The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies and Emotion Regulation in the Relationship between Impulsivity, Metacognition, and Eating Disorders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Eating Disorders

2.2.2. Metacognitive Strategies

2.2.3. Impulsivity

2.2.4. Coping Strategies

2.2.5. Emotion Regulation

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hambleton, A.; Pepin, G.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; Byrne, S.; et al. Psychiatric and Medical Comorbidities of Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review of the Literature. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Khan, M.A.B. Prevalence of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury, Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts, Suicide Mortality in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat. Disord. 2023, 31, 487–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagielska, G.; Kacperska, I. Outcome, Comorbidity and Prognosis in Anorexia Nervosa. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eeden, A.E.; Van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Review of the Burden of Eating Disorders: Mortality, Disability, Costs, Quality of Life, and Family Burden. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fifth Edition Text Revision. DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Himmerich, H.; Bentley, J.; Kan, C.; Treasure, J. Genetic Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: An Update and Insights into Pathophysiology. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kober, H.; Boswell, R.G. Potential Psychological & Neural Mechanisms in Binge Eating Disorder: Implications for Treatment. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 60, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfoukha, M.M.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Banihani, M.A. Social and Psychological Factors Related to Risk of Eating Disorders Among High School Girls. J. Sch. Nurs. 2017, 35, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, R.S. The Role of Sociocultural Factors in the Etiology of Eating Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciberti, A.; Cavalletti, M.; Palagini, L.; Mariani, M.G.; Dell’osso, L.; Mauri, M.; Maglio, A.; Mucci, F.; Marazziti, D.; Miniati, M. Decision-Making, Impulsiveness and Temperamental Traits in Eating Disorders. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slof-Op’t Landt, M.C.T.; Claes, L.; van Furth, E.F. Classifying Eating Disorders Based on “Healthy” and “Unhealthy” Perfectionism and Impulsivity. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boswell, R.G.; Grilo, C.M. General Impulsivity in Binge-Eating Disorder. CNS Spectr. 2021, 26, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, A.L.; Butler, G.K.L.; Nikčević, A.V. Impulsivity Dimensions and Their Associations with Disinhibited and Actual Eating Behaviour. Eat. Behav. 2023, 49, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, M.M.; Wiedemann, A.A.; Macdonald-Gagnon, G.; Potenza, M.N. Impulsivity and Compulsivity in Binge Eating Disorder: A Systematic Review of Behavioral Studies. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 110, 110318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker, N.M.; Azzam, L.A.B.; Zahran, R.M.; Hashem, R.E. Frequency of Binge Eating Behavior in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Its Relation to Emotional Regulation and Impulsivity. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 2497–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soidla, K.; Akkermann, K. Perfectionism and Impulsivity Based Risk Profiles in Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bénard, M.; Bellisle, F.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Julia, C.; Andreeva, V.A.; Etilé, F.; Reach, G.; Dechelotte, P.; Tavolacci, M.P.; Hercberg, S.; et al. Impulsivity Is Associated with Food Intake, Snacking, and Eating Disorders in a General Population. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, G.; Granero, R.; Misiolek, A.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Mallorqui-Bagué, N.; Lozano-Madrid, M.; Heras, M.V.D.L.; Sánchez, I.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Impact of Impulsivity and Therapy Response in Eating Disorders from a Neurophysiological, Personality and Cognitive Perspective. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Madrid, M.; Granero, R.; Lucas, I.; Sánchez, I.; Sánchez-González, J.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Moragas, L.; Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Tapia, J.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; et al. Impulsivity and Compulsivity in Gambling Disorder and Bulimic Spectrum Eating Disorders: Analysis of Neuropsychological Profiles and Sex Differences. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiaco, F.; Bruno, A.; Mento, C.; Cedro, C.; Pandolfo, G.; Muscatello, M.R.A. Impulsivity and Metacognition in a Psychiatric Population. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2022, 19, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, C.; So, S.H.W. Dysfunctional Metacognition across Psychopathologies: A Meta-Analytic Review. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 45, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamonniere, T.; Varescon, I. Metacognitive Beliefs in Addictive Behaviours: A Systematic Review. Addict. Behav. 2018, 85, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauregui, P.; Urbiola, I.; Estevez, A. Metacognition in Pathological Gambling and Its Relationship with Anxious and Depressive Symptomatology. J. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 32, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, S.; Mansueto, G.; Ruggiero, G.M.; Caselli, G.; Sassaroli, S.; Spada, M.M. Metacognitive Beliefs across Eating Disorders and Eating Behaviours: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 1254–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; Bianchi, D.; Pompili, S.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R. Metacognition, Emotional Functioning and Binge Eating in Adolescence: The Moderation Role of Need to Control Thoughts. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2018, 23, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limbers, C.A.; Greenwood, E.; Shea, K.; Fergus, T.A. Metacognitive Beliefs and Emotional Eating in Adolescents. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 2281–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olstad, S.; Solem, S.; Hjemdal, O.; Hagen, R. Metacognition in Eating Disorders: Comparison of Women with Eating Disorders, Self-Reported History of Eating Disorders or Psychiatric Problems, and Healthy Controls. Eat. Behav. 2015, 16, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, S.; Azzi, V.; Bianchi, D.; Laghi, F.; Pompili, S.; Malaeb, D.; Obeid, S.; Soufia, M.; Hallit, S. Exploring the Relationship between Dysfunctional Metacognitive Processes and Orthorexia Nervosa: The Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation Strategies. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, E.; Rushford, N.; Soon, S.; Mcdermott, C. Dysfunctional Metacognition and Drive for Thinness in Typical and Atypical Anorexia Nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgantopoulos, G.; Konstantakopoulos, G.; Michopoulos, I.; Dikeos, D.; Gonidakis, F. The Relationship between Metacognitive Beliefs and Symptoms in Eating Disorders. Psychiatriki 2020, 31, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapuppo, W.; Ruggiero, G.M.; Caselli, G.; Sassaroli, S. The Body of Cognitive and Metacognitive Variables in Eating Disorders: Need of Control, Negative Beliefs about Worry Uncontrollability and Danger, Perfectionism, Self-Esteem and Worry. Isr. J. Psychiatry 2018, 55, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aloi, M.; Rania, M.; Carbone, E.A.; Caroleo, M.; Calabrò, G.; Zaffino, P.; Nicolò, G.; Carcione, A.; Lo Coco, G.; Cosentino, C.; et al. Metacognition and Emotion Regulation as Treatment Targets in Binge Eating Disorder: A Network Analysis Study. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitti, C.; Rufino, K.; Goodwin, N.; Wagner, R. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation in Patients with Eating Disorders. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2016, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Testa, G.; Lozano-Madrid, M.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Granero, R.; Perales, J.C.; Navas, J.F.; Megías-Robles, A.; et al. Emotional and Non-emotional Facets of Impulsivity in Eating Disorders: From Anorexia Nervosa to Bulimic Spectrum Disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, M. Maladaptive Rumination as a Transdiagnostic Mediator of Vulnerability and Outcome in Psychopathology. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecuta, L.; Gardini, V.; Digiuseppe, R.; Tomba, E. Do Metacognitions Mediate the Relationship between Irrational Beliefs, Eating Disorder Symptoms and Cognitive Reappraisal? Psychother. Res. 2021, 31, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, A.; Danner, U.; Parks, M. Emotion Regulation in Binge Eating Disorder: A Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meule, A.; Richard, A.; Schnepper, R.; Reichenberger, J.; Georgii, C.; Naab, S.; Voderholzer, U.; Blechert, J. Emotion Regulation and Emotional Eating in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Eat. Disord. 2019, 29, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhail, M.E.; Kring, A.M. Emotion Regulation Strategy Use and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Daily Life. Eat. Behav. 2019, 34, 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworschak, C.; Polack, R.G.; Winschel, J.; Joormann, J.; Kober, H. Emotion Regulation and Disordered Eating Behaviour in Youths: Two Daily-Diary Studies. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2023, 31, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragantzopoulou, P.; Giannouli, V. Unveiling Anxiety Factors in Orthorexia Nervosa: A Qualitative Exploration of Fears and Coping Strategies. Healthcare 2024, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargabi, Z.H.; Nouri, R.; Moradi, A.; Sarami, G. Evaluation of Coping Styles, Metacognition and Their Relationship with Test Anxiety. J. Mazand. Univ. Med. Sci. 2014, 24, 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, M.; Barzegar, M.; Kouroshnia, M.; Khayyer, M. Investigating The Mediating Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies in The Relationship Between Meta-Cognitive Beliefs and Learning Anxiety. Iran. Evol. Educ. Psychol. J. 2021, 3, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkhani, S.; Hasani, J.; Akbari, M.; Panah, N.Y. Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship of Metacognitive Beliefs and Attachment Styles with Risky Behaviors in Children of Iran-Iraq War Veterans with Psychiatric Disorders. Iran. J. Psychiatry Clin. Psychol. 2019, 25, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceren Yıldırım, J.; Bahtiyar, B. The Association between Metacognitions and Worry: The Mediator Role of Experiential Avoidance Strategies. J. Psychol. 2022, 156, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloom, M.; Yaghubi, H.; Mohammadkhani, S. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptom, Metacognition, Emotional Schema and Emotion Regulation: A Structural Equation Model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 88, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Dai, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, L.; Dai, B.; Liu, X. The Mediating Role of Coping Styles on Impulsivity, Behavioral Inhibition/Approach System, and Internet Addiction in Adolescents From a Gender Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacadini França, A.; Samra, R.; Magalhães Vitorino, L.; Waltz Schelini, P. The Relationship Between Mental Health, Metacognition, and Emotion Regulation in Older People. Clin. Gerontol. 2024, 47, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Psychiatric and Medical Correlates of DSM-5 Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of Adults in the United States. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, A.; Matthews, G. Modelling Cognition in Emotional Disorder: The S-REF Model. Behav. Res. Ther. 1996, 34, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Sagar, R.; Kaloiya, G.; Mehta, M. The Scope of Metacognitive Therapy in the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. Cureus 2022, 14, e23424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, B.; Jonassen, R.; Stiles, T.C.; Landrø, N.I. Dysfunctional Metacognitive Beliefs Are Associated with Decreased Executive Control. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 259977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A. Breaking the Cybernetic Code: Understanding and Treating the Human Metacognitive Control System to Enhance Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.E.; Racine, S.E. Emotion Regulation Difficulties as Common and Unique Predictors of Impulsive Behaviors in University Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Ypsilanti, A.; Powell, P.; Overton, P. The Roles of Impulsivity, Self-Regulation, and Emotion Regulation in the Experience of Self-Disgust. Motiv. Emot. 2019, 43, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan-Atalay, A.; Zeytun, D. The Association of Negative Urgency with Psychological Distress: Moderating Role of Proactive Coping Strategies. J. Psychol. 2020, 154, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, M.J.; Schiel, J.E.; Rosenbaum, D.; Hautzinger, M.; Fallgatter, A.J.; Ehlis, A.C. To Regulate or Not to Regulate: Emotion Regulation in Participants With Low and High Impulsivity. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 645052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; Pompili, S.; Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R. Dysfunctional Metacognition Processes as Risk Factors for Drunkorexia during Adolescence. J. Addict. Dis. 2020, 38, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strodl, E.; Markey, C.; Aimé, A.; Rodgers, R.F.; Dion, J.; Coco, G.L.; Gullo, S.; McCabe, M.; Mellor, D.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; et al. A Cross-Country Examination of Emotional Eating, Restrained Eating and Intuitive Eating: Measurement Invariance across Eight Countries. Body Image 2020, 35, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M. Eating Disorder Inventory—2; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lake Magdalene, FL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muro-Sans, P.; Amador-Campos, J.A.; Peró-Cebollero, M. Factor Structure of Eating Disorders Inventory-2 in a Spanish Sample. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2006, 11, e42–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Carcedo, L. Validación del Inventrio de Actividad Cognitiva en Los Trastornos de Nasiedad, Subescala Para el Trastorno Obsesivo-Compulsivo (IACTA-TOC); Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, E.S. Impulsiveness and Anxiety: Information Processing and Electroencephalograph Topography. J. Res. Pers. 1987, 21, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oquendo, M.A.; Baca-García, E.; Graver, R.; Morales, M.; Montalvan, V.; Mann, J.J. Spanish Adaptation of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11). Eur. J. Psychiatry 2001, 15, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, D.L.; Holroyd, K.A.; Reynolds, R.V.; Wigal, J.K. The Hierarchical Factor Structure of the Coping Strategies Inventory. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1989, 13, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-García, F.J.; Rodríguez-Franco, L.; García-Martínez, J. Adaptación Española Del Inventario de Estrategias de Afrontamiento. Actas Españolas Psiquiatr. 2007, 35, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervás, G.; Jódar, R. Adaptación Al Castellano de La Escala de Dificultades En La Regulación Emocional. Clínica Salud 2008, 19, 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Hillsdate: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall-Dahlgren, C.; Wisting, L.; Rø, Ø. Feeding and Eating Disorders in the DSM-5 Era: A Systematic Review of Prevalence Rates in Non-Clinical Male and Female Samples. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An Update on the Prevalence of Eating Disorders in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, W.L.; Shin, E.C.V.; Hazmi, H. Examining Gender Difference in Disordered Eating Behaviour and Its Associated Factors among College and University Students in Sarawak. Nutr. Health, 2022; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: The Role of Gender. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, B.S.; Hall, M.E.; Dias-Karch, C.; Haischer, M.H.; Apter, C. Gender Differences in Perceived Stress and Coping among College Students. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabras, C.; Mondo, M. Coping Strategies, Optimism, and Life Satisfaction among First-Year University Students in Italy: Gender and Age Differences. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 75, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiris, N.; Berle, D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Unified Protocol as a Transdiagnostic Emotion Regulation Based Intervention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 72, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludius, B.; Mennin, D.; Ehring, T. Emotion Regulation as a Transdiagnostic Process. Emotion 2020, 20, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Mistry, R.; Ran, G.; Wang, X. Relation between Emotion Regulation and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis Review. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igra, L.; Shilon, S.; Kivity, Y.; Atzil-Slonim, D.; Lavi-Rotenberg, A.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. Examining the Associations between Difficulties in Emotion Regulation and Symptomatic Outcome Measures among Individuals with Different Mental Disorders. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 944457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Agüera, Z.; Granero, R.; Jiménez-Múrcia, S.; Menchón, J.M.; Treasure, J.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Emotion Regulation as a Transdiagnostic Feature Among Eating Disorders: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Approach. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018, 26, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prefit, A.B.; Cândea, D.M.; Szentagotai-Tătar, A. Emotion Regulation across Eating Pathology: A Meta-Analysis. Appetite 2019, 143, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppanen, J.; Brown, D.; McLinden, H.; Williams, S.; Tchanturia, K. The Role of Emotion Regulation in Eating Disorders: A Network Meta-Analysis Approach. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 793094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmeyer, T.; Skunde, M.; Wu, M.; Bresslein, E.; Rudofsky, G.; Herzog, W.; Friederich, H.C. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation across the Spectrum of Eating Disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C.; Ha, C.; Carbone, C.; Kim, S.; Perry, K.; Williams, L.; Fonagy, P. Hypermentalizing in Adolescent Inpatients: Treatment Effects and Association With Borderline Traits. J. Personal. Disord. 2013, 27, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blatt, S.J.; Auerbach, J.S.; Behrends, R.S. Changes in the Representation of Self and Significant Others in the Treatment Process: Links between Representation, Internalization, and Mentalization. In Mind to Mind: Infant Research, Neuroscience, and Psychoanalysis; Jurist, E.L., Slade, A., Bergner, S., Eds.; Other Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 225–263. [Google Scholar]

- Rawal, A.; Park, R.J.; Williams, J.M.G. Rumination, Experiential Avoidance, and Dysfunctional Thinking in Eating Disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowdrey, F.A.; Park, R.J. The Role of Experiential Avoidance, Rumination and Mindfulness in Eating Disorders. Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwin, R.; Goldbacher, E.M.; Cardaciotto, L.A.; Gambrel, L.E. Negative Emotions and Emotional Eating: The Mediating Role of Experiential Avoidance. Eat. Weight Disord. 2017, 22, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espel-Huynh, H.M.; Muratore, A.F.; Virzi, N.; Brooks, G.; Zandberg, L.J. Mediating Role of Experiential Avoidance in the Relationship between Anxiety Sensitivity and Eating Disorder Psychopathology: A Clinical Replication. Eat. Behav. 2019, 34, 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, R.J.; Dunn, B.D.; Barnard, P.J. Schematic Models and Modes of Mind in Anorexia Nervosa I: A Novel Process Account. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2011, 4, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragantzopoulou, P.; Giannouli, V. “You Feel That You Are Stepping into a Different World”: Vulnerability and Biases in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2023, 25, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.; Hall, K.; Moulding, R.; Bryce, S.; Mildred, H.; Staiger, P.K. Emotion Regulation as a Transdiagnostic Treatment Construct across Anxiety, Depression, Substance, Eating and Borderline Personality Disorders: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzan, R.P.; Gilder, M.; Thompson, M.; Wade, T.D. A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial of Metacognitive Training with Adolescents Receiving Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 1820–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharaldsen, K.B.; Bru, E. Evaluating the Mindfulness-Based Coping Program: An Effectiveness Study Using a Mixed Model Approach. Ment. Illn. 2012, 4, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, R.; Mira, A.; Cormo, G.; Etchemendy, E.; Baños, R.; García-Palacios, A.; Ebert, D.D.; Franke, M.; Berger, T.; Schaub, M.P.; et al. An Internet Based Intervention for Improving Resilience and Coping Strategies in University Students: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Internet Interv. 2019, 16, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Sample (N = 1076) | Male (n = 233) | Female (n = 834) | p-Value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Age | 21.78 (5.10) | 25.19 (6.91) | 20.84 (4.00) | <0.001 | 0.768 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.98 (11.78) | 73.24 (10.50) | 58.84 (10.12) | <0.001 | 1.396 |

| High (m) | 1.66 (0.09) | 1.77 (0.07) | 1.63 (0.06) | <0.001 | 2.145 |

| BMI | 22.25 (3.24) | 23.25 (2.78) | 21.97 (3.32) | <0.001 | 0.419 |

| BMI categories | <0.001 | 0.142 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) a | 89 (8.44%) | 5 (2.16%) | 84 (10.19%) | ||

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) a | 792 (75.07%) | 176 (75.19%) | 616 (74.76%) | ||

| Overweight (25–29.9) a | 145 (13.74%) | 45 (19.48%) | 100 (12.14%) | ||

| Obesity (>30) a | 29 (2.75%) | 5 (2.16%) | 24 (2.91%) | ||

| Marital status a | <0.001 | 0.152 | |||

| Single | 993 (93.06%) | 209 (89.70%) | 784 (94.00%) | ||

| Married | 21 (1.97%) | 14 (6.01%) | 7 (0.84%) | ||

| Other | 53 (4.97%) | 10 (4.29%) | 43 (5.16%) | ||

| Working status a | <0.001 | 0.350 | |||

| Student | 839 (78.56%) | 120 (51.50%) | 719 (86.11%) | ||

| Worker | 218 (20.41%) | 106 (45.49%) | 112 (13.41%) | ||

| Other | 11 (1.03%) | 7 (3.00%) | 4 (0.48%) | ||

| Eating disorder | 157.88 (55.36) | 154.71 (51.05) | 158.65 (56.65) | 0.355 | 0.073 |

| Impulsivity | 66.72 (9.41) | 67.25 (9.28) | 66.52 (9.39) | 0.307 | 0.078 |

| Metacognition | 9.61 (6.30) | 10.21 (6.26) | 9.43 (6.29) | 0.092 | 0.124 |

| Coping strategies | |||||

| Problem-solving | 12.44 (4.57) | 12.61 (4.49) | 12.41 (4.58) | 0.560 | 0.044 |

| Self-criticism | 7.14 (5.25) | 7.59 (5.09) | 7.04 (5.29) | 0.160 | 0.106 |

| Emotional expression | 10.94 (4.81) | 10.00 (4.66) | 11.23 (4.80) | 0.001 | 0.260 |

| Wishful thinking | 13.03 (5.23) | 12.23 (5.31) | 13.27 (5.20) | 0.007 | 0.198 |

| Social support | 14.04 (5.09) | 13.07 (4.92) | 14.31 (5.11) | 0.001 | 0.247 |

| Cognitive restructuring | 10.83 (4.74) | 11.06 (4.90) | 10.78 (4.68) | 0.414 | 0.058 |

| Problem avoidance | 6.98 (4.10) | 7.27 (4.08) | 6.89 (4.09) | 0.200 | 0.093 |

| Social withdrawal | 5.98 (4.23) | 6.48 (4.24) | 5.82 (4.21) | 0.037 | 0.156 |

| Emotion regulation | 63.16 (19.28) | 61.53 (16.97) | 63.59 (19.85) | 0.120 | 0.112 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| 0.347 ** | ||||||||||

| 0.595 ** | 0.255 ** | |||||||||

| −0.291 ** | −0.169 ** | −0.167 ** | ||||||||

| 0.426 ** | 0.164 ** | 0.396 ** | −0.076 * | |||||||

| −0.163 ** | −0.059 | 0.028 | 0.389 ** | 0.043 | ||||||

| 0.328 ** | 0.079 * | 0.299 ** | −0.014 | 0.378 ** | 0.129 ** | |||||

| −0.284 ** | −0.091 ** | −0.159 ** | 0.356 ** | −0.153 ** | 0.437 ** | 0.055 | ||||

| −0.241 ** | −0.055 | −0.115 ** | 0.451 ** | −0.025 | 0.254 ** | −0.088 ** | 0.382 ** | |||

| 0.060 | 0.105 ** | 0.042 | −0.056 | 0.077 * | −0.066 * | 0.103 ** | 0.017 | 0.358 ** | ||

| 0.436 ** | 0.136 ** | 0.337 ** | −0.237 ** | 0.407 ** | −0.252 ** | 0.278 ** | −0.394 ** | −0.139 ** | 0.254 ** | |

| 0.714 ** | 0.393 ** | 0.595 ** | −0.259 ** | 0.417 ** | −0.068 * | 0.323 ** | −0.197 ** | −0.190 ** | 0.059 | 0.391 ** |

| β | p-Value | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||

| Impulsivity → Eating disorders | 0.075 | 0.002 | 0.169 | 0.714 |

| Impulsivity → Emotion regulation | 0.402 | <0.001 | 0.688 | 0.925 |

| Impulsivity → Problem-solving | −0.163 | <0.001 | −0.107 | −0.047 |

| Impulsivity → Self-criticism | 0.169 | <0.001 | 0.058 | 0.128 |

| Impulsivity → Emotion expression | −0.077 | 0.020 | −0.069 | −0.006 |

| Impulsivity → Wishful thinking | 0.087 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.083 |

| Impulsivity → Social support | −0.109 | 0.001 | −0.093 | −0.024 |

| Impulsivity → Cognitive restructuring | −0.067 | 0.042 | −0.064 | −0.001 |

| Impulsivity → Social withdrawal | 0.131 | <0.001 | 0.030 | 0.086 |

| Impulsivity → Problem avoidance | 0.099 | 0.003 | 0.015 | 0.071 |

| Emotional regulation → Eating disorders | 0.535 | <0.001 | 1.405 | 1.719 |

| Problem-solving → Eating disorders | −0.048 | 0.075 | −1.258 | 0.06 |

| Self-criticism → Eating disorders | 0.111 | <0.001 | 0.636 | 1.741 |

| Emotional expression → Eating disorders | −0.043 | 0.100 | −1.116 | 0.098 |

| Wishful thinking → Eating disorders | 0.080 | 0.001 | 0.333 | 1.376 |

| Social support → Eating disorders | −0.070 | 0.011 | −1.347 | −0.173 |

| Cognitive restructuring → Eating disorders | −0.024 | 0.419 | −0.964 | 0.401 |

| Social withdrawal → Eating disorders | 0.104 | <0.001 | 0.656 | 2.112 |

| Problem avoidance → Eating disorders | −0.010 | 0.686 | −0.814 | 0.536 |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Emotion regulation | 0.215 | 1.036 | 1.499 | |

| Problem-solving | 0.008 | −0.005 | 0.107 | |

| Self-criticism | 0.019 | 0.048 | 0.185 | |

| Emotional expression | 0.003 | −0.003 | 0.053 | |

| Wishful thinking | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.089 | |

| Social support | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.095 | |

| Cognitive restructuring | 0.002 | −0.013 | 0.043 | |

| Social withdrawal | 0.014 | 0.025 | 0.152 | |

| Problem avoidance | −0.001 | −0.039 | 0.025 | |

| Total effects (Impulsivity → mediating variables → Eating disorders) | 0.349 | 0.001 | 1.691 | 2.400 |

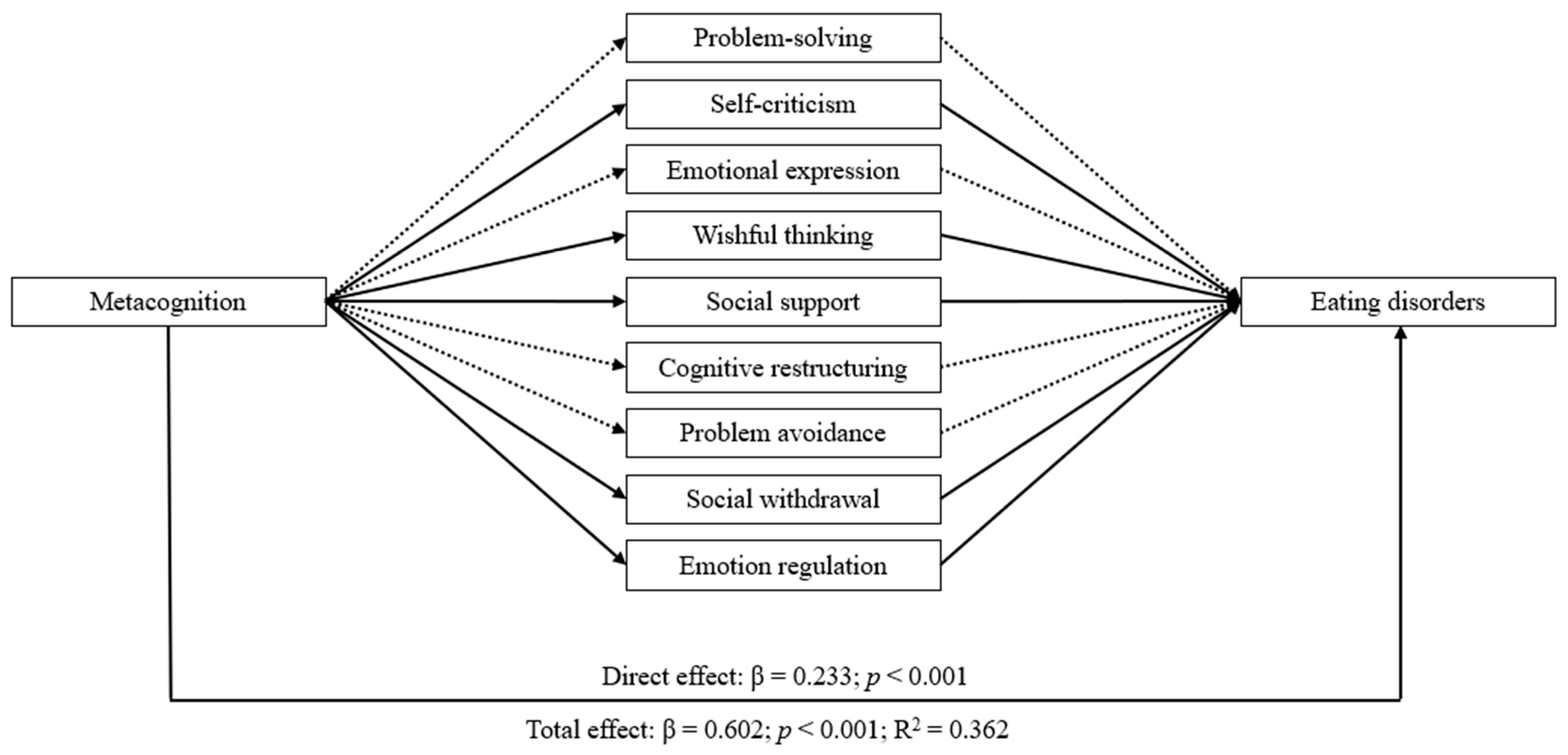

| β | p-Value | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||

| Impulsivity → Eating disorders | 0.233 | <0.001 | 1.606 | 2.539 |

| Metacognition → Emotion regulation | 0.596 | <0.001 | 1.679 | 1.996 |

| Metacognition → Problem-solving | −0.181 | <0.001 | −0.175 | −0.085 |

| Metacognition → Self-criticism | 0.410 | <0.001 | 0.292 | 0.389 |

| Metacognition → Emotion expression | 0.015 | 0.656 | −0.037 | 0.059 |

| Metacognition → Wishful thinking | 0.287 | <0.001 | 0.188 | 0.291 |

| Metacognition → Social support | −0.179 | <0.001 | −0.195 | −0.093 |

| Metacognition → Cognitive restructuring | −0.134 | <0.001 | −0.147 | −0.052 |

| Metacognition → Social withdrawal | 0.339 | <0.001 | 0.187 | 0.268 |

| Metacognition → Problem avoidance | 0.019 | 0.565 | −0.030 | 0.055 |

| Emotional regulation → Eating disorders | 0.453 | <0.001 | 1.149 | 1.464 |

| Problem-solving → Eating disorders | −0.038 | 0.149 | −1.099 | 0.167 |

| Self-criticism → Eating disorders | 0.084 | 0.001 | 0.365 | 1.435 |

| Emotional expression → Eating disorders | −0.072 | 0.005 | −1.44 | −0.264 |

| Wishful thinking → Eating disorders | 0.066 | 0.006 | 0.2 | 1.206 |

| Social support → Eating disorders | −0.057 | 0.03 | −1.196 | −0.062 |

| Cognitive restructuring → Eating disorders | −0.036 | 0.198 | −1.086 | 0.225 |

| Social withdrawal → Eating disorders | 0.071 | 0.009 | 0.238 | 1.632 |

| Problem avoidance → Eating disorders | 0.009 | 0.715 | −0.527 | 0.767 |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Emotion regulation | 0.27 | 2.01 | 2.799 | |

| Problem-solving | 0.007 | −0.027 | 0.155 | |

| Self-criticism | 0.035 | 0.117 | 0.515 | |

| Emotional expression | −0.001 | −0.059 | 0.037 | |

| Wishful thinking | 0.019 | 0.052 | 0.295 | |

| Social support | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.187 | |

| Cognitive restructuring | 0.005 | −0.024 | 0.123 | |

| Social withdrawal | 0.024 | 0.032 | 0.4 | |

| Problem avoidance | 0 | −0.016 | 0.022 | |

| Total effects (Metacognition → mediating variables → Eating disorders) | 0.602 | <0.001 | 4.892 | 5.801 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estévez, A.; Momeñe, J.; Macía, L.; Iruarrizaga, I.; Olave, L.; Aonso-Diego, G. The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies and Emotion Regulation in the Relationship between Impulsivity, Metacognition, and Eating Disorders. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121884

Estévez A, Momeñe J, Macía L, Iruarrizaga I, Olave L, Aonso-Diego G. The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies and Emotion Regulation in the Relationship between Impulsivity, Metacognition, and Eating Disorders. Nutrients. 2024; 16(12):1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121884

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstévez, Ana, Janire Momeñe, Laura Macía, Iciar Iruarrizaga, Leticia Olave, and Gema Aonso-Diego. 2024. "The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies and Emotion Regulation in the Relationship between Impulsivity, Metacognition, and Eating Disorders" Nutrients 16, no. 12: 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121884

APA StyleEstévez, A., Momeñe, J., Macía, L., Iruarrizaga, I., Olave, L., & Aonso-Diego, G. (2024). The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies and Emotion Regulation in the Relationship between Impulsivity, Metacognition, and Eating Disorders. Nutrients, 16(12), 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121884