Abstract

Dehydration is common in the elderly, especially when hospitalised. This study investigated the impact of interventions to improve hydration in acutely unwell or institutionalised older adults for hydration and hydration linked events (constipation, falls, urinary tract infections) as well as patient satisfaction. Four databases were searched from inception to 13 May 2020 for studies of interventions to improve hydration. Nineteen studies (978 participants) were included and two studies (165 participants) were meta-analysed. Behavioural interventions were associated with a significant improvement in hydration. Environmental, multifaceted and nutritional interventions had mixed success. Meta-analysis indicated that groups receiving interventions to improve hydration consumed 300.93 mL more fluid per day than those in the usual care groups (95% CI: 289.27 mL, 312.59 mL; I2 = 0%, p < 0.00001). Overall, there is limited evidence describing interventions to improve hydration in acutely unwell or institutionalised older adults. Behavioural interventions appear promising. High-quality studies using validated rather than subjective methods of assessing hydration are needed to determine effective interventions.

Keywords:

dehydration; fluid; beverages; geriatric; inpatient; institutionalized; elderly; systematic review; meta-analysis 1. Introduction

Dehydration is the most common fluid and electrolyte complication amongst the elderly [1]. It is highly prevalent in hospitalised and institutionalised settings [2]. Nursing homes have also identified inadequate fluid intake amongst 50–90% of residents [2]. Similarly, in an Australian geriatric rehabilitation ward, almost one in five patients were found to be dehydrated [3]. Patients with dysphagia are particularly susceptible to the development of dehydration [4,5]. This is often attributed to poor compliance and low satisfaction rates with thickened fluids reported by patients with dysphagia [5] A study in an acute hospital setting demonstrated that patients on thickened fluids consumed only 23.4% of their fluid requirements on average [6]. Furthermore, it has been shown that up to 55% of individuals with dysphagia are at risk of dehydration, which can lead to decreased quality of life and increased healthcare costs [7].

Dehydration increases risk of morbidity and mortality [8]. This is because lower hydration levels are associated with incidences of acute confusion, constipation, urinary tract infections (UTIs), exhaustion, falls and delayed wound healing [9,10]. Dehydration has also been correlated to longer hospital stays with the annual cost estimate for a primary diagnosis of dehydration being >$1.14 billion 1999 USD [11,12]. Older adults are at increased risk of dehydration due to age related physiological changes, such as decreased thirst sensation and impaired renal function [11]. This risk is often exacerbated in those with mental illness or stroke [11].

The definition of dehydration has been debated as it can be often generalised to describe any fluid imbalance in any fluid compartment [1]. A proposed definition is that dehydration is a complex condition resulting in a reduction of total body water [9]. More expansive definitions can be found when accounting for varying effects in the extracellular compartment (isotonic, hypertonic, hypotonic) [13]. There is also a lack of consensus about which measure should be considered the gold standard for determining hydration status [14,15]. A recent Cochrane systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus statement determined serum osmolality as the gold standard [13,16]. When this method is not readily available it should be substituted with a specific formula (the Khajuria–Krahn formula [17]) to calculate plasma osmolarity [13]. Other techniques for determining dehydration provide singular measures of a complex matrix as opposed to capturing the whole fluid regulation process and some measures may not be appropriate in the elderly population due to declining renal function [15,18].

Despite the high prevalence of dehydration, there is limited consensus on the success or efficacy of interventions to improve hydration status. Previous systematic reviews on the topic are more than 15 years out of date [19] or were confined to the long-term care setting [20]. The purpose of this systematic review was therefore (i) to evaluate the impact of interventions to improve hydration in acutely unwell or institutionalised older adults (ii) and to describe the association between interventions to improve hydration and hydration linked events (constipation, falls, UTIs) and patient satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

Reporting of this systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol for this systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 13 August 2020 (registration number: CRD42020197422).

2.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted to identify studies that implemented an intervention to improve hydration or fluid intake in acutely unwell or institutionalised older adults. The search strategy was guided by advice from a librarian and a similar systematic review conducted previously [20]. A preliminary search of the literature was completed to help refine key search terms. The final search terms for use in CINAHL database are shown in Supplementary Material Table S1 and were modified to suit each database. Key search terms involved use of MeSH terms for the population including “Aged” or “Aged or geriatrics”; intervention terms relating to “fluid therapy”, “drink”, “fluid”, and outcome search terms relating to “dehydration”, “hypovolemia” or “hypernatremia”. These search terms were entered into four databases (CINAHL, Medline, Scopus and Web of Science). Hand searching of the reference lists of previous relevant systematic reviews was also conducted to identify additional articles for inclusion. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Articles for inclusion in this review included acutely unwell patients (≥65 years) in hospital settings or residents (≥65 years) in an institution such as a nursing home or long-term rehabilitation setting, and papers written in the English language. Intervention studies were eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if they involved older adults living in the community, palliative patients, people <65 years, strategies involving parenteral nutrition, enteral nutrition or intravenous fluids or the outcome did not relate to hydration or fluid intake. Case reports, review articles, abstracts, conference proceedings and observational studies were excluded from this review. Articles that included secondary outcomes on hydration linked events (HLEs), such as constipation, falls, urinary tract infections were included. Patient satisfaction with the intervention were noted where a primary outcome was described.

2.3. Data Extraction

The results from the database searches were downloaded into Endnote X9 (Thompson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). Duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two people (CB, KL) to determine eligibility into the systematic review. Information extracted from the articles was conducted by two people (CB, KL) and included: author, country, study design, setting, participant characteristics, intervention, duration, outcome(s) and method of assessment. Interventions were grouped into four categories: behavioural, environmental, multifaceted and nutritional.

2.4. Meta-Analysis

Studies were eligible for meta-analysis if more than two randomised controlled trials on the same outcome were available and (i) reported useable data in a compatible metric (ii) had a matched control group assessed at the same time. RevMan5 (Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4.1, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) was used to conduct analyses. Mean difference was used and the standard deviation of the difference was calculated using the formula SD = √SDbaseline2 + SDpost2 − (2 × r × SDbaseline × SDpost), where r is assumed to be 0.5. To account for heterogeneity between the studies, a random effects model was used. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Variance between studies was evaluated and reported as I2, which indicates the degree of variance resulting from between study heterogeneity, where a high score closer to 100 indicates high heterogeneity between studies.

2.5. Assessment of Study Quality

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Criteria Checklist for primary research was used to evaluate study quality [14] This tool provides an overall rating of positive, negative or neutral. Two independent reviewers assessed the risk of bias. A positive rating indicates the article has clearly addressed issues of bias, generalisability, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data collection and analysis. A negative rating indicates these issues have not be sufficiently addressed. A neutral rating implies some areas may be unclear and therefore is not classified as a strong or weak study.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

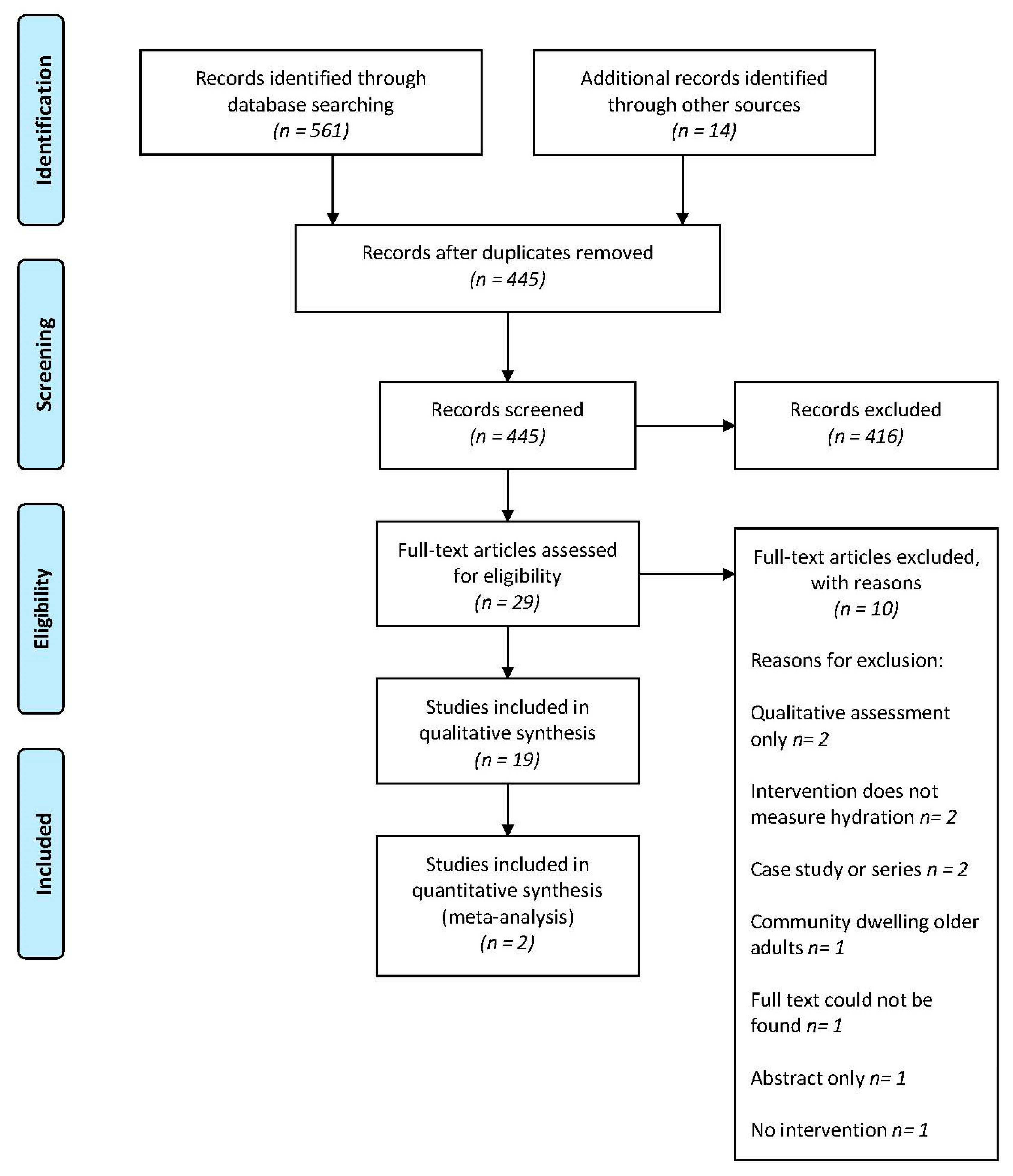

A total of 575 articles were identified in the database searches as well as through hand searching reference lists (Figure 1). After exclusion of duplicates, 445 articles were screened, and 29 full text articles were reviewed for eligibility. A total of 19 articles [7,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] were included in the review and two articles [23,31] were eligible for a meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow chart of study selection.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 2. The studies were grouped into four categories according to the nature of the intervention: behavioural, environmental, multifaceted and nutritional interventions. Seven studies [21,22,26,27,28,29,36] (37%) utilised a pre-test post-test design and five studies [23,24,25,33,39] (26%) were randomised controlled trials. Four studies [30,35,37,38] (21%) were randomised controlled crossover trial, two studies [31,32] were cluster controlled trials and one study [7] was a retrospective analysis. Nine studies [7,22,25,26,27,29,33,35,38] (47.4%) were conducted in the United States of America, four [21,28,32,39] (21%) in the United Kingdom and two [23,24] (%) in Australia. One study was conducted in each of Canada [37], Ireland [30], Japan [36] and Taiwan [31].

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 19).

3.3. Risk of Bias

Assessment of the quality of the included studies are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Evaluation of the risk of bias was rated as neutral for nine studies [21,22,27,28,29,30,32,35,36] (47.3%) and positive for ten studies [7,23,24,25,26,31,33,37,38,39] (52.6%). Of the nine neutral studies, information on selection of study participants, use of blinding and outcome measures were most frequently reported as unclear therefore contributing to the neutral ratings. Three of the studies rated as positive [25,26,31] had minor discrepancies with validity questions relating to selection criteria, comparable groups and intervention. However, these studies were determined to have a low risk of bias overall.

3.4. Participant Characteristics

A total of 978 participants were reported across the nineteen included studies. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 9 to 122 (average sample size was 54 participants). Thirteen studies [7,22,23,25,26,30,31,32,33,36,37,38,39] (68.4%) had a higher number of females than males. Cognitive impairment was present in twelve studies [23,24,25,26,27,29,31,32,33,35,36,39] (63%) and this varied from mild to severe. Six studies [7,22,28,30,37,38] did not report the cognition status of participants. Fifteen studies [21,22,25,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39] (79%) were undertaken in nursing homes or long-term care facilities. Of the six studies [7,23,24,27,30,39] conducted in hospital settings, four [7,23,24,30] included patients with dysphagia. These patients were from stroke units, rehabilitation facilities and subacute units.

3.5. Hydration Interventions

The results of the interventions can be seen in Table 3. The average intervention duration ranged from 3 days to 12 months.

Table 3.

Results of included studies (n = 19).

3.6. Behavioural Strategies

Seven included studies [21,25,31,33,36,38,39] utilised behavioural interventions. Allen et al. [39] investigated whether participants consuming nutritional supplements through a glass/beaker compared through a straw inserted in the container influenced fluid intake. Residents consumed statistically significantly more supplement drinks from a glass/beaker compared to those who consumed the drink through a straw (64.6 ± 34.3% vs. 57.3 ± 37.0%, p = 0.027).

Bak et al. [21] investigated the design of drinking vessels and their influence on fluid intake. There was a statistically significant increase in fluid intake at breakfast time (p = 0.03). However, this result is not clinically significant as the change in intake was only 70 mL in total.

Lin [31] provided unrestricted drinks choice as part of an intervention to reduce bacteriuria rates in nursing home residents. The change in fluid intake was statistically significant in the intervention group from 1449 mL to 1732 mL (p < 0.01). In the control group average fluid intake increased slightly from 1539 mL to 1548 mL however this was not statistically significant (p = 0.643). No significance value was determined for the urine specific gravity however the value was slightly lower in the control group than the intervention (1.009 vs. 1.012, respectively). These results fall within the normal range and indicate normal urine osmolality.

Schnelle et al. [33] offered beverage choices to residents’ multiple times a day to improve fluid intake and compared the results to usual care. The intervention group consumed significantly higher amounts of fluid compared to the control group (399 ± 186 mL vs. 56.2 ± 118 mL, p < 0.001).

Simmons et al. [25] provided daily verbal prompting to drink with the aim to increase fluid intake. Serum osmolality significantly declined in both groups overtime (p < 0.05) however changes in BUN:Cr were not significant (p > 0.05). There was a significant increase in fluid intake between meals with each phase of prompting (p < 0.001). Changes in serum osmolality were small although changes in overall fluid intake were clinically significant across the three phases.

Spangler et al. [38] employed a combined strategy of offering beverage choices and assistance with toileting to nursing home residents every 1.5 h. Urinometer scores at baseline indicated 25% of residents were dehydrated (score > 20) and post intervention all residents had scores < 20 indicating absence of dehydration (p < 0.002).

Tanaka et al. [36] provided residents with beverage choices in between meals and staff offered encouragement to drink with the aim for residents to consume 1500 mL per day. Fluid intake significantly increased after the intervention was implemented (1146.4 ± 365.2) compared to baseline (881.1 ± 263.8, p < 0.001).

3.7. Environmental Strategies

Environmental approaches were applied in four studies [22,29,32,35]. Dunne et al. [29] assessed the effect of low and high contrast tableware compared to white tableware on fluid intake in nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. This occurred as two separate studies one year apart. The first study using high contrast red tableware demonstrated a significant mean percent increase of 84% for liquid between baseline and intervention (p = 0.001). In the follow up study, the mean percent increase in liquid intake for high contrast blue was 29.8% (p < 0.05).

Holzapfel et al. [35] assigned nursing home residents to three groups where a feeding assistant would provide food and beverages to residents in a specific position (standing, sitting or position chosen by feeding assistant). Statistically significant results were observed with fluid intake at day 5 comparing the control group (choice of position by assistant) and experimental groups (sitting or standing) however all other results at different time points were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Kenkmann et al. [32] implemented a program to increase the availability and choice of drinks as well as improve the social and physical environment at mealtimes. Rates of dehydration dropped in both intervention and control care homes (16% to 9% and 46% to 39% respectively) but the significance of this result was not reported. The relative risk of being dehydrated in an intervention home compared to a control home was 0.36 (CI 0.06 to 2.04, p = 0.25). There was also a reduced rate of falls by 24% but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Robinson and Rosher [22] implemented a five week hydration program (increased availability and choice of drinks using a colourful beverage cart) in a nursing home aiming to reach an additional 450 mL of fluid intake at mid-morning and mid-afternoon. The percent of residents meeting the fluid goal was 53% with 24% not meeting the goal every time. No significance value was reported. There was a significant increase in total body water during the program and significant decrease in total body water once the program ceased (p = 0.001). The number of bowel movements increased significantly (p = 0.04) and the number falls declined significantly (p = 0.05).

3.8. Multifaceted Strategies

Three studies [26,27,28] applied multifaceted interventions to address hydration and fluid intake. Mentes and Culp [26] provided 180 mL of fluid with medication administration, providing drinks in between meals as well as offering a one hour time period where non-alcoholic cocktails are served (also known as happy hour) twice a week in the afternoon. The percent meeting fluid goals, urine colour and specific gravity did not increase significantly for either intervention or control group (p = 0.08). Incidence of HLEs was 3 events per 63 days of follow-up for the intervention group and 6 events per 60 days of follow-up for the control group but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.39).

Smith et al. [27] utilised a three-pronged approach (providing flavoured water, using larger cups and increased prompting to drink by nurses) to improve fluid intake. Fluid intake increased with the mean fluid intake at baseline being 1551 mL compared to 2225 mL post intervention.

Wilson et al. [28] implemented an intervention that included drinks being provided in between main meals, implementation of protected drinks time and increasing choice through a drinks menu. Mean fluid intake at Home A < 1500 mL per day whilst mean fluid intake at Home B was >1500 mL. No statistically significant value was reported. There was no change in the incidence of HLEs however there was a significant decrease in the use of laxatives in both homes (p < 0.05).

3.9. Nutritional Strategies

Five studies [7,23,24,30,37] used strategies targeted at improving overall nutrition and fluid intake in people with dysphagia. Howard et al. [7] conducted a retrospective analysis on an observational study of twenty patients with dysphagia who had received nectar thick and textured thin fluids during their hospital stay. Creatinine and sodium levels significantly increased whilst on the nectar thick diet (p = 0.047, p = 0.014 respectively). Although serum urea increased when on a nectar thick diet this change was not statistically significant (p = 0.07). When patients changed over to the textured thin liquids, serum urea dropped significantly (p = 0.06). Creatinine decreased into the normal range, but the change was not significant (p = 0.63).

Karagiannis et al. [23] implemented a water protocol in patients with dysphagia for five days whilst the control group could only consume thickened fluids. Patients with dysphagia had access to both thickened fluids and water between meals. Fluid intake increased significantly in the intervention group receiving the water protocol (1428 ± 7.0 mL to 1767 ± 10.7 mL, p < 0.01). The number of lung complications was significantly higher in the intervention group with 6 cases reported compared to zero in the control group (p < 0.05).

McCormick et al. [30] utilised a cross over design to determine if commercially thickened fluids or fluids thickened at the bedside increased fluid intake and influenced rates of constipation. The difference in fluid intake between the two interventions were minimal with 795 mL of pre thickened liquids consumed compared to 785 mL consumed pre thickened drinks at the bedside (p = 0.47). No changes in constipation rates were observed.

Murray et al. [24] applied the same water protocol as previously described by Karagiannis et al. [23] to patients with dysphagia for two weeks. The intervention group had a similar intake to the control group (1103 ± 215 mL, 1103 ± 247 mL respectively, p = 0.998). Although, the type of fluid in the intervention was water, it did not lead to an increase in hydration using the BUN:Cr as a proxy for hydration. The control group had a significantly higher incidence of UTIs compared to the intervention group (p = 0.024). There were no cases of pneumonia diagnosed during the intervention and no significant differences in constipation were discovered between both groups (p = 0.733). Taylor and Barr [37] implemented a crossover study to assess if a 3 day meal pattern compared to a five day meal pattern improved fluid intake. Fluid intake was higher at with five meals (698 ± 156 mL) compared to three meals (612 ± 176 mL, p = 0.003).

3.10. Hydration Linked Events

Eight studies [22,23,24,26,28,30,32,33] used HLEs as an indirect measure of hydration status and intervention effectiveness. HLEs measured included lung complications, falls, constipation, UTIs, laxative and antibiotic use. Five studies [22,24,26,32,33] reported improvements in HLEs with implementing a hydration intervention. Two studies [28,30] observed no differences in HLEs, and one study [23] observed adverse effects on lung function from use of water in people with dysphagia.

3.11. Patient Satisfaction

Six studies [7,21,22,23,24,32] gathered information on patient satisfaction. Information was collected in the form of a Likert scale, survey or recording of comments made during the intervention period. Only four studies [7,23,24,32] analysed the satisfaction data and three of the studies [7,24,32] reported no significant differences in satisfaction. One study [23] reported a significant increase in satisfaction with drinks but not in overall positive feeling.

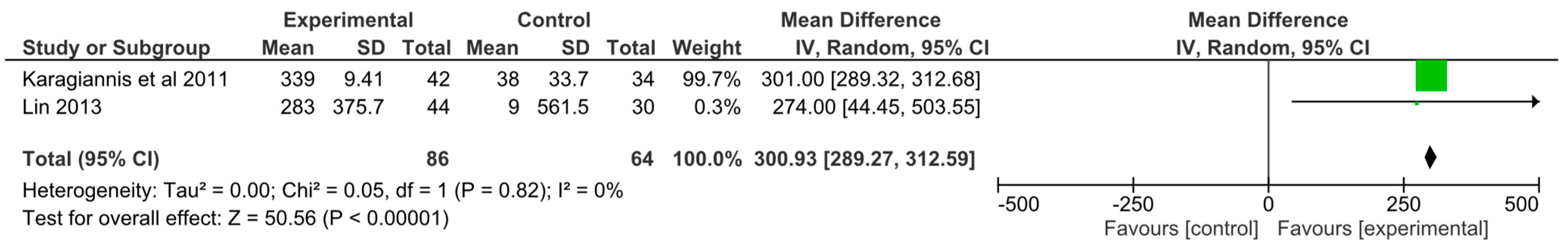

3.12. Meta-Analysis

Only two studies were able to be included in the meta-analysis. Karagiannis et al. [23] implemented a nutritional intervention and Lin [31] implemented a behavioural intervention. Overall, groups receiving interventions to improve hydration consumed 300.93 mL more fluid per day than those in the intervention groups (95% confidence interval 289.27 mL, 312.59 mL, I2 = 0%, p < 0.00001). The forest plot for this analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the results from random effects meta-analysis on fluid intake. Results are presented as mean difference (MD) between baseline and post intervention with the corresponding 95% confidence interval.

4. Discussion

This systematic review investigated the impact of interventions on improving hydration in older adults in nursing homes and hospital settings. Interestingly, only nineteen studies were eligible to be included in this review, which is concerning as dehydration is known to be a key problem in the geriatric population [1,40]. The findings of this systematic review are threefold. Firstly, behavioural interventions were associated with positive effects on hydration and fluid intake whilst environmental, multifaceted and nutritional interventions reported mixed results. Behavioural interventions involving verbal prompting or increased choice and availability of drinks were also associated with improvement in hydration. While metanalyses of outcomes were limited to daily fluid intake due to heterogeneous reporting of outcomes, it was clear that an improvement in fluid intake of 300 mL per day is both clinically as well as statistically significant. HLEs were reported to improve in half of the studies that measured this outcome and satisfaction rates generally observed no significant changes with implementation of an intervention.

Multifaceted interventions appear to be more difficult to implement than single component interventions as they attempt to address multiple barriers at different levels. In theory, these interventions should be more effective as they target several barriers simultaneously [41]. However multifaceted interventions generally require more resources and are more difficult to sustain [41]. This is consistent with the findings of other interventions implemented in aged care and hospital settings [42,43,44], where resource intensive interventions and organisational support contribute significantly to intervention success [42,43,44]. Interestingly, a previous systematic review on hydration interventions in institutionalised settings found multicomponent interventions showing a trend towards increased fluid intake [20]. This review included non-English articles and the sample was specific to institutionalised settings which may explain the difference in results.

The second key finding was that few studies used objective measures to measure hydration or used clinical measures for assessment of hydration that are appropriate for the elderly population. Furthermore, only one study used the gold standard of serum osmolality. Aside from serum osmolality and fluid balance charts, no other methods utilised have been validated to measure hydration in the elderly population. Fluid balance charts are considered the best approach for monitoring daily intake but there are obvious concerns around their accuracy as intakes are usually estimated and not precisely measured [45]. In this study, clinical measures were found to be ineffective when compared to the reference standard in older adults [46]. The precision of BUN:Cr ratio and urinary indices is impacted by renal dysfunction which is common in older adults thus is likely to be inappropriate for widespread use [18] Hydration linked events can also be caused by other factors such as medications or health conditions [47]. These concerns surrounding the measurement of hydration are noted in another systematic review investigating hydration in patients with dysphagia due to stroke [48]. The rationale for using these assessment methods was commonly cited as ease of use, or to replicate the method from previous studies or population groups or the methods was validated against another measure [7,22,24,26,28,30,32]. The heterogeneity in clinical assessment methods to evaluate hydration can therefore potentially explain part of the variation in intervention success.

The third key finding of this study is that there is a limited number of studies exploring the topic of hydration in acutely unwell hospitalised patients. Of the five articles conducted in hospital settings, only one study included patients from an acute hospital setting. Patients in acute hospitals typically have a shorter length of stay which can impact the true effect of the intervention. Other common barriers reported in the literature for acute hospital interventions include staff workload, time restraints and staff attitudes towards the intervention [49]. Additionally, a recent qualitative study in an acute hospital indicated that patients felt drinking was a task rather than a pleasurable activity [45]. It was also emphasised that the social interaction that plays a role in drinking was largely underplayed [45]. This point is supported by an unpublished study from a metropolitan teaching hospital in Sydney indicated that a non-alcoholic happy hour trolley that included social interaction was effective at improving fluid intake in older adults.

There are several strengths to this review. A systematic approach to searching databases and the use of multiple databases increased the ability to gather all relevant articles. A clear inclusion criterion was used to determine study eligibility and no study design limiters were applied. This review attempted to capture the evidence from a broad perspective by not focusing on a specific subset of the elderly population. Limitations of this review include restricting the studies to papers written in the English language only. The low-quality rating of studies also suggests the certainty of our findings should be used with caution. The search terms utilised in this review may also not capture all the evidence on hydration interventions in elderly patients or residents. The generalisability of the findings may be impacted by the greater number of the studies conducted in nursing home studies than hospital studies and most hospital studies were conducted in patients with dysphagia due to stroke.

Several recommendations arise from this research. There is a critical need for more intervention studies using validated methods for assessment of hydration in older adults to determine successful hydration strategies. This would enable comparisons between studies to be made more easily. In addition, studies exploring interventions in the acute hospital population are also required as there were no studies identified in this review that included the general population. Ideally, fluid balance charts and serum osmolality or the use of the Khajuria–Krahn formula [17] should be used to determine intervention success. These methods are considered the best approach when monitoring intake and hydration and can be easily incorporated in routine practice [50]. Studies in this review are charted below using the Behaviour Change Wheel [51] to determine what elements of behaviour change have not yet been targeted (Table 4). There are a lack of interventions addressing education, incentivisation, coercion, training, modelling and restriction aspects of the behaviour change wheel. When planning future interventions these areas should be considered to determine the impact on intervention success. Additionally, the collection of qualitative data with recipients of interventions as well as nursing staff may be beneficial to better understand appropriate methods, perceived barriers and ease of implementation [45].

Table 4.

Characterisation of interventions using categories from the Behaviour Change Wheel [51].

This review examined the impact of interventions to improve hydration in acutely unwell and institutionalised older adults. The major finding was that behavioural interventions utilising verbal prompting and increased availability or choice of drinks were associated with improvements in fluid intake and hydration. When pooled, interventions can improve fluid intake by approximately 300 mL per day. However, further high-quality studies are needed and in additional patient groups and acute care settings. There were limited included studies in this review, of suboptimal quality and large variations in intervention design and evaluation. This highlights the need for more rigorous intervention implementation using validated and population appropriate methods to determine intervention effectiveness. High quality studies using serum osmolality or Khajuria–Krahn [17] formula which can calculate plasma osmolarity in conjunction with fluid balance charts will be of benefit to researchers and clinicians. This is particularly important in the acute clinical setting where a successful intervention could be implemented into practice and result in reduced dehydration related outcomes and length of stay.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu13103640/s1, Table S1: Search terms (CINAHL); Table S2: Risk of Bias Assessment on Included Studies (n = 19).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.B. and K.L.; methodology, C.B., K.L.; formal analysis, C.B., K.L.; data curation, C.B., K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.; writing—review and editing, C.B., A.C., M.H., K.L.; supervision, K.L.; project administration, C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at Prince of Wales Hospital Randwick, New South Wales for assistance with this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Begum, M.N.; Johnson, C.S. A review of the literature on dehydration in the institutionalized elderly. e-SPEN Eur. E-J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 5, e47–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wotton, K.; Crannitch, K.; Munt, R. Prevalence, risk factors and strategies to prevent dehydration in older adults. Contemp. Nurse 2008, 31, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanti, A.; Harvey, K.; Ash, S.; Battistutta, D. Clinical assessment of dehydration in older people admitted to hospital: What are the strongest indicators? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2008, 47, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Holyday, M. How Do We Stop Starving and Dehydrating Our Patients on Dysphagia Diets? Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.; Miller, M.; Doeltgen, S.; Scholten, I. Intake of thickened liquids by hospitalized adults with dysphagia after stroke. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2014, 16, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vivanti, A.P.; Campbell, K.L.; Suter, M.S.; Hannan-Jones, M.T.; Hulcombe, J.A. Contribution of thickened drinks, food and enteral and parenteral fluids to fluid intake in hospitalised patients with dysphagia. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2009, 22, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howard, M.M.; Nissenson, P.M.; Meeks, L.; Rosario, E.R. Use of Textured Thin Liquids in Patients With Dysphagia. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2018, 27, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.R.; Tariq, S.H.; Makhdomm, S.; Haddad, R.; Moinuddin, A. Physician misdiagnosis of dehydration in older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2004, 5, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R.; Cote, T.R.; Lawhorne, L.; Levenson, S.A.; Rubenstein, L.Z.; Smith, D.A.; Stefanacci, R.G.; Tangalos, E.G.; Morley, J.E.; Council, D. Understanding clinical dehydration and its treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjo, I.; Amaral, T.F.; Afonso, C.; Borges, N.; Santos, A.; Moreira, P.; Padrao, P. Are hypohydrated older adults at increased risk of exhaustion? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 33, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentes, J.C.; Kang, S. Hydration Management. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2020, 46, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Barber, J.; Campbell, E.S. Economic burden of dehydration among hospitalized elderly patients. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2004, 61, 2534–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, J.; Corbett, J.; Forni, L.; Hooper, L.; Hughes, F.; Minto, G.; Moss, C.; Price, S.; Whyte, G.; Woodcock, T.; et al. A multidisciplinary consensus on dehydration: Definitions, diagnostic methods and clinical implications. Ann. Med. 2019, 51, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handu, D.; Moloney, L.; Wolfram, T. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Methodology for Conducting Systematic Reviews for the Evidence Analysis Library. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, L.E. Assessing hydration status: The elusive gold standard. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 575S–584S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.; Abdelhamid, A.; Attreed, N.J.; Campbell, W.W.; Channell, A.M.; Chassagne, P.; Culp, K.R.; Fletcher, S.J.; Fortes, M.B.; Fuller, N.; et al. Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khajuria, A.; Krahn, J. Osmolality revisited—Deriving and validating the best formula for calculated osmolality. Clin. Biochem. 2005, 38, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.; Bunn, D.K.; Abdelhamid, A.; Gillings, R.; Jennings, A.; Maas, K.; Twomlow, E.; Hunter, P.R.; Shepstone, L.; Potter, J.F.; et al. Water-loss (intracellular) dehydration assessed using urinary tests: How well do they work? Diagnostic accuracy in older people. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hodgkinson, B.; Evans, D.; Wood, J. Maintaining oral hydration in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2003, 9, S19–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunn, D.; Jimoh, F.; Wilsher, S.H.; Hooper, L. Increasing fluid intake and reducing dehydration risk in older people living in long-term care: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bak, A.; Wilson, J.; Tsiami, A.; Loveday, H. Drinking vessel preferences in older nursing home residents: Optimal design and potential for increasing fluid intake. Br. J. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.B.; Rosher, R.B. Can a beverage cart help improve hydration? Geriatr. Nurs. 2002, 23, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagiannis, M.J.; Chivers, L.; Karagiannis, T.C. Effects of oral intake of water in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, J.; Doeltgen, S.; Miller, M.; Scholten, I. Does a Water Protocol Improve the Hydration and Health Status of Individuals with Thin Liquid Aspiration Following Stroke? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dysphagia 2016, 31, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simmons, S.F.; Alessi, C.; Schnelle, J.F. An intervention to increase fluid intake in nursing home residents: Prompting and preference compliance. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentes, J.C.; Culp, K. Reducing hydration-linked events in nursing home residents. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2003, 12, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Velasco, R.; John, S.; Kaufman, R.S.; Melzer, E. An Innovative Approach to Adequate Oral Hydration in an Inpatient Geriatric Psychiatry Unit. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2019, 57, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.; Bak, A.; Tingle, A.; Greene, C.; Tsiami, A.; Canning, D.; Myron, R.; Loveday, H. Improving hydration of care home residents by increasing choice and opportunity to drink: A quality improvement study. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1820–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, T.E.; Neargarder, S.A.; Cipolloni, P.B.; Cronin-Golomb, A. Visual contrast enhances food and liquid intake in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, S.E.; Stafford, K.M.; Saqib, G.; Chroinin, D.N.; Power, D. The efficacy of pre-thickened fluids on total fluid and nutrient consumption among extended care residents requiring thickened fluids due to risk of aspiration. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 714–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shu-Yuan, L. A Pilot Study: Fluid Intake and Bacteriuria in Nursing Home Residents in Southern Taiwan. Nurs. Res. 2013, 62, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkmann, A.; Price Gill, M.; Bolton, J.; Hooper, L. Health, wellbeing and nutritional status of older people living in UK care homes: An exploratory evaluation of changes in food and drink provision. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnelle, J.F.; Leung, F.W.; Rao, S.S.C.; Beuscher, L.; Keeler, E.; Clift, J.W.; Simmons, S. A Controlled Trial of an Intervention to Improve Urinary and Fecal Incontinence and Constipation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. (JAGS) 2010, 58, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Go, A.S.; Mozaffarian, D.; Roger, V.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Berry, J.D.; Borden, W.B.; Bravata, D.M.; Dai, S.; Ford, E.S.; Fox, C.S.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2013 Update A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 127, E6–E245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, S.K.; Ramirez, R.F.; Layton, M.S.; Smith, I.W.; Sagl-Massey, K.; DuBose, J.Z. Feeder position and food and fluid consumed by nursing home residents. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 1996, 22, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Nagata, K.; Tanaka, T.; Kuwano, K.; Endo, H.; Otani, T.; Nakazawa, M.; Koyama, H. Can an individualized and comprehensive care strategy improve urinary incontinence (UI) among nursing home residents? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2008, 49, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.A.; Barr, S.I. Provision of small, frequent meals does not improve energy intake of elderly residents with dysphagia who live in an extended-care facility. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spangler, P.F.; RisLEY, T.R.; Bilyew, D.D. The management of dehydration and incontinence in nonambulatory geriatric patients. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1984, 17, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allen, V.J.; Methven, L.; Gosney, M. Impact of serving method on the consumption of nutritional supplement drinks: Randomized trial in older adults with cognitive impairment. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, L.; Bunn, D.; Jimoh, F.O.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J. Water-loss dehydration and aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 136–137, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Squires, J.E.; Sullivan, K.; Eccles, M.P.; Worswick, J.; Grimshaw, J.M. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals' behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, P.; Kifley, A.; Kurrle, S.; Cameron, I.D. Process outcomes of a multifaceted, interdisciplinary knowledge translation intervention in aged care: Results from the vitamin D implementation (ViDAus) study. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abdelhamid, A.; Bunn, D.; Copley, M.; Cowap, V.; Dickinson, A.; Gray, L.; Howe, A.; Killett, A.; Lee, J.; Li, F.; et al. Effectiveness of interventions to directly support food and drink intake in people with dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milisen, K.; Lemiengre, J.; Braes, T.; Foreman, M.D. Multicomponent intervention strategies for managing delirium in hospitalized older people: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, H.; Cloete, J.; Dymond, E.; Long, A. An exploration of the hydration care of older people: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, L.; Abdelhamid, A.; Campbell, W.; Chassagne, P.; Fletcher, S.J.; Fortes, M.B.; Gaspar, P.M.; Gilbert, D.J.; Heathcote, A.C.; Kajii, F.; et al. O3.20: Non-invasive clinical and physical signs, symptoms and indications for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people: A diagnostic accuracy systematic review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 5, S69–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; D’Anci, K.E.; Rosenberg, I.H. Water, hydration, and health. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schettino, M.S.T.B.; Silva, D.C.C.; Pereira-Carvalho, N.A.V.; Vicente, L.C.C.; Friche, A.A.d.L. Dehydration, stroke and dysphagia: Systematic review. Audiol.—Commun. Res. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geerligs, L.; Rankin, N.M.; Shepherd, H.L.; Butow, P. Hospital-based interventions: A systematic review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation processes. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hooper, L.; Abdelhamid, A.; Ali, A.; Bunn, D.K.; Jennings, A.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Potter, J.F.; Hunter, P.R.; Shepstone, L.; John, W.G.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of calculated serum osmolarity to predict dehydration in older people: Adding value to pathology laboratory reports. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).