Barriers and Facilitators of Online Grocery Services: Perceptions from Rural and Urban Grocery Store Managers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Interview Process

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Rural and Urban Store Descriptives

3.2. Managers’ Perceptions of Offering Online Shopping

3.2.1. Order Fulfilment Challenges

3.2.2. Perceived Customer Barriers

3.2.3. Perceived Customer Benefits

3.3. Brick-and-Mortar Managers’ Barriers and Facilitators to Offering Online Grocery Shopping

3.3.1. Online Shopping Implementation

3.3.2. COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts

3.3.3. Competition with Other Stores

3.3.4. Benefits of Maintaining Brick-and-Mortar Shopping

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Research and Policy

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Hartman Group, Inc. U.S. Grocery Shopper Trends 2018. 2018. Food Market Institute. Available online: https://www.fmi.org/forms/uploadFiles/508C40000000F6.toc.Trends_2018_TOC.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- ERS USDA. Online Redemptions of SNAP and P-EBT Benefits Rapidly Expanded throughout 2020. 2021; United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=100944 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Nevin, F.T.K.C.; Arnow, C.; Mulcahy, M.; Hille, C. Online Grocery Shoppng by NYC Public Housing Residents Using Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Benefits: A Service Ecosystems Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4694. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, S.B.J.; Ng, S.W.; Blitstein, J.L.; Gustafson, A.; Kelley, C.J.; Pandya, S.; Weismiller, H. Perceived Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Grocery Shopping among Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Participants in Eastern North Carolina. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa076. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, O.; Tagliaferro, B.; Rodriguez, N.; Athens, J.; Abrams, C.; Elbel, B. EBT Payment for Online Grocery Orders: A Mixed-Methods Study to Understand Its Uptake among SNAP Recipients and the Barriers to and Motivators for Its Use. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, S.B.J.; Ng, S.W.; Blitstein, J.L.; Gustafson, A.; Niculescu, M. Online grocery shopping: Promise and pitfalls for healthier food and beverage purchases. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 3360–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, E.J.; Silvestri, D.M.; Mande, J.R.; Holland, M.L.; Ross, J.S. Availability of Grocery Delivery to Food Deserts in States Participating in the Online Purchase Pilot. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1916444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERS USDA. Food Access Research Atlas. 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data/fooddesert (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Granheim, S.I.; Løvhaug, A.L.; Terragni, L.; Torheim, L.E.; Thurston, M. Mapping the digital food environment: A systematic scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. NIH on Minority Health and Health Disparities: Overview. 2021. Available online: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Begley, S.; Mikha, E.M.S.; Rettaliata, A. Digital Disruption at the Grocery Store. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/digital-disruption-at-the-grocery-store (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Khandpur, N. Permission to Use Online Grocery Framework; Gillespie, R., Ed.; 2022. [Google Scholar]

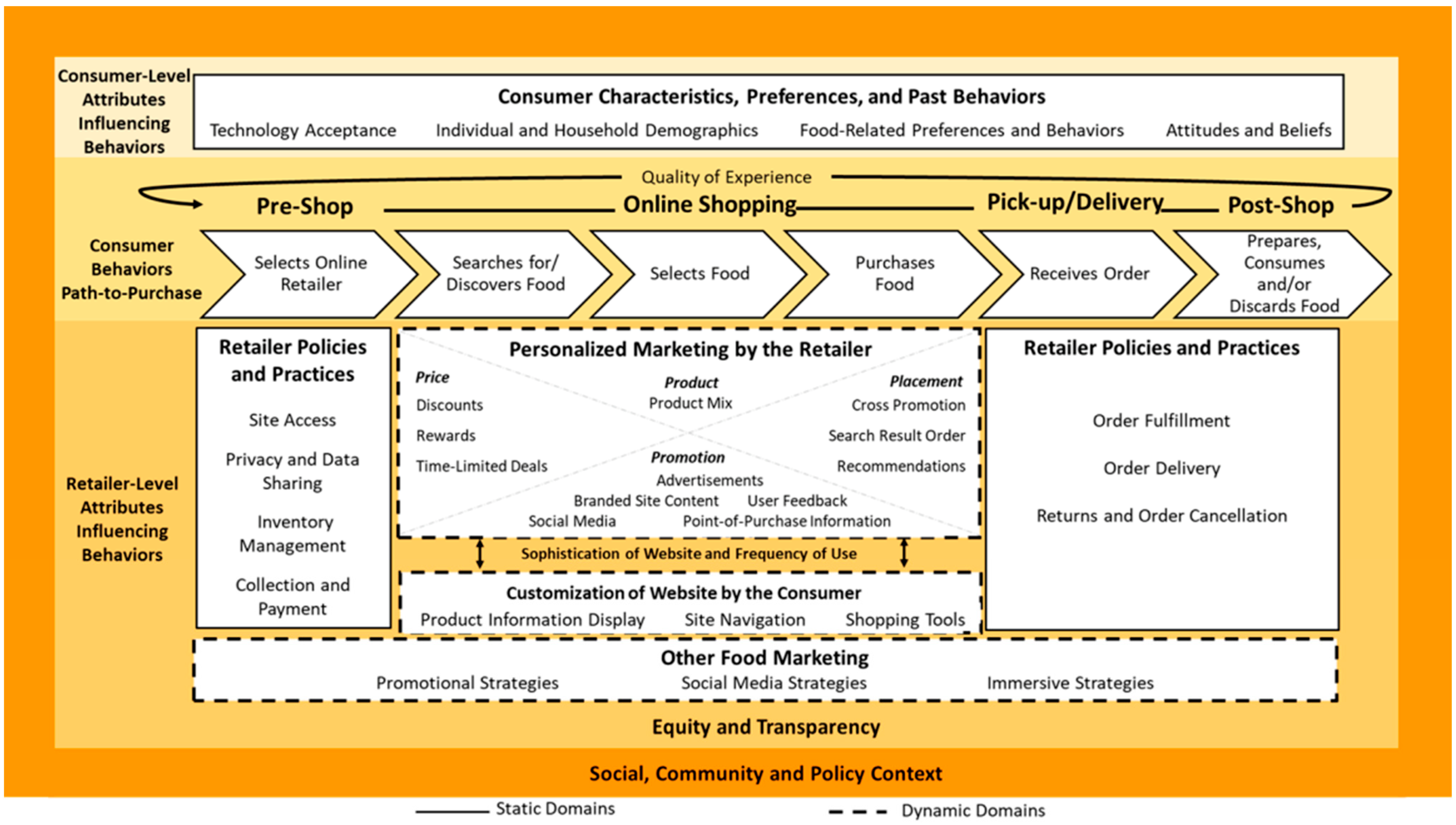

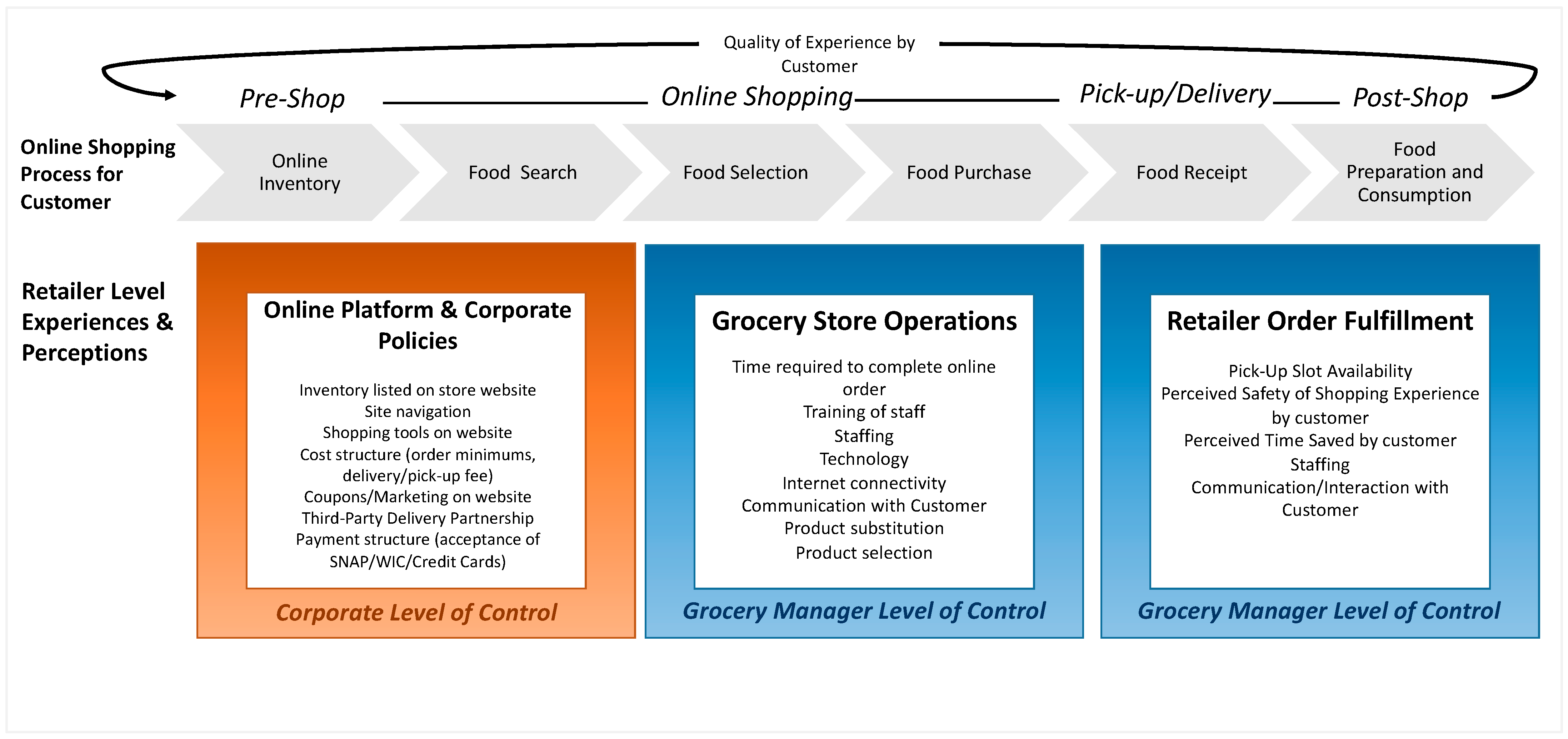

- Khandpur, N.; Zatz, L.Y.; Bleich, S.N.; Taillie, L.S.; Orr, J.A.; Rimm, E.B.; Moran, A.J. Supermarkets in cyberspace: A conceptual framework to capture the influence of online food retail environments on consumer behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Sun, X.; Cannon, M.; Kenney, E.L. The Child and Adult Care Food Program: Barriers to Participation and Financial Implications of Underuse. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 54, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffino, J.A.; Udo, T.; Hormes, J.M. Nudging while online grocery shopping: A randomized feasibility trial to enhance nutrition in individuals with food insecurity. Appetite 2020, 152, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, K.C.; Harrigan, P.B.; Serrano, E.L.; Kraak, V.I. Applying a Multi-Dimensional Digital Food and Nutrition Literacy Model to Inform Research and Policies to Enable Adults in the U.S. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to Make Healthy Purchases in the Online Food Retail Ecosystem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes-Maslow, L.; Osborne, I.; Pitts, S.J. Examining Barriers and Facilitators to Delivering SNAP-Ed Direct Nutrition Education in Rural Communities. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melacini, M.; Perotti, S.; Rasini, M.; Tappia, E. E-fulfilment and distribution in omni-channel retailing: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.C.; Pagliara, F.; Román, C. The research topics on e-grocery: Trends and existing gaps. Sustainability 2019, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, R.; Schwartz, M.; Ghosh, D.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and retail grocery management: Insights from a broad-based consumer survey. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, A.; Gillespie, R.; DeWitt, E.; Cox, B.; Dunaway, B.; Haynes-Maslow, L.; Steeves, E.A.; Trude, A.C.B. Online Pilot Grocery Intervention among Rural and Urban Residents Aimed to Improve Purchasing Habits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERS USDA. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes 2013. 2013. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Liese, A.D.; Weis, K.E.; Pluto, D.; Smith, E.; Lawson, A. Food store types, availability, and cost of foods in a rural environment. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2007, 107, 1916–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.R.; Sharkey, J.R. Rural and Urban Differences in the Associations between Characteristics of the Community Food Environment and Fruit and Vegetable Intake. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headrick, G.; Khandpur, N.; Perez, C.; Taillie, L.S.; Bleich, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Moran, A. Content Analysis of Online Grocery Retail Policies and Practices Affecting Healthy Food Access. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C.G.; Bianchi, C.; Fleischhacker, S.; Bleich, S.N. Nationwide assessment of SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot state communication efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffino, J.A.; Hormes, J.M. A default option to enhance nutrition within financial constraints: A randomized, controlled proof-of-principle trial. Obesity 2018, 26, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthy Meals, Healthy Kids Act; H.R. 8450; U.S. Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Moran, A.; Headrick, G.; Khandpur, N. Promoting Equitable Expansion of the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot. In Healthy Eating Research; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Ed.; Healthy Eating Research: Durham, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E.G. Lincoln and Guba’s Evaluative Criteria. Qualitative Research Guidelines Project 1985. Available online: http://www.qualres.org/HomeLinc-3684.html (accessed on 4 May 2022).

| State | Store Name 1 | Rural (R)/Urban (U) | Brick and Mortar | Online Ordering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tennessee (n = 6) | ||||

| TN | Store A | R | X | |

| TN | Store B | U | X | |

| TN | Store C | R | X | |

| TN | Store D | U | X | |

| TN | Store E | R | X | |

| TN | Store F | R | X | |

| Kentucky (n = 5) | ||||

| KY | Store A | U | X | |

| KY | Store B | U | X | |

| KY | Store C | U | X | |

| KY | Store D | R | X | |

| KY | Store E | R | X | |

| North Carolina (n = 6) | ||||

| NC | Store A | U | X | |

| NC | Store B | U | X | |

| NC | Store C | R | X | |

| NC | Store D | R | X | |

| NC | Store E | R | X | |

| NC | Store F | R | X | |

| New York (n = 6) | ||||

| NY | Store A | U | X | |

| NY | Store B | U | X | |

| NY | Store C | U | X | |

| NY | Store D | U | X | |

| NY | Store E | U | X | |

| NY | Store F | U | X | |

| Theme | Subtheme | Description | Illustrative Quotes (R/U) | # of Interviews That Mention This Theme | # of Times This Code Was Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order fulfilment challenges | Store-related challenges to online order fulfillment. | “They purchase so much, like $500, $600 grocery orders, which I think in the store, it would fill up two or maybe three of those regular shopping carts. So if you can just imagine that coming down the check lane.”… “It takes a lot of dedication and focus to make sure that we do our best to make sure every order gets completed in a timely manner, but those things specifically, I would say are out of our control, definitely slow us down.” (U) “We had to get more people in the store trained to pick orders and to do pick up, as more people tried to transition to that.” (R) | 17 | 42 | |

| Staffing | Staffing-related issues contributing to the challenges of online order fulfillment. | “These days, you can’t find good decision-making adults that want this job because they’re only going to make $12 an hour. They can’t feed their family with $12 an hour. So I get a lot of high school kids, a lot of really young college kids and some of them are great. They make great decisions. They’re just really good kids.” (U) “The labor situation is the worst I’ve ever seen it. I’ve worked for [store name] for 15 years and there’s nothing even close to what we’re dealing with right now.” (R) | 14 | 37 | |

| Technology | Technology-related issues that may contribute to fulfilling online grocery orders. | “And so right now we’re using tablets to process those payments and [Store name] likes to run before they walk sometimes. And the push to get those tablets out was pretty big. And they’re great when they work. But if the wind blows the wrong... they don’t really have great connectivity. They don’t have their own cellular data. So they’re actually pulling off WiFi from the store.” (U) “I think the biggest thing that, I guess, [store name] needs to work on, is the online software, the system that they use. I think it definitely needs to be store specific. It’s aggravating because I want to make it store specific, but that’s obviously not my job. It needs to be because it frustrates the customers. It frustrates us, the people who have to fulfill the orders.” (R) | 10 | 25 | |

| Third-party delivery options | Intersection of additional platforms being used for delivery-like services that allow customers to complete an online grocery order that is then delivered by the third-party provider to the customers home (or delivery address of choice). | “There’s not a lot of accountability on [third-party delivery company] end when things go wrong”… “Which is very frustrating because if you get on [Store Name] website and you go to order delivery, it looks like we’re doing it.” (U) “Well at the volume that [third-party delivery company] did for me wasn’t good enough and the cost was too high because I was still paying, between payroll and expenses, about 30 cents on the dollar of everything I buy and then they were charging me 15% of the (customer) transaction, so that was bringing down my transaction price. I was working on about 55 cents on the dollar and that was costing me about 45% of investment to do that transaction (with the third-party delivery company). The volume wasn’t there so I gave it up.” (U) | 17 | 54 | |

| Perceived customer barriers | Manager perception, or direct feedback from customers, regarding the disadvantages to the online ordering process and use. | “And sometimes customers are okay with not getting an item, or sometimes they just don’t like the item we choose. But that’s one of the biggest obstacles.” (R) “And I guess the app is not tied to our actual on-hand inventory. So it doesn’t know that such and such is out of stock.” (U) | 12 | 30 | |

| Cost | Additional fees incurred due to utilization of the online platform for purchasing groceries. | “There is a 4.99 fee at our location, at all [store name] locations. That is sometimes a customer concern. Some other retailers may not charge a fee. But we do have a fee currently, and that might be something that changes in the future.” (R) “The only thing we have in pick up is if your order’s not over $35, it’s a 4.95 charge. That’s the only other charging take up that is there.” (R) | 18 | 47 | |

| Perceived customer benefits | Manager perception of the benefits customers receive from their store using an online shopping platform to do their grocery shopping. | “So directly from the customer, we get a lot of your time saver, people with mobility issues that can’t come into the store usually. So those are kind of the easy ones. New moms who have newborns, if they don’t want to bring them into the store, I wish it was around when I had my newborns. So those are kind of the big ones.” (U) “And I also see at this location, what I haven’t seen as much in other locations since then, a lot of times we’ll have organizations that will order their orders online, maybe churches, or daycares, and stuff like that, that’ll order large bulk orders online to pick them up. And like I said, a lot of times it’s just a matter of convenience and a time saver for various different people.” (R) | 14 | 31 | |

| Personal connection | Ability to personally communicate through the online shopping mechanism or platform. | “They do a good job. If you got you good personnel that communicates correctly. And so when they do that job well, and that customer gets used to them, it’s just like that is their personal shopper, and they know their name. They know who they are. They talk to them every week. That means something.” (R) “We do have a good communication feature through our app, though. So they’re able to... I think it’s like a voice-to-text kind of deal and they’re able to be like, ‘Hey, we’re out of this, does this work for you?’ That kind of thing. So that way we do have a really good communication with the people that place the orders.” (U) | 17 | 33 |

| Theme | Subtheme | Description | Illustrative Quotes (R/U) | # of Interviews That Mention This Theme | # of Times This Code Was Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online shopping implementation | Feasibility of offering online shopping for the respective store. General feedback from store manager regarding the implementation and act of online grocery shopping. | “In general I think it is a great idea. And I’m looking forward to... Especially if we are able to incorporate EBTs with food stamps into that in a official or legal capacity, I feel like that would be amazing and I feel like that could really boost our business.” (R) “I think it’s the way it’s moving. I don’t think you can’t undo what’s already been done. You can’t go backwards. And so I think that’s where it’s headed. Not only is it convenient for families in general, who are moving in a million different directions, the convenience of quickly ordering your groceries when you’re on lunch break and then quickly grabbing them on your way home from dinner or ball practice or whatever it is. I just think it just makes sense with our current lifestyle right now.” (R) | 9 | 29 | |

| Perceived customer response to offering online ordering | Store manager thoughts on utilization of online ordering if the store was to offer it in the future. | “Personally, I think that with our younger crowd and our almost say our middle-aged crowd, of those that already have say established families, younger families, middle school, high school families. I think they would really enjoy that opportunity.” (R) “So definitely our handicapped customers, I would say, would probably be using it the most, I know that there’s quite a few customers that have wheelchairs, or the elderly. We have currently quite a few people who will sit in our parking lot and call us and give us a list of stuff to pick out for you.”… “So, that probably would be the targeted demographic.” (R) | 8 | 13 | |

| Barriers to implementation and overall change | Logistic or employee barriers that would need to be overcome before attempting to make changes at their store to include offering online shopping. | “Yeah, staffing, because we don’t have the disposable income and payroll to just be able to pay someone to be there extra each day. I know most days we are either sending people home early because they cannot stay or asking people to stay late because we just need some extra people there, unfortunately, and it’s on such a day-by-day basis.” “Yeah, it’s a process. There’s certain things you have to have in place. You have to have your infrastructure, you have to have your tech there. And until you have those things there, you can’t even really.” | 9 | 23 | |

| COVID-19 pandemic impacts | Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the store operations (physically or economically), manager roles, or consumer shopping behavior. | “I think what we strived to do during the pandemic last year is to be a calming force, if that makes any sense. We had a lot of panic buying, a lot of panic shopping and everything. It just goes right back to the basics of good service.” “We went days that it was every day, he had to shift and adjust. There was one day that we didn’t have anybody in produce. No one to do produce because we were waiting to hear back about who was good and who wasn’t good. And one day we didn’t have two bag boys.” (R) “And so I just went to [co-worker] and I said, I guess we’re baggers this afternoon.” (R) | 9 | 29 | |

| Competition with other stores | Assessing the influence of customer changes as a result of other convenience, dollar, and online store offerings or competition. | “I would say there is still some loyalty, as far as the change, but I had found that you really got to fight a little harder now. One thing that has changed, pretty much everybody’s in the grocery business now. Twenty-five years ago when I started, [Supercenter] was really not a player in the grocery industry per se, but they are now. A lot of your dollar stores.”… “You’ve got a lot more competition as far as that goes, beyond just your traditional competitors.” (R) “We’re very rural. There’s still a vast amount of people who still do go shopping. So [Supercenter], I would say, would be the more... What’s the word? Competitive, I would say, in terms of fighting for our business, the business of our customers. And they have just recently started offering the shopping online.” (R) | 7 | 18 | |

| Benefits to maintaining brick-and-mortar shopping | Manager perceived beliefs about the benefits of remaining an in-person-only operation. | “Well, the being personable, of course. The hand-to-hand connection you have with our customers, because our customers... Mainly our customer quality is because of the friendly atmosphere, the family atmosphere. I mean, that’s what we thrive on. We thrive to be family-like to our customers, and we know some of them intimately. I mean, just, we know their children, we know their children’s children.” (R) “Well, you don’t get that one-on-one time either. They come in and talk to you every day. They can tell you their story, their whole life story and all that, and you can’t just walk in. You’ve got to order it online, and then wait until they say it’s ready. You might have something you need to do and your groceries aren’t ready, so what are you going to do?” (R) | 5 | 16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gillespie, R.; DeWitt, E.; Trude, A.C.B.; Haynes-Maslow, L.; Hudson, T.; Anderson-Steeves, E.; Barr, M.; Gustafson, A. Barriers and Facilitators of Online Grocery Services: Perceptions from Rural and Urban Grocery Store Managers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183794

Gillespie R, DeWitt E, Trude ACB, Haynes-Maslow L, Hudson T, Anderson-Steeves E, Barr M, Gustafson A. Barriers and Facilitators of Online Grocery Services: Perceptions from Rural and Urban Grocery Store Managers. Nutrients. 2022; 14(18):3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183794

Chicago/Turabian StyleGillespie, Rachel, Emily DeWitt, Angela C. B. Trude, Lindsey Haynes-Maslow, Travis Hudson, Elizabeth Anderson-Steeves, Makenzie Barr, and Alison Gustafson. 2022. "Barriers and Facilitators of Online Grocery Services: Perceptions from Rural and Urban Grocery Store Managers" Nutrients 14, no. 18: 3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183794

APA StyleGillespie, R., DeWitt, E., Trude, A. C. B., Haynes-Maslow, L., Hudson, T., Anderson-Steeves, E., Barr, M., & Gustafson, A. (2022). Barriers and Facilitators of Online Grocery Services: Perceptions from Rural and Urban Grocery Store Managers. Nutrients, 14(18), 3794. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183794