Abstract

This article presents a marketing campaign guide to support nonprofit and governmental organizations, such as academic research institutes or governmental agencies, that wish to develop support tools for the food industry. It offers a systematic and target audience-centered approach which guides nonprofits through the various steps of a marketing campaign, from defining the required values of a new product or service to ultimately launching it. The text also explains how a target audience-centered marketing approach was applied in a case study of developing and transferring the LAV platform (LAV—Avoiding Food Waste, from the German “Lebensmittel Abfall Vermeiden”), a website that has been specifically set up and targeted to small- and medium-sized companies (SMEs) in the German food sector that wish to reduce food waste in their operations. Currently, there are more than 500 tools available in the English or German language which attempt to support companies in the food sector in their food waste reduction efforts. However, so far there has been no platform that could gather all these tools to facilitate SMEs’ access to them. The LAV platform compiles various relevant tools from academia as well as from industry and makes the most suitable tools available in a toolbox published on the Internet platform. Here, the tools are structured by topic and market segment; its user-friendliness was tested applying participatory methods which involved SMEs and industry organizations. The LAV platform, as well as target audience-centered marketing approaches more generally, could act as role models for other international projects that also have the goal of setting up and promoting tool-gathering systems.

1. Introduction

In Germany, 39% of the 11 million tons of food wasted along the food value chain from the manufacturer to the consumer annually is caused by the food production industry (17%), by large scale consumers (17%) such as restaurants and public caterers, and by retailers (5%) [1]. All food produced has gone through various steps along the supply chain, requiring resources such as energy, water, or other materials before finally reaching the consumer. Therefore, if food is discarded, not only is the final product wasted, but also all the other resources that have been used during production and transportation. With 3.3 gigatons of CO2 equivalent, worldwide food waste represents the third top emitter after the total emissions of the USA and China [2]. As a result, the reduction of food waste has gained increased attention internationally, and has been the subject of numerous studies and projects (e.g., [1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]) with the goal of identifying the root causes of food waste, or of developing measures, concepts, and tools to counteract it. Besides lowering the environmental impact of food waste, its reduction leaves room for economic savings. Currently, more than 500 tools in the English or German language are available on the Internet free of charge. These include tools that help with collecting or monitoring data; materials such as films or posters to raise awareness and to educate staff; or concepts that focus on recycling and avoiding food waste for use in business. They have largely been developed by nonprofit organizations, such as governmental agencies, or through academic projects (e.g., World Resources Institute [22], United against Waste [23], Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) [10], and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Ireland [24]).

Small- and medium-sized companies (SMEs) in the food sector are facing high competition as a large number of food producers supply a small number of retailers and large-scale consumers. This has put these businesses under high competitive pressure to improve efficiency and reduce costs. Therefore, for food producing companies, the reduction of food waste not only makes sense from an ethical point of view, but it also leads to cost savings, which, considering the highly competitive market, may be critical for the companies’ long-term success. As opposed to large enterprises, SMEs of the food sector, including producers, retailers, and the hospitality sector, have fewer financial and human resource capacities to combat food waste. Daily work routines often require the staff’s full attention and leave no time to surf the Internet for useful tools to counteract food waste. There are two important premises that contribute to a tool’s successful implementation on the market. First, SMEs in the food sector need to actually adopt the tools designed to support efforts in this area, and second, SMEs need to be aware of the tools. To address these two complementary premises, it is necessary to have a marketing strategy that focuses on the target audience, rather than the product or service offered. A clear focus on the target audience is as important for the success of nonprofit organizations (nonprofits) as for profit-oriented companies (for-profits) [25]. However, nonprofit marketing research has revealed that nonprofits are often organization-centered rather than audience-centered [26]. In this article, the authors develop a guide for a target audience-centered marketing campaign. This marketing campaign guide specifically addresses the needs of nonprofits acting in the transdisciplinary field of the food sector. It targets organizations that wish to develop and market support tools for SMEs in the food sector. The authors also introduce a case study of the LAV platform (LAV—Avoiding Food Waste, German: Lebensmittel Abfall Vermeiden). The purpose of this project was to develop an online platform focusing on the reduction of food waste in German SMEs, and market it in a process that focuses on the target audience.

2. Aims and Objectives

The key aim of this study is to provide a marketing guide for nonprofit organizations, such as academic research institutes or government agencies that wish to develop and transfer support tools and services for SMEs in the food sector. The development of this guide proceeds in three phases. First, the authors clarify the concept of target audience-centered marketing and outline the specific challenges nonprofits face. Second, in a case study, the authors apply participatory methods to develop and transfer a target audience-centered online platform. This online platform targets SMEs in the German food sector, including producers, retailers, and the hospitality sector, that wish to reduce food waste in their organizations. Moreover, the platform is also meant to serve as a role model for other international projects which have the goal of developing similar tool-gathering platforms. In the last phase, the authors develop a guide for a marketing campaign based on the theoretical considerations of Phase I and the experiences gained from the case study in Phase II. This guide enables nonprofits to successfully develop and transfer their services by adopting a target audience-centered mindset. The marketing campaign guide is specifically adapted to the requirements of the food sector.

3. Overview of the Project Design and Methodology

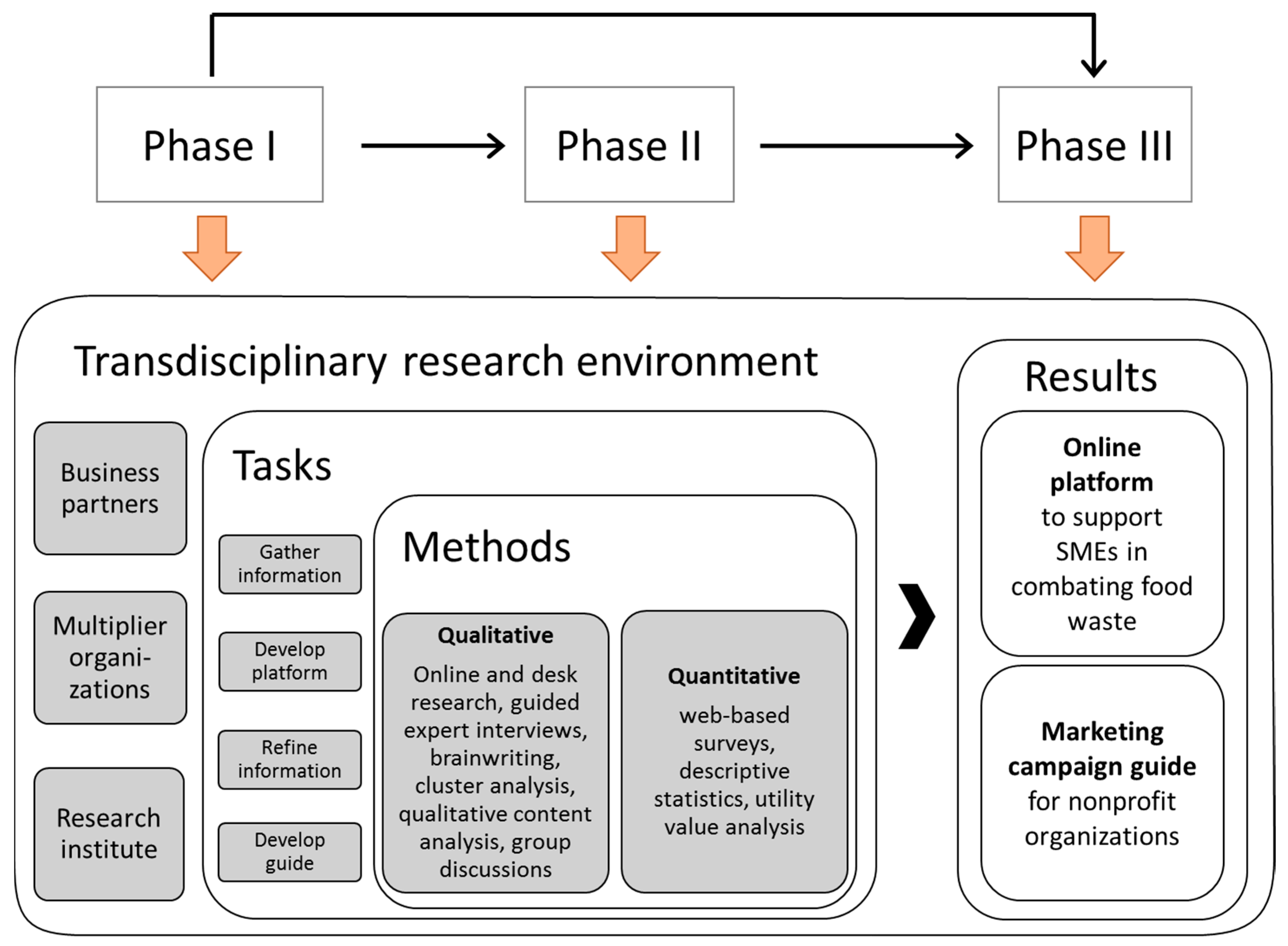

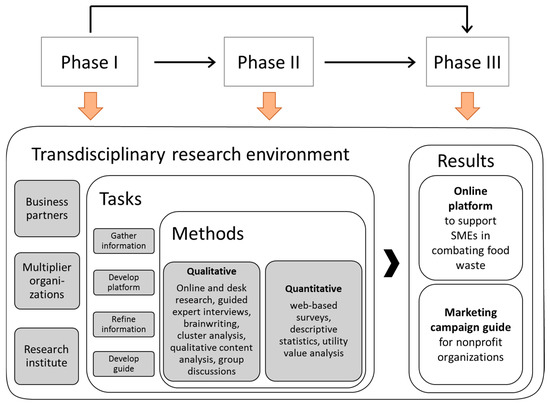

This research project was conducted in a transdisciplinary environment in which the Institute of Sustainable Nutrition (iSuN, a research institute of Münster University of Applied Sciences) served as the project leader, working closely with partners from business (SMEs from the German food sector) as well as with sector-specific guilds, trade associations, or consultants. The project includes three phases and uses multiple methods (see Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the project phases, research questions, tasks, and methods applied. In Phase I, the process of adapting a target audience-centered mindset is studied from a marketing perspective. This phase is presented in Section 4 of this article. In addition, the section outlines the mutual and the different characteristics of for-profits and nonprofits. The second phase consists of a case study. In Section 5, the authors present the online platform, which was developed and transferred in a way that took advantage of target audience-centered marketing. This specific platform serves as a support tool to facilitate the reduction of food waste by SMEs of the German food industry and the hospitality sector. Phase III consists of the development of a guide for a marketing campaign (see Section 6) based on the results of Phases I and II. This guide is designed to support (nonprofit) organizations, such as research institutes or governmental institutions, that want to undertake efforts to develop support tools for SMEs of the food sector. It enables such organizations to better understand the needs of their target audience and transfer these needs to features of the product or service and to efficient promotional activities.

Figure 1.

Project phases, transdisciplinary research environment, tasks, and methods of developing the marketing campaign guide for nonprofit organizations. SMEs: Small- and medium-sized companies.

Table 1.

Overview of the research project: project phases, research questions, tasks, and methods applied.

4. Phase I: Target Audience-Centered Marketing in a Nonprofit Environment

Marketing management deals with the efficient and need-satisfying design of exchange processes [27]. Since the 1950s, when modern concepts of marketing first emerged, marketing has adapted to changing market structures, political and social requirements, and customer needs. The marketing mindset has changed from a product/service mindset and a sales mindset to a target audience mindset. While a product/service mindset focuses on the product and its features (ignoring the needs of the customer), and a sales mindset means the best way of persuading the customer to accept what is on offer, a target audience mindset focuses on the perceptions, needs, and wants of the target market.

A meta-analysis of 11 empirical papers revealed that market orientation is positively related to performance [25]. In the study, the correlation was even higher for nonprofits compared to a similar setting with for-profit organizations. Besides market orientation, customer orientation has come to be an important point for management, as growing competition has started to change customer behavior [28]. Several studies have proven a significant positive correlation between company success and a strong customer orientation [29]. Although market orientation (which implies a focus on a target audience) is a crucial aspect for successful marketing strategies for both for-profit and nonprofit enterprises, a study in the UK, the USA, and Australia revealed that nonprofits are still dominated by an organization-centered mindset in which marketing appears to be primarily defined by promotional activities [25,26]. However, what does target audience-centeredness mean for an organization? Andreasen and Kotler [25] provide the following explanation:

“A target audience centered organization is one that makes every effort to sense, serve, and satisfy the needs and wants of its multiple publics within the constraints of its budget”.[25]

In the following paragraphs, this article describes how an organization can become focused on its target audience. The first milestone for nonprofits is to understand what target audience-centeredness means. Andreasen and Kotler [25] describe the following clues that demonstrate that your organization is organization-centered rather than target audience-centered:

- (1)

- The value proposition of your own enterprise’s product or service is seen as extremely desirable: Understand that what you consider the most important values may not satisfy the needs of the target audience. In other words, it might be necessary to adapt what you are offering to the target group by applying typical business terminology rather than using scientific language. Moreover, keep in mind that time usually is rare for businesses in the food sector. Long explanatory texts are likely to be skipped by the audience. Apply methods of market research to understand the target group and its needs. Use incentives that work in business. Contributing to fewer greenhouse gas emissions might not be as persuasive for managers as the opportunity to reduce costs.

- (2)

- You attribute failure to a lack of motivation or ignorance on the part of the target group: Understand that your product or service should fit the target audience rather than the target audience changing to fit the offering. If a tool fails, use market research to understand the reasons. Work with lead users or conduct interviews with potential users. Get them to assess your tool to better understand their needs and how these needs could be integrated into the valuable good you are offering.

- (3)

- You underestimate the importance of target-audience research: Understand that target-audience research delivers valuable information about attitudes and behavior, which enables you to offer something that provides necessary benefits. Target-audience research may also support you in prioritizing information and thus may facilitate decision-making.

- (4)

- You conflate marketing with promotion: Understand that the marketing challenge is not only to improve promotional activities, such as issuing a better brochure, placing more ads or writing more press releases. The challenge is to adapt the whole marketing mix (e.g., product features, prices, distribution channels) to the target audience in order to satisfy their needs.

- (5)

- You use a single “best” marketing strategy rather than approaching each market segment with specific strategies: Markets are not monolithic, as the target audience may include different segments that all need to be accounted for in the marketing mix. This may, for example, involve the usage of different languages for diverse segments of the target audience or the need for different levels of comprehensiveness.

- (6)

- You underestimate the effect of generic competition and fail to provide incentives for the target group to its change behavior: Support tools for the food sector have a lot of competition, which is not limited to other tools having similar targets. The largest competitor is the daily work routine of food businesses. Understand that time in companies is often a rare commodity. Hence, managers may not have the opportunity to take the time to learn how a tool works. Find strategies to address this by designing tools that are as easy to use as possible, by providing a support hotline, or by expanding your portfolio with other beneficial goods. For example, instead of just providing an online tool, offer a product service system (PSS) by integrating the optional service of a consultant to your portfolio or by offering webinars.

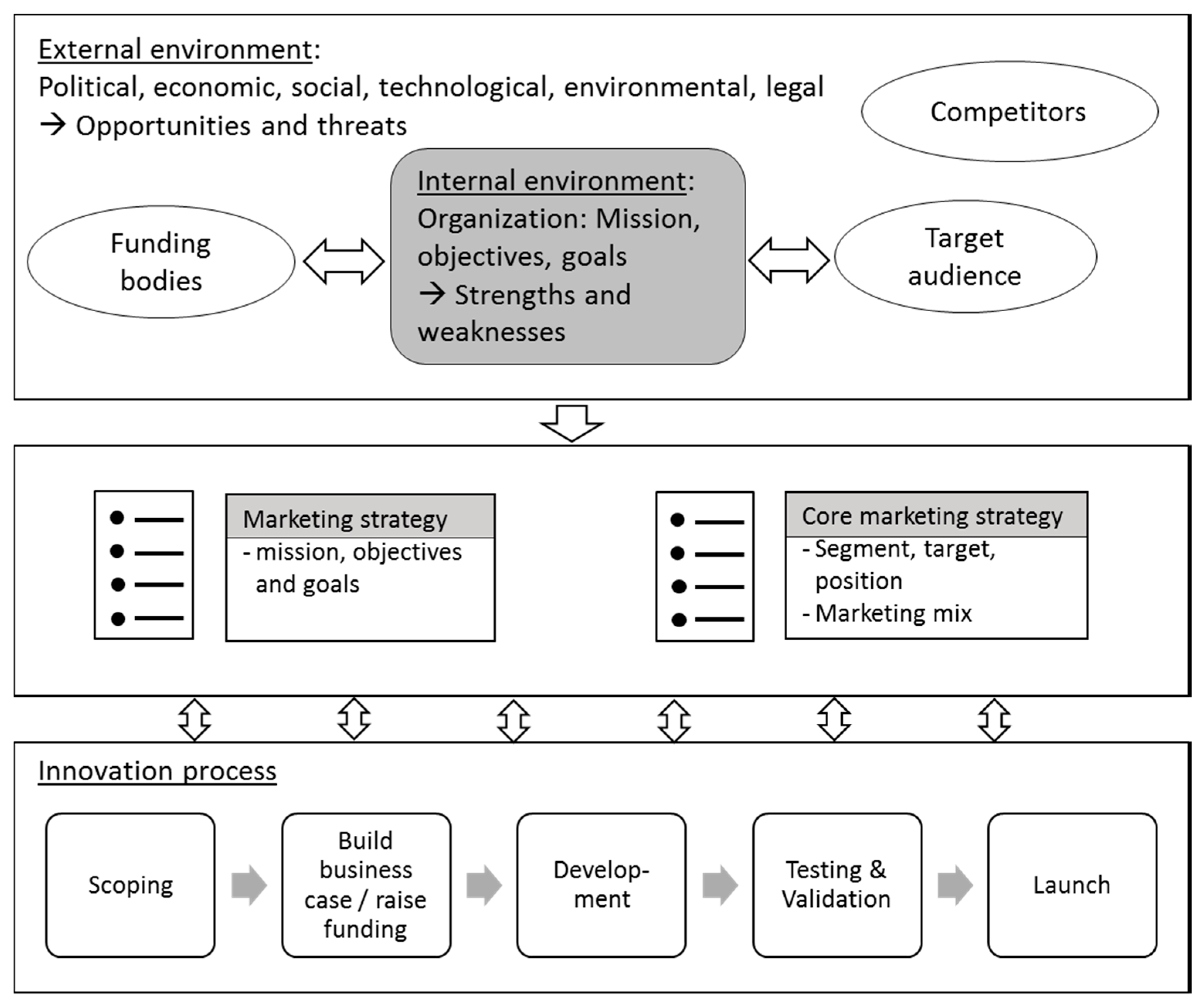

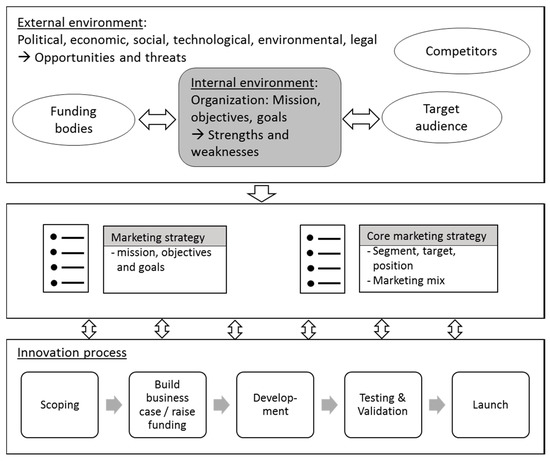

The second step for an organization to become target audience-centered is understanding its own situation. Analysis is needed to reveal who its clients are, who is providing it with funding, and who its competitors are. The analysis also should show what the competition is offering, and how it differs from what the organization itself has on the market. Answers to these questions are provided by an analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) of an organization [25,27,30,31,32]. Figure 2 demonstrates the relationship between the external environment, in which the organization is situated; the internal environment, given by organization-specific characteristics; and the marketing strategy, which should be based on an analysis of the given setting. Weaknesses refer to organizational constraints, such as limited spatial capacities to implement a production facility. In contrast, strengths are determined by advantages that an organization holds vis-à-vis others, such as equipment or know-how. Opportunities and threats, however, are given by external factors of the environment, such as legal constraints supporting or hindering the targeted objectives of an organization. Based on the SWOT analysis, the organization can determine its marketing strategy, i.e., the mission, objectives, and goals, substantiating it by a “core” marketing strategy, which specifies market targets and/or the elements of the marketing mix [25]. The traditional marketing mix consists of the “4 Ps”, which comprises the elements of Product, Price, Place, and Promotion [31]. For services, the “7 Ps” approach can be used, which additionally includes the elements of People, Processes, and Physical Facilities [27]. Figure 2 also highlights the fact that all steps of an innovation process [33] leading to the development of a new product or service need to be coupled with a marketing strategy. In other words, target audience centeredness directly influences the development of a new product or service.

Figure 2.

Relationships among the market environment, the market structure, and the innovation process (Source: the authors, based on [27,31,33]).

Similar to for-profits, nonprofits must meet the needs of their target audience to be successful [31]. In addition, just like for-profits, their objective is to offer products or services for a certain target audience (or to raise funds for charitable purposes). Meffert et al. [27] states that the fundamental principles of marketing are also valid for non-commercial exchange processes. Hence, marketing concepts can also be transferred and applied to exchange processes in the nonprofit market. However, as opposed to for-profits, nonprofits face special challenges. They often attempt to change behaviors or attitudes, which means the benefits accrue to others and may not directly be seen by the individuals involved, or people may be indifferent about the topic (e.g., saving water or recycling). Moreover, the behaviors nonprofits want to influence often deal with topics that are embarrassing or that are understood controversially, such as obesity or abortion. Therefore, research data might be difficult to obtain or may contain socially desired answers. In other cases, the effects of behaving in the desired way involve intangible social or psychological effects that are hard to present to the target audience (e.g., the effect of listening to a symphony orchestra). Nonprofits also generate no or relatively little net income [25].

Such challenges require nonprofits to adopt appropriate marketing strategies. For example, the non-generation or insufficient generation of revenue requires attracting an additional target audience that provides funding, and second, it requires the utilization of other evaluation mechanisms, which are not profitability-based. In order to be successful, nonprofits seeking to improve the performance of their existing portfolio or seeking to offer new products or services need to adapt their entire innovation process, from generating and gathering ideas to ultimately launching products or services in an audience-centered marketing program. This can be done by effective planning of a marketing campaign that consistently focuses on the target audience [25]. A marketing campaign describes how organizational strategies are translated into specific projects. The nonprofit’s marketing campaign needs to be adapted to the nonprofit environment. Andreasen and Kotler [25] describe six steps of a marketing campaign: Conducting formative research to understand the target audience; Planning; Pretesting; Implementation; Routine performance monitoring; and Recycling and Revision. Based on the latter considerations, Section 6 outlines a marketing campaign guide for nonprofits, such as academic research institutes and governmental agencies. This guide is designed to support nonprofits in their efforts to develop tools or services for SME companies and to help them successfully transfer these offerings to the food sector.

5. Phase II: The “Developing and Marketing the LAV Platform” Case Study

The LAV platform and the associated transfer concept were developed in a project entitled Avoiding Losses in the Food Industry: Research Transfer to SME Practice (German title: “Verluste in der Lebensmittelbranche vermeiden: Forschungstransfer in die KMU-Praxis”) funded by the Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt (German Federal Environmental Foundation) from June 2015 to February 2017. The aim of the case study was to support SMEs in the German food sector, including producers, retailers, and the hospitality sector, in combating food waste with the help of an online platform, which systematizes preselected tools from academia, industry, or other institutions, according to users’ needs. Moreover, the LAV platform is intended to serve as a role model internationally for similar tool gathering platforms that also seek to support domestic SMEs in their food waste reduction efforts by gathering, preselecting, and structuring the tools that are most relevant in their countries. In order to reach this aim, the research team set up and carried out a marketing campaign for the LAV platform, and used the outcomes to develop the marketing campaign guide discussed in Phase III. The campaign included both the development of the online platform and the development of the transfer concept, which meant that the platform would reach the widest possible audience within the target group. The campaign was based on the findings of Phase I (see Section 4) and made use of a multiple-methods approach, which allowed the target audience to participate as project partners from the food sector (SMEs from the food industry, the hospitality sector and multiplier organizations). Table 2 summarizes the steps of the marketing campaign, the project partners, and the reasons for their participation. The limited project budget did not allow the conducting of market research with a large and representative number of SMEs from all segments of the food industry. Therefore, the iSuN decided to rely on qualitative results provided by a smaller number of SMEs. In order to deliver such qualitative data, the partners were required to intensely work with the iSuN (attend meetings, fill in surveys, test the prototype, and act as experts in interviews). For this reason, the majority of project partners were acquired from the existing network of the iSuN. To develop the transfer concept, the research team also obtained interview partners via telephone, which made it possible to connect with industry opinion leaders and SMEs from all respective segments. The number of participating SMEs and opinion leaders was not representative of the whole sector. However, the basis of the cooperation guaranteed commitment from the partners, so qualitative in-depth information could nonetheless be obtained in accordance with the project duration and budget.

Table 2.

Partners involved in the marketing campaign, the reasons for their participation, and results obtained.

5.1. Methods Applied in the Case Study

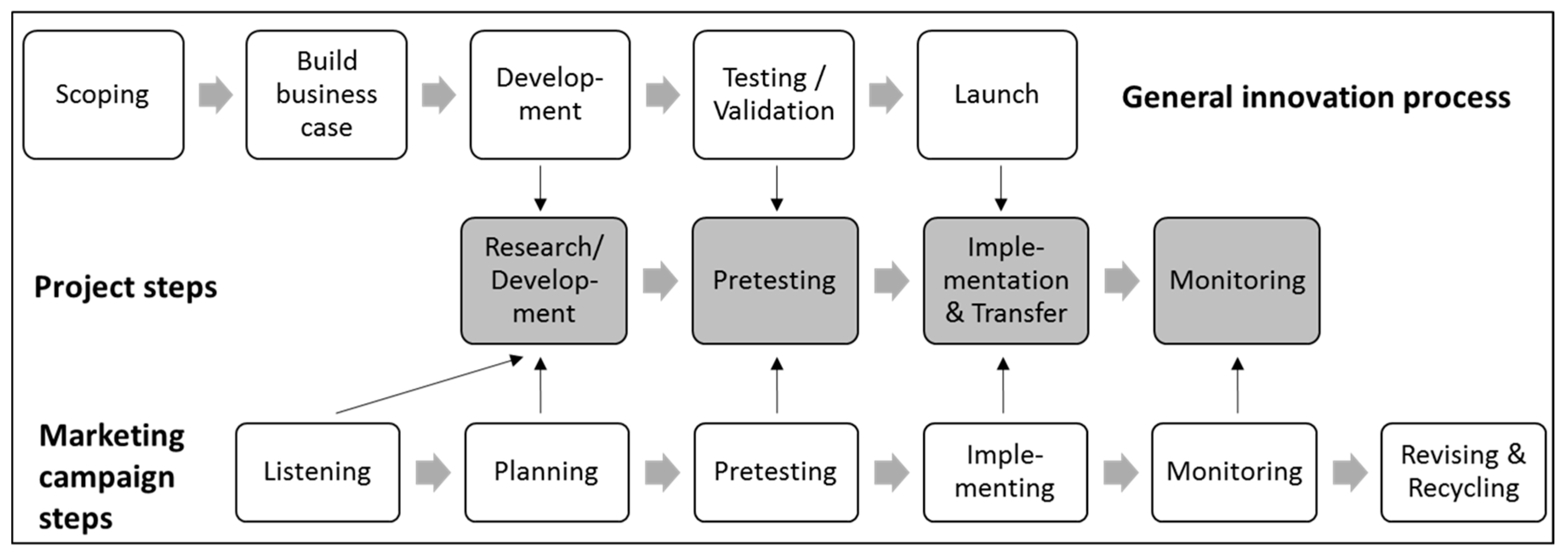

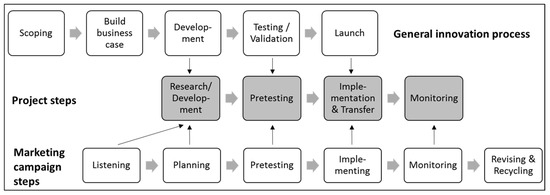

The project was subdivided into four steps: Research and Development, Pretesting, Implementation and Transfer, and Monitoring. As illustrated in Figure 3, these steps were derived from the general innovation process [33] and the marketing campaign steps [25] introduced in Section 4. Table 1 (see case study row) summarizes the aims of each step and the methods applied. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the needs and wants of the target audience, the case study applied a multiple methods approach, which focused on the participation of the target audience. The approach also integrated key stakeholders, such as sector-specific guilds and trade associations, consultants, and representatives of existing networks (see Table 2). Since the project budget did not allow the conduct of market research with a large number of organizations, the authors decided to intensely work with a limited number of partners. These were acquired from the existing partnership network of the iSuN. Although the number of participants in each project step was not representative for the whole food sector, this approach nevertheless delivered valuable information as inputs for the various development and evaluation steps of the case study.

Figure 3.

Derivation of the project steps based on the general innovation process [33] and the steps of a marketing campaign [25] (context of the case study: steps with gray-colored background).

5.2. Implementation of the Case Study

This section presents the implementation of the four project steps noted above: Research and Development, Pretesting, Implementation and Transfer, and Monitoring (see Figure 3).

5.2.1. Research and Development

The aim of this step was to determine how the online platform should be designed to reach maximum acceptance by the target group and how it should be promoted to achieve maximum visibility. The following paragraphs describe the five tasks/milestones which were set to develop the prototype of the platform and to derive a transfer concept during Research and Development.

The first task/milestone of this step to gather all existing tools that support the prevention of food waste and that are freely available on the Internet in the German or English language. Using a combination of online and desk research, a total of 576 tools [34] were found. These included tools such as waste and cost calculators, measuring tools, demand planning tools, training for staff, analysis tools, audit planning aids, best practices, checklists, manuals, guides for food waste reduction, infographics, cost-control systems, and webinars. By using a clustering technique, the tools were categorized by the following goals: analysis and planning, raising awareness, measuring and monitoring, procedures, and benchmarks and best practices; and by the following sectors: meat and fish, dairy, bread and bakery, fruits and vegetables, other producers, retail, restaurants, and public catering. Depending on its content, a tool could be assigned to one or more categories or sectors.

The second task/milestone of this step was to finalize specifications of a prototype for the online platform regarding layout, structure, function, and content, and based on the needs of SMEs. These needs were defined and refined in a workshop held with the project partners by applying methods consisting of brainwriting, clustering, and group discussions. Based on the information obtained, the prototype specifications were based on the following needs:

- Customized content for different target groups (producers, which were further classified according to sector meat and fish, dairy, bread and bakery, fruits and vegetables, and other producers; the retail sector; and the hospitality sector, divided into restaurants and public catering).

- Specific target-group language addressing the management and top staff of companies (i.e., avoiding scientific jargon).

- User-friendly navigation with visual aids, which allows for a simple and efficient search for results.

- A clear structure to reduce the complexity of the information provided (categorization of tools according to topic analysis and planning, raising awareness, measuring and monitoring, measures, and benchmarks and best practices as well as by target group). This allows the platform to specifically offer the target group only those solutions they require from the toolbox. In order to achieve this goal, the main navigation should be structured according to the different stages of the supply chain (producers, retail, and the hospitality sector) and the different sectors for each stage. For example, this ensures that a baker will only be shown tools applicable for bakers and that caterers will find only tools useful for caterers.

The third task/milestone of this step was determining a viable way to minimize the large number of tools compiled in the system in an effort to reduce complexity and provide only the most practical tools to the partners. The challenge involved in this step was to preselect those tools that could easily be applied in practice, and that would offer a real benefit to companies. Therefore, the project team and the partners from the food sector jointly developed a tool-selection procedure that every tool had to undergo [35]. This procedure is a utility analysis and resulted in a ranking of the tools. The procedure involved three steps. First, the team of researchers assessed the content of each tool; tools targeting a goal other than those mentioned above were excluded from the list (e.g., tools aiming at the reuse of food waste as an energy substrate rather than at its prevention). Second, a utility value was calculated for each tool. The utility value was based on an evaluation of eight criteria, each of which was assigned a different importance (see Table 3). The criteria and their weighting were determined by surveying the project partners (web-based survey with nine closed questions). The criteria were: (1) German language; (2) structure and design; (3) time required to understand the tool; (4) applicability of the tool by management only or also by other staff; (5) cost of the tool; (6) necessity to register to use the tool; (7) usability of the tool in a printed format; and (8) industry specificity of the tool. The importance values total 100%. Table 3 provides an overview of the criteria and the importance assigned to each criterion. For each criterion, a rating scale was set up according to which all the tools were assessed. From this assessment, a final utility value was calculated for each tool. Tools that fell below a predetermined cut-off value of 35% were excluded from the toolbox.

Table 3.

Evaluation criteria for assessment of tools and importance values (%) (modified from [35]).

In the third step of the preselection, the remaining tools were ranked in descending order of their utility value for each navigation path, and all tools ranked 16th place or lower were omitted from the toolbox. An exception was made if more than 15 tools were assigned the same utility value. In this case, more than 15 tools per navigation path were kept in the toolbox (see Hospitality Sector in Table 4). By applying the tool-selection procedure for all the tools gathered, the number of tools selected was reduced from 576 to 166 [36].

Table 4.

Key factors supporting and inhibiting the transfer of information to the target group of SMEs in the food industry and the hospitality sector (modified from [38]).

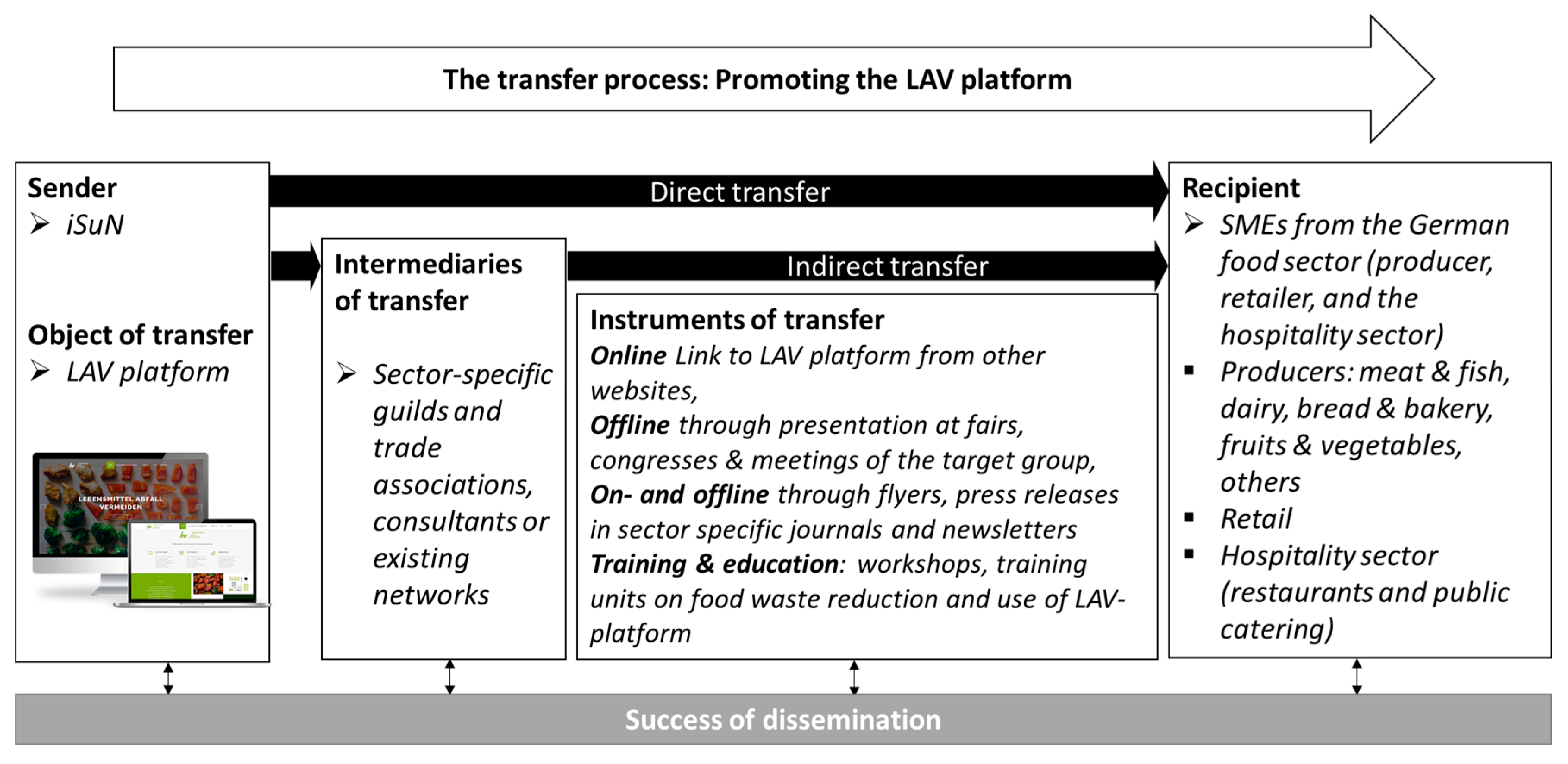

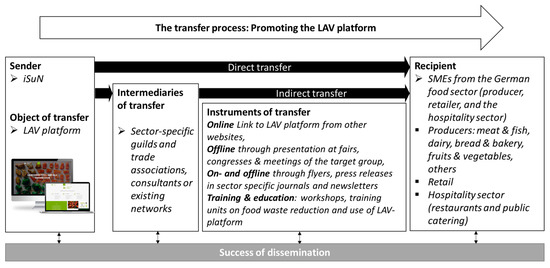

The first result of the research and development step was a prototype of the LAV platform that was developed by an expert web designer based on the aforementioned specifications developed with the project partners. These included information regarding structure, layout, and content, which were obtained using the participation methods during the development step. The toolbox implemented on the prototype platform included the reduced set of tools that remained after the assessment. The fourth task/milestone referred to promoting the platform to the target group. It meant final determination of the transfer channels, as well as the supporting and inhibiting factors of transfer. The process of transfer is presented in Figure 4. It shows the LAV platform as the object which must be transferred from the sender (iSuN) to the recipient. The recipient is represented by the target group of the LAV platform, consisting of SMEs from the various industrial sectors. Figure 4 demonstrates that the transfer process, i.e., promoting the LAV platform, can either work as direct or indirect transfer. The latter makes use of a third actor, intermediaries, who may be involved in the transfer process to increase the success of the dissemination process. The instruments of transfer describe the specific ways that are used to disseminate the information either directly from the iSuN to the target group or indirectly via intermediaries. As opposed to the specific instruments of transfer, the transfer channels describe the general method applied to disseminate the information. For example, the Internet is a transfer channel, while setting up a link is an instrument of transfer.

Figure 4.

Process of knowledge transfer adapted to the case of promoting the LAV platform (Source: the authors, based on [37,38,39]). iSuN: Institute of Sustainable Nutrition.

The transfer channels applied to the target group were analyzed by conducting guided interviews with experts from companies and multiplier organizations. From the interviews, the research team was able to obtain crucial information on transfer channels used in the different sectors and on key factors that would support or inhibit the transfer of information. This information made it possible to set up the transfer concept.

In order to determine the best transfer channels and instruments to use, 35 guided interviews were conducted with experts from SMEs (24) and from multiplier organizations (11) [37,38,40]. These interviews resulted in detailed information regarding the transfer channels that should be used for the different sectors. The information should either be disseminated directly through the iSuN or via intermediaries such as the various multiplier organizations that play vital roles in their particular sectors. The interviewees suggested using the following channels to advertise the platform: Multiplier organizations, such as sector-specific guilds and trade associations, as well as consultants and existing networks should be contacted to disseminate general information on the LAV platform through their newsletters and on their website. In order to facilitate access to the platform, they should also provide a link on their own websites. Moreover, the iSuN should offer training classes regarding the platform and the topic of food waste in the training seminars that sector-specific associations provide and in seminars by educational institutions that offer workshops for different sectors (e.g., vocational schools). The iSuN should also directly advertise the platform by email or phone. The interviewees also suggested that the trade press and magazines should issue a press release about the LAV platform both online and offline, and the iSuN should provide press releases to local newspapers and other local media as well. Moreover, the iSuN should promote the platform at segment-specific exhibitions and directly contact companies in the target group to benefit from word-of-mouth advertising among companies. Furthermore, the iSuN should integrate public institutions that have an interest in the topic of food waste reduction into the concept as multiplier organizations to spread information about the platform via their communication channels.

These potential communication channels were assessed with regard to the key factors supporting and inhibiting the transfer of information, which were also determined from the interviews. These aspects are summarized in Table 4.

The fifth task/milestone was the development of the transfer concept, in which the most promising transfer channels and transfer instruments were utilized. The integration of several sector-specific multiplier organizations as intermediaries of the transfer process turned out to be highly important for the transfer. The multiplier organizations had a key role in disseminating news throughout the sectors, because they are trusted as transmitters of reliable information and knowledge. For this reason, several tools for the transfer were developed which make use of the communication structures opinion makers have, such as using their newsletters for press releases, presenting the LAV platform in meetings, and offering training lessons in seminars given by the different organizations. Due to the central role, these influential actors play, however, it was also important to convince them of the benefits that the LAV platform provides. This task was also integrated into the transfer concept as a major task to fulfill.

5.2.2. Pretesting

The project partners assessed the prototype of the LAV platform according to an evaluation concept that the research team and the partners developed together. With this concept, the partners were able to assess their satisfaction with the prototype of the platform and to what extent they determined the platform to be effective in providing useful tools to minimize food waste. The evaluation concept was subdivided into three parts. The first two were executed as web-based surveys (including closed-end and open questions). In the introductory part of each survey, the participants had to assign their organization to the respective segment of the food sector, to ensure that the results could be attributed to the correct target segments. In the third part, the partners actually had to use the platform to set up their individual food waste reduction program; they were then subsequently interviewed (guided expert interviews) to evaluate the platform’s user-friendliness. Before sending it out to the partners, the research team carried out a pretest with one partner in order to optimize its comprehensibility.

In the first survey, the questionnaire was submitted to 18 project partners (SMEs and multiplier organizations) and 68 other representatives of SMEs, who took part in a workshop related to food waste reduction conducted by the iSuN. The prototype of the LAV platform was presented to the participants and they were requested to fill in the survey. A total of 63 provided feedback on the platform’s design, structure, and layout, and made suggestions for further improvements. The respondents evaluated their first impression and the visual appearance of the platform, the effectiveness of the structure and the navigation paths, the comprehensibility of texts and explanations, and the usefulness of the other features integrated into the platform. The second part of the evaluation concept was content-related. It specifically dealt with the content of the tools provided in the toolbox of the platform and with the topics addressed by the tools, which were analysis and planning, raising awareness, measuring and monitoring, measures, and benchmarks and best practices. This part was also carried out as a web-based survey submitted to 18 project partners and was completed by 14 respondents.

Based on the results of the first two surveys, opportunities for improvement were derived and implemented into the LAV platform. After improving the platform based on the results of the evaluation, the revised version of the LAV platform was actually put into use by the project partners. This was the third part of the evaluation concept. The participating partners had to set up and execute their own individual food waste reduction programs. They determined their individual goals and chose tools from the platform to apply to their company-specific food waste reduction program. These partners compiled a catalogue, which summarized which measures to implement, the time schedule, and the person(s) in charge. After that, the participating partners provided feedback regarding the effectiveness of the LAV platform and the tools tested. The partners were interviewed by the researchers (guided expert interviews by phone). Based on the feedback of seven participating companies, the LAV platform was then optimized further. All respondents stated that their specific food waste reduction programs led to an increased awareness of the topic of food waste in their organizations. One caterer decided to reduce portion sizes as their measurement (a tally sheet counting plates with food residues) revealed that a large amount of side dishes were wasted. A bakery revised its ordering system to better adapt its production to actual demand. Table 5 presents an example of a food waste reduction program set up by one catering company.

Table 5.

Example of a catalogue of measures applied in a catering company.

While the individual goals of the implementation phase varied among the partners, most companies stated that they wished to raise awareness about the topic of food waste. None of the companies announced any objective to reduce food waste by a fixed percentage.

The additional feedback given by the partners revealed that minor layout changes were necessary. Moreover, some of the companies wished to have German translations of tools that had been only provided in English. As a result, 13 tools were translated into German.

5.2.3. Implementation and Transfer

After optimizing the LAV platform, it was finally published [36]. The user navigates through the platform by choosing a sector (producer, retail, or hospitality sector) first. Second, the user selects the requested tool category (analysis and planning, raising awareness, measuring and monitoring, procedures, and benchmarks and best practices) by clicking on the respective tabs of the toolbox, and third, the user chooses among the tools offered. The numbers in Table 6 represent the number of tools available in the toolbox of the LAV platform. Each number also stands for one navigation path on the platform. For example, there are nine analysis and planning tools available for a producer in the fruits and vegetable sector.

Table 6.

Final number of tools per navigation path implemented on the LAV platform.

At the same time, when the platform was published, the transfer concept was put into practice. Segment-specific press releases were sent to multiplier organizations to disseminate this information via their newsletters. Further, the LAV platform was presented at scientific conferences, at symposia of the target audience, and to political organizations (in roundtable discussions, workshops, etc.).

5.2.4. Monitoring

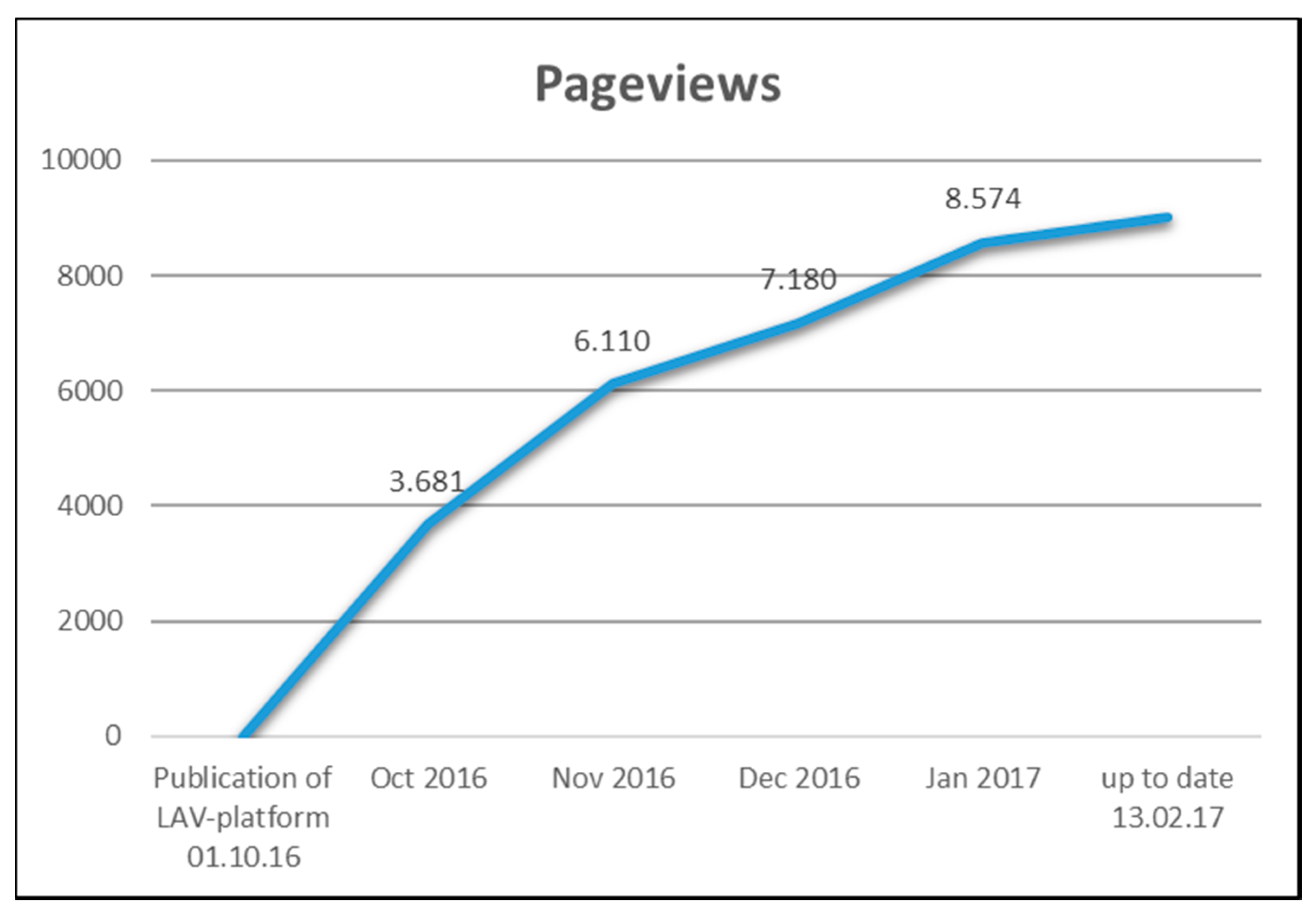

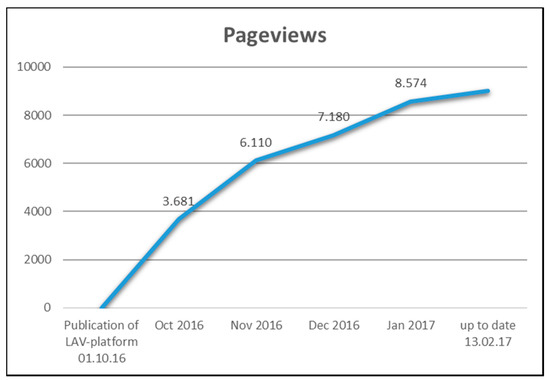

The aim of this step was to determine if the LAV platform was successful and if the transfer concept raised awareness among members of the target audience. Due to the limited project time, monitoring actions were reduced to a limited set of activities. First, website traffic was monitored once the LAV platform went online, on 1 October 2016 (see Figure 5). As the graph shows, in October and November 2016, the first two months after its publication, when the transfer activities were started, the number of viewers rose to 6110. By 13 February 2017, the number had risen further to a total of 9016 views. The bounce rate, which determines how many visitors leave a website directly from the entrance page, was 7.6%, which means 92.4% of the visitors clicked further on the site. On average, they visited 2.9 pages.

Figure 5.

Pageviews of the LAV platform [36] from 1 October 2016 to 13 February 2017.

Due to the limited time of the project, surveying a large number of SMEs from the target group in order to assess whether the LAV platform was successful was not possible. Instead, the 18 project partners (six multiplier organizations and 12 SMEs) were ultimately requested to assess the performance of the LAV platform and the cooperation of the project. This final evaluation was answered by nine participants who assessed three categories. First, they rated the overall performance of the platform as a 1.6 (on a six-point scale with 1 being best, in analogy to German school grades). In the second category, they had to assess to what extent they considered the platform to be a useful tool for preventing food waste in their own organization. Their average rating on a nine-point scale (with 9 being best) was 7.2. In the last category, they evaluated their cooperation with the iSuN in the project. The average rating achieved was 7.3 on a nine-point scale (with 9 being best).

5.3. Conclusions Drawn from the Case Study

The case study to develop and disseminate the LAV platform provided valuable experience from the transdisciplinary working environment, which included iSuN as the project leader, as well as up to 11 multiplier organizations, 12 SME project partners, and up to 68 other SMEs (who took part in online surveys or who were involved as experts in guided expert interviews) from different segments of the food sector. The SMEs and the multiplier organizations were integrated in various participatory methods applied during the project to help the research team understand the needs and wants of the target group and better adapt the LAV platform to their requirements. In addition, SMEs delivered information regarding the transfer of the platform to the food sector. The following conclusions were drawn from the case study:

- SMEs are interested in fighting food waste. Their motivation is based on economic considerations.

- SME project partners have the will to participate. However, they have few time resources. Surveys were often only filled in by the contact person after sending a reminder or after personal communication via telephone. Moreover, guided expert interviews revealed more detailed information on opportunities for improvement than structured surveys.

- Personal communication with the contact person via telephone is important to establish a level of trust and to increase the commitment of partners.

- SMEs have limited time resources and consider additional consulting services useful to counteract food waste.

- Participatory methods are useful for gaining information on the needs of the target group. The research uncovered information on: (a) the functionality, layout and design of the platform; (b) the required content of the toolbox; (c) the required segmentation of the food sector; and (d) the transfer channels applied by the segments.

- Each segment of the target group wants to be addressed separately. General solutions are perceived as providing less benefit than segment-specific solutions.

- Pretesting of the platform is useful for receiving feedback on further opportunities for optimization (e.g., SMEs wished to have more tools in the German language).

- The promotional activities determined in the transfer concept lead to an increased awareness of the platform.

- Evaluating web traffic results in valuable information on the success of the transfer concept.

- The integration of multiplier organizations in the transfer process is useful, as they are perceived by the target group as a reliable provider of information.

6. Phase III: A Marketing Campaign Guide for Nonprofits Targeting the Development and Promotion of Support Tools for the Food Sector

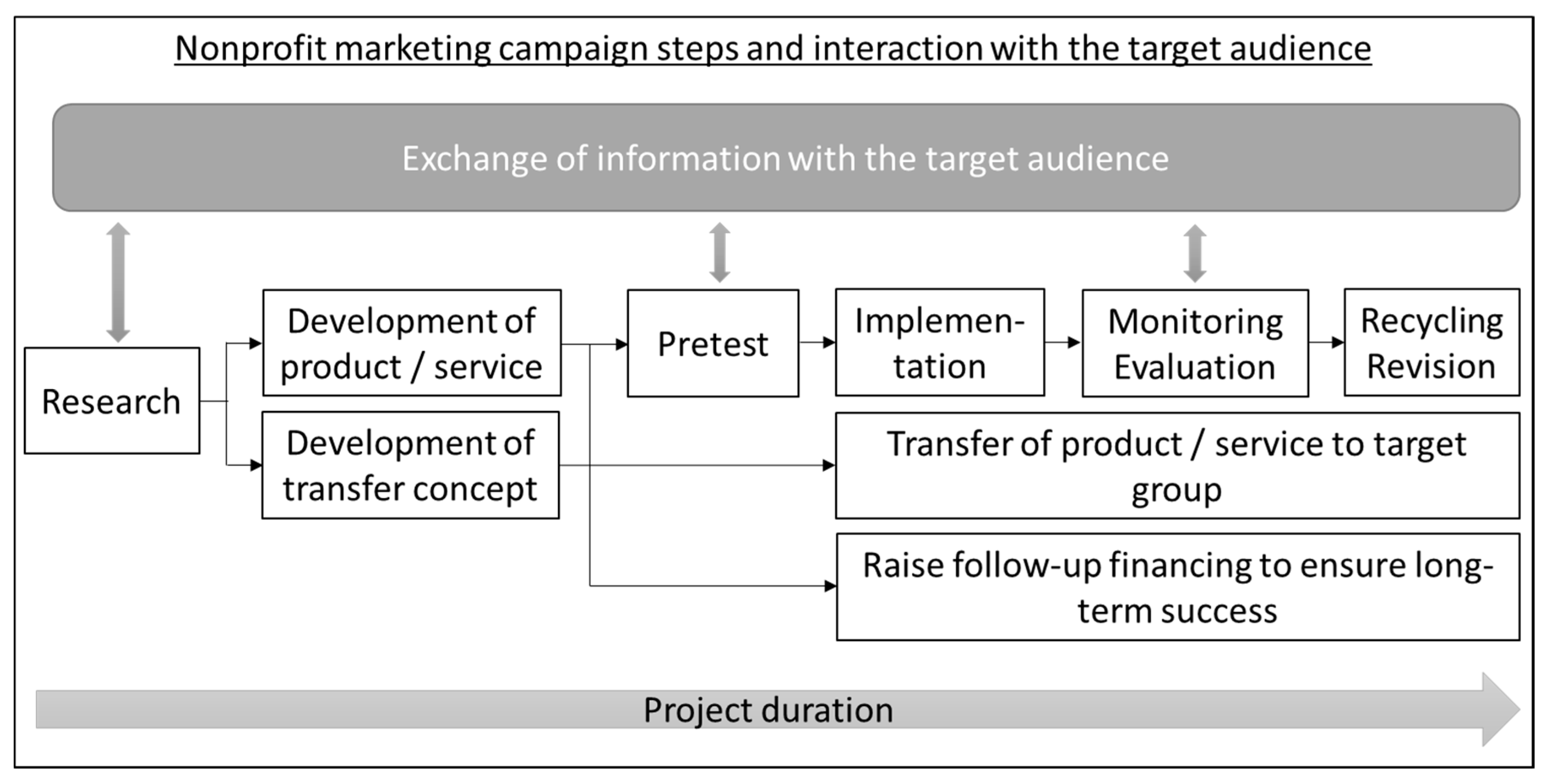

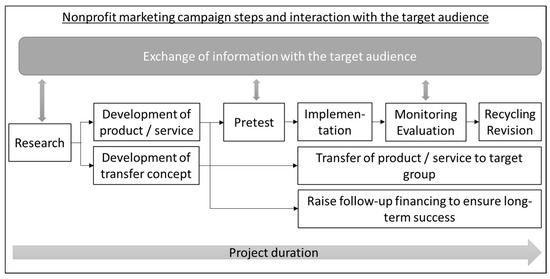

This section takes the results of the research project and uses them to develop a marketing campaign guide that enables nonprofits (e.g., research institutes or governmental agencies) to successfully develop and transfer their offerings, e.g., support tools, to SMEs in the food sector. This guide is based on the marketing considerations summarized in Section 4 and the conclusions drawn from the case study in Section 5. A marketing campaign plan describes how organizational strategies are translated into specific projects [25]. An effective marketing campaign consistently maintains its focus on the target audience. Andreasen and Kotler [25] describe six steps of a marketing campaign: Conducting formative research to understand the target audience, planning, pretesting, implementing, routine performance monitoring, and recycling and revision. Based on the experiences gained from the case study, the authors suggest adjusting Andreasen and Kotler’s [25] campaign for the specific purpose of developing and transferring support tools for the food sector as is illustrated in Figure 6. This procedure specifically emphasizes the importance of the transfer step and includes the additional step of raising follow-up financing. Transfer follows development, in which not only the offering itself is developed, but also the transfer concept (including the appropriate transfer activities). This development is based on the information (transfer channels, supporting and inhibiting factors of transfer) provided by the target audience in the research step. Moreover, the step of raising follow-up financing differentiates between for-profits’ and nonprofits’ campaigns. If nonprofits do not generate a financial surplus that ensures the continuation of their product beyond the project scope, it means they have to start sufficiently early in raising follow-up funding, as part of the marketing campaign itself.

Figure 6.

Nonprofit marketing campaign steps and interaction with the target audience (Source: the authors, based on experiences from the case study (see Section 5) and [25]).

The marketing campaign guide is presented in Table 7. It summarizes the general intention of each step (Intention); with the Meaning paragraphs, the guide specifically describes the meaning of the step for nonprofits that targets market options for SMEs in the food sector. In the Methods part, the authors suggest useful approaches which can be used by nonprofits.

Table 7.

Marketing campaign steps; general intention of each step (based on [25]), meaning for the development of support tools for SMEs in the food sector, and suggested methods for application (based on authors’ experiences).

7. Discussion

At 283,000, the number of SMEs in the food and beverage industry in Europe is enormous. They account for 99.1% of the food and beverage companies in Europe [41]. Competition on the market is high (in Germany, the five biggest food retailers have a market share of more than 70% [42]). Considering this strong competition on the market, SMEs face a situation of high cost pressures, often leading to low staff capacities and time constraints. For this reason, it is important to offer support to such SMEs in their efforts to reduce food waste and to guide them through the jungle of tools freely available on the Internet designed to counteract food waste—currently numbering more than 500 in English or German. Viewed from a marketing perspective, these tools need to take into account the user’s needs and wants in order to be successfully utilized. Moreover, a transfer concept needs to ensure that the user becomes aware of the tools. While in profit-oriented businesses it is common sense that a market and customer orientation are necessary for commercial success, nonprofits still need to work on adopting an audience-centered mindset [27,28,29,31,32]. Based on their experience gained from the case study, the authors agree with Andreasen and Kotler [25], Dolnicar and Lazarevski [26], and Kwak [43] that a clear focus on an organization’s target audience is also crucial for nonprofit projects. In the case study, the LAV platform’s layout and navigation structure as well as the transfer concept were developed in a participatory way and thus they reflect the needs and wants of the target audience. By using this approach, a rating of 1.6 (on a six-point scale, with 1 being best) for overall performance could be obtained. Moreover, the transfer of the platform to the various segments of the target group led to more than 8000 views within the first three months of the platform’s publication. The marketing campaign guide presented by the authors is specifically targeted to nonprofits that wish to develop and market support tools for the food sector. It suggests appropriate methods for each of the marketing campaign steps and explains why these steps are necessary to understand the needs and wants of the target audience. This is especially relevant since nonprofits still often have an organization-centered mindset and managers equate marketing activities to promotional activities [25,26].

On the LAV platform, a large number of efficient tools have been gathered, preselected, and categorized and thus the platform offers valuable support for SMEs in Germany. While platforms presenting tools against food waste for single segments of the food sector or the consumer already exist (see the FoodSave website [44], with its food waste reduction tips for the restaurant sector, LeanPath’s food waste prevention website for commercial kitchens [45], and the consumer-focused campaigns of Love Food Hate Waste campaign by WRAP [46] and “Zu gut für die Tonne”, a German campaign [47]), the LAV platform is the first Internet site internationally that covers the whole food supply chain, from the production of food to its utilization by large-scale consumers, such as restaurants and public caterers. Other food waste reduction initiatives have developed useful tools for special segments of the food sector. For example, WRAP has published more than 100 instruments (e.g., [48,49,50,51,52]) that help companies to reduce the waste of food. Although, the tools are useful, potential users need to search the Internet to find the specific solutions they are looking for. The search time required is an obstacle, especially for SMEs that are often focused on daily work routines. The LAV platform is specific and unique, as it connects supply and demand of food waste reduction tools. Thus far, there has not been a platform that gathers the existing tools to make them available in a structured manner according to the requirements of the different segments of the food sector. Three main advantages differentiate the LAV platform from the platforms published by other initiatives. The LAV platform provides the benefit that: (a) it gathers and preselects those tools which are most efficient for the SMEs, greatly reducing their time required to assess the utility of each individual tool; (b) it addresses all segments of the food sector individually (e.g., bakers can directly find special tools for bakeries; restaurant manager can select those tools specific for restaurants); and (c) the toolbox provided on the platform is structured according to the different goals of the tools (analysis and planning, raising awareness, measuring and monitoring, procedures, and benchmarks and best practices), which further facilitates the search process for SMEs.

The LAV platform can also serve as an example for new tool-gathering platforms in other countries as well. Initiatives that wish to set up their own platform for SMEs can use the marketing campaign guide (see Section 6). The guide specifically focuses on the special requirements of the food sector and describes how nonprofits, such as governmental initiatives or academic projects, can develop and transfer tools by adopting a target audience-centered mindset. The research on existing tools and the tools-selection process that was carried out during the research and development phase of the LAV platform could also deliver valuable inputs for other national or international food waste reduction projects (e.g., the European project REFRESH [53], or the German project REFOWAS [54]).

From an organizational perspective, SMEs also need to have an economic incentive to deal with the topic of food waste. Betz et al. [55] calculated costs for wasted food in two food-service institutions to amount to CHF 170216 (EUR 156303, September 2016) annually; moreover, examples such as four Swedish restaurants which saved EUR 657 (SEK 6030, July 2003) daily [56] and a German hospital whose costs of wasted food accounted for EUR 318000 annually [57] reveal that reducing food waste also makes sense from a monetary perspective. In the future, the financial impact of food waste should be further emphasized on the LAV platform (either in a category of its own or in the benchmarks and best practices category) in order to stimulate managers to commit to food waste-prevention activities.

Although the LAV platform is directed at single SME companies, it supports the development of comprehensive food waste reduction programs, as it gathers tools for all actors of the food supply chain. This is important, as the implementation of inter-organizational measures should not lead to a shifting of food waste further up or down the food supply chain [8]. The platform covers the skilled-labor (such as butchering and baking) and industrial production part of the supply chain, as well as the retail and consumption part with measures for the restaurant and public catering sector. For this reason, it supports a holistic way of thinking in the fight against food waste along the whole food supply chain. This holistic view should also be supported by legal and political authorities. They need to ensure that legal and hygiene requirements become more transparent to lower the barriers for companies to donate excess food. In addition, they should provide further funding for food waste reduction programs in order to facilitate the implementation of food waste reduction concepts for SMEs, which is often hindered by a lack of staffing and time capacities.

The transfer of the platform from its scientific background to the daily work of SMEs in the food industry and hospitality sector contributes to an increased awareness of the topic of food waste. By allowing straightforward access to preselected tools against food waste, the LAV platform can support companies in their food waste reduction activities. The marketing campaign guide provides useful assistance to project managers who wish to develop and transfer support tools for the food sector. As such, both results of this study, the marketing campaign guide and the LAV platform, contribute to achieving United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 12.3, which calls for halving food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reducing food losses along the production and supply chains, which the European Commission has committed to.

8. Conclusions, Limitations and the Need for Further Research

Nonprofits (such as academic research institutes, or governmental initiatives) should apply a systematic marketing approach, such as the one presented by the marketing campaign guide in this article, if they wish to develop and promote a support tool for the food sector. Market research provides valuable information on the needs and wants of a target group. Therefore, it is important to integrate this target audience into the research and pretesting phase to gain insights. It is also important to integrate a pretesting step into the campaign, to raise the tool’s acceptance of the target group and to detect any potential for optimization at an early stage before the tool is transferred to the market. In projects in which limited funding opportunities do not allow large market research campaigns, nonprofits should intensify cooperation with a few key SMEs to receive adequate qualitative information. Guided expert interviews are useful to gather information concerning the requirements of the target group. Monitoring the success of a tool offered and of the promotional activities is also a required step of a marketing campaign. Therefore, appropriate funding for monitoring activities should be raised and sufficient time in the project should be scheduled. For example, for online tools, a monitoring concept for web traffic can be used to analyze if all targeted segments were reached using promotional activities. The requirements of SMEs from different segments of the food sector differ. For example, the skilled-labor sector needs to be addressed differently than retailers, and butchers in a different way than bakers. Hence, it is important to provide target segment-specific solutions rather than generalizing information. This relates to the value proposition of the proposed tool itself, but also to promotional activities. For the latter, transfer channels and transfer instruments applied by each segment of the target group need to be determined. In the food sector, multiplier organizations often play an important role in disseminating information. Therefore, relevant multipliers (e.g., sector-specific guilds and trade associations, consultants, or segment-specific networks) should be integrated into the transfer activities of each segment. The food sector is highly competitive, exerting tremendous cost pressures on SMEs. Therefore, the economic benefits generated by a support tool should be emphasized as an incentive to apply the tool. Moreover, SMEs are confronted with few extra personnel capacities to conduct new projects, such as starting a food waste reduction initiative. Organizations that wish to market a tool to the food sector should consider offering product-service systems that integrate consulting services (with costs) to provide support SMEs in utilizing such tools.

The limitations of this study include the number of SMEs participating in the development and transfer of the LAV platform. Defining the value proposition of the LAV platform and the transfer channels and instruments was only based on a limited number of participants, since the project budget did not allow market research with a more representative number of SMEs. Although the information gained had a qualitative rather than a quantitative character, it nonetheless delivered valuable input for the marketing campaign steps. Another limitation of this study was the limited time to monitor the LAV platform’s success. Success was determined by surveying the limited number of project partners and by analyzing the number of pageviews of the platform. Both the analysis of the platform’s success and the efficiency of the transfer concept could have been more thoroughly developed if there had been more time or funding respectively.

Future research should analyze how the marketing capabilities of nonprofits can be improved further, since an understanding of all actors on the market is crucial for the successful development and transfer of support tools. Future research should also further analyze the potential cost savings applicable for each target segment in order to deliver convincing evidence for management that efforts made to combat food waste pay off. Research should also be conducted on evaluating the effectiveness of tools in respect to their actual food waste reduction potential. This can only be done if standardized methods for the measurement of food waste exist. Therefore, future research should elaborate such methods. Moreover, companies showed great interest in the field of best practices and benchmarks. Future research should therefore also determine key figures specific to each sector to evaluate the occurrence of food waste, which could then be used as the basis for segment-specific benchmarks. This would enable SMEs to evaluate their own position and to reveal further optimization opportunities.

Acknowledgments

The LAV platform and the associated transfer concept were developed in the “Avoiding losses in the food industry: Research transfer to SME practice” project (German title: “Verluste in der Lebensmittelbranche vermeiden: Forschungstransfer in die KMU-Praxis”) funded by the Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt (German Federal Environmental Foundation).

Author Contributions

Silke Friedrich, Christine Göbel and Christina Strotmann conceived the design of this study. Guido Ritter and Judith Kreyenschmidt supervised the work. Christina Strotmann conceptualized the marketing campaign guide and wrote the paper. Fara Flügge and Linda Niepagenkemper conducted the case study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kranert, M.; Hafner, G.; Barabosz, J.; Schneider, F.; Lebersorger, S.; Scherhaufer, S.; Schuller, H.; Leverenz, D. Determination of Discarded Food and Proposals for a Minimization of Food Wastage in Germany: Abridged Version. 2012. University Stuttgart Institute for Sanitary Engineering, Water, Quality and Solid Waste Management (ISWA). Available online: http://www.bmelv.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Food/Studie_Lebensmittelabfaelle_Kurzfassung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources; Summary Report; FAO, 2013; Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3347e/i3347e.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Beretta, C.; Stoessel, F.; Baier, U.; Hellweg, S. Quantifying food losses and the potential for reduction in Switzerland. Waste Manag. Res. 2013, 33, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derqui, B.; Fayos, T.; Fernandez, V. Towards a More Sustainable Food Supply Chain: Opening up Invisible Waste in Food Service. Sustainability 2016, 8, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Strid, I.; Hansson, P. Waste of organic and conventional meat and dairy products—A case study from Swedish retail. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A. Opening the black box of food waste reduction. Food Policy 2014, 46, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A.; Sert, S. Reducing food waste in food manufacturing companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, C.; Langen, N.; Blumenthal, A.; Teitscheid, P.; Ritter, G. Cutting Food Waste through Cooperation along the Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, A.; Clement, J.; Kornum, N.; Bucatariu, C.; Magid, J. Addressing food waste reduction in Denmark. Food Policy 2014, 49, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRAP (Waste and Resources Action Programme). Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Hyde, K.; Smith, A.; Smith, M.; Henningsson, S. The challenge of waste minimisation in the food and drink industry: A demonstration project in East Anglia, UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, D.; Vollmer, A.; Eberle, U.; Fels, J.; Schomerus, T. Entwicklung von Instrumenten zur Vermeidung von Lebensmittelabfällen. 2014. Umweltbundesamt. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/378/dokumente/zusammenfassung_entwicklung_von_instrumenten_zur_vermeidung_von_lebensmitteabfaellen_0.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Katajajuuri, J.; Silvennoinen, K.; Hartikainen, H.; Heikkilä, L.; Reinikainen, A. Food waste in the Finnish food chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreyenschmidt, J.; Albrecht, A.; Braun, C.; Herbert, U.; Mack, M.; Roissant, S.; Ritter, G.; Teitscheid, P.; Ilg, Y. Food Waste in der Fleisch verarbetenden Kette: Um Lebensmittetverluste zu minimieren, sind Handlungen entlang der Kette Fleisch notwendig. Fleischwirtschaft 2013, 93, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, C.; Adenso-Diaz, B.; Yurt, O. The causes of food waste in the supplier-retailer interface: Evidences from the UK and Spain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 2011, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, A.; Bleazard, P.; Okawa, K. Preventing Food Waste: Case Studies of Japan and the United Kingdom; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, 2015; Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5js4w29cf0f7-en (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Parry, A.; James, K.; LeRoux, S. Strategies to Achieve Economic and Environmental Gains by Reducing Food Waste: WRAP (Waste & Resources Action Programme). 2015. Available online: http://newclimateeconomy.report/2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/02/WRAP-NCE_Economic-environmental-gains-food-waste.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Schneider, F. Review of food waste prevention on an international level. Waste Resour. Manag. 2013, 166, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R.; McWilliam, S. Food waste, catering practices and public procurement: A case study of hospital food systems in Wales. Food Policy 2011, 36, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, C.; Göbel, C.; Friedrich, S.; Kreyenschmidt, J.; Ritter, G.; Teitscheid, P. A Participatory Approach to Minimizing Food Waste in the Food Industry—A Manual for Managers. Sustainability 2017, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Kokkinakos, M.; Walton, K. Definitions and causes of hospital food waste. Food Serv. Technol. 2003, 3, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Resources Institute. Available online: http://www.wri.org/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- United against Waste—Gemeinsam Gegen Lebensmittelverschwendung. Available online: http://www.united-against-waste.de/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- EPA National Waste Prevention Programm. Available online: http://www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/waste/stopfoodwaste/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Andreasen, A.R.; Kotler, P.R. Strategic Marketing for Non-Profit Organisations: Pearson New International Edition, 7th ed.; United States Edition; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S.; Lazarevski, K. Marketing in non-profit organizations: an international perspective. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meffert, H.; Burmann, C.; Kirchgeorg, M. Marketing: Grundlagen Marktorientierter Unternehmensführung Konzepte—Instrumente—Praxisbeispiele, 12th ed.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meffert, H.; Bruhn, M.; Hadwich, K. Dienstleistungsmarketing: Grundlagen—Konzepte—Methoden, 8th ed.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C.; Becker, J. Marktorientierte Unternehmensführung und Ihre Erfolgsauswirkungen. Eine Empirische Untersuchung. In Reihe: Wissenschaftliche Arbeitspapiere; Institut für Marktorientierte Unternehmensführung, Mannheim University: Mannheim, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A.; McLoughlin, D. Strategic Market Management; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 12th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vahs, D.; Brem, A. Innovation Management: From ideas to successful implementation. In Innovationsmanagement: Von der Idee zur erfolgreichen Vermarktung; Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.G. How companies are reinventing their idea-to-launch methodologies: Next-generation Stage-Gate systems are proving more flexible, adaptive and scalable. Res. Technol. Manag. 2009, 52, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Institut für Nachhaltige Ernährung (iSuN). Gesamttabelle der Recherchierten Instrumente zur Vermeidung von Lebensmittelabfall innerhalb des Projektes “Verluste in der Lebensmittel-Branche: Forschungstransfer in die KMU-Praxis”. 2016. Available online: http://www.lebensmittel-abfall-vermeiden.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/170123_Gesamttabelle_Instrumente.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Flügge, F. Entwicklung Eines Bewertungskonzeptes für Instrumente zur Vermeidung von Lebensmittelverlusten in der Lebensmittelwirtschaft. Bachelor’s Thesis, Münster University of Applied Sciences, Münster, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Institut für Nachhaltige Ernährung (iSuN). LAV-Plattform: Lebensmittel-Abfall-Vermeiden. Available online: http://www.lebensmittel-abfall-vermeiden.de/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Niepagenkemper, L. Transfer von Forschungsergebnissen in die Praxis: Entwicklung Eines Transferkonzeptes für die Vermeidung von Lebensmittelabfällen in Unternehmen der Außer-Haus-Gastronomie. Master’s Thesis, Münster University of Applied Sciences, Münster, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neuber, K. Entwicklung eines Branchenübergreifenden Transferkonzeptes für die Lebensmittelwirtschaft im Rahmen des Forschungsprojektes “Verluste in der Lebensmittelbranche vermeiden”. Master’s Thesis, Münster University of Applied Sciences, Münster, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Korell, M.; Schat, H. Entwicklung eines Transfermodells. In Transfer von Forschungsergebnissen in Die Industrielle Praxis: Konzepte, Beispiele, Handlungsempfehlungen; Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse des Beispielhaften Transferprojekt ‘Mechatronik’; Fraunhofer Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2013; pp. 12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jaensch, M. Kommunikationsstrukturen in der Lebensmittelwirtschaft am Beispiel der Fleischwarenbranche und der Obst- und Gemüsebranche—Erarbeitung von Empfehlungen für ein Branchenbezogenes Transferkonzept zur Vermeidung von Lebensmittelabfällen in klein- und mittelständischen Unternehmen. Bachelor’s Thesis, Münster University of Applied Sciences, Münster, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- FoodDrinkEurope. Data & Trends European Food and Drink Industry 2014–2015; FoodDrinkEurope: Brussel, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://www.wko.at/Content.Node/branchen/oe/Nahrungs--und-Genussmittelindustrie--Lebensmittelindustrie-/Data_and_Trends_2014-20152.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- BVE. Jahresbericht 2015–2016. Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Ernährungsindustrie. Available online: http://www.bve-online.de/presse/infothek/publikationen-jahresbericht/jahresbericht-2016 (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Kwak, W. Marketing Strategies of Non-Profit Organizations in Light of Value-Based Marketing; Wyższa Szkoła Biznesu—National-Louis University, 2011; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11199/468 (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- FoodSave. Available online: http://www.foodsave.org/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Lean Path: Food Waste Prevention. Available online: http://www.leanpath.com/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Love Food, Hate Waste (United Kingdom). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/prevention/pdf/Lovefoodhatewaste_Factsheet.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Zu gut für die Tonne. Available online: https://www.zugutfuerdietonne.de/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- WRAP (Waste and Resources Action Programme). Tool: diagnostics spreadsheet template: Problem Definition or Diagnostics. 2016. Available online: www.wrap.org.uk/content/problem-definition-spreadsheet-template-v1 (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Secondary Packaging Optimisation: Packaging Waste Prevention—Digest. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/content/food-waste-prevention-digests-secondary-packaging (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Reducing Waste in the Fresh Meat Sector. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Meat_Sector_supply_chain_sheet.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Food Waste Tracking Sheet. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Food_Waste_Tracking_Sheet_v1.1_0_050115.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- WRAP (Waste and Resources Action Programme). Grocery Sector Map: WRAP (Waste and Resources Action Programme). 2014. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Sector%20map%2001%2008%2014.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- REFRESH. Available online: http://eu-refresh.org/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- ReFoWas: Reduce Food Waste. Available online: http://refowas.de/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Betz, A.; Buchli, J.; Göbel, C.; Müller, C. Food waste in the Swiss food service industry—Magnitude and potential for reduction. Waste Manag. 2015, 2015, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engström, R.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Food losses in food service institutions: Examples from Sweden. Food Policy 2004, 29, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitscheid, P.; Strotmann, C.; Blumenthal, A.; Schreiner, L.; Aich, E. Forschungsbericht zum INTERREG Projekt “Nachhaltig Gesund/Duurzaam Gezond”. 2015. Available online: https://www.fh-muenster.de/isun/downloads/studie-lebensmittelverschwendung/Forschungsbericht_NachhaltigGesund_Deutsch_07-05_latest.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2017).

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).