Abstract

The global rise in plastic use has severe environmental consequences. To combat these consequences, on 1 January 2017, Israel implemented a law imposing a levy on single-use plastic bags. This study assessed the long-term impact of this levy on plastic bag usage and consumer intentions seven years later. It also examined psychological factors, social attitudes, and sociodemographic influences on reducing plastic bag consumption. Data were collected from 870 Israeli respondents through an online survey, and a mediation model was analyzed using path analysis with AMOS. The results showed that 44% of participants significantly reduced their disposable plastic bag use due to the policy. Overall, levels of intention to reduce plastic bag use ranged from moderate to moderately high. Positive attitudes toward the policy, stronger instrumental beliefs, and higher levels of subjective norms were linked to greater plastic-related environmental concerns, which correlated with stronger intentions to reduce plastic use. The findings highlight the importance of policy interventions in reducing plastic bag usage by shaping attitudes, fostering environmental concerns, and motivating behavioral change.

1. Introduction

The increased global use of plastic has severe negative environmental implications, given that plastic waste has high environmental resistance and does not decompose for many years [1,2]. Global consumption of plastic bags is estimated at 5 trillion bags every year [3]. The use of disposable plastic bags (henceforth, DPBs) affects climate change in various ways, leading to further negative impacts on human health, society, and the economy [4].

Over the past two decades, international norms regarding DPBs have shifted significantly [5]. Since 2010, the number of public policies regulating plastic bags has more than tripled, and such regulation is now present on every continent [6]. These policies primarily take the form of either bans or levies, with bans being the more common approach [6]. Experiences from around the world suggest that proactive policy measures such as restrictions or charges tend to be more effective than voluntary campaigns [7].

A 2019 analysis of reports on plastic bag consumption in key markets, including the USA, the EU, and China, found no substantial decrease in global sales [6]. Furthermore, evidence from several countries indicates a decline in public compliance with the levy system over time, exhibiting a “rebound effect”. In South Africa, for example, plastic bag usage initially dropped by 80% but later stabilized at a 44% reduction compared to pre-policy levels [8,9]. A similar pattern emerged in Sweden, where the introduction of a plastic bag levy in 1997 led to an initial 42% decline in sales, followed by a 23% increase between 2004 and 2016 [6]. Likewise, in Ireland, the levy initially caused a 90% reduction in per capita plastic bag usage. However, five years later, consumption rose, prompting an increase in the tax [10].

The Israeli Plastic Bag Law for reducing the use of single-use plastic bags went into effect on 1 January 2017. The law requires large retailers to charge a fee of ILS 0.1 for bags thicker than 20 microns. The Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection reported a reduction of over 80% in single-use plastic bag sales in the first quarter of 2017 [11]. In addition, for 2022, the Ministry reported that major retailers sold consumers approximately 474 million plastic bags—a 73% reduction in bag consumption compared to 2016 [12].

A consumer survey conducted in Israel in 2009 [13], eight years before the law was implemented, found that the average household consumed 1000 bags per year, or 2.7 bags per day. To the best of my knowledge, since then no updated research has examined the law’s long-term impact on consumer attitudes and behavior in Israel. The current study fills this void.

Although several studies have examined the “rebound effect” in the context of plastic bag levies—where initial reductions in plastic bag usage are followed by a decline in compliance over time—few have evaluated the long-term effects of DPBs policy interventions, including residents’ perceptions and behavioral changes [5].

The current study aims to address this gap by examining the long-term impact of the levy on reducing DPBs usage and consumers’ intentions to minimize consumption, seven years after the law’s implementation in Israel. Additionally, it contributes to the literature by exploring the psychological factors, social attitudes, and sociodemographic characteristics that influence Israeli consumers’ intentions to reduce DPBs use. The main conclusion of the study highlights the vital role that policy intervention plays in reducing DPBs use by shaping attitudes, promoting environmental awareness about plastic, and strengthening individuals’ intentions to minimize their plastic consumption. Assessing the long-term efficacy of such levies across different countries, along with understanding consumer awareness and behavioral intentions, is essential for strengthening policy effectiveness and mitigating the “rebound effect.”

2. Literature Review

Research consistently shows that psychological factors and consumer attitudes significantly affect purchasing behavior concerning plastic packaging [14,15]. These influences can result in varying preferences and behaviors in how consumers purchase and use plastic packaging [16,17,18]. Several studies have examined consumer attitudes and preferences regarding plastic food packaging in different countries [19,20,21].

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [22] is one of the most frequently used frameworks to explain pro-environmental behavior [23,24,25,26,27]. According to the TPB, intention is the primary factor that motivates behavior. Such intentions are shaped by attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude refers to people’s beliefs about the potential outcomes of a behavior and their assessment of those outcomes. Subjective norms, on the other hand, involve evaluating the opinions of important others regarding one’s participation in the behavior and one’s willingness to conform to those opinions. Moreover, subjective norms are defined by rules and standards specific to the individual [28]. Numerous studies emphasize the role of subjective norms in addressing environmental issues [23,28,29,30,31,32,33]. A 2021 study [34] demonstrated that subjective norms together with barriers significantly influence efforts to reduce plastic packaging consumption. Another 2021 study [35] similarly identified subjective norms as the most influential factor shaping consumer intentions when selecting environmentally friendly packaging as an alternative to plastic.

Attitudes play a significant role in shaping environmental behaviors, particularly regarding plastic usage [23,36]. A 2020 study among Malaysians [37] showed that attitude has a positive and significant impact on behavioral intention related to the reduce, reuse, and recycle approach to plastic use. According to [22], the attitude component of an intention encompasses instrumental beliefs, which outline expected outcomes. These include perceptions of potential benefits, like improved health, as well as potential costs, such as money, time, and effort linked to adopting a new behavior [38]. In a 2022 study that examined plastic bag use among Vietnamese consumers, instrumental beliefs included the belief that plastic waste harms human health and the environment in addition to belief in the benefits of using cloth bags. Although the study found the effect of this factor on consumers’ plastic bag behavior to be insignificant, the authors noted that this result seemingly suggests Da Nang residents “may not understand exactly how plastic bags affect humans” (p. 671, [39]).

Environmental attitudes are another related attitude component. These encompass moral, psychological, and social perspectives that individuals develop through their interactions with the environment. Gaining insight into consumers’ environmental attitudes and concerns can play a crucial role in addressing the challenge of reducing plastic packaging use [40]. A 2023 study conducted in Germany [32] found that environmental attitudes explain differences between consumer groups with high versus low levels of intention to reduce plastic packaging usage. In addition, a 2017 study conducted in China [41] showed that environmental concern was inversely correlated with intent to use plastic bags.

The extended TPB model in [41] also took into consideration the convenience of using plastic bags. Plastic bags are easy to carry and effective in protecting goods from oil and water. Indeed, a study conducted in 2011 suggested that when consumers perceive plastic bags as convenient to obtain or use, they are more likely to incorporate them into their daily routines [42]. The 2017 China study [41] showed that the convenience of using plastic bags negatively correlated with the intent to reduce the use of plastic bags. Moreover, a recent study by Zhou et al. [25] found that convenience is a key factor influencing consumers’ willingness to reduce plastic bag usage in China.

Government policy intervention is also a key factor in reducing single-use plastic bag consumption [43,44,45]. Policy measures, such as bans and levies, have played a role in shaping public environmental behaviors [43]. Therefore, the success of these policies is a key factor in determining public engagement in environmental actions [46]. A 2023 Chinese study [23] showed that attitudes toward policy interventions significantly affect plastic avoidance behavioral intentions.

Additionally, previous studies have found that sociodemographic variables are related to reduced plastic packaging consumption. For example, reduced consumption was found among older individuals [47], those with higher education and higher income [19,48,49], and women [50,51]. However, a 2019 study [52] revealed that individuals across all age, gender, and income groups in England significantly decreased their plastic bag usage within a month of the plastic bag charge being implemented.

The diverse findings in the literature described above pertain to various countries. Yet, policies are not uniform across nations, and the role of consumers in addressing the consequences of plastic packaging over time remains underexplored. The current study examines the factors influencing intention to reduce usage of disposable plastic packaging over time among Israeli consumers following government intervention. Understanding the situation in different countries and the factors influencing reduced usage over time is important in formulating complementary policy measures.

3. Hypotheses

Based on the literature findings, the hypotheses of the current study are:

H1:

Higher levels of instrumental beliefs are associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use.

H2:

Higher levels of subjective norms are associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use.

H3:

Higher levels of attitudes toward policy intervention are associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use.

H4:

Higher levels of concern for the environment are associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use.

H5:

More positive attitudes toward policy intervention, higher levels of instrumental beliefs, and higher levels of subjective norms are associated with higher levels of environmental concern.

H6:

Higher levels of convenience of using DPBs are associated with lower levels of intention to reduce their use.

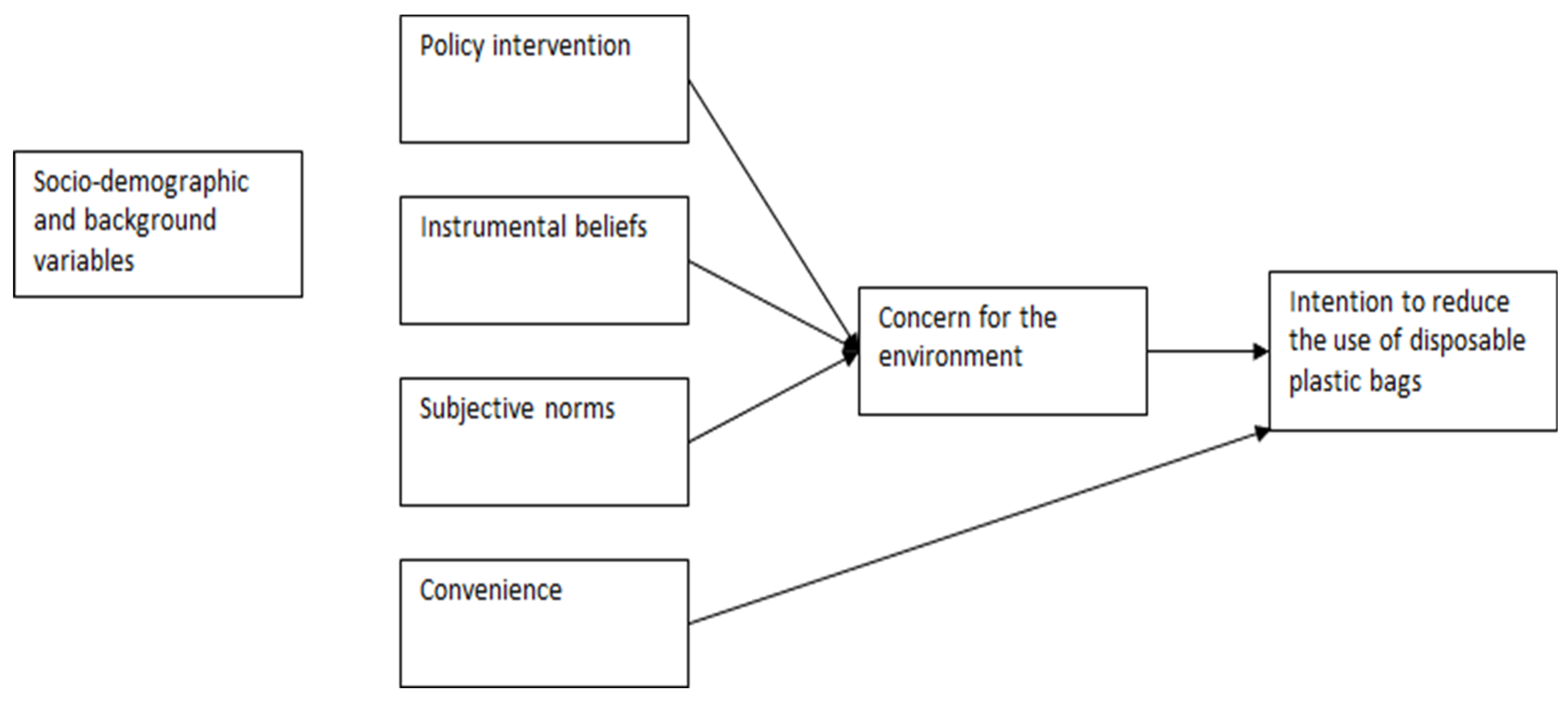

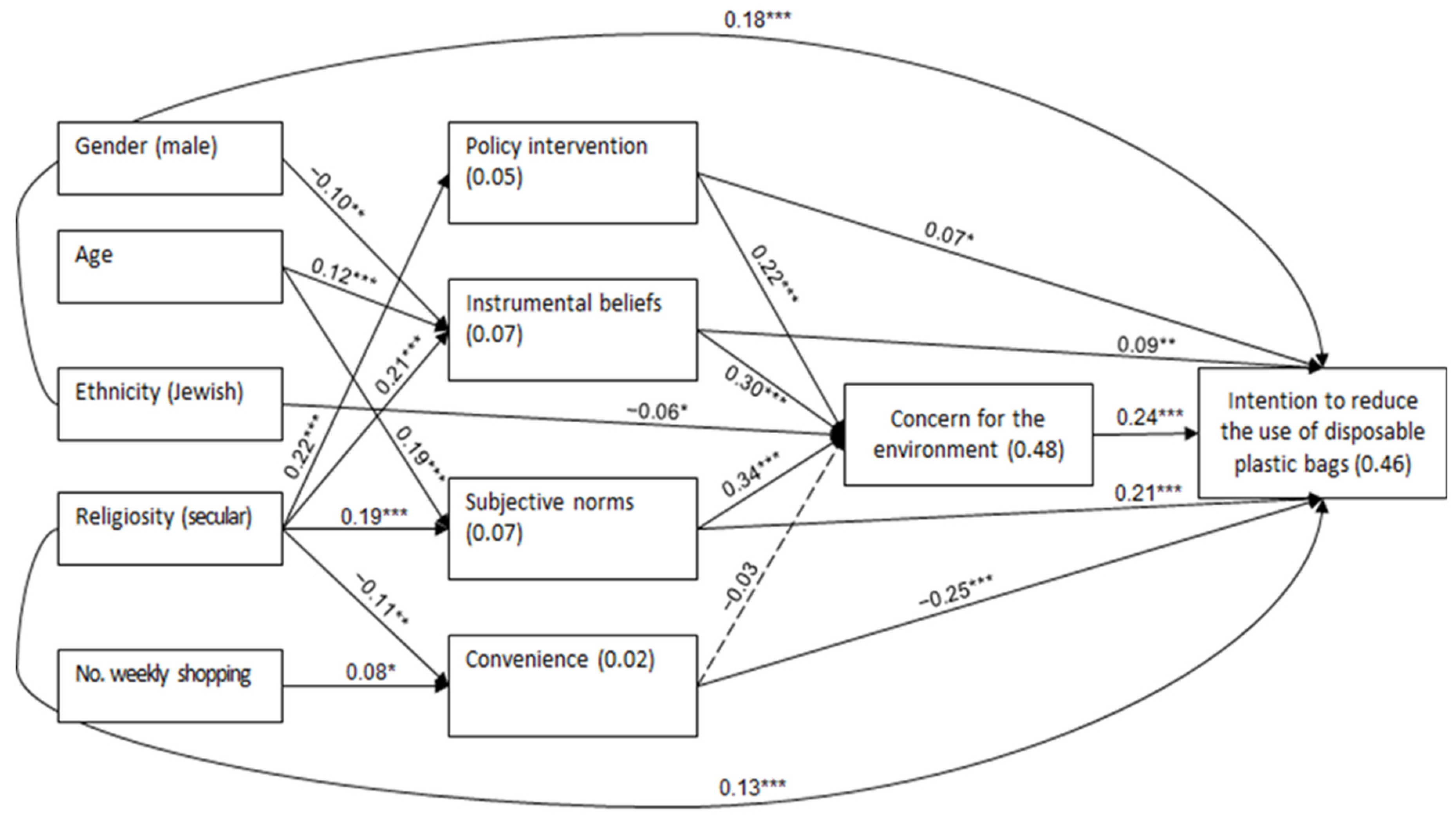

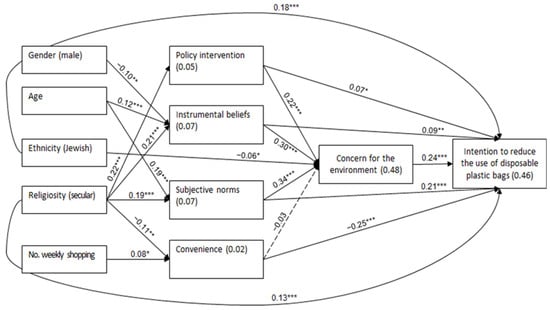

Additionally, a correlation is expected between sociodemographic factors such as gender, age, and education level, and the intention to reduce plastic bag consumption. The proposed model is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The study model.

4. Materials and Methods

The Institutional Review Board of the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College approved the current research. All participants gave their informed consent.

4.1. Sample and Sampling

A sample size was calculated for the mediation model. For a minimum β level of 0.11 for direct effects, with α = 0.05 and a power of 0.80, the required sample size for the indirect effect is 845 participants. For a sample size of 870, assuming chi-square analyses with up to df = 6, α = 0.05 and a moderate-low effect size (w = 0.15), the power level is 0.93.

During March 2024, a professional polling company conducted an online survey. The target sample consisted of internet users registered to the internet survey company aged 25 and older who represent a nationally representative sample of this population in Israel. Therefore, invitations were sent to a representative sample based on demographic quotas, including gender, age, level of religiosity, geographic region, and nationality. Additionally, participants had to pass a screening question confirming that they are responsible for purchasing food for their household. The company sends invitations to respondents based on the defined target audience, and anyone who accesses the link and completes the survey is included in the demographic quota (according to their demographic data) until the quota is filled. A total of 870 responses were collected, aligning with the planned sample size.

Table 1 columns 1–3 describe the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. A total of 51% of the study participants were women, and 49% were men. Most were Israeli-born (85.3%) and Jewish (85.5%), with a mean age of about 44 years (SD = 12.61). Most were married (about 73%) and had children (about 72%), with three to five persons living in the household (about 57%). About 55% had an academic education, and most were employed (about 83%). About 60% reported average or above-average economic status, and about 71% were secular or partly religious.

Table 1.

Intention to reduce use of disposable plastic bags by sociodemographic and other characteristics (N = 870).

4.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire included the following parts:

- Personal details: socioeconomic information; age; marital status; education; nationality; year of immigration; degree of religious observance (1 = not at all religious, 5 = very religious); household income (1 = above average, 5 = much lower than average); number of persons in household; employment status.

- Frequency of household grocery purchases, with answers ranging from once a day to less than once a week. Number of disposable plastic bags used per purchase, with answers ranging from 0 to more than 20. Extent of avoidance of using disposable plastics bags, with participants answering on a 7-point scale ranging from 1= not at all to 7 = always. Frequency of using recycling bags, with participants answering on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = always, to 7 = never.

- Intention to reduce use of disposable plastic bags: This variable, based on the questionnaire in [39], was measured on a scale of 1–7 (1 = not at all, 7 = to a very large extent) as a complex variable that included two items: (a) “How strong is your intention to reduce your use of disposable plastic bags in the coming year when purchasing products at the supermarket or other physical stores?” and (b) “How strong is your intention to use eco-friendly bags when shopping?“ (r = 0.78, p < 0.001).

- Attitude constructs based on [23]: (a) Plastic-related environmental concern measured participants’ agreement/disagreement on a scale of 1–5 (1 = to a very large extent, 5 = not at all) as a complex variable that included two items: “Environmental problems caused by plastics affect my everyday life and health”; “I am worried about the impact on my health of everyday objects made of plastics” (r = 0.77, p < 0.001). (b) Attitude toward policy intervention measured participants’ agreement/disagreement on a scale of 1–7 (1 = not at all, 7= to a very large extent) as a complex variable that included two items: “The government should ban disposable plastic bags” and “The government should increase the tax on disposable plastics bags”, (r = 0.69, p < 0.001).

- Convenience of using disposable plastic bags: Based on [41], this variable measured participants’ agreement/disagreement on a scale of 1–5 (1 = to a very large extent, 5 = not at all) as a complex variable that included three items: “Using disposable plastic bags is convenient”, “Disposable plastic bags are easy to carry”, “Disposable plastic bags are the most convenient tool for my shopping” (α = 0.77).

- Subjective norms: Based on [23], this variable measured participants’ agreement/disagreement on a scale of 1–5 (1 = to a very large extent, 5 = not at all) as a complex variable that included three items: “Most people who are important to me think I should avoid using single-use plastic in everyday life”; “Most of my family members think avoiding single-use plastic is good; and “Most of my close friends think avoiding non-biodegradable plastic is good” (α = 0.89).

- Instrumental beliefs: Based on [39], this variable measured participants’ agreement/disagreement on a scale of 1–7 (1 = not at all, 7 =to a very large extent) as a complex variable that included three items: “Plastic waste harms the environment”; “Plastic waste harms human health”; and “Increasing reusable bag use can benefit the environment and human health” (α = 0.85).

The questionnaire was translated into Hebrew by the author and then back-translated by an English editor. In the first stage, a pilot questionnaire was administered to 20 individuals, and after improvements were made, the final format was developed.

4.3. Statistical Data Analysis Methods

Data were analyzed with SPSS ver. 29. Descriptive statistics were used for the sociodemographic characteristics and the study variables. The internal consistency of the study variables was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha. The study variables were described by means and standard deviations, and Pearson intercorrelations were calculated between them. The dependent variable—intention to reduce DPBs use—was divided into three categories (low, moderate, and high), and its associations with the sociodemographic and background characteristics were examined with chi-square analyses and analyses of variance. The independent variables were sociodemographic variables, attitudes toward policy intervention, subjective norms, instrumental beliefs, convenience of DPBs use, and plastic-related environmental concerns. The study model was examined with path analysis, using AMOS ver. 29. Chi-square analysis, NFI, NNFI, CFI, and RMSEA were used as measures of fit. Variables were standardized. Mediation was examined within the path analysis, with bootstrapping of 5000 samples and the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval.

5. Results

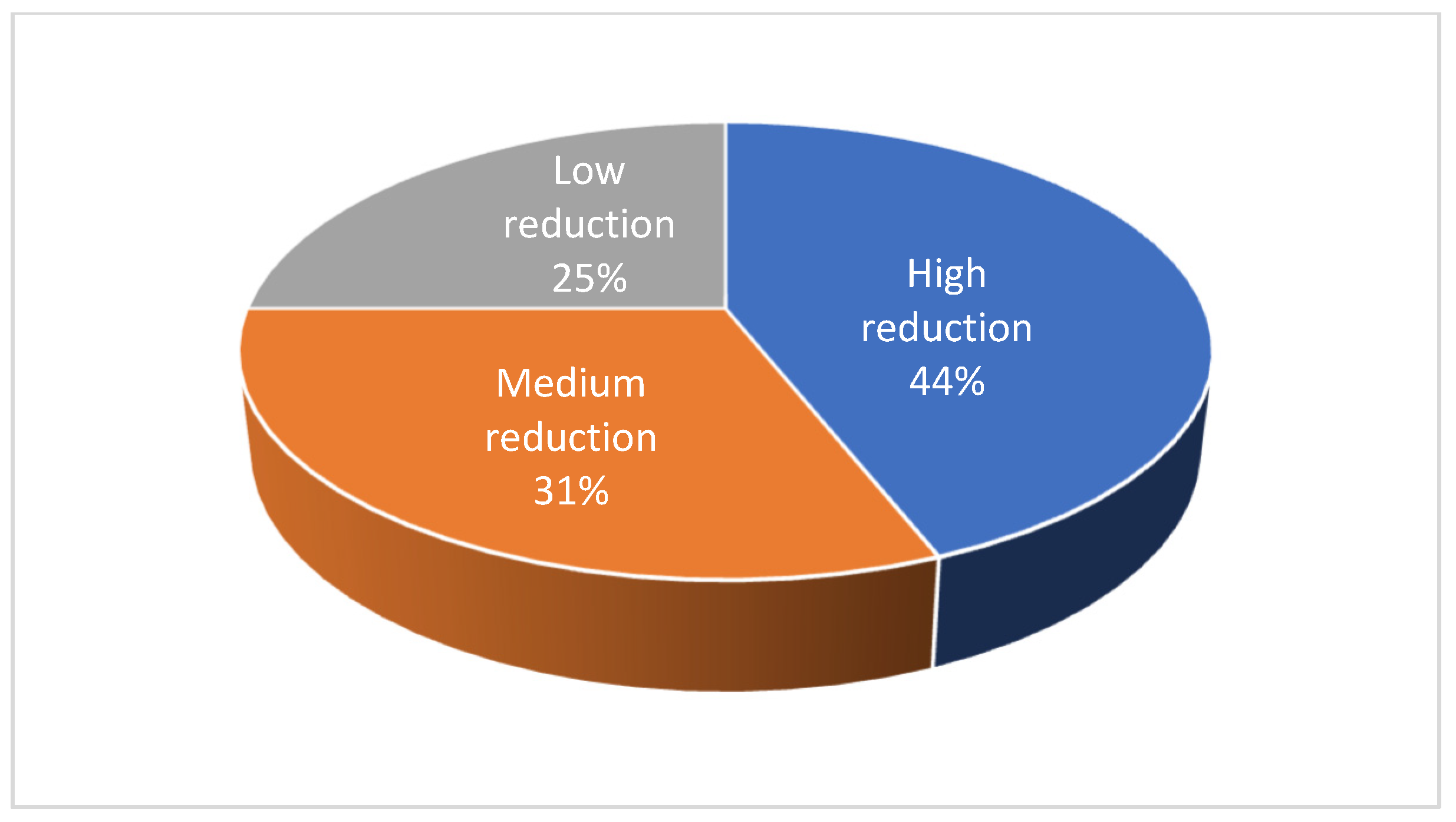

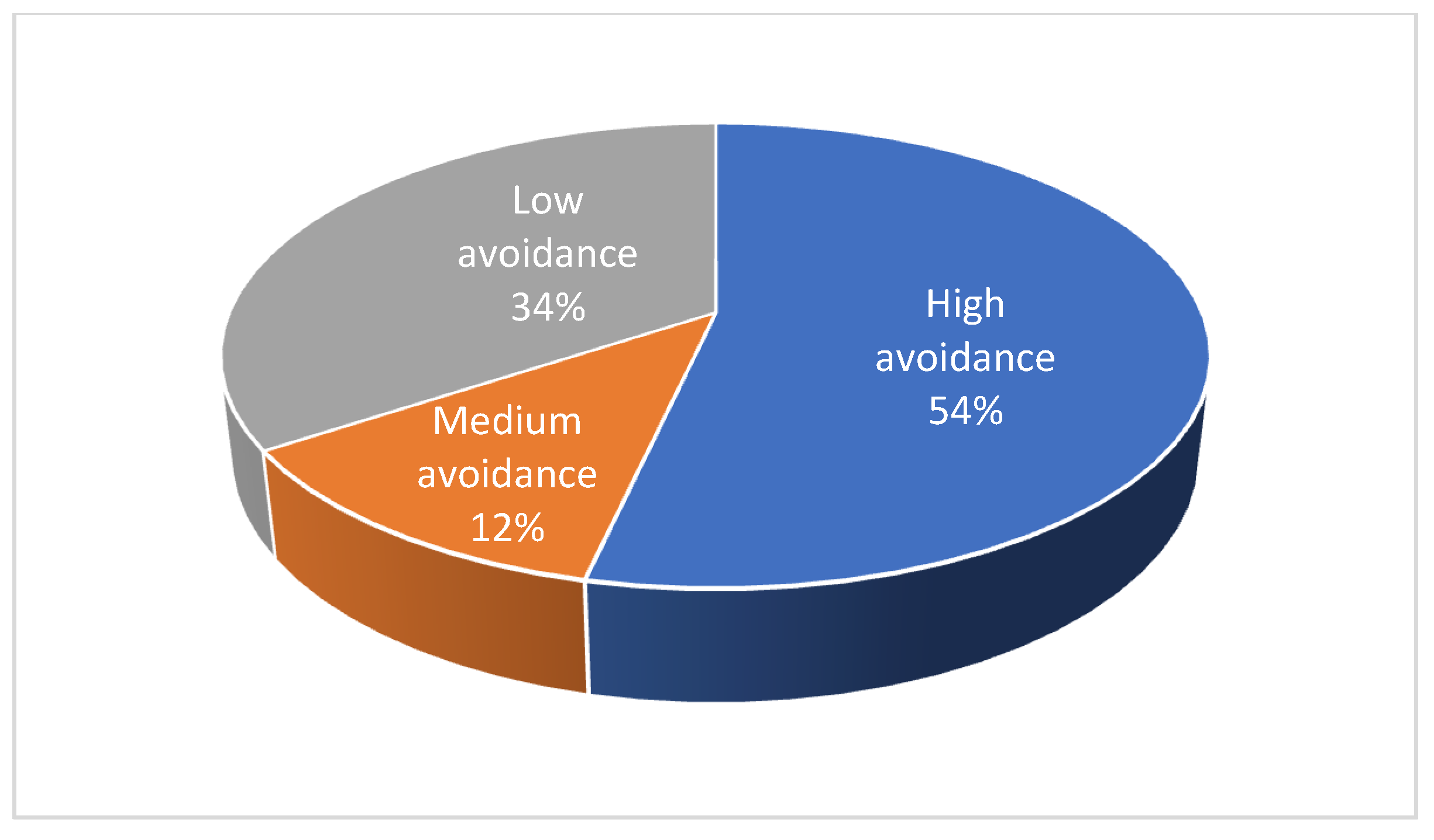

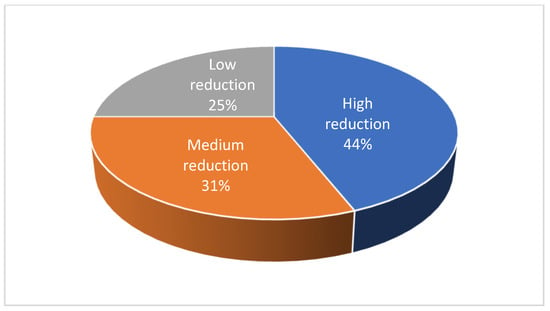

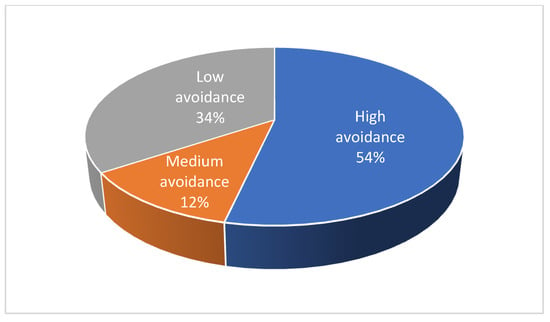

Figure 2 describes the extent of reduction in DPBs use over the last years. Forty-four percent of the participants reported that they completely stopped or significantly reduced their DPBs use over the last years, 31% reported moderate reduction, and 25% reported a small reduction or no change in DPBs use while shopping. As for the current situation, Figure 3 describes the extent of avoidance of DPBs use. Fifty-three percent of the participants reported high or very high DPBs avoidance, 12% reported a moderate level of avoidance, and 34% reported low or no avoidance.

Figure 2.

Extent of reduction in DPBs use over the last years.

Figure 3.

Extent of avoidance of DPBs use in the current situation.

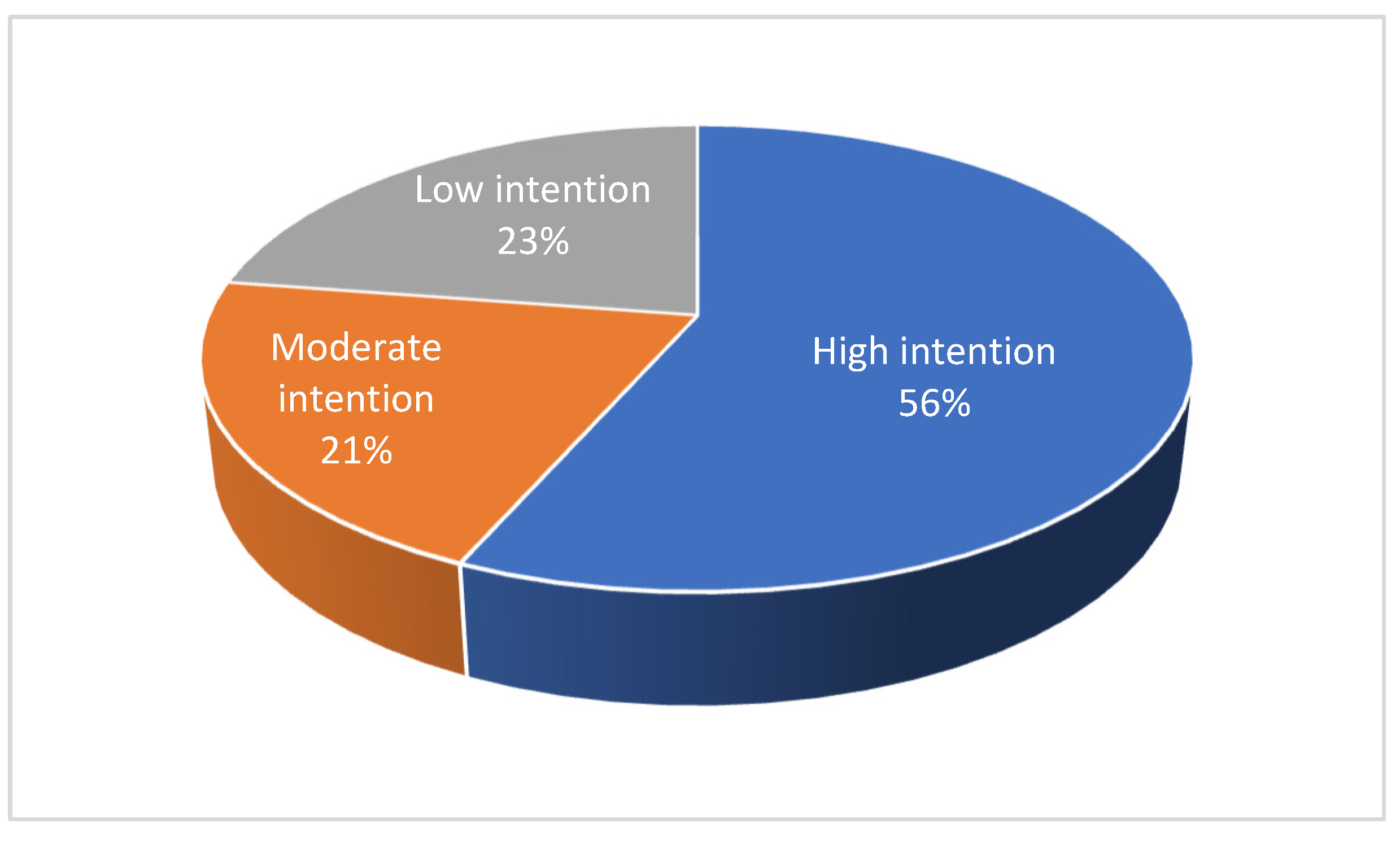

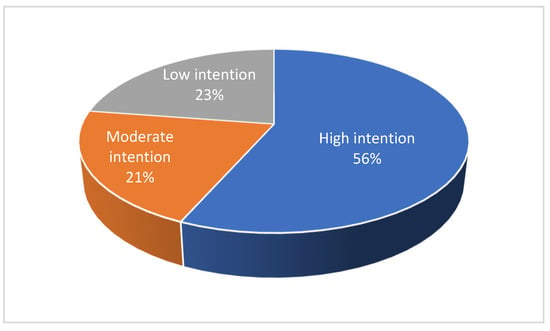

Overall, respondents’ intention to reduce their DPBs use was moderate to moderate–high (M = 4.87, SD = 1.97, range 1–7). The sample was divided into three sub-groups: low level of intention (mean up to 3.5), moderate level of intention (mean of 3.5 to 4.5), and high level of intention (mean above 4.5), yielding a distribution of 22.6% who showed a low level of intention (n = 197), 20.8% who showed a moderate level of intention (n = 181), and 56.6% who showed a high level of intention (n = 492) to reduce their DPBs use (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Extent of intention to reduce DPBs use in the current situation.

Table 1 shows the associations between sociodemographic and background variables and the three above sub-groups.

The results show no gender differences, with over 50% of both men and women revealing a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use. A significant age difference was found, with participants showing a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use somewhat older than those showing a low level of intention. No difference was found for marital status or level of education, with over 50% of both married and non-married participants and of participants with and without an academic degree showing a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use.

A significant difference emerged for ethnicity, with about 35% of non-Jewish participants showing a low level of intention to reduce their DPBs use, compared with about 20% of Jewish participants, and about 44% of non-Jewish participants showing a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use, compared with close to 60% of Jewish participants. Another significant difference was found for level of religiosity, with about 70% of secular participants showing a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use, compared with about 50% of partly religious and religious participants. Similarly, about 65% of participants with an above-average income expressed a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use, compared with about 50% of those with average or below average income. A significant difference was further found according to number of persons in the household, with participants who exhibited a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use living in households with fewer people than those showing a low or moderate level of intention.

A significant difference was also found for the average number of times a week people shopped for groceries. Most participants who shopped for groceries once or twice a week showed a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use (about 60%), compared with about 45% of those who shopped for groceries three times a week or more. Almost all participants who did not use any disposable plastic bags per shopping trip expressed a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use (about 88%), compared with about 63% of those who used one to three disposable plastic bags per shopping trip and about 35% to 43% of those who used four bags or more. Finally, almost all participants were aware of the DPBs tax (91%), with a higher percentage of participants who were aware of the tax showing a high level of intention to reduce their DPBs use (about 58%) than participants who were unaware of this tax (about 39%).

Table 2 shows the distribution of the study variables and the correlations among them. The results show that the intention to reduce DPBs use was positively associated with concern for the environment, attitudes toward policy intervention, instrumental beliefs, and subjective norms and was negatively associated with convenience. These levels of intention were also higher among older people, those with higher economic status, Jewish participants, secular participants, those with fewer persons in the household, and less frequent trips to the grocery store. Concern for the environment was positively associated with attitudes toward policy intervention, instrumental beliefs, and subjective norms and negatively associated with convenience. Environmental concern was also higher among older individuals, Arab participants, and secular individuals. Positive correlations were found among attitudes toward policy intervention, instrumental beliefs, and subjective norms, and all were negatively associated with convenience of DPBs use.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations for the study variables (N = 870).

The study model was examined with a path analysis using AMOS (ver. 29), as shown in Figure 5. The model was found to fit the data well: χ2(28) = 32.55, p = 0.253, NFI = 0.982, NNFI = 0.995, CFI = 0.997, RMSEA = 0.014.

Figure 5.

Path analysis for the intention to reduce use of disposable plastic bags, with concern for the environment, attitudes toward policy intervention, instrumental belief, subjective norms, and convenience. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Note. Values on arrows—β values; values within the rectangles—R2. Non-significant associations with the demographic and background variables were excluded from the analysis; all other associations were included. Income and number of persons in the home had no significant associations and were thus removed from the model.

The results show that more positive attitudes toward policy intervention, higher levels of instrumental beliefs, and higher levels of subjective norms were associated with greater concern for the environment. Further, more positive attitudes toward policy intervention, higher levels of instrumental beliefs, higher levels of subjective norms, and lower convenience were associated with a higher level of intention to reduce DPBs use. A higher concern for the environment was also associated with a greater intention to reduce DPBs use.

In addition, as previously shown, being Jewish and being secular were also associated with a greater intention to reduce DPBs use. Women had higher levels of instrumental beliefs than men, and older participants demonstrated higher levels of instrumental beliefs and higher levels of subjective norms. Secular participants demonstrated more positive attitudes toward policy intervention, higher levels of instrumental beliefs, higher levels of subjective norms, and lower convenience than non-secular participants. Finally, shopping for groceries more frequently per week was associated with higher convenience.

As shown in Figure 5, concern for the environment may mediate the associations between attitudes toward policy intervention, instrumental beliefs, and higher levels of subjective norms on the one hand and the intention to reduce DPBs use on the other hand. The results in Table 3 confirm that mediation was significant for attitudes toward policy intervention, instrumental beliefs, and subjective norms and was not significant for convenience. That is, more positive attitudes toward policy intervention, higher levels of instrumental beliefs, and higher levels of subjective norms were associated with greater concern for the environment, which in turn was associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use. All the mediated associations are partial, as the direct effects are significant as well. The mediated association for attitudes toward policy intervention explains 41.9% of the total variance, the mediated association for instrumental beliefs explains 45.6% of the total variance, and the mediated association for subjective norms explains 28.1% of the total variance. The association between convenience and intention to reduce DPBs use is direct and is not mediated by concern for the environment.

Table 3.

Indirect effects for the mediating role of concern for the environment in the associations with the intention to reduce the use of disposable plastic bags (N = 870).

6. Discussion

The current research aims to examine the long-term impact of the 1 January 2017 levy that sought to reduce the use of single-use plastic bags in Israel. In addition, the study examines the psychological factors, social attitudes, and sociodemographic characteristics influencing the intention to reduce DPBs use among Israeli consumers.

After the levy was imposed in Israel in 2017, the initial reduction in single-use plastic bags was over 80% [11], similar to findings in England and Scotland after one year and in Greece after just one month [6]. However, an analysis by Nielsen et al. [6] (2019) of plastic bag consumption in key markets—including the USA, the EU, and China—suggests that the short-term impact of pricing mechanisms (e.g., levies or taxes) varied across countries. For example, Portugal saw a 74% reduction after four months, while Chicago (USA) experienced a 42% decrease after two months. [6]

Despite these short-term successes, few studies have assessed the long-term effects of DPBs policy interventions. Several researchers have raised concerns about a potential long-term “rebound effect” associated with plastic bag levies. For instance, in South Africa, the initial 80% drop in DPBs consumption later stabilized at a 44% reduction compared to pre-policy levels [8,9]. Similarly, in Sweden, an initial 42% decline in DPBs sales was followed by a 23% increase between 2004 and 2016 [6].

The results of the current study show that seven years after the levy was imposed, 44% of participants reported completely stopping or significantly reducing their DPBs use in recent years, 31% reported a moderate reduction, and 25% reported either a small reduction or no change in their DPBs use while shopping. The distribution of intention to reduce DPBs use in the coming year was as follows: 56.6% showed a high level of intention, 20.8% showed a moderate level of intention, and 22.6% showed a low level of intention.

The results also show a higher level of intention to reduce DPBs usage among older individuals and those with higher incomes. These results are compatible with 2015 findings [47] with respect to age differences and also compatible with findings from 2017 [48] and 2020 [49] with respect to income differences. These findings have several implications. One key consideration is the affordability and accessibility of alternatives. For instance, businesses could promote incentives for reusable bags or expand sustainable packaging options, particularly in low socioeconomic areas. Additionally, governments could tailor environmental campaigns to younger and lower-income groups to bridge the intention gap. Policymakers might also consider implementing progressive bans or tiered taxation to encourage equitable reductions across all demographic groups.

Our results also indicate significant differences for ethnicity, with about 60% of Jewish participants showing a high level of intention to reduce DPBs use, compared with 44% of non-Jewish participants. Level of religiosity was also significant, with about 70% of secular participants showing a high level of intention to reduce DPBs use, compared with about 50% of the partly religious and religious participants. This result is contrary to findings for Muslim Pakistani consumers indicating that individuals who are more religious have lower levels of intention to use plastic bags [53]. A possible explanation for the difference in the religiosity results for Jews in Israel and Muslims in Pakistan is the fact that level of religiosity in Israel correlates with number of persons in the household.

Religious households in Israel tend to be larger on average than secular households and purchase a higher-than-average number of grocery products each week. Moreover, we found a significant correlation between religiosity, household size, and the reported convenience of using DPBs. Therefore, it is plausible that religious households have a lower level of intention to reduce DPBs use compared to secular households.

To encourage greater DPBs reduction among religious communities, targeted environmental messaging in public campaigns could be tailored to align plastic reduction with ethical and moral principles found in religious teachings (e.g., responsible consumption). Additionally, governments and NGOs could collaborate with religious leaders and institutions to promote sustainable practices within faith communities. Furthermore, eco-friendly products, such as reusable plastic bags, could be marketed in ways that align with religious values, fostering greater adoption among faith-driven consumers. The current study findings may encourage further research to examine whether current regulations disproportionately affect certain social groups and to propose more balanced solutions.

The analytical model includes the main behavioral factors affecting intention to reduce DPBs use. Our findings reveal that higher levels of subjective norms are associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use, compatible with hypothesis H1. This result is in line with previous studies showing that higher levels of subjective norms are associated with a stronger intention to recycle in Hong Kong [54] and a stronger intention to bring one’s own shopping bags in Vietnam [55]. Moreover, a high level of subjective norms is the strongest predictor of purchase intention in the context of eco-friendly packaged products in Portugal [35].

Our findings also reveal that instrumental beliefs are positively correlated with intention to reduce DPBs use, compatible with hypothesis H2. Previous studies revealed mixed findings with respect to instrumental beliefs. For example, this factor had no significant effect on Vietnamese consumers’ DPBs use [39]. However, our result is in line with the findings in [56] that instrumental values significantly influence environmental consciousness and that environmental consciousness has a significant impact on behavioral intentions.

The results for the third factor indicate that attitudes toward policy intervention are associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use, compatible with hypothesis H3. This result for Israeli consumers is compatible with the findings among Chinese consumers that attitudes toward policy interventions significantly affect plastic avoidance behavioral intentions [23]. This is an important finding since the effectiveness of policies is a critical determinant of public environmental behavior [46].

The analytical model results also show that greater concern for the environment is associated with a higher level of intention to reduce DPBs use, compatible with hypothesis H4. In addition, we found that more positive attitudes toward policy intervention, higher levels of instrumental beliefs, and higher levels of subjective norms were associated with greater concern for the environment, which in turn was associated with higher levels of intention to reduce DPBs use, compatible with hypothesis H5.

Finally, our findings indicate that higher levels of convenience in DPBs use are associated with lower levels of intention to reduce DPBs use, compatible with hypothesis H6. This result is in line with 2017 findings for Chinese consumers [41] and 2015 findings for Mali consumers [47].

Limitations of the Study

The current study has several limitations. First, it relies on a self-reporting method, which may lead to a socially desirable response bias and may affect the accuracy of the results. However, this approach is commonly used in the literature to capture individuals’ actual actions and intentions. Another limitation stems from the fact that the levy introduced in 2017 applies only to consumers shopping at large retailers in Israel, while small stores continue to provide disposable plastic bags free of charge. Consequently, the study does not account for differences in purchasing behavior between large and small stores. This omission limits the study’s ability to provide a comprehensive view of consumer behavior across different retail environments. Consequently, the findings may not be fully generalizable, particularly for consumers who primarily shop at small stores. However, they may still hold some relevance, as these consumers might occasionally purchase from larger stores to access a wider range of products unavailable in smaller shops. Future research should address these gaps by incorporating diverse retail contexts and longitudinal data to better capture behavioral shifts over time.

7. Conclusions

The findings of the current study provide deeper insights into how behavioral factors determine intentions to use disposable plastic bags in Israel. The study suggests that policy intervention is crucial for reducing DPBs use by shaping attitudes, fostering plastic-related environmental concerns, and enhancing individuals’ intentions to reduce their use of plastic. Understanding these factors seven years after implementation of the levy on DPBs usage can enable us to recognize individual characteristics that affect people’s inclination to reduce usage. For example, as previous studies on renewable energy demand suggest, policymakers can address socioeconomic factors such as education and income to strengthen and implement more effective environmental strategies [57]. In other words, insight into these preferences may help in understanding how households can be encouraged to reduce their DPBs use, such as educational campaigns emphasizing positive instrumental outcomes. Therefore, the study’s results may help in creating strategies and initiatives to encourage a sustainable reduction in plastic bag use.

Funding

This research was funded by the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College (protocol code 2023-74 YVC EMEK on 10 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available upon request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DPBs | Disposable plastic bags |

| AMOS | Analysis of Moment Structures |

| ILS | Israeli Shekels |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

References

- Beaumont, N.J.; Aanesen, M.; Austen, M.C.; Börger, T.; Clark, J.R.; Cole, M.; Hooper, T.; Lindeque, P.K.; Pascoe, C.; Wyles, K.J. Global ecological, social and economic impacts of marine plastic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, S.; Schmid, M. Consumers’ awareness of plastic packaging: More than just environmental concerns. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Counts. Available online: https://www.theworldcounts.com/challenges/planet-earth/waste/plastic-bags-used-per-year (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Arriagada, R.; Lagos, F.; Jaime, M.; Salazar, C. Exploring consistency between stated and revealed preferences for the plastic bag ban policy in Chile. Waste Manag. 2022, 139, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhong, Y.; He, X.; Shi, X.; Song, Q. Perception and Behavioural Changes of Residents and Enterprises under the Plastic Bag Restricting Law. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.D.; Holmberg, K.; Stripple, J. Need a Bag? A Review of Public Policies on Plastic Carrier Bags—Where, How and to What Effect? Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassanadumrongdee, S.; Hoontrakool, D.; Marks, D. Perception and Behavioral Changes of Thai Youths Towards the Plastic Bag Charging Program. Appl. Environ. Res. 2020, 42, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, R.; Leiman, A.; Visser, M. The economics of plastic bag legislation in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2007, 75, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikgang, J.; Visser, M. Behavioural response to plastic bag legislation in Botswana. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2012, 80, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muposhi, A.; Mpinganjira, M.; Wait, M. Efficacy of plastic shopping bag tax as a governance tool: Lessons for South Africa from Irish and Danish success stories. Acta Commer. 2021, 21, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globes. Available online: https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001189914 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Ministry of Environmental Protection Report. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/the_international_day_without_the_use_of_disposable_bags (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Ayalon, O.; Goldrath, T.; Rosenthal, G.; Grossman, M. Reduction of plastic carrier bag use: An analysis of alternatives in Israel. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2025–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Yao, Y.; Li, L. The more involved, the more willing to participate: An analysis of the internal mechanism of positive spillover effects of pro-environmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 375, 133959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.-K. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasza, G.; Veflen, N.; Scholderer, J.; Münter, L.; Fekete, L.; Csenki, E.Z.; Dorkó, A.; Szakos, D.; Izsó, T. Conflicting Issues of Sustainable Consumption and Food Safety: Risky Consumer Behaviors in Reducing Food Waste and Plastic Packaging. Foods. 2022, 11, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautish, P.; Paço, A.; Thaichon, P. Sustainable consumption and plastic packaging: Relationships among product involvement, perceived marketplace influence and choice behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemat, B.; Razzaghi, M.; Bolton, K.; Rousta, K. The Role of Food Packaging Design in Consumer Recycling Behavior—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, R.; Rahman, A.; Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R. The knowledge, awareness, attitude and motivational analysis of plastic waste and household perspective in Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 2304–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R. An extension of the theory of planned behaviour in predicting intention to reduce plastic use in the Philippines: Cross-sectional and experimental evidence. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 25, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogt Jacobsen, L.; Pedersen, S.; Thøgersen, J. Drivers of and barriers to consumers’ plastic packaging waste avoidance and recycling—A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. 2022, 141, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Zhu, Z.; Ali, S. Analysis of Factors of Single-Use Plastic Avoidance Behavior for Environmental Sustainability in China. Processes 2023, 11, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, W.; Kato, T.; Yao, W.; Shi, C.; Wang, J.; Fei, F. Investigating key factors influencing consumer plastic bag use reduction in Nanjing, China: A comprehensive SEM-ANN analysis. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 181, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, M.; Hamam, M.; D’Amico, M.; Caracciolo, F. Plastic-free behavior of millennials: An application of the theory of planned behavior on drinking choices. Waste Manag. 2022, 138, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y. Consumers’ intention to bring a reusable bag for shopping in China: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J.; Goh, E. Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: An integrated structural model approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, W. Impact of social/personal norms and willingness to sacrifice on young vacationers’ pro-environmental intentions for waste reduction and recycling. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2117–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, J.L. The cognitive and emotional components of behavior norms in outdoor recreation. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A. Understanding consumers’ behavior intentions towards dealing with the plastic waste: Perspective of a developing country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 142, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Profeta, A.; Decker, T.; Smetana, S.; Menrad, K. Influencing Factors for Consumers’ Intention to Reduce Plastic Packaging in Different Groups of Fast-Moving Consumer Goods in Germany. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muposhi, A.; Mpinganjira, M.; Wait, M. Influence of personal value orientations on pro-environmental behaviour: A case of green shopping bags. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2021, 28, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiefek, J.; Steinhorst, J.; Beyerl, K. Personal and structural factors that influence individual plastic packaging consumption—Results from focus group discussions with German consumers. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 3, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Gomes, S.; Nogueira, M. Sustainable packaging: Does eating organic really make a difference on product-packaging interaction? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 304, 127066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widayat, W.; Praharjo, A.; Putri, V.P.; Andharini, S.N.; Masudin, I. Responsible Consumer Behavior: Driving Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior toward Post-Consumption Plastic Packaging. Sustainability 2022, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.L.; Moorthy, K.; Yoon, C.; Pik, F.; Zhi, W.; Wei, C.; Zhao, G.; Zin, T. Determinants of 3Rs Behaviour in Plastic Usage A Study among Malaysians. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosler, H.-J. A systematic approach to behavior change interventions for the water and sanitation sector in developing countries: A conceptual model, a review, and a guideline. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2012, 22, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarchev, N.; Xiao, C.; Yao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, X.; Le, D.A. Plastic consumption in urban municipalities: Characteristics and policy implications of Vietnamese consumers’ plastic bag use. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escario, J.J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C.; Casaló, L.V. The influence of environmental attitudes and perceived effectiveness on recycling, reducing, and reusing packaging materials in Spain. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D.; Fan, J. Understanding consumers’ intention to use plastic bags: Using an extended theory of planned behaviour model. Nat. Hazards 2017, 89, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Gutscher, H.; Scholz, R.W. Psychological determinants of fuel consumption of purchased new cars. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, T.; Asari, M.; Sakurai, R.; Cordier, M.; Kalyanasundaram, M. Behavioral Barrier-Based Framework for Selecting Intervention Measures toward Sustainable Plastic Use and Disposal. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 384, 135609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblauch, D.; Mederake, L. Government Policies Combatting Plastic Pollution. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 28, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, G.; Balaia, N.; Pires, A. The Portuguese Plastic Carrier Bag Tax: The Effects on Consumers’ Behavior. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Mangmeechai, A.; Su, J. Linking Perceived Policy Effectiveness and Proenvironmental Behavior: The Influence of Attitude, Implementation Intention, and Knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, Y.A.; Traore, A.S. Plastic bags, pollution, and identity: Women and the gendering of globalization and environmental responsibility in Mali. Gend. Soc. 2015, 29, 863–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigele, P.K.; Mogomotsi, G.E.J.; Kolobe, M. Consumer willingness to pay for plastic bags levy and willingness to accept eco-friendly alternatives in Botswana. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 15, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Ruano, M.A. Do you need a bag? Analyzing the consumption behavior of plastic bags of households in Ecuador. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, R.; Wattana, C.; Sracheam, P.; Siriapornsakul, S.; Ruckthum, V.; Clapp, R. An exploration of the factors concerned with reducing the use of plastic carrier bags in Bangkok, Thailand. ABAC ODI J. Vis. Action Outcome 2016, 3, 162–181. [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.O.; Sautkina, E.; Poortinga, W.; Wolstenholme, E.; Whitmarsh, L. The English plastic bag charge changed behavior and increased support for other charges to reduce plastic waste. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.K.; Sadaf, M.; Ali, S.; Danish, M. Consumers’ Intention towards Plastic bags usage in a developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 2019, 12, 3. Available online: http://www.pbr.co.in/2019/2019_month/September/9.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Yu, A. The moderating effect of perceived policy effectiveness on recycling intention. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.L. Intention and behavior toward bringing your own shopping bags in Vietnam: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Soc. Mark. 2022, 12, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Sharma, R.; Mangla, S.K.; Jabeen, F.; Awan, U. Understanding choice behavior towards plastic consumption: An emerging market investigation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, C. Do the Energy-Related Uncertainties Stimulate Renewable Energy Demand in Developed Economies? Fresh Evidence from the Role of Environmental Policy Stringency and Global Economic Policy Uncertainty. Energies 2024, 17, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).