Abstract

This study explores creative tourism strategies in community-based tourism for sustainable development, focusing on the millennium-old Ban Chiang UNESCO World Heritage site in Thailand. It aims to uncover how creative tourism strategies support community-based tourism by optimizing development through cultural preservation, heritage revitalization, and sustainable outcomes. The research investigates how creative tourism approaches foster community-based tourism and how a community achieves sustainable socio-economic growth using the Community Capitals Framework (CCF). Using a qualitative case study approach, this research employs in-depth interviews, participant and non-participant observation, and document analysis to explore the interactions between creative tourism, community-based tourism, and sustainability. The findings reveal that creative tourism strategies can promote environmental conservation, cultural preservation, economic empowerment, and social well-being in Ban Chiang. This study highlights the successful development of strategies and collaborative actions by Ban Chiang’s community enterprise network for creative tourism progression, emphasizing multilateral stakeholder collaboration in enhancing community capital. The research proposes a model for creative tourism strategy and community capital development aimed at sustainability. It provides valuable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and local communities aiming to leverage creative tourism for sustainable development. By emphasizing the synergies between creative tourism and community-based tourism, it offers practical guidance for enhancing destination management, fostering community engagement, and promoting cultural and environmental conservation. This study bridges a critical gap in the literature by demonstrating how the CCF can be implemented to create positive impacts on creative tourism in heritage destinations such as Ban Chiang, presenting novel insights into its potential as a driver for positive transformation.

1. Introduction

Creative tourism has gained significant momentum globally over recent decades, emerging as a dynamic approach within the broader framework of sustainable tourism development. Unlike traditional forms of tourism, creative tourism offers unique opportunities for local development by fostering economic growth, preserving cultural heritage, and promoting social inclusion [1]. Building upon the foundations of conventional cultural and heritage tourism, creative tourism emphasizes active participation and engagement, offering experiences that are both authentic and enriching. This evolution aligns with the objectives of organizations such as UNESCO, which promote educational exchanges, celebrate cultural diversity, and facilitate meaningful interactions across communities.

Recent studies highlight creative tourism as a natural progression from cultural tourism [1]. While cultural tourism typically focuses on the passive consumption of heritage and local culture, creative tourism immerses tourists in local authenticity through hands-on cultural activities such as arts, crafts, and traditional heritage experiences [2]. This approach fosters mutual learning and exchange between tourists and locals, contributing to the goals of sustainable tourism. Modern tourists increasingly seek participatory, skill-enhancing experiences that engage their creativity and offer personal enrichment [3]. Creative tourism involves innovative co-creation of activities and travel routes designed to extend visitor stays and deepen engagement with local culture [4]. However, despite its promise, the literature on creative tourism remains underdeveloped [5].

This paper investigates how creative tourism can support Community-Based Tourism (CBT) and how communities can use this approach as a tool for sustainable socio-economic growth, emphasizing active community engagement in planning, management, execution, and evaluation. By integrating creative tourism principles, communities can enhance their socio-economic growth and preserve cultural heritage through sustainable tourism practices [6]. Community-Based Tourism (CBT) has gained widespread acceptance, particularly in developing nations where tourism is economically significant. Implementing CBT fosters local pride and cultural sharing while generating sustainable income and preserving heritage [7]. This model, which emphasizes community ownership and participation, contrasts with conventional top-down development approaches, attracting interest from diverse stakeholders, including governmental bodies and private enterprises [8]. However, inadequate planning and lack of creativity in CBT can pose significant challenges to its sustainability. While both CBT and creative tourism aim for sustainable outcomes, CBT is a defined model emphasizing community control, whereas creative tourism is an approach that can be integrated into CBT to enhance visitor experiences and local benefits.

Ban Chiang, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Thailand since 1992, exemplifies sustainable tourism’s potential for local development. Located in Udon Thani province, Ban Chiang represents a significant stage in human cultural, social, and technological evolution in the 5th millennium BC [9]. Despite its status, Ban Chiang struggles to attract many visitors. The site sees few foreign tourists, domestic tourists, and school study trips, generating minimal revenue. This economic challenge affects the community and local entrepreneurs, as low-spending tourists do not significantly boost local business [10]. In response, Ban Chiang residents formed a tourism working group in 2004, adopting a community-based tourism (CBT) approach with a creative tourism strategy to address this issue and generate income. This study examines how Ban Chiang revitalizes its ancient charm and attracts tourists by integrating CBT and creative tourism, supported by the recent literature [11].

Despite Ban Chiang’s rich heritage and UNESCO status, research on creative tourism’s implementation and impact within its CBT framework is limited. Both creative tourism and CBT aim for sustainable tourism development. The recent literature supports the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) as a tool to assess community well-being dimensions, aligning with creative tourism’s complex interactions [12,13]. The CCF helps investigate sustainability facets, including economic growth, social responsibility, and environmental protection, to enhance community development [14]. This study addresses the gap by exploring the interaction between creative tourism and CBT in Ban Chiang, using CCF as an analytical tool.

While sustainable tourism trends are strong, empirical evidence of creative tourism’s specific contributions to sustainability is scarce. Our study bridges this gap by examining creative tourism’s role in promoting environmental conservation, cultural preservation, economic empowerment, and social well-being in Ban Chiang. We focus on how creative tourism can support CBT development and how communities can achieve sustainable socio-economic growth using the CCF framework.

Our research aims to explore how creative tourism strategies within a CBT framework can optimize tourism development, enhance cultural preservation, and promote sustainability. We hope this evidence-based study advances theoretical knowledge and practical applications in creative tourism, CBT, and sustainable development. By examining the synergies between creative tourism and CBT, this study may offer guidance to policymakers, practitioners, and communities in leveraging creative tourism for cultural heritage management and sustainable development. We will review the literature, discuss the theoretical framework, outline the methodology, and present our findings and conclusions.

2. Literature Review and Research Framework

2.1. Creative Tourism

Creative tourism originated in the mid-1990s with initiatives such as the EUROTEX project aimed at enhancing craft sales to tourists by allowing them to observe artisans’ work [15]. This type of tourism has been developed and transformed from traditional recreational tourism, expanding from cultural tourism with the sole focus on culturally oriented experiences to sustainable tourism centered on environmental conservation and community welfare. Moving away from traditional high-culture attractions, recent scholars (Jovicic, 2016 [16]; Richards, 2020 [15]) argued that many traditional tourism models lacked interactive tourist participation. Since modern tourists are seeking innovative experiences from local communities by blending cultural tourism elements, such as cultural imagery, identity, and everyday life. Therefore, creative tourism has consequently emerged to respond to the new tourists’ demand for creative experiences.

Creative tourism offers innovative and dynamic approaches that can enhance sustainable tourism development by fostering local engagement and cultural exchange. Creative tourism differs from traditional crafts or heritage tourism in that it encourages active tourist participation in cultural activities, which fosters personal growth and unique identity [15]. Initially recognized by Butler & Pearce (1993) [17], it has since evolved to emphasize active engagement, experiential learning, and cultural immersion [1,18]. This form of tourism allows tourists to engage in diverse cultural activities, promoting mutual learning and contributing to sustainable tourism [1,15]. It reflects modern tourists’ desire for authentic experiences and supports economic growth, cultural preservation, and social inclusion [19]. Aligned with UNESCO’s mission for cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue, creative tourism offers unique opportunities for authentic engagement with culture [2,11].

While some authors view sustainable tourism development as a static concept, others argue that it is inherently dynamic and adaptable to changing conditions. Richards (2020) [15], a leading scholar on creative tourism, outlines key principles for developing creative tourism. First, understanding the destination involves recognizing its unique cultural heritage, traditions, local knowledge, and natural features. Second, leveraging local capacity should combine diverse local skills and creativity with external inputs to enrich tourism offerings. Third, creative tourism should build upon existing local assets and resources without creating any new infrastructure. Fourth, the focus should be on providing authentic and high-quality experiences rather than following passing trends.

Finally, creativity should serve as a catalyst for positive community development, harnessing ideas from the tourists and locals to drive innovation and enhance the destination’s appeal. Moreover, Richards (2021) [20] suggests two approaches to implementing creative tourism. The first approach involves organizing activities that can directly engage tourists and encourage their creativity, aiming to attract a diverse range of visitors. The second approach integrates creative activities into the overall ambiance of the destination (e.g., art festivals or cultural events) that serve to enhance tourist interest and overall appeal.

Community-Based Tourism (CBT) focuses on local community involvement and benefits, often seen as a paradigm within tourism discourse. In contrast, creative tourism emphasizes active participation and cultural experiences, and while it shares some principles with CBT, it has not yet achieved the same level of conceptual maturity. In 2011, Thailand embarked on the development of creative tourism. The innovative, creative tourism initiatives were led by a governmental entity called the Designated Areas for Sustainable Tourism Administration (DASTA). These initiatives aimed to provide tourists with immersive rural village experiences [21]. With collaborative efforts from the locals and tourists, a crafting creative tourism toolkit was co-developed to support creative tourism in rural communities through experience design principles to empower communities in expanding tourism offerings [22]. Various local facilitators and community-based organizations worked together through assorted workshops, using methods such as appreciative inquiry, democratic, participatory learning, and community empowerment [23].

2.2. Community Capitals Framework (CCF)

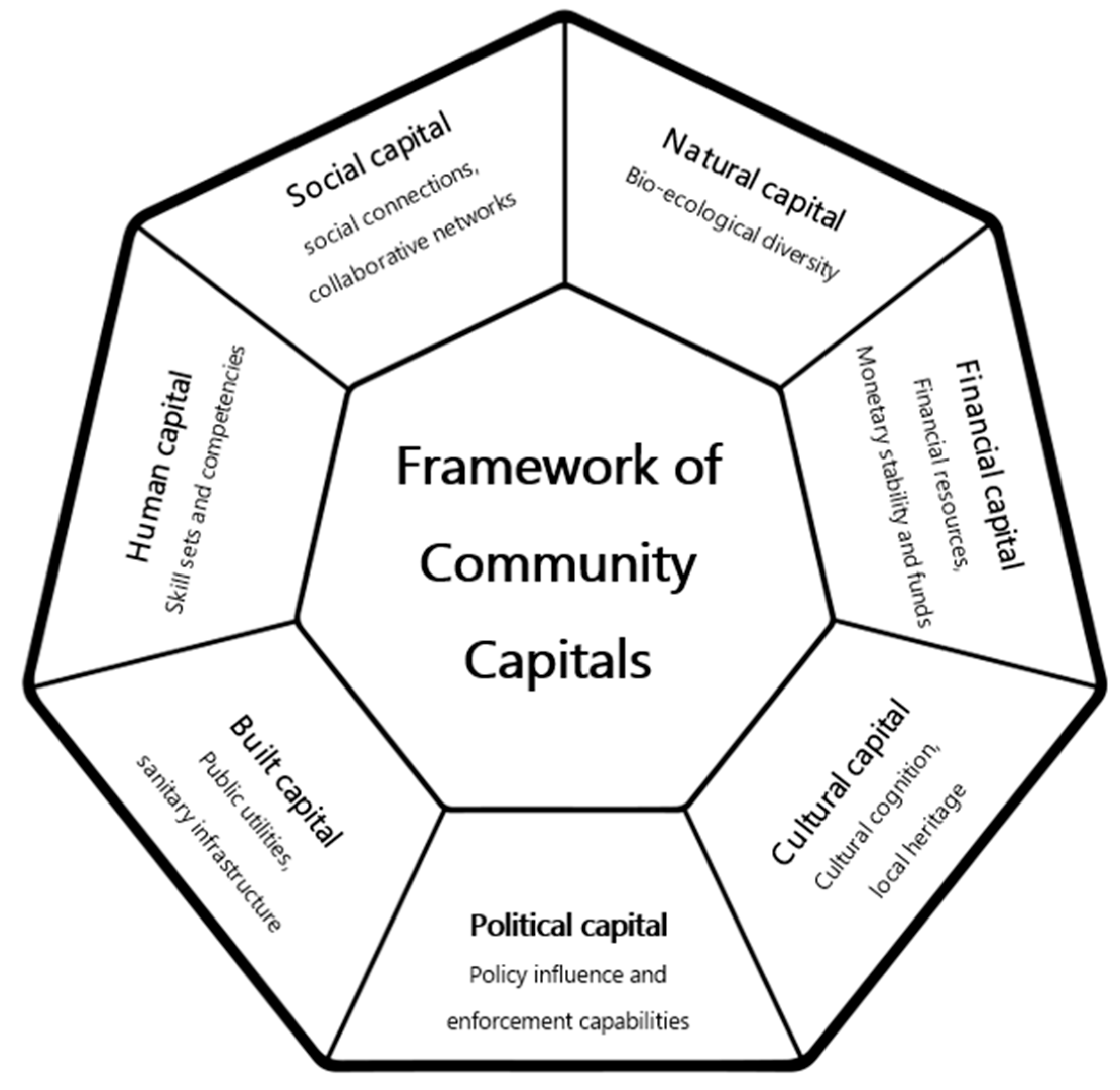

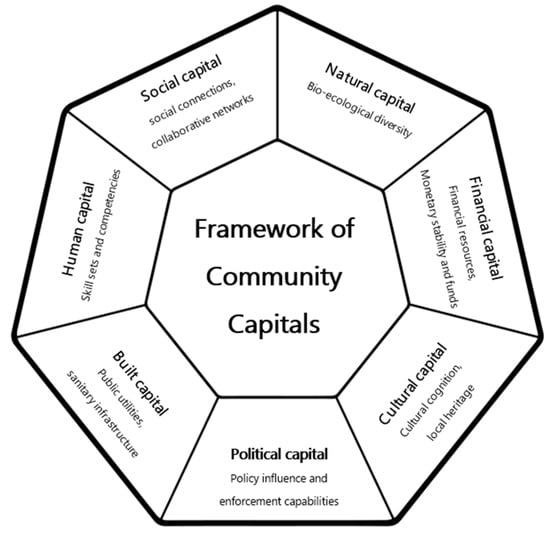

The Community Capitals Framework (CCF) examines seven key resources—natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial, and built capitals—and their interdependencies for community development [12]. When these capitals are balanced, they enhance economic growth, social cohesion, and ecosystem health. This framework is used in this research to assess sustainability (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework of community capital and its components, adapted from Emery and Flora (2020) [12].

A diagram illustrating the Community Capitals Framework. It shows seven interconnected capitals: Natural, Cultural, Human, Financial, Built, Political, and Social. Each capital is represented as a separate segment, emphasizing its interrelated nature and collective impact on community development.

Table 1 provides a summary of the descriptive details of each capital. Resources or capital may come in various forms or are parts of the process of internal community development. Essentially, capital is any resource that can be deployed to generate additional resources over the short, medium, and long term. This concept can deviate a community’s attention from the lack of resources to empower a community’s effort to focus on its existing processes instead [12]. On the bright side, it underscores the community’s need to seek opportunities to optimize or further invest in the existing resources or capital rather than scarcity. Importantly, the conceptual framework encourages communities to recognize and leverage their inherent strengths and assets, thereby fostering sustainable growth and development. By investing in their capitals, communities can not only address immediate needs but also lay the groundwork for long-term prosperity and resilience [24].

Table 1.

Seven Different Elements of Community Capitals.

Emery & Flora (2020) [12] highlight that the dynamic interaction among community capitals can either strengthen or deplete them. Balanced capitals foster sustainability, economic vitality, and social welfare, while imbalances threaten resilience. The interconnectedness means changes in one capital affect others, creating a domino effect [12]. Recent research shows that effective leadership and cultural capital can enhance other capital, creating a positive feedback loop that supports sustainable development [33]. Recognizing these interdependencies helps communities leverage their assets for effective development through CCF.

Scholars emphasize the role of community capital in tourism development. Altinay et al. (2016) [34] and Nunkoo (2017) [35] highlight social capital’s importance for reducing transaction costs and fostering investment. Garrod et al. (2006) [36] argue that successful destinations integrate physical, natural, cultural, political, financial, and human capital. Murdana et al. (2021) [37] stress that community participation depends on all these capitals.

Supported by the literature, the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) can be instrumental in assessing and advancing creative and sustainable tourism development. Therefore, this study employs CCF as the vital framework for theoretical advancement.

3. Case Study: A Community-Based Tourism Enterprise of Ban Chiang

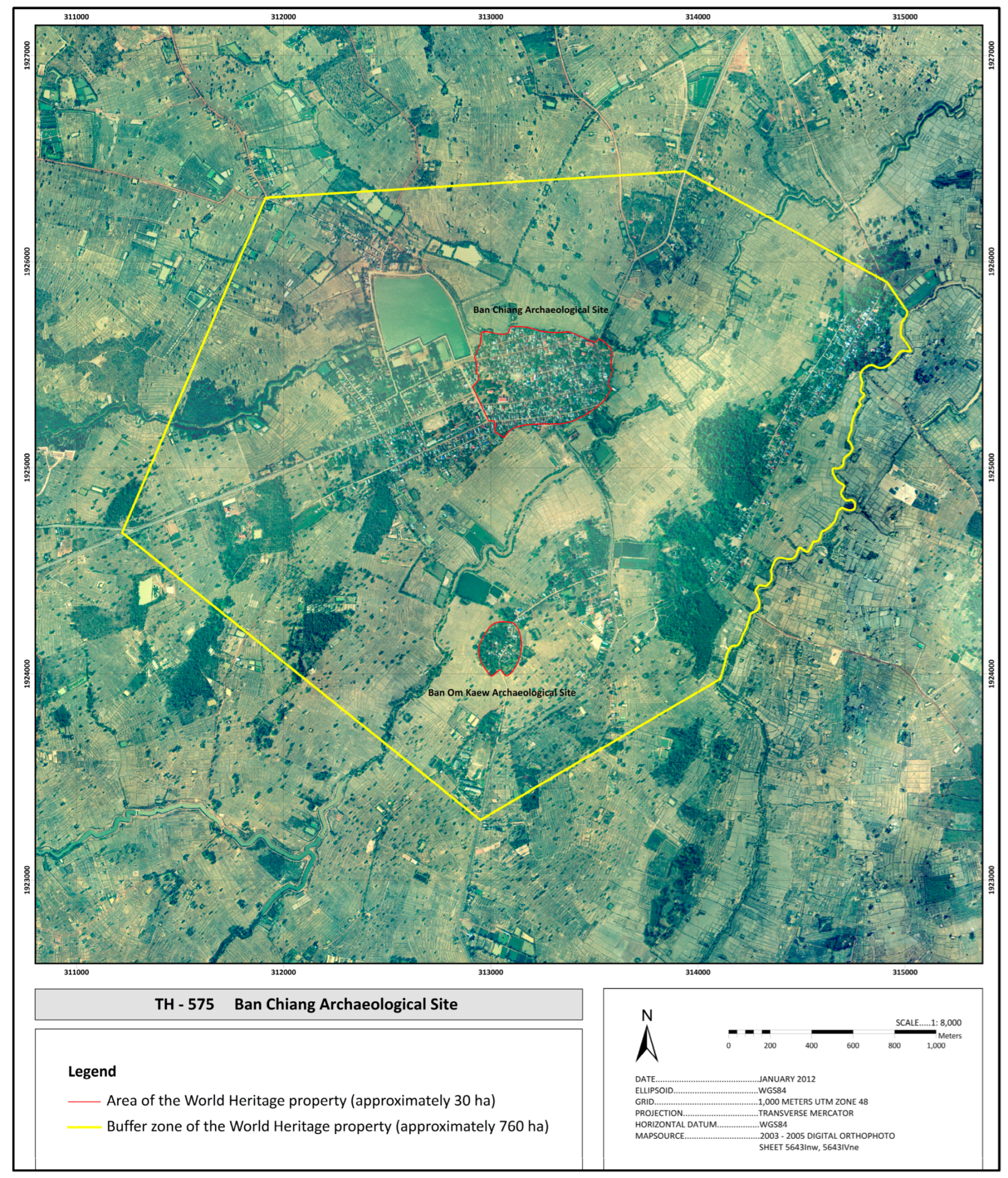

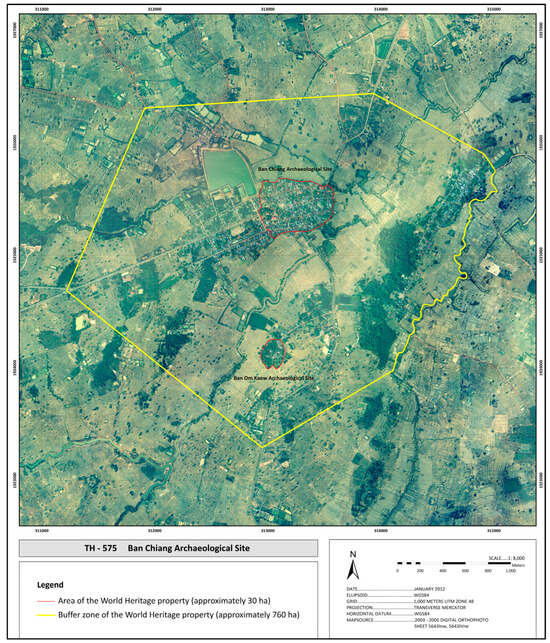

Ban Chiang, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1992, is located in Nong Han District, Udon Thani province, Thailand (see Figure 2). Recognized for its exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition and civilization, it meets UNESCO criterion iii for Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), signifying cultural significance that transcends national boundaries [38]. Historically, Ban Chiang was a center of cultural, social, and technological evolution in the 5th millennium BC, influencing Southeast Asia [39]. The site covers approximately 30 hectares, including the excavation pit, a museum, and the surrounding village, with an additional 760-hectare buffer zone (see Figure 3). Despite its vast area, only about 0.09% has been excavated from 1967 to 1992 [9].

Figure 2.

Map of Thailand highlighting Ban Chiang in Udon Thani province.

Figure 3.

A satellite image of the Ban Chiang Archaeological World Heritage Site.

A map of Thailand with Ban Chiang highlighted in Udon Thani province. The map outlines the country’s geographical boundaries, with a specific marker indicating Ban Chiang’s location in northeastern Thailand. The province of Udon Thani is distinguished to provide context within the national framework.

A satellite image of the Ban Chiang Archaeological World Heritage Site, showing its designated area and buffer zone. The red line outlines the boundary of the World Heritage property, while the yellow line represents the buffer zone.

Archaeological excavations at Ban Chiang began in 1966, led by Thailand’s Fine Arts Department and the University of Pennsylvania. Discoveries included pottery and human remains dating to around 1500 BC, marking one of Southeast Asia’s earliest civilizations. In 1972, King Rama 9 and Queen Sirikit’s visit to Ban Chiang spurred national heritage conservation and anti-looting efforts. This visit led to the 189th Revolutionary Decree in July 1972, mandating object registration to prevent artifact looting [40]. Further excavations in 1974–1975 were conducted by the Fine Arts Department and the University of Pennsylvania under Chester Gorman and Pisit Charoenwongsa.

For over 220 years, the Ban Chiang World Heritage Site has been home to the Tai Puan ethnic group, who migrated from Laos and settled in the area. The entire population of Ban Chiang consists almost entirely of Tai Puan people, who have lived in this region for several centuries. Over the years, they have developed a strong sense of community and maintained close ties with other northeastern ethnic groups in nearby villages, sharing similar cultural practices, traditions, and values. As a result, there have been no conflicts or tensions between the Tai Puan community and the tourism groups using the site.

Moreover, the community-established enterprise is deeply rooted in the collective efforts of the Tai Puan people, with the primary goal of preserving their cultural heritage. This enterprise serves as a platform for safeguarding their traditions while also engaging in tourism development, ensuring that their cultural identity is maintained and respected. Given the strong cultural ties within the community, the relationship between the Tai Puan people and the tourism sector has been largely harmonious, with the community actively participating in tourism development that aligns with their values and traditions. The Ban Chiang heritage site includes the excavation pit, museum, and surrounding village, with a buffer zone of farmlands and additional archaeological sites critical for preserving its UNESCO designation. Key landmarks are the Ban Chiang National Museum (see Figure 4), the open-air archaeological pit at Wat Pho Sri Nai (see Figure 5), and the Tai Puan House, which won the Architectural Conservation ASA Award in 2007. These sites and the buffer zone also provide economic benefits to local residents, fostering their commitment to preservation.

Figure 4.

Ban Chiang National Museum.

Figure 5.

The Archaeological Pit at Wat Pho Sri Nai.

Ban Chiang National Museum: The upper image displays the exterior of the museum building, featuring the UNESCO World Heritage emblem. The lower image highlights prehistoric pottery discovered during archaeological excavations.

The Archaeological Pit at Wat Pho Sri Nai functions as an open-air museum, showcasing excavated artifacts such as pottery and tools. These discoveries provide valuable insights into early civilizations, their daily life, and cultural practices.

Ban Chiang, a key community tourism attraction, is home to around 1500 residents within the World Heritage site and 5869 in the sub-district [41]. Local residents have created the Ban Chiang model of Community enterprise to boost socio-economic development. The community tourism group has received notable awards, including the Thailand Tourism Award in 2013 and the Outstanding Creative Tourism Village Award in 2020. Despite its UNESCO status, Ban Chiang Archaeological Site struggles to attract high-net-worth visitors, with most tourists being domestic or school groups. Tourism benefits are concentrated near the national museum, leaving distant local businesses facing economic challenges, especially in the low season. This income disparity and lack of major attractions in Udon Thani province limit international appeal and slow community economic growth.

The Ban Chiang Cultural Heritage Tourism Route map highlights visits to historical landmarks, temples, and museums. The site marked as number 3, enclosed in a star frame, represents the Ban Chiang National Museum, while number 8 designates the Archaeological Pit at Wat Pho Sri Nai.

To address Ban Chiang’s limited appeal and socio-economic challenges, various initiatives have been developed to revitalize its cultural heritage and tourist attractions. Since 2004, these efforts have been supported by DASTA and academic institutions such as Rajabhat Udon Thani University and Rajabhat Suan Sunanta University. The initiatives aim to promote the unique Tai Puan heritage and showcase local handicrafts such as earthenware, pottery, woven fabrics, and hand-dyed clothing. The goals are to enhance Ban Chiang’s archaeological significance, regenerate its cultural heritage, and revive its historical charms to attract more tourists (see Figure 6). These efforts are demonstrated through five key vocational groups:

Figure 6.

The Ban Chiang Cultural Heritage Tourism Route map.

- Pottery Group:

Visitors engage in hands-on pottery workshops, from clay gathering to crafting unique pieces. Participants can paint pottery with traditional patterns or design their motifs, inspiring new product ideas.

- Indigo-dyed Cloth Weaving Group:

Specializing in “Kram” (indigo) dyed fabrics, this group weaves designs inspired by Ban Chiang’s pottery. Visitors learn dyeing techniques and weave scarves, gaining insights into the craft.

- Wicker Works Group:

This group produces traditional crafts such as sticky rice baskets, fish traps, and baby hammocks, showcasing Tai Puan art. Visitors can learn weaving techniques and co-create patterns, helping preserve and evolve the craft.

- Homestay Group:

Award-winning homestays offer an immersive cultural experience, sharing local heritage through cuisine, shared meals, and engaging conversations.

- Food and Folk Dance Group:

Visitors enjoy Tai-Puan cuisine and traditional dance performances featuring vibrant movements and music that reflect the community’s rich history and traditions.

4. Research Methodology

This evidence-based study utilized a qualitative case study approach. We employed the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) to investigate critical success factors of management and revitalization mechanisms of the cultural heritage site and its creative tourism business model based on a multi-stakeholder perspective within an interpretive paradigm [42]. In the literature, CCF has been recognized and utilized as an analytical framework by previous studies [43]. Our study also focused on uncovering sustainable tourism business practices within Ban Chiang’s creative community-based group, adhering to international ethical standards with approval from the Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (MUCIRB).

Multiple data collection methods, particularly in-depth interviews, focus groups, and participant and non-participant observations, with a multi-stakeholder approach, were used to comprehensively examine the challenges and opportunities for creative tourism development through the revitalized cultural heritage and regenerative sustainable tourism at prehistorical sites. The in-depth interviews offered the researchers the advantages of exploring specific subjects and gaining insights into individuals’ personal thoughts, attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors in a secure environment [44]. The focus groups allowed the researchers to see group interactions and understand their collective viewpoints [45], specifically about the creative tourism and collaborative networks of the community enterprise. The participative and non-participative observations were conducted at different sightseeing and tourism attractions to broaden our contextual understanding [46]. Observations focused on community interactions, tourist engagement, and the application of traditional knowledge in tourism activities. Field notes were systematically analyzed alongside interview transcripts to identify patterns and discrepancies between stated perceptions and actual practices. Our data were derived from diverse stakeholders, including key community leaders, heads of tourism groups and their members, local residents, business entrepreneurs, visiting tourists, and judges from the Thailand Rural Tourism Award 2020.

A total of 30 voluntary participants from the tourism community took part in this study. Among them, five were external stakeholders, including representatives from key organizations such as the Designated Areas for Sustainable Tourism Administration (DASTA), the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT), and academic institutions. These informants were selected based on their expertise and roles in the tourism development processes across all three study sites.

Three group interviews were conducted with different participant groups to ensure diverse representation. The first group consisted of five community enterprise members from various occupational backgrounds, the second group included non-enterprise members from Ban Chiang, and the third group comprised students from Udon Thani Rajabhat University, who visited Ban Chiang as tourists and participated in a pottery workshop. Participants were selected based on their involvement with or knowledge of the tourism community, with invitations extended to a variety of groups, including community enterprise members, non-enterprise members, and students engaged in tourism activities. Certain groups, however, such as those less involved in tourism-related activities, were not included due to logistical constraints. The profiles of all participants are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Profile of Key Informants for Ban Chiang.

For data analysis, we used thematic analysis [47] to structure data, identify common themes, and connect findings to broader theoretical concepts. This method helped integrate data-driven and theory-driven codes, enabling the assessment of how the Ban Chiang Community enterprise revitalizes its heritage through the Community Capitals Framework (CCF). Data triangulation [48] ensured validity and reliability. Overall, the analysis provided insights into creative and sustainable tourism at the UNESCO site.

5. Findings

The findings reveal how creative tourism can support Community-Based Tourism (CBT) development and achieve sustainable socio-economic growth at Ban Chiang, a millennium-old UNESCO heritage site. This study identifies key success factors and mechanisms for Ban Chiang’s creative tourism, highlighting its cooperative network of community enterprises and regenerative cultural heritage management using the Community Capitals Framework (CCF). These results demonstrate how integrating creative tourism strategies within a CBT framework can optimize tourism development, enhance cultural preservation, and promote sustainability.

5.1. Analytical Results Using Community Capitals Framework (CCF)

Using the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) for analysis, our results revealed that Ban Chiang’s CBT enterprise network revitalizes and regenerates its creative tourism development and strategies across the seven types of community capitals. These capitals strongly contributed to its CBT success and socio-economic growth at the prehistorical site. Our detailed resultant evaluation is discussed in sequence.

5.1.1. Natural Capital

The assessment of Ban Chiang’s community-based tourism enterprise revealed a significant reliance on natural capital. Its natural conservation is a part of life in the community. The locals and its stakeholders highlight the pristine beauty of its surrounding environment, which highlights its allure to tourists.

“Besides Ban Chiang Museum, our lush landscapes and untouched natural sites attract tourists seeking tranquility and a connection with nature.”—A tourism community enterprise member(BC-6)

Moreover, our interviews’ results underscored the importance of preserving natural resources for future generations.

“Our enterprise is dedicated to implementing sustainable practices that safeguard and conserve our natural environment. Through initiatives like the 3 R: Reduce-Reuse-Recycle waste reduction campaign, we actively minimize our ecological footprint and contribute to the preservation of our surroundings.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

“Conserving our community forest, rice field, and water pond is not just essential for tourism; it’s a duty we owe to our children and grandchildren.”—A tourism community enterprise member(BC-8)

5.1.2. Cultural Capital

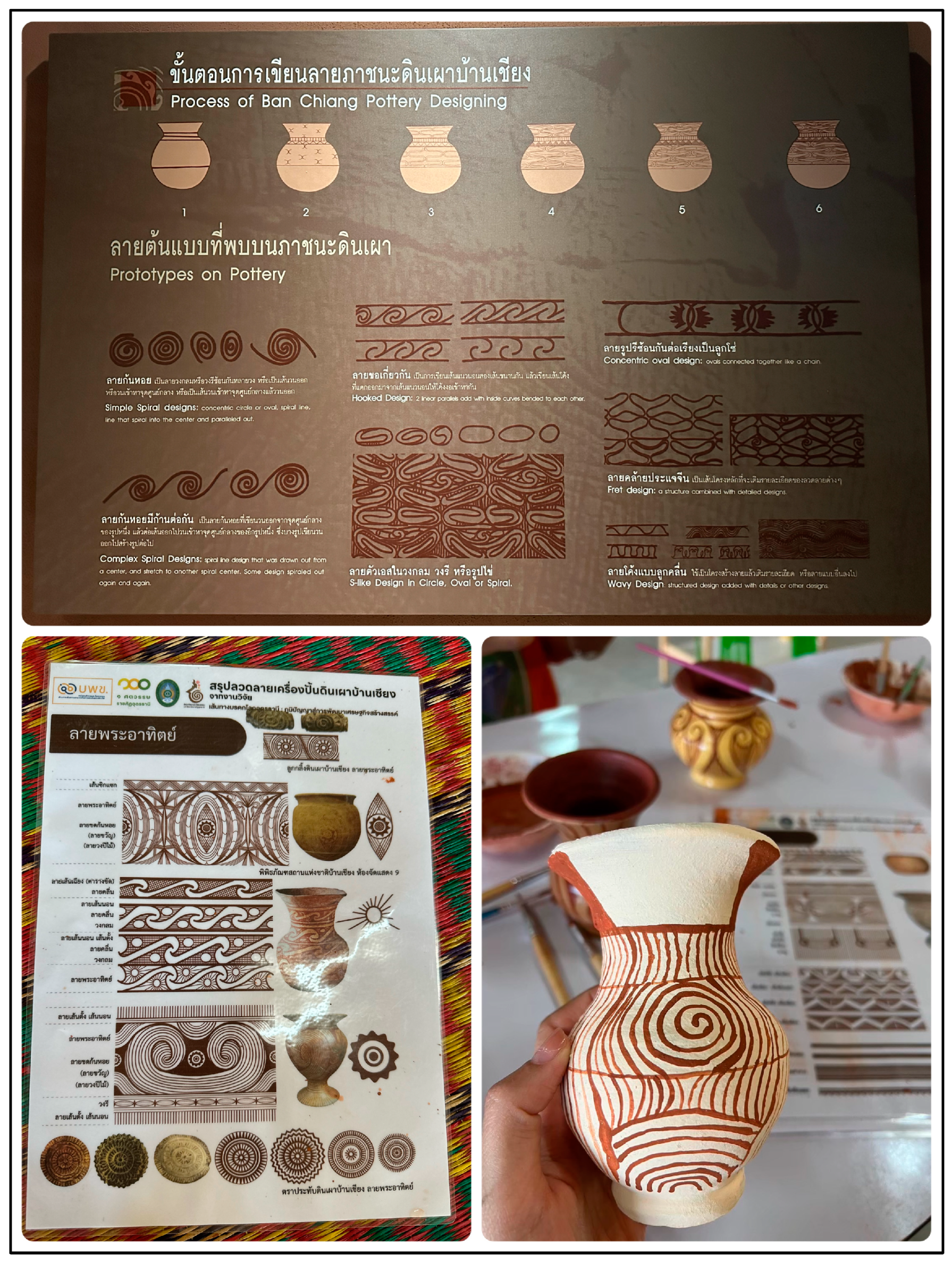

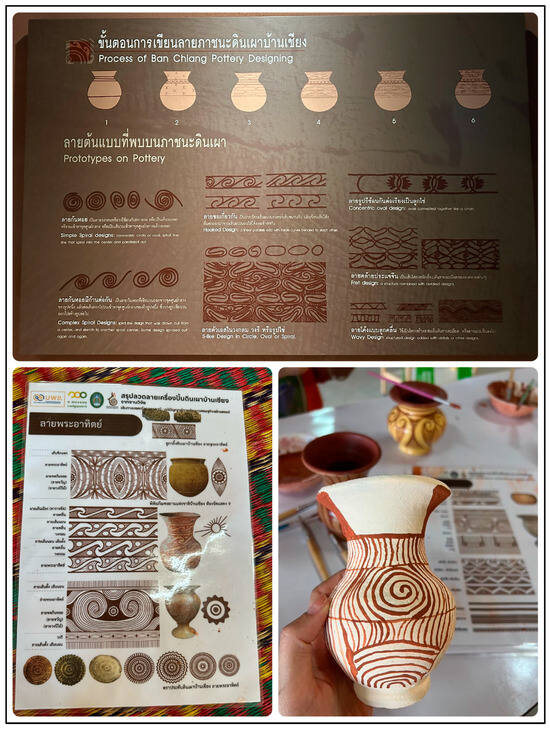

Ban Chiang’s tourism strategy relies on its cultural capital from historical heritage and tradition preservation. Creative activities, co-developed with local enterprises, revitalize community tourism through workshops in pottery (see Figure 7), folk arts, indigo-dyeing, and ethnic food and performances (see Figure 8). These innovations preserve traditions and foster cultural exchange between locals and tourists.

Figure 7.

Ban Chiang Pottery and Painting workshop.

Figure 8.

Local Tai-Puan dishes.

“Since Ban Chiang became a World Heritage Site in 1992, we are dedicated to preserving and celebrating our cultural heritage. Our enterprise integrates traditional practices into our products, ensuring they authentically reflect our unique identity and contribute to Ban Chiang’s legacy.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

“Our enterprise raises awareness of preserving Tai Puan cultural heritage, with community members actively engaging in conservation efforts to ensure the sustainability of our ethnic identity.”—A tourism community enterprise committee/Head of food and folk-dance group(BC-3)

Furthermore, our results from the in-depth interviews highlighted the important role of cultural events and activities in fostering community cohesion and attracting tourists. Cultural capital serves as a driving force for the community’s socio-economic progress.

“By showcasing our cultural heritage through the enterprise, we attract tourists and visitors who are eager to learn about our traditions. This not only generates income but also raises awareness and appreciation for our culture.”—A tourism community enterprise committee/Head of food and folk-dance group(BC-3)

“Our festivals and cultural performances not only preserve our heritage but also create economic opportunities for our local residents.”—A tourism community enterprise member(BC-7)

The Ban Chiang community incorporates ancient patterns from archaeological discoveries into cultural activities. The top image displays traditional pottery patterns found during excavations. The lower left image features an informational sheet detailing the meanings of these patterns, which visitors can use as a reference for their artwork. The lower right image showcases a hands-on workshop where tourists can paint pottery using traditional designs or create their own unique motifs.

The head of the culinary group presents her renowned “Stir-fried Galinga Curry Rice” on the lower left and the local specialty, “Suan Sen”, a version of fresh spring rolls, on the lower right. These dishes are emblematic of Ban Chiang’s gastronomic heritage, showcasing locally sourced ingredients and the culinary expertise of the community.

Through participant observation in Ban Chiang’s artisan workshops—such as pottery making, indigo dyeing, and wicker weaving—it became evident that community members actively engage in hands-on experiences, reinforcing the authenticity and sustainability of traditional practices. Locals passionately teach visitors these skills, demonstrating a strong sense of cultural pride. Additionally, interactions during these activities highlighted how cultural events foster both financial benefits and social cohesion. Notably, in an indigo-dyeing workshop, artisans incorporated storytelling to connect participants with the historical significance of their craft, deepening visitor appreciation.

From a non-participant observation perspective, cultural performances and workshops—such as pottery painting and basket weaving—revealed high tourist engagement. Visitors expressed curiosity, often documenting their experiences through photos and videos. Spontaneous interactions between tourists and locals, such as casual conversations after performances, demonstrated an organic cultural exchange. A folk dance performance during dinner showcased multi-generational involvement, emphasizing cultural continuity and the preservation of heritage through tourism.

5.1.3. Human Capital

At Ban Chiang, human capital was a significant driver of the creative tourism initiatives. The CBT enterprise group focused on its people’s skill development of all artisans, members of the enterprises, and the local youth. Its investments in training and skill development supported its regenerative and creative tourism through enhanced human capital to improve service quality, visitor satisfaction, and local economic opportunities.

“Our trained guides and artisans are the backbone of our tourism enterprise. Their expertise enhances visitor satisfaction and promotes repeat visits.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

Our results also underscored the significance of education and training programs in empowering its community members.

“Investing in human capital through training and skill development not only benefits our tourism sector but also enhances overall community well-being.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

“Our community enterprise offers youth and students roles in tourism, such as guiding tours, performing cultural dances, and cooking local dishes. This helps them earn income, gain skills, and fosters pride in their Tai-Puan heritage.”—A tourism community enterprise committee/Head of food and folk-dance group(BC-3)

Insights from participant observation revealed that Ban Chiang’s investment in human capital translates directly into the quality of visitor experiences. Engaging in artisan workshops, guided tours, and cultural performances demonstrated how skilled locals play a crucial role in shaping positive tourist interactions. Trained guides provided in-depth historical narratives, while artisans actively involved visitors in hands-on activities, enhancing engagement and cultural appreciation. Observing the participation of local youth in tourism-related roles—such as tour guiding, performing cultural dances, and cooking local dishes—highlighted their growing confidence and sense of pride in preserving their Tai-Puan heritage.

From a non-participant observation perspective, it was evident that well-trained community members significantly influenced visitor satisfaction. Tourists frequently praised the knowledgeable guides and enthusiastic artisans, often extending their stay to participate in additional activities. The seamless coordination of tourism services, from workshops to homestays, reflected the effectiveness of skill development programs. Furthermore, spontaneous interactions, such as young performers explaining the meaning behind their traditional dances, underscored how social capital strengthens cultural transmission and economic opportunities within the community.

5.1.4. Social Capital

Social capital was key to Ban Chiang’s creative tourism development. Collective efforts from CBT leaders, locals, entrepreneurs, government, and universities revitalized heritage and innovated tourism experiences. This collaboration enhanced community bonds, trust, and solidarity, fostering dynamic networks that advanced sustainable tourism and community well-being.

“Since establishing our community tourism enterprise, we’ve seen a significant transformation in community dynamics, with strengthened bonds and unity. Guided by our esteemed leader and pride in our Tai Puan heritage, we support each other and uphold the Five Moral Precepts, reflecting our high moral and ethical standards.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

“Our enterprise has strengthened our social bonds within the community. We come together not just for business, but for celebrations, support, and solidarity.”—A community enterprise committee/Head of indigo-dyed cotton group(BC-4)

Moreover, interviews emphasized the role of social networks in promoting tourism entrepreneurship and innovation.

“Through collective actions and shared resources, we’ve been able to launch various community-based tourism projects that benefit everyone.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

Through participant observation, direct engagement in tourism activities such as artisan workshops revealed a strong sense of collective effort in Ban Chiang. Locals worked seamlessly together, demonstrating trust and mutual support when hosting visitors. Community members actively shared responsibilities, highlighting how social bonds facilitate smooth operations.

From a non-participant observation perspective, interactions among stakeholders—such as community leaders, enterprise heads, and committee members—reflected a well-established support network. Observing enterprise meetings emphasized how collaboration drives innovation in tourism offerings. Additionally, spontaneous acts of hospitality, such as villagers inviting visitors to join meals, further underscored the role of social capital in fostering both economic and social well-being.

5.1.5. Political Capital

Political capital was critical in shaping Ban Chiang’s cultural heritage and regenerative tourism landscape. Its creative tourism initiatives strengthened political capital through partnerships with government agencies and policymakers. The strong community advocacy and participation enabled Ban Chiang to influence policy decisions, secure funding, and implement supportive regulatory frameworks for sustainable tourism development.

“Strong partnerships with local authorities and government agencies have been instrumental in securing funding and infrastructure investments for our tourism projects.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

Our results from the in-depth interviews also highlighted the role of policy advocacy and community engagement in influencing decision-making processes.

“Our community enterprise collaborates with local authorities to advocate for policies that protect our village’s unique charm. For example, we requested that the 7-Eleven store align with Ban Chiang’s traditional aesthetics, opting for an earthy design to preserve our UNESCO heritage. This approach helps maintain the village’s character and enhances visitors’ appreciation of our natural beauty”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

“The enterprise has empowered non-tourism community members by giving them a platform to voice their needs and concerns. This inclusivity has increased their political engagement and representation in decision-making bodies”—A tourism community enterprise member(BC-7)

Non-participant observation revealed strong partnerships between tourism leaders and government officials, driving policy implementation. Community advocacy was evident in efforts to align infrastructure with Ban Chiang’s heritage. Spontaneous discussions among villagers showcased growing political engagement and inclusivity in decision-making.

5.1.6. Financial Capital

Financial capital drives tourism growth in Ban Chiang by funding infrastructure and services. Creative tourism supports this growth through diversified offerings and community enterprise networks, attracting tourists, generating income, and boosting socio-economic development.

“Securing funding and access to capital are vital for expanding our tourism offerings and enhancing visitor experiences.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

Moreover, our interviews underscored the role of revenue generation in supporting community development initiatives.

“At our annual community enterprise meeting, we consolidate capital shares, distribute profits, and ensure transparency with clear rules. Profits are partly used to support the less fortunate through cultural events and educational initiatives, enhancing community welfare.”—A tourism community enterprise committee/Head of pottery and painting group(BC-2)

5.1.7. Built Capital

Built capital played a significant role in shaping Ban Chiang’s tourism infrastructure. Its stakeholders highlighted the importance of physical amenities and facilities in providing essential services to all visitors. Effective management of the infrastructure and maintenance improved our tourism productivity and community well-being toward socio-economic progress.

“We’ve partnered with local government to improve community infrastructure, including upgraded restrooms, enhanced signage, and well-maintained pathways, boosting both well-being and attractiveness for residents and visitors.”—A tourism community enterprise leader/Head of homestay group(BC-1)

The results from our interviews also emphasized the need for sustainable development and infrastructure planning to mitigate cultural impacts.

“We focus on culturally sensitive infrastructure that preserves heritage and boosts visitor satisfaction. For example, our 7-Eleven features a unique exterior that complements the village ambiance, aligning with our cultural preservation goals.”—A tourism community enterprise committee/Head of pottery and painting group(BC-2)

5.2. Impacts of Community Capitals on Creative Tourism

The findings highlight creative tourism as a key driver for revitalizing cultural heritage and regenerating tourism at Ban Chiang, a UNESCO site. The Community Capitals Framework (CCF) proves effective for developing creative tourism strategies. Table 3 summarizes the key impacts, showing how Ban Chiang’s community enterprise group successfully used the CCF to enhance tourism development.

Table 3.

Summary of Key Impacts on Ban Chiang Creative Tourism.

Creative tourism at Ban Chiang emphasizes regenerating tourism and preserving cultural heritage. Tourists enjoy serene rural landscapes and participate in cultural workshops, which promote educational exchanges and enhance cultural knowledge. Strong community engagement, social networks, and collaboration among local enterprises support this approach. The integration of cultural, human, and financial capital boosts infrastructure, diversifies the local economy, and promotes socio-cultural growth, underscoring the importance of revitalized community capitals for sustainable tourism development.

6. Discussion and Implications

Overall, the findings of our study expand the currently limited knowledge and address the critical research inquiry about how the creative tourism approach can support Community-Based Tourism (CBT) development and how communities can achieve sustainable socio-economic growth using the Community Capitals Framework (CCF). We provide insights about how the adoption of creative tourism strategies within a community-based tourism framework can innovatively optimize tourism development, enhance cultural preservation, and promote sustainable outcomes. Importantly, the results show that creative tourism strategies can be instrumental in promoting environmental conservation, cultural preservation, economic empowerment, and social well-being in the UNESCO heritage site at Ban Chiang.

In general, the Ban Chiang community tourism enterprise network has implemented creative tourism initiatives based on principles from Richards (2021) [20]. They began by understanding Ban Chiang’s unique features, heritage, and natural beauty. They leverage the local capacity by engaging artisans to create compelling narratives, such as hands-on pottery workshops to showcase the ancient Tai Puan techniques. The enterprise repurposes existing spaces for cultural events, such as transforming a community center into a storytelling hub. They put emphasis on the vivid traditional heritage and cultural activities, such as culinary tours featuring traditional Tai Puan dishes. Creative collaborations between multi-stakeholders, including tourists and artists, have led to new artworks reflecting the rich Ban Chiang’s heritage. These efforts enrich visitors’ experiences while preserving and promoting the community’s cultural identity and sustainable tourism development.

Our study on the community capitals in community-based creative tourism aligns with the existing literature and further discover critical insights. The finding indicates that the active community involvement is crucial for creative tourism by enhancing authenticity and uniqueness, as noted by Duxbury et al. (2020) [1]. Communities with strong social capital (trust, networks, and norms) are more successful, supporting Hidalgo et al. (2024) [29] on the role of social capital in collective actions and economic development. Our research confirms that creative tourism generates income, creates jobs, and stimulates local economies, aligning with the literature (Richards (2020) [15]).

Creative tourism also aids in preserving cultural heritage, reflecting Emery & Flora (2020) [12] and UNESCO (2020) [9]. Leveraging cultural assets such as traditions and local knowledge enhances tourism and strengthens local identity, as suggested by Wallace (2019) [26]. Our findings also support the previous study (Richards (2020) [15]) on developing local creative capacities to diversify tourism offerings. We also highlights the key challenges, such as cultural commodification, and the need for capacity building. And, our study suggests a balanced approach to maintain cultural integrity while ensuring economic viability.

Our study also reveals the interesting results of the creative tourism practices, based on the Community Capitals Framework (CCF), for sustainability at the UNESCO World Heritage at Bang Chiang. Importantly, this study puts forward the importance of the cultural heritage revitalization and its community enterprise development as the instrumental sustainable development strategies. The successful optimization and implementation of the existing community capitals, such as its social networks, cultural heritage, and natural resources, can well support the socio-economic growth of the community. By utilizing these existing assets with creativity and supportive capitals, our research suggests that communities can create unique, participatory tourism experiences that attract visitors seeking authenticity and immersion. It is suggested that the utilization of community capital can be a fundamental strategic step for transforming local assets into creative tourism offerings with immersive cultural and economic values.

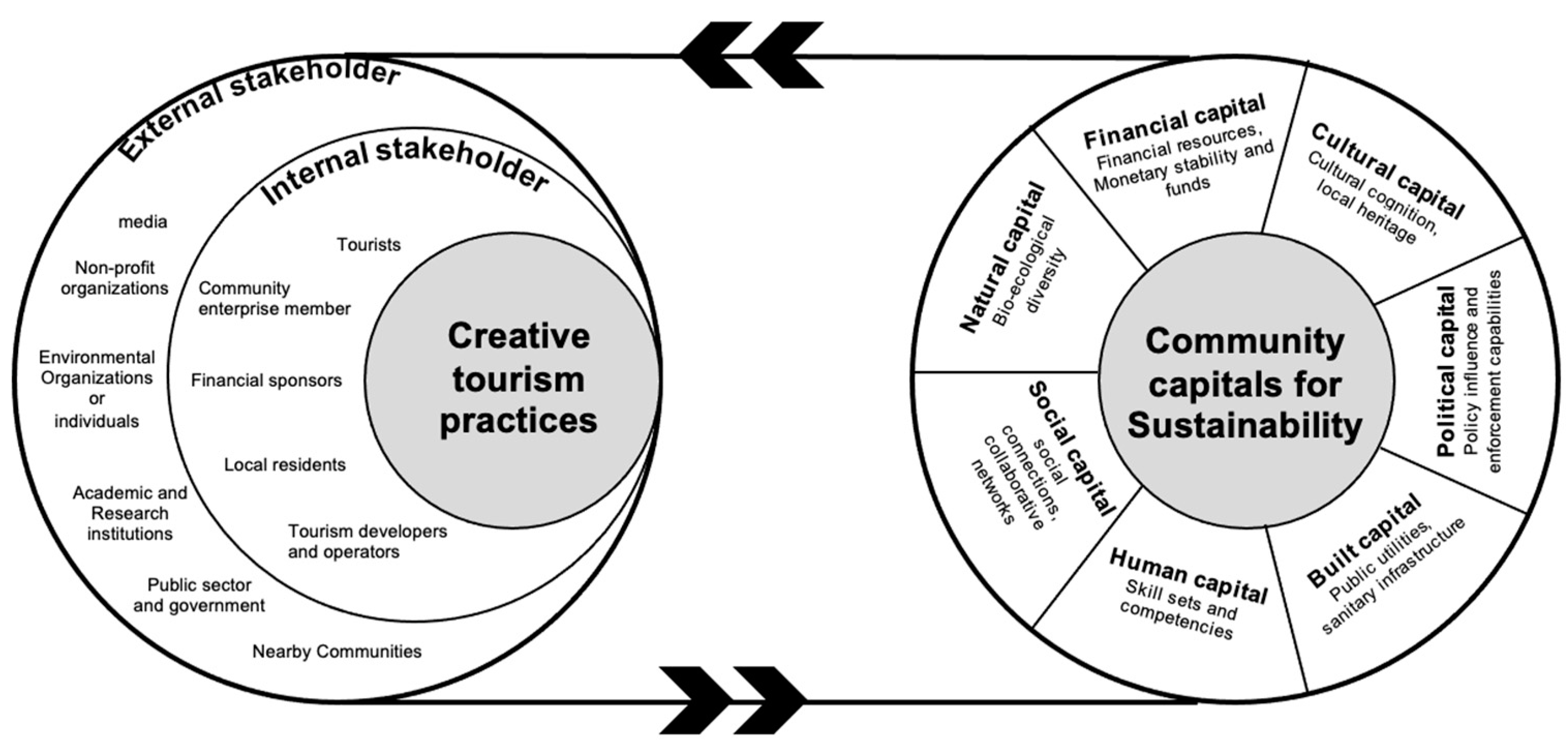

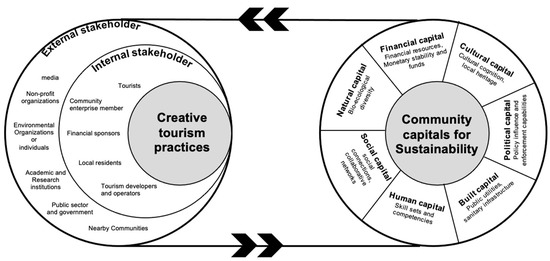

In this study, we expand the limited knowledge in the underdeveloped field by proposing a creative tourism practice for community capital development toward sustainability, as exhibited in Figure 9. Figure 9 highlights the importance of the creative tourism strategy as an instrumental development for sustainability in community-based tourism. The diagram visualizes our proposed model that explains the interrelationship of the reinforced loop between regenerative creative tourism practices and revitalized community capitals for sustainability. It illustrates the importance of multilateral stakeholder collaborations from both the internal and external stakeholders as the critical requirement for co-creative tourism development. The reciprocal association can support the growth of multi-dimensional community capitals for enhanced sustainability and socio-economic development in the long run.

Figure 9.

A proposed model for a creative tourism strategy and community capital development for sustainability.

A proposed model illustrating the relationship between creative tourism strategy and community capital development for sustainability. The model shows how creative tourism practices can enhance sustainability by leveraging the community capitals using the developmental framework of CCF—Natural, Cultural, Human, Financial, Built, Political, and Social—as assets. It also depicts how both internal and external stakeholders are involved in developing creative tourism strategies and practices, highlighting the interconnectedness between these elements.

Our findings suggest that creative tourism can enhance the community capitals in several ways. The economic capital increases through job creation and tourism revenue, while the social capital grows as the community collaboration strengthens trust and cooperation. The cultural capital expands as local traditions are revitalized and celebrated. These capitals reinforce each other, creating a virtuous cycle of community development.

The growth in the community capitals can support sustainability by improving livelihoods and reducing migration while also fostering a strong sense of identity. Increased economic resources can be reinvested in sustainable tourism, cultural projects, and infrastructure, leading to resilient community development.

In summary, our proposed dynamic cycle from the model can enhance community sustainability, leading to further capital growth and innovation in the creative tourism. This ongoing interplay between the community capitals and tourism practices promotes socio-economic development and sustainable growth.

In practice, it is suggested that community leaders and social entrepreneurs should focus on building their community capitals using our proposed model in practice. They may collaboratively engage various stakeholders, such as local artisans, performers, and cultural practitioners, along with other relevant external stakeholders like universities and government institutions. We also highlight that co-creating innovative tourism activities with active participation can enhance experiences and ensure fair economic benefits. Building strong local networks and investing in skill development, such as workshops in arts and tourism management, can also support the social and human capital growth. Notably, all community-based sustainable tourism practices should aim to protect the cultural heritage and natural environments.

For policymakers, fostering an enabling environment for creative tourism is crucial. They should support community participation in tourism planning through grants, subsidies, and participatory platforms. Investments in training programs for cultural management, heritage revitalization, and entrepreneurship are essential. Additionally, improving infrastructure, such as cultural centers and transportation and promoting creative tourism through marketing campaigns, can help spotlight unique cultural experiences and support rural development toward sustainable community-based tourism.

Lastly, our study underscores the importance of how to strategically leverage the community capitals to co-create creative tourism initiatives and support sustainable development and sustainability. The reciprocal relationship between the strategic development of the creative tourism and the community capitals can foster economic, social, and cultural sustainability. Importantly, our findings provide valuable insights from scholastic advancement to practical implications for academics, social entrepreneurs, practitioners and policymakers alike. Overall, the suggested integrated approach and proposed model for sustainable tourism can ensure that creative tourism continues to be a vibrant, sustainable gateway for local economic growth and community resilience.

7. Limitation and Suggested Future Research

This research offers insights into integrating creative tourism within community-based tourism at Ban Chiang, but it has limitations. Its focus on Ban Chiang may limit generalizability, and using qualitative data alone with the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) might not capture all community experiences. External factors such as economic shifts or political changes could affect outcomes, impacting validity.

Future research could compare diverse cultural heritage sites to assess the transferability of creative tourism strategies and explore mixed methods approaches for a comprehensive understanding. Additionally, integrating ICT innovations such as virtual or augmented reality could enhance tourism experiences and attract diverse visitors, advancing our understanding of creative tourism.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, this research provides insights into integrating creative tourism within the community-based tourism framework at Ban Chiang, Thailand, using the Community Capitals Framework (CCF). This study highlights how creative tourism impacts various community capitals—natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial, and built—enhancing cultural preservation, economic growth, community empowerment, and environmental stewardship. Involving local communities in tourism can generate better livelihood, economic opportunities and strengthens social cohesion.

Acknowledging this study’s limitations, future research should compare different destinations, use mixed methods, and explore technological innovations in tourism. These findings offer practical implications for tourism practitioners, policymakers, and community stakeholders, helping design sustainable tourism strategies that maximize benefits while minimizing negative impacts.

Overall, this research advances the currently-limited theoretical understanding of creative and community-based tourism. It informs practical destination management, and suggests future research directions for sustainable tourism development. Last, but not least, our study puts forward the importance of creative tourism as it can positively impact sustainable socio-economic community development and sustainability in the long run.

Author Contributions

S.S. acquired the funding, conceptualized, supervised the research study, collected data, and finalized the manuscript; K.K. and S.T. participated in data collection, validation, analysis, and preparation of the draft manuscript; S.L. supported data collection and the draft manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project has been funded by Mahidol University (Fundamental Fund: fiscal year 2024 by National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF)).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Mahidol University (protocol code MU-CIRB 2023/340.3110).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and all reviewers for their invaluable comments and advice. We also thank the research participants for their participation in the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duxbury, N.; Bakas, F.E.; Vinagre de Castro, T.; Silva, S. Creative Tourism Development Models towards Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Cities, Culture, Creativity: Leveraging Culture and Creativity for Sustainable Urban Development and Inclusive Growth. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377427 (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Sheldon, P.J. Designing Tourism Experiences for Inner Transformation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziliauske, E. Innovation for Sustainability through Co-creation by Small and Medium-sized Tourism Enterprises (SMEs): Socio-cultural Sustainability Benefits to Rural Destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 50, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Sadhukhan, S. Progress in Creative Tourism Research: A Review for the Period 2002–2023. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, L.; O’Shaughnessy, M. Community-Based Social Enterprises as Actors for Neo-Endogenous Rural Development: A Multi-Stakeholder Approach. Rural Sociol. 2022, 87, 1191–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krittayaruangroj, K.; Suriyankietkaew, S.; Hallinger, P. Research on Sustainability in Community-based Tourism: A Bibliometric Review and Future Directions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M. Community-based Tourism Development Model and Community Participation. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee. Ban Chiang Archaeological Site. 2020. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/575/ (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Gozzoli, P.C.; Gozzoli, R.B. Outstanding Universal Value and Sustainability at Ban Chiang World Heritage, Thailand. Herit. Soc. 2021, 14, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, H.; Al Atrees, M.A.H. Developing New forms of Tourism Based on Intangible Culture Heritage and Creativity in Egypt. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, M.; Flora, C. Spiraling-up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework. In 50 Years of Community Development Vol I; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, E.; Kim, J.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Ash, K. Does Tourism Matter in Measuring Community Resilience? Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, R.S.; Lück, M.; Schänzel, H.A. A Conceptual Framework of Tourism Social Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Community Development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Designing Creative Places: The Role of Creative Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar]

- Jovicic, D. Cultural tourism in the context of relations between mass and alternative tourism. Current Issues in Tourism 2016, 19, 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Pearce, D.G. Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Suntikul, W.; King, B. Research on Tourism Experiencescapes: The Journey from Art to Science. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1407–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Patuleia, M. Developing Poor Communities through Creative Tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Business models for creative tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wattanacharoensil, W.; Schuckert, M. Reviewing Thailand’s Master Plans and Policies: Implications for Creative Tourism? Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1045–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Wisansing, J.J.; Paschinger, E. Creating Creative Tourism Toolkit; DASTA: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wisansing, J.J.; Vongvisitsin, T.B. Local Impacts of Creative Tourism Initiatives. In A Research Agenda for Creative Tourism; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Musavengane, R.; Kloppers, R. Social Capital: An Investment towards Community Resilience in the Collaborative Natural Resources Management of Community-based Tourism Schemes. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100654. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, L.N.; Kline, C.; Swanson, J.R.; Best, M.; McKinnon, H. Community development through agroecotourism in Cuba: An application of the community capitals framework. In Effecting Positive Change through Ecotourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, D. The racial politics of cultural capital: Perspectives from Black middle-class pupils and parents in a London comprehensive. Cult. Sociol. 2019, 13, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zumba-Zúñiga, M.F.; Martínez-Fernández, V.-A. Influence of human capital in the innovation process of tourism companies in the Ecuadorian Austro. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2023, 40, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, T.; de Faria, P.; Lima, F. Human capital and innovation: The importance of the optimal organizational task structure. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, G.; Monticelli, J.M.; Vargas Bortolaso, I. Social capital as a driver of social entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2024, 15, 182–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.; Ma, H.; Qi, G.; Tam, V.W. Can political capital drive corporate green innovation? Lessons from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pigg, K.; Gasteyer, S.P.; Martin, K.E.; Keating, K.; Apaliyah, G.P. The community capitals framework: An empirical examination of internal relationships. In 50 Years of Community Development Vol I; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, C.; McGehee, N.; Delconte, J. Built capital as a catalyst for community-based tourism. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 899–915. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, J.M.; Deller, S.C.; Leyden, K.M. Social Capital and Community Development: Where do We Go from Here? Community Dev. 2022, 53, 92–108. [Google Scholar]

- Altinay, L.; Sigala, M.; Waligo, V. Social value creation through tourism enterprise. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R. Governance and sustainable tourism: What is the role of trust, power and social capital? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, B.; Wornell, R.; Youell, R. Re-conceptualising rural resources as countryside capital: The case of rural tourism. J. Rural. Stud. 2006, 22, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Murdana, I.; Paturusi, S.A.; Suryawan Wiranata, A.A.P.; Mandala, H.; Suryawardani, G.A.O. Community Involvement and Participation for Sustainable Tourism: A Case Study in Gili Trawangan Post-earthquake. Asia-Pac. J. Innov. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 10, 319. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee. Baku declaration on the protection of cultural and natural heritage. In Proceedings of the 43rd Session of the World Heritage Committee, Baku, Azerbaijan, 30 June–10 July 2019; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/sessions/43COM (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- ICOMOS New Zealand. Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value, New Zealand, October 1992; ICOMOS: Auckland, New Zealand, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Peleggi, M. Monastery, Monument, Museum: Sites and Artifacts of Thai Cultural Memory; University of Hawaii Press: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ban Chiang Subdistrict Municipality. Ban Chiang Subdistrict Profile; Ban Chiang Subdistrict Municipality: Nong Han, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, P.G. Theorising visitor learning in ecotourism. J. Ecotour. 2013, 12, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo, C.G.; Knollenberg, W.; Barbieri, C. Inputs and Outputs of Craft Beverage Tourism: The Destination Resources Acceleration Framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103102. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, S.; Newman, C.; Lancaster, K. Qualitative Interviewing; Springer Nature: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2019; pp. 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups and Social Interaction. The Sage Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft 2012, 2, 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, A.; Geerling, T.; Gregory, W.J.; Kagan, C.; Midgley, G.; Murray, P.; Walsh, M.P. Systemic Evaluation: A Participative, Multi-method Approach. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2007, 58, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic Analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Smith, J.A., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2015; pp. 222–248. [Google Scholar]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–607. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).