Does Neighborhood Social Capital Longitudinally Affect the Nutritional Status of School-Aged Children? Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

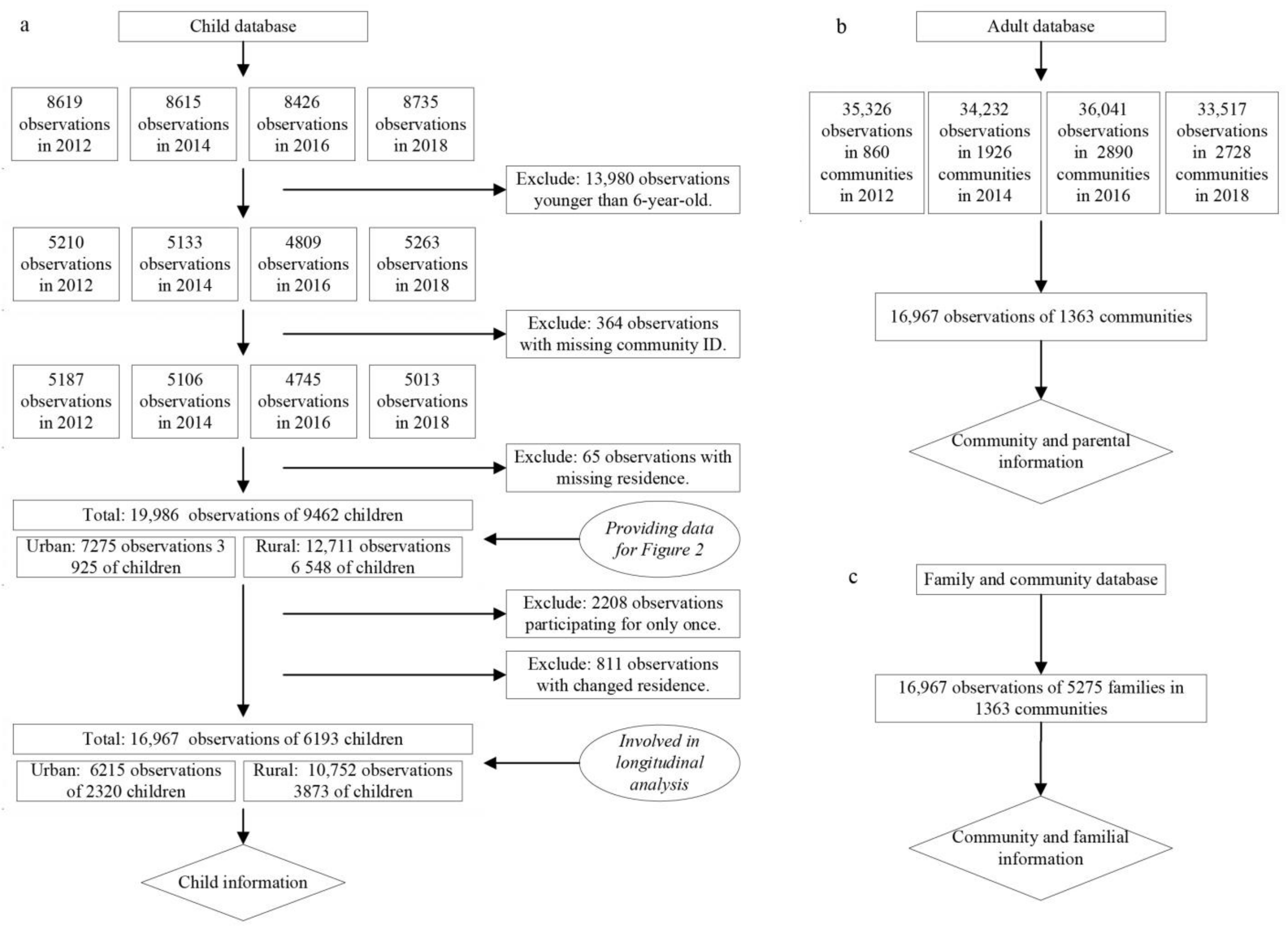

2.2. Data

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Social Capital Indicators

2.5. Controls

2.6. Analytical Strategy

2.7. Missing Data

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Child Participants across Survey Waves

3.2. Temporal Trend of the Nutritional Status of Urban and Rural Children

3.3. The Longitudinal Relationships between Social Capital Components and Child BAZ

3.4. The Longitudinal Relationships between Social Capital Components and Child BMI Categories

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- PWC. Weighing the Cost of Obesity: A Case for Action; PricewaterhouseCoopers: Barangaroo, NSW, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Pan, J. The Medical Cost Attributable to Obesity and Overweight in China: Estimation Based on Longitudinal Surveys. Health Econ. 2016, 25, 1291–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.F.; Wang, L.; Pan, A. Epidemiology and Determinants of Obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, C.M.; Bell-Ellison, B.A.; Wallace, K.; Ferron, J.M. A Multilevel Study of the Associations between Economic and Social Context, Stage of Adolescence, and Physical Activity and Body Mass Index. Pediatrics 2007, 119, S84–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reinehr, T. Lifestyle Intervention in Childhood Obesity: Changes and Challenges. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobstein, T.; Baur, L.; Uauy, R. Obesity in Children and Young People: A Crisis in Public Health. Obes. Rev. Suppl. 2004, 5, 4–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Álvarez, E.; Kawachi, I.; Riera-Romaní, J. Neighbourhood Social Capital and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carroll-Scott, A.; Gilstad-Hayden, K.; Rosenthal, L.; Peters, S.M.; McCaslin, C.; Joyce, R.; Ickovics, J.R. Disentangling Neighborhood Contextual Associations with Child Body Mass Index, Diet, and Physical Activity: The Role of Built, Socioeconomic, and Social Environments. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 95, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bala-Brusilow, C. A Study of the Associations between Childhood Obesity and Three Forms of Social Capital. Ph.D. Dissertaion, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Suglia, S.F.; Shelton, R.C.; Hsiao, A.; Wang, Y.C.; Rundle, A.; Link, B.G. Why the Neighborhood Social Environment Is Critical in Obesity Prevention. J. Urban Heal. 2016, 93, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sarni, R.O.S.; Kochi, C.; Suano-Souza, F.I. Childhood Obesity: An Ecological Perspective. J. Pediatr. (Rio. J). 2021, 98, S38–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bont, J.; Casas, M.; Barrera-Gómez, J.; Cirach, M.; Rivas, I.; Valvi, D.; Álvarez, M.; Dadvand, P.; Sunyer, J.; Vrijheid, M. Ambient Air Pollution and Overweight and Obesity in School-Aged Children in Barcelona, Spain. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacarne, D.; Handakas, E.; Robinson, O.; Pineda, E.; Saez, M.; Chatzi, L.; Fecht, D. The Built Environment as Determinant of Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mölenberg, F.J.M.; Mackenbach, J.D.; Poelman, M.P.; Santos, S.; Burdorf, A.; van Lenthe, F.J. Socioeconomic Inequalities in the Food Environment and Body Composition among School-Aged Children: A Fixed-Effects Analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 2554–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, H.; Zubrick, S.R.; Foster, S.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bull, F.; Wood, L.; Knuiman, M.; Brinkman, S.; Houghton, S.; Boruff, B. The Influence of the Neighborhood Physical Environment on Early Child Health and Development: A Review and Call for Research. Health Place 2015, 33, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Phillips, D.R.; Rosenberg, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, H. Does Social Capital Interact with Economic Hardships in Influencing Older Adults’ Health? A Study from China. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kim, D. Social Capital and Health; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780387713106. [Google Scholar]

- Rabasa, C.; Dickson, S.L. Impact of Stress on Metabolism and Energy Balance. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borgonovi, F. A Life-Cycle Approach to the Analysis of the Relationship between Social Capital and Health in Britain. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1927–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zwaard, B.C.; Schalkwijk, A.A.H.; Elders, P.J.M.; Platt, L.; Nijpels, G. Does Environment Influence Childhood BMI? A Longitudinal Analysis of Children Aged 3-11. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.H.; Moore, S.; Dube, L. Social Capital and Obesity among Adults: Longitudinal Findings from the Montreal Neighborhood Networks and Healthy Aging Panel. Prev. Med. 2018, 111, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Jan, C.; Ma, Y.; Dong, B.; Zou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, R.; Song, Y.; Ma, J.; Sawyer, S.M.; et al. Economic Development and the Nutritional Status of Chinese School-Aged Children and Adolescents from 1995 to 2014: An Analysis of Five Successive National Surveys. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, M.; Yang, Y. Blue Paper on Obesity Prevention and Control in China; Peking University Medical Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Xi, J.; Hall, B.J.; Fu, M.; Zhang, B.; Guo, J.; Feng, X.L. Attitudes toward Aging, Social Support and Depression among Older Adults: Difference by Urban and Rural Areas in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Social Science Survey. China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Available online: http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Rodgers, J.; Valuev, A.V.; Hswen, Y.; Subramanian, S.V. Social Capital and Physical Health: An Updated Review of the Literature for 2007–2018. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 236, 112360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, C.L.; Wallace, S.P.; Ponce, N.A. Helpfulness, Trust, and Safety of Neighborhoods: Social Capital, Household Income, and Self-Reported Health of Older Adults. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amegbor, P.M.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Kuuire, V.Z. Does Place Matter? A Multilevel Analysis of Victimization and Satisfaction with Personal Safety of Seniors in Canada. Health Place 2018, 53, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, S.; Lu, N. Community-Based Social Capital and Self-Reported Health among Older Chinese Adults: The Moderating Effects of Eduction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16(15), 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abewe, C. Investigating Family Social Capital and Child Health: A Case Study of South Africa; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Jiang, S.; Fang, X. Effects of Multi-Dimensional Social Capital on Mental Health of Children in Poverty: An Empirical Study in Mainland China. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, U.; Hochwälder, J.; Carlsund, Å.; Sellström, E. Health Outcomes among Swedish Children: The Role of Social Capital in the Family, School and Neighbourhood. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2012, 101, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, D.; Suzuki, E.; Kawachi, I. Are Family, Neighbourhood and School Social Capital Associated with Higher Selfrated Health among Croatian High School Students? A Population-Based Study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Gerrit, W. Estimating within Group Interrater Reliability with and without Response Bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Amini, M.M.; Babakus, E.; Stafford, M.B.R. Handling Observations with Low Interrater Agreement Values. J. Anal. Sci. Methods Instrum. 2011, 01, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lebreton, J.M.; Burgess, J.R.D.; Kaiser, R.B.; Atchley, E.K.; James, L.R. The Restriction of Variance Hypothesis and Interrater Reliability and Agreement: Are Ratings from Multiple Sources Really Dissimilar? Organ. Res. Methods 2003, 6, 80–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Dong, B.; Zou, Z.; Hu, P.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Song, Y.; Ma, J. Geographical Variation and Urban-Rural Disparity of Overweight and Obesity in Chinese School-Aged Children between 2010 and 2014: Two Successive National Cross-Sectional Surveys. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day, K.; Alfonzo, M.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Z.; Lee, K.K. Overweight, Obesity, And Inactivity and Urban Design in Rapidly Growing Chinese Cities. Heal. Place 2013, 21, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Rehnberg, C.; Meng, Q. How Are Individual-Level Social Capital and Poverty Associated with Health Equity? A Study from Two Chinese Cities. Int. J. Equity Health 2009, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Lyu, S. Social Participation and Urban-Rural Disparity in Mental Health among Older Adults in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Pei, G.; Jin, J.; De Wit, H. De What Makes You Generous? The Influence of Rural and Urban Rearing on Social Discounting in China. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0133078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norstrand, J.A.; Xu, Q. Social Capital and Health Outcomes among Older Adults in China: The Urban-Rural Dimension. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veitch, J.; van Stralen, M.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; te Velde, S.J.; Crawford, D.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A. The Neighborhood Social Environment and Body Mass Index among Youth: A Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Min, J.; Fang Yan, A.; Wang, Y. Mismatch in Children’s Weight Assessment, Ideal Body Image, and Rapidly Increased Obesity Prevalence in China: A 10-Year, Nationwide, Longitudinal Study. Obesity 2018, 26, 1777–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yip, W. China’s Latest Online Skinny Fad Sparks Concern. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-56343081 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Zhang, L.; Qian, H.; Fu, H. To Be Thin but Not Healthy—The Body-Image Dilemma May Affect Health among Female University Students in China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liang, R.; Ma, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Cheung, E.F.C.; Roalf, D.R.; Gur, R.C.; Chan, R.C.K. Body Image Attitude among Chinese College Students. PsyCh J. 2018, 7, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Yao, S. The Impact of the Nutrition Improvement Program on Children’s Health in Rural Areas: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Mao, S.; Du, H. Residential Mobility and Neighbourhood Attachment in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Plan. A 2019, 51, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, K.A.; Li, C.; Kawachi, I.; Hunt, D.C.; Ahluwalia, J.S. The Relationships of Social Participation and Community Ratings to Health and Health Behaviors in Areas with High and Low Population Density. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 2303–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, H.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.; Timperio, A.; Foster, S. The Influence of the Built Environment, Social Environment and Health Behaviors on Body Mass Index. Results from RESIDE. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Mi, B.; Taveras, E.; Bartashevskyy, M. Potentially Modifiable Mediators for Socioeconomic Disparities in Childhood Obesity in the United States. Obesity 2022, 30, 718–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, M.; Li, W. The Extent of Family and School Social Capital Promoting Positive Subjective Well-Being among Primary School Children in Shenzhen, China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Urban | Rural | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAZ | −0.1001 (−0.1003,−0.0999) | −0.1373 (−0.1375,−0.1370) | −0.0615 (−0.0618,−0.0612) | 0.000 |

| BMI classification (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018) | ||||

| Underweight | 13.4, 12.4, 11.7, 9.9 | 12.3, 12.3, 11.2, 9.7 | 13.9, 12.5, 12.2, 10.1 | a, b, c, d |

| Normal | 61.2, 62.5, 61.5, 62.0 | 62.6, 62.8, 61.3, 62.0 | 60.7, 62.2, 61.8, 62.0 | |

| Overweight/Obese | 25.3, 25.0, 26.8, 28.1 | 25.2, 24.9, 27.5, 28.3 | 25.4, 25.3, 26.1, 27.9 | |

| Age (child) | 10.53 (10.53–10.53) | 10.56 (10.56–10.56) | 10.50 (10.50–10.50) | 0.458 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 49.4 | 48.1 | 50.6 | 0.000 |

| Female | 50.6 | 51.9 | 49.4 | |

| Hours watching TV, movies and other videos/week | 11.178 (11.177–11.179) | 10.493 (10.492–10.495) | 12.311 (12.308–12.313) | 0.000 |

| Physical exercise/week | ||||

| Never | 21.7 | 22.3 | 21.2 | 0.000 |

| Once/week | 6.6 | 4.9 | 8.4 | |

| Twice or three times/week | 37.5 | 34.5 | 40.5 | |

| Four times or more/week | 34.1 | 38.3 | 29.9 | |

| Body mass index (father) | 23.57 (23.51–23.62) | 24.05 (23.98–23.33) | 23.26 (23.19–23.33) | 0.000 |

| Body mass index (mother) | 22.64 (22.59–22.70) | 22.82 (22.73–22.90) | 22.53 (22.46–22.60) | 0.000 |

| Age (father) | 38.88 (38.79–38.98) | 39.08 (38.94–39.22) | 38.77 (38.66,38.89) | 0.002 |

| Age (mother) | 36.96 (36.88–37.05) | 37.13 (37.00–37.26) | 36.86 (36.75–36.98) | 0.004 |

| Months living with parents/year (father, mother) | ||||

| Almost never | 7.4, 6.2 | 7.0, 5.1 | 7.7, 7.3 | e, f |

| 1 month | 9.1, 5.8 | 6.4, 3.8 | 11.7, 7.7 | |

| 2–4 months | 16.9, 11.7 | 12.0, 7.8 | 21.4, 15.4 | |

| 5–7 months | 6.9, 4.6 | 5.6, 3.4 | 8.1, 5.7 | |

| 8–10 months | 4.5, 3.0 | 3.7, 2.0 | 5.2, 3.9 | |

| 11 months | 1.5, 1.3 | 1.7, 1.2 | 1.3, 1.4 | |

| Almost the entire year | 53.8, 67.4 | 63.5, 76.8 | 44.7, 58.6 | |

| Parental educational attainment (father, mother) | ||||

| No formal education | 14.9, 23.1 | 9.3, 11.5 | 20.2, 34.0 | g, h |

| Primary school | 26.5, 26.3 | 19.3, 20.4 | 33.2, 31.9 | |

| Middle school | 36.3, 32.2 | 36.6, 36.7 | 35.9, 28.0 | |

| High school | 13.7, 11.3 | 19.3, 18.3 | 8.5, 4.8 | |

| College or higher | 8.6, 7.1 | 15.5, 13.2 | 2.2, 1.3 | |

| Parental marital status (father, mother) | ||||

| Single | 0.4, 0.3 | 0.3, 0.2 | 0.5, 0.4 | i, j |

| Married/cohabit | 96.7, 97.5 | 96.9, 96.7 | 96.6, 97.9 | |

| Divorced | 2.4, 1.1 | 2.4, 2.1 | 2.3, 0.6 | |

| Widowed | 0.5, 1.1 | 0.4, 1.0 | 0.5, 1.1 | |

| Quartile—Average Family income | ||||

| 1st | 28.3 | 19.8 | 36.1 | 0.000 |

| 2nd | 30.7 | 28.4 | 32.9 | |

| 3rd | 25.1 | 28.9 | 21.6 | |

| 4th | 15.9 | 22.9 | 9.3 | |

| Family size | 5.20 (5.18,5.23) | 4.78 (4.74,4.82) | 5.45 (5.42,5.48) | 0.000 |

| Neighborhood economic level (lowest 1–highest 7) | 4.48 (4.40–4.56) | 4.93 (4.83–5.03) | 4.04 (3.93–4.15) | 0.000 |

| Family social capital (standardized) | 3.341 (3.329,3.351) | 3.452 (3.434,3.469) | 3.272 (3.258,3.286) | 0.000 |

| Neighborhood social participation (standardized) | 0.202 (0.200,0205) | 0.278 (0.272,0.283) | 0.159 (0.157,0.161) | 0.000 |

| Neighborhood bonding trust (standardized) | 0.003 (−0.010,0.015) | −0.073 (−0.095,−0.051) | 0.045 (0.029,0.060) | 0.000 |

| Neighborhood bridging trust (standardized) | 0.139 (0.132,0.146) | 0.021 (0.009,0.033) | 0.205 (0.197,0.213) | 0.000 |

| 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | |

| Participants | 3813 | 886 | 2927 | 4810 | 1903 | 2907 | 4520 | 1816 | 2704 | 3824 | 1610 | 2214 |

| BMI classification | ||||||||||||

| Underweight | 13.8 | 12.0 | 14.1 a | 12.8 | 11.5 | 13.1 b | 12.7 | 11.6 | 13.5 c | 10.1 | 9.8 | 10.3 d |

| Normal | 61.3 | 62.9 | 60.5 | 61.3 | 63.3 | 60.4 | 60.5 | 62.3 | 59.2 | 61.9 | 63.1 | 61.1 |

| O/O | 24.9 | 25.1 | 25.4 | 25.9 | 25.2 | 26.5 | 26.8 | 26.0 | 27.3 | 27.9 | 27.1 | 28.6 |

| Change in: BMI-for-age z-score | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 55.9 | 53.5 | 57.7 e | 55.5 | 55.6 | 55.3 f | 53.3 | 51.3 | 55 g | |||

| Unchanged | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |||

| Higher | 43.9 | 46.4 | 42 | 44.3 | 44.1 | 44.4 | 46.4 | 48.4 | 44.9 | |||

| Family social capital | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 46 | 48.6 | 44.1 h | 55.3 | 56.9 | 54.2 i | 53.8 | 53.5 | 54.1 j | |||

| Unchanged | 9.9 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 8 | 6.7 | |||

| Higher | 44.1 | 41.5 | 45.9 | 38.3 | 36.5 | 39.5 | 38.9 | 38.5 | 39.2 | |||

| Neighborhood social participation | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 56.4 | 59.2 | 54.6 k | 55.3 | 58.2 | 53.2 l | 55.9 | 59.6 | 53.4 m | |||

| Unchanged | 1.5 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 1.2 | |||

| Higher | 42 | 38.2 | 44.6 | 43.5 | 38.9 | 45.6 | 41.7 | 36.2 | 45.5 | |||

| Neighborhood bonding trust | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 61.2 | 64.3 | 59.2 n | 72.7 | 68.6 | 75.4 o | 55.7 | 60.2 | 52.7 p | |||

| Unchanged | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | |||

| Higher | 38.7 | 35.7 | 40.7 | 27.2 | 31.4 | 24.5 | 44.3 | 39.8 | 47.2 | |||

| Neighborhood bridging trust | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 76.9 | 87.5 | 70.1 q | 86.9 | 89.8 | 85.1 r | 71.7 | 78.2 | 67.2 s | |||

| Unchanged | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Higher | 23.0 | 12.4 | 29.8 | 13.1 | 10.2 | 14.9 | 28.3 | 21.8 | 37.8 | |||

| BMI of father | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 35.5 | 35.0 | 35.9 t | 30.9 | 28.1 | 33.0 u | 38.3 | 37.0 | 39.3 v | |||

| Unchanged | 13.4 | 13.6 | 13.2 | 26.1 | 29.2 | 23.8 | 13.9 | 16.4 | 12.0 | |||

| Higher | 51.1 | 51.4 | 50.9 | 43.0 | 42.7 | 43.2 | 47.7 | 46.5 | 48.7 | |||

| BMI of mother | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 34.9 | 32.5 | 36.8 w | 30.2 | 29.7 | 30.5 x | 36.0 | 34.9 | 36.9 y | |||

| Unchanged | 11.6 | 14.3 | 9.4 | 23.7 | 25.6 | 22.3 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 12.0 | |||

| Higher | 53.5 | 53.2 | 53.8 | 46.1 | 44.7 | 47.3 | 51.5 | 52.0 | 51.0 | |||

| Average family income | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 26.2 | 27.7 | 25.2 z | 32.6 | 29.3 | 34.8 a’ | 23.4 | 22.8 | 23.9 b’ | |||

| Unchanged | 42.6 | 43.7 | 41.9 | 46.6 | 47.7 | 45.9 | 50.7 | 50.3 | 50.9 | |||

| Higher | 31.2 | 28.6 | 32.9 | 20.8 | 23.0 | 19.3 | 25.9 | 26.9 | 25.2 | |||

| Components | Indicators | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood social trust | How much do you trust your parents? | Ranged from 0 to 10 with 0 meaning distrustful and 10 indicating very trustworthy. |

| How much do you trust your neighbors? | ||

| How much do you trust people you meet for the first time? | ||

| How much do you trust cadres (the local government official)? | ||

| How much do you trust doctors? | ||

| Neighborhood social participation | How many political/cultural/civic/developmental/religious/any other social groups or organizations are you in? | From 0 to N |

| Family social capital | How often do you discuss what happens at school with your child? | 1. Never 2. Rarely (once a month) 3. Sometimes (once a week) 4. Often (2–4 times a week) 5. Very often (5–7 times a week) |

| How often do you ask the child to finish homework? | ||

| How often do you check the child’s homework? | ||

| How often do you restrict or stop the child from watching TV? | ||

| How often do you know with whom the child is when he/she is not at home? | ||

| How often do you give up watching TV shows you like to avoid disturbing your child when he/she is studying? |

| Fac 1 (BOT) | Fac 2 (BRT) | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of trust in parents | 0.951 | −0.068 | 0.861 |

| Degree of trust in neighbors | 0.918 | 0.138 | 0.909 |

| Degree of trust in doctors | 0.883 | 0.171 | 0.809 |

| Degree of trust in cadres | −0.034 | 0.833 | 0.695 |

| Degree of trust in strangers | 0.166 | 0.719 | 0.545 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, L.; Yang, L.; Li, H. Does Neighborhood Social Capital Longitudinally Affect the Nutritional Status of School-Aged Children? Evidence from China. Nutrients 2023, 15, 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030633

Gu L, Yang L, Li H. Does Neighborhood Social Capital Longitudinally Affect the Nutritional Status of School-Aged Children? Evidence from China. Nutrients. 2023; 15(3):633. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030633

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Lijuan, Linsheng Yang, and Hairong Li. 2023. "Does Neighborhood Social Capital Longitudinally Affect the Nutritional Status of School-Aged Children? Evidence from China" Nutrients 15, no. 3: 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030633