Abstract

Consumers encounter significant psychological and social barriers that hinder their participation in ecological transitions. Green influencers (or Greenfluencers), through their communication style and perceived credibility, have the potential to increase consumer awareness and engagement with circular practices. Previous research has focused on green influencers’ role in eco-friendly purchases, but their impact on promoting circular economy behaviors is less studied. To address this gap, the present explorative study investigates how green influencers’ communication can shape consumers’ perceptions of the barriers to adopting circular economies. Using a single case study of the Italian Greenfluencer “@Eco.narratrice” (Elisa Nicoli), this paper examines how green content creators’ communication can address psychological and social obstacles that prevent consumers from embracing circular models in the Italian context. Our findings reveal a different impact of Greenfluencer communication effectiveness on consumer perceptions of circular economy adoption barriers. While Greenfluencer communication helps reduce barriers like knowledge gaps and psychological essentialism, it may also heighten concerns about switching costs, inertia, and cynicism. The findings contribute to the growing literature on green influencers, offering new insights into the broader effects of their communication on consumer engagement with circular economies. This research provides insights for marketing managers on leveraging Greenfluencers to promote circular business models. It also provides feedback for Greenfluencers to refine their communication strategies, helping them better address consumer perceptions of CE barriers, particularly in areas where their efforts may fail to achieve the desired impact.

1. Introduction

The ecological transition has prioritized the shift from linear to circular economy (CE) models, now central to many countries’ Sustainable Development Goals [1]. This shift addresses the urgent global waste issue, projected to increase by over 50% to 3.8 billion tons by 2050 [2]. Adopting a CE could reduce urban waste by over 4.5 billion tons annually. However, transitioning from a linear economy, based on resource extraction, transformation, and disposal [3], to a circular economy focused on reuse, reduce, repair, and recycle principles [4] remains highly complex. According to several authors, achieving this transformation requires a coordinated effort involving institutions, companies, and, most importantly, consumers, whose role is pivotal in adopting more conscious behaviors and lifestyles [5,6]. However, shifting consumer behavior toward sustainable consumption remains a significant challenge for businesses [7]. The Circularity Gap Report [8] reveals that while awareness and interest in the CE have grown rapidly in recent years, the actual adoption of CE models has declined, with levels estimated to have dropped by 21% in 2023 compared to 2018.

These data suggest that despite efforts to communicate the benefits of circular models, such initiatives often fail to engage consumers or address their concerns, a challenge further exacerbated by growing consumer awareness of greenwashing practices, which has significantly increased skepticism toward adopting sustainable consumption behaviors [9,10]. Therefore, understanding the role of communication in promoting the CE and its potential weaknesses is increasingly important, especially as the literature on this topic remains scarce and fragmented [5].

In this context, green social media influencers (or Greenfluencers) may offer an effective digital marketing strategy that could help companies communicate their environmental commitment more credibly, encouraging broader pro-environmental behaviors among consumers [11,12]. Greenfluencers are a specialized group of social media influencers (SMIs) who focus on sustainability, using their platforms to raise environmental awareness, promote sustainable living, and encourage mindful consumption [10,12,13]. Unlike generic SMIs, Greenfluencers enjoy greater credibility in the sustainability field as their actions are perceived as driven by intrinsic motivations rather than financial gain from sponsored contents [10,13].

Given their widely recognized effectiveness, Greenfluencers represent an excellent solution for increasing consumer adoption of pro-circular behaviors. However, as we have seen, current data on CE adoption trends are not encouraging.

Bosone et al. [14] recognize that it is crucial to identify the factors that can be leveraged in green communication strategies and to understand and address the barriers that hinder pro-circular behaviors. Indeed, little attention has been given to the consumers’ adoption barriers, known as obstacles, which hinder consumers’ support for the CE through their daily actions [1] and how different communication tools can reduce these barriers’ perception. Barriers considered within this explorative study are related to both a psychological—reflecting internal cognitive and emotional elements that can significantly hinder individuals from engaging in sustainable behaviors [1]—and a social dimension, emphasizing the significant impact of social structure and relationships on shaping consumer behavior [15].

While Greenfluencers have received increasing attention in the literature, they have mainly been studied in relation to their potential ability to build strong connections with followers, foster engagement, and encourage pro-environmental behaviors [16,17,18]. Other research has focused on their role in driving purchases and generating positive word-of-mouth for green products [12,19]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored how the communication of Greenfluencers can shape consumers’ perceptions of adoption barriers, thus highlighting a gap in defining whether Greenfluencers are truly effective in helping consumers transition toward circular economies.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore for the first time whether and how Greenfluencers’ communication affects consumers’ perceptions of barriers to adopting pro-circularity behaviors. Recognizing how communication can help overcome these obstacles is fundamental to ensuring that increased awareness translates into meaningful and lasting consumer engagement with circular practices.

Through a single case study focusing on the Italian Greenfluencer “Eco-narratrice” (Elisa Nicoli), we conducted a web survey using a convenience sample. This approach allowed us to perform an explorative study to assess the perceived effectiveness of her communication and the barriers consumers perceive in adopting pro-circular practices. The findings of the web survey allow us to explore potential relationships between the perceived effectiveness of the communication and the different types of CE barriers considered (switching costs, inertia, etc.), suggesting which ones are more likely to be influenced by her communication approach.

Understanding the role of Greenfluencers in shaping these barriers—whether directly, by promoting circular products or companies, or indirectly, by encouraging pro-circular behaviors—adds value to the academic literature in two ways. First, it expands research on communication within the circular economy (CE), which is a field that remains underexplored [20,21]. Second, it contributes to the broader discussion on the circular economy by addressing consumer-perceived barriers, which has received limited attention to date [15]. This research suggests how companies can effectively leverage Greenfluencers to promote their circular business models and demonstrate their commitment to sustainability.

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Greenfluencers’ Communication

In the current digital landscape, social media has become deeply embedded in everyday life. These platforms offer an ideal space for raising awareness about critical environmental concerns and promoting conscious consumption patterns, mainly through Greenfluencers’ communication [22].

Greenfluencers are a distinct subset of social media influencers (SMIs) who leverage their expertise in sustainability to cultivate extensive networks of followers, influencing their attitudes and behaviors through consistent content sharing [12,13]. What differentiates Greenfluencers from general SMIs is their dedicated focus on raising awareness about environmental issues, promoting sustainable lifestyles, and encouraging conscious consumption choices [10,23]. Thanks to their frequent sharing of content related to sustainability, Greenfluencers, like other types of SMIs, can establish strong friendship-like bonds with their followers [24]. However, since they often have a large social media following, one-to-one interactions with their audience are not achievable, limiting engagement to parasocial interactions such as likes, comments, shares, and forwards [25,26]. Knupfer et al. [27] define these parasocial relationships as long-term virtual emotional connections between users and Greenfluencers on social media.

Such parasocial relationships are further reinforced by the authenticity and credibility attributed to Greenfluencers [12], making them particularly effective partners for companies looking to communicate their environmental commitment.

Unlike generic influencers, who are often perceived as driven by financial gain, Greenfluencers are seen as motivated by higher-order interests, such as environmental protection and social good [10]. According to Moulard et al. [28], their perceived authenticity is enhanced when Greenfluencers act in line with their ’true self’. Consequently, it positively impacts consumers’ perceptions and behavioral intentions. In this regard, Audrezet et al. [29], drawing on the Self-Determination Theory [30], highlight that influencers who consistently align their content with their passions and values are seen as more authentic, as authenticity stems from intrinsically motivated behaviors. Conversely, those who promote products or behaviors conflicting with their personal identity, thus demonstrating extrinsically motivated behaviors driven by external pressures, will be perceived as inauthentic [31]. Similarly, Boerman et al. [18] highlight that the consistency of Greenfluencers’ messages and actions positively influences their audience’s intention to adopt pro-environmental behaviors.

Moreover, when Greenfluencers act according to intrinsic motivations, this contributes to enhancing their credibility, which is a multidimensional construct comprising trustworthiness—related to the honesty and sincerity of the information conveyed—and expertise, referring to the perception of the Greenfluencers’ competence regarding the statements and information they share [18].

Therefore, despite the apparent significance of Greenfluencers’ communication for the CE, as emphasized by Chamberlin and Boks [21], existing research has largely overlooked the challenges consumers encounter in shifting their behaviors into pro-circularity ones, and therefore, in this context, translating influencer-inspired behavioral intentions into actual sustainable actions.

Therefore, given the growing recognition of Greenfluencers as a powerful tool for driving pro-circular behaviors, this study aimed to evaluate their capacity to alleviate consumer-perceived barriers and promote actionable change.

2.2. Greenfluencers’ Communication and Consumers’ Adoption Barriers to CE

Adopting circular economies requires significant changes from consumers, impacting their psychological dimension and their social and cultural contexts [15]. While awareness of circular economy principles can help consumers form intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, these psychological, social, and cultural factors can still hinder the actual implementation of such behaviors by creating adoption barriers [32].

According to Gonella et al. [1], building on the psychological barriers proposed by Gifford [33], the lack of consumer knowledge regarding the CE can negatively influence their active participation in supporting circular models. In line with this, Rizos et al. [34] have demonstrated that, for many consumers, the CE is not a priority, with many respondents showing limited understanding of what the CE is and the concepts related to it. Similarly, Bosone et al. [14] argue that individuals with little knowledge of pro-environmental behaviors are less likely to change their actions. Therefore, as Greenfluencers also play an educational role in informing consumers, promoting their environmental knowledge creatively [35], we can hypothesize that effective communication by these influencers could help reduce the lack of knowledge about the CE. This, in turn, could diminish the likelihood that consumer ignorance on this subject will prevent them from adopting pro-circular behaviors. So, we can suppose the following:

H1:

Greenfluencers’ communication positively affects consumers’ knowledge about the CE.

Gao and Shao [36] argue that increasing people’s knowledge about environmental issues also enhances their concern. In line with this, Jalali and Khalid [23] emphasize that the green concern exhibited by Greenfluencers can significantly contribute to shaping positive attitudes towards green consumption, as their environmental awareness resonates with their audience. Building on this, Igarashi et al. [37] suggest that social media influencers (SMIs), in general, can shape attitudes through their content.

However, when consumer attitudes are unfavorable, they can act as barriers to adoption. In their studies on the purchase of remanufactured products, Perez Castillo et al. [38] and Hazen et al. [39] identify negative attitudes as retention factors, preventing consumers from purchasing CE-related products. Based on these insights, we can hypothesize that Greenfluencers have a positive influence in creating favorable consumer attitudes towards the CE, ultimately encouraging the adoption of circular economy practices. Thus, we can assume the following:

H2:

Greenfluencers’ communication positively impacts consumers’ attitudes towards the CE.

However, having a positive view of the CE alone may not be sufficient to put pro-circularity behaviors into practice. Moving towards CE models also requires additional sacrifices from consumers, which can be understood in terms of effort, lack of time, and money [40]. As argued by Gonella et al. [1] consumers might resist active participation in sustainable development if the perceived time and money required to engage outweigh the personal benefits they can derive. According to Karman and Lipowski [41], even when purchasing sustainable products, consumers need a fair trade-off between a product’s characteristics and its price, and if this is not achieved, they will not sacrifice their needs just to contribute to environmental protection.

Indeed, in parallel with the literature on switching behavior, which defines switching costs as the monetary and non-monetary costs that consumers face when deciding whether to switch suppliers [42], the dimensions of time and monetary sacrifice can be identified as dimensions for the switching costs to CE models, along with the more general dimension of effort, as highlighted by Quan et al. [40]. We can hypothesize that the effective communication of green influencers has a negative impact on consumers’ perceived switching costs to the CE as, through their content, Greenfluencers manage to encourage the adoption of sustainable behaviors among their audience. Thus, we can assume the following:

H3:

Greenfluencers’ communication negatively affects consumers’ perceived switching costs to the CE.

Moreover, switching to pro-circularity behaviors requires changes in consumers’ daily actions, often involving uprooting old and established habits [15]. As argued by Iacovidou et al. [43], despite efforts to implement circular economies, the persistent effects of linear economies reinforce consumers’ behavioral lock-in, reinforcing pre-existing habits and hindering the adoption of pro-circularity behaviors. Habits help reduce the cognitive effort required when making decisions. The study by Seto et al. [44] highlights that habits are not necessarily harmful to the environment; rather, their impact depends on the specific actions they reinforce. For this reason, the present study focused exclusively on habits that hinder the adoption of pro-circularity behaviors.

These habits, along with attachment—which can be more simply conceptualized as consumers’ inertia—are, according to Quan et al. [40], the reason people tend to engage in the same behaviors repeatedly, resisting any disruptions that might push them to change their behavioral patterns. As discussed earlier, such changes can be facilitated by a favorable trade-off between costs and benefits. However, inertia can sometimes act as a barrier in this process: as Polites and Karahanna [45] argue, individuals may continue their current behavioral patterns even when they stand to gain more benefits from making a change.

In general, since Greenfluencers belong to the broader category of SMIs, their perceived credibility—based on evaluations of their trustworthiness and expertise—leads to a high level of cognitive trust [46]. According to Alnoor et al. [47], this trust acts as a catalyst, encouraging individuals to shift from established habits to new behaviors promoted by SMIs. Moreover, Kapoor et al. [12] and Pittman and Abell [10] emphasize the role of Greenfluencers in promoting changes not only in consumers’ consumption patterns but also in their daily habits and lifestyle choices toward more sustainable ones. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H4:

Greenfluencers’ communication negatively impacts consumers’ inertia towards the CE.

Recent corporate conduct has also contributed negatively by increasing general levels of cynicism toward CE initiatives. A predominant factor in increasing consumer cynicism is greenwashing, which has amplified perceptions of companies as inauthentic and fostered mistrust when they attempt to communicate their commitment to the environment and the transition to circular models [48]. Consequently, consumers’ cynicism derived from greenwashing becomes an additional barrier [49] to supporting circular economy initiatives. As explained by Indibara and Varshney [50], cynicism distances consumers from companies that may genuinely be implementing circular models. This is due to a negative attitude formed when consumers perceive corporate communications as manipulative—concealing a lack of true environmental commitment behind superficial messaging. It is also important to emphasize that this does not diminish consumers’ concern for the environment but reduces their inclination to engage in pro-circularity behaviors such as purchasing eco-friendly products [51].

As Pittman and Abell [10] argue, the use of Greenfluencers as a marketing tool has emerged to address consumer cynicism toward corporate green initiatives. Therefore, as Greenfluencers convey a high level of authenticity [12], we can hypothesize the following:

H5:

Greenfluencers’ communication negatively affects consumers’ cynicism towards the CE.

Psychological essentialism is another key barrier not directly linked to circular companies but to the products they offer. It refers to the tendency to perceive products as entities endowed with unobservable attributes [52,53]. Singh and Giacosa [15] highlighted that people often perceive products created according to CE principles as less authentic and less valuable compared to those from traditional linear economies, as they lack the intangible essence typically associated with “new” products. In particular, the authors argue that psychological essentialism hinders the adoption of CE practices because it prevents resources from being easily reintegrated into production cycles [15]. This perception arises because consumers may feel uneasy thinking someone else might have previously used all or part of the product. In line with this, authors like Chamberlin and Boks [21] refer to this phenomenon as the “disgust barrier.”

The communication of Greenfluencers could prove effective in conveying the value of recycled or reused products to their followers. Therefore, we can hypothesize the following:

H6:

Greenfluencers’ communication impacts consumers’ psychological essentialism attributed to CE products.

Moreover, psychological essentialism can increase the likelihood of consuming more [54]. This tendency can be further intensified by an additional barrier: materialism. This concept opposes sustainability: materialism encourages overconsumption for self-enhancement and social status [55], whereas circular economy principles encourage consumers to buy less or reuse [4]. Therefore, materialism presents a significant obstacle to adopting pro-circular behaviors [15]. For many consumers, the ownership of goods is equated with success, personal achievement [48], and even happiness—so much so that accumulating possessions becomes a core life goal [56].

Therefore, the communication strategies employed by Greenfluencers should aim to reduce the influence of materialism, encouraging people to make more conscious purchases and respect environmental principles [12]. Based on this, we hypothesize the following:

H7:

Greenfluencers’ communication negatively affects consumers’ materialism.

Finally, consumers face another obstacle in adopting circular practices due to the negative influence that their social context can exert. Specifically, the opinions of those within their social circles—such as friends, family, and colleagues—can shape collective attitudes toward the CE. If these opinions are unfavorable, they can contribute to a shared negative perception of circular economy practices [3].

Indeed, as Singh and Giacosa [15] argue, the principles of the CE often conflict with social norms related to ownership and possession. On the other hand, individuals in a social context already favorable to the CE may be more inclined to adopt pro-circularity behaviors when promoted by a Greenfluencer, as their social norms allow them to identify more closely with the values they convey. This identification can lead them to imitate the Greenfluencer’s lifestyle [35] and be more receptive to their advice and recommendations [57]. Consequently, social influence can hinder or encourage the adoption of circular behaviors. However, as Greenfluencers are also embedded within these social contexts, by actively engaging with their audiences, they can influence the development of collective attitudes. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H8:

Greenfluencer communication impacts prevailing beliefs about the circular economy.

The analysis of these research hypotheses enables the exploration of the impact of Greenfluencers’ communication on consumers’ perceptions of barriers to adopting the circular economy.

3. Methods

3.1. Case Study

Case studies are widely used in the social sciences and business research [58]. This method is extremely useful for various purposes: from testing theories to generating theoretical insights from a lack of knowledge about a phenomenon [59,60]. Based on the objectives of the present research, which were to enhance the paucity of knowledge regarding communication and consumer perceptions of CE barriers, a single case study with primary data collected from a web survey was employed.

Our explorative case study focused on one of the top Greenfluencers in the Italian context, @Eco.narratrice. Her Instagram profile has 222.5 k followers, an engagement rate of 3.45%, and an average interaction rate of 302 comments and 8671 likes per post (Phlanx.com). During the investigation period (three weeks from the end of November to mid-December 2024), these metrics collectively suggested that @Eco.narratrice is a credible and effective communicator in her niche. Her ability to maintain high engagement, especially with such a significant follower base, highlights her influence and potential to shape perceptions or behaviors effectively. Indeed, this success may be partly due to her inspiring and engaging examples, which do not come across as overly educational or didactic.

Her activities on social media aim to inspire good practices and transmit her followers’ passion for reducing their environmental impact, thereby facilitating the rapid spread of sensitivity and awareness, which is perfectly in line with the definition of a Greenfluencer [10].

This Greenfluencer has identified the creation of video content characterized by journalistic and scientific rigor as a means of achieving her goals. Her objectives are to minimize people’s environmental impact and communicate the need for this to as many people as possible.

3.2. Sample Description and Data Collection

The study’s sample consisted of 270 respondents, selected in the Italian context based on the convenience sampling criterion [61], specifically their availability to contribute to the analysis. The only initial restriction applied was linguistic, as the study focused on an Italian Greenfluencer. Therefore, respondents needed to understand her communication and, consequently, the questions posed in the survey.

The resulting sample predominantly comprised women (88%), while men represented 11% of the sample, and 1% of respondents preferred not to disclose their gender. No specific age restrictions were set for participants, but the sample featured a predominance of individuals aged between 18 and 27 (34%) and between 28 and 44 (52%). A significantly smaller number of respondents were under 18 (3%) or aged between 45 and 59 (9%) or over 60 (3%).

The data were collected through a web survey created using the Google Forms platform, primarily distributed via major social media networks such as Instagram and Facebook. These distribution channels enabled the survey to reach a substantial number of voluntary participants who, by using social media, were likely already familiar with SMIs. Furthermore, we sought to test our research hypotheses by analyzing the communication of a single Greenfluencer, and the web survey allowed us to do so by implementing a training phase before presenting the questions. Google Forms supported embedding content equivalent to reels (short videos shared on Instagram, also uploaded as YouTube shorts, which are identical to Instagram reels but shared on YouTube).

This approach enabled us to include three of the Greenfluencer’s reels, so that even respondents who were unfamiliar with her could gain an understanding of her communication style and the information she disseminated. As a result, participants could answer the survey questions more thoughtfully.

3.3. Measures

The web survey was divided into two sections: the first focused on evaluating the communication effectiveness of the selected Greenfluencer (@Eco.narratrice), and the second examined perceptions of adoption barriers toward the CE. To assess all the parameters analyzed, 7-point Likert scales were employed (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”).

To analyze communicative effectiveness, we considered several items used in the literature for this purpose: firstly, we assessed the level of familiarity with the Greenfluencer [62], as according to Martensen et al. [63], it can influence a user’s comfort level toward SMIs and thus affect their persuasiveness. We also included the similarity dimension, which can foster trust toward SMIs’ messages [37,63]. To measure this, we used a scale adapted from Bower and Landreth [64]. Furthermore, we considered the measurement of source credibility [65], widely used in the literature on SMIs [63,65]. This value is derived from the combined assessment of expertise and trustworthiness attributed to the Greenfluencer. Specifically, we used scales to measure expertise and trustworthiness, adapted from Ohanian [66].

Additionally, since an informative communication style characterizes @Eco.narratrice, we evaluated the perception of the information conveyed by analyzing a few dimensions of the Citrin [67] and Wixom and Todd [68] scales: relevance, timeliness, and accuracy. In addition, we considered information usefulness based on the scale proposed by Bailey and Pearson [69]. Moreover, we also analyzed respondents’ propensity to adopt the information conveyed by Greenfluencers through Wu and Shaffer’s scale [70].

An overview of how the barriers considered in the study were evaluated using scales established in the literature is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dimensions and items used to address consumers’ perceived barriers to CE.

3.4. Measurement Model

As previously mentioned, this explorative study aimed to evaluate whether the communicative effectiveness attributed to the Greenfluencer impacts the barriers consumers face in adopting pro-circular behaviors. To this end, the following section provides a detailed exposition of the methodology employed in the construction of the measurement model. The overall score for the macro-dimension of the perceived Greenfluencer’s communication effectiveness was calculated from the average scores obtained for each dimension shown in Table 1.

Meanwhile, the adoption barriers towards CE were considered in isolation, and the overall score of each dimension was calculated by determining the means of the respective items. This approach allowed us to capture the cumulative effect of each dimension on the Greenfluencer’s communicative effectiveness and the respondents’ perceptions of the barriers considered.

Therefore, to test our research hypotheses, we implemented a simple linear regression model to investigate the potential relationship between the Greenfluencer’s communicative effectiveness and the perception of each individual barrier.

The model was as follows:

Barrier = β0 + β1(Greenfluencer’s communication effectiveness) + 𝜖

We treated the perceived communication effectiveness of the Greenfluencer as the dependent variable and the perception of barriers as the independent variable. By applying linear regression analysis, this framework allowed us to examine how communication effectiveness variations influence consumer barriers’ perception. This approach enabled us to infer the possible relationship between these variables and assess how effective communication could mitigate perceived barriers.

Before performing the proposed regression model, we checked the correlation values between the dimension related to communication effectiveness and the individual barriers (Table 2). The correlation matrix allowed us to observe the intensity of the relationships between communicative effectiveness and each identified barrier. The coefficients reported in the matrix suggested the existence of significant relationships between communicative effectiveness and specific barriers, such as attitude (r = 0.67, p < 0.001) and switching costs (r = 0.5, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

These preliminary results provided initial evidence of a potential effect of communication on these barriers, further justifying the subsequent regression analyses.

The correlation matrix was crucial for verifying multicollinearity among the barriers themselves. In the matrix, we observed that most correlations between barriers were moderate or low. For example, switching costs and attitude had a correlation value of 0.6 (p < 0.001), which fell within the generally acceptable range (<0.8). Therefore, the risk of multicollinearity appeared limited.

4. Results

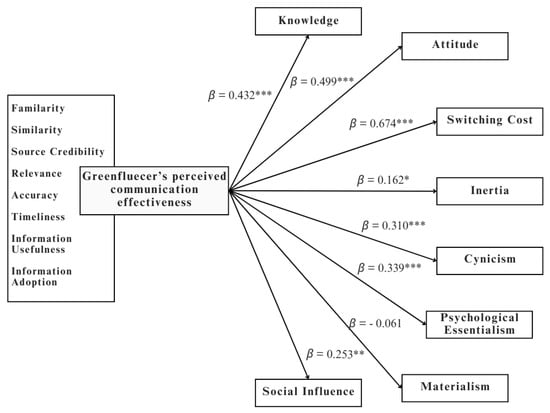

The analysis of the first hypothesis (H1), shown in Table 3, demonstrated a positive and significant effect of the Greenfluencer’s communication on CE knowledge (β = 0.432, t = 8.892, p < 0.001). Similarly, the results for H2 indicated a strong positive impact of the Greenfluencer’s communication on consumers’ attitudes towards the CE, with a coefficient estimate of 0.499 (t = 14.770, p < 0.001). For H3, the effect on switching costs was also positive, significant, and robust (β = 0.674, t = 9.489, p < 0.001). For H4, the effect of the Greenfluencer’s communication on consumers’ inertia was positive and significant, with a coefficient estimate of 0.162 (t = 2.165, p = 0.031). The analysis for H5 showed a significant effect on consumer cynicism (β = 0.310, t = 5.433, p < 0.001), as did H6, where the Greenfluencer’s communication effectiveness affected consumers’ psychological essentialism, with a coefficient estimate of 0.339 (t = 4.718, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Summary of linear regression outputs.

In contrast, for hypothesis H7, no significant effect of the Greenfluencer’s communication on materialism was found, with a coefficient estimate of −0.061 (t = −0.868, p = 0.386). Finally, for H8, the effect of the Greenfluencer’s perceived communication effectiveness on social influence was positive and significant (β = 0.253, t = 2.814, p = 0.005).

Regarding the model fit (Table 4), the R2 and adjusted R2 values varied across the hypotheses. For H1, the model accounted for approximately 22.8% of the variance (R2 = 0.2278), whereas for H2 and H3, the models showed higher predictive power, with R2 values of 0.4487 and 0.2515, respectively. For H4, although the effect was deemed to be significant, the model explained a negligible proportion of the variance (R2 = 0.0172). For H5 and H6, the R2 values were 0.0992 and 0.0767, respectively. Hypothesis H7 confirmed the lack of significance, with an R2 value of 0.0028, while for H8, the model explained approximately 2.9% of the variance (R2 = 0.0287).

Table 4.

Model fit.

In summary, the results indicate that the Greenfluencer’s communication effectiveness had a positive and significant effect on most of the dependent variables analyzed.

Figure 1 graphically shows the results of the β coefficients obtained from linear regression analysis.

Figure 1.

Framework with β coefficients from linear regression analysis. Note: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The strongest effects are observed in consumers’ attitudes (H2), perceived switching cost (H3), and knowledge about CE (H1). However, hypothesis H7 is not supported, suggesting no significant relationship with materialism, an area that warrants further investigation.

5. Discussion

The results of our explorative study partially confirm the effectiveness of Greenfluencers in overcoming barriers to their followers’ pro-circularity behaviors. However, they also highlight several critical issues related to the potential inability of @Eco.narratrice communication to effectively address some consumer barriers to adopting circular economy practices.

The findings of our analysis reveal that the Greenfluencer taken into analysis may positively impact consumers’ knowledge about the CE. This result confirms previous findings by Buczyńska-Pizoń [74], who highlighted the effectiveness of Greenfluencer communication in spreading eco-friendly practices among their followers, and Chwialkowska [75], who emphasized that this communication helps in addressing the barrier to adopting a more sustainable lifestyle posed by a lack of knowledge. Therefore, our result validates the hypothesis that Greenfluencers’ communication activities on social media can serve as an effective tool for enhancing consumers’ understanding of CE principles and how their daily actions can contribute to their promotion, thus preventing a lack of knowledge from hindering their support for the CE (H1).

The second hypothesis (H2), which proposes a positive relationship between the effectiveness of Greenfluencers’ communication and consumers’ favorable attitudes towards circular economies, has also been confirmed. As demonstrated by Audrezet et al. [29], SMIs possess the capacity to influence consumer attitudes. Our findings align with this assertion, indicating that Greenfluencers can effectively enhance public perceptions of the circular economy.

Furthermore, a particularly interesting finding is the rejection of the hypothesis that Greenfluencers can decrease consumers’ perceptions of the switching costs associated with transitioning to a pro-circularity lifestyle and consumption habits. As argued by Chwialkowska [75], influencers should demonstrate that adopting sustainable behaviors—despite requiring additional effort—is worthwhile for ensuring a better future. This, in turn, could serve as a factor in reducing the perceived switching costs. Similarly, Knupfer et al. [27] emphasize that, particularly among younger audiences, Greenfluencers positively encourage engagement with both low-effort activities and those that are more demanding. However, our findings do not align with previous studies, offering a different perspective from what has emerged in the literature (e.g., [10,12]). It appears that the communication of @Eco.narratrice, in informing consumers about the pro-circularity behaviors to adopt, can increase their awareness of the sacrifices required in terms of time, effort, and money to support the CE. Thus, H3 has not been confirmed.

The positive relationship between switching costs and the communicative effectiveness of @Eco.narratrice could explain the rejection of the fourth hypothesis (H4), which has not been confirmed. As Polites and Karahanna [45] argued, inertia reflects a preference for maintaining the status quo, even when the potential benefits significantly exceed the sacrifices required. However, if switching costs are perceived to be higher than the benefits, inertia clearly increases as well.

An additional finding that contradicts previous results in the literature is the probable amplifying effect of cynicism towards the CE as the perceived communicative effectiveness of the Greenfluencer increases. Previous research has demonstrated that Greenfluencers enjoy greater perceived authenticity, expertise, and trust compared to generic influencers or celebrities, enabling them to overcome followers’ resistance to sustainability-related topics (e.g., [12,24]). Moreover, as argued by Pittman and Abell [10], the use of Greenfluencers for promotional purposes stems from their authenticity, which has the potential to mitigate consumer cynicism triggered by widespread greenwashing practices—an issue that has become more prominent as the environmental crisis has gained serious attention. This suggests that the level of consumer cynicism remains too high and that even improved communication fails to mitigate its barrier effect on adopting the CE. Thus, H5 has not been confirmed.

However, the results confirm H6, showing that @Eco.narratrice demonstrated a strong ability to convey to CE products the intrinsic and intangible attributes that typically characterize “new” products. This could establish a positive relationship between her communicative effectiveness and the increasing perception of psychological essentialism related to CE products. This aligns with Chwialkowska’s [75] findings, which suggest that SMIs can challenge the common misconception that products adhering to circular economy principles, such as recycled ones, are less effective than those produced within linear economies. Moreover, the data revealed a potential negative relationship between the efficacy of communication and materialistic tendencies, confirming H7. This may suggest that the Greenfluencer’s advocacy for a circular economy lifestyle (centered around reduced consumption and extended product lifespans) could, to some extent, negatively influence a prevailing materialist culture that promotes excessive consumption. However, this inference remains inconclusive, given that statistical significance for this relationship was not achieved. Given the lack of studies on this topic, this finding should be compared with future research.

Finally, the positive relationship observed between communicative effectiveness and the social influence exerted could be interpreted in this study as a reinforcement by the Greenfluencer’s communication of a social context that is already inclined to embrace the circular economy (CE). Thus, H8 has been confirmed. Results from previous studies by Knupfer et al. [27] and Cui et al. [26] emphasize that Greenfluencers, through parasocial relationships, foster the adoption of environmentally activist behaviors via social learning while strengthening followers’ identification with their values and promoting the integration of environmental principles into personal identity. The pro-circularity behaviors promoted by the Greenfluencer analyzed seem to align with the prevailing mindset of the social community surrounding the respondents of our web survey. According to Social Identity Theory, individuals are more likely to follow the norms and values of those around them [76]. As a result, this process fosters a greater inclination toward sustainable consumption patterns.

In this context, our findings further support the role of Greenfluencers as influential social actors who, by fostering individuals’ identification with the values they promote, reinforce existing sustainability tendencies within their communities, enhancing both the adoption and implementation of the behaviors they advocate [35,57].

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Understanding the role of Greenfluencers’ communication effectiveness in shaping consumer perceptions of adoption barriers towards the CE contributes to the academic literature in two ways. First, it enriches research on communication within the CE context, which is a field that remains largely unexamined [20,21]. This explorative study represents the first attempt to systematically analyze the potential impact Greenfluencers’ communication effectiveness can have on adoption barriers towards CE. Based on the study conducted, it appears that the communicative effectiveness of Greenfluencers could positively impact various barriers, such as knowledge, attitudes, psychological essentialism, and social influence. However, this study also highlights certain limitations regarding @Eco.narratrice’s potential ability to reduce the perception of some barriers, as evidenced by the increased perception of switching costs, inertia, and cynicism among respondents, showing the opposite perspective to that supported by previous studies in the literature [12,24,27].

On the other hand, it deepens the field of study on the circular economy itself, advancing the debate on consumer-perceived CE barriers, an area that has so far received limited consideration [15]. It also extends previous studies on consumer adoption barriers toward the CE. Specifically, it contributes—within the limitations of the analyzed sample—to clarifying which barriers previously identified in the literature (e.g., [1,15]) could be more effectively mitigated through Greenfluencer communication. At the same time, it highlights the barriers most strongly perceived by our sample, which are more resistant to change, potentially shedding light on why consumers’ pro-circularity behaviors remain limited.

Moreover, more broadly, this study contributes to the ongoing debate on alternative communication channels that may more effectively enhance consumer awareness of the CE. These channels could potentially overcome various limitations, such as the perceived inauthenticity and low reliability [65,77] often associated with traditional communication media.

6.2. Managerial Implications

This research provides valuable insights for both marketing managers and Greenfluencers. It helps marketing managers understand how to effectively engage with Greenfluencers to promote circular business models and demonstrate their commitment to sustainability. At the same time, it offers Greenfluencers feedback on how their communication is perceived and its potential impact on consumer perceptions of CE barriers, enabling them to refine their strategies to better address areas where their current approach may be less effective. Our findings highlight the potential of Greenfluencers as a means to address consumers’ limited knowledge and unfavorable attitudes toward CE. Specifically, when the consumer perceives the communication as effective, companies can indirectly benefit from the enhancement of consumer knowledge and attitudes toward the CE, driven by the indirect learning process and imitation of Greenfluencers on social media [75]. Therefore, firms implementing educational strategies can benefit from collaborating with Greenfluencers to explore relevant topics while respecting their autonomy in communication style and content [24]. This suggests that firms should strategically collaborate with them to create engaging, informative, and actionable content that resonates with their audience.

Educating consumers through clear, transparent, and truthful communication about a company’s circular economy initiatives, conveyed via Greenfluencers’ personal communication style, can also empower consumers to better discern between genuine and misleading CE practices. This presents an indirect advantage for firms that effectively implement CE practices, as consumers can recognize greenwashing. As a result, companies can strengthen their reputation and trust with their audience by aligning with authentic sustainable practices, while also boosting the credibility of Greenfluencers who do not endorse companies engaging in greenwashing.

Moreover, our findings suggest leveraging the communication power of Greenfluencers to enhance consumers’ perceptions of the authenticity of products originating from circular economies, demonstrating that their features and performance are not inferior to those of products from linear economies. This approach could be particularly beneficial for certain product categories where the perception of lower quality, or the feeling of being dirty, used, or obsolete, is even more pronounced [78].

However, it can be argued that the exploitation of Greenfluencers may not always be the solution to all consumers’ barriers.

Our findings suggest that @Eco.narratrice’s effective communication of circular economy initiatives has raised consumers’ perceptions of switching costs. This indicates that for consumers, supporting the CE still involves significant costs (both monetary and non-monetary) that may outweigh the perceived benefits. Therefore, we encourage firms to use simpler language in their communications, making their green messages more accessible to consumers and reducing the risk of amplifying the perception of switching costs.

Green influencers may consider using language that minimizes the idea that adopting pro-circular behaviors involves significant sacrifices. Although these behaviors require more effort, time, and financial commitment than non-green actions, a more accessible, even lighthearted, communication style could help mitigate the perception of these challenges. The findings also highlight that as the communication effectiveness of Greenfluencers increases, respondents exhibit higher levels of cynicism and inertia. Therefore, we suggest that Greenfluencers, independently or in collaboration with firms, could leverage well-established practices on social media such as “viral challenges” [79,80]. Consumers could be encouraged to change their habits through the reward logic (e.g., participation in the challenge could include a prize). The virality often associated with such activities may help create a ripple effect, spreading the trend widely. As a result, more individuals, driven by curiosity and the desire to join the challenge, may feel motivated to question their habits and try engaging in behaviors that support the circular economy.

To overcome cynicism, we also recommend that Greenfluencers foster their credibility, for example, by associating the conveyed information with reliable sources, such as studies, reports, or expert interviews from well-known and easily recognizable organizations that consumers perceive as authoritative and trustworthy. This would contribute to enhancing the relationship of trust with their followers, which proves to be essential for significantly influencing their behaviors, opinions, and purchase intentions [81]. For businesses, these limitations of Greenfluencers—regarding the increase in levels of inertia and cynicism—do not necessarily represent an obstacle to utilizing Greenfluencers in their green digital communication strategies. On the contrary, based on the results of this study, businesses could become aware of these limitations and collaborate with Greenfluencers to develop a communication strategy that, while respecting the creative autonomy of the green SMI, aims to avoid exacerbating these two perceived barriers.

7. Summary and Prospects

This study employed a single-case analysis to investigate the possible consequences of Greenfluencer communication in fostering pro-circular behavior. The investigation specifically examineed the efficacy of communication in influencing consumers’ perceptions of barriers (e.g., switching costs, cynicism, inertia, etc.), which may impede adopting such behaviors. By expanding the extant literature on communication within the circular economy and addressing consumer-perceived barriers, this study provides valuable guidance for companies aiming to leverage Greenfluencers to promote circular business models and sustainability efforts.

Despite its potential contribution, the study is not without limitations, which could serve as starting points for future research.

First, the literature on consumer adoption barriers to the CE remains scarce and fragmented, and the barriers considered in our analysis may not encompass all the psychological and social obstacles consumers face, as indicated by the low R2 values recorded.

This limitation could result in a partial view of the impact of Greenfluencers’ communication effectiveness on such barriers. Therefore, we encourage future research to include additional barriers that may have been omitted in this study, thereby contributing to further enriching the still-limited literature on this topic.

In addition, we did not consider any mutual influence relationships between the various barriers. Future research could also consider interdependencies between barriers and how Greenfluencers’ communication can focus on these interrelationships, potentially achieving a broader impact on multiple barriers simultaneously (e.g., [1]).

Furthermore, our study focused on a convenience sample limited to the Italian context and to a single Greenfluencer, which may raise concerns regarding the generalizability of the findings. Future research could replicate this analysis with a broader sample and in different contexts to assess how cultural differences might influence how Greenfluencers impact consumers’ perception of barriers to CE adoption. Moreover, extending this analysis to other Greenfluencers would be valuable to validate our findings and ensure that the results are not solely linked to @Eco.narratrice’s communication style. For example, examining how consumers in different countries or regions respond to Greenfluencers could reveal insights into how cultural factors shape the effectiveness of communication strategies [26]. Finally, our explorative study relies on self-reported data, which inevitably introduces potential biases such as social desirability and recall bias [82]. These biases may have influenced participants’ responses and, consequently, affected the accuracy of our findings. Therefore, we recommend that future research explore these issues further by employing alternative methodologies, such as observational studies, experimental designs, or mixed-methods approaches. These methods can provide more objective and comprehensive insights into how the communicative effectiveness of Greenfluencers influences consumer perceptions of barriers to adopting pro-circularity behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C., A.B. and F.S.; methodology, F.S. and A.B.; software, F.S. and I.D.; validation, F.C. and F.S.; formal analysis, F.C. and A.B.; investigation, F.C., F.S. and A.B.; resources, F.C.; data curation, F.S. and I.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, F.C., F.S. and A.B.; visualization, F.S. and A.B.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to ART. 13–14 OF GDPR 2016/679 (GENERAL DATA PROTECTION REGULATION)—In Italy Privacy Code (Legislative Decree 196/2003), this research does not require IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gonella, J.D.S.L.; Godinho Filho, M.; Ganga, G.M.D.; Latan, H.; Jabbour, C.J.C. A behavioral perspective on circular economy awareness: The moderating role of social influence and psychological barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 141062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materson, V. 4 Charts to Show Why Adopting a Circular Economy Matters. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/04/circular-economy-waste-management-unep/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Neves, S.A.; Marques, A.C. Drivers and barriers in the transition from a linear economy to a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morseletto, P. Targets for a circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Luis, J.; Carbonell-Alcocer, A.; Gertrudix, M.; Gertrudis Casado, M.D.C.; Giardullo, P.; Wuebben, D. Recommendations to improve communication effectiveness in social marketing campaigns: Boosting behavior change to foster a circular economy. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2147265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, S.; Lazanyuk, I.; Revinova, S.; Gomonov, K. Barriers of consumer behavior for the development of the circular economy: Empirical evidence from Russia. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassi, A.; Falegnami, A.; Meleo, L.; Romano, E. The GreenSCENT Competence Frameworks. In The European Green Deal in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Circularity Gap Report 2024. Available online: https://reports.circularity-gap.world/cgr-global-2024-37b5f198/CGR+Global+2024+-+Report.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Sailer, A.; Wilfing, H.; Straus, E. Greenwashing and bluewashing in black Friday-related sustainable fashion marketing on Instagram. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Abell, A. More trust in fewer followers: Diverging effects of popularity metrics and green orientation social media influencers. J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 56, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Lou, J. Encouraging prosocial consumer behaviour: A review of influencer and digital marketing literature. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 2711–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.S.; Balaji, M.S.; Jiang, Y. Greenfluencers as agents of social change: The effectiveness of sponsored messages in driving sustainable consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 533–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, S.M.; Ghaffari, M.; Zare, H. Influencer marketing research: A systematic literature review to identify influencer marketing threats. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosone, L.; Chaurand, N.; Chevrier, M. To change or not to change? Perceived psychological barriers to individuals’ behavioural changes in favour of biodiversity conservation. Ecosyst. People 2022, 18, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Giacosa, E. Cognitive biases of consumers as barriers in transition towards circular economy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, S.; Maier, E. The effect of green influencer message characteristics: Framing, construal, and timing. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1979–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekoninck, H.; Van Houtven, E.; Schmuck, D. Inspiring G(re)en Z: Unraveling (para)social bonds with influencers and perceptions of their environmental content. Environ. Commun. 2023, 17, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; Meijers, M.H.; Zwart, W. The importance of influencer-message congruence when employing greenfluencers to promote pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Leung, W.K.; Chang, M.K.; Shi, S.; Tse, S.Y. Harvesting sustainability: How social capital fosters cohesive relationships between green social media influencers and consumers to drive electronic word-of-mouth behaviours. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 42, 444–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaghel, R.; Oghazi, P.; Lisboa, A. The transformative impact of the circular economy on marketing theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 195, 122780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, L.; Boks, C. Marketing approaches for a circular economy: Using design frameworks to interpret online communications. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U. Seizing momentum on climate action: Nexus between net-zero commitment concern, destination competitiveness, influencer marketing, and regenerative tourism intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.S.; Khalid, H.B. The influence of Instagram influencers’ activity on green consumption behavior. Bus. Manag. Strategy 2021, 12, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitan, S.; Van Esch, P.; Soma, V.; Kietzmann, J. Influencer marketing and authenticity in content creation. AMJ 2022, 30, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekoninck, H.; Schmuck, D. The “greenfluence”: Following environmental influencers, parasocial relationships, and youth’s participation behavior. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 6615–6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Tang, S.; Iqbal, Q. The role of green influencers on users’ green consumption intention: An empirical study from China and Pakistan. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knupfer, H.; Neureiter, A.; Matthes, J. From social media diet to public riot? Engagement with “greenfluencers” and young social media users’ environmental activism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulard, J.G.; Garrity, C.P.; Rice, D.H. What makes a human brand authentic? Identifying the antecedents of celebrity authenticity. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; De Kerviler, G.; Moulard, J.G. Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buvár, Á.; Zsila, Á.; Orosz, G. Non-green influencers promoting sustainable consumption: Dynamic norms enhance the credibility of authentic pro-environmental posts. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1112762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, E. The consumer adoption of sustainability-oriented offerings: Toward a middle-range theory. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2013, 21, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Hirschnitz-Garbera, M.; Ioannou, A. The Circular Economy: Barriers and Opportunities for SMEs; CEPS Working Documents No. 412/September; CEPS: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, M.J.B.; de Lima, M.I.C.; dos Santos, M.D.; da Silva Santos, A.K.; da Costa, M.F.; Melo, F.V.S.; de Farias, S.A. Exploring the Interplay Among Environmental Knowledge, Green Purchase Intention, and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Greenfluencing Scenarios: The Mediating Effect of Self-Congruity. Sustain. Dev. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Shao, B. Why Do Consumers Switch to Biodegradable Plastic Consumption? The Effect of Push, Pull and Mooring on the Plastic Consumption Intention of Young Consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, R.; Bhoumik, K.; Thompson, J. Investigating the effectiveness of virtual influencers in prosocial marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 2121–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Castillo, D.; Ornelas Sanchez, S.; Vera Martínez, J.L.G. Switching intention towards the purchase of remanufactured cellphones: Development of a scale in the Mexican context. ESPACIOS 2020, 41, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, B.T.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Wang, Y. Remanufacturing for the circular economy: An examination of consumer switching behavior. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Koo, B.; Han, H. Exploring the factors that influence customers’ willingness to switch from traditional hotels to green hotels. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karman, A.; Lipowski, M. Switching to sustainable products: The role of time, product, and customer characteristics. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1082–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.S.; Taylor, S.F.; St. James, Y. “Migrating” to new service providers: Toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovidou, E.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Purnell, P. A systems thinking approach to understanding the challenges of achieving the circular economy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24785–24806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Davis, S.J.; Mitchell, R.B.; Stokes, E.C.; Unruh, G.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D. Carbon lock-in: Types, causes, and policy implications. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polites, G.L.; Karahanna, E. Shackled to the status quo: The inhibiting effects of incumbent system habit, switching costs, and inertia on new system acceptance. MIS Q. 2012, 21, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, Q.; Davison, R.M. How do digital influencers affect social commerce intention? The roles of social power and satisfaction. Inf. Technol. People 2021, 34, 1065–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnoor, A.; Abbas, S.; Khaw, K.W.; Muhsen, Y.R.; Chew, X. Unveiling the optimal configuration of impulsive buying behavior using fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis and multi-criteria decision approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 81, 104057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malodia, S.; Bhatt, A.S. Why should I switch off: Understanding the barriers to sustainable consumption? Vision 2019, 23, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheoran, M.; Kumar, D. Benchmarking the barriers of sustainable consumer behaviour. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indibara, I.; Varshney, S. Cynical consumer: How social cynicism impacts consumer attitude. J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrevova, L.; Kotkova Striteska, M.; Kuba, O.; Prakash, V.; Prokop, V. When Trust and Distrust Come Into Play: How Green Concern, Scepticism and Communication Affect Customers’ Behaviour? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.E.; Knobe, J. The essence of essentialism. Mind Lang. 2019, 34, 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, M.; Joe, M. Factors that influence the successful marketing of bioplastic products in Zimbabwe: Towards a circular economy by 2030. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2023, 6, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kwant, C.; Rahi, A.F.; Laurenti, R. The role of product design in circular business models: An analysis of challenges and opportunities for electric vehicles and white goods. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1728–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issock, P.B.I. Re-assembling materialism, sustainability and subjective well-being: Empirical evidence from E-waste disposal in an emerging market. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L.; Dawson, S. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F. Effective influencer marketing: A social identity perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Hak, T. Case Study Methodology in Business Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fidel, R. The case study method: A case study. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 1984, 6, 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saumure, K.; Given, L.M. Convenience sample. SAGE Encycl. Qual. Res. Methods 2008, 2, 124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F. Effects of violence and brand familiarity on responses to television commercials. Int. J. Advert. 2001, 20, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martensen, A.; Brockenhuus-Schack, S.; Zahid, A.L. How citizen influencers persuade their followers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, A.B.; Landreth, S. Is beauty best? Highly versus normally attractive models in advertising. J. Advert. 2001, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh Wilkie, D.C.; Dolan, R.; Harrigan, P.; Gray, H. Influencer marketing effectiveness: The mechanisms that matter. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 3485–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, A.V. Information Quality Perceptions: The Role of Communication Media Characteristics; Washington State University: Pullman, WA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wixom, B.H.; Todd, P.A. A theoretical integration of user satisfaction and technology acceptance. Inf. Sys. Res. 2005, 16, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.E.; Pearson, S.W. Development of a tool for measuring and analyzing computer user satisfaction. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Shaffer, D.R. Susceptibility to persuasive appeals as a function of source credibility and prior experience with the attitude object. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.; Lau, L.B. Explaining green purchasing behavior: A cross-cultural study on American and Chinese consumers. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2001, 14, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, A.E.; Moulard, J.G.; Richins, M. Consumer cynicism: Developing a scale to measure underlying attitudes influencing marketplace shaping and withdrawal behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranko, Z.; Andrews, D.; Chaer, I.; Newton, E.J. Circular economy and behaviour change: Using persuasive communication to encourage pro-circular behaviours towards the purchase of remanufactured refrigeration equipment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczyńska-Pizoń, N. The promotion of the zero-waste concept by influencers in social media. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2020, 52, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A. How sustainability influencers drive green lifestyle adoption on social media: The process of green lifestyle adoption explained through the lenses of the minority influence model and social learning theory. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Gupta, R.; Nair, K. Time for sustainable marketing to build a green conscience in consumers: Evidence from a hybrid review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 443, 141188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Farrell, J.R. More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.S.; Biswas, M.I.; Azad, N. The role of online information sources in enhancing circular consumption behaviour: Fostering sustainable consumption patterns in the digital age. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1419–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riachi, A. Role of Social Media Marketing in Building Cause-Oriented Campaigns. Dutch J. Financ. Manag. 2022, 5, 23417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; Miller, V.; Moore, S. Prestige, performance and social pressure in viral challenge memes: Neknomination, the Ice-Bucket Challenge and SmearForSmear as imitative encounters. Sociology 2018, 52, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, K.; Azam, M. The power of social media influencers: Unveiling the impact on consumers’ impulse buying behaviour. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).