An Examination of the Practice Approaches of Canadian Dietitians Who Counsel Higher-Weight Adults Using a Novel Framework: Emerging Data on Non-Weight-Focused Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Development and Validation of the Practice Approach Classifications

2.3. Development, Validation, and Pilot Testing of the Full Survey

2.4. Participants and Recruitment

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Practice Approaches Used and Views

3.2. Practice Techniques Used When Working with Higher-Weight Clients

3.3. Summary of the Practice Approach Categories Used by Participants

3.3.1. Weight-Focused Approaches

3.3.2. Characteristics of Combined Approaches

3.3.3. Characteristics of Non-Weight-Focused Approaches

3.4. Education and Training for Non-Weight-Focused Approaches

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wharton, S.; Lau, D.C.W.; Vallis, M.; Sharma, A.M.; Biertho, L.; Campbell-Scherer, D.; Adamo, K.; Alberga, A.; Bell, R.; Boulé, N.; et al. Obesity in adults: A clinical practice guideline. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E875–E891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Clarke, C.; Johnson Stoklossa, C.; Sievenpiper, J. Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines: Medical Nutrition Therapy in Obesity Management. Available online: https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/nutrition (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Willer, F.; Hannan-Jones, M.; Strodl, E. Australian dietitians’ beliefs and attitudes towards weight loss counselling and health at every size counselling for larger-bodied clients. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietitians of Canada. Dietitians of Canada. Weight Stigma Background. In Practiced-Based Evidence in Nutrition (PEN); Dietitians of Canada: Toronto, ON, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.S.; Tarrant, M.; Weston, D.; Shah, P.; Farrow, C. Can Raising Awareness about the Psychological Causes of Obesity Reduce Obesity Stigma? Health Commun. 2018, 33, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thearle, M.S.; Pannacciulli, N.; Bonfiglio, S.; Pacak, K.; Krakoff, J. Extent and Determinants of Thermogenic Responses to 24 Hours of Fasting, Energy Balance, and Five Different Overfeeding Diets in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2791–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramos Salas, X.; Forhan, M.; Caulfield, T.; Sharma, A.M.; Raine, K.D. Addressing Internalized Weight Bias and Changing Damaged Social Identities for People Living With Obesity. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hunger, J.M.; Smith, J.P.; Tomiyama, A.J. An Evidence-Based Rationale for Adopting Weight-Inclusive Health Policy. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2020, 14, 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ge, L.; Sadeghirad, B.; Ball, G.D.C.; da Costa, B.R.; Hitchcock, C.L.; Svendrovski, A.; Kiflen, R.; Quadri, K.; Kwon, H.Y.; Karamouzian, M.; et al. Comparison of dietary macronutrient patterns of 14 popular named dietary programmes for weight and cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: Systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials. Bmj 2020, 369, m696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eguchi, E.; Iso, H.; Tanabe, N.; Yatsuya, H.; Tamakoshi, A. Is the association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and cardiovascular mortality modified by overweight status? The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Prev. Med. 2014, 62, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, K.; Thomas, R.J.; Squires, R.W.; Coutinho, T.; Trejo-Gutierrez, J.F.; Somers, V.K.; Miles, J.M.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Combined effect of cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity on mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. Am. Heart J. 2011, 161, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.D.; Blair, S.N.; Jackson, A.S. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, E.M.; King, D.E.; Everett, C.J. Healthy Lifestyle Habits and Mortality in Overweight and Obese Individuals. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2012, 25, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylka, T.L.; Annunziato, R.A.; Burgard, D.; Danielsdottir, S.; Shuman, E.; Davis, C.; Calogero, R.M. The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: Evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutter, S.; Russell-Mayhew, S.; Alberga, A.S.; Arthur, N.; Kassan, A.; Lund, D.E.; Sesma-Vazquez, M.; Williams, E. Positioning of Weight Bias: Moving towards Social Justice. J. Obes. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, J.; Clarke, C.; Stoklossaiii, C.J. Medical Nutrition Therapy in Obesity Management. 2020. Available online: https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/nutrition (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Barr, S.I.; Yarker, K.V.; Levy-Milne, R.; Chapman, G.E. Canadian dietitians’ views and practices regarding obesity and weight management. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2004, 17, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald-Wicks, L.K.; Gallagher, L.M.; Snodgrass, S.J.; Guest, M.; Kable, A.; James, C.; Ashby, S.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Collins, C.E. Difference in perceived knowledge, confidence and attitudes between dietitians and other health professionals in the provision of weight management advice. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 72, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaefer, J.T.; Zullo, M.D. US Registered Dietitian Nutritionists’ Knowledge and Attitudes of Intuitive Eating and Use of Various Weight Management Practices. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietitians of Canada. Dietitians of Canada Endorses International Consensus Statement against Weight Stigma. Available online: https://www.dietitians.ca/News/2020/Dietitians-of-Canada-endorses-International-consen (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simon, M.K.; White, J. Survey/Interview Validation Rubric for Expert Panel–VREP. Dissertation Recipes. Available online: http://www.dissertationrecipes.com/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Dillman, D. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd ed.; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; p. 499. [Google Scholar]

- Craving Change. Available online: https://www.cravingchange.ca/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Canadian Diabetes Educator Certification Board. Certified Diabetes Educator. Available online: https://www.cdecb.ca/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Obesity Canada. Learning Retreat on the Principles and Practice of Interdisciplinary Obesity Management. Available online: https://obesitycanada.ca/learning-retreat/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Balanced View. Balanced View: Addressing Weight Bias and Stigma in Health Care. Available online: https://balancedviewbc.ca/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- World Obesity. SCOPE. Available online: https://www.worldobesity.org/training-and-events/scope (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Marci RD Nutrition. Online Training For Dietitians And Clinicians. Available online: https://marcird.com/online-training-for-dietitians-and-clinicians/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Rubino, F.; Puhl, R.M.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Ryan, D.H.; Mechanick, J.I.; Nadglowski, J.; Ramos Salas, X.; Schauer, P.R.; Twenefour, D.; et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papadopoulos, S.; Brennan, L. Correlates of weight stigma in adults with overweight and obesity: A systematic literature review. Obesity 2015, 23, 1743–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearl, R.L.; Wadden, T.A.; Hopkins, C.M.; Shaw, J.A.; Hayes, M.R.; Bakizada, Z.M.; Alfaris, N.; Chao, A.M.; Pinkasavage, E.; Berkowitz, R.I.; et al. Association between weight bias internalization and metabolic syndrome among treatment-seeking individuals with obesity. Obesity 2017, 25, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, C.; Luppa, M.; Luck, T.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Weight stigma “gets under the skin”—Evidence for an adapted psychological mediation framework—A systematic review. Obesity 2015, 23, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, K.M.; Thurston, I.B.; Kamody, R.C. The mediating role of internalized weight stigma on weight perception and depression among emerging adults: Exploring moderation by weight and race. Body Image 2018, 27, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, H.P.; Prevost, T.A.; Wright, A.J.; Gulliford, M.C. Effectiveness of behavioural weight loss interventions delivered in a primary care setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam. Pract. 2014, 31, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brady, J. Social Justice and Dietetic Education: Are We Preparing Practitioners to Lead? Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2020, 81, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.R.D.P.; L’Heureux, T.R.D.P. Enhancing Response Ability: Dietetics as a Vehicle for Social Justice—A Primer. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2021, 82, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbridge, R.; Jovanovski, N.; Skues, J.; Belski, R. Exploring the relevance of intersectionality in Australian dietetics: Issues of diversity and representation. Sociol. Health Illn. 2022, 44, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietitians of Canada. The Dietitian Workforce in Canada: Meta-Analysis Report; Dietitians of Canada: Toronto, ON, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eat Right Pro. Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics: Dietetics Education Program Statistics 1998–2016. Available online: https://www.eatrightpro.org/-/media/eatrightpro-files/acend/diversity-enrollment-trends_1995–2016.pdf?la=en&hash=B59E9B6FB8FB1F428F7F1940459ED17D5D42FA3D (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Riediger, N.D.; Kingson, O.; Mudryj, A.; Farquhar, K.L.; Spence, K.A.; Vagianos, K.; Suh, M. Diversity and Equity in Dietetics and Undergraduate Nutrition Education in Manitoba. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2019, 80, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Practice Approach | Description |

|---|---|

| (A) Solely weight-focused |

|

| (B) Moderately weight-focused |

|

| (B) Combination |

|

| (D) Weight inclusive |

|

| (E) Weight liberated |

|

| Practice Approaches | p Value a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 383) | Solely Weight Focused (n = 3) | Moderately Weight Focused (n = 51) | Combination (n = 155) | Weight Inclusive (n = 142) | Weight Liberated (n = 32) | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Woman | 363 (94.8) | 2 (0.6) | 45 (12.4) | 149 (41.0) | 139 (38.3) | 28 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| Man | 11 (2.9) | 1 (9.1) | 5 (45.5) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Race b | |||||||

| White, e.g., European | 315 (82.2) | 1 (0.3) | 38 (12.1) | 126 (40.0) | 124 (39.4) | 26 (8.3) | 0.061 |

| East Asian, e.g., Chinese, Korean | 29 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.3) | 13 (44.8) | 10 (34.5) | 3 (10.3) | |

| Other, e.g., Middle Eastern, Latin American, Indigenous | 27 (7.0) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (22.2) | 11 (40.7) | 6 (22.2) | 3 (11.1) | |

| South/Southeast Asian | 12 (3.1) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (33.3) | 5 (41.7) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Province and Territories c | |||||||

| Ontario | 154 (40.2) | 1 (0.6) | 17 (11.0) | 63 (41.0) | 60 (39.0) | 13 (8.4) | 0.037 |

| Alberta | 120 (31.3) | 1 (0.8) | 25 (20.8) | 53 (44.2) | 34 (28.3) | 7 (5.8) | |

| British Columbia | 35 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.7) | 11 (31.4) | 19 (54.3) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Saskatchewan | 17 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (47.1) | 9 (53.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Quebec | 14 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (42.9) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Manitoba | 14 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (28.6) | 2 (14.3) | |

| New Brunswick | 12 (3.1) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | 7 (58.3) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Nova Scotia | 9 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (44.4) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prince Edward Island | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Northwest Territories | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Years of Practice as a Registered Dietitian | |||||||

| 0–5 | 120 (31.3) | 2 (1.7) | 15 (12.5) | 43 (35.8) | 48 (40.0) | 12 (10.0) | 0.973 |

| 6–10 | 86 (22.5) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (12.8) | 37 (43.0) | 32 (37.2) | 6 (7.0) | |

| 11–15 | 76 (19.8) | 1 (1.3) | 9 (11.8) | 32 (42.1) | 26 (34.2) | 8 (10.5) | |

| 16–20 | 48 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.5) | 21 (44.0) | 19 (39.6) | 2 (4.2) | |

| >20 | 53 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (18.9) | 22 (41.5) | 17 (32.1) | 4 (7.5) | |

| Highest Level of Education | |||||||

| Bachelor’s | 274 (71.5) | 2 (0.7) | 41 (15.0) | 105 (38.3) | 100 (36.5) | 26 (9.5) | 0.315 |

| Master’s | 96 (25.0) | 1 (1.0) | 9 (9.4) | 43 (44.8) | 39 (40.6) | 4 (4.2) | |

| Other | 13 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 7 (53.8) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Primary Area of Practice | |||||||

| Primary care | 195 (50.9) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (8.7) | 76 (39.0) | 81 (41.5) | 21 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient | 126 (32.9) | 3 (2.4) | 26 (20.6) | 55 (43.7) | 40 (31.7) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Other | 62 (16.2) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (12.9) | 24 (38.7) | 21 (33.9) | 9 (14.5) | |

| Type of Community | |||||||

| Urban | 208 (54.3) | 2 (1.0) | 35 (16.8) | 73 (35.1) | 78 (37.5) | 20 (9.6) | 0.192 |

| Suburban | 90 (23.5) | 1 (1.1) | 7 (7.8) | 49 (54.4) | 30 (33.3) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Rural | 65 (17.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (10.8) | 26 (40.0) | 26 (40.0) | 6 (9.2) | |

| Remote | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Do not work in a single community | 16 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (31.3) | 6 (37.5) | 3 (18.8) | |

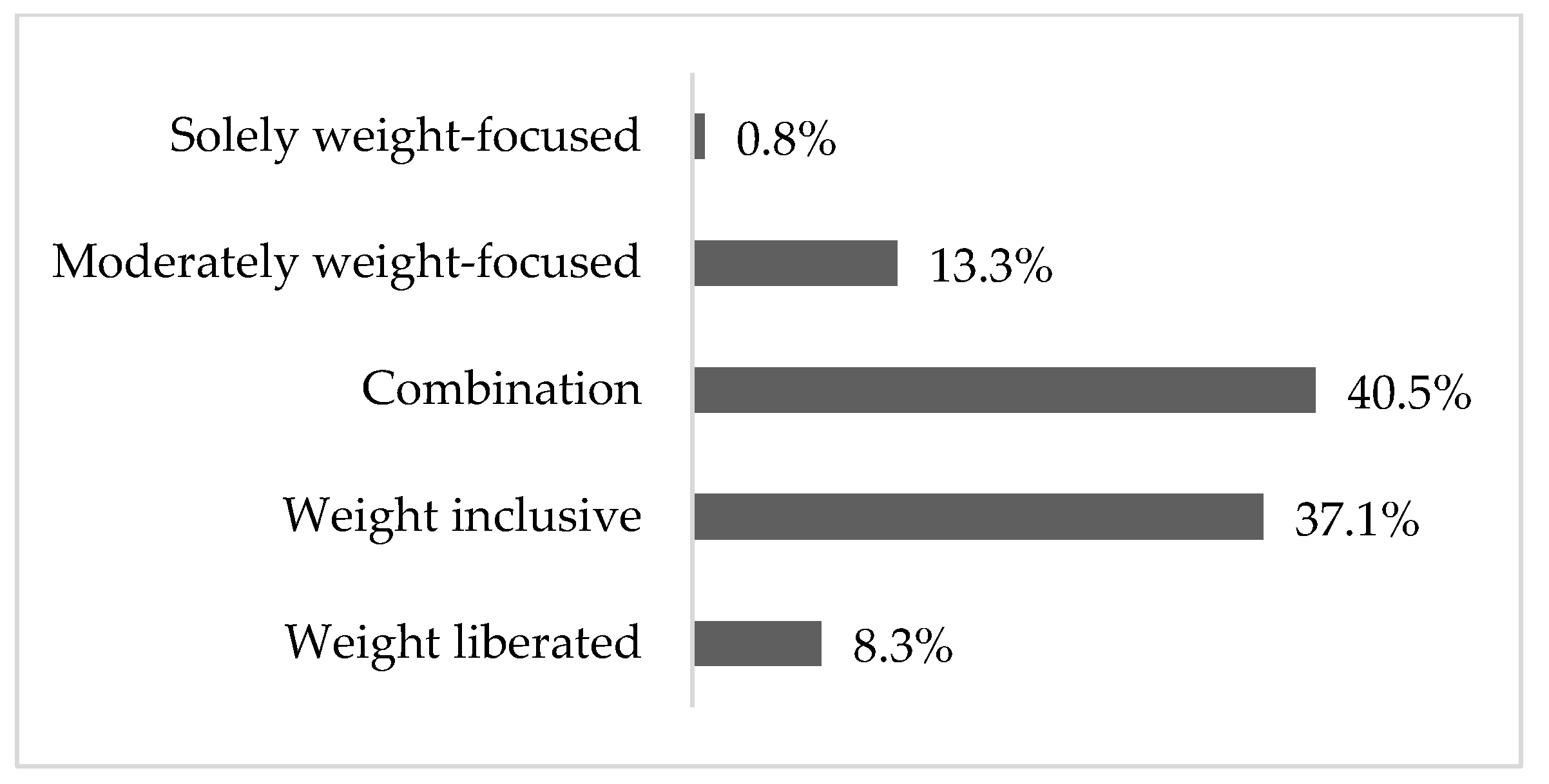

| Approach | n (%) | Descriptive Labels Participants Used to Characterize Their Practice Approach a |

|---|---|---|

| Solely weight focused | 3 (0.8%) | Patient led |

| Moderately weight focused | 51 (13.3%) | Patient/client centred, lifestyle and behaviour focused, individualized dietary behaviours, flexible, health centred, goal focused, inclusive, supportive and directive, weight management |

| Combination | 155 (40.5%) | Non-diet, patient/client centred, health focused, behaviour focused, weight neutral, HAES informed, weight inclusive informed, intuitive eating informed, modifying weight, non-weight focused, best weight, obesity management |

| Weight inclusive | 142 (37.1%) | Healthism, weight inclusive, normalized eating, anti-diet, HAES, client/patient focused, inclusive, intuitive eating, non-judgmental, non-diet, strength based, self-compassion, eating skills, body liberation, humanist, body diversity, mindful eating |

| Weight liberated | 32 (8.3%) | Weight inclusive, non-diet, fat positive, HAES, social justice oriented, anti-oppressive, trauma informed, patient/client focused, values based, well-being focused, body diversity, lived experience, anti-diet |

| Practice Approaches | p Value a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 383) | Solely Weight Focused (n = 3) | Moderately Weight Focused (n = 51) | Combination (n = 155) | Weight Inclusive (n = 142) | Weight Liberated (n = 32) | ||

| A complex and progressive chronic disease | 194 (50.7) | 2 (66.7) | 32 (62.7) | 106 (68.4) | 52 (36.6) | 2 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| Characterized by abnormal, excessive body fat (adiposity) that impairs health | 186 (48.6) | 2 (66.7) | 36 (70.6) | 89 (57.4) | 55 (38.7) | 4 (12.5) | |

| Body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2 | 104 (27.2) | 2 (66.7) | 24 (47.0) | 45 (29.0) | 30 (21.1) | 3 (9.4) | |

| I do not recognize or use this language | 102 (26.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (5.2) | 66 (46.5) | 28 (87.5) | |

| Practice Approaches b | p Value a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 383) | Solely Weight Focused (n = 3) | Moderately Weight Focused (n = 51) | Combination (n = 155) | Weight Inclusive (n = 142) | Weight Liberated (n = 32) | ||

| Assessment | |||||||

| Monitor health behaviours (e.g., diet and exercise) as an indicator of changed health risk | 367 (95.8) | 3 (100.0) | 49 (96.1) | 150 (96.8) | 138 (97.0) | 27 (84.4) | 0.048 |

| Assess metabolic parameters (lipid profile, blood glucose, liver enzymes, vitamin and mineral status, etc.) | 366 (95.6) | 3 (100.0) | 48 (94.1) | 150 (96.8) | 137 (96.5) | 28 (87.5) | 0.194 |

| Assess mental health status (e.g., depression, addition, and eating disorders) | 360 (94.0) | 3 (100.0) | 47 (92.2) | 145 (93.5) | 134 (94.4) | 31 (96.9) | 0.860 |

| Assess social health (e.g., social support, connection to care givers, and living conditions) | 350 (91.4) | 3 (100.0) | 41 (80.4) | 146 (94.2) | 130 (91.5) | 30 (93.8) | 0.075 |

| Assess financial health by collecting economic information, including food security | 314 (82.0) | 3 (100.0) | 41 (80.4) | 129 (83.2) | 111 (78.2) | 30 (93.8) | 0.275 |

| Assess mechanical health (e.g., back pain, osteoarthritis, and sleep apnea) | 308 (80.4) | 2 (66.7) | 39 (76.5) | 121 (78.1) | 117 (82.4) | 29 (90.6) | 0.341 |

| Weighs clients | 150 (39.2) | 3 (100.0) | 43 (84.3) | 71 (45.8) | 28 (19.7) | 5 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Calculate body mass index (BMI) to assess health risk | 142 (37.1) | 2 (66.7) | 41 (80.4) | 71 (45.8) | 26 (18.3) | 2 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Measure body composition | 32 (8.4) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (15.7) | 17 (11.0) | 7 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.042 |

| Other | 52 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.8) | 17 (11.0) | 21 (14.8) | 9 (28.1) | 0.130 |

| Nutrition Therapy Approaches | |||||||

| Increasing fruits and vegetables | 364 (95.0) | 3 (100.0) | 46 (90.2) | 151 (97.4) | 138 (97.2) | 26 (81.3) | 0.014 |

| Increasing intake of whole grains | 338 (88.3) | 3 (100.0) | 40 (78.4) | 141 (91.0) | 130 (91.5) | 24 (75.0) | <0.001 |

| Increasing dietary variety | 333 (86.9) | 3 (100.0) | 39 (76.5) | 135 (87.1) | 127 (89.4) | 29 (90.6) | 0.215 |

| Increasing intake of pulses | 328 (85.6) | 2 (66.7) | 35 (68.6) | 141 (91.0) | 125 (88.0) | 25 (78.1) | <0.001 |

| Doing more physical activity | 317 (82.8) | 3 (100.0) | 46 (90.2) | 133 (85.8) | 113 (79.6) | 22 (68.8) | 0.130 |

| Alternative foods for snacking | 269 (70.2) | 3 (100.0) | 42 (11.0) | 123 (32.1) | 89 (23.2) | 12 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Replacing saturated/trans fats with unsaturated fats | 246 (64.2) | 3 (100.0) | 25 (49.0) | 113 (72.9) | 89 (62.7) | 16 (50.0) | 0.004 |

| Mediterranean dietary pattern | 211 (55.1) | 1 (33.3) | 27 (52.9) | 89 (57.4) | 85 (59.9) | 9 (28.1) | 0.963 |

| Canada’s Food Guide | 206 (53.8) | 1 (33.3) | 23 (45.1) | 89 (57.4) | 81 (57.0) | 12 (37.5) | 0.018 |

| Low-glycemic index dietary pattern | 160 (41.8) | 2 (66.7) | 17 (33.3) | 79 (51.0) | 55 (38.7) | 7 (21.9) | 0.405 |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension dietary pattern (DASH) | 128 (33.4) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (33.3) | 58 (37.4) | 46 (32.4) | 7 (21.9) | 0.476 |

| Modifying specific macronutrients, e.g., low carbohydrate and high protein | 112 (29.2) | 2 (66.7) | 26 (51.0) | 49 (31.6) | 32 (22.5) | 3 (9.4) | 0.077 |

| Intake of certain foods to reduce calories | 95 (24.8) | 3 (100.0) | 32 (62.7) | 45 (29.0) | 14 (9.9) | 1 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Reducing overall caloric intake | 50 (13.1) | 2 (66.7) | 25 (49.0) | 21 (13.5) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Reducing total fat intake | 49 (12.8) | 2 (66.7) | 17 (33.3) | 21 (13.5) | 8 (5.6) | 1 (3.1) | 0.003 |

| Vegetarian dietary pattern | 46 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (11.8) | 18 (11.6) | 19 (13.4) | 3 (9.4) | 0.006 |

| Time-limited feeding, i.e., intermittent fasting | 23 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (15.7) | 12 (7.7) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.157 |

| The Nordic dietary pattern | 9 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (3.1) | 0.004 |

| A ketogenic diet | 6 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.9) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Other | 69 (18.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.8) | 19 (12.3) | 31 (21.8) | 14 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| Nutrition Therapy Techniques | |||||||

| Techniques of mindful eating | 337 (88.0) | 2 (66.7) | 44 (86.3) | 136 (87.7) | 127 (89.4) | 28 (87.5) | 0.649 |

| Recognize clients’ lived experiences impact their lives in ways that are often hidden to providers | 304 (79.4) | 2 (66.7) | 32 (62.7) | 115 (74.2) | 124 (87.3) | 31 (96.9) | <0.001 |

| Discuss the structural barriers to their being/feeling healthy or well | 289 (75.5) | 2 (66.7) | 38 (74.5) | 113 (72.9) | 108 (76.1) | 28 (87.5) | 0.433 |

| Principles of intuitive eating | 271 (70.8) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (29.4) | 102 (65.8) | 124 (87.3) | 30 (93.8) | <0.001 |

| Principles of compassion-informed counselling | 250 (65.3) | 3 (100.0) | 31 (60.8) | 92 (59.4) | 96 (67.6) | 28 (88.0) | 0.015 |

| Principles of Health At Every Size® | 248 (64.8) | 1 (33.3) | 13 (25.5) | 84 (54.2) | 121 (85.2) | 29 (90.6) | <0.001 |

| Recommend keeping a hunger awareness diary | 239 (62.4) | 1 (33.3) | 25 (49.0) | 98 (63.2) | 93 (65.5) | 22 (68.8) | 0.192 |

| Recommend that clients do not weigh themselves | 206 (53.8) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (27.5) | 81 (52.3) | 84 (59.2) | 27 (84.4) | <0.001 |

| Principles of culturally safe care | 192 (50.1) | 1 (33.3) | 12 (23.5) | 83 (53.5) | 72 (50.7) | 24 (75.0) | <0.001 |

| Recommend keeping a food intake diary | 183 (47.8) | 3 (100.0) | 37 (72.5) | 93 (60.0) | 45 (31.7) | 5 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Principles of harm reduction counselling | 162 (42.3) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (29.4) | 59 (38.1) | 63 (44.4) | 25 (78.1) | <0.001 |

| Recommend eating smaller, more frequent meals | 136 (35.5) | 1 (33.3) | 25 (49.0) | 68 (43.9) | 39 (27.0) | 3 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Principles of trauma-informed counselling | 121 (31.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (17.6) | 42 (27.1) | 48 (33.8) | 22 (68.8) | <0.001 |

| Draw on equity-seeking clients’ experiences of oppression | 93 (24.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.8) | 28 (18.1) | 36 (25.4) | 24 (75.0) | <0.001 |

| Recommend limiting snacking | 81 (21.1) | 2 (66.7) | 25 (49.0) | 43 (27.7) | 10 (7.0) | 1 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Recommend weight loss | 20 (5.2) | 2 (66.7) | 12 (23.5) | 6 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Recommend keeping a weight diary | 15 (3.9) | 1 (33.3) | 11 (21.6) | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Recommend commercial weight loss products | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.219 |

| Other | 26 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.9) | 9 (5.8) | 10 (7.0) | 4 (12.5) | 0.635 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lichtfuss, K.; Franco-Arellano, B.; Brady, J.; Arcand, J. An Examination of the Practice Approaches of Canadian Dietitians Who Counsel Higher-Weight Adults Using a Novel Framework: Emerging Data on Non-Weight-Focused Approaches. Nutrients 2023, 15, 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030631

Lichtfuss K, Franco-Arellano B, Brady J, Arcand J. An Examination of the Practice Approaches of Canadian Dietitians Who Counsel Higher-Weight Adults Using a Novel Framework: Emerging Data on Non-Weight-Focused Approaches. Nutrients. 2023; 15(3):631. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030631

Chicago/Turabian StyleLichtfuss, Kori, Beatriz Franco-Arellano, Jennifer Brady, and JoAnne Arcand. 2023. "An Examination of the Practice Approaches of Canadian Dietitians Who Counsel Higher-Weight Adults Using a Novel Framework: Emerging Data on Non-Weight-Focused Approaches" Nutrients 15, no. 3: 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030631