The Impact of Herbs and Spices on Increasing the Appreciation and Intake of Low-Salt Legume-Based Meals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

- Phase I: recipe development and determination of the most liked herb and spice modification for use in further study and confirmation of differences in perception of saltiness and spiciness.

- Phase II: evaluation of the overall liking of the different versions of the selected recipe in different meal sessions (one week apart), as a measure of absolute liking.

- Phase III: follow-up assessment study, where all four versions of the legume-based dish were evaluated during the same session, as a measure of relative liking.

2.1. Phase I

Recipe Development

- Curcumin blend modification: curcumin (0.8 g), ginger (0.4 g), shallot (0.4 g), and garlic (0.4 g);

- Ginger modification: ginger (1 g);

- Paprika blend modification: paprika (0.6 g), tomato (0.6 g), coriander (0.4 g), and garlic (0.4 g);

- Cumin blend modification: cumin (0.4 g), shallots (0.6 g), garlic (0.4 g), and spinach coulis (10 g).

- The standard-salt legume-based mezze (S);

- The low-salt legume-based mezze without herbs and spices (LS);

- The standard-salt legume-based mezze with herbs and spices (SHS);

- The low-salt legume-based mezze with herbs and spices (LSHS).

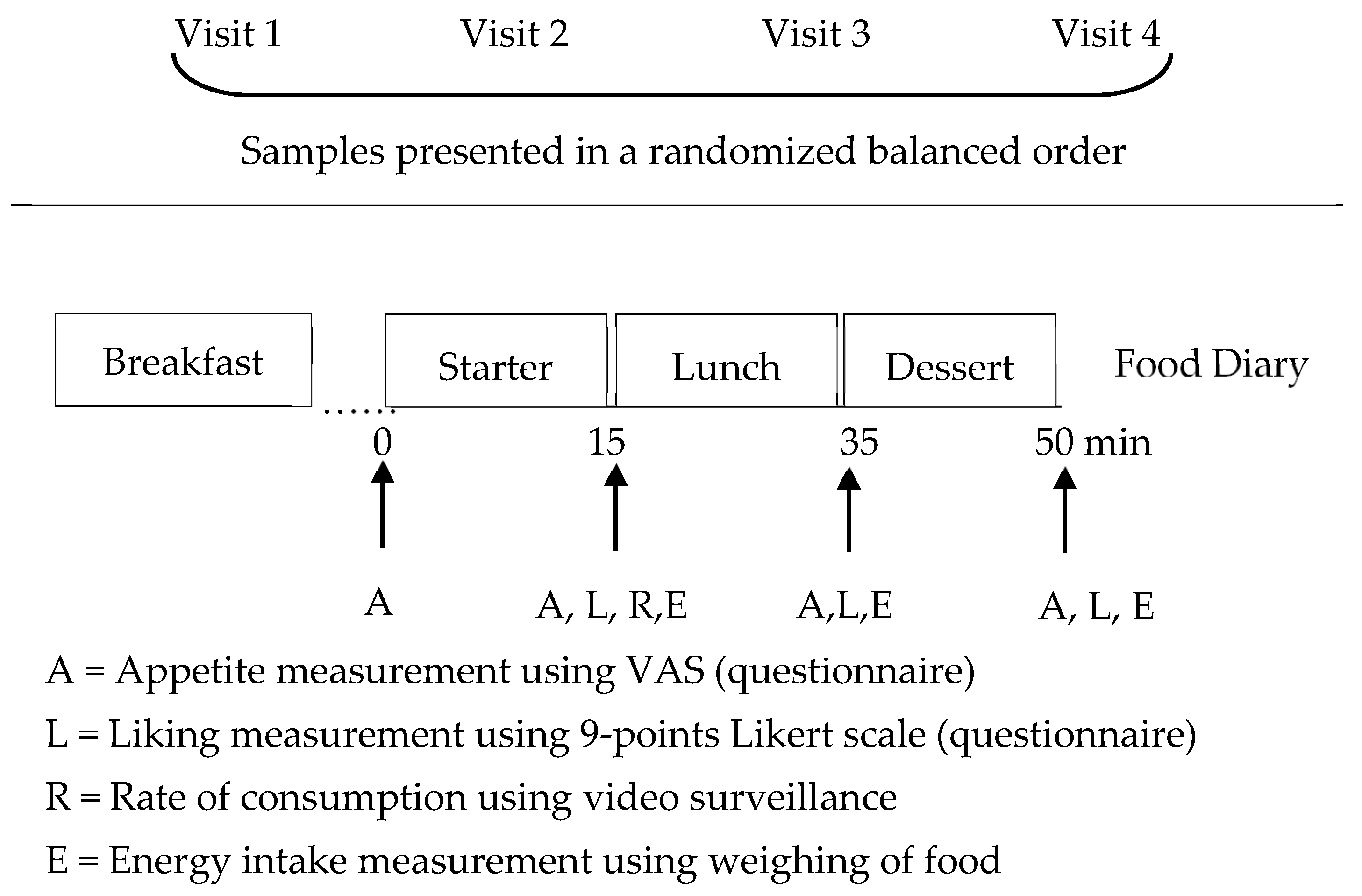

2.2. Phase II—Study Intervention

2.2.1. Subjects

2.2.2. Study Design and Test Meals

2.2.3. Measurements

Hedonic Evaluation of the Mezzes and Study Food Items

Appetite Measures Using Visual Analogue Scales

Food and Energy Intake

Assessment of Eating Rate

Habitual Salt Intake

2.3. Phase III—Follow-up Assessment Study

Appreciation of the Different Versions of the Selected Herb and Spice Modification Presented at the Same Session

3. Statistical Analysis

3.1. Power Analysis

3.2. Phase I and III

3.3. Phase II

4. Results

4.1. Phase I

4.1.1. Appreciation of the Legume-Based Mezzes with Different Herb and Spice Modifications

4.1.2. Directional Paired Comparisons of Perceived Salt and Spice Intensity

4.2. Phase II

4.2.1. Subject Characteristics

4.2.2. Appreciation of the Legume-Based Mezzes at Varied Salt and Herb and Spice Levels

4.2.3. Appetite Profile

4.2.4. Ad Libitum Legume-Based Mezze, Salt, and Total Energy Intake

4.2.5. Eating Behavior

4.3. Phase III

Appreciation of the Legume-Based Mezzes at Varied Salt and Herb and Spice Levels Presented at the Same Session

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, M.E.; Hamm, M.W.; Hu, F.B.; Abrams, S.A.; Griffin, T.S. Alignment of Healthy Dietary Patterns and Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. An Int. Rev. J. 2016, 7, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Goffe, L.; Brown, T.; Lake, A.A.; Summerbell, C.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Adamson, A.J. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1-4 (2008-12). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saksena, M.J.; Okrent, A.M.; Anekwe, T.D.; Cho, C.; Dicken, C.; Effland, A.; Elitzak, H.; Guthrie, J.; Hamrick, K.S.; Hyman, J.; et al. America’s Eating Habits: Food Away From Home; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Llanaj, E.; Adany, R.; Lachat, C.; D’Haese, M. Examining food intake and eating out of home patterns among university students. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appel, L.J.; Foti, K. Sources of dietary sodium. Circulation 2017, 135, 1784–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.M.; Appel, L.J.; Okuda, N.; Brown, I.J.; Chan, Q.; Zhao, L.; Ueshima, H.; Kesteloot, H.; Miura, K.; Curb, J.D.; et al. Dietary Sources of Sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Women and Men Aged 40 to 59 Years: The INTERMAP Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, P.A.S.; Beauchamp, G.K. Salt enhances flavour by suppressing bitterness [5]. Nature 1997, 387, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I.J.; Tzoulaki, I.; Candeias, V.; Elliott, P. Salt intakes around the world: Implications for public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.R.; Cutler, J.A.; Obarzanek, E.; Buring, J.E.; Rexrode, K.M.; Kumanyika, S.K.; Appel, L.J.; Whelton, P.K. Long term effects of dietary sodium reduction on cardiovascular disease outcomes: Observational follow-up of the trials of hypertension prevention (TOHP). Br. Med. J. 2007, 334, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, K.; McLean, R.; Johnson, C.; Santos, J.A.; Raj, T.S.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Webster, J. The Science of Salt: A Regularly Updated Systematic Review of the Implementation of Salt Reduction Interventions (November 2015 to February 2016). J. Clin. Hypertens. 2016, 18, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Draft comprehensive global monitoring framework and targets for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. In Proceedings of the Sixty-sixth World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, 20–28 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marinangeli, C.P.F.; Curran, J.; Barr, S.I.; Slavin, J.; Puri, S.; Swaminathan, S.; Tapsell, L.; Patterson, C.A. Enhancing nutrition with pulses: Defining a recommended serving size for adults. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Aukema, H.M. Nutritional and health benefits of pulses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchenak, M.; Lamri-Senhadji, M. Nutritional quality of legumes, and their role in cardiometabolic risk prevention: A review. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, J. The nutritional value and health benefits of pulses in relation to obesity, diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108 (Suppl. S1), S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havemeier, S.; Erickson, J.; Slavin, J. Dietary guidance for pulses: The challenge and opportunity to be part of both the vegetable and protein food groups. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1392, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.C.; Lawrence, F.R.; Hartman, T.J.; Curran, J.M. Consumption of Dry Beans, Peas, and Lentils Could Improve Diet Quality in the US Population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LiveWell for Life. Healthy People Healthy Planet. Available online: http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/livewell___healthy_people_healthy_planet.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Adams, J.F.; Engstrom, A. Helping Consumers Achieve Recommended Intakes of Whole Grain Foods. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000, 19, 339S–344S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, H.; Smith, C. Food choice, eating behavior, and food liking differs between lean/normal and overweight/obese, low-income women. Appetite 2013, 65, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C. Flavor and Feeding: Executive Summary. In Physiology and Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 469–470. [Google Scholar]

- Ghawi, S.K.; Rowland, I.; Methven, L. Enhancing consumer liking of low salt tomato soup over repeated exposure by herb and spice seasonings. Appetite 2014, 81, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhlal, S.; Chabanet, C.; Issanchou, S.; Nicklaus, S. Salt Content Impacts Food Preferences and Intake among Children. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.C.; Polsky, S.; Stark, R.; Zhaoxing, P.; Hill, J.O. The influence of herbs and spices on overall liking of reduced fat food. Appetite 2014, 79, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, S.; Beck, J.; Stark, R.A.; Pan, Z.; Hill, J.O.; Peters, J.C. The influence of herbs, spices, and regular sausage and chicken consumption on liking of reduced fat breakfast and lunch items. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, S2117–S2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritts, J.R.; Bermudez, M.A.; Hargrove, R.L.; Alla, L.; Fort, C.; Liang, Q.; Cravener, T.L.; Rolls, B.J.; D’Adamo, C.R.; Hayes, J.E.; et al. Using Herbs and Spices to Increase Vegetable Intake Among Rural Adolescents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 806–816.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaus, C.J.; Ellison, B.; Heinrichs, P.A.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M.; Chapman-Novakofski, K.M. Spice and herb use with vegetables: Liking, frequency, and self-efficacy among US adults. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 41, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manero, J.; Phillips, C.; Ellison, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M.; Chapman-Novakofski, K.M. Influence of seasoning on vegetable selection, liking and intent to purchase. Appetite 2017, 116, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, E.M.; Stein, W.M.; Reigh, N.A.; Gater, F.M.; Bakke, A.J.; Hayes, J.E.; Keller, K.L. Increasing flavor variety with herbs and spices improves relative vegetable intake in children who are propylthiouracil (PROP) tasters relative to nontasters. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 188, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludy, M.J.; Tucker, R.M.; Tan, S.Y. Chemosensory Properties of Pungent Spices: Their Role in Altering Nutrient Intake. Chemosens. Percept. 2015, 8, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanzer, Y.C.; Plaza, M.; Dougkas, A.; Turner, C.; Björck, I.; Östman, E. Polyphenol-rich spice-based beverages modulated postprandial early glycaemia, appetite and PYY after breakfast challenge in healthy subjects: A randomized, single blind, crossover study. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 35, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, E.I. Culinary herbs and spices: What can human studies tell us about their role in the prevention of chronic non-communicable diseases? J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4511–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.V.; Byrne, D.V.; Bredie, W.L.P.; Møller, P. Cayenne pepper in a meal: Effect of oral heat on feelings of appetite, sensory specific desires and well-being. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.D.; Bendsen, N.T.; Christensen, S.M.; Astrup, A.; Raben, A. Meals based on vegetable protein sources (beans and peas) are more satiating than meals based on animal protein sources (veal and pork)—A randomized cross-over meal test study. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standards Agency. Food and You—Wave Four. Available online: https://www.food.gov.uk/research/food-and-you/food-and-you-wave-four (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Robinson, E.; Jones, A.; Whitelock, V.; Mead, B.R.; Haynes, A. (Over)eating out at major UK restaurant chains: Observational study of energy content of main meals. BMJ 2018, 363, k4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polak, R.; Phillips, E.M.; Campbell, A. Legumes: Health benefits and culinary approaches to increase intake. Clin. Diabetes 2015, 33, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Margier, M.; Georgé, S.; Hafnaoui, N.; Remond, D.; Nowicki, M.; Du Chaffaut, L.; Amiot, M.J.; Reboul, E. Nutritional composition and bioactive content of legumes: Characterization of pulses frequently consumed in France and effect of the cooking method. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giboreau, A. Sensory and consumer research in culinary approaches to food. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 15, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkard, A.J.; Messick, S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J. Psychosom. Res. 1985, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A.; Raben, A.; Blundell, J.E.; Astrup, A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samra, R.A.; Anderson, G.H. Insoluble cereal fiber reduces appetite and short-term food intake and glycemic. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allirot, X.; Saulais, L.; Disse, E.; Anne, J.; Cazal, C.; Laville, M. Integrating behavioral measurements in physiological approaches of satiety. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allirot, X.; Saulais, L.; Disse, E.; Roth, H.; Cazal, C.; Laville, M. Validation of a buffet meal design in an experimental restaurant. Appetite 2012, 58, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, K.E.; Steyn, K.; Levitt, N.S.; Jonathan, D.; Zulu, J.V.; Nel, J.H. Development and validation of a short questionnaire to assess sodium intake. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, J.E.; Sullivan, B.S.; Duffy, V.B. Explaining variability in sodium intake through oral sensory phenotype, salt sensation and liking. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 100, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fritts, J.R.; Fort, C.; Quinn Corr, A.; Liang, Q.; Alla, L.; Cravener, T.; Hayes, J.E.; Rolls, B.J.; D’Adamo, C.; Keller, K.L. Herbs and spices increase liking and preference for vegetables among rural high school students. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 030908525X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadiveloo, M.K.; Campos, H.; Mattei, J. Seasoning ingredient variety, but not quality, is associated with greater intake of beans and rice among urban Costa Rican adults. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phillips, T.; Zello, G.A.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Vandenberg, A. Perceived benefits and barriers surrounding lentil consumption in families with young children. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, M.C.; Ellmore, G.S.; McKeown, N. Seeds-health benefits, barriers to incorporation, and strategies for practitioners in supporting consumption among consumers. Nutr. Today 2016, 51, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calles, T.; del Castello, R.; Baratelli, M.; Xipsiti, M.; Navarro, D.K. International Year of Pulses–Final Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; p. 40, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos Reid. Factors Influencing Pulse Consumption in Canada: Segment Toolkit: Health Driven Persuadables; Ipsos Reid: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.; Cobb, L.K.; Miller, E.R.; Woodward, M.; Chang, A.; Mongraw-Chaffin, M.; Appel, L.J. Effects of a behavioral intervention that emphasizes spices and herbs on adherence to recommended sodium intake. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 129, 671–679. [Google Scholar]

- Bellisle, F.; Giachetti, I.; Tournier, A. Determining the preferred level of saltiness in a food product. A comparison between sensory evaluations and actual consumption tests. Sci. Aliment. 1988, 8, 557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.O.; Maller, O.; Cardello, A.V. Consumer Acceptance of Foods Lower in Sodium. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1995, 95, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Farleigh, C.A.; Land, D.G. Preference and Sensitivity to Salt Taste as Determinants of Salt-intake. Appetite 1984, 5, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batenburg, M.; van der Velden, R. Saltiness Enhancement by Savory Aroma Compounds. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, S280–S288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.E.; Beauchamp, G.K. Flavor Modification by Sodium Chloride and Monosodium Glutamate. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, P.A.S.; Beauchamp, G.K. Suppression of bitterness by sodium: Variation among bitter taste stimuli. Chem. Senses 1995, 20, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaapila, A.; Laaksonen, O.; Virtanen, M.; Yang, B.; Lagström, H.; Sandell, M. Pleasantness, familiarity, and identification of spice odors are interrelated and enhanced by consumption of herbs and food neophilia. Appetite 2017, 109, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Methven, L.; Langreney, E.; Prescott, J. Changes in liking for a no added salt soup as a function of exposure. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 26, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandstra, E.H.; de Graaf, C.; van Trijp, H.C. Effects of variety and repeated in-home consumption on product acceptance. Appetite 2000, 35, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Smeets, A.; Lejeune, M.P.G. Sensory and gastrointestinal satiety effects of capsaicin on food intake. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregersen, N.T.; Belza, A.; Jensen, M.G.; Ritz, C.; Bitz, C.; Hels, O.; Frandsen, E.; Mela, D.J.; Astrup, A. Acute effects of mustard, horseradish, black pepper and ginger on energy expenditure, appetite, ad libitum energy intake and energy balance in human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelam, B. Satiation, satiety and their effects on eating behaviour. Nutr. Bull. 2009, 34, 126–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Duncan, A.M. The role of pulses in satiety, food intake and body weight management. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 38, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | Quantities |

|---|---|

| Cooked chickpeas (Sabarot, France) | 371 g |

| Cooked red lentils (Sabarot, France) | 159 g |

| Olive oil (18:1, Alexis Munoz, France) | 185 g |

| Tahini (spread made from ground sesame seeds, Al Wadi Al Akhdar, France) | 37 g |

| Lemon juice (pressed from fresh lemon, Bail distribution, France) | 45 g |

| Water | 203 g |

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Gender | 50% men/50% women |

| Age | 18–35 years inclusive |

| Body mass index, BMI (kg/m²) 1 | 18.5–30 kg/m² inclusive |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

| Participation in phase I tests | |

| Special diet (on weight loss diet, vegetarian, or any dietary restriction) | |

| Food allergies or intolerances to study products | |

| Pregnancy or breastfeeding | |

| Any health problems that could affect taste, smell, or appetite | |

| Cognitively restrained eaters 2 | |

| Athletes in training (>10 h of sport/week) | |

| Nutritional Values per 100 g and Serving Portion | Crackers | Mezze * | Lasagna | Bread | Yogurt | Apple | Meal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 28 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 400 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 125 | 100 | 85 | 753 | |

| Energy (kcal) | 388 | 111 | 217 | 163 | 132 | 528 | 253 | 101 | 93 | 116 | 54 | 46 | 1065 |

| Fat (g) | 2.7 | 0.8 | 18.5 | 13.9 | 5.5 | 22 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 0.25 | 0.2 | 41.1 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 0.6 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 9.6 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 2 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 14.3 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 75.2 | 21.4 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 13 | 52 | 52 | 20.8 | 12.6 | 15.7 | 11.6 | 9.9 | 126.5 |

| Sugars (g) | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 9.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 12.6 | 15.7 | 9.3 | 7.9 | 34.1 |

| Fibers (g) | 4.5 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 5.2 |

| Proteins (g) | 13.4 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 6.8 | 27.2 | 7.9 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 42.3 |

| Salt (g) 1 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 4.4 |

| Test Products | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS | LSHS | S | SHS | ||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | p-Value | |

| Appetite profile1,2 | |||||||||

| Hunger (mm) | 28.2 | 1.2 | 29.4 | 1.2 | 27.9 | 1.2 | 30.4 | 1.2 | 0.209 |

| Fullness (mm) | 67.7 a | 1.5 | 63.1 b | 1.5 | 68.8 a | 1.5 | 66.0 a,b | 1.5 | 0.009 |

| Desire to eat (mm) | 27.5 | 1.3 | 28.0 | 1.3 | 27.3 | 1.3 | 30.2 | 1.3 | 0.143 |

| Prospective intake (mm) | 26.6 | 1.3 | 27.5 | 1.3 | 27.2 | 1.3 | 28.7 | 1.3 | 0.417 |

| Overall appetite (mm) | 28.6 | 1.1 | 30.4 | 1.1 | 28.4 | 1.1 | 30.8 | 1.1 | 0.106 |

| Intake1 | |||||||||

| Legume mezzes (g) | 63.4 | 2.9 | 64.5 | 2.9 | 64.4 | 2.9 | 63.2 | 2.9 | 0.864 |

| Salt-free crackers (g) | 22.8 | 1.0 | 21.8 | 1.0 | 20.8 | 1.0 | 22.6 | 1.0 | 0.084 |

| Starter’s energy (kcal) | 237 | 9 | 236 | 9 | 231 | 9 | 235 | 9 | 0.870 |

| Eating behaviour1 | |||||||||

| Eating rate (bites/min) | 2.8 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 0.2 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 0.067 |

| Number of bites | 25.6 | 1.8 | 26.1 | 1.8 | 26.1 | 1.8 | 27.2 | 1.8 | 0.657 |

| Number of sips | 5.2 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 5.5 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 0.329 |

| Consumption time (min) | 9.1 | 0.6 | 8.5 | 0.6 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 9.0 | 0.6 | 0.576 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dougkas, A.; Vannereux, M.; Giboreau, A. The Impact of Herbs and Spices on Increasing the Appreciation and Intake of Low-Salt Legume-Based Meals. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122901

Dougkas A, Vannereux M, Giboreau A. The Impact of Herbs and Spices on Increasing the Appreciation and Intake of Low-Salt Legume-Based Meals. Nutrients. 2019; 11(12):2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122901

Chicago/Turabian StyleDougkas, Anestis, Marine Vannereux, and Agnès Giboreau. 2019. "The Impact of Herbs and Spices on Increasing the Appreciation and Intake of Low-Salt Legume-Based Meals" Nutrients 11, no. 12: 2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122901

APA StyleDougkas, A., Vannereux, M., & Giboreau, A. (2019). The Impact of Herbs and Spices on Increasing the Appreciation and Intake of Low-Salt Legume-Based Meals. Nutrients, 11(12), 2901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122901