Epigenome-Wide Study Identified Methylation Sites Associated with the Risk of Obesity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

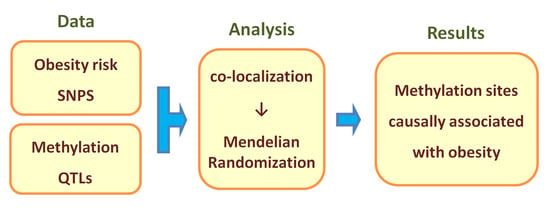

2. Methods

- (1)

- They must not be in LD. In this study, we used SNPs that were in linkage equilibrium (r2 < 0.05).

- (2)

- They must not show a pleiotropic effect (i.e., Exposure ← SNP→ Outcome). We excluded such SNPs from the instrument by using (PHEIDI < 0.01).

- (3)

- They must be significantly associated with exposure; we used SNPs that are associated with exposure at the GWAS significance level (p < 5 × 10−8).

3. Results

3.1. CCNL1 Locus

3.2. SLC5A11 Locus

3.3. MAST3 Locus

3.4. Rare Variants in 2p23.3

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ling, C.; Rönn, T. Epigenetics in human obesity and type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1028–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Low, F.M.; Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A. Epigenetic and Developmental Basis of Risk of Obesity and Metabolic Disease. In Cellular Endocrinology in Health and Disease, 2nd ed.; Ulloa-Aguirre, A., Tao, Y.-X., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; Chapter 14; pp. 289–313. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Su, S.; Barnes, V.A.; De Miguel, C.; Pollock, J.; Ownby, D.; Shi, H.; Zhu, H.; Snieder, H.; Wang, X. A genome-wide methylation study on obesity: Differential variability and differential methylation. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wahl, S.; Drong, A.; Lehne, B.; Loh, M.; Scott, W.R.; Kunze, S.; Tsai, P.-C.; Ried, J.S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y. Epigenome-wide association study of body mass index, and the adverse outcomes of adiposity. Nature 2017, 541, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koh, I.-U.; Choi, N.-H.; Lee, K.; Yu, H.-Y.; Yun, J.H.; Kong, J.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, B.-J.; et al. Obesity susceptible novel DNA methylation marker on regulatory region of inflammation gene: Results from the Korea Epigenome Study (KES). BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e001338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M.M.; Marioni, R.E.; Joehanes, R.; Liu, C.; Hedman, Å.K.; Aslibekyan, S.; Demerath, E.W.; Guan, W.; Zhi, D.; Yao, C. Association of body mass index with DNA methylation and gene expression in blood cells and relations to cardiometabolic disease: A Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.M.; Holmes, M.V.; Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 2018, 362, k601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nikpay, M.; McPherson, R. Convergence of biomarkers and risk factor trait loci of coronary artery disease at 3p21.31 and HLA region. npj Genom. Med. 2021, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikpay, M.; Soubeyrand, S.; Tahmasbi, R.; McPherson, R. Multiomics Screening Identifies Molecular Biomarkers Causally Associated with the Risk of Coronary Artery Disease. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, e002876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, A.F.; Marioni, R.E.; Shah, S.; Yang, J.; Powell, J.E.; Harris, S.E.; Gibson, J.; Henders, A.K.; Bowdler, L.; Painter, J.N.; et al. Identification of 55,000 Replicated DNA Methylation QTL. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pulit, S.L.; Stoneman, C.; Morris, A.P.; Wood, A.R.; Glastonbury, C.A.; Tyrrell, J.; Yengo, L.; Ferreira, T.; Marouli, E.; Ji, Y.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for body fat distribution in 694 649 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 28, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Hu, H.; Bakshi, A.; Robinson, M.R.; Powell, J.E.; Montgomery, G.W.; Goddard, M.E.; Wray, N.R.; Visscher, P.M.; et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Trzaskowski, M.; Maier, R.; Robinson, M.R.; McGrath, J.J.; Visscher, P.M.; Wray, N.R.; et al. Causal associations between risk factors and common diseases inferred from GWAS summary data. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hannon, E.; Gorrie-Stone, T.J.; Smart, M.C.; Burrage, J.; Hughes, A.; Bao, Y.; Kumari, M.; Schalkwyk, L.C.; Mill, J. Leveraging DNA-Methylation Quantitative-Trait Loci to Characterize the Relationship between Methylomic Variation, Gene Expression, and Complex Traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 103, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hannon, E.; Dempster, E.; Viana, J.; Burrage, J.; Smith, A.R.; Macdonald, R.; St Clair, D.; Mustard, C.; Breen, G.; Therman, S.; et al. An integrated genetic-epigenetic analysis of schizophrenia: Evidence for co-localization of genetic associations and differential DNA methylation. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Võsa, U.; Claringbould, A.; Westra, H.-J.; Bonder, M.J.; Deelen, P.; Zeng, B.; Kirsten, H.; Saha, A.; Kreuzhuber, R.; Kasela, S.; et al. Unraveling the polygenic architecture of complex traits using blood eQTL metaanalysis. bioRxiv 2018, 447367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landrum, M.J.; Chitipiralla, S.; Brown, G.R.; Chen, C.; Gu, B.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Jang, W.; Kaur, K.; Liu, C. ClinVar: Improvements to accessing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D835–D844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pividori, M.; Rajagopal, P.S.; Barbeira, A.; Liang, Y.; Melia, O.; Bastarache, L.; Park, Y.; Consortium, G.; Wen, X.; Im, H.K. PhenomeXcan: Mapping the genome to the phenome through the transcriptome. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpeläinen, T.O.; Carli, J.F.M.; Skowronski, A.A.; Sun, Q.; Kriebel, J.; Feitosa, M.F.; Hedman, Å.K.; Drong, A.W.; Hayes, J.E.; Zhao, J. Genome-wide meta-analysis uncovers novel loci influencing circulating leptin levels. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horikoshi, M.; Yaghootkar, H.; Mook-Kanamori, D.O.; Sovio, U.; Taal, H.R.; Hennig, B.J.; Bradfield, J.P.; Pourcain, B.S.; Evans, D.M.; Charoen, P. New loci associated with birth weight identify genetic links between intrauterine growth and adult height and metabolism. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, J.-Y.; Dus, M.; Kim, S.; Abu, F.; Kanai Makoto, I.; Rudy, B.; Suh Greg, S.B. Drosophila SLC5A11 Mediates Hunger by Regulating K+ Channel Activity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ugrankar, R.; Theodoropoulos, P.; Akdemir, F.; Henne, W.M.; Graff, J.M. Circulating glucose levels inversely correlate with Drosophila larval feeding through insulin signaling and SLC5A11. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garland, P.; Quraishe, S.; French, P.; O’Connor, V. Expression of the MAST family of serine/threonine kinases. Brain Res. 2008, 1195, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, E.; Christensen, K.R.; Bryant, E.; Schneider, A.; Rakotomamonjy, J.; Muir, A.M.; Giannelli, J.; Littlejohn, R.O.; Roeder, E.R.; Schmidt, B.; et al. Pathogenic MAST3 variants in the STK domain are associated with epilepsy. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikpay, M.; Beehler, K.; Valsesia, A.; Hager, J.; Harper, M.-E.; Dent, R.; McPherson, R. Genome-wide identification of circulating-miRNA expression quantitative trait loci reveals the role of several miRNAs in the regulation of cardiometabolic phenotypes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1629–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biomarker | PMID | Oucome | PMID | Beta | SE | P | NSNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg01884057 | 30514905 | POMC expression | bioRxiv 447367 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 1.7 × 10−37 | 5 |

| cg01884057 | 30401456 | POMC expression | bioRxiv 447367 | −1.90 | 0.15 | 3.6 × 10−37 | 4 |

| POMC expression | bioRxiv 447367 | BMI | 30239722 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 1.5 × 10−10 | 13 |

| cg01884057 | 30514905 | ADCY3 expression | bioRxiv 447367 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 4.3 × 10−20 | 12 |

| cg01884057 | 30401456 | ADCY3 expression | bioRxiv 447367 | −1.59 | 0.16 | 5.5 × 10−24 | 5 |

| ADCY3 expression | bioRxiv 447367 | BMI | 30239722 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 2.2 × 10−10 | 5 |

| cg01884057 | 30514905 | DNAJC27 expression | bioRxiv 447367 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 5.8 × 10−30 | 6 |

| cg01884057 | 30401456 | DNAJC27 expression | bioRxiv 447367 | −1.56 | 0.14 | 2.3 × 10−27 | 4 |

| DNAJC27 expression | bioRxiv 447367 | BMI | 30239722 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 2.7 × 10−10 | 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikpay, M.; Ravati, S.; Dent, R.; McPherson, R. Epigenome-Wide Study Identified Methylation Sites Associated with the Risk of Obesity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061984

Nikpay M, Ravati S, Dent R, McPherson R. Epigenome-Wide Study Identified Methylation Sites Associated with the Risk of Obesity. Nutrients. 2021; 13(6):1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061984

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikpay, Majid, Sepehr Ravati, Robert Dent, and Ruth McPherson. 2021. "Epigenome-Wide Study Identified Methylation Sites Associated with the Risk of Obesity" Nutrients 13, no. 6: 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061984

APA StyleNikpay, M., Ravati, S., Dent, R., & McPherson, R. (2021). Epigenome-Wide Study Identified Methylation Sites Associated with the Risk of Obesity. Nutrients, 13(6), 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061984