Abstract

This study examines Xi’an’s spatial evolution using Historical GIS (HGIS) methodologies, integrating Space Syntax and Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). Analyzing six historical periods—from the Five Dynasties to the early PRC—it highlights Xi’an’s transformation from a centralized structure reinforcing political hierarchies to a decentralized, polycentric city shaped by economic diversification and industrialization. Centralized layouts in the early periods supported governance and military control, while the Ming and Qing periods saw decentralization driven by trade and cultural exchange via the Silk Road. The PRC era introduced industrial expansion, creating specialized zones but reducing the integration of the historical core. This study bridges historical narratives with quantitative spatial analysis, revealing often-overlooked socio-spatial dynamics. It offers lessons for urban planning, emphasizing polycentric development, adaptive reuse of historical spaces, and equitable growth. Balancing modernization with heritage preservation is a key theme, providing a sustainable model for historic cities. By integrating historical and spatial analysis, this research provides strategies to balance cultural heritage with urban development. This ensures that Xi’an remains a dynamic city that blends history and modernity.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the “Spatial Turn” has provided new perspectives across the humanities and social sciences, encouraging scholars to move beyond traditional micro-level analyses of texts and artifacts. Space is now seen as an active force that shapes human activity rather than a passive backdrop [1,2,3,4]. Spatial configurations interact with social, political, and cultural processes, offering deeper insights into how historical events influence urban environments. The change has helped scholars better understand the relationship between urban transformation and broader societal changes.

A key outcome of this development has been the growing use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in historical and urban studies. GIS enables researchers to visualize and analyze spatial relationships over time, improving our understanding of how cities evolve [5,6,7,8,9,10]. One notable example is David J. Bodenhamer’s concept of “Deep Maps”, which integrates geographic data, social interactions, and cultural narratives into layered spatial analysis. This approach highlights how spatial arrangements have influenced human behavior and development throughout history [11,12,13,14,15].

Among these advancements, Historical GIS (HGIS) has emerged as an essential tool for studying urban change. By combining historical maps with spatial analysis techniques, HGIS allows researchers to trace the long-term transformation of cities and explore the factors that drive their growth and decline [16,17,18]. For historically significant cities like Xi’an, HGIS offers a valuable method for reconstructing urban changes and understanding how shifts in political, economic, and cultural forces have shaped its spatial structure [19,20]. While traditional cartographic approaches remain useful for documenting historical city layouts, they often lack the analytical depth needed to capture the complexity of spatial transformations. The integration of historical mapping with advanced spatial analysis provides new insights into urban development, revealing patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Xi’an, historically known as Chang’an, is one of China’s most important cities, with over 5000 years of continuous habitation and a long history as an imperial capital. It served as the center of governance and culture for multiple influential dynasties, including the Zhou, Qin, Han, and Tang dynasties [21,22]. As the eastern point of the Silk Road, Xi’an played an important role in trade and cultural exchange between East and West [23]. This legacy had a lasting impact on its urban structure, as political changes, economic needs, and cultural interactions have continuously shaped the city’s layout. Despite its historical importance, few studies have used HGIS methodologies to analyze Xi’an’s spatial development [24].

Much of the existing research using conventional cartographic methods is useful for documenting past urban forms. However, it is hard to capture the complexity of spatial relationships over time. Traditional maps primarily present static representations and do not effectively reveal how urban patterns respond to social, political, or economic forces. To address this gap, this study employs HGIS alongside advanced spatial analysis techniques, including Space Syntax and Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). These methods allow for a systematic examination of Xi’an’s urban evolution across six historical periods: the Five Dynasties, Northern Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing, and the early People’s Republic of China. By integrating multiple approaches, this study provides a data-driven perspective on how historical forces have shaped the city’s urban structure.

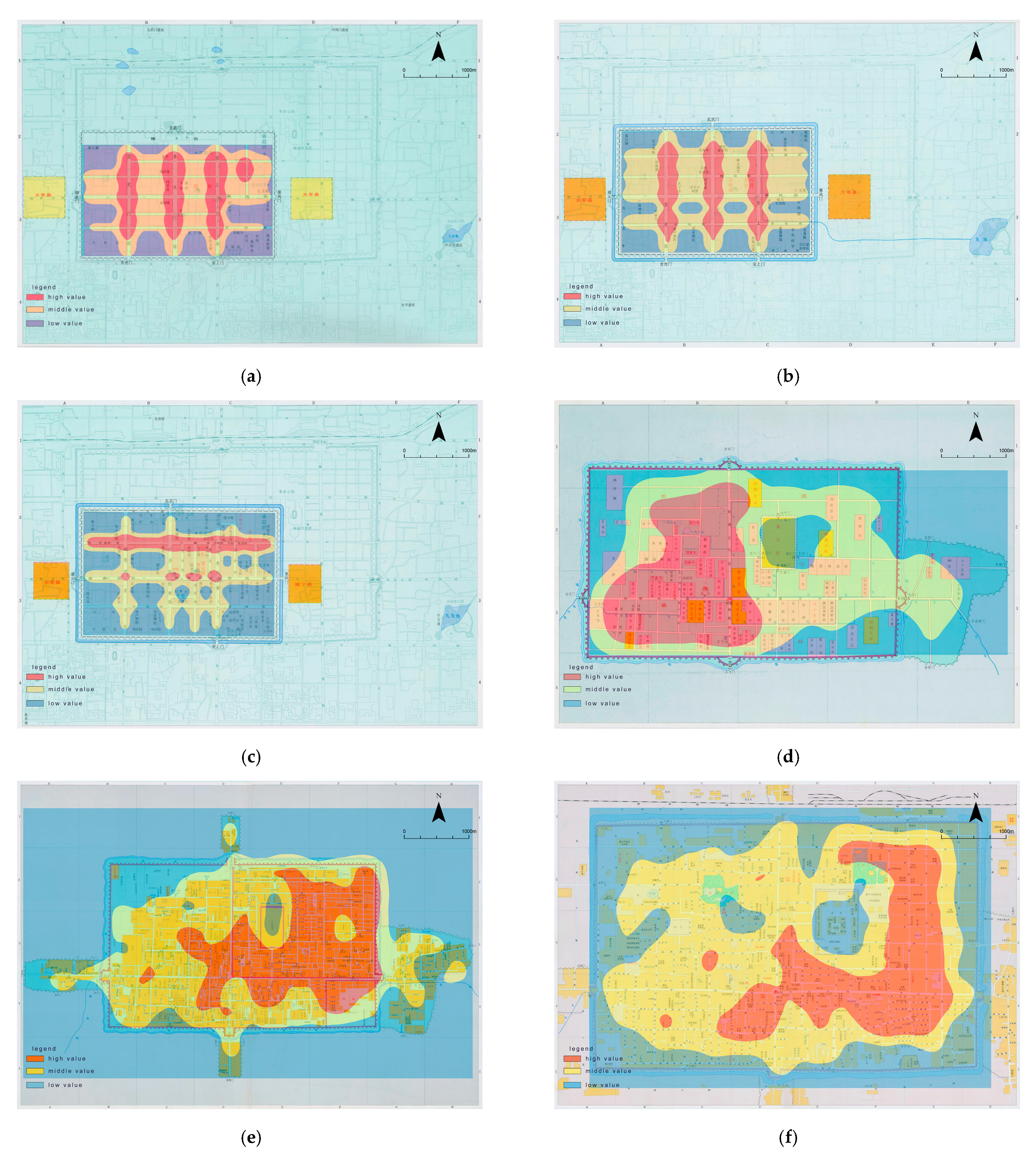

Figure 1 provides a detailed visualization of the spatial relationships and archaeological significance of key historical sites in and around modern Xi’an. The map highlights major urban and archaeological landmarks, including the Xianyang City site, the Chang’an City site, the Qin Liyang site, and the Zhou site, as well as the Ming and Qing Xi’an City and the Tang Chang’an City. These layers illustrate how Xi’an developed as a center of political, economic, and cultural activity across different dynasties.

Figure 1.

Spatial location of Xi’an historic city sites.

This study applies HGIS and quantitative spatial analysis techniques, specifically Space Syntax and KDE, to examine the evolution of Xi’an’s urban structure across six major historical periods: the Five Dynasties (907–960 CE), Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE), Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE), Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE), Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 CE), and the early People’s Republic of China (1949 CE). Each period represents a distinct phase in the city’s spatial organization, shaped by unique political, economic, and cultural forces that influenced its development.

During the Five Dynasties, Xi’an, having lost its prominence as the Tang capital, transformed into a regional military hub with a compact and fortified layout. The emphasis on defense and administration reflected the fragmented political landscape, where competing regimes sought to consolidate control. In the Northern Song Dynasty, the city expanded moderately, with Jingzhaofu becoming an important administrative and cultural center in northwestern China. Economic stability and regional governance were key priorities, leading to the establishment of cultural institutions and administrative offices that contributed to a more decentralized urban layout.

Under the Yuan Dynasty, Xi’an experienced significant reorganization driven by Mongol military strategies. The city’s layout prioritized fortifications and administrative efficiency to maintain imperial control. In contrast, the Ming Dynasty marked a period of considerable urban expansion, characterized by the construction of Xi’an’s outer city walls. These fortifications symbolized the city’s growing importance and facilitated the division of space into residential, administrative, and commercial zones, aligning with the Ming’s centralized governance approach. This period also saw increased trade activity, partly due to Xi’an’s position along the Silk Road.

During the Qing Dynasty, Xi’an’s urban structure became increasingly decentralized. The city adapted to the rise of trade and commerce, with new marketplaces and cultural hubs developing beyond the traditional city center. Religious and cultural exchanges also left a lasting impact, as Buddhist monasteries, Islamic mosques, and Confucian academies played an important role in shaping urban life. In the early People’s Republic of China period, urban transformations were largely driven by industrialization and modernization efforts. The city’s spatial structure evolved to include industrial zones and residential neighborhoods on the periphery, reflecting a shift from a historically centralized layout to a more functional, sectoral model.

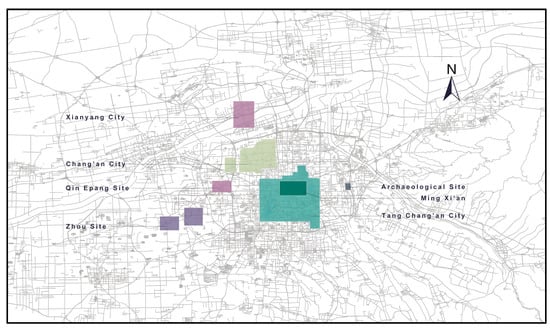

Figure 2 is the Shaanxi Provincial City Map from the collection of the Library of Congress, drawn during the Guangxu period of the Qing Dynasty. The inscriptions on the map describe a major urban reduction carried out in the first year of the Tianyou era (904 CE), during the reign of Tang Zhaozong (Li Ye). This transformation was led by the late Tang warlord and later Later Liang chancellor Han Jian, who significantly downsized the city. As a result, Xi’an was reduced from an imperial capital to a border town during the late Tang and Five Dynasties period. Each of these historical phases contributed to the evolution of Xi’an’s urban landscape while mirroring broader socio-political and economic transformations in Chinese history. Through the use of HGIS, Space Syntax, and KDE, this study highlights how shifts in governance, economic structures, and trade influenced the city’s spatial organization. The analysis provides a multidimensional perspective on Xi’an’s long-term urban development, demonstrating the transition from centralized spatial patterns to a more dispersed, polycentric structure.

Figure 2.

Shaanxi Provincial City Map in the Library of Congress. The meaning of the words in the picture: Inscription accompanying the Map of the Provincial Capital of Shaanxi (1893), offering a historical account of Xi’an’s urban development. It traces the city’s layout to the late Tang dynasty (904 AD) under military governor Han Jian and outlines subsequent modifications by Song, Jin, Yuan, and Ming rulers. By the Ming period, the city had formed a rectangular walled structure with four main gates and corner towers. In the Qing dynasty, a southern extension was added for Han Banner troops, and the city was divided into Mancheng (Manchu garrison city) and Chang’an (Han civilian city). The inscription also provides detailed measurements, administrative boundaries, and lists of streets, wards, temples, and official buildings, reflecting the spatial organization of late imperial Xi’an.

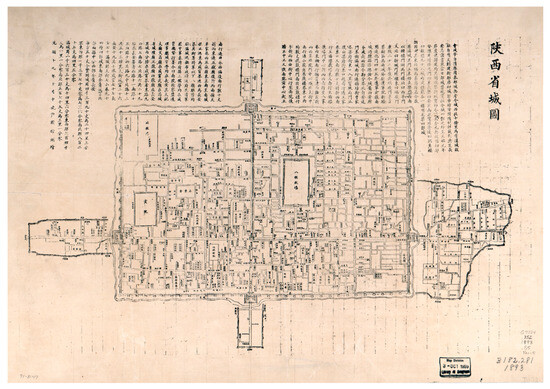

To support this analysis, the study utilizes historical records from the Twenty-Four Histories, alongside vectorized historical maps of Xi’an, to develop a statistical model. This model incorporates key parameters such as city area, estimated population size, levels of technological advancement (e.g., use of stone, bronze, and iron tools), and cultural achievements (e.g., recorded literary works). These factors, quantified using historical records and archaeological data, provide a structured framework for examining the city’s development. Based on this dataset, Figure 3 presents a quantitative visualization of Xi’an’s historical trajectory, demonstrating its growth from early settlements to a highly developed city, particularly during the Tang Dynasty. The model suggests that the most significant urban transformations occurred in the middle historical period, driven by economic expansion, political shifts, and cultural exchanges. After the Five Dynasties period, Xi’an’s development became increasingly complex, transitioning from a highly centralized structure to a more distributed urban form in response to changing governance and trade dynamics. By combining historical documentation with spatial analysis, this study offers a deeper understanding of Xi’an’s urban evolution and provides insights into the long-term interactions between historical forces and urban development.

Figure 3.

Xi’an historical city development level.

Starting from the Five Dynasties provides a crucial foundation for understanding the spatial evolution of Xi’an, as it allows this study to capture the most transformative phases in the city’s development [25]. The Five Dynasties and Northern Song periods feature a centralized urban layout that facilitated political consolidation, while the Yuan Dynasty introduced structural changes in response to Mongol military priorities [26]. The Ming and Qing dynasties marked an era of economic diversification and outward expansion, reflecting Xi’an’s evolving role in the Silk Road trade network [27]. Finally, the early People’s Republic of China period captures the onset of industrialization and modernization, transforming the traditional urban landscape into a more contemporary spatial layout [28]. Focusing on these specific historical periods, our analysis provides a structured approach to examining how shifts in political power, economic imperatives, and cultural dynamics shaped Xi’an’s urban form, offering insights into the city’s modern structure and planning challenges.

By mapping spatial data from these historical periods, this study reveals key patterns in Xi’an’s urban evolution, demonstrating how changes in governance, trade networks, and cultural influences shaped its spatial organization. The integration of HGIS, Space Syntax, and KDE allows for a more comprehensive analysis, uncovering spatial relationships that traditional qualitative approaches often overlook. This quantitative framework highlights the interactions between political authority, economic development, and cultural exchanges, providing insights into the resilience and adaptability of Xi’an’s urban form. The findings emphasize the importance of balancing heritage conservation with urban expansion, offering a framework for historic cities navigating modernization while preserving cultural identity. By combining HGIS with advanced spatial analysis, this study contributes to historical geography and urban studies, offering a structured approach to understanding long-term spatial transformations. The insights gained not only enhance our knowledge of Xi’an’s historical evolution but also provide a practical model for sustainable urban planning, ensuring that historic cities can integrate modern development while maintaining their architectural and cultural heritage (Figure 4).

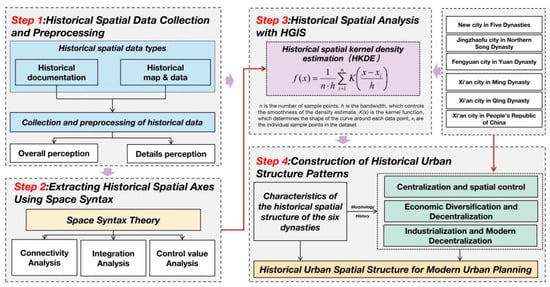

Figure 4.

Historical urban spatial analysis framework.

2. Historical Background

Xi’an, as one of China’s most historically significant cities, has experienced profound transformations throughout its long history, shaped by shifts in political power, economic priorities, and cultural influences. This section traces the city’s spatial evolution across six key historical periods, integrating historical records to highlight major developments that shaped its urban structure and functionality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key developments and spatial features of Xi’an across historical periods.

Five Dynasties Period (907–960 CE): During this politically fragmented era, Xi’an, then known as Chang’an, underwent one of the most drastic spatial contractions in its history. In Tianyou First Year (904 CE), the warlord Han Jian, later a high-ranking official under the Later Liang Dynasty, significantly reduced the city’s size. Historical records state “建罢宫室,坏子城,削其地为农田,城方三十里” (Han Jian dismantled the palaces, destroyed the inner city, and converted much of the land into farmland, reducing the city to 30 li in perimeter). This large-scale reduction transformed Xi’an from a grand imperial capital into a regional military stronghold, reinforcing a compact and defensible layout. The New City, established in Kaiping 3rd Year (909 CE) under Emperor Taizu of the Later Liang, reflected these new priorities, shifting focus from expansive urban planning to military governance and administrative efficiency [29].

Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE): The Jingzhaofu map (Zhenghe 1st Year, 1111 CE, under Emperor Huizong) reflects Xi’an’s role as a key northwestern administrative center despite its diminished status as an imperial capital. The city’s governance system was integrated into the Song administrative framework, which favored regional stability and economic decentralization over centralized imperial authority. Records from the period indicate that “京兆府治,民商渐繁,街肆错列,然不复盛唐旧观” (Jingzhaofu remained a center of administration and commerce, but its former Tang-era grandeur was no longer visible). This period saw the gradual expansion of administrative and cultural institutions, with a more decentralized urban layout emerging. Governance, commerce, and education took precedence over military concerns, setting the stage for later urban transformations [29].

Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE): Under Mongol rule, Xi’an, renamed Fengyuan, underwent another significant restructuring. The Huangqing 1st Year map (1312 CE, under Emperor Renzong) illustrates a fortified, militarized city, reflecting the Yuan Dynasty’s emphasis on stability and military administration. Historical sources describe the following: “元筑重城,军屯其间,以控西域通途” (the Yuan Dynasty reinforced Xi’an’s walls and stationed troops within, securing it as a strategic stronghold for controlling western trade routes). This period saw an increase in military infrastructure and road networks, reinforcing imperial control over key trade and administrative routes [29].

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE): Xi’an experienced significant expansion during the Ming Dynasty, marked by the construction of its outer city walls in Wanli 39th Year (1611 CE). These fortifications, still standing today, not only enhanced the city’s defensive capabilities but also symbolized its increasing importance in regional administration. Historical accounts describe the following: “西安外郭增修,东南北三市兴,通商贾旅” (the outer walls of Xi’an were expanded, and new marketplaces flourished in the east, south, and north, facilitating trade and commerce). This period saw a structured urban layout, with distinct zones for administrative, military, and commercial functions, reflecting the Ming Dynasty’s centralized governance model [30,31].

Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 CE): The Yongzheng 13th Year map (1735 CE) highlights Xi’an’s growing role as a regional economic and cultural hub. By this period, marketplaces and cultural institutions expanded beyond the traditional city core, reflecting increased decentralization. As the Qing government encouraged trade, Xi’an’s economy diversified. Historical sources note, “商贸盛行,回汉共市,庙宇交错,市廛增益” (trade flourished, with Han and Hui merchants coexisting, temples interspersed among markets, and commercial districts expanding). This period integrated new cultural and religious influences, positioning Xi’an as a key player in interregional trade and cultural exchange [32].

People’s Republic of China (1949 CE onwards): The post-1949 era marked a dramatic shift in Xi’an’s spatial organization, driven by industrialization and modernization. The early PRC urban development plans emphasized industrial expansion, leading to the establishment of factories and residential zones on the city’s periphery. Official planning documents describe the following: “西安将以工业基地为中心,扩展城市形态,改造城市旧区,使其达到规划合理有序” (Xi’an was developed as an industrial base, restructuring its urban form with planned redevelopment of old districts.) This transformation aligned with the PRC’s economic policies, prioritizing industrial production and urban modernization while significantly altering the historical spatial framework [33].

Xi’an’s urban evolution has oscillated between centralization and decentralization, each phase shaped by prevailing political, economic, and cultural forces. From the fortified military stronghold of the Five Dynasties to the commercial and cultural expansion of the Qing and ultimately to the industrial reconfiguration under the PRC, the city has demonstrated remarkable adaptability and resilience. By integrating historical documentation with spatial analysis, this study provides a foundation for understanding Xi’an’s urban history and its relevance to contemporary urban planning.

3. Literature Review

The study of urban spatial evolution increasingly relies on the integration of historical maps with advanced analytical tools such as GIS. Historically, maps have served as essential instruments of governance, territorial management, and state-building, providing insights into city planning, infrastructure, and administrative organization [34,35]. However, early research primarily focused on cartographic production methods and the technical aspects of map-making, often overlooking the broader socio-political contexts in which these maps were created. As a result, historical maps were frequently treated as static geographic representations, rather than dynamic artifacts that reflect the ideological, cultural, and power dynamics of their time.

Recent scholarship has redefined the role of maps, emphasizing their significance as socio-political constructs that actively shape urban spaces [36,37]. This shift aligns with the “Spatial Turn” in the humanities, which encourages scholars to view space as an agent of change, rather than a passive setting for historical events [38]. Scholars such as Henri Lefebvre have argued that space is socially produced, meaning that urban configurations both reflect and reinforce power structures, economic systems, and social hierarchies [39]. This perspective has allowed researchers to explore cities as dynamic spatial entities, whose forms and functions evolve in response to shifting political and economic conditions.

The “Spatial Turn” has been particularly influential in the study of Chinese urban evolution, as cities like Xi’an have long served as centers of political administration, economic exchange, and cultural interaction. Traditionally, Chinese urban studies have focused on architectural forms, city layouts, and historical narratives, but recent approaches integrate spatial analysis to uncover hidden socio-political patterns [40]. For example, the Tang Dynasty’s highly centralized grid layout in Xi’an mirrored Confucian ideals of social order and governance, reinforcing imperial authority through its spatial organization. Later periods, such as the Five Dynasties and Northern Song, saw decentralization, reflecting the fragmentation of political power and the shifting role of Xi’an from a national capital to a regional hub [41]. These spatial transformations demonstrate how urban form adapts to broader socio-political dynamics, an idea central to the Spatial Turn.

The adoption of GIS in historical research has enabled scholars to visualize and quantify urban transformation in ways previously impossible. By integrating historical maps with spatial datasets, researchers can now trace patterns of urban growth, decline, and restructuring across centuries [42,43]. Key GIS techniques, such as KDE and Space Syntax, allow for quantitative assessments of spatial relationships, offering insights into how urban spaces were structured to influence social behavior and economic activity. While GIS provides a general framework for spatial analysis, the development of HGIS has been particularly transformative in urban historical studies. HGIS combines historical cartographic data with modern GIS techniques, enabling researchers to map long-term urban transformations and analyze the underlying socio-political and cultural forces [44,45,46]. For cities with extensive historical records, such as Xi’an, HGIS offers a powerful tool for understanding how dynastic changes, trade networks, and governance models influenced the city ’s spatial evolution.

Several major HGIS initiatives have set new standards for historical urban research, including projects such as China Historical GIS (CHGIS), which reconstructs historical administrative divisions and settlement patterns; Great Britain Historical GIS (GBHGIS), which maps long-term economic and social changes; and the Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilizations (DARMC), which provides spatial reconstructions of historical landscapes [47,48]. These projects demonstrate how HGIS can reconstruct historical urban environments, providing a quantitative approach to studying urban morphology, migration, trade, and governance across different cultural and temporal contexts.

Despite its advantages, HGIS faces significant challenges, particularly in terms of historical map accuracy and data consistency. Many historical maps contain geometric distortions, inconsistent scales, and missing spatial details, making geo-referencing a complex task [49,50,51]. Aligning historical maps with modern spatial datasets requires meticulous correction of spatial inaccuracies, as even minor misalignments can lead to significant errors in spatial analysis. Another challenge is the temporal inconsistency of historical maps. Urban landscapes evolve unevenly, and datasets from different historical periods may not be directly comparable [52,53]. This issue is particularly relevant in the study of Xi’an, where spatial transformations occurred at different rates across dynastic transitions. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensuring that HGIS-based reconstructions accurately represent historical urban change.

Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning have further expanded the capabilities of HGIS. AI-powered algorithms now automate the digitization and geo-referencing of historical maps, improving spatial accuracy and efficiency. Machine learning models can analyze large-scale historical datasets, identifying long-term patterns in urban expansion, population migration, and economic activity [54,55,56]. For example, recent studies have used AI-driven pattern recognition to trace Xi’an’s changing trade networks and cultural interactions, revealing deeper insights into how political shifts influenced urban growth [57]. These technologies are paving the way for more sophisticated spatial analyses, allowing researchers to explore historical urban transformations with greater precision and depth.

Table 2 presents a summary of major research reviews in HGIS, highlighting key studies, research outcomes, applied methodologies, and existing challenges. The table underscores the diverse directions in HGIS research and outlines the primary difficulties associated with digitizing and analyzing historical maps. Additionally, it provides an overview of how different research institutions have approached these challenges, offering valuable context for understanding the current state and future prospects of HGIS research.

Table 2.

Overview of major research directions in historical GIS.

Xi’an, historically known as Chang’an, has undergone profound spatial transformations driven by political upheavals, economic reforms, and military conflicts. As a former capital of multiple dynasties, its urban landscape evolved in response to key historical moments that reshaped its spatial structure, governance, and economic functions.

The Tang Dynasty marked the height of Chang’an’s influence, as it became the largest and most systematically planned city in the world. Under Emperor Taizong (r. 626–649 CE) and Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–756 CE), the city adopted a highly structured grid layout, reflecting imperial control and Confucian governance principles. However, the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763 CE) triggered prolonged warfare, leading to economic stagnation, population decline, and administrative fragmentation. The situation worsened with the siege and destruction of Chang’an in 881 CE by Huang Chao’s rebel forces, causing widespread devastation and weakening the city’s political standing. During the Five Dynasties period (907–960 CE), Chang’an never fully recovered. In 904 CE, the warlord Han Jian, serving the Later Liang, ordered large-scale urban downsizing, demolishing key sections of the city and converting land for agriculture, effectively reducing Chang’an to a regional military stronghold.

During the Northern Song Dynasty, the city, renamed Jingzhaofu, remained an important administrative and cultural center despite losing its status as the imperial capital. While Kaifeng became the new political heart of China, Xi’an retained strategic importance as a regional headquarters. The Song era emphasized economic stability and cultural development, leading to the gradual expansion of trade networks, scholarly institutions, and administrative offices. However, territorial pressures from northern nomadic states limited large-scale urban development, and by the end of the Jin-Song Wars (1125–1234 CE), Xi’an’s influence had further diminished.

The Yuan Dynasty restructured the city as a militarized urban center following its capture by Genghis Khan in 1227 CE. Under Kublai Khan, Xi’an (renamed Fengyuan) was transformed into a fortified military and administrative hub, prioritizing defense over commerce and culture. The Ming Dynasty restored Xi’an’s urban framework, most notably with the construction of its city walls (1374–1378 CE), defining the city’s modern spatial boundaries. During Emperor Wanli’s reign (1572–1620 CE), market expansions and administrative reforms reintegrated Xi’an into China’s national trade networks, boosting commercial activity.

The Qing Dynasty saw Xi’an emerge as a vital center for interregional trade and cultural exchange [63]. The Yongzheng Reforms (1723–1735 CE) stimulated merchant activity, leading to the growth of market districts, religious institutions, and financial centers. The city became a key point of connection between eastern China, Central Asia, and the Islamic world, fostering a multicultural urban identity. However, by the late Qing period, political instability and economic decline weakened Xi’an’s position, setting the stage for modern urban transformations. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Xi’an underwent a dramatic shift toward industrialization and modernization. The First Five-Year Plan (1953–1957 CE) led to the development of industrial districts, while rapid urban expansion in the late 20th and early 21st centuries extended the city beyond its historical core. Today, Xi’an balances historical preservation with modern infrastructure, reflecting its enduring legacy as a city shaped by both tradition and transformation.

Despite the rich history of Xi’an’s spatial evolution, much of the existing research has relied on traditional cartographic approaches. These methods provide valuable historical insights but lack the analytical depth needed to capture spatial relationships and transformations over time. By integrating HGIS, Space Syntax, and KDE, this study moves beyond static cartography, uncovering patterns of connectivity, density, and spatial distribution across different historical periods. This approach provides a more nuanced understanding of how political, economic, and cultural forces shaped Xi’an’s urban evolution. While HGIS has significantly advanced historical urban research in Western contexts, its application in Chinese urban studies remains relatively underdeveloped [64]. Existing studies on Xi’an have primarily relied on archival records and traditional maps, which, while valuable, lack the computational power of spatial analysis methods like HGIS. There is a growing need for comprehensive studies that integrate HGIS methodologies to examine long-term urban transformations in Chinese cities [65,66].

This study addresses this gap by applying HGIS methodologies to analyze Xi’an ’s spatial evolution from the Five Dynasties to the early PRC period. By integrating historical maps with spatial analysis techniques like Space Syntax and KDE, this research provides a data-driven examination of how governance structures, economic shifts, and cultural interactions shaped Xi’an’s urban form across different historical periods [67]. The findings contribute to historical geography and urban planning, particularly in balancing urban growth with the preservation of Xi’an ’s cultural heritage [68]. This study also demonstrates how HGIS and spatial analysis can serve as powerful tools for understanding historical urban transformations, offering a framework that can be applied to other historic cities facing similar challenges of modernization and heritage conservation.

4. Data Sources and Methods

4.1. Data Sources

This study primarily relies on The Historical Atlas of Xi’an as its main data source for examining the spatial evolution of Xi’an across multiple historical periods (Figure 5a). This authoritative atlas serves as a comprehensive visual record of the city’s urban development over more than a thousand years, providing detailed cartographic representations of street networks, administrative centers, religious sites, residential districts, and fortifications. The map covers all the important historical stages from the Neolithic period to the modern People’s Republic of China, allowing for a systematic spatial analysis of how socio-political and economic transformations influenced Xi’an’s urban form and functionality. By integrating historical cartography with modern spatial analysis techniques, this atlas provides a valuable dataset for studying long-term changes in urban organization, infrastructure development, and land use patterns.

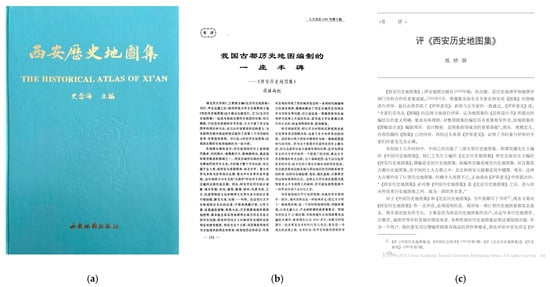

Figure 5.

Historical Atlas of Xi’an and Commentary by Chinese historical scholars. (a) Historical Atlas of Xi’an. (b) Commentary by Chinese scholars. (c) Commentary by Chinese scholars. The meaning of the words in the picture: Figure (a): Cover of the Historical Atlas of Xi’an, compiled by Shi Nianhai, a renowned historical geographer at Shaanxi Normal University, and published by Xi’an Cartographic Publishing House in August 1996. Figure (b): A review article by Professor Situ Shangji (Sun Yat-sen University), published in The Journal of Humanities (1997), which recognizes the atlas as a milestone in the field of historical cartography. Figure (c): A review by Professor Chen Qiaoyi (Zhejiang University), published in Historical Research (1997), praising the atlas as a major achievement of interdisciplinary collaboration between historical geography and cartography.

What sets The Historical Atlas of Xi’an apart from other historical cartographic sources is its rigorous verification process, ensuring a high degree of historical accuracy and reliability (Figure 5b,c). The atlas is based on the meticulous cross-referencing of archival records, imperial edicts, gazetteers, and archaeological surveys, combined with extensive field investigations. This multi-source validation process ensures that the mapped representations of Xi’an’s historical spatial configurations are as precise as possible, reducing distortions commonly found in older cartographic records. Additionally, historical textual sources, including dynastic records, urban planning documents, and merchant registers, have been used to corroborate and refine spatial interpretations, providing deeper insights into the evolution of governance, commerce, and socio-cultural interactions within the city.

The level of detail and accuracy in The Historical Atlas of Xi’an enables researchers to trace the city’s transformation across dynastic transitions, shedding light on how political shifts, economic policies, and cultural influences played a role in reshaping the urban landscape. By leveraging this rich dataset, this study can quantitatively and qualitatively analyze spatial configurations, identifying patterns of continuity, adaptation, and restructuring in response to historical events. Such an approach provides a critical foundation for understanding Xi’an’s resilience as an urban center and its ability to balance tradition and modernization over time [69,70,71].

In this study, selected maps from The Historical Atlas of Xi’an were digitized and integrated into a GIS framework, enabling dynamic temporal and spatial analysis of the city’s urban evolution [72,73,74]. This GIS-based methodology facilitates a layered comparison of historical maps with modern spatial datasets, allowing researchers to examine long-term spatial changes and patterns. By overlaying maps from different dynastic periods, this study provides a multidimensional perspective on how political governance, economic activity, and cultural factors influenced the reconfiguration of urban space in Xi’an. To systematically visualize Xi’an’s spatial transformations, six historical maps from The Historical Atlas of Xi’an were carefully selected, each representing a pivotal period in the city’s long and dynamic history. These maps serve as key reference points, illustrating major transitions in political regimes, economic structures, and cultural influences that shaped the city’s urban morphology over centuries. Each selected period corresponds to a notable phase in Xi’an’s development, marked by distinct spatial reconfigurations that align with the socio-political and economic conditions of the time.

By incorporating these historical maps into a GIS environment, this study enables comparative spatial analysis across different dynasties, providing a detailed examination of how urban governance, trade, cultural exchange, and city planning strategies evolved over time [75,76]. The analysis specifically focuses on patterns of centralization versus decentralization, the spatial distribution of key urban features, and the changing functions of different urban zones.

For example, the proximity of marketplaces to administrative centers reveals how economic policies and trade regulations shaped urban commerce, while the placement of religious sites relative to residential districts reflects the interaction between social organization and cultural institutions. These spatial relationships highlight how governance priorities influenced urban planning decisions, affecting factors such as land allocation, accessibility, and the hierarchy of urban functions. This GIS-based analytical approach not only enhances our understanding of Xi’an’s historical geography but also provides insights into modern urban planning. By uncovering historical spatial dynamics, this study offers valuable lessons on how cities can balance heritage preservation with contemporary urban growth. The integration of HGIS methodologies with a carefully curated historical dataset enables researchers to capture long-term urban transformations, revealing complex patterns of adaptation and continuity. Ultimately, this research underscores the importance of combining GIS-based spatial analysis with historical cartographic sources. It offers a model for studying urban evolution, demonstrating how cities adapt to shifting socio-political and economic landscapes while preserving their cultural and historical identity.

4.2. Data Processing

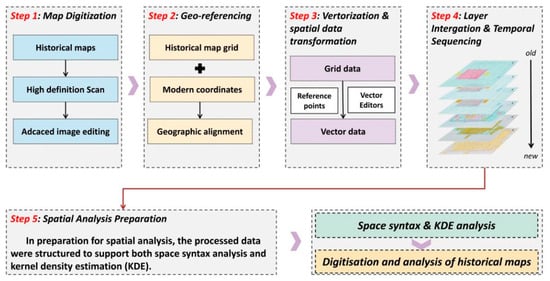

The processing of historical maps was a crucial part of this study, providing the foundation for analyzing Xi’an’s spatial evolution across multiple historical periods. To ensure compatibility with modern GIS platforms and support comprehensive spatial analysis, a systematic workflow was followed, encompassing digitization, geo-referencing, spatial data transformation, and layer integration. This workflow enabled dynamic and comparative analysis of the city’s urban structure over time, offering a nuanced understanding of the political, economic, and cultural forces shaping its transformation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Flow chart for digitization of historical maps.

4.2.1. Map Digitization

The first step in the data processing workflow involved digitizing six representative historical maps, each corresponding to a key historical period in Xi’an’s urban evolution: the Five Dynasties, Northern Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing, and early PRC periods. These maps were carefully selected to capture critical transformations in the city’s spatial organization, ensuring that the dataset reflects major political, economic, and cultural shifts that shaped Xi’an’s urban form. By integrating cartographic evidence from distinct historical phases, this study enables a comparative analysis of long-term urban change.

To convert the historical maps into a digital format, they were scanned at high resolution (using high-precision Contex A72 scanner), preserving intricate details such as street networks, administrative centers, religious sites, residential districts, fortifications, and transportation infrastructure. Since historical maps often contain distortions, faded markings, or scale inconsistencies, particular attention was given to enhancing map clarity and rectifying inaccuracies. Professional image editing (using Adeobe Photoshop 16.0) software was employed to correct distortions, adjust color contrasts, and sharpen faded boundaries, ensuring that the maps’ features were as accurately represented as possible (Figure 7). This preprocessing step was essential to maintaining the spatial accuracy and integrity of the dataset.

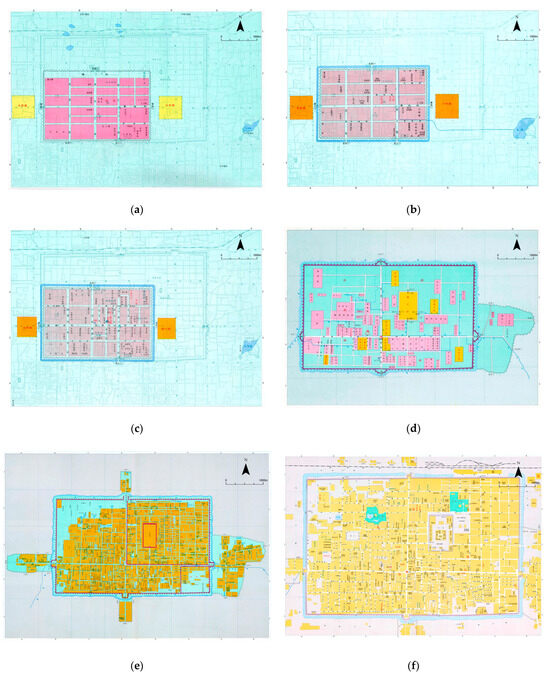

Figure 7.

Historical map of Xi’an during six different dynasties. (a) New City in Five Dynasties. (b) Jingzhaofu city in Northern Song Dynasty. (c) Fengyuan city in Yuan dynasty. (d) Xi’an city in Ming Dynasty. (e) Xi’an city in Qing Dynasty. (f) Xi’an city in PRC.

Following the digitization process, the maps were geo-referenced to align with a modern coordinate system (using Esri ArcGIS 10.8), allowing for precise spatial comparisons between historical and contemporary urban layouts. This process required identifying control points, such as major roads, city walls, and landmark structures, which remained consistent across time periods. These control points were matched with their present-day locations using GIS software, facilitating an accurate overlay of historical spatial data onto modern maps. This digitized and geo-referenced historical map dataset served as the foundation for subsequent spatial analyses, enabling this study to track changes in urban form, connectivity, and land use patterns over time. By ensuring a high degree of cartographic accuracy, this dataset provides a reliable basis for examining Xi’an’s spatial evolution, offering insights into how dynastic priorities, economic conditions, and cultural influences have shaped the city’s long-term urban development.

4.2.2. Geo-Referencing

Geo-referencing, a critical step in the data preparation workflow, involved aligning the historical maps with a modern coordinate system to enable spatial overlay and comparative analysis. Using ArcGIS 10.8, the Geo-referencing tool utilized Xi’an’s city walls as a stable reference point. These city walls, a prominent and enduring feature in Xi’an’s urban landscape, provided a reliable spatial anchor due to their relative consistency over centuries. Key locations on the historical maps were identified and matched to corresponding points on the city walls, ensuring precise alignment within the GIS framework. Multiple control points along the city walls were employed to refine the alignment, while root mean square error (RMSE) calculations were conducted to verify accuracy and minimize spatial errors. This rigorous geo-referencing process ensured that the historical maps were correctly positioned, providing a reliable foundation for spatial analysis and temporal comparisons across different periods.

4.2.3. Vectorization and Spatial Data Transformation

Following geo-referencing, the key spatial features from the historical maps—such as streets, city walls, administrative zones, and commercial districts—were extracted and vectorized from raster images into vector data formats. This transformation enhanced the usability of the data within GIS environments, facilitating advanced spatial analyses. For instance, street networks were vectorized as line data, which allowed for topological analyses such as connectivity and accessibility calculations in space syntax models. Similarly, city walls and functional areas were represented as polygons to support KDE analysis of residential and commercial area distributions. This vectorization process not only improved data management but also enabled greater precision and flexibility in analyzing spatial relationships across Xi’an’s historical maps.

4.2.4. Layer Integration and Temporal Sequencing

Once vectorized, the spatial data from each historical period were integrated into a comprehensive GIS database and organized into distinct temporal layers. Each layer represented the spatial configuration of Xi’an during a specific dynasty, capturing the evolving structure of the city over time. These temporal layers facilitated a dynamic analysis of urban changes, allowing for comparative studies of spatial configurations across different periods. The integrated GIS layers included detailed classifications of urban features, such as residential areas, marketplaces, religious institutions, and administrative zones. This categorization supported independent and combined analyses of these features, enabling the identification of functional zones and tracking their evolution. By organizing the data into temporal layers, this step provided a clear framework for examining how Xi’an’s urban structure adapted to changing political, economic, and cultural dynamics.

4.2.5. Spatial Analysis Preparation

To prepare the data for advanced spatial analysis, pre-processing steps were conducted to optimize the dataset for space syntax and KDE methods. For space syntax analysis, the street networks underwent topological pre-processing to ensure an accurate representation of connectivity and accessibility within each historical map. This allowed for the identification of key spatial axes and movement patterns. For KDE analysis, residential and commercial area data were processed with density parameters tailored to capture their spatial distribution across Xi’an’s historical layout. This step enabled the analysis to reflect patterns of population concentration, economic activity, and land use, providing deeper insights into the functional organization of the city over time.

Through this data processing workflow, historical maps were successfully converted into spatial datasets compatible with a modern GIS environment, enabling accurate and stable support for multi-period analysis of Xi’an’s urban spatial structure. These steps ensured that historical maps from different eras could be effectively overlaid and compared, providing deeper insights into the evolution of Xi’an’s spatial layout and the political, economic, and cultural factors influencing its transformation.

4.3. Methods

This study applies spatial analysis techniques to investigate the evolution of Xi’an’s urban form over more than a millennium, from the Five Dynasties to the early Peoples Republic of China. By digitizing and geo-referencing historical maps, GIS allows for a dynamic and precise examination of changes in the city’s spatial configuration over time. This study employs two primary spatial analytical methods within the GIS framework: Space Syntax and KDE. These methods are instrumental in uncovering the spatial dynamics that have shaped Xi’an’s urban development across different dynasties, offering insights into the relationship between urban form, social behavior, and political power.

4.3.1. Space Syntax

Space Syntax is a well-established methodology developed to quantify and analyze spatial configurations in urban environments [77]. It offers a theoretical and practical framework for understanding how the layout of space influences human movement, social interaction, and economic activity. Originally developed by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson at University College London, Space Syntax has since been widely adopted in both contemporary and historical urban studies [78].

In the context of historical urban research, Space Syntax is particularly valuable for analyzing street networks and public spaces within ancient cities. By breaking down urban layouts into axial lines (representing streets or movement routes), the method allows researchers to calculate spatial metrics such as connectivity, integration, and control value. These metrics provide insights into the accessibility of certain areas, the centrality of the streets, and the influence of particular spaces within the broader urban network.

In Space Syntax analysis, connectivity, integration, and control value are three key spatial metrics that help assess how urban layouts influence movement, accessibility, and spatial hierarchy(Table 3). These metrics are particularly valuable in historical urban studies, as they allow researchers to quantify how cities evolved across different historical periods and how political, economic, and social changes shaped their spatial configurations. In the case of Xi’an, applying these metrics provides insights into how different dynasties structured the city, prioritized urban functions, and adapted to socio-political shifts.

Table 3.

Concepts and formulas in Space Syntax.

Connectivity measures the number of direct connections a particular space, such as a street or plaza, has to its adjacent spaces. A highly connected space allows for efficient movement and access, making it an ideal location for marketplaces, government offices, or key intersections. In contrast, spaces with low connectivity are often more secluded, which can indicate residential neighborhoods, religious complexes, or restricted administrative areas. In Xi’an’s historical evolution, Tang Dynasty Chang’an exhibited high connectivity within its structured grid, ensuring smooth circulation between administrative, commercial, and residential areas. However, during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the city’s defensive walls and controlled gates altered connectivity patterns, shifting commercial activity to designated market districts.

Integration assesses how centrally located a space is within the entire urban network, determining how easily it can be accessed from all other spaces. A space with high integration is likely to serve as a major hub of social, political, or economic activity, while spaces with low integration tend to be peripheral or isolated areas. This metric is particularly relevant in understanding how urban planning reflected governance structures. For instance, in Tang Dynasty Xi’an, the Imperial Palace and surrounding government offices exhibited high integration, reinforcing the centralization of imperial control. In contrast, during the Yuan Dynasty, the Mongol rulers reorganized the city with a militarized layout, leading to lower integration values in civilian zones and an emphasis on strategic defensive planning rather than commercial accessibility.

Control value quantifies the degree to which a space regulates access to its neighboring areas, reflecting the dominance or influence of specific streets or intersections in shaping urban movement. High control values indicate locations that mediate access between multiple spaces, such as city gates, main roads, or fortification entry points. In historical Xi’an, major city gates and commercial roads held high control values, as they were critical for managing trade, taxation, and security. For example, in Ming–Qing Xi’an, the city’s walls and gates tightly controlled access, leading to the development of market clusters just outside the walled areas, reinforcing a decentralized trade model. Conversely, in earlier dynasties, such as the Northern Song dynasty, major streets connected directly to administrative centers, reflecting a more open urban structure before later dynasties imposed stricter spatial regulations.

By applying these three Space Syntax metrics to Xi’an’s historical maps, this study quantitatively assesses how changes in political rule, economic policies, and cultural priorities influenced urban accessibility and organization. The results provide a systematic and empirical approach to understanding how dynastic transitions shaped the city’s movement corridors and functional zoning, offering valuable insights for both historical urban studies and modern urban planning strategies.

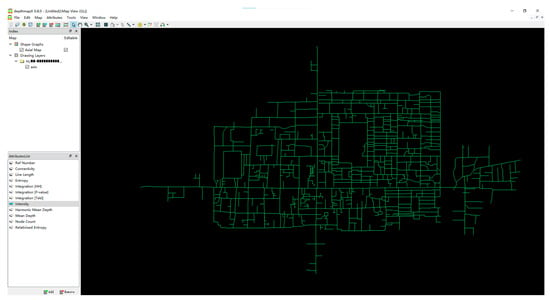

In this study, Space Syntax is applied to historical maps of Xi’an to analyze the evolution of its street network over time. By calculating metrics such as integration, the study identifies accessible areas that likely served as hubs of economic or political activity, revealing shifts in spatial organization across dynasties. Space Syntax quantifies these changes, providing insights into how urban form adapted to political and economic shifts. The vectorized axial line data were processed using Depthmap X-0.8.0 software developed by UCL (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Analysis of Xi’an in the Qing Dynasty using spatial syntax software.

4.3.2. Kernel Density Estimation

KDE is a widely used non-parametric statistical method for estimating the probability density function of a dataset. In spatial analysis, KDE is applied to visualize the density distribution of specific urban features, such as marketplaces, religious institutions, administrative centers, and residential areas [79,80,81,82,83]. By generating a continuous density surface, KDE helps identify hotspots of activity and spatial clustering that may not be evident from raw data alone. This technique is particularly valuable in historical urban research, as it allows researchers to analyze how the concentration of urban functions evolved across different historical periods. The one-dimensional KDE formula is typically expressed as

where:

- is the estimated density at point x;

- is the number of sample points;

- is the bandwidth, which controls the smoothness of the density estimate;

- is the kernel function, which determines the shape of the curve around each data point;

- are the individual sample points in the dataset.

The bandwidth parameter () plays a critical role in KDE because it determines the scale at which density is estimated. A smaller bandwidth results in fine-grained density variations, revealing localized clustering, while a larger bandwidth produces a smoother, more generalized density surface that highlights broad trends. In this study, Silverman’s rule-of-thumb bandwidth was selected due to its well-documented reliability in density estimation [84]. Silverman’s rule is given as

where is the standard deviation of the dataset. This method was chosen over alternative bandwidth selection techniques (such as the Scott’s rule or fixed-bandwidth KDE) because it offers a balanced trade-off between detail and generalization, ensuring that KDE captures both fine-scale clustering and broader spatial patterns in historical Xi’an.

In this study, KDE is applied to the spatial data extracted from digitized historical maps of Xi’an to analyze the distribution and evolution of key urban elements, including religious institutions, administrative centers, marketplaces, and residential areas. By mapping the density of these features across different historical periods, KDE enables a quantitative assessment of how urban functions clustered and dispersed over time, offering a spatially driven approach to understanding historical urban transformation. When applied to historical maps, KDE provides a detailed visualization of how urban functions were distributed in different dynastic periods. For instance, KDE analysis of religious buildings during the Tang and Ming dynasties reveals distinct patterns in the spatial organization of religious institutions. During the Tang Dynasty, religious structures were highly concentrated around the imperial palace, indicating state sponsorship of Buddhism and Daoism, as well as their integration into the imperial administrative structure. In contrast, by the Ming and Qing Dynasties, religious buildings became more widely dispersed, reflecting a shift towards localized religious centers and community-based worship spaces, possibly due to changing governance policies and decentralization of religious influence.

Similarly, KDE analysis of marketplaces allows for a reconstruction of economic activity distributions across different dynastic periods. In the Tang era, markets were highly centralized within the walled city, aligning with the strict state-controlled economic system of the time. However, in later periods, particularly in the Ming and Qing dynasties, KDE results show a clear shift of commercial hubs towards the city peripheries, indicating an expansion of merchant activity beyond the administrative core, a pattern influenced by increasing private trade and commercial diversification along Silk Road networks. The use of KDE also provides insights into the expansion of residential areas over time. In early dynasties, housing clusters were concentrated within fortified city walls, reflecting an imperial-centric, hierarchical urban structure. However, by the PRC period, KDE reveals a significant outward expansion of residential zones, consistent with the industrialization-driven suburbanization that took place in the mid-20th century. This transition highlights how economic and industrial developments reshaped the spatial organization of Xi’an, leading to a decentralized urban growth model.

To ensure the reliability and robustness of the KDE results, this study incorporated multiple validation techniques, following best practices in spatial analysis research [85,86,87,88]. The validation process focused on cross-referencing KDE findings with historical sources, archaeological evidence, and additional spatial analyses to confirm the accuracy and interpretability of the results.

A key aspect of validation involved comparing KDE results with existing historical studies on Xi’an’s urban evolution. By cross-referencing spatial clustering patterns with historical research on administrative, commercial, and religious development, this study ensured that KDE findings align with well-documented historical events and urban planning trends [89,90]. For example, KDE results indicating high-density religious clusters near the imperial palace in the Tang Dynasty were supported by historical records describing the prominence of Buddhist and Daoist temples within the central administrative districts. Another critical validation method involved archaeological comparisons. KDE-generated density clusters for marketplaces and administrative centers were evaluated against archaeological findings to confirm spatial consistency. In cases where discrepancies between historical maps and archaeological records were observed, KDE outputs were adjusted to account for potential cartographic distortions in historical sources, improving spatial accuracy.

To assess the stability of KDE results, a sensitivity analysis of bandwidth selection was conducted. Since bandwidth size directly influences the level of smoothing in KDE density surfaces, multiple bandwidth values were tested to examine how density estimates varied with different spatial resolutions. Among the tested approaches, Silverman’s rule-of-thumb bandwidth produced the most consistent and interpretable density patterns, ensuring that KDE captured both localized spatial clustering and broader urban expansion trends. Alternative bandwidth selection methods, such as Scott’s rule, were tested but found to overgeneralize spatial distributions, losing finer urban clustering details that were essential for historical analysis.

Additionally, KDE findings were validated against historical texts and dynastic gazetteers, which provided descriptive accounts of urban configurations. The density surfaces generated for administrative centers, marketplaces, and residential zones were cross-checked with historical records documenting urban zoning regulations and commercial activities. For example, KDE results indicating high concentrations of commercial activity outside city gates in the Ming and Qing periods were supported by textual descriptions of government-imposed trade restrictions within walled city limits, which led to the development of peri-urban markets.

To further reinforce the reliability of spatial interpretations, KDE results were cross-validated with Space Syntax analysis. Since Space Syntax quantifies spatial accessibility, this comparison ensured that KDE-generated high-density clusters aligned with highly integrated urban spaces. For example, areas identified as major commercial zones in KDE analysis consistently corresponded to streets with high integration values in Space Syntax calculations, confirming that these locations functioned as urban centers facilitating high levels of economic and social interaction.

Through this approach, KDE proved to be a powerful methodological tool for reconstructing historical urban landscapes, offering a quantitative and spatially explicit framework for analyzing how cities evolved under different governance structures and socio-economic systems. The integration of KDE with the Historical GIS and Space Syntax methodologies in this study not only enhances the understanding of Xi’an’s long-term urban changes but also provides a model for future research in historical urban geography.

4.4. Integration of Space Syntax and KDE

The integration of Space Syntax and KDE offers a powerful approach for analyzing the spatial dynamics of historical cities [91,92]. While Space Syntax provides a detailed analysis of the accessibility and connectivity of urban spaces, KDE complements this by visualizing the density and distribution of urban features. By combining these two methods, this study is able to generate a comprehensive understanding of how Xi’an’s urban form evolved in response to changing political, economic, and cultural conditions.

The integration of Space Syntax and KDE in this study involves a step-by-step process to analyze Xi’an’s urban spatial dynamics in detail. First, Space Syntax metrics—connectivity, integration, and control value—were calculated for the city’s spatial axes using Depthmap software. These metrics represent the accessibility, centrality, and influence of specific street segments within the urban network. To enhance the analytical precision, the calculated values were weighted according to the length and importance of each axis. This weighting process ensures that longer and more central streets are given proportional significance in the spatial analysis.

Next, the weighted Space Syntax results were linked to the GIS attribute table, enabling spatial alignment with Xi’an’s historical maps. This integration facilitated the use of KDE within ArcGIS 10.8 to visualize the distribution and density of urban features. KDE was applied to the aggregated metrics, producing heat maps that depict areas of high connectivity and influence within the city. These visualizations reveal how street network accessibility corresponds to population density, marketplaces, and administrative zones over different historical periods.

This method offers a clear, data-driven approach to understanding functional changes in Xi’an’s urban layout. For instance, in analyzing the Ming Dynasty’s expansion, the method identifies how newly constructed city walls influenced movement patterns and how residential and commercial zones adjusted spatially in response. This combined analysis of spatial accessibility and density through Space Syntax and KDE provides a comprehensive understanding of where and how urban changes occurred, illustrating their impact on the city’s social and economic life. The process demonstrates the utility of integrating quantitative metrics with GIS tools to uncover nuanced spatial relationships in historical urban studies.

5. Discussion

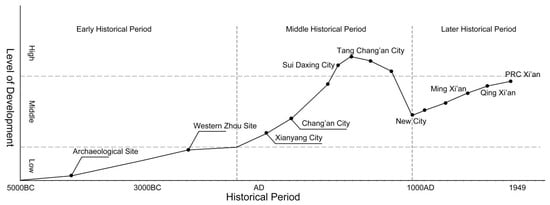

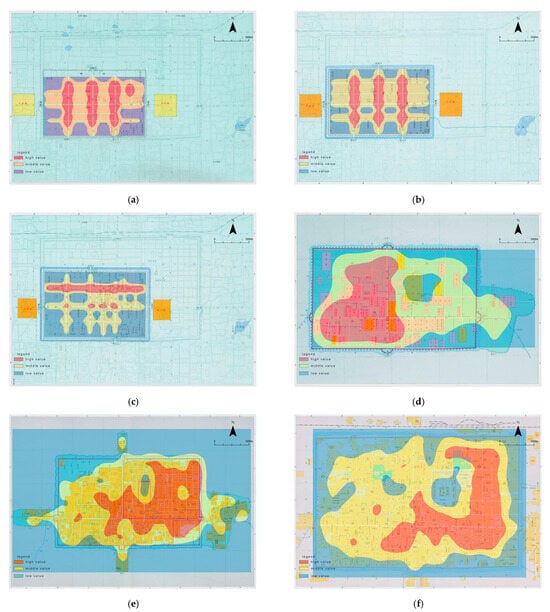

The six maps produced through kernel density analysis depict the evolution of Xi’an’s urban spatial structure, illustrating a clear transition from a highly centralized system to a more dispersed and decentralized network over time (Figure 9). Initially, the central core of the city exhibits the highest integration, with a dense network of streets and high connectivity concentrated along the major east–west axes, reflecting the city’s strategic centralization for administrative and military purposes. As the city expands in subsequent periods, integration begins to spread outwards, with middle-value areas growing and new zones of activity emerging in previously peripheral regions. Over time, the influence of the core diminishes, and multiple sub-centers appear, suggesting a decentralization of urban functions and a diversification of economic and cultural activities. By the final map, Xi’an’s spatial network has developed into a more balanced structure, where high-value pockets of integration are dispersed across the city, reducing reliance on the historic core and creating a modern, polycentric urban fabric. This transformation illustrates the city’s dynamic adaptation to political, economic, and infrastructural changes over time.

Figure 9.

The evolution of Xi’an’s urban spatial structure. (a) New City in Five Dynasties. (b) Jingzhaofu city in Northern Song Dynasty. (c) Fengyuan city in Yuan Dynasty. (d) Xi’an city in Ming Dynasty. (e) Xi’an city in Qing Dynasty. (f) Xi’an city in PRC.

The spatial evolution of Xi’an, as analyzed through Space Syntax and KDE, reveals how political governance, economic shifts, cultural influences, and environmental constraints have collectively shaped the city’s urban structure over more than a millennium. By integrating quantitative spatial analysis with historical records, this section examines key patterns of centralization, decentralization, and urban restructuring across different dynastic transitions. The results highlight how imperial authority and administrative functions influenced spatial organization in early periods, while economic diversification and trade networks drove decentralization in later centuries. This interdisciplinary approach not only deepens our understanding of historical urban transformation but also provides valuable insights for contemporary urban planning and heritage preservation, emphasizing the long-term interactions between spatial organization and socio-political change.

5.1. Centralization and Spatial Control in Early Periods

The spatial structure of Xi’an during the Five Dynasties, Northern Song, and Yuan periods was shaped by centralized governance, military priorities, and Confucian urban planning, reinforcing the city’s role as an administrative stronghold and frontier defense hub. KDE and Space Syntax metrics reveal that high-integration zones were concentrated around imperial palaces, military garrisons, and administrative centers, illustrating how spatial planning served as a tool of governance.

During the Five Dynasties, the fall of the Tang Dynasty resulted in political fragmentation, prompting military leaders like Han Jian (韩建) to dismantle large portions of Tang Chang’an (904 CE) for better defense (Si Maguang’s Zizhi Tongjian (资治通鉴)). KDE maps confirm this transformation, showing a contraction of high-integration areas to the city core, aligning with the era’s emphasis on fortified, compact urban structures. Under the Northern Song, Xi’an was no longer an imperial capital but remained an administrative center (Jingzhaofu, 京兆府). Unlike Kaifeng, the Song capital, which developed into a commercial metropolis, Xi’an’s urban form remained rigidly hierarchical, reinforcing state control rather than trade expansion (Meng Yuanlao’s Dream of the Eastern Capital (东京梦华录)).

With the Yuan Dynasty, Mongol rulers militarized Xi’an’s layout, prioritizing defensive infrastructure over economic decentralization. KDE maps reveal that integration values peaked around government–military compounds, distinguishing Xi’an from Yuan-era Hangzhou or Dadu (Beijing), which experienced commercial decentralization (Yuan Shi (元史)). The northwestern sectors of Xi’an show higher control values, mirroring the defensive spatial structures of other frontier cities, such as Samarkand under the Timurids and Baghdad under the Abbasids, where fortifications were central to urban strategy.

Beyond military and administrative control, Confucian urban planning shaped Xi’an’s hierarchical spatial structure. Treatises like Kao Gong Ji (考工记) emphasized that capitals should be designed to reflect cosmic harmony and social order, a principle evident in Xi’an’s strict zoning of political and administrative functions. Compared to European and Islamic medieval cities, such as Cairo and Damascus, which saw trade-driven organic urban growth, Xi’an remained a pre-planned, state-controlled city. KDE analysis confirms this, showing higher-density commercial and religious nodes in cities like Bukhara and Baghdad, while Xi’an’s high-integration zones were strictly tied to government centers.

Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production further contextualizes this phenomenon. Xi’an’s urban space was “conceived” by rulers rather than shaped by organic social interactions, reinforcing imperial authority and social hierarchy. Unlike Beijing’s Forbidden City during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, which was a ceremonial and political center, Xi’an remained a regionally significant but functionally limited city, as reflected in KDE results, where state-controlled areas retained high integration even as late as the Yuan period.

Comparing Xi’an’s trajectory with Chang’an in the Tang Dynasty underscores its decline from a cosmopolitan hub to a militarized stronghold. Unlike Kyoto, which retained its imperial layout despite decentralization, Xi’an’s centrality diminished as governance shifted toward regional administration. KDE comparisons with Samarkand reveal a key difference—while both were Silk Road cities, Samarkand evolved into a trade-driven urban form, whereas Xi’an remained strictly hierarchical and government-centric.

The Five Dynasties, Song, and Yuan periods marked Xi’an’s transition from a vibrant imperial capital to a tightly controlled administrative–military city. Unlike Kaifeng, Hangzhou, and Samarkand, which embraced decentralized economic structures, Xi’an’s KDE and Space Syntax results confirm persistent centralization around government and military centers. This rigidity ultimately limited its ability to evolve into a major economic hub, yet it ensured that Xi’an remained strategically significant as a political and military command center in northwestern China.

5.2. Economic Diversification and Decentralization in the Ming and Qing Periods

The Ming and Qing periods marked a fundamental transformation in Xi’an’s spatial structure, driven by economic diversification, urban decentralization, and increasing cultural pluralism. Unlike earlier dynasties, which prioritized centralized governance, these centuries saw the rise of merchant-led commerce, spatially distinct religious institutions, and socio-economic stratification, leading to a shift from a monolithic urban core to a polycentric urban system.

Findings from KDE and Space Syntax analysis reveal that high-integration zones expanded beyond the traditional administrative center, forming secondary commercial and cultural hubs. This transformation aligned with broader Ming–Qing economic policies, which encouraged private market expansion and local governance autonomy. Historical records, including the Ming Shilu (明实录) and Qing-era Xi’an Gazetteer (西安府志, compiled in the Kangxi and Jiaqing reigns), document how Xi’an adapted to these structural shifts, growing into a multi-functional urban space rather than a singularly administrative capital.

A major spatial transformation in the Ming Dynasty was the construction of Xi’an’s outer city walls (1611 CE, Wanli reign), which expanded the urban footprint and enabled the formation of new commercial districts beyond the inner city. KDE results confirm the development of dense trade hubs near key gates, such as the West and South Gates, reinforcing Xi’an’s role as a Silk Road transit point. Unlike earlier periods, where the government monopolized key commodities, the late Ming saw increasing merchant autonomy, as documented in Xi’an’s local gazetteers. This decentralization mirrored broader national trends described in Timothy Brook’s The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China, where urban economies shifted away from state-controlled commerce toward privatized trade networks.

Comparison with other inland Ming cities, such as Chengdu and Kaifeng, reveals differences in urban economic structures. While Kaifeng’s economic zones remained integrated within its imperial framework, and Chengdu developed a mixed economy of agriculture and trade, Xi’an became more transit-focused, benefiting from interregional commerce rather than local production. The Qing-era Shaanxi Gazetteer (陕西通志, Qianlong reign) describes Xi’an as a critical distribution center, linking Sichuan, Gansu, and Shanxi trade routes, rather than an independent production hub.

Religious institutions played a significant role in shaping Xi’an’s decentralized urban landscape, contributing to the formation of distinct cultural–urban zones beyond the political–administrative core. KDE analysis shows a clustering of high-density religious buildings in areas outside the traditional state governance centers, confirming the emergence of multi-nodal urban networks.

One of the most notable transformations was the expansion of the Great Mosque of Xi’an (西安清真大寺) during the Ming Dynasty. According to Islamic inscriptions and local gazetteers, this period saw a growth in the city’s Hui Muslim population, reinforcing Xi’an’s connection to the broader Islamic world via Silk Road trade. Compared to earlier dynasties, where Islamic institutions remained confined to designated districts, the Ming–Qing periods saw Muslim traders and scholars play an increasingly central role in urban commerce and cultural exchange. Similarly, Confucian academies and Buddhist temples expanded beyond the core administrative region, creating secondary cultural zones. The Wenchang Temple (文昌庙) and Guandi Temple (关帝庙) near the South Gate became major urban nodes, serving both religious and economic functions. Unlike earlier dynasties, where religious institutions were more directly controlled by the state, the Ming–Qing period saw them operate semi-independently, supported by merchant donations and local patronage.

Comparative analysis with Beijing and Suzhou highlights different trajectories of religious decentralization. In Beijing, religious institutions remained integrated within imperial planning, whereas Suzhou’s temples were closely tied to elite literati culture. Xi’an, in contrast, saw religious institutions function as both spiritual and economic hubs, integrating local commerce with transregional religious networks. This reflects Doreen Massey’s theory of “a global sense of place”, where Xi’an’s spatial structure was shaped by both local cultural needs and its broader Silk Road identity.

The late Ming and Qing periods also witnessed greater socio-spatial stratification, with merchant elites, scholar–officials, and lower-income artisans occupying distinct neighborhoods. The Kangxi-era Xi’an Gazetteer describes how wealthy trading families established exclusive residential quarters near major commercial arteries, forming a proto-bourgeoisie class that influenced urban planning. KDE analysis supports this, showing higher-density residential clustering near economic hubs, while lower-density integration occurred in peripheral labor settlements.

This pattern aligns with Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of social space, where urban layouts reflect evolving class hierarchies. Compared to earlier dynasties, where administrative elites occupied centralized housing districts, the Qing period saw a more spatially diverse city, where economic status—rather than state employment—determined residential location. A comparison with Yangzhou and Guangzhou underscores Xi’an’s distinct socio-spatial trajectory. In Yangzhou, wealthy merchant elites lived within state-administered quarters, whereas in Xi’an, they remained separate from government institutions, reinforcing the city’s increasing economic autonomy. Unlike Guangzhou, which developed merchant enclaves linked to maritime trade, Xi’an’s merchant quarters remained tied to overland commerce, reflecting its inland Silk Road position.

Space Syntax analysis confirms that Xi’an transitioned from a single-core model to a more polycentric structure, with emerging economic and religious hubs forming new urban centers of activity. KDE results reveal that secondary commercial, residential, and religious nodes became spatially connected through newly built road networks, marking a departure from earlier periods of monolithic administrative control.

Unlike earlier periods, where integration values were highest within the imperial core, Qing-era KDE results show multiple high-integration clusters distributed throughout the city, confirming a shift toward a decentralized economic landscape. This aligns with urban transformations seen in Nanjing and Chengdu, where commercial zones became increasingly autonomous from state institutions. Comparative analysis with Chongqing highlights another key difference: while Chongqing’s decentralization was driven by industrialization, Xi’an’s transformation remained rooted in traditional Silk Road commerce, making it a hybrid model of economic diversification and cultural continuity.

The Ming and Qing periods marked a profound restructuring of Xi’an’s urban identity, shifting from a centralized political city to a decentralized commercial and cultural hub. Unlike earlier dynasties, where imperial governance dictated urban form, these centuries saw the rise of merchant-led economic zones, class-based residential clustering, and the spatial diversification of religious institutions. Comparing Xi’an with Beijing, Suzhou, Yangzhou, Chengdu, and Guangzhou, we see how regional differences shaped urban expansion strategies. While some cities developed through imperial mandates or maritime commerce, Xi’an’s transformation was driven by inland trade, religious networks, and market liberalization. By the end of the Qing Dynasty, Xi’an had evolved into a multi-functional urban center with diverse economic, cultural, and social functions, solidifying its role as an inland Silk Road metropolis. KDE and Space Syntax results confirm that this transformation was not just historical but spatially embedded, demonstrating how urban form adapts to shifting political, economic, and cultural forces.

5.3. Industrialization and Modern Decentralization in the PRC Period