The Keywords in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Dictionary Construction Method Based on MNIR

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG Information Disclosure and ESG Evaluation

2.2. CSR Information Disclosure and Text Analysis Technology

2.3. Manipulative Behaviors in CSR Information Disclosure for Image Management

2.4. Summary

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Construction of CSR Dictionary

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Measurement of CSR Level Disclosed in Annual Report

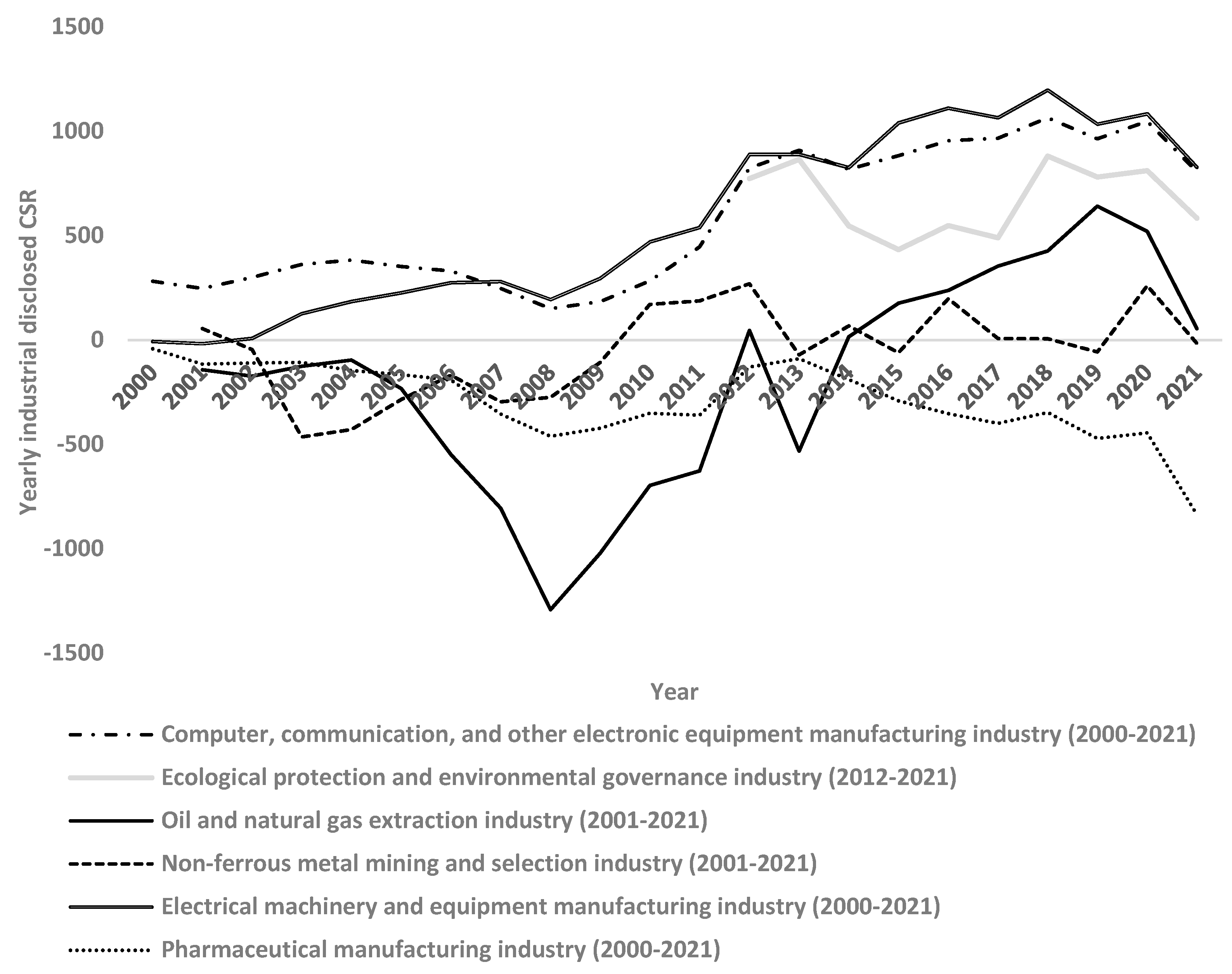

4.2. CSR Disclosure Levels in Different Industries

5. CSR Disclosure Level Manipulation and Corporate Performance

5.1. CSR Disclosure Levels and Corporate Business Performance

5.1.1. Business Performance and CSR Disclosure Levels of Listed Companies

- : the CSR level disclosed in the annual report of the company i in year t;

- : the return on common stockholders’ equity of the company i in year t;

- : the total assets of the company i at the end of the year t;

- : the book-to-market ratio of the company i in the current year t;

- : the asset–liability ratio of the company i in year t;

- : the dummy variable describing whether the company i is a state-owned enterprise; if the company i is a state-owned enterprise, is 1; otherwise, it is 0;

- : the number of years since the company was listed;

- : the dummy variable, which is 1 if the company i has refinancing activities, such as issuance or allotment, in the year t; otherwise, it is 0;

- : the dummy variable, which is 1 if the company i has merger and acquisition activities in the year t; otherwise, it is 0;

- : a random error term.

5.1.2. Stock Market Performance and CSR Disclosure Levels of Listed Companies

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3. Robustness Test

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, Social, Governance |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| MNIR | Multinomial inverse regression |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

Appendix A

| Chinese Meaning | Positive Words | CSR Score | Chinese Meaning | Negative Words | CSR Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 电气 | electric | 5.235439238 | 疫苗 | vaccine | −7.71509462 |

| 高速 | high speed | 4.318568245 | 灾区 | disaster area | −7.179618983 |

| 钢铁 | steel | 4.188377093 | 电器 | electrical appliances | −4.802384926 |

| 软件 | software | 4.031842191 | 地震 | earthquake | −4.4738809 |

| 风电 | wind power | 3.376950434 | 药材 | medicinal materials | −4.015034535 |

| 医学 | medicine | 3.190805375 | 气候 | climate | −3.886457005 |

| 发行人 | issuer | 3.074498056 | 黄金 | gold | −3.768210578 |

| 脱贫 | poverty alleviation | 3.014665613 | 压缩 | compression | −3.464121787 |

| 攻坚 | overcome difficulties | 3.012960829 | 数据安全 | data security | −3.340894219 |

| 零售 | retail | 2.981262624 | 药业 | pharmaceutical industry | −3.283041007 |

| 公路 | highway | 2.815950217 | 气候变化 | climate change | −3.240787006 |

| 养殖 | farming | 2.806286455 | 纺织 | textile | −3.196856468 |

| 深耕 | deep cultivation | 2.795730658 | 通讯 | communication | −3.038191147 |

| 精准 | precision | 2.786784954 | 家电 | household appliances | −2.899968794 |

| 期货 | futures | 2.779917025 | 相关者 | related | −2.767522357 |

| 智慧 | wisdom | 2.763927811 | 公用 | public | −2.669426796 |

| 信息技术 | information technology | 2.662733401 | 本年 | this year | −2.484712074 |

| 互联网 | internet | 2.605910892 | 导致 | lead to | −2.482753065 |

| 美好生活 | happy life | 2.549043123 | 住宅 | residential | −2.482325505 |

| 扶贫 | poverty alleviation | 2.47416871 | 质量体系 | quality system | −2.474943348 |

| 轨道 | track | 2.422596975 | 规程 | regulations | −2.362860274 |

| 担当 | responsibility | 2.403452417 | 中医 | traditional Chinese medicine | −2.337672092 |

| 美好 | happiness | 2.388326668 | 完全 | completely | −2.333481231 |

| 管理方 | management | 2.240577617 | 节约型 | economical | −2.302848075 |

| 微信 | 2.237766376 | 指数 | index | −2.302681481 | |

| 旅游 | travel | 2.184467708 | 用车 | car used | −2.246912144 |

| 农村 | rural | 2.139607259 | 高产 | high yield | −2.242926717 |

| 研究院 | research institute | 2.124480868 | 医药 | medicine | −2.23320935 |

| 混合型 | hybrid | 2.024685017 | 消耗量 | consumption | −2.220650247 |

| 电站 | power station | 2.012363127 | 多样性 | diversity | −2.181649171 |

| 程度 | degree | 2.005995303 | 药品 | drug | −2.166290704 |

| 集团股份 | group shares | 1.986376961 | 本年度 | this year | −2.10812581 |

| 核电 | nuclear power | 1.96536327 | 余额 | balance | −1.968834556 |

| 定点 | fixed point | 1.916647074 | 合力 | together | −1.965313924 |

| 村民 | villagers | 1.883146504 | 救灾 | provide disaster relief | −1.908607614 |

| 坚守 | persistence | 1.877955433 | 产业园 | industrial park | −1.899893345 |

| 物流 | logistics | 1.841692092 | 中小企业 | small and medium enterprises | −1.878214881 |

| 全力 | full strength | 1.836263167 | 制订 | formulate | −1.84898863 |

| 全文 | full text | 1.787563983 | 污水处理 | wastewater treatment | −1.825049104 |

| 集成 | integrated | 1.786948643 | 理财 | financial management | −1.814960992 |

| 农户 | farmers | 1.73209381 | 技术改造 | technological transformation | −1.799564969 |

| 密度 | density | 1.69604136 | 负面 | negative | −1.783265677 |

| 国民 | national | 1.668508337 | 应对 | response | −1.754587036 |

| 交付 | deliver | 1.660472001 | 信贷 | credit | −1.753646211 |

| 智能 | intelligent | 1.58711716 | 调动 | transfer | −1.729300953 |

| 智慧 | intelligence | 1.577688043 | 捐款 | donate | −1.727857134 |

| 交通 | transportation | 1.577470732 | 电机 | motor | −1.726174819 |

| 法定 | legal | 1.536588968 | 供电 | power | −1.686079805 |

| 定制 | customized | 1.525614599 | 反应 | reaction | −1.674140215 |

| 救援 | rescue | 1.518400963 | 资源管理 | resource management | −1.66270394 |

| 初心 | original intention | 1.5147728 | 电网 | power grid | −1.652139798 |

| 格局 | pattern | 1.506256902 | 可再生 | renewable | −1.63260363 |

| 装备 | equipment | 1.483119213 | 租赁 | lease | −1.62438176 |

| 贸易 | trading | 1.482684591 | 手册 | manual | −1.622114278 |

| 管理者 | manager | 1.479946536 | 集装箱 | container | −1.615096768 |

| 发行 | issue | 1.47400242 | 小企业 | small enterprise | −1.60364027 |

| 布局 | layout | 1.466328804 | 经济效益 | economic benefits | −1.602579394 |

| 备案 | record keeping | 1.464239793 | 贿赂 | bribe | −1.595138497 |

| 人才队伍 | talent team | 1.452235042 | 变化 | change | −1.594792147 |

| 机器 | machine | 1.424160186 | 集装 | container | −1.552403009 |

| 党建 | party building | 1.424049765 | 飞行 | flight | −1.548132863 |

| 智能化 | intelligent | 1.42349092 | 煤矿 | coal mine | −1.529039983 |

| 混合 | mix | 1.421668974 | 年末 | end of the year | −1.51947605 |

| 携手 | together | 1.41614985 | 产业化 | industrialization | −1.517209852 |

| 传真 | fax | 1.406796487 | 运动会 | sports day | −1.499248788 |

| 限制 | limit | 1.404025691 | 酒店 | hotel | −1.493249783 |

| 年报 | annual report | 1.395630486 | 颗粒 | particles | −1.485475375 |

| 驱动 | drive | 1.392494081 | 装箱 | packing | −1.482992508 |

| 食品 | food | 1.39211178 | 银行 | bank | −1.454710934 |

| 高端 | high-end | 1.378767854 | 成绩 | score | −1.448666348 |

| 管控 | control | 1.357585964 | 产品质量 | product quality | −1.444239237 |

| 招募 | recruit | 1.355006158 | 决议 | resolution | −1.441349353 |

| 董事长 | chairman | 1.341113336 | 机电 | electromechanical | −1.439061328 |

| 人才培养 | talent cultivation | 1.336835165 | 友好 | friendly | −1.438013934 |

| 成就 | achievement | 1.336359135 | 对待 | treat | −1.426744895 |

| 分公司 | branch company | 1.333035913 | 温室 | greenhouse | −1.415960231 |

| 共享 | shared | 1.316201207 | 失业 | unemployment | −1.413838158 |

| 整治 | remediation | 1.292765638 | 报道 | report | −1.361252413 |

| 引领 | leading | 1.261211558 | 纳入 | inclusion | −1.360754876 |

| 公司简介 | company profile | 1.259027855 | 安全性 | security | −1.349922064 |

| 玻璃 | glass | 1.252356052 | 绿化 | greenery | −1.347303739 |

| 巩固 | consolidation | 1.223588177 | 复合 | complex | −1.343295201 |

| 课程 | course | 1.222545597 | 改进 | improve | −1.338324651 |

| 走进 | walk In | 1.21809698 | 贷款 | loan | −1.337398592 |

| 股权 | equity | 1.217353564 | 恢复 | recover | −1.322558846 |

| 方法 | method | 1.210659292 | 认识 | know | −1.319240439 |

| 网络安全 | cybersecurity | 1.185770596 | 社会各界 | all sectors of society | −1.310332291 |

| 线上 | on-line | 1.185306121 | 资管 | asset management | −1.296790955 |

| 互助 | mutual aid | 1.18462562 | 煤炭 | coal | −1.293206767 |

| 水电 | hydropower | 1.179319635 | 隐私 | privacy | −1.285804709 |

| 线下 | offline | 1.178765283 | 验证 | verify | −1.279037251 |

| 前行 | forward | 1.177474256 | 气体 | gas | −1.278221291 |

| 民营 | private | 1.172704006 | 收到 | receive | −1.254791179 |

| 上线 | go online | 1.167276365 | 生物 | biology | −1.23726249 |

| 信息化 | informatization | 1.167190339 | 人类 | human | −1.216690483 |

| 美丽 | beauty | 1.16555521 | 重要性 | importance | −1.214642559 |

| 团结 | unity | 1.157273315 | 药物 | drug | −1.214220777 |

| 控股 | holdings | 1.156793755 | 房地产 | real estate | −1.212911453 |

| 生态 | ecology | 1.155717471 | 上升 | rise | −1.203963502 |

| 党员 | party member | 1.152104073 | 灾害 | disaster | −1.198699567 |

| 商品 | commodity | 1.137818037 | 空调 | air conditioner | −1.197820051 |

| 机械 | mechanical | 1.130983171 | 审查 | review | −1.195228368 |

| 突发 | Breakout | 1.12525412 | 工伤 | work Injury | −1.194543052 |

| 生日 | birthday | 1.119790528 | 污泥 | sludge | −1.193695314 |

| 公司党委 | company party committee | 1.119213065 | 石油 | oil | −1.193252988 |

| 说明会 | information session | 1.105299058 | 潜在 | potential | −1.192066283 |

| 照明 | illumination | 1.091045764 | 老年 | elderly | −1.177011474 |

| 特种 | special | 1.088996877 | 污水 | sewage | −1.165900041 |

| 动力 | power | 1.087753357 | 物料 | materials | −1.159721923 |

| 科创 | science and technology innovation | 1.078991901 | 重组 | reorganization | −1.159104657 |

| 民生 | people’s livelihood | 1.078636885 | 毕业生 | graduate | −1.152107048 |

| 大赛 | competition | 1.070134469 | 同业 | the same business | −1.144695682 |

| 便捷 | convenient | 1.065754865 | 容量 | capacity | −1.13984069 |

| 在线 | online | 1.060800044 | 循环 | cycle | −1.138923618 |

| 持有人 | owner | 1.060330434 | 生存 | survive | −1.135677755 |

| 地址 | address | 1.060316632 | 次数 | frequency | −1.12788152 |

| 最新 | up to date | 1.050588672 | 出行 | travel | −1.124480618 |

| 关键技术 | key technologies | 1.044356306 | 护工 | nursing | −1.123064083 |

| 联盟 | alliance | 1.038737996 | 努力实现 | strive to achieve | −1.112416804 |

| 实时 | real time | 1.033397023 | 商业道德 | business ethics | −1.111870477 |

| 梦想 | dream | 1.028255386 | 机遇 | opportunity | −1.111436176 |

References

- Godfrey, P.C.; Hatch, N.W. Researching Corporate Social Responsibility: An Agenda for the 21st Century. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Koelbel, J.F.; Pavlova, A.; Rigobon, R. ESG Confusion and Stock Returns: Tackling the Problem of Noise; National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; p. 30562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Chen, J.; Zhou, F.; Dong, Q.; He, Z. Corporate ESG and Resilience of Stock Prices in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2023, 79, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F. CSR Reporting Practices and the Quality of Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 33, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A.; Frost, T.; Cao, H. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure: A Literature Review. Br. Account. Rev. 2023, 55, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Makkar, B. CSR Disclosure in Developing and Developed Countries: A Comparative Study. J. Glob. Responsib. 2020, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Annual Report Readability, Current Earnings, and Earnings Persistence. J. Account. Econ. 2008, 45, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.; Kopytov, A.; Shen, L.; Xiang, H. On ESG Investing: Heterogeneous Preferences, Information, and Asset Prices; National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; p. 29839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; Gupta, S.; Mikalef, P. Exploring the Effect of Digital CSR Communication on Firm Performance: A Deep Learning Approach. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 176, 114047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, J. Analyzing and Visualizing Text Information in Corporate Sustainability Reports Using Natural Language Processing Methods. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, C. When Green Finance Meets Banking Competition: Evidence from Hard-to-Abate Enterprises of China. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddy, M. Multinomial Inverse Regression for Text Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2013, 108, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, D.; Hu, X.; Rohrer, M. The Colour of Finance Words. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 147, 525–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilokha, A.; Cheng, M.; Fu, M.; Hasan, I. Understanding CSR Champions: A Machine Learning Approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stock Market Performance. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2009, 19, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X. ESG Investment in China: Doing Well by Doing Good. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2023, 77, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorovaia, N.; Makrominas, M. Identifying Greenwashing in Corporate-social Responsibility Reports Using Natural-language Processing. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2024, 31, 427–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.-T.; Wang, K.; Sueyoshi, T.; Wang, D.D. ESG: Research Progress and Future Prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Tang, Y.; Chen, G. Chief Sustainability Officers and Corporate Social (Ir) Responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 656–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, B.; Hasanzadeh, S.; Samavat, M.; Nazari, S. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Management Opportunism: The Role Moderating of Corporate Governance. Account. Audit. Rev. 2023, 30, 560–589. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsantonis, S.; Pinney, C.; Serafeim, G. ESG Integration in Investment Management: Myths and Realities. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Li, O.Z.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the Stockholder to the Stakeholder: How Sustainability Can Drive Financial Outperformance; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi, A.; Glaum, M.; Kaiser, S. ESG Performance and Firm Value: The Moderating Role of Disclosure. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Environmental Information Disclosure in the “Carbon Trading Pilot” Project on the Financial Performance of Listed Enterprises in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Lin, D. Mandatory Disclosure and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from China’s “Explanation for Nondisclosure” Requirement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Elahi, E.; Khalid, Z. Do Green Finance Policies Foster Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance of Corporate? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, N. The Effect of Environmental, Social, and Governance (Esg) Performance on Corporate Financial Performance in China: Based on the Perspective of Innovation and Financial Constraints. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.M.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, X. ESG Trade-off with Risk and Return in Chinese Energy Companies. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2024, 18, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. The Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Factor on the Financial Performance of China’s Companies. Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 57, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xie, J. Bad Greenwashing, Good Greenwashing: Corporate Social Responsibility and Information Transparency. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 3095–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollero, A.; Palazzo, M.; Siano, A.; Elving, W.J. Avoiding the Greenwashing Trap: Between CSR Communication and Stakeholder Engagement. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbritter, G.; Dorfleitner, G. The Wages of Social Responsibility—Where Are They? A Critical Review of ESG Investing. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2015, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.S.; Sinclair, G.; Yang, T. Understanding ESG ratings and ESG indexes. In Research Handbook of Finance and Sustainability; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 339–371. ISBN 1-78643-263-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Moon, J. Analyzing the Financial Impact of ESG News Sentiment on ESG Finance Trends. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Platform Technology and Service (PlatCon), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 26–28 August 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Giannarakis, G. The Determinants Influencing the Extent of CSR Disclosure. Int. J. Law Manag. 2014, 56, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.C.; Watson, J.; Woodliff, D. Corporate Governance Quality and CSR Disclosures. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, P.; Rahman, P.M. Impact of Corporate Governance on CSR Disclosure. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2020, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarrone, E.; Forciniti, A. CSR & Sentiment Analysis: A New Customized Dictionary; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 466–479. [Google Scholar]

- Niveditha, R.; NS, N.K.; Parimi, M.R.; Raam, A.; Babu, S. Develop CSR Themes Using Text-Mining and Topic Modelling Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing in Emerging Markets (CCEM), Bengaluru, India, 6–7 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, A.; Doyle, K.; Kern, M.L. Community Construals of CSR for Happiness: A Mixed-Method Study Using Natural Language. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2023, 18, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, T.-T.; Heng, Q.K.; Chia, J.J.; Shie, J.M.; Liaw, S.W.; Yang, M.; Nguwi, Y.-Y. Machine Learning-Based Corporate Social Responsibility Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems (CIS) and IEEE Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics (RAM), Bangkok, Thailand, 18–20 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 501–505. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Liew, K.; Rahman, M. Employing Machine Learning to Deduce a Causal Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance. Fluct. Noise Lett. 2023, 2440015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M.; Holmlund, M. Impression Management Tactics in Sustainability Reporting. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, S.; Jarboui, A. CSR or Social Impression Management? Tone Management in CSR Reports. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2021, 20, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouryousof, A.; Nassirzadeh, F.; Askarany, D. Inconsistency in Managers’ Disclosure Tone: The Signalling Perspective. Risks 2023, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhou, L. Textual Tone in Corporate Financial Disclosures: A Survey of the Literature. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2020, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.; Li, H.; Tong, Y.H. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Performance and Stakeholder Engagement: Evidence from the Quantity and Quality of CSR Disclosures. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.T.; Magilke, M.J. The Timing of Earnings Announcements: An Examination of the Strategic Disclosure Hypothesis. Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbaty, M.; Hellmann, A.; He, L. Infographics in Corporate Sustainability Reports: Providing Useful Information or Used for Impression Management? J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020, 26, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M. Board Gender Diversity and Managerial Obfuscation: Evidence from the Readability of Narrative Disclosure in 10-K Reports. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.; Parker, L.; Courtis, J. Impression Management through Minimal Narrative Disclosure in Annual Reports. Br. Account. Rev. 2015, 47, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl-Davies, D.M.; Brennan, N.M. Discretionary Disclosure Strategies in Corporate Narratives: Incremental Information or Impression Management? J. Account. Lit. 2007, 27, 116–196. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. The Nature of Man. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 1994, 7, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, K.K. Value of Multinationality: Internalization, Managerial Self-interest, and Managerial Compensation. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2002, 29, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttakin, M.B.; Khan, A.; Azim, M.I. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures and Earnings Quality: Are They a Reflection of Managers’ Opportunistic Behavior? Manag. Audit. J. 2015, 30, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Hussain, N.; Khan, S.A.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Managerial Entrenchment, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Earnings Management. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1818–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R.L.; Spiropoulos, H. CSR Restatements: Mischief or Mistake? J. Manag. Account. Res. 2023, 35, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Ponn, J.; Richardson, G.D.; Rudzicz, F.; Tsang, A.; Wang, J. A Textual Analysis of US Corporate Social Responsibility Reports. Abacus 2020, 56, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Holtbrügge, D. Antecedents of Corporate Misconduct: A Linguistic Content Analysis of Decoupling Tendencies in Sustainability Reporting. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2021, 30, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ng, K.C.; Zheng, R.; Tam, K.Y. The Effects of Sentiment Evolution in Financial Texts: A Word Embedding Approach. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2024, 41, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadi, E.A.; He, Z.; Darko, D.F.; Abrokwah, E. Unlocking from Community Stakeholders, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Projects for Effective Company–Community Relationship. Labor Hist. 2018, 59, 746–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsu, F.; Adams, S. Energy Consumption, Finance, and Climate Change: Does Policy Uncertainty Matter? Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 70, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Qamruzzaman, M. An Asymmetric Investigation of the Nexus between Economic Policy Uncertainty, Knowledge Spillover, Climate Change, and Green Economy: Evidence from BRIC Nations. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 807424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M.; Yavaş, Ç.V. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Climate Change: Evidence from CO2 Emission. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 191, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, G.L.; Trindade, D.N.; Sodario, M.; Ferronatto, G. Creating sustainable value: An ESG framework for the petroleum industry. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference Brasil, OTC, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 24–26 October 2023; p. D021S019R006. [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway, C.A.; Maclagan, P.W. Managers’ Personal Values as Drivers of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information Asymmetry, Corporate Disclosure, and the Capital Markets: A Review of the Empirical Disclosure Literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. Is Sustainability Reporting (ESG) Associated with Performance? Evidence from the European Banking Sector. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, B.A.; Hamdan, A. ESG Impact on Performance of US S&P 500-Listed Firms. Corp. Gov. 2020, 20, 1409–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Rahman, M.L. Mandatory CSR Expenditure and Stock Return. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 951–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Dong, H.; Lin, C. Institutional Shareholders and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Opportunism and Its Critics. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1993, 14, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | EC | CSR | |

| ROE | −0.004 ** | 0.617 *** | 0.037 |

| (−2.41) | (111.21) | (1.00) | |

| EC | −0.065 *** | ||

| (−3.30) | |||

| LEV | 0.081 *** | −0.513 *** | 0.054 ** |

| (3.45) | (−145.14) | (2.09) | |

| BM | −0.570 *** | −0.004 | −0.112 *** |

| (−2.90) | (−1.22) | (−5.47) | |

| SOE | −0.020 | −0.215 *** | −0.042 *** |

| (−1.54) | (−114.79) | (−2.78) | |

| SEO | −0.105 *** | −0.006 | −0.097 *** |

| (−3.09) | (−1.24) | (−2.98) | |

| MA | 0.088 *** | −0.004 ** | 0.082 *** |

| (7.14) | (−2.02) | (6.79) | |

| Age | −0.100 *** | 0.005 *** | −0.099 *** |

| (−9.00) | (5.12) | (−8.72) | |

| Size | 0.235 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.304 *** |

| (31.93) | (647.61) | (22.44) | |

| Constant | −0.049 | −1.39 *** | −0.36 *** |

| (−0.64) | (−71.99) | (−2.69) | |

| Year FE | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE |

| Industry FE | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE |

| Coef. | |

|---|---|

| CSR (t − 1) | −0.110 *** |

| (−2.72) | |

| ROE | 0.422 *** |

| (23.18) | |

| LEV | 0.252 *** |

| (12.81) | |

| BM | −1.063 *** |

| (−60.71) | |

| SOE | −0.012 * |

| (−1.71) | |

| SEO | −0.021 |

| (−0.73) | |

| MA | 0.040 *** |

| (3.13) | |

| Age | −0.006 * |

| (−1.66) | |

| Size | 0.106 *** |

| (22.06) | |

| Constant | 0.631 *** |

| (14.21) | |

| Year FE | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes |

| CSR Disclosure Level | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |

| ROE | −0.151 *** | 0.13 * |

| (−2.69) | (1.74) | |

| LEV | 0.197 *** | 0.086 |

| (9.59) | (1.53) | |

| BM | −0.109 *** | −0.254 *** |

| (−5.93) | (−5.62) | |

| SOE | −0.013 | −0.101 *** |

| (−1.07) | (−3.17) | |

| SEO | −0.093 *** | −0.184 * |

| (−3.22) | −1.82 | |

| MA | 0.077 *** | 0.109 *** |

| (7.02) | (3.35) | |

| Age | −0.099 *** | −0.08 *** |

| (−9.86) | (−2.97) | |

| Size | 0.264 *** | 0.214 *** |

| (36.20) | (9.76) | |

| Constant | −0.034 | −0.377 *** |

| (−0.48) | (−4.00) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes |

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| CSR (t − 1) | −0.031 *** | 0.000 |

| (−3.82) | (0.07) | |

| ROE | 0.006 *** | 0.805 *** |

| (3.05) | (13.92) | |

| LEV | −0.098 *** | 0.297 *** |

| (−2.75) | (9.62) | |

| BM | −1.126 *** | −1.073 *** |

| (−27.26) | (−39.94) | |

| SOE | −0.005 | −0.005 |

| (−0.30) | (−0.48) | |

| SEO | −0.099 | −0.005 |

| (−1.08) | (−0.14) | |

| MA | 0.021 | 0.054 *** |

| (0.67) | (3.12) | |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.008 |

| (−0.20) | (−1.54) | |

| Size | 0.177 *** | 0.091 *** |

| (15.44) | (13.38) | |

| Constant | 0.790 *** | 0.640 *** |

| (7.65) | (9.45) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, H. The Keywords in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Dictionary Construction Method Based on MNIR. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062528

Liu Y, Li Y, Chen H. The Keywords in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Dictionary Construction Method Based on MNIR. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062528

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yinong, Yanying Li, and Huiying Chen. 2025. "The Keywords in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Dictionary Construction Method Based on MNIR" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062528

APA StyleLiu, Y., Li, Y., & Chen, H. (2025). The Keywords in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Dictionary Construction Method Based on MNIR. Sustainability, 17(6), 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062528