Impact of Supplementation and Nutritional Interventions on Pathogenic Processes of Mood Disorders: A Review of the Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

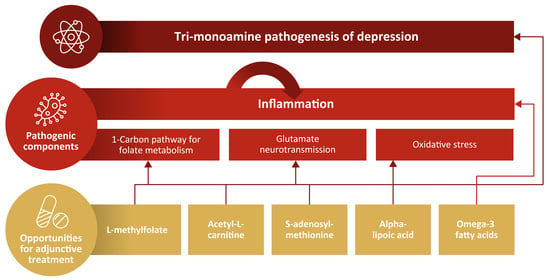

2. Proposed Nutritional and Other Novel Contributors to the Pathogenesis of MDD

3. Dysregulation of the One-Carbon Cycle in MDD

3.1. Vitamin B12 and Folate

3.2. Homocysteine

3.3. S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe)

4. Role of Amino Acids in MDD

4.1. L-acetylcarnitine (LAC)

4.2. Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA)

4.3. N-acetylcysteine (NAC)

4.4. L-tryptophan

5. Minerals

5.1. Zinc

5.2. Magnesium

6. Other Supplementation

6.1. Vitamin D

6.2. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

6.3. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acyl-CoA | acyl-coenzyme A |

| AE | adverse event |

| ALA | alpha-lipoic acid |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CGI | Clinical Global Impressions |

| CGI-S | Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| COMT | catechol-O-methyltransferase |

| CoQ10 | coenzyme Q10 |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DAG | diacylglycerol |

| DHLA | dihydrolipoic acid |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HPA | hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| hsCRP | high-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| IL-8 | interleukin-8 |

| IP3 | inositol triphosphate |

| LAC | L-acetylcarnitine |

| LCFA | long chain fatty acids |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MAOIs | monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| MAPK | mitogen activated protein kinase |

| MDD | major depressive disorder |

| mGlu 2 | type 2 metabotropic glutamate |

| mGlu | metabotropic glutamate |

| MMA | methylmalonic acid |

| MTHF | L-5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate |

| MTHFR | 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PIP | phosphatidylinositol |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RR | relative risk |

| SAH | S-adenosylhomocysteine |

| SAMe | S-adenosylmethionine |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SMD | standardized mean difference |

| SNRIs | serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| SSRIs | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| STAR*D | Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression |

| TCAs | tricyclic antidepressants |

| TDO | tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| VDRs | vitamin D receptors |

References

- Uher, R.; Payne, J.L.; Pavlova, B.; Perlis, R.H. Major depressive disorder in DSM-5: Implications for clinical practice and research of changes from DSM-IV. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissette, D.A.; Stahl, S.M. Modulating the serotonin system in the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2014, 19 (Suppl. S1), 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blier, P.; El Mansari, M. Serotonin and beyond: Therapeutics for major depression. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceskova, E.; Silhan, P. Novel treatment options in depression and psychosis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkelfat, C.; Ellenbogen, M.A.; Dean, P.; Palmour, R.M.; Young, S.N. Mood-lowering effect of tryptophan depletion. Enhanced susceptibility in young men at genetic risk for major affective disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1994, 51, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, P.; Samuelsson, M.; Asberg, M.; Traskman-Bendz, L.; Aberg-Wistedt, A.; Nordin, C.; Bertilsson, L. CSF 5-HIAA predicts suicide risk after attempted suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1994, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, D.; Rudge, S. The role of serotonin in depression and anxiety. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1995, 9 (Suppl. S4), 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Application, 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, A.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, H.J.; Yang, S.J. Nutritional Factors Affecting Mental Health. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2016, 5, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottiglieri, T.; Laundy, M.; Crellin, R.; Toone, B.K.; Carney, M.W.; Reynolds, E.H. Homocysteine, folate, methylation, and monoamine metabolism in depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 69, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.S.; Toone, B.K.; Carney, M.W.; Flynn, T.G.; Bottiglieri, T.; Laundy, M.; Chanarin, I.; Reynolds, E.H. Enhancement of recovery from psychiatric illness by methylfolate. Lancet 1990, 336, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N.; Maes, M.; Pasco, J.A.; Williams, L.J.; Berk, M. Nutrient intakes and the common mental disorders in women. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, U.E.; Beglinger, C.; Schweinfurth, N.; Walter, M.; Borgwardt, S. Nutritional aspects of depression. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 37, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.W.; Kim, Y.K. The role of neuroinflammation and neurovascular dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 11, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblat, J.D.; Cha, D.S.; Mansur, R.B.; McIntyre, R.S. Inflamed moods: A review of the interactions between inflammation and mood disorders. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, L.L.; Tizabi, Y. Neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and depression. Neurotox. Res. 2013, 23, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raison, C.L.; Miller, A.H. Role of inflammation in depression: Implications for phenomenology, pathophysiology and treatment. Mod. Trends Pharm. 2013, 28, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Maletic, V.; Raison, C.L. Inflammation and its discontents: The role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howren, M.B.; Lamkin, D.M.; Suls, J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: A meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlati, Y.; Herrmann, N.; Swardfager, W.; Liu, H.; Sham, L.; Reim, E.K.; Lanctot, K.L. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Xu, X.; Chen, G.; Mehta, N.D.; Haroon, E.; Miller, A.H.; Luo, Y.; Li, Z.; Felger, J.C. Inflammation and decreased functional connectivity in a widely-distributed network in depression: Centralized effects in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ho, R.C.; Mak, A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletic, V.; Raison, C. The New Mind-Body Science of Depression; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, J.; Petronis, A. Molecular studies of major depressive disorder: The epigenetic perspective. Mol. Psychiatry 2007, 12, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasca, C.; Xenos, D.; Barone, Y.; Caruso, A.; Scaccianoce, S.; Matrisciano, F.; Battaglia, G.; Mathe, A.A.; Pittaluga, A.; Lionetto, L.; et al. L-acetylcarnitine causes rapid antidepressant effects through the epigenetic induction of mGlu2 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4804–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, E.J. Epigenetic mechanisms of depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, C.J.; Nestler, E.J. Progress in epigenetics of depression. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2018, 157, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottiglieri, T. Folate, vitamin B(1)(2), and S-adenosylmethionine. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.M. Effects of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency on brain development in children. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008, 29, S126–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanri, A.; Hayabuchi, H.; Ohta, M.; Sato, M.; Mishima, N.; Mizoue, T. Serum folate and depressive symptoms among Japanese men and women: A cross-sectional and prospective study. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 200, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbody, S.; Lightfoot, T.; Sheldon, T. Is low folate a risk factor for depression? A meta-analysis and exploration of heterogeneity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Derry, H.M.; Fagundes, C.P. Inflammation: Depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopschina Feltes, P.; Doorduin, J.; Klein, H.C.; Juarez-Orozco, L.E.; Dierckx, R.A.; Moriguchi-Jeckel, C.M.; de Vries, E.F. Anti-inflammatory treatment for major depressive disorder: Implications for patients with an elevated immune profile and non-responders to standard antidepressant therapy. J. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 31, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.H.; Haroon, E.; Raison, C.L.; Felger, J.C. Cytokine targets in the brain: Impact on neurotransmitters and neurocircuits. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, J.E.; Fava, M. Nutrition and depression: The role of folate. Nutr. Rev. 1997, 55, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. L-methylfolate: A vitamin for your monoamines. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 1352–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzik, K.; Bailey, L.; Shane, B. Folic acid and L-5-methyltetrahydrofolate: Comparison of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010, 49, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottiglieri, T. Homocysteine and folate metabolism in depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 29, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, O.; Giorlando, F.; Berk, M. N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry: Current therapeutic evidence and potential mechanisms of action. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011, 36, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, G.R.; Kapczinski, F. N-acetylcysteine as a mitochondrial enhancer: A new class of psychoactive drugs? Braz. J. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Budni, J.; Zomkowski, A.D.; Engel, D.; Santos, D.B.; dos Santos, A.A.; Moretti, M.; Valvassori, S.S.; Ornell, F.; Quevedo, J.; Farina, M.; et al. Folic acid prevents depressive-like behavior and hippocampal antioxidant imbalance induced by restraint stress in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 240, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakostas, G.I.; Shelton, R.C.; Zajecka, J.M.; Etemad, B.; Rickels, K.; Clain, A.; Baer, L.; Dalton, E.D.; Sacco, G.R.; Schoenfeld, D.; et al. L-methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for SSRI-resistant major depression: Results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential trials. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deplin Capsules [Package Insert]; Alfasigma USA, Inc.: Covington, LA, USA, 2017.

- Papakostas, G.I.; Shelton, R.C.; Zajecka, J.M.; Bottiglieri, T.; Roffman, J.; Cassiello, C.; Stahl, S.M.; Fava, M. Effect of adjunctive L-methylfolate 15 mg among inadequate responders to SSRIs in depressed patients who were stratified by biomarker levels and genotype: Results from a randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, R.C.; Pencina, M.J.; Barrentine, L.W.; Ruiz, J.A.; Fava, M.; Zajecka, J.M.; Papakostas, G.I. Association of obesity and inflammatory marker levels on treatment outcome: Results from a double-blind, randomized study of adjunctive L-methylfolate calcium in patients with MDD who are inadequate responders to SSRIs. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, L.D.; Oubre, A.Y.; Daoud, Y.A. L-methylfolate Plus SSRI or SNRI from Treatment Initiation Compared to SSRI or SNRI Monotherapy in a Major Depressive Episode. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 8, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Papakostas, G.I.; Mischoulon, D.; Shyu, I.; Alpert, J.E.; Fava, M. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder: A double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.L.; Girard, C.; Jui, D.; Sabina, A.; Katz, D.L. S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) as treatment for depression: A systematic review. Clin. Investig. Med. Med. Clin. Exp. 2005, 28, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Galizia, I.; Oldani, L.; Macritchie, K.; Amari, E.; Dougall, D.; Jones, T.N.; Lam, R.W.; Massei, G.J.; Yatham, L.N.; Young, A.H. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10, Cd011286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasca, C.; Bigio, B.; Lee, F.S.; Young, S.P.; Kautz, M.M.; Albright, A.; Beasley, J.; Millington, D.S.; Mathe, A.A.; Kocsis, J.H.; et al. Acetyl-l-carnitine deficiency in patients with major depressive disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8627–8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Ajnakina, O.; Carvalho, A.F.; Maggi, S. Acetyl-L-carnitine supplementation and the treatment of depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2018, 80, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, B.P.; Jensen, J.E.; Hudson, J.I.; Coit, C.E.; Beaulieu, A.; Pope, H.G., Jr.; Renshaw, P.F.; Cohen, B.M. A placebo-controlled trial of acetyl-L-carnitine and alpha-lipoic acid in the treatment of bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, Q.E.; Cai, D.B.; Yang, X.H.; Qiu, Y.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Berk, M.; Ning, Y.P.; Xiang, Y.T. N-acetylcysteine for major mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 137, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.S.; Dean, O.M.; Dodd, S.; Malhi, G.S.; Berk, M. N-Acetylcysteine in depressive symptoms and functionality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, e457–e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk, M.; Dean, O.M.; Cotton, S.M.; Jeavons, S.; Tanious, M.; Kohlmann, K.; Hewitt, K.; Moss, K.; Allwang, C.; Schapkaitz, I.; et al. The efficacy of adjunctive N-acetylcysteine in major depressive disorder: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhaes, P.V.; Dean, O.M.; Bush, A.I.; Copolov, D.L.; Malhi, G.S.; Kohlmann, K.; Jeavons, S.; Schapkaitz, I.; Anderson-Hunt, M.; Berk, M. N-acetylcysteine for major depressive episodes in bipolar disorder. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwek, M.; Dudek, D.; Schlegel-Zawadzka, M.; Morawska, A.; Piekoszewski, W.; Opoka, W.; Zieba, A.; Pilc, A.; Popik, P.; Nowak, G. Serum zinc level in depressed patients during zinc supplementation of imipramine treatment. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 126, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maserejian, N.N.; Hall, S.A.; McKinlay, J.B. Low dietary or supplemental zinc is associated with depression symptoms among women, but not men, in a population-based epidemiological survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swardfager, W.; Herrmann, N.; Mazereeuw, G.; Goldberger, K.; Harimoto, T.; Lanctot, K.L. Zinc in depression: A meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarleton, E.K.; Littenberg, B.; MacLean, C.D.; Kennedy, A.G.; Daley, C. Role of magnesium supplementation in the treatment of depression: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spedding, S. Vitamin D and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing studies with and without biological flaws. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1501–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.B.; McDonnell, A.P.; Johnston, T.G.; Mulholland, C.; Cooper, S.J.; McMaster, D.; Evans, A.; Whitehead, A.S. The MTHFR C677T polymorphism is associated with depressive episodes in patients from Northern Ireland. J. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 18, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, A.; Bockting, C.L.; Koeter, M.W.; Snieder, H.; Assies, J.; Mocking, R.J.; Vinkers, C.H.; Kahn, R.S.; Boks, M.P.; Schene, A.H. Interaction between the MTHFR C677T polymorphism and traumatic childhood events predicts depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Ding, X.X.; Sun, Y.H.; Yang, H.Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y.H.; Lv, X.L.; Wu, Z.Q. Association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and depression: An updated meta-analysis of 26 studies. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 46, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, R.C.; Sloan Manning, J.; Barrentine, L.W.; Tipa, E.V. Assessing Effects of l-Methylfolate in Depression Management: Results of a Real-World Patient Experience Trial. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartois, L.L.; Stutzman, D.L.; Morrow, M. L-methylfolate Augmentation to Antidepressants for Adolescents with Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Case Series. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainka, M.; Aladeen, T.; Westphal, E.; Meaney, J.; Gengo, F.; Greger, J.; Capote, H. L-methylfolate calcium supplementation in adolescents and children: A retrospective analysis. J. Psychiatry Pract. 2019, 25, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeier, Z.; Carpenter, L.L.; Kalin, N.H.; Rodriguez, C.I.; McDonald, W.M.; Widge, A.S.; Nemeroff, C.B. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenetic decision support tools for antidepressant drug prescribing. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poddar, R.; Sivasubramanian, N.; DiBello, P.M.; Robinson, K.; Jacobsen, D.W. Homocysteine induces expression and secretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and interleukin-8 in human aortic endothelial cells: Implications for vascular disease. Circulation 2001, 103, 2717–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.; Liu, T.; Peter, I.; Buell, J.; Arsenault, L.; Scott, T.; Qiu, W.W. The homocysteine hypothesis of depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.; Smith, A.D.; Jobst, K.A.; Refsum, H.; Sutton, L.; Ueland, P.M. Folate, vitamin B12, and serum total homocysteine levels in confirmed Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 1998, 55, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Arora, R.; Bansal, A.K.; Bhattacharya, R.; Sharma, G.S.; Singh, L.R. Disturbed homocysteine metabolism is associated with cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacek, T.P.; Kalani, A.; Voor, M.J.; Tyagi, S.C.; Tyagi, N. The role of homocysteine in bone remodeling. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013, 51, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedro, B. Homocysteine (Blood Test). Available online: https://www.emedicinehealth.com/homocysteine/article_em.htm (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Beard, R.S., Jr.; Reynolds, J.J.; Bearden, S.E. Hyperhomocysteinemia increases permeability of the blood-brain barrier by NMDA receptor-dependent regulation of adherens and tight junctions. Blood 2011, 118, 2007–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.H.; Chiou, H.Y.; Chen, Y.H. Associations between serum homocysteine levels and anxiety and depression among children and adolescents in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, I.; Tell, G.S.; Vollset, S.E.; Refsum, H.; Ueland, P.M. Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and the MTHFR 677C->T polymorphism in anxiety and depression: The Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariballa, S. Testing homocysteine-induced neurotransmitter deficiency, and depression of mood hypothesis in clinical practice. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permoda-Osip, A.; Kisielewski, J.; Dorszewska, J.; Rybakowski, J. Homocysteine and cognitive functions in bipolar depression. Psychiatr. Pol. 2014, 48, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klee, G.G. Cobalamin and folate evaluation: Measurement of methylmalonic acid and homocysteine vs. vitamin B(12) and folate. Clin. Chem. 2000, 46, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Gerbarg, P.; Bottiglieri, T.; Massoumi, L.; Carpenter, L.L.; Lavretsky, H.; Muskin, P.R.; Brown, R.P.; Mischoulon, D. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Clinician-Oriented Review of Research. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, e656–e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelenberg, A.J.; Freeman, M.P.; Markowitz, J.C.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Thase, M.E.; Trivedi, M.H.; Van Rhoads, R.S. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Available online: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2015).

- Mischoulon, D.; Fava, M. Role of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in the treatment of depression: A review of the evidence. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 1158s–1161s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakostas, G.I.; Cassiello, C.F.; Iovieno, N. Folates and S-adenosylmethionine for major depressive disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menke, A.; Binder, E.B. Epigenetic alterations in depression and antidepressant treatment. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 16, 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, G.C.; McKenna, M.C. L-Carnitine and Acetyl-L-carnitine Roles and Neuroprotection in Developing Brain. Neurochem Res 2017, 42, 1661–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soczynska, J.K.; Kennedy, S.H.; Chow, C.S.; Woldeyohannes, H.O.; Konarski, J.Z.; McIntyre, R.S. Acetyl-L-carnitine and alpha-lipoic acid: Possible neurotherapeutic agents for mood disorders? Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2008, 17, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Lu, Y.; Xue, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Chen, X.; Cui, W.; et al. Rapid-acting antidepressant-like effects of acetyl-l-carnitine mediated by PI3K/AKT/BDNF/VGF signaling pathway in mice. Neuroscience 2015, 285, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, K.P.; Moreau, R.F.; Smith, E.J.; Smith, A.R.; Hagen, T.M. Alpha-lipoic acid as a dietary supplement: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1790, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilgun-Sherki, Y.; Melamed, E.; Offen, D. Oxidative stress induced-neurodegenerative diseases: The need for antioxidants that penetrate the blood brain barrier. Neuropharmacology 2001, 40, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, L.; Witt, E.H.; Tritschler, H.J. Alpha-Lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcell, S. Sulfur in human nutrition and applications in medicine. Altern. Med. Rev. 2002, 7, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Etherton, T.D.; Martin, K.R.; Gillies, P.J.; West, S.G.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, P.; Wu, N.; He, B.; Lu, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, L.; Li, Y. Amelioration of lipid abnormalities by alpha-lipoic acid through antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. Obesity 2011, 19, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sola, S.; Mir, M.Q.; Cheema, F.A.; Khan-Merchant, N.; Menon, R.G.; Parthasarathy, S.; Khan, B.V. Irbesartan and lipoic acid improve endothelial function and reduce markers of inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: Results of the Irbesartan and Lipoic Acid in Endothelial Dysfunction (ISLAND) study. Circulation 2005, 111, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.C.; de Sousa, C.N.; Sampaio, L.R.; Ximenes, N.C.; Araujo, P.V.; da Silva, J.C.; de Oliveira, S.L.; Sousa, F.C.; Macedo, D.S.; Vasconcelos, S.M. Augmentation therapy with alpha-lipoic acid and desvenlafaxine: A future target for treatment of depression? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2013, 386, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliev, G.; Liu, J.; Shenk, J.C.; Fischbach, K.; Pacheco, G.J.; Chen, S.G.; Obrenovich, M.E.; Ward, W.F.; Richardson, A.G.; Smith, M.A.; et al. Neuronal mitochondrial amelioration by feeding acetyl-L-carnitine and lipoic acid to aged rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Head, E.; Gharib, A.M.; Yuan, W.; Ingersoll, R.T.; Hagen, T.M.; Cotman, C.W.; Ames, B.N. Memory loss in old rats is associated with brain mitochondrial decay and RNA/DNA oxidation: Partial reversal by feeding acetyl-L-carnitine and/or R-alpha -lipoic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 2356–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, T.M.; Liu, J.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Wehr, C.M.; Ingersoll, R.T.; Vinarsky, V.; Bartholomew, J.C.; Ames, B.N. Feeding acetyl-L-carnitine and lipoic acid to old rats significantly improves metabolic function while decreasing oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 1870–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, C.; Rizzo, L.B.; Mansur, R.B.; McIntyre, R.S.; Maes, M.; Brietzke, E. Targeting the inflammatory pathway as a therapeutic tool for major depression. Neuroimmunomodulation 2014, 21, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepmala; Slattery, J.; Kumar, N.; Delhey, L.; Berk, M.; Dean, O.; Spielholz, C.; Frye, R. Clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry and neurology: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 55, 294–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.A.; Hansen, K.; Banks, W.A. Inflammation-induced dysfunction of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier: Protection by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, S.L.; Green, R.; Pak, S.C. N-Acetylcysteine for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: A Review of Current Evidence. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2469486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigner, P.; Czarny, P.; Galecki, P.; Sliwinski, T. Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress as Well as the Tryptophan Catabolites Pathway in Depressive Disorders. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, A.M.; Kim, Y.K.; Verkerk, R.; Scharpe, S.; Steinbusch, H.; Leonard, B. Kynurenine pathway in major depression: Evidence of impaired neuroprotection. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 98, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.N.; Leyton, M. The role of serotonin in human mood and social interaction. Insight from altered tryptophan levels. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002, 71, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.A.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Heninger, G.R.; Potter, R.L.; McKnight, K.M.; Allen, J.; Phillips, A.P.; Delgado, P.L. Tryptophan depletion and depressive vulnerability. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyton, M.; Ghadirian, A.M.; Young, S.N.; Palmour, R.M.; Blier, P.; Helmers, K.F.; Benkelfat, C. Depressive relapse following acute tryptophan depletion in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Psychopharmacol. 2000, 14, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, M.; Meltzer, H.Y.; Scharpe, S.; Bosmans, E.; Suy, E.; De Meester, I.; Calabrese, J.; Cosyns, P. Relationships between lower plasma L-tryptophan levels and immune-inflammatory variables in depression. Psychiatry Res. 1993, 49, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.; Kubera, M.; Duda, W.; Lason, W.; Berk, M.; Maes, M. Increased IL-6 trans-signaling in depression: Focus on the tryptophan catabolite pathway, melatonin and neuroprogression. Pharmacol. Rep. 2013, 65, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernstrom, J.D. Effects and side effects associated with the non-nutritional use of tryptophan by humans. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 2236s–2244s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindseth, G.; Helland, B.; Caspers, J. The effects of dietary tryptophan on affective disorders. Arch. Psychiatry Nurs. 2015, 29, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong, A.L.; Patel, T.; Kellar, J.; Grindrod, K.A. The scoop on serotonin syndrome. Can. Pharm. J. 2018, 151, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Um, P.; Dickerman, B.A.; Liu, J. Zinc, Magnesium, Selenium and Depression: A Review of the Evidence, Potential Mechanisms and Implications. Nutrients 2018, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styczen, K.; Sowa-Kucma, M.; Siwek, M.; Dudek, D.; Reczynski, W.; Szewczyk, B.; Misztak, P.; Topor-Madry, R.; Opoka, W.; Nowak, G. The serum zinc concentration as a potential biological marker in patients with major depressive disorder. Metab. Brain Dis. 2017, 32, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlyniec, K. Zinc in the Glutamatergic Theory of Depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015, 13, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swardfager, W.; Herrmann, N.; McIntyre, R.S.; Mazereeuw, G.; Goldberger, K.; Cha, D.S.; Schwartz, Y.; Lanctot, K.L. Potential roles of zinc in the pathophysiology and treatment of major depressive disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 911–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, A.; Tamano, H.; Nishio, R.; Murakami, T. Behavioral Abnormality Induced by Enhanced Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis Activity under Dietary Zinc Deficiency and Its Usefulness as a Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serefko, A.; Szopa, A.; Wlaz, P.; Nowak, G.; Radziwon-Zaleska, M.; Skalski, M.; Poleszak, E. Magnesium in depression. Pharmacol. Rep. 2013, 65, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, J.M.; Dalessandri, K.M.; Pope, K.; Hernandez, G.T. Low 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Myofascial Pain: Association of Cancer, Colon Polyps, and Tendon Rupture. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.W.; Silverstein, F.S.; Johnston, M.V. Magnesium reduces N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-mediated brain injury in perinatal rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1990, 109, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, C.A., Jr.; Mathews, D.C.; Furey, M.L. Human biomarkers of rapid antidepressant effects. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarleton, E.K.; Littenberg, B. Magnesium intake and depression in adults. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2015, 28, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eby, G.A.; Eby, K.L. Rapid recovery from major depression using magnesium treatment. Med. Hypotheses 2006, 67, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poleszak, E.; Szewczyk, B.; Kedzierska, E.; Wlaz, P.; Pilc, A.; Nowak, G. Antidepressant- and anxiolytic-like activity of magnesium in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004, 78, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poleszak, E.; Wlaz, P.; Kedzierska, E.; Radziwon-Zaleska, M.; Pilc, A.; Fidecka, S.; Nowak, G. Effects of acute and chronic treatment with magnesium in the forced swim test in rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 2005, 57, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ganji, V.; Milone, C.; Cody, M.M.; McCarty, F.; Wang, Y.T. Serum vitamin D concentrations are related to depression in young adult US population: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. Arch. Med. 2010, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniack, E.P.; Troen, B.R.; Florez, H.J.; Roos, B.A.; Levis, S. Some new food for thought: The role of vitamin D in the mental health of older adults. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anglin, R.E.; Samaan, Z.; Walter, S.D.; McDonald, S.D. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Vitamin D and the occurrence of depression: Causal association or circumstantial evidence? Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C.H.; Sheline, Y.I.; Roe, C.M.; Birge, S.J.; Morris, J.C. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Hoogendijk, W.; Lips, P.; Heijboer, A.C.; Schoevers, R.; van Hemert, A.M.; Beekman, A.T.; Smit, J.H.; Penninx, B.W. The association between low vitamin D and depressive disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Shao, A.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Hathcock, J.; Giovannucci, E.; Willett, W.C. Benefit-risk assessment of vitamin D supplementation. Osteoporos. Int. 2010, 21, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieth, R. Vitamin D toxicity, policy, and science. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007, 22 (Suppl. S2), V64–V68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, M.; Stokes, C. Omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Drugs 2005, 65, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.L.; Bhat, S.A.; Ara, A. Omega-3 fatty acids and the treatment of depression: A review of scientific evidence. Integr. Med. Res. 2015, 4, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Begg, D.; Mathai, M.; Weisinger, R.S. Omega 3 fatty acids and the brain: Review of studies in depression. Asia Pac J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 16 (Suppl. S1), 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Grosso, G.; Galvano, F.; Marventano, S.; Malaguarnera, M.; Bucolo, C.; Drago, F.; Caraci, F. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: Scientific evidence and biological mechanisms. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 313570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrousse, V.F.; Nadjar, A.; Joffre, C.; Costes, L.; Aubert, A.; Gregoire, S.; Bretillon, L.; Laye, S. Short-term long chain omega3 diet protects from neuroinflammatory processes and memory impairment in aged mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrieu, T.; Laye, S. Food for Mood: Relevance of Nutritional Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Depression and Anxiety. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, R.K.; Jandacek, R.; Rider, T.; Tso, P.; Cole-Strauss, A.; Lipton, J.W. Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency increases constitutive pro-inflammatory cytokine production in rats: Relationship with central serotonin turnover. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2010, 83, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feart, C.; Peuchant, E.; Letenneur, L.; Samieri, C.; Montagnier, D.; Fourrier-Reglat, A.; Barberger-Gateau, P. Plasma eicosapentaenoic acid is inversely associated with severity of depressive symptomatology in the elderly: Data from the Bordeaux sample of the Three-City Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.; Peet, M.; Shay, J.; Horrobin, D. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid levels in the diet and in red blood cell membranes of depressed patients. J. Affect. Disord. 1998, 48, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, M.H.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Schettler, P.J.; Kinkead, B.; Cardoos, A.; Walker, R.; Mischoulon, D. Inflammation as a predictive biomarker for response to omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder: A proof-of-concept study. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, K.H.O.; Jimoh, O.F.; Biswas, P.; O’Brien, A.; Hanson, S.; Abdelhamid, A.S.; Fox, C.; Hooper, L. Omega-3 and polyunsaturated fat for prevention of depression and anxiety symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, M.; Mihaylova, I.; Kubera, M.; Uytterhoeven, M.; Vrydags, N.; Bosmans, E. Lower plasma Coenzyme Q10 in depression: A marker for treatment resistance and chronic fatigue in depression and a risk factor to cardiovascular disorder in that illness. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. 2009, 30, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.; Anderson, G.; Berk, M.; Maes, M. Coenzyme Q10 depletion in medical and neuropsychiatric disorders: Potential repercussions and therapeutic implications. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 48, 883–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, B.P.; Harper, D.G.; Georgakas, J.; Ravichandran, C.; Madurai, N.; Cohen, B.M. Antidepressant effects of open label treatment with coenzyme Q10 in geriatric bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 35, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Design | Size | Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-methylfolate | ||||

| Ginsberg et al. 2011. [46] | Retrospective analysis of L-methylfolate as adjunctive therapy to SSRI/SNRI in patients with MDD | 242 patients | L-methylfolate in addition to SSRI/SNRI therapy was superior to SSRI/SNRI monotherapy in improving depressive symptoms and functions (CGI severity reduction ≥ 2: 19% vs. 7%; p = 0.01) within 60 days | There were no major differences in adverse events between the two groups. The most commonly reported adverse events included sexual dysfunction, somnolence, nausea, dizziness, insomnia, agitation, constipation, and fatigue. |

| Papakostas et al. 2012. [42] | Two randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential trials Trial 1: Patients with SSRI-resistant MDD were randomized to placebo or L- methylfolate 7.5 mg/day for 60 days, or placebo for 30 days and then L- methylfolate as adjunctive to SSRIs Trial 2: Patients with SSRI-resistant MDD were randomized to placebo or L- methylfolate 15 mg/day for 60 days, or placebo for 30 days and then L- methylfolate as adjunctive to SSRIs | Trial 1: 148 patients Trial 2: 75 patients | In Trial 1, 7.5 mg adjunctive L-methylfolate was not superior to placebo; however, Trial 2 demonstrated that L-methylfolate 15 mg was associated with a higher response rate than placebo (32% vs. 15%; p = 0.05) and significant improvement on the QIDS-SR score and CGI severity scale. | Comparable side effect profile with placebo; most common side effect categories were gastrointestinal (17%), somatic (14%), and infectious (11%) |

| Papakostas et al. 2014. [44] | Post hoc analysis of Papakostas et al. 2012. | 74 patients | Patients with genetic markers at baseline showed a greater mean change from baseline on the 28-item HAM-D (p < 0.05) and response rate (p < 0.05) with L-methylfolate compared with placebo. Genetic markers with the greatest mean change from baseline were MTHFR 677 CT/TT + MTR 2756 AG/GG, GCH1TC/TT + COMT GG, and GCH1 TC/TT + COMT CC. | N/A |

| Shelton et al. 2015. [45] | Exploratory, post-hoc analysis of Papakostas et al. 2012. | 74 patients | Significant changes in mean change on the 17-item HAM-D were reported with L-methylfolate versus placebo (p < 0.05) for those with greater than median baseline levels of TNF-α, IL-8, hsCRP, and leptin. Patients with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 with TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, hsCRP, and leptin had statistically significant treatment effects versus placebo (p ≤ 0.05). | N/A |

| S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) | ||||

| Papakostas et al. 2010. [47] | Single-center, randomized, double-blind study of SAMe augmentation of SRIs in nonresponding patients with MDD | 73 patients | Four patients discontinued placebo and two discontinued SAMe due to inefficacy. Based on HAM-D scores, 18 patients in the SAMe group responded and 14 remitted, compared with 6 patients in the placebo group who responded and 4 who remitted (p = 0.01, and p = 0.02, respectively). Based on CGI ratings, remission and response rates were greater in SAMe-treated patients versus placebo-treated patients. | Three placebo and two SAMe patients discontinued treatment due to intolerance of treatment. No statistically significant differences in adverse events were reported, although there was a marginally higher mean supine systolic blood pressure reading in the SAMe arm (mean difference 3.1 mm Hg). No serious adverse events were reported. |

| Williams et al. 2005. [48] | Systematic review of studies, reviews, case reports, and pilot projects investigating SAMe in depression among humans | 11 studies (5 intervention trials, 2 randomized clinical trials, 2 reviews, 1 controlled clinical trial, 1 meta-analysis) | All intervention studies and randomized trials favored oral SAMe to placebo and had significant effect on the HAM-D. | N/A |

| Galizia et al. 2016. [49] | A Cochrane systematic review conducted to investigate SAMe as monotherapy and adjunctive in the treatment of MDD in adults | 8 clinical trials comparing SAMe with placebo, imipramine, desipramine, or escitalopram in 934 adults | Overall, there was low quality evidence. Based on change from baseline in HAM-D and MADRS score, there was no strong evidence of a difference between the SAMe and placebo groups (SMD −0.54, 95% CI −1.54 to 0.46, p = 0.29), along with SAMe and escitalopram (MD 0.12, 95% CI −2.75 to 2.99, p = 0.93). Low quality evidence suggested comparable change in depressive symptoms between SAMe and imipramine monotherapy (SMD −0.04, 95% CI, −0.34 to 0.27; p = 0.82). Additionally, low quality evidence showed that SAMe was superior to placebo as adjunctive treatment to SSRIs (MD −3.90, 95% CI −6.93 to −0.87, p = 0.01). | 2 incidences of mania/hypomania of 441 participants receiving SAMe |

| L-acetylcarnitine (LAC) | ||||

| Nasca et al. 2018. [50] | Translational study of evaluating the role of LAC in MDD | 116 participants | Mean concentration of LAC in patients with MDD were significantly lower than that of healthy controls (6.1 μmol/L ± 0.3 vs. 8.3 μmol/L ± 0.4, respectively; p < 0.0001). There was an inverse correlation between severity of MDD based on 17-item HAM-D scores and ALCAR concentrations (p = 0.04, r = 0.35). LAC also was shown to be predictive of moderate to severe MDD (p = 0.04). Furthermore, earlier age of onset of depression correlated with lower concentration of LAC (p = 0.04). Additionally, patients with MDD and a history of TRD were associated with a decrease in LAC levels. | N/A |

| Veronese et al. 2018. [51] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials | 393 patients who received LAC and 398 controls | Administration of LAC was associated with a significant reduction of depressive symptoms using various outcomes with an emphasis on the HAM-D compared with controls (SMD −1.10; 95% CI −1.65 to −0.56; p < 0.001), although there was some evidence of publication bias (Egger test, −6.69 ± 2.65; p = 0.040). Higher LAC doses resulted in better test results when assessing depressive symptoms (p = 0.01). LAC showed a similar effect on treating depressive symptoms compared with conventional antidepressants (SMD 0.06; 95% CI −0.22 to 0.34; p = 0.686) | Patients receiving LAC had a similar frequency of adverse effects compared with those on placebo, but showed a 79% reduction in adverse effects when compared with antidepressants (OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.12–0.36; p < 0.001) |

| Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) | ||||

| Brennan et al. 2013. [52] | A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of LAC and ALA versus placebo as augmentation treatment in those with inadequate response to standard treatments for bipolar depression | 68 participants | There were no significant differences in mean MADRS score found between LAC/ALA and placebo. | Most frequently reported adverse events were diarrhea (30%), foul-smelling urine (25%), rash (20%), constipation (15%), and dyspepsia (15%) |

| N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | ||||

| Zheng et al. 2018. [53] | Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of NAC vs. placebo in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or MDD | Schizophrenia: 3 trials, n = 307 Bipolar disorder: 2 trials, n = 125 MDD: 1 trial, n = 269 | In patients with MDD, there were no significant differences in clinical efficacy between add-on NAC and placebo based on the MADRS. | Patients in the NAC group experienced more gastrointestinal (33.9% vs. 18.4%; p = 0.005) and musculoskeletal (3.9% vs. 0%; p = 0.025) compared with placebo |

| Fernandes et al. 2016. [54] | A meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized controlled trials of NAC compared to placebo | 5 studies; 574 participants | Adjunctive NAC resulted in moderate improvement in MADRS and HAM-D scores (SMD 0.37; 95% CI 0.19–0.55; p < 0.001), but consistently better scores on the CGI-S at follow-up compared with placebo (SMD 0.22; 95% CI 0.03–0.41; p < 0.001). | Incidences of severe adverse events were similar between placebo and NAC groups (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.43–2.51; p = 0.920). NAC was associated with an increase in minor adverse events (OR 1.61; 95% CI 1.01–2.59; p = 0.049). Frequently reported minor adverse events were gastrointestinal issues such as nausea and heartburn, and musculoskeletal issues such as back and joint pain. |

| Berk et al. 2014. [55] | A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing adjunctive NAC with placebo in the acute treatment of moderate to severe MDD | 252 participants | Over the course of the study, NAC-treated and placebo-treated patients had similar MADRS scores; however, at week 16, there was significantly greater response in the NAC group than placebo (36.6% vs. 25.0%, respectively; p = 0.027). There was a higher likelihood of reaching remission with NAC than with placebo (17.9% vs. 6.2%, respectively; p = 0.017). Furthermore, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the NAC-treated group had reduction of symptom severity (p = 0.001) and greater improvements in functioning (p = 0.001) than placebo. | N/A |

| Magalhaes et al. 2011. [56] | Secondary exploratory analysis of NAC in bipolar depression | 17 participants | Compared with placebo, NAC was associated with significant improvements in symptom severity, function, and quality of life. 80% of NAC-treated patients (n = 8) had a 50% reduction in MADRS scores compared with 1 patient in the placebo group with the same outcome (OR 24, 95% CI 1.74–330.80, p = 0.015). | Side effects were minor and included headache, abdominal pain, and diarrhea |

| Zinc | ||||

| Siwek et al. 2010. [57] | Placebo-controlled, double-blind study of adjunctive zinc in patients receiving imipramine for MDD | 60 patients | Treatment-resistant patients demonstrated lower concentrations of zinc than treatment-non-resistant patients. Zinc levels were inversely correlated with MADRS score (p = 0.001). Patients who reached remission were found to have a significantly higher zinc level compared to those who had not reached remission. | N/A |

| Maserejian et al. 2012. [58] | An analysis of cross-sectional, observational epidemiological data from a population-based, random stratified cluster sample survey from 2002 through 2005 | 3708 patients | Among women with low dietary zinc intake, there was an 80% increased risk of having depressive symptoms (CES-D) compared to those with high dietary zinc intake (Ptrend = 0.004) a and those taking supplemental zinc had a lower probability of having depressive symptoms (Ptrend = 0.03). In women, the odds of ongoing depressive symptoms among SSRI users reduced by half (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.24–0.80, p = 0.007) in those with moderate-to-high zinc intake (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.28–3.28, p = 0.003), compared to those with low zinc intake <12.8 mg/day (OR 4.01, 95% CI 2.56–6.29, p < 0.0001). | N/A |

| Swardfager et al. 2013. [59] | A meta-analysis of zinc concentrations in depression | 23 studies | Mean peripheral blood zinc concentrations were 1.85 μmol/L lower in depressed patients versus controls (95% CI −2.51 to −1.19, p < 0.00001). In studies examining depressive symptom severity using numerous scales, greater mean depressive symptom severity was associated with greater differences in zinc between depressed patients and controls. | N/A |

| Magnesium | ||||

| Tarleton et al. 2017. [60] | Randomized, open-label, crossover study evaluating the effects of magnesium supplementation on symptom improvement in mild-to-moderate depression | 126 patients | Unadjusted PHQ-9 depression scores improved with magnesium supplementation (−4.3 points, 95% CI −5.0 to −3.6), with a net improvement of −4.2 points. Unadjusted GAD-7 anxiety scores also improved with magnesium (−3.9 points, 95% CI −4.7 to −3.1), with a net improvement in anxiety of −4.5 points. | The most common side effect was diarrhea, which was reported by 8 participants. |

| Vitamin D | ||||

| Spedding et al. 2014. [61] | A systematic review of vitamin D supplementation in depression | 15 articles | Of the 15 articles, two studies were identified to be without flaws, which showed a statistically significant positive effect of vitamin D in depression of 0.78 (CI 0.24 to 1.27). Among the studies with biological flaws, there was a statistically significant negative effect of vitamin D with an effect size of −1.1 (CI −0.7 to −1.5). Various ratings scales were used in these studies. | |

| Supplemental Agent | Considerations and Guidance |

|---|---|

| L-acetylcarnitine |

|

| Alpha-lipoic acid |

|

| CoQ10 |

|

| Folic acid/L-methylfolate |

|

| Homocysteine |

|

| Inositol |

|

| Iron (ferritin, total iron binding capacity) |

|

| L-tryptophan |

|

| Magnesium |

|

| NAC |

|

| Omega-3 fatty acids |

|

| SAMe |

|

| Vitamin B12 |

|

| Zinc |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoepner, C.T.; McIntyre, R.S.; Papakostas, G.I. Impact of Supplementation and Nutritional Interventions on Pathogenic Processes of Mood Disorders: A Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2021, 13, 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030767

Hoepner CT, McIntyre RS, Papakostas GI. Impact of Supplementation and Nutritional Interventions on Pathogenic Processes of Mood Disorders: A Review of the Evidence. Nutrients. 2021; 13(3):767. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030767

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoepner, Cara T., Roger S. McIntyre, and George I. Papakostas. 2021. "Impact of Supplementation and Nutritional Interventions on Pathogenic Processes of Mood Disorders: A Review of the Evidence" Nutrients 13, no. 3: 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030767

APA StyleHoepner, C. T., McIntyre, R. S., & Papakostas, G. I. (2021). Impact of Supplementation and Nutritional Interventions on Pathogenic Processes of Mood Disorders: A Review of the Evidence. Nutrients, 13(3), 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030767