Effect of Binge-Drinking on Quality of Life in the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

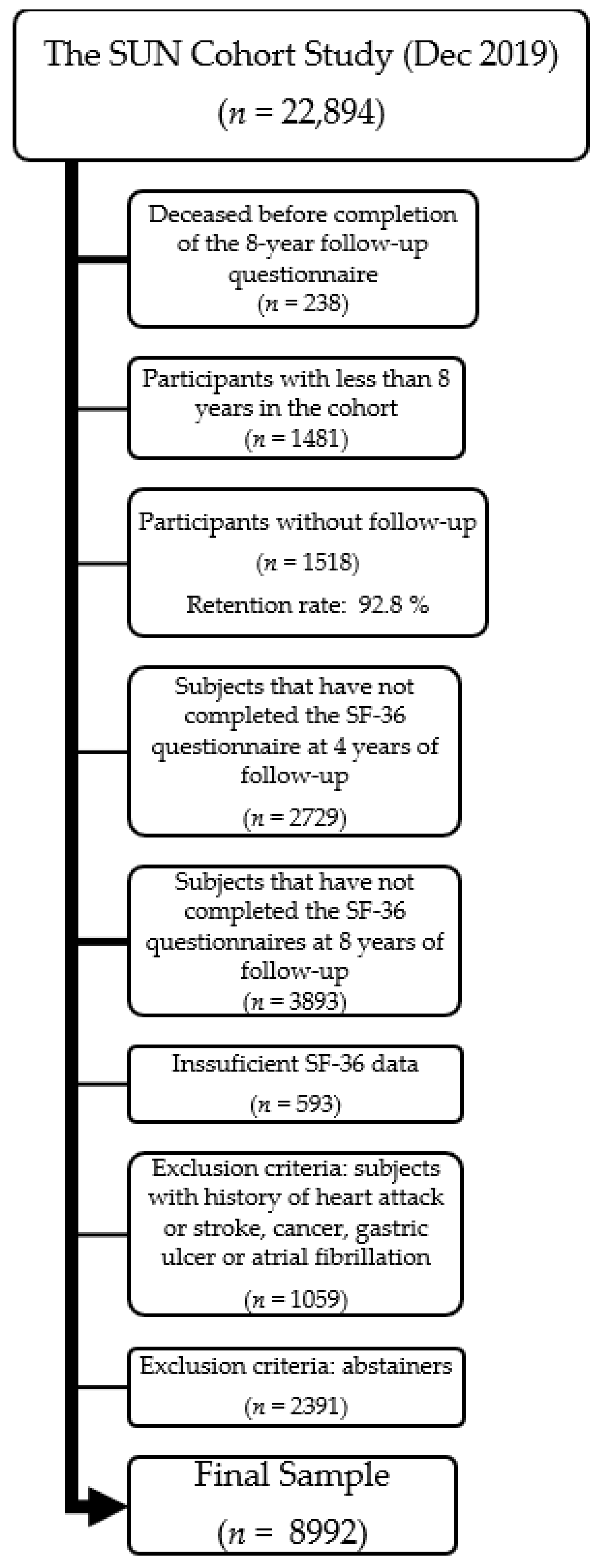

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Outcome Measurement

2.3. Binge-Drinking Assessment

2.4. Other Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO; Hammer, J.H.; Parent, M.C.; Spiker, D.A. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 65, Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112736 (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Rehm, J.; Baliunas, D.; Borges, G.L.G.; Graham, K.; Irving, H.; Kehoe, T.; Parry, C.D.; Patra, J.; Popova, S.; Poznyak, V.; et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: An overview. Addiction 2010, 105, 817–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, P.E.; Nelson, S. Binge Drinking’s Effects on the Body. Alcohol Res. 2018, 39, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.A.; Lueras, J.M.; Nagel, B.J. Effects of Binge Drinking on the Developing Brain. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2018, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, J.J.; Gonzales, K.R.; Bouchery, E.E.; Tomedi, L.E.; Brewer, R.D. 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, e73–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deparment of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Drinking Levels Defined|National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Kuntsche, E.; Knibbe, R.; Gmel, G.; Engels, R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 25, 841–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lac, A.; Donaldson, C.D. Alcohol attitudes, motives, norms, and personality traits longitudinally classify nondrinkers, moderate drinkers, and binge drinkers using discriminant function analysis. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones (OEDA); Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas (DGPNSD). Encuesta Sobre Alcohol y Otras Drogas En España, EDADES 2019/20; Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://pnsd.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/sistemasInformacion/sistemaInformacion/pdf/EDADES_2019-2020_resumenweb.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Bergamini, E.; Demidenko, E.; Sargent, J.D. Trends in Tobacco and Alcohol Brand Placements in Popular US Movies, 1996 Through 2009. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koordeman, R.; Kuntsche, E.; Anschutz, D.J.; Van Baaren, R.B.; Engels, R. Do We Act upon What We See? Direct Effects of Alcohol Cues in Movies on Young Adults’ Alcohol Drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011, 46, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilagut, G.; Valderas, J.M.; Ferrer, M.; Garin, O.; López-García, E.; Alonso, J. Interpretation of SF-36 and SF-12 questionnaires in Spain: Physical and mental components. Med. Clin. 2008, 130, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, C.A.; Brewer, R.D.; Naimi, T.S.; Moriarty, D.G.; Giles, W.H.; Mokdad, A.H. Binge drinking and health-related quality of life: Do popular perceptions match reality? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Wang, P.; Abdin, E.; Chang, S.; Shafie, S.; Sambasivam, R.; Tan, K.B.; Tan, C.; Heng, D.; Vaingankar, J.; et al. Prevalence of binge drinking and its association with mental health conditions and quality of life in Singapore. Addict. Behav. 2019, 100, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormal, V.; Bremhorst, V.; Lannoy, S.; Lorant, V.; Luquiens, A.; Maurage, P. Binge drinking is associated with reduced quality of life in young students: A pan-European study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 193, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salonsalmi, A.; Rahkonen, O.; Lahelma, E.; Laaksonen, M. The association between alcohol drinking and self-reported mental and physical functioning: A prospective cohort study among City of Helsinki employees. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.-J.; Kanny, D.; Thompson, W.; Okoro, C.; Town, M.; Balluz, L. Binge Drinking Intensity and Health-Related Quality of Life Among US Adult Binge Drinkers. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9, E86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, R.J.; Cantor, S.B.; Steinbauer, J.R.; Cass, A.R. Alcohol Use Disorders, Consumption Patterns, and Health-Related Quality of Life of Primary Care Patients. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1997, 21, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, L.A.; Grubaugh, A.L.; Frueh, B.C.; Ellis, C.; Egede, L.E. Associations between binge and heavy drinking and health behaviors in a nationally representative sample. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 1240–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, E.; Kuntsche, S.; Thrul, J.; Gmel, G. Binge drinking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 976–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Orford, J.; Britton, A. Heavy Drinking Days and Mental Health: An Exploration of the Dynamic 10-Year Longitudinal Relationship in a Prospective Cohort of Untreated Heavy Drinkers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 39, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.; Duffy, L.; Burns, L.; Loxton, D. Binge drinking and subsequent depressive symptoms in young women in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 161, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paljärvi, T.; Koskenvuo, M.; Poikolainen, K.; Kauhanen, J.; Sillanmäki, L.; Mäkelä, P. Binge drinking and depressive symptoms: A 5-year population-based cohort study. Addiction 2009, 104, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.A.; Villarosa-Hurlocker, M.C. Drinking patterns of college students with comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms: The moderating role of gender. J. Subst. Use 2021, 26, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Vila, H.; Ortolá, R.; García-Esquinas, E.; León-Muñoz, L.M.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Changes in Alcohol Consumption and Associated Variables among Older Adults in Spain: A population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, S.; Bilal, U.; Galán, I.; Villalbí, J.R.; Espelt, A.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Franco, M.; Lazo, M. Binge drinking and well-being in European older adults: Do gender and region matter? Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritsotakis, G.; Psarrou, M.; Vassilaki, M.; Androulaki, Z.; Philalithis, A.E. Gender differences in the prevalence and clustering of multiple health risk behaviours in young adults. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2098–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A. The SUN cohort study (Seguimiento University of Navarra). Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, S.; De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Razquin, C.; Rico-Campà, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. Mediterranean Diet and Health Outcomes in the SUN Cohort. Nutrients 2018, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Córdoba, J.; Garin, O.; Olivé, G.; Flavià, M.; Vargas, V.; Esteban, R.; Alonso, J. Validity of the Spanish version of the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) as a standard outcome for quality of life assessment. Liver Transplant. 2005, 12, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilagut, G.; Ferrer, M.; Rajmil, L.; Rebollo, P.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Quintana, J.M.; Santed, R.; Valderas, J.M.; Ribera, A.; Domingo-Salvany, A.; et al. The Spanish Version of the Short Form 36 Health Survey: A Decade of Experience and New Developments. Gac. Sanit. 2005, 19, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Pérez Valdivieso, J.R.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Alonso, Á.; Martínez-González, M.Á. Validation of Self-Reported Weight and Body Mass Index of the Participants of a Cohort of University Graduates. Rev. Esp. De Obes. 2005, 3, 352–358. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; López-Fontana, C.; Varo, J.J.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Martinez, J.A. Validation of the Spanish version of the physical activity questionnaire used in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ballart, J.D.; Piñol, J.L.; Zazpe, I.; Corella, D.; Carrasco, P.; Toledo, E.; Perez-Bauer, M.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Martín-Moreno, J.M. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1808–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Moreno, J.M.; Boyle, P.; Gorgojo, L.; Maisonneuve, P.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, J.C.; Salvini, S.; Willett, W.C. Development and Validation of a Food Frequency Questionnaire in Spain. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1993, 22, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Ruiz, Z.V.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Sampson, L.; Martinez-González, M.A. Reproducibility of an FFQ validated in Spain. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Understanding Binge Drinking. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/binge-drinking (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Cortés-Tomás, M.-T.; Giménez-Costa, J.-A.; Martín-Del-Río, B.; Gómez-Íñiguez, C.; Solanes-Puchol, Á. Binge Drinking: The Top 100 Cited Papers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Basal Characteristics | No Binge-Drinking (n= 5917) | Binge-Drinking (n = 3075) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Years of university education, median (IQR) | 5 (4–5) | 5 (4–5) |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Single | 43.1 | 42.9 |

| Married | 52.6 | 52.5 |

| Other | 4.3 | 4.6 |

| Job occupation (%) | ||

| Full time | 84.2 | 84.9 |

| Part time | 8.5 | 7.2 |

| Housekeeper | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Unemployed | 3.8 | 4.1 |

| Retired | 1.6 | 2.1 |

| Health professionals (%) | 54.1 | 53.6 |

| Lifestyle habits | ||

| Physical activity (METS-h/week), median (IQR) | 16.5 (6.4–30.7) | 16.8 (5.7–30.8) |

| Sleeping hours (h/day), mean (SD) | 7.1 (0.9) | 7.2 (0.9) |

| Alcohol intake (g/day), median (IQR) | 3.5 (1.6–8.8) | 8.1 (3.5–15.0) |

| Smoking status (%) | ||

| Current smoker | 19.3 | 28.3 |

| Former smoker Lifetime tobacco exposure (pack-years), mean (SD) | 28.0 4.9 (8.9) | 36.7 7.8 (11.1) |

| Anthropometric and clinical data | ||

| Total energy intake (kcal/d), median (IQR) | 2434 (1993–2966) | 2424 (1946–2986) |

| Adherence to the MDS * (0 to 8 score), mean (SD) | 4.0 (1.7) | 3.9 (1.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 23.3 (3.3) | 23.9 (3.6) |

| Type 2-diabetes mellitus (%) | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Hypertension (%) | 9.4 | 12.8 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 16.5 | 18.1 |

| Arthritis (%) | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| Depression (%) | 10.2 | 10.1 |

| Pulmonary disease (%) | 6.6 | 7.6 |

| Polypharmacy (%) | 2.0 | 2.2 |

| Personality scores (range, 0 to 10), mean (SD) | ||

| Competitiveness | 7.0 (1.7) | 6.9 (1.8) |

| Anxiety | 6.0 (2.2) | 6.0 (2.2) |

| Phycological dependence | 3.6 (2.8) | 3.7 (2.9) |

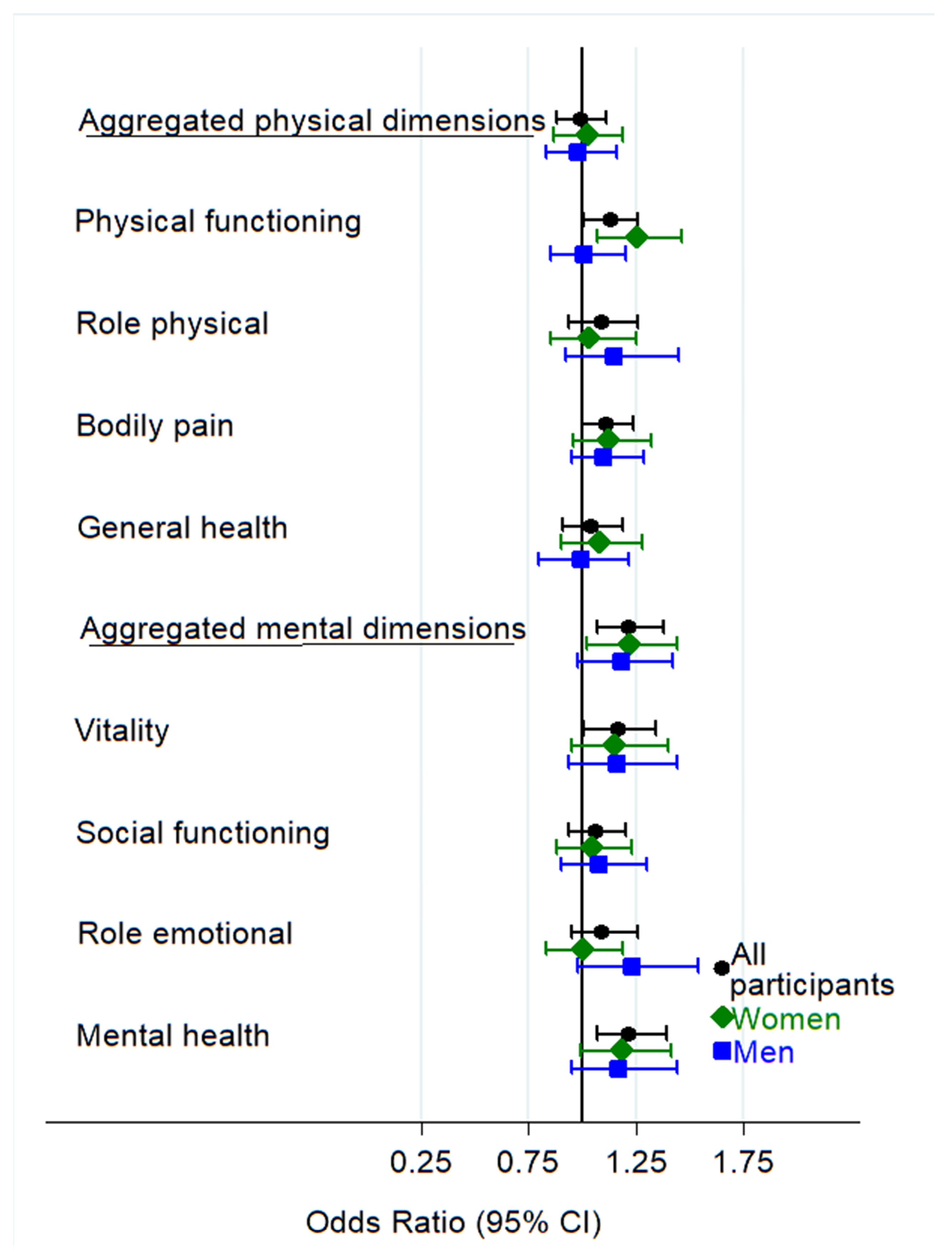

| All Participants | Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD/No BD | 3105/6037 | p-Value | 1391/3772 | p-Value | 1714/2265 | p-Value | p for Interaction | |

| Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Aggregated physical dimensions | Model 1 | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 0.960 | 1.02 (0.88–1.20) | 0.772 | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) | 0.923 | 0.957 |

| Model 2 | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.881 | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 0.897 | 0.99 (0.83–1.17) | 0.896 | 0.904 | |

| Physical functioning | Model 1 | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | 0.020 | 1.24 (1.07–1.43) | 0.004 | 1.04 (0.89–1.21) | 0.623 | 0.654 |

| Model 2 | 1.13 (1.00–1.26) | 0.041 | 1.25 (1.07–1.46) | 0.006 | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 0.895 | 0.290 | |

| Role physical | Model 1 | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) | 0.213 | 1.02 (0.85–1.24) | 0.806 | 1.17 (0.93–1.47) | 0.170 | 0.298 |

| Model 2 | 1.09 (0.94–1.26) | 0.258 | 1.03 (0.85–1.25) | 0.784 | 1.15 (0.92–1.45) | 0.226 | 0.405 | |

| Bodily pain | Model 1 | 1.14 (1.03–1.27) | 0.013 | 1.14 (0.98–1.33) | 0.099 | 1.14 (0.99–1.32) | 0.070 | 0.657 |

| Model 2 | 1.11 (1.00–1.24) | 0.061 | 1.12 (0.95–1.31) | 0.165 | 1.10 (0.95–1.29) | 0.208 | 0.767 | |

| General health | Model 1 | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | 0.561 | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 0.667 | 1.02 (0.84–1.23) | 0.836 | 0.193 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 0.535 | 1.07 (0.90–1.28) | 0.430 | 0.99 (0.80–1.21) | 0.899 | 0.584 |

| All Participants | Women | Men | p for Interaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD/No BD | 3105/6037 | p-Value | 1391/3772 | p-Value | 1714/2265 | p-Value | ||

| Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Aggregated mental dimensions | Model 1 | 1.27 (1.12–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.06–1.48) | 0.008 | 1.24 (1.04–1.47) | 0.015 | 0.223 |

| Model 2 | 1.21 (1.07–1.37) | 0.002 | 1.22 (1.02–1.44) | 0.026 | 1.18 (0.98–1.41) | 0.084 | 0.375 | |

| Vitality | Model 1 | 1.27 (1.14–1.42) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.01–1.37) | 0.039 | 1.36 (1.16–1.60) | <0.001 | 0.094 |

| Model 2 | 1.17 (1.01–1.34) | 0.031 | 1.15 (0.95–1.40) | 0.141 | 1.16 (0.94–1.44) | 0.156 | 0.799 | |

| Social functioning | Model 1 | 1.09 (0.98–1.23) | 0.120 | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 0.468 | 1.12 (0.94–1.33) | 0.204 | 0.486 |

| Model 2 | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 0.327 | 1.04 (0.88–1.23) | 0.626 | 1.08 (0.90–1.30) | 0.419 | 0.480 | |

| Role emotional | Model 1 | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) | 0.142 | 0.99 (0.83–1.18) | 0.938 | 1.27 (1.02–1.58) | 0.036 | 0.138 |

| Model 2 | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) | 0.206 | 0.99 (0.83–1.19) | 0.948 | 1.23 (0.98–1.54) | 0.073 | 0.223 | |

| Mental health | Model 1 | 1.29 (1.14–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.03–1.45) | 0.021 | 1.30 (1.07–1.58) | 0.008 | 0.025 |

| Model 2 | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | 0.004 | 1.18 (0.99–1.41) | 0.069 | 1.18 (0.96–1.45) | 0.121 | 0.143 |

| Multivariable-Adjusted * OR (95% CI) | p-Value | p for Interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with comorbidities (n = 3757) | Aggregated physical dimensions | 1.11 (0.91–1.35) | 0.297 | 0.219 |

| Aggregated mental dimensions | 1.28 (1.05–1.56) | 0.015 | 0.368 | |

| Participants without comorbidities (n = 5235) | Aggregated physical dimensions | 0.93 (0.81–1.08) | 0.359 | 0.219 |

| Aggregated mental dimensions | 1.16 (0.99–1.37) | 0.062 | 0.368 | |

| Age ≥ 50 (n = 1580) | Aggregated physical dimensions | 1.05 (0.70–1.58) | 0.821 | 0.641 |

| Aggregated mental dimensions | 1.29 (0.93–1.79) | 0.123 | 0.613 | |

| Age < 50 (n = 7412) | Aggregated physical dimensions | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 0.707 | 0.641 |

| Aggregated mental dimensions | 1.21 (1.05–1.38) | 0.007 | 0.613 | |

| Alcohol intake >5 g/day (n = 4448) | Aggregated physical dimensions | 0.95 (0.81–1.12) | 0.558 | 0.728 |

| Aggregated mental dimensions | 1.17 (0.99–1.38) | 0.067 | 0.786 | |

| Alcohol intake ≤5 g/day (n = 4544) | Aggregated physical dimensions | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) | 0.703 | 0.728 |

| Aggregated mental dimensions | 1.27 (1.05–1.55) | 0.016 | 0.786 |

| All Participants Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Women Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Men Multivariable-Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main analysis | Aggregated physical dimensions | Model 1 | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 0.960 | 1.02 (0.88–1.20) | 0.772 | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) | 0.923 |

| Model 2 | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.881 | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 0.897 | 0.99 (0.83–1.17) | 0.896 | ||

| Aggregated mental dimensions | Model 1 | 1.27 (1.12–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.06–1.48) | 0.008 | 1.24 (1.04–1.47) | 0.015 | |

| Model 2 | 1.21 (1.07–1.37) | 0.002 | 1.22 (1.02–1.44) | 0.026 | 1.18 (0.98–1.41) | 0.084 | ||

| With those with comorbidities | Aggregated physical dimensions | Model 1 | 1.01 (0.91–1.13) | 0.805 | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 0.447 | 0.99 (0.85–1.16) | 0.940 |

| Model 2 | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | 0.854 | 1.05 (0.90–1.23) | 0.527 | 0.99 (0.85–1.17) | 0.945 | ||

| Aggregated mental dimensions | Model 1 | 1.27 (1.14–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.03–1.44) | 0.022 | 1.23 (1.05–1.45) | 0.012 | |

| Model 2 | 1.22 (1.08–1.37) | 0.001 | 1.18 (1.02–1.37) | 0.029 | 1.18 (1.00–1.41) | 0.056 | ||

| With abstainers as non-expose | Aggregated physical dimensions | Model 1 | 1.02 (0.92–1.14) | 0.691 | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 0.461 | 1.01 (0.87–1.19) | 0.867 |

| Model 2 | 1.02 (0.91–1.14) | 0.730 | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 0.489 | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 0.964 | ||

| Aggregated mental dimensions | Model 1 | 1.30 (1.16–1.46) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.10–1.53) | 0.002 | 1.23 (1.04–1.45) | 0.016 | |

| Model 2 | 1.24 (1.10–1.40) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.06–1.48) | 0.009 | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | 0.100 | ||

| With those with comorbidities and abstainers | Aggregated physical dimensions | Model 1 | 1.02 (0.92–1.14) | 0.639 | 1.09 (0.95–1.27) | 0.226 | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) | 0.872 |

| Model 2 | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 0.642 | 1.09 (0.94–1.27) | 0.236 | 0.98 (0.84–1.14) | 0.819 | ||

| Aggregated mental dimensions | Model 1 | 1.28 (1.15–1.43) | 0.000 | 1.26 (1.07–1.47) | 0.004 | 1.22 (1.04–1.43) | 0.012 | |

| Model 2 | 1.22 (1.09–1.37) | 0.001 | 1.20 (1.02–1.41) | 0.029 | 1.17 (0.99–1.39) | 0.061 | ||

| Without binge-drinkers only on special occasions | Aggregated physical dimensions | Model 1 | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 0.529 | 1.00 (0.84–1.18) | 0.963 | 0.95 (0.81–1.13) | 0.593 |

| Model 2 | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 0.465 | 0.99 (0.83–1.18) | 0.929 | 0.94 (0.79–1.12) | 0.485 | ||

| Aggregated mental dimensions | Model 1 | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | 0.000 | 1.26 (1.05–1.51) | 0.014 | 1.30 (1.08–1.57) | 0.005 | |

| Model 2 | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) | 0.001 | 1.20 (1.00–1.46) | 0.055 | 1.25 (1.03–1.52) | 0.022 |

| Multivariable-Adjusted* Mean (95% CI) for Non-Binge-Drinkers | Multivariable-Adjusted * Mean (95% CI) for Binge-Drinkers | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregated physical dimensions | 53.09 (52.94–53.24) | 52.95 (52.73–53.17) | 0.310 |

| Physical functioning | 94.77 (94.55–95.00) | 94.38 (94.06–94.70) | 0.062 |

| Role physical | 91.78 (91.17–92.38) | 91.57 (90.70–92.44) | 0.716 |

| Bodily pain | 78.87 (78.39–79.35) | 78.12 (77.43–78.81) | 0.093 |

| General health | 76.03 (75.70–76.36) | 75.59 (75.11–76.06) | 0.147 |

| Aggregated mental dimensions | 49.70 (49.50–49.91) | 49.35 (49.05–49.64) | 0.064 |

| Vitality | 66.32 (65.96–66.67) | 65.78 (65.28–66.29) | 0.105 |

| Social functioning | 91.71 (91.31–92.10) | 90.94 (90.38–91.50) | 0.035 |

| Role emotional | 89.68 (89.04–90.33) | 89.26 (88.34–90.19) | 0.485 |

| Mental health | 76.74 (76.44–77.05) | 76.08 (75.65–76.52) | 0.020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perez-Araluce, R.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Toledo, E.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Barbería-Latasa, M.; Gea, A. Effect of Binge-Drinking on Quality of Life in the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) Cohort. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051072

Perez-Araluce R, Bes-Rastrollo M, Martínez-González MÁ, Toledo E, Ruiz-Canela M, Barbería-Latasa M, Gea A. Effect of Binge-Drinking on Quality of Life in the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) Cohort. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051072

Chicago/Turabian StylePerez-Araluce, Rafael, Maira Bes-Rastrollo, Miguel Ángel Martínez-González, Estefanía Toledo, Miguel Ruiz-Canela, María Barbería-Latasa, and Alfredo Gea. 2023. "Effect of Binge-Drinking on Quality of Life in the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) Cohort" Nutrients 15, no. 5: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051072

APA StylePerez-Araluce, R., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Martínez-González, M. Á., Toledo, E., Ruiz-Canela, M., Barbería-Latasa, M., & Gea, A. (2023). Effect of Binge-Drinking on Quality of Life in the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) Cohort. Nutrients, 15(5), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051072