A 12-Week Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluating the Effect of Supplementation with a Spinach Extract on Skeletal Muscle Fitness in Adults Older Than 50 Years of Age

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Intervention and Study Procedures

2.3. Physical Resistance Training Program

2.4. Study Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Body Composition

3.3. Muscle Function

3.4. Muscle Quality

3.5. Changes in Muscle Parameters According to Gender

3.6. Health-Related Quality of Life

3.7. Nutritional Survey

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eckstrom, E.; Neukam, S.; Kalin, L.; Wright, J. Physical activity and healthy aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 36, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distefano, G.; Goodpaster, B.H. Effects of exercise and aging on skeletal muscle. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a029785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McLeod, M.; Breen, L.; Hamilton, D.L.M.; Philp, A. Live strong and prosper: The importance of skeletal muscle strength for healthy ageing. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Askow, A.T.; McKenna, C.F.; Box, A.G.; Khan, N.A.; Petruzzello, S.J.; De Lisio, M.; Phillips, S.M.; Burd, N.A. Of sound mind and body: Exploring the diet-strength interaction in healthy aging. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, C.N.; Lee, Y.S.; Belyea, M. Physical activity, benefits, and barriers across the aging continuum. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 44, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, W. Effects of resistance training on exercise capacity in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallauria, F.; Cittadini, A.; Smart, N.A.; Vigorito, C. Resistance training and sarcopenia. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2016, 84, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Serra-Rexach, J.A.; Bustamante-Ara, N.; Hierro Villarán, M.; González Gil, P.; Sanz Ibáñez, M.J.; Blanco Sanz, N.; Ortega Santamaría, V.; Gutiérrez Sanz, N.; Marín Prada, A.B.; Gallardo, C.; et al. Short-term, light- to moderate-intensity exercise training improves leg muscle strength in the oldest old: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, T.C.; Fragala, M.S.; Stout, J.R.; Emerson, N.S.; Beyer, K.S.; Oliveira, L.P.; Hoffman, J.R. Muscle architecture and strength: Adaptations to short-term resistance training in older adults. Muscle Nerve 2014, 49, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guizelini, P.C.; de Aguiar, R.A.; Denadai, B.S.; Caputo, F.; Greco, C.C. Effect of resistance training on muscle strength and rate of force development in healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 102, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fragala, M.S.; Cadore, E.L.; Dorgo, S.; Izquierdo, M.; Kraemer, W.J.; Peterson, M.D.; Ryan, E.D. Resistance training for older adults: Position statement from the National Strength and Conditioning Association. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2019–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waijers, P.M.; Feskens, E.J.; Ocké, M.C. A critical review of predefined diet quality scores. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bloom, I.; Shand, C.; Cooper, C.; Robinson, S.; Baird, J. Diet quality and sarcopenia in older adults: A systematic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Govindaraju, T.; Sahle, B.W.; McCaffrey, T.A.; McNeil, J.J.; Owen, A.J. Dietary patterns and quality of life in older adults: A systematic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Atallah, N.; Adjibade, M.; Lelong, H.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Assmann, K.E.; Kesse-Guyot, E. How healthy lifestyle factors at midlife relate to healthy aging. Nutrients 2018, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Quan, H.; Kang, S.G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. Nutraceuticals in the prevention and treatment of the muscle atrophy. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, C.S.; Wilkinson, D.J.; Phillips, B.E.; Smith, K.; Etheridge, T.; Atherton, P.J. “Nutraceuticals” in relation to human skeletal muscle and exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 312, E282–E299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondanelli, M.; Rigon, C.; Perna, S.; Gasparri, C.; Iannello, G.; Akber, R.; Alalwan, T.A.; Freije, A.M. novel insights on intake of fish and prevention of sarcopenia: All reasons for an adequate consumption. Nutrients 2020, 12, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, S.M.; Reginster, J.Y.; Rizzoli, R.M.; Shaw, S.C.; Kanis, J.A.; Bautmans, I.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Bruyère, O.; Cesari, M.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; et al. Does nutrition play a role in the prevention and management of sarcopenia? Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isenmann, E.; Ambrosio, G.; Joseph, J.F.; Mazzarino, M.; de la Torre, X.; Zimmer, P.; Kazlauskas, R.; Goebel, C.; Botrè, F.; Diel, P.; et al. Ecdysteroids as non-conventional anabolic agent: Performance enhancement by ecdysterone supplementation in humans. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Báthori, M.; Tóth, N.; Hunyadi, A.; Márki, A.; Zádor, E. Phytoecdysteroids and anabolic-androgenic steroids--structure and effects on humans. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bialek, P.; Morris, C.; Parkington, J.; St Andre, M.; Owens, J.; Yaworsky, P.; Seeherman, H.; Jelinsky, S.A. Distinct protein degradation profiles are induced by different disuse models of skeletal muscle atrophy. Physiol. Genom. 2011, 43, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimlamai, T.; Dodd, S.L.; Borst, S.E.; Park, S. Clenbuterol induces muscle-specific attenuation of atrophy through effects on the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franco, R.R.; de Almeida Takata, L.; Chagas, K.; Justino, A.B.; Saraiva, A.L.; Goulart, L.R.; de Melo Rodrigues Ávila, V.; Otoni, W.C.; Espindola, F.S.; da Silva, C.R. A 20-hydroxyecdysone-enriched fraction from Pfaffia glomerata (Spreng.) pedersen roots alleviates stress, anxiety, and depression in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, M.M.; Zwetsloot, K.A.; Arthur, S.T.; Sherman, C.A.; Huot, J.R.; Badmaev, V.; Grace, M.; Lila, M.A.; Nieman, D.C.; Shanely, R.A. Phytoecdysteroids do not have anabolic effects in skeletal muscle in sedentary aging mice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.M.; Kutzler, L.W.; Boler, D.D.; Drnevich, J.; Killefer, J.; Lila, M.A. Continuous infusion of 20-hydroxyecdysone increased mass of triceps brachii in C57BL/6 mice. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilborn, C.D.; Taylor, L.W.; Campbell, B.I.; Kerksick, C.; Rasmussen, C.J.; Greenwood, M.; Kreider, R.B. Effects of methoxyisoflavone, ecdysterone, and sulfo-polysaccharide supplementation on training adaptations in resistance-trained males. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2006, 3, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Syrov, V.N. Mechanism of the anabolic action of phytoecdisteroids in mammals. Nauchnye Doklady Vysshei Shkoly Biologicheskie Nauki 1984, 11, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick-Feldman, J.I. Phytoecdysteroids. Understanding Their Anabolic Activity. Ph.D. Thesis, The State University of New Jersey , New Brunswick, NJ, USA, May 2009. Available online: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/25806/PDF/1/play/ (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Hirunsai, M.; Yimlamai, T.; Suksamrarn, A. Effect of 20-hydroxyecdysone on proteolytic regulation in muscle atrophy. In Vivo 2016, 30, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorelick-Feldman, J.; Cohick, W.; Raskin, I. Ecdysteroids elicit a rapid Ca2+ flux leading to Akt activation and increased protein synthesis in skeletal muscle cells. Steroids 2010, 75, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- San Juan, A.F.; Dominguez, R.; Lago-Rodríguez, Á.; Montoya, J.J.; Tan, R.; Bailey, S.J. Effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on weightlifting exercise performance in healthy adults: A systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Thompson, C.; Wylie, L.J.; Vanhatalo, A. Dietary nitrate and physical performance. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 38, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.; Lewis, J.R.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Bondonno, C.P.; Devine, A.; Zhu, K.; Peeling, P.; Prince, R.L.; Hodgson, J.M. Dietary nitrate intake is associated with muscle function in older women. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierała, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Męczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.D.; Chen, H.C.; Huang, S.W.; Liou, T.H. The role of muscle mass gain following protein supplementation plus exercise therapy in older adults with sarcopenia and frailty risks: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denison, H.J.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A.; Robinson, S.M. Prevention and optimal management of sarcopenia: A review of combined exercise and nutrition interventions to improve muscle outcomes in older people. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jidovtseff, B.; Harris, N.K.; Crielaard, J.M.; Cronin, J.B. Using the load-velocity relationship for 1RM prediction. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á.; Freitas, T.T.; Camacho, A.; Jiménez-Diaz, J.F.; Alcaraz, P.-E. Acute physiological and performance responses to high-intensity resistance circuit training in hypoxic and normoxic conditions. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A. Physiological bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.; Antó, J.M. The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey (the SF-36 health questionnaire: An instrument for measuring clinical results. [Article in Spanish]. Med. Clin. 1995, 104, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, T.S.; Lean, M.E. A clinical perspective of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. JRSM Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 5, 2048004016633371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benito, P.J.; López-Plaza, B.; Bermejo, L.M.; Peinado, A.B.; Cupeiro, R.; Butragueño, J.; Rojo-Tirado, M.A.; González-Lamuño, D.; Gómez-Candela, C. Strength plus endurance training and individualized diet reduce fat mass in overweight subjects: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, B.M.; Nuckols, G.; Krieger, J.W. Sex differences in resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folland, J.P.; Williams, A.G. The adaptations to strength training: Morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; Wewege, M.A.; Hackett, D.A.; Keogh, J.W.L.; Hagstrom, A.D. Sex differences in adaptations in muscle strength and size following resistance training in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; DeHoyos, D.V.; Pollock, M.L.; Garzarella, L. Time course for strength and muscle thickness changes following upper and lower body resistance training in men and women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 81, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld, B.; Grgic, J. Evidence-based guidelines for resistance training volume to maximize muscle hypertrophy. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tracy, B.L.; Ivey, F.M.; Hurlbut, D.; Martel, G.F.; Lemmer, J.T.; Siegel, E.L.; Metter, E.J.; Fozard, J.L.; Fleg, J.L.; Hurley, B.F. Muscle quality. II. Effects of strength training in 65- to 75-yr-old men and women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999, 86, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, B.L.; Hurlbut, D.E.; Metter, E.J.; Hurley, B.F.; Rogers, M.A. Age and sex affect human muscle fibre adaptations to heavy-resistance strength training. Exp. Physiol. 2006, 91, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexell, J.; Downham, D. What is the effect of ageing on type 2 muscle fibres? J. Neurol. Sci. 1992, 107, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.J.; Bukhari, S.S.I.; Phillips, B.E.; Limb, M.C.; Cegielski, J.; Brook, M.S.; Rankin, D.; Mitchell, W.K.; Kobayashi, H.; Williams, J.P.; et al. Effects of leucine-enriched essential amino acid and whey protein bolus dosing upon skeletal muscle protein synthesis at rest and after exercise in older women. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvares, T.S.; Oliveira, G.V.; Volino-Souza, M.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Murias, J.M. Effect of dietary nitrate ingestion on muscular performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, N.F.; Leveritt, M.D.; Pavey, T.G. The effect of dietary nitrate supplementation on endurance exercise performance in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, C.; Gupta, S.; Adli, T.; Hou, W.; Coolsaet, R.; Hayes, A.; Kim, K.; Pandey, A.; Gordon, J.; Chahil, G.; et al. The effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on endurance exercise performance and cardiorespiratory measures in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Experimental Group (n = 23) | Placebo Group (n = 22) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Men | 4 | 4 | 0.894 |

| Women | 19 | 18 | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 59.2 ± 5.6 | 58.6 ± 6.6 | 0.750 |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 69.3 ± 8.2 | 68.0 ± 9.7 | 0.633 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 25.9 ± 3.0 | 26.1 ± 3.5 | 0.819 |

| Percentage of fat mass, mean ± SD | 40.3 ± 5.0 | 41.8 ± 5.3 | 0.341 |

| SBP, mmHg, mean ± SD | 128.0 ± 20.4 | 123.1 ± 14.3 | 0.353 |

| DBP, mmHg, mean ± SD | 82.6 ± 11.9 | 80.3 ± 9.1 | 0.473 |

| Men (SMI ≤ 7.0 kg/m2), * mean ± SD, (n) | 5.66 ± 0.00 (1) | 6.46 ± 0.31 (2) | 0.283 |

| Women (SMI ≤ 6.0 kg/m2), * mean ± SD, (n) | 5.44 ± 0.44 (14) | 5.40 ± 0.55 (15) | 0.793 |

| Variables | Experimental Group (n = 23) | Placebo Group (n = 22) | Time × Product Interaction p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | ||

| Body weight, kg | 69.3 ± 8.2 | 69.0 ± 8.4 | 0.374 | 68.0 ± 9.7 | 67.7 ± 9.7 | 0.361 | 0.975 |

| DEXA analysis | |||||||

| Fat mass, kg | 27.8 ± 4.1 | 27.4 ± 4.3 | 0.050 | 28.3 ± 4.9 | 27.7 ± 4.8 | 0.014 | 0.615 |

| Lean mass, kg | 39.0 ± 6.6 | 39.6 ± 6.8 | 0.001 | 37.7 ± 7.4 | 38.1 ± 7.3 | 0.020 | 0.254 |

| Muscle mass, kg | 38.8 ± 6.9 | 39.4 ± 6.9 | 0.001 | 37.5 ± 7.5 | 37.9 ± 7.4 | 0.016 | 0.429 |

| ASM, dominant leg, kg | 6.2 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 0.013 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 0.143 | 0.463 |

| Variables | Experimental Group (n = 23) | Placebo Group (n = 22) | Time × Product Interaction p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | ||

| Isokinetic dynamometry | |||||||

| At 60° s−1 knee extension | |||||||

| Peak torque, Nm | 91.6 ± 28.1 | 107.2 ± 26.6 | 0.001 | 93.6 ± 16.9 | 101.4 ± 18.0 | 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Total work for 1RM, J | 83.3 ± 23.3 | 101.5 ± 24.7 | 0.001 | 85.2 ± 13.6 | 94.3 ± 20.0 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Total work, J | 390.3 ± 115.3 | 474.4 ± 118.3 | 0.001 | 384.7 ± 85.6 | 445.6 ± 92.4 | 0.001 | 0.289 |

| Average power, W | 53.6 ± 17.8 | 63.4 ± 17.2 | 0.001 | 54.2 ± 9.8 | 60.3 ± 13.2 | 0.001 | 0.109 |

| At 180° s−1 knee extension | |||||||

| Peak torque, Nm | 58.6 ± 19.5 | 72.4 ± 19.3 | 0.001 | 60.9 ± 12.2 | 64.2 ± 12.9 | 0.143 | 0.002 |

| Total work for 1RM, J | 62.2 ± 22.3 | 79.2 ± 23.5 | 0.001 | 62.5 ± 12.3 | 68.4 ± 14.3 | 0.034 | 0.005 |

| Total work, J | 285.3 ± 100.9 | 363.3 ± 104.5 | 0.001 | 287.7 ± 61.0 | 317.3 ± 66.8 | 0.020 | 0.007 |

| Average power, W | 93.3 ± 35.6 | 115.1 ± 31.9 | 0.001 | 94.4 ± 22.3 | 102.2 ± 24.6 | 0.080 | 0.027 |

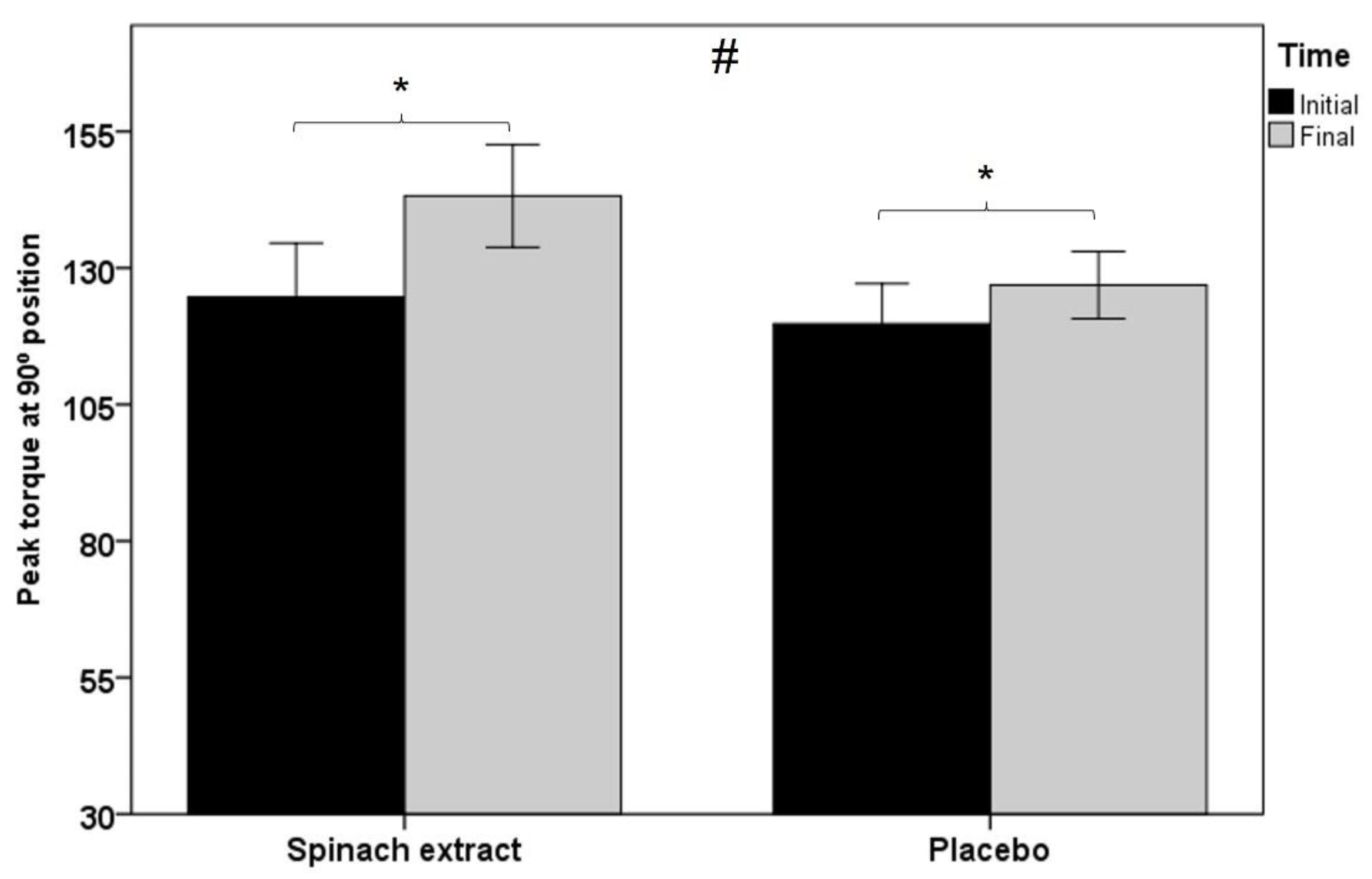

| Isometric dynamometry | |||||||

| At 90° knee position | |||||||

| Peak torque, Nm | 124.7 ± 47.3 | 143.2 ± 45.1 | 0.001 | 119.7 ± 34.7 | 126.9 ± 28.9 | 0.012 | 0.005 |

| Average peak torque, Nm | 118.7 ± 44.5 | 136.4 ± 44.7 | 0.001 | 114.4 ± 34.2 | 121.0 ± 29.4 | 0.008 | 0.002 |

| Handgrip strength, kg | |||||||

| Right hand | 25.7 ± 8.2 | 26.4 ± 7.1 | 0.193 | 24.8 ± 8.7 | 24.9 ± 7.9 | 0.823 | 0.449 |

| Left hand | 23.3 ± 7.4 | 25.4 ± 7.4 | 0.004 | 23.3 ± 7.8 | 24.3 ± 6.9 | 0.203 | 0.247 |

| Maximal dynamic force (1RM), kg | 43.2 ± 13.8 | 60.1 ± 16.7 | 0.001 | 41.4 ± 14.0 | 57.3 ± 15.1 | 0.001 | 0.729 |

| Variables | Experimental Group (n = 23) | Placebo Group (n = 22) | Time × Product Interaction p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | ||

| DEXA study | |||||||

| Muscle mass/peak isokinetic torque (60° s−1 extension), N × m/kg | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 0.001 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 0.002 | 0.024 |

| Muscle mass/peak isometric torque, N × m/kg | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 0.001 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 0.034 | 0.021 |

| ASM dominant leg | |||||||

| Muscle mass/peak isokinetic torque (60° s−1 extension), N × m/kg | 15.0 ± 4.2 | 17.2 ± 3.6 | 0.001 | 16.0 ± 2.6 | 17.1 ± 2.7 | 0.003 | 0.022 |

| Muscle mass/peak isometric torque, N × m/kg | 20.2 ± 6.1 | 22.9 ± 5.7 | 0.001 | 20.2 ± 4.5 | 21.2 ± 3.8 | 0.046 | 0.018 |

| Variable | Gender | Study Group | Baseline | Final End of Study | ∆ | Time p Value | Time × Product p Value | Time × Product × Gender p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle mass of the dominant lower limb, kg | Men | Experimental | 8.0 ± 1.7 | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.030 | 0.041 | 0.015 |

| Placebo | 7.7 ± 2.3 | 7.7 ± 2.1 | −0.05 | 0.455 | ||||

| Women | Experimental | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.005 | 0.712 | ||

| Placebo | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.020 | ||||

| Peak isokinetic torque (60° s−1 extension), Nm | Men | Experimental | 96.9 ± 36.7 | 114.4 ± 35.8 | 17.5 | 0.001 | 0.067 | 0.925 |

| Placebo | 112.7 ± 25.7 | 121.9 ± 21.8 | 9.2 | 0.05 | ||||

| Women | Experimental | 90.5 ± 27.1 | 105.7 ± 25.3 | 15.2 | 0.001 | 0.024 | ||

| Placebo | 89.4 ± 11.4 | 96.9 ± 14.0 | 7.5 | 0.001 | ||||

| Peak isometric torque (90° position), Nm | Men | Experimental | 127.0 ± 61 | 152.0 ± 61.0 | 25 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.085 |

| Placebo | 161.0 ± 55.0 | 160 ± 43.0 | −1 | 0.895 | ||||

| Women | Experimental | 124.0 ± 46.0 | 141.0 ± 43.0 | 17 | 0.001 | 0.05 | ||

| Placebo | 111.0 ± 21.0 | 119.0 ± 20.0 | 8 | 0.005 | ||||

| Muscle quality DEXA (muscle mass/peak isometric torque), N × m/kg | Men | Experimental | 2.52 ± 1.14 | 3.0 ± 1.12 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.036 | 0.333 |

| Placebo | 3.20 ± 0.90 | 3.20 ± 0.82 | 0 | 0.993 | ||||

| Women | Experimental | 3.36 ± 0.93 | 3.77 ± 0.83 | 0.41 | 0.001 | 0.106 | ||

| Placebo | 3.21 ± 0.66 | 3.41 ± 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.022 |

| SF-36 domain | Experimental Group (n = 23) | Placebo Group (n = 22) | Between-Group p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | Baseline | End of Study | Within-Group p Value | ||

| Physical functioning | 88.9 ± 9.6 | 90.9 ± 5.8 | 0.277 | 85.2 ± 13.0 | 88.2 ± 10.1 | 0.111 | 0.696 |

| Role physical | 89.1 ± 7.9 | 91.7 ± 6.3 | 0.023 | 85.2 ± 10.5 | 88.9 ± 7.1 | 0.002 | 0.518 |

| Bodily pain | 79.9 ± 19.2 | 81.1 ± 17.6 | 0.636 | 72.1 ± 23.3 | 73.2 ± 21.9 | 0.813 | 0.871 |

| General health | 66.1 ± 11.2 | 69.0 ± 14.5 | 0.210 | 73.6 ± 13.8 | 74.1 ± 17.6 | 0.832 | 0.465 |

| Vitality or energy/fatigue | 60.9 ± 16.0 | 62.8 ± 13.5 | 0.422 | 65.2 ± 13.4 | 65.0 ± 4.1 | 0.927 | 0.530 |

| Social functioning | 87.0 ± 16.2 | 91.3 ± 16.2 | 0.184 | 88.6 ± 17.6 | 92.0 ± 17.9 | 0.306 | 0.839 |

| Role emotional | 70.8 ± 11.1 | 78.0 ± 8.2 | 0.001 | 79.6 ± 10.5 | 83.9 ± 8.6 | 0.003 | 0.118 |

| Mental health | 66.6 ± 11.5 | 71.8 ± 11.6 | 0.049 | 73.1 ± 11.2 | 74.0 ± 17.7 | 0.732 | 0.249 |

| Self-reported health transition | 43.5 ± 21.6 | 41.3 ± 16.2 | 0.573 | 52.3 ± 7.4 | 37.5 ± 16.8 | 0.001 | 0.026 |

| Variables | Spinach Extract Group (n = 23) | Placebo Group (n = 22) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Study | Baseline | End of Study | |

| Calories (Kcal) | 1960.9 ± 39.9 | 2054.5 ± 45.3 | 2030.9 ± 45.0 | 1856.6 ± 49.6 |

| Carbohydrates, g | 256.9 ± 27.5 | 267.9 ± 25.3 | 213.1 ± 30.9 | 228.8 ± 44.5 |

| Fat, g | 66.5 ± 4.9 | 71.2 ± 9.4 | 91.3 ± 17.5 | 64.3 ± 15.5 |

| Proteins, g | 83.7 ± 4.2 | 85.6 ± 7.3 | 89.2 ± 3.9 | 91.5 ± 5.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Piñero, S.; Ávila-Gandía, V.; Rubio Arias, J.A.; Muñoz-Carrillo, J.C.; Losada-Zafrilla, P.; López-Román, F.J. A 12-Week Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluating the Effect of Supplementation with a Spinach Extract on Skeletal Muscle Fitness in Adults Older Than 50 Years of Age. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124373

Pérez-Piñero S, Ávila-Gandía V, Rubio Arias JA, Muñoz-Carrillo JC, Losada-Zafrilla P, López-Román FJ. A 12-Week Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluating the Effect of Supplementation with a Spinach Extract on Skeletal Muscle Fitness in Adults Older Than 50 Years of Age. Nutrients. 2021; 13(12):4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124373

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Piñero, Silvia, Vicente Ávila-Gandía, Jacobo A. Rubio Arias, Juan Carlos Muñoz-Carrillo, Pilar Losada-Zafrilla, and Francisco Javier López-Román. 2021. "A 12-Week Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluating the Effect of Supplementation with a Spinach Extract on Skeletal Muscle Fitness in Adults Older Than 50 Years of Age" Nutrients 13, no. 12: 4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124373

APA StylePérez-Piñero, S., Ávila-Gandía, V., Rubio Arias, J. A., Muñoz-Carrillo, J. C., Losada-Zafrilla, P., & López-Román, F. J. (2021). A 12-Week Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluating the Effect of Supplementation with a Spinach Extract on Skeletal Muscle Fitness in Adults Older Than 50 Years of Age. Nutrients, 13(12), 4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124373