Abstract

Unitised integration is a management model used to address the fragmentation of multiple management entities in complex environments. Small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) safety alliances play an important role in centralised management and cost reduction in the safety management of SMEs, which are large in number, widely distributed, and small in volume. On the basis of the investigation and analysis of the current situation of SMEs’ own safety management and external supervision, as well as the market situation of safety service institutions, this paper explores the fragmentation problem of SMEs’ safety management. An idealised framework for the unitised integration of safety management in SMEs is proposed theoretically, and the model is tested and its limitations are discussed through a field investigation of the operational mechanism and problems of the SME Safety Alliance in Pukou District, Nanjing City, China, taking the SME safety alliance as a case study, with a view to proposing policy recommendations for the optimisation and promotion of the model. The unitised integration of safety management can help promote the adaptation of safety service supply and demand, thereby reducing the cost of safety management for SMEs, promoting the effective implementation of the main responsibility for safety, alleviating the pressure of production safety supervision, and ultimately promoting the further improvement of safety supervision and management systems for SMEs.

1. Introduction

As important pillars for promoting economic development, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a pivotal role in economic development. Owing to their small size and large number, safe supervision is difficult, and overcoming the problem of SME safety management has become an inextricable topic of work safety. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) report shows that in industrialised countries, SMEs account for an average of approximately 40% of the workforce, and in developing countries and newly industrialised countries, the proportion is as high as 60%. According to relevant EU research, SMEs generally suffer from a lack of resources for safety management. Moreover, EU research indicates that SMEs frequently suffer from insufficient safety management resources—many pursue a ‘low-end’ business strategy, with owner-managers possessing limited knowledge, awareness, and capacity in safety practises. Therefore, with globalisation and economic integration, safety in SMEs has become an important part of safety governance at the grassroots level and an important factor in sustainable social and economic development. Effectively reducing the incidence of accidents in SMEs is one of the major issues that the world needs to address together.

Effective SME safety management directly contributes to sustainable development by reducing workplace accidents and aligning with international sustainability policies. In particular, it supports several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), thereby promoting healthier work environments and resilient economic growth.

To address the problems of safety management in SMEs, three main responses have been proposed by the current academic community. One is the integration of safety supervision: Heikkila (2010) noted that Western countries have changed the traditional, empirical supervision of SMEs in the past, shifted the focus of supervision from post-accident tracing to pre-accident prevention, and made use of network technology to carry out supervision [1]. Li (2008) researched the current situation of production safety in small and medium–sized private enterprises in Zhejiang and mentioned that a four-party comprehensive supervision system should be established, i.e., the supervision and management departments of production safety as the theme, combined with the supervision system of industry and commerce, quality inspection, and labour safety departments as a whole [2]. Second, the integration of safety service supply: Lanzano (2024) stressed the importance of local governments encouraging the growth of safety intermediary service organisations and implementing strict regulations to ease the burden on government safety management efforts [3]. Sun et al. (2020) proposed the construction of a dual safety management and service model of ‘safety steward + government’ and ‘safety steward + enterprise’ with a safety steward as the core, exploring the content of professional and technical services over the whole life cycle of the government and enterprises with key issues [4]. Third, when the demand for safety services is integrated, Joas (2013) argues that there is a lack of cooperation between SMEs in China and that, in terms of the safety management of SMEs, it is necessary to integrate the resources, knowledge, and capabilities involved in the safety management of SMEs through easy-to-use, easy-to-disseminate, and easy-to-improve methods and to cooperate well in the management of safety between enterprises [5].

However, existing models have also revealed clear limitations in practice: for instance, Heikkila’s model incurs high implementation costs, Mohannak’s approach is difficult to widely promote because of insufficient government support [6], and Joas’s research indicates that SMEs often resist adopting unified safety management measures. Moreover, current studies have not adequately examined how fragmentation in SME safety management negatively impacts overall safety governance efficiency. Consequently, unitised integration has emerged as a promising innovative approach, aimed at consolidating fragmented safety resources on both the supply and demand sides to enhance overall efficiency and reduce costs.

All of the above response options integrate different subjects of safety management in SMEs, and this process is essentially the process of constructing an emergency management unit; multiunit composite governance is the basic trend of grassroots governance reform, and by unitising and integrating the fragmented subjects of safety management, the effectiveness of their management can be improved to achieve cost reduction and efficiency.

In summary, this study argues that a unitised integration approach to SME safety management is essential for addressing the fragmentation of safety practises at the grassroots level. This approach not only ensures the accessibility of safety service supply but also meets the appropriateness of demand by optimising the matching between individual SMEs and collective safety service units under government guidance. Third-party safety service organisations and SMEs are integrated based on regional proximity and enterprise similarity, thereby enhancing overall management efficiency and reducing costs.

In light of these foundational insights, the study then shifts its focus toward examining the practical implications of this integration strategy. Based on the above, the study explicitly addresses the research question: “How does unitised integration improve SME safety efficiency?” and posits the hypothesis that “unitised integration can enhance safety compliance while reducing safety management costs”. Furthermore, Pukou District has been selected as the case study due to its representative regional characteristics, easy access to interviewers, and favourable policy environment that actively supports innovative safety management practises. While its conclusions offer a reference value for similar regions, generalizability remains limited by variations in local policies across China and requires further validation through cross-regional studies. To investigate the fragmentation issue in SME safety management, this paper constructs a unitised integration model and empirically examines it through the case of the Pukou District SME Safety Alliance, aiming to identify its limitations and propose relevant policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Safety management is a crucial component in maintaining a healthy and secure work environment, particularly within SMEs. These organisations face unique challenges due to their size, resources, and organisational structure, which often make safety management more vulnerable to external and internal pressures. In the literature review section, we examine studies related to safety management, unitised integration management and safety services agency. By reviewing previous research, we explore the gaps that this study seeks to address to better understand the conditions for the unitised integration of safety management.

2.1. Safety Management in SMEs

Safety management in SMEs is a critical aspect of ensuring the well-being of employees and maintaining a safe work environment. Several studies have explored different facets of safety management in SMEs across various industries and countries. Specifically, it includes a study of the vulnerability of safety management in SMEs, intrinsic influencing factors and external policies.

In the area of vulnerability to safety management in SMEs, some studies have noted the vulnerabilities of management in SMEs, where occupational safety and health are influenced by economic factors, highlighting the challenges faced by these businesses in ensuring a safe work environment [7]. Some scholars have explored health and safety risk normalisation in the construction industry of Nigeria, shedding light on the factors that promote such normalisation. The study highlighted the importance of addressing these risks to improve safety practises within SMEs operating in the construction sector [8].

In terms of intrinsic influences on safety management in SMEs, Dugolli (2021) explored the occupational health and safety situation in SMEs in Kosovo, highlighting contextual factors, barriers, drivers, and intervention processes that affect safety practises [9]. Motivation plays a crucial role in shaping safety practises within SMEs, as discussed by Khan et al. (2021). Their conceptual framework emphasises intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors, appropriate health and safety policies, the work environment, operative characteristics, and management supervision as key components influencing safety outcomes [10]. Abdullah et al. (2022) focused on safety management practises in Malaysian Bumiputera SMEs and investigated the relationship between safety management practises and safety performance, including factors such as entrepreneurs’ commitment, safety training, worker involvement, safety communication, rules, procedures, and promotion policies. Institutional context also plays a significant role in influencing safety management practises within SMEs [11], as demonstrated by Kravariti et al. (2021) in their study on talent management in internationally oriented Greek SMEs [12]. The study revealed that Greece’s institutional context presents important yet nondeterministic hurdles for talent management practises in SMEs. Additionally, Subramanian et al. (2022) examined the contribution of organisational learning and green human resource management practises to the circular economy in manufacturing SMEs, highlighting the interrelationship between these factors and ranking their driving and dependency power [13].

In terms of external policies for safety management in SMEs, Manna et al. (2021) delved into the role of familiness in determining ethically rooted human resource management practises among SMEs, emphasising the significance of business ethics awareness and the formalisation of HR policies [14]. In the realm of safety management, Latif et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between safety management practises (SMPs) and safety behaviour (SB) among outdoor participants [15]. The study recommended the implementation of policies to safeguard participants and prevent accidents and injuries. Additionally, Kim et al. (2021) focused on psychosocial risk management plans in organisational working environments, highlighting the effectiveness of changes in work organisations, dispute resolution procedures, education programmes, and notifications of psychosocial risks to worker safety and health [16]. On a broader scale, Pedi et al. (2021) discussed resilience through entrepreneurship in the context of the European External Action Service (EEAS), exploring the potential of fostering resilience through entrepreneurial initiatives [17]. This interdisciplinary research project sheds light on the concept of resilience across different strategic documents within the EEAS. Furthermore, Bartosch (2021) touched upon compliance management in German family businesses, emphasising the growing external pressure for SMEs to adhere to legal frameworks and regulations [18].

Compared to traditional safety integration models (e.g., Heikkilä’s network-based supervision and Mohannak’s intermediary-focused approach), the unitised integration model in this study addresses fragmentation through the systemic consolidation of supply-demand dynamics. While prior models emphasised unilateral interventions (e.g., government mandates or SME self-regulation), our approach uniquely bridges regulatory, supply, and demand units, aligning with China’s grassroots governance reforms. This contrasts with EU initiatives like France’s OiRA tool, which relies on digital standardisation but lacks cost-sharing mechanisms.

2.2. Unitised Integration Management

Unitised integration management has become an important concept in several fields, especially in management-related disciplines. This review synthesises the key points in the relevant literature on unitised integrated management.

The concept of unitisation can be traced back to the late 19th century in Europe and America. Initially, in the field of education, large-unit teaching was clearly defined and applied as a specific educational concept. A new chapter in the application of unitisation in industrial engineering management was initiated by Elia (2020) when unitisation was applied to the construction of information systems in unitised factories through the grouping of key departments into independent management units [19].

In recent years, research on unitisation has continued to deepen in the field of education. Smith et al. (2023) noted that curriculum design based on unitisation can significantly enhance students’ ability to solve complex problems by integrating multidisciplinary knowledge, breaking disciplinary boundaries, and allowing students to exercise critical thinking and innovation skills in integrated learning tasks [20]. This further deepens the application of unitisation in education and teaching, emphasising integrated learning activities to enhance students’ overall understanding and application of knowledge.

In the field of public administration, the integration of unitisation has also made significant progress. Multiunit composite governance is the basic trend of grassroots governance reform. It is suggested by Xu et al. (2024) that in the management of industrial and trade enterprises, although various safety accident prevention systems have been implemented, the independence of these systems often results in management conflicts, inefficiencies, and resource waste, imposing significant risks and constraints on safety work [21]. Tao (2022) noted that the ‘unit’ represents a specific spatial unit of governance and that unified emergency response is the process of comprehensively coordinating the behaviours of different sectors within the unit to achieve consistent management objectives, which not only improves the efficiency of emergency response but also optimises the allocation of resources in the process of disaster management [22].

Jones and Brown (2021) mentioned in their study on urban planning and management that the adoption of a unitary management model can help optimise the spatial layout of a city and improve its sustainable development by integrating the resources and functions of different areas [23]. Yu et al. (2024) proposed a technical policy system for the risk classification control and construction of unitised hidden danger investigation and collaborative management of petrochemical enterprises based on the characteristics of petrochemical enterprises and combined with innovative safety management models [24].

In financial portfolio management, unitised integration enables investors to pool resources and make investment decisions on the basis of risk-adjusted returns rather than individual investments. The unitised fund structure helps in distributing assets across various investment categories, making it easier to manage risk and maximise returns. In addition, in their study of financial risk management, Green and Black (2020) reported that a unitary risk management framework is able to cope with market volatility more effectively. Dividing financial operations into different units according to risk characteristics for targeted risk assessment and control can reduce systemic risk and safeguard the sound operation of financial institutions [25].

Overall, unitised integration management plays a crucial role in optimising management processes, improving resource allocation efficiency, and achieving consistent management objectives in various fields. In industrial engineering, it helps enterprise information system construction and management; in public management, it improves emergency management and grassroots governance; and in the financial industry, it optimises asset investment and management. As the research and practice of unitary systems continue to evolve, they have the potential for wider application and more efficient management in terms of cross-disciplinary integration, digital transformation, and response to complex and changing market environments and social needs.

2.3. Safety Services Agency

Safety service agencies play a pivotal role in all areas of society today, with a wide range of operations covering key aspects such as risk management, emergency response, and service quality assurance.

In the field of education, safety services within colleges and universities are committed to maintaining campus safety and stability. At Stony Brook University, campus risk is comprehensively managed through the implementation of a campus-wide management model encompassing emergency management, traffic, and parking services [26]. The University of Louisville’s risk management services, on the other hand, focus on centralising oversight of the enterprise risk programme, particularly in insurance-related matters, to safeguard the financial backing of campus safety [27]. Clemson University’s Safety Services provide assistance in identifying and evaluating institutional and operational risks, contributing to the campus safety system [28].

Nonprofit and professional organisations are integral to the field of safety services. Nonprofit risk management centres provide services such as assessment, support, and guidance aimed at enhancing safety risk management in institutions [29]. The Risk Management Institute of the United States (RIMS) strongly promotes the development of safety risk management by providing resources, organising events, and conducting training to help all types of organisations improve their safety awareness and response capabilities [30]. Government departments are equally important in safety services. The Department of Technology, Management and Budget (DTMB) provides services related to safety risk management, such as vehicle accident reports and insurance applications, to ensure public safety in areas such as transport [31]. With the increase in cyber threats, safety service agencies have expanded their focus to include digital risk management. Governments and corporations are investing heavily in cybersafety frameworks to protect sensitive data and critical infrastructure [32].

Third parties play an important role in the management and assessment of safety services. In healthcare, third-party evaluators have highlighted the importance of factors such as compensation, practice safety, and social trust in improving the safety and quality of healthcare services through their evaluation of the China Healthcare Improvement Initiative [33]. In terms of personal electronic health record services, third-party sponsorship is more likely to gain the trust of participants because of its professionalism and independence, thus guaranteeing the safety and reliability of the service [34].

In addition, research on safety service agencies covers a wide range of areas. For example, the development of emergency towing service organisations and the implementation of the National Competence Plan for Senior Officials are directly related to the quality of transport emergency safety services [35]. A study of the impact of the quality of services provided by operational control centres on the work commitment of airline employees provides a direction for the improvement of aviation safety services [36]. A study of practitioner support for women with complex past experiences highlighted the importance of safety for special groups in social services [37]. Research on the development of a culture of organisational safety in the U.S. Forest Service has helped to improve safety services in forest resource protection [38].

Overall, safety service agencies play a key role in different industries and fields to ensure the safety and stability of society. The involvement of third parties in the management and assessment of safety services has a profound impact on improving service quality, and research in various fields provides valuable insights for safety service agencies to continuously improve their service delivery and safety.

In summary, the literature reveals that while safety management in SMEs faces significant challenges, including fragmentation in both safety services and supervision, existing models fail to adequately address these issues. This study aims to bridge these gaps by proposing a unitised integration model that consolidates safety resources. The following research questions are addressed: How does unitised integration improve safety efficiency in SMEs? Can unitised integration reduce safety management costs while enhancing compliance?

3. Research Background and Hypotheses

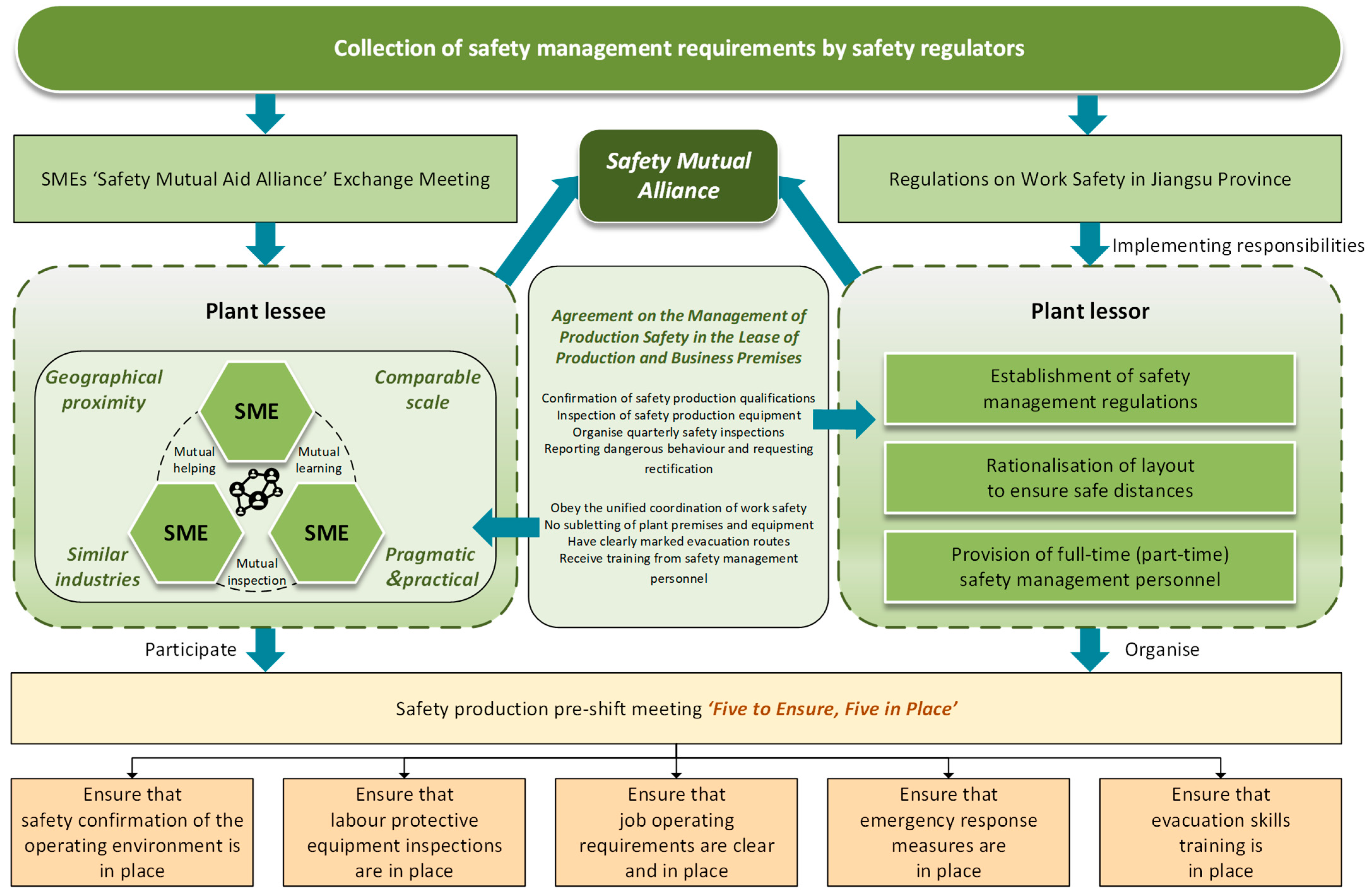

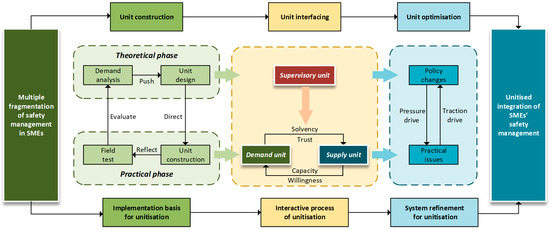

SMEs are recognised as playing a pivotal role in economic construction and are considered one of the key pillars of modern economic development. Accompanying the rapid development of the private economy, an increase in the number of SMEs has been observed, and various ‘fragmentation’ characteristics—including diverse distribution, product variety, limited economic scale, numerous enterprises, and weak safety awareness—have gradually emerged. Consequently, challenges in the identification of safety risks, the prevention of safety accidents, and other aspects of safety management have arisen in SMEs. Badea et al. (2024) points out that many SMEs do not see the value of investing in occupational health and safety because they see it as unprofitable, not only because of a lack of accountability and insufficient incentives for management, but also because they do not fully understand the risk of accidents [39]. Some SMEs have begun to seek help from external safety service organisations, but they face problems such as insufficient funds and poor services. Therefore, the dilemma of safety management in SMEs is summarised in this study as a ‘multiple fragmentation’ problem encompassing three dimensions: safety supervision, safety service supply, and safety service demand. The multiple types of safety management fragmentation in SMEs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Multiple types of safety management fragmentation in SMEs.

3.1. Fragmentation of Safety Regulations

- (1)

- Fragmented regulatory standards and inadequate regulatory systems. In China, national norms and local standards do not explicitly specify provisions for fire safety management applicable to SMEs and family workshops. Conversely, certain local standards such as the ‘Code for Fire Safety Management of Small Commercial Outlets’ (DB3304/T051-2020) and the ‘Code for Fire Safety Management of Family Hotels’ (DB13/T2639-2017), while highly specialised in content, are characterised by a high degree of generality, thereby adversely affecting the operability of fire safety management for SMEs. Consequently, fire safety management in family workshops remains poorly executable.

- (2)

- Broken regulatory skills and improved regulatory capacity. Emergency management departments for SMEs to carry out safety inspections often perform simple checks of business rules and regulations, supervise the implementation of the main responsibility of the enterprise, address specific safety issues such as a lack of professionalism, and acknowledge the need for safety experts to assist in supervision and inspection. Simultaneously, industry authorities and local government supervisory agencies exhibit lax and lenient enforcement, and the supervision forces are unprofessional, reluctant to impose penalties, and lack punitive measures, which results in insufficient deterrence regarding production safety risks. Before the commission of law enforcement, most of the hierarchical classification of SMEs in accordance with supervision involves local management, that is, streets and development zones, park management, and safety supervision departments for SMEs whose ability constraints are very low.

- (3)

- Broken regulatory resources and mismatch of regulatory scale. Following the institutional reform, the number of personnel in the emergency management department increased; however, due to an expanded range of administrative, office, and other functions related to production safety supervision, the overall capacity for production safety oversight has weakened and become diluted. As a result, the widely distributed and numerous SMEs require substantial investment in supervisory resources, yet the available resources remain severely mismatched and vulnerable to regulatory loopholes.

3.2. Fragmentation of Safety Services

- (1)

- Fragmentation of industry standards and difficulty in implementing service norms. Some safety service organisations help SMEs cope with inspections on the one hand and participate in and expand their business with the help of law enforcement inspections on the other hand. SMEs incur fees; however, third-party service organisations do not provide comprehensive, on-site guidance—from management to field staff—but instead issue a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution that is not tailored to the enterprises’ operational realities and fails to enhance their safety management practises.

- (2)

- Broken qualification audits and inconsistent access standards. In actual service, some of the organisation’s safety experts exist while earning expert fees from government departments while taking the opportunity to collect guidance and assistance fees from enterprises. Moreover, inconsistencies have been observed in the understanding of safety standards among different safety experts, resulting in non-uniform advice and causing SMEs to struggle with accurately addressing the deficiencies in guidance.

3.3. Fragmentation of Safety Service Needs

- (1)

- Fragmentation of responsibility and difficulty in dividing safety responsibility. Due to their limited scale, SMEs often operate from leased premises, thereby involving both lessors and lessees in their safety management responsibilities. As early as 2021, the Jiangsu Provincial Safety Commission issued the Notice on Comprehensively Strengthening the Implementation of the Main Responsibility of Enterprises to Deeply Promote the Special Improvement of Safety Production, which requires that Party A (the lessor of the factory), as a lessor, should also implement the main responsibility and make it clear that the factory-leased premises, even if it is not involved in the actual use of the site, also need to actually bear the responsibility for safety management. However, both Party A (the factory’s lessor) and Party B (the factory’s lessee) generally exhibit a lack of safety awareness and unclear delineation of responsibilities, as evidenced by lease contracts that emphasise contract value over the assignment of safety obligations. Consequently, both parties are reluctant to invest in safety measures to address the hidden issues identified during inspections.

- (2)

- Fragmented economic income, making it difficult to meet safety inputs. SMEs’ registered capital is small and has small profits, whereas the price of safety services and equipment is high. SMEs undertake safety training, set up safety positions, and have a weak ability to purchase safety equipment. When the standards set by management are high, SMEs meet the safety standards of objective difficulty. Simultaneously, the principal decision makers in SMEs often prioritise economic development and profit maximisation, while undervaluing safety production. Consequently, they are inclined to reduce investments in safety management personnel and equipment in an effort to lower operational costs, based on the perception that the risks associated with production and safety are minimal due to the enterprise’s small scale and limited equipment. Moreover, many SMEs, often characterised by family-run operations, tend to rely on acquaintances, relatives, or part-time safety administrators with limited professional expertise.

4. Methods

4.1. Research Steps

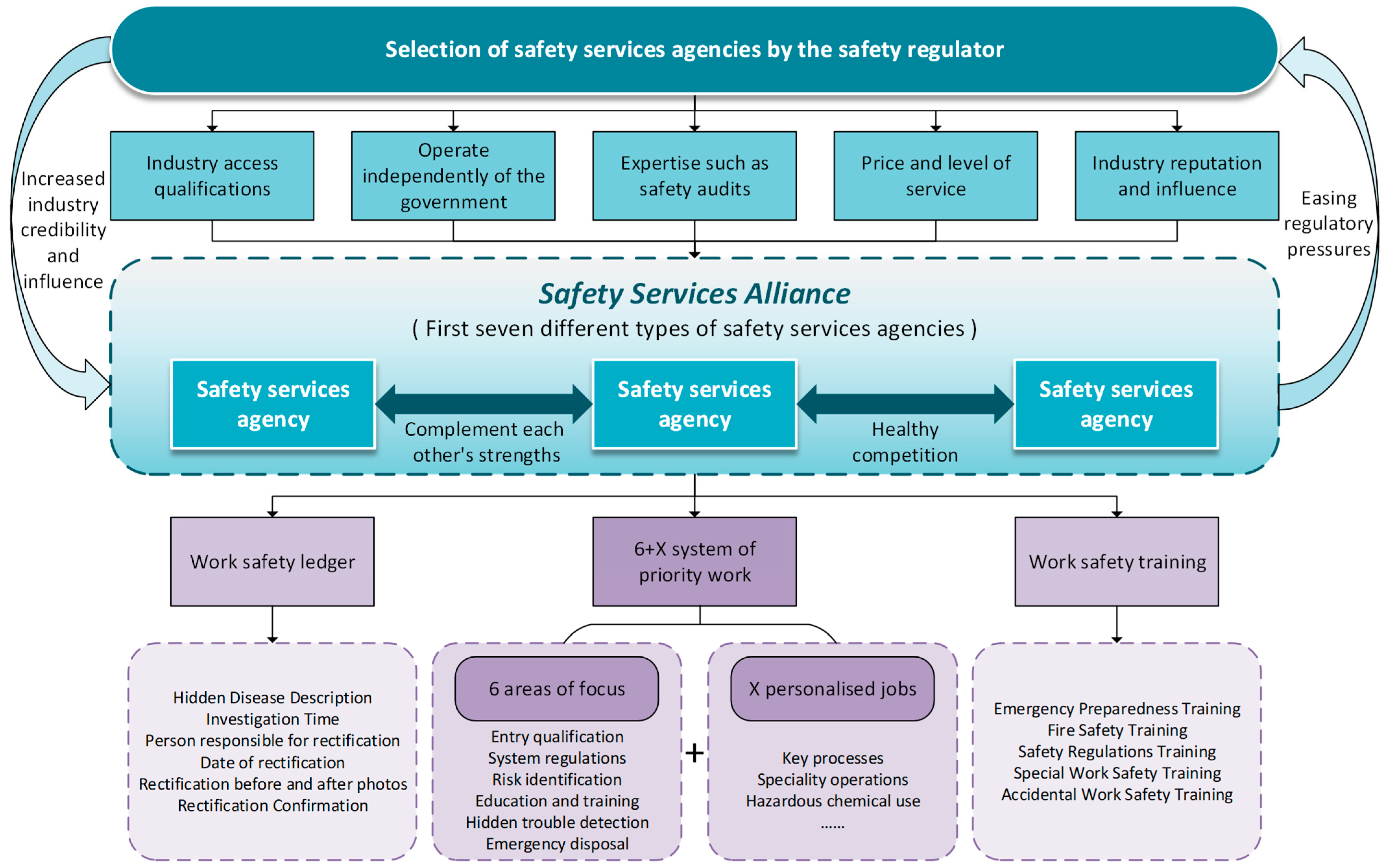

This study first adopts the inductive method to dig deeper into the causes of the phenomenon of safety performance and combines relevant academic literature, articles, and books through extensive literature reading to lay a theoretical foundation for the study. Moreover, combined with field visits, we learned about the current dilemma of safety management in SMEs and analysed the multiple fragmented conditions of safety management in SMEs from the three aspects of safety supervision, safety demand, and safety service. Through theoretical modelling, a research framework for the unitised integration of safety management is constructed on the basis of established theories and concepts. A case study of the safety alliance of SMEs in Pukou District, Nanjing City, China, is then conducted, which mainly covers the interaction process between units, the operation mode of safety mutual aid alliances, and safety service alliances, to test the application of the unitised integration model in practice and to discover its limitations. Finally, on the basis of these limitations, we propose targeted improvement suggestions so that through this series of steps, we can systematically explore the basic principles, limitations, and improvement directions of unitised integration to improve the safety of SME production. The research steps are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research steps.

4.2. Research Framework

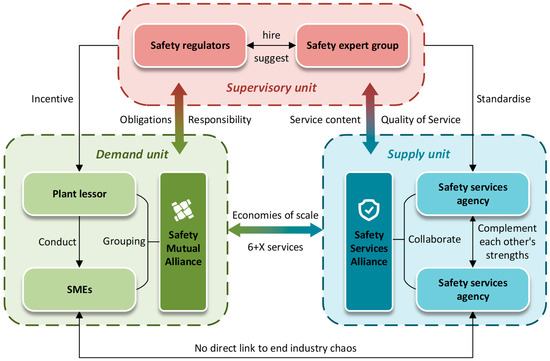

The analysis of the fragmentation of safety management in SMEs reveals that SMEs are often in the blind spot of regulatory authorities under safe supervision, and their governance is difficult. Unitised integration has become an inevitable choice for SMEs to ‘reduce costs and increase efficiency’ in the process of SME safety management. In view of this, this paper aims to construct an analytical framework for the unitised integration of SMEs’ safety management. Unlike the traditional unitisation of monitoring and warning, rapid response, and efficient disposal as the goal of the division of the basic unit of emergency management, this study proposes that the main body of emergency management, which focuses on the main body of safety supervision, the main body of safety service supply, and the main body of safety services demand the main body of safety management of the unitisation of the integration model. Therefore, the three links of ‘unit construction—unit docking—unit optimisation’ are incorporated into the conditions and integration process of the safety management unit of SMEs in light of the supply and demand of public services. In the analysis, the analytical framework of the unitised integration of safety management in SMEs is initially constructed to explain the practical process and internal mechanism of unitised integration to promote the safety of production in SMEs. The unitised integration mechanism is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Unitised integration mechanism.

Unit construction serves as the cornerstone of unitised integration. Computer software unitisation methodologies typically entail systematic processes of requirement analysis, unit design, organisational implementation, and iterative optimisation to enhance code readability, maintainability, and testability. Similarly, safety management unit construction analysis may adopt this systematic framework. Initial construction challenges arise from multidimensional fragmentation within SME safety management, complicating coordination between safety service supply and demand ends, thereby necessitating the establishment of dedicated supply–demand units. Based on endogenous safety management demand identified through investigations, the theoretical model unit design was refined. Guided by integrated model assessment feedback, organisational unit construction and pilot testing were initiated to address evolving demand requirements.

After completing the construction of the two units on the supply side and demand side of safety services, the docking of the two units is a dynamic adaptation process. The essence is to radiate the safety service demand of individual SMEs outwards, ‘connect the dots to form a line’, and reach a common and shared safety management mode with the lessor of the ‘plant lessor’. The ‘factory-in-factory’ lessor then ‘gathers lines into surfaces’ as a unit and interfaces with the supply unit composed of multiple third-party safety service organisations. Among them, the supply capacity, willingness to supply and pay, and trust and commitment between the supply and demand units are the keys to influencing the docking of the supply and demand units of SMEs’ safety management. Third-party safety service providers in the supply unit of interest for acquisition and social responsibility awareness often affect the possibility of unit docking; therefore, in the process of unit docking, there is a need for government regulation, guidance, and thus the formation of the ‘profit increment’ business model and ‘semivolunteer’ unique supply unit. Therefore, in the process of unit matching, it is necessary to form a business model of ‘profit increment’ and ‘semivoluntary’ unique supply units through government regulation and guidance. In addition, it is necessary to deepen the trust and commitment between units to continuously promote the interaction between supply and demand units.

In the process of unit docking, the vertical synergy of the regulatory unit layer by layer forms the policy normative system, whereas the two horizontally juxtaposed supply and demand units generate new practical problems through continuous interaction. Under the macroguidance of the policy system, the responsibilities of the supply and demand units are implemented, forming an externally pressed driving mechanism; at the same time, the supply and demand units, out of their own needs for economic benefits and influence, coincide with the guidance of the regulatory unit, forming a traction-driven mechanism, and ultimately optimising the process of modularisation and integration step by step.

4.3. Case Selection and Survey

The purpose of this study is to explore the intrinsic mechanism of the SME safety alliance that assists the safety management of SMEs through the unitised integration of the supply and demand units of safety services. In view of the complexity of the research problem and the dynamics of the research situation, combined with the advantages of single-case studies, which have the advantage of deeply demonstrating the development process of things, as well as the causal mechanism, this study is carried out mainly through longitudinal single-case studies. Through the presentation of the case phenomenon and the deep description of the inner mechanism embedded in the case, the logic and inner mechanism of the occurrence of the safety alliance of SMEs are further explored to complete the goal of the production of theoretical knowledge from the case story.

At the early stage of the research, this study reviewed relevant theoretical literature and policy documents to understand in detail the background, formation mechanism, construction history, benefits and future development trends of SME safety alliances in Pukou District of Nanjing City, reviewed domestic and international academic journals, and summarised them to make theoretical preparations for future practical activities. The reasons for selecting the case of the safety alliance of SMEs in Pukou District are as follows: first, the principle of typicality is followed. The case study involved 252 SMEs in Pukou District, selected based on geographic proximity, industry type (e.g., construction, retail, catering), and a minimum one-year participation in the Safety Alliance. Data were gathered from government reports, alliance records, and semi-structured interviews with 15 key stakeholders, including regulators, SME owners, and third-party service providers. Second, it follows the principle of enlightenment. Comparing the seven relevant cases in Shandong, Zhejiang, and Fujian Provinces, Pukou District combines the Safety Service Alliance on the supply side of safety services with the safety mutual aid alliance on the demand side, which breaks through the traditional prevention and control mode of the government unilaterally and is of inspirational significance.

On the basis of the perfect theoretical reserve, this study conducts interviews with relevant staff of the safety alliance of SMEs in Pukou District of Nanjing, relevant personnel of the Emergency Management Bureau of Pukou District of Nanjing, responsible persons of a number of SMEs, and legal persons of safety service organisations by means of onsite research and expert interviews to explore, under the model of unitised integration, how to form a safety alliance among the government, safety service enterprises, and SMEs, and its operation mode.

4.4. Summary of Methods

To investigate the effectiveness of unitised integration in SME safety management, this study employs a case study approach, focusing on the SME Safety Alliance in Pukou District, Nanjing. The research questions address how unitised integration improves safety efficiency and reduces costs. The study adopts an inductive method for theoretical groundwork, supplemented by field visits, interviews, and theoretical modelling to construct the unitised integration framework. The research framework incorporates the analysis of fragmentation in safety management, with the aim of understanding how integrated safety services can optimise SME safety practises and management costs. The case study of the Pukou District SME Safety Alliance serves to test this framework in a real-world context, providing insights into its practical application and potential limitations.

5. Practical Application of Unitised Integration in SMEs

SMEs are considered to play an important role in expanding employment, stimulating market growth, and enhancing the livelihoods of individuals in China, and they are recognised as indispensable components of the market economy. According to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the number of SMEs in China exceeded 52 million by the end of 2022, with an average of 23,800 new enterprises set up every day. On the other hand, it is also indisputable that SMEs have many hidden risks and poor safety management. The fragmentation of safety service resources, insufficient capacity and investment in SMEs’ safety management, and the lack of safe production supervision are identified as the primary factors contributing to fragmented safety management within SMEs. This requires the integration of safety resources through multiprincipal coordination, a reduction in safety inputs through the adaptation of supply and demand scales, and the restraint of noncompliant behaviours through policy and institutional incentives. In recent years, to strengthen the safe supervision of SMEs, various parts of the country have adopted ways of forming alliances to optimise the safe supervision of SMEs, with marked effects, and have stepped out of the unitised integration of safety management. To investigate this phenomenon and elucidate its underlying logic, the safety alliance of SMEs in the Pukou District of Nanjing was selected as a case study.

The Pukou District of Nanjing is located in the northwestern part of the city. With respect to the standards set by the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Development and Reform Commission and other parts of China, there are a total of 272 SMEs in the district, which are distributed in different industries, such as building materials, catering, and garments. The common characteristics of SMEs are small registered capital and small profits, while the price of safety services and equipment is high. SMEs are weak in their ability to undertake safety training, set up safety positions, and purchase safety equipment, while the standards set by management authorities are high, and it is objectively difficult for SMEs to meet safety standards. Through preliminary inspection, emergency management authorities have systematically grasped the problems prevalent in the safety management of SMEs and sensed the urgent need of SMEs for safety services. To improve the level of safe production in SMEs and solve the problems of safe supervision in SMEs, the Pukou District Emergency Management Bureau has made a targeted effort to unite and integrate the safety management of SMEs through the formation of the Safety Mutual Assistance Union and the Safety Service Union.

5.1. Interactive Process Between Units

Typically, the interaction between safety service providers and SMEs and between plant lessors and lessees is based on a weak correlation of business value and contractual interests, whereas the interaction between safety regulators and SMEs is based on a strong correlation of administrative legal orders. Therefore, in the initial construction stage of the safety alliance modules, bottom–up demand traction is needed, and bottom–up institutional regulation is also needed to avoid the problem of unequal power and responsibility or an imbalance of interests. Based on this, at the inception of the unit design, safety regulatory authorities engaged in active communication with safety experts and scholars to secure professional theoretical support, coordinated the implementation of the ‘factories in factories’ model, and utilised an information exchange platform to establish a vertical regulatory unit, thereby achieving policy coherence and regulatory linkages.

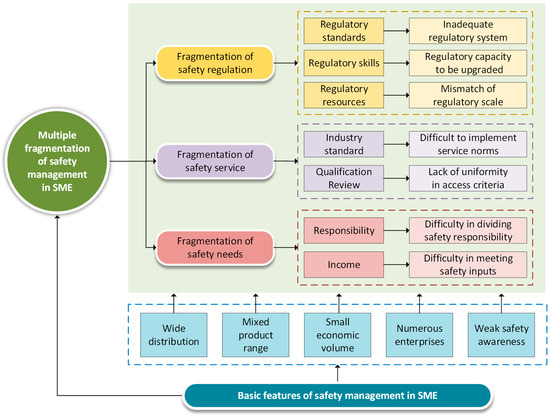

The cost is the first thing that SMEs consider when implementing safety management. The Pukou District Emergency Management Bureau, in accordance with relevant laws and policies and the principles of “geographic proximity, industry proximity, comparable size, and practicality”, organises enterprises within its jurisdiction into classified groups to form a ‘safety mutual aid alliance’. On the one hand, in line with the principles of “geographic proximity, industry proximity, comparable size, and practicality”, enterprises within the jurisdiction are classified into groups to form a ‘safety mutual aid alliance’, which coordinates safety management efforts and organises regular cross-mutual aid inspections to foster mutual learning and enhance safety awareness among SMEs. On the other hand, we have organised some safety service organisations to form the ‘Safety Service Alliance’, which has unified the specific contents and standards of safety services and lowered the charges for safety services. Enterprises joining ‘safety mutual aid alliance’ sign contracts with safety service organisations joining the ‘Safety Service Alliance’ to obtain safety services in groups and share the costs of safety services according to the actual size of the enterprise, the number of people, the degree of danger, etc., thus greatly reducing the cost of safety management for SMEs. This greatly reduces the safety management costs of micro- and small enterprises. Moreover, for demand units, the lessor of the factory-in-factory takes the lead in forming a safe mutual aid alliance with various SMEs in the factory area and directly connects with the Safety Service Alliance composed of a number of third-party safety service organisations to obtain safety services, which effectively avoids the chaos in the industry caused by the direct contact between safety service organisations and SMEs. The interactive process between units is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Interactive process between units.

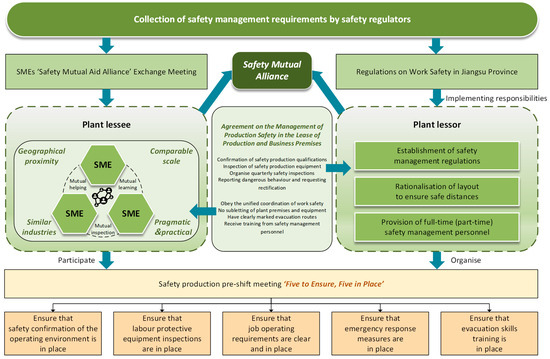

5.2. Safety Mutual Alliance Operating Model

To comprehensively assess SMEs’ safety service needs and convene exchange meetings for the ‘safety mutual aid alliance’, enterprises within the jurisdiction are grouped in accordance with the principles of “geographic proximity, industry proximity, comparable size, and practicality”. The groups will learn, help, and supervise each other to strengthen the safety management awareness of SMEs and prepare for the construction of the demand unit. Moreover, in accordance with Article 16 of the ‘Jiangsu Province Work Safety Regulations’ regarding the implementation of primary safety responsibilities and the formation of a production safety management consortium, the principal responsibility of the plant lessor is further emphasised, while bundled responsibilities are extended to small and microenterprises, thereby encouraging the eventual establishment of a safety mutual aid alliance led by the plant lessor, either under the guidance of local authorities or initiated by the SMEs themselves.

To facilitate the role of this alliance, in terms of legal regulation, the safety regulators have moderately delegated their authority to guide the two leasing parties to formulate the Agreement on the Management of Production Safety in the Leasing of Production and Business Premises. On the one hand, the lessor needs to strengthen its management work in terms of qualification access, system protocols, emergency response, etc. The lessor is required to review and record the lessee’s business qualifications, equipment and facilities, processes, etc., and to sign a special safety management agreement with the lessee’s SMEs to clarify both parties’ responsibilities for safety and to supervise whether their daily safety management work is put into place. On the other hand, the lessee SMEs are expected to enhance the safety education and training of employees—this includes having the principal in charge and safety production management personnel undergo examinations conducted by competent authorities for certification, ensuring that special equipment operators and special operators are duly licenced, and having general staff evaluated by the enterprise’s internal procedures prior to work commencement. Moreover, each enterprise is required to organise daily risk identification and hidden danger investigations, with the principal responsible for conducting at least a monthly safety inspection to identify hazards and mandate the timely rectification of any issues.

Effective self-regulation or safety management requires the support and active collaboration of staff at all levels of enterprise content, so effective safety management needs to be advanced to the height of the enterprise’s safety culture [40], which SMEs are obviously unable to achieve. Since there is no specialised safety management organisation and business operators do not have expertise in safety management, there is a general lack of awareness, knowledge, and protective skills among SME employees, who also tend to reject the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) as well as general protective measures [41]. To this end, Pukou District requires SMEs to set up a preshift handover system, with a preshift meeting of approximately 5 min at each shift handover. In enterprises operating under a continuous work system, the “preshift meeting” is convened before the commencement of each shift with the primary aim of minimising unsafe human behaviour. This meeting is structured around five critical objectives: (1) confirming the safety of the operating environment; (2) verifying that all personal protective equipment is properly inspected and in use; (3) ensuring that operational procedures are strictly followed; (4) establishing that effective emergency response measures are in place; and (5) confirming that comprehensive evacuation and escape skills training have been conducted. To promote and implement the ‘preshift meeting’ system, the Pukou District Emergency Management Bureau requires SMEs in the district to incorporate the ‘preshift meeting’ into their safety meeting system and to include the implementation of the system in their annual safety work priorities. The implementation of the system is included in the annual production safety focus of the enterprise and is one of the contents of the annual assessment of the staff. Moreover, the Emergency Management Bureau also requires all industry management departments and relevant departments with production safety supervision responsibilities to urge SMEs to strictly implement the ‘preshift meeting’ system of safety management and to include the implementation of the system in their daily law enforcement inspections and accident investigations. The safety mutual alliance operating model is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Safety mutual alliance operating model.

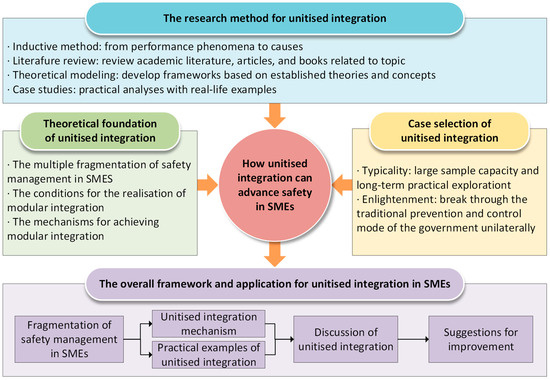

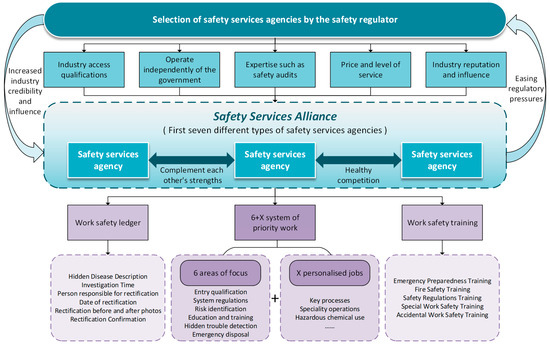

5.3. Safety Services Alliance Operating Model

To solve the chaos in the industry of safety service agencies, ensure the professionalism of safety service agencies and implement the safety management system of SMEs, in the construction stage of the supply unit, the Pukou Emergency Management Bureau selected the first seven third-party safety service agencies by considering a number of factors, including the agency’s qualifications for industry access; independence from government intervention or conflicts of interest; professional capabilities such as risk assessment, safety auditing, corporate reputation and credibility; and pricing and service, among other elements. The first seven third-party safety service providers were selected to form the Safety Service Alliance. Different third-party organisations in the Safety Service Alliance have their own advantages in providing safety services to SMEs in different categories, such as construction, wholesale, retail and catering, so that they can provide services in a targeted manner and, at the same time, learn from each other’s strengths to improve their own service level.

Most SME operators do not lack professional safety expertise and knowledge, which prevents them from effectively implementing safety management, controlling safety risks, improving safety practises, and identifying potential hazards [42], and because the cost is not staffed by full-time safety management professionals, they rather take the approach of outsourcing and delegating internal safety management tasks to third-party intermediaries. Intermediaries charge different fees, and the safety management services they provide are not exactly the same; even the management advice given by experts from different intermediaries is not exactly the same. The Pukou District Emergency Management Bureau issued a ‘service list’ and ‘service guide’ to further standardise the content of services such as onsite safety management, safety management accounts, and emergency response work and, in response to the industry chaos of third-party service providers, the service costs, service time, settlement methods, and service fees of safety service providers, putting an end to the phenomenon of indiscriminate charging by intermediary companies.

Under the guidance of safety regulators, the Safety Service Alliance has summarised the main problems and hidden dangers in the safe production of SMEs and issued the ‘Guidelines for Key Work in Site Management of SMEs’ from six key aspects, such as qualification access, systems and regulations, risk identification, education and training, hidden danger investigations, and emergency response, which are combined with key processes, special operations, and the use of hazardous chemicals, to form the ‘6 + X’ key work system, which more accurately carries out the key points of safety management of SMEs for daily safety management. These six aspects of the key content of the SMEs themselves and their production premises (land) of the lessor each focus on their own. It also helps SMEs establish production safety accounts and clarify the specifications for the investigation and rectification of hidden dangers. Regular safety training is provided to SMEs in the areas of safety emergency planning, laws and regulations, firefighting operations, and special operations. The safety services alliance operating model is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Safety services alliance operating model.

Judging from the results of implementation, the role played by unitised integration in promoting safety in SMEs is very obvious. To date, the alliance has helped SMEs that have signed the agreement to formulate and improve more than 150 safety management systems, 47 operating procedures, eight safety checklists, and 33 emergency plans and onsite disposal programmes. At the same time, on the basis of comprehensive risk identification and assessment, the Safety Service Alliance has also guided SMEs in formulating a four-colour map of the factory and a fire escape roadmap and has posted more than 100 copies of the safety management system, operating procedures and identification signs. Under the guidance and assistance of the safety service mechanism, all of the 1131 problems and hidden dangers mapped out in the previous period have been rectified and put in place. While administrative records indicate a 100% rectification rate for identified hazards (n = 1131), these figures reflect aggregated outcomes and lack independent verification. The results suggest potential efficiency gains from unitary integration, but causal attribution requires further validation through controlled studies.

6. Discussion

Although this study expands the boundaries of the application of the theory of unitisation of public services in the field of safety governance, it is the first to construct a three-stage integration model of ‘unit construction—docking—optimisation’, which provides a new theoretical perspective for explaining the mechanism of multi-party synergy. A comparison of several case studies in the Policy and Practice Report on Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) in SMEs published by the European Union Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) reveals that safety management measures in SMEs adopted in EU countries focus on the use of big data to provide online risk assessment tools (France, Denmark), requirement-driven value chains (the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden), the use of communication campaigns to raise OSH awareness and participation (Poland, Romania), and the involvement of non-OSH intermediaries (UK, Estonia) [43]. Of these, OSH training and intermediary engagement have similarities to the supply side of safety services in the SME Safety Alliance; however, the implementation of this measure has not been as effective as in the SME Safety Alliance. However, the institutional measure of the VCA certification system requiring subcontractors to be OSH-compliant, the economic measure of the Italian ISI-INAIL subsidy encouraging firms to implement OSH improvements, and the technological measure of the French utilisation of the OiRA online risk assessment tool are worthy of further learning for SME Safety Alliance.

Based on this, the SME Safety Alliance still needs to pay attention to the problems of lagging policy support, relatively weak willingness of the alliance to cooperate, the existence of a disconnect in the cooperation process, and the long-term operating mechanism. External factors such as tightened government regulations (e.g., Jiangsu Provincial Safety Committee mandates) and increased SME awareness campaigns may have synergistically influenced outcomes too.

6.1. Low Willingness to Integrate

The willingness to co-supply public services is influenced by the ability and motivation to co-supply. However, in the process of unitised integration of the Pukou District SME safety alliance, the government can provide relatively limited personnel and funds and insufficient integration capacity. As a result, the benefits received by safety service organisations are relatively low. This has, to some extent, weakened the incentive of these organisations to actively participate in co-operative supply. The low economic efficiency makes the role of safety service organisations in the alliance awkward, as they are neither able to give full play to their strengths nor receive due rewards. This results in safety organisations being less motivated to participate in the affairs of the alliance, and there may even be an unwillingness to take responsibility and shirk their responsibilities. It will be difficult to attract more SMEs and high-quality safety organisations to join, thus affecting the stability and sustainable development of the alliance. Moreover, ensuring information symmetry between the main parties of the joint supply is difficult, which limits the promotion of the safety alliance. Enterprises do not yet have a deep understanding of safety alliances, and misunderstandings and misconceptions about them still exist, so there is a gap in the degree of support and cooperation. This situation greatly reduces the motivation to join forces, which in turn affects the willingness to do so. The study acknowledges that the increase in the safety compliance rate may be affected by the government’s ‘Three-Year Special Remedial Action’ policy over the same period (2021–2023). The independent role of unit integration needs to be further verified in the future by controlling for the policy effect through the double difference method.

6.2. Obstacles to Integration

The degree of cooperation between different subjects in the process of alliance operation is poor, thus making the alliance fall short in the service process. The low level of cooperation among the alliance members is reflected in the following aspects: insufficient information sharing among the alliance members, the existence of information barriers among the members of the SME Safety Service Alliance, insufficient information sharing among the members, and the difficulty in forming an effective safety information sharing mechanism; insufficient resource sharing, the existence of resource fragmentation among the members and the conservative attitude in resource sharing, and the difficulty in forming an effective resource sharing mechanism; and the fact that SME service organisations, micro- and small enterprises, safety experts, and other multiple subjects participate in the production and provision of services together; however, the degree of cooperation among different subjects is not good, which makes the alliance fall short in the service process. Insufficient resource sharing and members have the problem of resource dispersion and show a conservative attitude in resource sharing make it difficult to form an effective safety mutual assistance mechanism; furthermore, owing to the existence of competition between SMEs, the degree of cooperation between members is not high, making it difficult to form an effective safety mutual assistance mechanism.

6.3. Policy Support Is Lagging Behind

Compared with ‘SME Safety Partnership Programme’ enacted by Germany in 2018, the modular integration model in this study is more flexible in terms of cost-sharing mechanisms, but there are gaps in terms of legal safeguards: for example, the German Act on the Promotion of Safety in SMEs explicitly stipulates the qualification criteria for third-party service providers. The policy design of the policy in question is also very important. Most of the early research on co-provision focused on the institutional and policy design of how to facilitate co-provision between government agencies and users. In view of these scholars, the existence of a meaningful policy design affects co-provisioning at the macro level [44,45]. The government’s policy support to facilitate the creation of alliances has been insufficient to meet the actual needs of alliance members. There are still many problems in the implementation, refinement, and promotion of policies. This has led to the problem of unclear safety responsibilities among members of the SME safety alliance, so it is difficult to effectively implement safety responsibilities among members.

6.4. Long-Term Operating Mechanism

With the depth of the study, we found that the SME Safety Alliance, through the long-term intervention of safety service organisations, has a significant effect on improving the safety management capacity of SMEs and fostering safety awareness. However, some SMEs do not understand the long-term nature of safety management and believe that they can improve their safety management through a single safety service, and then safety risks will appear after stopping the safety service, leading to the emergence of a repetitive rather than continuous progression of safety education and training. Safety service organisations need to gradually return the initiative of safety management to SMEs, but after SMEs have developed an awareness of safety management and complete safety management capabilities. At present, SMEs have the right to choose whether to terminate the safety services of the SME Safety Alliance. How to ensure the completion of a complete cycle of safety services and whether there are relevant regulations for this cycle are issues that need to be seriously considered for the long-term development of the SME Safety Alliance.

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Findings

This study addresses the following question: How can a unit integration model be constructed and applied to effectively integrate multiple stakeholders in the safety management of SMEs to overcome fragmented practises and enhance overall safety performance? To answer this question, field research was conducted on the safety management capabilities of SMEs, the oversight practises of safety regulatory bodies, and the service provision of safety organisations. Based on these findings, this study expands the application of unitised governance theory to safety governance and proposes a novel ‘unit construction-docking-optimisation’ framework, offering a new lens for multi-stakeholder collaboration in fragmented environments.

The findings indicate that SMEs generally exhibit weak safety awareness and limited safety management capabilities. Given these challenges, safety regulators should transition from traditional supervision to guidance-based approaches that encourage proactive safety practises. Establishing SME safety alliances through unit integration can help consolidate the fragmented landscape between SMEs and safety service organisations, better align the supply and demand for safety services, reduce management costs, and increase safety awareness. While these initial results suggest that the unit integration model has potential benefits in mitigating fragmentation, the study does not conclusively establish causality. Consequently, further research is needed to validate the model’s effectiveness across various contexts and over the long term.

7.2. Policy Recommendations

On the basis of the limitations of the unitised integration model, this study proposes some policy recommendations to optimise the unitary model of safety management for SMEs in terms of laws and regulations, the economic system and scientific and technological talent.

In terms of laws and regulations, the government, as the coordinator of safety management, should accelerate the integration of the modular integration model of safety management into the construction of the modern system of emergency management, provide adequate legal support for the development of the SME safety alliance, and promote the realisation of the cooperation and development model in which the emergency management department coordinates the development of the alliance, the safety service agencies supply it, and the SMEs receive it. The legislation of the SME safety management alliance should fully reflect the balance of the value of the interests of each subject. It should focus on strict legislation on the object and procedural elements in the process of implementing the provision of safety services, the qualification examination of the main body of service provision, the qualification management of practitioners, and the implementation of the main body’s responsibility.

With respect to the economic system, a special fund for safety management should be established, which should be allocated and earmarked annually. Tax incentives should be fully utilised, and positive signals should be sent to safety organisations through tax incentives. Make good use of the market mechanism to encourage and guide more safety service organisations with the necessary conditions to join the construction of the Safety Service Alliance through policies to stimulate the vitality of the development of the alliance to the maximum extent. Moreover, members should be rewarded for their contribution to the overall effectiveness of the alliance to motivate them to contribute to the overall development of the alliance. The design of the reward and punishment mechanism should focus on diversity to meet the needs of different members. AiFord (2002) reported that when a public service project is more complex, the greater the number of agents/people involved and the greater the proportion of the collective value created in the project are, the greater the importance of nonmaterial incentives to the ‘Citizenship Cooperation Supply’ [46]. Therefore, in addition to material incentives, nonmaterial incentives such as honours and recognition can also be considered.

With respect to science, technology, and talent, the government should first consider the three aspects of pay incentives and promotion policies for full-time safety personnel in SMEs, the cultivation of talent and the construction of disciplines within universities, and two-way cooperation between universities and the community as important means of promoting the effective functioning of the mechanism for managing talent safely in SMEs. Second, an efficient communication platform for information exchange, which may include online and offline meetings, seminars, forums, etc., should be established so that members can share experiences, discuss problems, and exchange views on these occasions. Moreover, information symmetry should be ensured, the accuracy of information transmission should be increased, and a clear process for releasing and receiving information to ensure the authenticity, accuracy, and timeliness of information should be established.

7.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has a certain degree of sophistication, analyses the fragmentation of safety management in SMEs, innovatively proposes a theoretical model for the unitised integration of safety management in SMEs, and applies practical cases to validate and analyse the model to optimise the model and propose relevant policy recommendations. However, this study lacks relevant data research because it involves confidential information such as enterprise revenue data and government planning programmes, and it also investigated a certain range of SMEs, so it has the following limitations.

First, this study adopts a unitised integration approach to promote the optimisation of safety management in SMEs. However, the motivation of unitised integration comes more from external pressure, and the analysis of the willingness of SMEs and safety service organisations to integrate themselves is not in place, which implies that there may be more complex motivations for the participation and interaction of SMEs and safety service organisations. Therefore, in the future, theories such as the joint supply theory can be further explored.

Second, the research has limitations. This study is limited by the geographical nature of the single case, and the findings only reflect the effectiveness of the practice in the specific policy environment of Pukou District in China. Due to the significant differences in the level of economic development, industrial structure, and policy implementation in different regions of China (e.g., the Yangtze River Delta versus the central and western regions), the generalisability of the study’s conclusions to SME safety management practises in other regions needs to be treated with caution. Future comparative studies with multiple cases be conducted to further validate the adaptability of the unit integration model in different institutional environments.

Third, owing to political and economic constraints, access to specific data on safety management costs and transactions within the safety alliance was limited. As a result, the precise economic impact of the unit integration model could not be quantified.

In summary, while the study observed a 100% hazard rectification rate (n = 1131) post-integration, suggesting potential efficiency gains, causality remains unproven due to data constraints. Further comprehensive research is needed to confirm the model’s long-term effectiveness and broader applicability. Future directions include: (1) comparative studies testing the model in diverse regions (e.g., central vs. coastal China); (2) longitudinal tracking of compliance rates over 5–10 years; (3) technological integration with IoT for real-time monitoring; (4) cost–benefit analyses to quantify scalability in SMEs of varying sizes. Additionally, the study may overstate the causal role of unitised integration. For instance, concurrent policies such as Jiangsu’s ‘Three-Year Remedial Action’ could synergistically drive compliance improvements. Future studies should employ quasi-experimental designs to isolate the model’s independent impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and J.W.; funding acquisition: Z.W. and J.W.; investigation: Z.W. and J.W.; methodology: Z.W. and L.K.; project administration: Z.W.; resources: J.W.; supervision: J.W. and L.K.; visualisation: Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation: Z.W.; writing—review and editing: Z.W. and L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Innovative Training Programme for University Students in Jiangsu Province, Grant No. 202410319004Z.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Heikkilä, A.-M.; Malmén, Y.; Nissilä, M.; Kortelainen, H. Challenges in risk management in multi-company industrial parks. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Research and analysis on the status quo of safety management in small and medium-sized private enterprises: A case study of Zhejiang. Enterp. Vitality 2008, 3, 90–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lanzano, U. Implementing Regulatory Policy: A Study of Frontline Inspectors and SMEs. Anglia Ruskin Research Online (ARRO). 2024. Available online: https://arro.anglia.ac.uk/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Sun, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, C.; Huang, M. An analysis of the safety butler service model. Safety 2020, 41, 71–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Joas, R.; Abel, J.; Marques, T.; Suikkanen, J. Process safety challenges for SMEs in China. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2013, 26, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohannak, K. Challenges of knowledge integration in small and medium enterprises. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. 2014, 6, 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Caldarescu, G.; Tanasievici, G.D.; Bejinariu, C.; Bernevig, M.-A. The influence of economic factors in the management of health and safety specific to SMEs. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 342, 01019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboyega, A.A.; Eze, C.E.; Sofolahan, O. Health and safety (HS) risks normalization in the construction industry: The SMEs perspective. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2021, 12, 1466–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugolli, M. Occupational, health and safety situation at small and medium enterprises in Kosovo, contextual factors, barriers, drivers and intervention process. Int. Rev. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 12, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.B.; Proverbs, D.G.; Xiao, H. The motivation of operatives in small construction firms towards health and safety–A conceptual framework. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, I.H.T.; Mat Zin, S.; Che Mat, R.; Wan Alias, W. Role of Health and Safety Management Practices in Safety Performance of Malaysian Bumiputera SMEs. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravariti, F.; Oruh, E.S.; Dibia, C.; Tasoulis, K.; Scullion, H.; Mamman, A. Weathering the storm: Talent management in internationally oriented Greek small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2021, 8, 444–463. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, N.; Suresh, M. The contribution of organizational learning and green human resource management practices to the circular economy: A relational analysis–evidence from manufacturing SMEs (part II). Learn. Organ. 2022, 29, 443–462. [Google Scholar]

- Gnan, L.; Flamini, G. Designing and Implementing HR Management Systems in Family Businesses; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, R.A.; Suhaimi, M.S.; Mat, H.C.; Dimitrova, A.; Ab Rahman, M.W. Safety Management Practices and Safety Behaviour among Outdoor Participants. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 2021, 6, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Han, S.-J.; Lee, D.-H. The Effectiveness Validation of Psychosocial Risk Management Plans in an Organizational Working Environment Using Logistic Regression Analysis. J. Korean Soc. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2021, 44, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pedi, R.; Sarri, K. Resilience Through Entrepreneurship: Enriching European External Action Service’s Resilience Toolbox. In Entrepreneurship, Institutional Framework and Support Mechanisms in the EU; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch, N. Compliance Violation in German Family Businesses: Frequency, Detection, Counter Measure Relevance. In Corporate Governance: A Search for Emerging Trends in the Pandemic Times; Hundal, S., Kostyuk, A., Govorun, D., Eds.; Virtus Interpress: Berlin, Germany, 2021; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, G.; Margherita, A.; Passiante, G. Management Engineering: A New Perspective on the Integration of Engineering and Management Knowledge. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 68, 881–893. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Johnson, L.; Davis, K. The Impact of Unit-Based Curriculum Design on Student Problem Solving Skills. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 3, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Li, D.; Huang, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Ni, X. Constructing Safety Management Systems in Modern Industry and Trade Enterprises: A STAMP-Based Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z. Unitary emergency management: A new mechanism for coordination of sectoral conflicts in public safety governance. China Emerg. Manag. Sci. 2022, 11, 28–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Brown, S. Unitized Management in Urban Planning: Optimizing Spatial Layout and Sustainability. Urban Stud. Q. 2021, 2, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.; Liu, P.; Zhou, L.; Feng, R. Research on Integration of Safety Policy System in Petrochemical Enterprises Based on Risk Hierarchical Control and Hidden Danger Investigation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Black, T. Unitized Risk Management Framework in the Financial Sector. J. Risk Anal. 2020, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; Patel, K.; Lin, C. Emergency Management in Higher Education. Educ. Saf. Q. 2021, 3, 78–99. [Google Scholar]

- University of Louisville Risk Management Services. Centralized Risk Oversight and Financial Safeguarding in Campus Operations. University of Louisville Risk Management Reports. 2021. Available online: https://louisville.edu/riskmanagement/RM (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Williams, H.; Davis, J. Institutional Risk Assessment in Universities. High. Educ. Saf. J. 2020, 2, 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, B.; Moore, J. The Role of Nonprofits in Global Safety Management. Int. Secur. Stud. 2021, 2, 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. Best Practices in Safety Risk Management. J. Risk Manag. 2022, 2, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.; Lee, C. Public Sector Safety and Emergency Response. Gov. Saf. Rev. 2019, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. Cybersecurity Trends in Public and Private Sectors. Digit. Secur. Rev. 2023, 1, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Ma, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Third-party evaluation of the China healthcare improvement initiative from 2015 to 2020: Findings and suggestions. Chin. J. Hosp. Adm. 2021, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis, G.E.; Stamatopoulos, V.G.; Rigby, M.; Kotis, T.; Negroni, E.; Munoz, A.; Mathes, L. Web-based personal health records: The personal electronic health record (pEHR) multicentred trial. J. Telemed. Telecare 2007, 13, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.E.; Selvik, Ø.; Jordheim, O.K. Norwegian emergency towing service–past–present and future. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2020, 25, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. The Effect of Operational Control Center’s Service Quality on Airline Staff’s Job Engagement. J. Korean Soc. Aviat. Aeronaut. 2020, 28, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, K.; Trevillion, K.; Gilchrist, G. “We have to put the fire out first before we start rebuilding the house”: Practitioners’ experiences of supporting women with histories of substance use, interpersonal abuse and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Addict. Res. Theory 2020, 28, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]