How to Keep the Balance between Red and Processed Meat Intake and Physical Activity Regarding Mortality: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

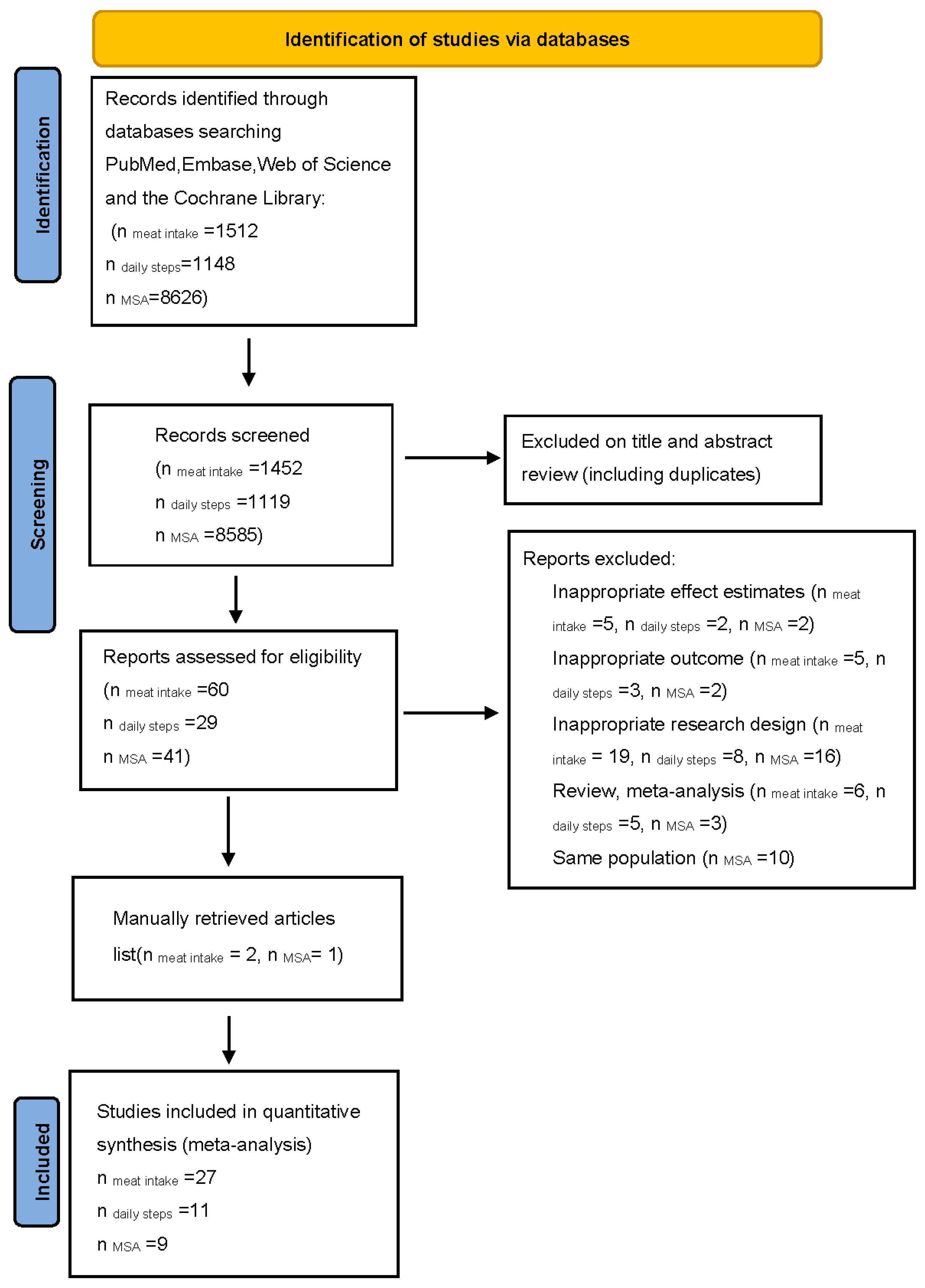

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment and GRADE Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

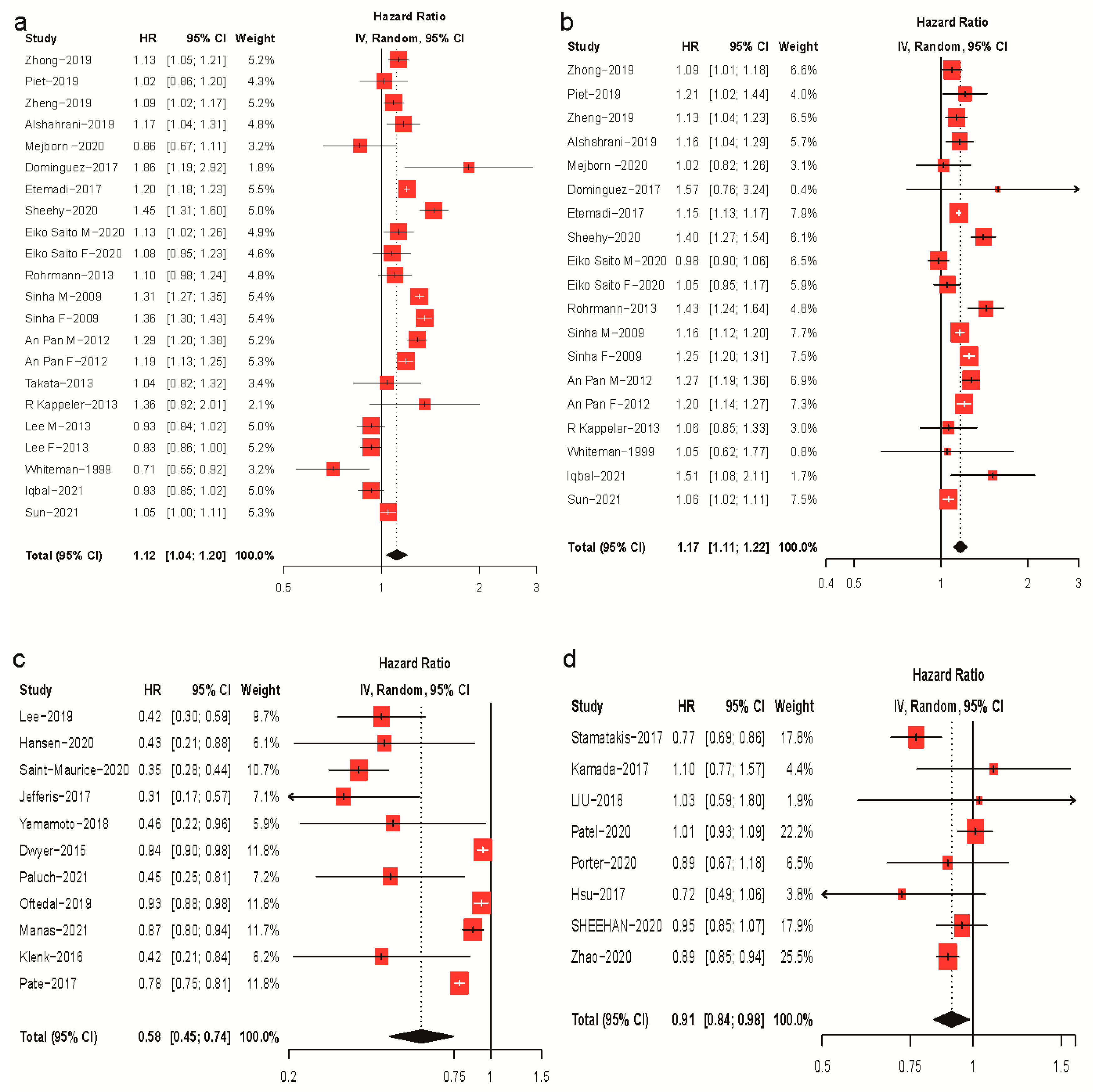

3.1. Meta-Analysis of Meat Intake, Physical Activity, and Mortality Risk

3.2. Dose–Response Analysis of Meat Intake and Mortality Risk

3.3. Dose–Response Analysis of Daily Steps, MSAs, and Mortality Risk

3.4. Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

3.5. GRADE Assessment

3.6. Balanced Dose–Response Relationship between Meat Intake and Physical Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings of this Study

4.2. Comparison with Other Studies and Mechanistic Insights

4.3. Strengths and Weaknesses of this Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. NCD Mortality and Morbidity. 2017, Volume 18. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/ncd-mortality (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Stewart, C.; Piernas, C.; Cook, B.; Jebb, S.A. Trends in UK meat consumption: Analysis of data from years 1–11 (2008–09 to 2018–19) of the National Diet and Nutrition Survey rolling programme. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e699–e708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Ruan, M.; Liu, J.; Wilde, P.; Naumova, E.N.; Mozaffarian, D.; Zhang, F.F. Trends in Processed Meat, Unprocessed Red Meat, Poultry, and Fish Consumption in the United States, 1999–2016. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1085–1098.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361, eaam5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flegal, K.M.; Kit, B.K.; Orpana, H.; Graubard, B.I. Association of All-Cause Mortality with Overweight and Obesity Using Standard Body Mass Index Categories: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013, 309, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rouhani, M.H.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Azadbakht, L. Is there a relationship between red or processed meat intake and obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paluch, A.E.; Bajpai, S.; Bassett, D.R.; Carnethon, M.R.; Ekelund, U.; Evenson, K.R.; Galuska, D.A.; Jefferis, B.J.; Kraus, W.E.; Lee, I.-M.; et al. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e219–e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, E.L.; Rezende, L.F.M.; Lee, D.H. Muscle-strengthening activities and risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer and mortality: A review of prospective cohort studies. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bekkering, G.E.; Harris, R.J.; Thomas, S.; Mayer, A.-M.B.; Beynon, R.; Ness, A.R.; Harbord, R.M.; Bain, C.; Smith, G.D.; Sterne, J.A.C. How Much of the Data Published in Observational Studies of the Association between Diet and Prostate or Bladder Cancer Is Usable for Meta-Analysis? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 167, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Fraser, G.E.; Sabaté, J.; Knutsen, R.; Shavlik, D.; Mashchak, A.; Lloren, J.I.; Orlich, M.J. Red and Processed Meat and Mortality in a Low Meat Intake Population. Nutrients 2019, 11, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whiteman, D.; Muir, J.; Jones, L.; Murphy, M.; Key, T. Dietary questions as determinants of mortality: The OXCHECK experience. Public Health Nutr. 1999, 2, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Gea, A.; Barbagallo, M.; Martínez-González, M.A. Should we recommend reductions in saturated fat intake or in red/processed meat consumption? The SUN prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Etemadi, A.; Sinha, R.; Ward, M.H.; Graubard, B.I.; Inoue-Choi, M.; Dawsey, S.M.; Abnet, C.C. Mortality from Different Causes Associated with Meat, Heme Iron, Nitrates, and Nitrites in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study: Population Based Cohort Study. BMJ 2017, 357, j1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, R.; Dehghan, M.; Mente, A.; Rangarajan, S.; Wielgosz, A.; Avezum, A.; Seron, P.; AlHabib, K.F.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Swaminathan, S.; et al. Associations of unprocessed and processed meat intake with mortality and cardiovascular disease in 21 countries [Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study]: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappeler, R.; Eichholzer, M.; Rohrmann, S. Meat consumption and diet quality and mortality in NHANES III. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; McLerran, D.F.; Rolland, B.; Chen, Y.; Grant, E.J.; Vedanthan, R.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; Gao, Y.-T.; Tsuji, I.; et al. Meat intake and cause-specific mortality: A pooled analysis of Asian prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mejborn, H.; Møller, S.P.; Thygesen, L.C.; Biltoft-Jensen, A. Dietary Intake of Red Meat, Processed Meat, and Poultry and Risk of Colorectal Cancer and All-Cause Mortality in the Context of Dietary Guideline Compliance. Nutrients 2020, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Pan, A.; Bernstein, A.M.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Red Meat Consumption and Mortality: Results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sinha, R.; Graubard, B.I.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Schatzkin, A. Meat Intake and Mortality: A Prospective Study of Over Half a Million People. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, S.; Overvad, K.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Egeberg, R.; Tjønneland, A.; Nailler, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Krogh, V.; et al. Meat consumption and mortality—Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saito, E.; Tang, X.; Abe, S.K.; Sawada, N.; Ishihara, J.; Takachi, R.; Iso, H.; Shimazu, T.; Yamaji, T.; Iwasaki, M.; et al. Association between meat intake and mortality due to all-cause and major causes of death in a Japanese population. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehy, S.; Palmer, J.R.; Rosenberg, L. High Consumption of Red Meat Is Associated with Excess Mortality Among African-American Women. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 3249–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Wallace, R.B.; Shadyab, A.H.; Kroenke, C.H.; Haring, B.; Howard, B.V.; Shikany, J.M.; Valdiviezo, C.; et al. Association of Major Dietary Protein Sources with All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e015553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, Y.; Shu, X.-O.; Gao, Y.-T.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J.; Cai, H.; Yang, G.; Xiang, Y.-B.; Zheng, W. Red Meat and Poultry Intakes and Risk of Total and Cause-Specific Mortality: Results from Cohort Studies of Chinese Adults in Shanghai. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van den Brandt, P.A. Red meat, processed meat, and other dietary protein sources and risk of overall and cause-specific mortality in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Satija, A.; Pan, A.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Rimm, E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Association of changes in red meat consumption with total and cause specific mortality among US women and men: Two prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2019, 365, l2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, V.W.; Van Horn, L.; Greenland, P.; Carnethon, M.R.; Ning, H.; Wilkins, J.T.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Allen, N. Associations of Processed Meat, Unprocessed Red Meat, Poultry, or Fish Intake with Incident Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, T.; Pezic, A.; Sun, C.; Cochrane, J.; Venn, A.; Srikanth, V.; Jones, G.; Shook, R.; Sui, X.; Ortaglia, A.; et al. Objectively Measured Daily Steps and Subsequent Long Term All-Cause Mortality: The Tasped Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.H.; Dalene, K.E.; Ekelund, U.; Fagerland, M.W.; Kolle, E.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Tarp, J.; Anderssen, S.A. Step by step: Association of device-measured daily steps with all-cause mortality—A prospective cohort Study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, B.J.; Parsons, T.J.; Sartini, C.; Ash, S.; Lennon, L.T.; Papacosta, O.; Morris, R.W.; Wannamethee, S.G.; Lee, I.-M.; Whincup, P.H. Objectively measured physical activity, sedentary behaviour and all-cause mortality in older men: Does volume of activity matter more than pattern of accumulation? Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 53, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenk, J.; Dallmeier, D.; Denkinger, M.D.; Rapp, K.; Koenig, W.; Rothenbacher, D. ActiFE Study Group Objectively Measured Walking Duration and Sedentary Behaviour and Four-Year Mortality in Older People. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Kamada, M.; Bassett, D.R.; Matthews, C.E.; Buring, J.E. Association of Step Volume and Intensity with All-Cause Mortality in Older Women. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mañas, A.; Cruz, B.D.P.; Ekelund, U.; Reyna, J.L.; Gómez, I.R.; Carreño, J.A.C.; Mañas, L.R.; García, F.J.G.; Ara, I. Association of accelerometer-derived step volume and intensity with hospitalizations and mortality in older adults: A prospective cohort study. J. Sport Health Sci. 2021, 11, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oftedal, S.; Holliday, E.G.; Attia, J.; Brown, W.J.; Collins, C.E.; Ewald, B.; Glozier, N.; McEvoy, M.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; et al. Daily steps and diet, but not sleep, are related to mortality in older Australians. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paluch, A.E.; Gabriel, K.P.; Fulton, J.E.; Lewis, C.E.; Schreiner, P.J.; Sternfeld, B.; Sidney, S.; Siddique, J.; Whitaker, K.M.; Carnethon, M.R. Steps per Day and All-Cause Mortality in Middle-aged Adults in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2124516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.V.; Hildebrand, J.S.; Leach, C.R.; Campbell, P.T.; Doyle, C.; Shuval, K.; Wang, Y.; Gapstur, S.M. Walking in Relation to Mortality in a Large Prospective Cohort of Older U.S. Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Troiano, R.P.; Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Graubard, B.I.; Carlson, S.A.; Shiroma, E.J.; Fulton, J.E.; Matthews, C.E. Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity with Mortality among US Adults. JAMA 2020, 323, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Miyazaki, H.; Shimada, M.; Nakagawa, N.; Sawada, S.S.; Nishimuta, M.; Kimura, Y.; Kawakami, R.; Nagayama, H.; Asai, H.; et al. Daily step count and all-cause mortality in a sample of Japanese elderly people: A cohort study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, B.; Merom, D.; Blyth, F.M.; Naganathan, V.; Hirani, V.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Seibel, M.; Waite, L.M.; Handelsman, D.J.; Cumming, R. Total Physical Activity, Exercise Intensity, and Walking Speed as Predictors of All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Over 7 Years in Older Men: The Concord Health and Aging in Men Project. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Buring, J.E.; Miyachi, M.; Lee, I. Strength Training and All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer Mortality in Older Women: A Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e007677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Lee, D.-C.; Li, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, R.; Sui, X.; Lavie, C.J.; Blair, S.N. Associations of Resistance Exercise with Cardiovascular Disease Morbidity and Mortality. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.V.; Hodge, J.M.; Rees-Punia, E.; Teras, L.R.; Campbell, P.T.; Gapstur, S.M. Relationship between Muscle-Strengthening Activity and Cause-Specific Mortality in a Large US Cohort. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, A.K.; Cuthbertson, C.C.; Evenson, K.R. Participation in specific leisure-time activities and mortality risk among U.S. adults. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 50, 27–34.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, C.M.; Li, L. Associations of Exercise Types with All-Cause Mortality among U.S. Adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 2554–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, E.; Lee, I.-M.; Bennie, J.; Freeston, J.; Hamer, M.; O’donovan, G.; Ding, D.; Bauman, A.; Mavros, Y. Does Strength-Promoting Exercise Confer Unique Health Benefits? A Pooled Analysis of Data on 11 Population Cohorts with All-Cause, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality Endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, M.; Veeranki, S.P.; Magnussen, C.G.; Xi, B. Recommended physical activity and all cause and cause specific mortality in US adults: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020, 370, m2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segawa, H.; Kondo, K.; Kadota, A.; Yamauchi, H.; Ohno, S.; Tanaka-Mizuno, S.; Okuda, N.; Miyagawa, N.; Arima, H.; Okamura, T.; et al. Association of Red Meat Intake with the Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality in General Japanese Stratified by Kidney Function: NIPPON DATA80. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, A.; Stilling, F.; Wolk, A. High red meat intake and all-cause cardiovascular and cancer mortality: Is the risk modified by fruit and vegetable intake? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farvid, M.S.; Malekshah, A.F.; Pourshams, A.; Poustchi, H.; Sepanlou, S.G.; Sharafkhah, M.; Khoshnia, M.; Farvid, M.; Abnet, C.C.; Kamangar, F.; et al. Dietary Protein Sources and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: The Golestan Cohort Study in Iran. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Händel, M.N.; Cardoso, I.; Rasmussen, K.M.; Rohde, J.F.; Jacobsen, R.; Nielsen, S.M.; Christensen, R.; Heitmann, B.L. Processed meat intake and chronic disease morbidity and mortality: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Ouyang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Pan, A.; Hu, F.B. Red and processed meat consumption and mortality: Dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abete, I.; Romaguera, D.; Vieira, A.R.; Lopez de Munain, A.; Norat, T. Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farvid, M.S.; Sidahmed, E.; Spence, N.D.; Angua, K.M.; Rosner, B.A.; Barnett, J.B. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrmann, S.; Linseisen, J. Processed meat: The real villain? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 75, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’elia, L.; Rossi, G.; Ippolito, R.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Strazzullo, P. Habitual salt intake and risk of gastric cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, Z.; Cross, A.J.; Sinha, R. Meat, dairy, and cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100 (Suppl. S1), 386S–393S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Donnell, M.; Mente, A.; Yusuf, S. Sodium Intake and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Warnakula, S.; Kunutsor, S.; Crowe, F.; Ward, H.A.; Johnson, L.; Franco, O.; Butterworth, A.S.; Forouhi, N.; Thompson, S.G.; et al. Association of Dietary, Circulating, and Supplement Fatty Acids with Coronary Risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Neusner, A.; Longato, L.; Lawton, M.; Wands, J.R.; De La Monte, S.M. Nitrosamine exposure causes insulin resistance diseases: Relevance to type 2 diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2009, 17, 827–844. [Google Scholar]

- Micha, R.; Michas, G.; Mozaffarian, D. Unprocessed Red and Processed Meats and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease and Type 2 Diabetes—An Updated Review of the Evidence. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2012, 14, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gilchrist, M.; Shore, A.C.; Benjamin, N. Inorganic nitrate and nitrite and control of blood pressure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 89, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shan, Z.; Rehm, C.D.; Rogers, G.; Ruan, M.; Wang, D.D.; Hu, F.B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Zhang, F.F.; Bhupathiraju, S.N. Trends in Dietary Carbohydrate, Protein, and Fat Intake and Diet Quality among US Adults, 1999–2016. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 322, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chudasama, Y.V.; Khunti, K.; Gillies, C.L.; Dhalwani, N.N.; Davies, M.J.; Yates, T.; Zaccardi, F. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy in people with multimorbidity in the UK Biobank: A longitudinal cohort study. PLOS Med. 2020, 17, e1003332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brandt, P.A. The impact of a healthy lifestyle on the risk of esophageal and gastric cancer subtypes. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 37, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuori, I. Health benefits of physical activity with special reference to interaction with diet. Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.P.; Wai, J.P.M.; Tsai, M.K.; Yang, Y.C.; Cheng, T.Y.D.; Lee, M.-C.; Chan, H.T.; Tsao, C.K.; Tsai, S.P.; Wu, X. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2011, 378, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arem, H.; Moore, S.C.; Patel, A.; Hartge, P.; De Gonzalez, A.B.; Visvanathan, K.; Campbell, P.T.; Freedman, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H.O.; et al. Leisure Time Physical Activity and Mortality: A detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jayedi, A.; Gohari, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. Daily Step Count and All-Cause Mortality: A Dose–Response Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S. Impact of progressive resistance training on lipids and lipoproteins in adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyachi, M. Effects of resistance training on arterial stiffness: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Clayton, Z.S.; Zigler, M.C.; Richey, J.J.; Cuevas, L.M.; Rossman, M.J.; Battson, M.L.; Ziemba, B.P.; Hutton, D.A.; VanDongen, N.S.; et al. Lifelong voluntary aerobic exercise prevents age- and Western diet- induced vascular dysfunction, mitochondrial oxidative stress and inflammation in mice. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, G.A.; Bouchard, C. The biology of human overfeeding: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, C.; Rouillier, M.-A.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R.; Karelis, A.D. High Intensity Exercise: Can It Protect You from a Fast Food Diet? Nutrients 2017, 9, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez-Alvarez, I.; Zazpe, I.; de Rojas, J.P.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Hidalgo-Santamaría, M.; Martínez-González, M.A. Mediterranean diet, physical activity and their combined effect on all-cause mortality: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Prev. Med. 2018, 106, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Van Buskirk, J.; Nguyen, B.; Stamatakis, E.; Elbarbary, M.; Veronese, N.; Clare, P.J.; Lee, I.-M.; Ekelund, U.; Fontana, L. Physical activity, diet quality and all-cause cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality: A prospective study of 346 627 UK Biobank participants. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi Sinha, P.A.J.C.; Graubard, B.I.; Leitzmann, M.M.F.; Schatzkin, A. Meat Intake and Mortality a Prospective Study of over Half a Million People; American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Argyridou, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Davies, M.J.; Khunti, K.; Yates, T. Relevance of physical function in the association of red and processed meat intake with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M.L.; Robertson, A.S.; Jacobs, E.J.; Calle, E.E.; Thun, M.J. A Prospective Study of Diet and Stomach Cancer Mortality in United States Men and Women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2001, 10, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow, R.A.; Graubard, B.I.; Sinha, R.; Subar, A.F. Diet and lung cancer mortality: A 1987 National Health Interview Survey cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Dostal, A.; Menk, J.; Church, T.R. BMI Is a Risk Factor for Colorectal Cancer Mortality. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2511–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Calle, E.E.; Patel, A.V.; Thun, M.J. Predictors of pancreatic cancer mortality among a large cohort of United States adults. Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hayden, K.; Jackson, R.; Schutte, R. Association of red and processed meat consumption with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in participants with and without obesity: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3643–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siahpush, M.; Farazi, P.A.; Wang, H.; Robbins, R.E.; Singh, G.K.; Su, D. Muscle-strengthening physical activity is associated with cancer mortality: Results from the 1998–2011 National Health Interview Surveys, National Death Index record linkage. Cancer Causes Control 2019, 30, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year of Publication, Country | Age * | No. of Participants | Follow-Up (Years) † | No. of Deaths | Exposure | Exposure Assessment | Comparison of Meat Intake | Effect Size (95% CI) § | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhong, 2019, | 53.7 | 29,682 | 19 | 8875 | Red meat | FFQ | 2 vs. 0 servings/week | HR 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, |

| US | Processed | 2 vs. 0 servings/week | HR 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 12,13,14,15,16,17,18 | |||||

| Piet A, 2019, | 55–69 | M 58,279 | 10 | 5797 | Red meat | FFQ | 140.4 vs. 41.3 g/day | HR 1.02 (0.86–1.2) | 1,2,4,5,6,9,11,14,19,20, |

| The Netherlands | W 62,573 | 3026 | Processed | 30.8 vs. 0 g/day | HR 1.21 (1.02–1.44) | 21,22,23,24,25,26,27 | |||

| Zheng, 2019, | M 30–55 | 27,916 | 409,073 ** | 5593 | Red meat | FFQ | >0.5/change of <0.15 serving/day | HR 1.10 (1.04–1.17) | 1,3,6,8,9,21,22,23,24,28 |

| US | W 40–75 | 53,553 | 804,685 ** | 8426 | Processed | >0.5/change of <0.15 serving/day | HR 1.13 (1.04–1.23) | 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 | |

| Alshahrani, | >25 | 72,149 | 11.8 | 7961 | Red meat | FFQ | 41.7 vs. 4 g/day | HR 1.17 (1.05–1.32) | 1,2,3,4,5,6,9,18,21,22, |

| 2019, US | Processed | 9.4 vs. 0.7 g/day | HR 1.16 (1.04–1.29) | 24,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 | |||||

| and Canada | Combined | 42.8 vs. 1.4 g/day | HR 1.25 (1.12–1.40) | 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,4647,48 | |||||

| Mejborn, 2020, | 15–75 | 9848 | NR | 640 | Red meat | 7-day pre-coded | >97 vs. <41 g/day | HR 0.86 (0.67–1.12) | 2,3,4,5,6,8,9,24 |

| Denmark | Processed | food diary | >58 vs. <19 g/day | HR 1.02 (0.82–1.26) | |||||

| Argyridou, 2019, UK | 40–69 | 419,075 | 7 | 15,058 | Combined | FFQ | 7.0 vs. 1.5 servings/week | HR 1.252 (1.172–1.338) | 1,2,3,4,6,8,9,11,14,24, 47,48,49,50,51,52 |

| Dominguez, | >45 | 18,540 | 9.5 | 255 | Red meat | 136-item | >7 vs. <3 servings/week | HR 1.86 (1.19–2.93) | 2,4,5,6,9,24,25,53,56, |

| 2017, | Processed | FFQ | >7 vs. <3 servings/week | HR 1.57 (0.76–3.24) | 74,82,83,84 | ||||

| Spain | Combined | >7 vs. <3 servings/week | HR 1.31 (0.75–2.30) | ||||||

| Etemadi, | 50–71 | M 316,505 | 15.6 | 84,848 | Red meat | 124-item | 50.3 vs. 6.9 g/1000 kcal | HR 1.20 (1.17–1.22) | 1,2,3,4,5,6,8,9,11,14,24, |

| 2017, US | W 220,464 | 43,676 | Processed | FFQ | 17.2 vs. 2.3 g/1000 kcal | HR 1.15 (1.13–1.17) | 29,30,37,54,55,56,57,58 | ||

| Sheehy, | 38 | W 56,314 | 22 | 5054 | Red meat | FFQ | 1.0 vs. 0.01 serving/day | HR 1.47 (1.33–1.62) | 4,5,6,8,21,24,28,30,60, |

| 2020, US | Processed | 1.2 vs. 0.01 serving/day | HR 1.40 (1.28–1.55) | 61,62 | |||||

| Saito, | 45–74 | M 40,072 | 14 | 6266 | Red meat | FFQ | 92.9 vs. 14.3 g/d | HR 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | 1,5,6,9,11,14,15,16,18, |

| 2020, Japan | Processed | 8.4 vs. 1.3 g/d | HR 0.98 (0.91–1.07) | 21,22,24,47,63,64,65 | |||||

| W 47,435 | 3620 | Red meat | 90.3 vs. 13.6 g/d | HR 1.08 (0.95–1.24) | |||||

| Processed | 11.7 vs. 2.1 g/d | HR 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | |||||||

| Rohrmann, | 35–69 | 448,568 | 12.7 | 26,344 | Red meat | FFQ | 160+ vs. 10–19.9 g/d | HR 1.10 (0.98–1.24) | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,24,31,59 |

| 2013, Europe | Processed | 160+ vs. 10–19.9 g/d | HR 1.43 (1.24–1.64) | ||||||

| Sinha, | 50–71 | 500,000 | 10 | M 47,976 | Red meat | 124-item | 68.1 vs. 9.3 g/1000 kcal | HR 1.31 (1.27–1.35) | 4,6,8,9,11,14,19,24,26 |

| 2009, US | Processed | FFQ | 19.4 vs. 5.1 g/1000 kcal | HR 1.16 (1.12–1.19) | 30,37,66 | ||||

| W 23,276 | Red meat | 65.9 vs. 9.1 g/1000 kcal | HR 1.36 (1.30–1.43) | ||||||

| Processed | 16.0 vs. 3.8 g/1000 kcal | HR 1.25 (1.20–1.31) | |||||||

| Pan, | NA | M 37,698 | 22 | M 8926 | Red meat | FFQ | 2.36 vs. 0.22 servings/day | HR 1.29 (1.20–1.38) | 1,3,5,6,8,9,11,14,21,22, |

| 2012, US | Processed | 2.36 vs. 0.22 servings/day | HR 1.27 (1.19–1.36) | 24,28,29,30,34,35,36,43 | |||||

| Combined | 2.36 vs. 0.22 servings/day | HR 1.37 (1.27–1.47) | |||||||

| W 83,644 | 28 | W 15,000 | Red meat | 3.1 vs. 0.53 servings/day | HR 1.19 (1.13–1.25) | ||||

| Processed | 3.1 vs. 0.53 servings/day | HR 1.20 (1.14–1.27) | |||||||

| Combined | 3.1 vs. 0.53 servings/day | HR 1.24 (1.17–1.30) | |||||||

| Takata, | 40–74 | M 61,483 | 334,281 ** | 2733 | Red meat | FFQ | 114.9 vs. 20.0 g/day | HR 1.18 (1.02–1.35) | 1,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,14,47, |

| 2013, China | W 74,941 | 803,265 ** | 4210 | Red meat | 94.8 vs. 15.0 g/day | HR 0.92 (0.82–1.03) | 48,59,67,68,69 | ||

| Bellavia, 2016, | 45–83 | M 40,089 | 16 | 10,423 | Red meat | FFQ | 140 vs. 31 g/day | HR 1.21 (1.13–1.29) | 2,4,5,7,8,9,22,24,47 |

| Sweden | W 34,556 | 7486 | |||||||

| Kappeler, 2013, US | >18 | 17,611 | 22 | M 1908 | Red meat Processed | FFQ | 45+ vs. 0–6 times/week 45+ vs. 0–6 times/week | HR 1.24 (0.76–2.02) HR 1.06 (0.75–1.50) | 1,2,3,6,8,9,11,14,21,22,24,26,29,32,35,36,37,61 |

| W 1775 | Red meat | 45+ vs. 0–6 times/week | HR 1.49 (0.76–2.94) | 73,74 | |||||

| Processed | 45+ vs. 0–6 times/week | HR 1.16 (0.86–1.55) | |||||||

| Lee, 2013, | 17–92 | M 112,310 | 6.6–15.5 | 23,515 | Red meat | FFQ | Q4/Q1 | HR 0.93 (0.84–1.02) | 1,4,5,6,9,11,14,24,76 |

| Asian | W 184,411 | 16,699 | Red meat | Q4/Q1 | HR 0.93 (0.86–1.00) | ||||

| Whiteman, | 35–64 | 10,522 | 9 | 514 | Red meat | FFQ | 4–7 vs. <1 day week-1 | HR 0.71 (0.55–0.92) | 1,2,6 |

| 1999, UK | Processed | 4–7 vs. <1 day week-1 | HR 1.05 (0.62–1.76) | ||||||

| Farvid, 2016, Iran | 51.6 | 42,403 | 11 | 3291 | Red meat | 0.43 vs. 0.02 serving/day | HR 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 1,2,3,4,5,6,8,9,24,30,37,51,70,76 | |

| Iqbal, 2021, | 35–70 | 134,297 | 9.5 | 7789 | Red meat | FFQ | ≥250/<50 g/week | HR 0.93 (0.85, 1.02) | 1,2,4,5,6,8,11,12,14, |

| 21 countries | Processed | ≥250/<50 g/week | HR 1.51 (1.08, 2.10) | 41,22,78,79,80 | |||||

| Sun, 2021, | 50–79 | 102,521 | 18.1 | 25,976 | Red meat | FFQ | 3.2/0.3 oz equivalent/d | HR 1.05 (0.99–1.10) | 1,3,4,5,6,8,9,11,14,17 |

| US | Processed | 1.0/0.01 oz equivalent/d | HR 1.06 (1.01–1.10) | 22,41,43,67,71,74,81 | |||||

| Combined | 3.9/0.4 oz equivalent/d | HR 1.10 (1.05–1.15) |

| Author, Year of Publication, Country | Age * | Sample size | Follow-Up (Years) † | No. of Cases | Exposure | Exposure Assessment | Comparison of Meat Intake | Effect Size (95% CI) § | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao, 2020, | ≥18 | 479,856 | 8.75 | 59,819 | MSA | Self-reported | <2 times/week | HR 1 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| US | ≥2 times/week | HR 0.89 (0.85–0.94) | |||||||

| Stamatakis, | ≥19 | 72,459 | 9.2 | 5763 | Strength- | Questionnaire | None | HR 1 | 1,2,4,6,7,8,11,12 |

| 2017, UK | promoting exercise | Any | HR 0.77 (0.69–0.87) | ||||||

| Kamada, 2017, | 62.2 | 28,879 | 12 | 3055 | Strength | Questionnaire | 0 | RR 1 | 2,3,4,6,7,8,13,14,15,16, |

| US | (Mean) | training | ≥150 min/week | RR 1.10 (0.77–1.56) | 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 | ||||

| LIU, 2018, US | 18–89 | 12,591 | 10 | 276 | Resistance | Questionnaire | 0 | HR 1 | 1,2,6,7,8,24,27,29,30 |

| exercise | ≥120 min/week | HR 1.03 (0.59–1.80) | |||||||

| Patel, | 70.2 | 72,462 | 13 | 17,750 | MSA | Questionnaire | 0 | HR 1 | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,31,32,33, |

| 2020, US | ≥2 h/week | HR 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 34,35,36,37 | ||||||

| Porter, 2020, | 46.3 | 17,938 | 11.9 | 3799 | Weightlifting | Questionnaire | No | HR 1 | 1,2,3,4,6,7,8,38 |

| US | (Mean) | Yes | HR 0.89 (0.67–1.17) | ||||||

| Hsu, 2017, | ≥70 | 1705 | 7 | 519 | Muscle- | Questionnaire | No | HR 1 | 2,3,4,6,7,8,26,27,36,50, |

| Australia | strengthening exercise | Yes | HR 0.72 (0.49–1.06) | 51,52,53 | |||||

| Sheehan, | 18–84 | 26,727 | 17 | 4955 | Weightlifting | Questionnaire | No | HR 1 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,50,51,54, |

| 2020, US | Yes | HR 0.95 (0.85–1.07) | 55,56,57 |

| Author, Country | Age * | Sample Size | Follow-Up (Years) † | No. of Cases | Exposure | Exposure Assessment | Number of Steps per Day | Effect Size (95% CI) § | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee, 2019, US | ≥45 | 16,741 | 4.3 | 504 | Steps | ActiGraph | 2718 | HR 1 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, |

| GT3X+ accelerometers | 4363 | HR 0.59 (0.47–0.75) | 13,14 | ||||||

| 5905 | HR 0.54 (0.41–0.72) | ||||||||

| 8442 | HR 0.42 (0.3–0.6) | ||||||||

| Hansen, 2020, | 57 | 2183 | 9.1 | 119 | Steps | ActiGraph, LLC, | 4651 | HR 1 | 2,3,4,15,16,21,22,23 |

| Norway | Pensacola, FL | 6862 | HR 0.52 (0.29–0.93) | ||||||

| 8670 | HR 0.5 (0.27–0.94) | ||||||||

| 11,467 | HR 0.43 (0.21–0.88) | ||||||||

| Maurice, 2020, | 56.8 | 4840 | 10.1 | 1165 | Steps | ActiGraph 7164 | 4000 | HR 1 | 1,3,4,12.15.16.22,24,26,27, |

| US | 8000 | HR 0.49 (0.44–0.55) | 28,29,30 | ||||||

| 12,000 | HR 0.35 (0.28–0.45) | ||||||||

| Jefferis, 2017, UK | 78.4 | 1181 | 5 | 194 | Steps | ActiGraph GT3x | 1895 | HR 1 | 1,2,3,4,22,25,33,34,35, |

| 3646 | HR 0.63 (0.43–1.54) | 36,37 | |||||||

| 5302 | HR 0.59 (0.39–0.9) | ||||||||

| 8401 | HR 0.31 (0.17–0.57) | ||||||||

| Yamamoto, 2018, | 71 | 419 | 9.8 | 76 | Steps | spring-levered | 3394 | HR 1 | 3,4,15,22,23 |

| Japan | pedometer (EC-100S, | 5310 | HR 0.81 (0.43–1.54) | ||||||

| YAMASA, Tokyo, | 6924 | HR 1.26 (0.7–2.26) | |||||||

| Japan) | 10,241 | HR 0.46 (0.22–0.96) | |||||||

| Oftedal, 2019, Australia | 65.4 | 1697 | 9.6 | NR | Steps | DigiwalkerSW-200 pedometer | Per 1000 steps per day | HR 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 1,3,15,38 |

| Dwyer, 2015, | 58.8 | 2576 | 10 | 219 | Steps | Omron HJ-003 | 0–5550 | HR 1 | 1,3,4,15,22,39 |

| Australia | Omron HJ-102 | 5551–8000 | HR 0.43 (0.30–0.62) | ||||||

| 8001–10,000 | HR 0.25 (0.16–0.38) | ||||||||

| 10,001–13,500 | HR 0.24 (0.15–0.37) | ||||||||

| 13,501–39,164 | HR 0.10 (0.05–0.18) | ||||||||

| Manas, 2021, Spain | 78.8 | 768 | 5.7 | 89 | Steps | ActiTrainer ActiGraphwGT3X-BT; ActiGraph, Pensacola, | per additional 1000 steps | HR 0.87 (0.81–0.95) | 1,2,15,16,22,38,40,41 |

| Paluch, 2021, US | 45.2 | 2110 | 10.8 | 72 | Steps | ActiGraph 7164 | 5837 | HR 1 | 1,2,3,4,12,13,15,16,22,23, |

| 8502 | HR 0.28 (0.15–0.54) | 25,26,42,43,44 | |||||||

| 11,815 | HR 0.45 (0.25–0.81) | ||||||||

| Klenk, 2016, US | 75.6 | 1271 | 4 | 100 | Walking duration | activPAL, PAL Technologies Ltd., Glasgow, UK | 128.4–290.5 vs. 3.7–76.1 min/day | HR 0.39 (0.19–0.78) | 1,3,4,13,14,15,16,22,26,31,44 |

| Pate, 2017, US | 69.8 | 139,255 | 13 | 43,621 | Walking duration | assessed by asking | >6 h/week vs. <2 h/week | HR 0.78 (0.75–0.81) | 4,7,8,25,26,39,40,45,46,47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Wang, M.; Long, Z.; Ye, J.; Cao, Y.; Pei, B.; Gao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, F.; et al. How to Keep the Balance between Red and Processed Meat Intake and Physical Activity Regarding Mortality: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153373

Wu Y, Wang M, Long Z, Ye J, Cao Y, Pei B, Gao Y, Yu Y, Han Z, Wang F, et al. How to Keep the Balance between Red and Processed Meat Intake and Physical Activity Regarding Mortality: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2023; 15(15):3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153373

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yi, Maoqing Wang, Zhiping Long, Jingyu Ye, Yukun Cao, Bing Pei, Yu Gao, Yue Yu, Zhen Han, Fan Wang, and et al. 2023. "How to Keep the Balance between Red and Processed Meat Intake and Physical Activity Regarding Mortality: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 15, no. 15: 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153373

APA StyleWu, Y., Wang, M., Long, Z., Ye, J., Cao, Y., Pei, B., Gao, Y., Yu, Y., Han, Z., Wang, F., & Zhao, Y. (2023). How to Keep the Balance between Red and Processed Meat Intake and Physical Activity Regarding Mortality: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 15(15), 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153373