Automatic and Controlled Processing: Implications for Eating Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

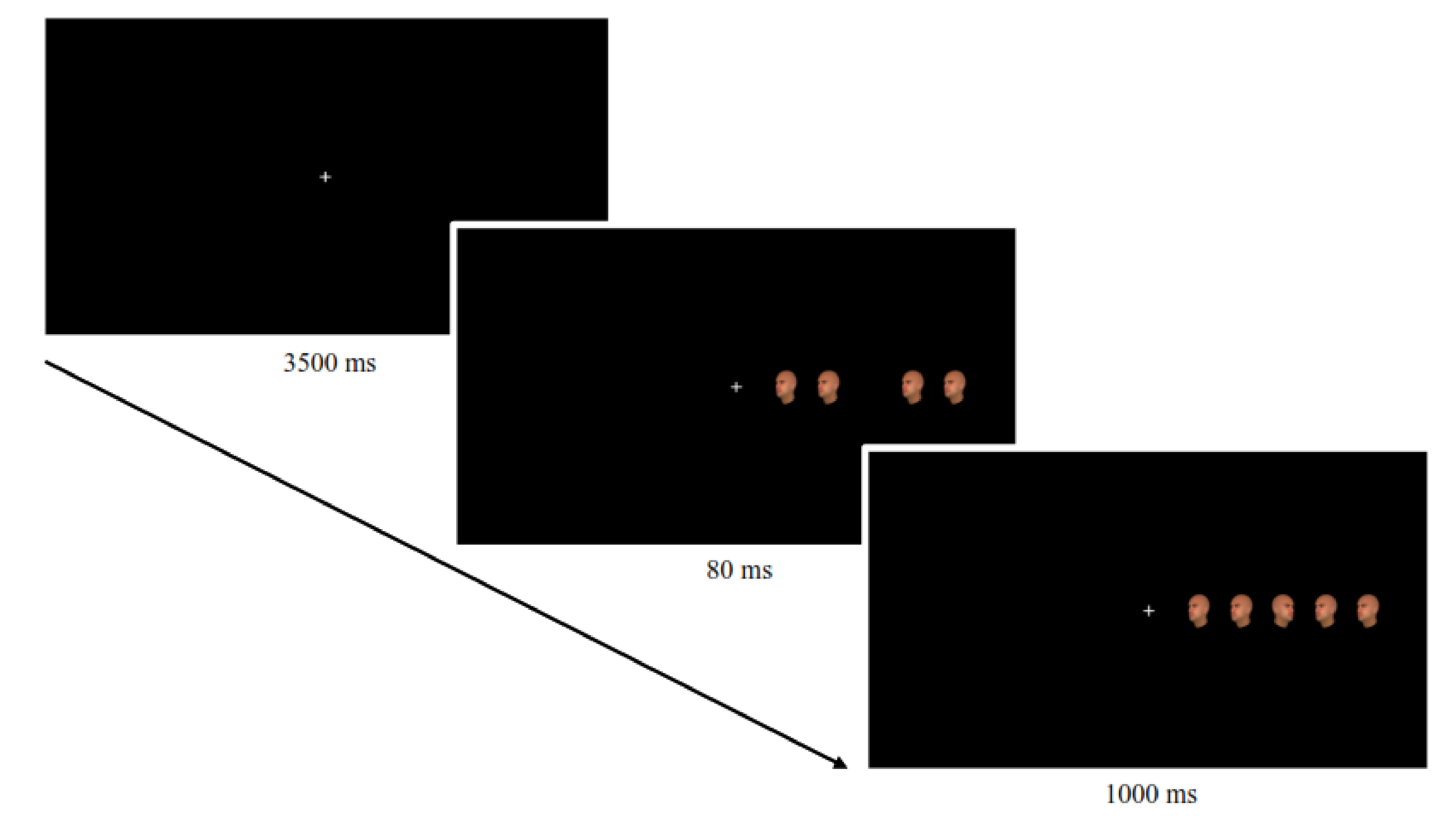

2.2.1. Conflict Control

2.2.2. Self-Control and Habitual Behavior

2.2.3. Eating Behavior

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Flanker Task Data Analysis

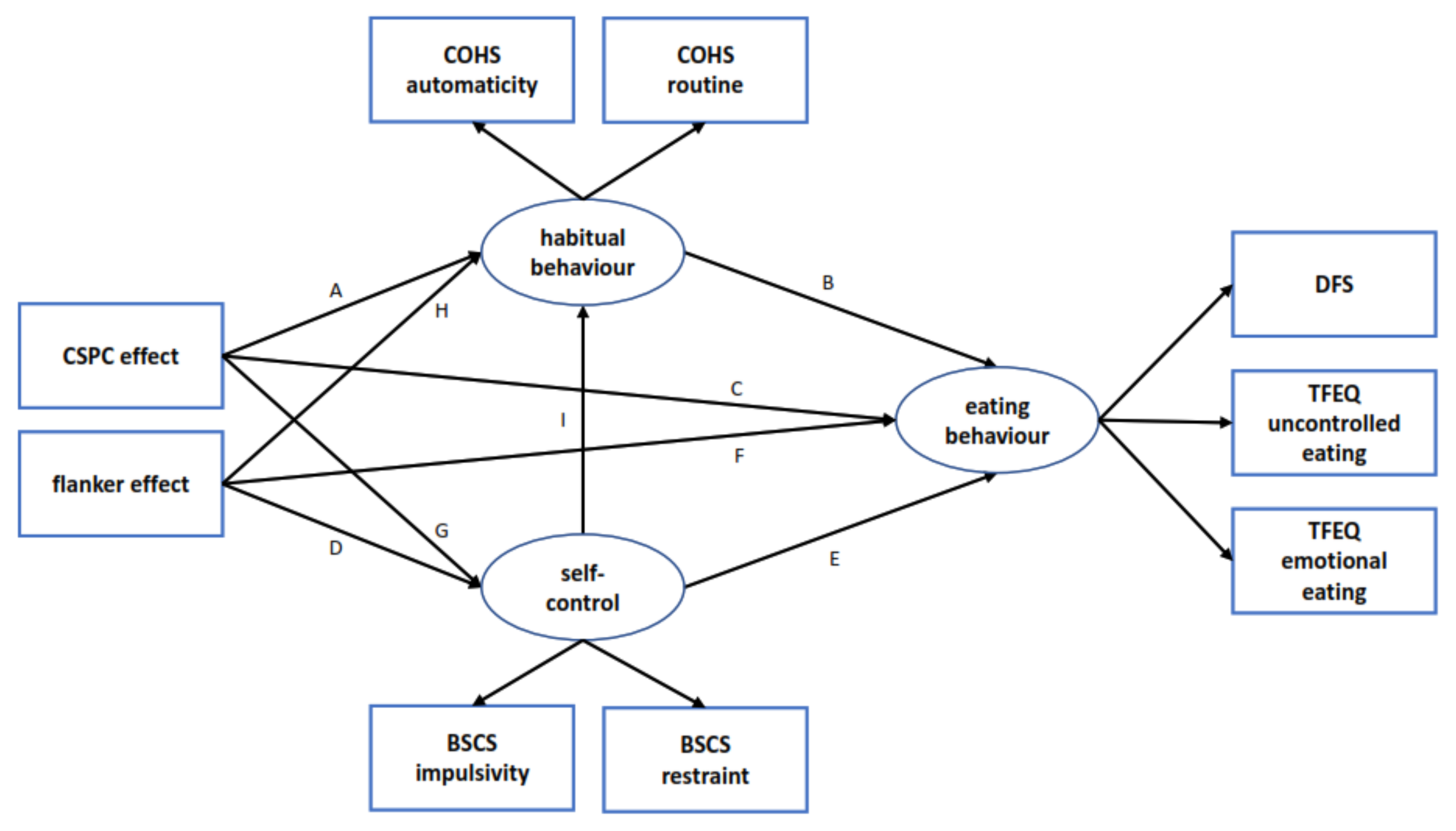

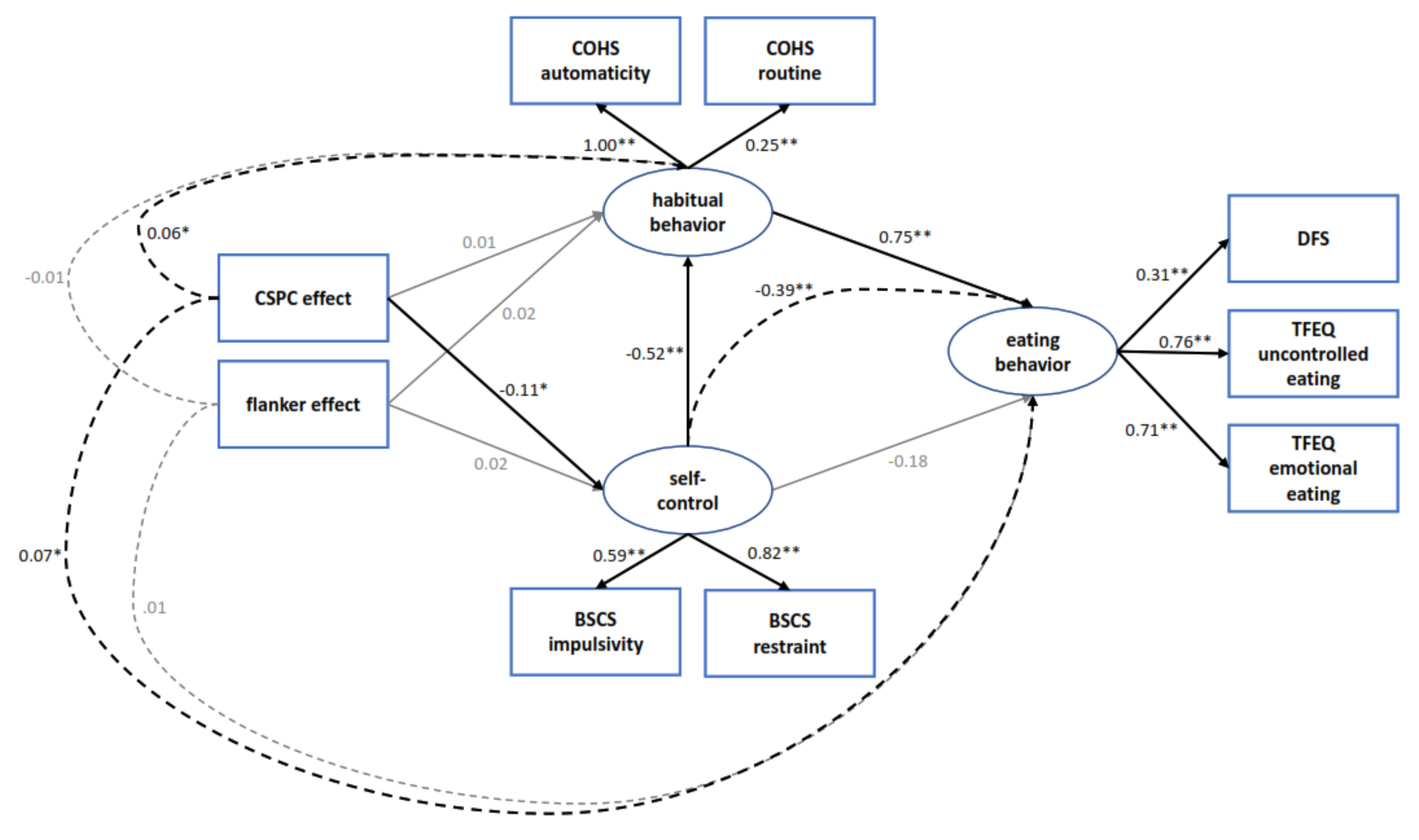

2.4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Sample, Self-Report Data, and Task Performance

3.2. Structural Equation Modeling

3.3. Eating Behavior and Real-Life Outcomes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, D.A.; Farley, T.A. Eating as an Automatic Behavior. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2008, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, E.P. Diversity in the determinants of food choice: A psychological perspective. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W.; Rauch, W.; Gawronski, B. And deplete us not into temptation: Automatic attitudes, dietary restraint, and self-regulatory resources as determinants of eating behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.L.; Johnston, M.; Campbell, N. Unintentional eating. What determines goal-incongruent chocolate consumption? Appetite 2010, 54, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliston, K.G.; Ferguson, S.G.; Schüz, B. Personal and situational predictors of everyday snacking: An application of temporal self-regulation theory. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Rünger, D. Psychology of Habit. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, G.J.; Kroeze, W.; Oenema, A.; Brug, J. Saturated fat consumption and the Theory of Planned Behaviour: Exploring additive and interactive effects of habit strength. Appetite 2008, 51, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, G.J.; Kremers, S.P.J.; De Vet, E.; De Nooijer, J.; Van Mechelen, W.; Brug, J. Does habit strength moderate the intention-behaviour relationship in the Theory of Planned Behaviour? The case of fruit consumption. Psychol. Heal. 2007, 22, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.Y.; Wood, W.; Monterosso, J. Healthy eating habits protect against temptations. Appetite 2015, 103, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J.A.; Chartrand, T.L. The unbearable automaticity of being. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B. Environmenal Factors that Increase the Food Intake and Consumption Volume of Unknowing Consumers. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004, 24, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators (Institution). Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D. Did the Food Environment Cause the Obesity Epidemic? Obesity 2018, 26, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van’t Riet, J.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Dagevos, H.; De Bruijn, G.J. The importance of habits in eating behaviour. An overview and recommendations for future research. Appetite 2011, 57, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigg, J.T. Annual Research Review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillebaart, M.; Schneider, I.K.; De Ridder, D.T.D. Effects of Trait Self-Control on Response Conflict About Healthy and Unhealthy Food. J. Pers. 2016, 84, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgii, C.; Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M.; Richard, A.; Van Dyck, Z.; Blechert, J. The dynamics of self-control: Within-participant modeling of binary food choices and underlying decision processes as a function of restrained eating. Psychol. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, W.K.; Moody, L.N.; Koffarnus, M.; Thomas, J.G.; Wing, R. Self-control as measured by delay discounting is greater among successful weight losers than controls. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D. Cognitive Control. Core Constructs and Current Considerations. In The Wiley Handbook of Cognitive Control; Egner, T., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, W.; Adriaanse, M.; Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. Dieting and the self-control of eating in everyday environments: An experience sampling study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allom, V.; Mullan, B. Individual differences in executive function predict distinct eating behaviours. Appetite 2014, 80, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, P.A. Executive control resources and frequency of fatty food consumption: Findings from an age-stratified community sample. Heal. Psychol. 2012, 31, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.E.; Mason, T.B.; Schaefer, L.M.; Juarascio, A.; Dvorak, R.; Weinbach, N.; Crosby, R.D.; Wonderlich, S.A. Examining intra-individual variability in food-related inhibitory control and negative affect as predictors of binge eating using ecological momentary assessment. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 120, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, D.T.D.; Lensvelt-Mulders, G.; Finkenauer, C.; Stok, F.M.; Baumeister, R.F. Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasinska, A.J.; Yasuda, M.; Burant, C.F.; Gregor, N.; Khatri, S.; Sweet, M.; Falk, E.B. Impulsivity and inhibitory control deficits are associated with unhealthy eating in young adults. Appetite 2012, 59, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, W.; Gschwendner, T.; Friese, M.; Wiers, R.W.; Schmitt, M. Working memory capacity and self-regulatory behavior: Toward an individual differences perspective on behavior determination by automatic versus controlled processes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 962–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.; Kemps, E.; Moffitt, R. Inhibitory self-control moderates the effect of changed implicit food evaluations on snack food consumption. Appetite 2015, 90, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Lee, M.; Higgs, S. Food-specific response inhibition, dietary restraint and snack intake in lean and overweight/obese adults: A moderated-mediation model. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederkoorn, C.; Houben, K.; Hofmann, W.; Roefs, A.; Jansen, A. Control Yourself or Just Eat What You Like? Weight Gain Over a Year is Predicted by an Interactive Effect of Response Inhibition and Implicit Preference for Snack Foods. Heal. Psychol. 2010, 29, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffrin, R.M.; Schneider, W. Controlled and Automatic Human Information Processing: II. Perceptual Learning, Automatic Attending, and a General Theory. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 127–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awh, E.; Belopolsky, A.V.; Theeuwes, J. Top-down versus bottom-up attentional control: A failed theoretical dichotomy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugg, J.M.; Crump, M.J.C. In support of a distinction between voluntary and stimulus-driven control: A review of the literature on proportion congruent effects. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egner, T. Creatures of habit (and control): A multi-level learning perspective on the modulation of congruency effects. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crump, M.J.C.; Gong, Z.; Milliken, B. The context-specific proportion congruent Stroop effect: Location as a contextual cue. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2006, 13, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugg, J.M. Context, Conflict, and Control. In The Wiley Handbook of Cognitive Control; Egner, T., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, N.; Hutcherson, C.; Harris, A.; Rangel, A. Dietary self-control is related to the speed with which health and taste attributes are processed. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 26, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crump, M.J.C.; McDonnell, J.V.; Gureckis, T.M. Evaluating Amazon’s Mechanical Turk as a Tool for Experimental Behavioral Research. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A New Source Of Inexpensive, Yet High-Quality, Data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.clickworker.de (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Rolls, B.J.; Fedoroff, I.C.; Guthrie, J.F. Gender Differences in Eating Behavior and Body Weight Regulation. Heal. Psychol. 1991, 10, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000 – 2018 period: A systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, T.; Kroll, L.E.; Müters, S.; Stolzenberg, H. Messung des sozioökonomischen Status in der Studie “gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell” (GEDA). Bundesgesundheitsblatt—Gesundheitsforsch—Gesundheitsschutz 2013, 56, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.A.; Donkin, C.; Korb, F.M.; Egner, T. Model-based analysis of context-specific cognitive control. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.A.; Korb, F.M.; Egner, T. Priming of control: Implicit contextual cuing of top-down attentional set. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 8192–8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeke, C.M.; Finger, H.; Standvoss, K.; König, P. LabVanced: A Unified JavaScript Framework for Online Studies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Social Science IC2S2, Cologne, Germany, 10–13 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kolyasnikov, P.; Nikulchev, E.; Belov, V.; Silaeva, A.; Kosenkov, A.; Malykh, A.; Takhirova, Z.; Malykh, S. Analysis of software tools for longitudinal studies in psychology. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersche, K.D.; Lim, T.V.; Ward, L.H.E.; Robbins, T.W.; Stochl, J. Creature of Habit: A self-report measure of habitual routines and automatic tendencies in everyday life. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2017, 116, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, J.; Persson, L.-O.O.; Sjöström, L.; Sullivan, M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2000, 24, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, S.P.; Horstmann, A. Psychometric Evaluation of the German Version of the Dietary Fat and Free Sugar—Short Questionnaire. Obes. Facts 2019, 12, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, H.; Stevenson, R. Validity and test–retest reliability of a short dietary questionnaire to assess intake of saturated fat and free sugars: A preliminary study. Nutr. Sci. 2013, 26, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandierendonck, A. A comparison of methods to combine speed and accuracy measures of performance: A rejoinder on the binning procedure. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM SPSS AMOS for Windows 2012; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2012.

- Kong, F.; Zhang, Y.; You, Z.; Fan, C.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, Z. Body Dissatisfaction and Restrained Eating: Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2013, 41, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Cognitive Flexibility and Pro-environmental Behaviour: A Multimethod Approach. Eur. J. Pers. 2019, 33, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model Fit and Model Selection in Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Galla, B.M.; Duckworth, A.L. More than Resisting Temptation: Beneficial Habits Mediate the Relationship between Self-Control and Positive Life Outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 508–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, D.; Gillebaart, M. Lessons learned from trait self-control in well-being: Making the case for routines and initiation as important components of trait self-control. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, J.M.; Pascoe, A.; Wood, W.; Neal, D.T. Can’t control yourself? Monitor those bad habits. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleo, G.; Isenring, E.; Thomas, R.; Glasziou, P. Could habits hold the key to weight loss maintenance? A narrative review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, V.; Nouwen, A.; Van den Akker, O.; Higgs, S. The role of working memory sub-components in food choice and dieting success. Appetite 2018, 124, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohle, S.; Diel, K.; Hofmann, W. Executive functions and the self-regulation of eating behavior: A review. Appetite 2018, 124, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Kern, M.L. A meta-analysis of the convergent validity of self-control measures. J. Res. Pers. 2011, 45, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nȩcka, E.; Gruszka, A.; Orzechowski, J.; Nowak, M.; Wójcik, N. The (In)significance of Executive Functions for the Trait of Self-Control: A Psychometric Study. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkavi, Z.A.; Eisenberg, I.W.; Bissett, P.G.; Mazza, G.L.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Marsch, L.A.; Poldrack, R.A. Large-scale analysis of test–retest reliabilities of self-regulation measures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5472–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.R.; Lemercier, C. Context-Specific Proportion Congruent Effects: Compound-Cue Contingency Learning in Disguise. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2019, 72, 119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braem, S.; Bugg, J.M.; Schmidt, J.R.; Crump, M.J.C.; Weissman, D.H.; Notebaert, W.; Egner, T. Measuring Adaptive Control in Conflict Tasks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbruggen, F.; Logan, G.D. Automaticity of cognitive control: Goal priming in response-inhibition paradigms. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2009, 35, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.25 | 7.05 | 18–45 |

| BMI | 24.48 | 6.30 | 14.9–67.2 |

| BSCS: | |||

| impulsivity | 12.05 | 2.72 | 4–20 |

| restraint | 11.00 | 3.03 | 4–20 |

| COHS: | |||

| routine | 54.00 | 10.06 | 21–81 |

| automaticity | 31.03 | 8.52 | 11–55 |

| TFEQ-R18: | |||

| uncontrolled eating | 19.76 | 5.84 | 9–36 |

| emotional eating | 6.48 | 2.75 | 3–12 |

| DFS | 54.67 | 10.52 | 29–100 |

| High Conflict Condition | Low Conflict Condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congruent Trials | Incongruent Trials | Congruent Trials | Incongruent Trials | |

| M ± SD (LISAS) | 772.46 ± 132.03 | 892.20 ± 132.30 | 764.03 ± 126.98 | 920.51 ± 148.15 |

| Flanker effect | 119.74 ± 98.20 | 156.47 ± 112.13 | ||

| t = –29.03 ** | t = –33.23 ** | |||

| CSPC effect | 36.73 ± 139.50 | |||

| t = –6.27 ** | ||||

| Baseline Model | Complex Model A | Complex Model B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| df | 24 | 21 | 19 |

| χ² | 178.33 | 53.24 | 52.84 |

| χ²/df | 7.43 | 2.54 | 2.78 |

| CFI | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| RMSEA | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| AIC | 238.33 | 119.24 | 122.84 |

| Success of Weight-Loss Diets: | BMI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Sometimes | ||

| TFEQ-R18: | |||

| uncontrolled eating | –0.07 * | 0.01 | –0.05 |

| emotional eating | –0.07 | 0.02 | 0.76 ** |

| DFS | –0.04 * | –0.03 * | 0.02 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fürtjes, S.; King, J.A.; Goeke, C.; Seidel, M.; Goschke, T.; Horstmann, A.; Ehrlich, S. Automatic and Controlled Processing: Implications for Eating Behavior. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041097

Fürtjes S, King JA, Goeke C, Seidel M, Goschke T, Horstmann A, Ehrlich S. Automatic and Controlled Processing: Implications for Eating Behavior. Nutrients. 2020; 12(4):1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041097

Chicago/Turabian StyleFürtjes, Sophia, Joseph A. King, Caspar Goeke, Maria Seidel, Thomas Goschke, Annette Horstmann, and Stefan Ehrlich. 2020. "Automatic and Controlled Processing: Implications for Eating Behavior" Nutrients 12, no. 4: 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041097

APA StyleFürtjes, S., King, J. A., Goeke, C., Seidel, M., Goschke, T., Horstmann, A., & Ehrlich, S. (2020). Automatic and Controlled Processing: Implications for Eating Behavior. Nutrients, 12(4), 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041097