Tourism-Led Rural Gentrification in Multi-Conservation Rural Settlements: Yazıköy/Datça Case

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Context: The Spatial and Social Characteristics of Yazıköy

3. Methods

4. Findings

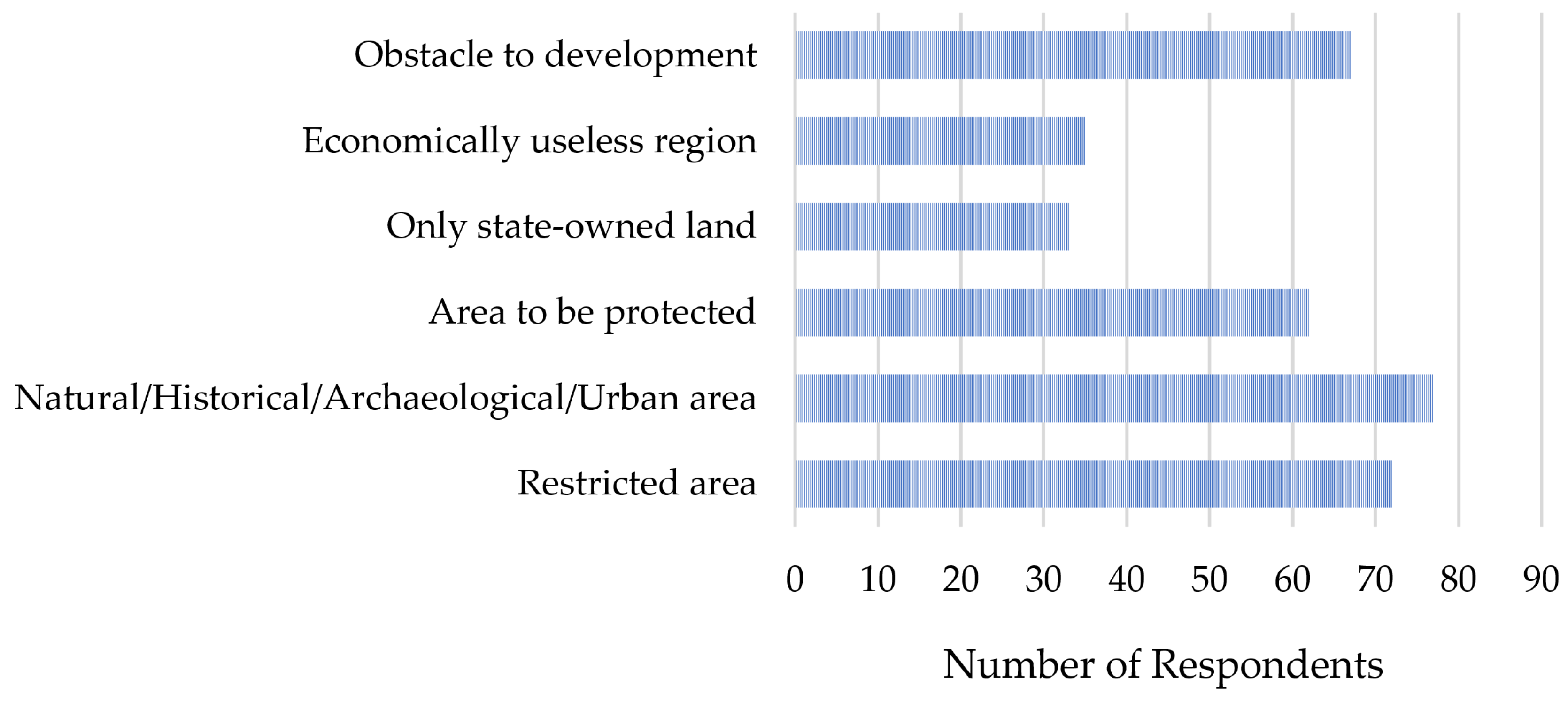

4.1. Survey Results

4.2. Interview Results

- perceived benefits and constraints of protected status;

- infrastructure and spatial planning challenges;

- community participation in conservation processes; and

- future-oriented recommendations for heritage management.

4.3. Synthesis

5. Discussion

- Rising Tourism and Economic Restructuring: The growing visibility of Knidos and the increased visitor numbers in Yazıköy have created new economic activities—home-style cafés, boutique rentals, and heritage-linked tourism jobs—which resemble the “tourism entrepreneur gentrifiers” described by [21,62]. These activities shift the village economy from agriculture to services and tourism [63].

- Infrastructure Strain and Local Frustration: As highlighted by residents and experts in the study, the inadequacy of roads, water, and waste infrastructure during peak tourist seasons mirrors challenges found in gentrifying rural areas globally [60,61,62,63,64,65]. These results are consistent with the findings of previous studies that the concept of site is considered as restricted areas [4], and that this restriction can lead to significant infrastructure deficiencies [5,6].

- Perception of Heritage Restrictions as Development Barriers: Similarly to tourism-gentrified areas in China and South Africa, many Yazıköy residents perceive conservation designations as “restricted zones” that limit farming, housing, and daily life [23,24]. This perception can lead to local resentment, especially when external actors gain more from tourism than long-term residents.

- Changing Cultural Landscape and Place Identity: The increased presence of visitors and entrepreneurs potentially introduces a different esthetic and functional use of space, shifting the “lived rurality” toward a commodified landscape—what some scholars call “imagined rurality” [22].

6. Conclusions

- Inclusive Planning Frameworks: A multi-level governance model should be adopted that includes all stakeholders, particularly the local population, in conservation decisions, alongside central and local authorities.

- Investment in Infrastructure: Current infrastructure deficiencies (roads, water and waste management) should be addressed and improved, considering the balance between tourists and local users, conservation and use.

- Enhancing Community Participation: Context-sensitive education and awareness programs should be developed to encourage the participation of both young and old populations.

- Economic Equity: Policies should be created to ensure that the benefits of conservation and tourism are distributed more equitably among village residents. For example, entrepreneurship models that support local crafts and agricultural products can be promoted.

7. Study Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gül Asatekin, N. Kültür ve Doğa Varlıklarımız, Neyi, Niçin, Nasıl Korumalıyız; Kültür Varlıkları ve Müzeler Genel Müdürlüğü Yayınları: Ankara, Turkey, 2004.

- Turkish Grand National Assembly LAW 2863. Off. Newsp. Repub. Türkiye 1983, 22, 444. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=2863&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dağıstan Özdemir, M.Z. Türkiye’de Kültürel Mirasın Korunmasına Kısa Bir Bakış. J. Chamb. City Plan. Union Chamb. Turk. Eng. Archit. 2005, 1, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vuruşkan, A.; Ortaçeşme, V. Antalya Kentindeki Doğal Sit Alanlarına İlişkin Sorunların İrdelenmesi. Akdeniz Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Derg. 2009, 22, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Serin, U. Threats and Vulnerabilities in Archaeological Sites: Case Study: Lasos. In Proceedings of the 15th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Monuments and Sites in Their Setting—Conserving Cultural Heritage in Changing Townscapes and Landscapes’, Xi’an, China, 17–21 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kejanli, D.T.; Dinçer, İ. Conservation and Planning Problems in Diyarbakır Castle City. Megaron J. 2011, 6, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments. In The First International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments; The International Museums Office: Athens, Greece, 1931; Available online: https://www.icomos.org.tr/Dosyalar/ICOMOSTR_en0660984001536681682.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- International charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites (the Venice charter). In IInd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments; ICOMOS: Florence, Italy, 1964; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters-and-doctrinal-texts/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Çoşkun, B.S. İstanbul’daki Anıtsal Yapıların Cumhuriyet Dönemindeki Koruma ve Onarım Süreçleri Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Ph.D. Thesis, Mimar Sinan University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe (CoE). The Declaration of Amsterdam; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1975; Available online: https://www.icomos.org.tr/Dosyalar/ICOMOSTR_en0458431001536681780.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Dincer, I. Kentleri Dönüştüren Korumayı ve Yenilemeyi Birlikte Düşünmek: “Tarihi Kentsel Peyzaj” Kavramının Sunduğu Olanaklar. Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2013, 1, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Selman, P.; Knight, M. On the Nature of Virtuous Change in Cultural Landscapes: Exploring Sustainability through Qualitative Models. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhitova, T.V. Rethinking Conservation: Managing Cultural Heritage as an Inhabited Cultural Landscape. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2015, 5, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. Reconnecting the City the Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agnoletti, M. Rural Landscape, Nature Conservation and Culture: Some Notes on Research Trends and Management Approaches from a (Southern) European Perspective. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2014, 126, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, R.; La Sala, P.; De Pascale, G.; Faccilongo, N. The Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Rural Areas: Stakeholder Preferences Regarding Historical Rural Buildings in Apulia, Southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, V.A.; Hobbs, R.J.; Standish, R.J. What’s New about Old Fields? Land Abandonment and Ecosystem Assembly. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Riguccio, L.; Carullo, L.; Tomaselli, G. Using the Analytic Hierarchical Process to Define Choices for Re-Using Rural Buildings: Application to an Abandoned Village in Sicily. Nat. Resour. 2013, 4, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Conservation and Revitalization of Rural Heritage: A Case Study of the Mountainous Traditional Village. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2023, 13, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynep, E.; Eyüpgiller, K.K. Türkiye’de Geleneksel Kırsal Mimarinin Korunması: Tarihsel Süreç, Yasal Boyut; YEM Yayın: Istanbul, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, R. Small Town Tourism in South Africa; Springer: Stellenbosh, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Xu, H. Producing an Ideal Village: Imagined Rurality, Tourism and Rural Gentrification in China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T. Tourism-Led Rural Gentrification: Impacts and Residents’ Perception. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakarya, İ.; Başaran Uysal, A. Rural Gentrification in the North Aegean Countryside (Turkey). Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2018, 6, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Jáuregui, C.; Concepción, E.D. Effects of counter-urbanization on Mediterranean rural landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 3695–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocer, O.; Shrestha, P.; Boyacioglu, D.; Gocer, K.; Karahan, E. Rural gentrification of the ancient city of Assos (Behramkale) in Turkey. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabıyık, C.; Loopmans, M. Seasonal gentrification and its (dis) contents: Exploring the temporalities of rural change in a Turkish small town. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk Büke, F.G. Tourism-led adaptive reuse of the built vernacular heritage: A critical assessment of the transformation of historic neighbourhoods in Cappadocia, Turkey. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2023, 14, 474–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, U.; Ecemiş Kılıç, S. Tracing the Pressure of Capital Concentration on Cultural Heritage Sites from Plan Revisions; Aliağa Kyme Ancient City Case. Kent. Akad. 2025, 18, 2031–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeterier, J.F. Lay People’s Evaluation of Historic Sites. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Problem Issues of Public Participation in Built-Heritage Conservation: Two Controversial Cases in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut Gültekin, N.; Uysal, M. Kültürel Miras Bilinci, Farkındalık ve Katılım: Taşkale Köyü Örneği. Int. J. Soc. Res. 2018, 8, 2030–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Timothy, D.J.; Öztürk, Y. Tourism Growth, National Development and Regional Inequality in Turkey. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ahmad, A.G.; Barghi, R. Community Participation in World Heritage Site Conservation and Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seila, F.; Selim, G.; Newisar, M. A Systematic Review of Factors Contributing to Ineffective Cultural Heritage Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, E.; Mamì, A.; Giampino, A.; Amato, V.; Romano, F. Adaptive Incremental Approaches to Enhance Tourism Services in Minor Centers: A Case Study on Naro, Italy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardak, F.S. Community Engagement and Heritage Awareness for the Sustainable Management of Rural and Coastal Archaeological Heritage Sites: The Case of Magarsus (Karataş, Turkey). Sustainability 2025, 17, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, P. Kitab-ı Bahriye: Denizlerin Bilgeliği Yüzyılların Deniz Kılavuzu; Demirören Yayınları: İstanbul, Turkey, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, U. Sorularla Evliya Çelebi: Insanlık Tarihine Yön Veren 20 Kişiden Biri; Hacettepe Üniversitesi: Ankara, Turkey, 2011; ISBN 9789754913095. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, G.E.; Cook, J.M. The Cnidia. Annu. Br. Sch. Athens 1952, 47, 171–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Ö.S. Datça Yarımadasına Yerleşmenin Tarihsel Süreci. Istanb. Univ. Edeb. Fak. Cograf. Bol. Cograf. Derg. 2008, 16, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tuna, N. Knidos Teritoryumu’nda Arkeolojik Araştırmalar Archaeological Investigations at the Knidian Territorium; Aydan Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koparal, E.; Tuna, N.; Iplikçi, A.E. Hellenistic Wine Press in Burgaz/Old Knidos. Metu J. Fac. Archit. 2014, 31, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilker, S.T.; Leidwanger, J.; Greene, E.S. Amphoras and the afterlife of a commercial port: Hellenistic Burgaz on the Datça (Knidos) peninsula. Herom J. Hell. Rom. Mater. Cult. 2019, 8, 357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Kutukcuoglu, B. Microecologies of a Mediterranean Enclave: “Remote” Reading of Datça Peninsula and Its Traditional Villages. Mediterr. Stud. 2022, 30, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doksanaltı, E.; Karaoğlan, I.; Tozluca, D.O. Knidos Denizlerin Buluştuğu Kent; Bilgin Kültür Sanat: Ankara, Turkey, 2018; ISBN 9786059636421. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, M. Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgeleri Yönetimi ve Sürdürülebilir Çevre Koruma Anlayışının Oluşumuna Etkisi: Datça Bozburun Örneği. Master’s Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Grand National Assembly LAW 6360. Off. Newsp. Repub. Türkiye 2012, 53. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=6360&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Taşlıgil, N. Tourism and Special Environmental Protected Areas: Case of Datça-Bozburun. İzmir Aegean Geogr. J. 2008, 12, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kırca, L. Badem Üretiminin Bölgesel Analizi: Ege Bölgesi’nde Mevcut Durum ve Gelecek Potansiyeli. Ordu Üniversitesi Bilim. Ve Teknol. Derg. 2024, 14, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, R.; Penkova, R.; Wendt, J.A.; Saparov, K.T.; Berdenov, J.G. Developments in Social Sciences; St. Kliment Ohridski University Press: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017; ISBN 978-954-07-4343-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nayci, N. Architectural Characteristics and Conservation Problems of Traditional Rural Settlements of Datça-Bozburun Region. TÜBA-KED Türkiye Bilim. Akad. Kültür Envant. Derg. 2012, 10, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, İ. MÖ 1.Binde Guzana (Bit Bahiyani) Krallığı. Master’s Thesis, Yüzüncü Yıl University, Van, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, L. Tarihsel Kaynaklarda Roma, Bizans, Osmanlı Devri Limanlarının Anlatımı. Yeditepe Univ. Dep. Hist. Res. J. 2017, 1, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Özgürel, G.; Alkan, Ö.; Ok, S. Datça Badem Çiçeği Festivali’nin Yöre Turizmine Olası Etkileri: Yerel Esnaf Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Int. J. Soc. Econ. Sci. 2018, 8, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- TÜİK Address-Based Population Registration System Results; Turkey Statistical Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2023.

- Chachamovich, E.; Fleck, M.P.; Power, M. Literacy Affected Ability to Adequately Discriminate among Categories in Multipoint Likert Scales. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douven, I. A Bayesian Perspective on Likert Scales and Central Tendency. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M. Other geographies of gentrification. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2004, 28, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X. Uneven development and tourism gentrification in the metropolitan fringe: A case study of Wuzhen Xizha in Zhejiang Province, China. Cities 2022, 121, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. Differential productions of rural gentrification: Illustrations from North and South Norfolk. Geoforum 2005, 36, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.P.; Phillips, D.A. Socio-cultural representations of greentrified Pennine rurality. J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.R.; Richards, G. (Eds.) Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale, A. The diverse geographies of rural gentrification in Scotland. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leebrick, R.A. Rural Gentrification and Growing Regional Tourism: New Development in South Central Appalachia. Curr. Perspect. Soc. Theory 2015, 34, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoschka, M.; Sequera, J.; Salinas, L. Gentrification in Spain and Latin America a critical dialogue. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1234–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Beyond displacement: The co-existence of newcomers and local residents in the process of rural tourism gentrification in China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikšić Radić, M.; Dragičević, D. Integrative Review on Tourism Gentrification and Lifestyle Migration: Pathways Towards Regenerative Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, E. Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgelerinde Turizm Baskisi Ve Datça-Bozburun Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgesi İçin Turizm Yönetim Plani Önerisi. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. The development of cultural tourism in Europe. In Cultural Attractions and European Tourism; Cabi Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Çuha, O. Kültür Turizmi Kapsamında Destekleyici Turistik Ürün Olarak Deve Güreşi Festivalleri Üzerine Bir Alan Çalişması. Yaşar Univ. E-J. 2008, 12, 1827–1852. [Google Scholar]

- Köşker, H. Ahlat’ın Kültürel Turizm Potansiyeli Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Mukaddime 2018, 9, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, M.; Bayuk, M. Archaeological Site Area Marketing of Tourism Destinations: A Research After 2019 Göbeklitepe Year. J. Appl. Tour. Res. 2020, 1, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Aliefendioğlu, Y. Türkiye’de Koruma Alanlarindaki Taşinmazlarin Kullanimi ve Koruma Statülerinin Taşinmaz Piyasalari ve Değerlerine Etkileri: Muğla İli Örneği. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rahemtulla, Y.G.; Wellstead, A.M. Ecotourism: Understanding the Competing Expert and Academic Definitions; Canadian Forest Service, Northern Forestry Centre: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2001.

- Belen, N. Termessos Arkeolojik Sit Alani’nin Ekomüze Kapsaminda Değerlendirilmesi. Master’s Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M.; Duman, T. Reviving Second Homes in Tourism Sector: The Case of Muğla-Datça Province. Doğuş Üniversitesi Derg. 2011, 12, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, B. Quality of Life as a Criterion for the Conservation of Rural Landscapes: The Case of Karaköy, Datça. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–30 | 14 | 12.3% |

| 31–59 | 50 | 43.9% | |

| 60+ | 50 | 43.9% | |

| Gender | Female | 63 | 55.3% |

| Male | 51 | 44.7% | |

| Years living in Yazıköy | Less than 10 years | 18 | 15.8% |

| 10–30 years | 36 | 31.6% | |

| 30+ years | 60 | 52.6% | |

| Sense of belonging | Yes | 92 | 80.7% |

| No/Neutral | 22 | 19.3% |

| Activity | 18–30 (%) | 31–59 (%) | 60+ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knidos site visits | 78% | 62% | 38% |

| Almond Blossom Fest | 84% | 76% | 61% |

| Heritage workshops | 66% | 44% | 20% |

| Participant Code | Occupation/Role | Connection to Yazıköy | Years of Experience | Type of Knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Excavation Director/ Academician | Leads archeological work in Knidos | 34 | Institutional/Expert |

| P2 | Village Headman (Muhtar) | Elected local authority in Yazıköy | 35 | Community/Administrative |

| P3 | Tour Guide | Conducts cultural tours in the area | 10 | Heritage Interpretation |

| P4 | Elderly Farmer | Lifelong resident and landowner | 87 | Traditional/Local Knowledge |

| P5 | Real Estate Agent | Sells and manages local properties | 60 | Economic/Regulatory |

| Theme | Summary Insight | Sample Quote (Participant) |

|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure Inadequacy | Current services do not meet seasonal tourism demand | “We still don’t have ambulance access” (P2) |

| Regulatory Constraints | Residents face barriers in obtaining building permissions | “Even tree planting needs approval” (P5) |

| Economic Inequality | Locals cannot access tourism income equally | “Only outsiders are profiting” (P3) |

| Identity and Pride | Community takes pride in its heritage but feels excluded from decisions | “We protect this land, but they don’t ask us” (P4) |

| Interview Results | Survey Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | |||

| Positive Reviews | Area to be protected | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Protecting the values of the people/belonging | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Increased recognition | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Organizing social and cultural activities | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Irregular construction is not allowed | x | x | x | ||||

| Providing economic contribution | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Increasing demand for zoned land and housing | x | x | |||||

| Increase in the number of visitors | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| The site boundaries are made according to the relevant conditions of the relevant period. | x | ||||||

| Attending events and going on trips | x | ||||||

| Negative Comments | Private property problems | x | x | x | |||

| Use of stones from the ancient city | x | ||||||

| Increased environmental pollution | x | x | x | ||||

| Infrastructure deficiencies | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| The road is narrow/traffic congestion/cannot be used in emergencies | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Having parking problems | x | x | x | ||||

| The length of the process regarding zoning and permits for new construction | x | x | x | x | |||

| Increase in illegal construction | x | x | x | ||||

| Inability to plant/plough/maintain trees in fields | x | x | x | ||||

| Lack of awareness-raising activities | x | x | |||||

| Loss of value in undeveloped lands | x | x | x | ||||

| Key Issues |

| Negative Perceptions of Site Areas—Site areas are seen as economic restrictions |

| Infrastructure Deficiencies—Inadequate roads, utilities, and internet |

| Property and Regulatory Challenges—Lengthy permits, informal construction |

| Limited Local Participation—Poor central communication, low engagement |

| Opportunities |

| Economic Benefits of Tourism—Job creation, conservation support |

| Youth Participation—High youth involvement in heritage |

| Potential for Awareness-Raising—Older residents can be engaged |

| Recommendations |

| Re-evaluate Site Boundaries—Balance conservation and local needs |

| Invest in Infrastructure—Meet the demands of residents and tourists |

| Develop Supportive Economic Policies—Align livelihoods and heritage |

| Expand Education and Awareness Programs—Engage all age groups |

| Enhance Community Participation—Build local trust and inclusion |

| Adapt and Replicate Lessons—Apply the model to other rural areas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sözen, B.; Kılıç, S.E. Tourism-Led Rural Gentrification in Multi-Conservation Rural Settlements: Yazıköy/Datça Case. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188439

Sözen B, Kılıç SE. Tourism-Led Rural Gentrification in Multi-Conservation Rural Settlements: Yazıköy/Datça Case. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188439

Chicago/Turabian StyleSözen, Begüm, and Sibel Ecemiş Kılıç. 2025. "Tourism-Led Rural Gentrification in Multi-Conservation Rural Settlements: Yazıköy/Datça Case" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188439

APA StyleSözen, B., & Kılıç, S. E. (2025). Tourism-Led Rural Gentrification in Multi-Conservation Rural Settlements: Yazıköy/Datça Case. Sustainability, 17(18), 8439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188439