1. Introduction

Otitis media with effusion (OME), also called otitis media serosa, oto-tubaritis or otitis media with chronic exudate, is a chronic inflammation of the middle ear characterized by the presence of fluid buildup in the middle ear space in the absence of acute inflammation [

1,

2]. It is a very common disease in childhood, with 80% of children being considered to have experienced it at some point by the age of four. Among three year olds, its prevalence is estimated to range between 10% and 30%. Its most common symptom is mild hearing loss, which goes unnoticed by parents and is not easy to for paediatricians to detect in the absence of tympanometry devices [

3,

4]. Otoscopy can make an approximation to the diagnosis. However, otoscopy is not sensitive enough to detect many cases of OME [

5]. It is controversial whether prolonged hearing loss in early childhood—a critical age for language acqisition—negatively influences a child’s educational development.

Although OME has a benign evolution, and a high percentage of spontaneous healing, treatment is generally aggressive, with a tendency to long-term use of drugs and to surgical intervention. The effectiveness of drug treatment, which includes the use of decongestants, antihistamines, oral and intra-nasal corticosteroids and antibiotics is limited, with few clinical benefits and an increase in side effects [

6]. Self-insorwing techniques with insufficient results have also been described [

7]. The American Academy of Paediatrics recommends monitoring these children; if the duration of the thundering is longer than three months and hearing loss is greater than 40 dB, the introduction of ventilation tubes is recommended [

8]. Surgical treatment options include insertion of a tympanic drain, myringotomy and adenoidectomy. The benefits of surgical treatment are questioned by two systematic reviews, as hearing difficulties usually disappear spontaneously over time and levels of language and general development are equal in children with, or without, ventilation tubes [

9,

10,

11]. We have found very few articles in the literature that link diet to the development of OME. According to the research we have been developing, a significant reduction in upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), acute otitis media (AOM) and persistent nasal obstruction, has been observed when children followed a high-quality diet [

12,

13]. The objective of this study was to assess the effects of the traditional Mediterranean diet (TMD) on the evolution of otitis media with effusion.

3. Results

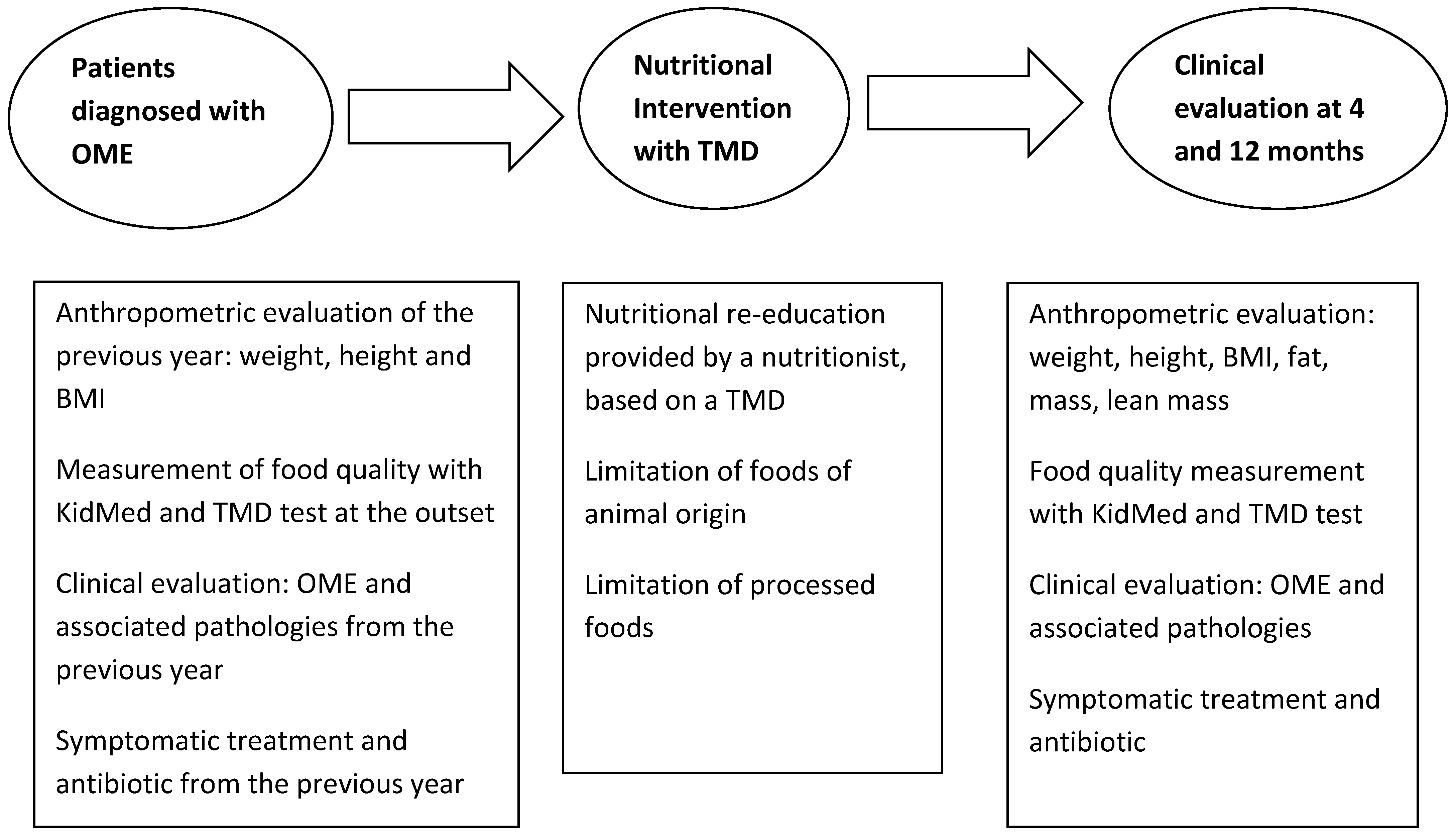

Participation was proposed in a program called ‘Learning to eat from the Mediterranean’. The families of 93 patients met the OME inclusion criteria. Seven refused to participate. Form the 86 patients included, six left the program after the first sessions. Two weree due to social or personal difficulties in implementing the diet, one was due to disagreement with limitations of certain foods and three due to surgical interventions indicated by the OR service and not coordinated with our team. The study was thus completed with a total of 80 patients (40 girls and 40 boys) with an average age of 3.1 years. All patients included in the study were evaluated at four and 12 months after the initial visit. The results obtained were similar in both sexes, and are thus, collated together (

Table 4).

During the treatment year, there was a normalization of tympanometry and therefore a reduction in the number of patients affected by OME to 85% of total participants, while the remaining 15% had improved hearing and/or associated symptoms. The number of URI and bacterial complications also decreased (

Table 5).

The level of household satisfaction was high, as shown in the questionnaire on observed improvements (

Table 1). Anthropometric variables before, at four months and after intervention, are set out in

Table 6. There was an adequate, statistically significant increase in determining parameters of growth and development, such as size and lean mass. The average weight increase in the year prior to the study was 2.01 kg, compared to 2.45 kg post-intervention, and the average size increase was 6.6 cm, compared with 7.30 cm post-intervention. Body mass index (BMI) decreased. The lean mass area of the arm increased, while the area of fat mass decreased.

At the end of the program, patients’ dietary habits had also improved in the sample as a whole, with an increase observed in the number of patients consuming fruits, vegetables, fish, whole grains and fermented dairy. Additionally, the percentage of patients who did not eat breakfast or who had industrial breakfast pastries decreased, as did the proportion of those who consumed treats on a daily basis. The mean value of the KidMed index at the beginning of the program was 7.09 ± 1.82 points. 52.29% of the patients obtained a qualification according to the KidMed test of “need to improve” and 47.71% obtained the qualification of optimal diet. At the end of the study, 98.6% of the children obtained optimal levels with a mean of 9.21 ± 1.29 points, mean difference of 2.12 ± 0.11 (95% CI: 1.90–2.30

p < 0.01). According to this data, the average value of the KIDMED index evolved from a score considered medium-high at the beginning of the program to an optimal value at the end of the program (

Table 7).

At the beginning of the study, the mean value of the DMT-Test was 6.91 ± 1.98, qualifying as a poor quality diet. 82.3% of the sample obtained a score below 8 points (poor quality diet) and 17.7% obtained a score between 8 and 14 points (need for improvement). At the end of the study, the mean score was 16.3 ± 1.90 points, qualifying as an Optimal Traditional Mediterranean Diet. (

Figure 2). The TMD test evolved from levels considered to be low quality to optimal levels (

Table 8 and

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

In view of these results, we suggest that the Traditional Mediterranean Diet could help in the prevention and control of otitis media with effusion. We have been able to verify that children who have followed our dietary recommendations have improved the inflammatory response and the defensive capacity against the usual infectious diseases. The study shows that a high percentage of patients with OME evolved satisfactorily with the use of TMD; tympanometry normalized in 85% of children. A decrease in the number of recurrent respiratory tract infections and their most frequent complications was also observed. The degree of nasal obstruction (PNO) also decreased. Although flat tympanometry persisted, in the remaining 15% of OME, their hearing and/or their symptoms improved. There was less use of symptomatic drugs, anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Emergency visits decreased and the degree of family satisfaction was high (

Table 1). The number of URIs with bacterial complications decreased by 65% (3.12 from the previous year compared to 1.08 from the year of intervention). The average URI, compared to the previous year, was down 59%; 62% of patients had no bacterial complications during the nutritional intervention period, 29% had only one in the whole year and 10% had two, compared to the three episodes they had on average in the previous year. Children with PNOs went from a mild-moderate to nothing-mild intensity profile. Emergency assistance also decreased by 70%. Antibiotic use decreased by 84.3%, and the use of symptomatic drugs decreased by 57.5%. The majority of patients did not require surgical intervention, and clinical evolution suggests that it will no longer be necessary. This better way to defend against prevalent childhood diseases, together with the best anti-inflammatory response, could be the cause of the progressive decline in PNO in our pediatric population.

The main difficulty was the fulfillment of the diet, as they were proposed to make a homemade diet, family and fresh products that must be prepared and not always the parents had time and dedication to do it properly. The dietitian-nutritionist follow-up contest was essential to ensure compliance. By the end of the program, the dietary habits of the patients had improved in the sample as a whole: An increase in the number of patients consuming fruits, vegetables, nuts, whole grains and fermented dairy products was observed. In general, the consumption of proteins of animal origin was reduced considerably, especially cow’s milk, red meats and meat products. The consumption of processed foods also decreased, especially industrial pastries. The patients showed satisfactory predicted growth rates. Their weight, height and BMI percentile evolved as expected. A positive result was the slight decrease in BMI and fat mass levels and a small increase in height and lean body mass. We have subsequently followed up the children who participated in the study and have not had a recurrence of OME. Some families relaxed the fundamentals of the TMD over time, which led to the development of other inflammatory diseases. This, in turn, required reimplementation of the TMD [

12,

13].

It is important to note that during the time that the incorporation of patients to the study lasted, we extended the application of TMD to the entire pediatric population (siblings, relatives, patients with other recurrent pathologies, and infants under two years of age). This led to a progressive decrease in patients diagnosed with OME, so the achievement of the sample size was delayed. All this has resulted in a decrease in patients diagnosed with OME. It has come become a rare disease in children of our pediatric quota who follow TMD [

23]. The growing interest in the Mediterranean diet is based on its role in inflammatory diseases [

24]. Several clinical and epidemiological studies, as well as experimental studies show that the consumption of the DMT reduces the incidence of certain pathologies related to oxidative stress, chronic inflammation and the immune system, such as cancer, atherosclerosis or cardiovascular disease [

25]. There is evidence that diet and individual nutrients can influence systemic markers of immune function and inflammation [

26]. However, there is no data on its direct action in the pediatric patient. Some data suggest that the follow-up of a diet with an excess of refined flours and processed foods of animal origin, together with an infrequent consumption of fruits and vegetables, is associated with high inflammatory markers [

27]. In studies conducted on mucoid samples of patients with OME, there was a global tendency to increase local pro-inflammatory mediators [

28,

29]. An increase in the markers of oxidative stress in the effusion of children with OME has also been demonstrated, which would lead to a pro-inflammatory and hyper-reactivity state of the mucosa against infectious agents [

30,

31,

32,

33]. The excess “antigenic load” inherent in the Western diet of today, which has multiplied available foodstuffs by the thousand may misadjust our immune system, making it weaker and notably hyperplasic. Children with OMAR show immaturity in antigen presenting cells with a suboptimal response of T cells and B [

34] memory. The absence of Toll-2 receptors (TLR2) can lead to prolonged inflammation of the middle ear. TLR2 is essential for the timely resolution of inflammation since it has been proven to promote macrophage recruitment and bacterial clearance in the mouse [

35]. The pro-inflammatory actions of PAF (platelec-activating factor) can be favorably modulated with DMT and regulate its metabolism [

36].

In recent years, patients diagnosed with food intolerance to cow’s milk proteins and other non-IgE-mediated foods, which cause inflammation in the digestive and respiratory mucous membranes with various symptoms, are increasing. The current treatment of these entities (food intolerances not mediated by IgE, eosinophilic esophagitis, sensitivity to non-celiac wheat, etc.) involves the elimination of the proteins involved [

37,

38,

39]. We believe that sensitization to these proteins may be at the base of the inflammation of the mucosa of the middle ear and for this reason our patients could have responded adequately to their elimination in the diet. Data from several randomized DM-based clinic trials, have demonstrated a beneficial effect in the primary and secondary prevention of disease. The exact mechanism by which an increased adherence to the TMD exerts its favorable effects is not known, although they have been shown to protect against oxidative stress and inflammation [

40].

On the other hand, the microbiota depends to a great extent on the food we eat, and we consider that this issue should be studied in depth in future studies. The follow-up of the DMT is associated with a more beneficial microbiota profile for health, with a higher production of short chain fatty acids, the presence of Prevotella and some Firmicutes capable of degrading fiber [

41]. Diet has a rapid effect on gut microbiota composition, which promotes the growth of certain bacterial groups over others, as well as changes in intestinal pH, intestinal permeability, bacterial metabolites, and thus, inflammation [

42]. The available evidence suggests that gut microbiota of subjects that follow the TMD is significantly different from subjects that follow a Western diet model. The latter shows an increased gut permeability, which is responsible for metabolic endotoxemia. For this reason, we can speculate that the gut microbiota of the subjects following the TMD is able to prevent the onset of chronic non-communicable diseases [

43]. The nasal microbial composition in children with OME is less diverse and with a greater abundance of pathogens than their peers without respiratory infections [

44]. The changes in the levels of citocines, may indicate bacterial pathogen as one of the causes of OME [

45]. The presence of Alloiococcus otitidis has been considered as a precipitating factor of OME [

46]. Likewise, the importance of “bacterial biofilm” and its association with persistent otic disease has been observed [

47,

48,

49]. The local administration of probiotic bacteria seems to have the ability to inhibit the growth of otopathogens [

50]. It is interesting to consider the relationship of DMT with the nasopharyngeal microbiome and the role in the treatment or prevention of OME. The results of this intervention study would point to a possible mechanism of action.

One of the characteristics that every research study should have is that it is easily reproducible, using small groups, and with a little economic cost. The work presented here is easy to reproduce in any primary care pediatric consultation, but it is not easy to perform, due to the lack of nutritionists and the lack of effective monitoring of the diet. Our study has limitations, and particularly the lack of a control group, which would have allowed us to compare the results. We could not perform the study with a control group given that most of our paediatric space adhered to the Mediterranean diet and did not seem ethical to promote a standard western-type diet in a control group. Our hypothesis is that the standard diet proposed by “Western civilization” is the origin of alterations in the inflammatory and immune mechanisms and therefore the cause of most childhood diseases. Although with age comes a slow spontaneous tendency to resolve OME, such a rapid disappearance of symptoms could not be expected. A notable decrease was found in the number of children who required pharmacological and surgical treatment. Therefore, we deduce that the nutritional intervention was beneficial. Pre-test/post-test studies, such as ours are prospective and provide a moderate level of evidence. Most importantly, the results of this research could support further studies on the influence of the Mediterranean diet on this, and other chronic and recurrent inflammatory diseases.

It would have been very interesting to perform analyzes that measured the response of the immune system, inflammatory markers and data on the modification of the microbiota when making the nutritional change. The present study is only part of a general project that we are carrying out, which covers most of the recurrent diseases of childhood. Most of our patients have been consecutively included in the program “Learning to eat from the Mediterranean” and we have verified how the prevalence of OME and other recurrent diseases has decreased considerably. It should not go unnoticed, the change of “model of medicine” that these research studies entail. It is no longer about remedying a disease with external drugs, outside the defensive system or limiting surgical interventions, but the therapeutic proposal is based on providing the body with everything it needs to solve their needs and eliminate that for which it is not ready. We can conclude by saying that the application of the Traditional Mediterranean Diet could have promising effects in the prevention and treatment of otitis media with effusion, with the normalization of tympanometry and hearing loss, with a notable decrease in associated inflammatory diseases, use of drugs and placement of grommets.