Dietary Acrylamide Intake and the Risk of Liver Cancer: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

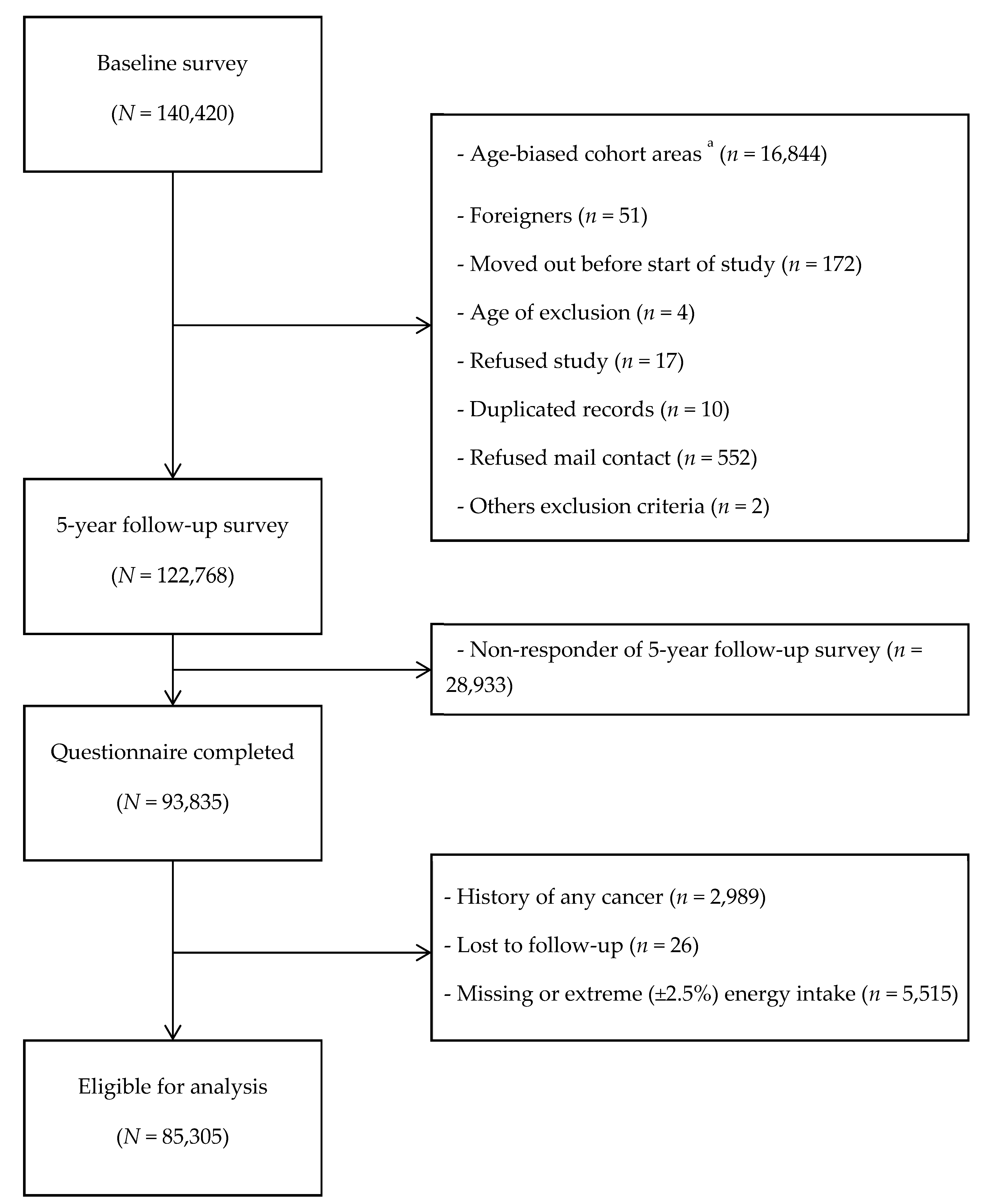

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Acrylamide Intake Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, biochemistry, and safety of acrylamide. A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 4504–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierisch, J.M.; Coeytaux, R.R.; Urrutia, R.P.; Havrilesky, L.J.; Moorman, P.G.; Lowery, W.J.; Dinan, M.; McBroom, A.J.; Hasselblad, V.; Sanders, G.D.; et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2013, 22, 1931–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hogervorst, J.G.; Baars, B.-J.; Schouten, L.J.; Konings, E.J.; Goldbohm, R.A.; van den Brandt, P.A. The carcinogenicity of dietary acrylamide intake: A comparative discussion of epidemiological and experimental animal research. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010, 40, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Some Industrial Chemicals; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans volume 60; IARC Publication: Lyon, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tareke, E.; Rydberg, P.; Karlsson, P.; Eriksson, S.; Törnqvist, M. Analysis of acrylamide, a carcinogen formed in heated foodstuffs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4998–5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottram, D.S.; Wedzicha, B.L.; Dodson, A.T. Food chemistry: Acrylamide is formed in the Maillard reaction. Nature 2002, 419, 448–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riboldi, B.P.; Vinhas, Á.M.; Moreira, J.D. Risks of dietary acrylamide exposure: A systematic review. Food Chem. 2014, 157, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, S.C.; Fennell, T.R.; Moore, T.A.; Chanas, B.; Gonzalez, F.; Ghanayem, B.I. Role of cytochrome P450 2E1 in the metabolism of acrylamide and acrylonitrile in mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999, 12, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanayem, B.I.; McDaniel, L.P.; Churchwell, M.I.; Twaddle, N.C.; Snyder, R.; Fennell, T.R.; Doerge, D.R. Role of CYP2E1 in the epoxidation of acrylamide to glycidamide and formation of DNA and hemoglobin adducts. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 88, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doroshyenko, O.; Fuhr, U.; Kunz, D.; Frank, D.; Kinzig, M.; Jetter, A.; Reith, Y.; Lazar, A.; Taubert, D.; Kirchheiner, J.; et al. In vivo role of cytochrome P450 2E1 and glutathione-S-transferase activity for acrylamide toxicokinetics in humans. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2009, 18, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogovski, P.; Bogovski, S. Special report animal species in which n-nitroso compounds induce cancer. Int. J. Cancer 1981, 27, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Janowsky, I.; Schmezer, P.; Hermann, R.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Zeller, W.; Pool, B. Effect of long-term inhalation of N-nitroso-dimethyl amine (NDMA) and SO2/NOx in rats. Exp. Pathol. 1989, 37, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugane, S.; Sawada, N. The JPHC study: Design and some findings on the typical Japanese diet. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 44, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsugane, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Sasaki, S. Validity of the self-administered food frequency questionnaire used in the 5-year follow-up survey of the JPHC Study Cohort I: Comparison with dietary records for main nutrients. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kotemori, A.; Ishihara, J.; Zha, L.; Liu, R.; Sawada, N.; Iwasaki, M.; Sobue, T.; Tsugane, S. Dietary acrylamide intake and risk of breast cancer: The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Sobue, T.; Kitamura, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Ishihara, J.; Kotemori, A.; Zha, L.; Ikeda, S.; Sawada, N.; Iwasaki, M. Dietary Acrylamide Intake and Risk of Esophageal, Gastric, and Colorectal Cancer: The Japan Public Health Center–Based Prospective Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2019, 28, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Ishihara, J.; Tsugane, S. Self-administered food frequency questionnaire used in the 5-year follow-up survey of the JPHC Study: Questionnaire structure, computation algorithms, and area-based mean intake. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishihara, J.; Inoue, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Tanaka, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Iso, H.; Tsugane, S. Impact of the revision of a nutrient database on the validity of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). J. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsugane, S.; Sasaki, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Tsubono, Y.; Akabane, M. Validity and reproducibility of the self-administered food frequency questionnaire in the JPHC Study Cohort I: Study design, conduct and participant profiles. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishihara, J.; Sobue, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Yoshimi, I.; Sasaki, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Takahashi, T.; Iitoi, Y.; Akabane, M.; Tsugane, S.; et al. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire in the JPHC Study Cohort II: Study design, participant profile and results in comparison with Cohort I. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, Y. Standard tables of food composition in Japan. In Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2008; pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Food Safety Commission of Japen. Study on Estimate of Acrylamide Intake from Food; Food Safety Commission of Japen: Tokyo, Japen, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Risk Profile Sheet Relating to the Food Safety for Acrylamide; Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: Tokyo, Japen, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health Sciences. Acrylamide Analysis in Food. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2002/11/tp1101-1a.html (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Mizukami, Y.; Kohata, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hayashi, N.; Sawai, Y.; Chuda, Y.; Ono, H.; Yada, H.; Yoshida, M. Analysis of acrylamide in green tea by gas chromatography−mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7370–7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuki, S.; Nemoto, S.; Sasaki, K.; Maitani, T. Production of acrylamide in agricultural products by cooking. Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. J. Food Hyg. Soc. Jpn. 2004, 45, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Food Safety Commission of Japen. Information Clearing Sheet for Acrylamide. Available online: https://www.fsc.go.jp/fsciis/attachedFile/download?retrievalId=kai20111222sfc&fileId=520 (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- FAO/WHO. Health Implications of Acrylamide in Food; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kotemori, A.; Ishihara, J.; Nakadate, M.; Sawada, N.; Iwasaki, M.; Sobue, T.; Tsugane, S. Validity of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire for the estimation of acrylamide intake in the Japanese population: The JPHC FFQ Validation Study. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inoue, M.; Yoshimi, I.; Sobue, T.; Tsugane, S. Influence of coffee drinking on subsequent risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective study in Japan. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schettgen, T.; Rossbach, B.; Kütting, B.; Letzel, S.; Drexler, H.; Angerer, J. Determination of haemoglobin adducts of acrylamide and glycidamide in smoking and non-smoking persons of the general population. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2004, 207, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, F.; Bosetti, C.; Tavani, A.; Bagnardi, V.; Gallus, S.; Negri, E.; Franceschi, S.; La Vecchia, C. Coffee drinking and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis. Hepatology 2007, 46, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Coffee consumption and risk of liver cancer: A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.-X.; Chang, B.; Li, X.-H.; Jiang, M. Consumption of coffee associated with reduced risk of liver cancer: A meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimazu, T.; Tsubono, Y.; Kuriyama, S.; Ohmori, K.; Koizumi, Y.; Nishino, Y.; Shibuya, D.; Tsuji, I. Coffee consumption and the risk of primary liver cancer: Pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 116, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, N.A.; Zhao-Chong, Z.; Guan, J.; Thacker, J.; Iliakis, G. Homologous recombination as a potential target for caffeine radiosensitization in mammalian cells: Reduced caffeine radiosensitization in XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants. Oncogene 2000, 19, 5788–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joerges, C.; Kuntze, I.; Herzinge, T. Induction of a caffeine-sensitive S-phase cell cycle checkpoint by psoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation. Oncogene 2003, 22, 6119–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saiki, S.; Sasazawa, Y.; Imamichi, Y.; Kawajiri, S.; Fujimaki, T.; Tanida, I.; Kobayashi, H.; Sato, F.; Sato, S.; Ishikawa, K.-I.; et al. Caffeine induces apoptosis by enhancement of autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K inhibition. Autophagy 2011, 7, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Azam, S.; Hadi, N.; Khan, N.U.; Hadi, S.M. Antioxidant and prooxidant properties of caffeine, theobromine and xanthine. Med Sci. Monit. 2003, 9, BR325–BR330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cavin, C.; Holzhaeuser, D.; Scharf, G.; Constable, A.; Huber, W.; Schilter, B. Cafestol and kahweol, two coffee specific diterpenes with anticarcinogenic activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 40, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, B.; Hofer, E.; Cavin, C.; Lhoste, E.; Uhl, M.; Glatt, H.; Meinl, W.; Knasmüller, S. Coffee diterpenes prevent the genotoxic effects of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo [4, 5-b] pyridine (PhIP) and N-nitrosodimethylamine in a human derived liver cell line (HepG2). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005, 43, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavin, C.; Holzhäuser, D.; Constable, A.; Huggett, A.C.; Schilter, B. The coffee-specific diterpenes cafestol and kahweol protect against aflatoxin B1-induced genotoxicity through a dual mechanism. Carcinogenesis 1998, 19, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogervorst, J.G.F. Dietary Acrylamide Intake and Human Cancer Risk; Maastricht University: Maastricht, The Netherland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, S.C.; Åkesson, A.; Bergkvist, L.; Wolk, A. Dietary acrylamide intake and risk of colorectal cancer in a prospective cohort of men. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzkin, A.; Kipnis, V.; Carroll, R.J.; Midthune, D.; Subar, A.F.; Bingham, S.; Schoeller, D.A.; Troiano, R.P.; Freedman, L.S. A comparison of a food frequency questionnaire with a 24-hour recall for use in an epidemiological cohort study: Results from the biomarker-based Observing Protein and Energy Nutrition (OPEN) study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 32, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | Tertile of Energy-Adjusted Acrylamide Intake | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 | p-Value c | ||||||||||||

| Number of Participants | 28,435 | 28,435 | 28,435 | ||||||||||||

| Men, % | 57.7 | 44.6 | 38.4 | ||||||||||||

| Dietary variables | |||||||||||||||

| Acrylamide intake | |||||||||||||||

| Range, μg/d | 0.04 | − | 4.81 | 4.82 | − | 7.63 | 7.64 | − | 67.11 | ||||||

| Mean and SD, a μg /d | 3.4 | ± | 1.0 | 6.1 | ± | 0.8 | 11.1 | ± | 3.5 | <0.001 | |||||

| Mean and SD, a μg·kg body weight−1·d−1 | 0.06 | ± | 0.05 | 0.11 | ± | 0.09 | 0.21 | ± | 0.23 | <0.001 | |||||

| Coffee, a g/d | 42.0 | ± | 57.8 | 107.1 | ± | 105.4 | 276.5 | ± | 283.8 | <0.001 | |||||

| Green tea, a g/d | 313.9 | ± | 337.9 | 510.7 | ± | 423.1 | 764.4 | ± | 680.8 | <0.001 | |||||

| Alcohol intake, a g/d | 155.1 | ± | 241.7 | 92.2 | ± | 179.2 | 58.5 | ± | 134.2 | <0.001 | |||||

| Biscuits, a g/d | 0.8 | ± | 1.2 | 2.0 | ± | 2.5 | 5.0 | ± | 7.9 | <0.001 | |||||

| Potato, a g/d | 10.2 | ± | 9.6 | 17.8 | ± | 14.8 | 21.5 | ± | 24.0 | <0.001 | |||||

| Vegetables, a g/d | 180.4 | ± | 119.8 | 220.9 | ± | 128.4 | 231.1 | ± | 143.3 | <0.001 | |||||

| Fruit, a g/d | 178.9 | ± | 161.4 | 219.8 | ± | 163.0 | 221.1 | ± | 168.5 | <0.001 | |||||

| Meat, a g/d | 58.1 | ± | 43.5 | 57.1 | ± | 36.6 | 56.2 | ± | 35.6 | <0.001 | |||||

| Fish, a g/d | 85.9 | ± | 56.1 | 88.4 | ± | 48.9 | 83.7 | ± | 47.9 | <0.001 | |||||

| Total energy intake, a kcal/d | 1997.1 | ± | 641.5 | 2019.3 | ± | 610.4 | 1971.3 | ± | 610.1 | <0.001 | |||||

| Nondietary variables | |||||||||||||||

| Age at 5-year follow-up study, a y | 57.8 | ± | 7.6 | 57.1 | ± | 7.9 | 55.9 | ± | 8.0 | <0.001 | |||||

| Body mass index, a b kg/m2 | 23.7 | ± | 3.1 | 23.6 | ± | 3.0 | 23.4 | ± | 3.0 | <0.001 | |||||

| Smoking status, % | |||||||||||||||

| Never | 57.9 | 64.8 | 64.2 | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| Former | 10.6 | 8.3 | 6.8 | ||||||||||||

| Current | 25.1 | 21.1 | 23.3 | ||||||||||||

| Missing | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.7 | ||||||||||||

| Number of cigarettes/d, a b only for current | 20.5 | ± | 14.3 | 21.2 | ± | 11.9 | 22.7 | ± | 11.4 | <0.001 | |||||

| Physical activity (METs) a | 33.2 | ± | 6.4 | 33.2 | ± | 6.2 | 33.1 | ± | 6.1 | <0.001 | |||||

| Diabetes, % yes | 8.3 | 6.6 | 5.4 | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| Hepatitis, % yes | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.7 | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| Quartile of Energy-Adjusted Acrylamide Intake | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μg/d | Tertile 1 (Lowest) | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 (Highest) | ||||||

| HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | p for Trend | |

| Number of subjects | 85,305 | 28,435 | 28,435 | 28,435 | |||||

| Person-years | 1,267,791 | 417,202 | 425,177 | 425,412 | |||||

| Number of liver cancers | 744 | 311 | 248 | 185 | |||||

| Age- and area-adjusted model a | 0.96 | (0.94–0.98) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.88 | (0.74–1.04) | 0.73 | (0.60–0.88) | <0.01 |

| Multivariable model 1 b | 0.96 | (0.94–0.99) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.90 | (0.76–1.06) | 0.79 | (0.65–0.95) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable model 1 (excluding cases < 3 years) | 0.97 | (0.94–0.99) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.91 | (0.76–1.10) | 0.82 | (0.66–1.01) | 0.06 |

| Multivariable model 2 c | 0.99 | (0.96–1.01) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (0.84–1.20) | 1.08 | (0.87–1.34) | 0.51 |

| Multivariable model 2 (excluding cases < 3 years) | 0.99 | (0.96–1.01) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.99 | (0.81–1.21) | 1.08 | (0.85–1.37) | 0.58 |

| Multivariable model 3 d (excluding cases with history of hepatitis) | 0.99 | (0.96–1.02) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.95 | (0.76–1.18) | 1.12 | (0.87–1.45) | 0.47 |

| By smoking status | |||||||||

| Never smoker | |||||||||

| Number of subjects | 53,137 | 16,460 | 18,429 | 18,248 | |||||

| Person-years | 817,862 | 252,425 | 283,953 | 281,484 | |||||

| Number of liver cancers | 335 | 131 | 109 | 95 | |||||

| Multivariable model 1 | 0.98 | (0.94–1.01) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.86 | (0.66–1.11) | 0.93 | (0.70–1.22) | 0.54 |

| Multivariable model 2 | 0.99 | (0.95–1.02) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.95 | (0.72–1.25) | 1.15 | (0.85–1.56) | 0.42 |

| Ever smoker e | |||||||||

| Number of subjects | 27,083 | 10,150 | 8365 | 8568 | |||||

| Person-years | 382,550 | 141,189 | 119,153 | 122,209 | |||||

| Number of liver cancers | 352 | 147 | 128 | 77 | |||||

| Multivariable model 1 | 0.95 | (0.92–0.99) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.06 | (0.83–1.35) | 0.71 | (0.53–0.94) | 0.03 |

| Multivariable model 2 | 0.99 | (0.95–1.02) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.17 | (0.90–1.51) | 1.07 | (0.77–1.51) | 0.52 |

| By coffee consumption | |||||||||

| Nondrinker | |||||||||

| Number of subjects | 23,104 | 13,603 | 6048 | 3453 | |||||

| Acrylamide intake (mean ± SD, μg/d) | 3.0 | ±1.1 | 6.0 | ±0.8 | 10.8 | ±3.1 | |||

| Acrylamide intake (range, μg/d) | 0.0 | −4.8 | 4.8 | −7.6 | 7.6 | −67.1 | |||

| Person-years | 335,958 | 197,392 | 88,407 | 50,159 | |||||

| Number of liver cancers | 266 | 160 | 68 | 38 | |||||

| Multivariable model 1 | 1.01 | (0.96–1.06) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (0.74–1.34) | 1.12 | (0.77–1.62) | 0.63 |

| Drinker | |||||||||

| Number of subjects | 62,201 | 14,832 | 22,387 | 24,982 | |||||

| Acrylamide intake (mean ± SD, μg/d) | 3.7 | ±0.8 | 6.1 | ±0.8 | 11.1 | ±3.5 | |||

| Acrylamide intake (range, μg/d) | 0.4 | −4.8 | 4.8 | −7.6 | 7.6 | −62.8 | |||

| Person-years | 931,833 | 219,810 | 336,770 | 375,253 | |||||

| Number of liver cancers | 478 | 151 | 180 | 147 | |||||

| Multivariable model 1 | 0.96 | (0.93–0.98) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.86 | (0.69–1.07) | 0.74 | (0.58–0.94) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable model 2 | 0.98 | (0.95–1.01) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.97 | (0.77–1.22) | 1.05 | (0.80–1.38) | 0.73 |

| Quartile of Energy-Adjusted Acrylamide Intake | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μg/d | Tertile 1 (Lowest) | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 (Highest) | ||||||

| HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | p for Trend | |

| Men | |||||||||

| Number of subjects | 39,996 | 16,417 | 12,669 | 10,910 | |||||

| Person-years | 569,415 | 231,895 | 181,770 | 155,751 | |||||

| Number of liver cancers | 530 | 237 | 175 | 118 | |||||

| Age- and area-adjusted model a | 0.95 | (0.93–0.98) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.91 | (0.74–1.10) | 0.71 | (0.57–0.89) | <0.01 |

| Multivariable model 1 b | 0.96 | (0.93–0.99) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.94 | (0.77–1.14) | 0.78 | (0.62–0.98) | 0.04 |

| Multivariable model 2 c | 0.99 | (0.96–1.02) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.05 | (0.85–1.29) | 1.15 | (0.88–1.50) | 0.31 |

| Women | |||||||||

| Number of subjects | 45,309 | 12,018 | 15,766 | 17,525 | |||||

| Person-years | 698,376 | 185,307 | 243,407 | 269,662 | |||||

| Number of liver cancers | 214 | 74 | 73 | 67 | |||||

| Age- and area-adjusted model a | 0.97 | (0.93–1.00) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.81 | (0.59–1.13) | 0.78 | (0.56–1.10) | 0.16 |

| Multivariable model 1 b | 0.97 | (0.94–1.01) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.76 | (0.55–1.06) | 0.77 | (0.54–1.08) | 0.14 |

| Multivariable model 2 c | 0.98 | (0.95–1.02) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 0.83 | (0.59–1.17) | 0.92 | (0.63–1.32) | 0.65 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zha, L.; Sobue, T.; Kitamura, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Ishihara, J.; Kotemori, A.; Liu, R.; Ikeda, S.; Sawada, N.; Iwasaki, M.; et al. Dietary Acrylamide Intake and the Risk of Liver Cancer: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092503

Zha L, Sobue T, Kitamura T, Kitamura Y, Ishihara J, Kotemori A, Liu R, Ikeda S, Sawada N, Iwasaki M, et al. Dietary Acrylamide Intake and the Risk of Liver Cancer: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. Nutrients. 2020; 12(9):2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092503

Chicago/Turabian StyleZha, Ling, Tomotaka Sobue, Tetsuhisa Kitamura, Yuri Kitamura, Junko Ishihara, Ayaka Kotemori, Rong Liu, Sayaka Ikeda, Norie Sawada, Motoki Iwasaki, and et al. 2020. "Dietary Acrylamide Intake and the Risk of Liver Cancer: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study" Nutrients 12, no. 9: 2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092503

APA StyleZha, L., Sobue, T., Kitamura, T., Kitamura, Y., Ishihara, J., Kotemori, A., Liu, R., Ikeda, S., Sawada, N., Iwasaki, M., Tsugane, S., & JPHC Study Group, f. t. (2020). Dietary Acrylamide Intake and the Risk of Liver Cancer: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. Nutrients, 12(9), 2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092503