Beyond Satisfaction: Authenticity, Attachment, and Engagement in Shaping Revisit Intention of Palace Museum Visitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

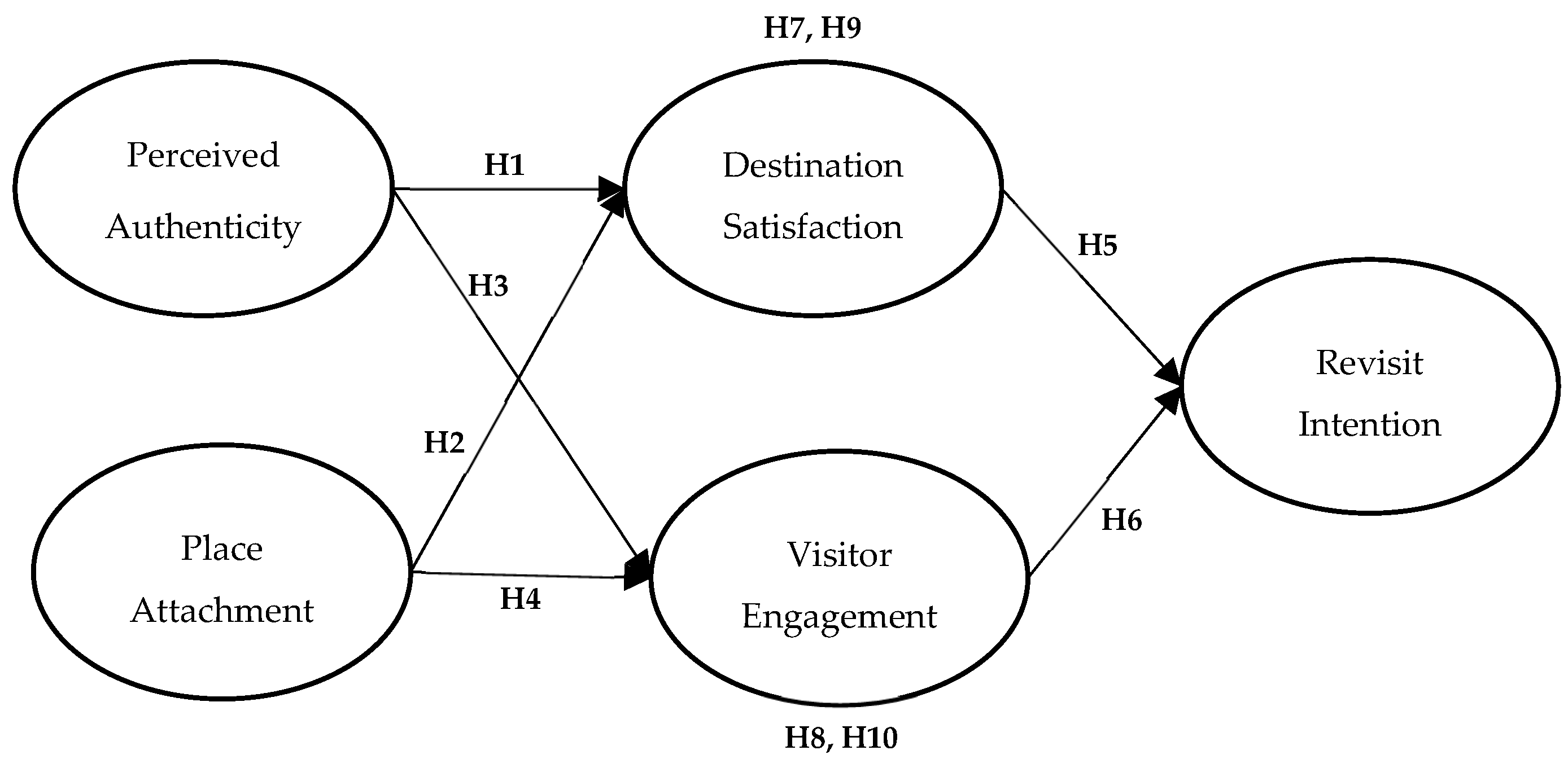

2. Literature Review and Model Development

2.1. Perceived Authenticity

2.2. Place Attachment

2.3. Destination Satisfaction

2.4. Visitor Engagement

2.5. Revisit Intention

2.6. The Mediating Role of Destination Satisfaction and Visitor Engagement

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

4.3. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Significance and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kay Smith, M.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and Wellbeing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Lin, V.S.; Xiao, H. Integrating Authenticity, Well-Being, and Memorability in Heritage Tourism: A Two-Site Investigation. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, F.; Yayla, O.; Guven, Y.; Ergun, G.S.; Demir, E.; Erol, S.; Yıldırım, M.N.O.; Keles, H.; Gozen, E. The Perception of Cultural Authenticity, Destination Attachment, and Support for Cultural Heritage Tourism Development by Local People: The Moderator Role of Cultural Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azab, M.; Abulebda, M. Cultural Heritage Authenticity: Effects on Place Attachment and Revisit Intention Through the Mediating Role of Tourist Experience. J. Assoc. Arab Univ. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 24, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; So, K.K.F.; Zheng, C. Perceived Authenticity and Place Attachment: New Findings from Chinese World Heritage Sites. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 47, 800–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lee, T.J.; Hyun, S.S. Visitors’ Self-Expansion and Perceived Brand Authenticity in a Cultural Heritage Tourism Destination. J. Vacat. Mark. 2025, 13567667241309122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y. Research on the Effect of Authenticity on Revisit Intention in Heritage Tourism. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 883380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A Consumer-Based Model of Authenticity: An Oxymoron or the Foundation of Cultural Heritage Marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Björk, P.; Weidenfeld, A. Authenticity and Place Attachment of Major Visitor Attractions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Hatamifar, P. Understanding Memorable Tourism Experiences and Behavioural Intentions of Heritage Tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Prayag, G.; Alrawadieh, Z.; Alsalameen, M. Self-Identification with a Heritage Tourism Site, Visitors’ Engagement and Destination Loyalty: The Mediating Effects of Overall Satisfaction. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chi, X.; Han, H. Perceived Authenticity and the Heritage Tourism Experience: The Case of Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, V.; Genc, S. The Effect of Perceived Authenticity in Cultural Heritage Sites on Tourist Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Aesthetic Experience. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 6, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.-K.; Lee, T.J. The Role and Dimensions of Authenticity in Heritage Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.H. A Reflective–Formative Hierarchical Component Model of Perceived Authenticity. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 1211–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Phau, I.; Hughes, M.; Li, Y.F.; Quintal, V. Heritage Tourism in Singapore Chinatown: A Perceived Value Approach to Authenticity and Satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly, J.M. A Review of Authenticity Research in Tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on Authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 92, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Su, Y.; Su, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L. Perceived Authenticity and Experience Quality in Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Kunqu Opera in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Hua, H.-Y.; Li, W. Perceived Tourism Authenticity on Social Media: The Consistency of Ethnic Destination Endorsers. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 49, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Liu, Y.C. Deconstructing the Internal Structure of Perceived Authenticity for Heritage Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2134–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberghien, G.; Bremner, H.; Milne, S. Performance and Visitors’ Perception of Authenticity in Eco-Cultural Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.C.; Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G. Sense of Place and Place Attachment in Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.T.; Brown, G.; Kim, A.K.J. Measuring Resident Place Attachment in a World Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, N. Role of Place Attachment Dimensions in Tourists’ Decision-Making Process in Cittáslow. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štumpf, P.; Vojtko, V.; McGrath, R.; Rašovská, I.; Ryglová, K.; Šácha, J. Destination Satisfaction Comparison Excluding the Weather Effect. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 2404–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Mekker, M.; De Vos, J. Linking Travel Behavior and Tourism Literature: Investigating the Impacts of Travel Satisfaction on Destination Satisfaction and Revisit Intention. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 17, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Qu, H. Examining the Structural Relationships of Destination Image, Tourist Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty: An Integrated Approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Shen, C.; Wang, E.; Hou, Y.; Yang, J. Impact of the Perceived Authenticity of Heritage Sites on Subjective Well-Being: A Study of the Mediating Role of Place Attachment and Satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D.; Curran, R.; O’Gorman, K.; Taheri, B. Visitors’ Engagement and Authenticity: Japanese Heritage Consumption. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Sarmento, E.M. Place Attachment and Tourist Engagement of Major Visitor Attractions in Lisbon. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiony, G.; Chahine, P. The Effect of Authenticity towards Cultural Heritage Tourists’ Behavioral Intention: Case Study of the Graeco-Roman Museum. Pharos Int. J. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 3, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B. Customer Engagement With Tourism Brands: Scale Development and Validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Demystifying Customer Brand Engagement: Exploring the Loyalty Nexus. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholer, A.A.; Higgins, E.T. Exploring the Complexities of Value Creation: The Role of Engagement Strength. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Majchrzak, A. Enabling Customer-Centricity Using Wikis and the Wiki Way. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2006, 23, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, A.M., Jr.; O’Guinn, T.C. Brand Community. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and Purchase Consequences of Customer Participation in Small Group Brand Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer–Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, H.S.; Alawneh, K.A.; Alananzeh, O.A.; Khasawneh, M.; Masa’Deh, R. The Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth, Desintation Image, and Tourist Satisfaction on UNESCO World Heritage Site Revisit Intention: An Empirical Study of Petra, Jordan. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2023, 50, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.; Soundararajan, V.; Parayitam, S. Community Support and Benefits, Culture and Hedonism as Moderators in the Relationship between Brand Heritage, Tourist Satisfaction and Revisit Intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 7, 2525–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riptiono, S.; Wibawanto, S.; Raharjo, N.I.; Susanto, R.; Syaputri, H.S.; Bariyah, B. Tourism Revisit and Recommendation Intention on Heritage Destination: The Role of Memorable Tourism Experiences. J. Int. Conf. Proc. 2023, 6, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanik, J.; Yusuf, M. Effects of Perceived Value, Expectation, Visitor Management, and Visitor Satisfaction on Revisit Intention to Borobudur Temple, Indonesia. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyasa, I.G.B.K.; Tuti, M. Increasing Revisit Intention through Visitor Satisfaction to the Indonesian National Museum. JDM J. Din. Manaj. 2023, 14, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhan, G.; Zhou, N. The Impact of Destination Brand Authenticity and Destination Brand Self-Congruence on Tourist Loyalty: The Mediating Role of Destination Brand Engagement. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Cheung, C. Chinese Heritage Tourists to Heritage Sites: What Are the Effects of Heritage Motivation and Perceived Authenticity on Satisfaction? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Fu, S.; Huan, T.-C. Exploring the Influence of Tourists’ Happiness on Revisit Intention in the Context of Traditional Chinese Medicine Cultural Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. Destination Authenticity as a Trigger of Tourists’ Online Engagement on Social Media. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Republic of China. Introduction to The Palace Museum. Available online: https://www.chnmuseum.cn/portals/0/web/zt/gmdc2022/detail.html?id=2 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- People’s Republic of China. Number of Students of Formal Education by Type and Level—Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://en.moe.gov.cn/documents/statistics/2022/national/202401/t20240110_1099539.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Measurement and Meaning in Information Systems and Organizational Research: Methodological and Philosophical Foundations. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Papp-Váry, Á.; Szabó, Z. Digital Engagement and Visitor Satisfaction at World Heritage Sites: A Study on Interaction, Authenticity, and Recommendations in Coastal China. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, Y.; Kumail, T.; Pan, L. Tourism Destination Brand Equity, Brand Authenticity and Revisit Intention: The Mediating Role of Tourist Satisfaction and the Moderating Role of Destination Familiarity. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 751–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleddu, M.; Paci, R.; Pulina, M. Repeated Behaviour and Destination Loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, I.L.; Borza, A.; Buiga, A.; Ighian, D.; Toader, R. Achieving Cultural Sustainability in Museums: A Step Toward Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodi, C.A.M.; De Lucia, R.; Giunchi, C.; Molinari, P. Looking for a Balance Between Memories, Patrimonialization, and Tourism: Sustainable Approaches to Industrial Heritage Regeneration in Northwestern Italy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legget, J.; Labrador, A.M.T.P. Museum Sustainabilities. Mus. Int. 2023, 75, vi–xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Luo, J.M. Impact of Generativity on Museum Visitors’ Engagement, Experience, and Psychological Well-Being. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 42, 100958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 290 | 50.17 |

| Female | 288 | 49.83 | |

| Age | Under 18 years old | 111 | 19.20 |

| 18~25 | 48 | 8.30 | |

| 26~30 | 163 | 28.20 | |

| 31~40 | 112 | 19.38 | |

| 41~50 | 97 | 16.78 | |

| 51~60 | 47 | 8.13 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 419 | 72.49 |

| Single | 159 | 27.51 | |

| Travel Companion | Alone | 60 | 10.38 |

| Family | 174 | 30.10 | |

| Friend/s | 205 | 35.47 | |

| Spouse/Significant Other | 139 | 24.05 | |

| Educational Attainment | Elementary School Graduate | 47 | 8.13 |

| High School Graduate | 160 | 27.68 | |

| College Graduate | 282 | 48.79 | |

| Graduate Degree | 89 | 15.40 |

| Constructs | Mean | SD | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Authenticity | ||||||

| The overall architecture and exhibits reflect actual buildings of the past. | 3.43 | 1.26 | 0.770 | 0.899 | 0.920 | 0.623 |

| The overall settings as well as architecture and impression of the buildings inspired me. | 3.83 | 1.40 | 0.838 | |||

| I liked the way the sites blend with the attractive landscape/scenery/historical ensemble/town, which offers many other interesting places for sightseeing. | 3.43 | 1.28 | 0.781 | |||

| My visit(s) provided a thorough insight into cultural heritage sites’ historical eras. | 3.79 | 1.42 | 0.816 | |||

| I could feel the genuineness and authenticity through the experiences in the Palace Museum. | 3.42 | 1.26 | 0.756 | |||

| I felt the history, legends, and cultural characteristics (personalities) of the heritage sites. | 3.77 | 1.39 | 0.805 | |||

| I enjoyed the unique traditions and spiritual experiences. | 3.43 | 1.27 | 0.757 | |||

| Place Attachment | ||||||

| This destination is very special to me | 3.75 | 1.40 | 0.838 | 0.849 | 0.893 | 0.625 |

| I identify strongly with this destination. | 3.44 | 1.27 | 0.749 | |||

| This destination means a lot to me | 3.75 | 1.37 | 0.802 | |||

| I am very attached to this destination | 3.44 | 1.27 | 0.753 | |||

| Visiting this destination is more important to me than visiting other destinations. | 3.68 | 1.40 | 0.807 | |||

| Destination Satisfaction | ||||||

| I feel happy about the destination | 3.43 | 1.25 | 0.796 | 0.815 | 0.878 | 0.643 |

| I feel satisfied about the destination | 3.67 | 1.36 | 0.806 | |||

| I am pleased to have visited this destination. | 3.42 | 1.26 | 0.818 | |||

| I feel that I have a better understanding of local history and culture after visiting the destination. | 3.66 | 1.37 | 0.788 | |||

| VE_Enthusiasm | ||||||

| I am heavily into the Palace Museum. | 3.43 | 1.28 | 0.815 | 0.738 | 0.851 | 0.656 |

| I am passionate about the Palace Museum. | 3.63 | 1.37 | 0.816 | |||

| I am enthusiastic about the Palace Museum. | 3.43 | 1.26 | 0.799 | |||

| VE_Attention | ||||||

| I pay a lot of attention to anything about the Palace Museum. | 3.61 | 1.33 | 0.820 | 0.749 | 0.857 | 0.666 |

| Anything related to the Palace Museum grabs my attention. | 3.42 | 1.27 | 0.818 | |||

| I concentrate a lot in my visit at the Palace Museum. | 3.60 | 1.33 | 0.810 | |||

| VE_Absorption | ||||||

| When I am interacting with the Palace Museum, I forget everything else around me. | 3.41 | 1.27 | 0.835 | 0.786 | 0.875 | 0.700 |

| Time flies when I am interacting with the Palace Museum. | 3.71 | 1.38 | 0.841 | |||

| When interacting with the Palace Museum, it is difficult to detach myself. | 3.42 | 1.27 | 0.834 | |||

| VE_Interaction | ||||||

| I am someone who enjoys interacting with like-minded community in the Palace Museum. | 3.71 | 1.33 | 0.842 | 0.771 | 0.868 | 0.686 |

| I am someone who likes to actively participate in the Palace Museum community discussions. | 3.42 | 1.27 | 0.811 | |||

| In general, I thoroughly enjoy exchanging ideas with other people in the Palace Museum community. | 3.64 | 1.37 | 0.832 | |||

| VE_Identification | ||||||

| When someone criticizes the Palace Museum, it feels like a personal insult. | 3.41 | 1.27 | 0.856 | 0.754 | 0.859 | 0.671 |

| When I talk about the Palace Museum, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’ because the identity of the site suites me. | 3.65 | 1.31 | 0.819 | |||

| When someone praises the Palace Museum, it feels like a personal compliment. | 3.43 | 1.27 | 0.782 | |||

| Revisit Intention | ||||||

| I will revisit the Palace Museum in the future. | 3.61 | 1.31 | 0.796 | 0.734 | 0.849 | 0.653 |

| If given the opportunity, I will return to Palace Museum or similar ones in China. | 3.41 | 1.27 | 0.824 | |||

| The likelihood of my return to these heritage sites for another heritage travel/experience is high. | 3.57 | 1.33 | 0.804 |

| AUTH | ATT | DS | VE | RI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTH | 0.789 | ||||

| ATT | 0.774 | 0.790 | |||

| DS | 0.565 | 0.429 | 0.802 | ||

| VE | 0.209 | 0.781 | 0.682 | 0.899 | |

| RI | 0.218 | 0.153 | 0.778 | 0.846 | 0.808 |

| Relationships | β | t-Value | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Authenticity → Destination Satisfaction | 0.508 | 10.544 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Place Attachment → Destination Satisfaction | 0.399 | 8.164 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Perceived Authenticity → Visitor Engagement | 0.605 | 16.644 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Place Attachment → Visitor Engagement | 0.353 | 9.608 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Destination Satisfaction → Revisit Intention | 0.188 | 3.336 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Visitor Engagement → Revisit Intention | 0.672 | 12.846 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Relationships | β | SD | t-Value | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTH → DS → RI | 0.072 | 0.029 | 2.465 | 0.014 | Supported |

| AUTH → VE → RI | 0.434 | 0.039 | 11.139 | 0.000 | Supported |

| ATT → DS → RI | 0.058 | 0.025 | 2.247 | 0.025 | Supported |

| ATT → VE → RI | 0.262 | 0.033 | 7.834 | 0.000 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Q.; Ko, W. Beyond Satisfaction: Authenticity, Attachment, and Engagement in Shaping Revisit Intention of Palace Museum Visitors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198803

Fang Q, Ko W. Beyond Satisfaction: Authenticity, Attachment, and Engagement in Shaping Revisit Intention of Palace Museum Visitors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198803

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Qinzheng, and Wonkee Ko. 2025. "Beyond Satisfaction: Authenticity, Attachment, and Engagement in Shaping Revisit Intention of Palace Museum Visitors" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198803

APA StyleFang, Q., & Ko, W. (2025). Beyond Satisfaction: Authenticity, Attachment, and Engagement in Shaping Revisit Intention of Palace Museum Visitors. Sustainability, 17(19), 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198803

_Li.png)