Abstract

This study explores the intersection of sustainable fashion practices, fashion shows, and sociological insights to develop sustainable fashion education. It investigates how sustainable practices are integrated into the fashion industry and education programs. Moreover, it critically analyses the evolving role of the fashion show in a time when sustainability takes a central position. Additionally, this study shows the possibilities and problems presented by the emergence of virtual fashion experiences. The literature review investigates the difficulties the fashion industry faces when moving towards sustainability. It systematically explores a range of innovative solutions put forth by scholars and practitioners. Moreover, this report delves into the core principles of sociological perspectives, particularly in fashion sociology. It explores the emerging trend of virtual fashion, emphasising the essential role that fashion education plays in promoting sustainability awareness among designers, industry professionals, and consumers. Ultimately, this study aims to encourage the fashion industry towards a more sustainable future by decreasing the traditional tensions between sustainability and fashion. It highlights the urgent need for the industry to embrace sustainable practices and prioritise sustainability in fashion education.

1. Introduction

The fashion industry has consistently become one of the most significant global economic sectors. According to McKinsey’s State of Fashion report from 2017, if the global fashion industry were measured against the GDP of each nation, it would rank seventh in the world after India. By 2027, the industry is projected to reach a market size of $1103 billion, with a compound annual growth rate of 9.45% [1]. The dynamic and unpredictable nature of fashion, with its constantly evolving trends and styles, has consistently captivated the attention of consumers worldwide [2]. The rapid depletion of resources, environmental degradation, and social injustice connected to the fast fashion industry highlight the need for implementing more sustainable fashion practices [3]. Furthermore, sustainability offers a strategic plan for minimising harm to the fashion industry while safeguarding people and the environment and promoting long-term economic stability [4]. Nowadays, there is a certain amount of discussion and action on sustainability in the fashion industry. Some researchers try to conceptualise sustainable fashion, while more researchers focus on consumer behaviour and sustainable production. So, there is still a lot of work to be carried out in the fashion industry to ensure that the industry is more sustainable [5]. Therefore, the fashion industry should reassess the creation, manufacturing, and utilisation of fashion goods and reevaluate the framework and provision of fashion instruction [6]. Firstly, fashion is a product of popular culture and society’s changing attire, aesthetics, and style trends. Moreover, its logic conveys various facets and purposes of mental and emotional states [7]. According to our research, not all pieces of cloth can be called fashion; fashion mostly refers to the clothes and styles that are popular at a certain time. Secondly, we use the widely accepted definition of sustainability from the World Commission on Environment and Development [8]: “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. In the context of fashion, we concentrate on the sustainability of clothing fashion, considering social and environmental factors unique to the manufacturing and consumption of clothing. Finally, a fashion item may be referred to as “outdated” or “out of style” when it is no longer “in fashion”. In addition, some clothing items continue to be recognised as emblematic of a specific historical period and are frequently referred to as “vintage” or “retro”. Several private retailers and independent fashion boutiques establish specialised “vintage” or “retro” sections in their collections, frequently acquiring second-hand garments from various sources, including estate sales, thrift stores, or private collectors [9].

However, it is necessary to emphasise another significant fashion class known as “classics”. Classics are timeless works that stand the test of time and recur repeatedly because of their cultural significance and enduring appeal [10]. The classic design is still appealing in the face of fast fashion because of its timeless formal qualities and ability to adapt to modern demands. It also contributes significantly to the sustainable growth of the fashion industry by focusing on how young consumers perceive and experience classic design. One example is the Chanel wool tweed suit from the 1950s, a model for such timeless pieces due to its iconicity and universal appeal [11].

Therefore, it is possible to view fashion as connected to a specific era and cultural setting, with its meaning and ideals evolving [7]. Our primary interest in this study is fashion in the clothing sector. We do not include fashion elements in other areas, including hairstyles, industrial design, décor, etc. Our goal is to investigate and resolve fashion-related challenges in the garment industry. In summary, this project aims to connect fashion shows, sustainable practices, and sociological understandings in this setting to support a moment of change in the fashion industry and education.

Survey Background

The fashion industry, renowned for its dynamic nature and frequent introduction of new clothing lines, is an industry to which consumers have grown accustomed [12,13]. The tempo of the apparel sector engulfs substantial assets and advances widespread manufacturing, momentary utilisation, and subsequent elimination of attire [13]. The current linear economic model has caused social and environmental degradation, which has led to the rise of environmental issues and societal and political transformations that have raised doubts about the effectiveness of top-down approaches in the global fashion industry [14]. By embracing the circular economy and the slow fashion movement, the fashion industry has partially revolutionised itself to confront the linear traditional economic model and the threat to finite resources [15]. This project attempts to integrate educational frameworks with the shifting dynamics of the fashion industry, considering an ongoing transition in sustainable fashion education and an apparent vacuum in academics surveying the environmental and ethical aspects of the fashion design process [13]. Further systematic investigation and support for designers and industry are needed due to the limited academic surveying of the fashion design process, which primarily focuses on cultural and consumer elements and gives little attention to fashion’s environmental and ethical dimensions [6,16]. In this study, the authors aim to contribute to reshaping sustainable fashion practices, fashion shows (as major communication events for the sector), and fashion education. The key questions the study seeks to answer include: How can fashion shows and education be leveraged to advance sustainable fashion, and how do different groups interact with and view sustainable fashion in today’s industry? The survey aims to contribute to reshaping sustainable fashion education, addressing the crucial question of integrating sustainable practices into the future of the fashion industry and education programmes. When it comes to fashion shows, they are no longer just occasions to showcase clothes. Instead, fashion shows have become an essential conduit for designers to communicate various ideas and values, and these creations often defy expectations and expand the boundaries of what the fashion industry considers “acceptable” [16]. Fashion shows have significantly impacted the industry and are iconic in the sector. At the same time, the rise of social networking has brought previously untapped consumers into the spotlight, raising awareness of fashion shows and ensuring their continued importance [17]. Thus, this investigation commences with a thorough progressive function of the fashion exhibition when ecological change is at the forefront, delving into its multifaceted influence on ecological integrity and societal conventions. The ‘Fourth Globalization Industrial Revolution’ or ‘Fashion 4.0’ has had diverse ramifications on fashion design, facilitating the utilisation of state-of-the-art technology in conventional fashion design and obscuring the demarcations between the virtual and physical [18]. The literature review systematically analyses the numerous barriers the apparel industry encounters in its quest for societal sustainability and explores a variety of groundbreaking remedies proposed by scholars and experts. Furthermore, the literature review examines the sociological foundations, encompassing the diverse aspects introduced by virtual fashion encounters and the pivotal function of fashion instruction in cultivating consciousness about sustainability among designers, industry experts, and consumers.

2. Methodology

2.1. Database Selection and Search Strategy

Through a rigorous literature review across three prestigious academic databases—ERIC (Education Resources Information Centre); Taylor & Francis Routledge; and Scopus—this study sought to investigate the relationship between sustainable fashion; fashion education; and sociology. The search and selection process followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology, ensuring transparency, rigour, and reproducibility. Only high-quality, peer-reviewed papers were included in the review thanks to the systematic screening, selection, and analysis of the pertinent literature. The study’s credibility and thoroughness were increased using PRISMA (see Table 1) to document the information flow through the selection process, from identification through screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion [19]. These databases were selected because they cover a wide range of pertinent topics, such as sociology, fashion studies, and educational research:

- ERIC Database: The ERIC Database ERIC, a renowned repository for educational research, offered fundamental perspectives on the relationship between education and sustainable fashion [20]. The search was restricted to the terms “sustainable fashion”, AND “fashion education”, AND “sociology of fashion” because this study focused on fashion education. Filters were used to ensure that only peer-reviewed journal articles, research reports, and evaluation reports were included in the search for articles published between 2016 and 2024. There were 14 pertinent results from this search.

- Taylor & Francis Routledge: The search terms “sustainable fashion” AND “fashion education”, AND “sociology” were used to find Taylor & Francis Routledge, a major source for sociological and fashion education research [21]. The search parameters were the same as in ERIC. Although there were 27 results from this search, it was observed that the database’s scope was more limited than that of Scopus.

- The database ScopusAs an interdisciplinary database, Scopus provides extensive coverage of fashion and sociology, which makes it especially appropriate for this research [22]. Scopus’s search was more sophisticated, employing a series of targeted filters to guarantee accuracy and pertinence:

- Document Types: Books, research articles, journal articles, and conference papers were all included in the search.

- Subject Areas: Only documents in the fields of sociology and the arts were included in the search.

- Publication Stage: Only completed documents were considered.

- Keywords: Content about subjects, such as “Consumption Behaviour”, “Sustainable Development”, and “Sustainability”, was the focus of the search.

- Affiliation of the Author: Only papers written by British authors were featured.

- Language: Only English-language documents were chosen.

This approach yielded a condensed set of 137 documents from Scopus, which were subsequently examined for additional quality and relevancy.

Table 1.

PRISMA Flowchart table [19].

Table 1.

PRISMA Flowchart table [19].

| Stage | Description | Total Records | Details | Footnote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | Records identified through database searches (ERIC, Taylor & Francis, Scopus) | 178 records | ERIC: 14, Taylor & Francis: 27, Scopus: 137 | |

| Screening | Records after duplicates removed, records screened and assessed for eligibility | 158 records | 158 records screened and assessed | Screening Process: Initial records were screened by title and abstract for relevance. |

| Eligibility | Reports assessed for eligibility; selected studies included in review | 147 records | 147 relevant studies selected for further analysis | Eligibility: Only peer-reviewed studies published from 2016 to 2024 were included. |

| Inclusion | Studies included in the review, reports of total included studies | 137 studies | 137 studies were finally included in the review | |

| Exclusion | Exclusion reasons for non-relevant or non-peer-reviewed studies | Non-peer-reviewed, irrelevant focus, etc. | Reasons for exclusion: irrelevant content, non-peer-reviewed, 10 records | Exclusion: Studies not focused on sustainable fashion or not peer-reviewed were excluded. |

2.2. Screening of Documents and Final Selection

The first search across the three databases found 178 documents. After examining the abstracts of each document, duplicates were eliminated, leaving 158 articles. After thoroughly reviewing the abstracts, 137 pertinent articles were ultimately chosen for additional study.

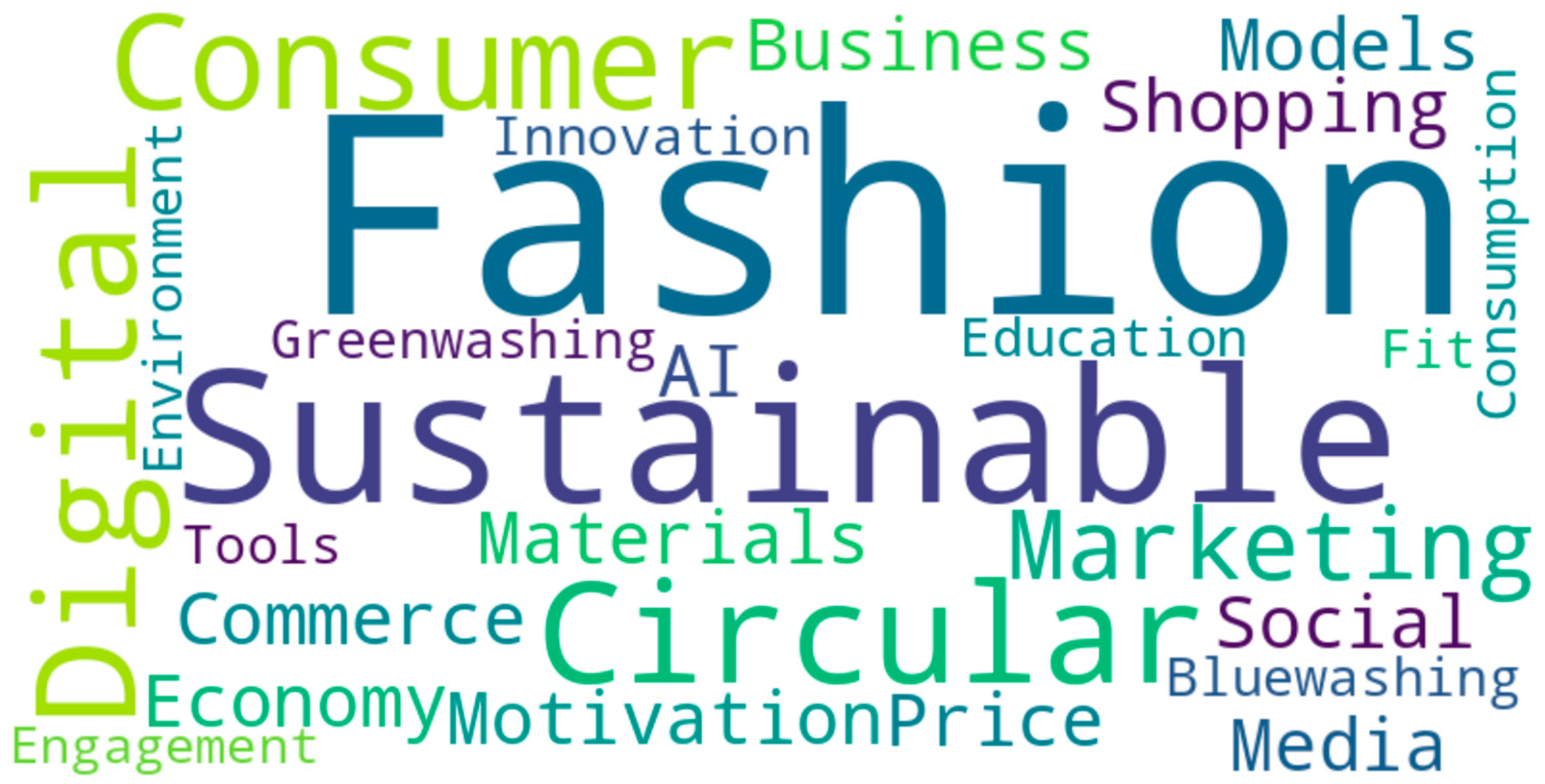

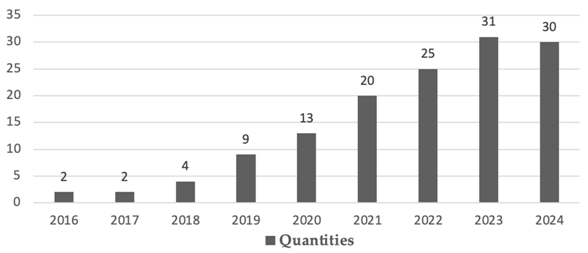

The number of articles published between 2016 and 2024 is highlighted in (Table 2), which shows the distribution of publications by year. The most used terms associated with sustainable fashion, fashion education, and sociology were also graphically represented in a keyword cloud (Figure 1) created from the RIS files. The keyword cloud illustrates the dynamic intersection of sustainable fashion, fashion education, and sociology. Consumer behaviour, marketing strategies, and the social and economic effects of fashion are all areas of growing interest in this field. Furthermore, the significance of circular economy principles and the role of technology are emerging as major themes in this area of study.

Table 2.

Publish Year and Quantities.

Figure 1.

Keyword Cloud.

The number of publications rose dramatically between 2016 and 2023, as shown in Table 1, indicating a rise in academic interest in fashion sociology, sustainable fashion, and fashion education. This pattern emphasises how sustainability is becoming more and more relevant globally and how it interacts with educational and sociocultural paradigms—the years with the highest number of publications in the chart; 2023 and 2024; also had the highest number of publications (30); suggesting that interest in these subjects peaked during this time. Environmental concerns and changes in consumer behaviour may have contributed to the surge in research. Global attention to sustainability and the social role of fashion may have been the main driver of this growth.

3. Taxonomy for Sustainable Fashion Research

The Kalbaska et al. [23] classification framework, ‘Taxonomy’, was used to analyse all the literature. Taxonomy is an organised method for classifying literature, especially when examining digital fashion and its interaction with sustainability, technology, and social impact [23]. The three levels that make up the framework are progressive in their relationship to one another.

- Fashion and Innovation (F&I): This foundational level concerns developing stylish products by combining cutting-edge design methods with technology. In fashion production, it looks at the methods and resources used to combine creativity and practicality.

- Influence and Sustainable Practices (I&S): The fashion industry’s adoption of sustainable practices is the focus of the second level. It entails creating sales campaigns, marketing plans, and operational procedures that support sustainability objectives.

- Education and Society (E&S): The framework’s highest level focuses on how fashion affects society and education. To shape the wider cultural and societal impact of fashion, it investigates how social interaction, communication, and educational activities affect trends, lifestyles, and consumer behaviour.

This hierarchy demonstrates a steady progression from fashion design to industry implementation at the sociocultural level. The sustainable fashion hierarchy was validated and improved using a top-down methodology, ensuring that every level is interconnected and able to capture the complex and multidimensional nature of digital fashion (see Table 3). Using this methodology, the study bridges design, industry practices, and sociocultural effects to offer a nuanced understanding of the interconnected dynamics within the digital fashion landscape.

Table 3.

Categories and Subcategories.

3.1. Fashion and Innovation

Fashion and Innovation are globalised according to five factors: (i) Sustainable fashion, (ii) Material Development, (iii) Design Practice, (iv) The Evolution and Impact of Fashion Shows, and (v) Circular Economy.

3.1.1. Sustainable Fashion

Due to growing environmental consciousness, sustainable fashion has recently progressed in apparel and related industries. Through the entire life cycle of clothing design, fabric manufacture, retailing, consumption, and disposal, from spinning, weaving, and dyeing to clothing, practical measures can be taken to reduce energy and material consumption and environmental pollution and achieve sustainable fashion [24,25]. This process depends heavily on the chemical dye and fibre manufacturing sectors, which are the main suppliers for the creation of fabric and textiles. Sustainability in the fashion industry depends on innovations in these fields, such as creating eco-friendly textiles and low-impact dyeing methods [26].

Thus, the interaction between technology and sustainable fashion demonstrates a mutually beneficial relationship. Positive change is possible with a modest but effective “democratic globalisation” of technology. This concept is a term for the application of technology that globalised the common depoliticisation of technology and the use of digital technology to promote social progress in a more equitable, just, and effective way through widespread public participation, such as promoting sustainable fashion [25]. Although attempts have been made in various sustainable fashion-related sectors, further study is urgently required in fashion presentation. Narrative consistency in sustainable fashion communication remains inconsistent, with fragmented language usage and interchangeable phrases across different contexts [27]. In explicating and deliberating on sustainable fashion, individuals may utilise incongruous language or discourse, creating confusion or uncertainty in conveying information [28]. Despite this linguistic challenge, sustainable fashion fulfils the ethical shopping desires of fashion-conscious consumers, aiding them in building their identities through mindful purchases. Consumer trust in the fashion industry and its dedication to durable, environmentally friendly design drive growth in sustainable fashion [29]. However, along with improvements in materials and technology, current research mainly examines customers’ intentions to use and buy sustainable clothing, with little focus on underlying motives. Additionally, there is a dearth of thorough research on the issues preventing the broad use of sustainable fashion and the remedies that can be employed [3]. Leal et al. [30] suggest the implementation of carbon budgets for customers to alleviate environmental issues associated with the consumption of fashion, particularly considering the rising popularity of virtual style and digital tools. This notion is still in its infancy and has not been tested or implemented. Sustainable fashion focuses on the design, manufacturing, and consumption chains while addressing social and environmental sustainability. Addressing environmental issues should also consider the substantial wastewater produced during the textile production process, in addition to consumption. Significant wastewater, frequently containing dangerous chemicals, is produced during the fibre manufacturing, dyeing, and fabric processing stages. This underscores the necessity of more stringent wastewater management regulations, sustainable production methods, and consumer-focused programs [31].

Therefore, it is critical to perform additional research to understand consumer motivations and behaviours in greater detail and to propose creative solutions to the challenges preventing the widespread adoption of sustainable fashion. Through study, this offers an ethical purchasing alternative that advances the industry in both the long-term pursuit of environmental and social responsibility and the pursuit of fashion [32]. Therefore, we can significantly contribute to achieving sustainable fashion and developing a sustainable fashion business by investigating and actively advocating these concerns and concepts. This research gives the fashion industry a more meaningful and environmentally conscious future. From fibre production to retail, the textile and fashion industry’s lengthy and intricate supply chain exacerbates environmental constraints due to resource consumption. Ecotoxicological concerns associated with the chemicals used in the production of textiles damage not only the environment but also consumers and industrial workers [33]. To improve the texture, colour, and functionality of textiles, textile finishing also includes the use of different chemicals, including water repellents, flame retardants, anti-static agents, wrinkle-resistant treatments, bleaching agents, mordants, and softening agents. However, these chemicals can leave residues on textiles, leading to environmental pollution and health risks like immune system suppression and an increased risk of cancer, especially when clothing is worn close to the skin. This emphasises the need for stronger laws and safer alternatives in the textile manufacturing industry [34]. Although most of these effects are felt in the countries that host textile and garment manufacturing, the problem of textile waste also exists worldwide [33]. For example, the only country in the world that has introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for used clothing, textiles, and footwear is France. Since 2006, the post-consumer textiles’ collection and recycling rate has tripled because of the EPR policy. Approximately 50% of these can be recycled. However, Africa is the most popular region for ‘reuse’, and many countries consider making imported used clothing illegal. However, the term “sacrifice zones” describes areas, frequently found in non-Western nations, that are routinely affected by the negative social and environmental effects of textile waste while developed countries dispose of their unwanted apparel. An aspect of environmental racism is reflected in this practice, which marginalises non-Western economies and clothing traditions while treating them as landfills for textile waste [35]. Overcoming this systemic inequality is necessary to create a fashion system that is both genuinely sustainable and equitable.

Therefore, while Fletcher [15] argues that ‘localism’ is a necessary strategy to move away from the globalised production of ‘monoculture’, she must also make recommendations to avoid potential parochialism. Furthermore, the close link between capitalism and the fashion industry indicates the importance of inequality and class dynamics [36]. Inequalities are experienced across several socioeconomic strata and geographical and developmental gaps, highlighting the complex character of inequality in this environment. While it is widely accepted that fast fashion has a detrimental impact on sustainability, most proposed solutions unfairly burden consumers, particularly those who are less wealthy and primarily younger generations, like college and high school age groups, instead of addressing the industry’s structurally unsustainable practices [37]. Guattari [38] shows the model highlights conflicts at the social, individual, and environmental levels, where sustainability initiatives in the fashion industry frequently unfairly target underprivileged and globalised communities while ignoring more significant issues like labour globalisation and global inequalities, globalised “democratic” fashion while blaming people with low incomes for their aspirations and consumption, and pushing a globalised and classist agenda that discriminates under the guise of “ethical fashion”. Fashion may increase discord between citizens when it is used to display wealth and status, but it can also advance democracy and spark democratic discourse on social and political issues when it is used to show respect, loyalty, or group affiliation [39]. More than just maintaining social structures under the guise of necessity is required for sustainable fashion. It calls for an acceptance of the inconsistencies of luxury producers, an end to the systematic reprimanding of less wealthy desires, and a focus on building democratic, dynamic, and vigorous ideals inside the industry—all while remaining within Earth’s ecological bounds [40]. To fix inequalities, Williams [41] outlines two different approaches that are promoted for sustainability. The first approach places a higher priority on the environment while working to build economic development. In the second method, economics is given greater importance, and nature is mostly viewed from a financial standpoint. These two methods are also evident in academic studies, where one looks at fashion through the prism of economic systems while the other adopts a more comprehensive approach that considers natural cycles. Especially reducing global risk, expanding responsibility, and maintaining the health of the seventh-largest sector of the global economy—as demonstrated in the introduction—are notable common goals shared by these methods. The fashion sector, as a major participant in this field, is crucial in determining the sustainable landscape. We may effortlessly navigate the challenging landscape of sustainable practices in the fashion sector if we are aware of these many routes and their ramifications. The fashion industry tries to maintain democratic principles; nevertheless, in certain cases, its search for sustainability can mask rather than solve social injustice and systematic inequity. This unexpected outcome has the potential to undermine social tensions inside the sector. Due to the strengthening of environmental regulations in Western consumer cultures, one significant consequence of this endeavour is the transfer of polluting industry processes to colonial countries. It is interesting to note that different nations and areas have different perspectives on pollution, influencing how they recycle and reuse materials. According to Brooks [42], developing countries are often more receptive to these techniques. Fashion is a medium that frequently reflects the social mores and values of a specific age since it plays a significant part in the expression and representation of culture, which in turn acknowledges cultural diversity and inventiveness [43]. Fashion extends to the idea that fashion and style can act as the foundation of a democratic movement, providing a means for individual and group self-expression. The clothes we wear can be indicative of democratic principles, as they are evidence of the choices we make in our daily lives and how we choose to present ourselves to the world [44]. However, it can be incorrect to assume that all aspects of “fast fashion”, a word used to represent inexpensive apparel’s quick manufacture and consumption, are inherently evil. Fast fashion undoubtedly presents specific ethical and environmental concerns, but it is also vital to recognise that for many individuals, cost and accessibility are important considerations when choosing apparel [45]. In addition to fast fashion, “knock-offs” is a related idea that merits discussion. Knockoffs are less expensive replicas of fashion items that are frequently made using inferior fabrics, little attention to construction details, and cost-cutting techniques like using less material when cutting garments. Although knockoffs are more affordable, they worsen the fashion industry’s sustainability and quality problems [34]. Considering this, Miller’s democratic fashion tenets, which promote a slow fashion strategy that globalises quality, sustainability, and ethical production, may unintentionally marginalise people who depend on quick fashion because of financial constraints. We risk oversimplifying a complicated problem and failing to meet the demands of all groups in our society if we reject fast fashion as a whole [44]. According to Von Busch [40], when we concentrate too much on the issues in fast fashion, we risk overlooking the democratic value of solidarity. More research is required to fully comprehend the complex nature of fashion, as it is not only a means of consumption but can also be an effective means of promoting concepts of democracy and social solidarity. He suggests that to realise the democratic potential of fashion fully, we should first promote sustainable practices rather than just selling sustainable products. Although this is a significant and legitimate point, before moving on to the production of clothing, attention must be directed towards the textile manufacturing process, which includes the fibre production, dyeing, and finishing steps. Second, we could encourage creative thinking while adhering to democratic principles. Lastly, the focus may shift from merely fashion accessories to the more important social dynamics and involvement of the industry. The replacement of lust, greed, and vanity with virtues like truthfulness, honesty, and the desire for a better life through the modification and dissemination of the correct intrinsic values to promote social sustainability and a shift in the consumption culture is known as sustainable development in spiritual ecology. Implementing educational programs within the educational system, starting at the elementary level, is crucial to achieving this transformation. Early environmental education will help instill sustainable values in children’s daily lives, promoting long-term ecological awareness and conscientious consumption [46,47]. Therefore, the thesis of sustainable fashion is examined in further detail in this research. Sustainable fashion’s objectives need to be clarified—including democratic principles and increased social mobility while achieving sustainability [47]. Universal “sustainable” behaviours resemble a repackaging of opulent standards under the guise of environmental responsibility and sustainable growth. Making sure that these sustainable practices are accessible and cost-effective rather than just a luxury alternative is the problem [40]. In addition, the ‘fashion paradox’ is a claim made by Maynard [48] that fashion and sustainability are fundamentally contradictory. Despite this paradox, Korean fashion buyers have shown a keen interest in the sector, according to Moon et al. [3]. According to Rakuten Insight, awareness of the term ‘sustainable fashion’ is notably high among Japanese adults aged 30 to 39, with teenagers aged 15 to 19 demonstrating the most comprehensive understanding of the concept. This growing recognition reflects the younger generation’s alignment with green values and their potential to drive sustainable practices in the fashion industry [49]. They are enthusiastic about fashion but also concerned about environmental preservation issues. In conclusion, the fashion clothing industry’s dominant approach frequently imitates luxury standards, which might result in exclusion and elitism. This is evident even though social mobility and principles of democracy are intrinsically encouraged by sustainable fashion. To develop true sustainability amid the paradoxes of style, it is necessary to ensure sustainable practices are available and affordable. It can be envisaged that this approach to sustainability will also help to reconcile the interests of fashion-conscious customers with environmental preservation. Global concerns that have had a substantial impact on manufacturers and consumers alike, like the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing global inflation crisis, should also be considered in this study. In addition to upending production and supply chains in the fashion sector, these factors have changed consumer behaviour, making accessibility and affordability even more important in the context of sustainable fashion practices.

3.1.2. Material Innovation

The fashion industry, notorious for its environmental impact, is exploring sustainable raw materials and production methods to minimise pollution [50]. Current research targets organic materials from diverse natural sources, including animals, plants, and microorganisms, as potentially sustainable solutions [50]. Although conventional textiles like silk, cotton, and wool are still in demand, nowadays, synthetic, artificial fibres are used to make a large percentage of modern clothing. Through processes like polymerisation, these fibres—which include polyester; nylon; and elastane—are made from chemical compounds and polymers; allowing materials that can replicate the texture and appearance of natural fibres to be mass-produced. To increase durability and cost-effectiveness, artificial fibres are frequently mixed with natural fibres; however, the production and disposal of these materials present serious environmental issues, including microplastic pollution and dependence on petrochemicals [51]. To promote sustainability in the fashion industry, these issues must be resolved. Although these textiles are often considered ecologically sustainable, their high demand for energy, land, and water does have a negative, often permanent, impact on the environment [52]. Bacteria use a growing medium like black tea and sugar to produce bacterial cellulose (BC), an “alternative” fabric. This open and transparent procedure encourages investigating BCs sustainability and prospective applications [32]. To produce an eco-friendly material with simple production processes, efforts are made to resolve problems with bacterial cellulose in sustainable fashion research [53]. The Dumbara weaving process in Sri Lanka, a centuries-old craft that involves intricate hand-weaving patterns using cotton and hemp, has benefitted from improvements to traditional textile preparation techniques. These improvements have also reduced fabric waste and encouraged fashionable behaviour among authority figures. It also made it possible for designers to present a novel combination of design and craft to artisans [54]. In Kamble and Behera’s [55,56] study, textile waste generation, thorough classification, international fabric marketplaces, and the environmental effects of waste textiles were all investigated. Therefore, the challenges of controlling textile waste and using upcycling methods for used textiles are critically examined, and techniques for creating upcycled goods from used materials are investigated. According to their investigation, textile waste makes up a significant amount of the landfill accumulation worldwide, and inappropriate disposal and ineffective recycling systems greatly contribute to environmental degradation. The study also emphasised the increasing contribution of global fabric marketplaces to the reuse and redistribution of textiles, underscoring the necessity of international regulations to improve textile waste management and encourage the circular economy. Borstrock [56] discusses how they share a common understanding of materials and their applications, the environmental impact of materials, and conscious efforts to reduce waste, embrace sustainable habits, and improve the customer experience through the first material from the workpiece. Moreover, Joshi and Chowdhury’s [57] products use the least amount of textile waste while providing high usage and enjoyment. This relates to the globalisation of modern materials. Next, Costa and Broega [37] suggest creating biodegradable buttons from leftover food. The research conducted by Minh and Ngan [58] sheds light on the various facets of vegan clothing in the fashion business. First and foremost, wearing vegan clothing is regarded as a powerful endorsement of animal rights and a monument to moral values. It is crucial to remember, though, that some detractors contend that vegan leather cannot simply be substituted for conventional leather. They draw attention to the fact that the manufacture of vegan leather can be wasteful and may not fully adhere to sustainable practices. For example, MycoWorks, a California-based biotechnology company, has been at the forefront of developing sustainable alternatives to traditional leather. The company is expected to make major strides in the development of innovative biomaterials in the years to come. Sun et al. [59] aim to promote biodegradable “alternative leather” materials, environmentally friendly colourants, and environmentally friendly replacements for fibres derived from animals and virgin cotton fabrics. They also use environmentally friendly chemical procedures to create multi-component textiles and bio-composite keratin hybrid textiles from recovered waste textiles. This plan seeks to perform two things: first, it will help reduce the excessive trash that the rapidly expanding fashion sector produces; second, it will offer a new source of nutritional fibre. This dietary fibre could help address the global food issue and lessen the manufacturing of chemical and organic fibres, which in turn causes a shortage of fossil fuel sources. To transform T-shirts into handbags to replace single-use plastic bags, Premkumar et al. [60] developed automated machines that might repair the bottoms of T-shirts, remove the sleeves, and widen the collar to turn used or unsaleable T-shirts into bags made of reusable fabric. Through this process, clothing that would otherwise end up in landfills is given a second chance at life, reducing textile waste. Most of the T-shirts used come from retailer’s unsold inventory, textile recycling initiatives, or post-consumer donations. Through this, they extend the fabric’s lifetime and reduce the wastage and damages caused by fast fashion, in addition to the impact on the environment of producing new cloth bags and replacing single-use plastic carrier bags in contemporary marketplaces. This project aims to demonstrate the importance of “Green Tags”, a term that refers to sustainable labelling systems or indicators that highlight environmentally friendly features of products, like lower emissions, less chemical use, or recycling advantages. Three main contributions of sustainable labelling were identified in the work of Bottani et al. [61] as a manufacturing process that primarily minimises chemical waste (up to 39% in this article), complete rejection of single-use plastics (100%), and a significant reduction in emissions of greenhouse gases (up to 61%). Moreover, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology allows for wireless communication and radio wave-based tracking and identification. RFID can be used to trace the flow of materials and clothing through the supply chain in the fashion industry context, which can enhance inventory control and lower waste. Furthermore, RFID can assist businesses in doing this, helping them show their dedication to sustainability and giving customers straightforward information about how their products affect the environment. In conclusion, RFID technology has the potential to enhance sustainability initiatives in the garment sector, but it is not a magic fix. Integrating RFID with other sustainable practices and certification programs is just one of the additional measures required to assist fashion companies in achieving their sustainability goals [62]. This section has examined the efforts made by the fashion industry to adopt sustainable raw materials and manufacturing methods, including natural materials and innovative biomaterials, to reduce environmental impacts. It examined the strategies employed in reducing waste, repurposing, and the potential of tracking technologies (e.g., RFID) in enhancing sustainability practices in the fashion industry.

3.1.3. Design Practices

Zero-waste design is a sustainable strategy for the fashion industry’s production process to reduce or eliminate fabric waste produced throughout the design and manufacturing processes. It combines the duties of pattern makers and designers to create clothing with a thorough method that considers both beauty and utility [63]. Besides, the fashion sector can benefit in many ways from zero-waste design. First, it can lessen the environmental effect of clothing manufacturing by reducing fabric waste and the consumption of resources like water and energy. Maximising the use of fabric and doing away with the need to dispose of fabric remnants can also save production costs. Lastly, encouraging designers to look beyond conventional pattern-making techniques can foster originality and innovation in design. Ultimately, zero-waste design is a sustainable approach to the fashion industry’s production process that benefits both the environment and the sector. It takes a comprehensive process incorporating designers and pattern makers to ensure that aesthetics and functionality are considered while minimising waste [64]. Significantly, Gwilt and Rissanen [65] suggest four methods for designing no-waste clothing: element or puzzle, indented puzzles, and multi-fabric approaches. Eventually, Carrico and Kim [63] offer an additional “design practice” known as “minimal cutting” that involves using the least possible cut to wrap a whole piece of material. Discovering a feasible technique to generate grading systems for various sizes and reducing extra fabric in clothing are difficulties that still need to be solved, even though many designers and fashion brands are constantly trying to generate zero-waste products. Indeed, Rahman and Gong [66] conducted a mixture of zero textile refuse and non-rigid garments and demonstrated how this tactic could boost the variety of garment fashions, increase the entire and productive life of clothing, avoid excessive waste and fabric waste, and provide clean energy solutions that promote sustainability over time. Such measures and combinations may also lead to a rise in customer satisfaction. Designing zero-waste clothes is a challenging but gratifying design task that demands attention to form and function. The deliberate use of excess fabric to minimise waste in certain zero-waste designs has drawn criticism [63]. Opponents contend that even while the primary objective is to reduce waste, this strategy may nevertheless lead to inefficiencies or excessive material use during the design phase. They stress that to attain zero-waste fashion, a more accurate and effective use of resources is required. Computer-Aided Design (CAD) systems have long been used in the fashion industry to reduce fabric waste during the cutting and design stages. By creating accurate patterns, cutting down on extra fabric, and expediting production processes, CAD technology maximises material utilisation.

Cultural sustainability is a response to society’s shifting attitudes towards inclusivity, representation, and respect for others and their cultural heritage, as well as the awareness and preservation of cultural variety [67]. The conservation and development of cultural practices, material culture, and craft to transmit culture entails understanding past biases and attempting to resolve them [68]. Moreover, acknowledging and preserving cultural variety, inclusivity, representation, and respect for people and their cultural history are responses to cultural sustainability. It encourages preserving cultural practices and material culture to maintain cultural diversity and identity. It also acknowledges the significance of craft as a form of cultural transmission [69]. Therefore, this value shift goes beyond innovation in design methodologies. Designers such as Stella Jean, an Italian fashion designer of diverse ethnic backgrounds, and Swati Kalsi aim to relieve hardship and advance innovation through the dignity of work by connecting artisanal groups and promoting cross-cultural engagement. Stella Jean, for example, has created a sustainability platform to assist relationships with craft groups, each of which is a type of cultural exchange and” permission to appropriate”. Indian fashion designer Swati Kalsi embodies the country’s distinctive cultural history. That pushes limits and encourages female artisans to be painters and makers, redefining tradition [68]. Following the Japanese custom of making clothing from handmade paper, Mohajer va Pesaran’s [70] research focuses on using handmade paper clothing in sustainable design. They investigate this technique by critically analysing modernity’s dynamics, problems, and ideas of place and rootlessness. According to the researchers, using handmade paper clothing in sustainable design shows a regionalist perspective that globalises the value of regional customs, traditions, and culture. The dominant multinational fashion industry, they contend, frequently puts profit above sustainability and cultural preservation, whereas this strategy contrasts it. The scholars emphasise that globalisation capitalism has played a role in the deterioration of traditional behaviours and cultures through their critical assessment of the dynamics of modernity [71]. They contend that a “species of placelessness and rootlessness”, in which production and consumption are cut off from the local contexts in which they take place, characterises the worldwide fashion industry [72]. On the other hand, handmade paper clothing is a return to regional customs and traditions in a sustainable fashion. This strategy strongly emphasises the value of a feeling of place, cultural identity, and the protection of regional ecosystems and resources. The materials used in this approach are often sourced sustainably, such as from responsibly managed forests for natural fibres like cotton, hemp, or linen, and alternative plant-based materials that do not require deforestation. Many designers prioritise the use of recycled or upcycled resources to ensure minimal environmental impact while supporting local ecosystems and artisanal practices [73]. Overall, Mohajer va Pesaran’s [70] research on globalisation shows the value of regionalist perspectives in sustainable fashion research, the contribution of traditional practices and cultures to sustainability, and the preservation of cultural variety. They offer a critical viewpoint on modernity’s dynamics and the problems with the international fashion industry through their analysis of the use of handmade paper garments in a sustainable fashion. This section emphasised the importance of zero-emission design, societal durability, and creative representation in environmentally conscious clothing. This promotes the reduction of waste, preservation of cultural heritage, and awareness of the environment, resulting in a comprehensive approach to sustainable fashion that combines aesthetics and functionality. As the fashion industry progresses, it becomes essential to align education with the dynamics of the industry to produce significant contributions to sustainability.

3.1.4. The Evolution and Impact of Fashion Shows

While still a part of the fashion business, fashion shows have moved beyond their initial economic function as launch parties for a few luxury firms’ most recent collections. They have evolved into highly symbolic public spectacles, captivating visual feasts that seize audience interest. This scholarly analysis calls for a more significant viewpoint that sees fashion shows as crucial cultural occurrences inside the fashion system rather than just as commercial venues [74].

- The Historical Development of Fashion Shows

At first, a minority approach employed young women as live models, but the most common method for showcasing fashion was using mannequins. The novelty in fashion was mostly caused by variations in fabric rather than original designs [75]. Before that, the British designer Charles Frederick Worth and his business partner opened the Gagelin silk clothes store in Paris in 1854. His approach, which included showcasing designs using live models, demonstrated bold creativity, fundamentally altering the power dynamics between clothing designers and their clientele [74]. Then, in 1901, Lady Duff Gordon established a studio in London using her expertise as a theatrical costume designer to stage spectacular live model parades while fully globalising the aspects of the performing arts. That marked an early fusion of creativity and commerce by combining fashion and performance art. Parisian fashion designers first opposed [76] this novel format but quickly started to imitate it [75].

- Modern Fashion Shows as Platforms for Social and Political Activism

Fashion shows have evolved beyond commerce to serve as platforms for activism and political expression, bringing attention to pressing global issues. For example, designers like Vivienne Westwood have used their runways to advocate for environmental causes [76], while brands like Dior and Pyer Moss have showcased collections addressing feminism and Black cultural identity. Such examples highlight how fashion shows reflect the ideologies of designers and leverage their global visibility to raise awareness for social and environmental challenges [77].

While fashion shows in the era of haute couture had the potential to become iconic market elements, their development was hindered by the small affluent consumer market and intellectual property constraints. While department store fashion shows faced fewer restrictions, they lacked the media allure for iconisation. All of this changed with the start of World War II, which upset Paris’s dominance in fashion and established New York’s Press Week showcase in 1943 [78,79]. However, since American law provides minimal protection for designers’ intellectual property rights, their main motivation for seeking was to stop others from copying their work without permission [80].

- The Knock-off Phenomenon

As American designers used shows to gain recognition, the problem of knockoffs—cheap copies of runway designs—started to surface; endangering the industry’s originality and inventiveness [81]. Furthermore, these partnerships proceeded to take the same approach as the French market. After Pierre Cardin left Printemps’ women’s ready-to-wear division in 1959, more designers experimented with fashion shows, laying the groundwork for a ready-to-wear fashion week to follow Haute Couture Fashion Week [79]. In addition, because many self-taught designers made London the centre of fashion starting in the 1960s, London’s many subcultures, the rise of many young people, and street culture threatened haute couture. When Mary Quant, for instance, showed dozens of outfits in 15 min, she altered the rituals and rhythms of the catwalk [82]. Then, as technology advanced, fashion grew more widespread, well-liked, and diverse; the catwalk replaced advertisements and other forms of industry communication; models took on more prominent roles; and the supermodel era began. With the rise of social media, catwalks became more and more geared towards being viewed online on a digital screen, creating opportunities for bloggers and social media influencers. Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) companies also experimented with the “see and buy” model. These FMCG “see and buy” approaches have compressed the time between fashion marketing and consumer purchase [75].

- The Emergence of Sustainability and Innovative Practices

Fashion design in modern society deals with wearability and planning for the senses. Expanding the boundaries of clothing appreciation, Jean Paul Gaultier’s “Bread Clothing Series” and the chocolate garments at the New York Chocolate Show highlighted fashion design’s innovative nature, evoked not only visual imagery but also gustatory and olfactory experiences, and all at once, viewed fashion design as a distinct genre of creative design, reaffirming its importance in the field of contemporary product design [83]. Fashion shows now include sustainability practices in addition to improving the sensory experience. To lessen their impact on the environment, designers are increasingly “reusing fashion space”—that is; repurposing existing spaces; such as historic buildings or abandoned warehouses [84]. In addition to showcasing creativity, these initiatives also show how the sector is becoming more conscious of sustainable development objectives. Furthermore, by actively promoting inclusivity and diversity, programmes such as Vancouver Indigenous Design Week (VIFW) give models from mentorship programmes for young Aboriginal women a stage, which further advances the field’s continuous evolution [85]. In summary, fashion shows have evolved from being merely industry gatherings to becoming venues that integrate sustainability, innovation, and cultural expression. They keep developing by embracing technological innovations, environmental awareness, and inclusivity, influencing fashion’s future as an art form and a force for good.

3.1.5. Virtual Fashion Trends

The media has recently referred to “digital fashion” as a recent significant development in the fashion sector. Besides, the possibility of digitising conventional fashion design processes and virtualising fashion pictures, industries, and locations has emerged because of recent advancements in clothing and accessories and 3D software. Furthermore, a more extensive digitisation process known as “Fashion 4.0” includes the growing usage of 3D software in the fashion design process. A new generation of designers is being influenced by the ethical, financial, and artistic debates in the fashion market to explore alternative ways of providing clothing and fashion, minimising wastage of resources, and starting to move toward conducting experiments with application services, production techniques, and innovations [18]. Nowadays, scanners, quaternions, and 3D template tools are among the new tech used in the fashion business to enable consumers to customise clothing at a reasonable price. With new technology, consumers might participate in the design process as co-designers, which could have long-lasting effects on the cost of the article and how it is worn [86]. Furthermore, marketers may now analyse client behaviour trends and generate more complex information designs thanks to breakthroughs in artificial intelligence. Information design may not always be a novel idea in relation to other elements of design thinking, but it is a crucial step in this process [87]. The focus of information design activities has changed in recent years from resolving delivery technology issues to integrating solutions that directly match production with customer demand. In the fashion industry, for example, businesses have embraced made-to-order or on-demand manufacturing models, in which clothing is only manufactured in response to a customer’s order. In contrast to traditional mass production, this method more successfully addresses business concerns while lowering waste and unsold inventory [88].

Simultaneously, recent advancements in sewing robotics have the potential to displace traditional factory labour and textile production techniques in several well-established industrial applications that are focused on creating uniform apparel [89]. As such, clients are about to enter a new phase in which they may make use of the Tailor digital branding application, which is easily accessible on their iPhones. With the help of this programme, they can scan their bodies, specify how they want their clothes to fit, and personalise little elements like shirt collars before completing a purchase [89]. In summary, the findings of the research highlight the new possibilities for virtualisation and simulation throughout the fancy dress creation stage. This emphasises how important it is to teach and model accuracy to guarantee that these cutting-edge technologies are implemented successfully. Costume design and production for the performing arts is a highly collaborative process that involves numerous people in various roles and responsibilities. While directors give direction on how the costumes should enhance the performers and storytelling, costume designers oversee the creation of the overall concept and visual style for the costumes. The designs are subsequently brought to life by costume designers using patterns, fabric selection, and stitching [90]. Until now, the conventional collaborative method is changing as digital technologies are increasingly used in costume design and fabrication. Before physically making costumes, designers and artisans can experiment with, test, and improve them using digital tools and techniques, including 3D modelling, digital printing, and motion capture. This facilitates increased design freedom and precision while also accelerating the production process. Also, the globalisation of digital technologies creates new opportunities for integrating technology into performance and costume design. For instance, clothing with built-in sensors and lighting can react to the performers’ gestures and motions to produce dynamic and engaging shows. In conclusion, digital costume design and production technologies alter the conventional collaborative process by enabling designers and manufacturers to build a virtual environment and put technology into the costumes. These advances are creating new avenues for theatrical storytelling and artistic expression. However, digital technology has limitations, and current 3D software was created from a technical perspective and uses terminology that most fashion designers need to familiarise themselves with. Because of this, designers and manufacturers generally acknowledge that there are certain software constraints. The network of creators highlights the necessity for students to have easier access to new technologies to acquire the globalisation information that future designers will need. Future makers must enlist conventional construction collaborators as educators and experiment with novel ways of thinking to apply new technology [91]. Eight apparel design students have already started using the Human Solution Vitus XXL 3D body scanner to develop their avatars and integrate synthetic human body models into the Optitex system for digital garment-making. However, users view a brief film as part of their present clothing design, manufacture, use, and disposal methods as one approach to reducing environmental impact. This opens new possibilities for future studies, such as examining the patterns of interaction of various groups of users [86]. It is also important to note that some people argue that three-dimensional Virtual Reality technology and digital apparel may have a big influence on how fashion is shaped in the future. But in addition to the digital revolution in design, production, marketing, and consumption, it is critical to take into account the environmental sustainability elements of these developments [92]. Digital Fashion is a novel development cluster in the fashion sector encompassing three-dimensional software, adaptable digital design, virtual fashion displays, and intelligent manufacturing. This digital fashion upheaval has engendered noteworthy transformations in the approach to fashion that is contrived, fabricated, and consumed, mainly through digital technologies that enable consumers to partake in the fashion design procedure. While digital fashion harbours considerable potential, it also has impediments regarding technology and the milieu.

3.2. Impact and Sustainable Practice

Impact and sustainability are globalised according to four factors: (i) consumer behaviour, (ii) circular economy, (iii) life cycle calculations, and (iv) corporate responsibility for cooperation.

3.2.1. Consumer Behavior

According to Lou and Cao’s [93] research, consumer preferences are present at all stages of the apparel’s lifetime, including the end of the material, production, and use. Additionally, customer willingness to pay more for sustainability solutions in the apparel sector differs from what the industry believes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly raised awareness of ethical and ecological concerns in garment manufacturing and consumption [94]. The pandemic has exacerbated this shift in consumer consciousness, especially among younger demographics in the UK. More and more young people are participating in political campaigns and initiatives that address environmental and social concerns [95]. Additionally, because many physical stores were forced to close and switch to selling online, COVID-19 accelerated the growth of online shopping, especially in the fashion industry [96]. As a result, there is now more focus on sustainability and ethical fashion consumption, which has changed both the retail environment and consumer habits. For instance, the Extinction Rebellion Fashion Initiative has urged the British Fashion Council to postpone London Fashion Week and hold urgent discussions to address the fashion industry’s role in the climate and environmental catastrophe since 2019 [97]. The need for social media researchers to comprehend consumer decision-making processes and attitudes towards the sustainable fashion industry, particularly in East Asian nations like South Korea, China, and Japan, is highlighted by cross-cultural differences in consumer attitudes and internet word-of-mouth intentions towards sustainable fashion products (SFPs) [98,99]. The varying results among countries with comparable cultural backgrounds point to the need for a variety of marketing approaches. Depending on the particulars and demands of each market, these tactics may be used to increase fashion sales or advance sustainability in the fashion sector, among other goals. Chinese customers are increasingly informed, engaged in environmental issues, and driven to make moral purchasing decisions. When making decisions, Korean customers typically steer clear of risk and ambiguity. Consumers in Japan and Korea share a negative perception of perceived dangers. Benefits to their health are preferred [99]. The main reasons why fashion consumers are hesitant to use sustainability as a set of criteria for purchasing fashion products include a need for more awareness of sustainable concepts, sustainable fashion items, and usage, and an inadequate capacity to obtain and digest sustainable development information. Consumers may be considered individuals who continue the circulation of materials to increase the life of clothing and reduce waste, leading to the circular economy being viewed as a response to the flow of material. In many ways, “refusing” to consume goes against traditional economic wisdom and is at odds with the steady economic growth that is a hallmark of the prevalent linear economic approach. Although customers might forego purchases or cut back overall, this impacts the economy. As a result, consumers’ influence and interactions with products are significant [100]. On social media, there is a growing movement of “de-influencers” who are challenging the conventional influencer paradigm of promoting excess and consumerism. Traditional influencers may advocate consumption to boost one’s reputation and position. De-influencers encourage a new generation to adopt a more sustainable and rewarding way of life by encouraging thoughtful consumption and disputing the idea that material goods imply pleasure and success. In general, the emergence of influencers heralds a profound change in social media culture and how we view consumption. De-influencers give a novel and exciting viewpoint on how we might make more meaningful and sustainable decisions in our daily lives as consumers become more aware of the social and environmental effects of their choices [101]. Conclusively, the emergence of ‘de-influencers’ presents a novel outlook on how we might make more purposeful and sustainable decisions in our everyday lives, even while influencers persist in moulding social media tradition. When customers grow more conscious of the social and environmental effects of their choices, this change becomes more and more important. Additionally, customer interaction, online environments, and product presentation are all factors that can influence consumer shopping behaviours and experiences [102]. The impact of social media and influencer marketing on consumer loyalty and purchasing intentions is also significant, but transparency is critical in building trust and word-of-mouth recommendations [103,104,105]. In addition, theories about identity, social influence, trade-offs between features, and personal moral convictions—all of which have been discussed—further highlight the complexity of consumer psychology and the variety of factors that companies need to take into account when creating marketing plans and products. The field of consumer psychology offers valuable insights that can be applied to marketing strategies for sustainable clothing companies. These strategies should consider demographic factors such as age, culture, and psychological models to better understand and influence consumer behaviour [106]. Statistical techniques can also examine how different designer experience levels and consumer image kinds affect consumer demand [107]. Understanding the aesthetic preferences of consumers for everyday wear, iconic wear, and daily wear can provide insight into creative agreement and presence [107]. Consumer segmentation is crucial for marketing sustainable fashion. Kaner and Baruh [108] identified four distinct buyer images that could be used for consumer segmentation, communication, and marketing: romance idealist, egoistic, confused Alex, and pessimistic. By tailoring marketing efforts to these different consumer segments, sustainable fashion companies can increase awareness and encourage sustainability-related behaviours in the fashion industry. Blockchain technology has the potential to provide customers with unparalleled items’ environmental impact, fair labour standards, ethical sourcing, and material origins. Customers may also actively engage with this technology by utilising websites or applications to confirm the legitimacy of the product and obtain comprehensive details about the garment’s production process [109]. In essence, blockchain technology creates a business model that is more transparent, ecologically sustainable, and in line with consumer values by bridging the gap between ethics, technology, and fashion. Overall, incorporating consumer psychology and technology insights can lead to more effective and sustainable marketing strategies for the fashion industry. However, further research is needed to fully understand the complex relationships between consumer behaviour, psychological factors, and sustainability in fashion.

3.2.2. Circular Economy

The Circular Economy (CE) model and its components seek to minimise waste and maximise resource efficiency by promoting the reuse and recycling of materials in production processes. In the fashion industry, this means adopting practices such as using recycled materials, designing recyclable products, and implementing closed-loop systems for textile production. Adopting circular practices in fashion production is often driven by life cycle thinking, industrial ecology, and Cradle-to-Cradle design principles, which aim to minimise environmental impact and optimise resource use (EE) [100]. According to Coscieme et al. [110], transforming the fashion industry towards a more circular and sustainable model requires innovation in business models, technology, and social practices. This can be facilitated by specific drivers such as policy creation, education, and behaviour change. However, one challenge remains that consumers often need help determining whether products are made sustainably. As a result, research and information that helps to clarify the market landscape and demonstrate the benefits of circular practices are essential from a market dynamics perspective. Developing and testing ideas that make fashion’s “sustainable hierarchy” more accessible to communicate to customers is crucial to addressing this challenge. This involves identifying clear categories of sustainable practices (such as closed-loop systems, sustainable materials, and ethical production) and developing effective ways to communicate this information to consumers [111]. Universities often include general drivers of sustainable practices, such as circular economy (CE) strategies, in their management and communications courses. The WRAP UK research also includes initiatives for garment maintenance and repair. It highlights the need for collaborative action by businesses, individuals, governments, and NGOs in addressing fashion sustainability issues through CE techniques [100]. Additionally, brand-new technologies are currently being developed that might provide some solutions, with blockchain, intelligent tagging, and irreplaceable tokens (NFTs) demonstrating some of the most promising ones [112] For instance, digital marking and tracking technologies can reveal information about recycling centres at the end of their life cycle and information downstream in the supply chain. Radio frequency identifiers (RFID), rapid response (QR) codes, beacon technologies, near-field communication (NFC), computer chips, and other Internet of Things (IoT) gadgets, in addition to artificial intelligence, are examples of tracking devices (AI). The manufacturer can follow fibres to produce clothing, distribution, sales, and resale. Several procedures in the supply chain can result in the loss of tracking capability; if carried out correctly, blockchain can capture and reduce this capability. Even small-scale companies and beginners can deploy technologies related to blockchain in the future by using off-the-shelf tracking tools like these [113]. Blockchain’s additional layer offers data protection and confirmation. However, many people in the fashion sector still need to practice using these technologies [97]. A framework for organising and advancing the adoption and growth of CE models is proposed by Coscieme et al. [110]. This comprises access projections based on renting, leasing, and sharing; collecting and resale of clothing; strategies with product durability; and recycling and reuse of resources. We discuss enablers based on social and technological innovation and policy, behaviour change, and education for each business model type. In the fashion sector, new technologies such as blockchain, intelligent tagging, and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are showing promise as solutions [112]. These technologies allow digital monitoring and data exchange across the supply chain, from manufacture to distribution and resale. Examples of these technologies include radio frequency identification (RFID), QR codes, beacon technology, near-field communication (NFC), Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and artificial intelligence. Specifically, blockchain can support the preservation of tracking capabilities and improve data security [113]. Using readily available tracking tools, blockchain technology may be utilised by small firms as well. This extra blockchain layer provides data validation and safety. To properly utilise new technologies, many experts in the fashion industry still have a learning curve to climb [97]. A framework has been presented by Coscieme et al. [110] to aid in the fashion industry’s acceptance and expansion of circular economic models. This framework covers several topics, such as methods for product durability, clothing collecting and resale, recycling and reuse of resources, and access models centred around leasing, renting, and sharing. We also go over elements that might hasten the adoption of different models, such as new developments in technology, modifications to laws and regulations, adjustments to behaviour, and educational programmes tailored to each business model. In conclusion, innovation and sustainable practices are essential to the fashion industry’s transition to a Circular Economy model. Innovative technologies that can improve data security and transparency across the supply chain include blockchain and intelligent tagging. For the fashion industry to successfully transition to a more sustainable and circular one, cooperation and education are essential.

3.2.3. Life Cycle Assessment

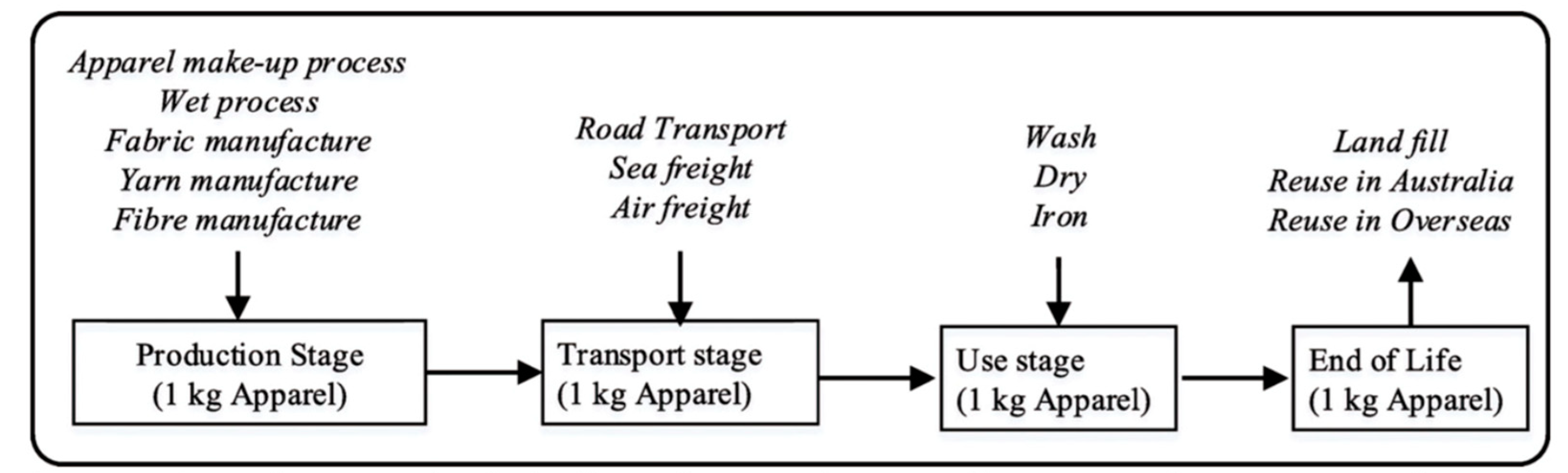

A product, process, or activity’s environmental effects are evaluated at every stage of its life cycle, from raw material extraction to processing, transportation, usage, and disposal, using a method named life cycle assessment (LCA). It may be implemented in a variety of ways, from the use of intricate data-intensive models to a straightforward matrix technique. Life-cycle assessment has advanced to the point that it can be utilised as an environmental management tool, even if there are still certain methodological problems to be fixed [114]. A product or process’s environmental impact must be evaluated using predetermined guidelines and standards. A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) involves the following four processes, per the ISO 14040:2006 standard: The first four steps are: (1) defining the objective and scope; (2) analysing the life cycle inventory (LCI); (3) assessing the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA); and (4) interpreting the life cycle [115]. A garment product’s life cycle may often be broken down into four main phases (see Figure 2): manufacture, transit, usage, and end-of-life [116]. Comprehensive data on inputs (such as water, energy, chemicals, and raw materials) and outputs (such as emissions to air, land, and water) at each stage of a garment’s life cycle are necessary to determine how to limit environmental consequences. Life cycle inventory (LCI) data are what this is called [115]. While LCI data has been supplied by several relevant LCA studies for the fashion industry, most of these studies have concentrated on one or a small number of product types and/or one or more aspects of the product life cycle [117]. In the life cycle analysis, “1 kg” of clothing is used to standardise the measurement and make it simpler to compare the environmental impacts at different stages. The life cycle analysis can offer a consistent benchmark for calculating the environmental impact (including carbon emissions, energy use, and water consumption) at each stage by concentrating on 1 kg of clothing. Because the environmental effects of various clothing types can differ and a fixed weight makes comparisons more consistent, this method streamlines the analysis [116].

Figure 2.

Complete supply chain flow diagram from cradle to grave [116].

As we get past the technical components of life cycle assessment, we should emphasise the usefulness of these approaches and their vital role in resolving environmental issues in the fashion sector. To lower environmental expenses, Moazzem et al. [116] highlight the critical role of the consumer usage phase and stress the significance of prolonging the lifespan of clothes and encouraging the recycling of old garments. Munasinghe et al. [117] also emphasise the need for more studies to fully evaluate the environmental effects of novel materials like smart textiles, particularly in fields where environmental data are still lacking, such as the military, healthcare, sports, and fitness. Industry standards are also necessary to improve the comparability of research since various brands frequently follow different washing standards, which makes it difficult to assess the impacts precisely during the consumer usage stage. Moreover, Gray et al. [118] study provides potential solutions to lessen environmental impacts by suggesting that the adoption of various business models, such as Product Service Systems (PSS), Collaborative Consumption (CC), and the Circular Economy (CE), can theoretically lessen the burden of apparel consumption on the natural and human environment. SDG 12: “Responsible consumption and production” highlights the need for businesses, especially small and micro-enterprises, to actively participate in innovative approaches to meet the demand for apparel. These approaches will enable a wider range of consumers to be served, promote a longer lifespan for apparel, and offer sustainable product choices. In summary, the environmental effects of fashion products are evaluated throughout their life cycle using the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology. LCA must conform to standards and guidelines, which include establishing goals and parameters, examining inventories, evaluating effects, and interpreting findings. LCA can be applied in the fashion industry to lessen its negative effects on the environment, increase the lifespan of clothing, encourage sustainable decisions, and offer solutions like product-service systems, cooperative consumption, and the circular economy. Research comparability is enhanced by industry standards. To put it simply, LCA is essential to the fashion industry and helps to realise the SDGs.

3.2.4. Corporate Social Responsibility