Exploring Patterns of Disturbed Eating in Psychosis: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

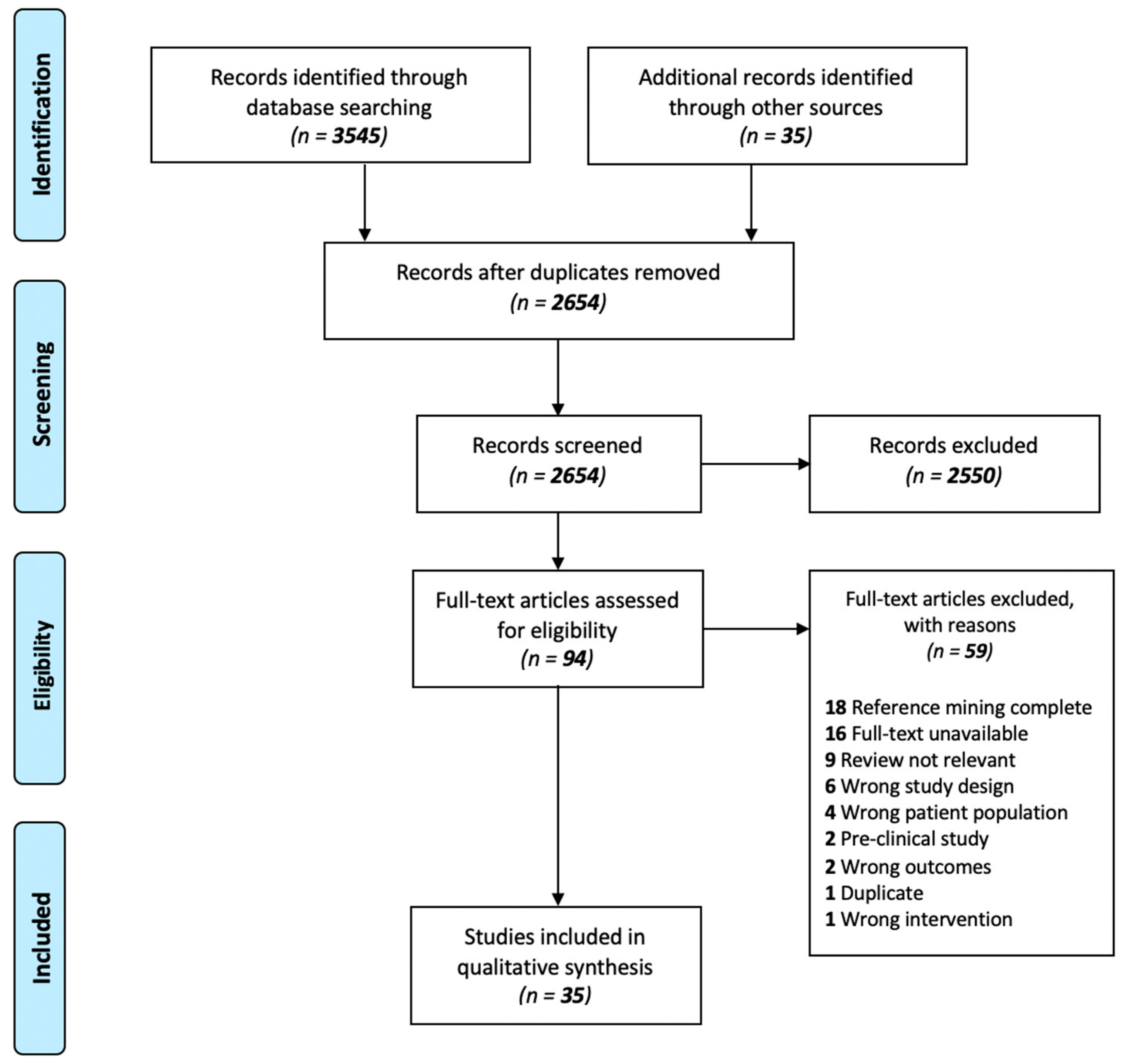

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Source of Evidence Screening and Study Selection

2.3. Charting the Data

2.4. Synthesis and Presentation of Results

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Findings from Subjective Food Preference and Dietary Composition Studies

3.2.1. Patients vs. Healthy Controls

3.2.2. Patients Only

3.2.3. Healthy Controls Only

3.3. Findings from Subjective/Self-Report Questionnaires on Appetite, Satiety and Craving

3.3.1. Binge Eating and Other Eating Disorder-Related Behaviours

3.3.2. Patients Only

3.3.3. Patients vs. Controls

3.4. Subjective Appetite, Hunger and Satiety

3.4.1. Patients Only

3.4.2. Patients vs. Healthy Controls

3.4.3. Controls Only

3.5. Findings from Neuroimaging and Brain Structure Studies

3.5.1. Patients Only

3.5.2. Patients vs. Healthy Controls

3.5.3. First Episode Patients vs. Controls

3.6. Healthy Controls Only

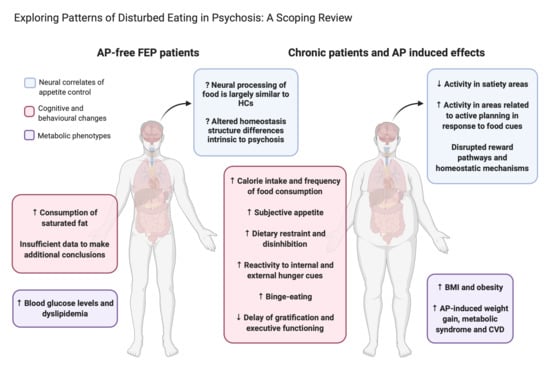

4. Discussion

4.1. Food Composition and Dietary Preference

4.2. Eating Behaviour, Cravings and Subjective Appetite

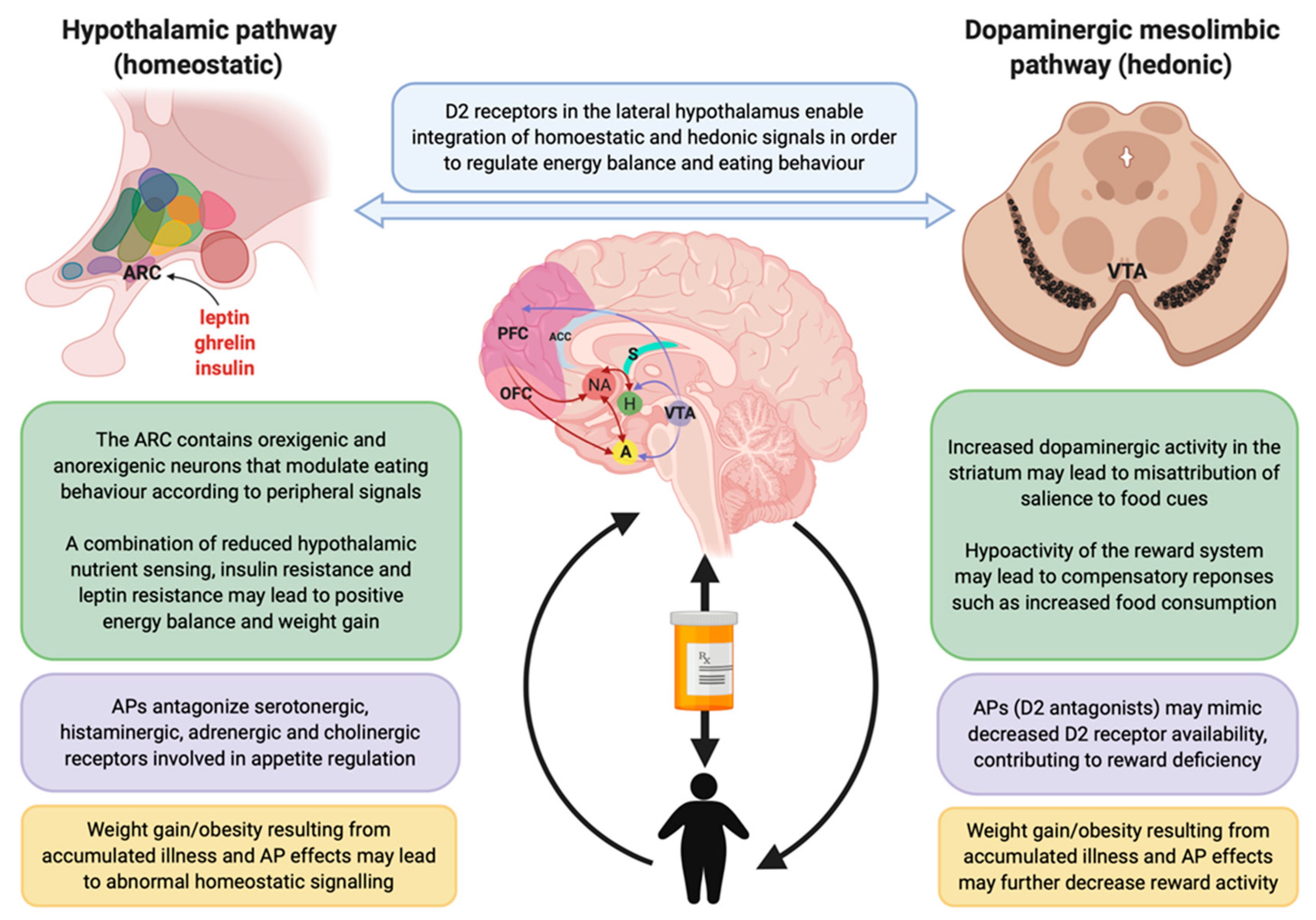

4.3. Neural Correlates of Appetite and Eating Behavior

4.4. Postulated Neurobiological Mechanisms Involved in Appetite/Feeding Regulation

4.5. Hedonic Reward Mechanisms

4.6. Homeostatic Mechanisms

4.7. Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prentice, P. Psychosis and schizophrenia. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2013, 98, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Küstner, B.; Martín, C.; Pastor, L. Prevalence of psychotic disorders and its association with methodological issues. A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arciniengas, D.B. Psychosis. Continuum 2015, 21, 715–736. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, C.R.; Harvey, P.D. Cognition in schizophrenia: Impairments, determinants, and functional importance. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 28, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, P.D.; Strassnig, M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: Cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maric, N.P.; Jovicic, M.J.; Mihaljevic, M.; Miljevic, C. Improving current treatments for schizophrenia. Drug Dev. Res. 2016, 77, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Cohen, D.; Bobes, J.; Cetkovich-Bakmas, M.; Leucht, S.; Ndetei, D.M.; Newcomer, J.W.; Uwakwe, R.; Asai, I.; Möller, H.J.; et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennekens, C.H.; Hennekens, A.R.; Hollar, D.; Casey, D.E. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am. Heart J. 2005, 150, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredentser, M.S.; Martens, P.J.; Chochinov, H.M.; Prior, H.J. Cause and rate of death in people with schizophrenia across the lifespan: A population-based study in Manitoba, Canada. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, A.P.; Horsdal, H.T.; Wimberley, T.; Cohen, D.; Mors, O.; Borglum, A.D.; Gasse, C. Endogenous and antipsychotic-related risks for diabetes mellitus in young people with schizophrenia: A Danish population-based cohort study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musil, R.; Obermeier, M.; Russ, P.; Hamerle, M. Weight gain and antipsychotics: A drug safety review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2015, 14, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Jiménez, M.; González-Blanch, C.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; Hetrick, S.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.M.; Pérez-Iglesias, R.; Vázquez-Barquero, J.L. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in chronic and first-episode psychotic disorders: A systematic critical reappraisal. CNS Drugs 2008, 22, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.O.; Wyatt, H.R.; Peters, J.C. The importance of energy balance. Eur. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipasquale, S.; Pariante, C.M.; Dazzan, P.; Aguglia, E.; McGuire, P.; Mondelli, V. The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, A.; Pendlebury, J.; Anderson, S.; Narayan, V.; Guy, M.; Gibson, M.; Haddad, P.; Livingston, M. Lifestyle factors and the metabolic syndrome in Schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2017, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvisaari, J.; Keinänen, J.; Eskelinen, S.; Mantere, O. Diabetes and Schizophrenia. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2016, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouidrat, Y.; Amad, A.; Lalau, J.D.; Loas, G. Eating disorders in schizophrenia: Implications for research and management. Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 791573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak, B.; Stańczykiewicz, B.; Łaczmański, Ł.; Frydecka, D. Lipid profile disturbances in antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode non-affective psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 190, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, A.M.; Gonzalez-Blanco, L.; Garcia-Rizo, C.; Fernandez-Egea, E.; Miller, B.; Arroyo, M.B.; Kirkpatrick, B. Meta-analysis of glucose tolerance, insulin, and insulin resistance in antipsychotic-naïve patients with nonaffective psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 179, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, M.; Stanczykiewicz, B.; Liskiewicz, P.; Misiak, B. Impaired hormonal regulation of appetite in schizophrenia: A narrative review dissecting intrinsic mechanisms and the effects of antipsychotics. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 119, 104744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benarroch, L.; Kowalchuk, C.; Wilson, V.; Teo, C.; Guenette, M.; Chintoh, A.; Nesarajah, Y.; Taylor, V.; Selby, P.; Fletcher, P.; et al. Atypical antipsychotics and effects on feeding: From mice to men. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 2629–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Clerici, M.; Carrà, G. Second-generation antipsychotics and adiponectin levels in schizophrenia: A comparative meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, R.L.; Miller, B.J. Meta-analysis of ghrelin alterations in schizophrenia: Effects of olanzapine. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 206, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matafome, P.; Seiça, R. The role of brain in energy balance. Adv. Neurobiol. 2017, 19, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.H.; Vasselli, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Mechanick, J.I.; Korner, J.; Peterli, R. Metabolic vs. hedonic obesity: A conceptual distinction and its clinical implications. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teff, K.L.; Kim, S.F. Atypical antipsychotics and the neural regulation of food intake and peripheral metabolism. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 104, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinoff, B. Neurobiologic processes in drug reward and addiction. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2004, 12, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, E.; Song, D.K.; Kim, M.S. Emerging role of the brain in the homeostatic regulation of energy and glucose metabolism. Nat. Publ. Group 2016, 48, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Lindroos, A.-K.; Lissner, L.; Mathiassen, M.E.; Karlsson, J.; Sullivan, M.; Bengtsson, C.; Sjöström, L. Dietary intake in relation to restrained eating, disinhibition, and hunger in obese and nonobese Swedish women. Obes. Res. 1997, 5, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westenhoefer, J.; Stunkard, A.J.; Pudel, V. Validation of the flexible and rigid control dimensions of dietary restraint. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 26, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, S.W. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2001, 14, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löffler, A.; Luck, T.; Then, F.S.; Sikorski, C.; Kovacs, P.; Böttcher, Y.; Breitfeld, J.; Tönjes, A.; Horstmann, A.; Löffler, M.; et al. Eating behaviour in the general population: An analysis of the factor structure of the German version of the Three-Factor-Eating-Questionnaire (TFEQ) and its association with the body mass index. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohrer, B.K.; Forbush, K.T.; Hunt, T.K. Are common measures of dietary restraint and disinhibited eating reliable and valid in obese persons? Appetite 2015, 87, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, E.J.; Rehman, J.; Pepper, L.B.; Walters, E.R. Obesity and eating disturbance: The role of TFEQ restraint and disinhibition. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Lee, K.; Song, Y.M. Relationship of eating behavior to long-term weight change and body mass index: The Healthy Twin study. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2009, 14, e98–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Herman, C.P.; Verheijden, M.W. Eating style, overeating, and overweight in a representative Dutch sample. Does external eating play a role? Appetite 2009, 52, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenders, P.G.; van Strien, T. Emotional eating, rather than lifestyle behavior, drives weight gain in a prospective study in 1562 employees. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, C.; Hopkins, M.; Beaulieu, K.; Oustric, P.; Blundell, J.E. Issues in measuring and interpreting human appetite (satiety/satiation) and its contribution to obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkard, A.J.; Messick, S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J. Psychosom. Res. 1985, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinai, P.; Da Ros, A.; Speciale, M.; Gentile, N.; Tagliabue, A.; Vinai, P.; Bruno, C.; Vinai, L.; Studt, S.; Cardetti, S. Psychopathological characteristics of patients seeking for bariatric surgery, either affected or not by binge eating disorder following the criteria of the DSM IV TR and of the DSM 5. Eat. Behav. 2015, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bas, M.; Bozan, N.; Cigerim, N. Dieting, dietary restraint, and binge eating disorder among overweight adolescents in Turkey. Adolescence 2008, 43, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Strien, T.; Peter Herman, C.; Verheijden, M.W. Eating style, overeating and weight gain. A prospective 2-year follow-up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite 2012, 59, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, R.J.; Hughes, D.A.; Johnstone, A.M.; Rowley, E.; Reid, C.; Elia, M.; Stratton, R.; Delargy, H.; King, N.; Blundell, J.E. The use of visual analogue scales to assess motivation to eat in human subjects: A review of their reliability and validity with an evaluation of new hand-held computerized systems for temporal tracking of appetite ratings. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepeda-Benito, A.; Gleaves, D.H.; Williams, T.L.; Erath, S.A. The development and validation of the state and trait food-cravings questionnaires. Behav. Ther. 2000, 31, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Whisenhunt, B.L.; Williamson, D.A.; Greenway, F.L.; Netemeyer, R.G. Development and validation of the food-craving inventory. Obes. Res. 2002, 10, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Noh, J.; Nam, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.; Hong, K. Development and validation of drug-related eating behavior questionnaire in patients receiving antipsychotic medications. Korean J. Schizophr. Res. 2008, 11, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, S.; Nam, H.J.; Oh, S.; Park, T.; Lim, M.; Choi, J.S.; Baek, J.H.; Jang, J.H.; Park, H.Y.; Kim, S.N.; et al. Eating-behavior changes associated with antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia as measured by the Drug-Related Eating Behavior Questionnaire. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Yanovski, S.; Wadden, T.; Wing, R.; Marcus, M.D.; Stunkard, A.; Devlin, M.; Mitchell, J.; Hasin, D.; Horne, R.L. Binge eating disorder: Its further validation in a multisite study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1993, 13, 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mizes, J.S.; Christiano, B.; Madison, J.; Post, G.; Seime, R.; Varnado, P. Development of the mizes anorectic cognitions questionnaire-revised: Psychometric properties and factor structure in a large sample of eating disorder patients. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000, 28, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountaine, R.J.; Taylor, A.E.; Mancuso, J.P.; Greenway, F.L.; Byerley, L.O.; Smith, S.R.; Most, M.M.; Fryburg, D.A. Increased food intake and energy expenditure following administration of olanzapine to healthy men. Obesity 2010, 18, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gothelf, D.; Falk, B.; Singer, P.; Kairi, M.; Phillip, M.; Zigel, L.; Poraz, I.; Frishman, S.; Constantini, N.; Zalsman, G.; et al. Weight Gain Associated With Increased Food Intake and Low Habitual Activity Levels in Male Adolescent Schizophrenic Inpatients Treated With Olanzapine. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1055–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amani, R. Is dietary pattern of schizophrenia patients different from healthy subjects? BMC Psychiatry 2007, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eder, U.; Mangweth, B.; Ebenbichler, C.; Weiss, E.; Hofer, A.; Hummer, M.; Kemmler, G.; Lechleitner, M.; Fleischhacker, W.W. Association of olanzapine-induced weight gain with an increase in body fat. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1719–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattere, G.; Stojanovic-Perez, A.; Monseny, R.; Martorell, L.; Ortega, L.; Montalvo, I.; Sole, M.; Algora, M.J.; Cabezas, A.; Reynolds, R.M.; et al. Gene-environment interaction between the brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism, psychosocial stress and dietary intake in early psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 12, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, D.; Eskinazi, B.; Camboim Rockett, F.; Delgado, V.B.; Schweigert Perry, I.D. Nutritional status, food intake and cardiovascular disease risk in individuals with schizophrenia in southern Brazil: A case–control study. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2014, 7, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strassnig, M.; Singh Brar, J.; Qanguli, R. Nutritional assessment of patients with schizophrenia: A preliminary study. Schizophr. Bull. 2003, 29, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanska, E.; Lech, M.; Wendołowicz, A.; Konarzewska, B.; Waszkiewicz, N.; Ostrowska, L. Eating habits and nutritional status of patients with affective disorders and schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefańska, E.; Wendołowicz, A.; Lech, M.; Wilczyńska, K.; Konarzewska, B.; Zapolska, J.; Ostrowska, L. The assessment of the nutritional value of meals consumed by patients with recognized schizophrenia. Rocz. Państwowego Zakładu Hig. 2018, 69, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Khazaal, Y.; Fresard, E.; Zimmermann, G.; Trombert, N.M.; Pomini, V.; Grasset, F.; Borgeat, F.; Zullino, D. Eating and weight related cognitions in people with Schizophrenia: A case control study. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH 2006, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brömel, T.; Blum, W.F.; Ziegler, A.; Schulz, E.; Bender, M.; Fleischhaker, C.; Remschmidt, H.; Krieg, J.C.; Hebebrand, J. Serum leptin levels increase rapidly after initiation of clozapine therapy. Mol. Psychiatry 1998, 3, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, S.; Haberhausen, M.; Krieg, J.C.; Remschmidt, H.; Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M.; Hebebrand, J.; Theisen, F.M. Clozapine/olanzapine-induced recurrence or deterioration of binge eating-related eating disorders. J. Neural Transm. 2007, 114, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluge, M.; Schuld, A.; Himmerich, H.; Dalal, M.; Schacht, A.; Wehmeier, P.M.; Hinze-Selch, D.; Kraus, T.; Dittmann, R.W.; Pollmächer, T. Clozapine and olanzapine are associated with food craving and binge eating: Results from a randomized double-blind study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisen, F.M.; Linden, A.; König, I.R.; Martin, M.; Remschmidt, H.; Hebebrand, J. Spectrum of binge eating symptomatology in patients treated with clozapine and olanzapine. J. Neural Transm. 2003, 110, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuer, T.; Hoffmann, V.P.; Chen, A.K.-P.; Irimia, V.; Ocampo, M.; Wang, G.; Singh, P.; Holt, S. Factors associated with weight gain during olanzapine treatment in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: Results from a six-month prospective, multinational, observational study. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 10, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaal, Y.; Frésard, E.; Borgeat, F.; Zullino, D. Binge eating symptomatology in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia: A case control study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, M.; Mallorqui, A.; Serrano, L.; Rios, J.; Salamero, M.; Parellada, E.; Gomez-Ramiro, M.; Oliveira, C.; Amoretti, S.; Vieta, E.; et al. Food craving and consumption evolution in patients starting treatment with clozapine. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 3317–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagianis, J.; Grossman, L.; Landry, J.; Reed, V.A.; de Haan, L.; Maguire, G.A.; Hoffmann, V.P.; Milev, R. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of sublingual orally disintegrating olanzapine versus oral olanzapine on body mass index: The PLATYPUS Study. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 113, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.C.; Rachakonda, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Davis, J.M. Olanzapine and risperidone effects on appetite and ghrelin in chronic schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 199, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentissi, O.; Viala, A.; Bourdel, M.C.; Kaminski, F.; Bellisle, F.; Olie, J.P.; Poirier, M.F. Impact of antipsychotic treatments on the motivation to eat: Preliminary results in 153 schizophrenic patients. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 24, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M.J.; Liddle, P.F. Olanzapine and food craving: A case control study. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 28, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blouin, M.; Tremblay, A.; Jalbert, M.E.; Venables, H.; Bouchard, R.H.; Roy, M.A.; Alméras, N. Adiposity and eating behaviors in patients under second generation antipsychotics. Obesity 2008, 16, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folley, B.S.; Park, S. Relative food preference and hedonic judgments in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 175, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knolle-Veentjer, S.; Huth, V.; Ferstl, R.; Aldenhoff, J.B.; Hinze-Selch, D. Delay of gratification and executive performance in individuals with schizophrenia: Putative role for eating behavior and body weight regulation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 42, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schanze, A.; Reulbach, U.; Scheuchenzuber, M.; Groschl, M.; Kornhuber, J.; Kraus, T. Ghrelin and eating disturbances in psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychobiology 2008, 57, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roerig, J.L.; Mitchell, J.E.; de Zwaan, M.; Crosby, R.D.; Gosnell, B.A.; Steffen, K.J.; Wonderlich, S.A. A comparison of the effects of olanzapine and risperidone versus placebo on eating behaviors. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 25, 413–418. [Google Scholar]

- Teff, K.L.; Rickels, K.; Alshehabi, E.; Rickels, M.R. Metabolic impairments precede changes in hunger and food intake following short-term administration of second-generation antipsychotics. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 35, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teff, K.L.; Rickels, M.R.; Grudziak, J.; Fuller, C.; Nguyen, H.-L.; Rickels, K. Antipsychotic-induced insulin resistance and postprandial hormonal dysregulation independent of weight gain or psychiatric disease. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3232–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, C.A.; Busto, U.; Sellers, E.M.; Sandor, P.; Ruiz, I.; Roberts, E.A.; Janecek, E.; Domecq, C.; Greenblatt, D.J. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1981, 30, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, O.; Vollstadt-Klein, S.; Krebs, L.; Zink, M.; Smolka, M.N. Reduced striatal activation during reward anticipation due to appetite-provoking cues in chronic schizophrenia: A fMRI study. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 134, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lungu, O.; Anselmo, K.; Letourneau, G.; Mendrek, A.; Stip, B.; Lipp, O.; Lalonde, P.; Ait Bentaleb, L.; Stip, E. Neuronal correlates of appetite regulation in patients with schizophrenia: Is there a basis for future appetite dysfunction? Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2013, 28, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stip, E.; Lungu, O.V. Salience network and olanzapine in schizophrenia: Implications for treatment in anorexia nervosa. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2015, 60, S35–S39. [Google Scholar]

- Stip, E.; Lungu, O.V.; Anselmo, K.; Letourneau, G.; Mendrek, A.; Stip, B.; Lipp, O.; Lalonde, P.; Bentaleb, L.A. Neural changes associated with appetite information processing in schizophrenic patients after 16 weeks of olanzapine treatment. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgan, F.; O’Daly, O.; Hoang, K.; Veronese, M.; Withers, D.; Batterham, R.; Howes, O. Neural responsivity to food cues in patients with unmedicated first-episode psychosis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e186893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.; Newcomer, J.W.; Mathews, J.R.; Fales, C.L.; Pierce, K.J.; Akers, B.K.; Marcu, I.; Barch, D.M. Neural correlates of weight gain with olanzapine. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 1226–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsley, R.; Asmal, L.; Chiliza, B.; du Plessis, S.; Carr, J.; Kidd, M.; Malhotra, A.K.; Vink, M.; Kahn, R.S. Changes in brain regions associated with food-intake regulation, body mass and metabolic profiles during acute antipsychotic treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 233, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, S.; Haberhausen, M.; Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M.; Gebhardt, N.; Remschmidt, H.; Krieg, J.C.; Hebebrand, J.; Theisen, F.M. Antipsychotic-induced body weight gain: Predictors and a systematic categorization of the long-term weight course. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009, 43, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancampfort, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Schuch, F.B.; Ward, P.B.; Probst, M.; Stubbs, B. Prevalence and predictors of treatment dropout from physical activity interventions in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 39, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrou, I.; Tsigos, C. Chronic stress, visceral obesity and gonadal dysfunction. Hormones 2008, 7, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallman, M.F.; Pecoraro, N.; Akana, S.F.; La Fleur, S.E.; Gomez, F.; Houshyar, H.; Bell, M.E.; Bhatnagar, S.; Laugero, K.D.; Manalo, S. Chronic stress and obesity: A new view of “comfort food”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11696–11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, K.S.; Stice, E. Relation of dietary restraint scores to activation of reward-related brain regions in response to food intake, anticipated intake, and food pictures. NeuroImage 2011, 55, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinella, M.; Lyke, J. Executive personality traits and eating behavior. Int. J. Neurosci. 2004, 114, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, M.; Treuer, T.; Karagianis, J.; Hoffmann, V.P. The potential role of appetite in predicting weight changes during treatment with olanzapine. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cardinal, R.N.; Parkinson, J.A.; Hall, J.; Everitt, B.J. Emotion and motivation: The role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2002, 26, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moal, M.; Simon, H. Mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic network: Functional and regulatory roles. Physiol. Rev. 1991, 71, 155–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W. Dopamine neurons and their role in reward mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1997, 7, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, K.C. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: The case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 2007, 191, 391–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, D.; Vernon, A.C.; Papaleo, F. Dopamine, the antipsychotic molecule: A perspective on mechanisms underlying antipsychotic response variability. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 85, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: A framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, R.A.; Abi-Dargham, A.; Howes, O.D. Schizophrenia, dopamine and the striatum: From biology to symptoms. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, M.M.; Dahoun, T.; Schwartenbeck, P.; Adams, R.A.; FitzGerald, T.H.B.; Coello, C.; Wall, M.B.; Dolan, R.J.; Howes, O.D. Dopaminergic basis for signaling belief updates, but not surprise, and the link to paranoia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E10167–E10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, J.J.; Cohen, A.S. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: Implications for assessment. Schizophr. Bull. 2006, 32, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, G.P.; Waltz, J.A.; Gold, J.M. A review of reward processing and motivational impairment in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2014, 40, S107–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Spoor, S.; Bohon, C.; Veldhuizen, M.G.; Small, D.M. Relation of reward from food intake and anticipated food intake to obesity: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008, 117, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minzenberg, M.J.; Laird, A.R.; Thelen, S.; Carter, C.S.; Glahn, D.C. Meta-analysis of 41 functional neuroimaging studies of executive function in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaal, Y.; Billieux, J.; Fresard, E.; Huguelet, P.; van der Linden, M.; Zullino, D. A Measure of dysfunctional eating-related cognitions in people with psychotic disorders. Psychiatr. Q. 2010, 81, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.; Young, H.A. A meta-analysis of the relationship between brain dopamine receptors and obesity: A matter of changes in behavior rather than food addiction? Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, S12–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.; Chintoh, A.; Giacca, A.; Xu, L.; Lam, L.; Mann, S.; Fletcher, P.; Guenette, M.; Cohn, T.; Wolever, T.; et al. Atypical antipsychotics and effects of muscarinic, serotonergic, dopaminergic and histaminergic receptor binding on insulin secretion in vivo: An animal model. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 131, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahima, R.S.; Antwi, D.A. Brain regulation of appetite and satiety. NIH Public Access 2008, 37, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.M.; Caravaggio, F.; Costa-Dookhan, K.A.; Castellani, L.; Kowalchuk, C.; Asgariroozbehani, R.; Graff-Guerrero, A.; Hahn, M. Brain insulin action in schizophrenia: Something borrowed and something new. Neuropharmacology 2020, 163, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, N.E.; Kowalchuk, C.; Agarwal, S.M.; Costa-Dookhan, K.A.; Caravaggio, F.; Gerretsen, P.; Chintoh, A.; Remington, G.J.; Taylor, V.H.; Mueller, D.J.; et al. Antipsychotics, metabolic adverse effects, and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B.L.; Claassen, N.; Becker, P.; Viljoen, M. Validity of commonly used heart rate variability markers of autonomic nervous system function. Neuropsychobiology 2019, 78, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkheimer, F.E.; Selvaggi, P.; Mehta, M.A.; Veronese, M.; Zelaya, F.; Dazzan, P.; Vernon, A.C. Normalizing the abnormal: Do antipsychotic drugs push the cortex into an unsustainable metabolic envelope? Schizophr. Bull. 2020, 46, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, C.H. It’s all a matter of taste: Gustatory processing and ingestive decisions. MO Med. 2010, 107, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vancampfort, D.; Knapen, J.; Probst, M.; van Winkel, R.; Deckx, S.; Maurissen, K.; Peuskens, J.; de Hert, M. Considering a frame of reference for physical activity research related to the cardiometabolic risk profile in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 177, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Vancampfort, D.; Sweers, K.; van Winkel, R.; Yu, W.; de Hert, M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garawi, F.; Devries, K.; Thorogood, N.; Uauy, R. Global differences between women and men in the prevalence of obesity: Is there an association with gender inequality? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, P.; Smit, H.J.; Lightowler, H.J. The influence of restrained and external eating patterns on overeating. Appetite 2007, 49, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellisle, F.; Clément, K.; Le Barzic, M.; Le Gall, A.; Guy-Grand, B.; Basdevant, A. The eating inventory and body adiposity from leanness to massive obesity: A study of 2509 adults. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 2023–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, L.N.; Costa-Dookhan, K.A.; McIntyre, W.B.; Wright, D.C.; Flowers, S.A.; Hahn, M.K.; Ward, K.M. Preclinical and clinical sex differences in antipsychotic-induced metabolic disturbances: A narrative review of adiposity and glucose metabolism. J. Psychiatry Brain Sci. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, M.V. Men and women respond differently to antipsychotic drugs. Neuropharmacology 2020, 163, 107631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Extracted Data |

|---|

|

| Name | Original Source | Description | Subscales and Other Relevant Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) | Stunkard and Messick, 1985 [42] | 51-item questionnaire measuring three aspects of eating behaviour (cognitive restraint, disinhibition, hunger) |

|

| Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ) | Van Strien et al., 1986 [40] | 33-item questionnaire measuring three factors that regulate eating behaviour (restraint, emotion, external factors) |

|

| Visual Analog Scale (VAS) | Stubbs et al., 2000 (review) [46] | Psychometric tool used to quantify subjective appetite |

|

| Food Craving Questionnaire (FCQ) | Cepeda-Benito et al., 2000 [47] | Questionnaire measuring general food cravings (trait and state version) |

|

| Food Craving Inventory (FCI) | White et al., 2002 [48] | Questionnaire measuring specific food cravings (carbohydrates, sweets, fats, fast-food fats) |

|

| Drug-Related Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DR-EBQ) | Lim et al., 2008 [49] | 14-item questionnaire that quantifies changes in appetite, craving and eating behaviour after beginning antipsychotic treatment |

|

| Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns (QEWP) | Spitzer et al., 1993 [51] | Questionnaire used to evaluate the presence of binge-eating symptomatology and binge-eating related disorders |

|

| Mizes Anorectic Cognitions Questionnaire—Revised (MAC-R) | Mizes et al., 2000 [52] | 24-item questionnaire used to assess eating disorder-related cognitions (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder) |

|

| Study | Study Description | Main Significant Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design/Aim | Sample (Size, Diagnosis), Mean Age (Years), Mean BMI (kg/m2) | Sex (% F), Race/Ethnicity (%) | Illness Duration/Previous AP Exposure | Assessments | ||

| Amani 2007 [55] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Dietary preference in patients with SCZ compared to HC | 30 SCZ inpatients, 16–76 years Age: 32.3 (M), 32.5 (F) BMI: 22 (M), 26 (F) 30 HCs (matched for age, sex) Age: 35.6 (M), 36.6 (F) BMI: 25.6 (M), 25.4 (F) | SCZ: 37% F HC: 47% F | Illness duration: at least one year; previous AP exposure not stated | Dietary recall (FFQ) Food Guide Pyramid to calculate dietary scores |

|

| Eder 2001 [56] | Longitudinal (8 weeks) Association of olanzapine induced weight gain with an increase in body fat | 10 SCZ in patients treated with OLA monotherapy Dose range: 7.5–20 mg/d Age: 30.4 BMI: 22.4 10 HCs (matched for age, sex) Age: 35.2 BMI: 22.1 | SCZ: 20% F HC: 20% F | No APs prior to OLA: 5 Previous APs: 5 (flupentixol, fluphenazine, risperidone, or haloperidol) | Semi-standardized structured interview to assess changes in eating behaviour and physical activity |

|

| Fountaine 2010 [53] | Randomized, placebo controlled, two treatment crossover study (15 + 15 days, 12-day washout between arms) Comparing food intake and energy expenditure following olanzapine vs. placebo in healthy men | 30 male HCs (21 completers) Age: 27 (range: 18–49) BMI: 22.6 | All Males | N/A | Food intake monitored and weighed REE, daily activity level |

|

| Gattere 2018 [57] | Cross-sectional Dietary intake in early psychosis | 124 early psychotic disorder (PD), 82 (66.1%) FEP patients with <5 years from illness onset Schizophreniform: n = 22 Schizoaffective: n = 12 Psychotic disorder NOS: n = 70 Age: 24.7 BMI: 24.3 36 at-risk mental state (ARMS) Age: 22.2 BMI: 22.2 62 HCs (not matched) Age: 23.5 BMI: 22.2 | PD: 34.7% F; 76.6% Caucasian, 9.7% Latino American, 8.1% Arabian, 4.0% Gypsy, 0.8% Black, 0.8% Asian ARMS: 27.8% F; 88.9% Caucasian, 8.3% Latino American, 2.8 Arabian HC: 48.4% F; 95.2% Caucasian, 3.2% Latino America, 1.6% Arabian | PD: Monotherapy: 72 (58.1%) RIS = 31 PAL = 13 OLA = 17 QUE = 1 ARI = 10 Combination: 33 (26.6%) No APs: 19 (15.3%) ARMS: Monotherapy: 7 (19.4%) RIS = 1 OLA = 3 ARI = 3 Combination: 3 (8.3%) No APs: 27 (75%) | 24-h dietary recall Food Craving (FCQ-State) IPAQ-short form |

|

| Gothelf 2002 [54] | Longitudinal (4 weeks) Food intake and weight gain in adolescent males with SCZ treated with OLA vs. HAL | 20 male SCZ inpatients OLA: n = 10 (MD: 14 mg/d) HAL: n = 10 (MD: 6.5 mg/d) Age (both): 17 BMI (OLA only): 24.5 | All Males | OLA: mean washout period = 17.6 days Drug naïve = 1 Clomipramine = 1 AP other than OLA = 8 | Dietary Evaluation (2-day monitoring of food intake by dietician; food weighed) Daily energy expenditure, REE, physical activity |

|

| Nunes 2014 [58] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Evaluating nutritional status, food intake and cardiovascular disease risk in SCZ patients | 25 SCZ outpatients Age: 40.5 (range: 18–59) BMI: 29.09 25 HCs (matched for age, sex, BMI) Age: 37.2 BMI: 26.91 Total sample Age: 38.9 BMI: 28.0 | SCZ: 40% F HC: 48% F | SGA = 68% FGA = 28% Both = 4% | Dietary recall (FFQ) |

|

| Strassnig 2003 [59] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Exploring potential causes of weight gain in SCZ patients compared to general population (NHANES III) | 146 outpatients with psychosis SCZ, paranoid type: n = 69 Schizoaffective: n = 53 Psychotic disorder NOS: n = 24 Age: 43 BMI: 32.7 Patient data compared to general population (NHANES III) | 47% F 54% White, 46% Black | NR | 24-h dietary recall |

|

| Stefanska 2017 [60] | Cross-sectional Eating habits and nutritional status in patients with SCZ and affective disorders | 60 SCZ, 18–67 years Age: 34.1 (M), 41.3 (F) BMI: 27.6 (M), 27.2 (F) 61 recurrent depressive disorder, 18–67 years Age: 38.0 (M), 46.4 (F) BMI: 26.1 (M), 26.7 (F) 98 HCs (not matched), Age: 33.0 (M), 43.0 (F) (range: 18–69 years) BMI: 27.3 (M), 25.8 (F) | SCZ: 53.3% F Depression: 54.1% F HCs: 61.2% F | AP treatment (FGA or SGA) for at least one year (AP type not specified) Age at onset: 23.3 (M), 30.1 (F) Illness duration (years): 9.5 (M), 10.4 (F) | 24-h dietary recall Resting metabolic rate (RMR) |

|

| Stefanska 2018 [61] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Assessing the nutritional value males consumed by patients with SCZ | 85 SCZ outpatients, 18–65 years Age: 37.8 (M), 39.0 (F) BMI: 25.0 (M), 25.1 (F) 70 HCs (not matched) Age: 35.9 (M), 38.2 (F) BMI: 25.9 (M), 24.4 (F) | SCZ: 52.9% F HC: 57.1% F | AP treatment (FGA or SGA) for at least one year (AP type not specified) 1 AP = 39% 2 or 3 APs = 61% Age at onset: 26.7 (M), 273 (F) Illness duration (years): 10.0 (M), 12.3 (F) | 24-h dietary recall |

|

| Study | Study Description | Main Significant Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design/Aim | Sample (Size, Diagnosis), Mean Age (Years), Mean BMI (kg/m2) | Sex (% F), Race/Ethnicity | Mean Illness Duration/Previous AP Exposure (n) | Assessments | ||

| Bromel 1998 [63] | Longitudinal (10 weeks) Effect of CLZ on food craving in patients with SCZ | 12 SCZ in patients treated with CLZ (MD: 273 mg/d; range: 81–475 mg/d) SCZ: n = 9 FGA: n = 3 Age: 31 (range: 18–65) BMI: 25.8 | 50% F | Nine patients treated with psychotropic medication (including APs) prior to starting CLZ (type/duration of previous exposure not specified) | Binge eating/ED symptomatology (DSM-IV) Binary appetite/craving scale |

|

| Gebhardt 2007 [64] | Longitudinal (retrospective) Binge-eating symptomatology associated with CLZ and OLA use in patients with psychosis | 64 patients being treated for psychotic symptoms with CLZ or OLA SCZ: 52.3% SCZ spectrum disorder: 12.3% Mood disorder: 18.5% Substance abuse: 7.7% Personality disorder: 3.1% Other diagnoses: 7.7% Age: 30.7 (range: 13.3–64.6) | 47% F | Patients were treated with CLZ or OLA for at least 4 weeks prior to inclusion in study CLZ: n = 33 OLA: n = 31 | QEWP (DSM-IV binge-eating) Adverse drug reaction (ADR) scale Appetite (4-point Likert-type scale) |

|

| Kluge 2007 [65] | Randomized, double blind, parallel (6 weeks) Effect of CLZ and OLA on food craving and binge eating in patients with SCZ spectrum disorders | 30 SCZ (n = 26), Schizoaffective (n = 3), Schizophreniform (n = 1) inpatients, 18–65 years CLZ: n = 15 OLA: n = 15 Age: 36.7 (CLZ), 32.8 (OLA) BMI: 25.4 (CLZ), 24.4 (OLA) Dosing (last 4 weeks of study): mean modal dose = 266.7 mg (CLZ), 21.2 mg (OLA) | CLZ: 53% F OLA: 67% F | Age of illness onset: 30 (CLZ), 28 (OLA) | Binge eating/ED symptomatology (DSM-IV) Binary appetite/craving scale |

|

| Theisen 2003 [66] | Cross-sectional (BE vs. non-BE) with an exploratory retrospective analysis Comparing binge eating symptomatology in patients with SCZ treated with clozapine and olanzapine | 74 SCZ inpatients CLZ: n = 57 OLA: n = 17 Age: 19.8 (range: 15.6–26.6) Two sub-groups based on prevalence of binge eating behaviour Binge eating (BE): n =37 Non-binge eating (non-BE): n = 37 | 36% F | Illness duration (years): 2.4 (range = 0.3–7.1) | QEWP (DSM-IV binge-eating) |

|

| Treuer 2009 [67] | Longitudinal (6 months) Food intake and nutritional factors associated with weight gain in patients with SCZ and BD treated with OLA | 622 SCZ or BD outpatients (589 completers) treated with OLA (MD: 11.4 mg/d; mean duration during study: 5.4 months) SCZ: 85% of sample BD: 15% of sample Age: 32.6 years BMI: 23.2 | 56% F Multinational (China, Romania, Mexico, Taiwan) 61% East Asian, 25% Caucasian, 14% Hispanic | Lifetime AP exposure: 74.5% of sample (duration not specified) Past 6 months: 45.2% of sample | Interview to assess appetite (5-point Likert), frequency of food consumption, subjective energy levels and physical activity |

|

| Khazaal 2006a * [62] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Eating and weight related cognitions in patients with SCZ vs. HCs | 40 SGA-treated SCZ outpatients Age: 33.8 40 HCs (matched for BMI) Age: 35.5 Two subgroups (n = 20) for each group: Overweight = BMI > 28 Comparison = BMI < 28 | SCZ: 47.5% F HC: 52.5% F | Previous AP exposure (mean duration = 8.3 years): OLA, CLZ, QUE, RIS | Revised version of the Mizes Anorectic cognitive questionnaire (MAC-R) |

|

| Khazaal 2006b * [68] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Binge eating symptomatology in overweight and obese patients with SCZ vs. HCs | 40 SGA-treated SCZ outpatients Age: 33.8 40 HCs (matched for BMI) Age: 35.5 Two subgroups (n = 20) for each group: Overweight = BMI > 28 Comparison = BMI < 28 | SCZ: 47.5% F HC: 52.5% F | NR | Binge eating/ED symptomatology (DSM-IV) |

|

| Garriga 2019 [69] | Longitudinal (18 weeks) Effect of CLZ on food craving and consumption in patients with SMI | 34 SMI patients SCZ: n = 27 Schizoaffective: n = 5 BD: n = 2 Age: 36.8 (range: 18–65) BMI: 27.3 Dosing: CLZ was initiated with a dose of 12.5–25 mg in the first day of treatment, followed by weekly upward adjustments of 25–50 mg (i.e., standard titration) Two subgroups: Normal weight (NW) = BMI < 25, n = 13 Overweight/obese (OWO) = BMI > 25, n = 21 | 38% F | Previous AP exposure (mean duration = 8.5 years): SGA = 28 (82.4%) FGA = 3 (8.8%) None = 3 (8.8%) | Food Craving (FCI, Spanish version) Cuestionario de Frecuencia de Consumo de Alimentos (CFCA) |

|

| Karagianis 2009 [70] | Randomized, double blind, double dummy study (16 weeks) Effect of OLA on BMI, efficacy scores, weight and subjective appetite in patients with SMI | 149 OLA-treated outpatients (115 completers) SCZ: n = 82 BD: n = 41 Schizoaffective: n = 15 Schizophreniform: n = 9 Other related disorder: n = 2 Age: 39 (range: 18–65) BMI: 28.1 Two treatment groups: Orally disintegrating OLA (ODO): n = 84 (MD: 13.87 mg/d) Standard OLA tablets (SOT): n = 65 (MD: 13.23 mg/d) | 46% F 52.3% Caucasian, 33.6% Hispanic, 10.1% Black, 2.0% Asian, 1.3% First-nation, 0.7% Other | Previous AP exposure: 5–20 mg/day SOT (duration 4–52 weeks) | Hunger/appetite scale (VAS) |

|

| Ryu 2013 [50] | Longitudinal (12 weeks) Effect of SGA treatment on eating behaviour in patients with SCZ | 45 SCZ patients treated with SGA monotherapy OLA: n = 13 RIS: n = 24 ARI: n = 8 Age: 32.1 (range: 18–50) | 50% F | Treated with current AP for 4–12 weeks (AP-free for 4 weeks prior to starting medication) | Binge eating/ED symptomatology (DSM-IV) Binary appetite/craving scale Food Craving (FCQ) DR-EBQ |

|

| Smith 2012 [71] | Randomized trial (5 months) Effect of OLA and RIS on appetite in patients with chronic SCZ | 46 SCZ inpatients OLA: n = 13 (MD: 25.2 mg/d) RIS: n = 17 (MD: 6.1 mg/d) Age: 41.2 (OLA), 42.5 (RIS) | 2% F | All patients had been treated with multiple antipsychotics in the past | Hunger/appetite scale (VAS from 0–100) Eating Behavior Assessment (EBA) |

|

| Sentissi 2009 [72] | Cross-sectional (medication type) Effect of SGAs on eating behaviours and motivation in patients with SCZ | 153 SCZ in- and outpatients SGA: n = 93 FGA: n = 27 Untreated: n = 33 Age: 33.1 (range: <50) BMI: 25.6 Among the untreated patients, 23 were AP-naïve, and 10 were AP-free for >3 months (mean duration: 7 months; range: 3–29 months) | 38.6% F | SGA monotherapy: CLZ = 20 (MD: 374 mg/d) OLA = 23 (MD: 12 mg/d) AMI = 14 (MD: 571.4 mg/d) RIS = 20 (MD: 3.7 mg/d) ARI = 16 (MD: 11.9 mg/d) FGA: mainly HAL (n = 16, 59% of sample) or phenothiazines; MD = 289 mg/d (CPZ equivalents) Mean treatment duration (months): 36.2 (range = 3–86) Illness duration: 9.6 years | TFEQ DEBQ |

|

| Abbas 2013 [73] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Food craving in OLA- or FGA-treated patients with SCZ vs. HCs | 40 SCZ in- and outpatients OLA: n = 20 FGA: n = 20 Age (both): 39.4 (range: 18–65) BMI: 29.5 (OLA), 27.3 (FGA) 20 HCs (un-matched) Age: 40.9 BMI: 25.8 | OLA: 45% F FGA: 55% F HC: 55% F | OLA (n = 20) or FGA (n = 20) for at least one month Flupentixol = 6 Zuclopenthixol acetate = 5 CPZ = 3 HAL = 2 Fluphenazine decanoate = 1 Pipotiazine palmitate = 1 Stelazine = 1 Trifluperazine = 1 Mean treatment duration (months): 15.1 (OLA), 19.7 (FGA) | Food Craving (FCI) |

|

| Blouin 2008 [74] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Adiposity and post-meal challenge eating behaviours in SGA-treated patients with SCZ vs. HCs | 18 SCZ outpatients Age: 30.5 (range: 18–65) BMI: 28.8 20 HCs (matched for age and physical activity) Age: 29.5 BMI: 25.0 | All Males | Previous AP exposure: FGA or SGA (mean duration = 35.3 months) Current SGA treatment: at least 3 months (mean duration = 24.6 months) OLA = 9 QUE = 3 CLZ = 2 RIS = 2 ZIP = 2 | TFEQ Hunger/Appetite Scale (150-mm VAS) Food preference test and spontaneous intake (food weighed) 12 h fast prior to standardized breakfast, followed by an ad libitum buffet-type meal ~3 h later |

|

| Folley 2010 [75] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Relative food preferences and hedonic judgements in SGA-treated patients with SCZ vs. HCs | 18 SCZ outpatients treated with SGAs (MD: 93.6 mg/d) Age: 40.5 (range: 21–58) 18 HCs (matched for education and intelligence scores) Age: 38.9 (range: 20–52) | SCZ: 33% F HC: 44% F | Illness duration: 16.4 years | Food preference and food ratings task (Extra scanner task, 5-point Likert scale); participants tested prior to eating lunch |

|

| Knolle-Veentjer 2008 [76] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Role of eating behaviour in body weight regulation in patients with SCZ vs. HCs | 29 SCZ patients Paranoid subtype: n = 27 Disorganized subtype: n = 2 Age: 34 (range: 21–56) BMI: 26.8 23 HCs (matched for age, sex, educational level) Age: 32 (range: 20–58) BMI: 23.9 | SCZ: 34.5% F HC: 26.1% F | QUE = 9 (MD: 600 mg/d) RIS = 8 (MD: 5.3 mg/d) OLA = 6 (MD: 15.83 mg/d) AMI = 4 (MD: 700 mg/d) ARI = 1 (MD: 20 mg/d) Flupentixol = 1 (MD: 10 mg/d) | FEV (German version of the TFEQ) Author-developed board game to assess delay of gratification using food reward Behavioral assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome (BADS) |

|

| Schanze 2008 [77] | Cross-sectional Comparing eating behaviours in patients with SCZ and MDD vs. HCs | 42 SCZ inpatients Age: 33.6 BMI: 27.28 83 MDD inpatients Age: 40.42 BMI: 26.01 46 HCs (un-matched) Age: 35.7 BMI: 23.51 | SCZ: 40.5% F MDD: 47% F HC: 47.8% F | SCZ (last 4 weeks): QUE = 6 RIS = 5 ZIP = 4 OLA = 2 CLZ = 1 SSRI = 1 None = 23 MDD (last 4 weeks): QUE = 1 RIS = 1 SSRI = 15 Mirtazapine = 10 None = 56 | TFEQ |

|

| Roerig 2005 [78] | Randomized, double blind, parallel (2 weeks) Effect of OLA and RIS vs. placebo on eating behaviours in HCs | 48 HCs, 18–60 years OLA: n = 16 (MD: 8.75 mg/d) RIS: n = 16 (MD: 2.875 mg/d) PLA: n = 16 Age: 33.6 (OLA), 36.2 (RIS), 32.7 (PBO) BMI: 23.6 (OLA), 25.0 (RIS), 24.1 (PBO) | OLA: 87.5% F RIS: 75% F PBO: 68.75% F | N/A | Hunger/appetite scale (100-mm VAS) Feeding laboratory (standardized breakfast, liquid lunch, ad libitum dinner where food was weighed) Resting energy expenditure (REE) |

|

| Teff 2015 [79] | Randomized trial (12 days; 9 days of SGA exposure) Effect of acute SGA exposure on hunger and food intake in HCs | 30 HCs OLA: n = 10 RIS: n =10 PBO: n = 10 Age: 26.1 (OLA), 25.9 (ARI), 29.9 (PBO) BMI: 22.1 (OLA), 22.4 (ARI), 21.8 (PBO) reported in [80] | 30% F | N/A | Hunger/appetite scale (9-point Likert) Food intake weighed (objective) Activity level (number of steps) |

|

| Study | Design/Aim | Sample (Size, Diagnosis), Mean Age (Years), Mean BMI | Sex (% F), Race/Ethnicity | Mean Illness Duration/Previous AP Exposure (n) | Assessments | Main Significant Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stip 2015 * [84] | Longitudinal (16 week) study, pre- post with OLA administration Examining the salience network in SCZ patients on OLA treatment | 15 SCZ patients not previously exposed to OLA switching to OLA Same cohort as 2012 study (authors did not specify switchers vs. AP-naïve, fasted) | NR | NR | fMRI (BOLD) during neutral vs. dynamic appetitive stimuli Hunger/appetite scale (VAS from 0–5) TFEQ |

|

| Lungu 2013 * [83] | Cross sectional (case-control) Neuronal correlates of appetite regulation in patients with SCZ vs. HC (3 h since last meal) | 25 SCZ (20 completers) AP (OLA excluded): n = 21 AP-naïve: n = 3 Age: 34.5 BMI: 26.62 11 HCs (10 included) Age: 35.2 BMI: 25.07 | 48% F SCZ: 24% F HC: 20% F | RIS = 12 QUE = 6 HAL = 2 CLZ = 1 Perphenazine = 1 No medication = 3 | fMRI (BOLD) during neutral vs. static appetitive stimuli Hunger/appetite scale (VAS from 0–5) TFEQ |

|

| Stip 2012 * [85] | Longitudinal intervention (16 weeks) vs. HCs Evaluating neural changes associated with appetite in SCZ patients pre, and post OLA treatment vs. HCs (3 h since last meal) | 24 SCZ patients not previously exposed to OLA (15 completers) Switch (no washout): n = 19 AP-naïve: n = 3 Age: 30.04 10 HCs Age: 33.9 Same cohort as Lungu 2013 | SCZ: 21% F; 91.66% Caucasians, 8.33% Caribbean HC: 20% F; 100% Caucasian | RIS = 12 QUE = 6 HAL = 2 CLZ = 1 Perphenazine = 1 No medication = 3 | fMRI (BOLD) during neutral vs. static appetitive stimuli Hunger/appetite scale (VAS from 0–5) TFEQ |

|

| Grimm 2012 [82] | Cross sectional (case-control) Striatal activation during appetitive cues (fasting state) | 23 fasted (6h) chronic SCZ in- and outpatients on stable AP medication (MD: 346 mg/d CPZ equivalents) Age: 30.3 23 fasted HCs (matched for age, gender, parental SES, handedness) Age: 28.9 | 74% F | No change in the medication dose >25% or a switch to a different medication was allowed in the last 4 weeks SGA: n = 22 RIS = 4 OLA = 3 CLZ = 4 AMI = 3 QUE = 3 ARI = 3 ZIP = 1 FGA: n = 1 Flupenthixol = 1 Illness duration: 4.1 years | fMRI (BOLD) during neutral vs. static appetitive stimuli Hunger/appetite scale (VAS) |

|

| Emsley 2015 [88] | Prospective (13 weeks of AP treatment vs. HC) Morphological changes in brain regions associated with food intake regulation, metabolic parameters (BMI, fasting glucose, lipids) (fasting not specified) | 22 AP-naïve FEP in- and outpatients randomized to receive RIS or flupenthixol decanoate long-acting injections (n not specified) SCZ: n = 13 Schizophreniform: n = 9 Age: 24.6 (range: 16–45) BMI: 22.1 23 untreated HCs (matched for age, sex, ethnicity, educational status) Age: 27 | 24% F FEP: 14% F; 64% mixed descent, 36% Black HC: 35% F; 70% mixed descent, 30% Black | No previous AP exposure; mean duration of untreated psychosis: 41 weeks Mean endpoint dose: 31.66 mg 2-weekly (RIS), 13.07 mg 2-weekly (flupenthixol) | Structural MRI changes in prespecified brain regions associated with hedonic and homeostatic body weight regulation |

|

| Borgan 2019 [86] | Cross-sectional (case-control) Neural responsivity to food cues in unmedicated first episode psychosis (fasting state used) | 29 fasted (>12 h), untreated FEP patients SCZ: n = 27 Schizoaffective: n = 2 Age: 26.1 (range: 18–65) BMI: 25.2 28 fasted HCs (matched for age) Age: 26.4 BMI: 24.7 | 17% F FEP: 14% F; 12 White, 9 Black African or Black Caribbean, 6 Asian, 2 Mixed HC: 21% F; 10 White, 3 Black African or Black Caribbean, 11 Asian, 4 Mixed | Patients were AP-naïve or free from all psychotropic medication for at least 6 weeks Prior use = 20 AP-naïve = 9 Duration of prior treatment: 4.74 months Illness duration: 21.5 months | fMRI (BOLD signal) during neutral vs. static food cue (low and high calorie) IPAQ Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education |

|

| Mathews 2012 [87] | Interventional (pre- post 1-week OLA administration) open-label prospective design Neural activity associated with anticipation and receipt of food rewards after 1 week of OLA (in fasting state) | 19 fasted (overnight) HCs Age: 27.5 (range = 18–50) BMI: 25.78 Dosing: 5 mg of OLA on the first night and 10 mg on the subsequent 6 nights | 47.4% F 73.7% White, 10.5% African American, 10.5% Hispanic, 5.3% Mixed | N/A | fMRI (BOLD) during appetitive visual stimuli, and in response to receipt of cued food or water control (chocolate milk, tomato juice) Consumption of “liquid breakfast” measured post scan Hunger/appetite scale (5-point Likert) TFEQ |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stogios, N.; Smith, E.; Asgariroozbehani, R.; Hamel, L.; Gdanski, A.; Selby, P.; Sockalingam, S.; Graff-Guerrero, A.; Taylor, V.H.; Agarwal, S.M.; et al. Exploring Patterns of Disturbed Eating in Psychosis: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123883

Stogios N, Smith E, Asgariroozbehani R, Hamel L, Gdanski A, Selby P, Sockalingam S, Graff-Guerrero A, Taylor VH, Agarwal SM, et al. Exploring Patterns of Disturbed Eating in Psychosis: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2020; 12(12):3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123883

Chicago/Turabian StyleStogios, Nicolette, Emily Smith, Roshanak Asgariroozbehani, Laurie Hamel, Alexander Gdanski, Peter Selby, Sanjeev Sockalingam, Ariel Graff-Guerrero, Valerie H. Taylor, Sri Mahavir Agarwal, and et al. 2020. "Exploring Patterns of Disturbed Eating in Psychosis: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 12, no. 12: 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123883

APA StyleStogios, N., Smith, E., Asgariroozbehani, R., Hamel, L., Gdanski, A., Selby, P., Sockalingam, S., Graff-Guerrero, A., Taylor, V. H., Agarwal, S. M., & Hahn, M. K. (2020). Exploring Patterns of Disturbed Eating in Psychosis: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 12(12), 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123883