egyptian cultural heritage, including its famous heritage sites such as the Giza Pyramids, was under the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development for years. The focus of this organisation on urban expansion and infrastructure development conflicted with the priorities of heritage conservation, which led to the allocation of inadequate funding for conservation and maintenance [73].

Some governments rely on international funding and aid from organisations such as UNESCO, which may not be sufficient or sustainable in the long term [16,48]. The absence of previous financial budgets and improper financial planning due to a lack of experience may lead to financial uncertainty regarding the financial needs of site management. This leads to great difficulty in ensuring the regular flow of financial resources within a well-thought-out plan and, thus, the potential cessation of business activities or the failure of plans [50,63].

3.3.4. Legislation and Policies

A state’s legislation and laws constitute the basis for building heritage management [74]. Each country has its own legislative framework and laws designed to protect its heritage. These laws are responsible for defining the roles and powers of heritage institutions, which is a crucial step in coordinating roles between institutions to manage heritage effectively. In addition, administrative plans for heritage protection are based on legislation’s provisions, which provide them with the necessary legal framework and protection for their implementation. Laws not only empower institutions but also act as a shield against dangers and threats to heritage sites.

However, some laws have deficiencies or loopholes that do not cover specific requirements or allow threats to heritage to arise due to changes in the sites or the surrounding environment, sometimes due to a lack of continuous updating [16,52,55,61]. A notable deficiency in Jordanian law regarding heritage protection is its failure to safeguard sites established after 1750. This oversight has permitted a prominent heritage structure at the Umm al-Qais site to be repurposed as a tourist police office, lacking the requisite protections despite its distinctive Ottoman characteristics and deteriorating condition [75].

Some laws contain ambiguous legal terms, which pose a challenge to a comprehensive understanding of their interpretation and intent. This opacity may create an opportunity to exploit loopholes that violate the law’s overall aims in favour of specific individuals and cause damage to heritage sites, such as unauthorised demolitions [61,65].

Challenges related to laws may also arise due to defects or deficiencies in the implementation of laws by the relevant authorities or a lack of integration with other state policies, which hinders their ability to act in the best way for heritage. Decision-makers in some governments can hinder the timely implementation of laws with lengthy approval processes. Such delays render legal guarantees inactive until approvals are issued, which threatens cultural assets and their integrity [1,49,54].

In dealing with the complexities of heritage management, it becomes necessary for decision-makers and lawmakers to deal with these challenges to achieve legal accuracy and consistency in dealing with and including heritage within the broader framework of state policy. Such efforts are a prerequisite in closing legal gaps and ensuring that heritage legislation is sufficient to preserve it.

3.3.5. Natural and Human Risks

Threats from natural and human-caused hazards profoundly impact the effectiveness of heritage conservation plans. Natural hazards, such as rain, floods, fires, earthquakes, and sand encroachment, can present uncontrolled forces that can destroy heritage sites completely. While causing immediate damage, these risks have unexpected consequences. This necessitates additional and often unplanned efforts in conservation processes. In many cases, the difficulty in predicting such disasters further complicates the implementation of conservation initiatives, posing challenges that require adaptability and flexibility [1,16,46]. When conservation plans lack disaster preparedness, they are ill-equipped to confront sudden disasters, and the absence of emergency strategies undermines the integrity of the original conservation plans and can cause them to fail [52].

Threats resulting from human activities, such as urbanisation, development pressures, vandalism, theft, and conflict, pose severe threats to heritage. These can lead to the deterioration of sites and the buffer zones surrounding them, or even their complete or partial destruction, thus endangering their cultural and historical value [64]. These human-induced threats often create administrative complexities, exacerbated by conflicting priorities at the government level. In some cases, economic development considerations may take precedence over the need for long-term heritage preservation [58].

Effectively managing these threats requires careful planning to balance development requirements and cultural heritage preservation [65]. Adopting a multi-dimensional management perspective is necessary to overcome the complex challenges posed by natural and human hazards, ensure the longevity and resilience of heritage sites, and maintain the integrity of their management.

3.3.6. Political Issues

Although state political issues are the last factor attributed to cultural heritage management failure in the studied literature, their influence on heritage management has significant consequences for its effectiveness. Political fluctuations within countries and governments can potentially lead to economic downturns, thus reducing the resources allocated to heritage conservation [47]. Furthermore, shifts in political leadership or the outbreak of armed conflicts can destabilise governmental authority, creating an environment in which political support for heritage conservation operations may be absent [47].

These political dynamics play a critical role in determining priorities for conservation management work [47]. They also play a crucial role in identifying political stakeholders at different levels of governance. This awareness is integral to the conservation life cycle, extending to the planning and implementation phases [47,53]. Recognising and navigating the complexities of the political landscape is crucial in developing effective heritage conservation strategies, ensuring that efforts are consistent with broader political goals, and securing the support needed to achieve sustainable success [53]. As such, a careful understanding of the interplay between political issues and heritage management is essential in developing conservation initiatives that are flexible and adaptable in the face of evolving political contexts.

4. Discussion

Heritage management is a multifaceted endeavour, and its success or failure depends on the complex relationship between the various factors that influence it. The results of the present literature review identify factors that indicate the causes of management processes’ failure. These factors can be categorised as a combination of flaws in government structures, the planning of its administrative processes, the legal frameworks it follows, and the budgets allocated by the state, in addition to dealing with stakeholders, especially the local community. In addition, it refers to natural hazards and human risks, as well as fluctuations in state policies and their support for heritage. Through an in-depth study to find a connection between these elements, it was found that many of them are related to and affect each other but that there is a common thread between them. Specifically, the main driver is the government, which most studies do not directly refer to.

Governments are the primary reason for the success or failure of heritage preservation management. The government is a comprehensive entity that brings together many of the previously mentioned elements. This begins with legal legislation, whose principal author is the government [74,76,77]. Ultimately, a government formulates heritage laws and all other state laws. It also has the right to expand, revise, and otherwise make amendments according to its vision of the state’s running. The government also links laws through executive regulations [76,77]. In addition, the government determines the nature and composition of the administrative institutions that preside over heritage. It defines the powers of these institutions, which in turn determines the interconnections between the work of different institutions in heritage management [74].

The government’s interest in cultural heritage and its investment in it as a source of income for the state are the primary driver of the financial resources it devotes to its preservation. Most countries lacking heritage management funding are developing countries that rely on external funding to manage their heritage [51]. There may also be countries that do not pay attention to heritage for several reasons, including the availability of other sources of income, or they marginalise it because they consider it a remnant of colonialism [51]. Political fluctuations within the government may lead to changes in its internal policies, such as urbanisation policies and development priorities, which could increase the threats to cultural heritage [65,74]. More indirectly, foreign policies and the stability of states, or lack thereof, can cause conflicts and wars that completely debilitate heritage preservation management.

The government can be considered one of the main stakeholders in heritage management, but its role is completely different from that of other stakeholders. The stakeholders who are referred to as having a strong influence on the failure of heritage management are the local community or individuals and organisations affected by and influence heritage plans. However, they do not have the powers that the government has.

Stakeholders play an important role in heritage management planning. They can be considered a significant driver of the success or failure of conservation and management plans [4,78]. Their participation is essential in correctly identifying and mapping important features of heritage sites, capturing all sites’ value, and including them in plans. For example, ignoring some critical values of the local community may generate negative views [12,55]. Understanding stakeholders’ interests and perspectives is essential in involving relevant groups in decision-making and anticipating common interests or potential conflicts. The neglect of stakeholders generates mistrust and a lack of communication, which may impede the effective management of heritage sites. Some attribute the lack of stakeholder inclusion in planning and management processes to the difficulty in dealing with many participants. However, research indicates that involving small groups in management as delegates enables them to assume responsibility for the presentation of plans to all critical stakeholders for assessment, feedback, and adjustment, depending on the suggestions presented [79].

Due to its importance, involving stakeholders in management processes is included in the laws and legislation of some countries, some of which explicitly indicate the need to involve the police and other state services [50]. This shows the recognition of stakeholders such as government agencies and the local community, making it difficult for planners or decision-makers to ignore them. In contrast, uncertainty leaves the stakeholder engagement assessment to planners, who often give control to influential groups and exclude vulnerable minorities who may be primarily interested in these sites [59].

Laws and legislation are the reference points for all state policies [55,63]. However, governments are the ones that formulate heritage laws and strategies. Governments sometimes find that these laws exist but that developing or changing their outline strategies requires significant time and effort [54]. This is something that some governments do not do in their early stages because heritage is sometimes not considered a priority. Therefore, such legislation may be used for many years, despite its defects and incompatibility with the site conditions and environmental changes [16,49]. Beyond advocacy, only the government has the power to engage in such revisions.

As mentioned previously, legislation is essential in influencing the government and stakeholders. This makes it a direct influence on the effectiveness of heritage management plans, in addition to several other aspects, such as the weakness of the penalties specified by the law for crimes of infringement on heritage, which causes their continuation and a lack of deterrence regarding their perpetrators [52].

The three elements mentioned here (the government—stakeholders, laws, and legislation) have the strongest influences on heritage management and the effectiveness of its plans. This is because, between them, they encompass many of the aspects indicated by the selected studies (see Table 4). Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge the significance of administrative performance, as these studies indicate that it is a primary factor contributing to management ineffectiveness. The impact of deficiencies in administrative performance can be mitigated if administrators are provided with an appropriate and supportive work environment, sufficient resources, and robust legislation to support their efforts.

Figure 5 presents a conceptual framework that brings together the elements that the authors believe are important in influencing the effectiveness of heritage management and conservation, as indicated by this literature review, which can be considered when evaluating the efficacy of cultural heritage management plans.

Figure 5.

A conceptual framework of factors contributing to effective cultural heritage management.

The framework, consisting of 29 detailed factors, influences the effectiveness of heritage. Although these aspects require thorough examination, this paper does not explore potential solutions or mitigation strategies. Instead, its scope is limited to laying the groundwork for an understanding of the heritage conservation challenges. Addressing these challenges and proposing solutions is a broad task due to the complex nature of heritage and the different causes of management failure in each country and sometimes in each location, which makes it worthy of a separate and dedicated investigation.

Therefore, with a government that supports cultural heritage and aims to pass it on to future generations, there will be sufficient financial support and supportive government coordination for all institutions concerned with heritage. In addition, strict and up-to-date legislation and laws covering all aspects of the current state of heritage preservation are required. When these basics are available, administrative plans can be developed by experienced and competent planners and decision-makers in government institutions approved by the state. Furthermore, all relevant stakeholders must be involved in planning and fully cooperate with management. Notably, all these steps can only function as intended if they are understood correctly and clearly and are free from undue complexity and ambiguity. If all of these components are present, appropriate and efficient plans for heritage management can be created.

Nevertheless, it must be appreciated that heritage management, even if planned well, remains, at some level, inherently vulnerable to failure, whether due to implementation failure or unforeseen or difficult-to-predict hazards, such as natural disasters or armed conflict. This underscores the need for robust and in-depth heritage management strategies.

5. Conclusions

This literature review highlights the effectiveness of heritage management in conserving tangible cultural heritage. This paper analysed a selection of articles to identify the strategies used in heritage conservation. The analysis identified 29 factors that contribute to heritage management’s ineffectiveness. These have been classified into six categories: administrative institutions; stakeholders; financial resources; natural and human hazards; laws and legislation; and political issues.

Most of the factors can be categorised as relating primarily to administrative institutions, starting with insufficient coordination between institutions concerned with heritage, a lack of technical and professional personnel, a lack of planning procedures to achieve effective management, and the complexity of administrative plans. Moreover, it has been highlighted that there is a lack of oversight over these institutions. The following most prominent categories, as identified in the literature, are the stakeholders, financial resources, natural disasters, and human threats, each of which can be attributed to underlying causes. Regarding stakeholders, neglect of their inclusion in the various planning stages was attributed as a significant cause of management failure, in addition to insufficient awareness, especially from the local community, of the importance of heritage preservation. A lack of financial resources, reliance on external financing, and inadequate funding for heritage management were among the factors that contributed to the impact of the financing on effectiveness. As for the various threats that sometimes occur unexpectedly, such as earthquakes and floods, it has been pointed out that a lack of preparedness for disasters is one of the reasons for the failure of conservation measures. Furthermore, it has been noted that the absence of laws and legislation, a lack of clarity in their provisions, and the effectiveness of their implementation are the aspects in which legislation affects effectiveness. The last frequently cited factor contributing to the inefficiency of cultural heritage management is political problems, namely state policies that do not support heritage or cause political fluctuations.

After further analysing of these factors, a conceptual framework was developed. This framework establishes a connection between the elements proposed by the authors as the main factors influencing the management processes of heritage conservation. It can be used as a reference point to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the management of heritage sites.

It was found that the main driver of most of these factors is the government, which plays the most significant role in influencing most of the aspects above. In addition to the various stakeholders and their roles, which cannot be overlooked in the success or failure of heritage administrations’ management efforts, laws and legislation were found to be highly influential in their function as a regulatory mechanism of administrative operations and implementation. The framework also includes administrative performance, which is significant in proper management planning. Poor performance may lead to management and conservation efforts failing, even if all other process aspects are in place. The framework also indicates the necessity of transparency in all procedures included in the administrative process for ease of interpretation and implementation, in the manner in which they were designed.

Research on cultural heritage management is ongoing and it requires additional investigation. The surrounding environment, a given example of cultural heritage, may change and give rise to additional aspects that impact the efficacy of conservation measures. These factors might be considered to update the suggested framework when applied to a specific local or national case. Moreover, studies might address obstacles to heritage efficacy, such as formulating strategies to enhance the management efficiency. Furthermore, this study’s limitation is that most of the selected research focuses on global cultural heritage. Consequently, it is feasible to suggest conducting research that explicitly addresses the difficulties that heritage sites encounter in a local context, as they are likely to encounter distinct obstacles.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17010366/s1. PRISMA Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, F.S., G.S. and M.N.; methodology, F.S., G.S. and M.N.; software, F.S.; validation, F.S.; formal analysis, F.S.; investigation, F.S. and M.N.; resources, F.S.; data curation, F.S. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, F.S., G.S. and M.N.; supervision, G.S. and M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or generated in this study are accessible from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

List of selected grey documents for research inclusion.

| No. | Grey Document |

| 1 | Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. |

| 2 | Enhancing our heritage toolkit: assessing management effectiveness of natural World Heritage Sites. |

| 3 | Management plans for world heritage sites. A practical guide. |

| 4 | Guidebook on standards for drafting cultural heritage management plans. |

| 5 | Managing cultural heritage world. |

| 6 | Enhancing our heritage toolkit 2.0: assessing management effectiveness of World Heritage properties and other heritage places. |

References

- Selim, G.; Farhan, S.L. Reactivating voice of the youth in safeguarding cultural heritage in Iraq: The challenges and tools. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2024, 1, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, Y. Cultural Heritage and Human Rights. In Oxford Handbook on International Cultural Heritage Law; University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Acampa, G.; Parisi, C.M. Cultural heritage management: Optimising procedures and maintenance costs. Valori Valutazioni 2021, 29, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitri, I.; Ahmad, Y.; Ahmad, F. Conservation of tangible cultural heritage in Indonesia: A review current national criterion for assessing heritage value. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 184, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, A.; Gatisso, M. The conservation and preservation challenges and threats in the development of cultural heritage: The case of the Kawo Amado Kella Defensive Wall (KAKDW) in Wolaita, Southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinas, S. Contemporary Theory of Conservation; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780080476834. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, S.; Worthing, D. Managing Built Heritage: The Role of Cultural Values and Significance, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-118-29875-6. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M.; Srakar, A. The unbearable sustainability of cultural heritage: An attempt to create an index of cultural heritage sustainability in conflict and war regions. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korro Bañuelos, J.; Rodríguez Miranda, Á.; Valle-Melón, J.M.; Zornoza-Indart, A.; Castellano-Román, M.; Angulo-Fornos, R.; Pinto-Puerto, F.; Acosta Ibáñez, P.; Ferreira-Lopes, P. The role of information management for the sustainable conservation of cultural heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre, M. Values and heritage conservation. Herit. Soc. 2013, 6, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajialikhani, M. A systematic stakeholders management approach for protecting the spirit of cultural heritage sites. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/41/ (accessed on 5 September 2010).

- Kilit, R.; Disli, G. Management planning of a rock-cut settlement: The case of the Taskale heritage site in Turkey. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2023, 24, 92–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omayio, E.; Sreedevi, I.; Panda, J. Introduction to heritages and heritage management: A preview. In Digital Techniques for Heritage Presentation and Preservation; Jayanta Mukhopadhyay, J., Sreedevi, I., Chanda, B., Chaudhury, S., Namboodiri, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-57906-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vacharopoulou, K. Conservation and management of archaeological monuments and sites in Greece and Turkey: A value-based approach to Anastylosis. Inst. Archaeol. 2005, 16, 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, Y.; El-Gamil, R. Cultural Heritage Management in Turkey and Egypt: A comparative study. Int. J. Akdeniz Univ. Tour. Fac. 2018, 6, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisci, F.; Gon, M.; Cicero, L. Managing a world heritage site in Italy as Janus Bifrons: A “decentralised centralisation” between effectiveness and efficiency. In Entrepreneurship in Culture and Creative Industries: Perspectives from Companies and Regions; Innerhofer, E., Pechlaner, H., Borin, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 297–310. ISBN 978-3-319-65506-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, S. A planning model for the management of archaeological sites. In The Conservation of Archaeological Sites in the Mediterranean Region, An International Conference Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 6–12 May 1995; Tidwell, S., Ed.; J. Paul Getty Trust: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Demas, M. Planning for conservation and management of archaeological sites: A values-based approach. In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites, An International Workshop Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and Loyola Marymount University, Corinth, Greece, 19–22 May 2000; Getty Publications: Corinth, Greece, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Paolini, A.; Vafadari, A.; Cesaro, G.; Quintero, M.S.; Van Balen, K.; Vileikis, O. Risk Management at Heritage Sites: A Case Study of the Petra World Heritage Site; UNESCO: Amman, Jordan, 2012; ISBN 978-92-3-001073-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R.; Avrami, E. Heritage values and challenges of conservation planning. In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites; Teutonico, J., Palumbo, G., Eds.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-89236-691-0. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). A Compendium of Key Decisions on the Conservation of Cultural Heritage Properties on the UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- DHLGH. A Guide to World Heritage Nomination; World Heritage Advice Series No. 1; Ireland’s World Heritage: Dublin, Ireland, 2023; Available online: https://www.worldheritageireland.ie/publication/a-guide-to-world-heritage-nomination-world-heritage-advice-series-no-1/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- El-Ashmawy, A. Protecting heritage buildings from disaster risks. Int. J. Multidiscip. Stud. Archit. Cult. Herit. 2022, 5, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, L.; Vadher, A.; Sarac, M.; Başoglu, D.; Teller, J. Using organigraphs to map disaster risk management governance in the field of Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Sharing Best Practices in World Heritage Management. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/recognition-of-best-practices/ (accessed on 18 November 2013).

- UNESCO. Three Sites Withdrawn from UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/133 (accessed on 13 July 2005).

- Thiaw, I. The Management of Cultural World Heritage Sites in Africa and Their Contribution to Sustainable Development in the Continent. In The Management of Cultural World Heritage Sites and Development In Africa: History, Nomination Processes and Representation on the World Heritage List; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 68–82. ISBN 978-1-4939-0482-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. Cultural and heritage tourism: A tool for sustainable development. Glob. J. Commer. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 6, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, L.; Guglielmetti Mugion, R.; Renzi, M.F. Heritage and identity: Technology, values and visitor experiences. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuvaza, S.; Makuvaza, V. Conservation issues, management initiatives and challenges for implementing Khami world heritage site management plans in Zimbabwe. In Aspects of Management Planning for Cultural World Heritage Sites: Principles, Approaches and Practices; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 103–117. ISBN 978-3-319-69856-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkalbasi, N.; Bauer, K.; Glover, J.; Wang, L. Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, M.S.; Hadzibegovic, S.; Lena, A.; Haverkamp, W. The difference in referencing in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. ESC Heart Fail. 2019, 6, 1291–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.; Kanaoka, K.; Park, J. Tracking the diffusion of industrial symbiosis scholarship using bibliometrics: Comparing across Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, London, UK, 13 May 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Ariffin, N.; Aziz, F.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Feng, S. Potential of sense of place in cultural heritage conservation: A systematic review. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 31, 1465–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lame, G. Systematic literature reviews: An introduction. In Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design, Delft, The Netherlands, 5–8 August 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najar, B. The effectiveness management in organisations. J. Educ. Cult. Stud. 2020, 4, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, R.; Janjaria, M. Contributing management factors to performance management effectiveness. J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 1, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockings, M.; James, R.; Stolton, S.; Dudley, N.; Mathur, V.; Makombo, J.; Courrau, J.; Parrish, J. Enhancing Our Heritage Toolkit: Assessing Management Effectiveness of Natural World Heritage Sites; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 1–108. ISBN 978-92-3-000068-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Gong, Z. Management effectiveness evaluation of world cultural landscape heritage: A case from China. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali Aoudia, L.; Chennaoui, Y. The archaeological site of Tipasa, Algeria: What kind of management plan? Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2017, 19, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tokhais, A.; Thapa, B. Management issues and challenges of UNESCO world heritage sites in Saudi Arabia. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, G.; Jamhawi, M.; Al-Taher, H.; Farajat, I.; Orbasli, A. Learning from Participatory Practices: The Integrated Management Plan for Petra World Heritage Site in Jordan. J. Herit. Manag. 2023, 8, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somuncu, M.; Yigit, T. World heritage sites in Turkey: Current status and problems of conservation and management. World 2010, 2006, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei Goh, H. UNESCO World Heritage Site of Lenggong Valley, Malaysia: A Review of its Contemporary Heritage Management. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2015, 17, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosinski, M. New perspectives on world heritage management in the GCC legislation. Built Herit. 2022, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuvaza, S.; Chiwaura, H. African States Parties, Support, Constraints, Challenges and Opportunities for Managing Cultural World Heritage Sites in Africa. In The Management of Cultural World Heritage Sites and Development in Africa: History, Nomination Processes and Representation on the World Heritage List; Springer: London, UK, 2014; pp. 45–53. ISBN 978-1-4939-0482-2. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 12th ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- OSCE. Guidebook on Standards for Drafting Cultural Heritage Management Plans; Organisation for Security and Co-Operation in Europe: Helsinki, Finland, 2020; pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jelincic, D.; Tisma, S. Ex-ante evaluation of heritage management plans: Prerequisite for achieving sustainability. Ann. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2020, 30, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesuriya, G.; Thompson, J.; Young, C. Managing Cultural World Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 1–155. ISBN 978-92-3-001223-6. [Google Scholar]

- Saba, M.; Chanchi Golondrino, G.E.; Torres-Gil, L.K. A Critical Assessment of the Current State and Governance of the UNESCO Cultural Heritage Site in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. Heritage 2023, 6, 5442–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalash, S.G. Indigenous archaeology and heritage in Pakistan: Supporting Kalash cultural preservation through education and awareness. J. Community Archaeol. Herit. 2022, 9, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N. The cultural and natural heritage of caves in the Lao PDR: Prospects and challenges related to their use, management and conservation. J. Lao Stud. 2015, 5, 113–139. [Google Scholar]

- Erbey, D. An Evaluation of the Applicability of Management Plans with Public Participation. Idealkent 2016, 7, 428–442. [Google Scholar]

- Orbaslı, A.; Cesaro, G. Rethinking management planning methodologies: A novel approach implemented at Petra world heritage site. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2020, 22, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakkayan, B.; Akashah, F.; HanizaIshak, N. Conservation Plan for Historic Buildings from Building Control Administration Perspective. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Building Control Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 21 November 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Badia, F. Contents and Aims of Management Plans for World Heritage Sites: A Managerial Analysis with a Special Focus on the Italian Scenario. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2011, 1, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringbeck, B. Management Plans for World Heritage Sites; A practical guide; Brincks-Murmann, C., Fowler, A., Eds.; UNESCO: Bonn, German, 2008; ISBN 978-3-940785-02-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ciambrone, A. Istanbul World Heritage property: Representing the complexity of its Management Plan. In Proceedings of the World Heritage and Degradation Smart Design, Planning and Technologies, Naples, Italy, 16–18 June 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, A. Heritage conservation management in Egypt: A review of the current and proposed situation to amend it. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2018, 9, 2907–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, L.; Baraldi, S.B.; Gordon, C. Cultural heritage between centralisation and decentralisation: Insights from the Italian context. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2007, 13, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fushiya, T. Archaeological site management and local involvement: A case study from Abu Rawash, Egypt. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 324–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, R.; Maya, R.; Dalli, A.; Daghstani, W.; Mayya, S. The Syrian conflict’s impact on architectural heritage: Challenges and complexities in conservation planning and practice. J. Archit. Conserv. 2023, 29, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belge, B. Planning Challenges for Archaeological Heritage. In Urban and Regional Planning in Turkey; Ozdemir Sarı, B., Ozdemir, S., Uzun, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-05773-2. [Google Scholar]