Outdoor Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Questions

- What are the trends in the annual distribution of OESD?

- What are the research development trends and core elements of OESD?

- What are the highly productive countries and regions in OESD?

- What are the challenges and opportunities in OESD?

2. Data and Methods

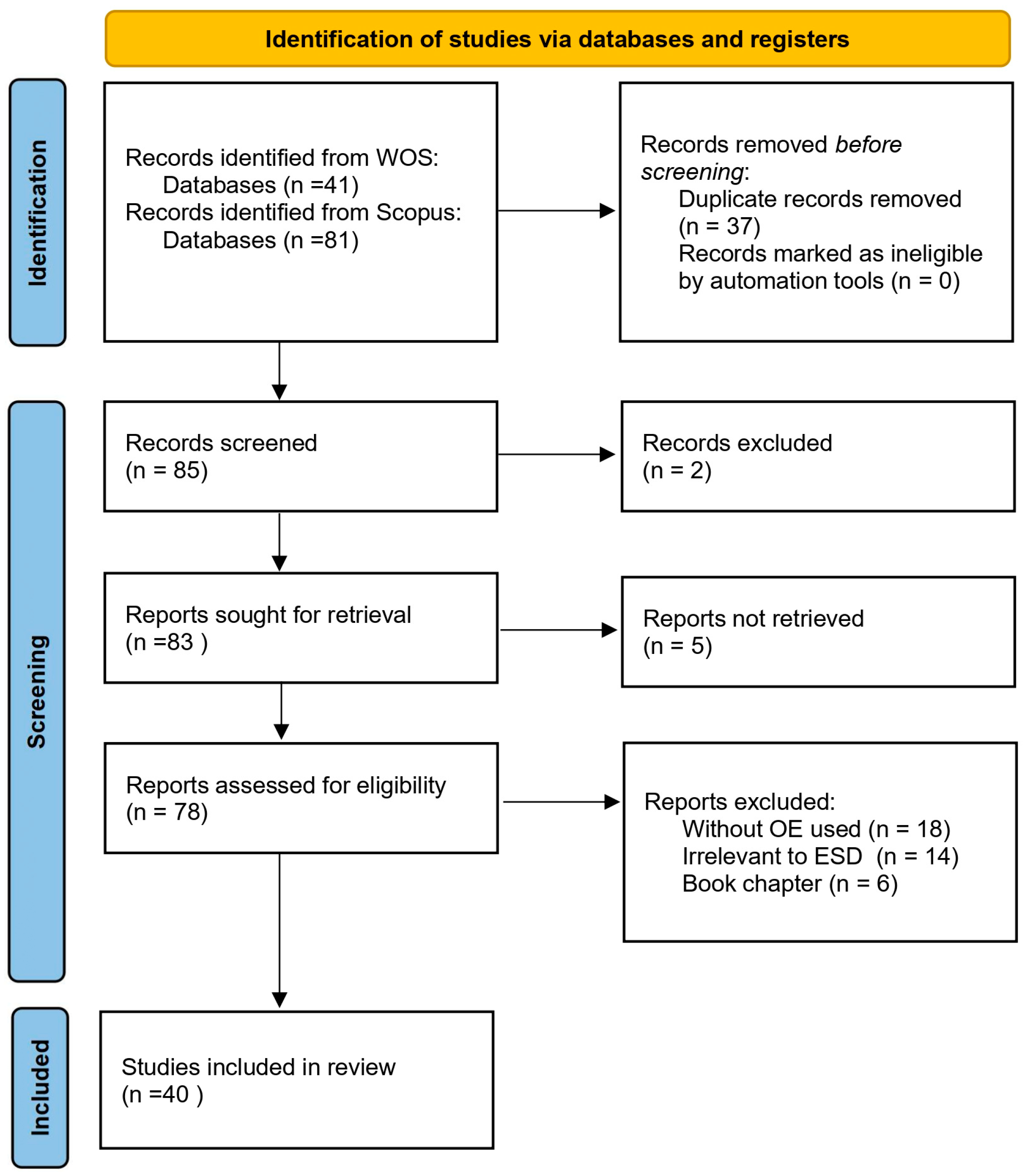

2.1. Data Collection and Processing

2.2. Analysis of Document Coding

3. Results

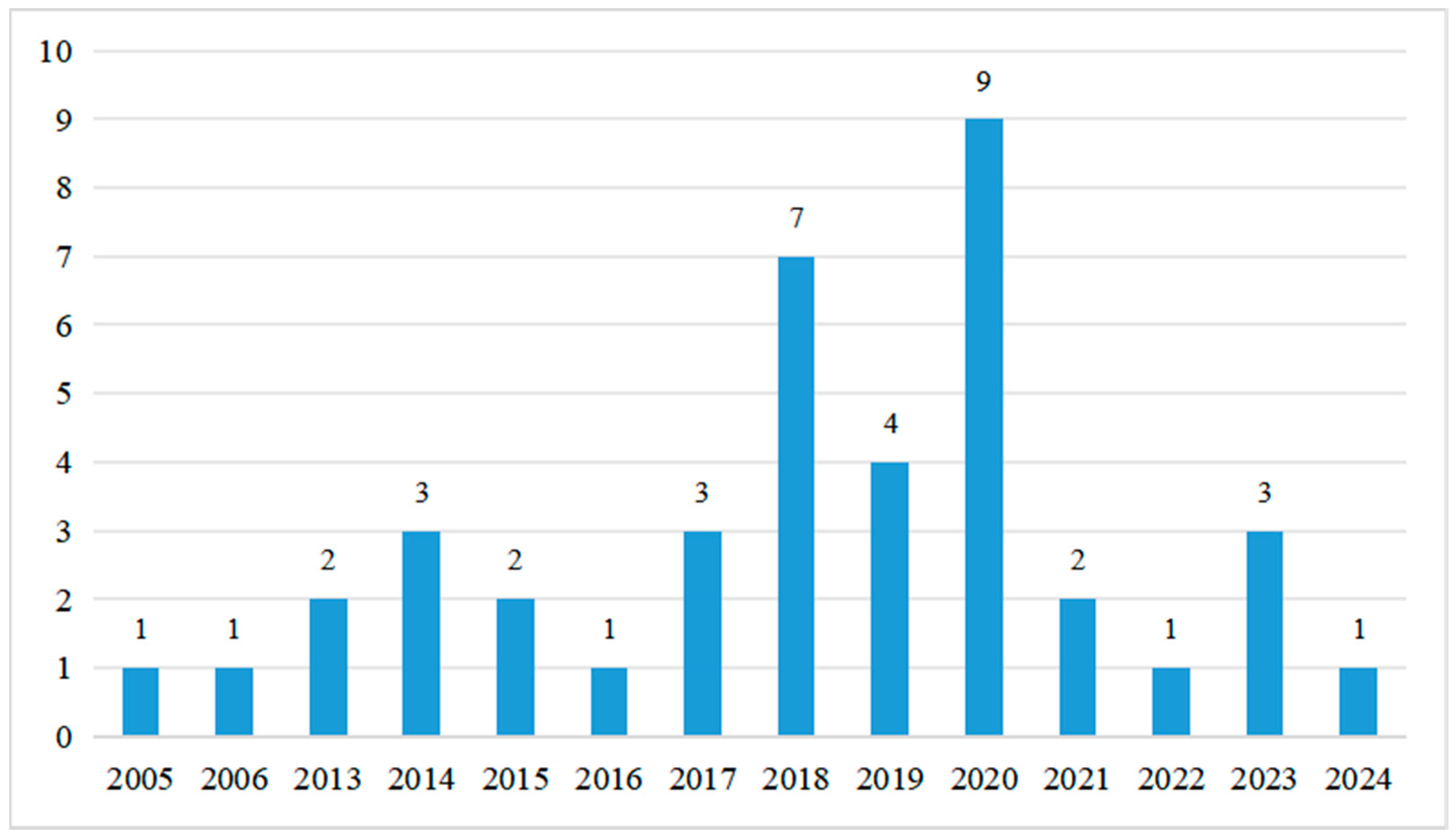

3.1. Yearly Distribution of OESD

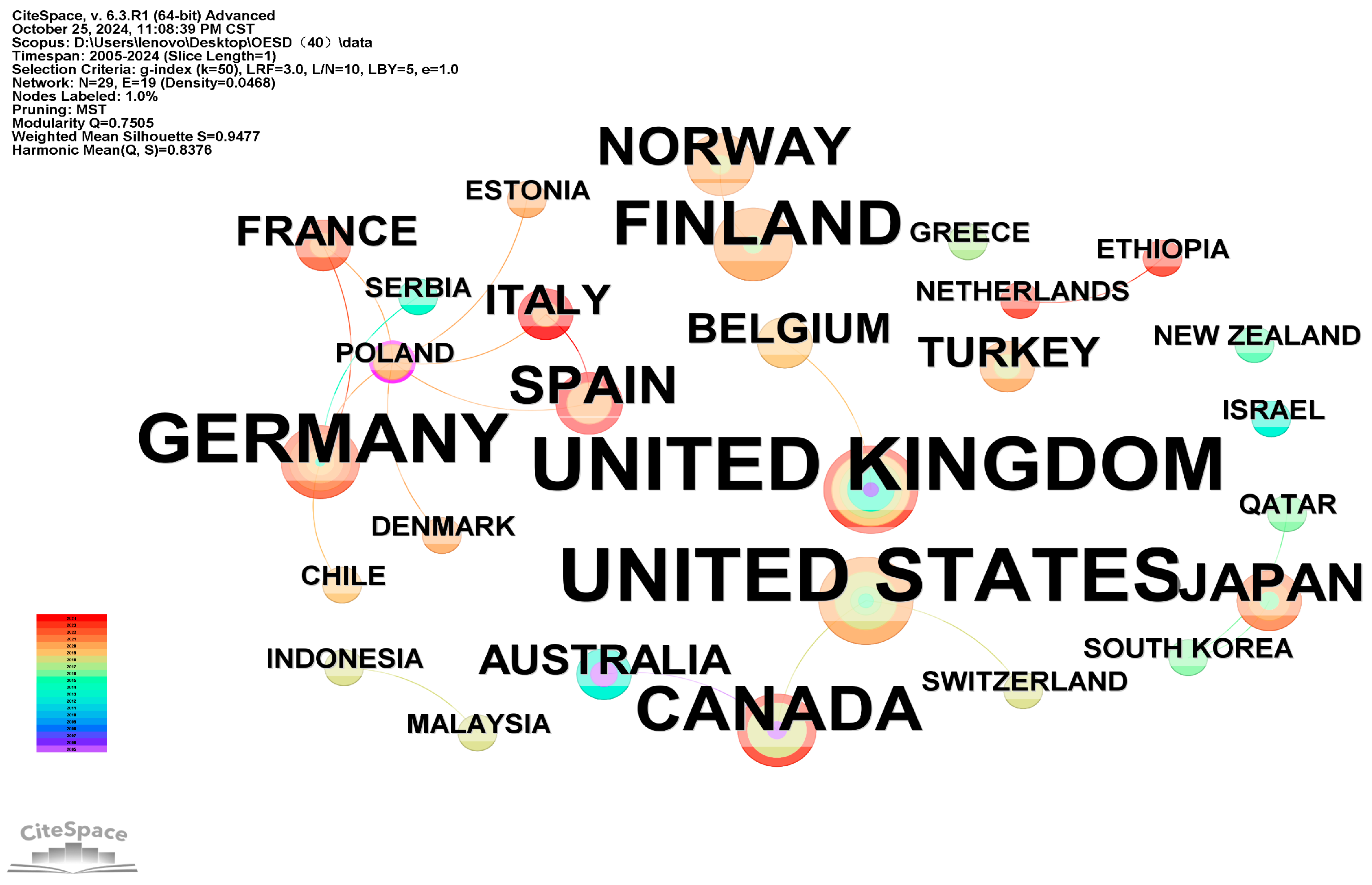

3.2. Prolific Institutions and Countries/Regions

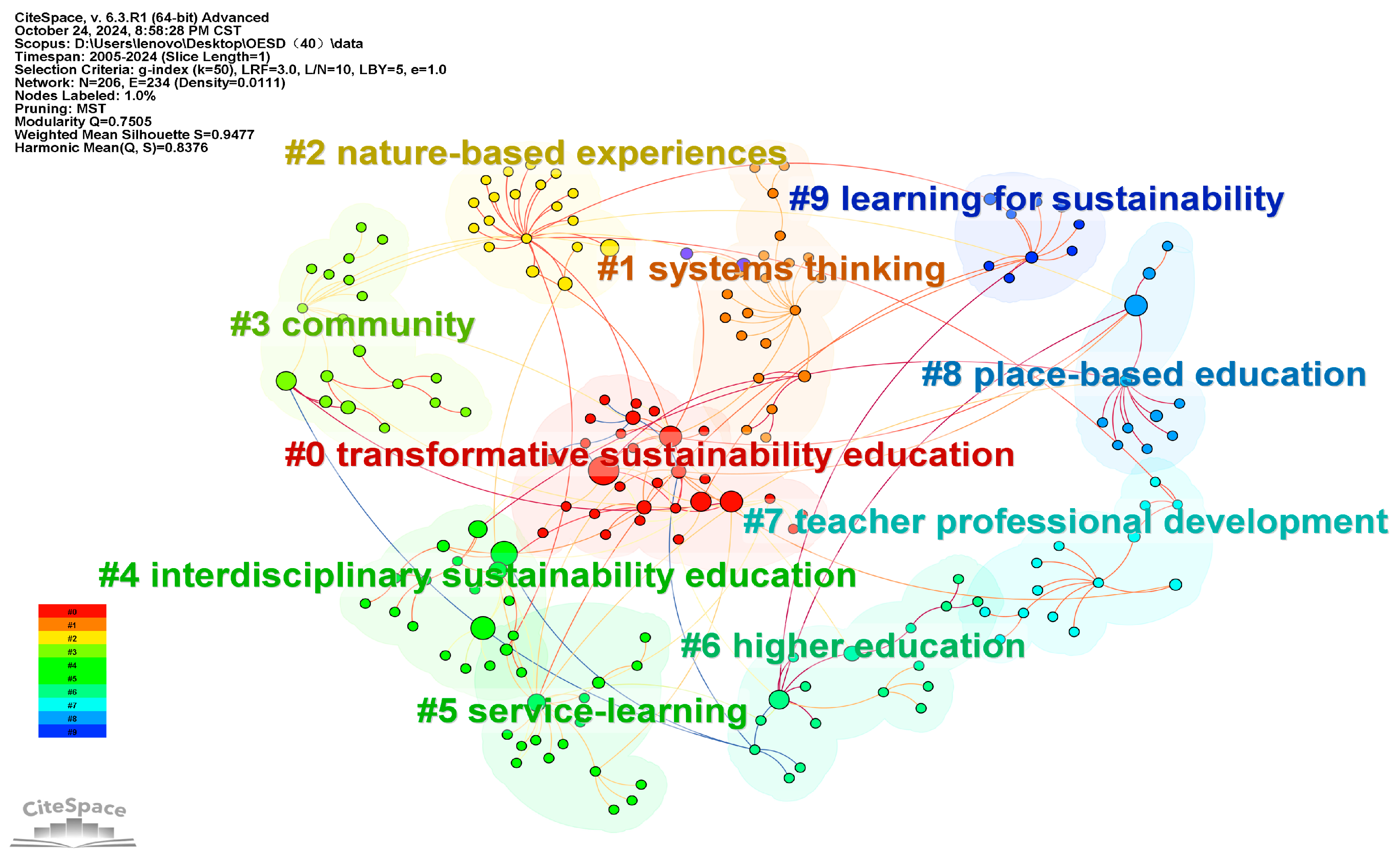

3.3. Research Topics of OESD

3.3.1. Roots: Theories and Disciplines

3.3.2. Practice: Experiences and Actions

3.3.3. Connection: Community and Academia

3.3.4. Cultivation: Educators and Learners

3.4. Developmental Changes of OESD

3.4.1. Change 1: Teaching Content

3.4.2. Change 2: Education Stage

3.4.3. Change 3: Teaching Technology

4. Discussion

4.1. How to Understand “Outdoor”

4.2. How to Understand “Sustainable”

4.3. How to Understand “Transformative Development”

4.3.1. Change for Teachers

4.3.2. Change for Students

- 1.

- Knowledge growth: Increased knowledge influences behavior, and OESD enhances students’ knowledge in areas such as environmental science, ecology and social sustainability through hands-on activities. Through OESD, students are able to train or deepen their observational skills through sensory experiences, link cognition with sensory and emotional appeal, promote the relationship between humans and nature, increase students’ awareness of environmental issues, and stimulate positive attitudes and motivation. Nature-based learning demonstrates evidence of positively influencing participants’ environmental knowledge, attitudes, and pro-environmental behavior [29].

- 2.

- Creativity development: Education is not merely the transfer of knowledge or the imposition of predefined answers, but rather a space for dialogue that fosters new perspectives and enhances both individual and group creativity [47]. In addressing challenges in the outdoor environment, students are encouraged to be creative and to design and implement innovative solutions. This process not only stimulates students’ creative thinking, but also enhances their ability to transform ideas into practical actions.

- 3.

- Normative competence development: OESD develops students’ moral principles and behavioral standards by emphasizing environmental ethics and social responsibility. In the process, students learn how to respect nature, respect cultural diversity, and consider ethics and sustainability in their decision-making.

- 4.

- Improvement of communication and co-operation skills: Communication and co-operation in OESD encompass interactions with oneself, others, society, and nature. Through team projects and collaborative activities, students learn to articulate their findings, present results, defend their views, communicate effectively, consider others’ perspectives, and reconcile differing interests.

- 5.

- Critical thinking development: OESD encourages students to critically analyze the functioning of natural environments and social systems, question existing viewpoints, form independent opinions, and make informed judgments on social and environmental issues.

- 6.

- Future thinking and action: Developing the ability to take meaningful action is a cornerstone of OESD, emphasizing the transition from knowledge acquisition to deliberate action and problem-solving [33]. OESD emphasizes the development of long-term planning skills and forward-thinking, enabling students to consider the impact of their actions on future generations. Students are encouraged to embrace uncertainty, remain receptive to unforeseen challenges, navigate the complexities of their situations, and explore pathways toward an uncertain future.

4.3.3. Change for Learning

4.4. Future Opportunities and Challenges for OESD

4.4.1. Opportunities for OESD

- Policy support is one of the key factors in the implementation of OESD. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) promoted the Global Decade of Sustainable Development in Education from 2005 to 2014, aiming at integrating the principles, values and practices of sustainable development into all aspects of education [44]. This global policy framework provides guidance and motivation for countries and promotes the development of OESD. For example, in 2006, the Japanese government made an implementation plan to promote the goal of UNESCO’s Decade of Sustainable Development in Education, emphasizing the change of behavior through education to achieve environmental, economic and social sustainability. In addition, UNESCO announced the Global Action Plan (GAP) in 2015, encouraging local communities and municipal authorities to develop community-based ESD projects, and emphasizing strengthening learning opportunities through multi-participation [28]. These policies not only provide the direction for OESD, but also promote international co-operation and resource sharing, providing a solid foundation for the implementation of OESD.

- The support of local practice and cultural background to OESD cannot be ignored. Scotland became one of the first places in the world to receive outdoor education formally in the 1960s [7]. This local practice provides OESD with rich experience and cultural soil. The influence of environmental attitude and knowledge on behavior will be different due to social and geographical background factors [48]. This means that OESD needs to consider the specific needs and challenges in different social and economic backgrounds. For example, Japan supports ESD implementation in all education sectors at the national level, and many universities have implemented ESD-related projects and activities [28]. This support at the national level provides resources and motivation for OESD.

- The existing curricula are also important to support OESD. Finland incorporates sustainability into the curriculum at all educational levels, which is reflected in the basic education curriculum [26]. Norway’s national framework plan defines sustainable development as one of the core values of kindergartens, which requires promotion, practice and embodiment in kindergarten education practice [54]. In New Zealand, the connection between outdoor learning and sustainable education has been reflected in the education system, which can be traced back to the end of the 19th century. Australia also regards sustainability as one of the three cross-curricular priorities of the new national curriculum [31]. These curriculums not only emphasize the importance of sustainability, but also provide a concrete implementation framework for OESD.

4.4.2. Challenges for OESD

- The contradiction between globalization initiatives and localization practices has become a significant threat. Although all countries have reached consensus on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the vast differences in ecological foundations, development stages, and cultural contexts across regions present profound challenges to the implementation of OESD. Taking developed countries as examples, their educational goals focus on post-industrial societal transformation needs: the UK advocates building sustainable community consumption systems [46], the US emphasizes creating safe and resilient cities [8], while Finland prioritizes biodiversity education [26]. These initiatives align well with SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 15 (Life on Land) in the global agenda, yet prove difficult to directly transplant to developing countries. Developing countries face more fundamental survival challenges, such as Brazil advocates sustainable Food Program (SDG 2 Zero Hunger) [34]. The challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa are even more complex, requiring breakthroughs in environmental degradation, social conflicts, cultural hegemony, and other obstacles [62]. Therefore, the implementation of OESD must comprehensively consider regional social, economic, environmental, and cultural characteristics. Though challenging, only through this approach can the transformative value from global vision to local action be truly realized.

- The implementation of OESD is limited by the existing education system. For example, in Scotland, although the national curriculum standards allow teachers to guide young students to participate in outdoor activities, the curriculum requirements for older students are stricter, which limits the opportunities for outdoor learning. In addition, the disconnection between college students and the outdoors may be more serious, which indicates that higher education institutions may not make full use of the outdoor environment as teaching resources [8]. In Kosovo, the education system mainly serves the political power, and teaching focuses on imparting selected knowledge, leaving little room for students to explain themselves, take the initiative or think critically [9].

- Insufficient resources and support are also constraints. For example, teachers lack enough knowledge and time to provide OESD, and it is difficult to rely only on school resources [11]. In addition, the lack of technical equipment and funds is also an obstacle to implementing OESD [39,41]. Social and cultural factors also pose challenges to OESD. For example, fear and worry about students’ health and safety, as well as lack of time, are all factors that affect the implementation of OESD [26]. These factors limit the potential of OESD and make it difficult to be applied in a wider range of educational practice.

- The promotion of OESD also faces management and organizational challenges. For example, academic institutions usually have their own courses created by scientific educators, and local governments or communities are less involved in the educational process because of the barriers to co-operation, which sometimes leads to a lot of confusion in the process of education management [28]. The success of OESD also depends on students’ participation and perspective, however, educators overestimate the transformative power of a single initiative, and without in-depth study of students’ viewpoints, it is difficult to know to what extent OESD has affected students’ sustainability [33,63]. To realize interdisciplinary communication, it is necessary to modify the rigid administrative structure and unify students, teachers, employees, administrators and communities through innovative activities, so as to ensure that OESD can be effectively integrated into the education system [51].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Agbedahin, A.V. Sustainable development, Education for Sustainable Development, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Emergence, efficacy, eminence, and future. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 669–680. [Google Scholar]

- UN. SDG 4 Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. Available online: https://tcg.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/09/Metadata-4.7.4.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Lähdemäki, J. Case study: The Finnish national curriculum 2016—A co-created national education policy. In Sustainability, Human Well-Being, and the Future of Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 397–422. [Google Scholar]

- GOV.UK. Sustainability and Climate Change: A strategy for the Education and Children’s Services Systems. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sustainability-and-climate-change-strategy/9317e6ed-6c80-4eb9-be6d-3fcb1f232f3a (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Irwin, D.; Straker, J. Tenuous affair: Environmental and outdoor education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 30, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirreazkuenaga, L. Education for Agenda 2030: What direction do we want to take going forward? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.G. Place-based inquiry in a university course abroad: Lessons about education for sustainability in the urban outdoors. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 895–910. [Google Scholar]

- Hyseni Spahiu, M.; Korca, B.; Lindemann-Matthies, P. Environmental education in high schools in Kosovo—A teachers’ perspective. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2014, 36, 2750–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.; O’Flaherty, J. Addressing education for sustainable development in the teaching of science: The case of a biological sciences teacher education program. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Q.; Inoue, Y. Driving network externalities in education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallette, A.; Heaney, S.; McGlynn, B.; Stuart, S.; Witkowski, S.; Plummer, R. Outdoor education, environmental perceptions, and sustainability: Exploring relationships and opportunities. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.; Christie, B.; Nicol, R.; Higgins, P. Space, Place and Sustainability and the Role of Outdoor Education; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Fröberg, A. Towards a more sustainable future: Simple recommendations to integrate planetary health into education. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e868–e873. [Google Scholar]

- Jucker, R.; von Au, J. Outdoor learning—Why it should be high up on the agenda of every educator: Introduction. In High-Quality Outdoor Learning: Evidence-Based Education Outside the Classroom for Children, Teachers and Society; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jegstad, K.M.; Gjøtterud, S.M.; Sinnes, A.T. Science teacher education for sustainable development: A case study of a residential field course in a Norwegian pre-service teacher education programme. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2018, 18, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.; Brown, M. Intersections between place, sustainability and transformative outdoor experiences. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2014, 14, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, J.; Baillieul, E.; Quay, J. Investigating outdoor education in Finland and Australia: Positioning outdoor education as curriculum. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Hoof, J.; Van Petegem, P. Effective field trips in nature: The interplay between novelty and learning. J. Biol. Educ. 2019, 53, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, R. Entering the Fray: The role of outdoor education in providing nature-based experiences that matter. Educ. Philos. Theory 2014, 46, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.K.; Kim, S.; Takano, T.; Yun, S.-J.; Son, Y. Contributing to sustainability education of East Asian University students through a field trip experience: A social-ecological perspective. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winks, L. Discomfort in the field—The performance of nonhuman nature in fieldwork in South Devon. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 49, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Gray, T.; Truong, S.; Brymer, E.; Passy, R.; Ho, S.; Sahlberg, P.; Ward, K.; Bentsen, P.; Curry, C. Getting out of the classroom and into nature: A systematic review of nature-specific outdoor learning on school children’s learning and development. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 877058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaigeorgiou, G.; Malandrakis, G.; Tsolopani, C. Learning with Drones: Flying windows for classroom virtual field trips. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 17th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Timisoara, Romania, 3–7 July 2017; pp. 338–342. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, B.; Sun, Y.; Li, L. Advances, Hotspots, and Trends in Outdoor Education Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeronen, E.; Palmberg, I.; Yli-Panula, E. Teaching methods in biology education and sustainability education including outdoor education for promoting sustainability—A literature review. Educ. Sci. 2016, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Panula, E.; Jeronen, E.; Lemmetty, P. Teaching and learning methods in geography promoting sustainability. Educ. Sci. 2019, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadova, A. Integrating Japanese local government and communities into the educational curriculum on regional sustainability inside the UNESCO’s biosphere reserves and geoparks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderhan-Opel, J.; Bogner, F.X. Cannot see the forest for the trees? Comparing learning outcomes of a field trip vs. a classroom approach. Forests 2021, 12, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.; Mulyadi, D.; Hananto, A.L.; Nor Muhamad, N.H.; Mat Teh, K.S.; Don, A.G. Empowering corporate social responsibility (CSR): Insights from service learning. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 875–894. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A. The place of experience and the experience of place: Intersections between sustainability education and outdoor learning. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 29, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stonehouse, P. Sustainable adventure? The necessary “transitioning” of outdoor adventure education. J. Sustain. Educ. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, M.; Pitt, H.; Marsden, T.; Mehmood, A.; Mathijs, E. Experiential approaches to sustainability education: Towards learning landscapes. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, I.C.; Carreira, F.C.; Aguiar, A.C.P.D.; Monzoni, M.P. Increasing knowledge of food deserts in Brazil: The contributions of an interactive and digital mosaic produced in the context of an integrated education for sustainability program. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.R.; Capps, T.M. Synergy of the (campus) commons: Integrating campus-based team projects in an introductory sustainability course. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, T.S.; Potter, T.G.; Curthoys, L.P.; Dyment, J.E.; Cuthbertson, B. A call for sustainability education in post-secondary outdoor recreation programs. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2005, 6, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hauk, M.; Williams, D.; Skelton, J.B.; Kelley, S.; Gerofsky, S.; Lagerwey, C. Learning gardens for all: Diversity and inclusion. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. Soc. Cult. Context 2018, 13, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leininger-Frézal, C.; Sprenger, S. Virtual field trips in binational collaborative teacher training: Opportunities and challenges in the context of education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaarslan Semiz, G.; Teksöz, G. Developing the systems thinking skills of pre-service science teachers through an outdoor ESD course. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2020, 20, 337–356. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, P.; Kirk, G. Sustainability education in Scotland: The impact of national and international initiatives on teacher education and outdoor education. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2006, 30, 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.; Shreck, A.; Buchmann, N. Tackling food system challenges through experiential education: Criteria for optimal course design. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2018, 27, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, K.; Tal, T. Education for sustainability in higher education: A multiple-case study of three courses. J. Biol. Educ. 2013, 47, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascopé, M.; Perasso, P.; Reiss, K. Systematic review of education for sustainable development at an early stage: Cornerstones and pedagogical approaches for teacher professional development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateskan, A.; Lane, J.F. Assessing teachers’ systems thinking skills during a professional development program in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4348–4356. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, R.; Cutting, R. ‘Low-impact communities’ and their value to experiential Education for Sustainability in higher education. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2014, 14, 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, W. Creating sustainable societies: Developing emerging professionals through transforming current mindsets. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2017, 39, 286–302. [Google Scholar]

- Zelenika, I.; Moreau, T.; Lane, O.; Zhao, J. Sustainability education in a botanical garden promotes environmental knowledge, attitudes and willingness to act. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1581–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Demssie, Y.N.; Biemans, H.J.; Wesselink, R.; Mulder, M. Fostering students’ systems thinking competence for sustainability by using multiple real-world learning approaches. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburuzabala, P.; Culcasi, I.; Cerrillo, R. Service-Learning and Digital Empowerment: The Potential for the Digital Education Transition in Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duram, L.A.; Klein, S.K. University food gardens: A unifying place for higher education sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 9, 282–302. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, L.-A.; Skarstein, T.H. Species learning and biodiversity in early childhood teacher education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, P.; Wezel, A.; Veromann, E.; Strassner, C.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Kahl, J.; Bügel, S.; Briz, T.; Kazimierczak, R.; Brives, H. Students’ knowledge and expectations about sustainable food systems in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, L.-A.; Skarstein, T.H.; Skarstein, F. The Mission of early childhood education in the Anthropocene. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, N.; Bungay, H.; Dadswell, A. Sustainable Outdoor Education: Organisations Connecting Children and Young People with Nature through the Arts. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandvliet, D.; Leddy, S.; Inver, C.; Elderton, V.; Townrow, B.; York, L. Approaches to Bio-Cultural Diversity in British Columbia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, H. Thematic analysis: Transformative sustainability education. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, P.L.; Selin, S.; Cerveny, L.; Bricker, K. Outdoor recreation, nature-based tourism, and sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aasar, M.; Shafik, Z.; Abou-Bakr, D. Outdoor learning environment as a teaching tool for integrating education for sustainable development in kindergarten, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausselet, N.; Zosso, I. Outdoor and sustainability education: How to link and implement them in teacher education? An empirical perspective. In Competences in Education for Sustainable Development: Critical Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Meadows, M.E.; Duan, Y.; Guo, F. How does the geography curriculum contribute to education for sustainable development? Lessons from China and the USA. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikly, L. Education for sustainable development in Africa: A critique of regional agendas. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmen, K.B.; Iversen, E. A scoping review of research on school-based outdoor education in the Nordic countries. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2023, 23, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | The study area is from 2005 to 2024 |

| The data extracted align with the current study’s focus and research questions | |

| Full text available in English | |

| Exclusion criteria | Without OE used |

| Irrelevant to ESD | |

| Written in other languages | |

| Book chapter |

| ID | Reference | Year | Article Type | Target Group | OESD Topics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID1 | [16] | 2017 | Qualitative research | Teachers | Teacher Training and Pedagogical Approaches |

| ID2 | [11] | 2020 | Quantitative research | Students | Community Engagement and High School Curriculum |

| ID3 | [39] | 2022 | Qualitative research | Teachers | Digital Transformation and Teacher Training and Intercultural Learning |

| ID4 | [40] | 2019 | Theoretical research | Teachers | Educational Practice and Development of Systems Thinking Skills |

| ID5 | [41] | 2016 | Theoretical research | Teachers | Education Policy and Practice and Teacher Training and Environment and Sustainability |

| ID6 | [33] | 2019 | Theoretical research | Students | Educational Practice and Learning Landscapes and Student-Centered |

| ID7 | [24] | 2017 | Quantitative research | Students | Technology Integration and Virtual Field Trips and Educational Innovation |

| ID8 | [42] | 2018 | Action research | Students and Learning Environment | Interdisciplinary Learning and Experiential Education and Sustainable Food Systems |

| ID9 | [26] | 2017 | Quantitative research | Students and Teachers | Biology Education and Environmental Awareness |

| ID10 | [43] | 2013 | Action research | Students and Learning Environment | Learning Outcomes and Environmental Education |

| ID11 | [8] | 2020 | Action research | Students and Learning Environment | Place-based Education and Interdisciplinary Learning |

| ID12 | [44] | 2019 | Theoretical research | Teachers and Students | Early Childhood Education and Teacher Professional Development |

| ID13 | [22] | 2018 | Qualitative research | Students and Learning Environment | Environmental Experience and Educational Transformation |

| ID14 | [45] | 2017 | Action research | Teachers and Learning Environment | Teacher Professional Development and Systems Thinking and Educational Sustainable Practices |

| ID15 | [7] | 2020 | Theoretical research | Environmental education and ESD | Sustainability Values and Global Citizenship Education |

| ID16 | [9] | 2014 | Quantitative research | Teachers | Teacher Professional Development and Environmental Awareness Enhancement and Practice-Oriented Teaching |

| ID17 | [29] | 2021 | Quantitative research | Students | Environmental Knowledge Acquisition and Comparative Education Methods |

| ID18 | [19] | 2018 | Quantitative research | Students | Learning Outcomes and Environmental Values |

| ID19 | [6] | 2014 | Qualitative research | Learning Environment | Education Policy Evolution and Outdoor Education Practices and Environmental Education Challenges |

| ID20 | [46] | 2014 | Qualitative research | Students | Community Engagement and Sustainability Practices |

| ID21 | [20] | 2012 | Theoretical research | Learning Environment | Outdoor Learning Experiences and Environmental Philosophy |

| ID22 | [31] | 2013 | Theoretical research | Teachers and Learning Environment | Outdoor Learning and Place-based Response |

| ID23 | [37] | 2018 | Action research | Students and Learning Environment | Multicultural Education and Experiential Learning |

| ID24 | [36] | 2005 | Theoretical research | Teachers and Students | Outdoor Recreation Practices and Curriculum Integration and Social Justice and Inclusivity |

| ID25 | [47] | 2017 | Action research | Students | Educator Training and Student Development and Interdisciplinary Integration |

| ID26 | [21] | 2016 | Quantitative research | Students | Educational Experience and Cross-cultural Communication |

| ID27 | [48] | 2018 | Quantitative research | Students and Learning Environment | Environmental Knowledge Enhancement and Behavioral Intentions and Field Learning Experiences |

| ID28 | [49] | 2023 | Action research | Students | Field Learning and Cultivation of Systems Thinking Skills |

| ID29 | [28] | 2021 | Quantitative research | Students | Educational Integration and Community Engagement and Regional Sustainability and Interdisciplinary Learning |

| ID30 | [50] | 2024 | Qualitative research | Teachers and Students | Service Learning and Digital Empowerment and Educational Transformation |

| ID31 | [35] | 2020 | Action research | Students and Learning Environment | Campus Engagement and Interdisciplinary Education |

| ID32 | [51] | 2015 | Action research | Teachers and Students and Learning Environment | Practice Learning and Community Engagement |

| ID33 | [34] | 2018 | Action research | Students | Digital Education and Interdisciplinary Learning |

| ID34 | [27] | 2019 | Theoretical research | Teachers and Students and Learning Environment | Educational Methods and Geographical Awareness |

| ID35 | [52] | 2020 | Quantitative research | Students and Learning Environment | Educational Methods and Biodiversity |

| ID36 | [53] | 2019 | Quantitative research | Students | Educational Methods and Interdisciplinary Learning |

| ID37 | [54] | 2020 | Theoretical research | Teachers and Students and Learning Environment | Environmental Awareness and Children’s Agency and Sustainable Development Practices |

| ID38 | [55] | 2023 | Action research | Teachers and Students | Artistic Practice and Mental Health and Environmental Sustainability |

| ID39 | [56] | 2023 | Action research | Teachers and Students and Learning Environment | Environmental Education and Indigenous Education and Place-based Education |

| ID40 | [30] | 2018 | Theoretical research | Students | Corporate Social Responsibility and Service Learning and Community Engagement |

| Discipline Classification | ID | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Geography | ID3, ID5, ID7, ID13, ID16, ID19, ID22, ID24, ID28, ID29, ID34 | 11 |

| Chemistry | ID16, ID25 | 2 |

| Biology | ID7, ID9, ID13, ID16, ID19, ID24, ID25, ID29, ID35 | 9 |

| Science | ID1, ID12, ID14, ID23, ID25 | 5 |

| Interdisciplinary course | ID2, ID5, ID8, ID9, ID11, ID12, ID14, ID15, ID16, ID18, ID22, ID25, ID26, ID27, ID28, ID29, ID30, ID31, ID32, ID33, ID34, ID36, ID37, ID39 | 24 |

| Teaching Method | ID | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Place-based teaching | ID1, ID6, ID11, ID14, ID21, ID31, ID32, ID34, ID39 | 9 |

| Problem-based learning | ID6, ID9, ID12, ID20, ID31, ID34 | 6 |

| Phenomenon-based teaching | ID1 | 1 |

| Inquiry-based learning | ID1, ID9, ID12, ID16, ID34 | 5 |

| Project-based learning | ID6, ID9, ID12, ID15, ID20, ID31 | 6 |

| Collaborative learning | ID2, ID8, ID9, ID28, ID34, ID37 | 6 |

| Mobile learning | ID28, ID36 | 2 |

| Paper-and-pencil learning | ID28 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, R.; Mou, S. Outdoor Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083338

Hu R, Mou S. Outdoor Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083338

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Rong, and Shuhang Mou. 2025. "Outdoor Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083338

APA StyleHu, R., & Mou, S. (2025). Outdoor Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 17(8), 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083338