Are You Truly Green? The Impact of Self-Quantification on the Sincerity of Consumers’ Green Behaviors and Sustained Willingness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Self-Quantification and Green Consumption

2.2. Sincerity of Green Behaviors

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

4. Pilot Experiment

4.1. Interview Design

4.2. Interview Results

4.3. Design of Pilot Experiment

4.4. Results of of Pilot Experiment

5. Experiment 1: Promoting Goal-Oriented Green Energy Value Tracking

5.1. Design of Experiment 1

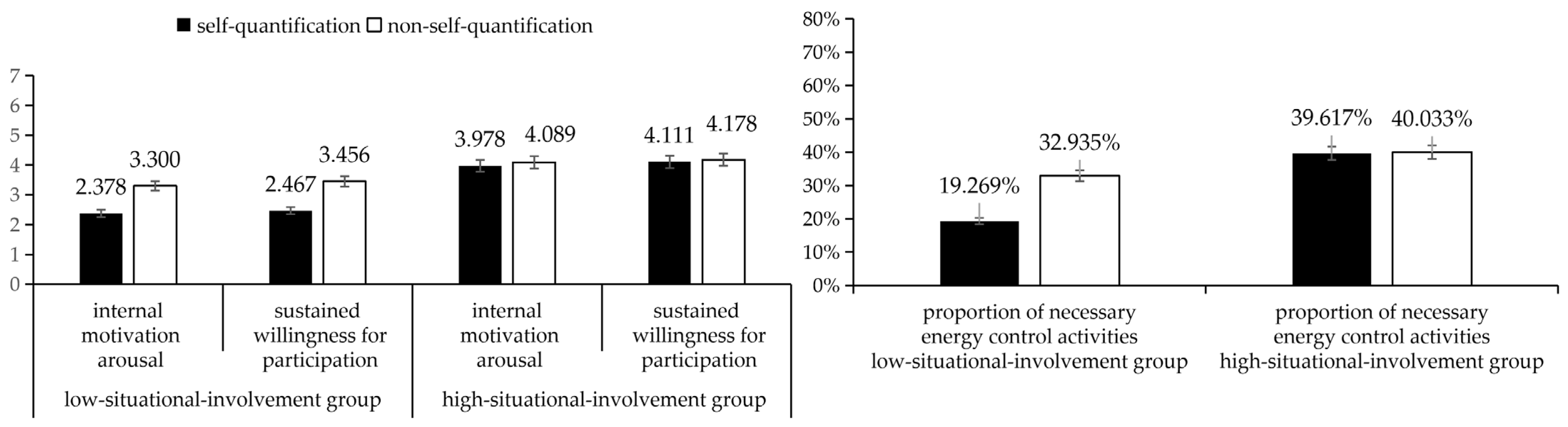

5.2. Results of Experiment 1

6. Experiment 2: Defensive Goal-Oriented Energy Consumption Tracking

6.1. Design of Experiment 2

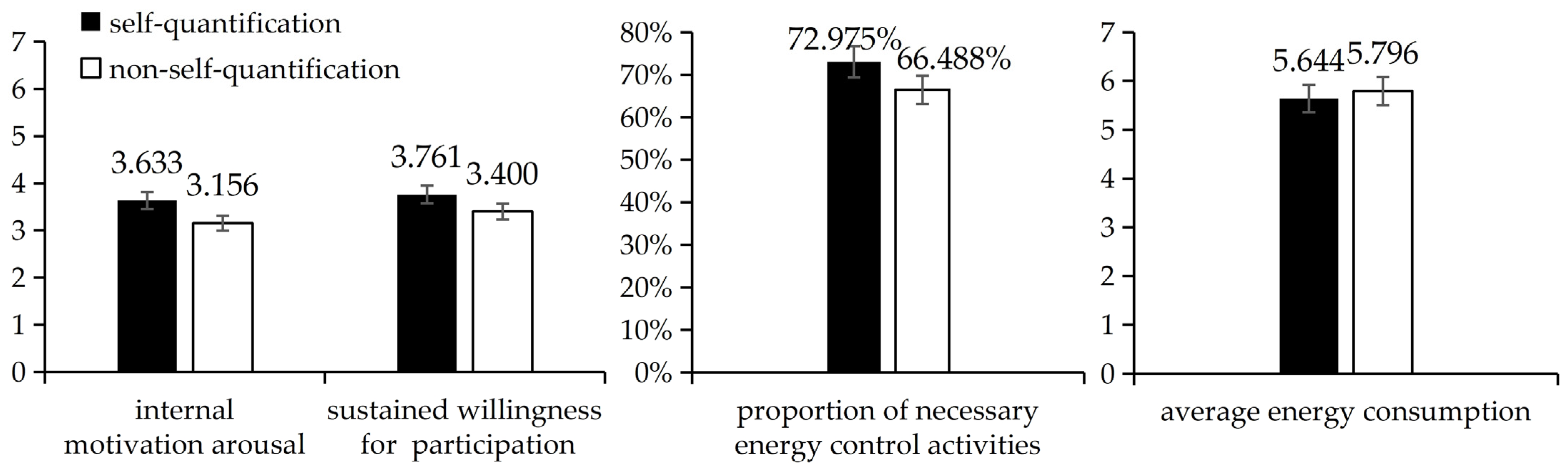

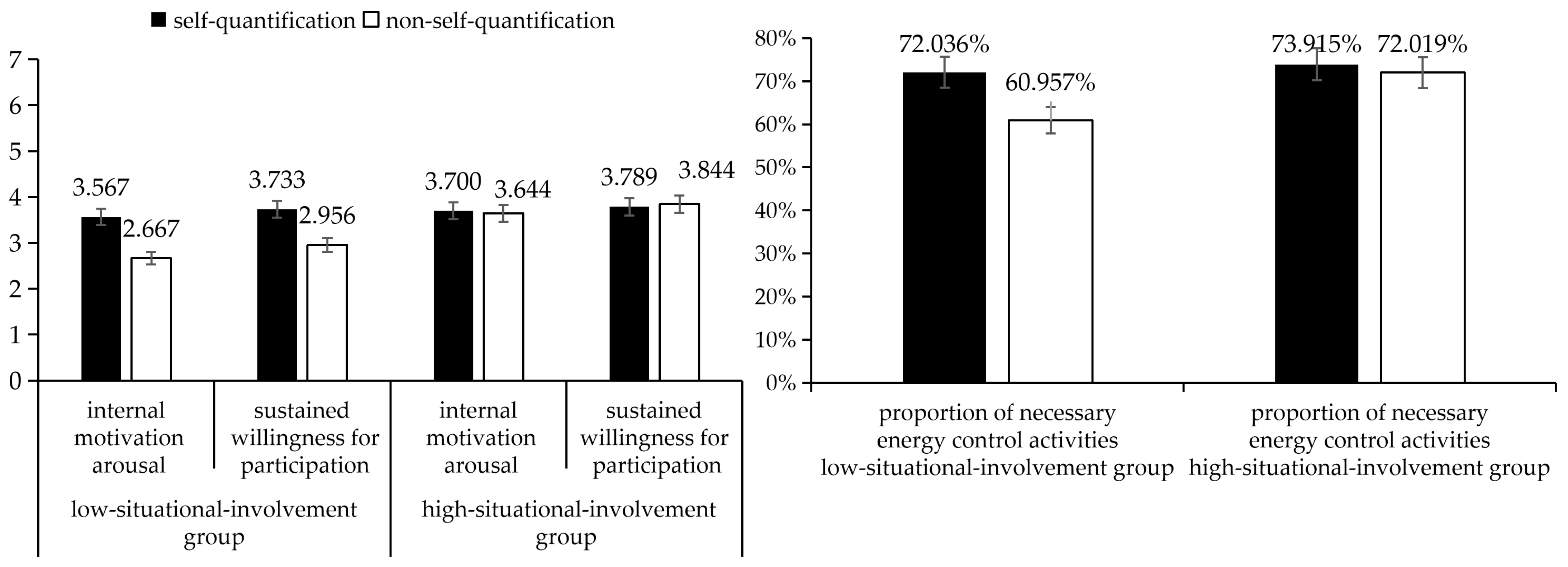

6.2. Results of Experiment 2

7. Discussions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Managerial Implications

7.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rapp, A.; Cena, F.; Marcengo, A. Editorial of the special issue on quantified self and personal informatics. Computers 2018, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, D. The impact of self-quantification on consumers’ participation in green consumption activities and behavioral decision-making. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalegno, C.; Candelo, E.; Santoro, G. Exploring the antecedents of green and sustainable purchase behaviour: A comparison among different generations. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, R.R.; Islam, A.F.; Sujauddin, M. More than just a business ploy? Greenwashing as a barrier to circular economy and sustainable development: A case study-based critical review. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman, M. Is it sustainable consumption or performative environmentalism? Consum. Soc. 2022, 1, 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, M.; Gu, M.; Zhang, B. How online pro-environmental games affect users’ pro-environmental behavioural intentions?—Insights from Ant Forest. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 368, 122182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yan, X. How could peers in online health community help improve health behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Lasarov, W.; Reimers, H.; Trabandt, M. Carbon footprint tracking apps. Does feedback help reduce carbon emissions? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why do consumers make green purchase decisions? Insights from a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Unsustainable consumption: Basic causes and implications for policy. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. Sustainable consumption: A theoretical and environmental policy perspective. In The Ecological Modernisation Reader, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, G. Research on the impact mechanism of self-quantification on consumers’ green behavioral innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Hassan, L.; Dias, A. Gamification, quantified-self or social networking? Matching users’ goals with motivational technology. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2018, 28, 35–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H. Quantified or nonquantified: How quantification affects consumers’ motivation in goal pursuit. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Encycl. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2016, 10, 978–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckenstein, M.; Pantzar, M. Beyond the quantified self: Thematic exploration of a dataistic paradigm. New. Media Soc. 2017, 19, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, R. Interrupt and carry-on: Research on the mechanism of quantified-self construction influencing the green transformation of lifestyles. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2022, 38, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. Data’s intimacy: Machinic sensibility and the quantified self. Communication+1 2016, 5, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J. Environmentally sustainable food consumption: A review and research agenda from a goal-directed perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Feigenbaum, J. Bounded rationality, lifecycle consumption, and social security. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 146, 65–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pan, D. In the face of negative data, the effects of goal type and feedback type on the willingness to continue to participate quantified-self. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2020, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhuang, S.; Li, Z.; Gao, J. Creating a sincere sustainable brand: The application of Aristotle’s rhetorical theory to green brand storytelling. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 897281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyahia, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Elshaer, I.; Mohammad, A.A.A. Greenwashing behavior in hotels industry: The role of green transparency and green authenticity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, W.; Xin, X.; Wang, J. Strategies for assessing health information credibility among older social media users in China: A qualitative study. Health Commun. 2024, 39, 2767–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajid, M.; Zakkariya, K.A.; Suki, N.M.; Islam, J.U. When going green goes wrong: The effects of greenwashing on brand avoidance and negative word-of-mouth. J. Retail. Consum Serv. 2024, 78, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, J. The hidden cost of personal quantification. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 42, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler-Hill, V.; Shackelford, T.K.; Hangen, E.J.; Elliot, A.J. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 2416–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekler, E.D.; Brühlmann, F.; Tuch, A.N. Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Liu, Y. Structure and effects of motivation: From the perspective of the motivation continuum. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 30, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.L.; Li, G.C.; Xiao, H.W.; Wang, K.; Feng, J.D. The negative spillover effect of gamification on green consumption behavior and its coping strategy. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2023, 26, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; Zhang, C. The influence of self-quantification on individual’s participation performance and behavioral decision-making in physical fitness activities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piligrimienė, Ž.; Žukauskaitė, A.; Korzilius, H.; Banytė, J.; Dovalienė, A. Internal and external determinants of consumer engagement in sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret, J.K.; Udalov, V.; Fabisch, N. Motivations behind individuals’ energy efficiency investments and daily energy-saving behavior: The case of China. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2022, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandhu, D.; Mohan, M.M.; Nittala, N.A.P.; Jadhav, P.; Bhadauria, A.; Saxena, K.K. Theories of motivation: A comprehensive analysis of human behavior drivers. Acta Psychol. 2024, 244, 104177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.G.; Gu, L.P. Quantified self: Qualitative research on the relinquishment of privacy in the digital society. J. Soochow Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2024, 45, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grève, Z.D.; Bottieau, J.; Vangulick, D.; Wautier, A.; Dapoz, P.D.; Arrigo, A.; Toubeau, J.F.; Vallée, F. Machine learning techniques for improving self-consumption in renewable energy communities. Energies 2020, 13, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leso, B.H.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; ten Caten, C.S. The influence of situational involvement on employees’ intrinsic involvement during IS development. Bus. Inform. Syst. Eng. 2022, 64, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhate, S. One world, one environment, one vision: Are we close to achieving this? An exploratory study of consumer environmental behaviour across three countries. J. Consum. Behav. 2002, 2, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.F.; Yu, W.P.; Li, Y.X. An empirical study of the formation mechanism of consumers’ green purchase intention: Interaction between green advertising appeal and consumers’ self-construction. Contemp. Financ. Econ. 2017, 5, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A. The skeptical green consumer revisited: Testing the relationship between green consumerism and skepticism toward advertising. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrijsen, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Boncquet, M. Does motivation predict changes in academic achievement beyond intelligence and personality? A multitheoretical perspective. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 114, 772–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.H.; Gong, S.Y.; Yue, B.B. How do the corporate environmental actions promote consumer response?—A dual mediation model based on consumer corporate identification and green wash perception. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2019, 7, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Hyder, Z.; Imran, M.; Shafiq, K. Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13113–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuni, J.A.; Du, J. Sustainable consumption in Chinese cities: Green purchasing intentions of young adults based on the theory of consumption values. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Micevski, M.; Dlacic, J.; Zabkar, V. Being engaged is a good thing: Understanding sustainable consumption behavior among young adults. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, H.; Liu, H.; Su, C. Consumer responses to corporate environmental actions in China: An environmental legitimacy perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad Al-Sumaiti, A.; Ahmed, M.H.; Salama, M.M.A. Smart home activities: A literature review. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2014, 42, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, İ.; Horzum, M.B.; Randler, C. Adaptation of the short form of the intrinsic motivation inventory to Turkish. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Kahn, B. Cross-category effects of induced arousal and pleasure on the internet shopping experience. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A.; Schmuck, D. Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Biocca, F. Health experience model of personal informatics: The case of a quantified self. Comput. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalot, F.; Gollwitzer, P.M.; Quiamzade, A. Boosted by closure! Regulatory focus predicts motivation and task persistence in the aftermath of task-unrelated goal closure. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 52, 944–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.S.; Clayton, S.; Stern, P.C. How psychology can help limit climate change. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brendl, C.M.; Higgins, E.T. Principles of judging valence: What makes events positive or negative? Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 28, 95–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanken, I.; Van De Ven, N.; Zeelenberg, M. A meta-analytic review of moral licensing. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.; Fishbach, A. The small-area hypothesis: Effects of progress monitoring on goal adherence. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, B.; Homburg, C.; Wielgos, D.M. Wage inequality: Its impact on customer satisfaction and firm performance. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Activity Name | Green Energy Value per Instance | Activity Name | Green Energy Value per Instance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walking 5000 steps | 5 g | Using online payment for shopping once | 5 g |

| Using shared bike rides once | 5 g | Using online utility payment once | 5 g |

| Taking public transportation once | 5 g | Liking one user’s green profile | 5 g |

| Dining without disposable utensils once | 5 g | Learning one green living tip | 5 g |

| Recycling one plastic bottle | 10 g | Playing the energy rain mini-game once | 10 g |

| Recycling one packaging box | 10 g | Collecting energy from one user | 10 g |

| Recycling one old book | 15 g | Watering one user’s virtual tree | 15 g |

| Recycling one piece of old clothing | 30 g | Co-planting a virtual tree with one user | 30 g |

| Situational Involvement | Variable | Condition | Mean | Standard Deviation | T | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| Low Situational Involvement | Substantive Proportion | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 0.329 0.193 | 0.091 0.061 | 6.860 | 0.097 | 0.177 |

| Green Energy | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 414.000 829.333 | 112.045 166.680 | −11.327 | −488.732 | −341.934 | |

| Logarithm of Green Energy | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 5.988 6.699 | 0.286 0.216 | −10.877 | −0.842 | −0.580 | |

| Internal Motivation Arousal | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 3.300 2.378 | 0.837 0.731 | 4.546 | 0.516 | 1.328 | |

| Sustained Willingness | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 3.456 2.467 | 0.780 0.805 | 4.830 | 0.579 | 1.399 | |

| High Situational Involvement | Substantive Proportion | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 0.400 0.396 | 0.069 0.060 | 0.248 | −0.029 | 0.038 |

| Green Energy | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 503.167 591.500 | 99.987 196.417 | −2.195 | −168.882 | −7.785 | |

| Logarithm of Green Energy | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 6.202 6.334 | 0.195 0.314 | −1.944 | −0.266 | 0.004 | |

| Internal Motivation Arousal | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 4.089 3.978 | 0.625 0.612 | 0.696 | −0.209 | 0.431 | |

| Sustained Willingness | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 4.178 4.111 | 0.630 0.657 | 0.401 | −0.266 | 0.399 | |

| Activity Name | Energy Consumption per Instance | Activity Name | Energy Consumption per Instance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brushing one’s teeth and washing one’s face once | 5 g | Watering one pot of plants | 5 g |

| Washing one’s hands or fruits once | 5 g | Using electric mosquito repellent liquid for 2 h | 5 g |

| Charging a mobile phone once | 10 g | Using an electric fan for 2 h | 10 g |

| Using fluorescent lights for 2 h | 10 g | Using a hair dryer for 10 min | 10 g |

| Using a computer for 2 h | 10 g | Riding an electric bike on campus once | 10 g |

| Flushing the toilet once | 15 g | Mopping the dormitory floor once | 15 g |

| Handwashing one piece of clothing | 15 g | Using a washing machine for 15 min | 15 g |

| Taking a shower for 15 min | 30 g | Using air conditioning for 2 h | 30 g |

| Situational Involvement | Variable | Condition | Mean | Standard Deviation | T | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| Low Situational Involvement | Necessary Proportion | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 0.610 0.720 | 0.081 0.093 | −4.925 | −0.156 | −0.066 |

| Energy Consumption | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 396.333 300.000 | 51.744 48.778 | 7.420 | 70.345 | 122.322 | |

| Logarithm of Energy Consumption | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 5.973 5.691 | 0.138 0.162 | 7.272 | 0.205 | 0.360 | |

| Internal Motivation Arousal | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 2.667 3.567 | 0.594 0.685 | −5.440 | −1.231 | −0.569 | |

| Sustained Willingness | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 2.956 3.733 | 0.624 0.669 | −4.658 | −1.112 | −0.444 | |

| High Situational Involvement | Necessary Proportion | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 0.720 0.739 | 0.080 0.092 | −0.851 | −0.064 | 0.026 |

| Energy Consumption | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 279.500 272.167 | 45.964 40.379 | 0.657 | −15.026 | 29.693 | |

| Logarithm of Energy Consumption | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 5.619 5.596 | 0.173 0.148 | 0.560 | −0.060 | 0.107 | |

| Internal Motivation Arousal | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 3.644 3.700 | 0.631 0.818 | −0.295 | −0.433 | 0.322 | |

| Sustained Willingness | Non-Self-Quantification Self-Quantification | 3.844 3.789 | 0.531 0.776 | 0.324 | −0.288 | 0.399 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhang, H.; Tu, P. Are You Truly Green? The Impact of Self-Quantification on the Sincerity of Consumers’ Green Behaviors and Sustained Willingness. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093764

Zhang Y, Hu G, Zhang H, Tu P. Are You Truly Green? The Impact of Self-Quantification on the Sincerity of Consumers’ Green Behaviors and Sustained Willingness. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093764

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yudong, Gaojun Hu, Huilong Zhang, and Ping Tu. 2025. "Are You Truly Green? The Impact of Self-Quantification on the Sincerity of Consumers’ Green Behaviors and Sustained Willingness" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093764

APA StyleZhang, Y., Hu, G., Zhang, H., & Tu, P. (2025). Are You Truly Green? The Impact of Self-Quantification on the Sincerity of Consumers’ Green Behaviors and Sustained Willingness. Sustainability, 17(9), 3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093764