Abstract

This article examines Chile’s post-disaster data collection and management, focusing on state legibility tools for identifying housing damage and victims’ needs. Drawing on James Scott’s theory of legibility, we explore how standardized categories are used in disaster management. Through documentary analysis and key informant interviews, we assess the strengths and limitations of the forms used for allocating aid. The 2022 Viña del Mar wildland–urban interface fire serves as a case study to illustrate how classification systems determine victim status, influencing government resource allocation. We show that Chile has made significant progress in loss and needs assessment after disasters but gaps remain in data integration and intersectoral collaboration. Three main themes emerge from the analysis: actor coordination, social legitimacy, and administrative blindness. We conclude that while legibility tools facilitate state action, they also obscure the complexities of disasters. This case study provides further evidence that disparities in aid distribution hinder recovery efforts and that for many victims, disaster aid has been both insufficient and delayed. We provide recommendations to address these challenges and strengthen disaster risk management policies in Chile and other countries facing similar challenges.

1. Introduction

Despite significant global efforts in disaster risk reduction (DRR), the frequency and intensity of disasters continue to rise, primarily due to the ongoing climate crisis [1]. Today, weather-related disasters tend to result in fewer deaths but economic losses are increasing due to rapid urbanization and the densification of areas where populations and infrastructure remain exposed and vulnerable [2,3,4]. This presents major challenges for states, which must repeatedly provide timely and effective responses to meet the diverse needs of victims.

In this context, damage and loss assessment has been considered essential for organizing aid, guiding reconstruction, and ensuring the efficient use of public resources [3,5,6,7,8,9]. The quality and consistency of the data collected also affect countries’ ability to develop sustainable disaster risk reduction (DRR) policies to mitigate future events [8]. This is why the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) urged countries to adopt and implement reliable methods and tools to assess disaster impacts using a multidimensional approach [3]. Since then, most states have developed post-disaster information strategies. However, the lack of standardized forms and shared criteria has been regarded as a problem, hindering comparative analysis across countries [8,9,10,11]. Many states also struggle to establish centralized databases, leading to duplicated efforts, response gaps, and obstacles in strategic recovery planning that link immediate actions to long-term goals [6,8,9,12].

Following sociologist James Scott’s concept of “state legibility” [13,14], data collection and management can be understood as practices intended to simplify disaster response through predefined categories of observation. These categories make “the phenomenon at the center of the field of vision much more legible and, therefore, more susceptible to measurement, calculation, and manipulation” [14] (p. 11). By classifying reality, state officials can better organize and manage the problem at hand—in this case, disasters. However, legibility studies consistently show that reality is more complex than any label, especially when observing non-routine phenomena [13,14]. This means any attempt at legibility with predefined categories has blind spots [15,16,17,18]. Furthermore, far from being objective, categories used by any bureaucratic apparatus reflect specific political, legal, economic, and even academic regimes [16,19,20,21,22]. As such, they can significantly impact the success or failure of such policies.

Drawing on this framework, this article explores the role of state legibility tools in disaster management in Chile, focusing on how standardized data collection about disasters’ impacts influences aid allocation and reconstruction plans. Chile provides a compelling case study due to its high frequency of disasters linked to geological and climatic hazards [23,24]. Between 2014 and 2024, at least twenty-nine extreme events caused significant damage across various regions of the country, including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, wildfires, floods, and landslides, among others [25]. Given that some of these events affected multiple communities and that reconstruction processes typically take 4–5 years to reach administrative closure—usually, once 95% of the plan has been executed—there have been at least six formally active housing reconstruction processes at any given time between 2011 and 2023.

Additionally, Chile has a long history of legibility tools and methodologies for assessing disaster loss and needs, which explains the relative strength of its system compared to other developing countries facing similar challenges. Even during colonial times, Chilean authorities sought to document earthquake damage and report it to the King of Spain. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the state developed different institutional capacities to address consecutive earthquakes threatening the country’s stability, including damage assessment studies [26]. However, challenges have become more complex during the current century since the climate crisis has brought new hazards to the forefront of DRM.

Chile’s current tools to assess disaster damage date back to 2002, when “DEDO$” (Sistema de Evaluación de Daños y Necesidades) was incorporated into the National Plan of Civil Protection (Plan Nacional de Protección Civil) [27]. Unlike information systems such as the Damage Assessment and Needs Analysis (DANA) methodology developed by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in 2008 or the Early Estimation System (EES) used since 1966 in Japan, the Chilean system provides not only a general assessment of the impact on different sectors but also a survey of the affected households. This is common in Latin America, where Peru, Honduras, and Mexico have implemented national registries of victims to help distribute aid. However, in most countries, data-gathering and information systems depend on national emergency offices. In contrast, in Chile, these activities fall under the agency responsible for all social services, which is considered a strength of the design as it links disaster response with social policies [28].

Still, challenges remain, particularly in standardizing criteria for providing aid and reconstruction funds across sectors and even for different events. Furthermore, there has been no formal evaluation of the system, leaving actors uncertain whether it achieves its intended goals [29]. This article aims to uncover these challenges while learning from the Chilean system’s strengths. Ultimately, the goal is to draw insights from this case about legibility tools and their crucial role in post-disaster public policy more broadly.

This article is structured as follows. After a brief description of the methods used, we trace the history of disaster legibility tools and the administrative rationality behind them. We then assess the strengths and limitations of these instruments for public policy based on the perspectives of key actors in the Chilean DRM ecosystem. Additionally, the 2022 wildland–urban interface fire in Viña del Mar is explored to show how legibility tools work in practice. Finally, the Section 5 presents recommendations to strengthen disaster risk management in Chile and beyond. In the Section 6, we reflect on state legibility and disaster risk management more broadly.

2. Materials and Methods

This article uses a qualitative approach that combines document analysis and key informant interviews. For documentary evidence, we collected and analyzed Chile’s regulations and policies for DRM, together with the forms, surveys, and sheets associated with them (see complete list in Appendix A). Analyzing these documents is crucial for identifying the categories that allow the state to observe victims and distribute aid, as well as for reconstructing the normative framework in which legibility tools operate.

A second set of qualitative data was obtained through 22 interviews with 18 key informants in eight public institutions and agencies critical for disaster recovery (Table A1 in Appendix B). We used the Map of Stakeholders for Comprehensive Recovery [30] developed in a participatory workshop at the Chilean Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction (PNRRD) to select institutions. The selection of interviewers in each one was not probabilistic since we sought to interview “information-rich cases”, which implies intentionally selecting the respondents in a position to have greater insider knowledge about the topic at hand [31]. Overall, we covered all the institutions identified as relevant, selecting one to three informants for each one.

The interviews were conducted in three rounds: the first during the period September–October 2022, the second in May–June 2023, and the third in March–April 2024. Some respondents were interviewed in more than one round (Table A1 in Appendix B). Qualitative semi-structured questionnaires were used, with predefined questions that allowed respondents to speak freely. This approach generates comparable answers while giving respondents the flexibility to add information they find important [32]. Following De Souza’s study of state legibility in the context of poverty [16], we inquired about forms and surveys used for observing disasters and the rationale behind them (see the questionnaire in Supplementary Materials Section S1). Interviews were conducted by the authors along with undergraduate students as part of a qualitative methods capstone. Most (14) were held virtually, with eight conducted in person, averaging 45 min each. Virtual interviews are considered a strength of the design, enabling access to participants nationwide without compromising data quality. Following the ethical guidelines for research with human subjects, an informed consent form was used to ensure confidentiality.

Interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis, identifying topics that shed light on the issue of state legibility and disaster management. Three key themes emerged: actor coordination, social legitimacy, and administrative blindness. The analysis is organized around these themes.

To illustrate how legibility tools sort victims in practice, we incorporate a case study: the urban–wildland fire of 22 December 2022 in Viña del Mar. The case is developed using administrative data from Chile’s Ministry of Social Development and Family (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, MDSF) and Ministry of Housing and Urbanism (Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo, MINVU), obtained through three requests to the Chilean National Council for Transparency (Consejo Nacional para la Transparencia, CPLT). Following CPLT regulations (Law No. 20.285), these datasets do not include personal data on victims.

3. Analysis and Results

This section combines documentary analysis and the information gathered via interviews to discuss our main findings. First, we present a brief genealogy of legibility tools used to address the impact of disasters in Chile. This sub-section provides a clearer understanding of legibility tools’ role in disaster response, recovery, and reconstruction in Chile. The following three subsections discuss the main themes from the interviews: actor coordination, social legitimacy, and administrative blindness.

Only a limited number of direct quotes from interviews are presented in the text to prioritize aggregated conclusions and keep the article concise (see Table A2 in Appendix B).

3.1. Legibility Instruments: Origin and Evolution

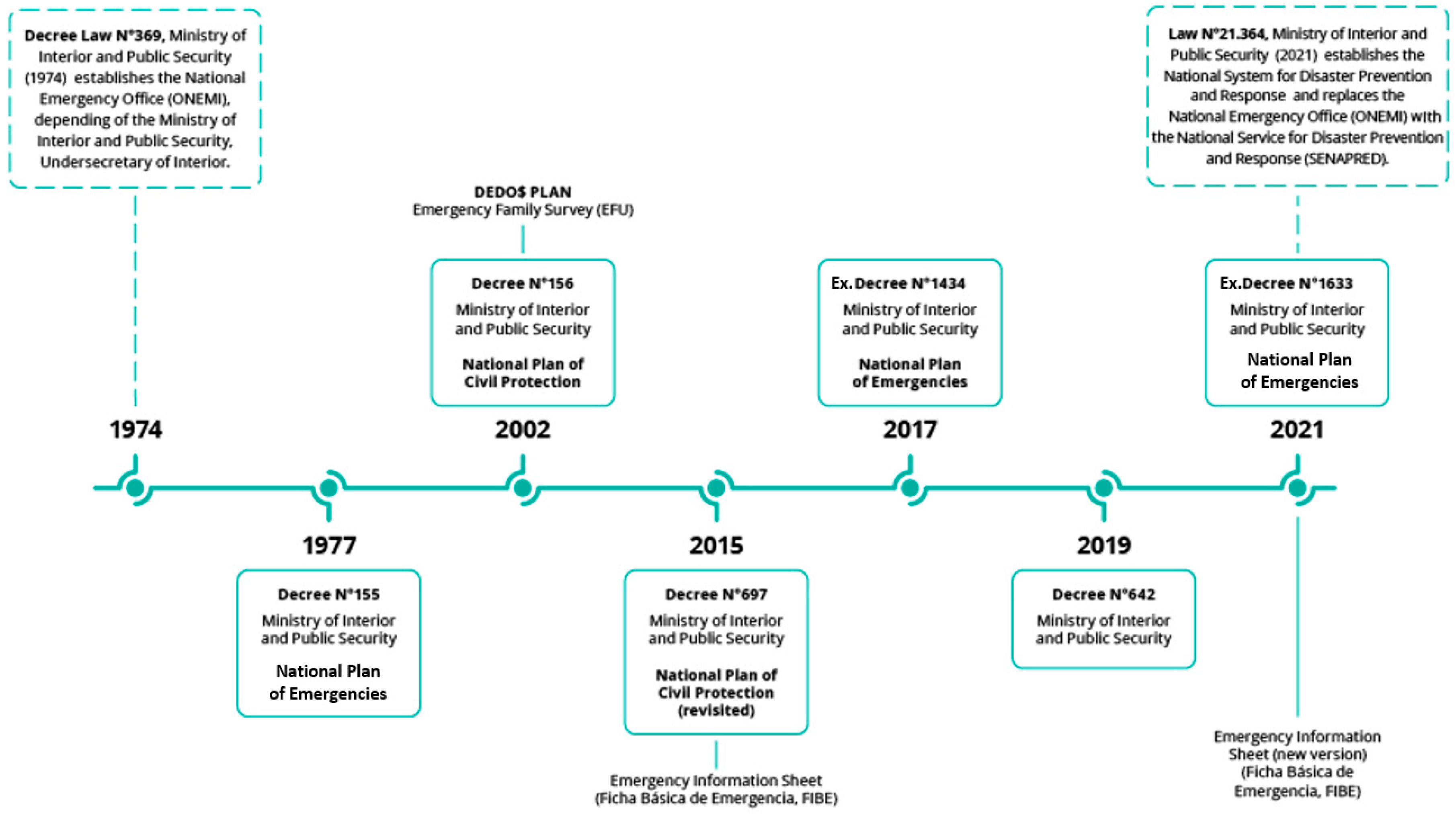

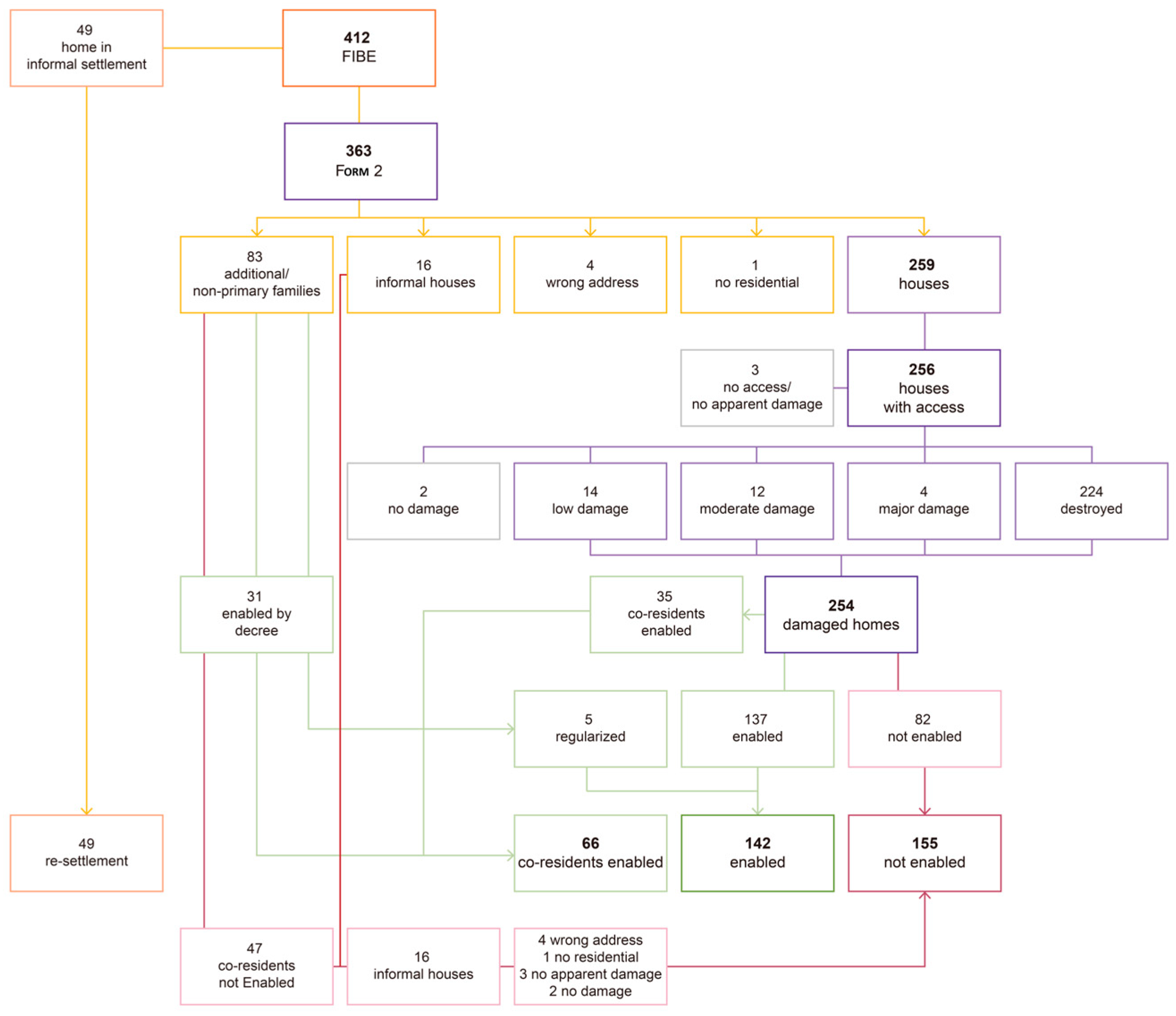

The idea that for something to be governed, it must first be made visible, quantifiable, and standardized is often summarized in the mantra “what gets measured gets managed” (often attributed to Lord Kelvin (1824–1907), a British physicist). This principle drives state legibility projects, where complex and often new social realities must be translated into administrative categories and bureaucratic forms. This article focuses on how the Chilean state observes and classifies affected households, damnificados in Spanish. As shown in Figure 1, current DRM institutions in Chile found their origins in 1974 when the first National Emergency Office (ONEMI) was created [33], followed by the first National Plan of Emergencies in 1977 [34]. However, the institutionalization of forms and surveys to account for disaster damage started in 2002, when the National Plan of Civil Protection (Plan de Protección Civil) [27] replaced the original plan.

Figure 1.

Key regulatory moments in the damage and needs assessment system in Chile. Source: the authors.

The new strategy aimed to address emerging DRM challenges in the country. One of its key innovations was creating a system to assess damage and needs, enabling authorities to better respond to emergencies and address recovery more effectively. Although the 2002 plan stemmed from international commitments Chile made during the United Nations’ International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (1990–1999), it did not adopt any internationally recognized methodology for post-disaster assessment. At the time, the most widely known method for post-disaster evaluation was DALA (Damage and Loss Assessment), developed by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (UNDP) after the 1972 Managua Earthquake [35]. However, this methodology focuses on estimating sectoral losses, not household-level impacts. In contrast, Chile’s plan established an Emergency Family Survey (Encuesta Única Familiar, hereafter EFU) as a pillar of the assessment system.

The methodology was labeled “DEDO$” (meaning Daños, Evaluación de Necesidades y Decisiones) and looked to “standardize the recording of emergency information throughout the country, managing simple documents, in a single format, that allows answering the fundamental questions that arise when a destructive event occurs at the local level” [36] (p. 31). To do so, DEDO$ includes several standardized reports: ALFA, DELTA, EDANIS, and REDES. Municipalities and Regional Governments use ALFA and DELTA reports to inform losses and general needs at the national level immediately. The Single Damage and Infrastructure Needs Assessment Report (EDANIS) and the Single Form for the Reception, Delivery, and Availability of Relief Elements (REDES) were designed to account for damages and losses in different economic sectors.

While previous attempts had been made to catalog the impact of disasters in Chile, forms were created ad hoc for each event and held no legal authority. In contrast, DEDO$ established “normalized documents” with predefined categories of observation, allowing the impact of a destructive event to be identified, organized, and classified systematically. These standardized documents are legally binding, meaning information sharing between different political–administrative levels has become mandatory. Also, any modifications to the forms must be enacted by decree (Figure 1), a written mandate issued by the relevant administrative authority, and then confirmed by the National Comptroller. .

The EFU is particularly relevant to understanding Chile’s legibility practices regarding disasters, as it was a pioneering attempt to identify a “target population” to receive state aid. EFU allowed for the identification of the losses and needs of each household, defined by Chilean law as “a person or group of persons, whether or not united by kinship, who share a common food budget” [37]). While EFU was not linked to any direct aid or benefits, it was established as “a legal requirement for the delivery of goods, services, subsidies and subsequent reconstruction of affected housing” [38].

However, the 2010 Chile earthquake and tsunami were a difficult test for the EFU. The stock of forms was insufficient, some questions were irrelevant to the specific event, there was no platform to keep records, and there was a lack of application protocols, among other issues [38]. This led to a revision of EFU, under the conviction that “it is necessary to have better state-of-the-art instruments that allow for more appropriate collection of relevant information to address emergencies” [39] (p. 1). Still, EFU continued to survey households until the end of 2015, when the National Plan of Civil Protection of 2002 was revisited.

By 2015, Sendai established the critical role of data collection, analysis, and dissemination for DRM. This led to the recognition of several methodologies, such as the PDNA (Post-Disaster Needs Assessment), developed by UNDP and the World Bank [40], and EDAN (Damage Assessment and Needs Analysis), published by USAID to replace DANA. Still, when the National Plan of Civil Protection was revisited, the Chilean state relied on its experience and practical needs to update the forms used for damage and needs assessment.

The new Basic Emergency Information Sheet (Ficha Básica de Emergencia, hereafter FIBE) was developed with a participatory multi-stakeholder methodology that included public officials from different institutions and considered all regions of the country. The result was a new information form and a system comprising an application guide, a formal operational instruction course, and a platform for registering the record. Additionally, the management of FIBE was officially established at the Under Secretariat of Social Services of the MDSF, not ONEMI. Apart from providing technical support, MDSF changed validation procedures and training, enhancing the role of data gathering in DRM.

Table 1 summarizes the elements considered in each instrument. We can see that FIBE not only accounts for housing damage but also looks to provide a comprehensive assessment of a disaster’s losses to inform different public sectors (see the form in Section S2 of the Supplementary Materials). In the words of one interviewee, “(…) one of the main functions of FIBE is to coordinate supply (of public services) with demand, unifying data for all sectors (…)” [Actor 6].

Table 1.

Summary of the categories considered in the EFU and FIBE.

Overall, the instruments established in Chile have enabled the state to identify and classify those affected by emergencies and disasters for over two decades. However, the fact that the documents are standardized by decree makes modifications difficult. Still, in 2017, a new National Plan of Emergencies replaced the former plan [41]. This plan maintained DEDO$ but, looking to improve state coordination, substituted the ALFA and DELTA report forms for new versions [41]. In 2019, a new instrument—the Basic Water Emergency Information Sheet (FIBEH)—was introduced to assess households in drought-affected areas [42], reflecting the system’s adaptation to emerging challenges. Finally, FIBE was modified in 2021, incorporating some questions relevant to the work of other sectors (e.g., health) and changing some procedures in the information system [43,44,45]. The form’s management was further streamlined, ensuring that all Chilean municipalities have stored physical forms and trained personnel certified by the MDSF to administer FIBEs. This enables municipalities to register disaster victims immediately as events unfold. Additionally, an “Emergency Social Information Unit (ISE)” was created to optimize data management [46], together with a platform for storing the collected information (SISE, Social Information System in Emergencies), making it accessible to any public office providing post-disaster assistance or targeted social services. The decree also established that FIBE had a two-fold objective: (a) to gather information on those affected in an effective, efficient, and comprehensive manner and (b) to improve coordination among institutions [43].

Recent institutional developments in Chile have redesigned the country’s DRM ecosystem, transforming ONEMI into the National Service of Disaster Prevention and Response (SENAPRED). However, the new 2021 DRM law did not change legibility instruments or the process of post-disaster data collection [47].

3.2. State Legibility and Actor Coordination

One of the main reasons states rely on standardized legibility instruments is that they facilitate coordination among various actors and enable communication through shared terminology and categories [13,14]. They provide a point of convergence for observing the disaster across all involved institutions. Furthermore, instruments like FIBE help reduce uncertainty, providing a common base for action. Even if some actors may critique how things are being classified, standardization allows for reliable expectations about how post-disaster public policies will work.

This is particularly important in Chile, where recovery and reconstruction processes are not governed by a single policy or regulation coordinating the different actors. The 2021 DRM law explicitly states that reconstruction-related activities are not subject to this law [47] (Article 3). This does not mean public reconstruction policies beyond emergency management are nonexistent but rather that they remain highly siloed in different sectors. In this context, legibility instruments play a crucial role in coordination, and FIBE was explicitly designed to fulfill this function.

Our analysis shows that FIBE is the cornerstone of Chile’s post-disaster information system. Today, “nothing happens without a FIBE” [Actor 6], which means that filling out the form is necessary to be “classified as disaster victim” [38] (p. 11). Additionally, institutions involved in recovery rely on the information provided by FIBE to activate sectoral disaster aid and reconstruction funds (in the case of MINVU). In this context, FIBE is pivotal in coordinating state actors for disaster response. Interviewees emphasized that FIBE has meant a vast improvement from the old EFU. The EFU was a pioneering but limited initiative in data collection after a disaster, primarily focused on counting affected households. In contrast, the FIBE is a “sophisticated data collection instrument, used across state institutions” [Actor 10]. It works to asses both material damage and the immediate needs of individuals, facilitating the organization of early relief and rehabilitation efforts and informing the development of recovery plans for different sectors.

The Undersecretariat of Social Services provides forms and an information system, coordinating data collection in collaboration with local municipalities. Actors across different sectors highly value this, as it allows them to rely on the MDSF for the initial damage and needs assessment, enabling them to focus on securing funds and organizing aid. The MDSF’s central role in data collection and processing ensures that the data are standardized and systematized. The information gathered through FIBE then serves as a basis for activating support or benefits not only from MDSF but also from other government entities such as MINVU, Chile’s National Health Fund (Fondo Nacional de Salud, FONASA), local governments, and the office of property registries, among others. Consequently, FIBE has become a strategic tool for observing and managing emergencies and a key artifact of coordination.

However, interviewees agree that the system still faces several challenges in using the information provided. One key issue is the lack of trust in the personnel trained by the MDSF to apply FIBE in certain territories. According to several interviewees, the quality of information varies according to the training, experience, and availability of human and material resources at the municipal level, which impacts the reliability of data collected, especially in large events. As one interviewee mentioned, “(…) municipalities do not have enough personnel or resources to apply FIBE, and use people that lack proper training (…)” [Actor 11]. While most interviewees agreed that local governments’ involvement in data collection is essential, some municipalities’ low technical and administrative capacity remains a significant concern. As the principle of “Garbage in, garbage out” suggests, the quality of a system’s input determines the quality of its output. This means that any issues with the initial application of FIBE will persist through subsequent stages that rely on these data.

The challenges arising from low institutional capacity at the local level not only affect data collection but also hinder the use of that information for response and recovery planning. Municipalities vary in economic and human resources and capacities, meaning that smaller municipalities may struggle to use the data provided by FIBE or follow up on affected victims in the system. As one actor suggested, “People often don’t know what happens with FIBE after they answer the survey, they ask the municipal personnel on the ground, and they do not know either” [Actor 1].

Secondly, interviewees agree that FIBE has not fully addressed the issue of intersectoral coordination. As one interviewee put it, “(…) the agencies are used to work in silos, which hinders the potential of tools such as FIBE or Form 2, which should be used together and not individually (…)” [Actor 7]. Although FIBE helps to coordinate public actors, actual collaboration remains limited. While a common classification of disaster victims helps avoid duplicate assistance, the prevailing perception is that most ministries prioritize their own sectoral goals, driven by their specific mandates to address particular areas of action. For example, as one interviewee highlighted, “(…) the gaps in coordination between MINVU and [the Ministry of] National Assets heavily affect the reconstruction capacity of the state because many times land in disaster areas is not properly regularized and without regularization, we cannot rebuild” [Actor 9]. Although the information produced by FIBE provides both offices with a common base to discuss cases, significant challenges remain in breaking down silos.

Finally, the interviews revealed that some actors lack information on the system’s current state surrounding FIBE. Interviewees highlighted the need for a centralized system to share FIBE information. However, the Social Information System in Emergencies (SISE) already exists and is open to all stakeholders directly involved in disaster response. Despite this, some actors were unaware they could request access to these data to serve communities affected by a disaster. This demonstrates that the mere existence of these instruments does not guarantee they will achieve the coordination objectives set by public policy.

3.3. State Legibility and Social Legitimacy

As described by Murray Li [48,49], state legibility encompasses a diversity of tactics and techniques, where not everything aims to impose order. In some cases, what is sought is to legitimize the policies the state seeks to implement. This is especially illuminating when investigating state legitimacy in the context of disaster, where significant resources must be allocated and invested in a specific group of people. The fact that this aid is rooted in legibility instruments makes it seem driven by objective, pre-established rules. As one of the interviewed actors described, “We often feel that we want more liberty to decide how to help, but the existing rules also protect us from corruption and the misuse of public resources” [Actor 4].

As previously mentioned, the shift from EFU to FIBE involved replacing the instrument and reconfiguring the institutional framework related to legibility practices. While improving coordination was the official driver behind most of these changes, the state also sought to enhance the legitimacy of disaster relief in the eyes of the broader population by placing the MDSF at the center of the information system. The EFU was traditionally managed by ONEMI (now SENAPRED), as is common in other countries. With FIBE, however, the MDSF’s role in disaster management expanded, not only in terms of data collection, administration, and safeguarding but also because it validates FIBES and administers several of the aid packages available. The Undersecretariat of Social Services, which coordinates FIBE, also manages Chile’s National Registry of Households (Registro Social de Hogares, RSH), a permanent information system that supports the selection process for beneficiaries of subsidies and social programs. This means the information collected by FIBE can be cross-checked with the country’s regular socioeconomic registries. Particularly after the 2021 revision of FIBE (referred to by some interviewers as “FIBE2”), the MDSF assumed a central role in defining “valid disaster victims”. As one interviewed actor said, “Everyone can fill a FIBE, but that does not mean everyone gets the benefits associated with disaster relief” [Actor 1].

This has become increasingly important as the immediate disaster relief provided through FIBE has been expanded during this period. Table 2 shows the benefits available. A disaster aid working group (Mesa de Ayudas Tempranas) determines which benefits will be provided for each event and the requirements for receiving them. While every grant is defined in the law, the Ministry of the Interior (Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública) has the power to determine the exact requirements in terms of losses and damage, as well as the amount of funds that are going to be used in the event. Then, the Interior requests the funds from the Budget Office at the Ministry of Finance (DIPRES), and once approved, MDSF generates a list of valid beneficiaries based on FIBE.

Table 2.

Benefits that are available via FIBE.

Money for disaster relief actions primarily comes from reallocating funds within the regular national budget. As Actor 4 explains, “We undress a saint to dress another”, meaning they solve a problem by taking resources from another similarly important matter. In this context, the legitimacy of state expenditure is crucial to sustain these policies. Actors perceive that the public is sympathetic to disaster relief expenditures, “but they also want to make sure that the money is spent in ‘real damnificados’” [Actor 3]. The implementation of FIBE is key to achieving this. For this reason, the form must be filled out in person, not online, by an official state surveyor. Each household is linked to an actual residence, and a “head of household” (jefe de hogar) is determined. This information is used to assess damage and needs and validate it through the Chilean National Identification Number (RUT), which all Chileans and visa-holding immigrants hold. Actor 6 explains, “You can have FIBE without RUT (…), but you have almost no benefits available. Today, the platform accepts it (without a RUT) because we want to know the exact number of victims. All that’s required is the head of household to be over 18 years old (…), but you do not receive the grants” [Actor 6].

To summarize, by documenting disaster victims, FIBE effectively defines who qualifies as a victim. This is important because the state must establish a definition of “victim” that society considers legitimate, given the significant resources allocated. FIBE, therefore, plays a key role in legitimizing disaster victims as “valid” victims. Additionally, the increasingly central role of the MDSF means that disaster aid is increasingly guided by the focalization logic that characterizes the Chilean welfare state. In other words, while FIBE seeks to observe and understand the disaster at large, it also enables the state to prioritize certain types of households. As one interviewee noted, “(…) Of course, we would like to reach all those affected, but it is up to the Chilean state to focus the efforts, and that is what we do; FIBE allows us to do that (…)” [Actor 6]. This focalization becomes even more evident in the recovery phase when MINVU uses FIBE to allocate reconstruction funds. This will be discussed in the next section.

3.4. State Legibility and State Blindness

While state legibility projects may appear coherent from a distance, scholars have shown that modern states are not unified bureaucracies but rather operate through complex governance networks with multiple categorization systems that observe the population using labels that often do not align [50].

This is why, despite agreement on FIBE’s role in coordinating immediate aid, sectors have also developed their own legibility instruments for recovery and reconstruction. These data-collection instruments, called “sectoral forms” (fichas sectoriales), are used by state agencies to identify disaster victims according to sectoral objectives and responsibilities. For instance, the Ministry of Economy (Ministerio de Economía, MINECON) assesses economic losses through the Emergency Form for Businesses and Cooperatives (Ficha de Emergencia de Empresas y Cooperativas), and the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI) evaluates crop damage using the Silvoagricultural Impact Form (Ficha de Afectación Silvoagropecuaria). These two forms are combined to generate a Productive Emergency Register (Catastro de Emergencia Productiva), which has helped coordinate aid for the productive sector in recent years, “preventing the duplication of assistance and benefits” [Actor 12].

We focus on MINVU, which is responsible for restoring household habitability and repairing urban spaces in affected neighborhoods [37]. At the local level, MINVU operates through its Regional Ministerial Secretariats (Seremis) and the Housing and Urbanization Service (Servicio de Vivienda y Urbanización, SERVIU), each with specific responsibilities in disaster response and recovery planning.

Over the years, MINVU has increasingly established clear guidelines for allocating resources during reconstruction. These guidelines, compiled in the “Reconstruction Manual” [37], are not legally binding. Still, they reflect the practices that MINVU has institutionalized in the past years to identify the households that may qualify for a post-disaster housing solution “with an expedited process that considers the required urgency and the rigor in the formulation and analysis of these initiatives” [37] (p. 18). To do so, it is essential to assess housing damage and organize this data to guide decision-making. In practice, this involves surveying each house or dwelling in the disaster area, identifying its inhabitants, ownership status, and any potential insurance coverage.

MINVU has developed three forms of damage assessment, which are used by its personnel once the emergency has been stabilized [51]. Form 1 (Ficha 1) looks for a general characterization of affected sectors and provides an overview of the impact on urban and housing areas, without identifying the affected people on a household-by-household basis. Form 2 (Ficha 2) focuses on the technical assessment of damage to individual dwellings or structures, identifying victims on a household-by-household basis. Form 3 (Ficha 3) analyzes damage to public space and urban equipment, such as public squares [51].

The instrument with the most significant impact on people’s ability to access reconstruction subsidies is Form 2. This form can only be applied to households with a validated FIBE, even when it involves re-evaluating housing damage. One problem identified by interviewees is over intervention, which can cause stress to victims who are often surveyed multiple times by different state actors for various purposes, sometimes asking the same questions. The second problem is a duplication of efforts by the state. However, although FIBE was designed to avoid this, the actors agree that FIBE information is regarded as insufficient to guide reconstruction efforts. As Actor 5 puts it, “The reality is that sectors need different information and provide benefits that depend on different types of affectation”.

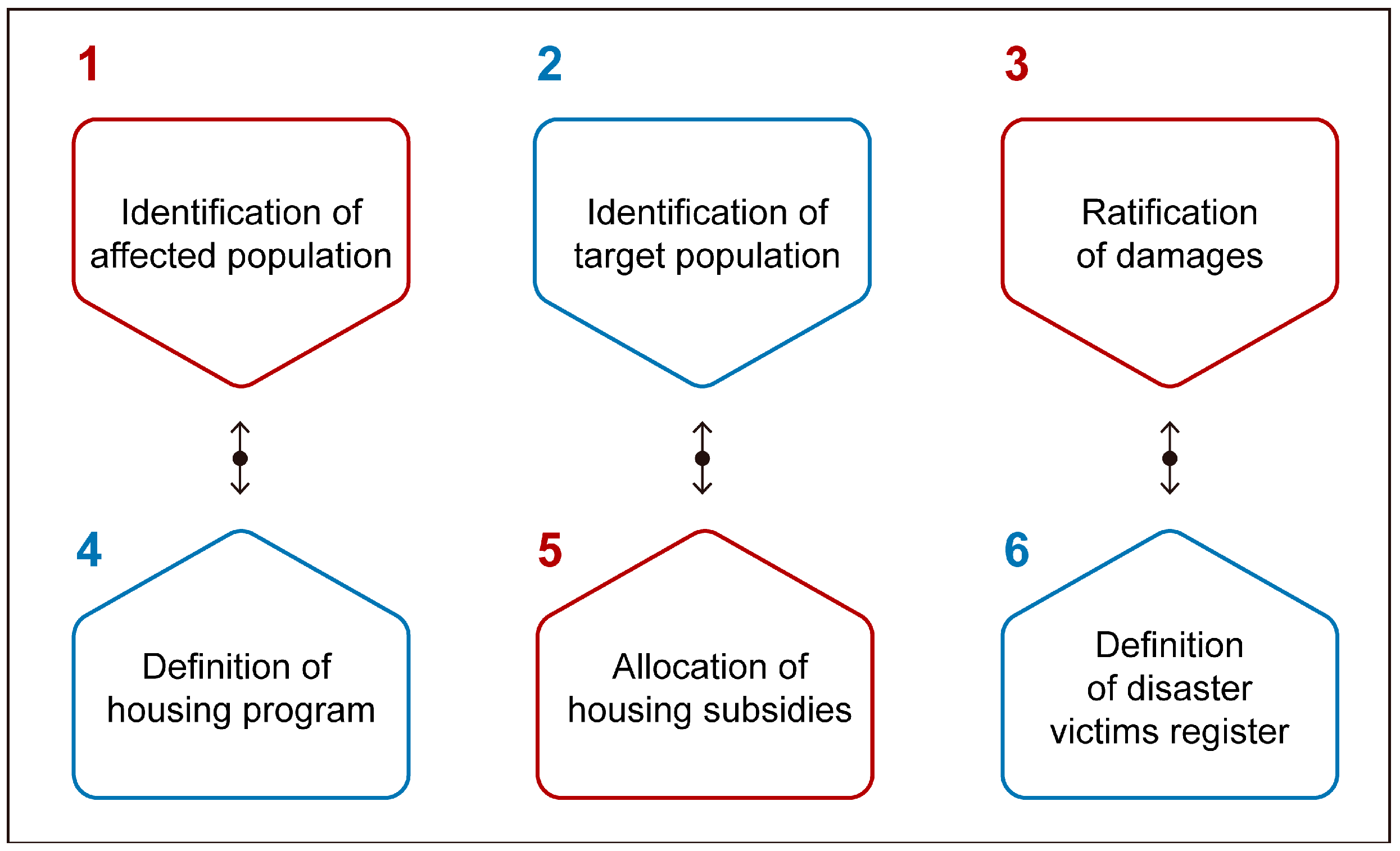

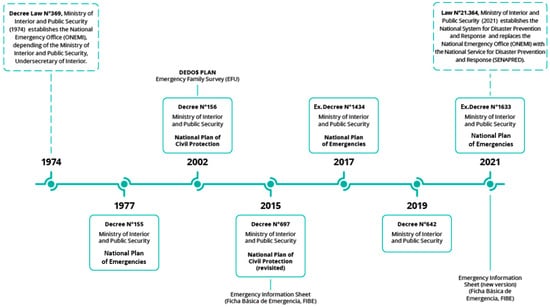

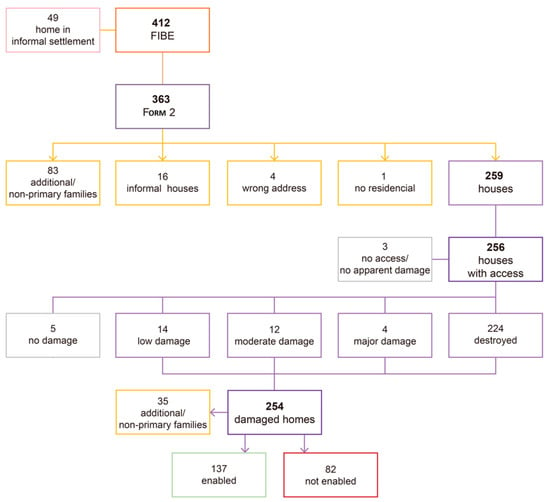

However, through Form 2, the state collects not only information on damage but also data on land and home ownership, occupancy permits, and access to essential services (see the form in Supplementary Materials Section S3). The data provided by Form 2 are then used to generate an official Register of Disaster Victims (Registro de Damnificados), where MINVU categorizes victims and analyzes whether or not they are eligible to obtain reconstruction grants such as a subsidy for building materials (financial assistance for the purchase of building materials to repair roofs and gutters only), self-construction subsidy, reparation subsidy, or subsidy for the acquisition or construction of new housing. The process of producing the Register of Disaster Victims is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process of creating the register of affected households in MINVU. Note that the final product is an official disaster victim register—source: reproduced from Ref. [37].

The second step, “Identification of target population” (población objetiva), is crucial. In its latest version, dated 2021, the target population is defined as someone who is a victim of the disaster, and has the following characteristics [37] (p. 38):

- Is a homeowner or a homeowner’s spouse, with a home evaluated by Form 2 with some damage due to the event.

- Does not own another property for residential use that is in condition to be inhabited.

- Does not have a current subsidy that is either in process or not yet used.

Those who do not fit the definition of disaster victim—such as non-owners or those with other properties elsewhere—are not eligible for reconstruction grants. Thus, Form 2 observes victims and designates them as “legitimate” victims. This legibility process is similar to FIBE’s but produces significantly different results; there is a gap between those identified as victims by FIBE and the “target population” defined by Form 2.

While there are undoubtedly budgetary and political reasons supporting MINVU’s selection process, several interviewees view the requirements of MINVU as problematic. One interviewee summarized the issue, stating that “(…) just like the Romans, to have rights, you had to prove ownership […] the same thing happens here. If the person does not have the title, then MINVU says: I am sorry, but you are not eligible for reconstruction benefits (…)” [Actor 9]. Interviews reveal varying perceptions of this problem, but the actors agree that the reality of victims is complex, and neither FIBE nor Form 2 can account for everyone.

Those living in informal settlements on private or public land declared outside urban limits are seen as particularly difficult victims. In the words of Actor 11, the problem is that “as state agents, we cannot reward this (informality) by giving people bonuses or new houses (…)”. Others believe that “We have to reconsider these criteria because the vulnerabilities present in the territory are the responsibility of the State, not only of the people (…)” [Actor 8]. As we can see, the interviewees have different opinions on how to attend to victims living in informal settlements. However, they agree that Chile’s housing deficit is a structural issue best addressed through law or policy rather than during reconstruction. Even Actor 11 agrees that “if we don’t return people to a certain habitability (in the reconstruction process), the state will have to deal with the problem anyway”.

As we will see in the case study presented in the next section, Form 2 assumes that formality is the norm for victims, but disasters constantly show us that this is not the case. The categories defined also exclude a significant number of victims who are legal occupants of the land but who lack documents or administrative processes to prove it; for example, people who inherited a house but never completed the paperwork or rural homes that have been in a family for generations without a property title to prove ownership. According to one interviewee, “(…) in the case of rural housing or small towns, the lack of land regularization becomes a structural problem. And Form 2 is not designed to deal with this reality (…)” [Actor 9]. In the case of disaster, papers may even be destroyed by the event itself.

In this context, some actors see the lack of a recovery policy that guides reconstruction efforts as a problem. Actor 2 believes that a recovery law is necessary because, currently, “We give these forms too much power; they are presented as objective, but what we are really doing is focusing only on the problems that the law lets us resolve”. Still, others fear that a new law will make reconstruction even more rigid: “There are certainly challenges (in reconstruction), but the idea is not to turn problems into bureaucracy” [Actor 1].

4. Case Study: The “Quebrada de las 7 Hermanas” Wildfire in Viña del Mar (2022)

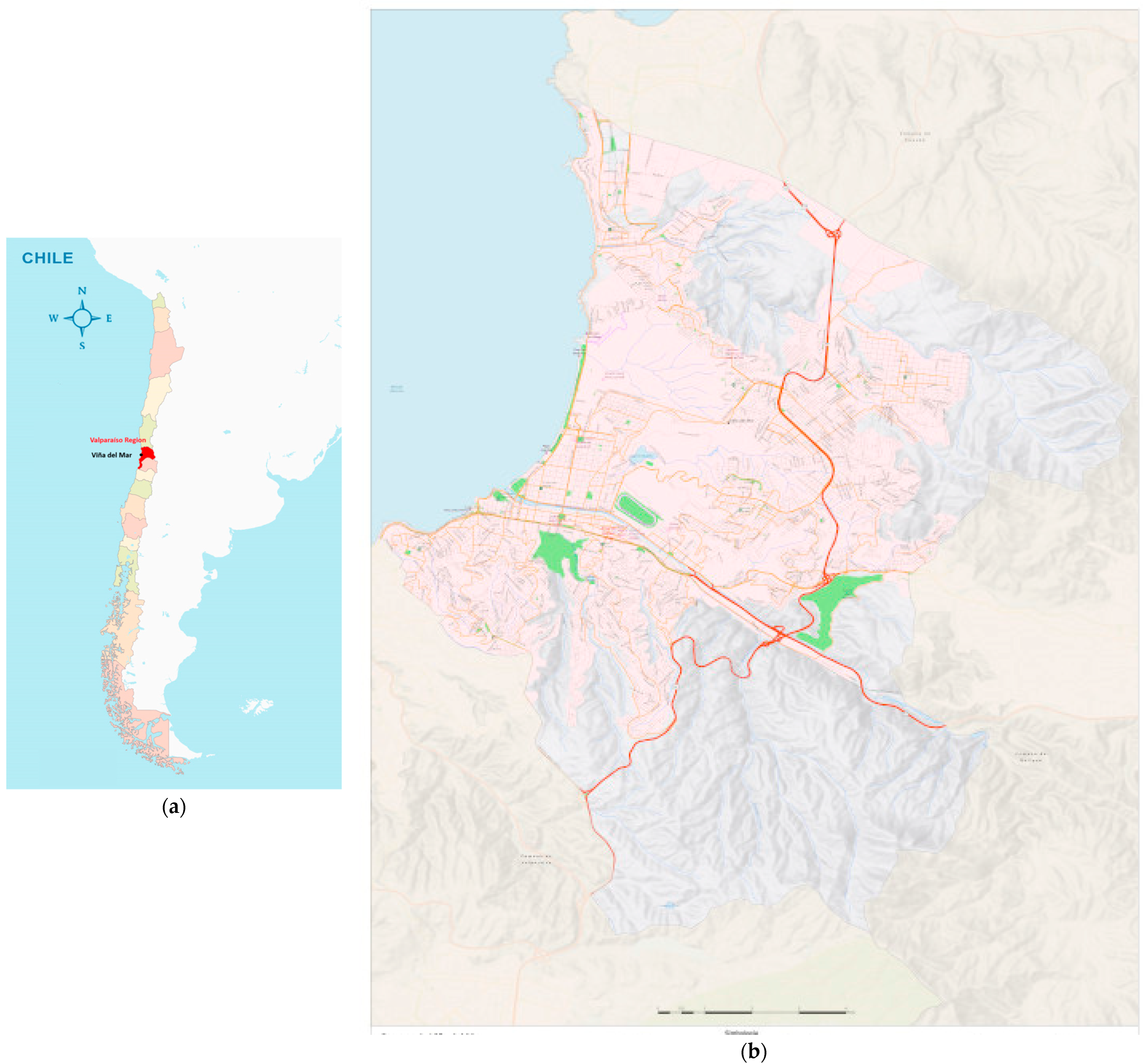

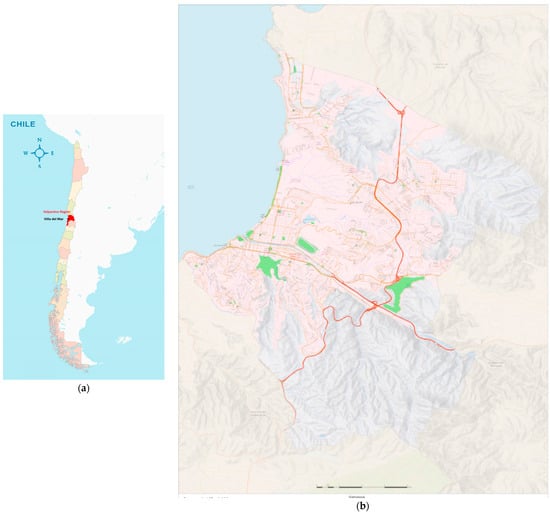

We examine the 2022 wildland–urban interface fire in the “Quebrada de las 7 Hermanas” (Seven Sisters Gorge). This fire occurred just days before Christmas in Viña del Mar, a coastal city facing significant challenges from rapid urbanization that has heightened fire risk, especially in its hillside wildland–urban interface areas. As shown in Figure 3, the fire started in the hills, spreading into the city through the gorge. According to the information gathered from official sources, 114.2 hectares were burned, with two deaths and 441 people injured [52].

Figure 3.

Location of “Quebrada de las 7 Hermanas”, Viña del Mar, Chile (a,b). Source: made by the authors based on maps from Mapoteca, Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile.

An initial damage assessment was conducted using aerial drone images captured by the Viña del Mar Municipality. This survey identified 264 destroyed “roofs” across six affected areas as seen ins Figure 4: Tranque Sur (A), Campamento Vista Loma al Mar (B), Población Puerto Montt y Nueva Esperanza (C), Viña del Mar Alto (D), Población Irene Frei (E), and Esperanza 2011 (F). Figure 4 illustrates the affected area and expansion of the damage.

Figure 4.

Damage assessment conducted by the municipality. (a) Map showing the affected areas around the gorge. (b) Damage to houses and wildlands; (c) municipality personnel surveying victims with FIBE. Source: (a) Planning Office (SEGPLA), Municipality of Viña del Mar, drone flight 23 December 2022; (b,c) pictures taken by the authors the week after the fire.

This initial observation of the disaster is crucial for obtaining a preliminary assessment of the fire’s impact. However, aerial images alone do not provide enough information to accurately count affected houses or make victims’ needs visible. Still, the Municipality can differentiate between houses located on formally urbanized land and those in areas designated as “green” spaces on the official city map. Table 3 summarizes the official information provided by the municipality to MINVU [52]. Note that the number of houses (258) is slightly lower than those identified in the satellite image (264) because some roofs belonged to warehouses or parking lots rather than households.

Table 3.

Situation of affected housing.

Nonetheless, the number of houses alone is insufficient for organizing reconstruction, as grants and benefits are allocated based on households. The FIBE survey recorded 403 households, nearly double the number of houses destroyed. Later, 19 FIBEs were modified following requests from victims to separate households or change the designated head of household [52]. This is because dividing households can be an effective strategy for securing more aid or ensuring that the head of a household meets the grant eligibility criteria.

On January 27, the process was officially closed, reporting 412 FIBEs for this disaster [52]. According to the aggregate data provided by MDSF, these households represented 1107 people, including 268 minors and 194 individuals over 60 years of age [53]. It was also noted that the vast majority of victims (97.4%) were Chilean [53]. This dataset was then used to provide immediate aid, as described before. Also, it was shared with organizations that work with communities during recovery and reconstruction.

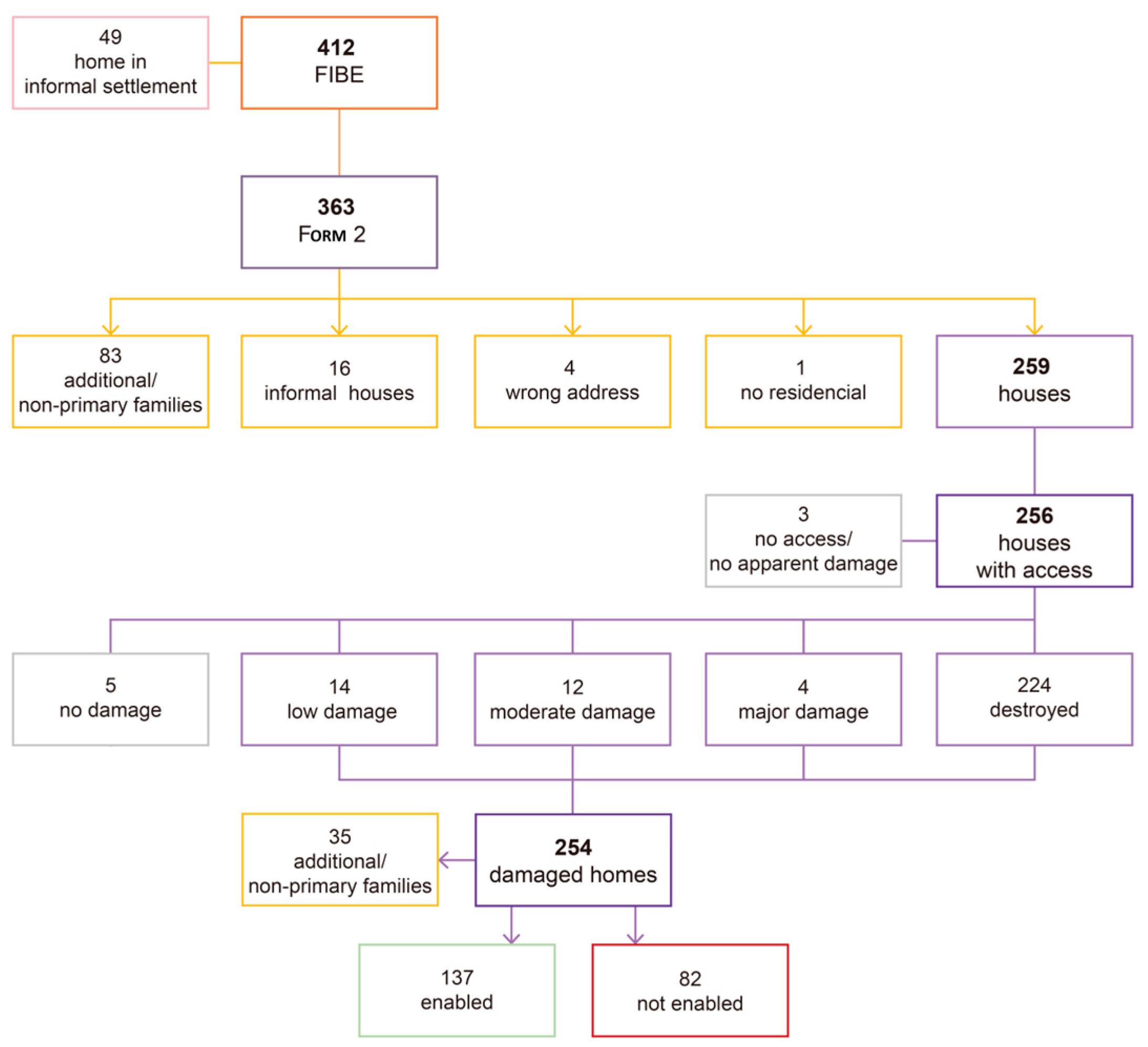

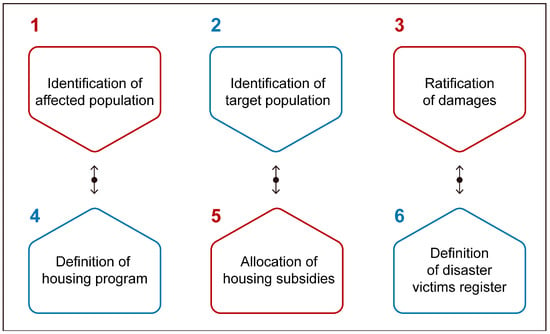

MINVU then surveyed the area using Form 2 to certify damage to housing and other buildings. This second legibility process helps the state assess the disaster’s impact and refine the target population for reconstruction grants. Figure 5 shows the sorting process that produces MINVU’s disaster victims register. First, 49 FIBEs were dismissed as belonging to informal settlements (called campamentos in Chile). As noted earlier, families living in informal settlements are ineligible for reconstruction grants, even if they are disaster victims. As Actor 2 explains, the rationale is that “We cannot allow people to get a ‘fast track’ to a regular public housing subsidy; in the case of fires, this could even create a perverse incentive”. MINVU records indicate that some of these 49 households were already enrolled in regular housing programs before the fire, while the rest were added afterward.

Figure 5.

A diagram showing the sorting process MINVU uses to generate the official cadaster of disaster victims. Note that this diagram does not show the final result but the results are given when the Reconstruction Manual is strictly applied. Source: made by the authors based on official records [53,54].

Second, 83 households were classified as “extended households” or co-residents (allegados in Spanish) and thus were not incorporated into the Form 2 survey. Co-resident families are ineligible for reconstruction subsidies because they either do not own a house or are located on someone else’s land. While dividing households can be effective when completing FIBE, this strategy does not work the same way when families need Form 2 to apply for housing subsidies. If households share a house or land ownership, MINVU will only consider the household that owns the home. Other reasons for ineligibility included 16 families living in shanty houses on public land declared as a “green area”, four addresses that could not be found (validated FIBEs that were nonetheless invalid), and one unoccupied site (no remains of a dwelling were observed).

As we can see in Figure 5, 256 households were finally surveyed using Form 2. Of these, 87.5% were classified as “destroyed”, meaning that the house was beyond repair, allowing the owner to access a subsidy of up to UF 800 (approximately USD 32,612) for rebuilding or purchasing a new home. Homes with “major damage”, where the structure was affected but not entirely lost, qualify for a subsidy of up to UF 300 (USD 12,229). Notably, 22 houses classified as destroyed according to Form 2 had not been deemed beyond repair by FIBE, and one was even labeled as “moderately affected”. This discrepancy may stem from differences in surveyors’ expertise and the fact that the forms have different functions in the provision of aid (see Table A3 in Appendix C for a comparison). Overall, MINVU identified 254 potential beneficiaries (61% of the households listed initially as victims by FIBE).

However, the allocation of reconstruction subsidies also depends on the ability to confirm property ownership, ensuring that the owner of the affected dwelling or their spouse does not own another residential property and does not have an active subsidy for a different house. When these conditions are met, the case is considered enabled or eligible (“habilitado” in Spanish) for subsidy allocation. For this disaster, out of 254 houses assessed for damage, only 154 could initially prove that they owned both home and land (60.6%). Among those who could not be enabled, MINVU recorded authorized usufruct holders without documentation (10), informal land transfers (10), two cases of unregistered inheritance, and 12 heads of households who stated that they occupied the property irregularly. Additionally, this second process of legibility reclassified 35 households as co-residents, as they had a house but were living on someone else’s land (usually a family member). In the end, MINVU declared 137 households eligible for reconstruction subsidies, which accounts for 33.25% of the households initially surveyed with FIBE.

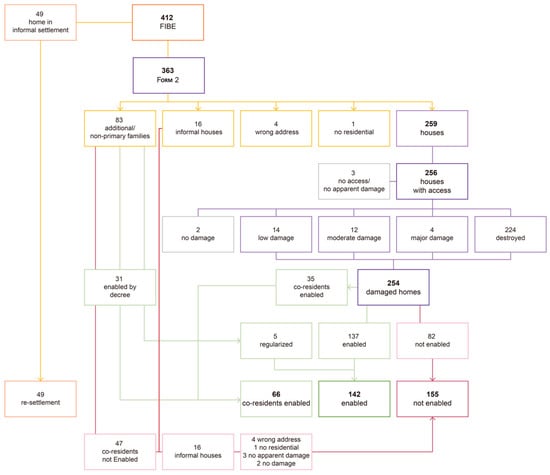

What happened with the rest of the affected households? We can follow cases thanks to the administrative data gathered for this project. Figure 6 shows the results of this analysis. In the case of informal settlements, their trajectory followed the path established by the Precarious Settlements Program (Programa Asentamientos Precarios, also under MINVU), which was already in progress for the 49 households initially excluded from receiving Form 2. As for the 16 families living in irregular housing identified in other affected areas, there is no information on any grants awarded. Additionally, some households could prove home ownership later and were subsequently included in MINVU’s official register.

Figure 6.

Final distribution of enabled and not enabled cases. Source: made by the authors based on official records [53,54].

The most significant change concerns co-resident families. Sixty-six households were deemed “valid” for a subsidy through an administrative decree that relaxed selection conditions and requirements [55]. In other words, MINVU’s strict categorization based on its manual was overruled by a decree that incorporated certain co-resident families into the reconstruction program. Notably, the dwelling was destroyed entirely in 100% of these cases, and the household met all other grant requirements.

Overall, 208 households were finally able to apply for housing subsidies, representing 50.4% of the original families surveyed by MDSF. If we include the 49 households transferred to the Precarious Settlements Program, the percentage of households attended by MINVU post-disaster rises to 62.4%.

We requested information from MINVU on the status of subsidies and benefits for the 208 households enabled for reconstruction in January 2025. As shown in Table 4, two years after the event, only 39.4% of these grants had been collected or had had construction initiated. Upon further investigation, we concluded that at least 18 of the inconclusive cases involved permits that were still under evaluation by the municipality’s Public Works Department (Dirección de Obras Municipales, DOM), and 25 cases were awaiting approval from the regional SERVIU [56]. We do not have data on whether these households still receive accommodation grants (Bono Acogida or Bono Arriendo) but they likely do.

Table 4.

Housing benefits.

The delay in reconstruction can be partially explained by the vulnerability of the hills after the fire, with flooding and landslide risks highlighted in the original reconstruction plan [57]. Additionally, Viña del Mar faced an even larger fire in February 2024, which affected 15,000 homes and overwhelmed the local government’s ability to proceed with reconstruction as planned. While this issue is not directly related to legibility instruments but rather to the capacity to act on the information they provide, the inadequacy and delay in allocating reconstruction grants through these forms undermine their usefulness and effectiveness.

Finally, the reconstruction plan also included work on public spaces, facilities, and infrastructure, including necessary mitigation measures to ensure the reconstruction’s safety, such as a new sewage system. According to official reports, all these initiatives have been completed, except for a care center promised to the community in the reconstruction plan, which remains at 0% progress [56].

5. Discussion

Throughout this article, we have shown that Chile has made significant progress in organizing post-disaster data collection, particularly by standardizing household damage and needs assessments and linking aid and grants to social policy. FIBE, in particular, represents a significant innovation, systematically assessing damages and immediate needs and ensuring that post-disaster data are reliable and comparable nationwide. It also reduces uncertainty among actors, allowing them to form expectations about the roles of other organizations during emergencies. While some actors critique the way FIBE collects data, they acknowledge that its cross-sectoral use facilitates coordination and helps sustain the legitimacy of disaster aid in the eyes of the public.

Several strengths of the Chilean system offer valuable lessons for other countries looking to develop or strengthen their disaster information systems:

- (1)

- Having a common form for the initial damage and needs assessment allows the state to collect information quickly. This facilitates the rapid distribution of emergency aid to all affected households with a validated FIBE.

- (2)

- Developing a data management system that is available to all actors. FIBE is not just a form but a system that includes online and live training and a platform to share this information with all Chilean state agencies involved in recovery. Despite ongoing challenges, we consider the whole data-gathering and information system an asset of the Chilean case.

- (3)

- Including local governments. Storing forms in all municipalities and relying on previously trained municipal personnel ensures that the state can begin surveying immediately after an event, allowing emergency managers and sectoral staff to focus on other critical tasks in the immediate aftermath of a disaster.

- (4)

- The central role of MDSF, Chile’s social policy ministry, being an uncommon characteristic of the Chilean disaster data-management system. We consider this a strength as it helps validate the data provided by FIBE, links information to the national registry of households, and lends legitimacy to the allocation of extraordinary funds.

However, significant challenges remain, particularly in intersectoral coordination, methodological integration of instruments, overintervention, and the effective allocation of resources based on these forms. While FIBE has helped standardize data collection under MDSF, concerns persist about its reliability in large-scale disasters. In addition to municipal personnel not always having sufficient experience to apply FIBE, the process remains manual, with physical forms stored in municipalities nationwide. Incorporating new technologies, such as georeferencing or even artificial intelligence to assist in damage evaluation, should be a key next step to enhance data quality and streamline collection.

Regarding data integration, we have shown that FIBE does not provide all the information the sectors need for recovery planning. For MINVU, Form 2 is crucial for conducting a detailed technical evaluation of houses. However, the lack of common housing damage assessment categories between Form 2 and FIBE leads to duplicated efforts, hinders strategic planning, and may weaken the public’s perception of coherence in state actions.

The lack of integration between the FIBE and other sectoral instruments, combined with remaining challenges in coordination between state agencies, reveals a state apparatus that is still fragmented. FIBE has become the cornerstone of coordination partly due to the lack of a strategy, law, or regulation clearly defining a responsible actor for coordination during recovery. It seems that shared forms and methodologies are the primary connection of a system that still works in siloes.

The most critical conclusion from this research is the exclusion of vulnerable groups due to the rigid eligibility criteria for reconstruction grants. While forms have become more complex over time—allowing for the identification of cases such as undocumented migrants—the requirements for accessing reconstruction funds remain narrow, limiting housing solutions and deepening pre-existing inequalities. Although important political and budgetary constraints prevent the Chilean state from funding reconstruction for those in irregular dwellings, key informants suggest that discussions about this policy problem are often obscured by the legibility of the forms and methodologies used to identify victims. Also, it must be considered that other groups of people are left behind by the sorting process with Form 2, including rural owners and unregistered heirs who may be legal proprietors but face administrative difficulties in being validated as such.

Still, the case study revealed that the system can be flexible. In Viña del Mar, several households were incorporated into the reconstruction plan despite not meeting all the administrative categories predefined in the manual. This includes co-resident families allowed to join housing programs and households in informal settlements that followed the Precarious Settlements Program.

This case study also shows that legibility forms assist state coordination during the emergency phase, but whether they support long-term recovery is unclear. Despite the decree that made some requirements more flexible, several households were made invisible by the sorting process used to create the official registry of victims. Moreover, most victims have not been able to use their grants in the two years since the event. What are the obstacles behind this significant delay? A bottleneck appears once resources and administrative responsibilities reach the local level. As mentioned earlier, not all municipalities in Chile have the same organizational capacities, and even wealthy municipalities, such as Viña del Mar, lack the additional personnel to manage such emergencies. Paperwork related to ownership and building permits contributes to the delays. Overall, the case study suggests that reconstruction takes longer than planned, resulting in significant losses for families and the state, who may end up paying accommodation grants for years.

To address these limitations and build a stronger DRM system, it will be advisable to:

- (1)

- Periodically revise the forms and methodologies used for loss and needs assessment and the administrative rules for resource allocation. Legibility tools are expected to look legitimate and objective, even though social realities constantly challenge the categories defined by these instruments. It is, therefore, essential to continuously review and test these categories against the actual phenomena they aim to make legible.

- (2)

- Improve interoperability. FIBE is regarded as crucial for different state agencies to work together, exchange information, and use that information effectively. However, integrating FIBE with other legibility tools, such as Form 2, could be improved. While it is understandable that sectors require additional tools to observe disasters, it is important to ensure that categories can be shared and understood across sectors.

- (3)

- Strengthen local capacities. Our analysis suggests that the strength of the information system is directly tied to the capabilities of local governments. Local capacities are also crucial for developing and sustaining a reconstruction plan tailored to local territories. In the case of Viña del Mar, as in other municipalities in Chile and abroad, disasters have become frequent. In this context, developing local disaster risk management (DRM) teams will be essential for addressing the challenges ahead. Additionally, regional governments should play a more active role in disaster recovery in Chile. To start, regional officials should support municipalities in the damage and needs assessments, reducing their administrative burden and accelerating post-disaster data collection.

- (4)

- Improve coordination among agencies. A strength of the information system is that actors view FIBE as a crucial tool for sector coordination in the initial post-disaster period. However, Chile should clarify a territorial coordination plan for recovery beyond the initial rehabilitation period. This plan should ensure the sequential and complementary use of different sectoral instruments, minimizing overintervention. The territorial coordination plan must be known and understood by all stakeholders involved in DRM at every political and administrative level.

- (5)

- Define responsibilities regarding reconstruction. The 2021 DRM law did not cover the reconstruction phase, leaving the Chilean state to resolve this in the future. It is urgent to address this issue to ensure that disaster aid and reconstruction funds reach those most affected promptly. This policy should address coordination gaps in data collection and sharing across state institutions to ensure a smooth transition from emergency response to recovery. It should also include ongoing monitoring of legibility tools and tracking the progress and effectiveness of recovery actions.

- (6)

- Review legal and administrative requirements for resource allocation in the reconstruction phase, exploring mechanisms to make processes more adaptable, particularly for definitive housing solutions. This would allow measures to be tailored to the diverse realities of disaster-affected households, preventing rigid norms from worsening pre-existing social inequalities.

- (7)

- Addressing Chile’s housing deficit and supporting the regularization of unregistered legal ownership should be considered essential steps toward a more inclusive and effective recovery framework.

Given the growing challenges posed by climate change and social complexities, these actions are crucial for strengthening institutional capacities and enhancing the Chilean state’s ability to reduce disaster risks and respond to future emergencies. It should also illuminate other countries aiming to advance in this area.

Finally, regarding this study’s limitations, it is essential to acknowledge that we did not incorporate the perspectives of disaster victims in the analysis. Instead, the article focuses on the views of those who use legibility instruments to manage post-disaster policies. It would also be valuable to investigate the operational dimension and decision-making processes faced by those who implement these legibility tools on the ground. However, direct observation of their practical application was beyond the scope of this research. Another limitation is a possible desirability bias in official documents and interviews, as state actors may be inclined to defend the technical and political decisions they make, overestimating successes over failures.

These limitations highlight a valuable opportunity for future studies, which could include non-participant observation during post-disaster damage and loss assessments on the ground and in-depth interviews with disaster victims and responsible officials to gather their insights about the forms used. Such approaches would help better identify and understand the real-world challenges of post-disaster data collection. Additionally, emerging technologies are expected to transform how loss and damage are assessed. In our case study, satellite and drone imagery were already used and are likely to increasingly replace initial on-the-ground reports. The rise of artificial intelligence will undoubtedly enable new observation practices, and future research should consider these developments and their implications for legibility and disaster risk management.

6. Conclusions

Understanding disaster data gathering and management through the framework of state legibility not only sheds light on reconstruction processes in Chile over recent decades but also contributes to a growing body of the literature, showing how predefined categories of observation that translate complex social realities into administratively manageable categories highlight certain aspects of a problem while obscuring others that may be equally important.

Disaster management involves processes and instruments of legibility, which are crucial for understanding outcomes. These tools emerge in response to the challenge of making affected populations visible, translating complex realities into standardized categories that can be acted upon. As such, they often remain in the background of disaster risk management and are rarely analyzed directly. This article, however, highlights that using standardized categories to observe disasters can impact the effectiveness of disaster management. Discussions about disasters often focus on the actions and decisions of political figures, such as mayors and governors, and what they could have done differently, communicated better, or handled more effectively. In contrast, this article argues that disaster aid is shaped by the opportunities and constraints inherent in observing and defining victims.

This Chilean case shows that beyond classification, loss and damage assessments also function as coordination tools, enabling different state actors to operate within a shared framework, reduce uncertainty, and ensure policy consistency. They also play a crucial role in organizing reality and legitimizing state intervention. By embedding aid distribution within standardized procedures, the state reinforces the perception that resource allocation follows objective, pre-established rules, thereby safeguarding institutional credibility and public trust.

Overall, we show that state legibility is not a neutral process but a key structuring force in disaster risk management, shaping policy implementation and its broader societal impact. While loss and damage assessments would be impossible without categories, it is important to recognize that social reality is always more complex than what legibility projects attempt to classify, particularly when seeking to observe extreme events.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17093917/s1, Section S1: Questionnaire; Section S2: FIBE (Basic Emergency Information Sheet; Section S3: Ficha 2 (Form 2); Section S4: Typography of Damage to houses and subsidies available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.; methodology, M.G.; interviews, M.G. and students; formal analysis, M.G. and K.C.; investigation, M.G. and K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C.; writing—review and editing M.G. and K.C.; visualization, M.G. and K.C.; project administration, M.G.; funding acquisition, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chilean National Research and Development Agency (ANID) under ANID/FONDECYT Iniciación/11220562, “Recovery and Reconstruction after Socionatural Disasters: A Model for Interdisciplinary Analysis and Public Policy Intervention”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of P. Universidad Católica de Chile (210413001, 20 April 2022, revised 7 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The interviews generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly available to maintain participants’ anonymity. Data regarding the case study obtained via the Chilean National Council for Transparency (Law No. 20.285) cannot be made publicly available but can be shared upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the students who helped with the interviews as part of their undergraduate capstone in the Instituto de Sociología of P. Universidad Católica de Chile: Nicolás Martínez and Javier Fernández. We also want to thank the Chilean National Research and Development Agency (ANID) for funding under project Fondecyt INICIO No. 11220562, “Recovery and Reconstruction After Socionatural Disasters: A Model for Interdisciplinary Analysis and Public Policy Intervention”, and the continuous support of the National Research Center for Integrated Disaster Risk Management (CIGIDEN), Chile, ANID/FONDAP/1523A0009.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and the funders had no role in the study’s design; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FIBE | Ficha Básica de Emergencia (Basic Emergency Information Sheet) |

| PNRRD | Plataforma Nacional para la Reducción del Riesgo de Desastres (National Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction) |

| MDSF | Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia (Ministry of Social Development and Family) |

| MINVU | Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (Ministry of Housing and Urbanism) |

| ONEMI | Oficina Nacional de Emergencia del Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública (National Emergency Office). Recently replaced by SENAPRED |

| SENAPRED | Servicio Nacional de Prevención y Respuesta ante Desastres (National Service of Disaster Prevention and Response). Formerly ONEMI |

| FIBEH | Ficha Básica de Emergencia Hídrica (Basic Water Emergency Information Sheet) |

| SICE | Sistema Integrado de Catastro Social en Emergencias (Integrated System of Social Cadastre in Emergencies Unit) |

| ISE | Unidad de Información Social en Emergencias (Emergency Social Information Unit) |

| SISE | Sistema de Información Social en Emergencias (Social Information System in Emergencies) |

| EFU | Encuesta Familiar de Emergencia (Emergency Family Survey) |

| EDANIS | Evaluación de Daños y Necesidades de Infraestructura (Single Damage and Infrastructure Needs Assessment Report) |

| REDES | Formulario Único de Recepción, Entrega y Disponibilidad de Elementos de Socorro (Single Form for the Reception, Delivery, and Availability of Relief Elements) |

| DRM | Disaster Risk Management (Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres) |

| MINECON | Ministerio de Economía (Ministry of Economy) |

| MINAGRI | Ministerio de Agricultura (Ministry of Agriculture) |

| SERVIU | Servicio de Vivienda y Urbanización (Housing and Urbanization Service) |

| RSH | Registro Social de Hogares (National Registry of Households) |

| UF | Unidad de Fomento (financial unit of account used in Chile, whose value is adjusted daily according to inflation) |

| DITEC | Technical Division of Housing Studies and Promotion, Ministry of Housing and Urbanism (División Técnica de Estudio y Fomento Habitacional, Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo) |

| DIPRES | Budget Office, Ministry of Finance (Dirección de Presupuestos, Ministerio de Hacienda) |

| IPS | Social Security Office (Instituto de Previsión Social, Ministerio del Trabajo y de Previsión Social) |

Appendix A. Official Documents and Sources Analyzed

Appendix A.1. Legibility Instruments

- [EFU]: Encuesta Única Familiar. Oficina Nacional de Emergencia, 2002.

- [FIBE 15]: Ficha Básica de Emergencia, Versión 2015. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia (MDSF), 2015.

- [FIBE 21]: Ficha Básica de Emergencia, Versión 2021 Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia (MDSF), 2021.

- [Form 2]: Ficha Técnica de Catastro Individual de Vivienda Afectada. Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (MINVU).

Appendix A.2. Data Sets

- [Registro Desastres]: Database of Disasters and Reconstruction Processes post-2010_Actualizado. Developed by the project based on information provided by Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo, Comisión para la Reducción del Riesgo de Desastre via Convenio CIGIDEN.

- [FIBE IF2022]: Database with data from FIBE for the wildfire of December 2022 (anonymized). Request for Access to Information to Subsecretaría de Servicios Sociales via Consejo Nacional para la Transparencia (Law No. 20.285). No. IA008T0004381, 23 October 2024.

- [Registro Damnificados IF2022]: Database with data from Form 2 (anonymized). Request for Access to Information to Seremi Valparaíso Ministerio Vivienda y Urbanismo via Consejo Nacional para la Transparencia (Law No. 20.285). Request No. API006T0001677, 9 September 2024.

Appendix A.3. Supporting Documents

- [DEDO$]: Manual del Sistema de Evaluación de Daños y Necesidades en Situaciones de Emergencia y Desastre. Anexo N° 8. Ministerio del Interior (Interior).

- [Borrador PNRI] “Borrador Política Nacional para la Recuperación Integral Ago_2023 V2”, Plataforma Nacional para la Reducción de Riesgo de Desastres (PNRRD), Mesa 5.2.1. Recuperación Sostenible, via Convenio CIGIDEN.

- [FIBE2-Manual] “Documento de Profundización Modulo 2: Procedimientos FIBE y FIBEH” Unidad Sistema Integrado de Catastro Social en Emergencias, División de Focalización, SSS. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia (MDSF).

- [Manual Reconstrucción] “Manual para la Reconstrucción”. Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (MINVU), versión 2021. Via Convenio Cigiden.

- [Mapa Actores MINVU]: “Mapa de Actores para la Recuperación Integral”, May 2022. Developed as part of the project Fondecyt INICIO, “Recovery and Reconstruction after Socionatural Disasters: A Model for Interdisciplinary Analysis and Public Policy Intervention”. Grant number #11220562.

- [Minuta 005 MINVU]: “Minuta -005 Evento: Incendio Nueva Esperanza—Viña del Mar. Región de Valparaíso”. 28 de febrero 2023. División Técnica de Estudio y Fomento Habitacional (DITEC). Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo.

- [Plan Reconstruccion IF22]: “Plan de Reconstrucción Quebrada Siete Hermanas, Viña del Mar. Plan Maestro elaborado bajo perspectiva de Reducción de Riesgo de Desastres”. Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo & Municipalidad de Viña del Mar. via Consejo Nacional para la Transparencia (Law No. 20.285). Request No. AP006T0001858.

- [Reconstruccion IF22-S]: “Reconstrucción Incendio Quebrada 7 Hermanas 2022. Región de Valparíso (Viña del Mar)”. Informe de Seguimiento, 2024. Serviu Región de Valpariso. Request for Access to Servio Valparaíso via Consejo Nacional para la Transparencia Consejo Nacional para la Transparencia (Law No. 20.285). Request No. AP006T0001858.

Appendix A.4. Laws and Decrees

- [Resolución Exenta 447], Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 2023.

“Llama a proceso de selección en condiciones especiales para el otorgamiento de subsidios habitacionales del fondo solidario de elección de vivienda, regulado por el d.s. n° 49 (v. Y u.), de 2011, en la alternativa de postulación individual y colectiva para las tipologías de pequeño condominio, densificación predial y construcción en sitio propio, incluyendo el procedimiento de autoconstrucción asistida en los casos que procede, para familias cuyas viviendas se vieron afectadas por el incendio ocurrido en viña del mar, en la región de Valparaíso” Available online: https://bcn.cl/3e32n (accessed date 30 January 2025).

- [RES.EX284]. Resolución 284 EXENTA. Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo.

“Aprueba Fichas para Evaluación Técnica y levantamiento de información de la afectación en sectores, viviendas y obras del espacio público de competencia del sector vivienda, asociadas al plan de respuesta sectorial frente a desastres”. Available at: https://bcn.cl/3l8a1 (accessed date 30 January 2025).

- [Decreto Supremo 155] Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, 1977.

Aprueba Plan Nacional de Emergencia. Available online: https://bcn.cl/3odup (accessed date 30 January 2025).

- [Decreto 156] Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, 2002.

Aprueba Plan Nacional de Protección Civil, y deroga decreto N° 155, de 1977, que aprobó el Plan Nacional de Emergencia. Available online: https://bcn.cl/2f86r (accessed date 30 January 2025).

- [Decreto 697] Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, 2015.

Modifica decreto N° 156, de 2002, aprueba Plan Nacional de Protección Civil, y deroga decreto N° 155, de 1977, que aprobó el Plan Nacional de Emergencia. Available online: https://bcn.cl/2gein (accessed date 30 January 2025).

- [Decreto Ex. 1434] Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, 2017.

Aprueba Plan Nacional de Emergencia. Available online: https://bcn.cl/2geg2 (accessed date 30 January 2025).

- [Decreto 642] Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, 2019.

Modifica decreto N° 156, de 2002, del ministerio del interior, que aprueba plan nacional de protección civil, y deroga decreto N° 155, de 1977, que aprobó el Plan Nacional de Emergencia. Available online: https://bcn.cl/3nkef (accessed date 30 January 2025).

- [Decreto Ex. 1633] Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, 2021.

Modifica Decreto N° 1.434 Exento, de 2017, que Aprueba Plan Nacional de Emergencia. Available online: https://bcn.cl/2qvcn (accessed date 30 January 2025).

Appendix B. Public Actors Interviewed

Table A1.

General list.

Table A1.

General list.

| Institution | First Round (September–October 2022) | Second Round (May–June 2023) | Third Round (March–April 2024) | No. of People |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Interior (including SENAPRED) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Ministry of Housing and Urbanism | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Ministry of Health | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ministry of Social Development and Family | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Ministry of Economy | 2 | 2 | ||

| Ministry of Labour | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ministry of Agriculture | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ministry of National Assets | 1 | 1 | ||

| Recovery and Reconstruction Coordinators | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Total | Interviews: 22 | People: 18 | ||

Source: authors, 2025.

Table A2.

Actors with direct quotes in the article.

Table A2.

Actors with direct quotes in the article.

| Identification | Gender | Public Sector Area |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | Male | Emergency Response |

| Actor 2 | Female | Housing |

| Actor 3 | Female | Emergency Response |

| Actor 4 | Male | Housing |

| Actor 5 | Female | Economy |

| Actor 6 | Male | Social Welfare |

| Actor 7 | Male | Recovery |

| Actor 8 | Female | Recovery |

| Actor 9 | Male | Recovery |

| Actor 10 | Female | Health |

| Actor 11 | Female | Housing |

| Actor 12 | Male | Economy |

Source: authors, 2025.

Appendix C. Pre-Defined Damage Categories

Table A3.

Comparison between the categories in FIBE and Form 2.

Table A3.

Comparison between the categories in FIBE and Form 2.

| Instrument | FIBE | Form 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Database provided by | MDSF | MINVU |

| Focus | Households | Houses/dwellings |

| Damage categories as defined by each instrument | 1. Not affected | 1. Not damaged |

| 2. Slightly affected | 2. Minor damage | |

| 3. Moderately affected | 3. Moderate damage | |

| 4. Severely affected | 4. Major damage | |