Continued Breastfeeding in a Birth Cohort in the Western Amazon of Brazil: Risk of Interruption and Associated Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

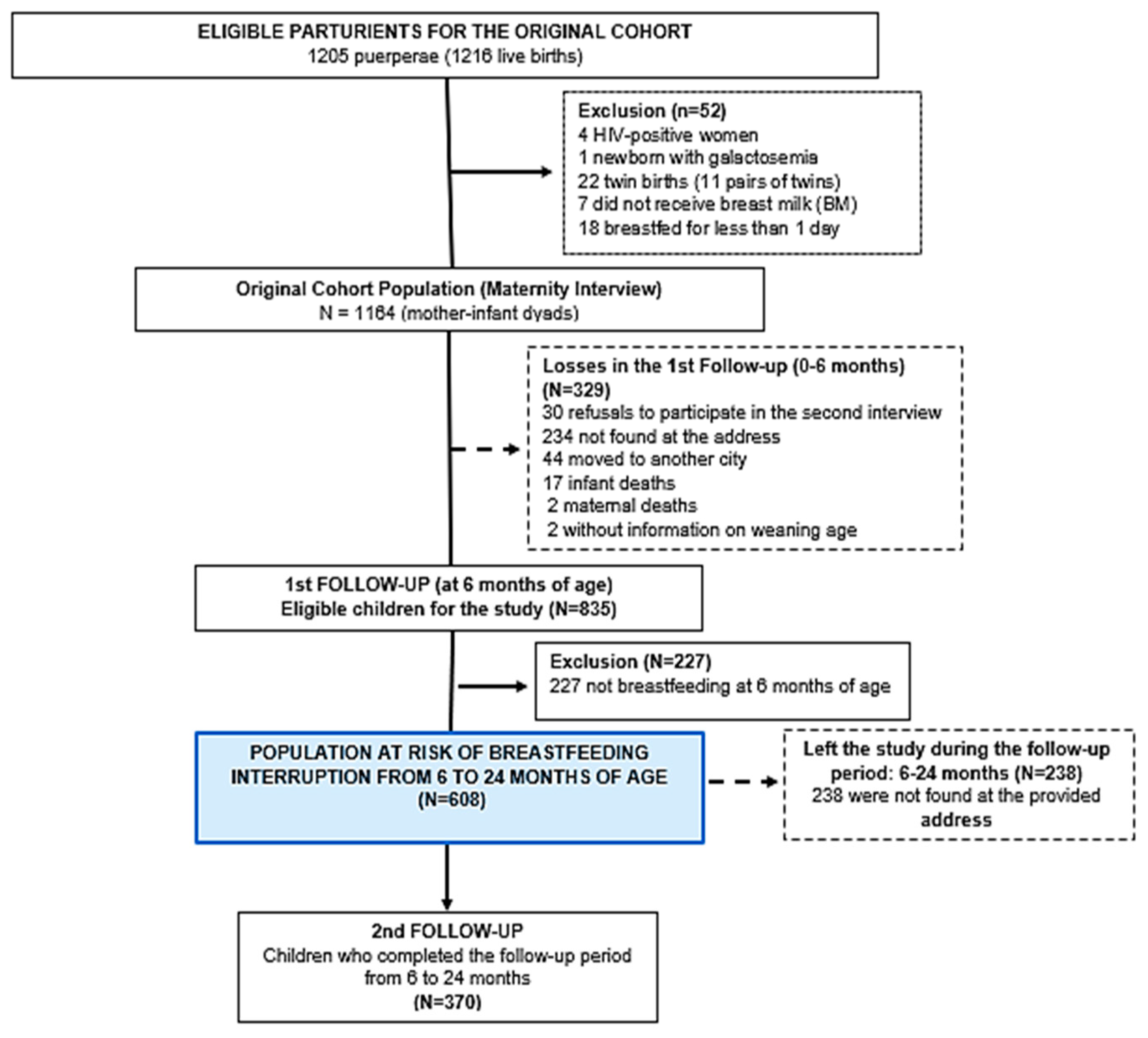

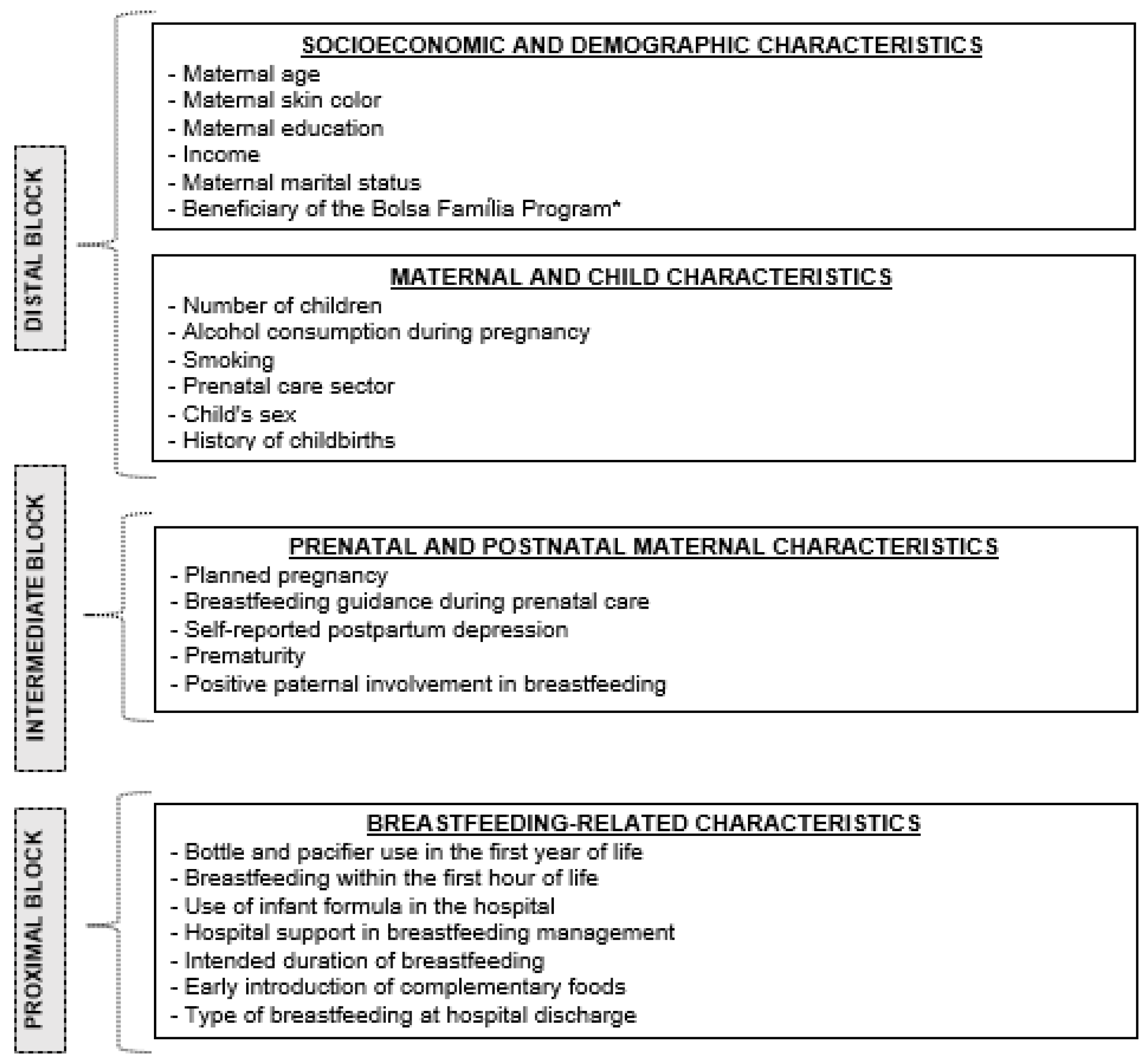

2. Materials and Methods

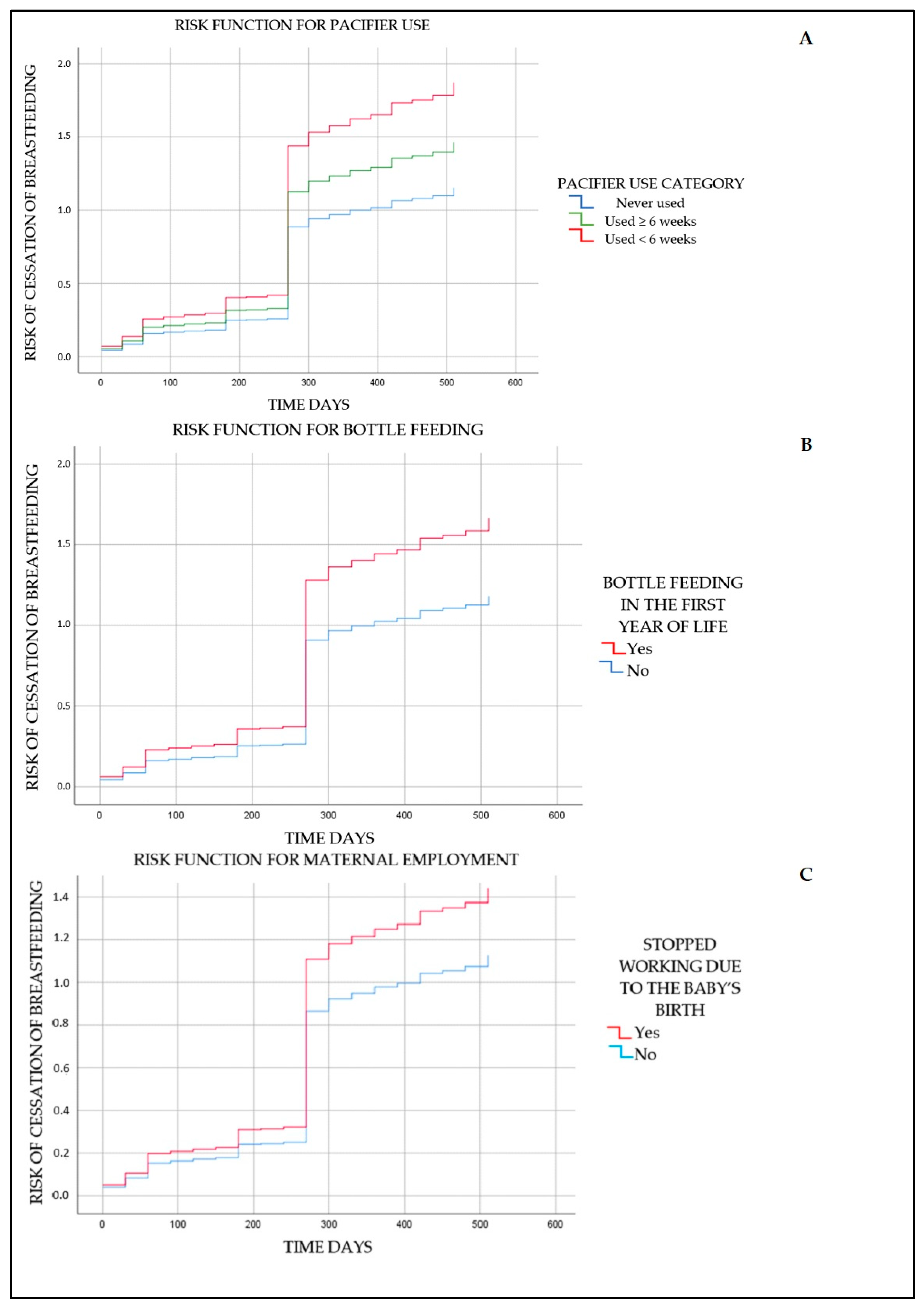

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Included in the Analysis | ||

| No | Yes | p-Value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Maternal age (years) | |||

| ≤19 | 49 (8.1) | 73 (12) | |

| 20–34 | 160 (26.3) | 239 (39.3) | |

| ≥35 | 29 (4.8) | 58 (9.5) | 0.487 |

| Skin color | |||

| White | 23 (3.8) | 31 (5.0) | |

| Brown | 191 (31.4) | 323 (53.1) | |

| Others | 24 (3.9) | 16 (2.6) | 0.015 |

| Maternal education | |||

| Up to 8 years | 72 (11.8) | 87 (14.4) | |

| 8 years or more | 166 (27.3) | 283 (46.5) | 0.065 |

| Marital status | |||

| Without partner | 32 (5.3) | 56 (9.2) | |

| With partner | 205 (33.8) | 314 (51.7) | 0.577 |

| Income level 1 | |||

| ≤1 MW | 51 (9.2) | 66 (11.9) | |

| 1 to 3 MW | 126 (22.7) | 187 (33.8) | |

| >3 MW | 43 (7.8) | 81 (14.6) | 0.352 |

| Bolsa Família Program | |||

| Yes | 61 (10) | 92 (15.2) | |

| No | 177 (29.2) | 277 (45.6) | 0.847 |

| Socioeconomic class | |||

| A and B | 42 (7.0) | 80 (13.3) | |

| C, D and E | 195 (32.3) | 286 (47.4) | 0.217 |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 17 (2.8) | 28 (4.6) | |

| No | 218 (36.1) | 341 (56.5) | 0.872 |

| Alcohol | |||

| Yes | 46 (7.6) | 49 (8.1) | |

| No | 192 (31.6) | 321 (52.7) | 0.044 |

| Bottle feeding in the first year of life | |||

| Yes | 50 (8.3) | 81 (13.5) | |

| No | 184 (30.5) | 287 (47.7) | 0.468 |

| Use of a pacifier before 6 weeks old | |||

| Never used | 175 (73.8) | 267 (72.4) | |

| Used ≥6 weeks | 40 (16.9) | 64 (17.3) | |

| Used <6 weeks | 22 (9.3) | 38 (10.3) | 0.899 |

| 1 MW: minimum wage. | |||

Appendix B

| Variables | HR | 95%CI | p-Value |

| Maternal age (years) | 0.668 | ||

| ≤19 | 1.16 | 0.83–1.61 | |

| 20–34 | 1.07 | 0.81–1.43 | |

| ≥35 | 1 | - | |

| Skin color | 0.410 | ||

| White | 0.79 | 0.55–1.13 | |

| Brown | 1 | - | |

| Others | 0.75 | 0.47–1.20 | |

| Maternal education | 0.709 | ||

| Up to 8 years | 1.04 | 0.84–1.29 | |

| 8 years or more | 1 | - | |

| Marital status | 0.950 | ||

| Without partner | 1 | - | |

| With partner | 1.00 | 0.78–1.29 | |

| Income level 1 | 0.497 | ||

| ≤1 MW | 0.86 | 0.64–1.16 | |

| 1 to 3 MW | 0.87 | 0.68–1.10 | |

| >3 MW | 1 | - | |

| Bolsa Família program | 0.623 | ||

| Yes | 1 | - | |

| No | 1.05 | 0.84–1.31 | |

| Socioeconomic class | 0.271 | ||

| A and B | 1 | - | |

| C, D and E | 1.14 | 0.90–1.43 | |

| Smoking | 0.624 | ||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.62–1.32 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Alcohol | 0.015 * | ||

| Yes | 1.35 | 1.06–1.73 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Prenatal care (visits) | 0.459 | ||

| <6 | 0.92 | 0.73–1.14 | |

| ≥6 | 1 | - | |

| Prenatal care sector | 0.058 * | ||

| Public | 1 | - | |

| Private | 1.28 | 0.99–1.67 | |

| Planned pregnancy | 0.238 | ||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 1.12 | 0.92–1.36 | |

| Prenatal breastfeeding guidance | 0.245 | ||

| Yes | 1 | - | |

| No | 1.13 | 0.91–1.40 | |

| Birth history | 0.916 | ||

| Primiparous | 0.99 | 0.81–1.20 | |

| Multiparous | 1 | - | |

| Number of children | 0.770 | ||

| 1 | 1 | - | |

| 2–3 | 1.05 | 0.84–1.32 | |

| ≥4 | 0.96 | 0.76–1.21 | |

| Received formula in the maternity ward | 0.619 | ||

| Yes | 0.92 | 0,69–1.24 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Breastfeeding support in the maternity ward | 0.084 * | ||

| Yes | 1 | - | |

| No | 1.19 | 0.97–1.47 | |

| Self-reported postpartum depression | 0.243 | ||

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.67–1.10 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Breastfeeding at hospital discharge 2 | 0.657 | ||

| EBF | 1 | - | |

| EBFme | 0.88 | 0.64–1.21 | |

| MBF | 0.85 | 0.50–1.45 | |

| Stopped working due to the baby’s birth | 0.074 * | ||

| Yes | 1 | - | |

| No | 0.706 | 0.48–1.03 | |

| Mother’s desire for breastfeeding duration | 0.644 | ||

| <6 months | 1.04 | 0.86–1.26 | |

| ≥6 months | 1 | - | |

| Baby’s sex | 0.796 | ||

| Female | 1 | - | |

| Male | 0.95 | 0.67–1.35 | |

| Positive paternal involvement in breastfeeding | 0.419 | ||

| Yes | 1 | - | |

| No | 0.89 | 0.68–1.17 | |

| Prematurity | 0.303 | ||

| Yes | 0.82 | 0.57–1.18 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Childcare follow-up | 0.606 | ||

| ≤7 days | 1 | - | |

| >7 days | 0.94 | 0.74–1.18 | |

| Breastfeeding in the first hour of life | 0.361 | ||

| Yes | 1 | - | |

| No | 1.09 | 0.90–1.32 | |

| Cross-nursing | 0.888 | ||

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.79–1.29 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Complementary feeding before 6 months | 0.319 | ||

| Yes | 1.11 | 0.89–1.39 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Bottle feeding in the first year of life | 0.003 * | ||

| Yes | 1.40 | 1.12–1.74 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Use of a pacifier before 6 weeks old | 0.000 * | ||

| Never used | 1 | ||

| Used ≥6 weeks | 1.32 | 0.97–1.79 | |

| Used <6 week | 1.67 | 1.32–2.12 | |

| * p-value < 0.20. 1 MW: minimum wage; 2 EBF: exclusive breastfeeding; EBFme: exclusive breastfeeding with early formula use; MBF: mixed breastfeeding. | |||

References

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Chu, Y.; Perin, J.; Zhu, J.; Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Mathers, C.; Black, R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–2015: An updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2016, 388, 3027–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil. Infant Mortality in Brazil [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/edicoes/2021/boletim_epidemiologico_svs_37_v2.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Brazil. Primary care notebooks: Child health, breastfeeding, and complementary feeding. Rev. Enferm. UFPE Line 2015, 12, 280. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Giugliani, E.R.; Horta, B.L.; de Mola, C.L.; Lisboa, B.O.; Victora, C.G. Effect of breastfeeding promotion interventions on child growth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Pediatr. 2015, 104, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; França, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C.; et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st Century: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Lifelong Effects. Epidemiol. Health Serv. 2016, 25, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, B.L.; de Mola, C.L.; Victora, C.G. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Pediatr. 2015, 104, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, A.M. Breastfeeding in the modern world. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 78 (Suppl. S2), 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, M.J.; Sinha, B.; Chowdhury, R.; Bhandari, N.; Taneja, S.; Martines, J.; Bahl, R. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Pediatr. 2015, 104, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passanha, A.; Cervato-Mancuso, A.M.; Pinto e Silva, M.E.M. Protective elements of breast milk in the prevention of gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases. J. Hum. Growth Dev. 2010, 20, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zong, X.; Wu, H.; Zhao, M.; Magnussen, C.G.; Xi, B. Global prevalence of WHO infant feeding practices in 57 LMICs in 2010–2018 and time trends since 2000 for 44 LMICs. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 37, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccolini, C.S.; Boccolini, P.d.M.M.; Monteiro, F.R.; Venâncio, S.I.; Giugliani, E.R.J. Breastfeeding indicators trends in Brazil for three decades. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Breastfeeding: Prevalence and Practices among Brazilian Children under 2 Years. ENANI-2019 [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://enani.nutricao.ufrj.br/index.php/relatorios/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Tang, L.; Lee, A.H.; Binns, C.W. Factors associated with breastfeeding duration: A prospective cohort study in Sichuan Province, China. World J. Pediatr. 2015, 11, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susiloretni, K.A.; Hadi, H.; Blakstad, M.M.; Smith, E.R.; Shankar, A.H. Does exclusive breastfeeding relate to longer duration of breastfeeding? A prospective cohort study. Midwifery 2019, 69, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, V.B.d.S.; Abuchaim, É.d.S.V.; Maia, R.d.R.P.; Coca, K.P.; Marcacine, K.O.; Abrão, A.C.F.d.V. Breastfeeding in children under two years in a city in the Amazon region. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2022, 35, eAPE02487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinzani, S.S.; Capovilla, V.M. The identity of Acrean culinary culture. Contextos da Alimentação. J. Behav. Cult. Soc. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, F.A.; Ramalho, A.A.; Andrade AM de Opitz, S.P.; Koifman, R.J.; da Silva, I.F. Breastfeeding patterns and factors associated with early weaning in Western Amazon. Rev. Saude Publica 2021, 55, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, A.A.; Martins, F.A.; Lima, T.A.d.S.; Andrade, A.M.; Koifman, R.J. Factors associated with breastfeeding in the first hour of life in Rio Branco, Acre. Demetra 2019, 14, e43809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.S.; Matijasevich, A.; Tavares, B.F.; Barros, A.J.D.; Botelho, I.P.; Lapolli, C.; Magalhães, P.V.d.S.; Barbosa, A.P.P.N.; Barros, F.C. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in a sample of mothers from the 2004 Pelotas Birth Cohort Study. Cad Saúde Pública 2007, 23, 2577–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccolini, C.S.; Carvalho, M.L.D.; Oliveira, M.I.C.D. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life in Brazil: A systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 2015, 49, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Ahwong, E.; Devenish, G.; Ha, D.; Do, L. Determinants of continued breastfeeding at 12 and 24 months: Results of an Australian cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.B.; Palma, D.; Domene, S.M.A.; Taddei, J.A.A.C.; Lopez, F.A. Risk factors associated with early weaning and weaning period in infants enrolled in day care centers. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2009, 27, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vieira, G.O.; de Oliveira Vieira, T.; da Cruz Martins, C.; de Santana Xavier Ramos, M.; Giugliani, E.R.J. Risk factors for and protective factors against breastfeeding interruption before 2 years: A birth cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasetyo, Y.B.; Rahayu, H.T.; Kurnia, A.D.; Masruroh, N.L.; Melizza, N.; Latif, R.A. Breastfeeding trends and its related factors in Indonesia: A national survey. J. Gizi Pangan 2023, 18, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, J.L.D.; Jordão, R.E.; de Azevedo Barros Filho, A. Factors associated with median duration of breastfeeding in infants born in a municipality of São Paulo State. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 22, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.R.; Buccini, G.S.; Venâncio, S.I.; Costa, T.H. Influence of maternity leave on exclusive breastfeeding. J. Pediatr. 2017, 93, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muelbert, M.; Giugliani, E.R.J. Factors associated with the maintenance of breastfeeding for 6, 12, and 24 months in adolescent mothers. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, E.; Yalçın, S.S.; Özdemir-Geyik, P.; Karaağaoğlu, E. Effect of pacifier use on exclusive and any breastfeeding: A meta-analysis. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2009, 51, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, M.S.; Schorn, M.; Santo, L.C.d.E.; Oliveira, L.D.; Giugliani, E.R.J. Factors associated with continued breastfeeding for 12 months or more in working women of a general hospital. Cien Saude Colet 2021, 26, 5851–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, T.F.S.; Rauber, L.N.; de Freitas Melhem Vieira, D.G.; da Silva, C.C.; Saldan, P.C. Factors associated with breastfeeding in children aged 6 to 23 months. ABCS Health Sci. 2020, 45, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Su, M.; Xu, Y. Factors affecting the breastfeeding duration of infants and young children in China: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimes, K.A.; Oliveira, M.I.C.D.; Boccolini, C.S. Maternity leave and exclusive breastfeeding. Rev. Saude Publica 2019, 53, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, G.P.; Britto, A.M.A.; Leite, C.C.D.P.; Marin, L.G. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in a maternity hospital reference in humanized birth. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2021, 43, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçin, S.S.; Erat Nergiz, M.; Elci, Ö.C.; Zikusooka, M.; Yalçin, S.; Sucakli, M.B.; Keklik, K. Breastfeeding practices among Syrian refugees in Turkey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni, M.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Manfra, P.; Sorrentino, M.; Bezze, G.; Plevani, L.; Cavallaro, G.; Raffaeli, G.; Crippa, B.L.; Colombo, L.; et al. Breastfeeding difficulties and risk for early breastfeeding cessation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarath, U.; Dibley, M.J.; Agho, K.E. Breastfeeding practices and associated factors among children under 24 months of age in Timor-Leste. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, G.S.; Giugliani, E.R.J.; Vieira, T.d.O.; Vieira, G.O. Factors associated with breastfeeding maintenance for 12 months or more: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. 2018, 94, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Kotze, C.; Feeley, A.; Doherty, T.; Faber, M. Maternity protection entitlements for non-standard workers in low-and-middle-income countries and potential implications for breastfeeding practices: A scoping review of research since 2000. Int. Breastfeed J. 2023, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongprasert, K.; Siviroj, P. Factors associated with the maintenance of breastfeeding at one year among women in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y. Shift-work and breastfeeding for women returning to work in a manufacturing workplace in Taiwan. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramashanti, B.A.; Dibley, M.J.; Huda, T.M.; Prabandari, Y.S.; Alam, N.A. Factors influencing breastfeeding continuation and formula feeding beyond six months in rural and urban households in Indonesia: A qualitative investigation. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2023, 18, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.D.B.; Magalhães, E.I.D.S.; Rocha, D.D.S. Prevalence and determinants of complementary feeding indicators in the first year of life in Southwest Bahia. Rev. Bras. Saude Mater. Infant. 2023, 23, e20230172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortelan, N.; Neri, D.A.; Benicio, M.H.D. Feeding practices of low birth weight Brazilian infants and associated factors. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schincaglia, R.M.; de Oliveira, A.C.; de Sousa, L.M.; Martins, K.A. Dietary practices and factors associated with early introduction of complementary feeding among children under six months in the northwest region of Goiânia. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2015, 24, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.S.; Alexander, D.D.; Krebs, N.F.; Young, B.E.; Cabana, M.D.; Erdmann, P.; Hays, N.P.; Bezold, C.P.; Levin-Sparenberg, E.; Turini, M.; et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: A meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 190–196.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.A.A.L.; Caminha, M.F.C.; Silva, S.L.; Serva, V.M.S.B.D.; Azevedo, P.T.A.C.C.; Batista Filho, M. Maternal breastfeeding: Indicators and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in a subnormal urban cluster assisted by the Family Health Strategy. J. Pediatr. 2019, 95, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neifert, M.; Bunik, M. Overcoming clinical barriers to exclusive breastfeeding. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 60, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.J.; Giugliani, E.R.J. Which women breastfeed for 2 years or more? J. Pediatr. 2012, 88, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bráulio, T.I.C.; Damasceno, S.S.; Cruz, R.S.B.L.C.; Figueiredo, M.F.E.R.; Silva, J.M.F.L.; da Silva, V.M.; Gonçalves, G.A.A. Parental knowledge and attitudes about the importance of breastfeeding. Esc. Anna Nery 2021, 25, e20200473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.P.D.; Silveira, R.B.; Mascarenhas, M.L.W.; Silva, M.B.; Kaufmann, C.C.; Albernaz, E.P. Mothers’ perception of paternal support: Influence on the duration of breastfeeding. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2012, 30, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total 1 | 24 Month Follow-Up | Follow-Up Losses | X2—Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 608 (100%) | N = 370 (%) | N = 238 (%) | p-Values | |

| Age | 0.487 | |||

| ≤19 | 122 (20.1) * | 73 (59.8) | 49 (40.2) | |

| 20–34 | 399 (65.6) * | 239 (59.9) | 160 (40.1) | |

| ≥35 | 87 (14.3) * | 58 (66.7) | 29 (33.3) | |

| Skin color | 0.015 | |||

| White | 54 (8.9) * | 31 (57.4) | 23 (42.6) | |

| Brown | 514 (84.5) * | 323 (62.8) | 191 (37.2) | |

| Others | 40 (6.6) * | 16 (40.0) | 24 (60.0) | |

| Maternal education | 0.065 | |||

| Up to 8 years | 159 (26.2) * | 87 (54.7) | 72 (45.3) | |

| 8 years or more | 449 (73.8) * | 283 (63.0) | 166 (37.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.577 | |||

| Without partner | 88 (14.5) * | 56 (63.6) | 32 (36.4) | |

| With partner | 519 (85.5) * | 314 (60.5) | 205 (39.5) | |

| Income level 2 | 0.352 | |||

| ≤1 MW | 117 (21.1) * | 66 (56.4) | 51 (43.6) | |

| 1 to 3 MW | 313 (56.5) * | 187 (59.7) | 126 (40.3) | |

| >3 MW | 124 (22.4) * | 81 (65.3) | 43 (34.7) | |

| Bolsa Família Program | 0.847 | |||

| Yes | 153 (25.2) * | 92 (60.1) | 61 (39.9) | |

| No | 454 (74.7) * | 277 (61.0) | 177 (39.0) | |

| Socioeconomic class | 0.217 | |||

| A and B | 122 (20.2) * | 80 (65.6) | 42 (34.4) | |

| C, D and E | 481 (79.8) * | 286 (47.4) | 195 (40.5) | |

| Smoking | 0.872 | |||

| Yes | 45 (7.5) * | 28 (62.2) | 17 (37.8) | |

| No | 559 (92.5) * | 341 (61.0) | 218 (39.0) | |

| Alcohol | 0.044 | |||

| Yes | 95 (15.6) * | 49 (51.6) | 46 (48.4) | |

| No | 513 (84.4) * | 321 (62.6) | 192 (37.4) | |

| Prenatal care (visits) | 0.476 | |||

| <6 | 157 (15.6) * | 100 (63.7) | 57 (36.3) | |

| ≥6 | 435 (73.5) * | 263 (60.5) | 172 (39.5) | |

| Prenatal care sector | 0.403 | |||

| Public | 513 (86.1) * | 309 (60.2) | 204 (39.8) | |

| Private | 83 (13.9) * | 54 (65.1) | 29 (34.9) | |

| Planned pregnancy | 0.209 | |||

| Yes | 230 (38.0) * | 147 (63.9) | 83 (36.1) | |

| No | 376 (62.0) * | 221 (58.8) | 155 (41.2) | |

| Prenatal breastfeeding guidance | 0.252 | |||

| Yes | 287 (58.1) * | 181 (63.1) | 106 (36.9) | |

| No | 207 (41.9) * | 120 (58.0) | 87 (42.0) | |

| Birth history | 0.359 | |||

| Primiparous | 236 (38.8) * | 149 (63.1) | 87 (36.9) | |

| Multiparous | 372 (61.2) * | 221 (59.4) | 151 (40.6) | |

| Number of children | 0.490 | |||

| 1 | 236(38.8) * | 149 (63.1) | 87 (36.9) | |

| 2–3 | 183 (30.1) * | 98 (53.6) | 85 (46.4) | |

| ≥4 | 189 (31.1) * | 123 (65.1) | 66 (34.9) | |

| Received formula in the maternity ward | 0.319 | |||

| Yes | 76 (12.6) * | 50 (65.8) | 26 (34.2) | |

| No | 525 (87.4) * | 314 (59.8) | 211 (40.2) | |

| Breastfeeding support in the maternity ward | 0.389 | |||

| Yes | 441 (72.5) * | 273 (61.9) | 168 (38.1) | |

| No | 167 (27.5) * | 97 (58.1) | 70 (41.9) | |

| Self-reported postpartum depression | 0.624 | |||

| Yes | 114 (18.8) * | 67 (58.8) | 47 (41.2) | |

| No | 493 (81.2) * | 302 (61.3) | 191 (38.7) | |

| Breastfeeding at hospital discharge 3 | 0.592 | |||

| EBF | 522 (85.9) * | 314 (60.2) | 208 (39.8) | |

| EBFme | 66 (10.9) * | 44 (66.7) | 22 (33.3) | |

| MBF | 20 (3.2) * | 12 (60.0) | 8 (40.0) | |

| Stopped working due to the baby’s birth | 0.828 | |||

| Yes | 268 (47.9) * | 162 (60.4) | 106 (39.6) | |

| No | 246 (52.1) * | 151 (61.4) | 95 (38.6) | |

| Mother’s desire for breastfeeding duration | 0.349 | |||

| <6 months | 49 (8.2) * | 33 (67.3) | 16 (32.7) | |

| ≥6 months | 550 (91.8) * | 333 (60.5) | 217 (39.5) | |

| Baby’s sex | 0.913 | |||

| Female | 321 (52.8) * | 196 (61.1) | 125 (38.9) | |

| Male | 287 (47.2) * | 174 (60.6) | 113 (39.4) | |

| Positive paternal involvement in breastfeeding | 0.147 | |||

| Yes | 509 (83.9) * | 303 (59.5) | 206 (40.5) | |

| No | 98 (16.1) * | 66 (67.3) | 32 (32.7) | |

| Prematurity | 0.800 | |||

| Yes | 51 (8.4) * | 32 (62.7) | 19 (37.3) | |

| No | 553 (91.6) * | 337 (60.9) | 216 (39.1) | |

| Childcare follow-up | 0.969 | |||

| ≤7 days | 131 (23.3) * | 80 (61.1) | 51 (38.9) | |

| >7 days | 432 (76.7) * | 263 (60.9) | 169 (39.1) | |

| Breastfeeding in the first hour of life | 0.735 | |||

| Yes | 359 (60.4) * | 215 (59.9) | 144 (40.1) | |

| No | 235 (39.6) * | 144 (61.3) | 91 (38.7) | |

| Cross-nursing | 0.674 | |||

| Yes | 115 (18.9) * | 68 (59.1) | 47 (40.9) | |

| No | 493 (81.1) * | 302 (61.3) | 191 (38.7) | |

| Complementary feeding before 6 months | 0.291 | |||

| Yes | 456 (75.0) * | 272 (59.6) | 184 (40.4) | |

| No | 152(25.0) * | 98 (64.5) | 54 (35.5) | |

| Bottle feeding in the first year of life | 0.852 | |||

| Yes | 131 (21.8) * | 81 (61.8) | 50 (38.2) | |

| No | 471 (78.2) * | 287 (60.9) | 184 (39.1) | |

| Use of a pacifier before 6 weeks old | 0.899 | |||

| Never used | 442 (72.9) * | 267 (60.4) | 175 (39.6) | |

| Used ≥6 weeks | 60 (9.9) * | 38 (63.3) | 22 (36.7) | |

| Used <6 week | 104 (17.2) * | 64 (61.5) | 40 (38.3) |

| Variable | Median Time | Risk of Weaning from 6–24 Months | Wilcoxon–Gehan | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | 12 | 18 | 24 | p-Value | |

| Global | 19% | 65% | 71% | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.794 | ||||

| ≤19 | 295 | 18% | 28% | 75% | |

| 20–34 | 300 | 19% | 65% | 71% | |

| ≥35 | 315 | 21% | 60% | 66% | |

| Skin color | 0.377 | ||||

| White | 304 | 19% | 65% | 69% | |

| Brown | 302 | 18% | 64% | 70% | |

| Others | 270 | 22% | 78% | 82% | |

| Maternal education | 0.463 | ||||

| Up to 8 years | 293 | 21% | 67% | 72% | |

| 8 years or more | 304 | 18% | 64% | 71% | |

| Marital status | 0,477 | ||||

| Without partner | 302 | 17% | 65% | 72% | |

| With partner | 292 | 27% | 64% | 66% | |

| Income level 1 | 0.702 | ||||

| ≤1 MW | 299 | 21% | 65% | 68% | |

| 1 to 3 MW | 304 | 18% | 64% | 70% | |

| >3 MW | 296 | 18% | 68% | 67% | |

| Bolsa Família Program | 0.539 | ||||

| Yes | 299 | 18% | 63% | 70% | |

| No | 306 | 19% | 66% | 71% | |

| Socioeconomic class | 0.168 | ||||

| A and B | 288 | 26% | 66% | 74% | |

| C, D and E | 303 | 17% | 65% | 70% | |

| Smoking | 0.994 | ||||

| Yes | 305 | 22% | 62% | 64% | |

| No | 301 | 18% | 65% | 71% | |

| Alcohol | 0.004 | ||||

| Yes | 266 | 25% | 77% | 81% | |

| No | 308 | 18% | 63% | 69% | |

| Prenatal care (visits) | 0.444 | ||||

| <6 | 307 | 17% | 64% | 68% | |

| ≥6 | 300 | 19% | 65% | 72% | |

| Prenatal care sector | 0.080 | ||||

| Public | 304 | 18% | 65% | 69% | |

| Private | 277 | 27% | 70% | 81% | |

| Planned pregnancy | 0.070 | ||||

| Yes | 311 | 17% | 62% | 69% | |

| No | 294 | 20% | 67% | 73% | |

| Prenatal breastfeeding guidance | 0.171 | ||||

| Yes | 313 | 18% | 61% | 68% | |

| No | 289 | 20% | 70% | 73% | |

| Birth history | 0.480 | ||||

| Primiparous | 303 | 17% | 65% | 72% | |

| Multiparous | 299 | 20% | 65% | 70% | |

| Number of children | 0.698 | ||||

| 1 | 303 | 17% | 65% | 72% | |

| 2–3 | 292 | 19% | 69% | 74% | |

| ≥4 | 309 | 21% | 61% | 67% | |

| Received formula in the maternity ward | 0.669 | ||||

| Yes | 307 | 21% | 62% | 77% | |

| No | 299 | 18% | 64% | 72% | |

| Breastfeeding support in the maternity ward | 0.140 | ||||

| Yes | 306 | 18% | 63% | 68% | |

| No | 288 | 20% | 70% | 78% | |

| Self-reported postpartum depression | 0.372 | ||||

| Yes | 307 | 16% | 64% | 66% | |

| No | 299 | 19% | 66% | 72% | |

| Breastfeeding at hospital discharge 2 | 0.487 | ||||

| EBF | 298 | 19% | 66% | 72% | |

| EBFme | 318 | 20% | 59% | 65% | |

| MBF | 324 | 10% | 60% | 70% | |

| Stopped working due to the baby’s birth | 0.008 | ||||

| Yes | 285 | 23% | 69% | 75% | |

| No | 317 | 14% | 61% | 67% | |

| Mother’s desire for breastfeeding duration | 0.432 | ||||

| <6 months | 313 | 12% | 63% | 69% | |

| ≥6 months | 299 | 20% | 65% | 71% | |

| Baby’s sex | 0.429 | ||||

| Female | 296 | 20% | 67% | 71% | |

| Male | 307 | 18% | 63% | 70% | |

| Positive paternal involvement in breastfeeding | 0.500 | ||||

| Yes | 297 | 18% | 67% | 72% | |

| No | 322 | 22% | 52% | 64% | |

| Prematurity | 0.340 | ||||

| Yes | 323 | 16% | 59% | 63% | |

| No | 299 | 19% | 66% | 72% | |

| Childcare follow-up | 0.734 | ||||

| ≤7 days | 301 | 19% | 65% | 70% | |

| >7 days | 302 | 18% | 66% | 73% | |

| Breastfeeding in the first hour of life | 0.309 | ||||

| Yes | 304 | 16% | 365% | 70% | |

| No | 294 | 22% | 66% | 73% | |

| Cross-nursing | 0.805 | ||||

| Yes | 306 | 16% | 64% | 70% | |

| No | 299 | 18% | 65% | 71% | |

| Complementary feeding before 6 months | 0.248 | ||||

| Yes | 296 | 20% | 66% | 72% | |

| No | 315 | 16% | 61% | 68% | |

| Bottle feeding in the first year of life | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 265 | 28% | 74% | 81% | |

| No | 311 | 16% | 62% | 68% | |

| Use of a pacifier before 6 weeks old | 0.000 | ||||

| Never used | 316 | 11% | 61% | 67% | |

| Used <6 weeks | 247 | 32% | 81% | 86% | |

| Used ≥6 weeks | 289 | 22% | 68% | 78% | |

| Variable | Proximal Model | Intermediate Model 2 | Distal Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95CI% | HR | 95CI% | HR | 95CI% | |

| Maternal age (years) 1 | 0.99 | (0.97–1.00) | 0.98 | (0.97–1.00) | 0.98 | (0.97–1.00) |

| Baby’s sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Femal | 1.07 | (0.88–1.29) | 1.09 | (0.88–1.34) | 1.12 | (0.91–1.38) |

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Yes | 1.32 | (1.03–1.69) | 1.33 | (1.01–1.75) | 1.27 | (0.96–1.68) |

| No | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Prenatal care sector | ||||||

| Public | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| Private | 1.34 | (1.02–1.75) | 1.19 | (0.89–1.60) | 1.07 | (0.79–1.44) |

| Stopped working due to the baby’s birth | ||||||

| Yes | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| No | - | - | 0.80 | (0.64–0.99) | 0.78 | (0.62–0.97) |

| Use of a pacifier before 6 weeks old | ||||||

| Never used | - | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| Used ≥6 weeks | - | - | - | - | 1.27 | (0.90–1.78) |

| Used <6 weeks | 1.62 | (1.24–2.11) | ||||

| Bottle feeding in the first year of life | ||||||

| Yes | - | - | - | - | 1.41 | (1.11–1.78) |

| No | - | - | - | - | 1 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pastro, D.d.O.T.; Martins, F.A.; Ramalho, A.A.; Andrade, A.M.d.; Opitz, S.P.; Koifman, R.J.; Silva, I.F.d. Continued Breastfeeding in a Birth Cohort in the Western Amazon of Brazil: Risk of Interruption and Associated Factors. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193408

Pastro DdOT, Martins FA, Ramalho AA, Andrade AMd, Opitz SP, Koifman RJ, Silva IFd. Continued Breastfeeding in a Birth Cohort in the Western Amazon of Brazil: Risk of Interruption and Associated Factors. Nutrients. 2024; 16(19):3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193408

Chicago/Turabian StylePastro, Déborah de Oliveira Togneri, Fernanda Andrade Martins, Alanderson Alves Ramalho, Andreia Moreira de Andrade, Simone Perufo Opitz, Rosalina Jorge Koifman, and Ilce Ferreira da Silva. 2024. "Continued Breastfeeding in a Birth Cohort in the Western Amazon of Brazil: Risk of Interruption and Associated Factors" Nutrients 16, no. 19: 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193408

APA StylePastro, D. d. O. T., Martins, F. A., Ramalho, A. A., Andrade, A. M. d., Opitz, S. P., Koifman, R. J., & Silva, I. F. d. (2024). Continued Breastfeeding in a Birth Cohort in the Western Amazon of Brazil: Risk of Interruption and Associated Factors. Nutrients, 16(19), 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193408