Fish Consumption during Pregnancy in Relation to National Guidance in England in a Mixed-Methods Study: The PEAR Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Design

2.2. Questionnaire: Quantitative Data

2.2.1. Development

2.2.2. Application

- (1)

- Screening questions (consent, location during pregnancy, age of baby).

- (2)

- Demographics (e.g., geographical location, ethnicity, age, highest educational qualification, household income, parity). Where comparable data were available, the values were compared with the most recent values for the population in England to gauge the representativeness of the participants [21,22,23].

- (3)

- Consumption of fish (before and during pregnancy). There were three questions in relation to fish consumption (Table 1). The items included were seafood items listed in the NHS website with guidance to avoid or limit during pregnancy because of potential mercury exposure. The questionnaire did not include items that involved guidance on preparation or cooking methods (uncooked shellfish, sushi without freezing the raw fish) or supplements derived from fish oil (for example, cod liver oil). Assessment of compliance with guidance on thoroughly cooking smoked fish or only eating sushi comprising cooked fish was not included as these were added as updates to the guidance after the survey had closed.

- (4)

- Sources of information about the guidance (e.g., midwife or other healthcare professional, NHS website, other websites, leaflets, apps, friends and relatives). Participants were also asked to provide free text on which sources of information they trusted and which they felt less confident in. The questions in this section allowed for multiple answers to be given.

2.3. In-Depth Interviews: Qualitative Data

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Questionnaire: Quantitative Data

2.4.2. In-Depth Interviews: Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire: Quantitative Data

3.2. In-Depth Interviews: Qualitative Data

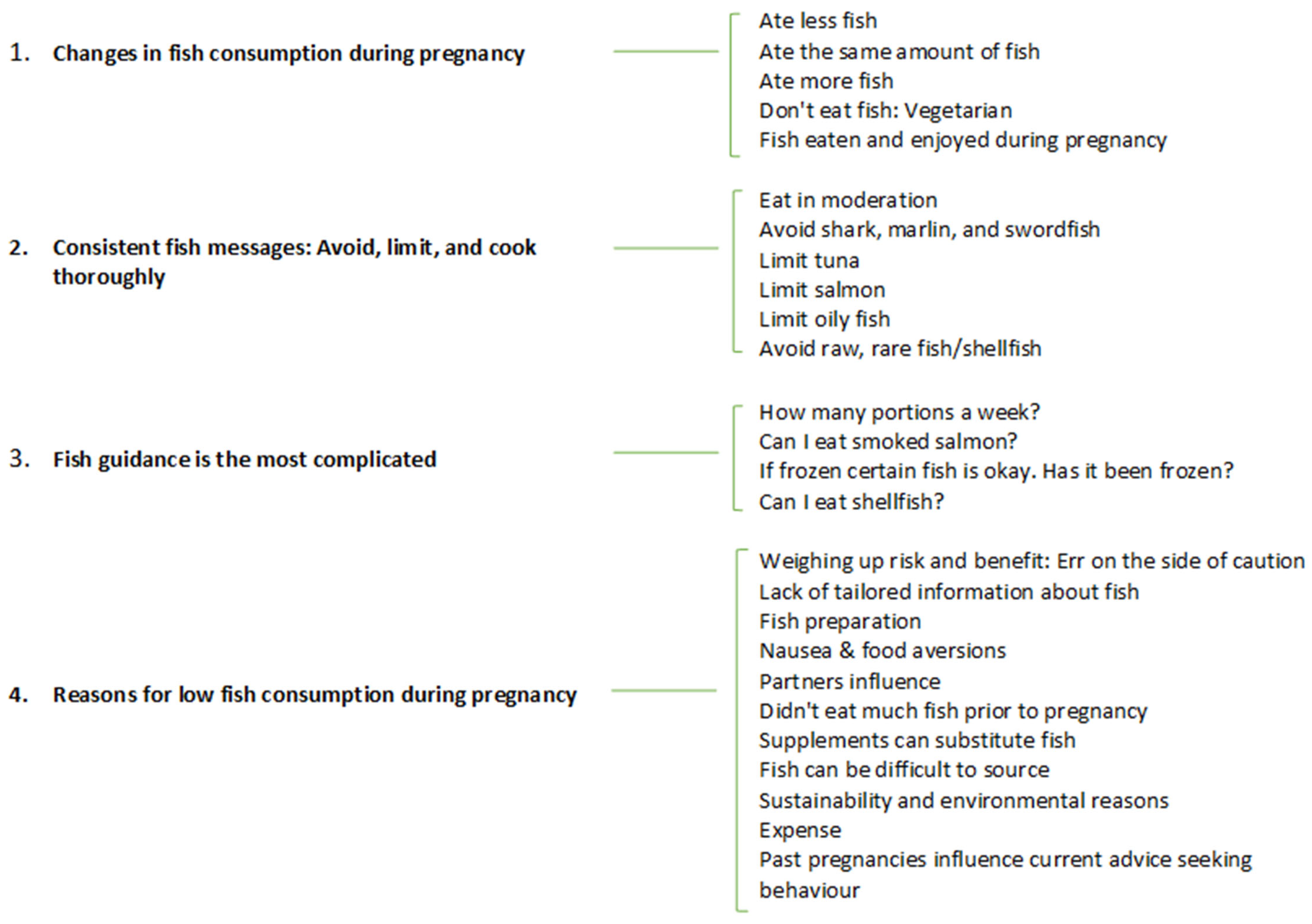

3.2.1. Changes in Fish Consumption during Pregnancy

3.2.2. Salient Fish Messages: Avoid, Limit and Cook Thoroughly

3.2.3. Fish Guidance Is the Most Complicated

3.2.4. Reasons for Low Fish Consumption during Pregnancy

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NHS. Have a Healthy Diet in Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/keeping-well/have-a-healthy-diet/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- NHS. Fish and Shellfish: Eat Well. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/fish-and-shellfish-nutrition/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- NHS. Foods to Avoid in Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/foods-to-avoid-pregnant/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- NHS. Drinking Alcohol While Pregnant. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/keeping-well/drinking-alcohol-while-pregnant/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- NHS. Vitamins, Supplements and Nutrition in Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/keeping-well/vitamins-supplements-and-nutrition/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- NHS. Toxoplasmosis. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/toxoplasmosis/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Hibbeln, J.R.; Spiller, P.; Brenna, J.T.; Golding, J.; Holub, B.J.; Harris, W.S.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Lands, B.; Connor, S.L.; Myers, G.; et al. Relationships between seafood consumption during pregnancy and childhood and neurocognitive development: Two systematic reviews. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat. Acids 2019, 151, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella-Garcia, C.; Julvez, J. Seafood intake and neurodevelopment: A systematic review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2014, 1, 44–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, P.; Charlton, K.; McMahon, A.T.; Lucas, C. Fish intake during pregnancy and foetal neurodevelopment—A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Advice on Fish Consumption: Benefits and Risks. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/338801/SACN_Advice_on_Fish_Consumption.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Taylor, C.M.; Emmett, P.M.; Emond, A.M.; Golding, J. A review of guidance on fish consumption in pregnancy: Is it fit for purpose? Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2149–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomingdale, A.; Guthrie, L.B.; Price, S.; Wright, R.O.; Platek, D.; Haines, J.; Oken, E. A qualitative study of fish consumption during pregnancy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C.; Starling, P.; McMahon, A.; Charlton, K. Erring on the side of caution: Pregnant women’s perceptions of consuming fish in a risk averse society. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2016, 29, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykjaer, C.; Higgs, C.; Greenwood, D.C.; Simpson, N.A.B.; Cade, J.E.; Alwan, N.A. Maternal fatty fish intake prior to and during pregnancy and risks of adverse birth outcomes: Findings from a British cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, C.; Calder, P.; Inskip, H.; Godfrey, K.; Cooper, C.; Robinson, S.M.; SWS Study Group. Oily fish consumption and n-3 fatty acid status in late pregnancy: The Southampton Women’s Survey. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, E482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. NDNS: Results from Years 9 to 11 (2016 to 2017 and 2018 to 2019). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Jisc. Available online: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- The Pear Study. The Pear Study: Pregnancy, the Environment And Nutrition. Available online: http://pearstudy.com/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Horwood, J.; Sutton, E.; Coast, J. Evaluating the face validity of the ICECAP-O capabilities measure: A “Think Aloud” study with hip and knee arthroplasty patients. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2014, 9, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasant, L.; Ingram, J.; Tonks, R.; Taylor, C.M. Provision of information by midwives for pregnant women in England on guidance on foods/drinks to avoid or limit. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Educational Attainment and Labour Force Status. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=EAG_NEAC (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Office of National Statistics. Population Estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Provision: Mid-2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2019#population-age-structures-of-uk-countries-and-english-regions (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Office for National Statistics. Birth Characteristics in England and Wales. 2017. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales/2017#main-points (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- QRS International PTY Ltd. NVivo. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. Seaspiracy. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seaspiracy (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Public Health England. Listeriosis in England and Wales: Summary for 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/listeria-monocytogenes-surveillance-reports/listeriosis-in-england-and-wales-summary-for-2019 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- World Health Organization. Mercury and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mercury-and-health#:~:text=Mercury%20is%20considered%20by%20WHO%20as%20one%20of,the%20compound.%20Methylmercury%20is%20very%20different%20to%20ethylmercury (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Taylor, C.M.; Golding, J.; Emond, A.M. Blood mercury levels and fish consumption in pregnancy: Risks and benefits for birth outcomes in a prospective observational birth cohort. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2016, 219, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, I.; Emmett, P.; Ness, A.; Golding, J. Maternal fish intake in late pregnancy and the frequency of low birth weight and intrauterine growth retardation in a cohort of British infants. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, H.; Tinker, S.C. Seafood consumption among pregnant and non-pregnant women of childbearing age in the United States, NHANES 1999-2006. Food Nutr. Res. 2014, 58, 23287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oken, E.; Kleinman, K.P.; Berland, W.E.; Simon, S.R.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Gillman, M.W. Decline in fish consumption among pregnant women after a national mercury advisory. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 102, 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- Govzman, S.; Looby, S.; Wang, X.; Butler, F.; Gibney, E.R.; Timon, C.M. A systematic review of the determinants of seafood consumption. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.F.; Ismail, K.; Fahy, U. Listeria awareness among recently delivered mothers. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2013, 33, 814–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Kelly, M.; Noel, M.; Brisdon, S.; Berkowitz, J.; Gustafson, L.; Galanis, E. Pregnant women’s knowledge, practices, and needs related to food safety and listeriosis: A study in British Columbia. Can. Fam. Physician 2012, 58, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, J.; Waller, A.; Cameron, E.; Hure, A.; Sanson-Fisher, R. Diet during pregnancy: Women’s knowledge of and adherence to food safety guidelines. Aust. N. Z. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2017, 57, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C.; Charlton, K.E.; Yeatman, H. Nutrition advice during pregnancy: Do women receive it and can health professionals provide it? Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 2465–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, S.R.; Robinson, S.M.; Borland, S.E.; Godfrey, K.M.; Cooper, C.; Inskip, H.M.; SWS Study Group. Do women change their health behaviours in pregnancy? Findings from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2009, 23, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Pope, L. When do gain-framed health messages work better than fear appeals? Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions in Relation to Fish | Response Options |

|---|---|

| Thinking about fish, was there any difference in how often you ate it during your recent pregnancy compared with before you were pregnant? | Ate more often Ate same Ate less often Ate before pregnancy but avoided during recent pregnancy Don’t eat anyway Don’t know/Can’t remember |

| Before your recent pregnancy how often did you eat fish? While you were pregnant recently how often did you eat fish? | Never Less than twice a week Twice a week More than twice a week Don’t know/Can’t remember |

| Before your recent pregnancy how often did you eat these types of fish and seafood? While you were pregnant recently how often did you eat these types of fish and seafood? | Never Less than once per month 1–2 times a month Once a week Several times a week Don’t know/Can’t remember |

|

| Characteristic | Completing Questionnaire | Completing In-Depth Discussion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Value | National Indicator [23,24,25] | n | Value | |

| Age (years) | 548 | Range 21–46, Median 33 (IQR 30–36) | Mean maternal age at birth 30.5 | 14 | Range 30–41, Median 34 |

| 18–25 | 0 | ||||

| >25–35 | 9 | ||||

| >35 | 5 | ||||

| Home location | 598 | 14 | |||

| North East/North West/Yorkshire and Humberside | 153 (26%) | 28% | 0 | ||

| East Midlands/West Midlands | 106 (18%) | 20% | 3 | ||

| East/Greater London/South East/South West | 339 (57%) | 53% | 11 | ||

| Highest educational attainment | 596 | 14 | |||

| None/GCSE/Vocational level 1 and 2/AS or A level/Vocational level 3 | 114 (19%) | 50% | 1 | ||

| University degree (BSc, BA)/Professional qualification/Vocational levels 4 and 5/University higher degree (MA, MSc, PhD) | 482 (81%) | 50% | 13 | ||

| Household income | 561 | 14 | |||

| <£30,000 | 89 (16%) | 50% | 4 | ||

| ≥£50,000 | 472 (84%) | 50% | 10 | ||

| Parity | 597 | 14 | |||

| 1 | 432 (72%) | 42% | 8 | ||

| >1 | 165 (28%) | 58% | 6 | ||

| Ethnicity | 593 | 14 | |||

| White | 563 (95%) | 80% | 12 | ||

| Other | 30 (5%) | 20% | 2 | ||

| Age of baby (months) | 598 | 14 | |||

| 0–5 | 371 (62%) | 10 | |||

| 6–12 | 227 (38%) | 4 | |||

| Followed a particular diet before pregnancy | 598 | 14 | |||

| Yes | 122 (20%) | 2 | |||

| No | 476 (80%) | 12 | |||

| Paid work during pregnancy | 598 | 14 | |||

| Yes | 547 (92%) | 11 | |||

| No | 51 (9%) | 3 | |||

| Smoking | 596 | 13 | |||

| No | 576 (97%) | 12 | |||

| Yes | 20 (3%) | 1 | |||

| Home internet access | 598 | 14 | |||

| Yes | 598 (100%) | 14 | |||

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 | |||

| Total Fish | N | Frequency of Consumption in Total Group a | Compliance with Guidance on Total Number of Portions per Week b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total a | Consumers | Never | <Twice per Week | Twice per Week | >Twice per Week | Chi Square Test p Value | All Respondents | Consumers Only | |

| Before pregnancy | 595 | 500 (84%) | 95 (16%) | 319 (54%) | 142 (24%) | 39 (7%) | <0.001 | 181 (30%) | 181 (36%) |

| During pregnancy | 595 | 495 (83%) | 100 (17%) | 338 (57%) | 131 (22%) | 26 (4%) | 157 (26%) | 157 (32%) | |

| Fish Type | N | Frequency of Consumption in Total Group a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Consumers | Never | Less than Once per Month | About One or Two Times per Month | About Once per Week | Several Times per Week | Chi Square Test p Value | |

| White fish | ||||||||

| Before pregnancy | 597 | 483 (81%) | 114 (19%) | 104 (17%) | 246 (41%) | 123 (21%) | 10 (2%) | <0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 598 | 466 (78%) | 131 (22%) | 120 (20%) | 205 (34%) | 133 (22%) | 8 (1%) | |

| Oily fish | ||||||||

| Before pregnancy | 595 | 405 (68%) | 190 (32%) | 93 (16%) | 159 (27%) | 131 (22%) | 22 (4%) | <0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 596 | 364 (61%) | 232 (39%) | 87 (15%) | 144 (24%) | 118 (20%) | 15 (3%) | |

| Shark/marlin/swordfish | ||||||||

| Before pregnancy | 586 | 45 (8%) | 541 (92%) | 45 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 590 | 5 (1%) | 585 (99%) | 5 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Tinned tuna | ||||||||

| Before pregnancy | 595 | 420 (71%) | 175 (29%) | 112 (19%) | 182 (31%) | 103 (17%) | 23 (4%) | <0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 593 | 377 (64%) | 216 (36%) | 113 (19%) | 157 (26%) | 95 (16%) | 12 (2%) | |

| Fresh tuna | ||||||||

| Before pregnancy | 588 | 163 (28%) | 425 (72%) | 131 (22%) | 22 (4%) | 5 (1%) | 5 (1%) | <0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 587 | 50 (9%) | 537 (91%) | 39 (7%) | 11 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Shellfish | ||||||||

| Before pregnancy | 593 | 359 (61%) | 234 (39%) | 170 (29%) | 135 (23%) | 49 (8%) | 5 (1%) | <0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 595 | 216 (36%) | 379 (64%) | 108 (18%) | 75 (13%) | 30 (5%) | 3 (1%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beasant, L.; Ingram, J.; Taylor, C.M. Fish Consumption during Pregnancy in Relation to National Guidance in England in a Mixed-Methods Study: The PEAR Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143217

Beasant L, Ingram J, Taylor CM. Fish Consumption during Pregnancy in Relation to National Guidance in England in a Mixed-Methods Study: The PEAR Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(14):3217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143217

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeasant, Lucy, Jenny Ingram, and Caroline M. Taylor. 2023. "Fish Consumption during Pregnancy in Relation to National Guidance in England in a Mixed-Methods Study: The PEAR Study" Nutrients 15, no. 14: 3217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143217

APA StyleBeasant, L., Ingram, J., & Taylor, C. M. (2023). Fish Consumption during Pregnancy in Relation to National Guidance in England in a Mixed-Methods Study: The PEAR Study. Nutrients, 15(14), 3217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143217