Abstract

Real-time multi-GNSS precise point positioning (PPP) requires the support of high-rate satellite clock corrections. Due to the large number of ambiguity parameters, it is difficult to update clocks at high frequency in real-time for a large reference network. With the increasing number of satellites of multi-GNSS constellations and the number of stations, real-time high-rate clock estimation becomes a big challenge. In this contribution, we propose a decentralized clock estimation (DECE) strategy, in which both undifferenced (UD) and epoch-differenced (ED) mode are implemented but run separately in different computers, and their output clocks are combined in another process to generate a unique product. While redundant UD and/or ED processing lines can be run in offsite computers to improve the robustness, processing lines for different networks can also be included to improve the clock quality. The new strategy is realized based on the Position and Navigation Data Analyst (PANDA) software package and is experimentally validated with about 110 real-time stations for clock estimation by comparison of the estimated clocks and the PPP performance applying estimated clocks. The results of the real-time PPP experiment using 12 global stations show that with the greatly improved computational efficiency, 3.14 cm in horizontal and 5.51 cm in vertical can be achieved using the estimated DECE clock.

1. Introduction

As one of the most popular positioning technologies, precise point positioning (PPP) [1,2] has been widely used thanks to its high accuracy, proficiency, stability, and flexibility [3,4,5]. Recently, with the great progress of global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), the Russian GLONASS, European Galileo, and Chinese BeiDou have increased the number of satellites to more than 80, which will grow to about 120 in 2020. Compared with GPS-only solutions, better performance of PPP with multi-GNSS would be achieved in terms of not only convergence but also accuracy because of the improved satellite geometry due to the increasing number of satellites [6,7,8,9,10]. With the progress in high-speed internet communication and the achievements in the GNSS data stream protocol and format design, i.e., Radio Technical Commission for Maritime (RTCM) and Networked Transport of RTCM via Internet Protocol (NTRIP) [11], great efforts are underway towards the global real-time GNSS precise positioning service, where the real-time high precision satellite orbit and clock product is fundamental [12]. Though the quality of the International GPS Service (IGS) precise clock products have been improved continually since 1994 [13], to provide real-time satellite clocks of high resolution, normally to be updated within five seconds, is still full of challenges. Moreover, the heavy computational burden against the requirement on high update rate and involvement of more stations and multi-constellation satellites is one of the crucial issues.

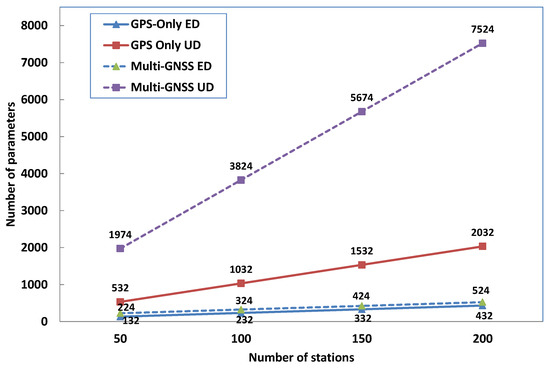

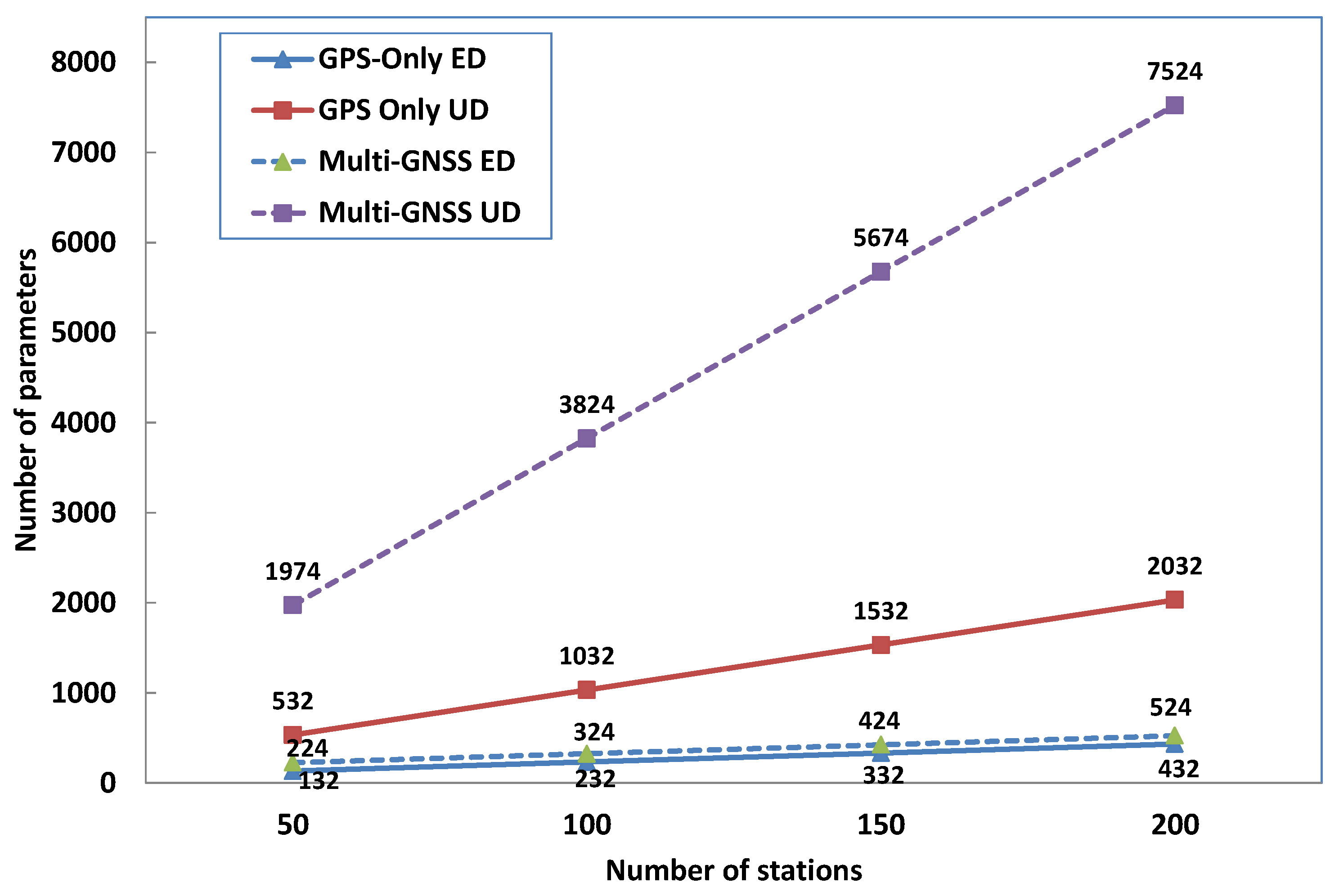

In the typical clock estimation, undifferenced (UD) observations are employed and the computation time depends mainly on the number of estimated ambiguity parameters [14]. Obviously the computation becomes much more time-consuming if more stations are involved for reliable estimation. The task, to update clocks within five seconds, could be fulfilled with difficulty for multi-GNSS clock estimation, with about 80 satellites now and about 120 satellites soon. Furthermore, for such a large linear system, a sophisticated quality control procedure, which must be implemented, also needs significant computation time.

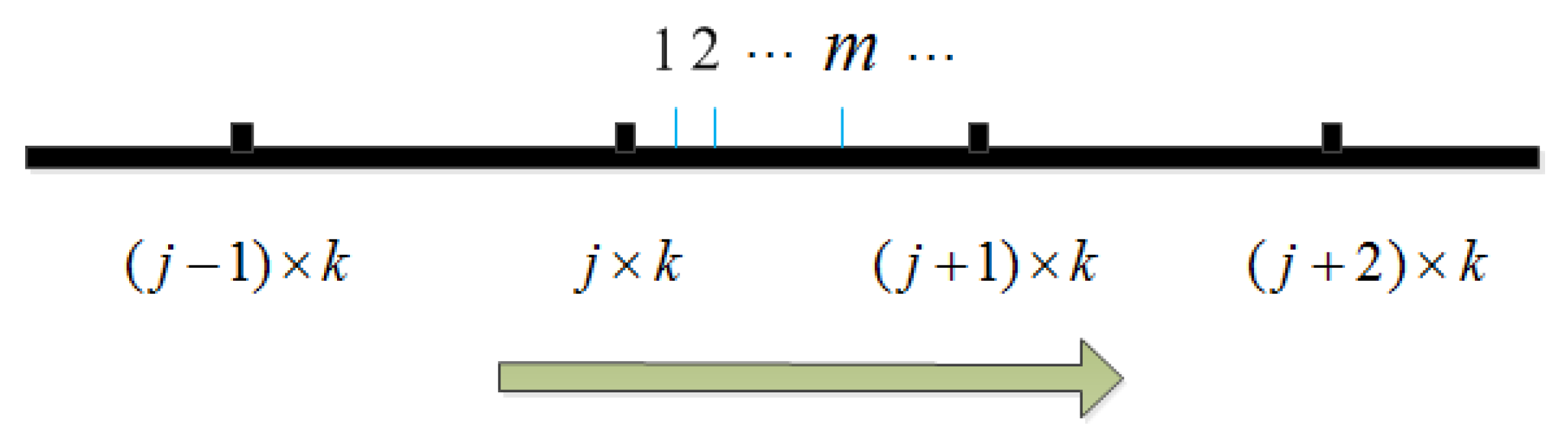

Bock et al. employed epoch-differenced (ED) phase observations to densify CODE’s final clock of 5-min intervals to 1 Hz for special precise applications, in which the 5-min clocks derived by using undifferenced (UD) phase and range observations are fixed as “control points” [15]. Generally, UD provides absolute clocks, while ED generates the high-rate clock change as the majority of parameters, e.g., ambiguities are eliminated and consequently the computation load is significantly reduced. On the same basis, Zhang and Li extended this method for real-time clock estimation with a dual-thread strategy; the UD thread is for the absolute clock estimation with an interval of five seconds, while the ED thread estimates the clock change with an interval of one second [16]. The ED clocks are aligned to the UD ones to generate the final high-rate satellite clocks to meet the requirements of real-time kinematic PPP.

Furthermore, Ge et al. introduced an alternative approach to estimate high-rate real-time satellite clocks using ED phase and UD range observations in a single filter, so that no ambiguities are estimated and clock changes are aligned by range to absolute clocks [17]. The result shows that the approach can achieve a comparable accuracy to that of the UD approach, whereas the computation time is reduced to one tenth. This strategy was also implemented into real-time multi-GNSS clock estimation and evaluated [18,19,20].

At the same time, fast computation approaches optimized according to CPU structure, such as matrix operations, were also skillfully introduced into GNSS data processing in order to improve the computational efficiency [21]. Ambiguity resolution was also implemented to reduce the number of active ambiguities, and consequently, the computation burden for clock estimation [22,23].

Anyway, as discussed above, the mixed-differenced method with UD for absolute clocks and ED for clock variation is one of the most efficient strategies for multi-GNSS clock estimation with large networks, although UD is now widely used. One of the remaining issues is how to combine the UD and ED, integrated into one process as parallel inline processes [16] or even in a single adjustment [17]. Although the theoretical difference is slight, the reliability and robustness of the processing schema are of great concern for providing satellite clocks for real-time operational service. For this purpose, we have to consider the following two aspects. First of all, redundant processing lines are definitely needed and can be deployed either in the same location or offsite, and their outputs can be combined to a unique product for providing reliable service. It will not affect the performance if some of the redundant processing lines are crashed. Second, disturbed processing may be needed if a network cannot be processed in a single adjustment because of too many stations and/or satellites. In fact, along with the development of modern processors and servers, the parallel computing on a distributed framework is receiving increasing interest in scientific computation community.

In this contribution, we develop an alternative processing strategy for multi-GNSS real-time high-rate clock estimation, in which a number of UD and ED processing lines can be involved and their output clocks are combined to generate a unique clock product. The UD and EU lines can be designed for sub-networks or a set of GNSS systems, or duplicated lines for redundancy. They can be deployed and operated independently over different and even offsite computers. Then, the ED and UD clocks are combined with separated software developed by us in a similar way to that done for the combination of analysis center (AC) products at the IGS real-time combination center [24]. As each of the processing lines can be run in different computers, we named it decentralized clock estimation (DECE) in this study.

The processing strategy is realized based on the Position and Navigation Data Analyst (PANDA) software for validation [25,26]. A network of about 110 real-time stations with the tracking capacity of GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou four systems is employed and real-time estimated clocks, as well as the computation time using the UD processing mode and the DECE mode, are compared and the PPP performance is also evaluated.

First, we introduce the current research status for multi-GNSS and real-time clock estimation, and then the multi-GNSS real-time clock estimation model is discussed. In addition, we present the strategy of data processing and the real-time clock estimation system based on PANDA software. The real-time clock product estimated by the DECE strategy is also validated by clock comparison and their application to multi-GNSS PPP. Finally, a summary of the results and corresponding conclusions are given.

3. Decentralized Clock Estimation (DECE)

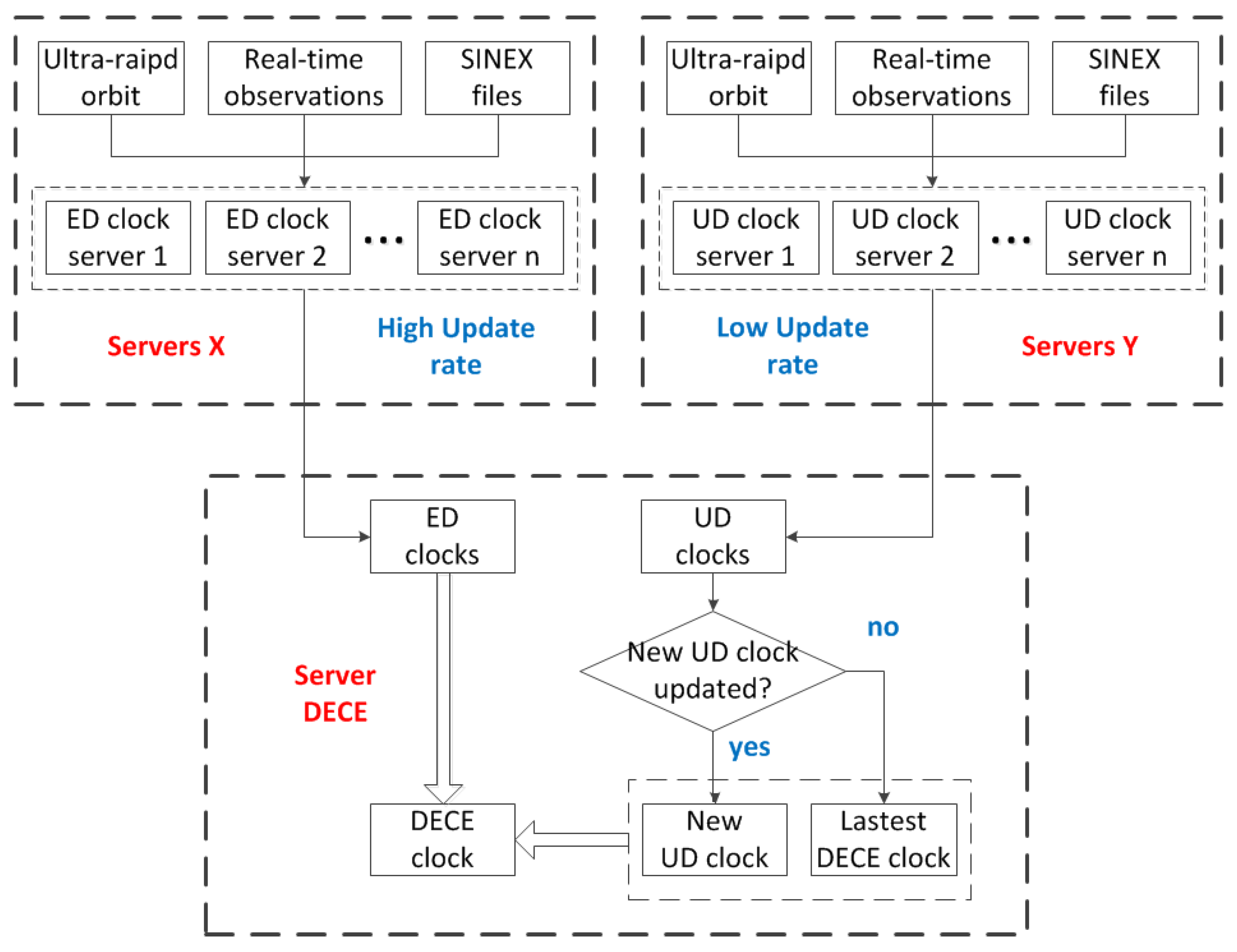

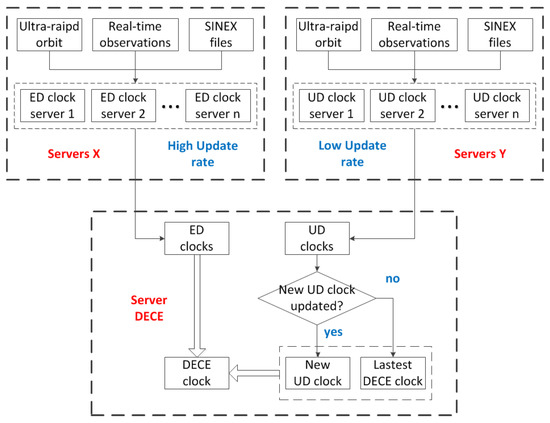

Instead of integrating ED and UD and combination processing in a single process in terms of threads, we propose a decentralized clock estimation mode in which UD, ED, and the combination can be run in separated computers with a network connection. Figure 3 shows a flow chart of the simplest DECE configuration with one UD, and one ED and a combination process each running in a server. Ultra-rapid orbit and real-time observations are needed for each server group and we fix site coordinates to Solution INdependent EXchange (SINEX) format solution [30,31]. Both clock products from the ED and UD processes are transferred to the server where the combination is running to generate the final clock products simultaneously according to Equation (9). It should be noted that the orbit switching on each server is synchronous.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the decentralized clock estimation (DECE) with the basic configuration, i.e., one undifferenced (UD), one epoch-differenced (ED), and one combination process, each running in a server.

One of the advantages of the DECE is that the data exchange among the processes is very small and mainly for transmitting the estimated clocks, and thus can be easily realized through a TCP/UDP port. A much more important advantage is that DECE can significantly improve the robustness of the real-time precise positioning service by running redundant processing processes.

Although only two clock estimation processes are deployed in Figure 3 and used in this study, it can be extended to include more with the same strategy and stations as redundant processing.

Processing processes with different strategies or different station sub-networks can also be involved for using more stations. All the processing processes can be deployed in servers either of a local network or in an offsite network. The combination processes automatically collect the necessary clock estimates according to specified weights to generate a combined product. It is obvious that the robustness of the processing or the availability of the clock products can be dramatically improved by such a distributed system, as the system can always provide high-rate clock product if one of the redundant ED solutions and one of the redundant UD solutions are working well. The crash of the clock combination process is negligible, since it can provide well-qualified combined clocks instantaneously after restarting.

4. Real-Time Experimental Evaluation

In order to validate the DECE strategy, we use the Position and Navigation Data Analyst (PANDA) software package [25,26] as the base, and the real-time estimator is adapted to a distributed environment and a tool for real-time clock combinations developed for the DECE processing. First, we describe the whole data processing of the real-time precise positioning service based on the PANDA software package, and then the network and finally the processing parameters and processing schema used in the validation.

4.1. Data Processing System

In our system, the real-time Precise Orbit Determination (POD) is carried out in batch-processing mode using the observations from MGEX and IGS networks. All parameters in PDO are estimated by least squares adjustment and previous 24-h observations are used to generate the rapid orbit. Then the real-time orbit is predicted based on the rapid orbits in a batch-processing mode by using orbit integrator for at least six hours in a similar way to that of the IGS ultra-rapid data processing. Then the real-time clock estimation processes will do parameter estimation epoch by epoch based on the fixed real-time orbit using the methodology introduced in Section 2.4.

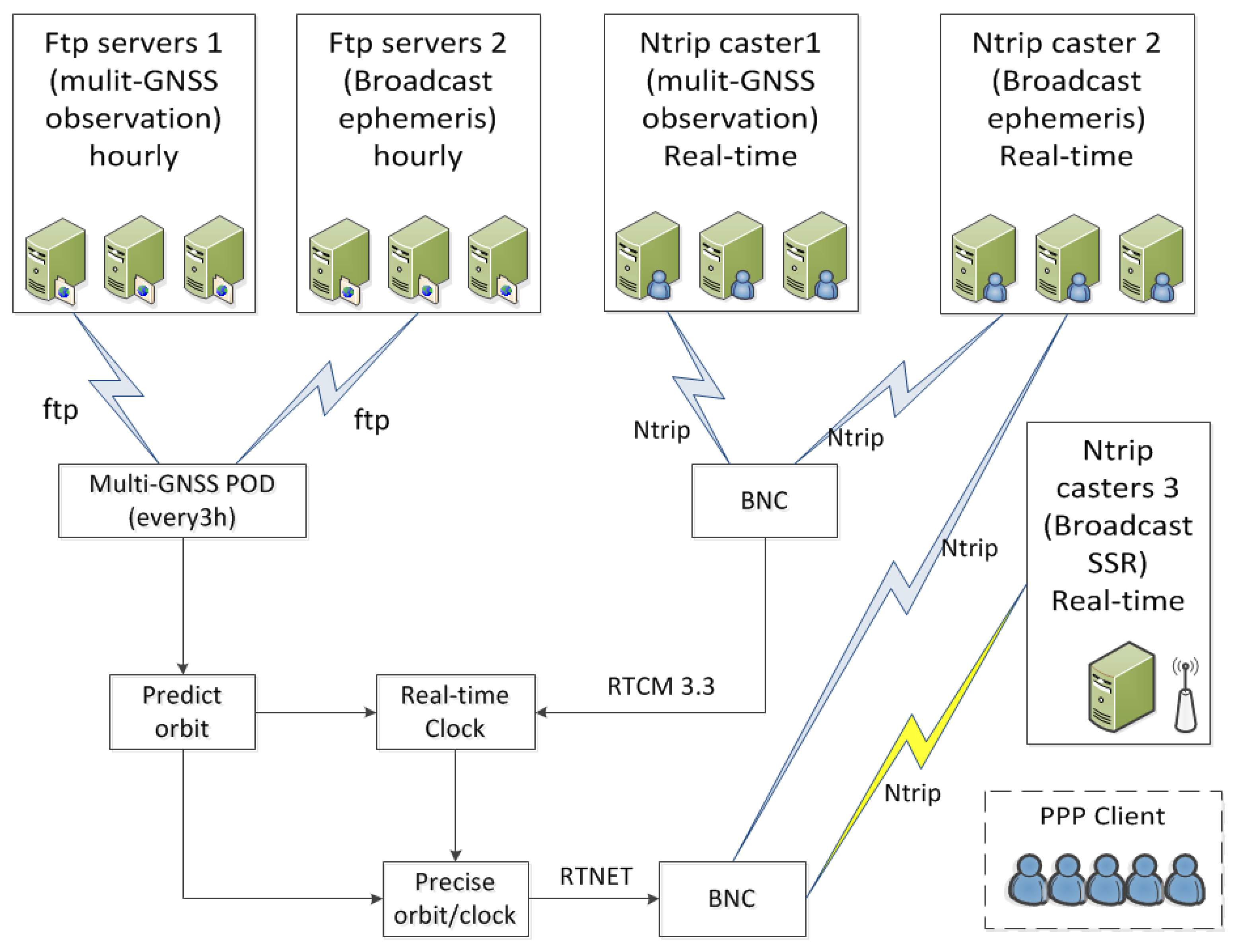

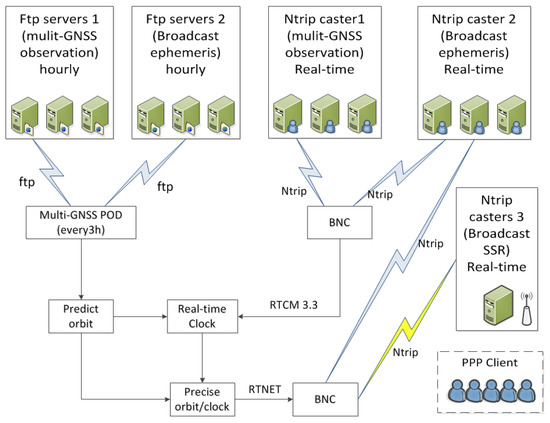

The BKG Ntrip Client (BNC) software (version 2.12) [32] is used to receive real-time observations as well as ephemeris data to feed the filter for clock estimation, and is also used to generate state-space representation corrections from the estimated orbits and clocks. Real-time data are transported using the NTRIP protocol and encoded/decoded following the RTCM 3.3 standard [11]. The structure of all systems is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flow chart of the real-time precise positioning service system based on the Position and Navigation Data Analyst (PANDA) software package.

4.2. Data and Network

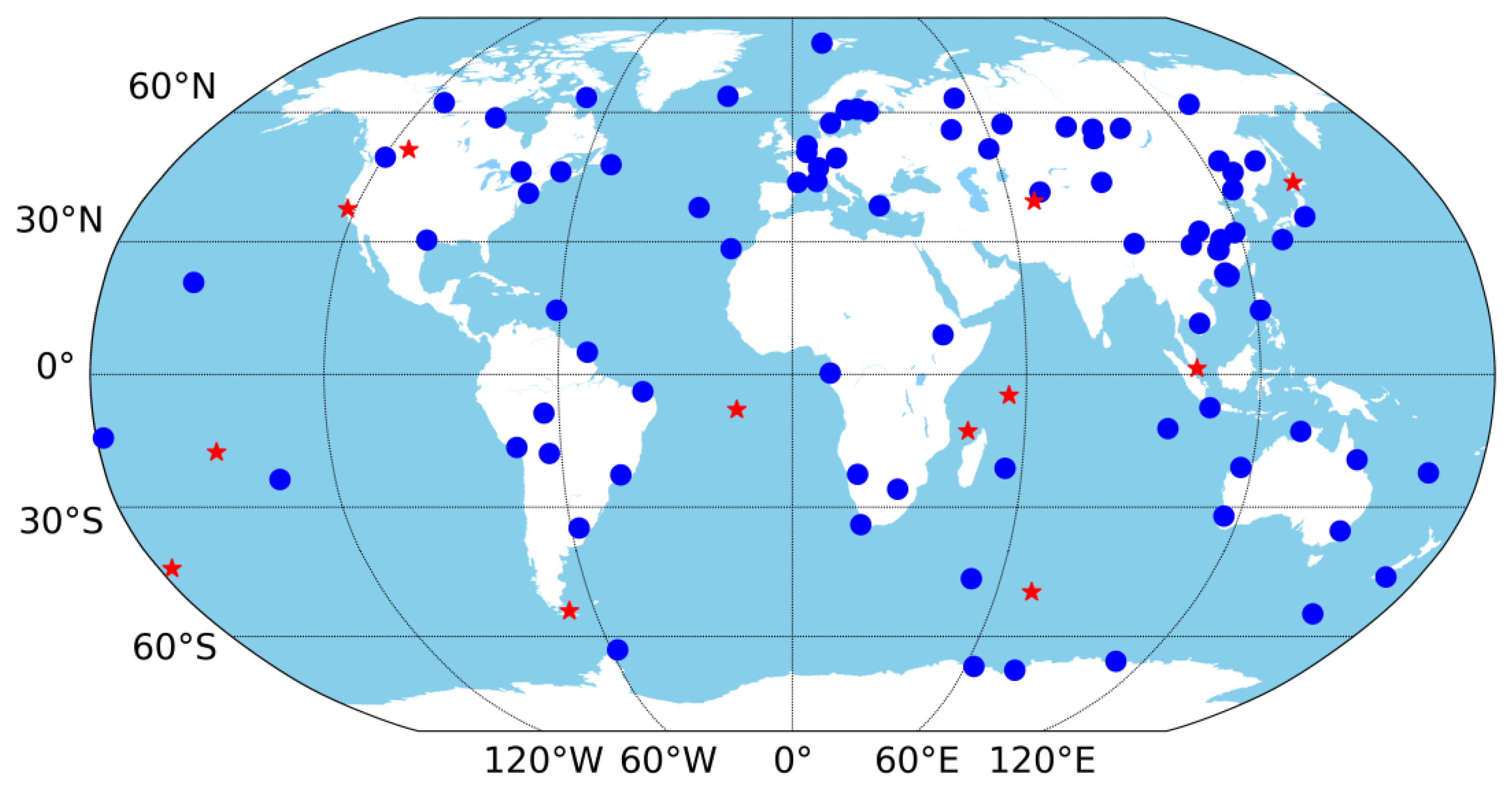

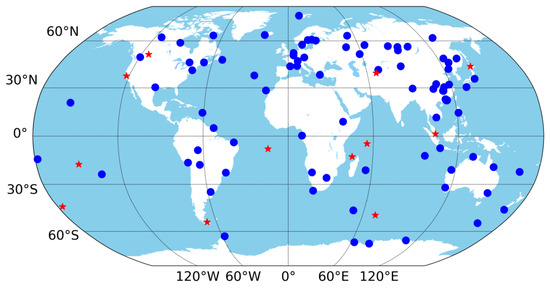

A network of about 110 global multi-GNSS stations is employed in the experiment. All the 110 stations can track GPS signals, while 105, 65, and 83 stations are with GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou tracking capacity, respectively. Most of the real-time observation streams are provided by the International GNSS Service (IGS) and the Multi-GNSS Experiment (MGEX). German Geoscience Research Center (GFZ) and the German Federal Agency for Cartography and Geodesy (BKG) also contributed some multi-GNSS stations. The distribution of the stations is shown in Figure 5. The circle marks are the 110 stations used for clock estimation, while the stars indicate the 12 stations used for real-time PPP test in Section 5.3, which are not included in clock estimation. Because of the network or other reasons, real-time streams are not as stable as the recorded observation files. Normally there are at least 90 stations available for clock estimation.

Figure 5.

Distribution of stations for the Multi-GNSS (global navigation satellite systems) real-time clock estimation marked by cycles and that for precise point positioning (PPP) test by pentagrams.

4.3. Processing Parameters

The data processing parameters are shown in Table 3 and are kept the same for both UD and ED mode if it is not specified. It should be mentioned that there is no official Phase Center Offset (PCO) and Phase Center Variation (PCV) information for Beidou and Galileo satellite and receiver antennas at present, so we use GPS antenna parameters instead.

Table 3.

Observation models involved in clock estimation.

5. Results

The experimental real-time precise positioning service has been run operationally and we take the orbit and DECE clock products from Day of Year (DOY) 274 to 280, 2018 for the validation. In the experiment, we use a 5-s update rate for ED clock estimator and 20 s for UD clock estimator to generate 5 s final DECE clock products. The CPU we used is Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2637 v4 @ 3.50GHz.

5.1. Decentralized Clock Estimation (DECE) Compared to Undifferenced (UD)

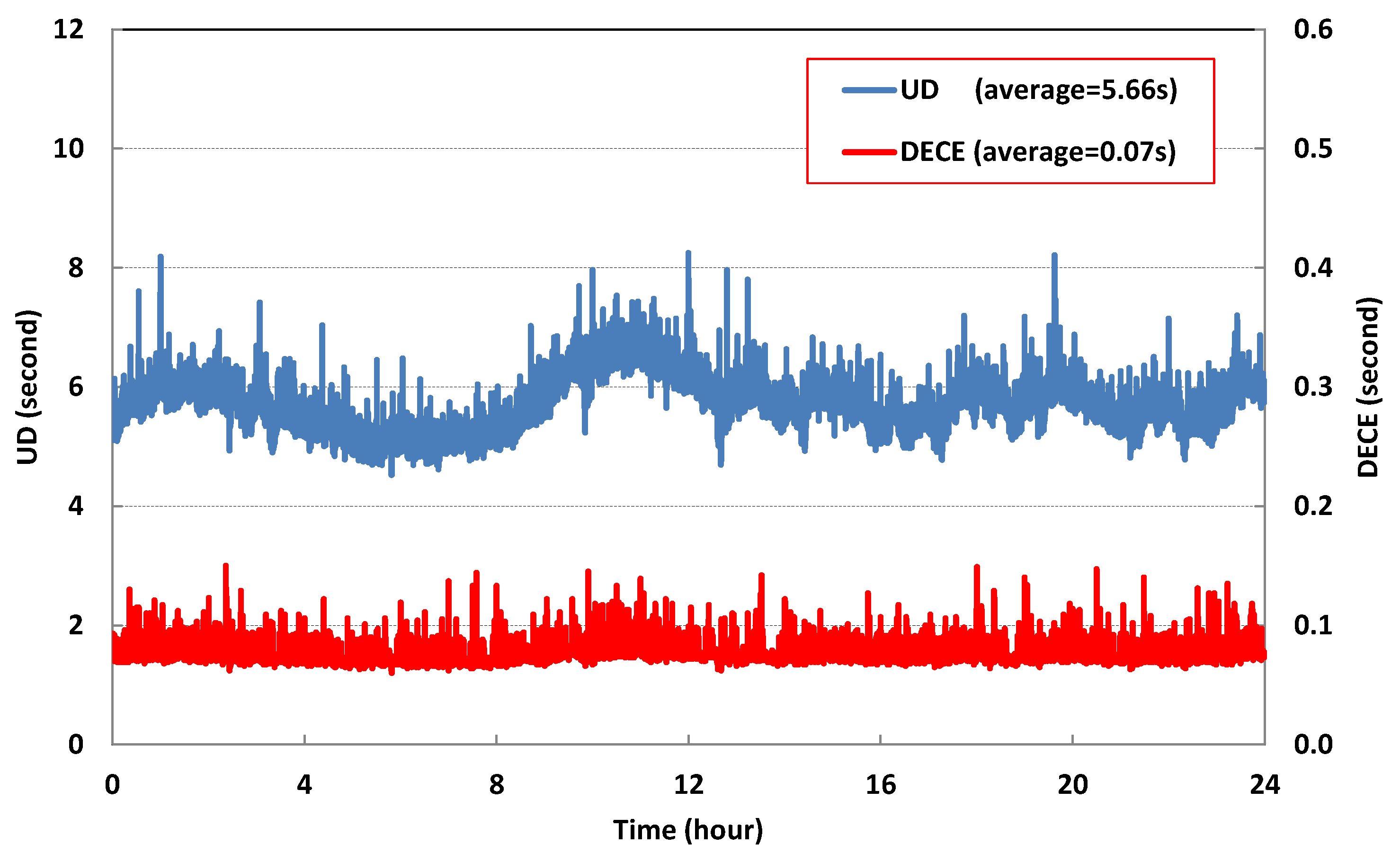

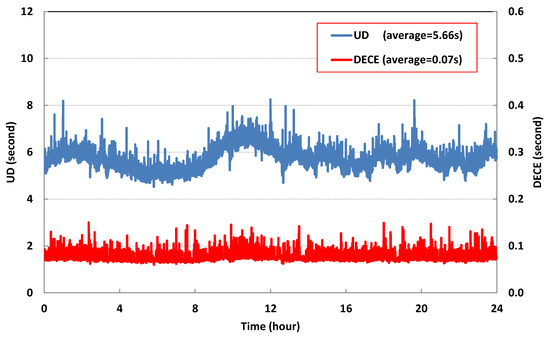

Taking the results of DOY 251 in 2018 as an example, Figure 6 shows the time consumed using UD and DECE at each epoch. The computing time of the DECE is 0.07 s on average, which is much less than that of the UD mode, which is about 5.66 s. It should be noted that it is difficult to update the UD clock within five seconds at each epoch, especially when quality control is involved. What is more, with the completion of Galileo and Beidou in the near future, 124 satellites will be used and the burden of calculation will further increase. On the contrary, the DECE model can solve this computational problem easily.

Figure 6.

Computational time at each epoch using undifferenced (UD) and decentralized clock estimation (DECE) modes for Day of Year (DOY) 251, 2018.

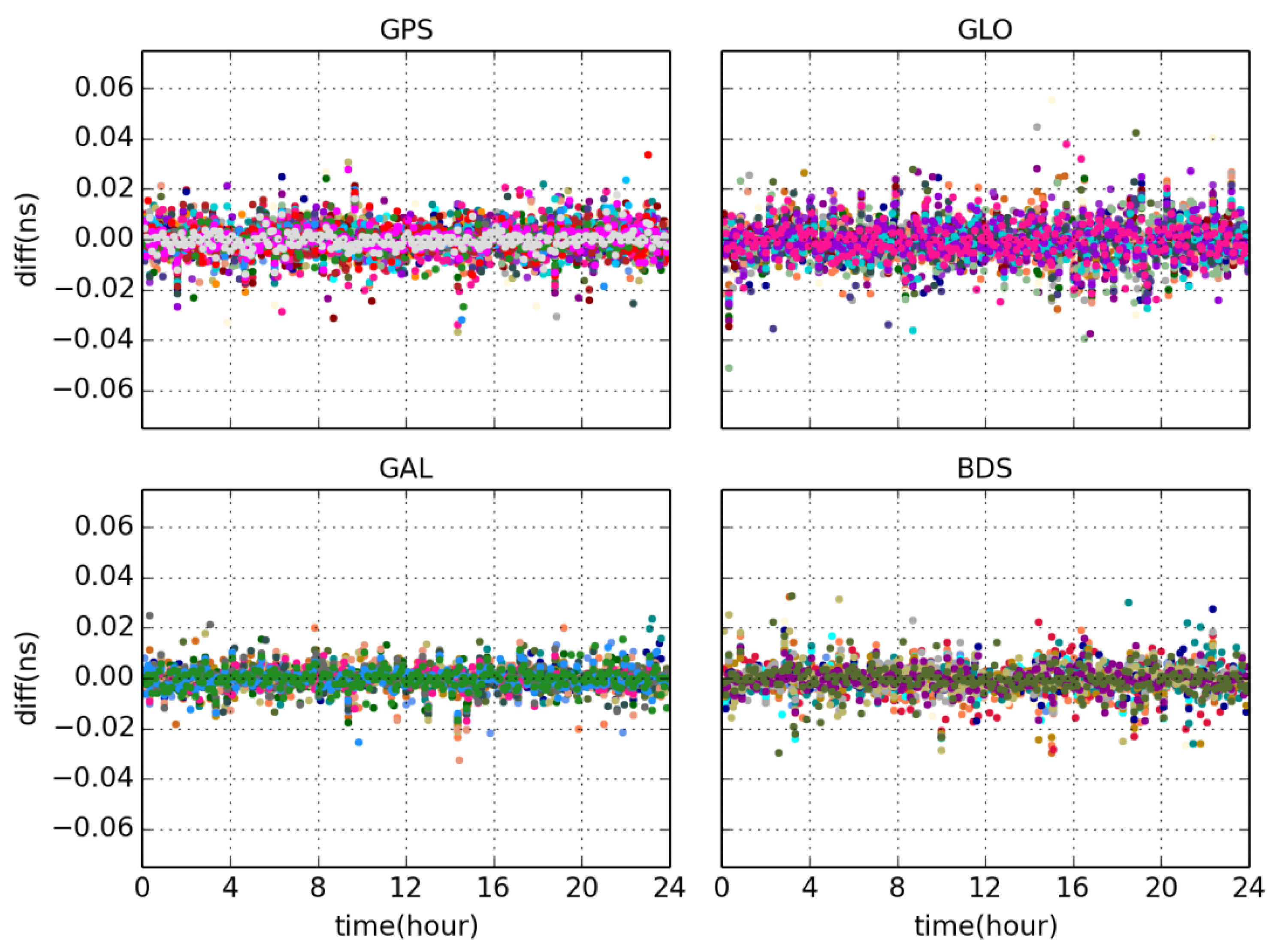

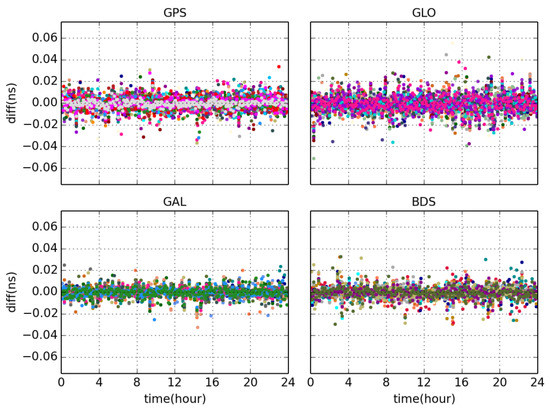

According to the combination algorithm described by (9), the difference between DECE and UD clocks is mainly caused by the non-synchronization of the clock datum. Taking the results of DOY 251 in 2018 as an example, Figure 7 shows the time series of differences between the DECE and UD products and each subplot shows the differences of all satellites of one system.

Figure 7.

Differences between decentralized clock estimation (DECE) clock and undifferenced (UD) clock on DOY 251, 2018.

From the results, it is obvious that most of the differences between DECE and UD are very subtle, normally smaller than 0.02 nsec (about 6 mm). For multi-GNSS real-time PPP, the influence of such differences can be ignored.

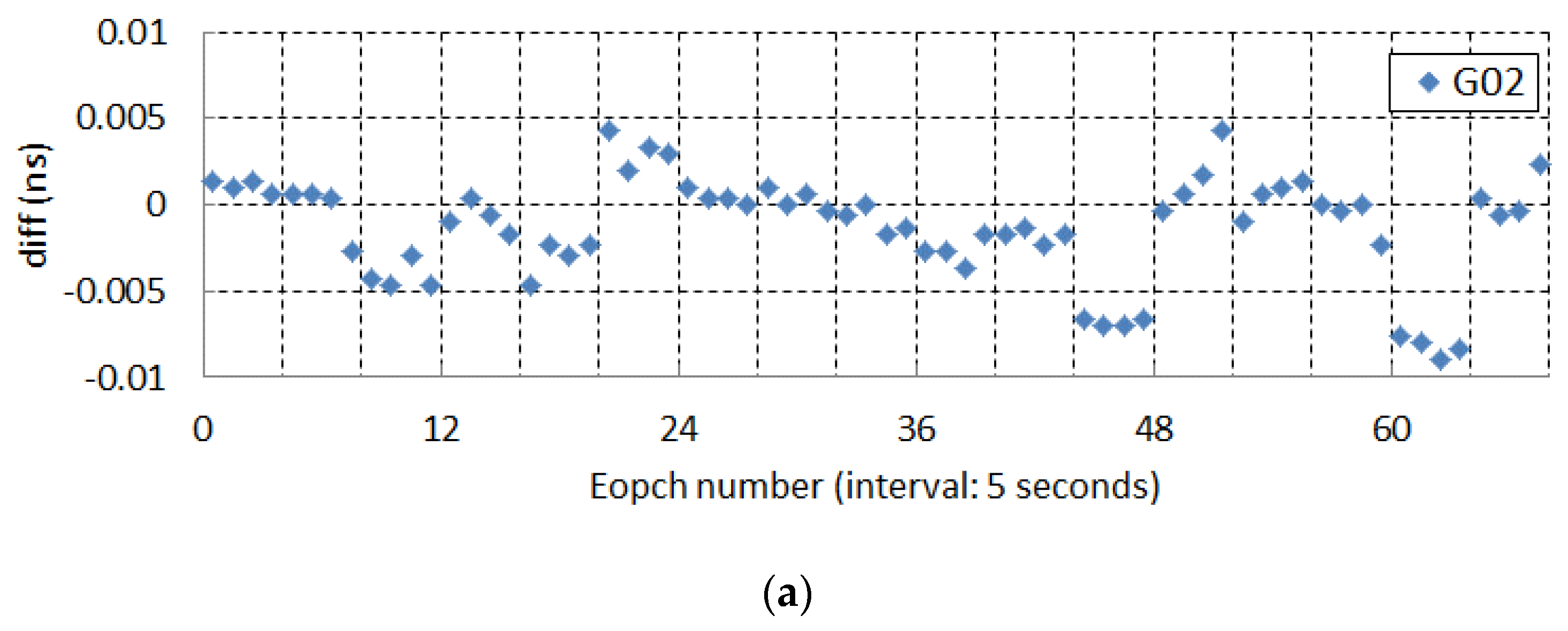

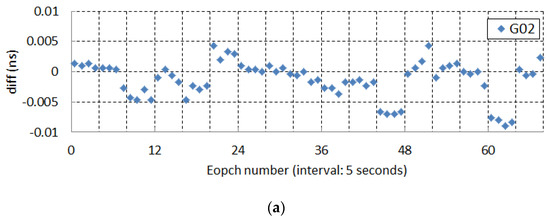

Figure 8 shows the detailed behavior of the difference between the UD and the DECE results, which takes a 5-min time series as an example. Since the interval of UD results is 20 s, which cannot fit with the 5-s DECE clock at each epoch, the linear interpolation has implemented to the UD clock to ensure there is always a corresponding point fit to DECE. In addition, it will not be clear enough if the results of many satellites are plotted together in one figure, so here we plot the single satellite’s series and take G02 and G06 as an example for analysis.

Figure 8.

(a) Detailed differences between decentralized clock estimation (DECE) and undifferenced (UD) clock (G02). (b) Detailed differences between DECE and UD clock (G06).

Figure 8 is interesting because there appears to be a periodical slip every 4 epochs (20 s) in the series, but not always obviously. This is probably because normally the DECE process needs to adjust to the UD process as a datum every 4 epochs. According to the combination methodology described in Section 2.3, the difference between DECE and UD clocks present in the series is mainly caused by the non-synchronization of the clock datum. However, more detailed property of these slips still needs further research.

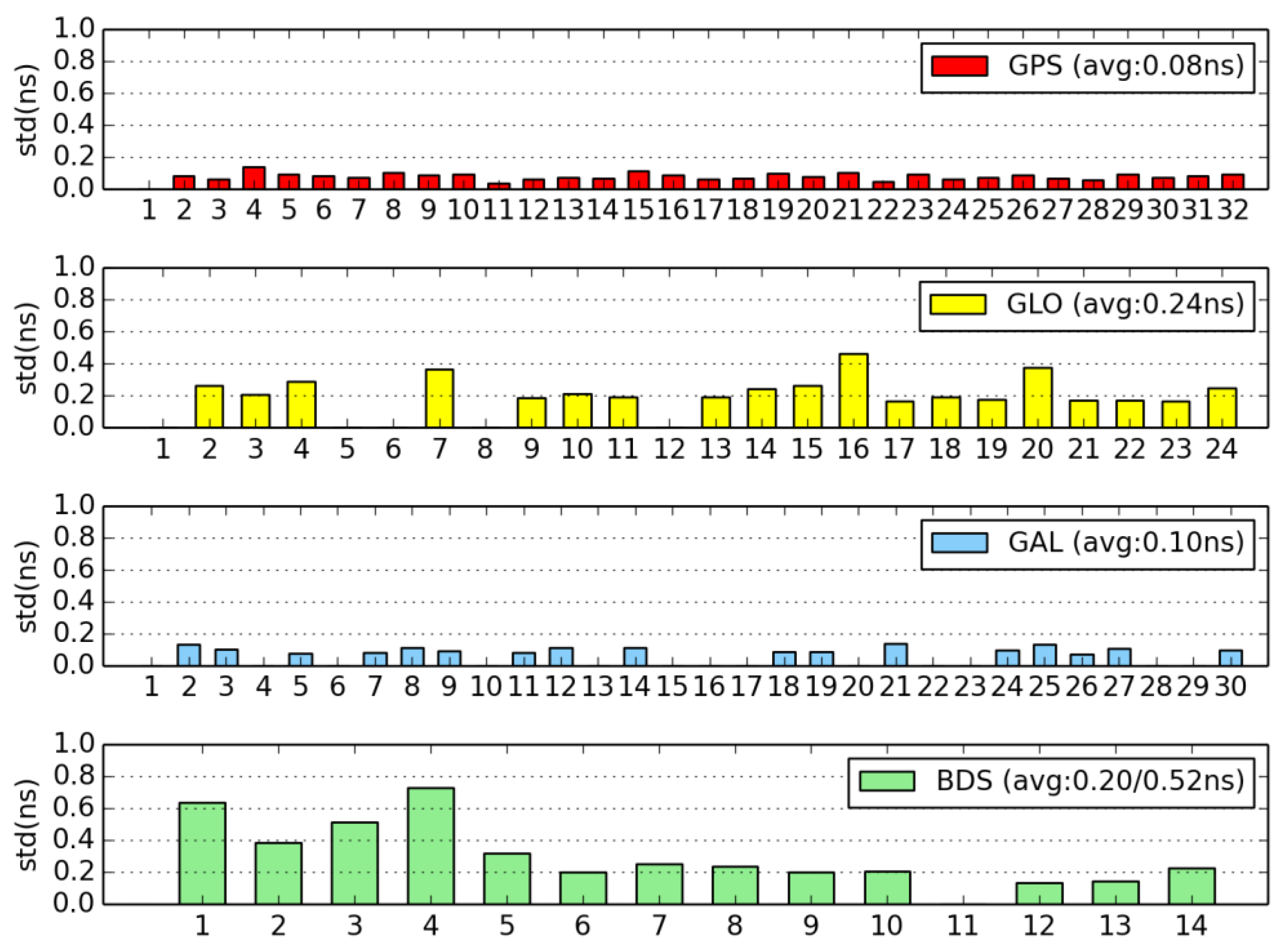

5.2. Decentralized Clock Estimation (DECE) Compared to Post-Processing Products

As for further evaluation of the DECE products, they are also compared with the MGEX final products provided by GFZ (GBM) which is supposed to have the best quality among the existing multi-GNSS products [37]. The clock difference and the Signal-In-Space Ranging Error (SISRE) which is a measure of the joint effect of orbits and clocks will be analyzed below.

5.2.1. Clock Difference

Since receiver and satellite clocks are estimated epoch-wise as white noise, the clock datum could change from epoch to epoch and the inter-system range bias at receivers could also induce inter-system clock biases. Therefore, in the multi-GNSS clock comparison, a satellite clock from each system is selected as a reference, and single-differenced clocks with respect to the reference satellites are used, in which the datum differences between different products are removed. Here G01, R01, E01, and C11 are selected as the reference satellite for each system, respectively.

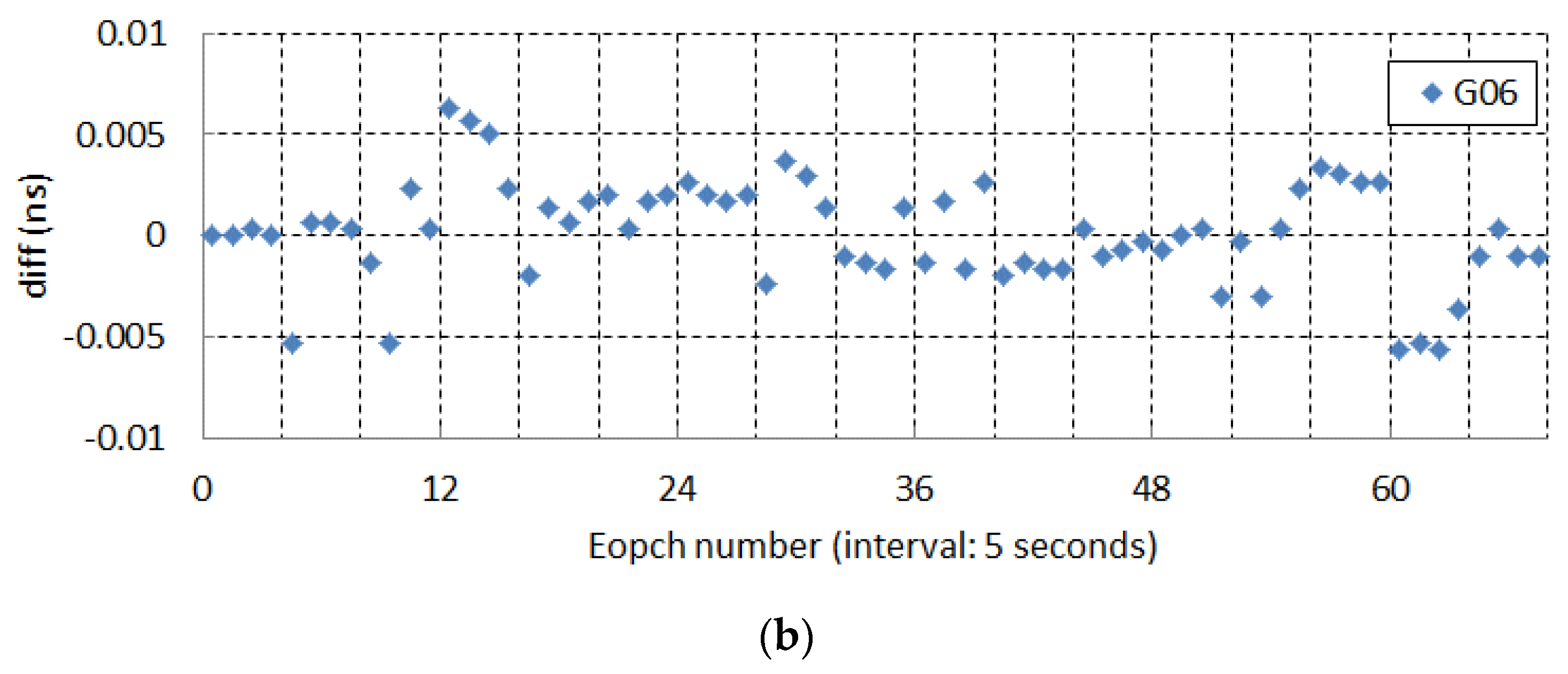

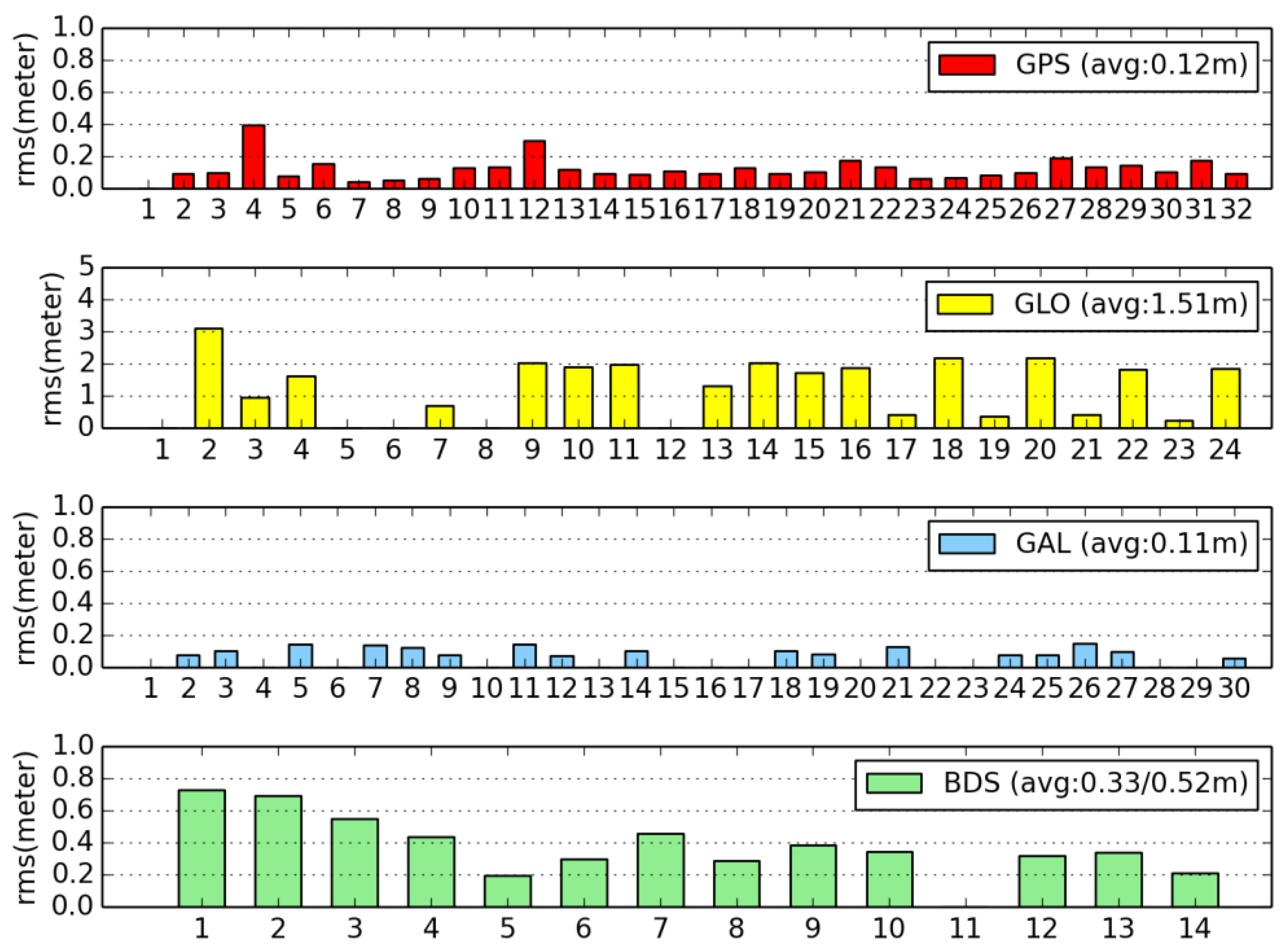

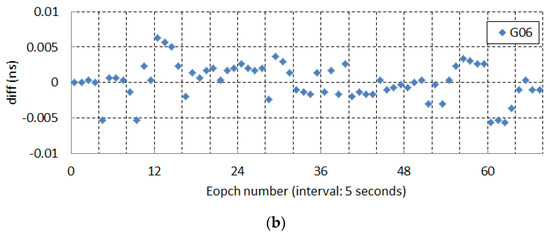

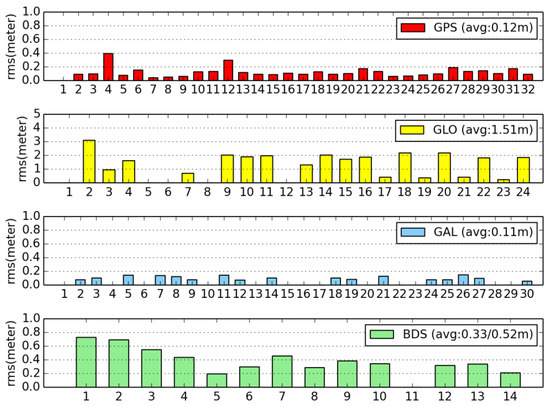

As the bias in the time series of the between-satellite clock differences can be absorbed by ambiguities in PPP, the Standard Deviation (STD) of the clock is a significant indicator to reflect the impact of the clock on phase-based positioning. STD values of the differenced clocks are calculated for each satellite and shown in Figure 9. Each subplot in Figure 9 is for a system indicated inside the th system averaged STD value. For BDS to the left and right of the slash means the value for MEO/IGSO and GEO, respectively.

Figure 9.

STD of clock difference.

From the statistical results above, it can be seen that the average STD of GPS is 0.08 nsec, while GLONASS, Galileo, BDS MEO/ISO, and BDS GEO are 0.24 nsec, 0.10 nsec, 0.20 nsec, and 0.52 nsec, respectively. The main reason for the larger difference of BDS GEO satellites is due to the insufficient tracking stations and the poor tracking geometry.

5.2.2. Signal-in-Space Ranging Error (SISRE)

In the clock estimation, most of the orbit biases in the radial direction can be absorbed by clock parameters. This means that satellite clocks are biased by orbit biases in the radial direction and the biases are complementary. The SISRE is a statistical measure for the impact of orbit and clock errors on the modeled pseudorange. The SISRE takes the orbit differences into consideration while comparing clocks of two products by projecting their satellite position difference on the line-of-sight direction from satellite to the user position. It is introduced as a more reliable indicator of the comprehensive influence of orbits and clocks. The formula of SISRE is given by Montenbruck et al. [38] as

where , , and represent the orbit differences in radial direction, along direction, and cross directions, while denotes the real-time clock error compared to final products, is the speed of light in vacuum, and represent the SISRE coefficient according to satellite altitude. The coefficients for multi-GNSS SISRE are shown in Table 4 [38]. Obviously, we can find that the SISRE is mostly affected by the radial direction orbit difference and clock difference.

Table 4.

Coefficient of Signal-in-Space Ranging Error (SISRE).

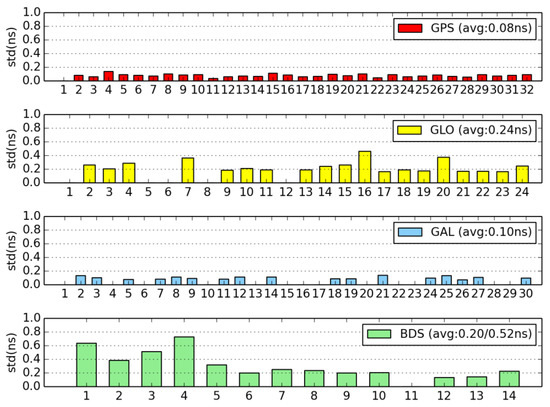

The results of SISRE are shown in Figure 10. From the statistical results above, it can be seen that the Root Mean Square (RMS) of SISRE for GPS is 0.12 m, while GLONASS, Galileo, BDS MEO/ISO, and GEO 1.51 m, 0.11 m, 0.33 m, and 0.52 m, respectively. The SISRE of GLONASS is significantly larger than for other systems probably due to frequency division multiple access (FMDA) which needs further research. It should be noted that the SISRE mainly reflects the influence of the products on pseudorange positioning.

Figure 10.

Signal-in-space ranging error (SISRE) of decentralized clock estimation (DECE) real-time clock.

5.3. Precise Point Positioning (PPP) Validation

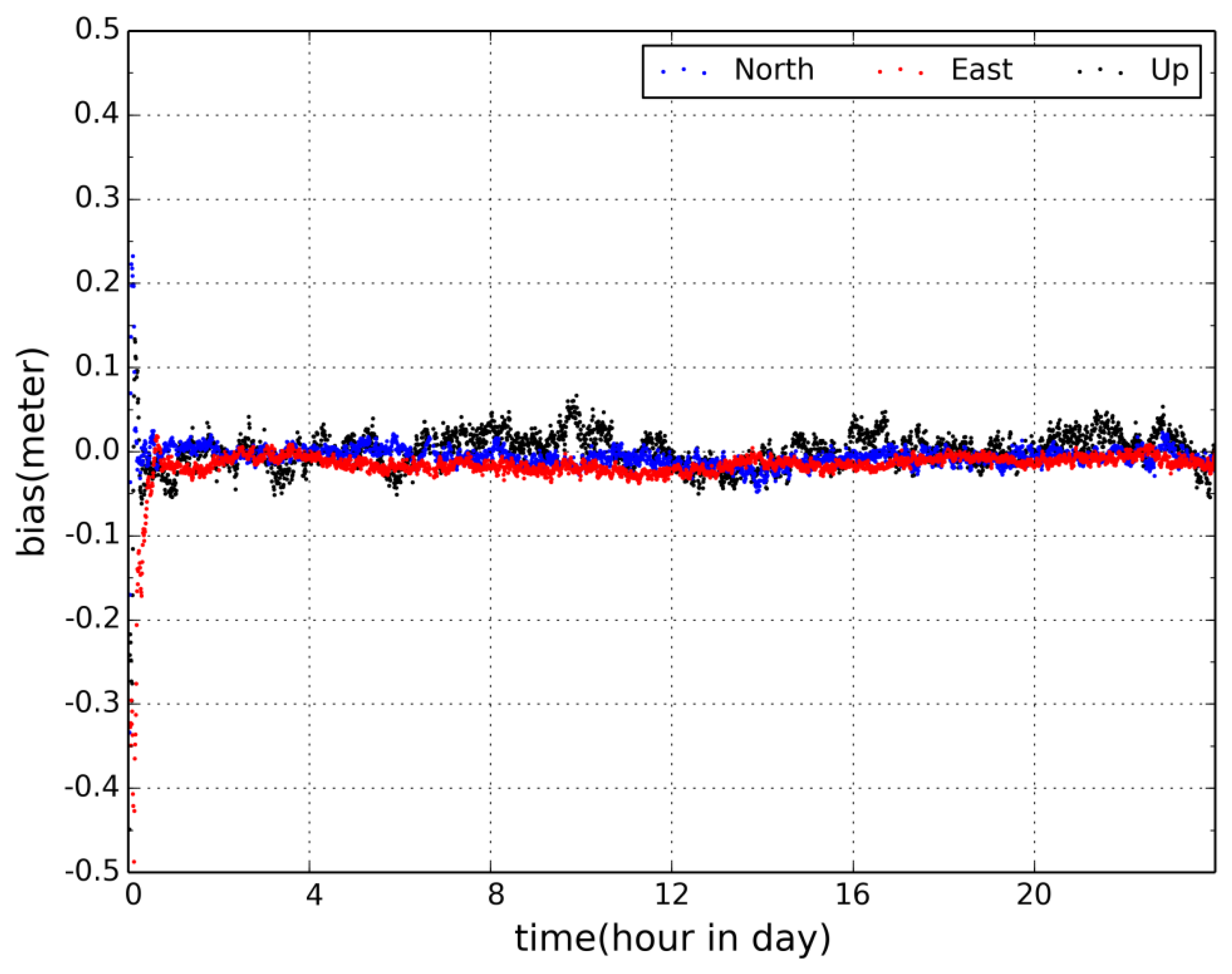

PPP is a convincing way to directly verify the orbit and clock products together. In the experiment, real-time kinematic PPP is also carried out for 12 global multi-GNSS stations from MGEX using the DECE products and the UD products, respectively. The data processing strategy and parameter model are the same as in Table 3, except that the satellite clock is fixed in PPP and coordinates are estimated in the kinematic mode as white noise. The real-time streams come from mgex.igs-ip.net:2101 and the sample rate is set to five seconds. PPP for all stations is processed using multi-GNSS observations.

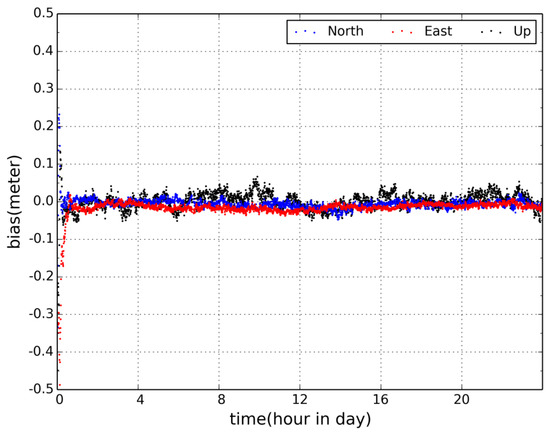

Figure 11 illustrates the positioning error of the station ASCG in the north, east, and vertical components. The figure shows that the positioning accuracy of PPP with the DECE clock in a real-time mode is better than 10 cm in the horizontal and 20 cm in the vertical after initialization, which can meet the need most positioning applications. Similar accuracies were obtained for the other stations.

Figure 11.

Result of real-time precise point positioning (PPP) using decentralized clock estimation (DECE) clock (ASCG).

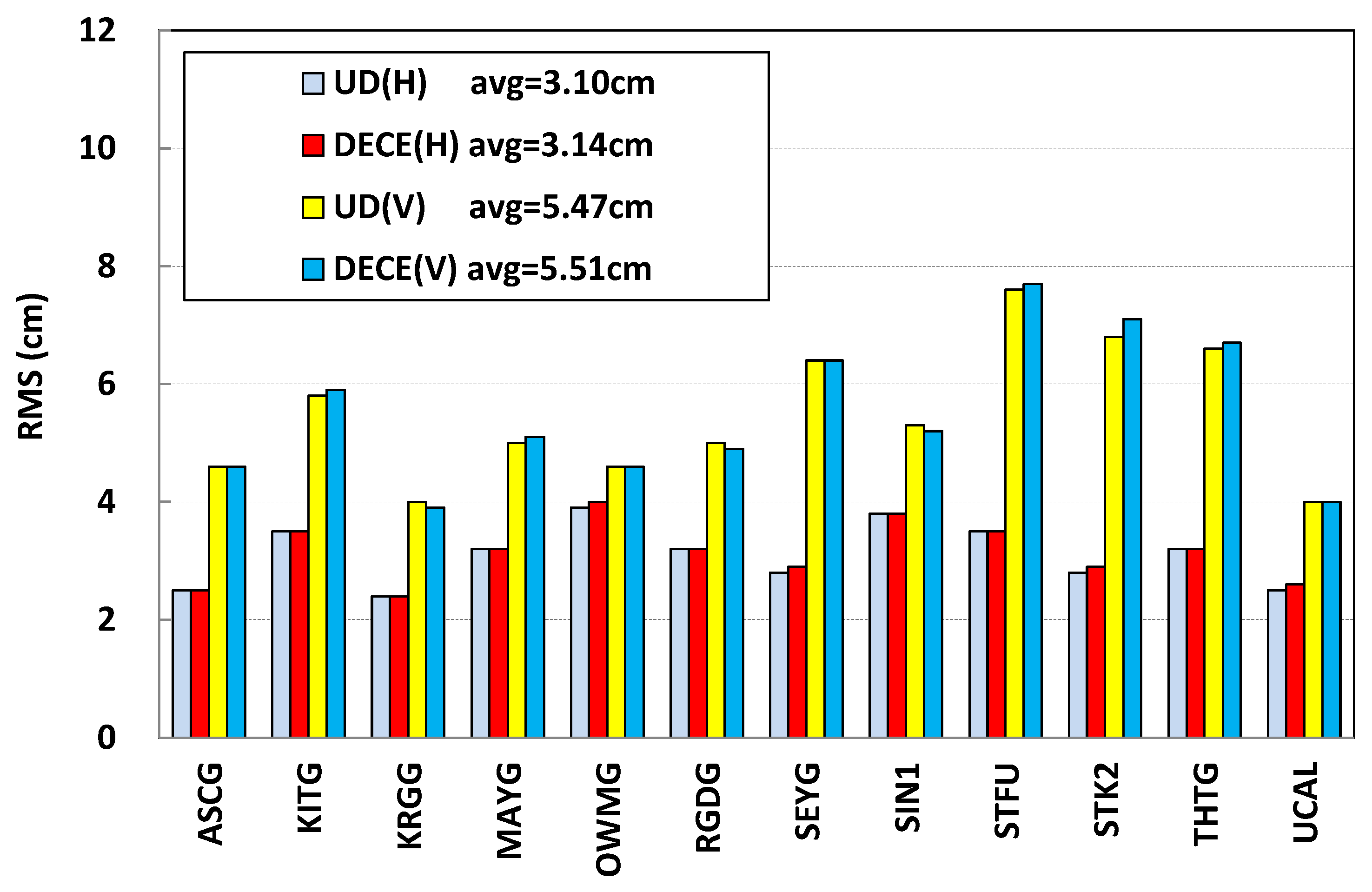

The RMS is an important indicator for evaluating the positioning performance which can be calculated as

where and represent any of the calculated and reference coordinates and is the epoch number used for PPP.

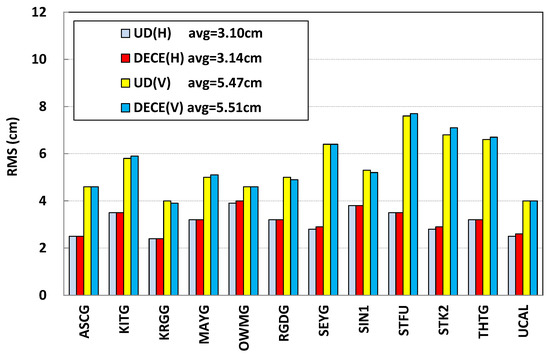

In the experiment, the RMS of the position differences using DECE and UD products are shown in Figure 12, in which the legend H and V mean horizontal and vertical direction, respectively. All results are counted after PPP convergence. The statistics show that the average RMS is about 3.10 cm for using UD and 3.14 cm for DECE in horizontal, and 5.47 cm for using UD and 5.51 cm for DECE in vertical. In general, for PPP, centimeter-level positioning results can be achieved using the clock products. Normally the result of UD is a little better than DECE, but there is almost no difference in the accuracy between using DECE and UD products.

Figure 12.

RMS of real-time precise point positioning (PPP) position differenced with respect to their ground truth using decentralized clock estimation (DECE) and undifferenced (UD) products.

6. Discussion

With the great progress of multi-GNSS real-time PPP, the performance of real-time clock products becomes more and more important. Different from post-processing and near-RT modes, the computational efficiency of real-time clock estimation is critical, because the delay or missing of the products will directly affects the positioning accuracy of the PPP client. Moreover, since the recovery of real-time service normally takes a lot of time, especially in case of software crashes, higher requirements for the stability and continuously of real-time products are also necessary. In Section 3, to solve the problems above, we proposed a DECE strategy to improve the computational efficiency and enhance the robustness of the real-time system. First, both low-rate UD and high-rate ED processes are implemented to guarantee the timely update of real-time clock products. From Figure 1 and Figure 7, it is noted that although with the launch of more new satellites and setup of more ground GNSS stations in near future, the processing pressure will still not increase significantly. In addition, when using the DECE strategy, more than one line can be the processed in different processing centers or processing using different strategies (ED/UD). This means the robustness of the processing or the availability of the clock products can be significantly improved by such a distributed system, as the system can always provide high-rate clock products if one of the redundant ED solutions and one of the redundant UD solutions are both working well. As the PPP experimental results show in Section 5.3, centimeter accuracy position can be achieved using the DECE real-time products, which is a great improvement of computational efficiency and robustness. It also improves the experience of real-time positioning users.

7. Conclusions

We proposed the decentralized clock estimation approach to improve the computational efficiency and robustness of the real-time precise positioning service. In the new approach, both the UD and ED modes are implemented but run separately in different computers. The UD mode estimates clock offsets with a lower update rate because a great number of ambiguities parameters are included, while the ED mode determines clock variations with a higher update rate. The products of the two modes are combined to generate the final products. Redundant UD and/or ED processing lines can be scheduled even in offsite computers with an internet connection to improve the robustness of the processing system. More processing lines for different networks can also be included to improve the clock quality.

The new approach is realized for the experimental evaluation based on the PANDA software package for GNSS data processing and BNC software for data communication. The experiment was carried out in real time with about 110 stations for clock estimation and 12 stations for PPP. The clock comparison of the new approach with GFZ MGEX product shows that the STD of GPS is 0.08 nsec, while GLONASS, Galileo, BDS MEO/ISO, and BDS GEO are 0.24 nsec, 0.10 nsec, 0.20 nsec, and 1.52 nsec, respectively. The STD of signal-in-space range error (SISRE) of the clock product of GPS is 0.02 m, while GLONASS, Galileo, BDS MEO/ISO, and BDS GEO are 1.51 m, 0.11 m, 0.33 m, and 0.52 m, respectively. Using the estimated clocks and corresponding orbit products, real-time kinematic multi-GNSS precise point positioning can be realized with an averaged RMS of about 3.14 cm in horizontal and 5.51 cm in vertical.

All these results confirm that the decentralized clock estimation can provide comparable clock products as the most used undifferenced method but with a much higher computational efficiency and robustness. It is a suitable approach for multi-GNSS real-time clock estimation with the increasing number of satellites and stations and signals of different frequency bands.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the work. X.J. conceived and designed the experiments; X.J. and S.G. performed the experiments; X.J. and P.L. analyzed the data; X.J. and P.L. wrote the paper; S.G., P.L., M.G. and H.S. helped modify the paper.

Funding

This study is sponsored by the National Key Research and Development Plan (No. 2016YFB0501802).

Acknowledgments

We thank the IGS for providing the real-time data streams and the BKG for providing the open source software BNC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Malys, S.; Jensen, P.A. Geodetic point positioning with GPS carrier beat phase data from the CASA UNO experiment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1990, 17, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumberge, J.F.; Heflin, M.B.; Jefferson, D.C.; Watkins, M.M.; Webb, F.H. Precise point positioning for the efficient and robust analysis of GPS data from large networks. J. Geophys. Res. 1997, 102, 5005–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisnath, S.; Gao, Y. Current state of precise point positioning and future prospects and limitations. In Observing our Changing Earth. International Association of Geodesy Symposia; Sideris, M.G., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Shi, C.; Ge, M.; Dodson, A.; Lou, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, J. Improving the estimation of fractional-cycle biases for ambiguity resolution in precise point positioning. J. Geodesy 2012, 86, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Gendt, G.; Rothacher, M.; Shi, C.; Liu, J. Resolution of GPS carrier-phase ambiguities in precise point positioning (PPP) with daily observations. J. Geodesy 2008, 82, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ge, M.; Dai, X.; Ren, X.; Fritsche, M.; Wickert, J.; Schuh, H. Accuracy and reliability of multi-GNSS real-time precise positioning: GPS, GLONASS, BeiDou, and Galileo. J. Geodesy 2015, 89, 607–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Zheng, F.; Gu, S.; Wang, C.; Guo, H.; Feng, Y. Multi-GNSS precise point positioning with raw single-frequency and dual-frequency measurement models. GPS Solut. 2016, 20, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lou, Y.; Ye, S.; Zhang, R.; Song, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Assessment of PPP integer ambiguity resolution using GPS, GLONASS and BeiDou (IGSO, MEO) constellations. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 1647–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ge, M.; Dousa, J.; Wickert, J. Real-time precise point positioning regional augmentation for large GPS reference networks. GPS Solut. 2014, 18, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, N.; Tan, B.; Chen, Y. Multi-GNSS precise point positioning (MGPPP) using raw observations. J. Geodesy 2017, 91, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTCM. Radio Technical Commission for Maritime Services (RTCM) Standard 10403.3, Differential GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite Systems) Services; Radio Technical Commission for Maritime Services: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kouba, J.; Héroux, P. Precise point positioning using IGS orbit and clock products. GPS Solut. 2001, 5, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, J.; Ray, J. On the precision and accuracy of IGS orbits. J. Geodesy 2009, 83, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Guo, S.; Gu, S.; Yang, X.; Gong, X.; Deng, Z.; Ge, M.; Schuh, H. Multi-GNSS satellite clock estimation constrained with oscillator noise model in the existence of data discontinuity. J. Geodesy 2019, 93, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, H.; Dach, R.; Jäggi, A.; Beutler, G. High-rate GPS clock corrections from CODE: Support of 1 Hz applications. J. Geodesy 2009, 83, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Guo, F. Satellite clock estimation at 1 Hz for realtime kinematic PPP applications. GPS Solut. 2011, 15, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Chen, J.; Douša, J.; Gendt, G.; Wickert, J. A computationally efficient approach for estimating high-rate satellite clock corrections in realtime. GPS Solut. 2012, 16, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, Q.; Hu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Geng, C.; Ge, M.; Shi, C. GNSS global real-time augmentation positioning: Real-time precise satellite clock estimation, prototype system construction and performance analysis. Adv. Space Res. 2017, 61, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Song, W.; Yi, W.; Shi, C.; Lou, Y.; Guo, H. Research on a method of real-time combination of precise GPS clock corrections. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lou, Y.; Gu, S.; Shi, C.; Haase, J.S.; Liu, J. Joint estimation of GPS/BDS real-time clocks and initial results. GPS Solut. 2016, 20, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Gu, S.; Lou, Y.; Zheng, F.; Ge, M.; Liu, J. An efficient solution of real-time data processing for multi-GNSS network. J. Geodesy 2017, 92, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurichesse, D.; Mercier, F.; Berthias, J.P. Real time GPS constellation and clocks estimation using zero-difference integer ambiguity fixing. In Proceedings of the ION ITM 2009, Anaheim, CA, USA, 26–28 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Laurichesse, D.; Cerri, L.; Berthias, J.P.; Mercier, F. Real time precise GPS constellation and clocks estimation by means of a Kalman filter. In Proceedings of the ION GNSS 2013, Nashville, TN, USA, 16–20 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mervart, L.; Weber, G. Real-time combination of GNSS orbit and clock correction streams using a Kalman Filter approach. In Proceedings of the ION GNSS 2011, Portland, OR, USA, 20–23 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Ge, M. PANDA Software and its preliminary result of positioning and orbit determination. Wuhan Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2003, 8, 603–609. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Zhao, Q.; Geng, J.; Lou, Y.; Ge, M.; Liu, J. Recent development of PANDA software in GNSS data processing. In Proceedings of the SPIE Volume 7285, Wuhan, China, 8–30 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dach, R.; Schaer, S.; Hugentobler, U. Combined multi-system GNSS analysis for time and frequency transfer. In Proceedings of the 20th European Frequency and Time Forum EFTF06, Braunschweig, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, G.J. The treatment of bias in the square-root information filter/smoother. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1975, 16, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Lou, Y.; Dai, Z.; Qing, Y.; Li, M.; Shi, C. Real-time precise orbit determination for BDS satellites using the square root information filter. GPS Solut. 2019, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J.; Dong, D.; Altamimi, Z. IGS reference frames: Status and future improvements. GPS Solut. 2004, 5, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebischung, P.; Altamimi, Z.; Ray, J.; Garayt, B. The IGS contribution to ITRF2014. J. Geodesy 2016, 90, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürze, A.; Mervart, L.; Weber, G.; Rülke, A.; Wiesensarter, E.; Neumaier, P. The new version 2.12 of BKG Ntrip Client (BNC). Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2016, 18, 12012. [Google Scholar]

- Gendt, G.; Dick, G.; Reigber, C.H.; Tomassini, M.; Liu, Y.; Ramatschi, M. Demonstration of NRT GPS water vapor monitoring for numerical weather prediction in Germany. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 2003, 82, 360–370. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Wu, S.; Hajj, G.; Bertiger, W.; Lichten, S. Effects of antenna orientation on GPS carrier phase. Manuscr. Geodesy 1993, 18, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, J.; Niell, A.; Tregoning, P.; Schuh, H. Global mapping function (GMF): A new empirical mapping function based on numerical weather model data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L07304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, G.; Luzum, B. IERS Conventions 2010; Iers Technical Note 36; Verlag des Bundesamts für Kartographie und Geodäsie: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2010; Volume 36, pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Fritsche, M.; Uhlemann, M.; Wickert, J.; Schuh, H. Reprocessing of GFZ Multi-GNSS Product GBM. In Proceedings of the IGS Workshop, Sydney, Australia, 8–12 February 2016; Available online: http://acc.igs.org/workshop2016/presentations/Plenary_01_06.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2016).

- Montenbruck, O.; Steigenberger, P.; Hauschild, A. Broadcast versus precise ephemerides: A multi-GNSS perspective. GPS Solut. 2015, 19, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).