Abstract

Background: We aimed to investigate the association between the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio and post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) in patients with acute stroke of large artery atherosclerosis etiology. Methods: Prospective stroke registry data were used to consecutively enroll patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large artery atherosclerosis. Cognitive function assessments were conducted 3 to 6 months after stroke. PSCI was defined as a z-score of less than −2 standard deviations from age, sex, and education-adjusted means in at least one cognitive domain. The ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was calculated, and patients were categorized into five groups according to quintiles of the ratio. Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the association between quintiles of the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio and PSCI. Results: A total of 263 patients were included, with a mean age of 65.9 ± 11.6 years. The median NIHSS score and ApoB/ApoA-I ratio upon admission were 2 (IQR, 1–5) and 0.81 (IQR, 0.76–0.88), respectively. PSCI was observed in 91 (34.6%) patients. The highest quintile (Q5) of the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was a significant predictor of PSCI compared to the lowest quintile (Q1) (adjusted OR, 3.16; 95% CI, 1.19–8.41; p-value = 0.021) after adjusting for relevant confounders. Patients in the Q5 group exhibited significantly worse performance in the frontal domain. Conclusions: The ApoB/ApoA-I ratio in the acute stage of stroke independently predicted the development of PSCI at 3–6 months after stroke due to large artery atherosclerosis. Further, a high ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was specifically associated with frontal domain dysfunction.

1. Introduction

Post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality following acute stroke [1,2,3,4]. Cognitive deficits are observed in up to 70% of post-stroke survivors, with variations depending on factors such as the study population, definition of cognitive impairment, assessment methods, and timing of evaluation [5,6]. PSCI can occur after acute ischemic stroke of various etiologies, including small vessel disease, large artery atherosclerosis, and cardioembolism, among others. While several modifiable risk factors, such as characteristics of the index stroke, vascular risk factors, and underlying brain health, contribute to the development of PSCI [7], the identification of biomarkers for predicting PSCI remains an active area of research [8,9,10].

Although dyslipidemia and conventional lipid profiles, including total cholesterol [11], low-density lipoprotein [12], and high-density lipoprotein, have been extensively studied as vascular risk factors, their association with PSCI has yielded inconsistent results in previous cohort studies [13,14,15]. On the other hand, recent research has suggested that specific atherogenic lipoproteins, such as apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), and their ratio may play significant roles in both cognitive function [16] and atherosclerotic stroke [17,18,19]. ApoB is known to generate pro-inflammatory products and exacerbate atherosclerosis in arterial walls [20], while ApoA-I, a major component of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects and facilitates the transport of cholesterol from the bloodstream to the liver [21,22]. Hence, the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio may serve as a more robust biomarker for predicting both atherosclerotic stroke [23,24] and subsequent cognitive status compared to other cholesterol measures [25].

Based on these considerations, we hypothesized that a high ApoB/ApoA-I ratio may be associated with worse cognitive outcomes following stroke. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to investigate the association between the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio and PSCI in patients with acute stroke of large artery atherosclerosis etiology. Additionally, we aim to explore whether the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio is associated with domain-specific cognitive deficits, providing further insights into the underlying mechanisms of PSCI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This study employed a retrospective cross-sectional design based on a prospective stroke registry. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients or their legal representatives to use clinical data. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB No.2021-02-010).

We consecutively enrolled patients with acute ischemic stroke who were hospitalized in our hospital. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) consecutive ischemic stroke patients with relevant ischemic lesions on the diffusion-weighted image (DWI) between January 2011 and December 2020, (2) admission within 7 days of symptom onset, (3) large artery atherosclerosis etiology according to the Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria [26], (4) no history of statin or other lipid-lowering agent use before the index stroke, and (5) availability of neuropsychological battery results 3 to 6 months after stroke onset. Patients with a pre-stroke diagnosis of dementia or a premorbid modified Rankin scale score of more than two were excluded. Patients with global aphasia, hearing difficulty, poor cooperation, or severe neurological deficits that precluded the administration of the neuropsychological battery were also excluded.

2.2. Main Exposure and Covariates

Baseline demographics, including age, sex, body mass index, and education level, were collected from the prospective stroke registry. A history of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, smoking status, and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack was recorded. Index stroke characteristics, including initial stroke severity assessed by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score and stroke etiology according to the TOAST classification, were documented. Fasting blood samples were collected on the day after admission for lipid profile assessment, including apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein A-I, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, as well as other serum biochemical indicators. The ApoB/ApoA-I ratio, the main exposure variable, was divided into quintiles, with Q1 serving as the reference category.

All participants underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using either a 1.5 T or 3 T system based on the year of admission. Lesion laterality, multiplicity, and volume were determined using DWI. Lesion locations were further categorized as cortical, subcortical, or infratentorial. Strategic lesion locations were defined as involvement of the hippocampus, basal ganglia, caudate nucleus, thalamus, inferomedial temporal gyrus, and angular gyrus. The burden of small vessel diseases was evaluated based on the degree of white matter hyperintensities using the modified Fazekas scale [27] and the presence of chronic microbleeds in the lobar or deep locations. Medial temporal lobe atrophy was assessed using Schelten’s scale [28].

2.3. Neuropsychological Evaluation and Outcome Variables

All participants underwent the 60 min Korean version of the Vascular Cognitive Impairment Harmonization Standards-Neuropsychological Protocol (K-VCIHS-NP) at 3 to 6 months after stroke onset. The K-VCIHS-NP assessed four cognitive domains: memory, frontal/executive function, language, and visuospatial function. The specific details of each neuropsychological test corresponding to the four cognitive domains are provided in Supplemental Table S1. Additionally, participants completed the Korean versions of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (K-MMSE) [29] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (K-MoCA) [30] to evaluate their general cognitive status. All cognitive batteries used in the K-VCIHS-NP, K-MMSE, and K-MoCA were standardized and validated for use in the Republic of Korea. To account for variations in age, sex, and education, raw scores were transformed into z-scores before analysis. The premorbid cognitive status of each participant was assessed using the Korean version of the Informed Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE), with a cutoff value of 3.6, indicating the presence of premorbid cognitive decline [31]. The primary outcome of interest in this study was the development of post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI), defined as having a z-score of less than −2 standard deviations in at least one cognitive domain.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviation or medians with interquartile range, depending on their distribution. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and frequencies. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between the normal cognition group and the PSCI group using appropriate statistical tests. Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables, while the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was employed for categorical variables. To examine the differences in clinical characteristics among quintiles of ApoB/ApoA-I, analysis of variance, the Kruskal–Wallis test, or the chi-square test was applied, as appropriate. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate the association between the quintiles of ApoB/ApoA-I and PSCI, using Q1 as the reference value. Multivariable models were adjusted for prespecified demographic variables, including age, sex, and education, as well as variables with a p-value less than 0.2 in the univariate analysis. Odds ratios (OR) or adjusted odds ratios (aOR), along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), were reported to demonstrate the associations. For the secondary analysis, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to compare the z-scores of each cognitive domain and global cognitive functions among quintiles of ApoB/ApoA-I, adjusting for age, sex, and education level. All statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 4.3.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and a two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

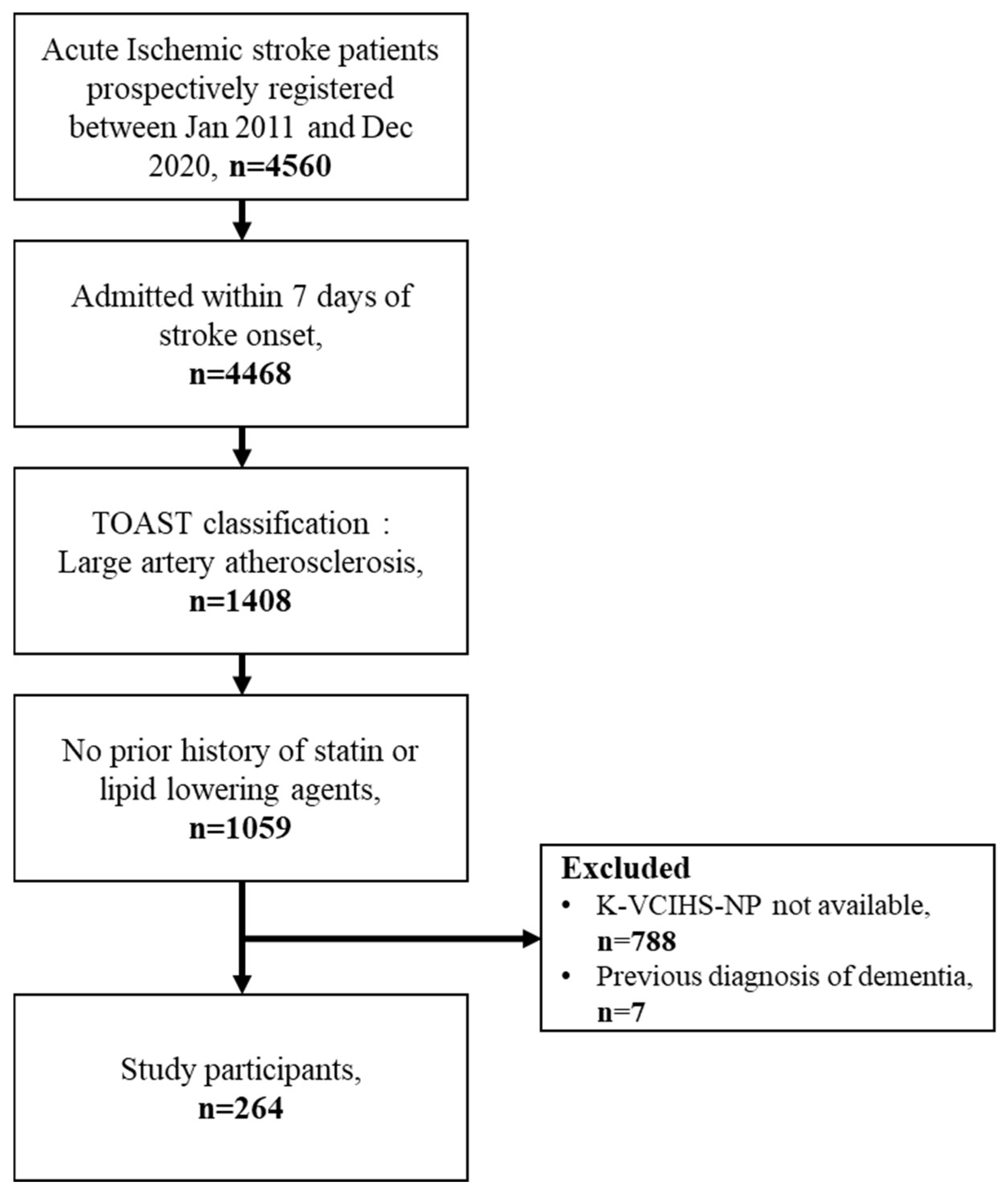

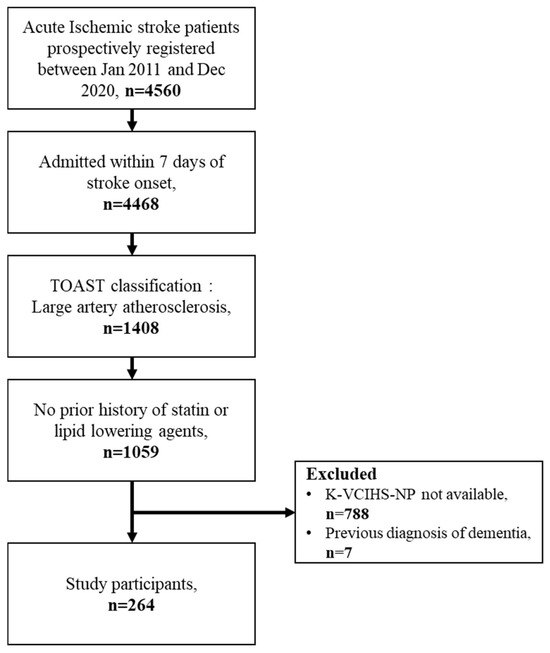

Among the 4560 acute ischemic stroke patients assessed during the study period, a total of 1408 patients were identified as having large artery atherosclerosis. Among these patients, 1059 were determined to be naive to statin or other lipid-lowering agents. Finally, after excluding patients with a previous diagnosis of dementia and those who did not undergo the K-VCIHS-NP assessment at 3 to 6 months, 264 patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The included patients had a mean age of 65.9 ± 11.6 years. Upon admission, the median NIHSS score was 2 (interquartile range, IQR: 1–5), and the median ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was 0.814 (IQR: 0.762–0.884). Overall, PSCI was observed in 91 out of the 264 patients (34.6%) at the 3 to 6 months after stroke onset.

Figure 1.

The study flowchart.

The baseline characteristics of the study participants according to the ApoB/ApoA-I quintile groups are summarized in Table 1. The only significant differences observed were in the frequency of a history of dyslipidemia and the level of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein. No other significant differences were found among the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients According to the ApoB/ApoAI Ratio Quintile Groups.

Table 2 presents the differences between the group without cognitive impairment and those who developed PSCI. Participants with PSCI had higher NIHSS scores, larger stroke volume, a higher smoking tendency, and were more likely to have cortical or strategic lesions. On the other hand, they were less likely to have infratentorial lesions. Furthermore, PSCI patients exhibited a higher burden of white matter changes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics according to the presence of PSCI.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the highest quintile (Q5) of the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was found to be significantly associated with the development of PSCI at 3 to 6 months after stroke compared with Q1 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.00; 95% CI, 1.10–8.20). The adjusted covariates included age, sex, education levels, BMI, systolic blood pressure, previous history of diabetes, smoking, fasting blood sugar, initial stroke severity, stroke volume, presence of cortical, infratentorial or strategic lesions, modified Fazekas scale, and total medial temporal lobe atrophy (MTLA) scores. Among these variables, fasting blood sugar, stroke volume, presence of strategic lesions, and modified Fazekas scale grade 3 were significantly associated with PSCI after adjustment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis for the predictors of PSCI.

We also compared the z-scores of each cognitive domain and global cognitive functions among the quintile groups of ApoB/ApoA-I. While the z-scores and raw scores of the K-MMSE and K-MoCA were not significantly different between the groups, the z-scores of the frontal domain showed significant differences and tended to be lower in the Q5 group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Domain-specific outcome according to the ApoB/ApoAI ratio using ANCOVA analysis.

4. Discussion

The present study revealed several interesting findings. First, among acute ischemic stroke patients with large artery atherosclerosis, a substantial proportion (34.6%) developed PSCI within 3 to 6 months after the stroke. Second, the highest quintile (Q5) of the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was associated with a three-fold increased risk of developing PSCI compared to the reference group (Q1). Furthermore, the study revealed an association between a higher ApoB/ApoA-I ratio and frontal domain dysfunctions.

The underlying mechanisms that contribute to PSCI are multifaceted and remain incompletely elucidated. However, it is postulated that they encompass a blend of immediate neuronal damage instigated by the stroke alongside more indirect influences such as sustained inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction [15,32]. The ApoB/ApoA-I ratio, a measure of the balance between atherogenic and anti-atherogenic lipoproteins, emerged as a significant predictor of PSCI in our study. The biological plausibility of this association is supported by the known roles of ApoB and ApoA-I in vascular health and inflammation [33,34,35]. Previous research has suggested that ApoB, the primary protein in low-density lipoprotein (LDL), contributes to atherogenesis and inflammation [36], while ApoA-I, a key component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, and promotes vascular health [37]. Consistent with this understanding, existing literature has underscored that elevated ApoB, diminished ApoA-I, and an increased ApoB/ApoA-I ratio are robust indicators of both cardiovascular diseases [38] and dementia [16] in the general population. Consequently, an elevated ApoB/ApoA-I ratio, which signifies a state of enhanced inflammation, oxidation, and atherogenesis, could potentially augment neuronal damage subsequent to a stroke, thereby precipitating cognitive impairment. Our previous investigations have also demonstrated a connection between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, an indirect indicator of systemic inflammation, and the incident PSCI [9]. Additionally, we have established that the state of malnutrition, which is intimately linked with pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory conditions, plays a role in the deterioration of cognitive functions following a stroke [8]. This study found that the highest quintile of the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was associated with a three-fold increased risk of developing PSCI, reinforcing the potential role of this lipid imbalance in post-stroke cognitive outcomes.

Moreover, the study unveiled an intriguing association between a higher ApoB/ApoA-I ratio and frontal domain dysfunctions. The frontal lobes of the brain are responsible for executive functions, decision-making, and attentional control, which are critical for daily living activities [39]. This suggests that the vascular damage and inflammation associated with an elevated ApoB/ApoA-I ratio may specifically affect these cognitive functions. Our finding aligns with existing literature that links vascular risk factors with the development of vascular cognitive impairment and vascular dementia, where executive dysfunction is a prominent feature [7,39].

Our study has important clinical implications. The identification of the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio as a significant predictor of PSCI could enable better risk stratification of cognitive impairment for stroke patients and provide a target for interventions to prevent PSCI. Since lifestyle factors and specific medications can influence both ApoB and ApoA-I, interventions aiming at optimizing the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio could potentially reduce the risk of PSCI. This hypothesis needs to be tested in future clinical trials.

This study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the exclusion of acute stroke patients with severe neurological deficits or aphasia who were unable to undergo the neuropsychological battery may limit the generalizability of the findings to the entire acute stroke population. This exclusion could introduce a bias in the study sample, and caution should be exercised when interpreting the results. Further, an additional potential limitation of our study is the homogeneity of our sample, as all subjects were recruited from a single tertiary university hospital. This restricts the generalizability of our findings to broader populations that may be represented in different institutions or geographical locations. Second, the study design was cross-sectional and observational in nature, which prevents the establishment of a causal association between the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio and the development of PSCI. While significant associations were observed, it is important to recognize that causality cannot be inferred from this study alone. Further prospective studies or randomized controlled trials are needed to explore the causal relationship between dyslipidemia, ApoB/ApoA-I ratio, and PSCI. Despite these limitations, this study provides important preliminary evidence regarding the association between the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio and the development of PSCI in patients with large artery atherosclerosis. Future studies addressing these limitations and investigating potential mechanisms underlying this association would contribute to a better understanding of the role of lipid profiles in PCSI.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides evidence that the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio at the acute stage of ischemic stroke is independently associated with the development of PSCI at 3 to 6 months in patients with large artery atherosclerosis. Specifically, a higher ApoB/ApoA-I ratio is associated with frontal domain dysfunction. These findings have implications for understanding the underlying pathophysiology of PSCI and may potentially impact the management and treatment of cognitive impairment following stroke.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu15214670/s1, Supplemental Table S1. Korean version of the 60 min Vascular Cognitive Impairment Harmonization Standards-Neuropsychology Protocol. References [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.; methodology, M.L.; software, M.L.; validation, M.S.O.; formal analysis, M.L.; investigation, M.L.; resources, M.L.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.; writing—review and editing, J.-S.L., Y.K., S.H.P., S.-H.L., C.K., B.-C.L. and K.-H.Y.; visualization, M.L.; supervision, J.-S.L. and M.S.O.; project administration, M.S.O.; funding acquisition, J.-J.L., M.S.O. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Bio&Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF), funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00223501) and by a fund (2023-ER0903-00) by Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB No.2021-02-010).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients or their legal representatives to use clinical data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gorelick, P.B.; Scuteri, A.; Black, S.E.; Decarli, C.; Greenberg, S.M.; Iadecola, C.; Launer, L.J.; Laurent, S.; Lopez, O.L.; Nyenhuis, D.; et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2011, 42, 2672–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, D.; Henon, H.; Mackowiak-Cordoliani, M.A.; Pasquier, F. Poststroke dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005, 4, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, S.T.; Rothwell, P.M. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.T. Post-stroke cognitive impairment: Epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, S.T.; Rothwell, P.M.; Oxford Vascular, S. Incidence and prevalence of dementia associated with transient ischaemic attack and stroke: Analysis of the population-based Oxford Vascular Study. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, E.; McLoughlin, A.; Williams, D.J.; Merriman, N.A.; Donnelly, N.; Rohde, D.; Hickey, A.; Wren, M.A.; Bennett, K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of cognitive impairment no dementia in the first year post-stroke. Eur. Stroke J. 2019, 4, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, J.W.; Crawford, J.D.; Desmond, D.W.; Godefroy, O.; Jokinen, H.; Mahinrad, S.; Bae, H.J.; Lim, J.S.; Kohler, S.; Douven, E.; et al. Profile of and risk factors for poststroke cognitive impairment in diverse ethnoregional groups. Neurology 2019, 93, e2257–e2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lim, J.S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, M.U.; Oh, M.S.; Lee, B.C.; Yu, K.H. Association between Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index and Post-Stroke Cognitive Outcomes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lim, J.S.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Hun Lee, J.; Jang, M.U.; Sun Oh, M.; Lee, B.C.; Yu, K.H. High Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio Predicts Post-stroke Cognitive Impairment in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 693318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Lim, J.S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, M.U.; Oh, M.S.; Lee, B.C.; Yu, K.H. Effects of Glycemic Gap on Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.; Ski, C.F.; Thompson, D.R.; Linden, T. Serum cholesterol, body mass index and smoking status do not predict long-term cognitive impairment in elderly stroke patients. J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 406, 116476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.Y.; Shin, K.Y.; Chang, K.A. Potential Biomarkers for Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Liu, C.; Gao, Y.; Sun, D. Serum TG/HDL-C level at the acute phase of ischemic stroke is associated with post-stroke cognitive impairment. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 5977–5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Ding, M.; Cui, M.; Fang, M.; Gong, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Development and validation of a clinical model (DREAM-LDL) for post-stroke cognitive impairment at 6 months. Aging 2021, 13, 21628–21641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, N.S.; Brodtmann, A.; Pase, M.P.; van Veluw, S.J.; Biffi, A.; Duering, M.; Hinman, J.D.; Dichgans, M. Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1252–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Harris, K.; Peters, S.A.E.; Woodward, M. Serum lipid traits and the risk of dementia: A cohort study of 254,575 women and 214,891 men in the UK Biobank. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Song, Z.; Cui, X.; Liu, L.; Ding, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, R.; Zhu, X.; et al. Elevated ApoB/ApoA-Iota ratio is associated with poor outcome in acute ischemic stroke. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 107, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zuo, H. Association of the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio with stroke risk: Findings from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS). Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Hong, K.S.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.E. High levels of apolipoprotein B/AI ratio are associated with intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis. Stroke 2011, 42, 3040–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D.; Faraj, M. Apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein A-I, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2007, 18, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielicki, J.K.; Oda, M.N. Apolipoprotein A-I(Milano) and apolipoprotein A-I(Paris) exhibit an antioxidant activity distinct from that of wild-type apolipoprotein A-I. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 2089–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, S.E.; Tsunoda, T.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Schoenhagen, P.; Cooper, C.J.; Yasin, M.; Eaton, G.M.; Lauer, M.A.; Sheldon, W.S.; Grines, C.L.; et al. Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003, 290, 2292–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmy, E.M.; El Awady, M.A.E.S.; Sharaf, S.A.-A.; Selim, N.M.; Abdo, H.E.S.; Mohammed, S.S. Apolipoproteins A1 and B and their ratio in acute ischemic stroke patients with intracranial and extracranial arterial stenosis: An Egyptian study. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2020, 56, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostapanos, M.S.; Christogiannis, L.G.; Bika, E.; Bairaktari, E.T.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Elisaf, M.S.; Milionis, H.J. Apolipoprotein B-to-A1 ratio as a predictor of acute ischemic nonembolic stroke in elderly subjects. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2010, 19, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walldius, G.; Jungner, I. The apoB/apoA-I ratio: A strong, new risk factor for cardiovascular disease and a target for lipid-lowering therapy—A review of the evidence. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 259, 493–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.P., Jr.; Bendixen, B.H.; Kappelle, L.J.; Biller, J.; Love, B.B.; Gordon, D.L.; Marsh, E.E., 3rd. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993, 24, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, F.; Kleinert, R.; Offenbacher, H.; Schmidt, R.; Kleinert, G.; Payer, F.; Radner, H.; Lechner, H. Pathologic correlates of incidental MRI white matter signal hyperintensities. Neurology 1993, 43, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheltens, P.; Leys, D.; Barkhof, F.; Huglo, D.; Weinstein, H.C.; Vermersch, P.; Kuiper, M.; Steinling, M.; Wolters, E.C.; Valk, J. Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in “probable” Alzheimer’s disease and normal ageing: Diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1992, 55, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Na, D.L.; Hahn, S. A validity study on the korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J. Korean Neurol. Assoc. 1997, 15, 300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Park, J.S.; Yu, K.H.; Lee, B.C. A Reliability, Validity, and Normative Study of the Korean-Montreal Cognitive Assessment(K-MoCA) as an Instrument for Screening of Vascular Cognitive Impairment(VCI). Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 28, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H. Informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE) for classifying cognitive dysfunction as cognitively normal, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Ji, X.; Liu, J. Neuroinflammation in Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Current Evidence, Advances, and Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D.; St-Pierre, A.C.; Cantin, B.; Dagenais, G.R.; Despres, J.P.; Lamarche, B. Concordance/discordance between plasma apolipoprotein B levels and the cholesterol indexes of atherosclerotic risk. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003, 91, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenson, R.S.; Brewer, H.B., Jr.; Ansell, B.J.; Barter, P.; Chapman, M.J.; Heinecke, J.W.; Kontush, A.; Tall, A.R.; Webb, N.R. Dysfunctional HDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walldius, G.; Jungner, I.; Holme, I.; Aastveit, A.H.; Kolar, W.; Steiner, E. High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study): A prospective study. Lancet 2001, 358, 2026–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, M.; Messier, L.; Bastard, J.P.; Tardif, A.; Godbout, A.; Prud’homme, D.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R. Apolipoprotein B: A predictor of inflammatory status in postmenopausal overweight and obese women. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemoto, T.; Han, C.Y.; Mitra, P.; Averill, M.M.; Tang, C.; Goodspeed, L.; Omer, M.; Subramanian, S.; Wang, S.; Den Hartigh, L.J.; et al. Apolipoprotein AI and high-density lipoprotein have anti-inflammatory effects on adipocytes via cholesterol transporters: ATP-binding cassette A-1, ATP-binding cassette G-1, and scavenger receptor B-1. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale Schianca, G.P.; Pedrazzoli, R.; Onolfo, S.; Colli, E.; Cornetti, E.; Bergamasco, L.; Fra, G.P.; Bartoli, E. ApoB/apoA-I ratio is better than LDL-C in detecting cardiovascular risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, P.S.; Brodaty, H.; Valenzuela, M.J.; Lorentz, L.; Looi, J.C.; Wen, W.; Zagami, A.S. The neuropsychological profile of vascular cognitive impairment in stroke and TIA patients. Neurology 2004, 62, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.H.; Cho, S.J.; Oh, M.S.; Jung, S.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, J.H.; Koh, I.-S.; Cha, J.-K.; Park, J.-M.; Bae, H.-J.; et al. Cognitive impairment evaluated with vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards in a multicenter prospective stroke cohort in Korea. Stroke 2013, 44, 786–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.W.; Chin, J.H.; Na, D.L.; Lee, J.H.; Park, J.S. A normative study of the Korean version of Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) in the elderly. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 19, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Yum, T.H.; Park, Y.S.; Oh, K.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.H. Manual for Korean-Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; Korea Guidance: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, H.; Chin, J.H.; Lee, B.H.; Kang, Y.; Na, D.L. Development and validation of Korean version of trail making test for elderly persons. Dement. Neurocogn. Disord. 2007, 6, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, H.H.; Na, D.L. A short form of the Korean-Boston Naming Test (K-BNT) for using in dementia patients. Korean J. Clin. Psych. 1999, 18, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Na, D.L. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery; Professional manual; Human Brain Research and Consulting: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Ryu, S.G.; Cho, S.J.; Hong, C.H.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, Y.M.; Kim, B.S.; Park, E.J.; Park, S.H. Validity of the Korean version of Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly(IQCODE). J. Korean Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 9, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y. A normative study of the Korean-Mini Mental State Examination(K-MMSE) in the elderly. Korean J. Psych. 2006, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.J.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, B.H.; Kwon, J.C.; Na, D.L.; Han, S.H.; Korean Dementia Research Group. The reliability and validity of the Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL). J. Korean Neurol. Assoc. 2002, 20, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).