Abstract

Envenomation caused by venomous animals may trigger significant local complications such as pain, edema, localized hemorrhage, and tissue necrosis, in addition to complications such as dermonecrosis, myonecrosis, and even amputations. This systematic review aims to evaluate scientific evidence on therapies used to target local effects caused by envenomation. The PubMed, MEDLINE, and LILACS databases were used to perform a literature search on the topic. The review was based on studies that cited procedures performed on local injuries following envenomation with the aim of being an adjuvant therapeutic strategy. The literature regarding local treatments used following envenomation reports the use of several alternative methods and/or therapies. The venomous animals found in the search were snakes (82.05%), insects (2.56%), spiders (2.56%), scorpions (2.56%), and others (jellyfish, centipede, sea urchin—10.26%). In regard to the treatments, the use of tourniquets, corticosteroids, antihistamines, and cryotherapy is questionable, as well as the use of plants and oils. Low-intensity lasers stand out as a possible therapeutic tool for these injuries. Local complications can progress to serious conditions and may result in physical disabilities and sequelae. This study compiled information on adjuvant therapeutic measures and underscores the importance of more robust scientific evidence for recommendations that act on local effects together with the antivenom.

Key Contribution:

When used properly and depending on its type, local therapy concomitant with antivenom administration can contribute positively to controlling the worsening of local damage caused by envenomation.

1. Introduction

Venomous animals (e.g., snakes, insects, and arachnids) can inoculate venom in humans due to the specific mechanisms they employ to penetrate tissues. Indeed, bites or stings by these animals may promote local and systemic damage to the victim, resulting in important impacts in public health [1]. The severity of the envenomation depends on the amount of venom inoculated, the location of the bite, the victim’s systemic condition, and the length of time between the envenomation occurring and the administration of antivenom. The classification of the envenomation can range from mild local clinical manifestations to more severe systemic complications [2]. Thus, the severity of the envenomation will be responsible for the clinical outcomes, including induced physical disabilities and deaths [2,3,4].

The treatment for envenomation consists of the neutralization of the venom via antivenom administration at the recommended dosage, which is determined according to the severity of the case [3]. Nevertheless, antivenom is more efficient at controlling systemic signs than in neutralizing local induced effects such as edema, localized hemorrhage, and tissue necrosis [2,5]. Actually, for mild envenomation with only local manifestations, besides the antivenom therapy, analgesia and local cold compresses are recommended for pain relief [6,7].

Local damage can progress to dermonecrosis and myonecrosis, leading to tissue loss or even amputations [8]. Thus, in instances of envenomation that present local damage, it is important to use additional combined therapies aimed at restoring tissue homeostasis [5]. Initially, careful cleaning of the wound is fundamental to prevent secondary infection [8]. Due to the wide variety of microorganisms present on the victim’s skin and in the oral cavity of the venomous animal, it may also be necessary to combine antibiotic and anti-tetanus therapies [8,9,10,11].

Knowing the greater predominance of envenomation in rural areas, which are associated with poverty and work activities in the countryside, the use of alternative and traditional treatments to minimize the effects of venoms is frequent due to local culture [5]. Among the therapies, the use of medicinal plants, locally or even orally, stands out as an ancient practice in human history [12]. Moreover, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that some plants have properties that can inhibit the activities of venom and local damage [13,14], while others have no effect [15], although further studies are still necessary. In addition, the use of non-invasive procedures (e.g., laser therapy) to treat local damage has shown to be very promising due to their anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and tissue-regeneration effects; and undoubtedly the application of laser therapy has resulted in positive results, principally in the reduction of the formation of edema, myonecrosis and leukocyte flow [16,17].

Therefore, identification of best practices for local adjuvant treatments could help to mitigate local damage caused by envenomation. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the scientific evidence related to local treatments that, in conjunction with antivenom, may reduce the local effects triggered by envenomation.

2. Results

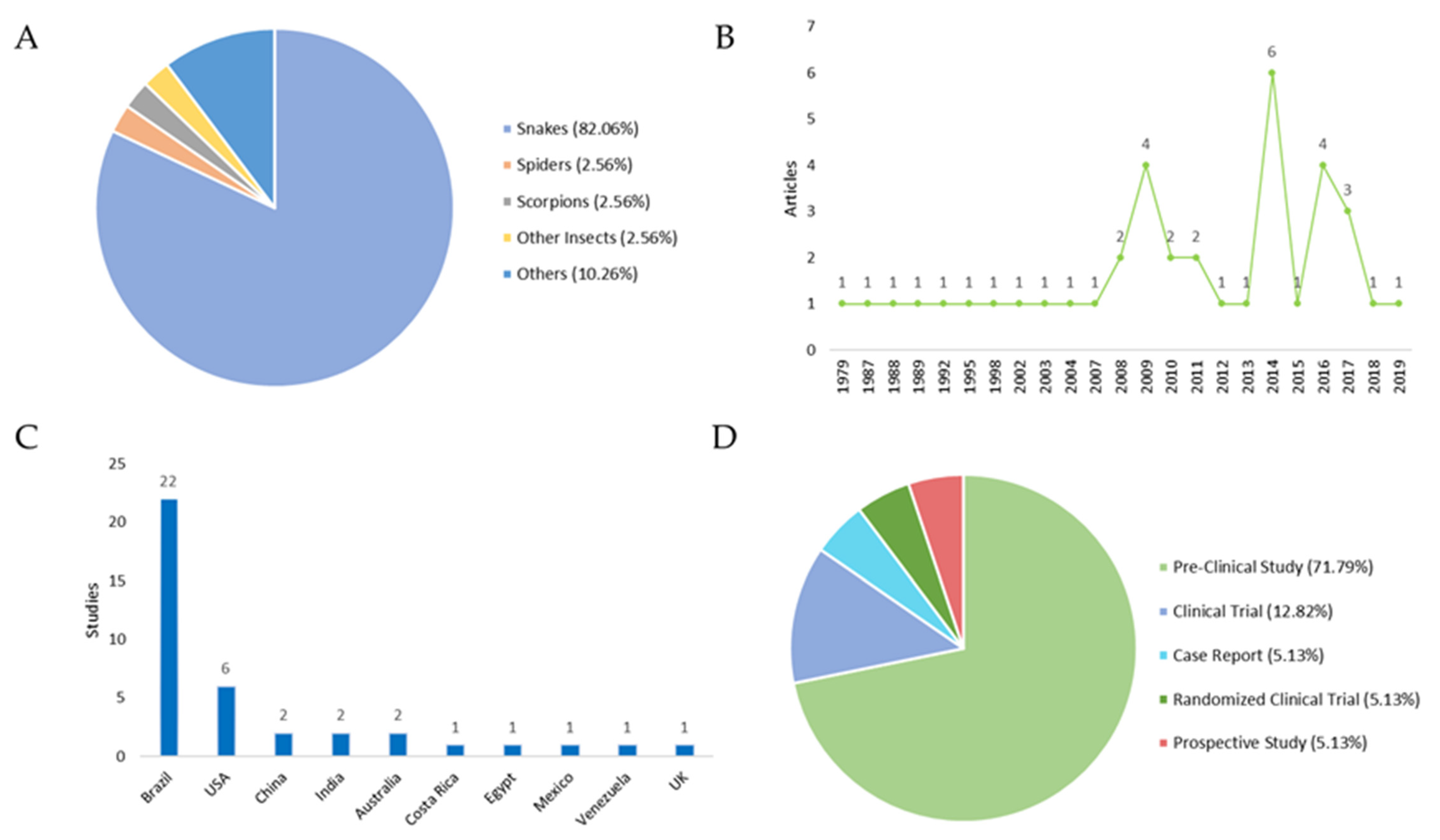

An overview of the 39 included studies can be found in Table 1 and Table 2, which contain the titles, year of publication of the studies, the type of study, the country where they were carried out, and the main aim of each work. The classification of the studies was carried out according to the type of venomous animal: (i) snakes: 82.05%; (ii) insects: 2.56%; (iii) spiders: 2.56%; (iv) scorpions: 2.56%; and (v) others (jellyfish, centipedes, sea urchins): 10.26% (Figure 1A).

Table 1.

Pre-clinical studies from 1988 to 2019 focusing on local therapies following envenomation.

Table 2.

Studies from 1988 to 2019 focusing on local therapies following envenomation.

Figure 1.

Studies focusing on local therapies following envenomation. (A) Distribution of the venomous animals that caused the envenomation. (B) Year of publication of the selected studies. Regarding the publication period are addressed in the periods in which these articles were published. An increase in scientific output is observed in the years 2009, 2014, and 2016. (C) Number of studies by country. All countries cited in the publications were evaluated by the number of studies, with Brazil and USA producing the most. (D) Distribution of study types. In respect to the study type, the following results were obtained: (i) Pre-Clinical Study 71.79%; (ii) Clinical Trials: 12.82%; (iii) Case Reports: 5.13%; Randomized Clinical Trials: 5.13%; and (iv) Prospective Studies: 5.13%.

The aim of each analyzed study was to present a gamut of local treatments to be used in the lesions caused by venomous animals. The analyses identified conventional treatments (such as analgesia, compresses, and tourniquets) and topical/oral medications, including plants and other promising adjuvant treatments (Table 3). The systematic review also evaluated the therapies used in each study and their outcomes (Table 4).

Table 3.

Local treatments according to the animal and indicated and contraindicated or ineffective treatments.

Table 4.

Outcomes of the local treatments used in the evaluated studies.

3. Discussion

Local tissue injury is one of the main forms of damage caused by envenomation. However, the severity of the local effects depends on the venom type, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s prior health problems. Tissue damage may lead to severe consequences, such as vascular degeneration and ischemia, which can culminate in limb amputation [57].

The local damage following envenomation is caused by the venom’s components (i.e., toxins) and these can lead to inflammatory signs, hemorrhage, and necrosis [17,58]. Indeed, there is a need to look into alternatives for local therapy, since little research has been carried out and applied in humans. On the other hand, there are in vitro and in vivo studies in the literature that support the development of additional research to discover effective local therapy alternatives. This review addresses several aspects of local treatment, as well as the use of questionable first-aid methods following envenomation.

Currently, the use of tourniquets is not recommended due to the possibility of developing gangrene, and neither is the prolonged use of cryotherapy [56]. Thus, the most important and recognized action is the prompt transport of the victim to medical care [3]. For snakebites, the time elapsed between the bite and hospital admission is the most crucial factor in the patient’s clinical outcome [2]. Medical treatment (i.e., antivenom), when delayed for more than 6 h, is associated with a greater risk of permanent sequelae and death [59]. In contrast, the tourniquets used in patients bitten by Crotalus durissus does not lead to any negative consequences; however, this does not apply to those bitten by Bothrops snakes and the use of this technique is contraindicated for any envenomation because it is not effective in preventing local complications [47]. Indeed, since 1988, the use of tourniquets after spider and snake envenomation is contraindicated, since tourniquets were observed to be responsible for a high proportion of tissue loss and permanent disability [8].

Other local treatments used to counter local venom-induced damage include cryotherapy and ice compresses for envenomation by jellyfish [50], centipedes [52], sea urchins [53] and scorpions [49], but these have not yet shown advantages for snakebite envenomation. In contrast, since the cold increases the vasoconstriction, some authors defend the use of warm compresses, since warmth can be beneficial for other kinds of envenomation such as those caused by Physalia physalise, (Portuguese man o’ war) [8,56,60]. However, it is noteworthy that in envenomation by scorpions, bees, spiders, ants, centipedes, and wasps, a cold compress may relieve some symptoms such as pain [8,49,60,61]. Indeed, it has been proven that ice packs, corticosteroids, antihistamines, oral analgesics, and local anesthetics were efficient in reducing local inflammatory symptoms and pain in cases of wasp, bee, and ant envenomation [61,62,63,64].

Regarding bee envenomation, antihistamines are not recommended because they cause drowsiness; thus, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cold compresses is recommended. Oral corticosteroids are indicated only when there are severe systemic manifestations; there is no evidence regarding their topical use, and injectable epinephrine has no benefits [61]. In another study, the authors recommend the use of epinephrine, oral and intravenous corticoid, and the application of cold compresses after bee stings [63].

For other envenomation by Hymenoptera, such as fire ants (Solenopsis invicta), the treatment of mild and severe envenomation (erythema, edema and pain) generally consists of conservative therapy, with indications of cold compresses, antihistamines, topical corticoids, topical application of lidocaine and, for symptomatic treatments, warm baths are indicated [63].

Regarding spiders, cleaning of the wound, raising the affected limb, immobilization, and cold compresses and analgesics are suggested as being effective [65] and, when there is no injury aggravation, the elevation and immobilization of the affected limb is recommended. In addition, for bites by the yellow spider, cold compresses and immobilization of the affected limb are indicated, as well as medication for the treatment of itching and analgesia (except acetylsalicylic acid) [65]. Other studies indicate that corticosteroids and intravenous antihistamines are not recommended because they are not effective against dermonecrosis, and the use of the antibiotic dapsone remains uncertain [60], which is different in cases of envenoming by the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles inmates), which vary from itching to death. In its most severe form, the bite of this spider causes tissue necrosis and ulcers [66,67].

Local care after a spider bite comprises rest, ice, compression, and elevation of the affected limb. Drug therapy with dapsone may limit the bite severity and prevent complications. When there is necrosis, the procedures must be surgical and must employ dressings for the healing process [66]. In Latrodectus mactans (black widow spider) envenomation, 10% calcium gluconate intravenous, metocarbamol and muscle relaxant are used, due the muscle stiffness that is caused by its venom [68].

In scorpion stings, topical lidocaine and intravenous paracetamol, in addition to the application of ice, is indicated for pain [49].

For local treatment of secondary infections and cellulitis in envenomation, chloramphenicol was not effective in Bothrops envenomation, when compared to the control group [44]. The use of prophylactic antibiotics in most snakebites is not supported by available scientific evidence, but some antibiotics, such as penicillin with β-Lactamase inhibitors, clindamycin and metronidazole, can be used in treatments [69]. A clinical trial showed little benefit from the preventive use of amoxicillin with clavulanate in the prevention of secondary infection by Bothrops snakes, which corroborates the results of studies by other authors. This scenario suggests that it is still necessary to select antibiotics to be used in future clinical trials for greater evidence of effective treatments for infections as a result of snakebites [63,70].

The only effective treatment for snakebite envenomation is antivenom therapy, but it acts in a systemic rather than local way [71]. In places in which antivenom is unavailable, popular or traditional medicine is often used [14]. A custom transmitted by generations, and widely used by native populations of Africa and Asia and Brazil, is the use of black stone in the treatment of snakebites; however, research demonstrates the ineffectiveness of its application in the patient’s clinical outcome [46,72].

The leaves of Jatropha molissima were tested (via intraplantar) in mice exposed to Bothrops venoms, and it was observed that when used 30 min earlier, at the concentration of 200 mg/kg, they presented an important inhibitory property and could be used in a complementary manner [36]. Vellozia flavicans is a plant with anti-inflammatory properties, and has been tested on Bothrops bites. It was found that it was able to neutralize the in vitro neuromuscular blockade of the diaphragmatic muscle of mice, but it does not have antimicrobial activity [37]. In the studies with plants as an alternative treatment, all the authors conclude that there is a need for more scientific research on the subject [13,14,73].

In the literature, it is noted that there are no effective treatments for local manifestations following envenomation; however, in recent years, several studies have maintained their focus on the benefits of phototherapy as a treatment modality to reduce pain, inflammation and edema, promote wound healing in deeper tissues and nerves, and prevent cell death and tissue damage [26,74].

Low-intensity laser treatment has proved itself to be effective in both in vivo and in vitro [75,76]. Studies have suggested a positive effect of photobiomodelating therapy (PBMT) on reducing local pathological effects caused by Bothrops venom, and acceleration of myotoxicity-related tissue regeneration [23,32,77]. However, regarding the ideal treatment parameter for clinical application, a protocol for clinical trials in humans has not yet been established [55,78].

Nadur-Andrade et al. (2016) provided a treatment using low-intensity laser in mice, at 30 min and 1 h after the envenomation. The results indicate the reduction of hyperalgesia and inhibition of the nociceptive response in the first and third hour of evaluation [28].

Barbosa (2008) showed that B. jararacusssu venom causes significant edema formation between 3 and 24 h after its inoculation, and a compound inflammatory infiltrate, predominantly by neutrophils, was witnessed 24 h after inoculation [22]. The use of low-intensity laser significantly reduced edema formation by 53% and 64%, at 3 and 24 h, respectively, and resulted in a reduction in neutrophil accumulation (p < 0.05) [29]. In this sense, laser therapy significantly reduced edema and leukocyte influx in envenomated muscle, which means that this may be a useful future therapy for the local effects caused by Bothrops venoms [16,79].

In this line of innovation for possible therapies, hyperbaric oxygen therapy was used effectively in the treatment of snakebites; it has helped to reduce tissue damage, and can often eliminate the need for surgical decompression of an imminent compartmental syndrome. It may act to prevent tissue damage due to inflammation, but it is not a treatment for tissue necrosis [48]. In 2021, an in vivo study examined the effects of ozonized oil therapy (OZT) associated with PBMT on the local effects caused by B. jararacusssu venom. The results indicated that individually, PBMT and OZT can partially protect against venom myonecrosis and edema, with OZT being the most effective, especially in early stages after envenomation, corroborating the need for clinical trials in humans to substantiate these new possibilities [80].

One limitation of this review was the non-indication of some of the local treatments adjuvant to antivenom, since most experimental studies are still in preclinical phases. Thus, a meta-analysis becomes untenable as evidence for recommending an intervention to reduce local effects in envenomation. Antivenom, even with a slow local action when compared to the systemic effects, is still the main neutralizer of inflammatory effects and tissue complications.

4. Conclusions

This review addresses evidence regarding adjuvant treatments in local damages following envenomation. Although the topic is still under explored, the identifying data found in vitro and in vivo indicate the need for and importance of exploring other local therapies that can complement the use of antivenoms in humans. On the other hand, a few alternative measures are still questionable, such as the use of tourniquets, cryotherapy, antihistamines, and corticosteroids. In respect to natural products (e.g., plants) their clinical findings have not yet been elucidated. Finally, low-intensity laser treatment methods have been demonstrated to be an efficient coadjuvant therapy for envenomation. This systematic review shows that concomitant therapies can contribute positively to controlling the worsening of envenomated tissue, especially in regards to local damage.

5. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed using the PubMed, MEDLINE, and LILACS databases, and aimed to analyze studies that reported local treatments of wounds and tissue inflammation following envenomation, and mainly used the descriptors “envenomation” and “local treatment” (in English). The period of the search was from 1979 to 2019 (40 years).

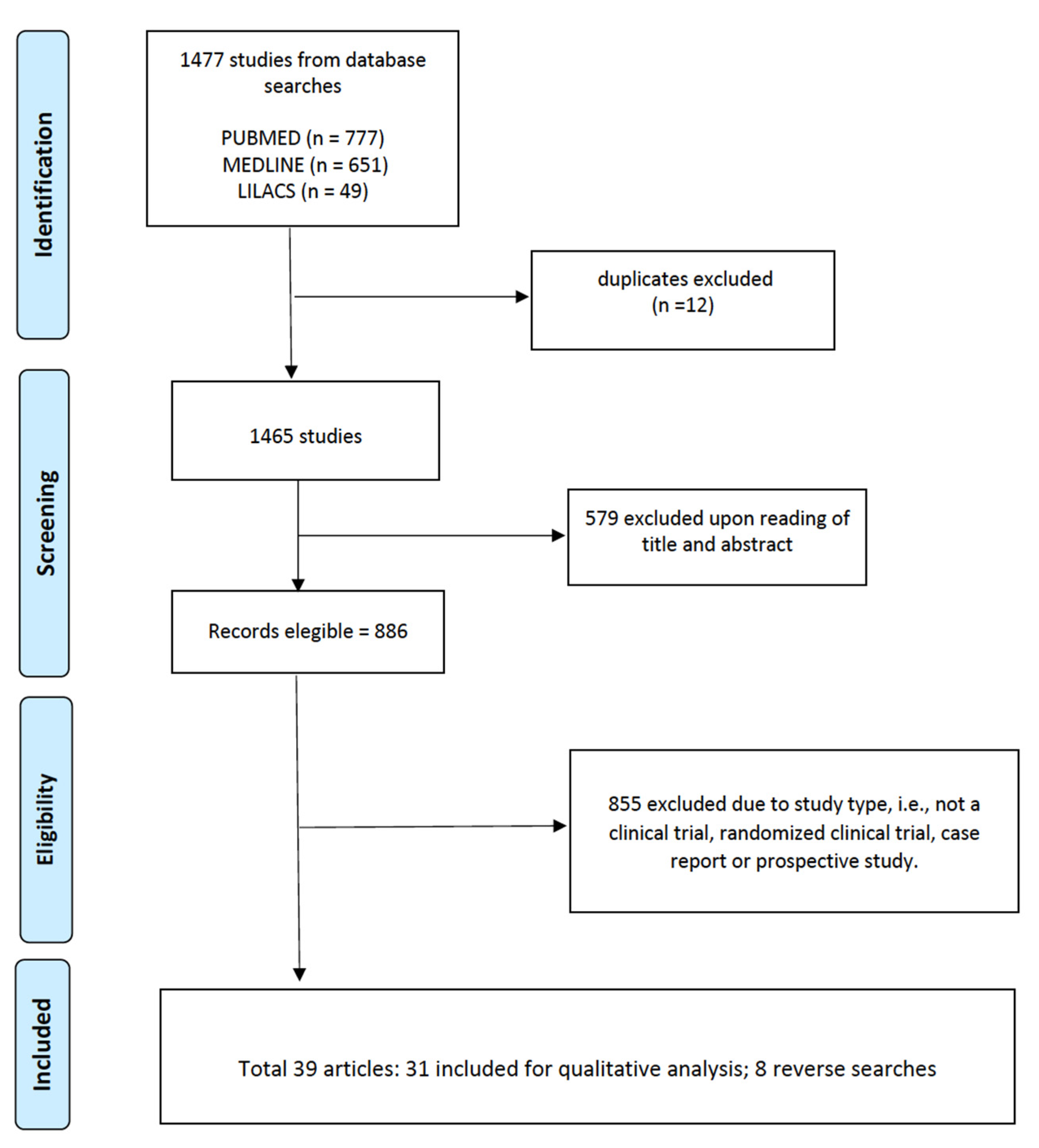

The selected articles (n = 39) were read and evaluated by peers, with the inclusion criteria for complete studies being: (a) access to the full content of the article, (b) clinical trial, (c) randomized clinical trial, (d) case report, and (e) prospective study. In summary, the review sought to unite all the procedures that were performed at the site of the envenomation, and aimed to identify the adjuvant treatments used. PRISMA was used as a methodology for the systematic review considering the CHECKLIST, and Figure 2 presents the article eligibility flowchart.

Figure 2.

Article eligibility flowchart.

The GRADE [54] scale was used to classify the evidence from the studies as high (High confidence in the correlation between true and estimated effect), moderate (Moderate confidence in the estimated effect, in which it is possible that the true effect is different from the estimated effect), low (Limited confidence in the estimated effect, in which it is possible that the effect may be very different from the estimated effect) or very low (Very little confidence in the estimated effect, in which the effect is very probably different from the estimated effect.). In the pre-clinical studies, the GRADE scale is not applied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.G.S. and É.S.C.; methodology, J.A.G.S., É.S.C. and B.B.O.M.; formal analysis, É.S.C., J.A.G.S., T.P.N. and A.V.d.S.N.; investigation, É.S.C., B.A.S.L., F.Q.A., B.F.V.J., A.R.N.S., A.W.A., B.B.O.M. and J.T.S.d.O.; resources, J.A.G.S. and W.M.M.; data curation, J.A.G.S., I.O., M.B.P. and F.H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, É.S.C., J.A.G.S., I.O. and M.B.P.; writing—review and editing, É.S.C., J.A.G.S., I.O., M.B.P., W.M.M. and F.H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, São Paulo Research Foundation scholarship to ISO No. 2020/13176-3 and No. 2022/08964-8), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (scholarships to JAGS No. 311434/2021-5, MP No. 307184/2020-0, WM No. 309207/2020-7)). WM acknowledges funding support from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas (PAPAC 005/2019, PRO-ESTADO and POSGRAD calls). JAGS acknowledges funding support from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas (010/2021-CT&I Áreas Prioritárias and 011/2021-PCGP calls).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bar-On, B. On the form and bio-mechanics of venom-injection elements. Acta Biomater. 2019, 85, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, R.D.S.; Queiroz, P.E.S.; Bastos, M.D.C.; Miranda, E.A.; Jesus, H.D.S.D.; Gatis, S.M.P. Tratamento da ferida por acidente ofídico: Caso clínico. Cuid. Enferm. 2016, 10, 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, A.V.; Araújo, K.A.M.D.; Marques, M.R.D.V.; Leite, R. Epidemiology of the injury with venomous animals in the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Northeast of Brazil. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachett, J.D.A.G.; Val, F.F.; Alcântara, J.A.; Cubas-Vega, N.; Montenegro, C.S.; da Silva, I.M.; de Souza, T.G.; Santana, M.F.; Ferreira, L.C.; Monteiro, W.M. Bothrops atrox Snakebite: How a Bad Decision May Lead to a Chronic Disability: A Case Report. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2020, 31, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, G.N.L.S.; de Oliveira, S.S.; dos Anjos, I.V.; Chalkidis, H.D.M.; Mourão, R.H.V.; Moura-Da-Silva, A.M.; Sano-Martins, I.S.; Gonçalves, L.R.D.C. Experimental Bothrops atrox envenomation: Efficacy of antivenom therapy and the combination of Bothrops antivenom with dexamethasone. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.H.; Mong, R. Scorpion Stings Presenting to an Emergency Department in Singapore with Special Reference to Isometrus maculatus. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2013, 24, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Manual de Diagnóstico e Tratamento de Acidentes por Animais Peçonhentos; Fundação Nacional de Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, G.S. Wound care of spider and snake envenomations. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1988, 17, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, I.K.; Dixit, P.P.; Pawade, B.S.; Potnis-Lele, M.; Kurhe, B.P. Assessment of Cultivable Oral Bacterial Flora from Important Venomous Snakes of India and Their Antibiotic Susceptibilities. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 74, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Résière, D.; Olive, C.; Kallel, H.; Cabié, A.; Névière, R.; Mégarbane, B.; Gutiérrez, J.; Mehdaoui, H. Oral Microbiota of the Snake Bothrops lanceolatus in Martinique. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, V.K.D.G.; Pereira, H.D.S.; Elias, I.C.; Soares, G.S.; Santos, M.; Talhari, C.; Cordeiro-Santos, M.; Monteiro, W.M.; Sachett, J.D.A.G. Secondary infection profile after snakebite treated at a tertiary referral center in the Brazilian Amazon. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2022, 55, e0244-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura, V.M.; Mourão, R.H.V.; Dos-Santos, M.C. Acidentes ofídicos na Região Norte do Brasil e o uso de espécies vegetais como tratamento alternativo e complementar à soroterapia. Sci. Amazon 2015, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Silva, J.; Silva-Junior, A.A.; Zucolotto, S.M.; Fernandes-Pedrosa, M.D.F. Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Local Tissue Damage Induced by Snake Venoms: An Overview from Traditional Use to Pharmacological Evidence. Evid.-Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2017, 2017, 5748256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, R.; Singh, P.; Yasir, M.; Hazarika, R.; Sugunan, S. A Review on Venom Enzymes Neutralizing Ability of Secondary Metabolites from Medicinal Plants. J. Pharmacopunct. 2017, 20, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, C.C.; Cavalcanti-Neto, A.J.; Boechat, A.L.; Francisco, C.H.; Arruda, M.R.E.; Dos-Santos, M.C. Eficácia da espécie vegetal Peltodon radicans (Labiatae, Lameaceae) na neutralização da atividade edematogênica e ineficácia do extrato vegetal Específico Pessoa na neutralização das principais atividades do veneno de Bothrops atrox. Rev. Univ. Amaz. 1996, 1, 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, A.M.; Villaverde, A.B.; Guimarães-Sousa, L.; Soares, A.M.; Zamuner, S.F.; Cogo, J.C.; Zamuner, S.R. Low-level laser therapy decreases local effects induced by myotoxins isolated from Bothrops jararacussu snake venom. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Trop. Dis. 2010, 16, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, D.M.; Fávero, S.; Baranauskas, V.; da Cruz-Höfling, M.A. Effects of the Ga-As laser irradiation on myonecrosis caused by Bothrops moojeni snake venom. Lasers Surg. Med. 2003, 33, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.L.; Dart, R.C.; Egen, N.B.; Mayersohn, M. Effects of constriction bands on rattlesnake venom absorption: A pharmacokinetic study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1992, 21, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, S.K.; Coulter, A.R.; Harris, R.D. Rationalisation of first-aid measures for elapid snakebite. Lancet 1979, 313, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, N.R.; Meisenheimer, J.L. Electric shock does not save snakebitten rats. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1988, 17, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadur-Andrade, N.; Zamuner, S.R.; Toniolo, E.F.; de Lima, C.J.; Cogo, J.C.; Dale, C.S. Analgesic Effect of Light-Emitting Diode (LED) Therapy at Wavelengths of 635 and 945 nm on Bothrops moojeni Venom-Induced Hyperalgesia. Photochem. Photobiol. 2014, 90, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.M.; Villaverde, A.B.; Guimarães-Souza, L.; Ribeiro, W.; Cogo, J.C.; Zamuner, S.R. Effect of low-level laser therapy in the inflammatory response induced by Bothrops jararacussu snake venom. Toxicon 2008, 51, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, E.A.; Bittencourt, J.A.H.M.; de Oliveira, N.K.S.; Henriques, S.V.C.; Picanço, L.C.D.S.; Lobato, C.P.; Ribeiro, J.R.; Pereira, W.L.A.; Carvalho, J.C.T.; da Silva, J.O. Effects of a low-level semiconductor gallium arsenide laser on local pathological alterations induced by Bothrops moojeni snake venom. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013, 12, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadur-Andrade, N.; Barbosa, A.M.; Carlos, F.P.; Lima, C.J.; Cogo, J.C.; Zamuner, S.R. Effects of photobiostimulation on edema and hemorrhage induced by Bothrops moojeni venom. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaretta, V.M.D.A.; Santos, L.P.; Barbosa, A.M.; Hyslop, S.; Corrado, A.P.; Galhardo, M.S.; Nicolau, R.A.; Cogo, J.C. Low-intensity laser therapy improves tetanic contractions in mouse anterior tibialis muscle injected with Bothrops jararaca snake venom. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 32, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.G.; Dale, C.; Nadur-Andrade, N.; Barbosa, A.M.; Cogo, J.; Zamuner, S. Low-level laser therapy reduces edema, leukocyte influx and hyperalgesia induced by Bothrops jararacussu snake venom. Clin. Exp. Med. Lett. 2011, 52, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Doin-Silva, R.; Baranauskas, V.; Rodrigues-Simioni, L.; Da Cruz-Höfling, M.A. The Ability of Low Level Laser Therapy to Prevent Muscle Tissue Damage Induced by Snake Venom. Photochem. Photobiol. 2009, 85, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadur-Andrade, N.; Dale, C.S.; Oliveira, V.R.D.S.; Toniolo, E.F.; Feliciano, R.D.S.; da Silva, J.A., Jr.; Zamuner, S.R. Analgesic Effect of Photobiomodulation on Bothrops Moojeni Venom-Induced Hyperalgesia: A Mechanism Dependent on Neuronal Inhibition, Cytokines and Kinin Receptors Modulation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.M.; Villaverde, A.B.; Sousa, L.G.; Munin, E.; Fernandez, C.M.; Cogo, J.C.; Zamuner, S.R. Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy in the Myonecrosis Induced by Bothrops jararacussu Snake Venom. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2009, 27, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourado, D.M.; Matias, R.; Barbosa-Ferreira, M.; da Silva, B.A.K.; de Araujo Isaias Muller, J.; Vieira, W.F.; da Cruz-Höfling, M.A. Effects of photobiomodulation therapy on Bothrops moojeni snake-envenomed gastrocnemius of mice using enzymatic biomarkers. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, W.F.; Kenzo-Kagawa, B.; Cogo, J.C.; Baranauskas, V.; da Cruz-Höfling, M.A. Low-Level Laser Therapy (904 nm) Counteracts Motor Deficit of Mice Hind Limb following Skeletal Muscle Injury Caused by Snakebite-Mimicking Intramuscular Venom Injection. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, D.M.; Fávero, S.; Matias, R.; Carvalho, P.D.T.C.; da Cruz-Höfling, M.A. Low-level Laser Therapy Promotes Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-1 Expression in Endothelial and Nonendothelial Cells of Mice Gastrocnemius Exposed to Snake Venom. Photochem. Photobiol. 2011, 87, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadur-Andrade, N.; Dale, C.S.; dos Santos, A.S.; Soares, A.M.; de Lima, C.J.; Zamuner, S.R. Photobiostimulation reduces edema formation induced in mice by Lys-49 phospholipases A2 isolated from Bothrops moojeni venom. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13, 1561–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourado, D.M.; Matias, R.; Almeida, M.F.; De Paula, K.R.; Vieira, R.P.; Oliveira, L.V.F.; Carvalho, P.T.C. The effects of low-level laser on muscle damage caused by Bothrops neuwiedi venom. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Trop. Dis. 2008, 14, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, W.H.; Abdel-Aty, A.M.; Fahmy, A.S. Rosemary leaves extract: Anti-snake action against Egyptian Cerastes cerastes venom. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2018, 8, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.A.D.S.; Félix-Silva, J.; Fernandes, J.M.; Amaral, J.G.; Lopes, N.P.; Egito, E.S.T.D.; da Silva-Júnior, A.A.; Zucolotto, S.M.; Fernandes-Pedrosa, M.D.F. Aqueous Leaf Extract of Jatropha mollissima (Pohl) Bail Decreases Local Effects Induced by Bothropic Venom. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, e6101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribuiani, N.; da Silva, A.M.; Ferraz, M.C.; Silva, M.G.; Bentes, A.P.G.; Graziano, T.S.; dos Santos, M.G.; Cogo, J.C.; Varanda, E.A.; Groppo, F.C.; et al. Vellozia flavicans Mart. ex Schult. hydroalcoholic extract inhibits the neuromuscular blockade induced by Bothrops jararacussu venom. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, T.; Sreedevi, N.S.; Meenatchisundaram, S.; Vadivelan, R. Antitoxin activity of aqueous extract of Cyclea peltata root against Naja naja venom. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2017, 49, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saturnino-Oliveira, J.; Santos, D.D.C.; Guimarães, A.G.; Santos Dias, A.; Tomaz, M.A.; Monteiro-Machado, M.; Estevam, C.S.; Lucca Júnior, W.D.; Maria, D.A.; Melo, P.A.; et al. Abarema cochliacarpos Extract Decreases the Inflammatory Process and Skeletal Muscle Injury Induced by Bothrops leucurus Venom. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, e820761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Chen, C.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M. Small Incisions Combined with Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy for Treatment of Protobothrops mucrosquamatus Bite Envenomation: A New Treatment Strategy. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2019, 25, 4495–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, E.C.; Fernandes, C.P.; Sanchez, E.F.; Rocha, L.; Fuly, A.L. Inhibitory Effect of Plant Manilkara subsericea against Biological Activities of Lachesis muta Snake Venom. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, e408068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.; Kohn, M.; Baker, D.; Leest, R.V.; Gomez, H.; McKinney, P.; McGoldrick, J.; Brent, J. Therapy of Brown Spider Envenomation: A Controlled Trial of Hyperbaric Oxygen, Dapsone, and Cyproheptadine. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1995, 25, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, D.B.K.; Kelly, D.; Hamilton, R.G.; Craig, T.J. Venom immunotherapy reduces large local reactions to insect stings. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 1371–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M.T.; Malaque, C.; Ribeiro, L.A.; Fan, H.W.; Cardoso, J.L.C.; Nishioka, S.A.; Sano-Martins, I.S.; França, F.O.S.; Kamiguti, A.S.; Theakston, R.D.G.; et al. Failure of chloramphenicol prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of abscess formation as a complication of envenoming by Bothrops snakes in Brazil: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004, 98, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrell, D.; Pe, T.; Swe, T.N.; Lwin, M.; Win, T. The efficacy of tourniquets as a first-aid measure for Russell’s viper bites in Burma. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1987, 81, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Ramos-Cerrillo, B.; Stock, R.P. Study of the efficacy of the black stone on envenomation by snake bite in the murine model. Toxicon 2007, 49, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, C.F.S.; Campolina, D.; Dias, M.B.; Bueno, C.M.; Rezende, N.A. Tourniquet ineffectiveness to reduce the severity of envenoming after Crotalus durissus snake bite in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Toxicon 1998, 36, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korambayil, P.M.; Ambookan, P.V.; Abraham, S.V.; Ambalakat, A. A Multidisciplinary Approach with Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Improve Outcome in Snake Bite Injuries. Toxicol. Int. 2015, 22, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksel, G.; Güler, S.; Doğan, N.; Çorbacioğlu, Ş. A randomized trial comparing intravenous paracetamol, topical lidocaine, and ice application for treatment of pain associated with scorpion stings. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2015, 34, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exton, D.R.; Fenner, P.J.; Williamson, J.A. Cold packs: Effective topical analgesia in the treatment of painful stings by Physalia and other jellyfish. Med. J. Aust. 1989, 151, 625–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, J.T.; Sato, R.L.; Ahern, R.M.; Snow, J.L.; Kuwaye, T.T.; Yamamoto, L.G. A randomized paired comparison trial of cutaneous treatments for acute jellyfish (Carybdea alata) stings. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2002, 20, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaou, C.-H.; Chen, C.-K.; Chen, J.-C.; Chiu, T.-F.; Lin, C.-C. Comparisons of ice packs, hot water immersion, and analgesia injection for the treatment of centipede envenomations in Taiwan. Clin. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazorla, D.; Loyo, J.; Lugo, L.; Acosta, M. Clinical, epidemiological and treatment aspects of five cases of sea urchin envenomation in Adicora, Paraguaná peninsula, Falcón state, Venezuela. Bol. Malariol. Salud Ambient. 2010, 50, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo-Albasini, J.L.; Flores-Pastor, B.; Soria-Aledo, V. GRADE System: Classification of Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendation. Cir. Esp. 2014, 92, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.M.G.; Zamuner, L.F.; David, A.C.; dos Santos, S.A.; Carvalho, P.D.T.C.D.; Zamuner, S.R. Photobiomodulation therapy on Bothrops snake venom-induced local pathological effects: A systematic review. Toxicon 2018, 152, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.K. Snake Envenomation Incidence, Clinical Presentation and Management. Med. Toxicol. Advers. Drug Exp. 1989, 4, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonte, B.; Moreno, E.; Tarkowski, A.; Hanson, L.A.; Maccarana, M. Neutralizing interaction between heparins and myotoxin II, a lysine 49 phospholipase A2 from Bothrops asper snake venom. Identification of a heparin-binding and cytolytic toxin region by the use of synthetic peptides and molecular modeling. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 29867–29873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakil, T.F. An in-vivo experimental evaluation of He–Ne laser photostimulation in healing Achilles tendons. Lasers Med. Sci. 2007, 22, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, E.L.; Sampaio, V.S.; Salinas, J.L.; Queiroz, A.M.; da Silva, I.M.; Gomes, A.A.; Sachett, J.; Siqueira, A.M.; Ferreira, L.C.L.; dos Santos, M.C.; et al. Older Age and Time to Medical Assistance Are Associated with Severity and Mortality of Snakebites in the Brazilian Amazon: A Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premmaneesakul, H.; Sithisarankul, P. Toxic jellyfish in Thailand. Int. Marit. Health 2019, 70, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Golden, D.B.K. Large local reactions to insect envenomation. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 16, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villas-Boas, I.M.; Bonfá, G.; Tambourgi, D.V. Venomous caterpillars: From inoculation apparatus to venom composition and envenomation. Toxicon 2018, 153, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.T.; Flood, A.A. Hymenoptera Stings. Clin. Tech. Small Anim. Pract. 2006, 21, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibel, J.A.; Clore, E.R. Prevention and Primary Care Treatment of Stings from Imported Fire Ants. Nurse Pract. 1992, 17, 65–66,68,71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varl, T.; Grenc, D.; Kostanjšek, R.; Brvar, M. Yellow sac spider (Cheiracanthium punctorium) bites in Slovenia: Case series and review. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2017, 129, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, J.; Bassichis, B.; Itani, K. Brown Recluse Spider Bites to the Head: Three Cases and a Review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004, 83, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Saúde, M.; de Vigilância em Saúde, S. Guia de Vigilância em Saúde, 5th ed.; Departamento de Articulação Estratégica de Vigilância em Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2021; ISBN 978-65-5993-102-6. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, L.S. Acute Arthropod Envenomation: Incidence, Clinical Features and Management. Med. Toxicol. Advers. Drug Exp. 1989, 4, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, S.A.; Keyler, D.E. Local envenoming by the Western hognose snake (Heterodon nasicus): A case report and review of medically significant Heterodon bites. Toxicon 2009, 54, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachett, J.A.G.; da Silva, I.M.; Alves, E.C.; Oliveira, S.S.; Sampaio, V.S.; do Vale, F.F.; Romero, G.A.S.; dos Santos, M.C.; Marques, H.O.; Colombini, M.; et al. Poor efficacy of preemptive amoxicillin clavulanate for preventing secondary infection from Bothrops snakebites in the Brazilian Amazon: A randomized controlled clinical trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.; Lomonte, B.; Leon, G.; Rucavado, A.; Chaves, F.; Angulo, Y. Trends in Snakebite Envenomation Therapy: Scientific, Technological and Public Health Considerations. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 2935–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel Salazar, G.K.; Saturnino Cristino, J.; Vilhena Silva-Neto, A.; Seabra Farias, A.; Alcântara, J.A.; Azevedo Machado, V.; Murta, F.; Souza Sampaio, V.; Val, F.; Sachett, A.; et al. Snakebites in “Invisible Populations”: A cross-sectional survey in riverine populations in the remote western Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shedoeva, A.; Leavesley, D.; Upton, Z.; Fan, C. Wound Healing and the Use of Medicinal Plants. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 2684108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.C. Laser (and LED) Therapy Is Phototherapy. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2005, 23, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frozanfar, A.; Ramezani, M.; Rahpeyma, A.; Khajehahmadi, S.; Arbab, H.R. The Effects of Low Level Laser Therapy on the Expression of Collagen Type I Gene and Proliferation of Human Gingival Fibroblasts (Hgf3-Pi 53): In vitro Study. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2013, 16, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.M.G.; da Silva, C.A.A.; da Silva, A.; Vieira, R.P.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Cogo, J.C.; Zamuner, S.R. Photobiomodulation Protects and Promotes Differentiation of C2C12 Myoblast Cells Exposed to Snake Venom. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, V.A.; Pisete, F.R.F.S.; Wagner, C.L.R.; Dalboni, M.A.; de Oliveira, A.P.L.; Cogo, J.C.; Zamuner, S.R. Photobiomodulation reduces cell death and cytokine production in C2C12 cells exposed to Bothrops venoms. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, N.H.C.; Ferrari, R.A.M.; Silva, D.F.T.; Nunes, F.D.; Bussadori, S.K.; Fernandes, K.P.S. Effect of low-level laser therapy on the modulation of the mitochondrial activity of macrophages. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2014, 18, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, E.A.; Bittencourt, J.A.M.; De Oliveira, N.K.S. Influence of a low-level semiconductor gallium arsenate laser in experimental envenomation induced by Bothrops atrox snake venom. Am. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012, 7, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Fernandes, J.O.; de Gouveia, D.M.; David, A.C.; Nunez, S.C.; Zamuner, S.R.; Magalhães, D.S.F.; Navarro, R.S.; Cogo, J.C. The use of ozone therapy and photobiomodulation therapy to treat local effects of Bothrops jararacussu snake venom. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 37, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).