Outcomes of a Caregiver-Focused Short Message Service (SMS) Intervention to Reduce Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Rural Caregivers and Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Description

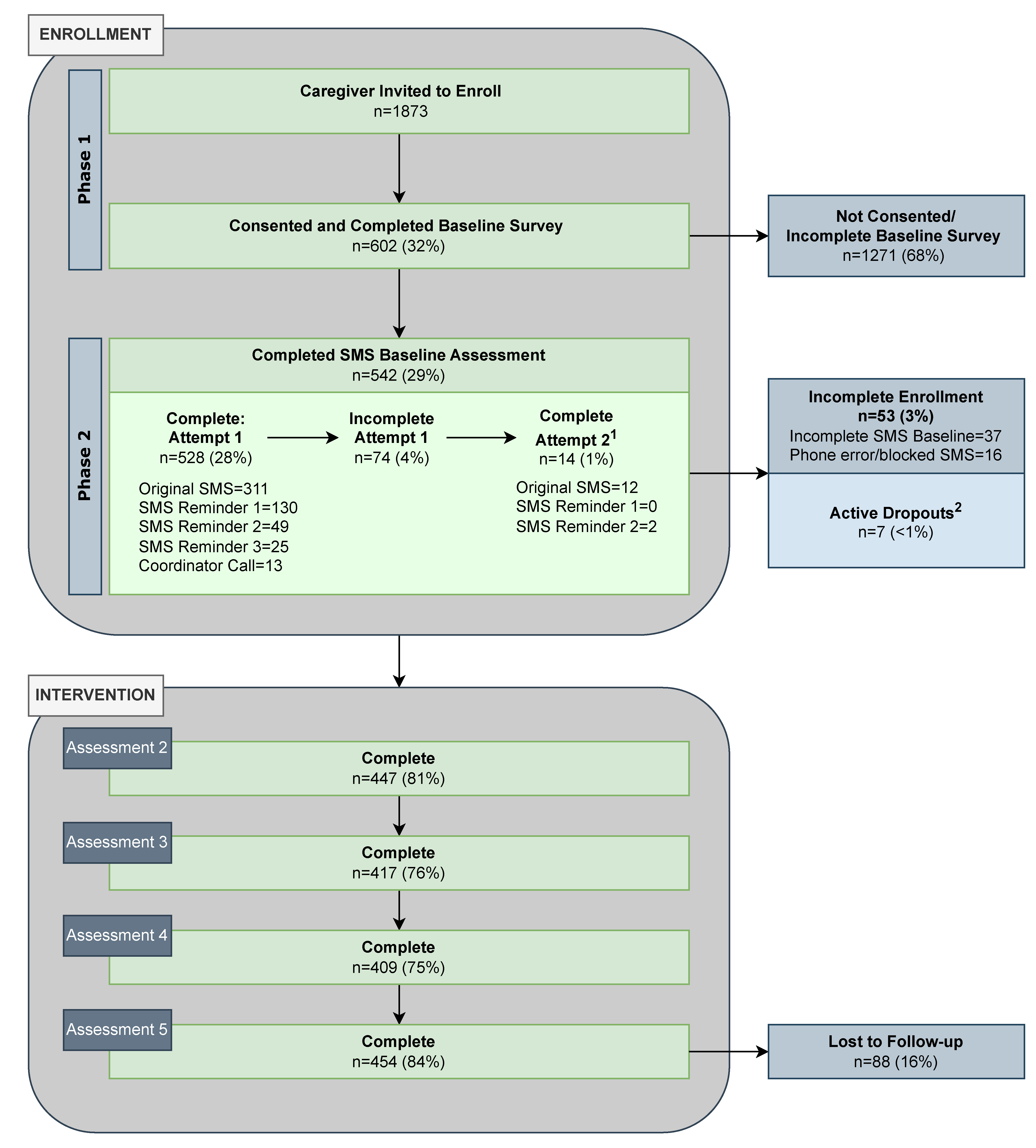

2.2. Recruitment and Enrollment Procedures

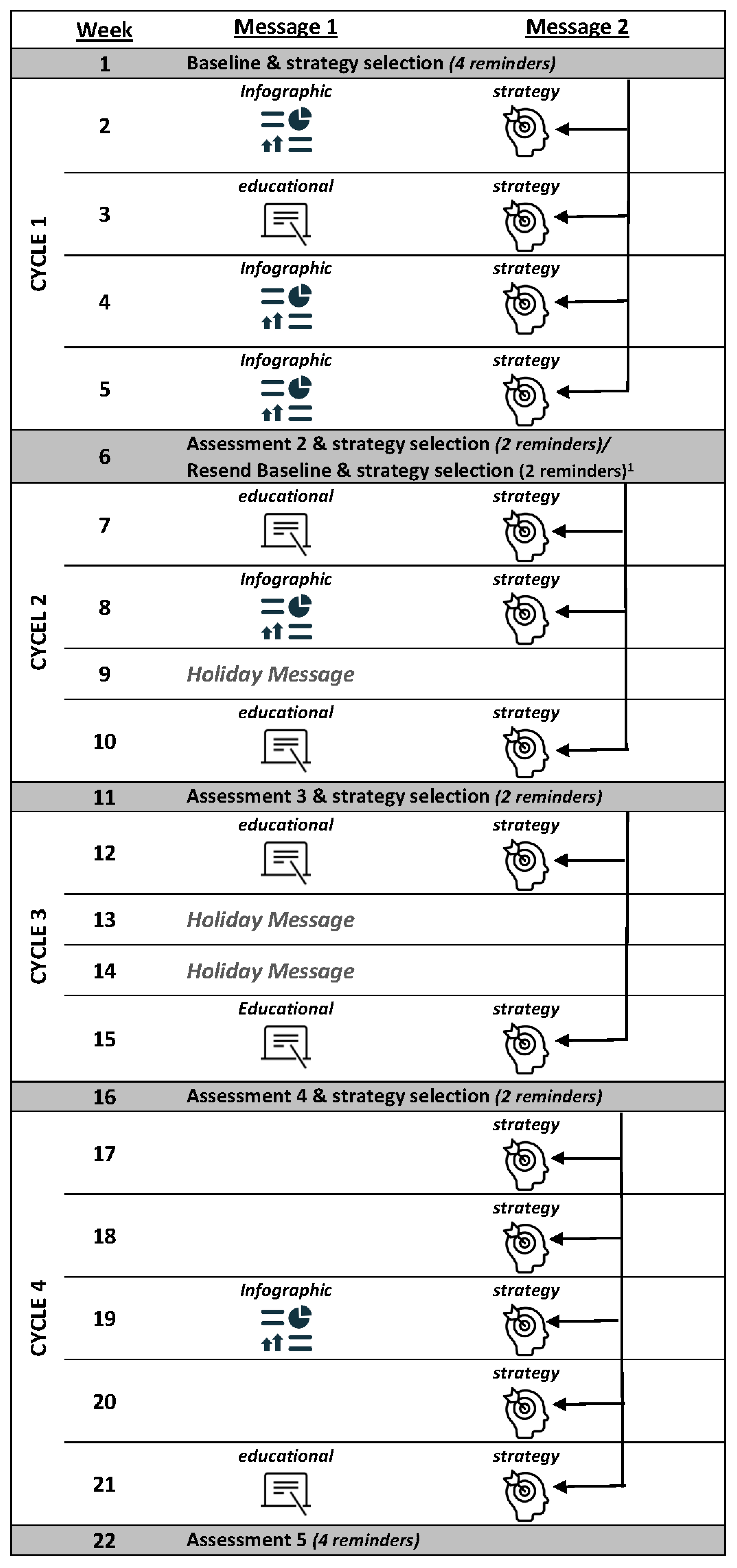

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Implementation Processes

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Caregiver Enrollment, Demographics, and Retention

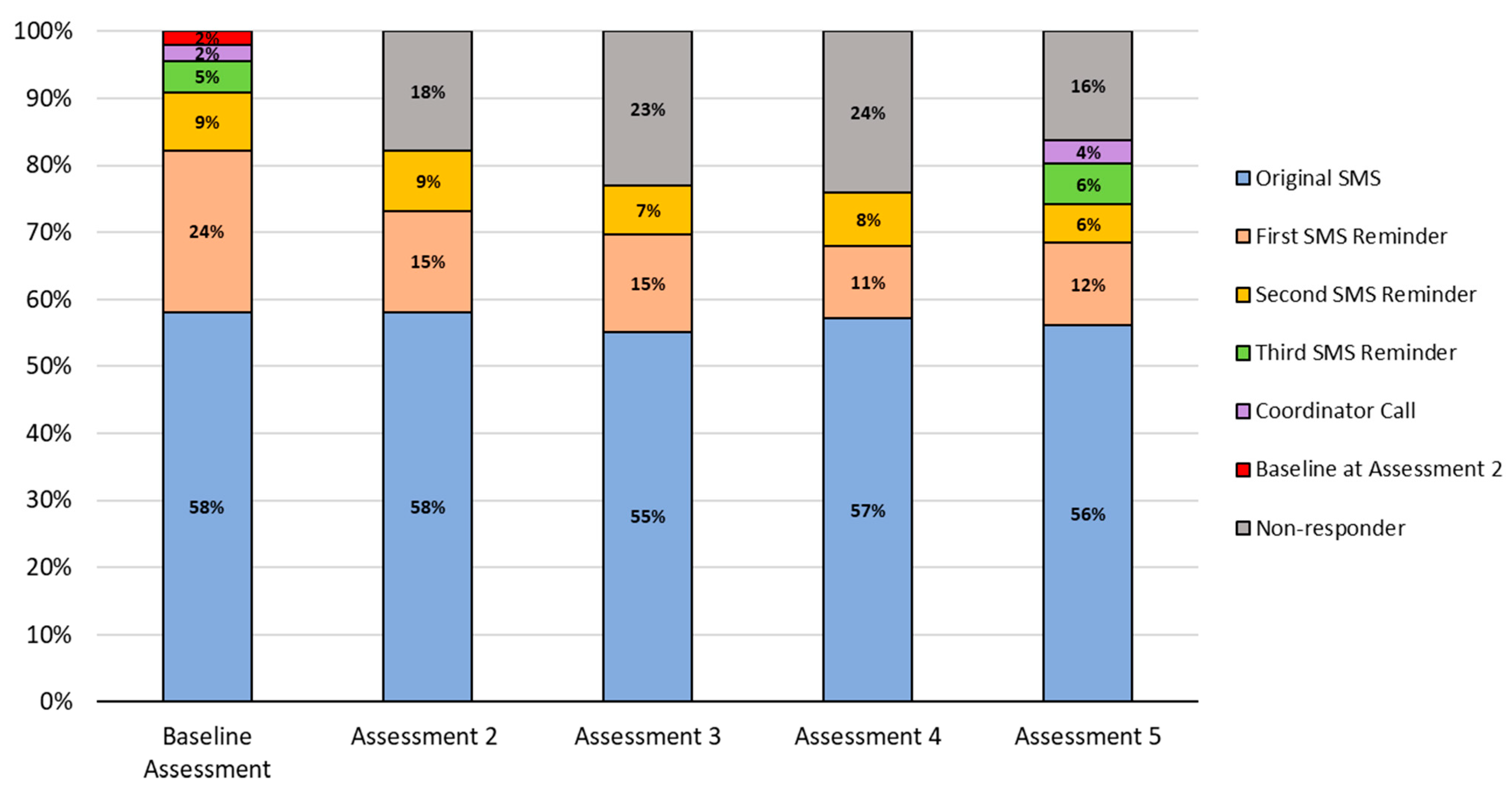

3.2. Enrolled Caregiver Engagement with SMS Intervention Messages

3.2.1. SMS Intervention Assessment Completion: Assessments 2 through 5

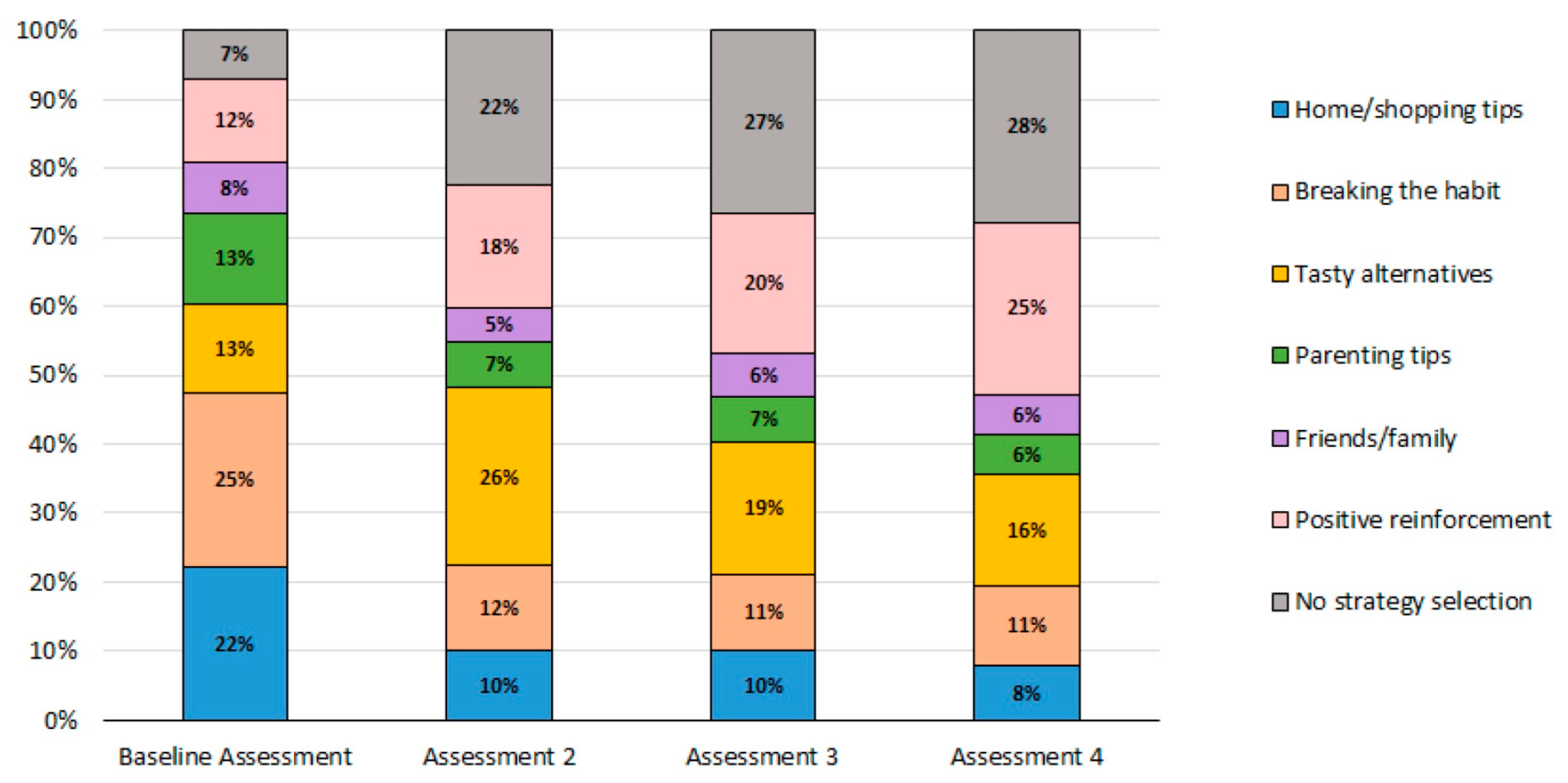

3.2.2. Caregiver Strategy Message Selection: Topics Related to Barriers for Reducing SSB

3.2.3. Caregiver Engagement with Educational Infographic Messages

3.3. Changes in SSB Intake Frequency

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosinger, A.; Herrick, K.A.; Gahche, J.J.; Park, S. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption among US Youth, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2017, 271, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, H.; Porter, K.J.; Hecht, E.; Harris, P.; Kraak, V.; Zoellner, J. Kids SIPsmartER: A feasibility study to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among middle school youth in Central Appalachia. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1386–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoellner, J.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Davy, B.M.; Chen, Y.-C.-Y.; You, W. Exploring the theory of planned behavior to explain sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.S.; Pan, A.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; O’Connor, L.; Ye, Z.; Mursu, J.; Hayashino, Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Forouhi, N.G. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. Br. Med. J. 2015, 351, h3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheungpasitporn, W.; Thongprayoon, C.; Edmonds, P.J.; Srivali, N.; Ungprasert, P.; Kittanamongkolchai, W.; Erickson, S.B. Sugar and artificially sweetened soda consumption linked to hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2015, 37, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabé, E.; Vehkalahti, M.M.; Sheiham, A.; Aromaa, A.; Suominen, A.L. Sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries in adults: A 4-year prospective study. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhas, M.; Porter, K.J.; Hedrick, V.; Zoellner, J.M. Using a socioecological approach to identify factors associated with adolescent sugar-sweetened beverage intake. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Ogden, J. Children’s eating attitudes and behaviour: A study of the modelling and control theories of parental influence. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 19, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.W.; Miller, J.; Larson, N.I.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Story, M.T.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Multicontextual correlates of adolescent sugar-sweetened beverage intake. Eat. Behav. 2018, 30, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.L.; DiClemente, R.; Snell, S. Overcoming the triad of rural health disparities: How local culture, lack of economic opportunity, and geographic location instigate health disparities. Health Educ. J. 2014, 73, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, K.J.; Noar, S.M.; Iannarino, N.T.; Harrington, N.G. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson-Lewis, C.; Darville, G.; Mercado, R.E.; Howell, S.; Di Maggio, S. mHealth technology use and implications in historically underserved and minority populations in the United States: Systematic literature review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, L.C.; Fortuna, K.L.; Jones, C.; Walker, R.; Hayes, S.N.; Patten, C.A.; Cooper, L.A. Back to the future: Achieving health equity through health informatics and digital health. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e14512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Militello, L.K.; Kelly, S.A.; Melnyk, B.M. Systematic review of text-messaging interventions to promote healthy behaviors in pediatric and adolescent populations: Implications for clinical practice and research. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2012, 9, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militello, L.; Melnyk, B.M.; Hekler, E.B.; Small, L.; Jacobson, D.; Shepherd, M.; Chung, C.-F.; Evans, W.; Fanning, J. Automated behavioral text messaging and face-to-face intervention for parents of overweight or obese preschool children: Results from a pilot study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.T.W.; Wadham, A.; Jiang, Y.; Whittaker, R.; Stasiak, K.; Shepherd, M.; Bullen, C. Effect of MyTeen SMS-based mobile intervention for parents of adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. 2019, 2, e1911120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, C.; Thompson, D. Family TXT: Feasibility and acceptability of a mHealth obesity prevention program for parents of pre-adolescent African American girls. Children 2018, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Harris, K.; Dybdal, L.; Malich, J.; Bodnar, B.; Hall, E. Feasibility of text messaging to promote child health in a rural community on an American Indian reservation. Health Educ. J. 2019, 78, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoory, L.; Yaros, R.A.; Prado, A.A.; Roberts, E.; Briones, R.L. Piloting Health text messages for rural low-income mothers: Effects of source similarity and simple action steps. Health Promot. Pract. 2016, 17, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.A.; Cho, J. Has the digital health divide widened? Trends of health-related internet use among older adults from 2003 to 2011. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. Mobile Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Pakter, A.; Chen, L.-L. The daily text: Increasing parental involvement in education with mobile text messaging. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2013, 41, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Duque, L.; Huffman, J.C.; Healy, B.C.; Celano, C.M. Text message interventions for physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 58, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naughton, F.; Riaz, M.; Sutton, S. Response parameters for SMS text message assessments among pregnant and general smokers participating in SMS cessation trials. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, D.A.; Cushing, C.C.; Fritz, A.; Amaro, C.M.; Ortega, A. Mobile health interventions for improving health outcomes in youth: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, A.; Reicks, M. A newsletter/text message intervention promoting beverage-related parenting practices: Pilot test results. Health Promot. Pract. 2019, 20, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Garcia, E.J.; Evans, C.E.L.; Prestwich, A.; Sykes-Muskett, B.J.; Hooson, J.; Cade, J.E. Interventions to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages or increase water intake: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, H.; Porter, K.; Estabrooks, P.; Zoellner, J. A systematic review to assess sugar-sweetened beverage interventions for children and adolescents across the socioecological model. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1295–1307.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.M.; Porter, K.J.; You, W.; Chow, P.I.; Ritterband, L.M.; Yuhas, M.; Loyd, A.; McCormick, B.A.; Brock, D.-J.P. Kids SIPsmartER, a cluster randomized controlled trial and multi-level intervention to improve sugar-sweetened beverages behaviors among Appalachian middle-school students: Rationale, design & methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2019, 83, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, V.E.; Savla, J.; Comber, D.L.; Flack, K.D.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Nsiah-Kumi, P.A.; Ortmeier, S.; Davy, B.M. Development of a brief questionnaire to assess habitual beverage intake (BEVQ-15): Sugar-sweetened beverages and total beverage energy intake. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhas, M.; Porter, K.J.; Brock, D.-J.P.; Loyd, A.; A McCormick, B.; Zoellner, J.M. Development and pilot testing of text messages to help reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake among rural caregivers and adolescents: Mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e14785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, S.; Ferisin, S.; Sharifi, M.; Steinberg, D.; Bennett, G.; Wolin, K.Y.; Horan, C.; Koziol, R.; Marshall, R.; Taveras, E.M. Development and implementation of an interactive text messaging campaign to support behavior change in a childhood obesity randomized controlled trial. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezami, B.T.; Ward, D.S.; Lytle, L.A.; Ennett, S.T.; Tate, D.F. A mHealth randomized controlled trial to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake in preschool-aged children. Pediatr. Obes. 2018, 13, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Brockman, J.L.; Harari, N.; Perez-Escamilla, R. Lactation advice through texting can help (LATCH): An analysis of intensity of engagement via two-way text messaging. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 650.18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pila, S.; Lauricella, A.R.; Wartella, E. Using short message (SMS) and multimedia messaging (MMS) to encourage positive parent–child engagement around literacy and language development. Mob. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanasco, A.A.; Miller, Y.D.; Fjeldsoe, B.S.; Marshall, A.L. Preventive health behavior change text message interventions: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina-Im, L.-A.; Beaulieu, D.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Boucher, D.; Sirois, C.; Dugas, M.; Provencher, V. Efficacy of school-based interventions aimed at decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2416–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, R.; Bonell, C.; E Jones, H.; Campbell, R. Obesity prevention and the Health promoting Schools framework: Essential components and barriers to success. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grutzmacher, S.K.; Duru, E.B.; Speirs, K.E.; Worthington, L.; Munger, A.L.; Lachenmayr, L.A. Using text messages to engage low-income parents in school-based nutrition education. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, M.; Habibullah, N.K.; Butler, C.E. The impact of COVID-19 on clinical trials. Ann. Surg. 2020, 272, e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heers, M.; Lipps, O. Overwhelmed by learning in lockdown: Effects of COVID-19-enforced homeschooling on parents’ wellbeing. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalil, A.; Mayer, S.; Shah, R. Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Family Dynamics in Economically Vulnerable Households; Working Paper No 2020-143; University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper: Chicago, IL, USA, 5 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, A.; Ogurlu, U.; Logan, N.; Cook, P. COVID-19 and remote learning: Experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. Am. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, K.; Jacobsen, L.A. The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview from the 2015–2019 American Community Survey; Chartbook; Appalachian Regional Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A.K.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Bernhardt, J.M. Mobile text messaging for health: A systematic review of reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, T.; Walton, A.E.; Collins, L.M.; Klasnja, P.; Lanza, S.T.; Nahum-Shani, I.; Rabbi, M.; Russell, M.A.; Walton, M.A.; Yoo, H.; et al. The microrandomized trial for developing digital interventions: Experimental design and data analysis considerations. Psychol. Methods 2022, 27, 874–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rideout, V.; Peebles, A.; Mann, S.; Robb, M.B. Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens; Common Sense: San Francisco, CA, USA, 3 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Infographic | Click Rate | Text Message | Accompanying Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesson 1: Traffic Light | 201 (37%) | KidsSIPsmartER: Sugary drinks include: soda/pop, sweet tea, sports drinks, juices, and energy drinks. Think about which ones you drink. Click this secure link to see more! [Image Link] |  |

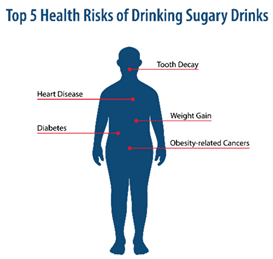

| Lesson 3: Health Risks | 143 (26%) | KidsSIPsmartER: Trying to be healthy? Drinking fewer sugary drinks can prevent tooth decay, weight gain, and heart problems. Click this secure link to see all the ways sugary drinks can harm your health. [Image Link] |  |

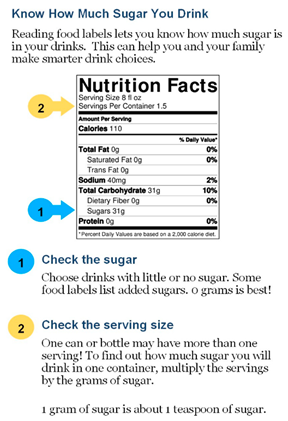

| Lesson 4: Nutrition Facts Label | 128 (24%) | KidsSIPsmartER: The nutrition label helps you find grams of sugar. It tells the truth, unlike logos & pics on the front of the bottle. Click this secure link to see a quick guide to help you practice with your family. [Image Link] |  |

| Lesson 6: This or That | 153 (28%) | KidsSIPsmartER: Don’t drink your calories! Use your calories to eat more fruits and veggies. Click this secure link to see what you could replace with a sugary drink. [Image Link] |  |

| Lesson 11: Saving Money | 125 (23%) | KidsSIPsmartER: The cost of sugary drinks really adds up! Spending $1 a day on a pop can add up to $365 over a year. Click this secure link to see how it piles up! [Image Link] |  |

| n | Baseline Daily SSB Frequency 1 Mean (SD) | Assessment 5 Daily SSB Frequency Mean (SD) | Mean Change in Daily SSB Frequency (SE) | Effect Size | Wald Test Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All caregivers and children | ||||||

| Caregiver intake (times/day) | 454 | 0.64 (0.71) | 0.33 (0.51) | −0.32 (0.03) | d = 0.51 | 12.21 * |

| Child intake (times/day) | 454 | 0.54 (0.50) | 0.28 (0.34) | −0.26 (0.02) | d = 0.53 | 10.79 * |

| Sub-sample of SSB consumers at Baseline 2 | ||||||

| Caregiver intake (times/day) | 325 | 0.87 (0.73) | 0.42 (0.57) | −0.45 (0.04) | d = 0.65 | 14.86 * |

| Child intake (times/day) | 344 | 0.69 (0.48) | 0.34 (0.36) | −0.35 (0.03) | d = 0.67 | 12.27 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brock, D.-J.P.; Yuhas, M.; Porter, K.J.; Chow, P.I.; Ritterband, L.M.; Tate, D.F.; Zoellner, J.M. Outcomes of a Caregiver-Focused Short Message Service (SMS) Intervention to Reduce Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Rural Caregivers and Adolescents. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081957

Brock D-JP, Yuhas M, Porter KJ, Chow PI, Ritterband LM, Tate DF, Zoellner JM. Outcomes of a Caregiver-Focused Short Message Service (SMS) Intervention to Reduce Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Rural Caregivers and Adolescents. Nutrients. 2023; 15(8):1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081957

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrock, Donna-Jean P., Maryam Yuhas, Kathleen J. Porter, Philip I. Chow, Lee M. Ritterband, Deborah F. Tate, and Jamie M. Zoellner. 2023. "Outcomes of a Caregiver-Focused Short Message Service (SMS) Intervention to Reduce Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Rural Caregivers and Adolescents" Nutrients 15, no. 8: 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081957

APA StyleBrock, D.-J. P., Yuhas, M., Porter, K. J., Chow, P. I., Ritterband, L. M., Tate, D. F., & Zoellner, J. M. (2023). Outcomes of a Caregiver-Focused Short Message Service (SMS) Intervention to Reduce Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Rural Caregivers and Adolescents. Nutrients, 15(8), 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081957