Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics in Managing Insulin Resistance and Hormonal Imbalance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

- PubMed;

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

- Scopus;

- Web of Science;

- Embase.

2.3. Search Algorithm

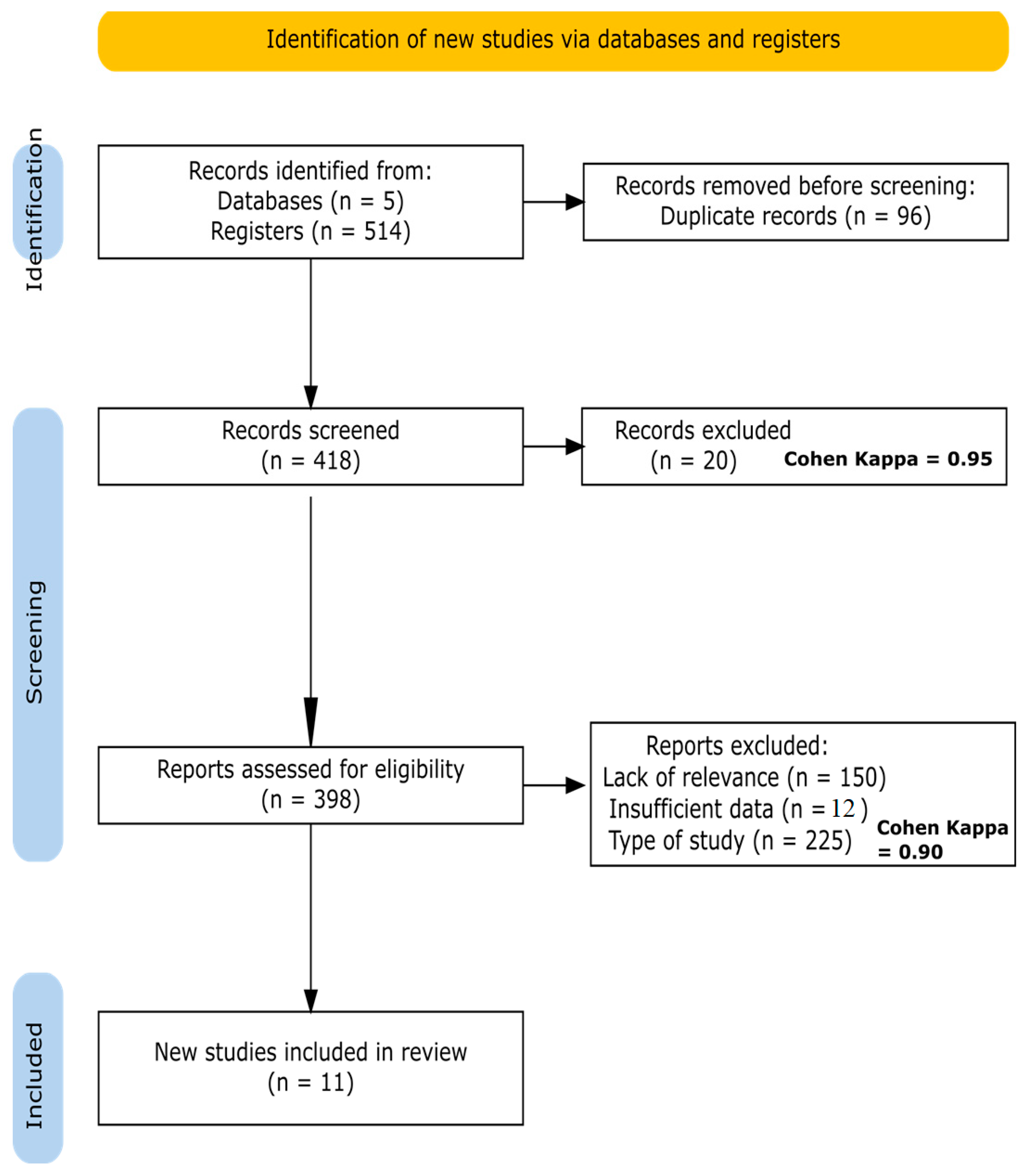

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

- Study characteristics: first author, publication year, country, and study design.

- Participant characteristics: number of participants, age, BMI, sex (all female participants), and diagnostic criteria for PCOS.

- Intervention details: type of probiotic/prebiotic/synbiotic used, bacterial strains, dosage, form of administration, and duration of intervention.

- Comparator: details of the control group (placebo or standard care).

- Outcomes measured: primary outcomes (e.g., insulin resistance markers, hormonal parameters), secondary outcomes (e.g., lipid profile, inflammatory markers), and methods of measurement.

- Results: main findings, statistical significance, and conclusions drawn by the authors.

- Limitations: as reported by the authors.

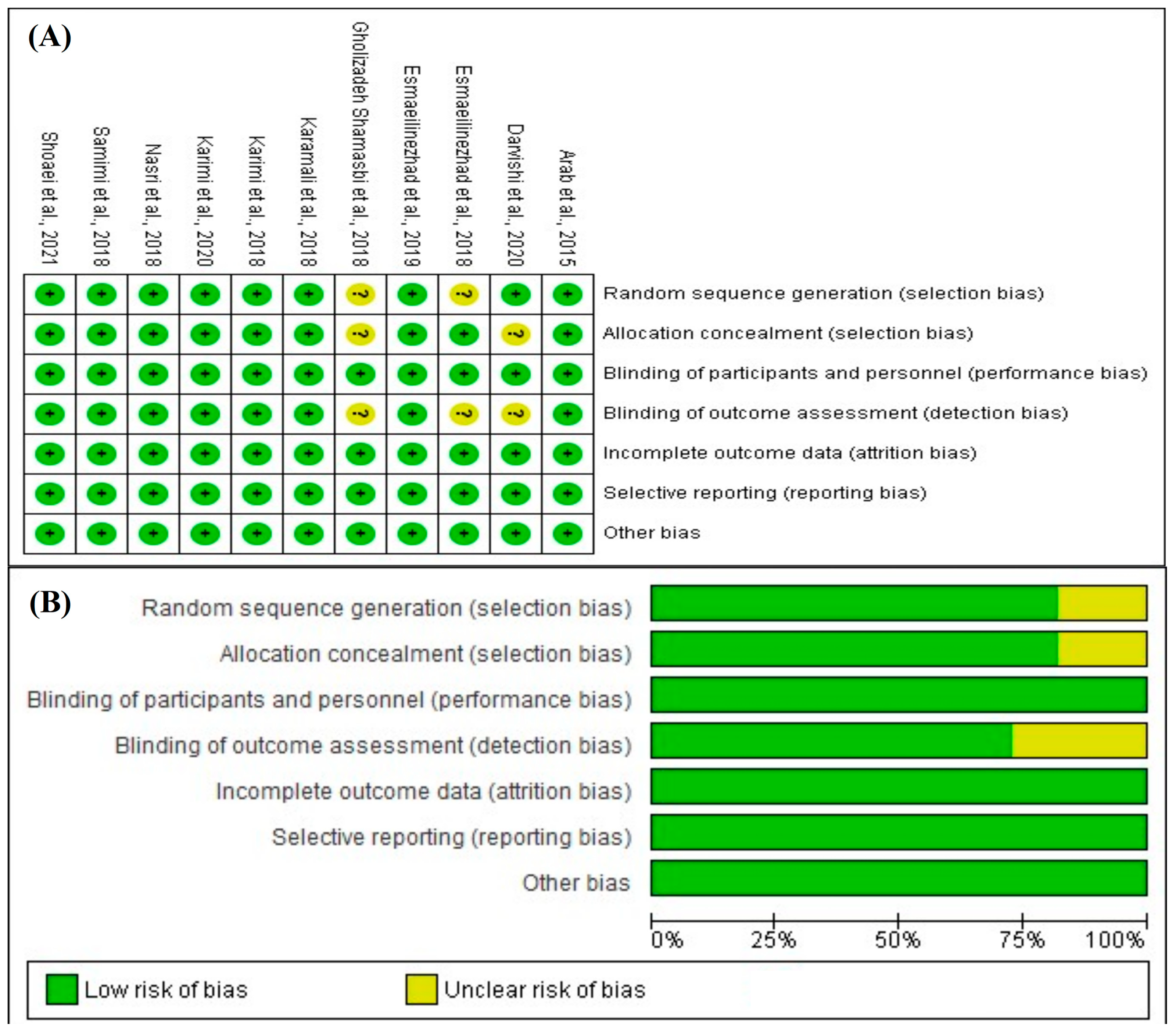

2.6. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

- Random sequence generation (selection bias);

- Allocation concealment (selection bias);

- Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

- Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

- Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

- Selective reporting (reporting bias).

2.7. Data Synthesis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

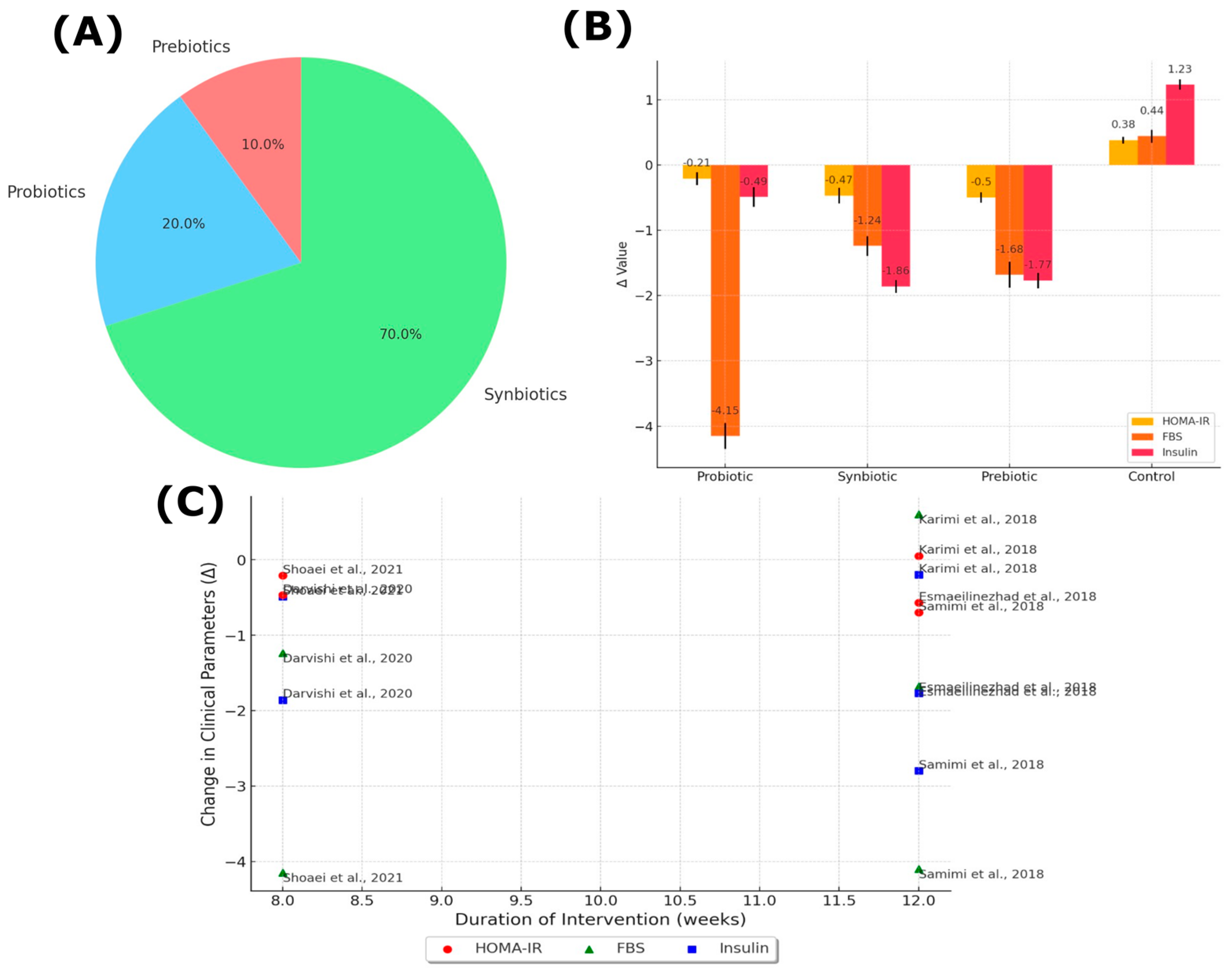

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Overview of Study Results

3.3. Participant Characteristics

3.4. Intervention Details and Comparison Groups

3.5. Risk-of-Bias Assessment Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.3. Impact of Probiotics on Insulin Resistance and Hormonal Balance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

4.4. Limitations of the Included Studies

4.5. Limitations of the Review

4.6. Clinical Implications

- Selection of specific strains: different probiotic strains can have varied effects on metabolic and hormonal parameters. Choosing strains with demonstrated efficacy could enhance treatment outcomes.

- Dosage and formulation: adjusting the dosage and choosing the appropriate formulation (capsules, powders, functional foods) according to patient preferences and tolerance can improve adherence and effectiveness.

- Comprehensive evaluation: assessing the patient’s overall health status, including metabolic markers, hormonal levels, and lifestyle factors, can help develop a tailored supplementation plan.

- Quality and standardization: selecting high-quality products from reputable manufacturers is crucial, as efficacy depends on the viability and concentration of the strains used.

- Regulation: dietary supplements are not always subject to the same regulatory standards as medications. Clinicians should guide patients toward products proven in safety and efficacy.

- Patient education: informing patients about the importance of adherence, possible side effects, and realistic expectations will enhance satisfaction and compliance with the supplementation regimen.

4.7. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Chen, Z.; Dunaif, A.; Laven, J.S.E.; Legro, R.S.; Lizneva, D.; Natterson-Horowtiz, B.; Teede, H.J.; Yıldız, B.O. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2016, 2, 16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Nankali, A.; Ghanbari, A.; Jafarpour, S.; Ghasemi, H.; Dokaneheifard, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Women Worldwide: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azziz, R. Controversy in Clinical Endocrinology: Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: The Rotterdam Criteria Are Premature. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.J.E.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; Boyle, J.A.; et al. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 2447–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joham, A.E.; Norman, R.J.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Legro, R.S.; Franks, S.; Moran, L.J.; Boyle, J.; Teede, H.J. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Wang, L.; Bai, E. Metabolic Characteristics of Different Phenotypes in Reproductive-Aged Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1370578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krentowska, A.; Kowalska, I. Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components in Different Phenotypes of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2022, 38, e3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghetti, P.; Tosi, F.; Bonin, C.; Di Sarra, D.; Fiers, T.; Kaufman, J.-M.; Giagulli, V.A.; Signori, C.; Zambotti, F.; Dall’Alda, M.; et al. Divergences in Insulin Resistance Between the Different Phenotypes of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E628–E637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidi, A.; Azami, M.; Tardeh, S.; Tardeh, Z. The Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 2747–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, M.B.P.; Demayo, S.; Giannone, L.; Nolting, M.; D’isa, E.; Servetti, V.; Rolo, G.; Gutierrez, G.; Jarlip, M. Metabolic Compromise in Women with PCOS: Earlier than Expected. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2020, 66, 1225–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinnat ara nasreen, S.; Shahreen, S.; Huq, S.; Rahman, S. Polycystic ovary syndrome with metabolic syndrome. J. Med. Case Rep. Rev. 2021, 4, 921–929. [Google Scholar]

- DeUgarte, C.M.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Azziz, R. Prevalence of Insulin Resistance in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Using the Homeostasis Model Assessment. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 83, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, K.R.; Oh, S.H.; Chae, S.J.; Yoon, S.H.; Choi, Y.M. Prevalence of Insulin Resistance in Korean Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome According to Various Homeostasis Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance Cutoff Values. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 959–966.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepto, N.K.; Cassar, S.; Joham, A.E.; Hutchison, S.K.; Harrison, C.L.; Goldstein, R.F.; Teede, H.J. Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Have Intrinsic Insulin Resistance on Euglycaemic-Hyperinsulaemic Clamp. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateguana, N.B.; Janes, A.W. The Contribution of Hyperinsulinemia to the Hyperandrogenism of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Insul. Resist. 2019, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghetti, P. The Multifarious Role of Insulin in PCOS: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Management. In Polycystic Ovary Syndrome; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kayampilly, P.P.; Wanamaker, B.L.; Stewart, J.A.; Wagner, C.L.; Menon, K.M.J. Stimulatory Effect of Insulin on 5alpha-Reductase Type 1 (SRD5A1) Expression through an Akt-Dependent Pathway in Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 5030–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, I.; Yen, H.-W.; Geller, D.H.; Torbati, D.; Bierden, R.M.; Weitsman, S.R.; Agarwal, S.K.; Magoffin, D.A. Insulin Augmentation of 17alpha-Hydroxylase Activity Is Mediated by Phosphatidyl Inositol 3-Kinase but Not Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase-1/2 in Human Ovarian Theca Cells. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, J.E.; Jakubowicz, D.J.; de Vargas, A.F.; Brik, C.; Quintero, N.; Medina, F. Insulin Stimulates Testosterone Biosynthesis by Human Thecal Cells from Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome by Activating Its Own Receptor and Using Inositolglycan Mediators as the Signal Transduction System. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 2001–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, I.J.; Kumar, S.S.; Stroup, D.F.; Laredo, S.E. The Association Between the Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill and Insulin Resistance, Dysglycemia and Dyslipidemia in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosorin, M.-E.; Piltonen, T.; Rantala, A.S.; Kangasniemi, M.; Korhonen, E.; Bloigu, R.; Tapanainen, J.S.; Morin-Papunen, L. Oral and Vaginal Hormonal Contraceptives Induce Similar Unfavorable Metabolic Effects in Women with PCOS: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, J.V.M.; Nunes, N.; Ferreira, L.G.R.; Vilar, T.; Pinheiro, M.D.B.; Domingueti, C.P. Evaluation of Lipid Profile, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and D-Dimer in Users of Oral Contraceptives of Different Types. J. Bras. Patol. E Med. Lab. 2018, 54, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.R.D.; Aleluia, M.M.; Figueiredo, C.V.B.; Vieira, L.C.D.L.; Santiago, R.P.; Guarda, C.C.D.; Barbosa, C.G.; Oliveira, R.R.; Adorno, E.V.; Gonçalves, M. de S. Evaluation of Cardiometabolic Parameters among Obese Women Using Oral Contraceptives. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniji, A.A.; Essah, P.A.; Nestler, J.E.; Cheang, K.I. Metabolic Effects of a Commonly Used Combined Hormonal Oral Contraceptive in Women with and Without Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Womens Health 2016, 25, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrbíková, J.; Cibula, D. Combined Oral Contraceptives in the Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. Update 2005, 11, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Li, Y. Role of Gut Microbiota in the Development of Insulin Resistance and the Mechanism Underlying Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Review. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Ling, Y.; Fu, H.; Dong, W.; Shen, J.; et al. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota Associated with Clinical Parameters in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Lai, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Z. Structural and Functional Profiles of the Gut Microbial Community in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome with Insulin Resistance (IR-PCOS): A Pilot Study. Res. Microbiol. 2019, 170, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Shuai, P.; Shen, S.; Zheng, H.; Sun, P.; Zhang, R.; Lan, S.; Lan, Z.; Jayawardana, T.; Yang, Y.; et al. Perturbations in Gut Microbiota Composition in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, M.; Li, Z.; You, H.N.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Jump, D.B.; Morgun, A.; Shulzhenko, N. Role of Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes Pathophysiology. eBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.N.; Kim, M.G.; Bennett, B.J. Modulating the Microbiota as a Therapeutic Intervention for Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 632335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, H.; Rashmi, H.M.; Batish, V.K.; Grover, S. Probiotics as Potential Biotherapeutics in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes—Prospects and Perspectives. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2013, 29, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonucci, L.B.; Santos, K.M.O.D.; Ferreira, C.L.D.L.F.; Ribeiro, S.M.R.; Oliveira, L.L.D.; Martino, H.S.D. Gut Microbiota and Probiotics: Focus on Diabetes Mellitus. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2296–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florowska, A.; Hilal, A.; Florowski, T. Prebiotics and Synbiotics. In Probiotics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Mandeep; Shukla, P. Probiotics of Diverse Origin and Their Therapeutic Applications: A Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkmen, O.; Bozoğlu, T. Probiotics and Prebiotics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilinezhad, Z.; Barati-Boldaji, R.; Brett, N.R.; De Zepetnek, J.O.T.; Bellissimo, N.; Babajafari, S.; Sohrabi, Z. The Effect of Synbiotics Pomegranate Juice on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in PCOS Patients: A Randomized, Triple-Blinded, Controlled Trial. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 43, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilinezhad, Z.; Babajafari, S.; Sohrabi, Z.; Eskandari, M.-H.; Amooee, S.; Barati-Boldaji, R. Effect of Synbiotic Pomegranate Juice on Glycemic, Sex Hormone Profile and Anthropometric Indices in PCOS: A Randomized, Triple Blind, Controlled Trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaei, T.; Heidari-Beni, M.; Tehrani, H.; Feizi, A.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Askari, G. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Pancreatic β-Cell Function and c-Reactive Protein in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, S.; Rafraf, M.; Asaghari Jafarabadi, M.; Farzadi, L. Synbiotic Supplementation Improves Metabolic Factors and Obesity Values in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Independent of Affecting Apelin Levels: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoorani, P.; Ejtahed, H.-S.; Marvasti, F.E.; Taghavi, M.; Ahranjani, B.M.; Hasani-Ranjbar, S.; Larijani, B. The Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1141355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Rossi, V.; Massini, G.; Casini, F.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Fabiano, V. Probiotics and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Perspective for Management in Adolescents with Obesity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App for Producing PRISMA 2020-Compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, E.; Moini, A.; Yaseri, M.; Shirzad, N.; Sepidarkish, M.; Hossein-Boroujerdi, M.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J. Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation on Metabolic Parameters and Apelin in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samimi, M.; Dadkhah, A.; Haddad Kashani, H.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Seyed Hosseini, E.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation on Metabolic Status in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Gholizadeh Shamasbi, S.; Dehgan, P.; Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi, S.; Aliasgarzadeh, A.; Mirghafourvand, M. The Effect of Resistant Dextrin as a Prebiotic on Metabolic Parameters and Androgen Level in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Controlled, Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Hossein-Boroujerdi, M.; Moini, A.; Sepidarkish, M.; Shirzad, N.; Karimi, E. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Hormonal and Clinical Outcomes of Women Diagnosed with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 96, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamali, M.; Eghbalpour, S.; Rajabi, S.; Jamilian, M.; Bahmani, F.; Tajabadi, M.; Keneshlou, F.; Mirhashemi, S.M.; Chamani, M.; Gelougerdi, S.H.; et al. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Hormonal Profiles, Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arch. Iran. Med. 2018, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, E.; Heshmati, J.; Shirzad, N.; Vesali, S.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J.; Moini, A.; Sepidarkish, M. The Effect of Synbiotics Supplementation on Anthropometric Indicators and Lipid Profiles in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, K.; Jamilian, M.; Rahmani, E.; Bahmani, F.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation on Hormonal Status, Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Subjects with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, N.; Mousa, S.A. The Shortcomings of Clinical Trials Assessing the Efficacy of Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2012, 18, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamasbi, S.G.; Ghanbari-Homayi, S.; Mirghafourvand, M. The Effect of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Hormonal and Inflammatory Indices in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Ling, Y.; Jin, W.; Su, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, J.; et al. Evaluation of Superinfection, Antimicrobial Usage, and Airway Microbiome with Metagenomic Sequencing in COVID-19 Patients: A Cohort Study in Shanghai. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2021, 54, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musazadeh, V.; Mohammadi Anilou, M.; Vajdi, M.; Karimi, A.; Sedgh Ahrabi, S.; Dehghan, P. Effects of Synbiotics Supplementation on Anthropometric and Lipid Profile Parameters: Finding from an Umbrella Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1121541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, M.; Vitagliano, A. Probiotics and Synbiotics for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcfarland, L.V.; Evans, C.T.; Goldstein, E.J.C. Strain-Specificity and Disease-Specificity of Probiotic Efficacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Lactic Acid Bacteria Alleviate Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome by Regulating Sex Hormone Related Gut Microbiota. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5192–5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiattarella, A.; Riemma, G.; Verde, M.L.; Franci, G.; Chianese, A.; Fasulo, D.; Fichera, M.; Gallo, P.; Franciscis, P.D. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Probiotics: A Natural Approach to an Inflammatory Disease. Curr. Women Health Rev. 2021, 17, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M. Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Insulin Sensitivity. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2017, 31, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liscano, Y.; Sanchez-Palacio, N. A Critical Look at Omega-3 Supplementation: A Thematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puddu, A.; Sanguineti, R.; Montecucco, F.; Viviani, G.L. Evidence for the Gut Microbiota Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Pathophysiological Molecules Improving Diabetes. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 162021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, O.; Christ, J.P.; Schulze-Rath, R.; Covey, J.; Kelley, A.; Grafton, J.; Cronkite, D.; Holden, E.; Hilpert, J.; Sacher, F.; et al. Incidence, Prevalence, and Trends in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Diagnosis: A United States Population-Based Study from 2006 to 2019. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 229, 39.e1–39.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.A.; Gahan, C.G.M. Bile Acid Modifications at the Microbe-Host Interface: Potential for Nutraceutical and Pharmaceutical Interventions in Host Health. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Ze, X.; Deng, C.; Xu, S.; Ye, F. Multispecies Probiotics Complex Improves Bile Acids and Gut Microbiota Metabolism Status in an In Vitro Fermentation Model. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1314528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestler, J.E. Role of Hyperinsulinemia in the Pathogenesis of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, and Its Clinical Implications. Semin. Reprod. Endocrinol. 1997, 15, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, U.; Hassan, J.A.; Ismail, K.; Agha, S.; Memon, Z.; Bhatty, S. Effectiveness of Probiotics, Metformin and Their Combination Therapy in Ameliorating Dyslipidemia Associated with PCOS. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2019, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, C.J.M.U.; Bezerra, A.N. Effects of Probiotics on the Lipid Profile: Systematic Review. J. Vasc. Bras. 2019, 18, e20180124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sola-Leyva, A.; Pérez-Prieto, I.; Molina, N.M.; Vargas, E.; Ruiz-Durán, S.; Leonés-Baños, I.; Canha-Gouveia, A.; Altmäe, S. Microbial Composition Across Body Sites in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2023, 47, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M.R.; Pontes, K.S.D.S.; Silva, M.I.B.; Neves, M.F.T.; Klein, M.R.S.T. Randomized Controlled Trials Reporting the Effects of Probiotics in Individuals with Overweight and Obesity: A Critical Review of the Interventions and Body Adiposity Parameters. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, G.R.; Murphy, R.; Brough, L.; Butts, C.A.; Coad, J. Interindividual Variability in Gut Microbiota and Host Response to Dietary Interventions. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 1059–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Shao, J.; Yang, Y.; Niu, X.; Liao, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, S.; Hu, J. Gut Microbiota in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubnov, R.V.; Spivak, M.Y. Towards Individualized Use of Probiotics and Prebiotics for Metabolic Syndrome and Associated Diseases Treatment: Does Pathophysiology-Based Approach Work and Can Anticipated Evidence Be Completed? Probiotics 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejtahed, H.-S.; Hasani-Ranjbar, S.; Larijani, B. Human Microbiome as an Approach to Personalized Medicine. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2017, 23, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, S.M.; Gurry, T.; Lampe, J.W.; Chakrabarti, A.; Dam, V.; Everard, A.; Goas, A.; Gabriele, G.; Kleerebez, M.; Lane, J.; et al. Perspective: Leveraging the Gut Microbiota to Predict Personalized Responses to Dietary, Prebiotic, and Probiotic Interventions. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, G.V.D.M.; Coelho, B.D.O.; Júnior, A.I.M.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. How to Select a Probiotic? A Review and Update of Methods and Criteria. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 2060–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniffen, J.; Mcfarland, L.V.; Evans, C.T.; Goldstein, E.J.C. Choosing an Appropriate Probiotic Product for Your Patient: An Evidence-Based Practical Guide. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippis, F.D.; Vitaglione, P.; Cuomo, R.; Canani, R.B.; Ercolini, D. Dietary Interventions to Modulate the Gut Microbiome—How Far Away Are We from Precision Medicine. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 2142–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panebianco, C.; Andriulli, A.; Pazienza, V. Pharmacomicrobiomics: Exploiting the Drug-Microbiota Interactions in Anticancer Therapies. Microbiome 2018, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, C.T.; Moran, L.J.; Wijeyaratne, C.N.; Redman, L.M.; Norman, R.J.; Teede, H.J.; Joham, A.E. Integrated Model of Care for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2018, 36, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochar, D.N.; Solanke, M.S.; Chandewar, D.A. Probiotic Interventions for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome—A Comprehensive Review. Sch. Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 7, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtdaş, G.; Akdevelioğlu, Y. A New Approach to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Gut Microbiota. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 39, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, M.; Bhatnager, R.; Kumar, A.; Suneja, P.; Dang, A.S. Interplay Between PCOS and Microbiome: The Road Less Travelled. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022, 88, e13580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, F.E.C.; Guevara-Montoya, M.C.; Serna-Ramirez, V.; Liscano, Y. Neuroinflammation and Schizophrenia: New Therapeutic Strategies through Psychobiotics, Nanotechnology, and Artificial Intelligence (AI). J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, F.E.C.; Lizcano Martinez, S.; Liscano, Y. Effectiveness of Psychobiotics in the Treatment of Psychiatric and Cognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Jiao, J.; Jia, S.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Yang, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, D.; Wang, X. 16S rDNA Full-Length Assembly Sequencing Technology Analysis of Intestinal Microbiome in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 634981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Li, G.; Xu, Y.; He, X.; Song, B.; Cao, Y. Characterization of the Gut Microbiota in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome with Dyslipidemia. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Fu, H.; Su, H.; Cai, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Hu, J.; Xie, Z.; Wang, X. Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal the Specific Changes in Gut Metagenome and Serum Metabolome of Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1017147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design |

|

|

| ||

| Participants |

|

|

| ||

| Interventions |

|

|

| Duration |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Language |

|

|

| Study Reference | Country | Diagnostic Criteria | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2018 [38] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Triple-blind RCT |

| Shoaei et al., 2021 [39] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Darvishi et al., 2020 [40] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Karimi et al., 2018 [45] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Samimi et al., 2018 [46] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2019 [37] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Triple-blind RCT |

| Gholizadeh Shamasbi et al., 2018 [48] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Triple-blind RCT |

| Arab et al., 2022 [49] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Karamali et al., 2018 [50] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Karimi et al., 2020 [51] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Nasri et al., 2018 [52] | Iran | Rotterdam criteria for PCOS | Double-blind RCT |

| Study Reference | Participants | Size | Age (Years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Baseline Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2018 [38] | Women | I (pomegranate+synbiotic): 23, I (pomegranate): 23, I (synbiotic beverage): 23, C: 23 | 15–48 | 25–28 | Synbiotic pomegranate juice: HOMA-IR: 6.32 ± 1.32 FBS: 112.04 ± 9.41 mg/dL Insulin: 22.80 ± 3.97 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.294 ± 0.008; pomegranate juice: HOMA-IR: 6.16 ± 1.17 FBS: 112.82 ± 12.61 mg/dL Insulin: 22.15 ± 3.48 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.295 ± 0.007; synbiotic beverage: HOMA-IR: 6.11 ± 1.22 FBS: 112.65 ± 8.46 mg/dL Insulin: 22.02 ± 4.32 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.295 ± 0.008; control: HOMA-IR: 6.95 ± 0.91 FBS: 114.56 ± 8.16 mg/dL Insulin: 24.66 ± 3.33 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.290 ± 0.004 |

| Shoaei et al., 2021 [39] | Women | I (probiotic): 36 C (placebo): 36 | 15–40 | 25–30 | Probiotic: HOMA-IR: 2.11 ± 0.21 FBS: 85.7 ± 2.6 mg/dL Insulin: 9.8 ± 0.9 μIU/mL QUICKI: N/A; placebo: HOMA-IR: 2.05 ± 0.23 FBS: 86.2 ± 2.5 mg/dL Insulin: 9.7 ± 0.8 μIU/mL QUICKI: N/A |

| Darvishi et al., 2020 [40] | Women | I (synbiotic): 34 C (placebo): 34 | 20–44 | ≥25 | Synbiotic: HOMA-IR: 3.06 ± 1.35 FBS: 91.32 ± 8.07 mg/dL Insulin: 13.36 ± 4.89 μIU/mL HDL: 45.79 ± 12.05 mg/dL; placebo: HOMA-IR: 2.10 ± 1.12 FBS: 89.02 ± 9.05 mg/dL Insulin: 9.46 ± 4.64 μIU/mL HDL: 48.14 ± 10.22 mg/dL |

| Karimi et al., 2018 [45] | Women | I (synbiotic): 44 C (placebo): 44 | 19–37 | ≥25 | Synbiotic: HOMA-IR: 3.77 ± 2.35 FBS: 92 ± 9 mg/dL Apelin 36: 27 ± 21 nmol/L CRP: 6.9 ± 5.99 mg/L; placebo: HOMA-IR: 3.6 ± 1.92 FBS: 90 ± 9 mg/dL Apelin 36: 26 ± 15 nmol/L CRP: 4.74 ± 4.68 mg/L |

| Samimi et al., 2018 [46] | Women | I (synbiotic): 30 C (placebo): 30 | 18–40 | 27–35 | Synbiotic: FPG: 92.2 ± 6.2 mg/dL Insulin: 12.9 ± 4.2 μIU/mL HOMA-IR: 3.0 ± 1.1 Triglycerides: 146.4 ± 56.3 mg/dL VLDL: 29.3 ± 11.2 mg/dL AIP: 0.49 ± 0.20 Placebo: FPG: 94.0 ± 5.7 mg/dL Insulin: 12.1 ± 6.3 μIU/mL HOMA-IR: 2.8 ± 1.4 Triglycerides: 138.2 ± 37.9 mg/dL VLDL: 27.6 ± 7.6 mg/dL AIP: 0.44 ± 0.16 |

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2019 [37] | Women | SPJ (synbiotic pomegranate juice): 23 PJ (pomegranate juice): 23 SB (synbiotic beverage): 23 PB (placebo beverage): 23 | 15–48 | ~25–28 | SPJ: TGs: 171 ± 57 mg/dL TC: 180 ± 32 mg/dL LDL-C: 96 ± 35 mg/dL HDL-C: 50 ± 12 mg/dL SBP: 128 ± 7 mmHg Placebo: TGs: 194 ± 67 mg/dL TC: 194 ± 23 mg/dL LDL-C: 113 ± 27 mg/dL HDL-C: 42 ± 10 mg/dL SBP: 134 ± 7 mmHg |

| Gholizadeh Shamasbi et al., 2018 [48] | Women | I: 31 C: 31 | 18–45 | 25–40 | Prebiotic: LDL-C: 106.87 ± 34.7 mg/dL HDL-C: 40.55 ± 8.8 mg/dL Total cholesterol: 166.90 ± 38.6 mg/dL TGs: 96.77 ± 35.7 mg/dL FBS: 80.68 ± 12.3 mg/dL hs-CRP: 4.70 ± 2.6 mg/dL Free testosterone: 1.25 ± 0.9 pg/mL DHEA-S: 3.18 ± 2.2 μg/mL |

| Arab et al., 2022 [49] | Women | I: 45 C: 43 | 15–40 | ≥25 | Probiotic: SHBG: 36.11 ± 10.87 nmol/mL Total testosterone: 0.42 ± 0.14 ng/mL FAI: 3.24 ± 1.1 DHEA-S: 6.9 ± 2.8 nmol/L |

| Karamali et al., 2018 [50] | Women | I: 30 C: 30 | 18–40 | ≥25 | Probiotic: SHBG: 46.3 ± 10.3 nmol/L Total testosterone: 1.3 ± 0.7 ng/mL mF-G scores: 14.1 ± 4.9 hs-CRP: 3546.7 ± 1003.1 ng/mL TAC: 935.5 ± 344.8 mmol/L MDA: 2.1 ± 0.4 μmol/L |

| Karimi et al., 2020 [51] | Women | I: 44 C: 44 | 19–37 | ≥25 | Synbiotic: LDL: 97 ± 19 mg/dL HDL: 46.44 ± 7.69 mg/dL Total cholesterol (TC): 175.2 ± 27.5 mg/dL Triglycerides (TGs): 139 ± 78 mg/dL |

| Nasri et al., 2018 [52] | Women | I: 30 C: 30 | 18–40 | ≥25 | Synbiotic: SHBG: 37.3 ± 13.1 nmol/L Total testosterone: 2.8 ± 1.3 ng/mL mF-G scores: 15.3 ± 5.6 hs-CRP: 2920 ± 2251.2 ng/mL NO: 39.0 ± 3.1 μmol/L MDA: 2.3 ± 0.4 μmol/L |

| Study Reference | Prebiotic, Probiotic, or Synbiotic Type | Pharmaceutical Form | Dosage | Duration | Comparison Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2018 [38] | Synbiotic in pomegranate juice (SPJ) | Juice | 2 L per week | 12 weeks | Placebo pomegranate juice |

| Shoaei et al., 2021 [39] | Multistrain probiotic with L. casei, L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, L. bulgaricus, B. breve, B. longum, and S. thermophilus | Capsule | One 500 mg capsule daily | 8 weeks | Placebo (starch and maltodextrin) |

| Darvishi et al., 2020 [40] | Synbiotic (Lactobacillus casei, L. rhamnosus, L. bulgaricus, L. acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum, and Streptococcus thermophilus) and prebiotic (inulin and FOS) | Capsule | 1 capsule daily, 500 mg | 8 weeks | Placebo |

| Karimi et al., 2018 [45] | Synbiotic with 7 strains of probiotics (L. acidophilus, L. casei, L. bulgaricus, L. rhamnosus, B. longum, B. breve, and S. thermophilus) and prebiotic inulin (fructo-oligosaccharide) | Capsule | 1 capsule daily, 1000 mg | 12 weeks | Placebo |

| Samimi et al., 2018 [46] | Synbiotic with L. acidophilus, L. casei, B. bifidum, and 800 mg inulin | Capsule | 2 × 109 CFU/g of each strain + 800 mg inulin daily | 12 weeks | Placebo |

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2019 [37] | Synbiotic in pomegranate juice (Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, Bacillus coagulans, and Bacillus indicus) | Juice | 300 mL daily | 8 weeks | Placebo (flavored water) |

| Gholizadeh Shamasbi et al., 2018 [48] | Prebiotic (dextrin) | Powder (diluted in water) | 20 g daily | 12 weeks | Placebo (maltodextrin) |

| Arab et al., 2022 [49] | Multistrain probiotic with multiple strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus (3 × 1010 CFU/g), Lactobacillus casei (3 × 109 CFU/g), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (1.5 × 109 CFU/g), Lactobacillus bulgaricus (5 × 108 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium breve (2 × 1010 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium longum (7 × 109 CFU/g), Streptococcus thermophilus (3 × 108 CFU/g) + 800 mg inulin | Capsule | One 500 mg capsule daily (7 strains + 800 mg inulin) | 12 weeks | Placebo (starch and maltodextrin) |

| Karamali et al., 2018 [50] | Multistrain probiotic with multiple strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus (3 × 1010 CFU/g), Lactobacillus casei (3 × 109 CFU/g), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (1.5 × 109 CFU/g), Lactobacillus bulgaricus (5 × 108 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium breve (2 × 1010 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium longum (7 × 109 CFU/g), Streptococcus thermophilus (3 × 108 CFU/g) + 800 mg inulin | Capsule | Two capsules daily (500 mg each: 7 strains + 800 mg inulin) | 12 weeks | Placebo (starch and maltodextrin) |

| Karimi et al., 2020 [51] | Synbiotics with multiple strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus (3 × 1010 CFU/g), Lactobacillus casei (3 × 109 CFU/g), Lactobacillus bulgaricus (5 × 108 CFU/g), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (7 × 109 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium longum (1 × 109 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium breve (2 × 1010 CFU/g), Streptococcus thermophilus (3 × 108 CFU/g) + inulin (fructooligosaccharide) | Capsules | Two capsules daily (500 mg each: 7 strains + inulin) | 12 weeks | Placebo (starch and maltodextrin) |

| Nasri et al., 2018 [52] | Synbiotic with multiple strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus (2 × 109 CFU/g), Lactobacillus casei (2 × 109 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium bifidum (2 × 109 CFU/g) + 0.8 g inulin | Capsules | Two 500 mg capsules daily (3 strains + inulin) | 12 weeks | Placebo (starch and maltodextrin) |

| Study Reference | Post-Intervention Parameters | Change in Parameters (Δ) | Comparative Effects | Adherence to the Intervention | Side Effects | Primary Outcomes | Secondary Outcomes | Measurement Methods | Key Findings | Author Conclusions | Study Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2018 [38] | Synbiotic pomegranate juice: HOMA-IR: 5.75 ± 1.22; pomegranate juice: HOMA-IR: 6.20 ± 1.23; Synbiotic beverage: HOMA-IR: 5.61 ± 0.99 FBS: 111.47 ± 6.58 mg/dL Insulin: 20.36 ± 3.35 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.29 ± 0.007 FBS: 113.68 ± 10.63 mg/dL Insulin: 22.07 ± 3.74 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.29 ± 0.007 FBS: 110.36 ± 6.57 mg/dL Insulin: 21.03 ± 3.94 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.29 ± 0.008; Control: HOMA-IR: 7.33 ± 0.92 FBS: 115.00 ± 7.85 mg/dL Insulin: 25.89 ± 3.11 μIU/mL QUICKI: 0.28 ± 0.004 | Synbiotic pomegranate juice: ΔHOMA-IR: −0.57 ΔFBS: −1.68 mg/dL ΔInsulin: −1.77 μIU/mL; pomegranate juice: ΔHOMA-IR: +0.04 ΔFBS: +0.86 mg/dL ΔInsulin: −0.08 μIU/mL ΔQUICKI: 0.00; synbiotic beverage: ΔHOMA-IR: −0.50 ΔFBS: −1.18 mg/dL ΔInsulin: −1.66 μIU/mL ΔQUICKI: 0.00; Control: ΔHOMA-IR: +0.38 ΔFBS: +0.44 mg/dL ΔInsulin: +1.23 μIU/mL ΔQUICKI: −0.01 | Synbiotic pomegranate juice: significant improvement (p < 0.05); pomegranate juice: no significant change; synbiotic beverage: moderate improvement (p < 0.05); control: no significant improvement | 95% adherence, as most participants completed the study | None | Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), fasting glucose | Testosterone, insulin sensitivity, lipid profile | ELISA for insulin and HOMA-IR, standard biochemical analysis | Significant reduction in HOMA-IR, increased insulin sensitivity, decreased testosterone | Synbiotic pomegranate juice improves insulin resistance and hormone levels in PCOS | Small sample size, lack of long-term follow-up |

| Shoaei et al., 2021 [39] | Probiotic: HOMA-IR: 1.9 ± 0.2 FBS: 81.5 ± 2.1 mg/dL Insulin: 9.3 ± 0.71 μIU/mL QUICKI: N/A Placebo: HOMA-IR: 2.00 ± 0.22 FBS: 88.3 ± 2.7 mg/dL Insulin: 9.8 ± 0.8 μIU/mL QUICKI: N/A | ΔHOMA-IR: probiotic: −0.21 vs. placebo: −0.05 ΔFBS: probiotic: −4.15 mg/dL vs. placebo: +2.57 mg/dL ΔInsulin: probiotic: −0.49 μIU/mL vs. placebo: +0.34 μIU/mL | Probiotic group showed non-significant changes in FBS, insulin, and HOMA-IR (p = 0.7); however, after adjusting for covariates, insulin reduction was significant in the probiotic group (p = 0.02) | 90% adherence, most participants completed the study | None | Pancreatic β-cell function (FBS, serum insulin, HOMA-IR, QUICKI), CRP (C-reactive protein) | Insulin, lipid profile, hs-CRP | Standard biochemical analyses, immunoassay for insulin, HOMA-IR and QUICKI calculations | Non-significant reduction in FBS, serum insulin, and HOMA-IR in probiotic group; after adjusting for covariates, insulin reduction was significant; no significant differences in CRP | Probiotic supplementation for 8 weeks had a non-significant beneficial effect on pancreatic β-cell function and CRP | Short study duration, no glucose tolerance tests or hormonal evaluations |

| Darvishi et al., 2020 [40] | Synbiotic: HOMA-IR: 2.58 ± 1.15 FBS: 90.08 ± 7.90 mg/dL Insulin: 11.50 ± 4.75 μIU/mL HDL: 47.11 ± 12.73 mg/dL; placebo: HOMA-IR: 3.08 ± 1.31 FBS: 94.44 ± 9.49 mg/dL Insulin: 13.17 ± 5.29 μIU/mL HDL: 44.23 ± 10.73 mg/dL | ΔHOMA-IR: synbiotic: −0.47 vs. placebo: +0.98 ΔFBS: synbiotic: −1.24 mg/dL vs. placebo: +5.42 mg/dL ΔInsulin: synbiotic: −1.86 μIU/mL vs. placebo: +3.71 μIU/mL ΔHDL: synbiotic: +1.32 mg/dL vs. placebo: −3.91 mg/dL | Synbiotic group showed significant improvement in HOMA-IR, FBS, insulin, and HDL levels (p < 0.05) compared to placebo | 95% adherence, all participants completed the study | None | Glycemic indices, lipid profile, obesity values | Serum apelin levels | Standard biochemical analysis, ELISA, anthropometric measurements | Significant improvements in glycemic indices, lipid profile, and obesity values; no changes in apelin | Synbiotic supplementation improves metabolic factors and obesity in women with PCOS | Short study duration, no evaluation of bacterial flora or SCFAs, only overweight/obese patients included |

| Karimi et al., 2018 [45] | Synbiotic: HOMA-IR: 3.82 ± 2.27 FBS: 92 ± 11 mg/dL Apelin 36: 14.4 ± 4.5 nmol/L CRP: 5.2 ± 3.9 mg/L; Placebo: HOMA-IR: 3.8 ± 2.46 FBS: 91 ± 10 mg/dL Apelin 36: 18.4 ± 9.2 nmol/L CRP: 4.9 ± 4.8 mg/L | ΔHOMA-IR: synbiotic: +0.05 vs. placebo: +0.2 ΔFBS: synbiotic: +0.6 mg/dL vs. placebo: +0.95 mg/dL ΔApelin 36: synbiotic: −12.6 nmol/L vs. placebo: −7.6 nmol/L ΔCRP: synbiotic: −1.7 mg/L vs. placebo: −0.24 mg/L | Synbiotic group showed a significant decrease in apelin 36 levels (p = 0.004) compared to placebo. No significant changes in metabolic parameters such as HOMA-IR, FBS, or CRP | Approx. 90% adherence, with 11 participants lost to follow-up | None | Metabolic parameters (fasting glucose, 2 h plasma glucose, HbA1c, HOMA-IR, QUICKI), fasting insulin, C-reactive protein (CRP), apelin 36 levels | QUICKI, CRP | Standard biochemical analysis, immunoturbidimetry for HbA1c and CRP, ELISA for apelin 36, HOMA-IR and QUICKI calculations | No significant differences in metabolic parameters, fasting insulin, or CRP after 12 weeks; significant decrease in apelin 36 | Synbiotic supplementation had no significant effects on metabolic and inflammatory parameters; decrease in apelin 36 | No examination of bacterial flora changes, potential reporting biases |

| Samimi et al., 2018 [46] | Synbiotic: FPG: 88.0 ± 7.2 mg/dL Insulin: 10.1 ± 3.9 μIU/mL HOMA-IR: 2.3 ± 0.9 Triglycerides: 130.3 ± 39.3 mg/dL VLDL: 26.0 ± 7.9 mg/dL AIP: 0.43 ± 0.16 Placebo: FPG: 92.8 ± 8.1 mg/dL Insulin: 13.9 ± 5.2 μIU/mL HOMA-IR: 3.2 ± 1.2 Triglycerides: 144.0 ± 47.2 mg/dL VLDL: 28.8 ± 9.4 mg/dL AIP: 0.43 ± 0.22 | ΔFPG: synbiotic: −4.1 mg/dL vs. placebo: −1.2 mg/dL ΔInsulin: synbiotic: −2.8 μIU/mL vs. placebo: +1.8 μIU/mL ΔHOMA-IR: synbiotic: −0.7 vs. placebo: +0.4 ΔTriglycerides: synbiotic: −16.2 mg/dL vs. placebo: +5.8 mg/dL ΔVLDL: synbiotic: −3.3 mg/dL vs. placebo: +1.1 mg/dL ΔAIP: synbiotic: −0.05 vs. placebo: −0.003 | Significant reduction in insulin, HOMA-IR, triglycerides, VLDL-cholesterol, and AIP in the synbiotic group (p < 0.05) compared to placebo. No significant differences observed in total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, or HDL-cholesterol | Approx. 95% adherence; 4 participants (2 from each group) were lost to follow-up due to personal reasons | None | Glycemic control markers (insulin, HOMA-IR, QUICKI) | Lipid profile (triglycerides, VLDL-C, AIP) | Standard biochemical analyses, ELISA for insulin, HOMA-IR and QUICKI calculations | Significant decrease in serum insulin, HOMA-IR, triglycerides, VLDL cholesterol, and AIP; significant increase in QUICKI in synbiotic group | Improvement in insulin resistance markers and some lipid parameters | Short follow-up, no SCFAs measured in stool |

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2019 [37] | SPJ: TGs: −26.4 mg/dL TC: −13.4 mg/dL LDL-C: −18.9 mg/dL HDL-C: +10.7 mg/dL SBP: −5.6 mmHg Placebo: TGs: +4.0 mg/dL TC: +4.3 mg/dL LDL-C: +7.2 mg/dL HDL-C: −3.7 mg/dL SBP: +1.5 mmHg | ΔTGs: SPJ: −26.4 mg/dL vs. placebo: +4.0 mg/dL ΔTC: SPJ: −13.4 mg/dL vs. placebo: +4.3 mg/dL ΔLDL-C: SPJ: −18.9 mg/dL vs. placebo: +7.2 mg/dL ΔHDL-C: SPJ: +10.7 mg/dL vs. placebo: −3.7 mg/dL ΔSBP: SPJ: −5.6 mmHg vs. placebo: +1.5 mmHg | Significant improvement in TGs, LDL-C, HDL-C, and SBP in the SPJ group compared to placebo. Increases in antioxidant capacity (TAC) and reductions in oxidative stress (MDA) were also noted | High adherence (≥90%); reminder messages were sent weekly, and empty bottles were returned to ensure compliance | None | Lipid profile, oxidative stress (MDA, TAC), hs-CRP, blood pressure | Not specified | Standard biochemical analysis, ELISA for hs-CRP, MDA and TAC measurements, blood pressure | Significant improvements in lipid profile, oxidative stress, inflammation, and blood pressure in SPJ, PJ, and SB groups compared to placebo | Synbiotic pomegranate juice improved metabolic, oxidative, and inflammatory outcomes | No measurement of gut microbiota changes or body composition |

| Gholizadeh Shamasbi et al., 2018 [48] | Prebiotic: LDL-C: 87.35 mg/dL HDL-C: 46.15 mg/dL Total cholesterol: 154.71 mg/dL TGs: 94.22 mg/dL FBS: 67.68 mg/dL hs-CRP: 3.11 mg/dL Free testosterone: 1.06 pg/mL DHEA-S: 2.77 μg/mL | ΔLDL-C: −29.79 mg/dL ΔHDL-C: +5.82 mg/dL ΔTotal cholesterol: −29.98 mg/dL ΔTGs: −38.50 mg/dL ΔFBS: −11.24 mg/dL Δhs-CRP: −1.75 mg/dL ΔFree testosterone: −0.32 pg/mL ΔDHEA-S: −0.7 μg/mL | Significant reduction in LDL-C, total cholesterol, triglycerides, FBS, hs-CRP, DHEA-S, and free testosterone in the prebiotic group compared to placebo. HDL-C increased significantly in the prebiotic group | High adherence (weekly follow-up calls ensured compliance) | Two participants experienced mild allergies and discontinued intervention | Lipid levels, fasting glucose, hs-CRP, DHEA-S, free testosterone | Hirsutism, menstrual irregularity | Standard biochemical analyses, ELISA for hormones, Ferriman–Gallwey scale | Significant decrease in LDL-C, total cholesterol, triglycerides, FBS, hs-CRP, DHEA-S, free testosterone, and hirsutism score; significant increase in HDL-C | Resistant dextrin regulates metabolic parameters and androgen levels in PCOS | Small sample size, participants only overweight/obese |

| Arab et al., 2022 [49] | Probiotic: SHBG: 40.06 ± 9.14 nmol/mL Total testosterone: 0.41 ± 0.15 ng/mL FAI: 3.22 ± 1.2 DHEA-S: 6.84 ± 2.9 nmol/L | ΔSHBG: +3.95 nmol/mL ΔTotal testosterone: −0.01 ng/mL ΔFAI: −0.02 ΔDHEA-S: −0.06 nmol/L | Probiotic supplementation significantly increased SHBG compared to the placebo group, but no significant changes were observed in total testosterone, FAI, DHEA-S, or clinical outcomes (acne, hirsutism) | High adherence: compliance monitored via phone calls, text messages, and capsule return | None | Hormonal and clinical parameters: SHBG, LH, FSH, DHEA-S, TT, FAI | Acne, hirsutism | Hormone profiles by electrochemiluminescence immunoassays, clinical signs evaluated by standardized scales | Significant increase in SHBG; no significant improvements in other hormonal or clinical parameters | Probiotic supplementation improved SHBG but not other hormonal or clinical parameters | Self-report instead of bacterial stool analysis, short duration |

| Karamali et al., 2018 [50] | Probiotic: SHBG: 72.2 ± 31.9 nmol/L Total testosterone: 1.1 ± 0.8 ng/mL mF-G scores: 12.4 ± 3.8 hs-CRP: 2396.7 ± 1588.6 ng/mL TAC: 948.3 ± 380.2 mmol/L MDA: 1.9 ± 0.6 μmol/L | ΔSHBG: +25.9 nmol/L ΔTotal testosterone: −0.2 ng/mL ΔmF-G scores: −1.7 Δhs-CRP: −1150 ng/mL ΔTAC: +8.8 mmol/L ΔMDA: −0.2 μmol/L | Probiotic supplementation significantly increased SHBG, decreased total testosterone, mF-G scores, hs-CRP, and MDA levels, and increased TAC compared to the placebo group. No significant effects on DHEA-S or other metabolic profiles | Compliance monitored via capsule count and daily SMS reminders | None | Hormonal and clinical parameters: SHBG, LH, FSH, DHEA-S, TT, FAI | Acne, hirsutism | Hormonal profile: electrochemiluminescence-based immunometric assays, biomarkers and clinical signs evaluated | Significant improvements in SHBG, decrease in total testosterone, and hs-CRP and TAC | Improvements in SHBG, testosterone, and inflammatory markers | Short duration, other strain combinations or prebiotics not evaluated |

| Karimi et al., 2020 [51] | Synbiotic: LDL: 92 ± 19 mg/dL HDL: 45 ± 8 mg/dL TC: 170 ± 24 mg/dL TGs: 141 ± 78 mg/dL | ΔLDL: −5.27 mg/dL ΔHDL: +1.71 mg/dL ΔTC: −5.2 mg/dL (not significant) ΔTGs: −2.2 mg/dL (not significant) | Synbiotic supplementation significantly decreased LDL levels and increased HDL levels compared to the placebo group. No significant effects were found for total cholesterol or triglycerides | Compliance monitored via capsule count and daily SMS reminders | None | Lipids and anthropometric measures: LDL, HDL, TC, TGs | Anthropometric indicators: weight, BMI, WC, HC, WHR | Lipid profile: TC, TGs, HDL measured by colorimetric methods, anthropometric indicators measured with digital scale | Significant decrease in LDL, increase in HDL; no differences in other anthropometric measures | Improvements in LDL and HDL, no changes in other parameters | Short duration limited to 12 weeks, dietary reporting biases |

| Nasri et al., 2018 [52] | Synbiotic: SHBG: 57.1 ± 48.6 nmol/L Total testosterone: 2.4 ± 0.9 ng/mL mF-G scores: 14.0 ± 4.9 hs-CRP: 1970 ± 1442.0 ng/mL NO: 44.5 ± 5.0 μmol/L MDA: 2.1 ± 0.4 μmol/L | ΔSHBG: +19.8 nmol/L ΔTotal testosterone: −0.4 ng/mL ΔmF-G scores: −1.3 Δhs-CRP: −950 ng/mL ΔNO: +5.5 μmol/L ΔMDA: −0.2 μmol/L | Synbiotic supplementation significantly increased SHBG, decreased mF-G scores, FAI, hs-CRP, and NO levels compared to the placebo group. No significant effects were found for other hormonal markers and biomarkers of oxidative stress | Compliance monitored via capsule count and daily SMS reminders. | None | Hormonal, inflammation, and oxidative stress: SHBG, LH, FSH, DHEA-S, TT, FAI | Inflammation biomarkers: hs-CRP | Hormonal profile: ELISA kits (DiaMetra, Italy), biomarkers: spectrophotometric methods for NO, TAC, GSH, MDA | Significant increase in SHBG, significant decrease in hs-CRP, NO, and mF-G scores | Synbiotics improved SHBG, NO, hs-CRP, and mF-G scores | Short duration, small sample size, no comparison of different combinations |

| Study Name | Randomization (0–2) | Blinding (0–2) | Withdrawals/Dropouts (0–1) | Total Score (Out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2018 [38] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Shoaei et al., 2021 [39] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Darvishi et al., 2020 [40] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Karimi et al., 2018 [45] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Samimi et al., 2018 [46] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Esmaeilinezhad et al., 2019 [37] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Gholizadeh Shamasbi et al., 2018 [48] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Arab et al., 2022 [49] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Karamali et al., 2018 [50] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Karimi et al., 2020 [51] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Nasri et al., 2018 [52] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez Guevara, D.; Vidal Cañas, S.; Palacios, I.; Gómez, A.; Estrada, M.; Gallego, J.; Liscano, Y. Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics in Managing Insulin Resistance and Hormonal Imbalance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223916

Martinez Guevara D, Vidal Cañas S, Palacios I, Gómez A, Estrada M, Gallego J, Liscano Y. Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics in Managing Insulin Resistance and Hormonal Imbalance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2024; 16(22):3916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223916

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez Guevara, Darly, Sinthia Vidal Cañas, Isabela Palacios, Alejandra Gómez, María Estrada, Jonathan Gallego, and Yamil Liscano. 2024. "Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics in Managing Insulin Resistance and Hormonal Imbalance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials" Nutrients 16, no. 22: 3916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223916

APA StyleMartinez Guevara, D., Vidal Cañas, S., Palacios, I., Gómez, A., Estrada, M., Gallego, J., & Liscano, Y. (2024). Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics in Managing Insulin Resistance and Hormonal Imbalance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients, 16(22), 3916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223916