Abstract

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a crucial role in fostering economic growth and sustainability, requiring a deliberate emphasis on innovation and applying knowledge to navigate ever-changing markets. This study, grounded in resource-based view (RBV) theory, explores the synergy of entrepreneurial leadership and team diversity, exploring pathways to entrepreneurial success in Pakistan’s SMEs. This study employed a cross-sectional design, utilizing a non-probability convenience sampling approach to survey 350 owners, supervisors, managers, and employees of SMEs in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Data were gathered through a survey questionnaire and subsequently analyzed using SPSS and SMART-PLS to validate the measurement model and examine the hypotheses for moderated analysis. The results indicated a significant moderating influence. Entrepreneurial leadership accounted for 15.8% of the variation in entrepreneurial success, while team diversity contributed 8.5%. Moreover, the moderating influence of team diversity substantially affected ES (59.7%), underscoring the pivotal role of team diversity in the interplay between EL and ES. Drawing from RBV theory, this study advances the framework by acknowledging that team diversity is a crucial element that strengthens the connections between EL and ES. This study enhances the existing literature by clarifying the mechanisms by which leadership and diversity collaboratively promote entrepreneurial outcomes. This highlights the necessity for SME leaders and policymakers to utilize team diversity as a strategic asset to improve competitive advantage and ensure sustainable success.

1. Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a crucial role in national economic growth by fostering innovation, generating employment [1], and contributing significantly to GDP [2]. Despite their unique challenges, SMEs in developing countries such as Pakistan are vital for economic growth, job creation, and poverty reduction [1,2]. The small and medium-sized enterprise sector is widely regarded as the economic backbone of every economy. According to the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Authority (SMEDA), there are approximately two million small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Pakistan. These businesses are responsible for forty percent (40%) of Pakistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) and twenty-five percent (25%) of the country’s exports [3,4]. In light of this, identifying the characteristics of prosperity that prosperous small and medium-sized enterprises share in Pakistan will have significant repercussions. The success of SMEs largely depends on an array of entrepreneurial abilities, such as financial resources, technological expertise, knowledge, and leadership abilities, to establish a stable business environment [5]. Sustained success depends on leadership behaviors, including innovation, market responsiveness, risk-taking, and opportunity exploitation [6], collectively termed entrepreneurial leadership [7]. Entrepreneurial leadership involves strategically allocating resources to recognize and exploit opportunities [8], with empirical studies highlighting its essential contribution to entrepreneurial success [7]. Success is defined as the enduring market presence of business ventures over time [9]. This leadership approach affects critical factors of entrepreneurial outcomes such as strategic resource management [10], wealth creation [11], innovation performance [12], new venture success [13], employee engagement [14], and organizational creativity [15]. These factors collectively highlight the complex role of entrepreneurial leadership in influencing enterprise viability and competitiveness.

Regardless of the pivotal role of entrepreneurial leadership in driving innovation and success, financial resources, market conditions, and team composition are strong predictors of entrepreneurial success [16]. In other words, entrepreneurial leadership may not fully predict entrepreneurial success; instead, diverse team compositions may amplify its effect on entrepreneurial leadership [17]. Studies suggest that diverse team compositions bring innovation, competitiveness, and creativity to an enterprise [18,19]. Studies have also indicated that entrepreneurial leadership employs its ability to create a team possessing various skills for organizational success. This diversity in team composition may foster entrepreneurial success [20]. A diversified team is characterized by inclusion, enhanced decision-making, increased adaptability, and broader market understanding [19]. These characteristics of a diversified team align with entrepreneurial leadership characteristics. Hence, these diversified teams support entrepreneurial leadership in bringing about innovation and creating employment opportunities essential for entrepreneurial success [20]. Although entrepreneurial leadership and team diversity influence entrepreneurial success, it is unclear how team diversity moderates this effect [17].

According to the authors of [21,22], entrepreneurial success (ES) encompasses personal fulfillment, a key component of long-term business viability. From the perspective of micro-businesses, entrepreneurial success necessitates that entrepreneurs possess unique abilities and personality traits, such as leadership skills, domain expertise, capacity for entrepreneurial opportunity recognition, innovation capability, and technological proficiency [23,24,25]. Gaining the trust of stakeholders and providing them with the necessary resources and information is a crucial part of a successful entrepreneurial leader (EL) [26]. Since the success of microbusiness owners frequently hinges on their leadership qualities, the EL is of utmost importance to them [27]. Although the EL substantially affects ES, company performance, growth, and sustainability [28,29], the connection between the EL and ES requires further investigation [27]. The need to examine this relationship in the context of SMEs has become more imperative as SMEs are the backbone of an economy [3], and the role of leadership and diverse team composition has become significant in addressing the issues of scarce financial, technical, and human resources [13]. According to the authors of [21,22], entrepreneurial success (ES) is fostered when team members are allowed to succeed in different areas through entrepreneurial leadership (EL). Existing studies have explored the antecedents and consequences of entrepreneurial leadership [25], its direct impact on entrepreneurial success [7], and the mediating mechanisms that support this relationship [7,20]. Moderating variables that influence the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success, primarily contextual or structural factors, have been insufficiently examined, resulting in significant gaps in comprehending the boundary conditions that define this dynamic. Thus, it is essential to explore the influence of entrepreneurial leadership on SME success. The existing literature has not adequately reviewed the impact of entrepreneurial leadership (EL) in SMEs on entrepreneurial success (ES) via team diversity, especially in developing countries such as Pakistan.

This study addresses this gap by empirically examining a moderation model grounded in the resource-based view (RBV) in small and medium enterprises in Pakistan. The resource-based view assumes that organizations employ their resources and capabilities to gain competitive advantages. According to resource-based theory [30], entrepreneurial leadership is a “managerial resource” capable of influencing entrepreneurial success. As a managerial asset, we contend that entrepreneurial leadership concentrates on managing human capital to establish a heterogeneous team with entrepreneurial behavior, processes, and competencies, including risk-taking, innovation, and dynamic capabilities in small firms [31,32,33]. This study addresses the question of why entrepreneurial leadership is essential for the success of start-ups, along with other factors such as financial resources, technology integration, knowledge and skills, and market conditions [5]. It also investigates the moderating influence of team diversity on the entrepreneurial leadership (EL)–success (ES) relationship. We addressed the question of how diverse team composition brings about a mix of knowledge, skills, experiences, and perspectives.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurial Leadership

Entrepreneurial leadership (EL) is a way to realize goals, provide job opportunities, and promote empowerment [34]. EL is defined as risk-taking and innovation [35]. The authors of [36] describe EL as “leadership that develops visionary frames to mobilize a ‘supporting cast’ of individuals committed to discovering and exploiting strategic value creation”. EL helps individuals discover opportunities, create new products, and fill market gaps [37]. It encourages employees to accomplish organizational goals and combines the visionary and innovative processes essential for entrepreneurship [38]. EL focuses on overcoming obstacles, reducing risks, and minimizing uncertainty in venture creation. In today’s competitive world, organizations prioritize hiring leaders who recognize opportunities, create visions, and craft favorable circumstances [8]. These leaders are characterized by innovation, risk-taking, market awareness, and a strong focus on gaining a competitive edge [15]. Leadership is a critical skill for microbusiness owners and managers, playing a fundamental role in innovation and adaptability to environmental changes [39]. Entrepreneurial leadership emphasizes vision, problem-solving, and decision-making.

Grounded in the entrepreneurship and leadership literature, EL integrates scenarios and cast enactment [40]. It focuses on five key functions: framing challenges, absorbing uncertainty, underwriting, building commitment, and defining gravity [41]. Entrepreneurial leaders exhibit key traits such as opportunity recognition, effective coordination and planning, adaptability to new circumstances, and creative problem-solving [42]. EL requires flexibility, quick problem resolution, decisive action, and a calculated risk-aware approach [30,43]. Organizations need entrepreneurial leadership to survive in today’s unpredictable and ever-changing business environment [29]. According to the authors of [8], EL is about efficiently managing limited resources to gain a market advantage. It also involves challenging the status quo, experimenting with new ideas, demonstrating resilience, and fostering innovation [44]. EL has several key antecedents, including a focus on challenges, an entrepreneurial mindset, ambidexterity, the ability to absorb uncertainty, the capacity to learn from failure, emotional intelligence, willingness to follow others, and strong work values [8]. Some significant organizational benefits of EL include strategic resource management, wealth creation, innovation performance, start-up success, employee voice, and creativity [21,45]. EL drives financial success, competitive advantage, and profitability [7]. EL effectiveness can be influenced by mediating and moderating mechanisms such as fostering an innovative culture characterized by invention, transparency, openness, and employee voice [15] or leveraging diverse team compositions to enhance EL’s impact on EL [19,20]. Therefore, EL is not just a leadership style but a strategic necessity for organizations aiming for long-term success.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Success

Entrepreneurial success is a multi-faceted phenomenon. Researchers have contended that both monetary and non-monetary factors may serve as sources of employee satisfaction. Entrepreneurial success is typically linked to venture outcomes. Researchers have indicated that entrepreneurial and venture success is equivalent [4,26]. Therefore, there is a growing focus on entrepreneurial success (ES), which includes personal satisfaction and its contribution to the sustainability of businesses [26]. From a micro-business viewpoint, entrepreneurs need certain traits and skills to succeed [46]. These include the ability to lead, knowledge, recognize opportunities for innovation, and technical know-how [7,26,46]. Entrepreneurship entails innovation, analysis, and the ability to develop future products and services, driven by the emergence of new technologies, products, and services. Entrepreneurial success often requires risk-taking and leveraging existing methodologies to generate new ideas [47,48]. Entrepreneurs create opportunities and enhance their success by engaging with these prospects. For SMEs, success depends on aligning opportunities and maintaining an entrepreneurial mindset [46]. Entrepreneurial success extends beyond profit-making, including social impact, environmental responsibility, and brand reputation [43]. Businesses that integrate sustainability into their core strategies can achieve competitive advantages, access new markets, and strengthen consumer trust [49]. The authors of [50] argued that subjective measures, reflecting entrepreneurs’ self-assessment of their achievements, are critical in evaluating success. Entrepreneurial success is a multidimensional concept encompassing financial and non-financial aspects, such as increasing corporate value and reducing financial risk to prevent bankruptcy [51]. Entrepreneurial satisfaction is also a key indicator of personal and corporate objectives [43].

Additionally, SMEs with strong environmental practices are better positioned to meet regulatory requirements. The primary goal of start-ups and businesses is to adapt, innovate, and seize opportunities to achieve sustainable development and market leadership [52]. Organizational growth and resilience are essential indicators of entrepreneurial success [53]. Entrepreneurial success is not solely measured by financial performance but also includes short-term financial gains and long-term non-financial accomplishments [54]. Studies indicate that entrepreneurs frequently prioritize non-monetary factors in their ventures [55]. Success in entrepreneurship is assessed at both the firm and individual levels [52] using monetary and non-monetary indicators [56]. At the firm level, success is typically measured by growth indicators such as sales, profits, or employment, although these metrics often show weak correlations owing to varying influencing factors [57].

In social entrepreneurship, non-financial aspects, such as sustainability goals, job creation, and satisfaction with organizational performance are crucial, and success is evaluated through both financial and non-financial measures [58]. However, the subjective nature of social value creation makes it challenging to standardize non-monetary success criteria. At the individual level, entrepreneurial success has traditionally been measured by personal wealth and income [59]. Recent research focuses on “subjective entrepreneurial success”, which reflects entrepreneurs’ evaluations of their achievements [60]. This perspective highlights the impact of non-financial factors on business performance and underscores the importance of understanding how entrepreneurs define success on their terms [52].

2.3. Team Diversity

Entrepreneurial leadership facilitates the development of teams characterized by multifaceted diversity (e.g., gender, ethnicity, and cultural background) [54]. Team diversity involves incorporating and harmonizing individuals with various traits, backgrounds, and perspectives [44]. Scholarly research demonstrates that such diversity introduces varied skills, attitudes, and experiential knowledge that enhance innovation, adaptability, and organizational growth [60,61]. Empirical evidence has identified team diversity as a significant predictor of entrepreneurial success [62,63]. The extant literature suggests that because of risk-taking, creativity, and opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial leadership coupled with diverse perspectives, backgrounds, and teams’ expertise develops a culture of agility and innovation [18,62]. In other words, entrepreneurial leadership may create a diverse team that fosters positive outcomes such as entrepreneurial success [20]. While examining the antecedents and consequences of team diversity, the literature suggests that inclusion, human resource policies prioritizing diversity, and inclusive leadership of start-ups promote diversity [64]. Leadership behavior that encourages inclusion promotes diversity and fosters positive individual and organizational outcomes [65]. Similarly, the outcomes of team diversity include innovative solutions, openness, work-group cohesion and business performance, adaptability and resilience, harmony and collaboration, creativity, and mutual respect [45,66]. The authors of [11] asserted that team diversity indicates firm performance and may amplify growth and development.

2.4. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Formation

Theoretical Ground

To obtain a competitive edge, the resource-based view (RBV) is essential [23]. Innovation and strategic development are propelled by resources including knowledge, experience, simplified procedures, money, and commercial networks [7]. Physical assets, human capital, and organizational assets are key resources [67]. Since effective entrepreneurship depends on a strategic blend of various resources, the RBV emphasizes its importance in the entrepreneurial process [31,68,69]. The resource-based view (RBV) highlights the need to optimize skills, assets, and capacities to improve business performance, gain a long-term competitive advantage, ensure sustainability, and nurture entrepreneurial success (ES) [7,26]. Abilities are defined as the ability to perform tasks or activities efficiently using human, physical, and technological resources [70]. These resources are incorporated into functional clusters, where leadership talent is highly valued [71]. According to research, SMEs can use entrepreneurial leadership (EL) to gain a competitive edge, resulting in long-term performance and success [72]. According to the RBV, EL affects ES because it is unique, valued, non-substitutable, and difficult to replicate [73,74]. To achieve entrepreneurial success [29], businesses must recognize and nurture EL.

2.5. Hypotheses Formation

2.5.1. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Entrepreneurial Success

Entrepreneurs are strongly dedicated to maintaining long-term economic success [75]. Entrepreneurial leadership (EL) is a unique approach that uses various abilities to employ resourcefulness and inventiveness in competitive settings [76]. Entrepreneurial leaders foresee and resolve obstacles by successfully negotiating and obtaining essential resources, removing barriers to success, seizing opportunities, and adding value [77,78]. EL is also necessary for corporate development, motivating innovation, and improving worker performance [79]. Enhancing self-efficacy and entrepreneurial skills empowers workers and promotes entrepreneurial success (ES). Leaders who practice entrepreneurialism inspire their teams to take the lead in accomplishing organizational objectives, increasing the likelihood of entrepreneurial success (ES) and creating value [80]. Various sources have shown that EL is critical for long-term company success, growth, and performance [81,82]. In particular, EL has a beneficial effect on ES [29], entrepreneurship performance [24], company performance [23], success for SMEs [7,25,26,29], and firm growth [83].

Nevertheless, additional research is necessary, especially regarding micro-businesses in developing economies. The literature emphasizes the essential function of leadership in attaining success at the individual, team, and organizational levels [84]. Leaders exhibiting proactiveness, creativity, innovation, risk-taking abilities, and the capacity to manage diverse teams are associated with driving firm growth and economic development [7]. Entrepreneurial leaders exhibit a distinct vision, adept resource management capabilities, and proficiency in recognizing opportunities for competitive advantage [8]. The authors of [8] characterize them as performance-oriented, visionary, confident, persuasive, inspirational, and effective in team building. The authors of [7] assert that entrepreneurial leaders demonstrate innovation, intuition, and risk-taking while fostering collaboration and directing others toward common objectives.

Entrepreneurial leadership recognizes market opportunities, challenges the current quo, and innovates [1]. This leadership style empowers, accounts for, and empowers individuals to take charge of their tasks and help the company succeed [3]. Wealth, income, sustainability, job creation, and entrepreneurial pleasure are all part of entrepreneurial success [52,59]. By improving competitiveness, resilience, and innovation, entrepreneurial leadership helps organizations gain market share [85]. Resource-based entrepreneurial leadership [31] generates success for small and medium firms as a strategic managerial resource. We may thus hypothesize the following:

H1:

Entrepreneurial leadership positively influences entrepreneurial success.

2.5.2. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Team Diversity

Team formation for a business significantly impacts team performance and entrepreneurial success [86]. Teams with diverse skills, knowledge, experiences, and perspectives can drive innovation, adaptability, and growth for firms [61,62]. These diverse characteristics of the team bring positive individual, team, and organizational outcomes [19,20]. Because of these positive outcomes, entrepreneurial leadership strives to develop diversified teams that have the potential to bring innovation, creativity, problem-solving, and risk-taking ability [86,87] that can further lead to entrepreneurial success [88].

Leadership with entrepreneurial orientations can recognize gender, ethnic, economic, psychological, sociological, and cultural differences at the workplace for team formation [89] and use these diverse skills, experiences, and perspectives to promote the development and growth of the firm [90,91]. Studies suggest that national diversity [63] and gender and cultural diversity [86] bring innovation and creativity to firms that, in turn, promote growth and development [87,88]. Based on resource-based theory [31], entrepreneurial leadership encourages growth, innovation, and adaptation by integrating multiple viewpoints, experiences, and talents. In light of this, we postulate the following hypothesis:

H2:

Entrepreneurial leadership positively influences team diversity.

2.5.3. Team Diversity and Entrepreneurial Success

There is a growing debate over the effectiveness of team diversity for firm performance and success. Team diversity refers to differences in individual attributes, leading to a sense that one individual is different from the other based on these attributes [92]. The authors of [92] reported that diversity may encompass age, gender, ethnicity, race, tenure, academic background, and functional background. Studies have reported diverse effects of team diversity on entrepreneurial performance, ranging from positive to insignificant impacts [93]. The authors of [93] identified three broader sources of diversity: human capital, social capital, and demographic diversity, which bring different costs and benefits. However, many studies on diversity and firm performance have reported a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial performance due to team diversity, which leads to synergy [94]. Studies further suggest that diversity management practices spur teams to assimilate various perspectives and information that enhance entrepreneurial performance [95,96].

Studies on the relationship between team diversity and firm performance [94] reported that entrepreneurial success is predicted mainly by team composition. Teams with diverse human capital, social capital, and demographic characteristics offer innovative and creative solutions to organizational problems, fostering entrepreneurial success [93]. Further, team diversity coupled with entrepreneurial leadership drives the organization towards competitiveness, resilience, innovation, higher, improved accuracy in risk assessment, and increased productivity [85]. We may understand the relationship between team diversity and entrepreneurial success from the theoretical perspective of resource-based theory. RBT offers insight into how firms may leverage diversity as a competitive advantage to foster entrepreneurial success by considering how diverse teams contribute to organizational resources regarding mobility, complementarity, and heterogeneity. We may hypothesize the following:

H3:

Team Diversity has a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial success.

2.5.4. Team Diversity as Moderator of Entrepreneurial Leadership and Entrepreneurial Success Relation

Organizations strive to seek growth and development and maximize profit through the influential role of leadership [97]. Leaders characterized by innovation, creativity, challenging the status quo, and risk-taking can effectively manage scarce organizational resources to seek opportunity and advantage strategically [8]. Leaders exhibiting these characteristics are regarded as entrepreneurial leaders [91]. Studies suggest that organizations driven by entrepreneurial leaders display higher levels of market responsiveness, innovation, and creativity, which determine entrepreneurial success [53].

Team formation is also pivotal in driving organizations toward success and growth [94]. Entrepreneurial leaders form teams possessing diverse age groups, gender differences, different ethnic orientations, diverse work experiences, and academic backgrounds [64]. These diverse teams bring innovation, growth, and competitiveness [18,85]. It suggests that entrepreneurial leadership and team diversity complement each other, and entrepreneurial leadership coupled with team diversity may foster entrepreneurial success [88]. The moderating role of team diversity entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success association can be explained through resource-based theory. RBT offers essential insights into how team diversity can foster entrepreneurial leadership’s influence on entrepreneurial success by considering how diverse teams contribute to organizational resources regarding heterogeneity, complementarity, and mobility. Drawing upon RBT, we may hypothesize the following:

H4:

Team diversity moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success.

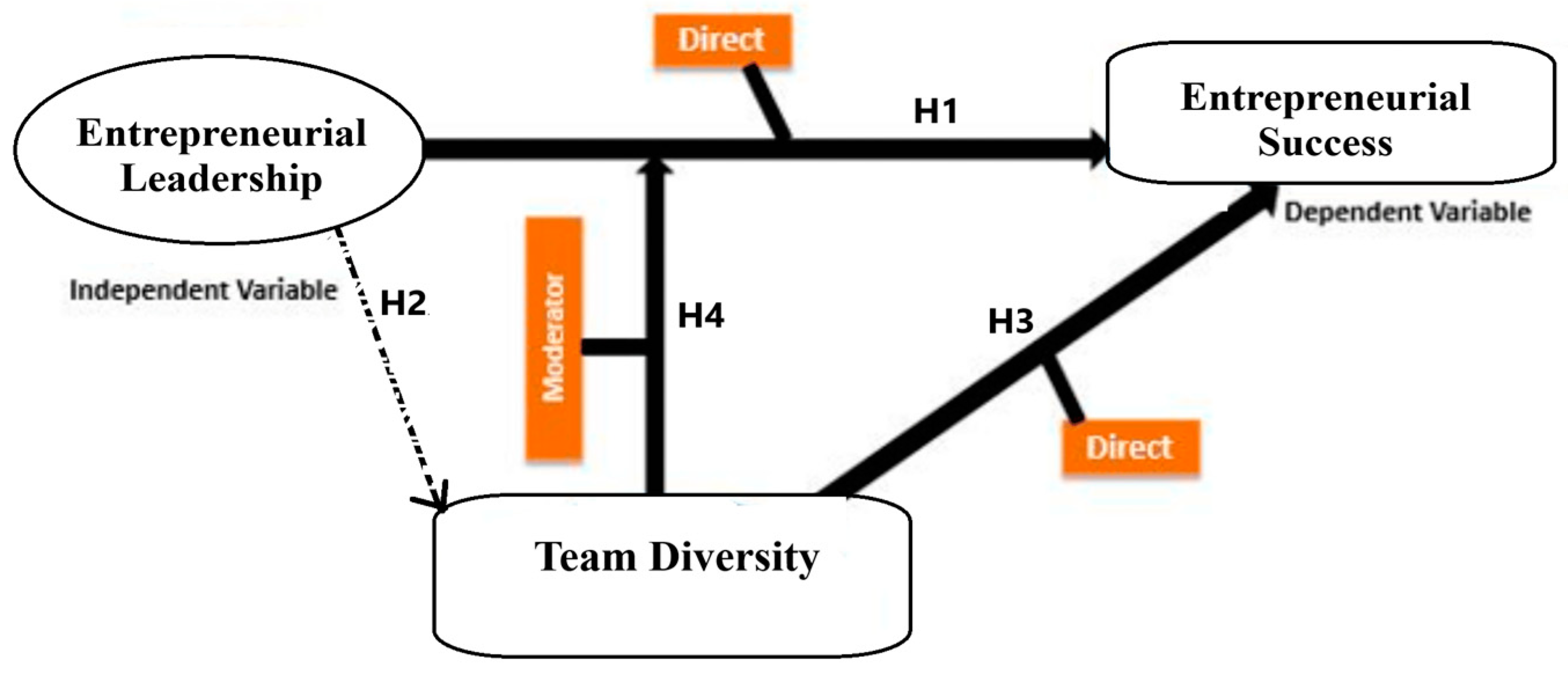

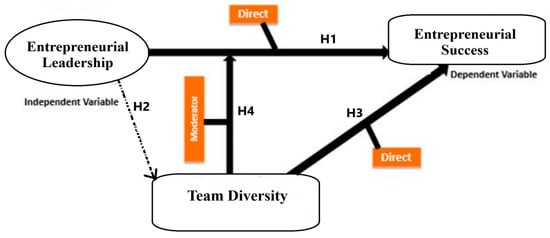

2.6. Proposed Model

A pictorial representation of the conceptual framework of this study is presented in Figure 1. The model in this study comprises three constructs. EL, ES, and TD are independent, dependent, and moderating variables, respectively.

Figure 1.

Moderating the role of team diversity between EL and ES.

2.7. Operational Definitions of the Research Concepts

Table 1 below presents the operational definitions of all the variables understudy.

Table 1.

Operational definitions.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedure

This study examined the synergy between entrepreneurial leadership and team diversity as a pathway to entrepreneurial success in SMEs in Pakistan, as depicted in Figure 1. To ensure industry representation, data were collected from SME owners, managers, and supervisors in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Pakistan. Ethical approval for this study was granted on 17 July 2024, by the SMEDA KP Ethical Committee under reference number 360-364/SMEDA, with Asim Rashid serving as the Independent Review In-Charge. The population of this study comprised employees working in 2870 small and medium enterprises in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Since the population of this study was scattered and large in number, it was hardly possible to reach each respondent. Hence, the non-probability convenience sampling technique was employed following the prior research [98,99], particularly in the business context [100]. Further, we employed a convenience sampling technique due to the lack of a database or record of the workforce of SMEs in KP, Pakistan. The formula n = N/(1 + N(e)2) was used to determine the sample size (n). The population size (N) was 2870, and the sample size (n) was 350 at 0.05 (e), as per [100,101]. Hence, to collect data for this study, 400 questionnaires were distributed among SMEs in KP, 370 of which were deemed valid for analysis. Ultimately, 350 responses were included in the final dataset, representing a response rate of 87.5%. Regarding demographics, most respondents were male (277 participants, 79.14%) and 73 were female (20.85%). In terms of educational qualifications, 134 respondents (38.3%) held a bachelor’s degree, 68 (19.4%) held a master’s degree, and 38 (10.9%) held a postgraduate degree (master’s degree and above). When analyzing work experience, the largest group of respondents (41.7%) had one to five years of experience, indicating that a significant portion of participants were relatively new to their professional roles. The second-largest group (24.9%) had 6–10 years of experience, whereas 21.7% had worked for 11–15 years. Only 11.7% of the respondents had more than 15 years of experience, indicating that highly experienced professionals formed a minor portion of the dataset.

3.2. Measures

Data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire that measured the demographics of the respondents, entrepreneurial leadership, entrepreneurial success, and team diversity. The questionnaire is attached as Appendix A for more elaboration on the items used in the current study.

3.2.1. Entrepreneurial Leadership Scale (ELS)

Entrepreneurial leadership was measured using the (ELS) developed by [39,102] to assess entrepreneurial leadership. ELS contains ten (10) self-report items, with responses ranging from one (Strongly Disagree) to seven (Strongly Agree). All participants completed the items, and the total ELS score was calculated by summing the scores of all items. The developers established the scale’s internal consistency and validity [39,102]. The ELS demonstrated high reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.90.

3.2.2. Entrepreneurial Success Scale (ESS)

Entrepreneurial success was measured using the Entrepreneurial Success Scale (ESS) [9,103], which includes seven (07) self-report items assessed on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). All participants responded to each item and the total ESS scores were calculated by aggregating the item responses. The scale’s psychometric properties, such as internal consistency and validity, were validated by its developers [9,103]. The current study found that the ESS exhibited high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92.

3.2.3. Team Diversity Scale (TDS)

The operationalization of team diversity utilized the Team Diversity Scale (TDS) [104,105], which consists of eight (08) self-report items assessed on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). All participants responded to each item, and the total TDS scores were calculated by aggregating all item responses. The developers confirmed the reliability and validity of the scale [104,105]. The TDS demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.84.

3.3. Data Analysis

The data collected in this study were analyzed using various statistical tools, such as descriptive statistics, normality assessments (skewness–kurtosis values within ±1.5) [106], and tests for reliability and validity. Collinearity diagnostics using variance inflation factors (VIFs) followed the threshold established by [107], with all constructs falling between 1.21 and 2.93, indicating the absence of multicollinearity (SPSS v26). The moderation effects were analyzed using SMART-PLS. Data collection procedures were also examined for common method bias (CMB) to assess data variation [108]. The CMB test employs Harman’s single-factor test, utilizing exploratory factor analysis of all construct items included in the study. Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first factor accounted for approximately 22.2% of the variance in the study data, below the 50% threshold established in [108], suggesting that common method bias (CMB) is not present in the study data.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability Analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive analysis of three key variables: team diversity (TDI), entrepreneurial leadership (ENLD), and entrepreneurial success (ESC). The mean values indicate that respondents rated entrepreneurial leadership (4.65) as the highest, followed by team diversity (4.40), and entrepreneurial success (4.30). The median values were close to their respective means, suggesting that the data distributions were fairly symmetrical, with no extreme skewness. However, the standard deviations revealed that ENLD (1.714) had the highest variability, indicating a wider spread of responses compared with TDI (1.077) and ESC (1.359), where responses were relatively more consistent. Examining skewness, all three variables had negative skewness (TDI, −0.331; ENLD, −0.366; ESC, −0.622), meaning that responses were slightly skewed to the left, suggesting that more participants provided higher ratings for these variables. In addition, the kurtosis values indicate the shape of the distribution, which has a high kurtosis (2.61), indicating a peaked distribution and that the responses were concentrated around the mean. Conversely, ENLD (−0.560) and ESC (−0.984) exhibit negative kurtosis, suggesting a flatter and more widely spread distribution.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis.

Furthermore, the minimum and maximum values indicated that all variables were measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7, with the full scale utilized by the respondents. Finally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were examined to assess multicollinearity. TDI (1.035) and ENLD (1.032) had low VIF values, suggesting that these variables were not highly correlated. However, ESC (2.764) had a slightly higher VIF, indicating a moderate correlation with one or more independent variables but still within an acceptable range (VIF < 5). The VIF values confirm no serious multicollinearity issues, ensuring that the variables can be reliably used in further statistical modeling.

4.2. Principal Component Analysis

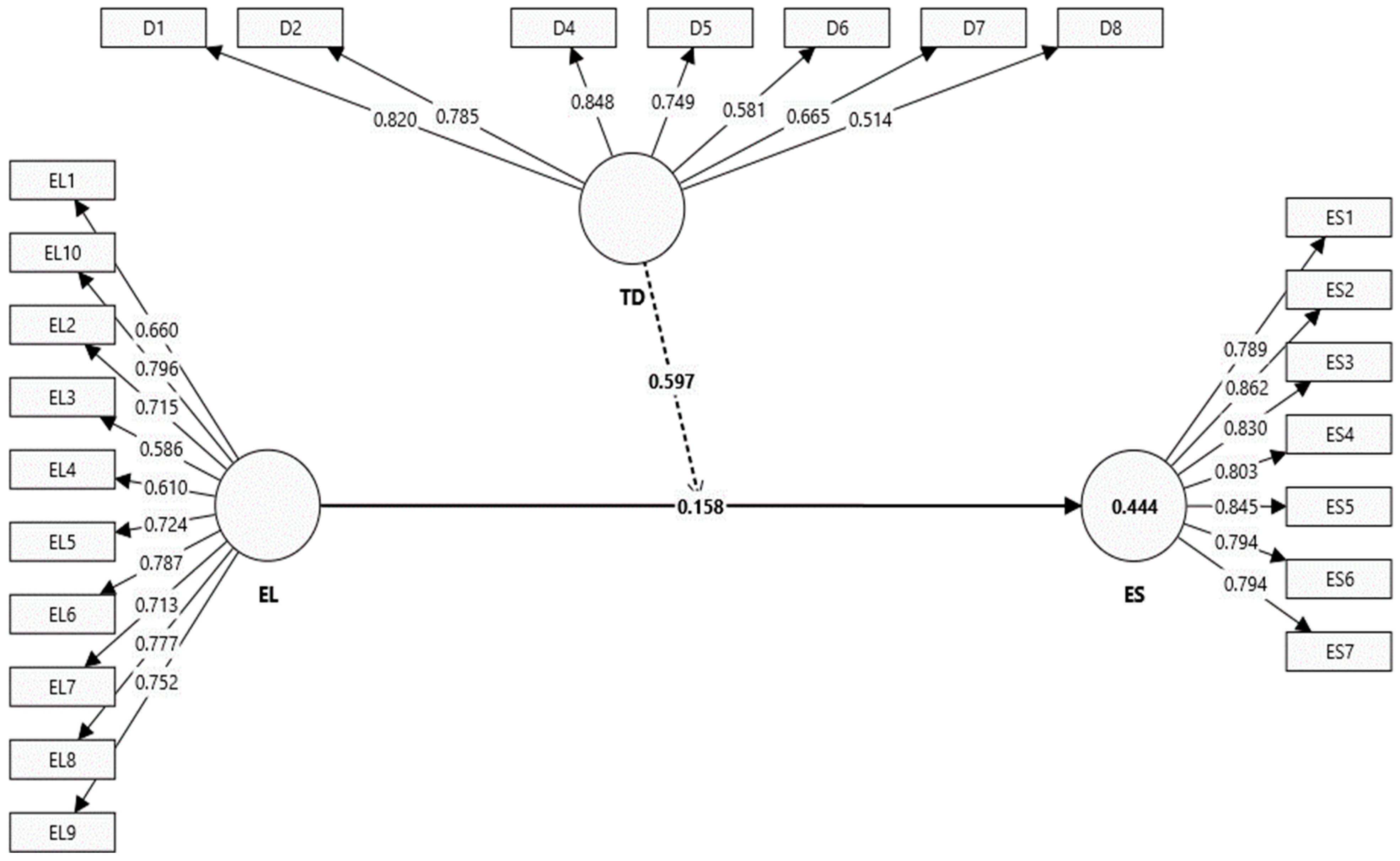

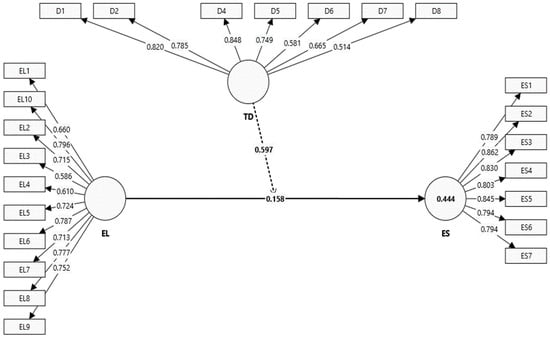

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to evaluate the factorability of the constructs. The threshold value of outer loading to represent factorability must be greater than 0.50. It is evident from Table 3 that all of the entrepreneurial leadership, team diversity, and entrepreneurial success items have outer loadings greater than 0.50, showing high factorability [109]. However, ES8 and ES9 for entrepreneurial success and TD3 for team diversity had factor loadings of less than 0.50. Thus, these items were deleted, retaining all other items with a good factorability greater than 0.50. A further explanation of the outer loadings is presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Factor loadings, reliability, and AVE.

Figure 2.

Factor Loadings.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

Table 4 depicts the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio and the Fornell–Larcker criterion used to evaluate discriminant validity. The results in Table 3 suggest that all the HTMT values were below the recommended threshold of 0.85 [105], indicating that the constructs are distinct (EL and ES = 0.222 < 0.85, EL and TD = 0.271 < 0.85, ES and TD = 0.21 < 0.85). Furthermore, the interaction term TD × EL also exhibited low HTMT ratios with EL (0.063), ES (0.664), and TD (0.126), further supporting the discriminant validity. It is also evident in Table 3 that the square root of AVE was more significant than the correlations between the constructs. All diagonal values were more substantial than the inter-construct correlations, indicating empirical distinctness.

Table 4.

HTMT ratios and Fornell–Larcker criterion.

4.4. Model Fitness

Table 5 presents the model fit indices for the saturated and estimated models. The SRMR values for the saturated model (SRMR = 0.067) and the estimated model (SRMR = 0.066) indicate an acceptable model fit [110]. Furthermore, the squared Euclidean distance (d_ULS) values for the saturated model (1.356), estimated model (1.323), and geodesic discrepancy (d_G) values for the saturated (0.426) and estimated models (0.422) suggest minimal discrepancies. The Chi-square values for the saturated model (834.758) indicate a better fit than the saturated model (821.293). Moreover, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) values for the saturated (NFI = 0.818) and estimated (NFI = 0.82) models indicate a moderate level of model fit, as values approaching 0.90 are considered satisfactory [110].

Table 5.

Model fitness.

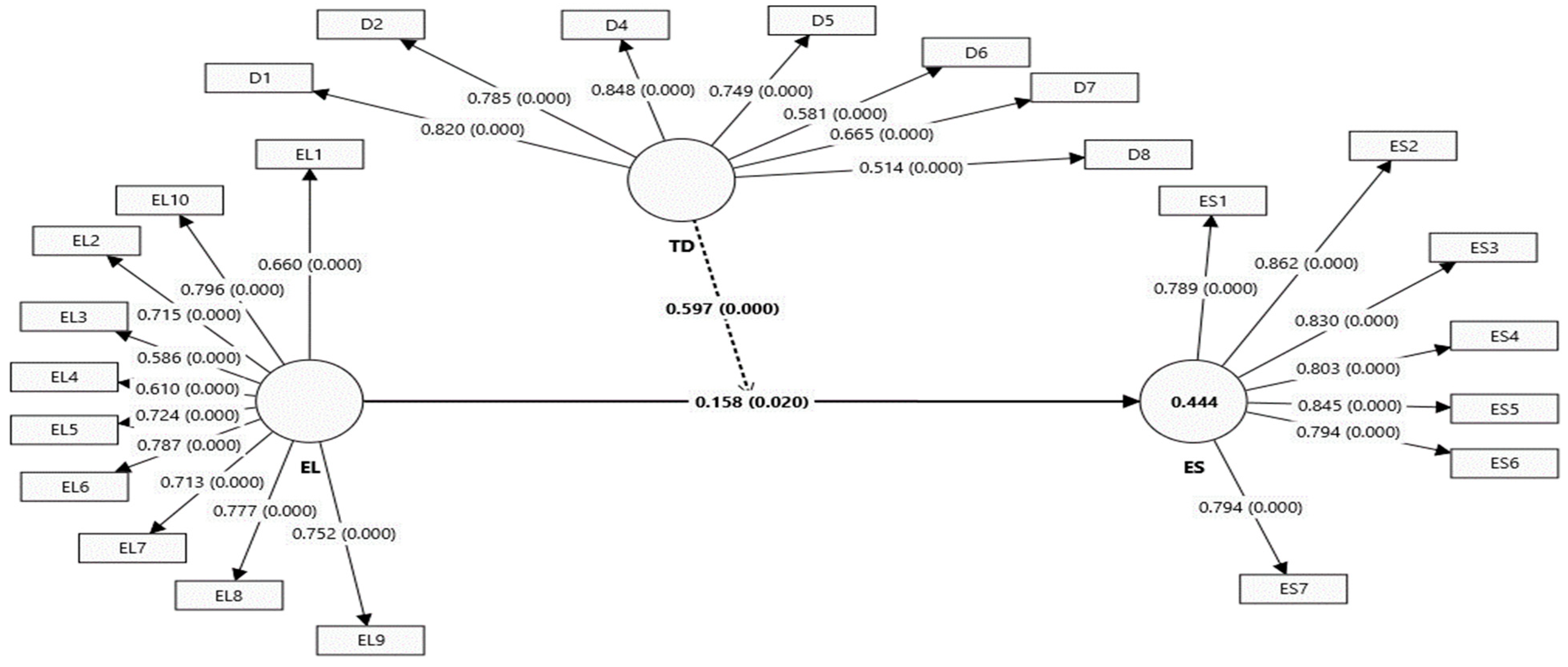

4.5. Moderation Results

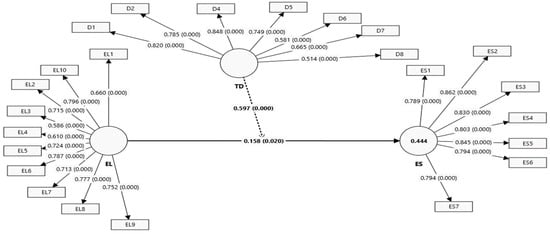

Table 6 and Figure 3 illustrate the structural equation modeling analysis using SMART PLS to examine the relationships among entrepreneurial leadership (EL), entrepreneurial success (ES), and team diversity (TD). The results revealed that ES was significantly predicted by EL (β = 0.158, t = 2.335, p = 0.020). The coefficient estimate for EL is 0.158, suggesting that an increase of one unit of entrepreneurial leadership corresponds to a 0.158 unit increase in entrepreneurial success while controlling for other variables. Similarly, the results show that EL was statistically positively impacted by TD (β = 0.162, t = 3.470, p = 0.001), which indicates that a one-unit change in EL will result in a 0.162 unit increase in TD. Furthermore, results also revealed that team diversity did not significantly affect ES (β = 0.085, t = 1.260, p = 0.028). The coefficient estimate for TD is 0.085, which suggests that an increase of one unit of team diversity corresponds to a 0.085 unit increase in entrepreneurial success while controlling for other variables. The interaction term (TD × EL) demonstrated a strong and significant effect on ES (β = 0.597, t = 7.166, p < 0.001), highlighting the moderating role of team dynamics in the relationship between EL and ES”. Hence, Table 6 shows that all proposed hypotheses were tested and accepted, including the moderation hypothesis.

Table 6.

Moderation analysis.

Figure 3.

Moderation path.

Figure 3 depicts the predictive ability of entrepreneurial leadership and team diversity for entrepreneurial success. Although the individual effects of entrepreneurial leadership and team diversity on entrepreneurial success are significant and positive; their collective effect becomes manifold in fostering entrepreneurial success.

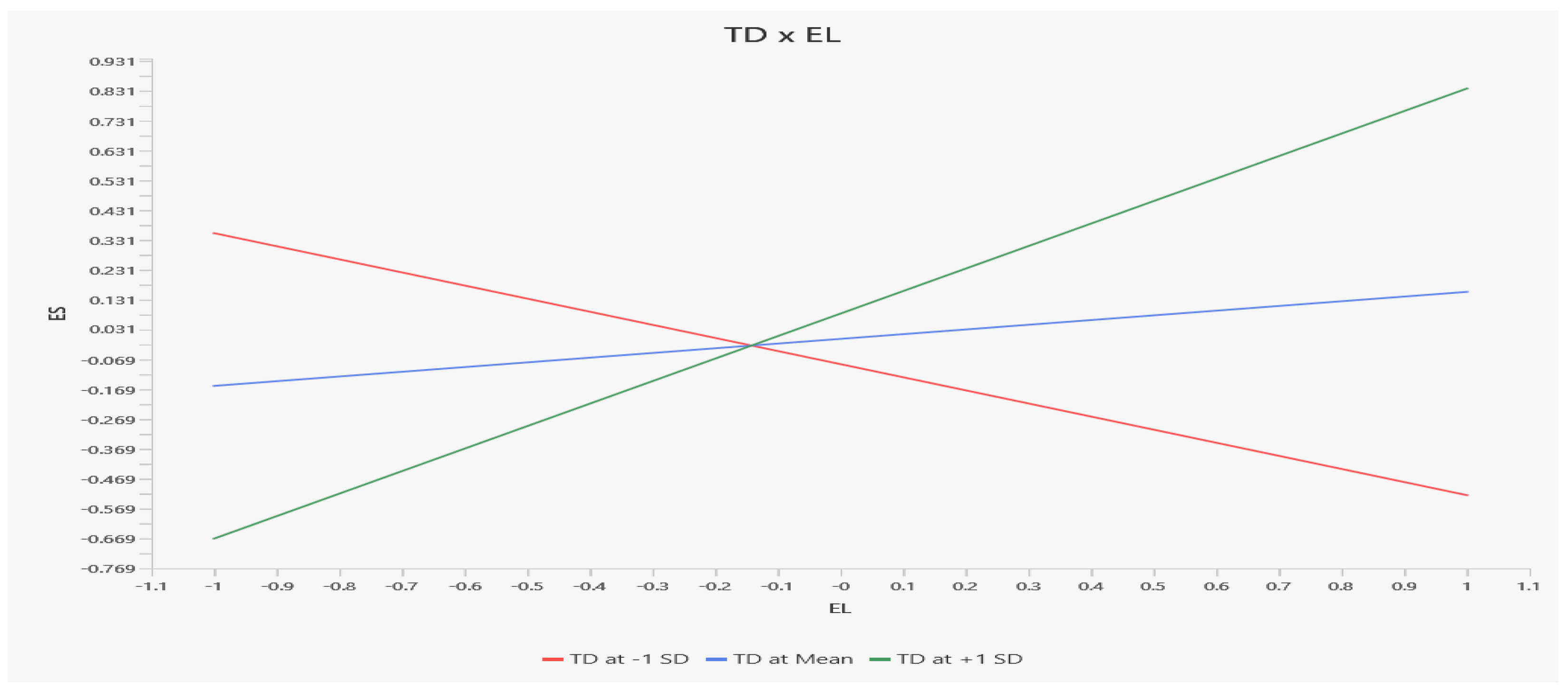

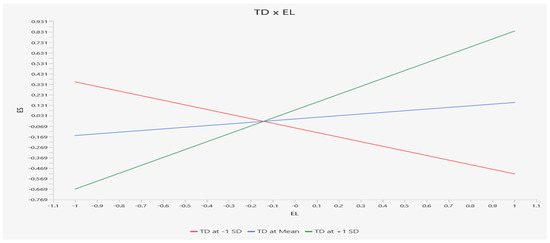

In a simple slope estimation analysis (Figure 4), the focus is on understanding how the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership (ENLD) and entrepreneurial success (ESC) varies at different levels of the moderating variable, team diversity (TDI). Table 7 provides estimates of the slope of the regression line between ENLD and ESC at three different levels of TDI: low (−1SD), average, and high (+1SD). At a low level of team diversity, the slope estimate for the relationship between ENLD and ESC is 0.1561, indicating that an increase in one unit of entrepreneurial leadership corresponds to 0. 1561 units of increase in entrepreneurial success at this level of team diversity. The standard error (SE) associated with this estimate was 0.0589, which provides a measure of slope precision. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the slope ranged from 0.0819 to 0.1103. A T-value of 3.6151 for this slope at a significance level of p < 0.001 indicates a significant and positive relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success when team diversity is low. At the average level of team diversity, the slope estimate remains consistent at 0.2065, suggesting that one one-unit increase in entrepreneurial leadership corresponds to a 0.2065-unit increase in entrepreneurial success at this level of team diversity. The standard error (SE) associated with this estimate is 0.0412. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the slope ranged from 0.1255 to 0. 2876. A T-value of 5.108 for this slope, significant at p < 0.001, indicated a significant and positive association between entrepreneurial and entrepreneurial success at the average level of team diversity. At a high level of team diversity, the slope estimate for the association between entrepreneurial success and entrepreneurial success increases to 0.9791. This suggests that an increase of one unit in entrepreneurial leadership corresponds to 0.9791 units of increase in entrepreneurial success at this level of team diversity. The standard error (SE) associated with this estimate is 0.0568. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the slope ranged from 0.8674 to 1.0909. The T-value for this slope is 17.2313, which is highly significant at p < 0.001 and suggests a significant and positive relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success when team diversity is high. Hence, the simple slope estimation reveals that the positive relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success is significant across all levels of team diversity, with more substantial effects observed at higher levels of team diversity.

Figure 4.

Simple slope analysis.

Table 7.

Simple slope estimation.

5. Discussion

This study elucidates the critical roles of entrepreneurial leadership (ENLD) and team diversity (TDI) in driving entrepreneurial success (ESC), analyzed using the resource-based view (RBV) framework. Empirical findings affirm ENLD as a pivotal resource, evidenced by a significant positive coefficient (β = 0.158), aligning with RBV’s assertion that unique and valuable resources, such as leaders’ strategic vision, risk-taking aptitude, and capacity to inspire innovation to enhance competitive advantage and performance [7,32,53].

Similarly, TDI demonstrated a positive association with ESC (β = 0.085), corroborating its value as a strategic resource. Diverse teams enhance problem-solving, adaptability, and innovation, bolstering organizational resilience in dynamic markets [56,80]. RBV principles further posit that such resources sustain competitive differentiation when scarce and non-substitutable [18,110]. While making a comparison of entrepreneurial leadership and its relationship with team diversity in Pakistan and Germany, we found that Pakistani entrepreneurs appeared more supportive of diverse teams [110]. The interaction effect between ENLD and TDI (β = 0.597) underscored their synergistic impact on ESC. Entrepreneurial leaders adeptly leveraging diverse team competencies amplify creativity and strategic decision-making, aligning with the RBV’s emphasis on resource interplay to maximize competitive outcomes [19,93]. These findings underscore the necessity of integrating ENLD and TDI to navigate market complexities, exploit emerging opportunities, and sustain long-term competitive advantages. Moreover, organizations prioritizing ENLD development and fostering inclusive and diverse teams are poised to achieve superior innovation and performance in globalized, uncertain environments. This synergy aligns with the RBV’s theoretical tenets of the RBV, offering actionable insights into entrepreneurial strategy. At the practical frontiers, policymakers may devise policies in light of the findings of the study that may involve committing funds for the training and development of SME leaders. Similarly, practitioners may develop actionable strategies to leverage diversity for innovation to gain a competitive advantage for SMEs. This study suggests that enhanced entrepreneurial leadership (EL) aimed at assisting SME owners, managers, and supervisors in developing their ability to spot opportunities and foster team diversity (TD) significantly impacts entrepreneurial success (ES). The research indicates that all hypotheses are accepted and aligned with the study objectives.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical insights into the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership, team diversity, and entrepreneurial success in the context of SMEs in Pakistan, analyzed through a resource-based framework. ENLD serves as a crucial driver of ESC, with entrepreneurial leaders demonstrating proficiency in strategic resource allocation, fostering environments conducive to innovation, and implementing data-driven decisions. These practices align with RBV principles, positioning leadership as a unique, value-generating resource. TDI exhibited a strong positive correlation with ESC, highlighting its function as a catalyst for innovation. Diverse teams utilize varied expertise and perspectives that improve creative problem-solving, adaptability, and performance, which are essential characteristics of a resource aligned with the resource-based view (RBV).

The analysis demonstrated a synergistic interaction between ENLD and TDI, which enhanced ESC outcomes. The resource-based view posits that strategic complementarity, which integrates leadership skills with varied team competencies, results in non-substitutable organizational assets. This synergy improves resilience in dynamic markets, thus allowing firms to surpass their competitors. However, SMEs should prioritize the development of ENLD and the promotion of TDI as essential strategic imperatives. Integrating these resources enables firms to unlock innovation potential, maintain competitive differentiation, and succeed in complex globalized business ecosystems.

7. Implications

Both the theory and practice of entrepreneurship can benefit significantly from this study’s findings. Theoretically, it contributes to the resource-based view (RBV) by explaining how diverse teams and entrepreneurial leadership (ENLD) work together as complementary strategic assets to boost ESC. The findings expand the application of RBV to unpredictable, dynamic markets by showing how they work together to drive innovation, optimize resources, and differentiate competitively. These findings have practical implications for both business owners and executives. Encouraging strategic risk-taking, motivational acuity, and innovation-centric decision-making, entrepreneurial leadership helps businesses make the most of limited resources. Simultaneously, encouraging diverse skill sets, viewpoints, and experiences within teams improves their ability to adapt, solve problems, and innovate. Together, these tactics build a culture that is capable of thriving in volatile markets. The combination of ENLD and TDI proves to be an irreplaceable benefit, highlighting the need to combine diversity and leadership development programs to maintain performance and market relevance in the long run.

8. Limitations and Recommendations

Based on a detailed discussion of the results, this study had several limitations. First, the data were collected from selected SMEs in the KP province of Pakistan, which does not represent the entire country. Therefore, future researchers should consider gathering data from other provinces and comparing the results to validate the model in more detail. Secondly, in the current study, data were collected through a questionnaire at one stage, leading to statistical issues. Hence, future researchers should collect data at different intervals to better understand team diversity dynamics in entrepreneurial work structures. Another limitation of this study was the use of non-probability convenience sampling, which may cause issues of generalizability. Future researchers could employ probability sampling to obtain more generalizable results. This study uses team diversity as a potential moderator that may function as a resource for start-ups by creating a synergic effect with EL to foster the success of SMEs. However, future researchers can explore other factors such as organizational culture, knowledge sharing, technology management processes, green vision, and flextime attributes as potential mediators to gain a deeper understanding of entrepreneurial success. Finally, evidence [109] suggests that leadership is a mediating mechanism that transforms individual and organizational outcomes. Because of the smaller size of start-ups, the culture and value system of SMEs can affect their success [110]. However, this study did not consider these mediating mechanisms in the context of SMEs. Future researchers may address this gap by examining the mediating role of virtuous culture in this relationship to examine how EL transforms individual and organizational outcomes through virtuous culture.

Author Contributions

K.R.: conceptualization, methodology; K.B.L.: validation; S.F.Y.: formal analysis; M.A.U.: methodology, analysis; M.A.: validation, proofreading. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The department issued a letter of ethical approval on 17 July 2024, with reference No. 360-364/SMEDA, by Asim Rashid, who was in charge of the ethical committee in SMEDA, KP, Pakistan.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Code | Questions | Source |

| EL: Item1 | I can set high standards of performance. | [31,34] |

| EL: Item2 | I have a vision of the future and imagination. | |

| EL: Item3 | I predict potential future events. | |

| EL: Item4 | I can display and express powerful positive emotions for the work. | |

| EL: Item5 | I’m able to make transactions with others and negotiate effectively. | |

| EL: Item6 | Usually, I’m looking for continuous improvement in my performance. | |

| EL: Item7 | I may inspire other people’s feelings, convictions, values, and behaviors. | |

| EL: Item8 | I can make decisions firmly and quickly. | |

| EL: Item9 | I instill trust in others by putting faith in them. | |

| EL: Item10 | I always offer courage, confidence, or hope through reassuring and advising. | |

| ES: Item1 | I feel like I run a successful business. | [6,106] |

| ES: Item2 | I can control my business. | |

| ES: Item3 | I can balance the work and family interface. | |

| ES: Item4 | Having pride in my job is more important than making lots of money. | |

| ES: Item5 | Giving the job to people gives me great satisfaction. | |

| ES: Item6 | My satisfaction is more important than making money. | |

| ES: Item7 | I am just as optimistic now as when I started the business. | |

| ES: Item8 | Having a flexible lifestyle is more important than making lots of money. | |

| ES: Item9 | Being my boss gives me more personal satisfaction. | |

| TD: Item1 | Our team comprises members from diverse backgrounds. | [100,101] |

| TD: Item2 | Diverse perspectives within our team enhance our problem-solving capabilities. | |

| TD: Item3 | We actively promote an inclusive work environment. | |

| TD: Item4 | Team diversity positively impacts our innovation outcomes. | |

| TD: Item5 | We ensure equal opportunities for all team members regardless of their background. | |

| TD: Item6 | Our diverse team improves our understanding of different markets and customers. | |

| TD: Item7 | We have diversity and inclusion policies in place. | |

| TD: Item8 | We celebrate cultural differences within our team. | |

| TD: Item9 | Our team diversity helps us to attract a wider talent pool. | |

| TD: Item10 | We believe that diversity drives innovation and creativity. |

References

- Nguyen, P.V.; Huynh, H.T.N.; Lam, L.N.H.; Le, T.B.; Nguyen, N.H.X. The impact of entrepreneurial leadership on SMEs’ performance: The mediating effects of organizational factors. Heliyon 2021, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mubashar, A.; bin Tariq, Y. Capital budgeting decision-making practices: Evidence from Pakistan. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 16, 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Chaudhry, S.; Amber, H.; Shahid, M.; Aslam, S.; Shahzad, K. Entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ proactive behaviour: Fortifying self determination theory. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.A.; Khan, R.S.; Khan, M.R. Identifying prosperity characteristics in small and medium-sized enterprises of Pakistan: Firm, strategy and characteristics of entrepreneurs. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2024, 18, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.S. Surviving the Storm: The Vital Role of Entrepreneurs’ Network Ties and Recovering Capabilities in Supporting the Intention to Sustain Micro and Small Enterprises. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma Sonmez Cakir, Z.A. Analysis of Leader Effectiveness in Organization and Knowledge Sharing Behavior on Employees and Organization. SAGE Open 2020, 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Li, B. Entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success: The role of knowledge management processes and knowledge entrepreneurship. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 829959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, S. Entrepreneurial leadership: A review of measures, antecedents, outcomes and moderators. Asian Soc. Sci. 2018, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Maritz, A.; Lobo, A. Evaluating entrepreneurs’ perception of success: Development of a measurement scale. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2014, 20, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Sirmon, D.G. A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 963–989. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, D.J.; Puffer, S.M.; Darda, S.V. Convergence in entrepreneurial leadership style: Evidence from Russia. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2010, 52, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, P. Centralization and innovation performance in an emerging economy: Testing the moderating effects. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaech, S.; Baldegger, U. Leadership in start-ups. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaei, N.; Rezaei, S. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: An empirical investigation among ICT-SMEs. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1663–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E.I.; Khapova, S.N.; Bossink, B.A. Does entrepreneurial leadership foster creativity among employees and teams? The mediating role of creative efficacy beliefs. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, S.A.; Marshall, M.; Sherbin, L. How diversity can drive innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, G.H.L.; Chen, T.; Leung, K. Team creativity/innovation in culturally diverse teams: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoss, S.; Urbig, D.; Brettel, M.; Mauer, R. Deep-level diversity in entrepreneurial teams and the mediating role of conflicts on team efficacy and satisfaction. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 18, 1173–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.; Cardon, M.S. What’s love got to do with it? Team entrepreneurial passion and performance in new venture teams. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 475–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshanty, A.M.; Emeagwali, O.L. Market-sensing capability, knowledge creation and innovation: The moderating role of entrepreneurial-orientation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Ibrahim, M.D.; Yusoff, M.N.H.B.; Fazal, S.A. Entrepreneurial leadership, performance, and sustainability of micro-enterprises in Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwi Widyani, A.A.; Landra, N.; Sudja, N.; Ximenes, M.; Sarmawa, I.W.G. The role of ethical behavior and entrepreneurial leadership to improve organizational performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1747827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K.F.; Nazeer, A.; Shahzad, F.; Ullah, M.; Imranullah, M.; Sahibzada, U.F. Impact of entrepreneurial leadership on project success: Mediating role of knowledge management processes. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, T.S.; Hashim, N.; Zakaria, N. Entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success: The mediating role of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition and innovation capability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniewski, M.W.; Awruk, K. Entrepreneurial success and achievement motivation—A preliminary report on a validation study of the questionnaire of entrepreneurial success. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaniago, H. Investigation of entrepreneurial leadership and digital transformation: Achieving business success in uncertain economic conditions. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2023, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Lim, K.B.; Yeo, S.F.; Saif, N.; Ameeq, M. The Nexus of Entrepreneurial Leadership and Entrepreneurial Success with a Mediation of Technology Management Processes: From the Perspective of the Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ding, D.; Chen, Z. Entrepreneurial leadership and performance in C hinese new ventures: A moderated mediation model of exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation and environmental dynamism. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchiri, M.; McMurray, A. Entrepreneurial orientation within small firms: A critical review of why leadership and contextual factors matter. Small Enterp. Res. 2015, 22, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.; Luu, T.T.; Babalola, M.T. Entrepreneurial leadership: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domańska, A.; Zajkowski, R. Barriers to gaining support: A prospect of entrepreneurial activity of family and non-family firms in Poland. Equilibrium. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2022, 17, 191–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Tang, J. The role of entrepreneurs in firm-level innovation: Joint effects of positive affect, creativity, and environmental dynamism. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Wieland, A.M.; Turban, D.B. Gender characterizations in entrepreneurship: A multi-level investigation of sex-role stereotypes about high-growth, commercial, and social entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, D.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Igartua, J.I.; Ganzarain, J. Business model innovation in established SMEs: A configurational approach. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Nelson, M.A. How do firms use innovations to hedge against economic and political uncertainty? Evidence from a large sample of nations. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M.; El Tarabishy, A.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brännback, M. Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.S.; Jian, Z.; Akram, U. Be so creative they can’t ignore you! How can entrepreneurial leader enhance the employee creativity? Think. Ski. Creat. 2020, 38, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, E.; Bonesso, S.; Gerli, F. Coping with different types of innovation: What do metaphors reveal about how entrepreneurs describe the innovation process? Creat. Innov. Manag. 2019, 28, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaniago, H. The effect innovation cloning to small business success: Entrepreneurial perspective. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, C.; Baron, R.A.; Barbieri, B.; Belanger, J.J.; Pierro, A. Regulatory modes and entrepreneurship: The mediational role of alertness in small business success. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J. Entrepreneurial Leadership: The Art of Launching New Ventures, Inspiring Others, and Running Stuff; HarperCollins Leadership: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson, Q.; Ryan, A.M.; Ragins, B.R. The evolution and future of diversity at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karar, W.; Alzubi, A.; Khadem, A.; Iyiola, K. The Nexus of Sustainability Innovation, Knowledge Application, and Entrepreneurial Success: Exploring the Role of Environmental Awareness. Sustainability 2025, 17, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, R.; Wang, Y.; Latif, K.F. The impact of entrepreneurial leadership on the project success: The mediating role of knowledge-oriented dynamic capabilities. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 1016–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rumman, A.; Al Shraah, A.; Al-Madi, F.; Alfalah, T. Entrepreneurial networks, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance of small and medium enterprises: Are dynamic capabilities the missing link? J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, B.; Bertoldi, B. The leadership style to lead the evolution of the entrepreneurial essence: A proposal. In Entrepreneurial Essence in Family Businesses: Continuity in Family Capitalism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 115–154. [Google Scholar]

- Arham, A.F.; Sulaiman, N.; Kamarudin, F.H.; Muenjohn, N. Understanding the links between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation in Malaysian SMEs. In The Palgrave Handbook of Leadership in Transforming Asia; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 541–558. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Ascalon, M.E.; Stephan, U. Small business owners’ success criteria, a values approach to personal differences. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, P.; Jenkins, A.; Stephens, A. Understanding entrepreneurial success: A phenomenographic approach. Int. Small Bus. J. 2018, 36, 611–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Chen, Y. Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial success—The role of psychological capital and entrepreneurial policy support. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 792066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.W.; Lee, Y.H. Effects of internal and external factors on business performance of start-ups in South Korea: The engine of new market dynamics. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 1847979018824231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstete, J.W. Aspects of entrepreneurial success. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.; McKelvie, A. What is entrepreneurial failure? Implications for future research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.; Wiklund, J. Are we comparing apples with apples or apples with oranges? Appropriateness of knowledge accumulation across growth studies. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Moss, T.W.; Gras, D.M.; Kato, S.; Amezcua, A.S. Entrepreneurial processes in social contexts: How are they different, if at all? Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.J. How women and men business owners perceive success. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wach, D.; Stephan, U.; Gorgievski, M. More than money: Developing an integrative multi-factorial measure of entrepreneurial success. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 1098–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, C.; Rickardsson, J.; Wincent, J. Diversity, innovation and entrepreneurship: Where are we and where should we go in future studies? Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C.; Lokshin, B.; Guenter, H.; Belderbos, R. Top management team nationality diversity, corporate entrepreneurship, and innovation in multinational firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, T.; Groeneveld, S.; Kuipers, B. The role of inclusive leadership in supporting an inclusive climate in diverse public sector teams. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2021, 41, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alang, T.; Stanton, P.; Rose, M. Enhancing employee voice and inclusion through inclusive leadership in public sector organizations. Public Pers. Manag. 2022, 51, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, A.M. Does workplace diversity matter? A survey of empirical studies on diversity and firm performance, 2000–2009. J. Divers. Manag. 2010, 5, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaean, F.A.; Ali, K.A.; Alenezi, A.A. Entrepreneurial leadership and organisational performance of SMEs in Kuwait: The intermediate mechanisms of innovation management and learning orientation. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 16, 459–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.S.; Kee, D.M.H.; Ramayah, T. The role of transformational leadership, entrepreneurial competence and technical competence on enterprise success of owner-managed SMEs. J. Gen. Manag. 2016, 42, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, Y.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The influence of entrepreneurial innovations in building competitive advantage: The mediating role of entrepreneurial thinking. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 4051–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Busenitz, L.W. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Awwad, R.I.; Albuhisi, B.; Hamdan, S. The Impact of Digital Transformation Leadership Competencies on Firm Performance Through the Lens of Organizational Creativity and Digital Strategy. In Innovative and Intelligent Digital Technologies; Towards an Increased Efficiency; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, I.; Zaman, U.; Waris, I.; Shafique, O. A serial-mediation model to link entrepreneurship education and green entrepreneurial behavior: Application of resource-based view and flow theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nor-Aishah, H.; Ahmad, N.H.; Thurasamy, R. Entrepreneurial leadership and sustainable performance of manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia: The contingent role of entrepreneurial bricolage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Hann, I.-H. Crowdfunding and the democratization of access to capital—An illusion? Evidence from housing prices. Inf. Syst. Res. 2019, 30, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.J.; Rodrigo-Moya, B.; Morcillo-Bellido, J. The effect of leadership in the development of innovation capacity: A learning organization perspective. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaluz, V.C.; Hechanova, M.R.M. Ownership and leadership in building an innovation culture. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Audretsch, D.; Aparicio, S.; Noguera, M. Does entrepreneurial activity matter for economic growth in developing countries? The role of the institutional environment. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1065–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A.; Frikha, M.A.; Bouraoui, M.A. An empirical investigation of factors affecting small business success. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.; Fontana, A. Entrepreneurial leadership measurement validation in innovation management. In ISPIM Innovation Symposium; The International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM): Porto, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, M.; Echambadi, R.; Venugopal, S.; Sridharan, S. Subsistence entrepreneurship, value creation, and community exchange systems: A social capital explanation. J. Macromarketing 2014, 34, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ahmad, I.; Ilyas, M. Impact of ethical leadership on organizational safety performance: The mediating role of safety culture and safety consciousness. Ethics Behav. 2018, 28, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, L.E.; Bernet, P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2019, 111, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, M.; Miron-Spektor, E.; Agarwal, R.; Erez, M.; Goldfarb, B.; Chen, G. Entrepreneurial team formation. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.S.; Jian, Z.; Akram, U.; Tariq, A. Entrepreneurial leadership: The key to develop creativity in organizations. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbu, A.N.; de Jong, A.; Adam, I.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Afenyo-Agbe, E.; Adeola, O.; Figueroa-Domecq, C. Recontextualising gender in entrepreneurial leadership. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, C.M.; Volery, T. Entrepreneurial leadership: Insights and directions. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasheva, S.; Hillman, A.J. Integrating diversity at different levels: Multilevel human capital, social capital, and demographic diversity and their implications for team effectiveness. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Nishii, L.H.; Dwertmann, D.J. Synergy from diversity: Managing team diversity to enhance performance. Behav. Sci. Policy 2020, 6, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, R.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Batool, S.N.; Cheng, C.F.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurial team diversity and start-up growth in consulting and hospitality. Serv. Ind. J. 2024, 44, 1038–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbangula, D.K. An Assessment of How to Build a Diverse Entrepreneurial Leadership Team. In Transformational Concepts and Tools for Entrepreneurial Leadership; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. How leaders influence organizational effectiveness. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Harrison, C. Entrepreneurial leadership measurement: A multi-dimensional construct. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, M.J.; de Pablo, J.D.S. The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maznevski, M.L.; Gomez, C.B.; DiStefano, J.J.; Noorderhaven, N.G.; Wu, P.C. Cultural dimensions at the individual level of analysis: The cultural orientations framework. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2002, 2, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X. How to reduce the negative impacts of knowledge heterogeneity in engineering design team: Exploring the role of knowledge reuse. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; et al. Evaluation of formative measurement models. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentle, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speak, A.; Escobedo, F.J.; Russo, A.; Zerbe, S. Comparing Convenience and Probability Sampling for Urban Ecology Applications. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 2332–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Das, N.; Srivastava, N.K. A Structural Model Assessing Key Factors Affecting Women’s Entrepreneurial Success: Evidence from India. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 11, 122–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.; MacMillan, I.C.; Surie, G. Entrepreneurial Leadership: Developing and Measuring a Cross-Cultural Construct. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.; Brown, A. What Success Factors Are Important to Small Business Owners? Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, G.; Chinchanachokchai, S.; Wyland, R. The Influence Of Supervisor Undermining On Self-Esteem, Creativity, And Overall Job Performance: A Multiple Mediation Model. Organ. Manag. J. 2017, 14, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarria, D.M.; Reynolds, P.D. Cultural norms & business start-ups: The impact of national values on opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 417–437. [Google Scholar]

- Kineber, A.F.; Oke, A.; Hamed, M.M.; Alyanbaawi, A.; Elmansoury, A.; Daoud, A.O. Decision Making Model for Identifying the Cyber Technology Implementation Benefits for Sustainable Residential Building: A Mathematical PLS-SEM Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middermann, L.H.; Rashid, L. Cross-country differences in entrepreneurial internationalization tendencies: Evidence from Germany and Pakistan. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).