Destination Competitiveness Through the Lens of Tourist Spending: A Case Study of the Canary Islands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

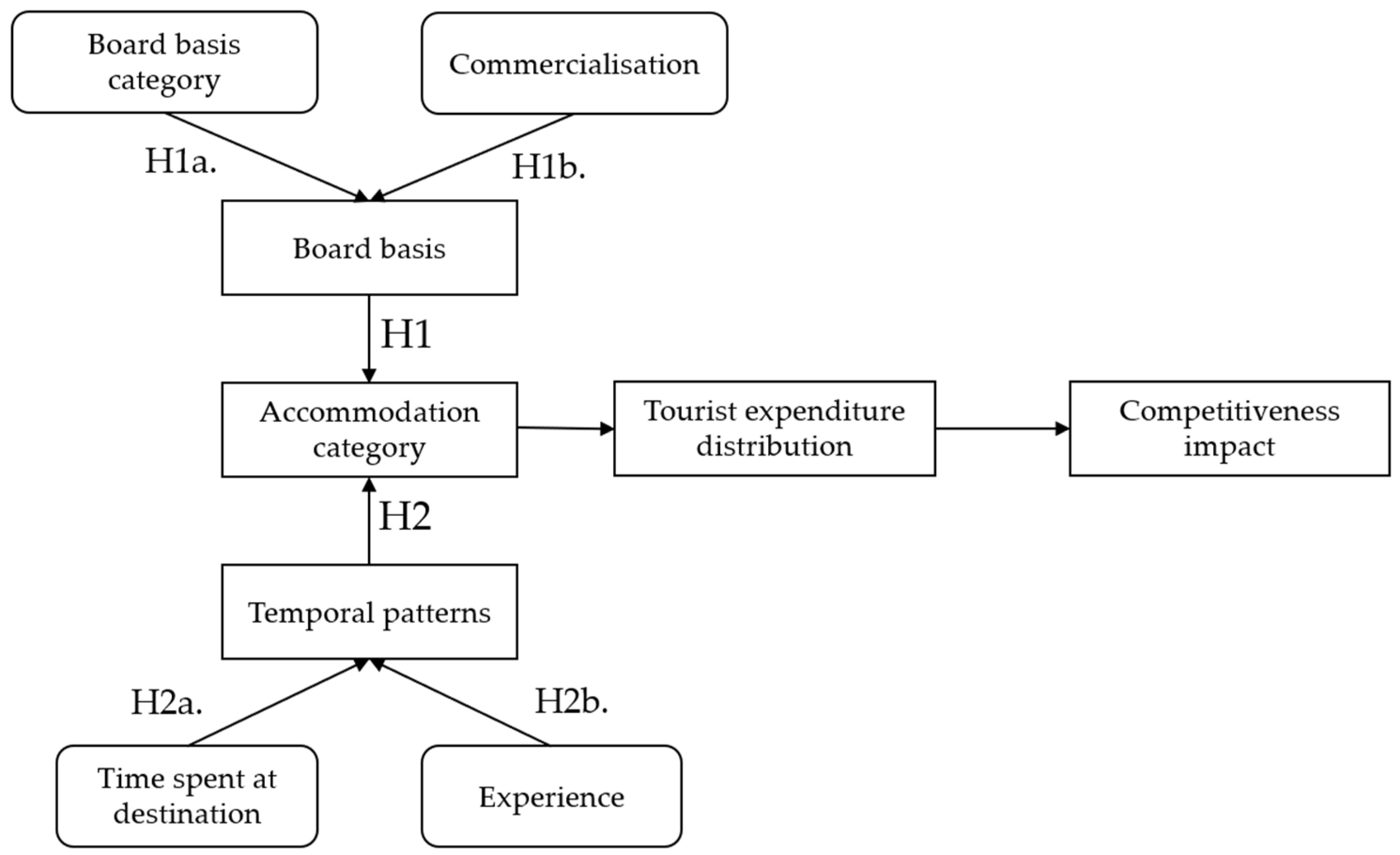

2.1. Hypotheses and Research Model

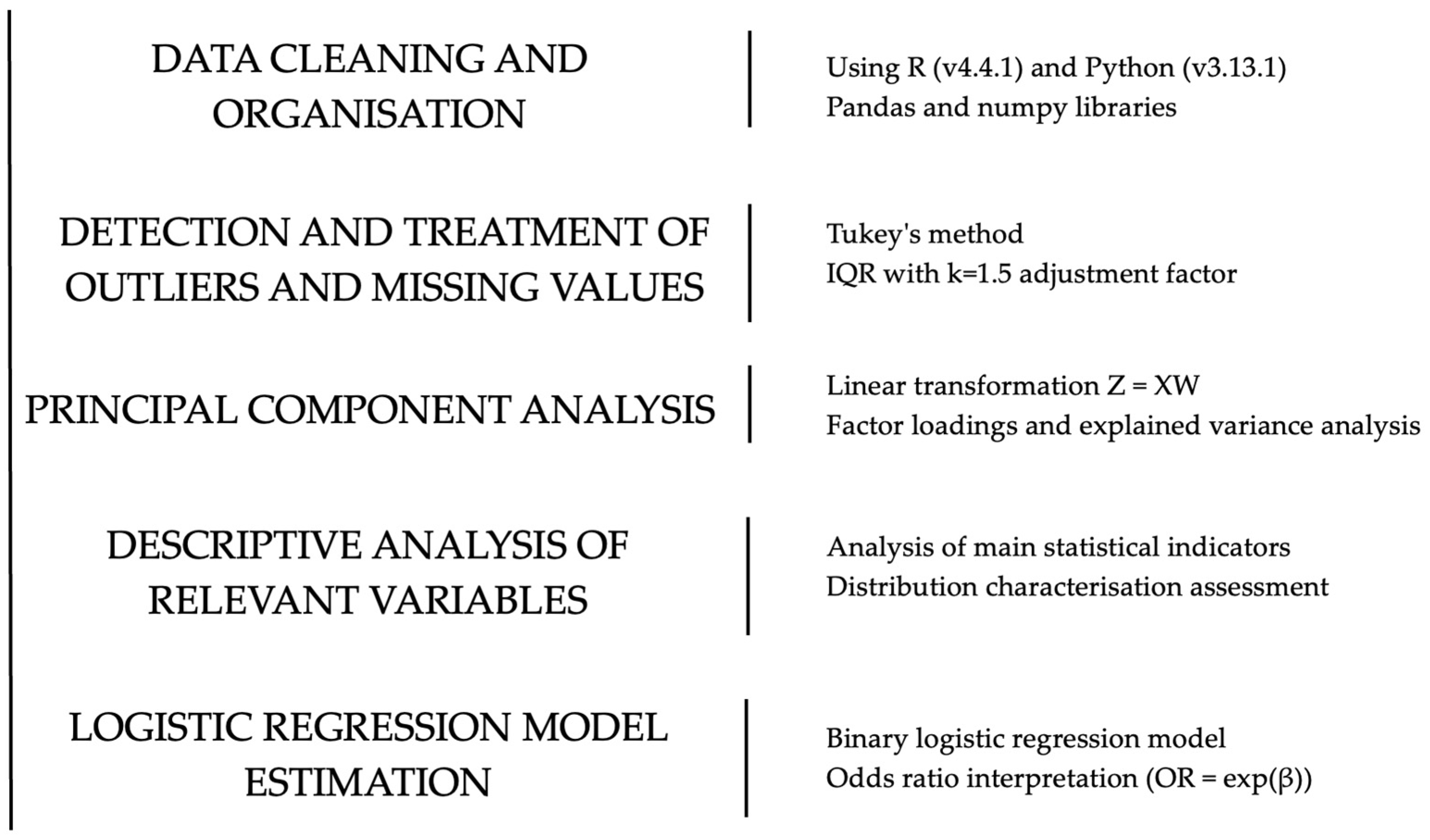

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Variable Description

3. Results

3.1. Principal Component Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

3.3. Model Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsai, H.; Song, H.; Wong, K.F. Tourism and Hotel Competitiveness Research. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 522–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.X.; Jin, M.; Shi, W. Tourism as an important impetus to promoting economic growth: A critical review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Jiménez, Y.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Hernández, J.M.; Suárez-Vega, R. The influence of remoteness and isolation in the rural accommodation rental price among Eastern and Western destinations. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, J.V.; Ledesma-Rodríguez, F. Unconditional quantile regression and tourism expenditure: The case of the Canary Islands. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 626–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo-Romero, M.d.P.; Gómez-Calero, P.; Sánchez-Rivas, J. Tourism, Competitiveness and Economic Growth: A New Analytical Model; InTech: Houston TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, E. Towards a Model to Enhance Africa’s Sustainable Tourism Competitiveness; Department of Tourism Management, University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G. Destination Competitiveness: An Analysis of Determinant Attributes. J. Travel Res. 2010, 50, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica, F.; Olimpia, B. Theoretical Framework About Tourism Destination Competitiveness; Annals of Faculty of Economics; University of Oradea, Faculty of Economics: Oradea, Romania, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. Spec. Issue El Destin. Competitivo. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, B.J.R. Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and Indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S. Determinants of Market Competitiveness in an Environmentally Sustainable Tourism Industry. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R. Measuring and Explaining Competitiveness in the Context of Small Island Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019: Travel and Tourism at a Tipping Point; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2019.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Mendola, D.; Volo, S. Building composite indicators in tourism studies: Measurements and applications in tourism destination competitiveness. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2003, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Hallak, R.; Vinzi, V.E.; O’connor, P. An Empirical Operationalization of Countries’ Destination Competitiveness Using Partial Least Squares Modeling. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Kubickova, M. From potential to ability to compete: Towards a performance-based tourism competitiveness index. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massidda, C.; Piras, R.; Seetaram, N. Analysing the drivers of itemised tourism expenditure from the UK using survey data. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Dwyer, L.; Li, G.; Cao, Z. Tourism economics research: A review and assessment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1653–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Vogt, L. Economic effects of tourism and its influencing factors. An overview focusing on the spending determinants of visitors. Z. Für Tour. 2016, 8, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disegna, M.; Osti, L. Tourists’ Expenditure Behaviour: The Influence of Satisfaction and the Dependence of Spending Categories. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divisekera, S.; Nguyen, V.K. Drivers of innovation in tourism: An econometric study. Tour. Econ. 2018, 24, 998–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.; Mendes-Filho, L.; Buhalis, D. Evaluating the effectiveness of tourist advertising to improve the competitiveness of destinations. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 1001–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Archi, Y.; Benbba, B.; Nizamatdinova, Z.; Issakov, Y.; Vargáné, G.I.; Dávid, L.D. Systematic Literature Review Analysing Smart Tourism Destinations in Context of Sustainable Development: Current Applications and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.; Isa, S.; Alqudah, M. Smart Tourism, Hospitality, and Destination: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. J. Tour. Serv. 2024, 15, 72–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasisi, T.T.; Odei, S.A.; Eluwole, K.K. Smart destination competitiveness: Underscoring its impact on economic growth. J. Tour. Futur. 2023, 9, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, S.; Brida, J.G.; Risso, W. The impacts of international tourism demand on economic growth of small economies dependent on tourism. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzel, S.; Seetanah, B.; Sannassee, R. Analysing the impact of tourism foreign direct investment on economic growth: Evidence from a small island developing state. Tour. Econ. 2016, 23, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Scuderi, R. Determinants of Tourist Expenditure: A Review of Microeconometric Models. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 6, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.-K.; Wang, F.-C. Another Look at the Determinants of Tourism Expenditure. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Davidson, M. A Review of Micro-analyses of Tourist Expenditure. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Tan, Z.; Lee, L.; Hoa, S.; Fordham, G. Corporate Social Responsibility in Sustainable Tourism Development towards Local Culture. J. Sos. Sains, Ter. Dan Ris. 2023, 11, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, W.Q.d.F.; Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C.M. Sustainability and Tourism Marketing: A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications between 1997 and 2020 Using VOSviewer Software. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M.; Goffi, G. Does sustainability enhance tourism destination competitiveness? Evidence from Italian Destinations of Excellence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Shao, C.; Chen, S.; Wei, Z. Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Tourism Cities Based on SDGs and Tourism Competitiveness Index: Analysis of 221 Prefecture-Level Cities in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte, V.; Aria, M. Coopetition and sustainable competitive advantage. The case of tourist destinations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, C.; McCabe, S. Expanding theory of tourists’ destination loyalty: The role of sensory impressions. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilplub, C.; Khang, D.B.; Krairit, D. Determinants of Destination Loyalty and the Mediating Role of Tourist Satisfaction. Tour. Anal. 2016, 21, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdana, D.S.; Frleta, D.S. Satisfaction as a determinant of tourist expenditure. Curr. Issues Tour. Taylor Fr. J. 2017, 20, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego-Domínguez, S.; Castillo, F.; Rodríguez-Fernández, M. Determinants of Tourism Demand in Spain: A European Perspective from 2000–2020. Economies 2022, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Canario de Estadística (ISTAC). Tourism Expenditure Methodology. 2018. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/descargas/C00028A/2018/EGT-2018-metodologia.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Tanana, A.; Caruso, M.J.; Rodríguez, C. Determinants of The Expenditure of Tourist Demand in Coastal Destinations. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. (AHTR) 2022, 10, 206–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W. Determinants of all-inclusive travel expenditure. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheeders, T. A review of the determinants of tourism destination competitiveness. J. Contemp. Manag. 2022, 19, 238–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Pou, L. Research Note: Tourism Expenditure and all-Inclusive Packages—The case of a Mature Mediterranean Destination. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Esposito Vinzi, V.; O’Connor, P. Modelling a Causality Network for Tourism Development: An Empirical Analysis. J. Model. Manag. 2011, 6, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Runger, G.C. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R. The Multiple Logistic Regression Model. In Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Two-Way Fixed Effects, the Two-Way Mundlak Regression, and Difference-in-Differences Estimators. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 2021, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L.; Nicolau, J.L. Choice behaviour in online hotel booking. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrocu, E.; Paci, R.; Zara, A. Micro-economic determinants of tourist expenditure: A quantile regression approach. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenedetti, A.; Philippe, D.; Dion, D. Balancing exclusivity and inclusivity through the strategic domestication of the luxury retail experience. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Issa, J.J.; Jayawardena, C. The all-inclusive concept in the Caribbean. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 15, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchausti-Sintes, F.; Voltes-Dorta, A.; Suau-Sánchez, P. The income elasticity gap and its implications for economic growth and tourism development: The Balearic vs the Canary Islands. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.; Smith, S.; Potwarka, L.; Havitz, M. Why tourists choose Airbnb: A motivation-based segmentation study. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Ye, Q.; Law, R. Effect of sharing economy on tourism industry employment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Proserpio, D.; Byers, J.W. The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Zare, S. COVID19 and Airbnb—Disrupting the Disruptor. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Cárdenas-García, P.J.; Espinosa-Pulido, J.A. Does environmental sustainability contribute to tourism growth? An analysis at the country level. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Results |

|---|---|

| Number of islands | 8 islands (GC, TF, LZ, LP, FV, LG, EH; LR) |

| Total surface area | 7447 km2 |

| Protected natural areas (PNAs) | 47.8% of the land |

| Aggregate population | 2,258,219 million inhabitants |

| Demographic density | 295 inhabitants per km2 (GC 546.96; TF 458.04; LZ 184, 53; LP 117.85; FV 72.30; LG 58.91; EH 42.46; LR 25,4) |

| Number of tourists | 17,767,834 tourists |

| Occupancy rate | 83.94% |

| Median length of stay | 7.15 days |

| Tourism revenues | EUR 22,887,000,000 |

| Gross domestic product | EUR 54,194,000,000 |

| Rate of unemployment | 11.9% |

| Populace at risk of social marginalisation | 25.8% |

| Characteristics | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2024 | |||

| Type of sampling | Tri-stage and non-probability sampling | |||

| Confidence index | 95% Sampling error < 1% | |||

| Total sample | 38.071 | |||

| Islands Tenerife Gran Canaria Lanzarote Fuerteventura La Palma | Number of tourists | Sample EGT | ||

| 2023 | 2024 | |||

| 6,449,359 | 40% | 14,007 | 37% | |

| 4,235,141 | 26% | 11,221 | 29% | |

| 3,049,188 | 19% | 6110 | 16% | |

| 2,274,859 | 14% | 5349 | 14% | |

| 148,720 | 1% | 1384 | 4% | |

| Variables Measured in the Study | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||

| Accommodation type | Type of accommodation where the tourist stayed. |

|

| Independent variables | ||

| Board basis | Specifies the type of meal and beverage services contracted. |

|

| Package holiday | Specifies whether a package holiday including both flight and accommodation was purchased. |

|

| Flight purchase | Specifies where the flight was purchased. |

|

| Number of overnight stays | Total number of nights spent in the Canary Islands. |

|

| Time spent outside accommodation | Number of hours spent outside the accommodation. |

|

| Expenditure | Total travel expenditure in euros across different categories. |

|

| Motivation | Primary motivation for the holiday. |

|

| Perceptions | Evaluation of different aspects related to sustainability during the stay in the Canary Islands. |

|

| Activities | Specifies whether the tourist engaged in the activities at right during their stay in the Canary Islands. |

|

| Travel companions | Specifies whether the tourist travelled alone or accompanied, and the type of company. |

|

| Visits | Specifies the number of visits to key sites of interest on the islands. |

|

| Information sources | Specifies the information channels used to plan the trip. |

|

| Services | Specifies whether the package holiday included transfers or excursions. |

|

| Dimension 1 | Contribution | Dimension 2 | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of visits | 0.361 | Origin expenditure | 0.242 |

| Activities | 0.226 | Package cost | 0.129 |

| Destination expenditure | 0.070 | Type of company | 0.087 |

| Motivation | 0.039 | Number of visits | 0.049 |

| Purchase channel | 0.038 | Activities | 0.022 |

| Age | 0.020 | Hours away accommodation | 0.010 |

| Hours away accommodation | 0.012 | Board type | 0.008 |

| Type of company | 0.010 | Total expenditure | 0.005 |

| Transfer service | 0.007 | Age | 0.002 |

| Type of Accommodation | 5–5GL-Star | 4-Star | 1- to 3-Star | Apartment–Village | P2P | Own Apartment | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of tourists surveyed | 3.186 | 14.608 | 4.131 | 7.026 | 4.456 | 3.039 | 36.446 |

| Number of overnights | 24.507 | 115.186 | 33.847 | 66.262 | 44.193 | 35.880 | 319.875 |

| Mean number of overnights | 7.69 | 7.88 | 8.19 | 9.43 | 9.91 | 11.80 | 9.15 |

| Median number of overnights | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Board Basis (%) | 5–5GL-Star | 4-Star | 1- to 3-Star | Apartment–Village | P2P | Own Apartment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Room only | 5 | 6 | 26 | 65 | 95 | 97 |

| Bed and breakfast | 29 | 13 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 2 |

| Half board | 33 | 26 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Full board | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| All inclusive | 28 | 50 | 37 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Type of Accommodation (%) | 5–5GL-Star | 4-Star | 1- to 3-Star | Apartment–Village | P2P | Own Apartment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flights (national and international) | 33 | 36 | 37 | 39 | 41 | 82 |

| Accommodation (main + extras) | 63 | 60 | 58 | 56 | 52 | 1 |

| Total 1. Expenditure at origin | 97 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 93 | 89 |

| Local transport (inter-island flights, taxis, car rentals, and public transport) | 0.81 | 1.38 | 1.43 | 1.08 | 1.31 | 1.92 |

| Food and supermarket | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.54 | 0.88 | 1.29 | 4.04 |

| Restaurants | 0.87 | 0.79 | 1.21 | 1.77 | 2.02 | 6.21 |

| Leisure | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 1.41 |

| Goods | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 1.63 |

| Other expenses | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.46 |

| Total 2. Expenditure at destination | 2.58 | 3.46 | 4.29 | 4.72 | 5.65 | 15.67 |

| Total expenditure | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Dependent Variable | Accommodation Category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | 5- and 5GL-Star Hotel | 4-Star Hotel | 1-, 2-, and 3-Star Hotel | Apartment–Village | P2P |

| |||||

| 1.164 *** | 4.449 *** | - | 0.196 *** | 0.412 *** |

| 6.712 *** | 11.786 *** | 0.810 * | 0.067 *** | 0.575 *** |

| 2.896 *** | 11.567 *** | 1.570 *** | 0.076 *** | - |

| 1.832 ** | 13.376 *** | 1.525 *** | 0.089 *** | 0.537 *** |

| |||||

| - | - | 1.597 *** | 1.417 *** | 0.148 *** |

| 1.952 ** | 0.518 *** | 0.381 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.094 *** |

| |||||

| 0.680 *** | 1.342 *** | 1.603 | - | 0.563 *** |

| |||||

| 5.179 *** | - | 1.253 *** | 1.346 *** | 1.440 *** |

| 7.245 *** | - | 1.074 ** | 1.177 *** | 1.451 *** |

| |||||

| 1.928 *** | - | 0.717 *** | 0.704 *** | 0.502 *** |

| - | - | - | 0.930 * | - |

| - | - | - | - | 1.352 * |

| - | - | - | 0.898 * | - |

| - | - | - | - | 1.450 *** |

| - | - | 1.079 *** | - | |

| 0.961 *** | - | 1.083 * | 1.144 *** | 2.007 *** |

| - | - | - | - | 1.985 *** |

| - | - | - | 1.061 * | - |

| 9.170 * | 1.043 * | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | 0.883 ** | - |

| |||||

| 1.832 ** | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | 2.139 *** | - | - |

| 7.678 ** | - | - | 1.194 * | - |

| 7.197 *** | - | - | - | - |

| |||||

| 1.046 *** | - | 0.954 *** | - | - |

| 9.602 ** | 1.971 *** | 1.069 *** | - | 1.214 *** |

| 1.040 ** | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | 0.904 *** |

| - | - | 0.988 ** | 1.019 * | - |

| 9.061 *** | - | - | - | - |

| 9.177 * | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | 0.939 ** | - | - |

| - | - | - | 0.967 * | - |

| |||||

| 1.080 *** | 1.043 *** | 0.939 *** | 0.914 *** | 0.899 ** |

| 1.094 *** | - | 0.964 * | 0.921 *** | - |

| 1.117 *** | - | 0.952 * | - | - |

| - | - | 0.815 * | - | - |

| - | - | 0.864 ** | - | - |

| |||||

| - | - | 0.969 * | 1.029 * | - |

| - | 0.953 *** | 1.047 *** | - | - |

| 9.363 *** | 1.058 *** | - | 0.971 * | - |

| - | 0.963 * | - | - | - |

| - | 1.033 ** | 0.962 ** | - | - |

| |||||

| - | - | - | 0.974 * | 1.033 ** |

| 9.607 ** | 1.025 ** | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - |

| - | 0.984 * | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | 0.961 * | - |

| - | ||||

| 1.002 ** | - | - | 1.090 ** | - |

| - | 0.979 * | - | - | 1.237 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barrera-Martínez, A.M.; Santana-Talavera, A.; Parra-López, E. Destination Competitiveness Through the Lens of Tourist Spending: A Case Study of the Canary Islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073262

Barrera-Martínez AM, Santana-Talavera A, Parra-López E. Destination Competitiveness Through the Lens of Tourist Spending: A Case Study of the Canary Islands. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073262

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarrera-Martínez, Ana María, Agustín Santana-Talavera, and Eduardo Parra-López. 2025. "Destination Competitiveness Through the Lens of Tourist Spending: A Case Study of the Canary Islands" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073262

APA StyleBarrera-Martínez, A. M., Santana-Talavera, A., & Parra-López, E. (2025). Destination Competitiveness Through the Lens of Tourist Spending: A Case Study of the Canary Islands. Sustainability, 17(7), 3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073262